1. Introduction

Reproductive inefficiency, including early embryonic loss, is a serious cause of economic loss in the global cattle industry. Infertility and embryo loss in dairy and beef herds are estimated to reduce profitability by over US

$3.7 billion annually in the United States [

1]. The economic impact of a single pregnancy loss in cattle ranges from US

$90 to US

$1,900, driven by reduced calving rates, extended calving intervals, and increased culling rates [

2]. In Latin America, where beef and dairy exports are crucial components of agricultural Gross Domestic Product (GDP), early pregnancy loss in cattle can translate into millions of dollars in direct and indirect yearly losses, particularly in countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico [

3]. These economic losses are compounded in systems that rely on advanced reproductive technologies such as artificial insemination or embryo transfer, where each failed pregnancy represents not only a biological failure but also a wasted technological investment [

4,

5].

Embryonic loss occurs at a high rate in cattle during the first month [

6]. Days 15 and 28 of gestation are crucial because successful gestation maintenance relies on proper maternal recognition of pregnancy [

6]. Up to 15% of pregnancies are lost between days 16 and 32 post-fertilization [

7]. This failure is primarily associated with insufficient signaling from the embryo, which leads to the premature regression of the corpus luteum and, consequently, the early disruption of pregnancy maintenance. In ruminants, the signaling molecule responsible for maternal recognition is interferon tau (IFN-τ), a trophoblast-derived type I interferon that inhibits endometrial oxytocin receptor expression and suppresses prostaglandin F2α release [

8,

9]. IFN-τ secretion peaks between days 15 and 17 and plays a central role in sustaining luteal function and embryo viability [

10]. During the estrous cycle, progesterone plays a crucial role by inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) by suppressing estradiol receptors in the endometrium. However, if the oocyte is not fertilized, the endometrium starts to secrete PGF2α. This secretion leads to luteolysis, which causes vasoconstriction and apoptosis of luteal cells, ultimately reducing progesterone production [

11]. The decrease in progesterone levels removes the negative feedback on GnRH, initiating a new estrous cycle. For this reason, PGF2α is used in synchronization protocols for animals. The exogenous PGF2α administration induces the lysis of the corpus luteum, decreases serum progesterone levels, and facilitates ovulation of a dominant follicle. This process is essential for artificial insemination and controlled reproduction in cattle [

12]. To assess the effectiveness of PGF2α-induced luteolysis, serum progesterone concentration is typically measured. A level below 0.5 ng/mL indicates complete luteolysis. Throughout the bovine estrous cycle, progesterone and PGF2α are inversely related: PGF2α promotes the corpus luteum regression and the decline of progesterone, signaling the end of the luteal phase and the beginning of a new cycle [[

9,

13]. Furthermore, hormonal tests, such as measuring progesterone in blood or milk, provide accurate insights into the animal's physiological state during the estrous cycle, helping to identify phases such as estrus.

Bovine recombinant IFN-τ (brIFN-τ) has been expressed in various systems, including baculovirus, mammalian, and bacterial platforms [

14,

15]. However, the methylotrophic yeast

Komagataella phaffii (

Pichia pastoris) offers a superior platform for the cost-effective, scalable production of correctly folded and bioactive rbIFN-τ [

16]. Despite efficient production, the complementary application of IFN type I remains limited due to its rapid degradation and short half-life in vivo [

17]. To overcome these barriers, controlled release systems based on polymeric micro and nanoparticles have gained attention in veterinary biotechnology. Biodegradable carriers such as chitosan and poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) enhance protein stability, prolong systemic residence time and reduce dosing frequency [

17,

18,

19]. Chitosan provides mucoadhesive and pH-responsive properties, while PLGA enables tunable degradation profiles and high drug loading capacity [

20]. Notably, semi-solid hydrogel matrices composed of natural polymers like chitosan and starch could serve as localized delivery platforms for intrauterine administration of encapsulated bioactives. Hydrogels allow for sustained release over several days, better mimicking the physiological release pattern of endogenous IFN-τ during early gestation while minimizing systemic degradation and off-target effects [

21].

No published studies have explored brIFN-τ encapsulation within polymeric microcarriers and its incorporation into hydrogels to modulate cattle luteolysis. The present study aimed to i) express and purify biologically active brIFN-τ in Pichia pastoris; ii) formulate and characterize chitosan-based microencapsulation systems; iii) integrate these into starch-chitosan hydrogels for intrauterine delivery; and iv) evaluate their biological activity and release kinetics in vitro, and safety and anti-luteolytic effects in ruminants.

This biotechnological approach could offer a novel complementary strategy for improving reproductive efficiency in cattle, particularly when integrated into artificial insemination or embryo transfer protocols. Providing a single-dose, sustained-release formulation of brIFN-τ, could potentially reduce pregnancy loss rates, lower hormone usage, and increase calving success, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and productive livestock systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modeling by Homology: Computational Procedures

To conduct a homology modeling study, the amino acid sequence of brIFN-τ in FASTA format was uploaded to the Swiss-Model server [

22,

23], a web server designed to allow users to build and evaluate protein homology models easily[

23,

24,

25]. The sequence was analyzed inside the server with BLAST algorithm [

26] and HHBLITS[

27] to obtain all available templates. Afterward, the best templates for generating the models were selected based on optimal coverage and percentage of identity (greater than 70%) with known proteins in the Protein Data Bank [

28,

29].

From the selected templates, the 3D model of the bovine IFN-τ was built by the Swiss-Model web server and validated using the MolProbity algorithm [

30] and QMEAN [

31]. These parameters tell us if the bovine IFN-τ structure predicted by the homology modeling approach is comparable to what would be expected from experimental structures of similar size and structure [

23,

32]. To select the best models, the QMEAN parameter was chosen as a reference value from 0 to -4, where a QMEAN value close to 0 suggests a high quality of the homology-modeled protein structure [

33]. Structural analysis of the generated models and figures was obtained using the Pymol program Version 2.3.0 [

34,

35].

2.2. Docking Assays

To explain the structural basis of the interaction of bovine interferon-tau with its receptors, molecular docking experiments (Docking) were performed [

36,

37,

38,

39]. For the docking experiments, the structure of brIFN-τ was predicted by a homology modeling approach, while the brIFN-τ receptors Q04790 (α/β-Receptor-1) and F1MXT2 (α/β-Receptor-2) were downloaded from the UniProt database [

40], both isolated from the organism Bos taurus (Bovine). The receptors were prepared for docking experiments by adding hydrogen atoms to each amino acid at pH=7.4 (physiological pH), and energy minimization was performed to relax both systems and obtain a local minimum for the structures. This procedure also minimizes the coiled IFN-τ structure predicted by the homology modeling approach using the UCSF ChimeraX program version 1.9 [

41,

42,

43]

Docking experiments were performed with HDOCK [

44,

45], an algorithm that studied protein-protein interactions. The HDOCK algorithm samples the binding modes between two proteins through a global search method based on the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Then, it evaluates the sampled binding modes with an improved scoring function based on iterative knowledge of protein-protein interactions. The Confidence Score variable was also considered for selecting the best poses, which is defined by the following expression: (Equation 1).

In Eq.1, CS represents the Confidence Score, and De represents the Docking Score calculated by the software program. Following the operation of the HDOCK algorithm, when the Confidence Score is greater than 0.7, it is very likely that the two molecules will bind stably; when the Confidence Score is between 0.5 and 0.7, the two molecules could bind, and when the Confidence Score is less than 0.5 it's unlikely that the molecules will bind. On the other hand, the Confidence Score should be used with caution due to its empirical nature. From this procedure, 100 docking poses were obtained, and the six best poses for each complex were selected based on the docking score and confidence score for detailed structural analysis.

2.3. Expression of Bovine Recombinant IFN-τ in the Pichia pastoris System

Bovine recombinant IFN-τ expression was performed following the approach described previously [

46]. A recombinant clone of

Pichia pastoris (Mut+, his3) was cultured in five 250 ml flasks containing 50 ml of YP medium supplemented with glycerol (2% v/v) for 24 h at 30°C and 200 rpm. Then, the culture was centrifuged at 4200 g for 5 min to harvest and resuspend the grown cells in fresh YP medium with methanol at different concentrations (

Table 1).

The cultures were maintained at 30°C, 200 rpm, supplemented with methanol for at least 72 h. The supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 4200 g for 5 min and evaluated by protein electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis using a polyclonal antibody anti-IFN-τ (MyBioSource, Canadá). Expression per condition was quantified by densitometry on SDS-PAGE with a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard curve using Image StudioTM software (Li-cor Biosciences, USA).

To express brIFN-τ in high-density culture, transformed

Pichia pastoris was grown in two flasks (2 L) containing 500 ml of YPG medium each. The cultures were incubated at 30°C with agitation at 250 rpm for 24 hours before being transferred to a 10 L bioreactor (Winpac, USA) containing 4 L of MS medium for fed-batch culture[

46]. The temperature was maintained at 30°C, and the pH was regulated at 4.5 by the automated addition of a 25% ammonia solution (NH

3) and 30% orthophosphoric acid (H

3PO

4). Dissolved oxygen (DO) was maintained between 20 – 40 %. The agitation speed was 500 rpm in the growth phase and 1000 rpm in the induction phase. In the initial phase, glycerol (2% v/v) was supplied as the carbon source. Once the DO and pH values indicated that glycerol had been entirely consumed, methanol (0.5% v/v) was added for the adaptation stage. Upon completion of this stage, the induction of brIFN-τ is initiated by Strategy 4 (

Table 2).

The inductor addition was automated by a methanol sensor (Raven Biotech Inc., Canada). Traces and vitamins were provided at this stage every 40 hour. The supernatant was recovered and immediately stored at -20°C before further analysis.

2.5. Purification of Bovine Recombinant IFN-τ by Ion Exchange

The brIFN-τ purification was performed by sequential cationic and anionic exchange chromatography using an Äkta Prime device (GE Healthcare, USA) controlled and monitored by PrimeView software (GE Healthcare, USA). The supernatant was diluted three times with 50 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5, and subjected to cationic exchange chromatography with a Giga Cap S 650 s matrix (Toyopearl, Tosoh Bioscience, Japan). The column was equilibrated with 50 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5, at 5 mL/min for 8 min. The sample was added at the same flow rate, and the elution was performed with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, at 3 mL/min. The eluted fraction was collected for subsequent purification.

