1. Introduction

Plant natural products or specialized metabolites represent a rich and diverse array of compounds that humans have found useful for thousands of years. Terpenoids are the largest class of natural products with more than 80,000 compounds (for a recent review see [

1]) used in different areas ranging from fragrances and flavorings to pesticides and pharmaceuticals. In terms of production and market value, natural rubber, or polyisoprene, is one of the most important terpenoids with 13.2 million tonnes produced and a 26 billion US

$ market value in 2017 [

2]. The diterpenoid paclitaxel is an anti-cancer drug sold under the trade name Taxol

® and has a reported annual market value of over 1 billion US

$ [

3]. These examples show terpenoids’ economic importance and provide a glimpse into the scale of demand. However, it is important to find more sustainable methods of production, especially for diterpenoids, which are typically produced in very low amounts in their host plants, are structurally complex, and are in ever-increasing global demand [

4]. When target diterpenoids like forskolin, ginkgolides and triptonide are exclusively produced in the roots of their host plants, digging out and harvesting the root material destroys the plants and has adverse consequences on soil erosion and demands extra areas of arable land when each harvest requires growth of a new generation of plants [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Heterologous production of plant-derived terpenoids in microorganisms is therefore an attractive alternative means of production that is independent of the use of arable land, does not result in soil erosion and reduces the amounts of fossil fuel-based solvents and waste products associated with low-yield isolation from plant tissues harboring many other natural products. Biosynthesis of terpenoids in plants proceeds from an orchestrated complex crosstalk between the two canonical C5-isoprene biosynthetic pathways: the mevalonate pathway (MVA) operating in the cytosol of the plant cell and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway operating in the plastids [

9,

10]. Cyanobacteria, like chloroplasts, use the MEP pathway [

11]. Both pathways converge with the production of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMADP). These C5-isoprene precursor molecules may be condensed to form C10 (monoterpenoids), C15 (sesquiterpenoids), C20 (diterpenoids), and a continuum of larger condensates.

The linear (C5)

n isoprenoids serve as substrates for terpene synthases, which catalyze the formation of cyclized core terpene structures of varying complexity. These are further decorated by oxygenations catalyzed by an assortment of cytochrome P450s (P450s) and by soluble transferases. This results in complex regio- and stereospecific modifications, which complicate classical organic chemical synthesis [

12]. P450s in eukaryotes are endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane-bound enzymes, dependent on electron donation from NADPH catalyzed by another membrane-bound protein, the cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Cyanobacteria have attracted attention in recent years as heterologous production hosts as they merely require atmospheric CO

2, inorganic elements, and light to grow and produce organic compounds [

17,

18,

19]. Such potential for carbon neutral or near carbon neutral production has accelerated the field of metabolic engineering in cyanobacteria [

20,

21,

22]. Additionally, cyanobacteria occupy a wide range of ecological niches, allowing for the selection of species that grow in diverse non-arable locations [

23]. As mentioned, P450s catalyze stereo- and regioselective oxygenations and require a dedicated reductase as well as reducing equivalents like ferredoxin or NADPH to be active. Both are produced by photosynthesis, rendering terpenoids prime targets for heterologous production in cyanobacteria. We and others have previously shown donation of electrons from photosystem I (PSI) to cytochrome P450s by endogenous soluble electron donors like ferredoxin and flavodoxin without the need for a dedicated reductase [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Of the two photosystems embedded in the thylakoid membranes, PSI is by far the most stable and when exposed to photoinhibitory conditions protected by changes in cyclic electron transport around PSI [

30]. The light-driven synthesis based on electron donation from PSI to the P450s is thus very robust and can support P450 turnover.

In this study, we engineered

Synechocystis sp. PCC. 6803 (hereafter

Synechocystis) to produce forskolin. Forskolin is a bioactive structurally complex labdane-type diterpenoid containing eight chiral carbon atoms and acts as a cyclic AMP (cAMP) activator [

31]. Studies have implicated the use of forskolin in the treatment of heart failure, glaucoma, and for the induction of UV-less tanning, although approved clinical use has yet to be realized [

32,

33,

34]. We show the production of forskolin by expression of all six genes encoding the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of forskolin in

Plectranthus barbatus (previously known as

Coleus forskohlii) (

Figure 1A) [

5,

6]. To our knowledge, this is the first example of the production of a structurally complex diterpenoid in a cyanobacterial host.

