Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Different Bio-Stimulants on Phytochemical Parameters in Citrus Plants Under Salt Stress

2.1.1. Effects of Bio-Stimulants on Chlorophyll Levels Under Salinity Stress

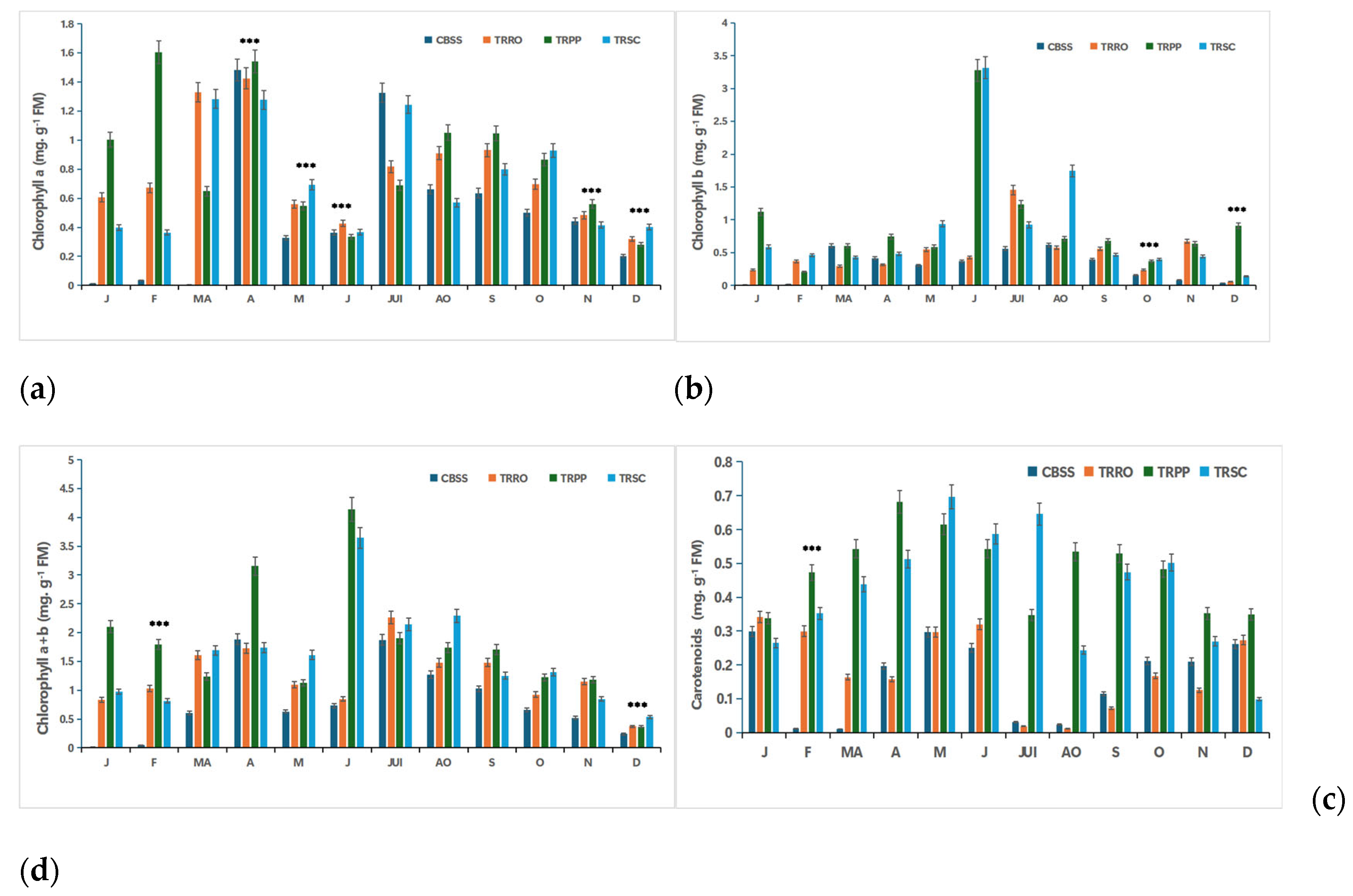

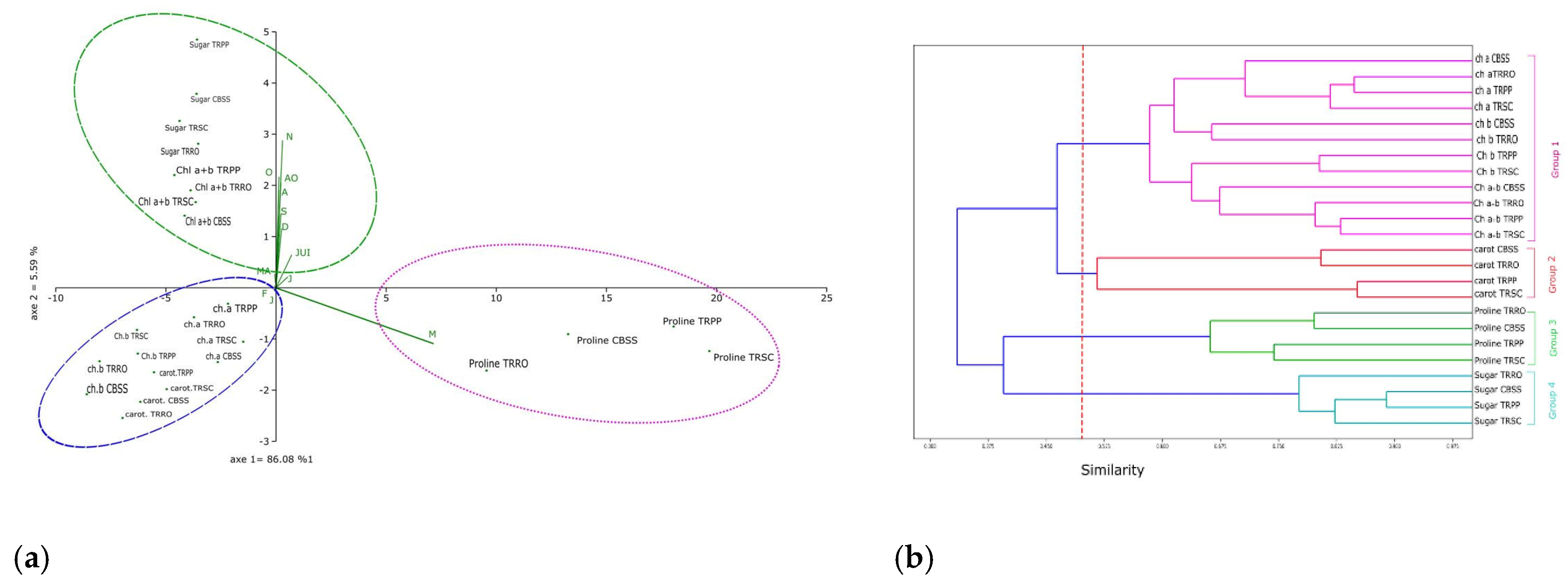

- Chlorophyll, a crucial photosynthetic pigment, is essential for capturing light energy and plant growth. The results of this study indicated that the Rosemary’s (TRRO), Pinyon pine (TRPP) and shrimp chitin’s (TRSC) bio-stimulants led to significant variations in the accumulation of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), total chlorophyll (a + b), and carotenoids (Carot), compared to the salt-stressed control (CBSS) (Figure 1).

- All bio-stimulants showed higher chlorophyll a (Chl a) contents compared to the CBSS throughout the year, especially during the growth period (March to July). Whereas, in the later block, an increase was observed in April and July, reaching 1.48 mg. g-1 FM. Early in the season, TRPP noted the highest peak in April 1.60 mg. g-1 FM. While TRSC, showed significant values in July, October and December. However, TRRO displayed moderate peaks all over the year, with its highest level observed in April (1.42 mg. g-1 FM) (Figure 1a).