Anionic exchange chromatography was performed on a Giga Cap Q 650 s matrix (Toyopearl, Tosoh Bioscience, Japan). The matrix was equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, at 5 ml/min for 8 min. The sample was added at 3 mL/min. Elution was performed with a saline gradient (1 M NaCl; 50 mM Tris-HCl) at 3 mL/min, and the eluted fractions were collected. The eluted sample was dialyzed on Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM) using a nitrocellulose membrane (12-14 kDa, MWCO) (Fisher Scientific, USA). Finally, the sample was concentrated using a three kDa membrane and an Amicon kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

2.6. Inhibition of the Cytopathic Effect of Mengo Virus in MDBK Cells

The antiviral activity of brIFN-τ was evaluated in Madin-Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK) cells affected with the Mengo virus, using the percentage of cell viability as an indicator of inhibited cytopathic effect. Cells were pre-treated for 24 h with brIFN-τ, followed by 24 h of exposure to viral particles. The tested concentrations were 5.5 ng/L, 1.4 ng/μL, 0.7 ng/μL, 0.3 ng/μL and 0.1 ng/μL of rbIFN-τ. All brIFN-τ treated groups show increased protection against the viral agent, showing higher viability percentages than the negative control but lower than the positive control. There is also an evident decrease in viability percentage when the amount of brIFN-τ administered to the cells decreases. As a result, the respective percentages of cell viability obtained were: 88.04%, 85.44%, 83.5%, 73.26%, and 64.84%. The negative control reflects 50% viability. The data was processed and plotted in GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 for Windows.

2.7. Antiviral Markers Activation Analysis in MDBK Cells

MDBK cells were treated with brIFN-τ at 200, 500, and 1000 ng/mL concentrations for 24 h each. All treatments were performed in triplicate. Then, the total RNA was extracted from the cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified with the Synergy HTX microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). The integrity of the purified RNA was checked by 1 % (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis in Tris-Acetate buffer solution. For complementary DNA synthesis and real-time PCR, the commercial kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) and KAPA SYBR FAST Universal (BIOSYSTEMS), respectively, were used in the AriaMx Real-Time PCR System (Agilent, USA). The results were analyzed using the comparative Ct (2-ΔΔCt) method, and GraphPad Prism 8 software was used to obtain the graphs and statistical analyses. The real-time PCR thermal cycling profile consisted of the reverse transcription step at 50°C for 30 min. Then, the reverse transcriptase inactivation-initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, and subsequently, the amplification step 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 30 s between 56 and 60°C (gene dependent) for the primers annealing step. FA fixed primer concentration of 200 nM was used for the above reaction in a final reaction volume of 12 μL. Specific primers were used to study the relative expression of OAS1, OAS2, PKR, and β-actin genes, which were used as a normalizer. The next sequences corresponding to the forward use of OAS1 5’-aaatagctgggagcggcttg-3’, OAS2 5’-gccttcaatgctctgggc-3’, PKR 5’-tggagacacggaagagctgt-3’, and β-actin 5’-gcccatctatgaggggtacg-3’. The reverse was 5’-ctgtgttcttggggcgacac-3’, 5’-caggcctggctttcaccata-3’, 5’-gatgtactcactgctggagagt-3’, and 5’-atgtcacggacgatttccgc- 3’ for OAS1, OAS2, PKR, and β-actin, respectively.

2.8. Antiviral Activity of brIFN-τ

MDBK cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Costar, USA) at 15 × 103 cells/well in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) + 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The medium was replaced with 100 µL Mengo virus in DMEM + SFB 2%, making serial dilutions 1:10. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, the plates were washed, fixed, and stained with 50 μL/well of 0.5% crystal violet solution and 20% methanol for 15 min. The plates were washed with H2O, and then the crystal violet solution was dissolved with 10% acetic acid (HAc) and 100 µL/well, with agitation at 100 g (xg) (Centrifuge 5702 Eppendorf, Germany) for one hour at room temperature. The absorbance of the plate was read at 590 nm in a Synergy HTX Multi-Mode Reader spectrophotometer (BioTek, USA). The data were fitted to a sigmoid curve that determined the mean maximum effective concentration (EC50) value, the dilution that generates 50% cell death.

The assay was repeated under the same conditions, exposing the cells to varying interferon concentrations before treatment with the Mengo virus. For commercial standards of rhIFNα-2b (Sigma Aldrich Laboratory) [

47]. The experimental design consisted of cell control (cc) wells with untreated cells and virus control (cv) cells without interferon treatment exposed to the Mengo virus. The Mengo virus dilution used was the dilution that caused 50% cell death under the same assay conditions. The data were fitted to a sigmoid curve that determined the value of the EC

50. This dilution generates 50% cell protection and can be defined as the concentration required to obtain a 50% cell protection effect after a specified exposure time. It is also identified with potency [

48,

48]. The EC

50 of a quantal dose-response curve represents the concentration of a compound at which 50% of the population shows a response.

According to the formula:

The data were fitted to a sigmoid curve, and the EC

50 value was calculated for each case, corresponding to the dilution value that generates 50% cell protection. Taking the IFNα-2b standard as a reference, the interferon titer was calculated from the data provided by the standard and considering the initial concentration, according to the formula:

The specific activity was also determined using the formula:

2.9. Encapsulating brIFN-τ Using Chitosan as a Low Molecular Weight Polymer

2.9.1. Microencapsulation of rbIFN-τ in a Chitosan Matrix

The brIFN-τ was expressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris and purified, as previously described by our research group (Sections 2.3-2.5). Microencapsulated low-molecular-weight chitosan was used as a control for incorporation into a semisolid matrix (starch/chitosan, hydrogel). The microencapsulated formulations of the protein brIFN-τ and the control without brIFN-τ were prepared using spray drying technology. Low molecular weight chitosan (50-190 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to deionized water containing 0.5% (v/v) acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for a final concentration of 8.5 g/L. The mixture was continuously stirred at 22°C for 16 h at 300 r.p.m.

2.9.2. Preparation of the Samples to be Microencapsulated

For the empty control (without brIFN-τ protein), 600 mL of 8.5 g/L chitosan solution and 300 mL of 50 mM Tris-base were mixed, and for the sample containing the protein of interest, 600 mL of 8.5 g/L chitosan was mixed with 300 mL of 310 µg/mL brIFN-τ solution. Spray drying was performed in the mini spray-dryer B-290 (Büchi, Switzerland). Three drying sequences were conducted, testing different temperatures and keeping the rest of the parameters constant (

Table 3).

The resultant suspension was fed into the nozzle at a diameter of 0.7 mm. The microparticles were collected and stored at −20°C, and the empty microparticles were used as the negative control. The percentage of yield obtained in the microencapsulation process by spray drying was calculated using the following formula:

Yield (%) = [Mass obtained (g)/ (Sample volume (L) x 8.5 g/L)] x 100, where 8.5 g/L corresponds to the total mass of solids used in the encapsulation.

The morphological characterization and size determination of the microparticles obtained were performed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2.10. Microencapsulated brIFN-τ Release Assay Generated at Three Temperatures

Using microparticles generated by three temperatures (100°C, 120°C, and 140°C), brIFN-τ release time-release assays were performed. For this, 10 mg of encapsulated brIFN-τ was resuspended in 300 μL citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.8). These resuspensions were subjected to slow stirring (100 rpm) at 37°C for 48 h and 100 μL of respective samples were withdrawn at the indicated times. SDS-PAGE and western blot determined the brIFN-τ release at a fixed time.

2.11. Release Assay of brIFN-τ from Chitosan Microparticle from 120 °C

An interferon release assay was conducted using chitosan microparticles produced at 120°C, simulating conditions in the bovine uterus. In a single test tube, 20 mg of microparticles containing IFN-β were dissolved in 300 µl of 50 mM citrate buffer at pH 6.8. The mixture was then incubated at 37°C with continuous agitation at 100 r.p.m. Samples were collected on day 0, 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 26 of the assays. Each sample was centrifuged at 10,000 r.p.m. for 5 min. 100 µl of the supernatant was extracted from each sample, and the same volume of citrate buffer was added to maintain the original condition. Additionally, the release of brIFN-τ was evaluated by quantifying the total protein in each extracted supernatant using microBSA (micro BCATM Protein Assay Kit). Finally, SDS-PAGE and western blotting techniques were employed for further analysis.

2.12. Incorporation of Microencapsulated brIFN-τ Into a Semi-Solid Matrix (Starch/Chitosan, Hydrogel)

Semi-solid matrices were synthesized by chemical cross-linking with genipin. A 1% chitosan solution (0.5% acetic acid, pH 4.5) and an 8% starch solution (heated at 120°C for 15 min) were prepared. Both solutions were mixed in a 30% chitosan/70% starch ratio and kept under 300 r.p.m. agitation for 24 h at 25°C. Genipin was added to a final concentration of 0.05% (v/v), and immediately, the microparticles loaded with brIFN-τ 0.5 µg/mL and the empty microparticles were added. The mixture was kept at 300 r.p.m. agitation for 5 days at 25°C. The hydrogels were transferred to the final molds and subjected to three cycles of freezing (-20°C for 12 h)-thawing (25°C). Finally, they were frozen at -80°C in an ultrafreezer for 2 h and freeze-dried for 24 h. The semi-solid matrices obtained were stored at room temperature until use.

2.13. The Release Assay of Microencapsulated brIFN-τ Associated with Hydrogel

In this case, 6-well plates, maintaining conditions such as the release of brIFN-τ from microencapsulated hydrogels consisting of microencapsulated plus brIFN-τ, soaked in 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.5 and hermetically sealed to prevent water loss by evaporation, were kept under slow stirring at 37°C for 26 days. In this case, 1 mL of each sample was removed at the established times, and immediately, the same volume was replaced with 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.8).