2. Materials and Methods

Starter Cultures

Starter cultures of Synechocystis were grown from freezer stocks on plates at 30°C at approximately 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1 irradiation using fluorescent lights. Liquid cultures were grown in culture tubes in a water bath at 30°C with approximately 50 µ µmol photons m-2 s-1 fluorescent light with 3% CO2 (v/v) supplementation by bubbling.

Photo-Bioreactor Cultures

Growth curves were performed in a Multi Cultivator MC 1000-OD (Photon System Instruments). Starter cultures (20 mL) were inoculated from plates and grown in liquid cultures as described above. Initial 70 mL cultures were inoculated at 0.3 OD730 in BGH11 and supplemented with 100 µg/mL kanamycin and spectinomycin. Cultures were flushed with 3% CO2 (v/v) and grown at 30°C at a light intensity of 100 µmol photons m-2 s-1. OD at 730 nm was measured, and sample aliquots were collected, at the start (day 1) and subsequently at day 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8. Cultures were induced on day 2 with 1 mM IPTG to ensure expression from the pDF-trc plasmid. Cells in the sample aliquots were harvested by centrifugation for further analysis.

Quantification of Forskolin

Samples were prepared by collecting 1.5 mL of the supernatant at day 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8. Samples were concentrated to roughly 200 µL by vacuum centrifugation and extracted three times with 400 µL of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate was collected and evaporated to dryness by vacuum centrifugation and the residue was resuspended in 80% MeOH spiked with 5 ppm andrographolide as an internal standard. The quantification of forskolin and deacetylforskolin was essentially performed as reported in Pateraki et al. [

6]. In brief, LC-MS was performed using an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC Focused system coupled to a Bruker Compact ESI-QTOF-MS using a Kinetex XB-C18 column (100 x 2.1 mm i.d; 1.8 µm particle size, 100 Å pore size). The column was maintained at 40°C with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min and a mobile phase consisting of A: 0.05% (v/v) formic acid in water and B: 0.05% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v). The gradient used was as follows: 0-1 min isocratic 20% B; 1-23 min linear gradient to 100% B; 23-23.5 min linear gradient to 20% B; 23.5-27.5 min isocratic 20% B. The ESI source parameters were as follows: capillary voltage: 4500 V, dry gas flow: 8 l/min, dry gas temperature: 250°C. Operation was set in MS/MS mode with the collision cell energy set to 7 eV and the RF set to 500 Vpp. Ions were monitored in positive mode at the m/z range 50-1300 and spectra collected at a rate of 2 Hz. The injection volume was 20 µL. Quantification was performed by calibration to authentic deacetylforskolin and forskolin standards.

Chlorophyll Extraction and Quantification

Sample preparation for chlorophyll analysis was performed by taking 1.5 mLs of culture at day 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 of the photobioreactor run and harvesting the pellet. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of 95% MeOH flushed with nitrogen gas. The pigments were left for extraction in the dark in sealed tubes for 1 h with the headspace flushed with nitrogen gas. The resulting sample was filtered through a Durapore 0.22 µm PVDF centrifugal filter. Pigment analysis was performed on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC equipped with an SPD-M20A module using an Agilent Zorbax Extend-C18 column (150 mm x 4.6 mm i.d.; 2.5 µm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of A: acetonitrile/methanol/0.1M Tris-HCl pH 8.0 (84/2/14 v/v/v) and B: methanol/ethyl acetate (68/32 v/v). A gradient between A and B was performed as follows: 0-20 min linear from 100 to 0% A; 20-26 min isocratic 0% A; 26-27 min linear 0 – 100% A; 27 – 38 min isocratic 100% A. The injection volume and flow rate was 40 µL and 1 mL/min respectively. Peaks were detected and integrate at 445 nm for chlorophyll a. Chlorophyll a was identified by its absorption spectra as well as its elution time.