- The stressed control block (CBSS) showed the lowest chlorophyll b levels throughout the year. While TRPP noted a notable increase, especially in January (1.12 mg.g-1 FM), June (3.27 mg.g-1 FM) and December (0.91 mg.g-1 FM), followed by TRSC, with peaks in June and August (3.31 mg.g-1 FM and 1.74 mg.g-1 FM). In contrast, TRRO showed moderate but consistent levels, reaching 1.45 mg. g-1 FM in July and 0.67 mg.g-1 FM in November (Figure 1b).

- Total chlorophyll (Chl a + b) was positively influenced by bio-stimulants compared to CBSS. TRPP exhibited important total chlorophyll levels, particularly at the start of the season, reaching 3.15 mg. g-1 FM in April and 4.14 mg. g-1 FM in June. TRRO and TRSC evolved in a similar way. The maximum value of total chlorophyll on TRSC was noted in June (3.64 mg. g-1 FM), followed by TRRO in July (2.26 mg. g-1 FM) (Figure 1c).

- Carotenoides are stress indicators that usually increase under salt stress. In the present study, TRPP and TRSC exhibited higher carotenoid contents for most of the season, reaching their maximum values in May (~0. 7mg.g-1 FM). Then, they decreased but they maintained higher levels than those of TRRO and CBSS. TRRO noted stable and moderate carotenoid levels throughout the year, reaching a maximum value of 0. 34mg.g-1 FM, indicating better stress management (Figure 1d).