2.14. Drug Safety in the Ovine Model

This trial used 10 clinically healthy and non-pregnant ewes (age: 6 mo.). The animals were acclimated for 15 days before the beginning of the experiment. During this time, to evaluate the individual manifestation of estrus, two synchronization protocols, separated for 7 days, were established, based on the administration of 5 mg/ewe of prostaglandin (dinoprost 0,5%, Lutalyse ™, Zoetis, Chile). After this period, the animals were randomly assigned to two groups of five each. Group 1 (G1) received the intrauterine brIFN-τ, while Group 2 (G2) was left as a control. First, both groups were synchronized with the same prostaglandin protocol. Twenty-four hours after the synchronization and with evident estrus manifestation, the respective treatments were applied. For group 1, each animal was first desensitized with 1 mL of lidocaine (2%) in a low epidural injection (Drag Pharma®, Italy). Then, each ewe was restrained on its back on a gynecological table, and the interferon was administered in the uterine horn with a semen straw injector of 4 mm diameter and, with the help of a speculum, through the cervix. Each animal of both groups was evaluated according to the animal supervision protocol. During the first week, the evaluation was done every 24 h between 08.00 to 08.15 a.m. and later on days 12, 18, and 24. This protocol considers monitoring spontaneous behavior and responding to manipulation, pain, aspects of the fur, secretions, water, and food consumption, assigning punctuation from 0 to 3 to each item [

49,

50]. Besides, to establish possible local effects of the interferon, rectal temperature (digital thermometer, ecomed®, mod. TM-60E, Medisana®, Deutschland) was registered at the exact checking times, as well as the condition of the genitalia: redness, local pain (response to pressure), edema, secretions and vulvar temperature (infrared thermometer, mod. JPD-FR202, Shenzhen Jumper Medical Equipment Co., China). Also, to assess possible variations in blood count, 6 mL samples were taken with the Vacutainer® system from the jugular vein on days 0, 3, 7, and 14.

2.15. Anti-Luteolytic Activity in Cows

Progesterone levels were evaluated using 30 healthy, non-pregnant, hybrid beef cattle cows. The animals were randomly assigned to three groups: Group 1, 10 cows treated with microparticles plus hydrogel without brIFN-τ (Control Group); Group 2, 10 cows treated with brIFN-τ microencapsulated brIFN-τ plus hydrogel (brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel); Group 3, 10 cows treated with brIFN-τ non-encapsulated brIFN-τ plus hydrogel (brIFN-τ hydrogel). All the cows were synchronized with a standard protocol [

51] based on the application on day 0 of an intravaginal progesterone implant (Easy Breed®) and 2 mL of estradiol benzoate (Syntex™) and day 8, extraction of the implant and administration of 0.5 mL of estradiol cypionate (E.C.P., Zoetis, Chile) + 5 mL prostaglandin (Lutalyse ™, Zoetis, Chile).

Between 52 and 56 h after the end of the protocol, all the animals were implanted with the respective semisolid hydrogel via transcervical, using a semen straw injector of 4 mm diameter. Immediately after the implantation, the implant's presence in the uterus was assessed by transrectal ultrasonography examination (Mindray DP50 Vet). Ultrasonographic monitoring in the cows was performed seven times between days 0 and 22 to determine the degradation rate of the implant. Besides, during the first three days after the implant's administration, each animal's rectal temperature was recorded to assess the safety of the treatments. After the synchronization protocol and implant, the serological progesterone levels in the animals were evaluated for 24 days to determine the progesterone curve concerning the estrus cycle and the anti-luteolytic effect. Blood samples were taken in a 9 mL tube without anticoagulant, with a Vacutainer system from the jugular vein on days 0, 7, 15, 19, and 24. The samples were centrifuged at 3,500 r.p.m. for 10 min. the serum was frozen at -20°C in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes until further processing. Finally, the samples were analyzed by radioimmunoassay (RIA) in an external laboratory.

2.16. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted in three sequential steps. First, descriptive statistics were computed to summarize the data distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of Q-Q plots. Normally distributed variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas non-normally distributed variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Second, the assumptions of parametric tests were verified by assessing normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene's test for parametric analyses or Bartlett's test for non-parametric comparisons). Finally, hypothesis testing was performed based on data characteristics: categorical data were analyzed using Pearson's chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test for minor, expected frequencies), while continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test (for normally distributed data) or Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normal distributions). For multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA (with Tukey's post-hoc test) or Kruskal-Wallis test (with Dunn's post-hoc correction) was applied as appropriate. All tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. The complete analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5, ensuring reproducibility of the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L. and J.R.T.; methodology, K.M.; validation, T.I.R., I.C. and F.H.; formal analysis, P.G.; investigation, E.L., F.S., A.V., K.G., J.Y.-T., F.C., F.H.; resources, E.L., I.C. and J.R.T.; data curation, K.M. and P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.; writing—review and editing, M.G-H. and J.Y.-T; visualization, F.C. and M.G.-R.; supervision, E.L. and J.R.T; project administration, E.L.; funding acquisition, E.L. and J.R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

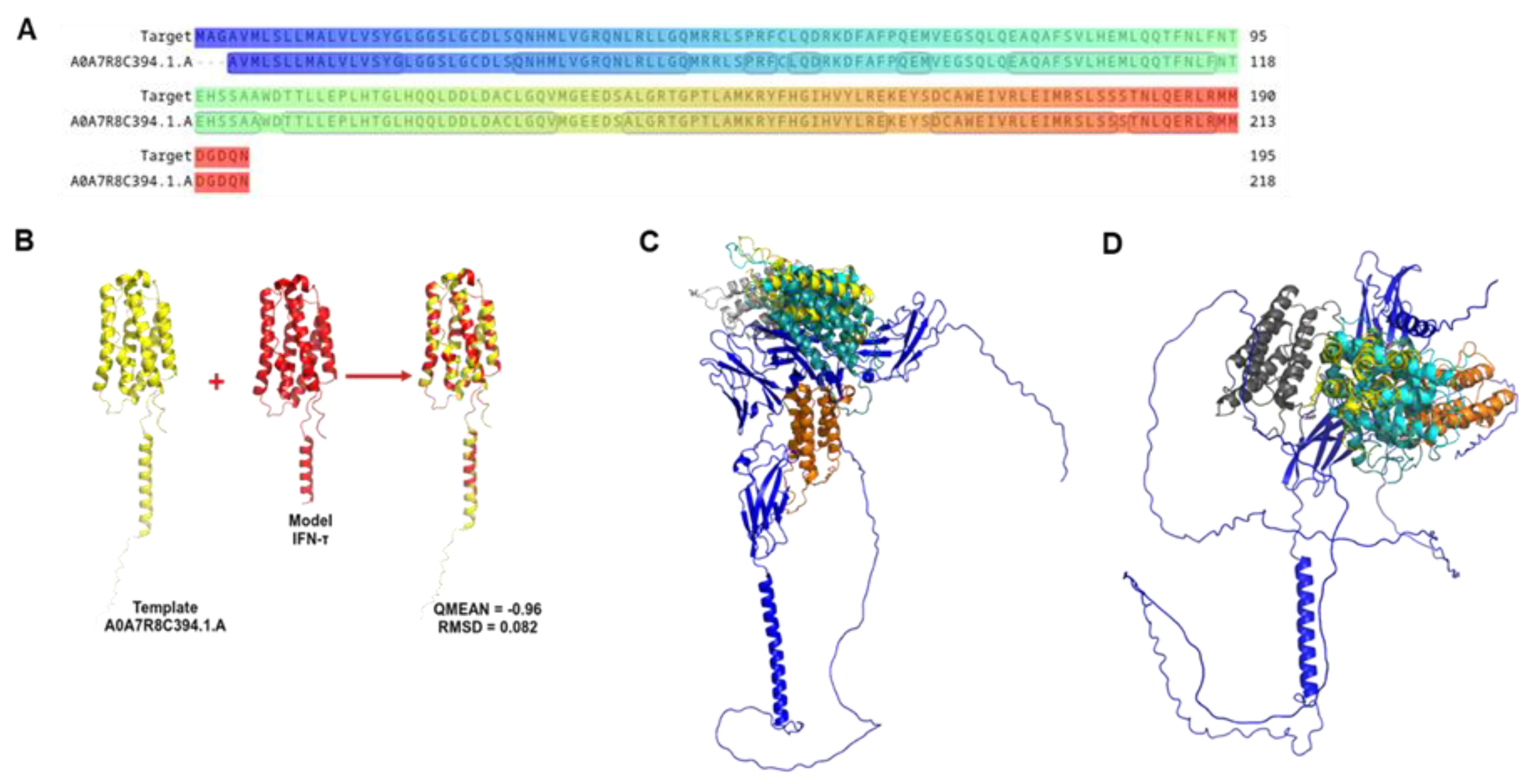

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of IFN-τ sequence and homology modelling. (A) Alignment of the coiled IFN-τ (Target: G3MZ51 · G3MZ51_BOVIN from UniProt) and the Template A0A7R8C394.1.A. (B) The best model obtained from the Homology Modelling and Docking Experiment. (C) Represents the best poses of α/β-Receptor-1 (blue) with interferon tau. (D) Represents the best poses of α/β-Receptor-2 (blue) with IFN-τ.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of IFN-τ sequence and homology modelling. (A) Alignment of the coiled IFN-τ (Target: G3MZ51 · G3MZ51_BOVIN from UniProt) and the Template A0A7R8C394.1.A. (B) The best model obtained from the Homology Modelling and Docking Experiment. (C) Represents the best poses of α/β-Receptor-1 (blue) with interferon tau. (D) Represents the best poses of α/β-Receptor-2 (blue) with IFN-τ.

