Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We introduce a novel Spectral Attention Module that integrates both time-domain and frequency-domain information to effectively capture local and global dependencies within time series data. It addresses frequency misalignment issues through the Extended Discrete Fourier Transform (EDFT) and utilizes a complex-valued spectral attention mechanism to identify and exploit intricate relationships among frequency combinations.

- We propose an innovative Bidirectional Variable Mamba that effectively captures and leverages complex relationships between multiple variables, enhancing the performance of multivariate time series forecasting.

- We present a comprehensive framework, called SpectroMamba that integrates the Spectral Attention and Variable Mamba modules. This unified approach is designed to tackle the challenges of multivariate time series forecasting and demonstrates superior performance on real-world datasets.

2. Related Works

2.1. Multivariate Time Series Forecasting

2.2. State Space Model

3. Preliminary

3.1. Problem Definition

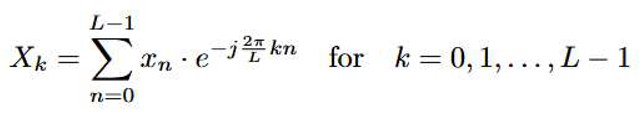

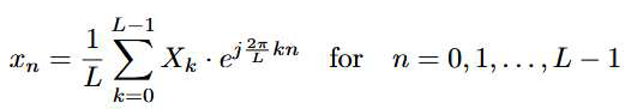

3.2. Discrete Fourier Transform

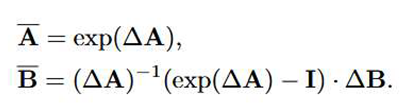

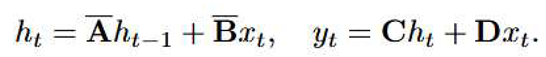

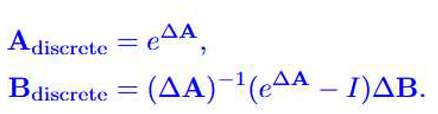

3.3. State Space Models

4. Proposed Method

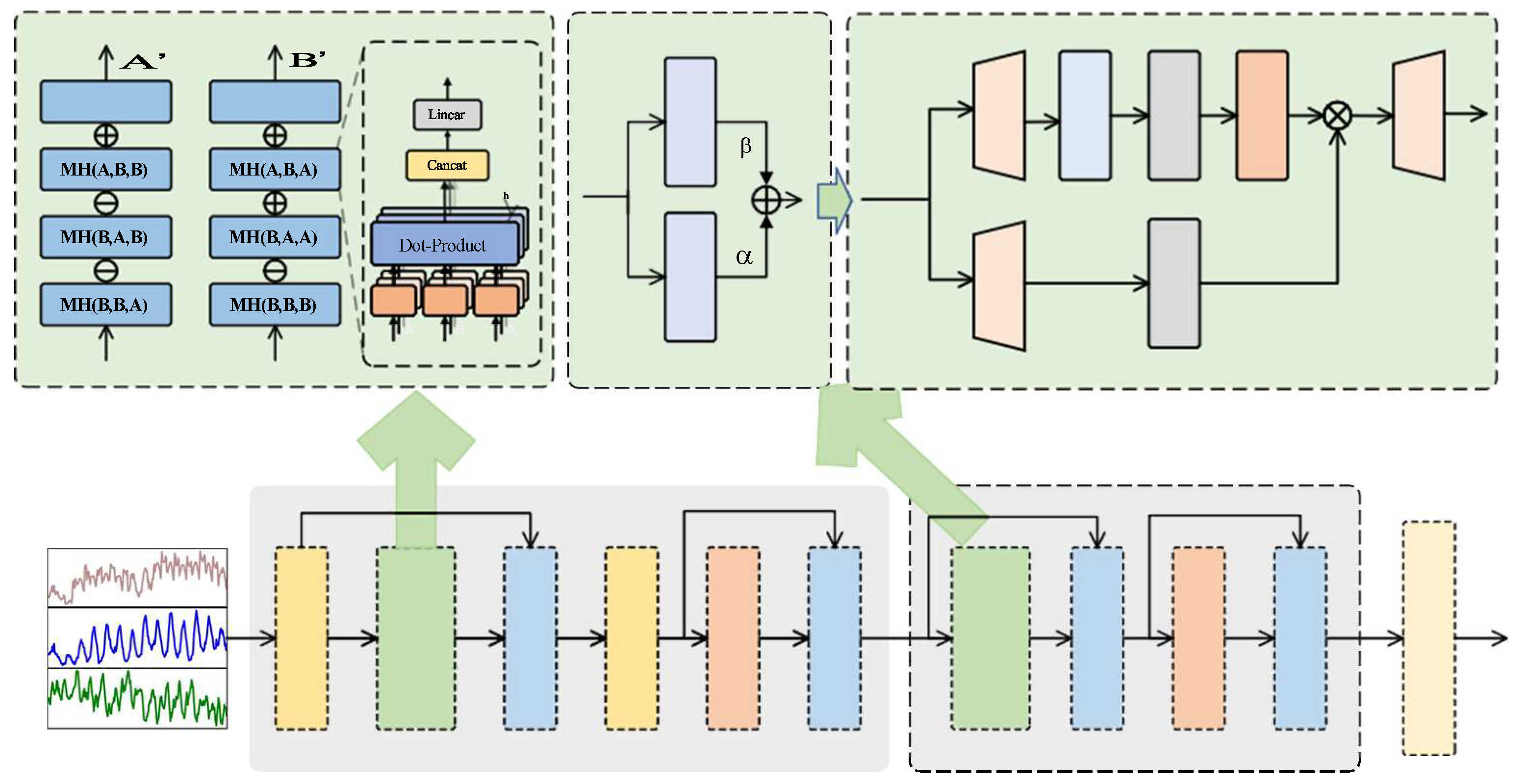

4.1. Overall Framework

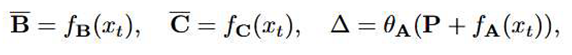

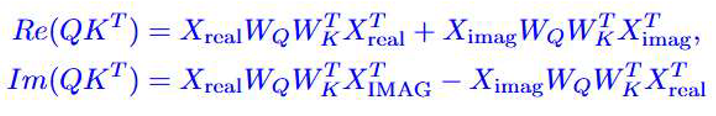

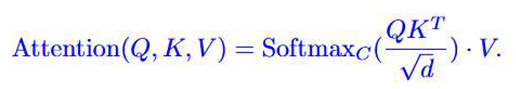

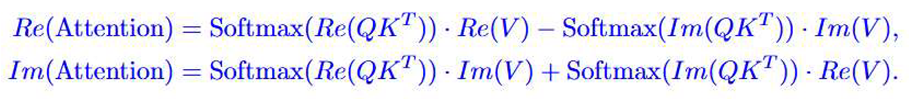

4.2. Spectral Attention Module

=

1, but directly normalizing the complex amplitude will inevitably lead to the

loss of phase information. By independently normalizing the real and imaginary

parts, we ensure the validity of the probability distribution in the real

subspace while retaining the statis- tical characteristics of the phase