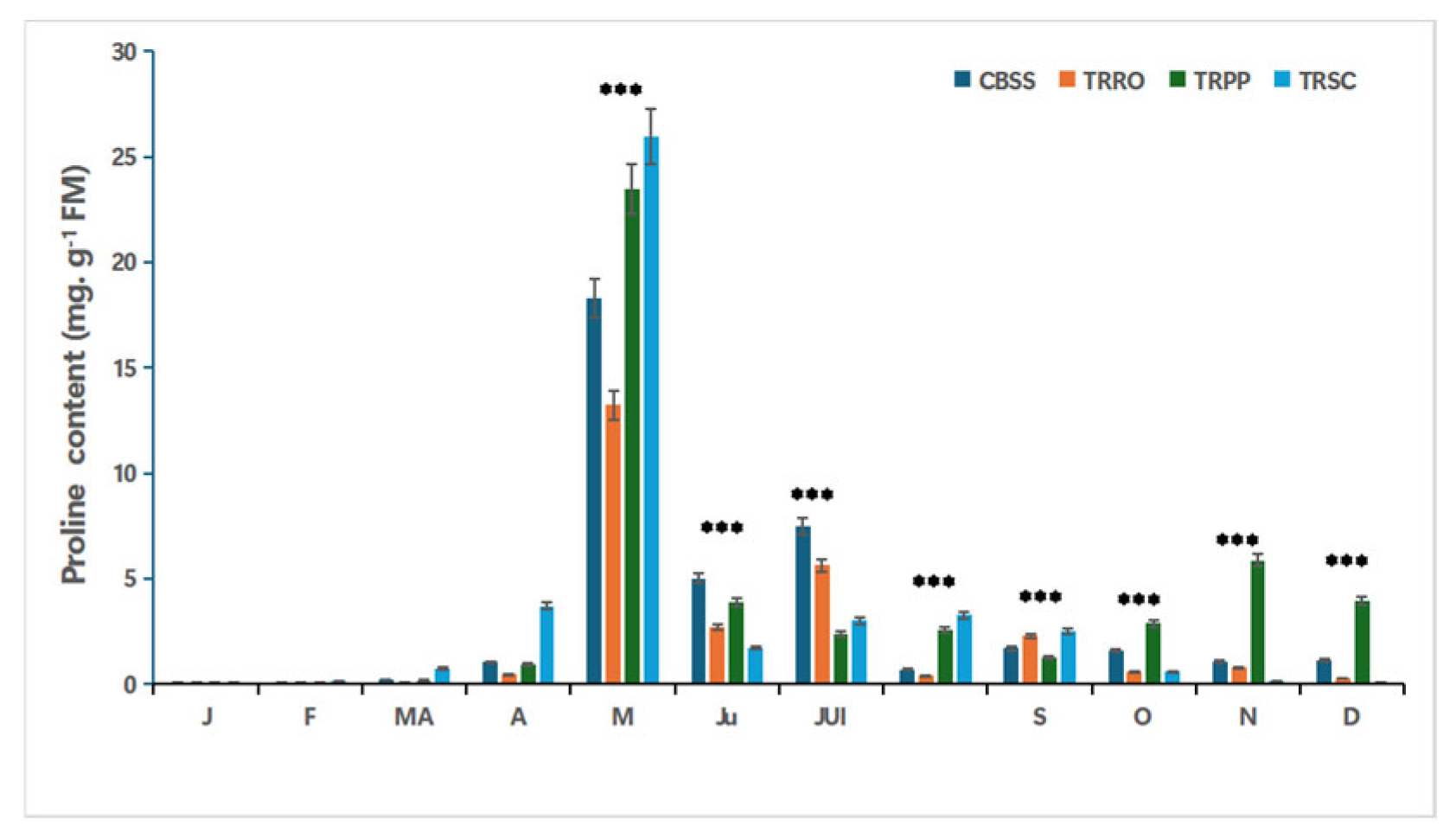

2.1.2. Effects of Bio-Stimulants on Proline Content Under Salinity Stress

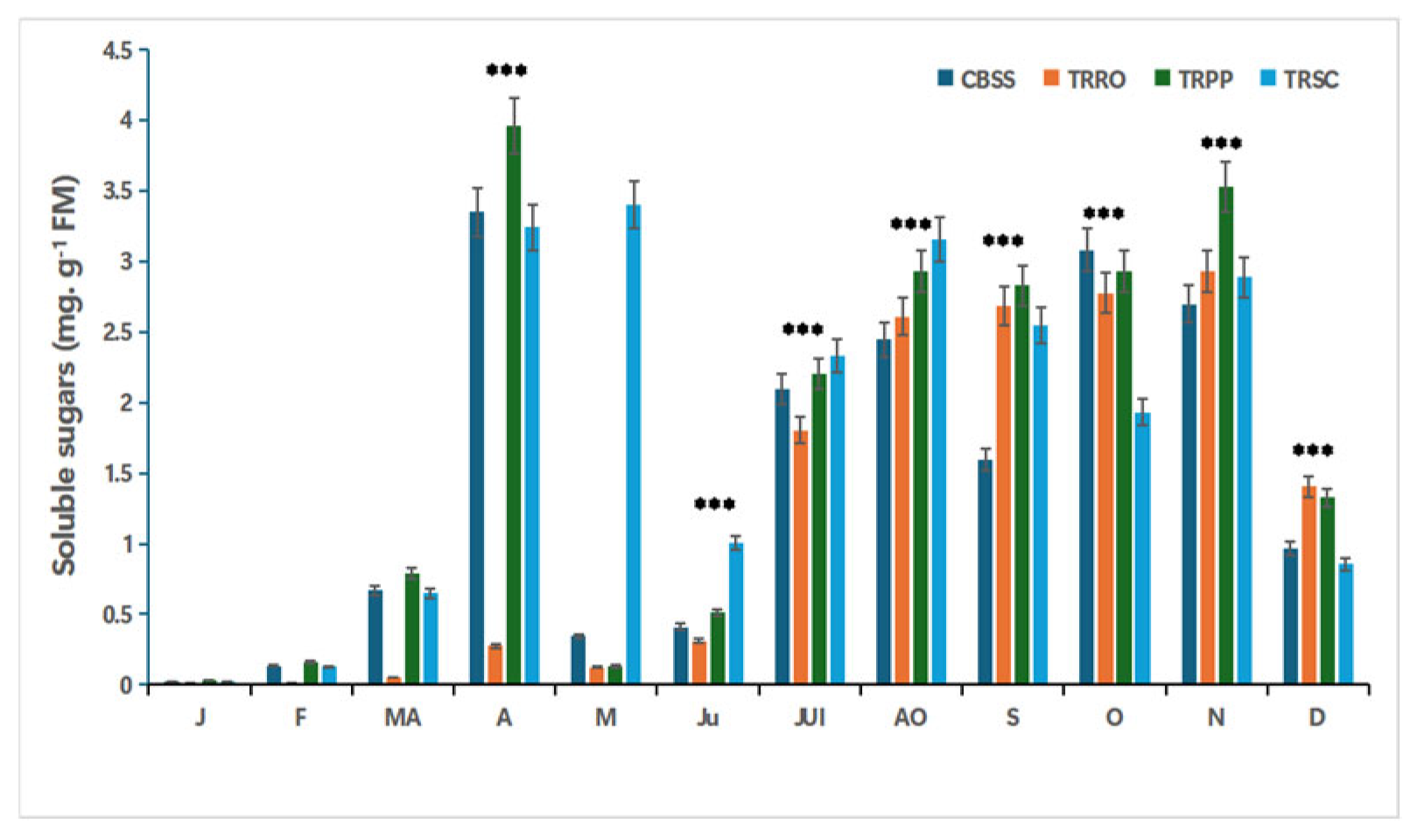

2.1.3. Effects of Bio-Stimulants on Soluble Sugars Content Under Salinity Stress

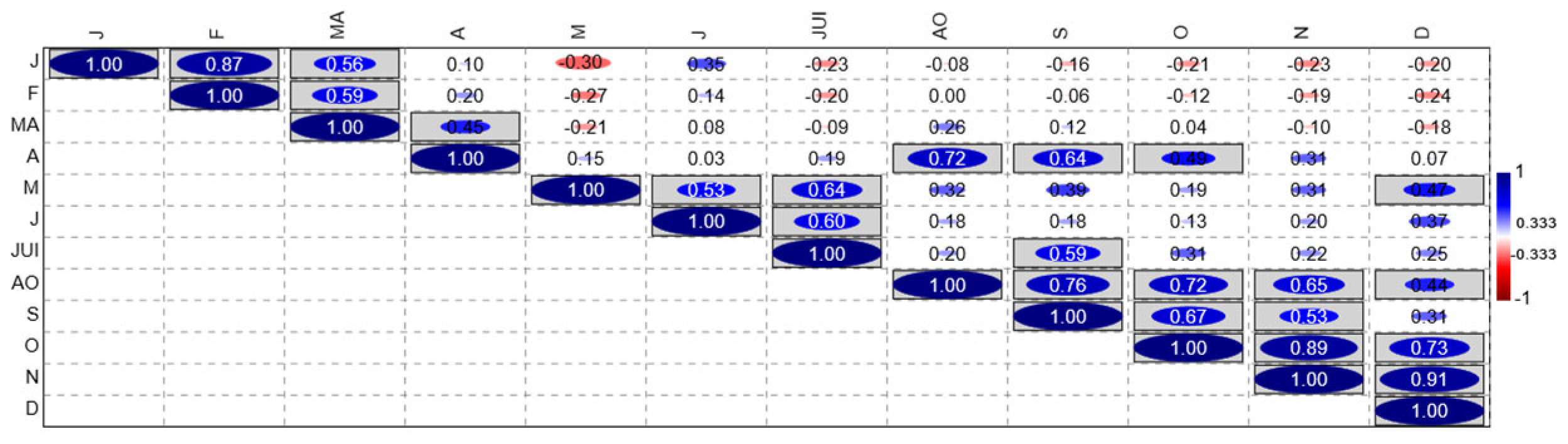

2.1.4. Correlation Matrix Between Different Phytochemical Parameters

2.1.5. Clustering and Grouping of Physicochemical Parameters Under Salt Stress

2.2. Effect of Different Bio-Stimulants on Soil Elements in Citrus Plants Under Salt Stress

2.3. Valorisation of Rosemary's Bio-Stimulant (TRRO) Under Salt Stress

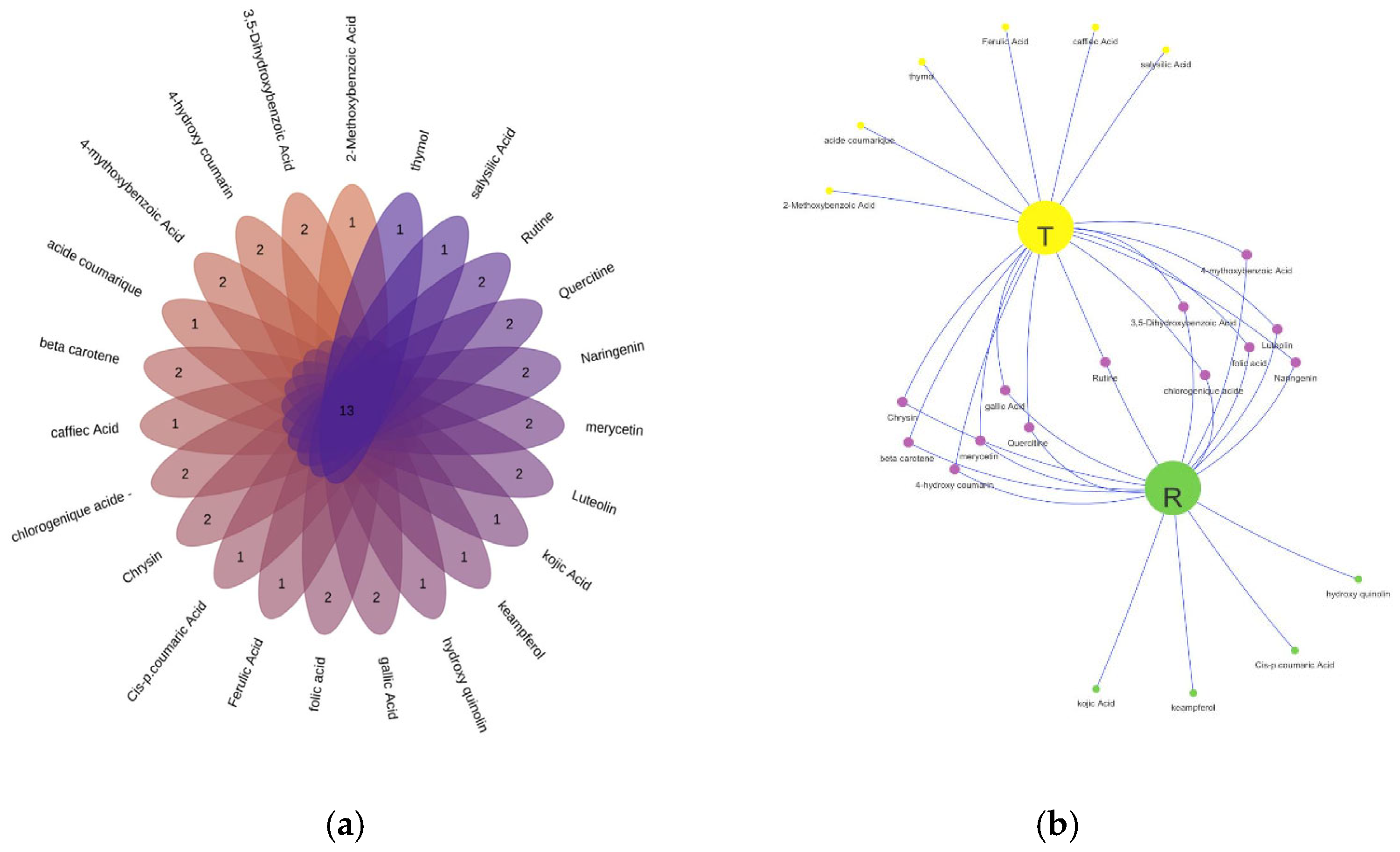

2.3.1. Venn Analysis of Secondary Metabolites Under Salt Stress

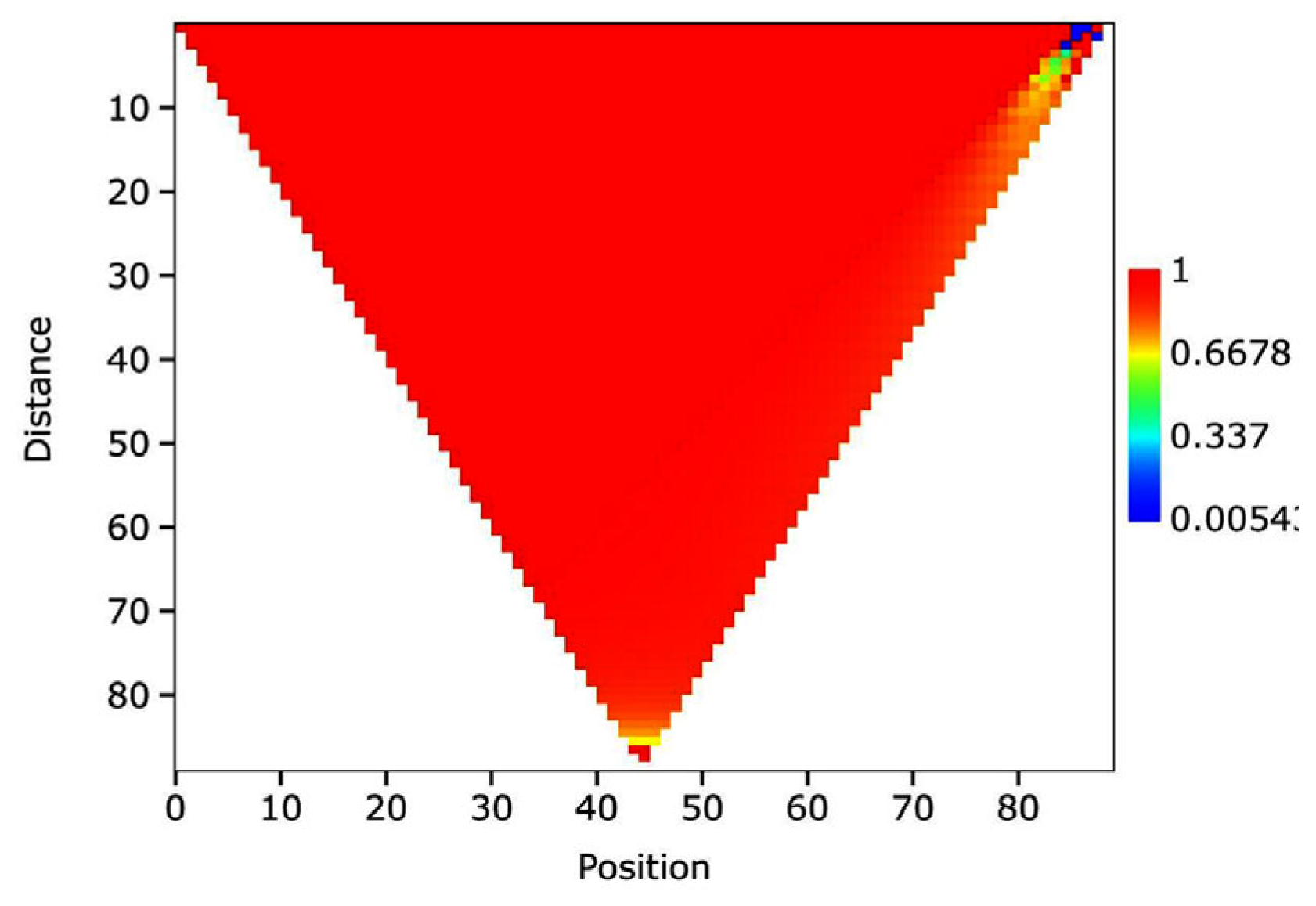

2.3.2. Mantel Scalogram

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Site

4.2. Extraction and Preparation of Bio-Stimulant

4.2.1. Rosemary's Bio-Stimulant

4.2.2. Shrimp Chitin’s Bio-Stimulant

4.2.3. Pinion Pin’s Bio-Stimulant

4.3. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments in Citrus Leaves

- Chlorophyll a concentration(mg/L) = 12.7× OD665 - 2.69 × OD649

- Chlorophyll b concentration(mg/L) = 22.9× OD649 - 4.86 × OD665

- Total chlorophyll concentration (mg/L) = 8.02× OD6655 +20.20× OD649

- Photosynthetic pigment content (mg/g) = (photosynthetic pigment concentration × extraction volume) / sample mass

4.4. Determination of Free Proline Content

4.5. Determination of Soluble Sugars

4.6. Soil Analysis

4.7. LC-MS /MS Methode

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DTPA | Diethylene Triamine Pentaacetic Acid |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CNCC | National Company of Statutory Auditors |

References

- Citrus Genetics and Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Fruits; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 403–436 ISBN 978-3-319-91943-0.

- Kalita, B.; Roy, A.; Annamalai, A.; Ptv, L. A Molecular Perspective on the Taxonomy and Journey of Citrus Domestication. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2021, 53, 125644. [CrossRef]

- Citrus Fruit Fresh and Processed Statistical Bulletin 2020.

- OEC (2023) The Observatory of Economic Complexity 2025.

- CNCC (2015) Bulletin Des Variétés Des Agrumes. Centre National de Contrôle et de Certification Des Semences et Plants, Alger.

- INRAA (2006) Rapport National Sur l’état Des Ressources Phytogénétiques Pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture. Institut National de La Recherche Agronomique d’Algérie, Alger.

- Citrus Production Conditions in Algeria: Drought and Irrigation Issues. In Greening of Industry Networks Studies; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 61–83 ISBN 978-3-031-63792-6.

