Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Dual Attention (DA) Mechanisms in U-Net Framework: The proposed TS-MSDA U-Net model integrates a hierarchical encoder-decoder structure for multiscale temporal feature extraction with DA mechanisms, comprising both sequence attention (SA) and channel attention (CA), effectively capturing complex temporal dynamics in multivariate time-series data.

- Enhanced TSS for EVs: The model achieves mean absolute errors (MAEs) within ±1% across key EV parameters (battery SOC, voltage, acceleration, torque) using an open-source dataset from 70 real-world trips, demonstrating a two-fold improvement over baseline TS-p2pGAN model with enhanced alignment to original data distributions.

- High-Resolution Signal Reconstruction: The TS-MSDA U-Net achieves a 36 × enhancement in signal resolution from low-speed ADC data of a resonant CLLC half-bridge converter, successfully capturing complex nonlinear mappings where thebasic U-Net models failed.

- Cross-Domain Validation and Attention Mechanism Analysis: The model is validated across two distinct engineering domains: automotive and power electronics, demonstrating robustness and generalizability. While the DA mechanism offers performance gains, analysis reveals its marginal contribution over the basic U-Net in certain cases, providing insights for architectural refinements.

2. Methodology

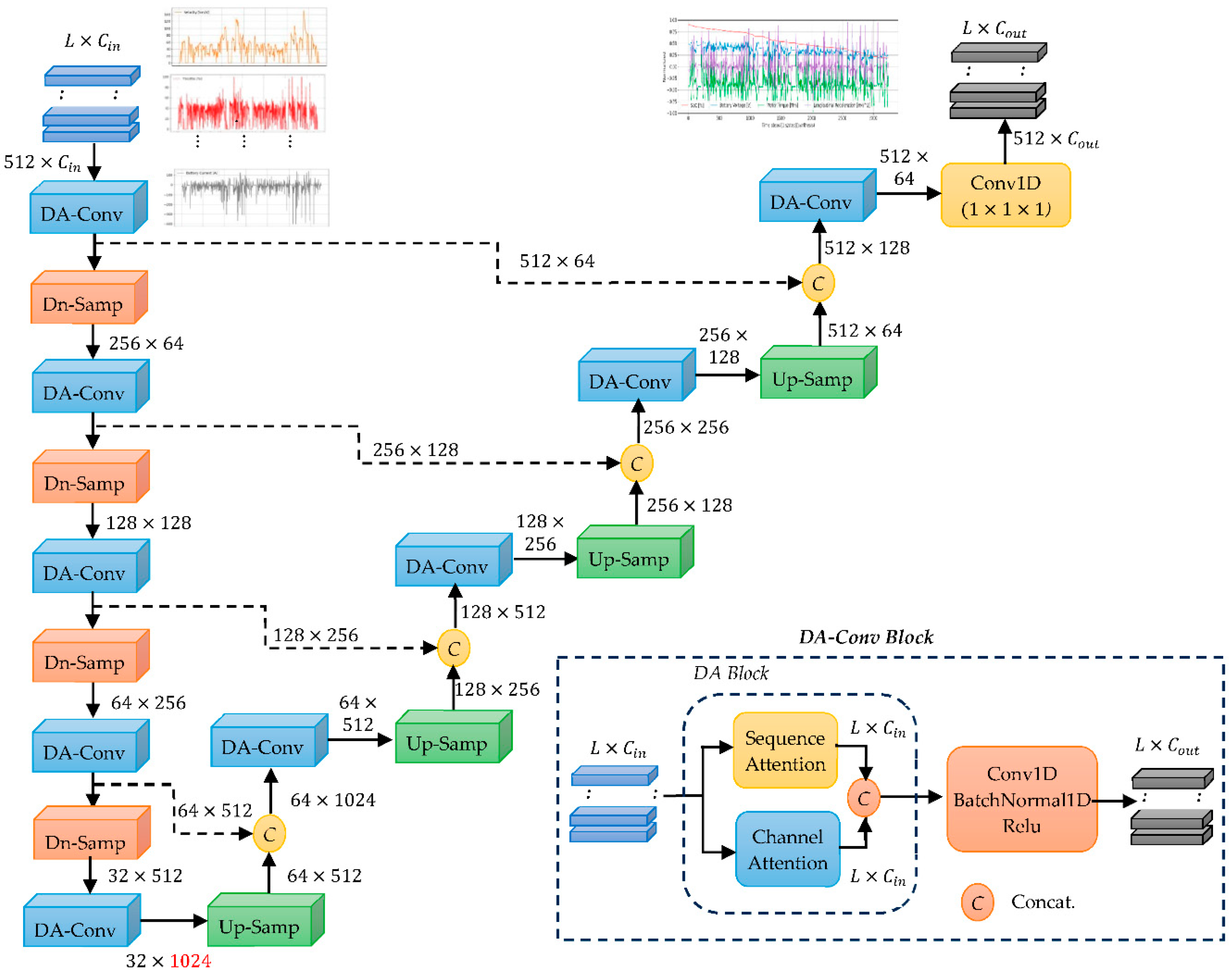

2.1. Hierarchical Encoder–Decoder Network

2.2. Dual-Attention Block

2.2.1. Positional Embedding

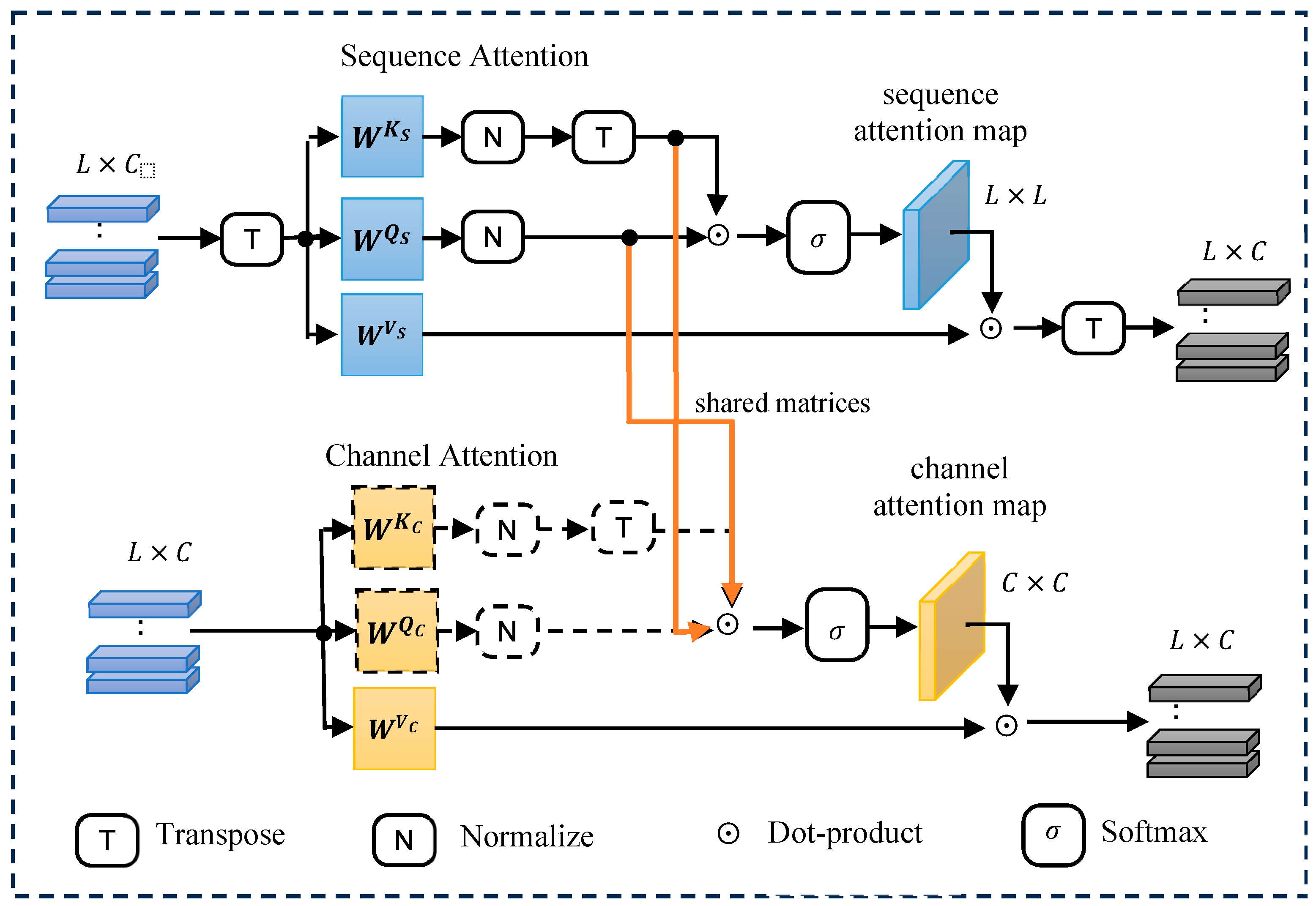

2.2.2. Sequence Attention Module

2.2.3. Channel Attention Module

3. Experimental Setup and Results

3.1. Vehcile Trip Dataset

3.1.1. Baseline Comparison

| Trip No |

U-Net | U-Net with SA | TS-MSDA-UNet | UNETR | UNETR++ | TS-p2pGAN | ||||||||||||

|

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

|

| 1 | 0.96 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 1.05 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 1.96 | 0.97 | 1.19 |

| 2 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 1.10 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 2.02 | 1.01 | 1.12 |

| 3 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 1.17 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 1.91 | 1.02 | 1.21 |

| 4 | 1.07 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 1.21 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 1.40 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 1.79 | 0.77 | 0.84 |

| 5 | 1.34 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 1.43 | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0.92 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 1.72 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 1.91 | 0.92 | 1.09 |

| 6 | 0.81 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 1.01 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 1.11 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 1.62 | 0.84 | 1.03 |

| 7 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 1.56 | 0.84 | 1.01 |

| 8 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.81 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.93 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 1.51 | 0.78 | 0.92 |

| 9 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 1.73 | 0.85 | 0.95 |

| 10 | 1.02 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 1.19 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 1.40 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 2.03 | 1.06 | 1.26 |

| 11 | 1.14 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 1.14 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.81 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 1.69 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 2.08 | 1.01 | 1.15 |

| 12 | 0.72 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.78 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 1.26 | 0.66 | 0.72 |