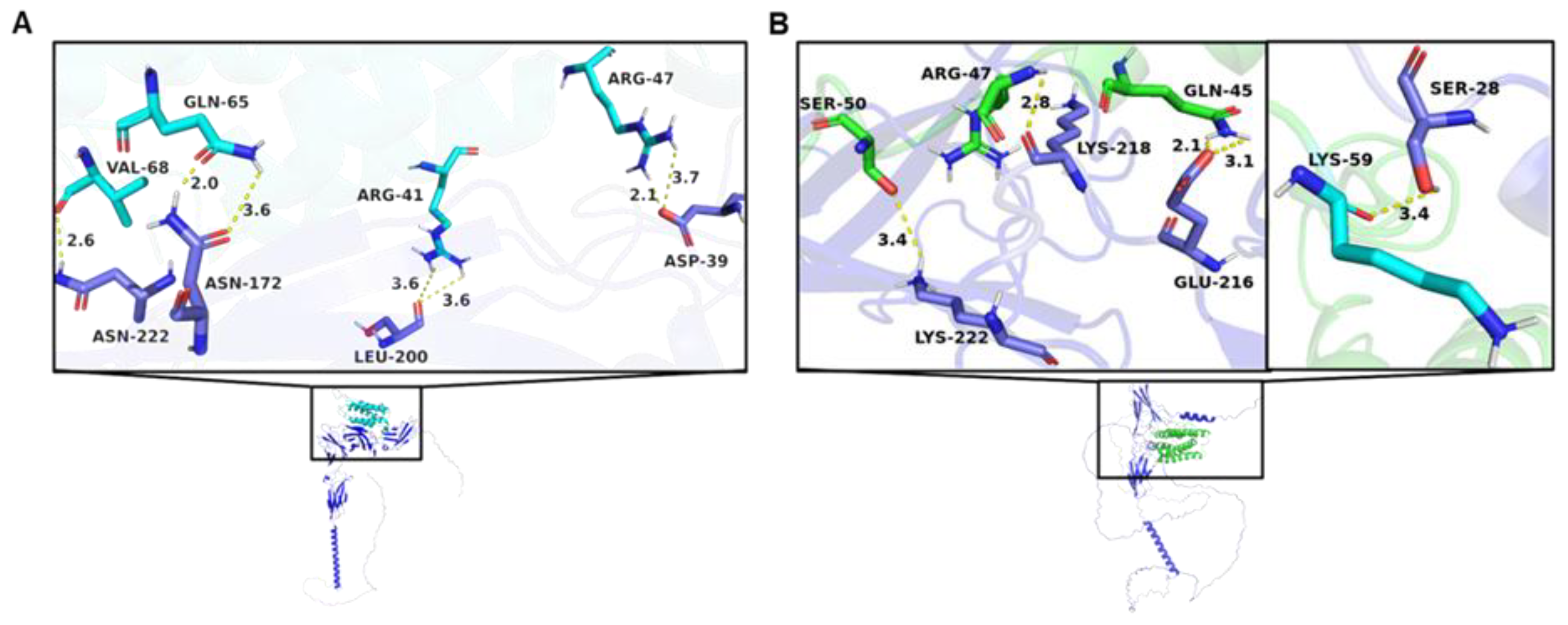

Figure 2.

Interaction between IFN-τ and receptors. (A) Graphical representation of the main interactions between IFN-τ and α/β-Receptor-1. (B) Graphical representation of the main interactions between IFN-τ and α/β-Receptor-2. The amino acids of α/β-Receptor-1 and 2 are shown in dark blue.

Figure 2.

Interaction between IFN-τ and receptors. (A) Graphical representation of the main interactions between IFN-τ and α/β-Receptor-1. (B) Graphical representation of the main interactions between IFN-τ and α/β-Receptor-2. The amino acids of α/β-Receptor-1 and 2 are shown in dark blue.

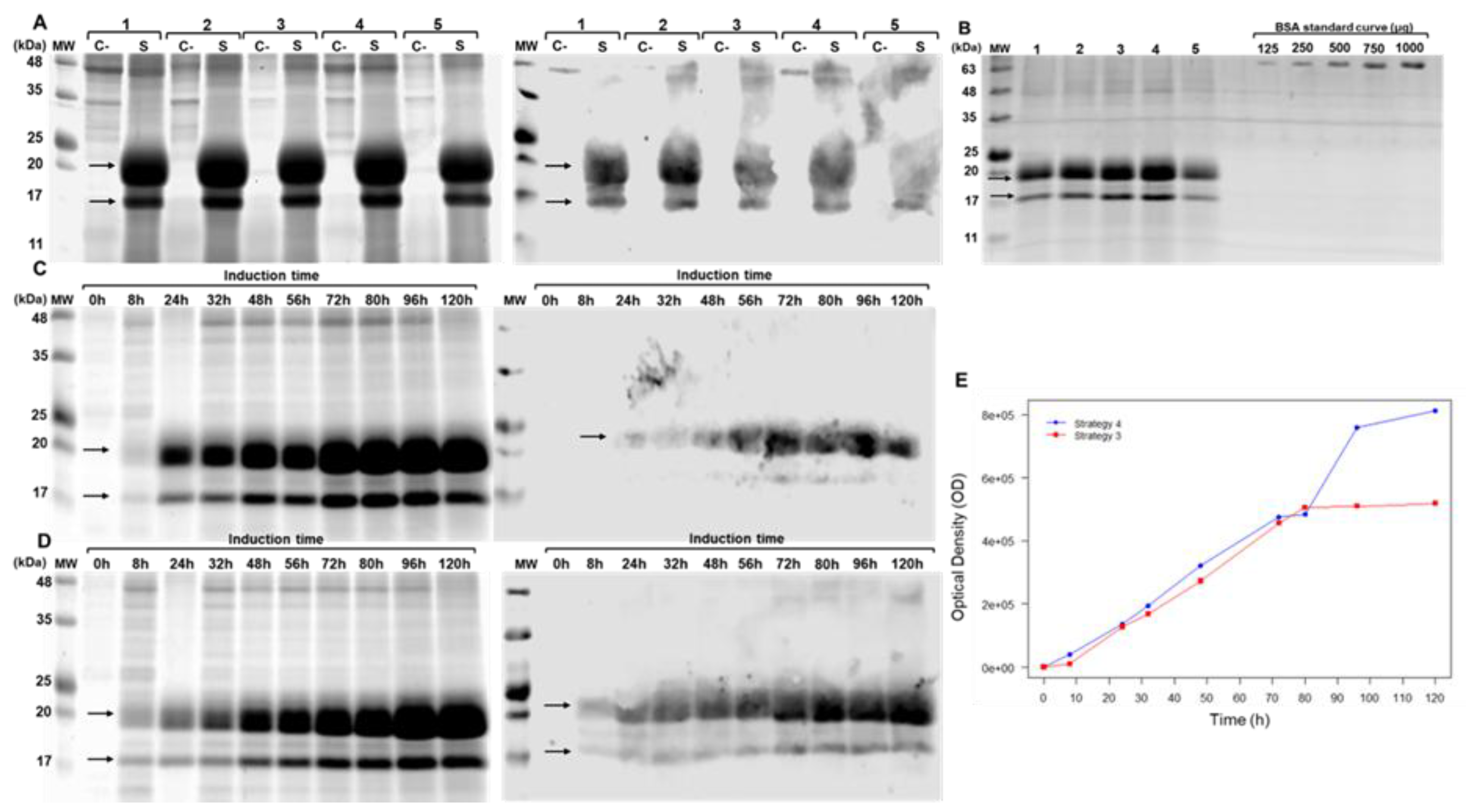

Figure 3.

Evaluation of brIFN-τ expression in Pichia pastoris. (A) SDS-PAGE (right) and Western blot (left) of the Pichia pastoris culture supernatant collected 72 hours post-induction. Samples are labeled as follows: 1: Strategy 1, 2: Strategy 2, 3: Strategy 3, 4: Strategy 4, 5: Strategy 5, C-: Negative Control, S: Sample. The arrows indicate the bands corresponding to recombinant bovine IFN-τ. (B) SDS-PAGE gel was used for quantifying brIFN-τ from the Pichia pastoris culture supernatant and collected 72 hours post-induction. Lanes 1-5 represent culture supernatants from strategies 1-5. A BSA standard curve (μg) was used: 125, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 μg. MW: Molecular Weight markers (kDa). (C) Increasing the culture incubation time to 120 hours in shaken flasks. This section includes an SDS-PAGE (right) and Western blot (left) of the culture supernatant using Induction Strategy 3 at various time points (0h - 120h). (D) SDS-PAGE (right) and Western blot (left) using Strategy 4 at various time points (0h - 120h). (E) brIFN-τ expression curve plotted as a function of time and optical density (OD) for Strategies 3 and 4.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of brIFN-τ expression in Pichia pastoris. (A) SDS-PAGE (right) and Western blot (left) of the Pichia pastoris culture supernatant collected 72 hours post-induction. Samples are labeled as follows: 1: Strategy 1, 2: Strategy 2, 3: Strategy 3, 4: Strategy 4, 5: Strategy 5, C-: Negative Control, S: Sample. The arrows indicate the bands corresponding to recombinant bovine IFN-τ. (B) SDS-PAGE gel was used for quantifying brIFN-τ from the Pichia pastoris culture supernatant and collected 72 hours post-induction. Lanes 1-5 represent culture supernatants from strategies 1-5. A BSA standard curve (μg) was used: 125, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 μg. MW: Molecular Weight markers (kDa). (C) Increasing the culture incubation time to 120 hours in shaken flasks. This section includes an SDS-PAGE (right) and Western blot (left) of the culture supernatant using Induction Strategy 3 at various time points (0h - 120h). (D) SDS-PAGE (right) and Western blot (left) using Strategy 4 at various time points (0h - 120h). (E) brIFN-τ expression curve plotted as a function of time and optical density (OD) for Strategies 3 and 4.