3. Results and Discussion

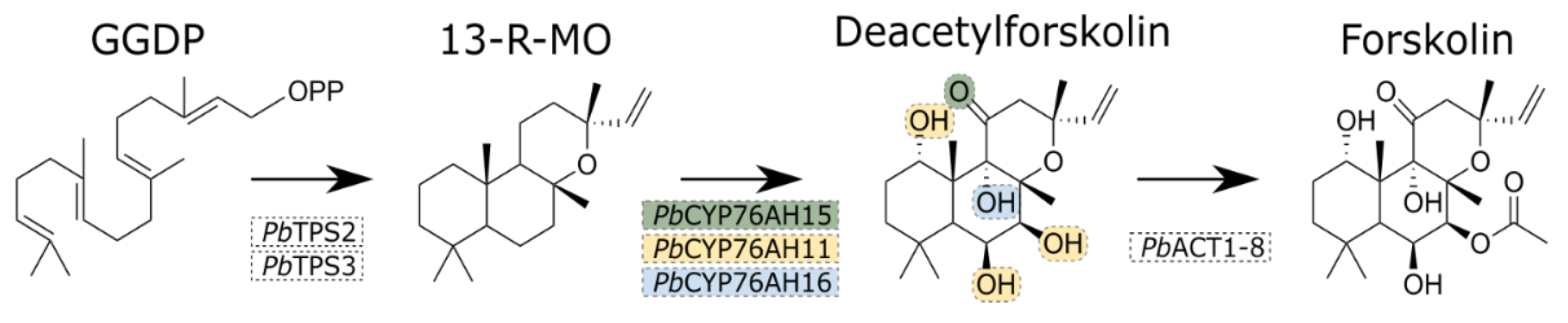

The first step committed in forskolin biosynthesis is the conversion of GGDP to 13-R-Manoyl Oxide (13-R-MO) catalyzed by two diterpene synthases (TPSs) (

Figure 1). Subsequently, five oxygenation events on the carbon skeleton catalyzed by three different P450s yields deacetylforskolin. Finally, an acetyltransferase (ACT) converts deacetylforskolin into forskolin [

6].