- United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Citrus: World Markets and Trade; Foreign Agricultural Service/USDA: Washington, DC, USA, January 2025. 2025.

- Jha, U.C.; Bohra, A.; Jha, R.; Parida, S.K. Salinity Stress Response and ‘Omics’ Approaches for Improving Salinity Stress Tolerance in Major Grain Legumes. Plant Cell Rep 2019, 38, 255–277. [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Dodd, I.C.; Martinez-Cutillas, A. Contrasting Physiological Effects of Partial Root Zone Drying in Field-Grown Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Monastrell) According to Total Soil Water Availability. Journal of Experimental Botany 2012, 63, 4071–4083. [CrossRef]

- Numan, M.; Bashir, S.; Khan, Y.; Mumtaz, R.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Khan, A.L.; Khan, A.; AL-Harrasi, A. Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria as an Alternative Strategy for Salt Tolerance in Plants: A Review. Microbiological Research 2018, 209, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Dourmap, C.; Roque, S.; Morin, A.; Caubrière, D.; Kerdiles, M.; Béguin, K.; Perdoux, R.; Reynoud, N.; Bourdet, L.; Audebert, P.-A.; et al. Stress Signalling Dynamics of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain and Oxidative Phosphorylation System in Higher Plants. Annals of Botany 2020, 125, 721–736. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Species and Antioxidants. Redox Biology Is a Fundamental Theme of Aerobic Life. Plant Physiology 2006, 141, 312–322. [CrossRef]

- Oukarroum, A.; Bussotti, F.; Goltsev, V.; Kalaji, H.M. Correlation between Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Photochemistry of Photosystems I and II in Lemna Gibba L. Plants under Salt Stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2015, 109, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.V. Salinity and Citriculture. Tree Physiology 1993, 12, 195–216. [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.A. Effect of NaCl Concentrations in Irrigation Water on Growth and Polyamine Metabolism in Two Citrus Rootstocks with Different Levels of Salinity Tolerance. Acta Physiol Plant 2007, 30, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, D.; Martinez, V.; Cerda, A. Citrus Response to Salinity: Growth and Nutrient Uptake. Tree Physiology 1997, 17, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, L.; Dutt, M.; Vincent, C.; Grosser, J. Salinity-Induced Physiological Responses of Three Putative Salt Tolerant Citrus Rootstocks. Horticulturae 2020, 6, 90. [CrossRef]

- Kalal, P. Impact of Salinity Stress on Citrus Production and Its Alleviation Strategies.