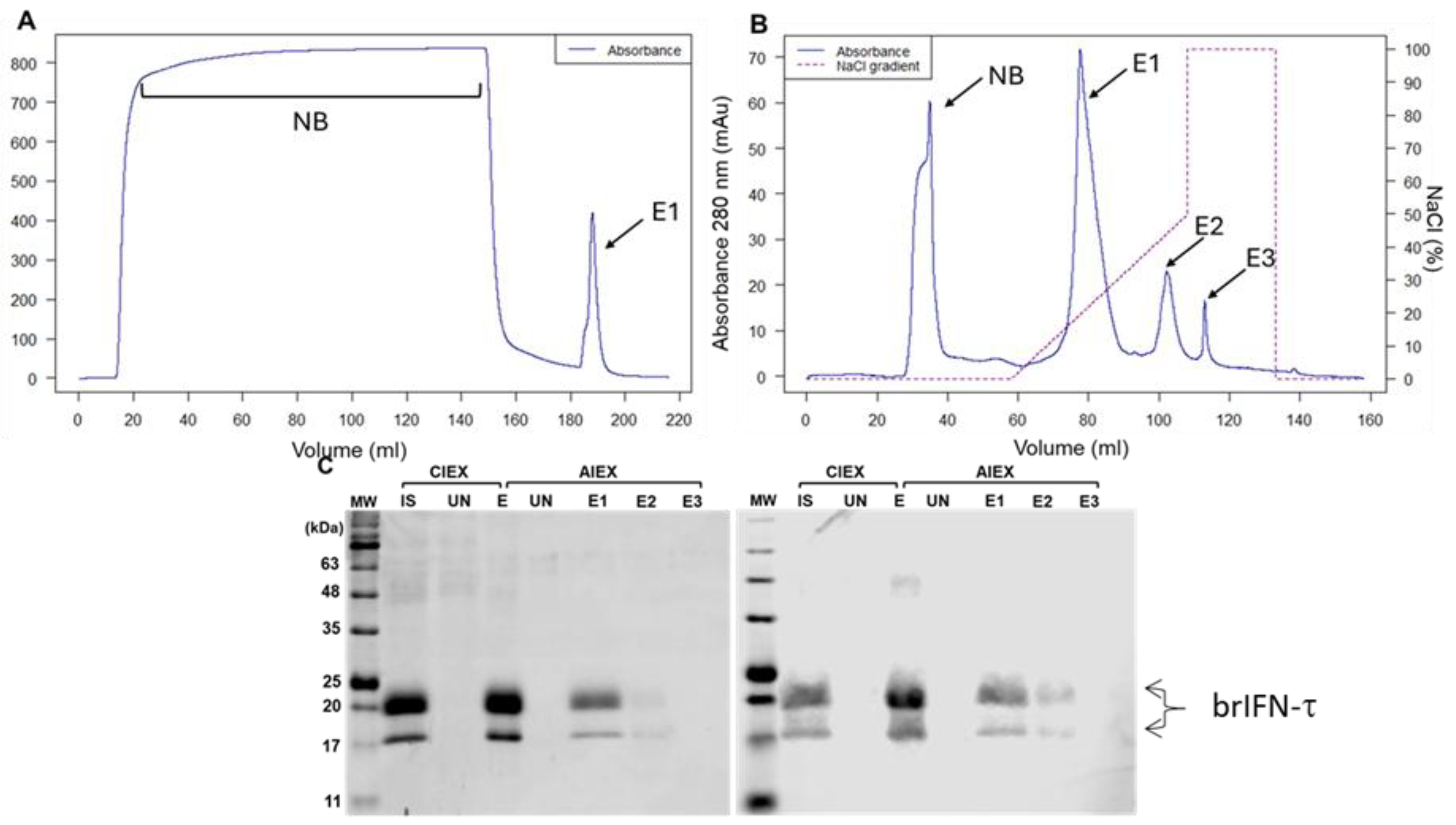

Figure 4.

Evaluation of brIFN-τ purification. (A) Chromatogram from cationic exchange. (B) Chromatogram from anionic exchange. MW: molecular weight, CIEX: cation exchange chromatography, AIEX: anion exchange chromatography, IS: initial sample, UN: unbound proteins to the column, E1: first elution, E2: second elution, E3: third elution fraction. The NaCl gradient used to elute the protein fractions is represented in the graph by a dashed line. (C) SDS-PAGE gel (right) and Western blot (left) of fractions obtained from cationic exchange (S) and anionic exchange (Q) purification.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of brIFN-τ purification. (A) Chromatogram from cationic exchange. (B) Chromatogram from anionic exchange. MW: molecular weight, CIEX: cation exchange chromatography, AIEX: anion exchange chromatography, IS: initial sample, UN: unbound proteins to the column, E1: first elution, E2: second elution, E3: third elution fraction. The NaCl gradient used to elute the protein fractions is represented in the graph by a dashed line. (C) SDS-PAGE gel (right) and Western blot (left) of fractions obtained from cationic exchange (S) and anionic exchange (Q) purification.

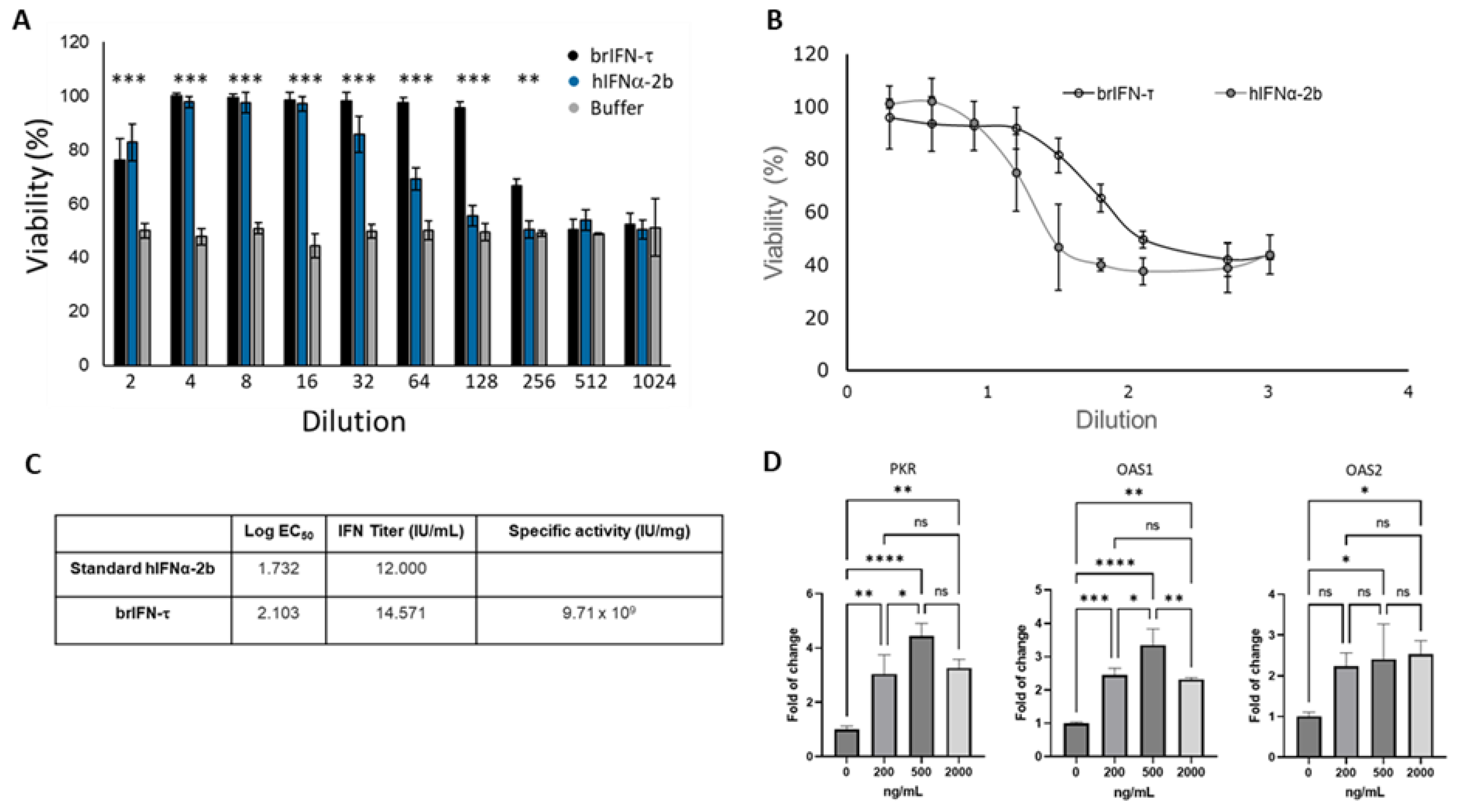

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of brIFN-τ. (

A) Percentage of cell viability in inhibiting the cytopathic effect of the Mengo virus in MDBK cells. (

B) Antiviral activity of brIFN-τ, with IFNα-2b used as a standard for comparison. (

C) Titers of brIFN-τ and specific activity of the standard. (

D) As determined by qPCR, relative expression levels of PKR, OAS1, and OAS2. Data were normalized using the Pfaffl method[

53,

54] with β-actin as the housekeeping gene. Data were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post-test (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of brIFN-τ. (

A) Percentage of cell viability in inhibiting the cytopathic effect of the Mengo virus in MDBK cells. (

B) Antiviral activity of brIFN-τ, with IFNα-2b used as a standard for comparison. (

C) Titers of brIFN-τ and specific activity of the standard. (

D) As determined by qPCR, relative expression levels of PKR, OAS1, and OAS2. Data were normalized using the Pfaffl method[

53,

54] with β-actin as the housekeeping gene. Data were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post-test (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