| 13 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 2.69 | 1.46 | 1.56 |

| 14 | 1.28 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 1.36 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 1.19 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 1.54 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 1.08 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 1.48 | 0.80 | 0.91 |

| 15 | 0.90 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 1.15 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 1.31 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 1.83 | 0.96 | 1.17 |

| 16 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.82 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 1.04 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 1.92 | 1.02 | 1.21 |

| 17 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 1.06 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 2.11 | 1.07 | 1.28 |

| 18 | 1.16 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 1.26 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 1.50 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 1.66 | 0.87 | 1.01 |

| 19 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 1.24 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 1.80 | 0.92 | 1.09 |

| 20 | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 1.25 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 1.91 | 0.96 | 1.11 |

| 21 | 0.97 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 1.20 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 1.51 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 1.56 | 0.80 | 0.97 |

| 22 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 1.15 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 1.25 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 2.05 | 0.97 | 1.20 |

| 23 | 1.07 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 1.37 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 1.76 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 1.09 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 2.65 | 1.31 | 1.52 |

| 24 | 1.46 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 1.98 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 2.34 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 2.36 | 1.25 | 1.42 |

| 25 | 0.78 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 1.03 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 2.23 | 1.09 | 1.26 |

| 26 | 1.53 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 1.56 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 1.09 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 2.55 | 0.90 | 1.07 | 1.22 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 2.75 | 1.30 | 1.51 |

| 27 | 1.22 | 0.59 | 0.70 | 1.47 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 1.68 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 2.04 | 1.11 | 1.30 |

| 28 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 1.30 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 2.21 | 1.23 | 1.40 |

| 29 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 1.04 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 1.20 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 2.90 | 1.67 | 1.77 |

| 30 | 1.54 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 1.89 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 1.85 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 2.25 | 1.02 | 1.22 |

| 31 | 1.15 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 1.29 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 1.54 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 1.86 | 0.87 | 1.06 |

| 32 | 1.15 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 1.49 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 1.90 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 2.70 | 1.30 | 1.52 |

| 33 | 1.89 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 2.34 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 1.52 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 1.17 | 1.47 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 2.45 | 1.24 | 1.60 |

| 34 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 2.32 | 1.12 | 1.32 |

| 35 | 1.02 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 1.15 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 1.46 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 1.95 | 0.93 | 1.08 |

| 36 | 0.90 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 1.08 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 1.26 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 1.75 | 0.86 | 1.00 |

| 37 | 1.19 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 1.44 | 0.60 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 1.84 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 1.89 | 0.93 | 1.13 |

| 38 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 1.14 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 1.52 | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 2.30 | 1.13 | 1.36 |

| 39 | 1.04 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 1.21 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 1.28 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 2.17 | 1.18 | 1.40 |

| 40 | 1.36 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 1.78 | 1.10 | 1.35 | 1.05 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 2.22 | 1.40 | 1.66 | 0.97 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 2.45 | 1.33 | 1.67 |

| 41 | 2.42 | 1.26 | 1.41 | 4.71 | 2.10 | 2.34 | 2.81 | 1.42 | 1.52 | 5.57 | 2.94 | 3.34 | 2.45 | 1.03 | 1.17 | 2.40 | 1.19 | 1.48 |

| 42 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 2.71 | 1.26 | 1.40 |

| 43 | 0.87 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 1.40 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 2.33 | 1.22 | 1.48 |

| 44 | 0.81 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 1.01 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 1.19 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 1.47 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| 45 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 1.58 | 0.79 | 0.93 |

| 46 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 1.13 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 1.13 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 2.41 | 1.20 | 1.39 |

| 47 | 1.06 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 1.58 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 1.78 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 2.28 | 1.08 | 1.30 |

| 48 | 1.21 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 1.40 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 1.57 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 1.05 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 1.72 | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| 49 | 0.76 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.93 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 2.58 | 1.24 | 1.45 |

| 50 | 1.14 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 1.65 | 0.63 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 2.14 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 3.29 | 1.46 | 1.75 |

| 51 | 1.24 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 1.60 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 2.47 | 0.79 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 0.52 | 0.68 | 2.19 | 1.15 | 1.39 |

| 52 | 1.13 | 0.55 | 0.68 | 1.37 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 1.52 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 2.21 | 1.09 | 1.30 |

| 53 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 1.04 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 1.58 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| 54 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 1.39 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 1.45 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| 55 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 2.31 | 1.14 | 1.27 |

| 56 | 1.01 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 1.32 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 1.41 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 1.48 | 0.84 | 0.99 |

| 57 | 0.99 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 1.22 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 1.45 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 2.54 | 1.24 | 1.45 |

| 58 | 0.88 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 1.55 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 1.91 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 1.75 | 0.94 | 1.15 |

| 59 | 0.81 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 1.02 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 1.55 | 0.79 | 0.97 |

| 60 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 1.24 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 1.54 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 1.14 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 2.05 | 1.00 | 1.19 |

| 61 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 1.21 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 1.57 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 2.05 | 1.03 | 1.27 |

| 62 | 1.72 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.84 | 1.09 | 1.24 | 1.84 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 1.80 | 0.95 | 1.12 | 1.45 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 2.78 | 1.27 | 1.43 |

| 63 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.55 | 1.87 | 0.99 | 1.21 |

| 64 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 1.15 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 2.04 | 1.06 | 1.35 |

| 65 | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 1.05 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 1.38 | 0.62 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 2.52 | 1.16 | 1.45 |

| 66 | 1.28 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 1.44 | 0.66 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 1.79 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.44 | 0.58 | 1.63 | 0.87 | 1.09 |

| 67 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 1.49 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 2.74 | 1.37 | 1.69 |

| 68 | 1.13 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 1.40 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 1.69 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 2.16 | 1.10 | 1.35 |

| 69 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 1.09 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 1.88 | 0.96 | 1.22 |

| 70 | 1.07 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 1.25 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 2.02 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 2.37 | 1.13 | 1.34 |