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative Stress, Antioxidants and Stress Tolerance. Trends in Plant Science 2002, 7, 405–410. [CrossRef]

- Asada, K. Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Chloroplasts and Their Functions. Plant Physiology 2006, 141, 391–396. [CrossRef]

- Larkindale, J.; Knight, M.R. Protection against Heat Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage in Arabidopsis Involves Calcium, Abscisic Acid, Ethylene, and Salicylic Acid. Plant Physiology 2002, 128, 682–695. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Anand, U.; López-Bucio, J.; Radha; Kumar, M.; Lal, M.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Dey, A. Biostimulants and Environmental Stress Mitigation in Crops: A Novel and Emerging Approach for Agricultural Sustainability under Climate Change. Environmental Research 2023, 233, 116357. [CrossRef]

- Di Sario, L.; Boeri, P.; Matus, J.T.; Pizzio, G.A. Plant Biostimulants to Enhance Abiotic Stress Resilience in Crops. IJMS 2025, 26, 1129. [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, A.V.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Buffagni, V.; Senizza, B.; Pii, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Lucini, L. Foliar Application of Different Vegetal-Derived Protein Hydrolysates Distinctively Modulates Tomato Root Development and Metabolism. Plants 2021, 10, 326. [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Carillo, P.; Ciriello, M.; Formisano, L.; El-Nakhel, C.; Ganugi, P.; Fiorini, A.; Miras Moreno, B.; Zhang, L.; Cardarelli, M.; et al. Copper Boosts the Biostimulant Activity of a Vegetal-Derived Protein Hydrolysate in Basil: Morpho-Physiological and Metabolomics Insights. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1235686. [CrossRef]

- Lucini, L.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Colla, G. Combining Molecular Weight Fractionation and Metabolomics to Elucidate the Bioactivity of Vegetal Protein Hydrolysates in Tomato Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 976. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.H.; Siahpoosh, M.R.; Roessner, U.; Udvardi, M.; Kopka, J. Plant Metabolomics Reveals Conserved and Divergent Metabolic Responses to Salinity. Physiologia Plantarum 2008, 132, 209–219. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Das, P.; Parida, A.K.; Agarwal, P.K. Proteomics, Metabolomics, and Ionomics Perspectives of Salinity Tolerance in Halophytes. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, N.; Lemée, G. La notion d’adaptation à la sécheresse. Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France. Actualités Botaniques 1984, 131, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Greenway, H.; Munns, R. Mechanisms of Salt Tolerance in Nonhalophytes. Annu. Rev. Plant. Physiol. 1980, 31, 149–190. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.C. Adaptation of Plants to Salinity. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier, 1997; Vol. 60, pp. 75–120 ISBN 978-0-12-000760-8.

- Munns, R. Comparative Physiology of Salt and Water Stress. Plant Cell & Environment 2002, 25, 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, K.N.; Lal, M.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Dev, D.; Kardile, H.B.; Patil, V.U.; Kumar, A.; Vanishree, G.; Kumar, D.; Bhardwaj, V.; et al. Salinity Stress in Potato: Understanding Physiological, Biochemical and Molecular Responses. Life 2021, 11, 545. [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P.; Grazia, M.; Pontecorvo, G.; Fuggi, A.; Woodrow, P. Salinity Stress and Salt Tolerance. In Abiotic Stress in Plants - Mechanisms and Adaptations; Shanker, A., Ed.; InTech, 2011 ISBN 978-953-307-394-1.

- Nouha, K.; Mkaddem Mounira, G.; Lamia, H.; Shahhat, I.; Mehrez, R.; Arbi, G. Physiological and Biochemical Responses in Mediterranean Saltbush (Atriplex Halimus L., Amaranthaceae Juss.) to Heavy Metal Pollution in Arid Environment. PAK. J. BOT. 2024, 56. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, N.; Perveen, S. Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) Priming Modulates Growth, Physiological and Biochemical Traits of Maize (Zea Mays L.) under Salt Stress. PAK. J. BOT. 2024, 56. [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, J.; Kmeli, N.; Bettaieb, I.; Bouktila, D. Genome-Wide Analysis of bZIP Family Genes Identifies Their Structural Diversity, Evolutionary Patterns and Expression Profiles in Response to Salt Stress in Sugar Beet. PAK. J. BOT. 2024, 56. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Unraveling Salt Stress Signaling in Plants. JIPB 2018, 60, 796–804. [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A Review on Plant Responses to Salt Stress and Their Mechanisms of Salt Resistance. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 132. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of Proline under Changing Environments: A Review. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [CrossRef]

- Farissi, M.; Aziz, F.; Bouizgaren, A.; Ghoulam, C. La symbiose Légumineuses-rhizobia sous conditions de salinité : Aspect Agro-physiologique et biochimique de la tolérance.

- Gururani, M.A.; Venkatesh, J.; Tran, L.S.P. Regulation of Photosynthesis during Abiotic Stress-Induced Photoinhibition. Molecular Plant 2015, 8, 1304–1320. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, Md.M.; Abdel-Farid, I.B.; Tran, L.-S.P. Extracts from Yeast and Carrot Roots Enhance Maize Performance under Seawater-Induced Salt Stress by Altering Physio-Biochemical Characteristics of Stressed Plants. J Plant Growth Regul 2019, 38, 966–979. [CrossRef]

- Reddy MP, V.A. Salinity Induced Changes in Pigment Composition and Chlorophyllase Activity of Wheat. Indian Journal of Plant Physiology, 1986, Vol. 29, 331–334 ref. 9.

- Sayyari, M.; Ghanbari, F.; Fatahi, S.; Bavandpour, F. Chilling Tolerance Improving of Watermelon Seedling by Salicylic Acid Seed and Foliar Application. Not Sci Biol 2013, 5, 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Srivastava, A.K.; Saber, H.; Alwaleed, E.A.; Tran, L.-S.P. Sargassum Muticum and Jania Rubens Regulate Amino Acid Metabolism to Improve Growth and Alleviate Salinity in Chickpea. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10537. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.M.-S.; Abdelgawad, Z.A.; El-Bassiouny, H.M.S. Alleviation of the Adverse Effects of Salinity Stress Using Trehalose in Two Rice Varieties. South African Journal of Botany 2016, 103, 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Srivastava, A.K.; El-sadek, M.S.A.; Kordrostami, M.; Tran, L.P. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Improve Growth and Enhance Tolerance of Broad Bean Plants under Saline Soil Conditions. Land Degrad Dev 2018, 29, 1065–1073. [CrossRef]