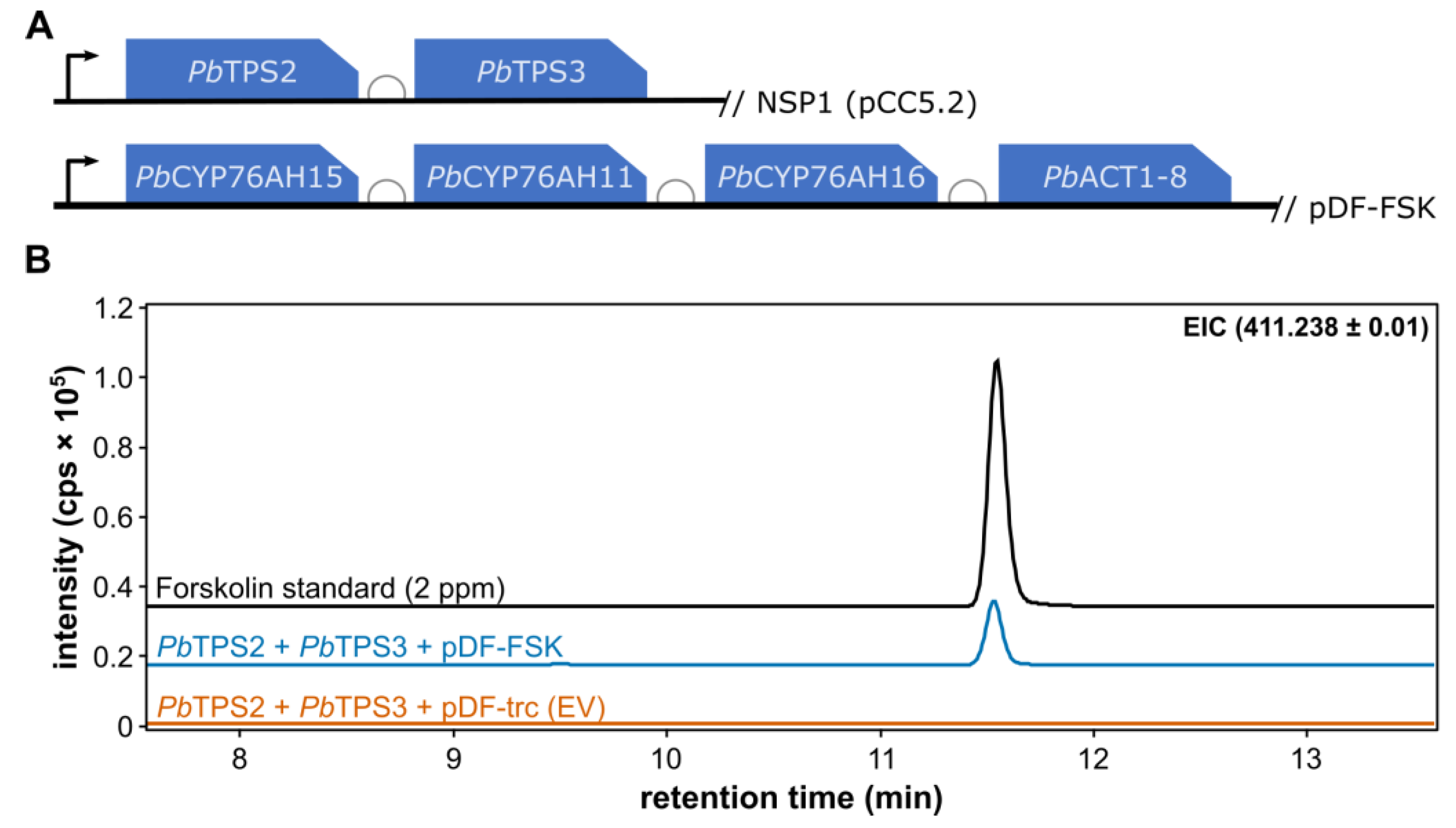

A forskolin-producing

Synechocystis strain was built by integration of the two terpene synthases driven by the P

cpc560 promoter [

39] into the NSP1 neutral site [

36], and by the expression of an operon containing the three P450s and the acetyl transferase was driven by the P

trc promoter on the replicative plasmid pDF-trc [

35] (

Figure 2A). Independent antibiotic-resistant colonies were selected and screeded for forskolin production. Measuring the activity of individual enzymes in the pathway was not possible because the required intermediates are complex, challenging to synthesize, and difficult to isolate from natural sources due to their structural similarity to other intermediates, making purification impractical for enzymatic assays. Instead, we decided to analyse the production of the end-product forskolin, the compound previously documented to be synthesized by the six genes here introduced in

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 [

6]. Indeed, the strain containing the two diterpene synthases and the plasmid carrying the three cytochrome P450 genes and the acetyltransferase (pTPS2/3 and pDF-FSK) produce detectable forskolin after 8 days (

Figure 2B). No forskolin could be detected in a corresponding strain containing the empty pDF-trc vector. These results imply that the complete pathway is expressed and active in cyanobacteria.