difference, so that the model can better utilize the rich information provided

by the spectral phase.

=

1, but directly normalizing the complex amplitude will inevitably lead to the

loss of phase information. By independently normalizing the real and imaginary

parts, we ensure the validity of the probability distribution in the real

subspace while retaining the statis- tical characteristics of the phase

difference, so that the model can better utilize the rich information provided

by the spectral phase.

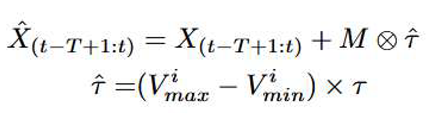

4.3. Bidirectional Variable Mamba

5. Experiments

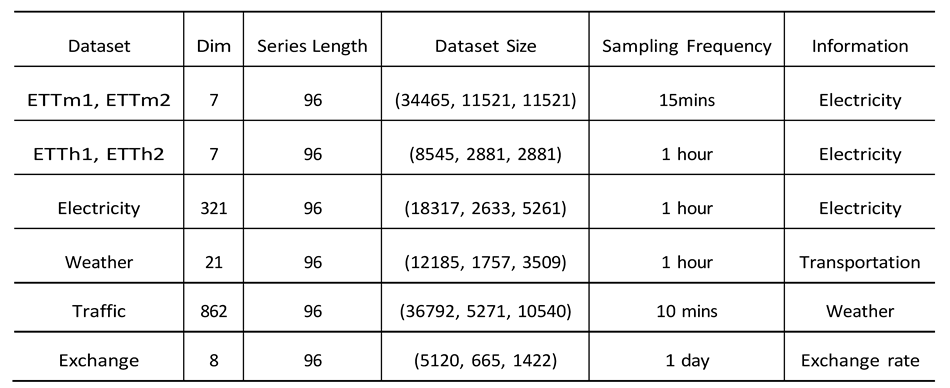

- ETT Dataset [7]: It originates from two power substations and spans from July 2016 to July 2018, recording seven variables, including load and oil temperature. The ETTm1 and ETTm2 datasets are recorded every 15 minutes, with a total of 69,680 time steps. The ETTh1 and ETTh2 datasets are hourly equivalents of ETTm1 and ETTm2, each containing 17,420 time steps.

- Electricity Dataset [19]: It contains hourly power consumption data from 321 users, covering a two-year period, with a total of 26,304 time steps.

- Solar-Energy Dataset [35]: It records solar energy generation from 137 photo- voltaic stations in Alabama in 2006, with samples taken every 10 minutes.

- Weather Dataset [19]: Collected by the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochem- istry’s weather stations in 2020, this dataset includes 21 meteorological factors, such as atmospheric pressure, temperature, and humidity, with data recorded every 10 minutes.

- Traffic Dataset [19]: Covering the period from July 2016 to July 2018, this dataset records road occupancy data from 862 sensors deployed on highways in the San Francisco Bay Area. The data is collected every hour, providing detailed temporal resolution to analyze traffic patterns and dynamics over the two-year period.