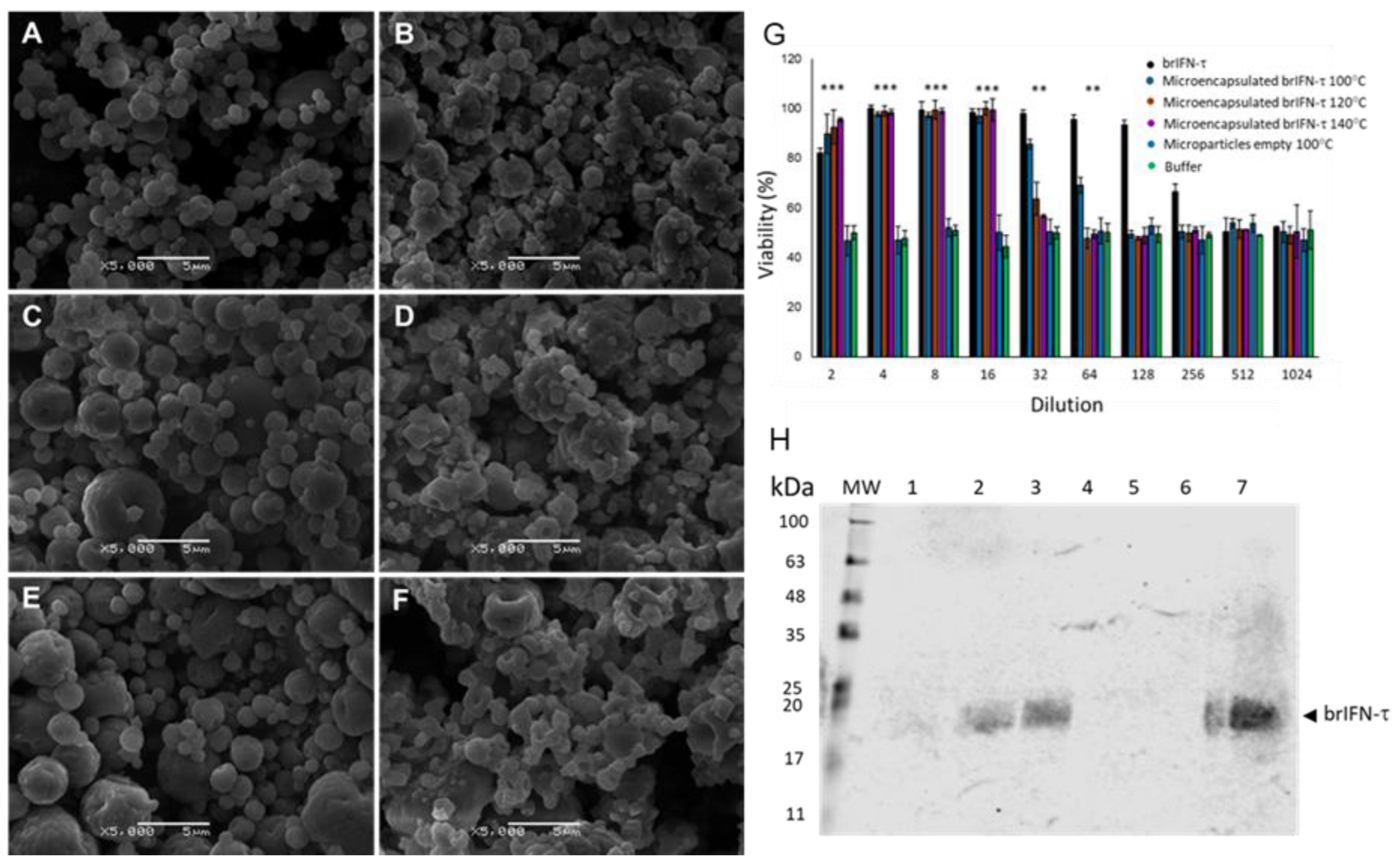

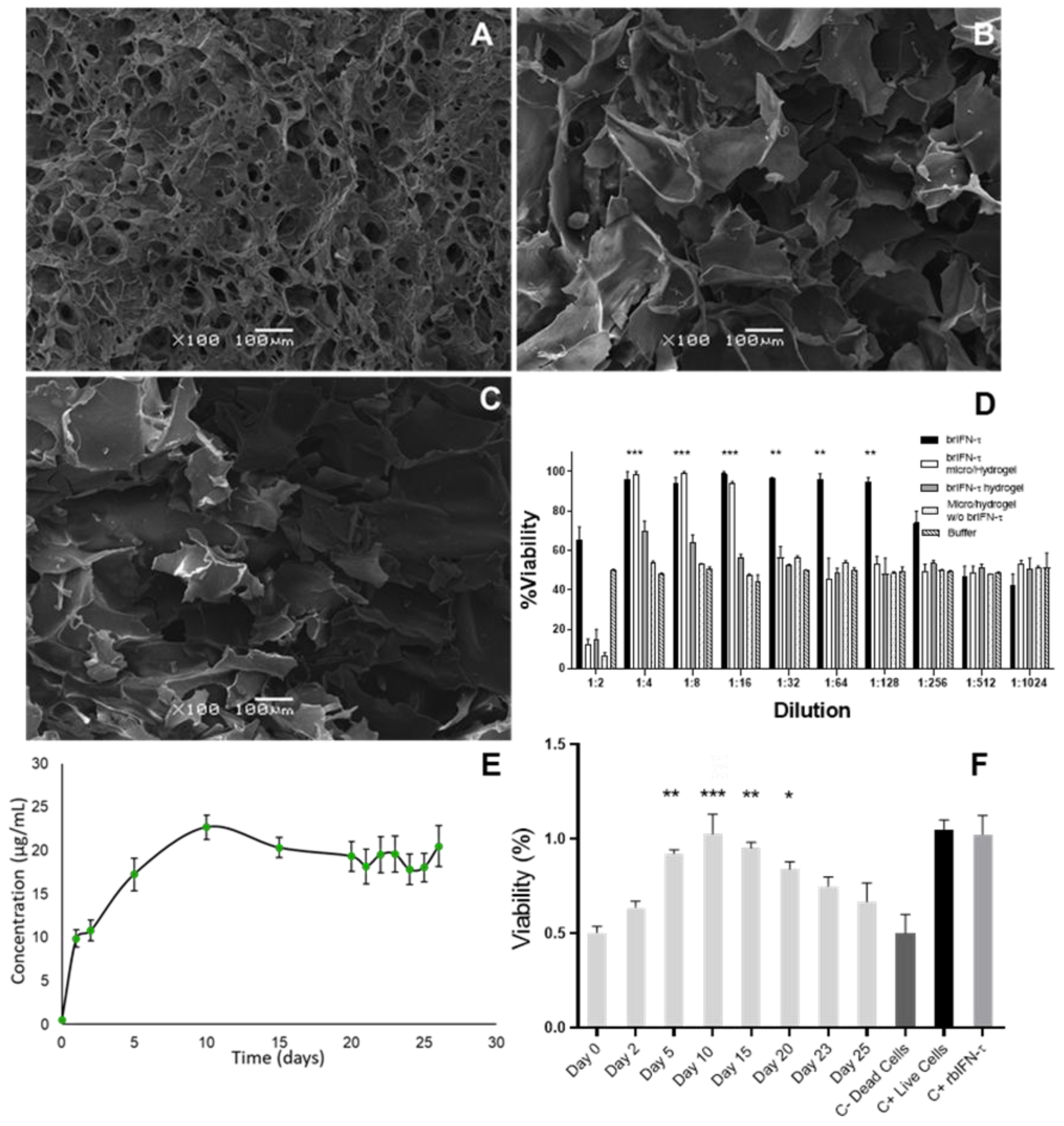

Figure 6.

Microparticles characterization, viability and brIFN-τ release. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) photomicrographs of microparticles generated at different temperatures are presented (A-F). The empty control particles, which do not contain brIFN-τ, were produced at temperatures of 100°C (A), 120°C (C), and 140°C (E). In contrast, brIFN-τ associated chitosan particles were generated at the same temperatures: 100°C (B), 120°C (D), and 140°C (F). The viability percentage was assessed by measuring the inhibition of the cytopathic effect of the Mengo virus in MDBK cells (G). A Western blot analysis of microparticle release samples was conducted at 100°C, 120°C, and 140°C (H). The PPM serves as a molecular weight standard, and lanes 1 to 3 correspond to the release supernatants of particle samples generated at 100°C, 120°C, and 140°C, respectively, after 48 hours of release in a 10 mM citrate solution at pH 6.5 and 37°C. Lanes 4 to 6 represent the release samples of empty microparticles generated at 100°C, 120°C, and 140°C, respectively. Lane 7 shows the brIFN-τ used as a control (20 µg). A polyclonal antibody from Santa Cruz (Fermelo) was utilized in the experiment, and the reaction was visualized using the Alexa 680 rabbit anti-IgG secondary antibody.

Figure 6.

Microparticles characterization, viability and brIFN-τ release. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) photomicrographs of microparticles generated at different temperatures are presented (A-F). The empty control particles, which do not contain brIFN-τ, were produced at temperatures of 100°C (A), 120°C (C), and 140°C (E). In contrast, brIFN-τ associated chitosan particles were generated at the same temperatures: 100°C (B), 120°C (D), and 140°C (F). The viability percentage was assessed by measuring the inhibition of the cytopathic effect of the Mengo virus in MDBK cells (G). A Western blot analysis of microparticle release samples was conducted at 100°C, 120°C, and 140°C (H). The PPM serves as a molecular weight standard, and lanes 1 to 3 correspond to the release supernatants of particle samples generated at 100°C, 120°C, and 140°C, respectively, after 48 hours of release in a 10 mM citrate solution at pH 6.5 and 37°C. Lanes 4 to 6 represent the release samples of empty microparticles generated at 100°C, 120°C, and 140°C, respectively. Lane 7 shows the brIFN-τ used as a control (20 µg). A polyclonal antibody from Santa Cruz (Fermelo) was utilized in the experiment, and the reaction was visualized using the Alexa 680 rabbit anti-IgG secondary antibody.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of the daily release of brIFN-τ from microparticles generated at 120°C. (A) Total protein quantification from the released samples daily in the resuspension buffer (50 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.8) was performed using the micro-BCA™ Protein Assay Kit. (B) A Western blot analysis was conducted to determine the release of brIFN-τ from chitosan microparticles. The lanes represent the days supernatant samples containing brIFN-τ were extracted. A polyclonal anti-IFN-τ antibody produced in rabbits (Santa Cruz) was utilized, and the reaction was visualized using a secondary antibody, anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 680. The Li-COR Biosciences Odyssey scanner system, along with Image Studio Lite version 5.2 analysis software, was used for visualization and analysis.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of the daily release of brIFN-τ from microparticles generated at 120°C. (A) Total protein quantification from the released samples daily in the resuspension buffer (50 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.8) was performed using the micro-BCA™ Protein Assay Kit. (B) A Western blot analysis was conducted to determine the release of brIFN-τ from chitosan microparticles. The lanes represent the days supernatant samples containing brIFN-τ were extracted. A polyclonal anti-IFN-τ antibody produced in rabbits (Santa Cruz) was utilized, and the reaction was visualized using a secondary antibody, anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 680. The Li-COR Biosciences Odyssey scanner system, along with Image Studio Lite version 5.2 analysis software, was used for visualization and analysis.