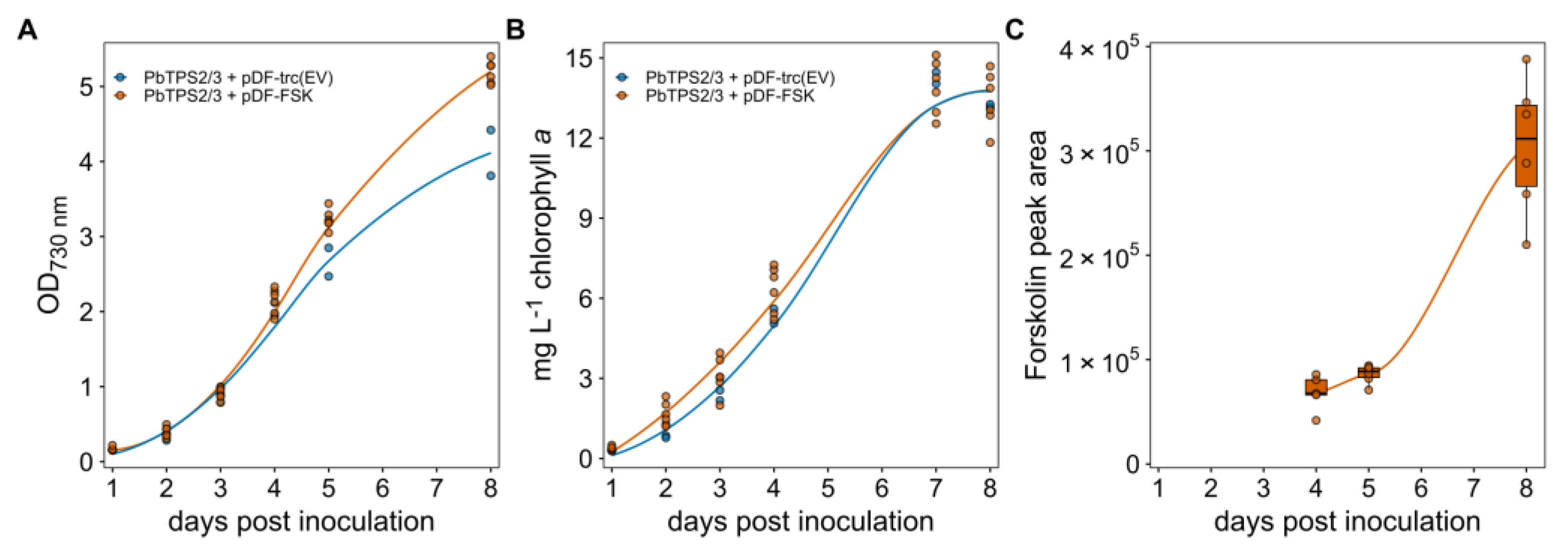

Transformants of the forskolin producing strain (FSK) as well as an empty vector control were grown in a photobioreactor as outlined in Material and Methods. Over 8 days of growth, the OD

730 of the culture and chlorophyll

a content of the cells were measured (

Figure 3A,B). The FSK strain reached an OD

730 around 5 while the empty vector control reached an OD around 4 after 8 days growth. The chlorophyll

a content was quite similar in the two strains. The difference in the observed OD and chlorophyll content can be explained by the fact that the forskolin producing cells are slightly bigger (data not shown). Forskolin accumulation was also measured at day 4, 5 and 8 and was found to accumulate over time, becoming detectable in supernatant only after 4 days of cultivation. Overall, this suggests that the production of forskolin had no negative effect of the growth of the

Synechocystis cells.

The expression of all six enzymes in the forskolin biosynthetic pathway in

Synechocytis resulted in forskolin titers of 25 ± 4.4 µg/mL in bio-reactor cultures at day 8 with no forskolin detected in the control strain. Both the cell-free supernatant and the cell pellet were extracted to localize where the product accumulated. Forskolin was exclusively found in the cell-free supernatant suggesting that all is secreted from the cells. Acetylforskolin, forskolin decorated with an extra acetyl group, was also identified in the supernatant (data not shown) but could not be quantified due to a lack of a genuine standard. In

Synechocystis strains producing forskolin, the starting precursor 13-R-MO and the deacetylforskolin intermediate (

Figure 1) could not be detected using LC-MS analysis of the extracts. This could suggest that production of forskolin in

Synechocystis is limited by precursor supply and future attempts to increase productivity should focus on increasing the supply of GGDP.

The fact that the forskolin is secreted is interesting. We have previously shown that production of water-soluble compounds like dhurrin,

p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde oxime, and aromatic amino acids in

Synechocystis are secreted to the medium [

26,

42,

43]. The ability of

Synechocystis and possibly other cyanobacteria for secretion of most of a desired produced compound would facilitate easier recovery of the produced compounds.

Recently we reported the production of the forskolin precursor 13-R-manoyl oxide (the product of the two diterpene synthases) which after 7 d in a photobioreactor accumulated to 880 µg/mL [

40]. Using a similar growth system, we in the current study observe production of 25 µg/L forskolin as well as an unknown amount of acetylforskolin. Production of simple terpenes are well-studied in the literature. Squalene, a triterpene (30-carbons), was produced in

Synechocystis and reached a titer of 5.1 mg/L of culture in combination with over-expressing MEP pathway genes [

44]. Using a high-density cultivation system with

Synechocystis, production of bisabolene, a sesquiterpene (15-carbons) reached 179.4 mg/L, and its oxidized form, bisabolol, reached 96.3 mg/L [

45]. Even though it can be difficult to compare across different experimental setups, it is clear that

Synechocystis has the potential to produce larger amounts of terpenes than the amounts of 13-R-manoyl oxide obtained in Sutardja et al., [

40] and the amount of forskolin obtained in the current study. The reason for this is likely a combination of precursor supply, complexity of the enzymatic steps involved and potential toxicity of the products or one or more of the intermediates. In this study we did not introduce the cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase that normally serves the electron donor to the P450s in

Plectranthus barbatus.