- Attia, M.S.; Osman, M.S.; Mohamed, A.S.; Mahgoub, H.A.; Garada, M.O.; Abdelmouty, E.S.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H. Impact of Foliar Application of Chitosan Dissolved in Different Organic Acids on Isozymes, Protein Patterns and Physio-Biochemical Characteristics of Tomato Grown under Salinity Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 388. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; This, D.; Pausch, R.C.; Vonhof, W.M.; Coburn, J.R.; Comstock, J.P.; McCouch, S.R. Leaf-Level Water Use Efficiency Determined by Carbon Isotope Discrimination in Rice Seedlings: Genetic Variation Associated with Population Structure and QTL Mapping. Theor Appl Genet 2009, 118, 1065–1081. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Abu Alhmad, M.F.; Kordrostami, M.; Abo–Baker, A.-B.A.-E.; Zakir, A. Inoculation with Azospirillum Lipoferum or Azotobacter Chroococcum Reinforces Maize Growth by Improving Physiological Activities Under Saline Conditions. J Plant Growth Regul 2020, 39, 1293–1306. [CrossRef]

- Tabassam, T.; Kanwal, S.; Saqlan Naqvi, S.M.; Ali, A.; Zaman, B.-; Akhtar, M.E. Effect of Manganese Application on PS-II Activity in Rice under Saline Conditions. IJAB 2016, 18, 837–843. [CrossRef]

- Viana, J.D.S.; Lopes, L.D.S.; Carvalho, H.H.D.; Cavalcante, F.L.P.; Oliveira, A.R.F.; Silva, S.J.D.; Oliveira, A.C.D.; Costa, R.S.D.; Mesquita, R.O.; Gomes-Filho, E. Differential Modulation of Metabolites Induced by Salt Stress in Rice Plants. South African Journal of Botany 2023, 162, 245–258. [CrossRef]

- Tomar, N.S.; Agarwal, R.M. Influence of Treatment of <I>Jatropha Curcas</I> L. Leachates and Potassium on Growth and Phytochemical Constituents of Wheat (<I>Triticum Aestivum</I> L.). AJPS 2013, 04, 1134–1150. [CrossRef]

- Tomar, N.S.; Sharma, M.; Agarwal, R.M. Phytochemical Analysis of Jatropha Curcas L. during Different Seasons and Developmental Stages and Seedling Growth of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L) as Affected by Extracts/Leachates of Jatropha Curcas L. Physiol Mol Biol Plants 2015, 21, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Abu Alhmad, M.F.; Abdelfattah, K.E. The Possible Roles of Priming with ZnO Nanoparticles in Mitigation of Salinity Stress in Lupine (Lupinus Termis) Plants. J Plant Growth Regul 2017, 36, 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Latef, A.A.A.; Alhmad, M.F.A.; Hammad, S.A. Foliar Application of Fresh Moringa Leaf Extract Overcomes Salt Stress in Fenugreek (Trigonellafoenum-Graecum) Plants. 2017.

- Farooq, M.; Nadeem, F.; Arfat, M.Y.; Nabeel, M.; Musadaq, S.; Cheema, S.A.; Nawaz, A. Exogenous Application of Allelopathic Water Extracts Helps Improving Tolerance against Terminal Heat and Drought Stresses in Bread Wheat ( Triticum Aestivum L. Em. Thell.). J Agronomy Crop Science 2018, 204, 298–312. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jabeur, M.; Chamekh, Z.; Jallouli, S.; Ayadi, S.; Serret, M.D.; Araus, J.L.; Trifa, Y.; Hamada, W. Comparative Effect of Seed Treatment with Thyme Essential Oil and Paraburkholderia Phytofirmans on Growth, Photosynthetic Capacity, Grain Yield, δ15 N and δ13 C of Durum Wheat under Drought and Heat Stress. Annals of Applied Biology 2022, 181, 58–69. [CrossRef]

- Ben Saad, R.; Ben Romdhane, W.; Wiszniewska, A.; Baazaoui, N.; Taieb Bouteraa, M.; Chouaibi, Y.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Kačániová, M.; Čmiková, N.; Ben Hsouna, A.; et al. Rosmarinus Officinalis L. Essential Oil Enhances Salt Stress Tolerance of Durum Wheat Seedlings through ROS Detoxification and Stimulation of Antioxidant Defense. Protoplasma 2024, 261, 1207–1220. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Genisheva, Z.; Botelho, C.; Santos, J.; Ramos, C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rocha, C.M.R. Unravelling the Biological Potential of Pinus Pinaster Bark Extracts. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 334. [CrossRef]

- Lárez-Velásquez, C. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Multiple Advantages for Creating Sustainable Development Poles. Polímeros 2023, 33, e20230005. [CrossRef]

- Malerba, M.; Cerana, R. Chitin- and Chitosan-Based Derivatives in Plant Protection against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses and in Recovery of Contaminated Soil and Water. Polysaccharides 2020, 1, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Peykani, L.S.; Sepehr, M.F. Effect of Chitosan on Antioxidant Enzyme Activity, Proline, and Malondialdehyde Content in Triticum Aestivum L. and Zea Maize L. under Salt Stress Condition.

- Turk, H. Chitosan-Induced Enhanced Expression and Activation of Alternative Oxidase Confer Tolerance to Salt Stress in Maize Seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 141, 415–422. [CrossRef]

- Faculty of Science and Technology, Nakhon Sawan Rajabhat University, Nakhon Sawan 60000, Thailand; Phothi, R.; Theerakarunwong, C.D.; Faculty of Science and Technology, Nakhon Sawan Rajabhat University, Nakhon Sawan 60000, Thailand Effect of Chitosan on Physiology, Photosynthesis and Biomass of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) under Elevated Ozone. Aust J Crop Sci 2017, 11, 624–630. [CrossRef]

- Vidhyasekaran, P. Switching on Plant Innate Immunity Signaling Systems; Signaling and Communication in Plants; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-26116-4.

- Davison, P.A.; Hunter, C.N.; Horton, P. Overexpression of β-Carotene Hydroxylase Enhances Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Nature 2002, 418, 203–206. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Mishra, S.N. Putrescine Alleviation of Growth in Salt Stressed Brassica Juncea by Inducing Antioxidative Defense System. Journal of Plant Physiology 2005, 162, 669–677. [CrossRef]

- Gomathi, R.; Rakkiyapan, P. Comparative Lipid Peroxidation, Leaf Membrane Thermostability, and Antioxidant System in Four Sugarcane Genotypes Differing in Salt Tolerance.

- Yildiz, M.; Terzi, H. Small Heat Shock Protein Responses in Leaf Tissues of Wheat Cultivars with Different Heat Susceptibility. Biologia 2008, 63, 521–525. [CrossRef]

- Merlene Ann Babu, D.S. and K.M.G. Effect of Salt Stress on Expression of Carotenoid Pathway Genes in Tomato. Journal of Stress Physiology & Biochemistry, 2011, 7, 87–94.