- Through experiments on these diverse real-world datasets, we demonstrate the per- formance of the SpectroMamba framework, validating its versatility and applicability across various scenarios.

5.1. Experimental Settings

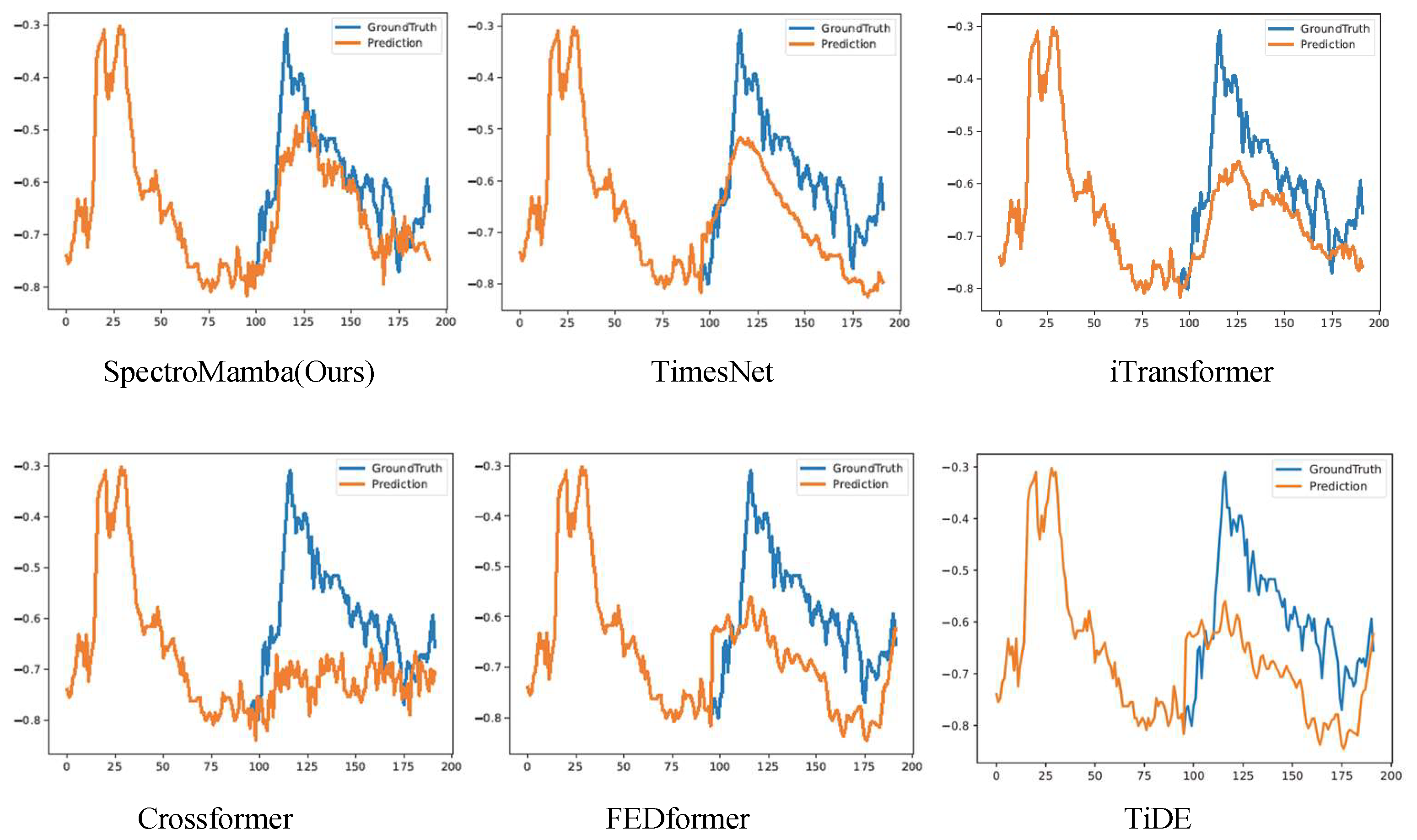

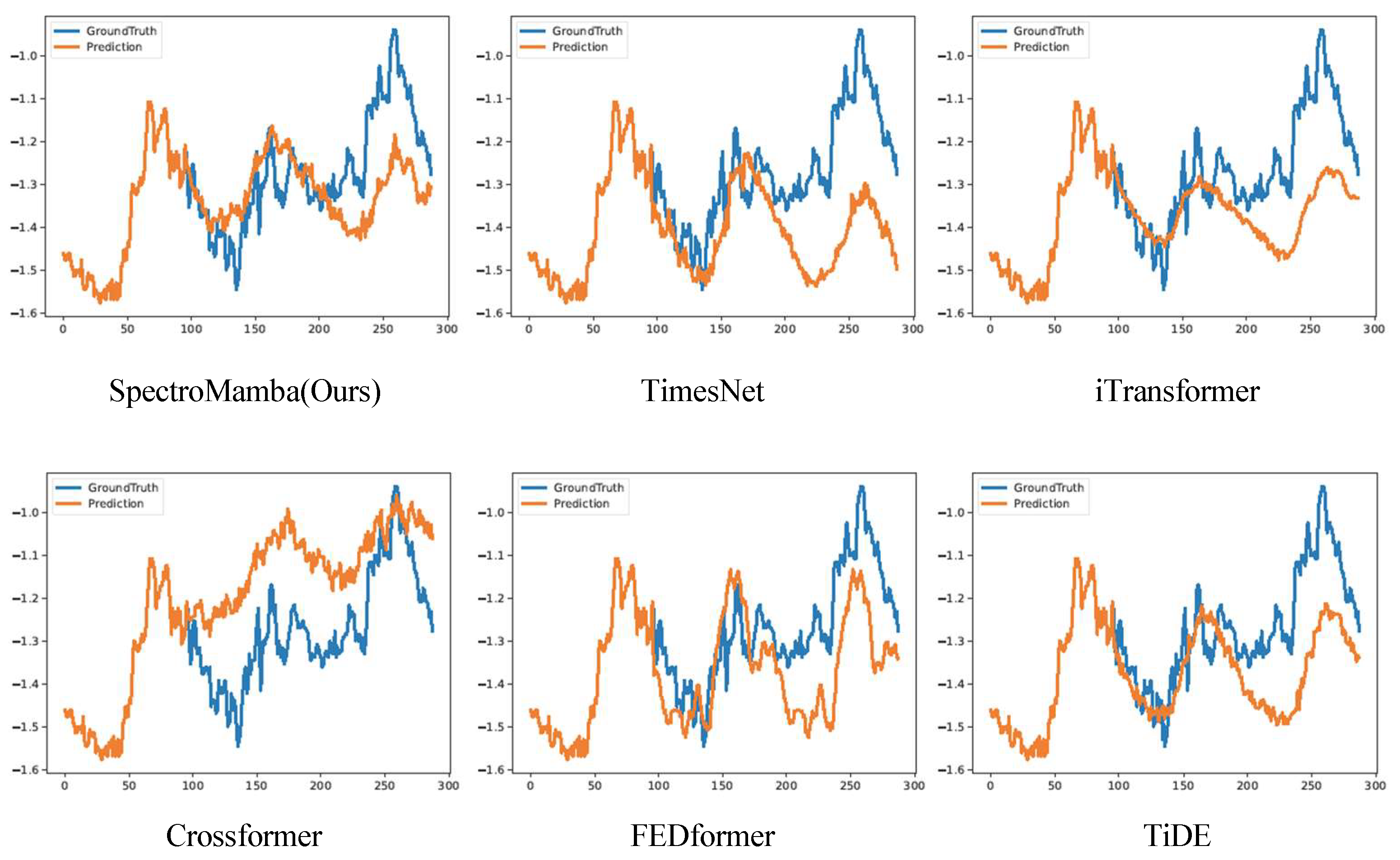

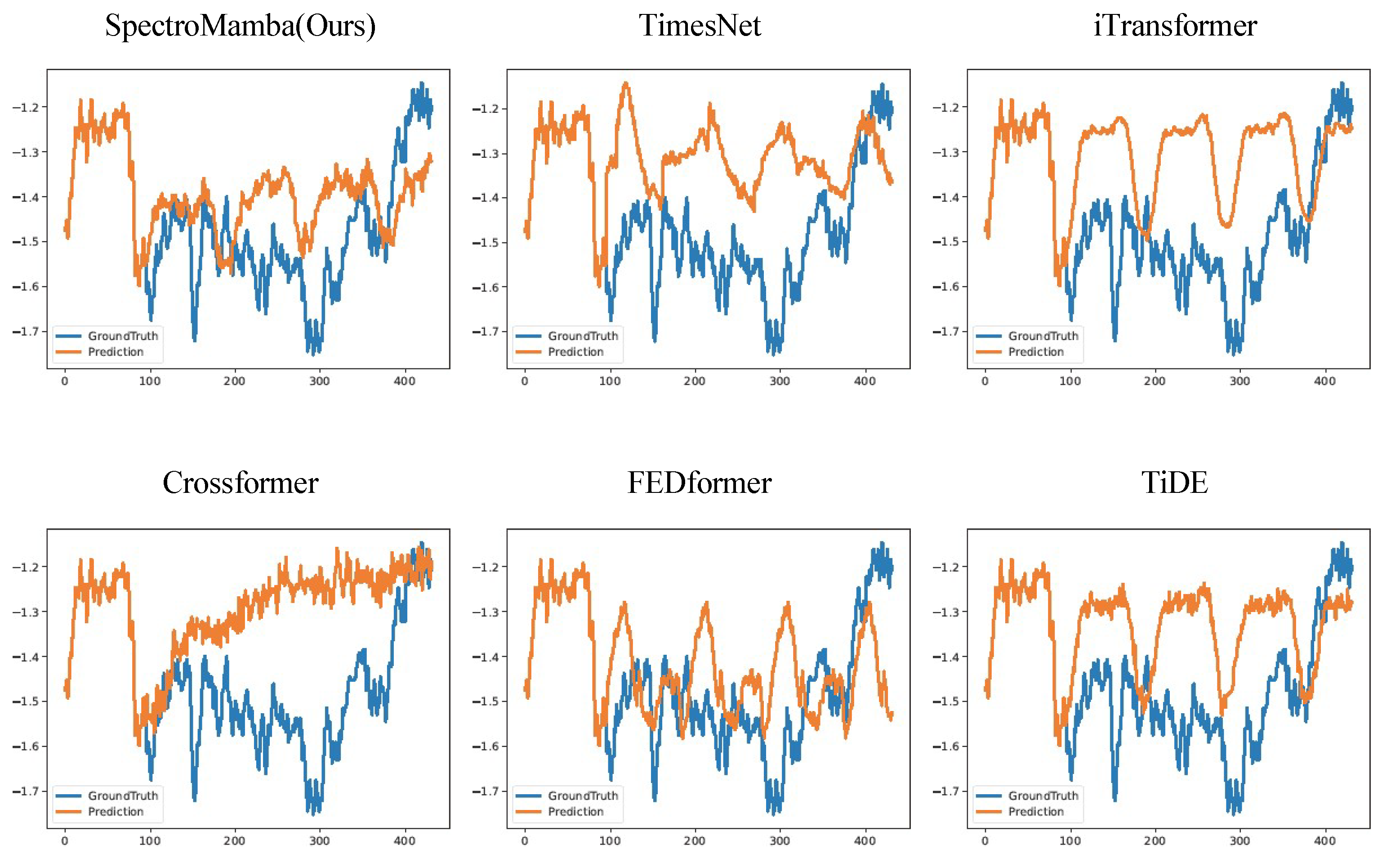

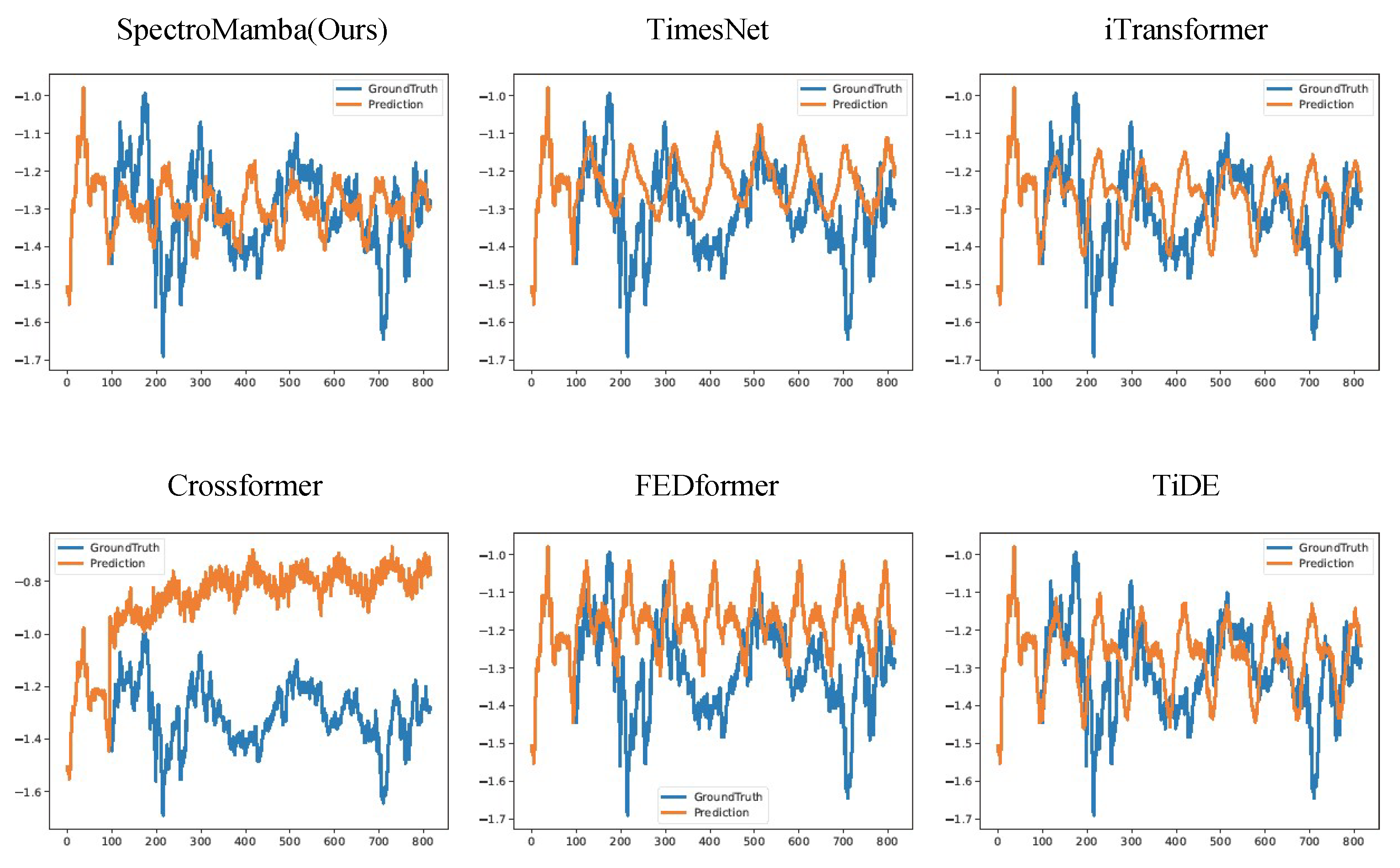

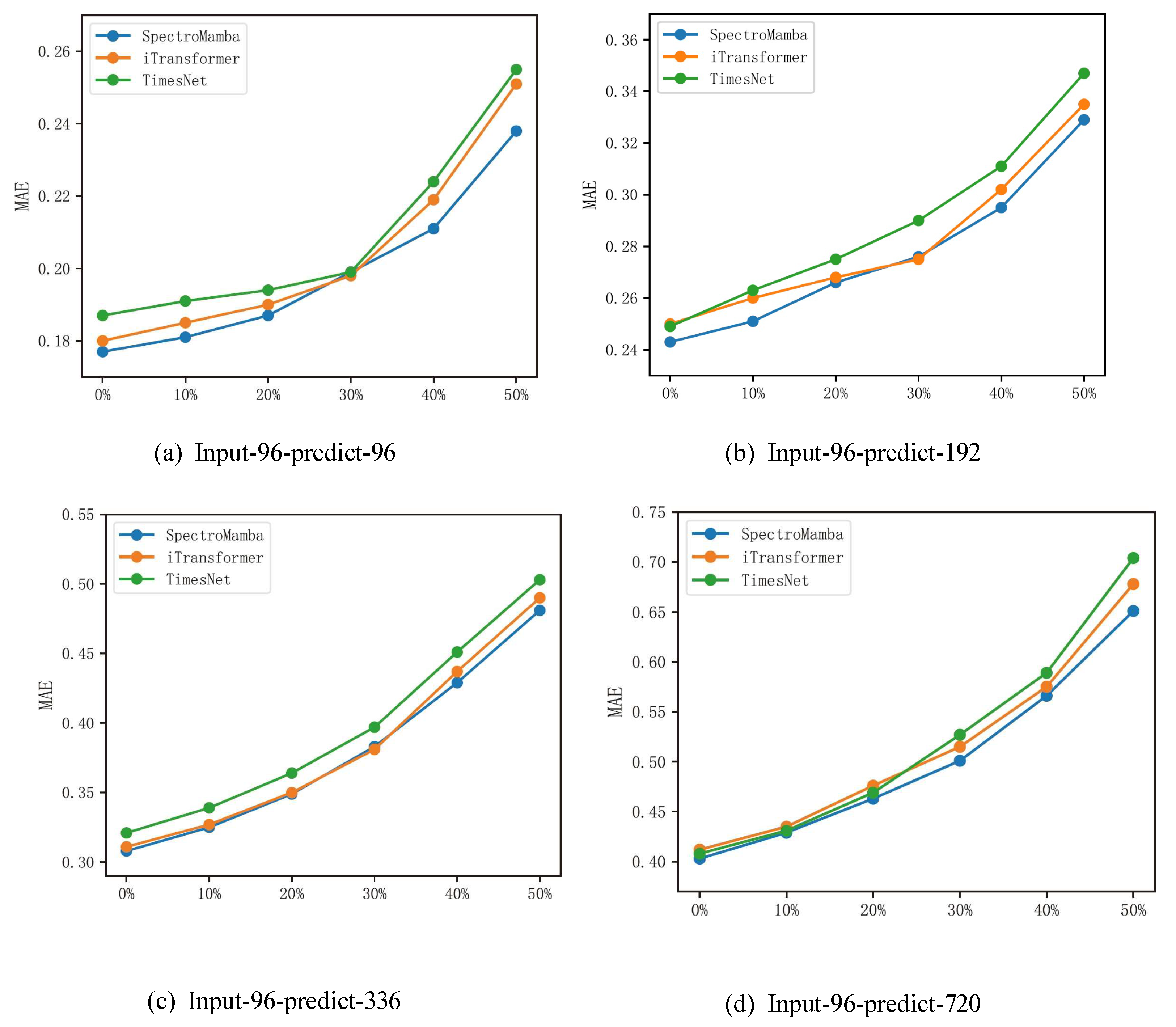