Synechocystis do not have a cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase, and it is therefore assumed that photo-reduced ferredoxin donates electrons to the three introduced P450s in the forskolin pathway as shown previously [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

In conclusion, we show that expression in Synechocystis PCC. 6803 of the six genes encoding the enzymes involved in forskolin biosynthesis results in 25 µg/L forskolin without optimization of the photo-bioreactor conditions used. This represents the first engineered production of a structurally complex diterpenoid in a cyanobacterium. Precursor supply is hypothesized to be limited. Overall, we show a large potential for forskolin production and highlight steps needed to overcome the bottlenecks discovered in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, PEJ, TG, LMML, LCS, AZN and ND; methodology, LCS, ND, TG, and SM; formal analysis, LCS, ND, and SM; resources, PEJ and BLM; writing—original draft preparation, LCS, ND, AZN; writing—review and editing, PEJ, BLM, ND and SM; supervision, PEJ, BLM and AZN; project administration, PEJ; funding acquisition, PEJ and BLM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: 1) Center for Synthetic Biology “bioSYNergy” (UCPH Excellence Program for Interdisciplinary Research), 2) Innovation Fund Denmark (Project no: 12-131834), 3) Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF13OC0005685; NNF19OC0057634; NNF19OC0054563), 4) VILLUM Foundation (Project no: 13363), 5) VILLUM Center for Plant Plasticity (Project No. VKR023054) and 6) European Research Council Advanced Grant (ERC-2012-ADG_20120314, Project no: 323034).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lisbeth Mikkelsen for the technical support and Drs. Irini Pateraki and Victor Forman for technical advice on manoyl oxide and forskolin detection and quantification. We would like to thank Himadri Pakrasi for the plasmid pSL2387 and Pia Lindberg for the coding sequences for the terpene synthases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Klaus, O. , Hilgers, F., Nakielski, A. Hasenklever, D., Jaeger, K.-E., Axmann, I.M., Drepper, T. (2022). Engineering phototrophic bacteria for the production of terpenoids. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 77: 102764. [CrossRef]

- Men, X. , Wang, F., Chen, G.Q., Zhang, H.B., Xian, M., 2019. Biosynthesis of natural rubber: Current state and perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.S.A. , Abdel-Ghany, S.E., Ali, G.S., 2017. Genome editing approaches: manipulating of lovastatin and taxol synthesis of filamentous fungi by CRISPR/Cas9 system. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 101, 3953-76. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M. Andersen-Ranberg, J. Hankamer, B., Møller, B.L. (2022) Circular biomanufacture through harvesting solar energy and CO2. Trends in Plant Sciences 27, 655-673. [CrossRef]

- Pateraki, I. , Andersen-Ranberg, J., Hamberger, Britta, Heskes, A.M., Martens, H.J., Zerbe, P., Bach, S.S., Møller, B.L., Bohlmann, J., Hamberger, Björn, 2014. Manoyl oxide (13R), the biosynthetic precursor of forskolin, is synthesized in specialized root cork cells in Coleus forskohlii. Plant Physiology 164, 1222–1236. [CrossRef]

- Pateraki, I. , Andersen-Ranberg, J., Jensen, N.B., Wubshet, S.G., Heskes, A.M., Forman, V., Hallström, B., Hamberger, Britta, Motawia, M.S., Olsen, C.E., Staerk, D., Hansen, J., Møller, B.L., Hamberger, Björn, 2017. Total biosynthesis of the cyclic AMP booster forskolin from Coleus forskohlii. eLife 6. [CrossRef]

- Forman, V. , Luo, D., Lemcke, R., Nelson, D.R., Staerk, D., Kampranis, S., Møller, B.L., Pateraki, I. (2022). A gene cluster in Ginkgo biloba encoding for unique multifunctional cytochrome P450s orchestrates key steps in ginkgolide biosynthesis. Nature Communications, 13(5143). [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.L. , Kjærulff, L. Heck, Q., Forman, V., Stærk, D., Møller B.L., Andersen-Ranberg. J. (2022). Tripterygium wilfordii. [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, B. , Lindberg, P., 2015. Terpenoids and their biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Poudereux, I. , Kutzner, E., Huber, C., Segura, J., Eisenreich, W., Arrillaga, I., 2015. Metabolic cross-talk between pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis in spike lavender. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 95, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, M. (2003). Mevalonate-independent methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis. Elucidation and distribution. Pure Appl. Chem., 75, 375–387. [CrossRef]