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A Multifunctional Amino Acid. Trends in Plant Science 2010, 15, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Kordrostami, M.; Rabiei, B.; Kumleh, H.H. Different Physiobiochemical and Transcriptomic Reactions of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Cultivars Differing in Terms of Salt Sensitivity under Salinity Stress. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 7184–7196. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Ortega, C.O.; Ochoa-Alfaro, A.E.; Reyes-Agüero, J.A.; Aguado-Santacruz, G.A.; Jiménez-Bremont, J.F. Salt Stress Increases the Expression of P5cs Gene and Induces Proline Accumulation in Cactus Pear. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2008, 46, 82–92. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Chen, T.; Pen, J.; Yu, S.; Zhao, X. Morphological and Physiological Responses of Cotton (Gossypium Hirsutum L.) Plants to Salinity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112807. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.G. Alleviation of Salinity Stress on Vicia Faba L. Plants via Seed Priming with Melatonin. Acta biol. Colomb. 2014, 20. [CrossRef]

- Selem, E. Physiological Effects of Spirulina Platensis in Salt Stressed Vicia Faba L. Plants. Egypt. J. Bot. 2018, 0, 0–0. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Chen, Q.; Bu, N. Alleviation of Exogenous Oligochitosan on Wheat Seedlings Growth under Salt Stress. Protoplasma 2012, 249, 393–399. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Ahmad, R. The Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Response to Salt Stress in Safflower ( Carthamus Tinctorius L.) and Sunflower ( Helianthus Annuus L.) Seedlings Raised from Seed Treated with Chitosan. J Sci Food Agric 2013, 93, 1699–1705. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Nat Rev Genet 2022, 23, 104–119. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, F.; Galani, S.; Wickramasinghe, K.P.; Zhao, P.; Lu, X.; Lin, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Current Perspectives on the Regulatory Mechanisms of Sucrose Accumulation in Sugarcane. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27277. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M. Effects of Water Deficits on Carbon Assimilation. J Exp Bot 1991, 42, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Baki, G.K.A.; Siefritz, F.; Man, H. -M.; Weiner, H.; Kaldenhoff, R.; Kaiser, W.M. Nitrate Reductase in Zea Mays L. under Salinity. Plant Cell & Environment 2000, 23, 515–521. [CrossRef]

- Mustapha Ait Haddou Mouloud; Bousrhal, A.; Benyahia, H.; Benazzoouz, A. Effet Du Stress Salin Sur l’accumulation de La Proline et Des Sucres Solubles Dans Les Feuilles de Trois Porte-Greffes d’agrumes Au Maroc. Fruits 2002, 57, 335–340. [CrossRef]

- Nemati, I.; Moradi, F.; Gholizadeh, S.; Esmaeili, M.A.; Bihamta, M.R. The Effect of Salinity Stress on Ions and Soluble Sugars Distribution in Leaves, Leaf Sheaths and Roots of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Seedlings. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 57, 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Chamnanmanoontham, N.; Pongprayoon, W.; Pichayangkura, R.; Roytrakul, S.; Chadchawan, S. Chitosan Enhances Rice Seedling Growth via Gene Expression Network between Nucleus and Chloroplast. Plant Growth Regul 2015, 75, 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Rabêlo, V.M.; Magalhães, P.C.; Bressanin, L.A.; Carvalho, D.T.; Reis, C.O.D.; Karam, D.; Doriguetto, A.C.; Santos, M.H.D.; Santos Filho, P.R.D.S.; Souza, T.C.D. The Foliar Application of a Mixture of Semisynthetic Chitosan Derivatives Induces Tolerance to Water Deficit in Maize, Improving the Antioxidant System and Increasing Photosynthesis and Grain Yield. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8164. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Choudhary, K.K.; Chaudhary, N.; Gupta, S.; Sahu, M.; Tejaswini, B.; Sarkar, S. Salt Stress Resilience in Plants Mediated through Osmolyte Accumulation and Its Crosstalk Mechanism with Phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1006617. [CrossRef]

- Soshinkova, T.N.; Radyukina, N.L.; Korolkova, D.V.; Nosov, A.V. Proline and Functioning of the Antioxidant System in Thellungiella Salsuginea Plants and Cultured Cells Subjected to Oxidative Stress. Russ J Plant Physiol 2013, 60, 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Azooz, M.M.; Metwally, A.; Abou-Elhamd, M.F. Jasmonate-Induced Tolerance of Hassawi Okra Seedlings to Salinity in Brackish Water. Acta Physiol Plant 2015, 37, 77. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. Relative Importance of Photosynthetic Physiology and Biomass Allocation for Tree Seedling Growth across a Broad Light Gradient. Tree Physiology 2004, 24, 155–167. [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; Haider, S.T.A.; Hussain, M.B.; Ehsan, A.; Datta, R.; Alahmadi, T.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Alharbi, S.A. Potential of Kaempferol and Caffeic Acid to Mitigate Salinity Stress and Improving Potato Growth. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 21657. [CrossRef]

- . F.N.; . R.A.K.-N.; . F.R.; . M.S. Growth and Some Physiological Attributes of Pea (Pisum Sativum L.) As Affected by Salinity. Pakistan J. of Biological Sciences 2007, 10, 2752–2755. [CrossRef]

- Assaha, D.V.M.; Ueda, A.; Saneoka, H.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Yaish, M.W. The Role of Na+ and K+ Transporters in Salt Stress Adaptation in Glycophytes. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 509. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.-H.; Gao, J.-P.; Li, L.-G.; Cai, X.-L.; Huang, W.; Chao, D.-Y.; Zhu, M.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Luan, S.; Lin, H.-X. A Rice Quantitative Trait Locus for Salt Tolerance Encodes a Sodium Transporter. Nat Genet 2005, 37, 1141–1146. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Regulation of Ion Homeostasis under Salt Stress. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2003, 6, 441–445. [CrossRef]

- Horie, T.; Yoshida, K.; Nakayama, H.; Yamada, K.; Oiki, S.; Shinmyo, A. Two Types of HKT Transporters with Different Properties of Na+ and K+ Transport in Oryza Sativa. The Plant Journal 2001, 27, 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Grieve, C.; Grattan, S. Mineral Nutrient Acquisition and Response by Plants Grown in Saline Environments. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, Second Edition; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; Books in Soils, Plants, and the Environment; CRC Press, 1999; Vol. 19990540, pp. 203–229 ISBN 978-0-8247-1948-7.

- Radi, A.A.; Farghaly, F.A.; Hamada, A.M. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Salt-Tolerant and Salt-Sensitive Wheat and Bean Cultivars to Salinity. 2013, 3, 72–88.

- Castillo, J.M.; Mancilla-Leytón, J.M.; Martins-Noguerol, R.; Moreira, X.; Moreno-Pérez, A.J.; Muñoz-Vallés, S.; Pedroche, J.J.; Figueroa, M.E.; García-González, A.; Salas, J.J.; et al. Interactive Effects between Salinity and Nutrient Deficiency on Biomass Production and Bio-Active Compounds Accumulation in the Halophyte Crithmum Maritimum. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 301, 111136. [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Riadh, K.; Gopi, R.; Manivannan, P.; Inès, J.; Al-Juburi, H.J.; Chang-Xing, Z.; Hong-Bo, S.; Panneerselvam, R. Antioxidant Defense Responses: Physiological Plasticity in Higher Plants under Abiotic Constraints. Acta Physiol Plant 2009, 31, 427–436. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Genetic Analysis of Plant Salt Tolerance Using Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2000, 124, 941–948. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, A.-M.F.M.; Mohamed, E.; Kasem, A.M.M.A.; El-Ghamery, A.A. Differential Salt Tolerance Strategies in Three Halophytes from the Same Ecological Habitat: Augmentation of Antioxidant Enzymes and Compounds. Plants 2021, 10, 1100. [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. ASCORBATE AND GLUTATHIONE: Keeping Active Oxygen Under Control. Annu. Rev. Plant. Physiol. Plant. Mol. Biol. 1998, 49, 249–279. [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Biricolti, S.; Guidi, L.; Ferrini, F.; Fini, A.; Tattini, M. The Biosynthesis of Flavonoids Is Enhanced Similarly by UV Radiation and Root Zone Salinity in L. Vulgare Leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology 2011, 168, 204–212. [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Azzarello, E.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Flavonoids as Antioxidants in Plants: Location and Functional Significance. Plant Science 2012, 196, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Górniak, I.; Bartoszewski, R.; Króliczewski, J. Comprehensive Review of Antimicrobial Activities of Plant Flavonoids. Phytochem Rev 2019, 18, 241–272. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y. Analysis of Flavonoid Metabolites in Citrus Peels (Citrus Reticulata “Dahongpao”) Using UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Molecules 2019, 24, 2680. [CrossRef]

- Felice, M.R.; Maugeri, A.; De Sarro, G.; Navarra, M.; Barreca, D. Molecular Pathways Involved in the Anti-Cancer Activity of Flavonols: A Focus on Myricetin and Kaempferol. IJMS 2022, 23, 4411. [CrossRef]

- Pei, K.; Ou, J.; Huang, J.; Ou, S. P -Coumaric Acid and Its Conjugates: Dietary Sources, Pharmacokinetic Properties and Biological Activities. J Sci Food Agric 2016, 96, 2952–2962. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Tiika, R.J.; Tian, F.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Cui, G.; Yang, H. Metabolomics Analysis Unveils Important Changes Involved in the Salt Tolerance of Salicornia Europaea. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1097076. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Li, C.; Guo, M.; Liu, J.; Qu, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ge, Y. Caffeic Acid Enhances Storage Ability of Apple Fruit by Regulating Fatty Acid Metabolism. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2022, 192, 112012. [CrossRef]

- Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Nawaz, M.S.; Asghar, H.; Waqas, M.; Mahmood, F. Caffeic Acid Helps to Mitigate Adverse Effects of Soil Salinity and Other Abiotic Stresses in Legumes.