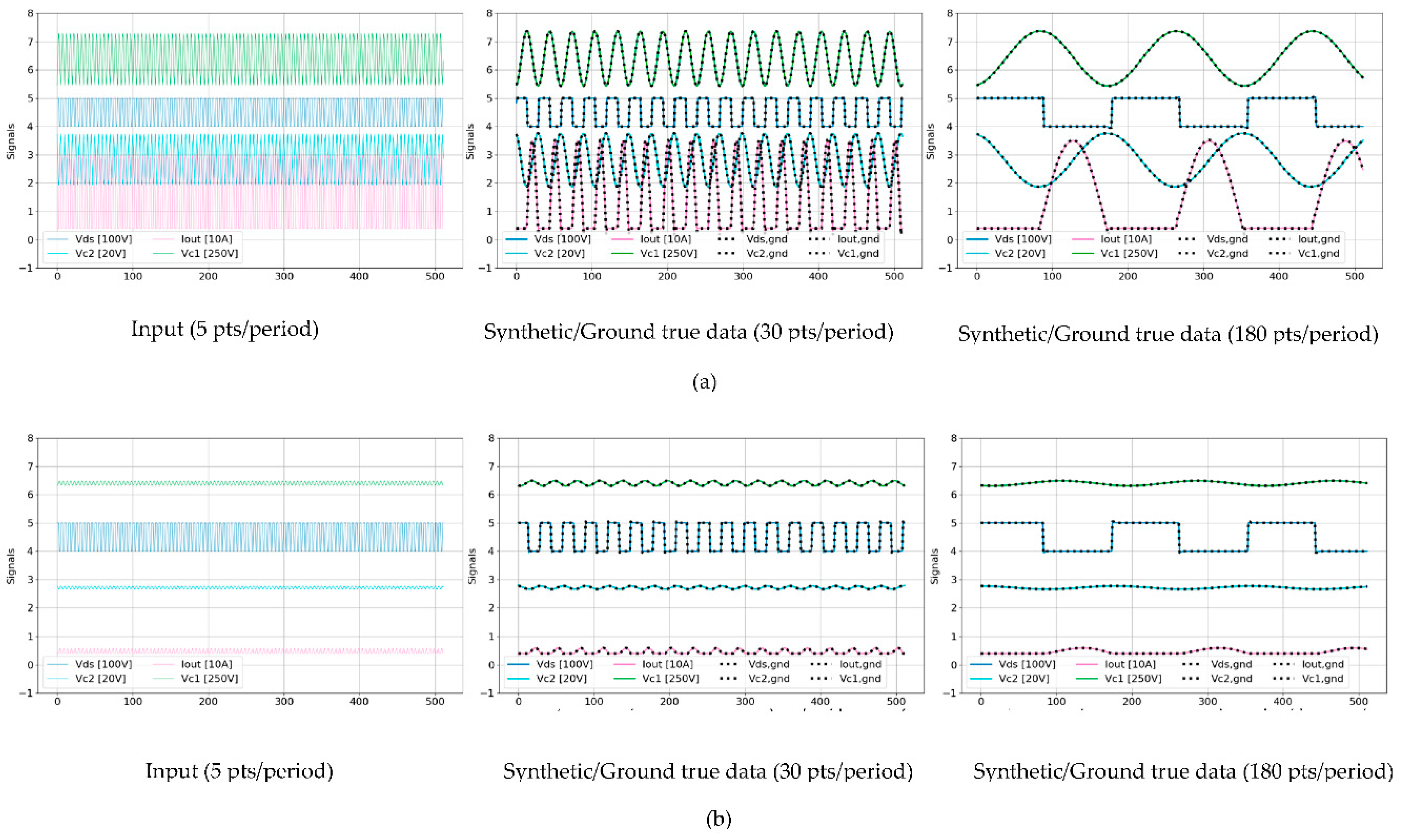

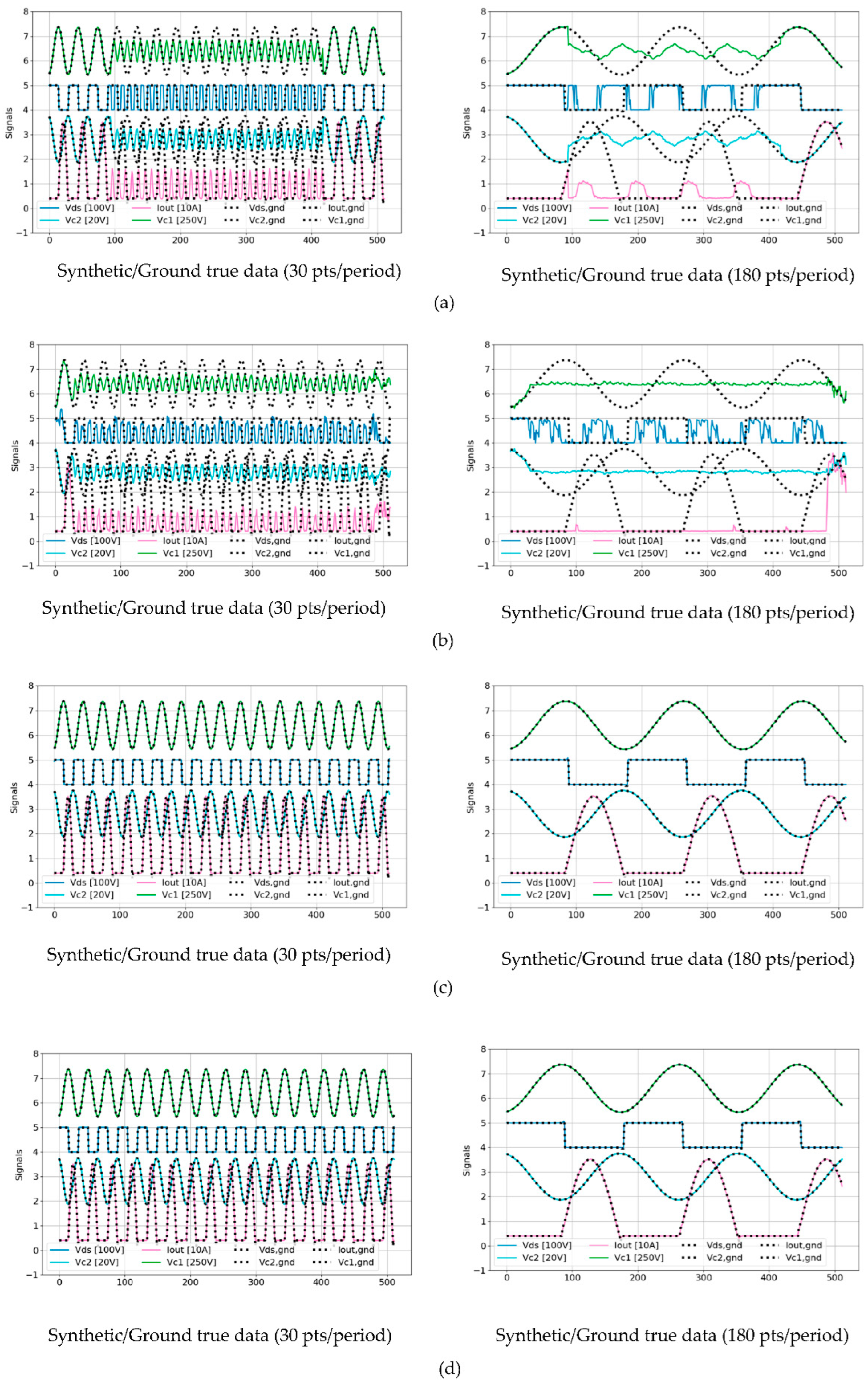

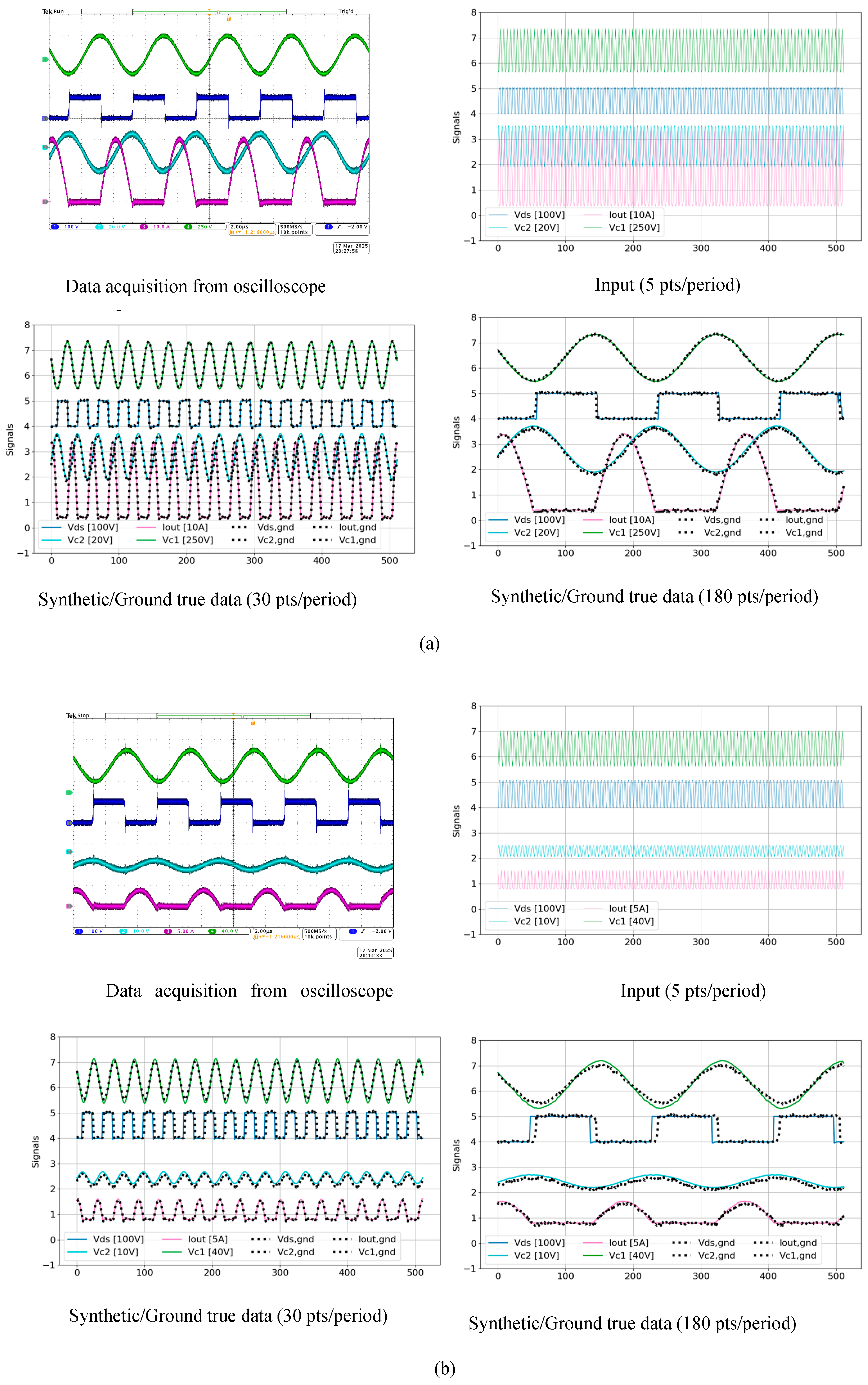

3.2. Reconstruction of Periodic Signals for Resonant CLLC Half-bridge Converters

3.2.1. Generation of Training Time-Series Data Using the PLECS Simulator

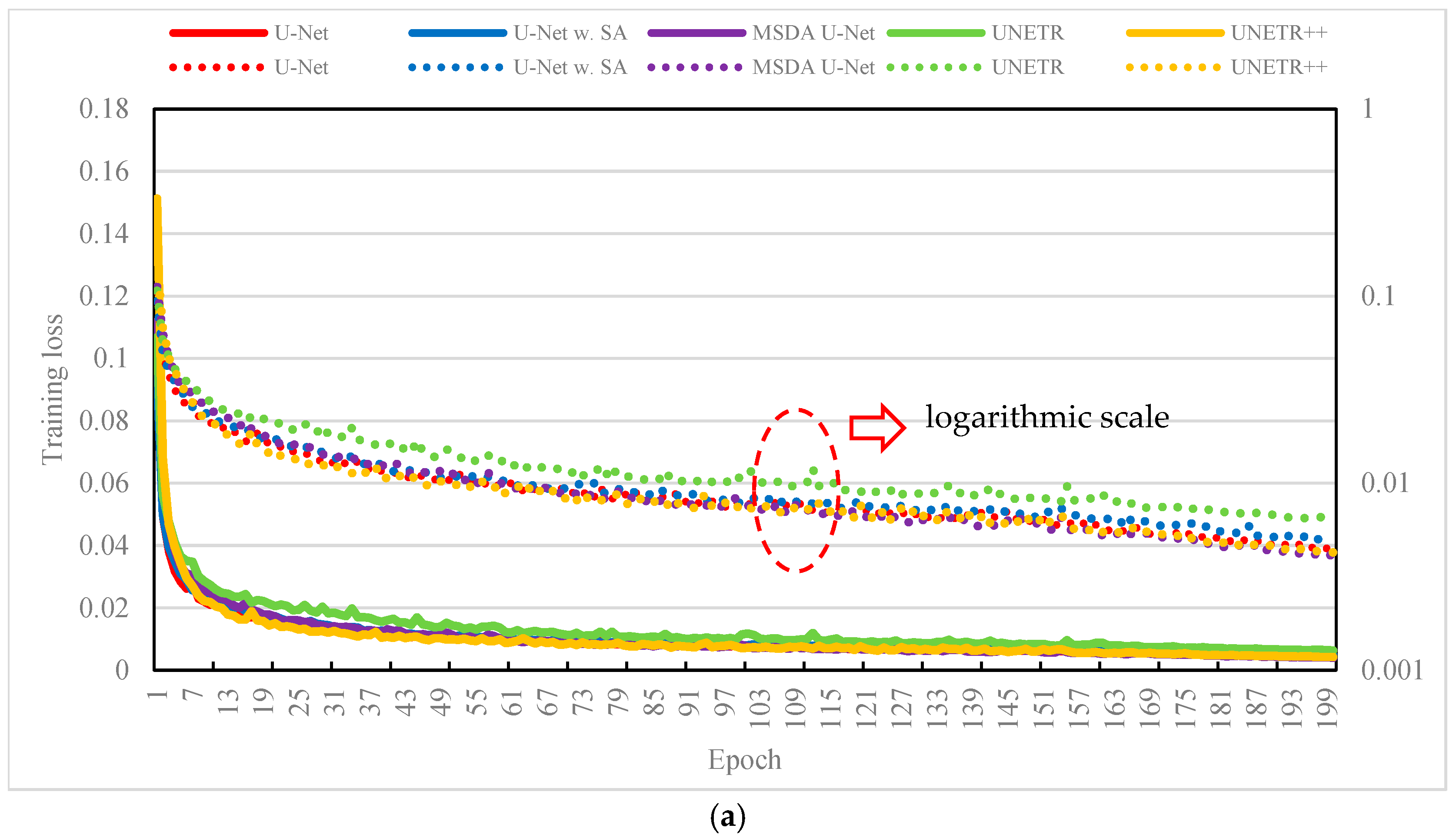

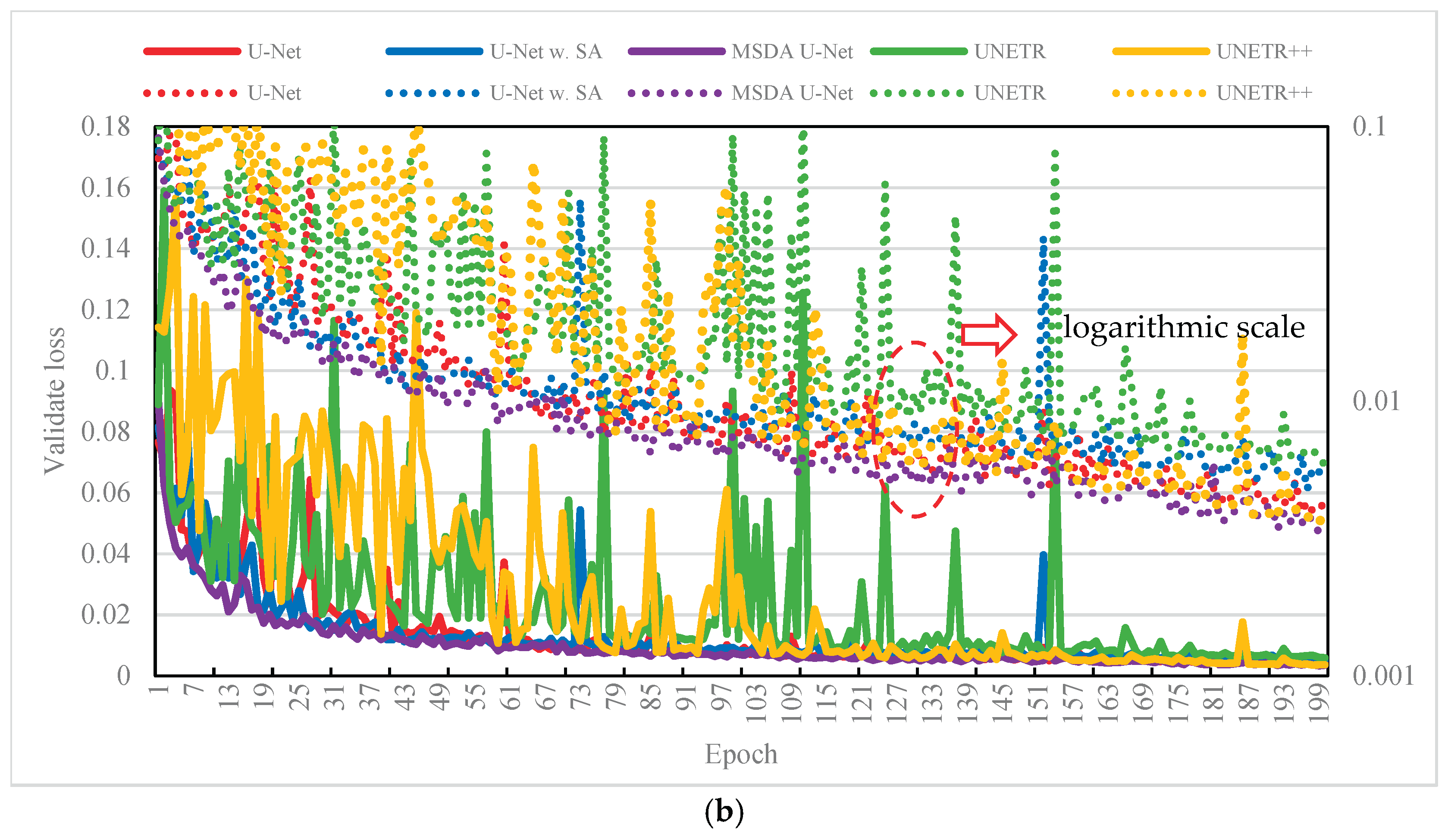

3.2.2. Analysis of Training Experimental Results.

3.2.3. Testing Experimental Results Using the Prototype Converters

4. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iglesias, G.; Talavera, E.; González-Prieto, Á.; Mozo, A.; Gómez-Canaval, S. Data Augmentation Techniques in Time Series Domain: A Survey and Taxonomy. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 10123–10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, A.; Ramezani, S.B.; Cummins, L.; Mittal, S.; Rahimi, S.; Seale, M.; Jaboure, J. Generating Synthetic Time Series Data for Cyber-Physical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Boston, MA, USA, 1–7 November 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, E.; Wang, Z.; She, Q.; Ward, T. Generative Adversarial Networks in Time Series: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Mou, P. Time Series Data Augmentation for Energy Consumption Data Based on Improved TimeGAN. Sensors 2025, 25, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Peng, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, S.; Metaxas, D.N. CR-GAN: Learning Complete Representations for Multi-View Generation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.11191. [Google Scholar]