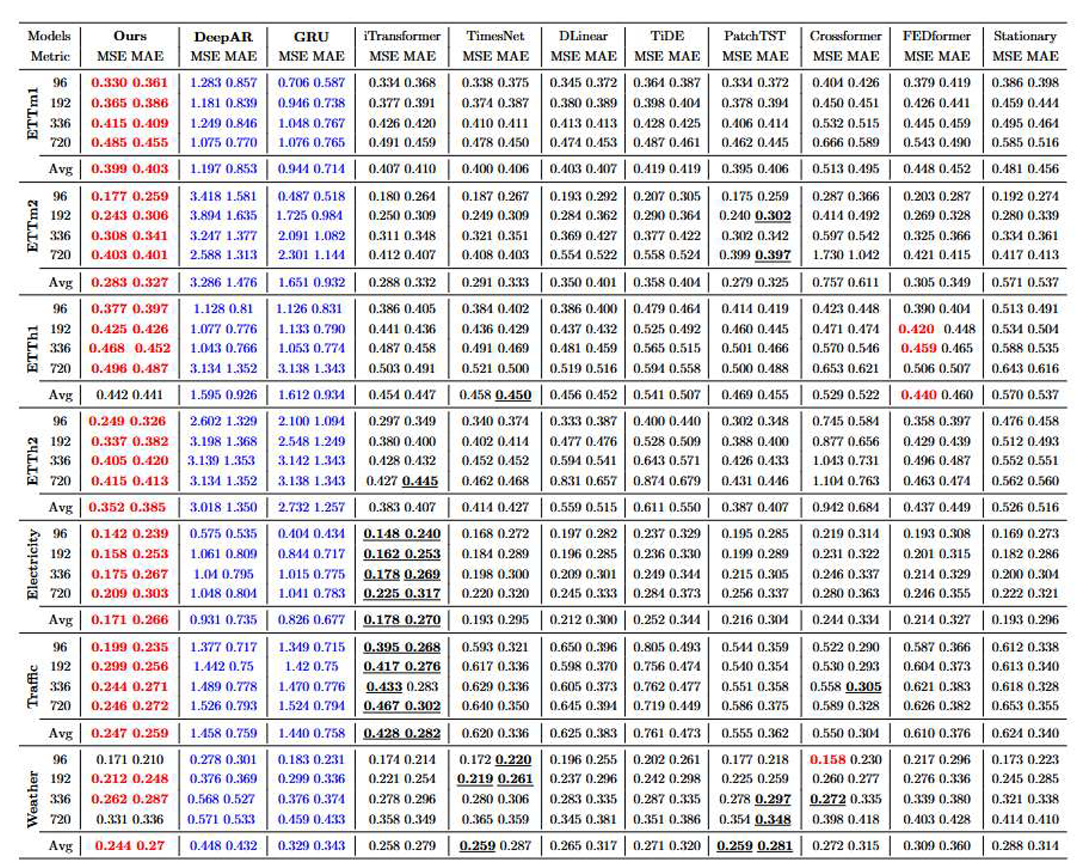

5.2. Compared to Sota Methods

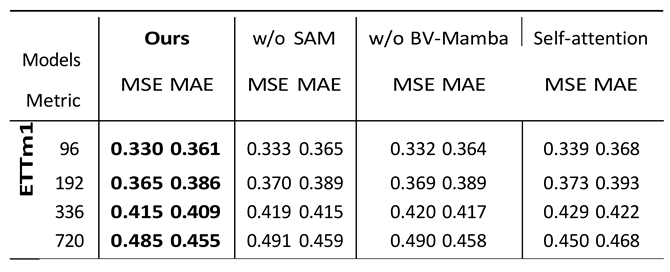

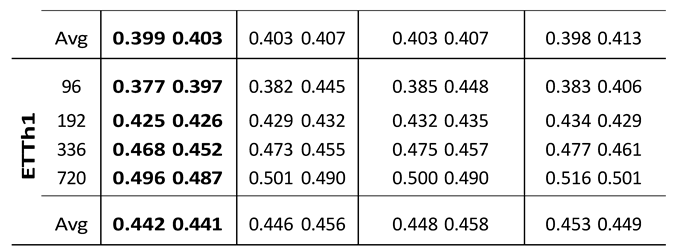

6. Ablation Study

Individual Component

7. Conclusion

References

- Zhuang, W., Fan, J., Fang, J., Fang, W., Xia, M.: Rethinking general time series analysis from a frequency domain perspective. Knowledge-Based Systems 301, 112281 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Yi, K., Zhang, Q., Fan, W., Wang, S., Wang, P., He, H., An, N., Lian, D., Cao, L., Niu, Z.: Frequency-domain mlps are more effective learners in time series forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

- Luo, Y., Lyu, Z., Huang, X.: Tfdnet: Time-frequency enhanced decomposed network for long-term time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.13386 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E., Jenkins, G.M., Reinsel, G.C., Ljung, G.M.: Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. John Wiley & Sons, (2015).

- Hochreiter, S.: Long short-term memory. Neural Computation MIT-Press (1997).

- Bai, S., Kolter, J.Z., Koltun, V.: An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.01271 (2018).

- Zhou, H., Zhang, S., Peng, J., Zhang, S., Li, J., Xiong, H., Zhang, W.: Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 35, pp. 11106–11115 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Zeng, A., Xu, Q.: Fits: Modeling time series with 10k parameters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.03756 (2023).

- Wu, H., Hu, T., Liu, Y., Zhou, H., Wang, J., Long, M.: Timesnet: Tem- poral 2d-variation modeling for general time series analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02186 (2022).