- Huang, R.; Li, C.; Guo, M.; Xu, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Ge, Y. Caffeic Acid Regulated Respiration, Ethylene and Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism to Suppress Senescence of Malus Domestica. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2022, 194, 112074. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, H.; Abbasi, G.H.; Jamil, M.; Malik, Z.; Ali, M.; Iqbal, R. Assessing the Potential of Exogenous Caffeic Acid Application in Boosting Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) Crop Productivity under Salt Stress. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259222. [CrossRef]

- Shim, I.-S.; Momose, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Kim, D.-W.; Usui, K. Inhibition of Catalase Activity by Oxidative Stress and Its Relationship to Salicylic Acid Accumulation in Plants. Plant Growth Regulation 2003, 39, 285–292. [CrossRef]

- Senaratna, T.; Touchell, D.; Bunn, E.; Dixon, K. Acetyl Salicylic Acid (Aspirin) and Salicylic Acid Induce Multiple Stress Tolerance in Bean and Tomato Plants. Plant Growth Regulation 2000, 30, 157–161. [CrossRef]

- Németh, M.; Janda, T.; Horváth, E.; Páldi, E.; Szalai, G. Exogenous Salicylic Acid Increases Polyamine Content but May Decrease Drought Tolerance in Maize. Plant Science 2002, 162, 569–574. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Usha, K. Salicylic Acid Induced Physiological and Biochemical Changes in Wheat Seedlings under Water Stress. Plant Growth Regulation 2003, 39, 137–141. [CrossRef]

- Borsani, O.; Valpuesta, V.; Botella, M.A. Evidence for a Role of Salicylic Acid in the Oxidative Damage Generated by NaCl and Osmotic Stress in Arabidopsis Seedlings. Plant Physiology 2001, 126, 1024–1030. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Qian, R. Salicylic Acid Alleviates the Adverse Effects of Salt Stress on Dianthus Superbus (Caryophyllaceae) by Activating Photosynthesis, Protecting Morphological Structure, and Enhancing the Antioxidant System. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 600. [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, H.; Wasti, S.; Manaa, A.; Gharbi, E.; Chalh, A.; Vandoorne, B.; Lutts, S.; Ahmed, H.B. Does Salicylic Acid (SA) Improve Tolerance to Salt Stress in Plants? A Study of SA Effects On Tomato Plant Growth, Water Dynamics, Photosynthesis, and Biochemical Parameters. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 2016, 20, 180–190. [CrossRef]

- Fariduddin, Q.; Hayat, S.; Ahmad, A. Salicylic Acid Influences Net Photosynthetic Rate, Carboxylation Efficiency, Nitrate Reductase Activity, and Seed Yield in Brassica Juncea. Photosynt. 2003, 41, 281–284. [CrossRef]

- Linić, I.; Mlinarić, S.; Brkljačić, L.; Pavlović, I.; Smolko, A.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Ferulic Acid and Salicylic Acid Foliar Treatments Reduce Short-Term Salt Stress in Chinese Cabbage by Increasing Phenolic Compounds Accumulation and Photosynthetic Performance. Plants 2021, 10, 2346. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ren, T.; Du, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C. Salt Stress Decreases Seedling Growth and Development but Increases Quercetin and Kaempferol Content in Apocynum Venetum. Plant Biol J 2020, 22, 813–821. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, B.; Anwar, F.; Ashraf, M. Effect of Extraction Solvent/Technique on the Antioxidant Activity of Selected Medicinal Plant Extracts. Molecules 2009, 14, 2167–2180. [CrossRef]

- Alhaithloul, H.A.S.; Alqahtani, M.M.; Abdein, M.A.; Ahmed, M.A.I.; Hesham, A.E.-L.; Aljameeli, M.M.E.; Al Mozini, R.N.; Gharsan, F.N.; Hussien, S.M.; El-Amier, Y.A. Rosemary and Neem Methanolic Extract: Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, and Larvicidal Activities Supported by Chemical Composition and Molecular Docking Simulations. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1155698. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, L.-M.; Liu, G.-M.; Liu, Y.-J.; Zheng, C.-B.; Lv, Y.-J.; Li, H.-Z.; Zheng, Y.-T. Potent Anti-HIV Activities and Mechanisms of Action of a Pine Cone Extract from Pinus Yunnanensis. Molecules 2012, 17, 6916–6929. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ran, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J.; Yi, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.-K.; et al. Functional Analysis of CqPORB in the Regulation of Chlorophyll Biosynthesis in Chenopodium Quinoa. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1083438. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, K.; Huang, C.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Si, X.; Li, Y. Global Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Regulation Mechanism of Pigment and Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism During the Stigma Development of Carya Cathayensis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 881394. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Saeed Almehrzi, A.S.; Nasir Alnajjar, A.J.; Alam, P.; Elsayed, N.; Khalil, R.; Hayat, S. Glucose Modulates Copper Induced Changes in Photosynthesis, Ion Uptake, Antioxidants and Proline in Cucumis Sativus Plants. Carbohydrate Research 2021, 501, 108271. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, C.; He, L.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Gao, J. Identification of Key Genes Controlling Soluble Sugar and Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage by Integrating Metabolome and Genome-Wide Transcriptome Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1043489. [CrossRef]

- Jackson,M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis; Advanced Course.; Jackson, M.L. (1973) Soil Chemical Analysis. Advanced Course Ed. 2. A Manual of Methods Useful for Instruction and Research in Soil Chemistry, Physical Chemistry of Soils, Soil Fertility and Genesis ., 1073;

- Schofield, R.K.; Taylor, A.W. The Measurement of Soil pH. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1955, 19, 164–167. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, W.L.; Norvell, W.A. Development of a DTPA Soil Test for Zinc, Iron, Manganese, and Copper. Soil Science Soc of Amer J 1978, 42, 421–428. [CrossRef]

| Soil elements | CBSS | TRPP | TRRO | TRSC | |

| PH | 7.77 | 7.78 | 7.96 | 7.67 | |

| CE (dS/m) | 1.672 | 1.267 | 0.517 | 1.398 | |

| P2O5 (ppm) | 125.95 | 217.55 | 68.7 | 171.75 | |

| K2O (mg/100g) | 9.03 | 11.44 | 8.43 | 7.83 | |

| Fe (mg/l) | 2 | 3.4 | 12.7 | 3.6 | |

| K (mg/l) | 7.33 | 38.81 | 12.17 | 11.34 | |

| Na (mg/l) | 94.05 | 15.12 | 53.14 | 69.09 | |

| Mg (mg/l) | 34.12 | 20.20 | 34.29 | 36.95 | |

| Ca (mg/l) | 461.7 | 630.1 | 469.3 | 471.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).