Figure 8.

Scheme of hydrogel generation.

Figure 8.

Scheme of hydrogel generation.

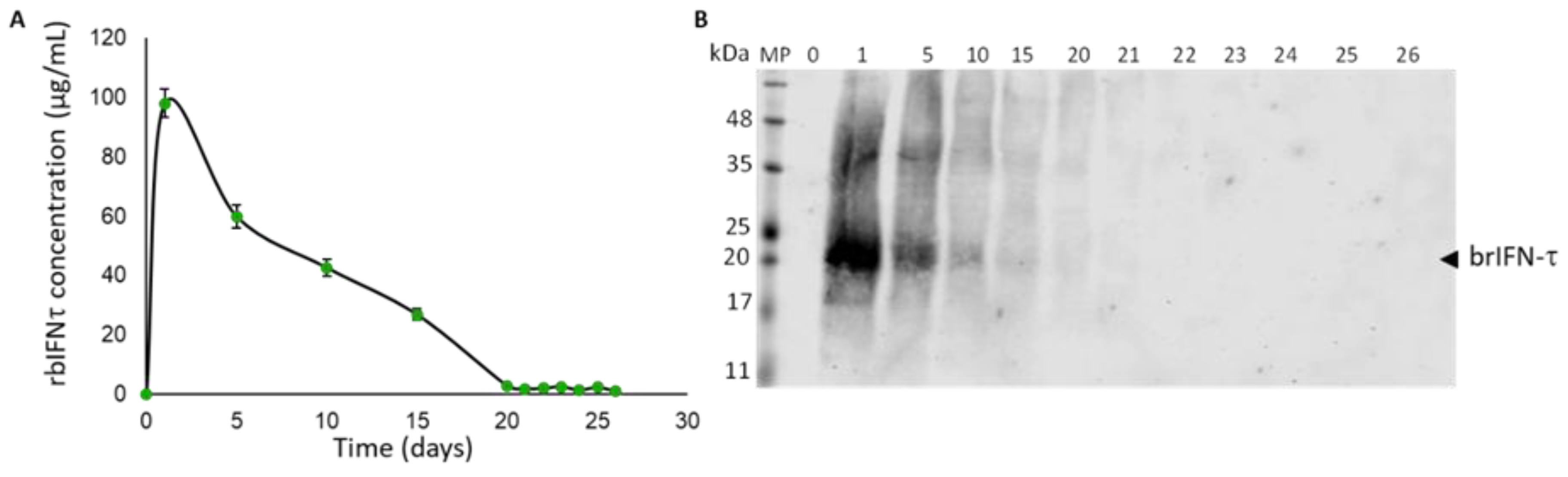

Figure 9.

Hydrogel characterization and brIFN-τ release assay. Photomicrographs were taken using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of the hydrogel samples. (A) Hydrogel mixed with an equivalent of 2 mg of brIFN-τ microencapsulated. (B) Hydrogel mixed with 2 mg of non-microencapsulated soluble brIFN-τ. (C) Hydrogel mixed with empty microparticles. All microparticles were prepared at 120°C. The brIFN-τ, both microencapsulated and soluble, was added on day 2 of the hydrogel elution scheme, immediately after adding genipin. (D) Viability percentage was determined by measuring the inhibition of the cytopathic effect of the Mengo virus assay in MDBK cells using samples released 48 hours after each sample preparation. (E) A graphical representation illustrates the daily release of hydrogel mixed with brIFN-τ microencapsulated over a period of 26 days. Total protein quantification was achieved using the Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit. The x-axis corresponds to the day of sampling. (F) This section represents the antiviral effect of brIFN-τ in MDBK cell cultures using ½ dilutions. The samples of hydrogel containing brIFN-τ microencapsulated were utilized for this assay. Results were compared to a negative control of dead cells. Data were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post-test (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Hydrogel characterization and brIFN-τ release assay. Photomicrographs were taken using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of the hydrogel samples. (A) Hydrogel mixed with an equivalent of 2 mg of brIFN-τ microencapsulated. (B) Hydrogel mixed with 2 mg of non-microencapsulated soluble brIFN-τ. (C) Hydrogel mixed with empty microparticles. All microparticles were prepared at 120°C. The brIFN-τ, both microencapsulated and soluble, was added on day 2 of the hydrogel elution scheme, immediately after adding genipin. (D) Viability percentage was determined by measuring the inhibition of the cytopathic effect of the Mengo virus assay in MDBK cells using samples released 48 hours after each sample preparation. (E) A graphical representation illustrates the daily release of hydrogel mixed with brIFN-τ microencapsulated over a period of 26 days. Total protein quantification was achieved using the Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit. The x-axis corresponds to the day of sampling. (F) This section represents the antiviral effect of brIFN-τ in MDBK cell cultures using ½ dilutions. The samples of hydrogel containing brIFN-τ microencapsulated were utilized for this assay. Results were compared to a negative control of dead cells. Data were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post-test (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

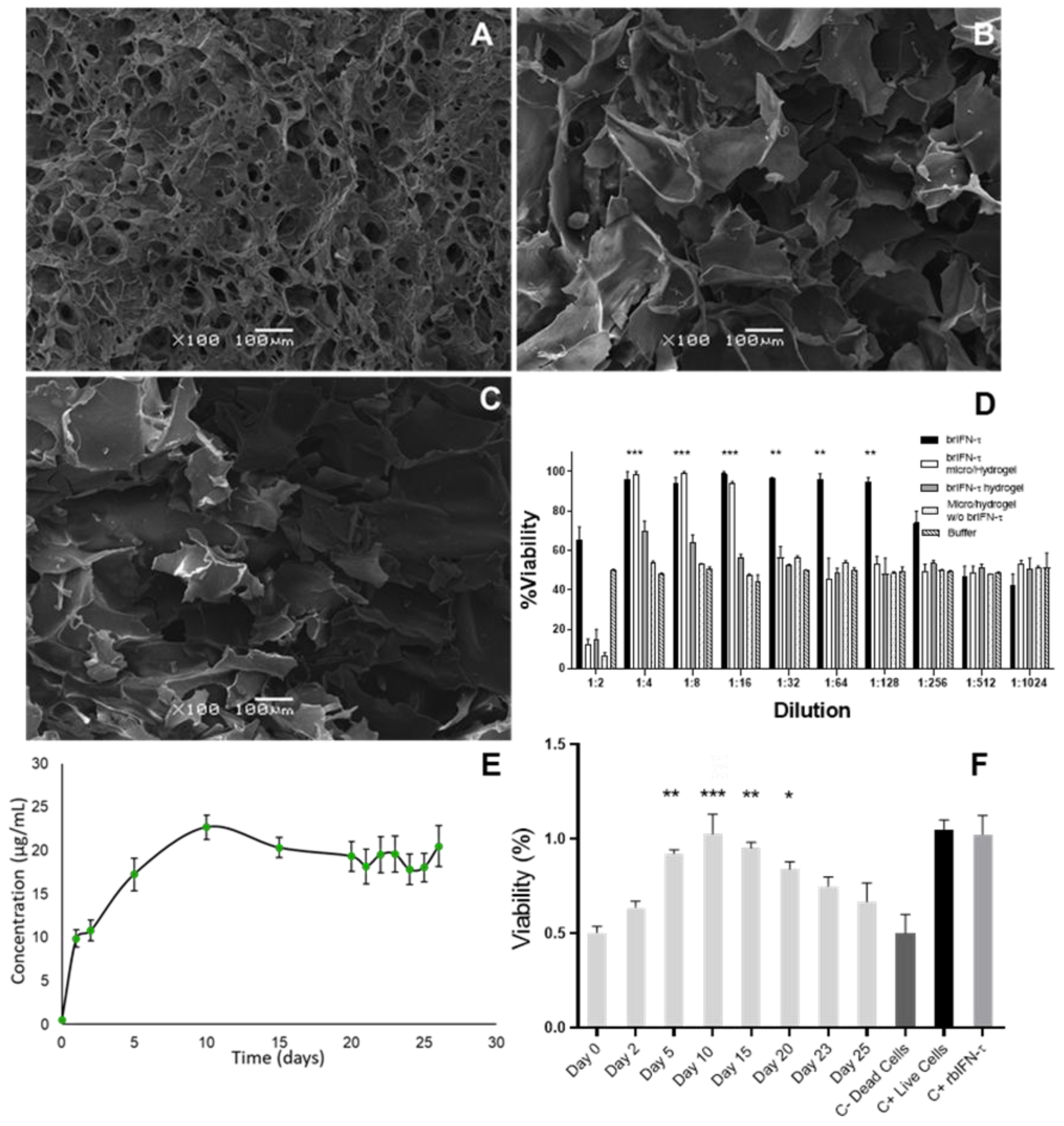

Figure 10.

Drug safety evaluation in the ovine model. (A) Schema of the Ovine Assay. (B) External evaluation of genitalia in the ewes of the study at time 0. Oedema and mucosal secretion (yellow arrow). (C) Vulvar edema and erythematous mucosa are due to an oestrum. (D) Evolution of the rectal temperature in ewes treated with brIFN-τ microencapsulated in hydrogel (brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel) v/s the control group (Micro/hydrogel w/o brIFN-τ). (F) Variation of the vulvar temperature in ewes was treated in the same way. D. Results were compared concerning the negative control of dead cells. No significant differences were registered between the groups.

Figure 10.