- Bathe, U. , Tissier, A., 2019. Cytochrome P450 enzymes: A driving force of plant diterpene diversity. Phytochemistry 161, 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K. , Jensen, P.E., Møller, B.L., 2012. Light-driven chemical synthesis. Trends in Plant Science 17: 1360-1385. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K, Møller, B.L., 2010. Plant NADPH-cytochrome P450 0xidoreductases. Phytochemistry 71: 132-141. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K. , Jensen P.E., Møller B.L., 2011. Light-driven cytochrome P450 hydroxylations. ACS Chemical Biology 6: 533-539.

- Jensen, S.B. , Thodberg S., Parween S., Moses M.E., Hansen C.C., Thomsen J., Sletfjerding M.B., Knudsen C., Giudice R.D., Lund P.M., Castaño P.R., Bustamante Y.G., Velazquez M.N.R., Jørgensen F.S., Pandey A.V., Laursen T., Møller B.L., Hatzakis N.S., 2021. Biased cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism via small-molecule ligands binding P450 oxidoreductase. Nature Communications 12: 2260. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. , Liberton, M., Hendry, J.I., Aminian-Dehkordi, J., Maranas, C.D., Pakrasi, H.B. 2020. Engineering biology approaches for food and nutrient production by cyanobacteria Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 67, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Melis, A. , Martinez, D.A.H., Betterle, N. 2023. Perspectives of cyanobacterial cell factories. Photosynthesis Research. [CrossRef]

- Satta, A. Esquirol, L., Ebert, B.E. 2023. Current Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Photosynthetic Bioproduction in Cyanobacteria. [CrossRef]

- Dietsch, M., Behle, A., Westhoff, P., Axmann, I.M. (2021). Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for the photoproduction of the sesquiterpene valencene. Metabolic Engineering Communications 13, e00178. [CrossRef]

- Bolay, P. , Dodge, N., Janssen, K., Jensen, P.E., Lindberg, P. 2024. Tailoring regulatory components for metabolic engineering in cyanobacteria. Physiologia Plantarum.2024;176:e14316. [CrossRef]

- Kukil, K, Lindberg, P. 2024. Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for the improved production of phenylpropanoids. Microbial Cell Factories (2024) 23:57. [CrossRef]

- Chorus, I. , Bartram, J. 1999. Toxic cyanobacteria in water. A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management / edited by Ingrid Chorus and Jamie Bertram. World Health Organization. ISBN 0419239308.

- Mellor, S.B. , Vinde, M.H., Nielsen, A.Z., Hanke, G.T., Abdiaziz, K., Roessler, M.M., Burow, M., Motawia, M.S., Møller, B.L., Jensen, P.E., 2019. Defining optimal electron transfer partners for light-driven cytochrome P450 reactions. Metabolic Engineering 55, 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.Z. , Ziersen, B., Jensen, K., Lassen, L.M., Olsen, C.E., Møller, B.L., Jensen, P.E., 2013. Redirecting Photosynthetic Reducing Power toward Bioactive Natural Product Synthesis. ACS Synthetic Biology 2, 308–315. [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, A. , Gnanasekaran, T., Nielsen, A.Z., Zulu, N.N., Mellor, S.B., Luckner, M., Thøfner, J.F.B., Olsen, C.E., Mottawie, M.S., Burow, M., Pribil, M., Feussner, I., Møller, B.L., Jensen, P.E., 2016. Metabolic engineering of light-driven cytochrome P450 dependent pathways into Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Metabolic Engineering 33, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Berepiki, A. , Hitchcock A., Moore C.M., Bibby T.S., 2016. Tapping the unused potential of photosynthesis with a heterologous electron sink. ACS Synth Biol 5: 1369–1375. [CrossRef]

- Berepiki, A. , Gittins J.R., Moore C.M., Bibby T.S., 2018. Rational engineering of photosynthetic electron flux enhances light-powered cytochrome P450 activity. Synth Biol 3. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Merino, M. , Torrado A., Davis G. A., Röttig A., Bibby T.S., Kramer D.M., Ducat D.C., 2020. Improved photosynthetic capacity and photoprotection via heterologous metabolism engineering in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118: e20215231. [CrossRef]