- El Fallah, S.; Kharbach, J.; Hammouch, Z.; Rezzouk, A.; Jamil, M.O. State of Charge Estimation of an Electric Vehicle’s Battery Using Deep Neural Networks: Simulation and Experimental Results. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, S.L. Generative Adversarial Network for Synthesizing Multivariate Time-Series Data in Electric Vehicle Driving Scenarios. Sensors 2025, 25, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotem, Y.; Shimoni, N.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Transfer Learning for Time Series Classification Using Synthetic Data Generation. In International Symposium on Cyber Security, Cryptology, and Machine Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 232–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, X.; Pang, Y.; Han, J.; Pan, J. Cascaded Hierarchical Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling Module for Semantic Segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 110, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W., Frangi, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9351. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, N.; Paheding, S.; Elkin, C.P.; Devabhaktuni, V. U-Net and Its Variants for Medical Image Segmentation: A Review of Theory and Applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82031–82057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R.; Aghdam, E.K.; Rauland, A.; Jia, Y.; Avval, A.H.; Bozorgpour, A.; Merhof, D. Medical Image Segmentation Review: The Success of U-Net. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Qin, J.; Sun, D.; Liao, Y.; Zheng, J. Pfformer: A Time-Series Forecasting Model for Short-Term Precipitation Forecasting. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xie, C.; Fei, Y.; Tao, H. Attention Mechanisms in CNN-Based Single Image Super-Resolution: A Brief Review and a New Perspective. Electronics 2021, 10, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.; Chang, Q.; Khalil, A.B.; He, J. Short-Term Power Load Forecasting for Combined Heat and Power Using CNN-LSTM Enhanced by Attention Mechanism. Energy 2023, 282, 128274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wei, Q.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net Architecture Design for Medical Image Segmentation Through the Lens of Transformers. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 97, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like Pure Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Tang, Y.; Nath, V.; Yang, D.; Myronenko, A.; Landman, B.; Xu, D. Unetr: Transformers for 3D Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 January 2022; pp. 574–584. [Google Scholar]

- Shaker, A.; Maaz, M.; Rasheed, H.; Khan, S.; Yang, M.H.; Khan, F.S. UNETR++: Delving into Efficient and Accurate 3D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 3377–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senin, P. Dynamic Time Warping Algorithm Review. Inf. Comput. Sci. Dep. Univ. Hawaii Manoa Honolulu USA 2008, 855, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Battery and Heating Data for Real Driving Cycles. IEEE DataPort 2022. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/battery-and-heating-data-real-driving-cycles (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Shieh, Y.T.; Wu, C.C.; Jeng, S.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Haung, C.C.; Chang, E.Y. A Turn-Ratio-Changing Half-Bridge CLLC DC–DC Bidirectional Battery Charger Using a GaN HEMT. Energies 2023, 16, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.C.; Shieh, Y.T.; Roy, R.; Jeng, S.L.; Chieng, W.H. Coprime Reconstruction of Super-Nyquist Periodic Signal and Sampling Moiré Effect. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, F.; Eguchi, K. Simulation of Power Electronics Converters Using PLECS®; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Case No |

U-Net | U-Net with SA | TS-MSDA-UNet | UNETR | UNETR++ | ||||||||||

| RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

RMSE (%) |

MAE (%) |

DTW (%) |

|

| 1 | 52.60 | 30.19 | 20.17 | 1.34 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 63.37 | 45.57 | 31.28 | 1.05 | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| 2 | 49.11 | 28.04 | 18.80 | 1.15 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 59.09 | 42.35 | 29.26 | 0.89 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| 3 | 46.20 | 26.28 | 17.59 | 1.36 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 55.48 | 39.57 | 27.30 | 1.04 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| 4 | 43.30 | 24.49 | 16.09 | 1.41 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 52.14 | 37.12 | 25.38 | 0.65 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

| 5 | 39.79 | 22.32 | 14.85 | 1.35 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 48.45 | 34.49 | 23.23 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| 6 | 37.20 | 20.60 | 13.65 | 1.24 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 45.25 | 31.98 | 21.45 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| 7 | 34.74 | 18.90 | 12.41 | 1.30 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 42.21 | 29.49 | 19.63 | 0.74 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| 8 | 31.68 | 16.60 | 10.70 | 1.36 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 38.54 | 26.28 | 17.18 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| 9 | 29.62 | 14.86 | 9.40 | 1.48 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 35.65 | 23.49 | 15.33 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| 10 | 27.76 | 13.10 | 8.11 | 1.07 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 33.62 | 21.14 | 13.49 | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| 11 | 26.24 | 11.34 | 6.85 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 32.09 | 18.74 | 11.65 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| 12 | 25.12 | 9.56 | 5.56 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 30.92 | 16.18 | 9.80 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| 13 | 24.47 | 7.89 | 4.32 | 0.41 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 30.16 | 13.62 | 8.09 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).