Drug safety evaluation in the ovine model. (A) Schema of the Ovine Assay. (B) External evaluation of genitalia in the ewes of the study at time 0. Oedema and mucosal secretion (yellow arrow). (C) Vulvar edema and erythematous mucosa are due to an oestrum. (D) Evolution of the rectal temperature in ewes treated with brIFN-τ microencapsulated in hydrogel (brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel) v/s the control group (Micro/hydrogel w/o brIFN-τ). (F) Variation of the vulvar temperature in ewes was treated in the same way. D. Results were compared concerning the negative control of dead cells. No significant differences were registered between the groups.

Figure 11.

Anti-luteolytic activity and serum progesterone levels after brIFN-τ delivery via hydrogel in cattle. (A) Scheme of progesterone assay in cows. (B) Transrectal ultrasound evaluation of cows from groups 1, which uses microparticles/hydrogel without brIFN-τ, 2 (brIFN-τ microencapsulated with hydrogel), and 3 (non-encapsulated brIFN-τ plus, hydrogel). Visible implant in uterine horn (red arrow); uterine horn (green circle); anechoic center of the uterine horn, indicating the absence of solid contents (green arrow). Ultrasonograph Mindray®, DP50-Vet, linear probe 8,5 MHz. (C) Mold used to generate semi-solid matrix (hydrogel) and hydrogel examples. (D) Progesterone (P4) levels in the three groups: control, brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel, and brIFN-τ hydrogel (nonencapsulated). The levels of P4 on day 19 stand out, with significant differences between brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel concerning the control group.

Figure 11.

Anti-luteolytic activity and serum progesterone levels after brIFN-τ delivery via hydrogel in cattle. (A) Scheme of progesterone assay in cows. (B) Transrectal ultrasound evaluation of cows from groups 1, which uses microparticles/hydrogel without brIFN-τ, 2 (brIFN-τ microencapsulated with hydrogel), and 3 (non-encapsulated brIFN-τ plus, hydrogel). Visible implant in uterine horn (red arrow); uterine horn (green circle); anechoic center of the uterine horn, indicating the absence of solid contents (green arrow). Ultrasonograph Mindray®, DP50-Vet, linear probe 8,5 MHz. (C) Mold used to generate semi-solid matrix (hydrogel) and hydrogel examples. (D) Progesterone (P4) levels in the three groups: control, brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel, and brIFN-τ hydrogel (nonencapsulated). The levels of P4 on day 19 stand out, with significant differences between brIFN-τ micro/hydrogel concerning the control group.

Table 1.

Methanol concentration per induction strategy over time.

Table 1.

Methanol concentration per induction strategy over time.

| Strategy |

0h |

24h |

48h |

| 1 |

0.3 % |

0.4 % |

0.5 % |

| 2 |

0.5 % |

0.75 % |

1 % |

| 3 |

0.5 % |

1 % |

1.5 % |

| 4 |

0.5 % |

1 % |

1 % |

| 5 |

1 % |

1 % |

1 % |

Table 2.

Optimal strategies of methanol concentration.

Table 2.

Optimal strategies of methanol concentration.

| Strategy |

0h |

|

24h |

48h |

72h |

96h |

| 3 |

0.5 % |

|

1 % |

1.5 % |

1.5 % |

1.5 % |

| 4 |

0.5 % |

|

1 % |

1 % |

1 % |

1 % |

Table 3.

Microencapsulation of chitosan control and chitosan/ brIFN-t mixture. Spray drying in the mini–Spray Dryer b-290 of the vacuum chitosan samples at different temperatures, keeping constant feed, aspiration, and airflow.

Table 3.

Microencapsulation of chitosan control and chitosan/ brIFN-t mixture. Spray drying in the mini–Spray Dryer b-290 of the vacuum chitosan samples at different temperatures, keeping constant feed, aspiration, and airflow.

| Inlet temperature (°C) |

Inlet temperature (°C) |

Aspiration (%) |

Feed Flow rate (mL/min) |

Air Flow rate (L/h) |

| 100 |

63 |

95 |

6.0 |

536 |

| 120 |

76 |

95 |

6.0 |

536 |

| 140 |

88 |

95 |

6.0 |

536 |

Table 4.

Template search results for building the IFN-τ model.

Table 4.

Template search results for building the IFN-τ model.

| Template |

Seq Identity (%) |

Found by |

Method |

Seq Similarity |

Coverage |

Description |

| A0A7R8C394.1.A |

100.00 |

AFDB |

AlphaFold v2 |

0.61 |

0.98 |

Interferon 1BE10 |

| 1b5l.1.A |

68.82 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.50 |

0.87 |

Interferon Tau |

| 1b5l.1.A |

68.64 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.50 |

0.87 |

Interferon tau |

| 3oq3.1.A |

53.61 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.45 |

0.85 |

Interferon alpha-5 |

| 3se4.1.B |

66.08 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.50 |

0.88 |

Interferon omega-1 |

| 3se4.1.B |

66.07 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.50 |

0.86 |

Interferon omega-1 |

| 3oq3.1.A |

54.94 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.45 |

0.83 |

Interferon alpha-5 |

| 2kz1.1.A |

56.10 |

HHblits |

NMR |

0.46 |

0.84 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 7e0e.1.A |

50.30 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.43 |

0.86 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 7e0e.1.A |

51.85 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.44 |

0.83 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 2lag.1.B |

56.10 |

HHblits |

NMR |

0.46 |

0.84 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 4z5r.1.A |

56.10 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.46 |

0.84 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 1itf.1.A |

56.10 |

HHblits |

NMR |

0.46 |

0.84 |

Interferon Alpha-2a |

| 2hym.1.B |

56.10 |

HHblits |

NMR |

0.46 |

0.84 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 3ux9.1.A |

57.67 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.46 |

0.84 |

Interferon alpha-1/13 |

| 1au1.1.A |

34.15 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.36 |

0.84 |

Interferon-Beta |

| 3ux9.1.A |

56.63 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.45 |

0.85 |

Interferon alpha-1/13 |

| 3se3.1.B |

54.55 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.45 |

0.85 |

Interferon alpha 2b |

| 3s9d.1.A |

54.55 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.45 |

0.85 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 1au1.1.B |

34.15 |

HHblits |

X-ray |

0.36 |

0.84 |

Interferon-Beta |

| 2lms.1.A |

55.76 |

HHblits |

NMR |

0.45 |

0.85 |

Interferon alpha-2 |

| 6jhd.1.A |

56.36 |

HHblits |

NMR |

0.45 |

0.85 |

Interferon alpha-8 |

| 6jhd.1.A |

57.06 |

BLAST |

NMR |

0.45 |

0.84 |

Interferon alpha-8 |

| 1au1.1.A |

37.50 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.39 |

0.70 |

Interferon-beta |

| 1au1.1.B |

37.50 |

BLAST |

X-ray |

0.39 |

0.70 |

Interferon-beta |

Table 5.

Docking and confidence scores of top five IFN-τ–α/β receptor complex poses predicted by HDOCK.

Table 5.

Docking and confidence scores of top five IFN-τ–α/β receptor complex poses predicted by HDOCK.

| Poses |

IFN-τ-α/β-Receptor-1 |

IFN-τ-α/β-Receptor-2 |

| Docking Score |

Confidence Score |

Docking Score |

Confidence Score |

| Pose-1 |

-259.84 |

0.9000 |

-271.82 |

0.9196 |

| Pose-2 |

-249.51 |

0.8798 |

-270.79 |

0.9180 |

| Pose-3 |

-240.63 |

0.8597 |

-266.38 |

0.9111 |

| Pose-4 |

-238.00 |

0.8532 |

-256.82 |

0.8944 |

| Pose-5 |

-236.13 |

0.8485 |

-251.72 |

0.8844 |

Table 6.

Chitosan/brIFN-τ encapsulation performance at varying temperatures under constant feed, suction, and airflow.

Table 6.

Chitosan/brIFN-τ encapsulation performance at varying temperatures under constant feed, suction, and airflow.

| Sample |

Mass (g) |

Yield (%) |

| 100 °C |

0.96 |

56.1 |

| 120 °C |

1.14 |

66.1 |

| 140 °C |

1.16 |

67.8 |

Table 7.

Performance of empty chitosan encapsulation at varying temperatures with constant feed, suction, and airflow.

Table 7.

Performance of empty chitosan encapsulation at varying temperatures with constant feed, suction, and airflow.

| Sample |

Mass (g) |

Yield (%) |

| 100 °C |

0.96 |

56.1 |

| 120 °C |

1.14 |

66.1 |

| 140 °C |

1.16 |

67.8 |

Table 8.

Hemogram results in sheep on days 0, 3, 7, and 14 of safety trial.

Table 8.

Hemogram results in sheep on days 0, 3, 7, and 14 of safety trial.

| |

Hematocrit |

Total Leukocytes |

| Group |

ID |

Day 0 |

Day 3 |

Day 7 |

Day 14 |

Day 0 |

Day 3 |

Day 7 |

Day 14 |

| Control Group |

32 |

9.39 |

9.2 |

8.9 |

9.49 |

9400 |

7500 |

6000 |

5910 |

| 33 |

10.6 |

11.1 |

11.57 |

11.38 |

5940 |

6500 |

8700 |

11900 |

| 36 |

10.34 |

10.2 |

10.14 |

9.84 |

6340 |

11000 |

16450 |

7600 |

| 34 |

10.18 |

10.6 |

9.77 |

10.93 |

6700 |

10900 |

11670 |

11800 |

| 42 |

10.28 |

11.3 |

11.97 |

11.66 |

6000 |

6900 |

7920 |

7420 |

| Treated Group |

27 |

8.39 |

8.6 |

8.58 |

8.85 |

5300 |

7200 |

8670 |

6880 |

| 30 |

9.17 |

10.1 |

10.29 |

9.95 |

4000 |

4300 |

5300 |

5000 |

| 48 |

9.17 |

9.9 |

10.41 |

9.61 |

4000 |

5400 |

6340 |

4420 |

| 71 |

11.21 |

12.2 |

12.28 |

11.79 |

10460 |

10800 |

11510 |

11800 |

| 483 |

8.91 |

9.3 |

9.59 |

9 |

8110 |

9500 |

9710 |

7310 |