- Teicher, H.B. , Møller, B.L., Scheller H.V. (2000). Photoinhibition of Photosystem I in field-grown barley (Hordeum vulgare L.): Induction, recovery and acclimation. Photosynthesis Research 64: 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Alasbahi, R.H. , Melzig, M.F., 2012. Forskolin and derivatives as tools for studying the role of cAMP. Pharmazie. 67(1), 5-13. [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, J.A. , Nobuhisa, T., Cui, R., Arya, M., Spry, M., Wakamatsu, K., Igras, V., Kunisada, T., Granter, S.R., Nishimura, E.K., Ito, S., Fisher, D.E., 2006. Topical drug rescue strategy and skin protection based on the role of Mc1r in UV-induced tanning. Nature 443, 340-344. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M. , Nagabhushanam, K., Natarajan, S., Vaidyanathan, P., Karri, S.K., Jose, J.A., 2015. Efficacy and safety of 1% forskolin eye drops in open angle glaucoma - An open label study. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology 29. [CrossRef]

- Mulieri, L.A. , Leavitt, B.J., Martin, B.J., Haeberle, J.R., Alpert, N.R., 1993. Myocardial force-frequency defect in mitral regurgitation heart failure is reversed by forskolin. Circulation 88. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F., Carbonell, V., Cossu, M., Correddu, D., Jones, P.R., 2012. Ethylene Synthesis and Regulated Expression of Recombinant Protein in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLoS ONE 7, e50470. [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.H., Berla, B.M., Pakrasi, H.B. 2015. Fine-tuning of photoautotrophic protein production by combining promoters and neutral sites in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 6857–6863. [CrossRef]

- Stanier, R.Y. , Kunisawa, R., Mandel, M., Cohen-Bazire, G., 1971. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriological reviews 35, 171–205. [CrossRef]

- Forman, V. , Bjerg-Jensen, N., Dyekjær, J.D., Møller, B.L., Pateraki, I., 2018. Engineering of CYP76AH15 can improve activity and specificity towards forskolin biosynthesis in yeast. Microbial Cell Factories 17, 181. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. , Zhang, H., Meng, H., Zhu, Y., Bao, G., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Ma, Y. (2014). Discovery of a super-strong promoter enables efficient production of heterologous proteins in cyanobacteria. Sci. Rep. 4, 4500. [CrossRef]

- Sutradja, L.C. , Dodge, N., Walby, S.L., Butler, N.J., Gnanasekaran, T., Møller, B.L., Jensen, P.E. (2024). Modulation of the MEP Pathway for Overproduction of 13-R-manoyl Oxide in Cyanobacteria. Synthetic Biology and Engineering 2, 10005. [CrossRef]

- Casella, S. , Huang, F., Mason, D., Zhao, G.-Y., Johnson, G.N., Mullineaux, C.W., Liu, L.-N., 2017. Dissecting the Native Architecture and Dynamics of Cyanobacterial Photosynthetic Machinery. Molecular Plant 10, 1434–1448. [CrossRef]

- Lassen, L.M.M. , Nielsen, A.Z., Olsen, C.E., Bialek, W., Jensen, K., Møller, B.L., Jensen, P.E. (2014). Anchoring a plant cytochrome P450 via PsaM to the thylakoids in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002: evidence for light-driven biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 9(7): e102184. [CrossRef]

- Brey, L.F. , Włodarczyk, A.J., Bang Thøfner, J.F., Burow, M., Crocoll, C., Nielsen, I., Zygadlo Nielsen, A.J., Jensen, P.E., 2020. Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for the production of aromatic amino acids and derived phenylpropanoids. Metabolic Engineering 57, 129-139. [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, B. , Englund, E. Nolte, N., Lindberg, P. 2020. Introduction of a green algal squalene synthase enhances squalene accumulation in a strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. [CrossRef]

- Dienst, D. , Wichmann, J., Mantovani, O., Rodrigues, J.S., Lindberg, P. 2020. High density cultivation for efficient sesquiterpenoid biosynthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Scientific Reports 10: 5932. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).