- Zhang, Y., Yan, J.: Crossformer: Transformer utilizing cross-dimension depen- dency for multivariate time series forecasting. In: The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

- Qi, S., Wen, L., Li, Y., Yang, Y., Li, Z., Rao, Z., Pan, L., Xu, Z.: Enhancing multivariate time series forecasting with mutual information-driven cross-variable and temporal modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.00869 (2024).

- Nie, Y., Nguyen, N.H., Sinthong, P., Kalagnanam, J.: A time series is worth 64 words: Long-term forecasting with transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.14730 (2022).

- Zhou, X., Wang, W., Buntine, W., Qu, S., Sriramulu, A., Tan, W., Bergmeir, C.: Scalable transformer for high dimensional multivariate time series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, pp. 3515–3526 (2024).

- Zeng, A., Chen, M., Zhang, L., Xu, Q.: Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 37, pp. 11121–11128 (2023).

- Zhou, T., Ma, Z., Wen, Q., Wang, X., Sun, L., Jin, R.: Fedformer: Fre- quency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In: International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 27268–27286 (2022). PMLR.

- Yu, G., Zou, J., Hu, X., Aviles-Rivero, A.I., Qin, J., Wang, S.: Revitalizing multi- variate time series forecasting: Learnable decomposition with inter-series depen- dencies and intra-series variations modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12694 (2024).

- Yu, C., Wang, F., Shao, Z., Sun, T., Wu, L., Xu, Y.: Dsformer: A double sampling transformer for multivariate time series long-term prediction. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, pp. 3062–3072 (2023).

- Liu, Y., Hu, T., Zhang, H., Wu, H., Wang, S., Ma, L., Long, M.: itransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06625 (2023).

- Wu, H., Xu, J., Wang, J., Long, M.: Autoformer: Decomposition transform- ers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Advances in neural information processing systems 34, 22419–22430 (2021).

- Zhou, T., Ma, Z., Wen, Q., Sun, L., Yao, T., Yin, W., Jin, R., et al.: Film: Frequency improved legendre memory model for long-term time series forecasting. Advances in neural information processing systems 35, 12677–12690 (2022).

- Sun, F.-K., Boning, D.S.: Fredo: frequency domain-based long-term time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.12301 (2022).

- Cao, D., Wang, Y., Duan, J., Zhang, C., Zhu, X., Huang, C., Tong, Y., Xu, B., Bai, J., Tong, J., et al.: Spectral temporal graph neural network for multivariate time-series forecasting. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 17766–17778 (2020).

- Chiu, C.-C., Raffel, C.: Monotonic chunkwise attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.05382 (2017).

- Wang, J., Zhu, W., Wang, P., Yu, X., Liu, L., Omar, M., Hamid, R.: Selective structured state-spaces for long-form video understanding. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 6387– 6397 (2023).

- Ali, A., Zimerman, I., Wolf, L.: The hidden attention of mamba models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.01590 (2024).

- Yang, S., Wang, Y., Chen, H.: Mambamil: Enhancing long sequence modeling with sequence reordering in computational pathology. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 296–306 (2024). Springer.

- Qiao, Y., Yu, Z., Guo, L., Chen, S., Zhao, Z., Sun, M., Wu, Q., Liu, J.: Vl-mamba: Exploring state space models for multimodal learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.13600 (2024).

- Lu, Y., Wang, S., Wang, Z., Xia, P., Zhou, T., et al.: Lfmamba: Light field image super-resolution with state space model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12463 (2024).

- Burke, K., Wagner, L.O.: Dft in a nutshell. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 113(2), 96–101 (2013).

- Oppenheim, A.V., Verghese, G.C.: Signals, Systems & Inference. Pearson London, (2017).

- Gu, A., Dao, T.: Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752 (2023).

- Gu, A., Johnson, I., Goel, K., Saab, K., Dao, T., Rudra, A., R´e, C.: Combin- ing recurrent, convolutional, and continuous-time models with linear state space layers. Advances in neural information processing systems 34, 572–585 (2021).

- Gu, A., Dao, T., Ermon, S., Rudra, A., R´e, C.: Hippo: Recurrent memory with optimal polynomial projections. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 1474–1487 (2020).

- Kim, T., Kim, J., Tae, Y., Park, C., Choi, J.-H., Choo, J.: Reversible instance normalization for accurate time-series forecasting against distribution shift. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

- Lai, G., Chang, W.-C., Yang, Y., Liu, H.: Modeling long-and short-term tempo- ral patterns with deep neural networks. In: The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 95–104 (2018).

- Chicco, D., Warrens, M.J., Jurman, G.: The coefficient of determination r-squared is more informative than smape, mae, mape, mse and rmse in regression analysis evaluation. Peerj computer science 7, 623 (2021).

- Liu, Y., Wu, H., Wang, J., Long, M.: Non-stationary transformers: Exploring the stationarity in time series forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 9881–9893 (2022).

- Das, A., Kong, W., Leach, A., Mathur, S., Sen, R., Yu, R.: Long-term forecasting with tide: Time-series dense encoder. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08424 (2023).

- Liu, M., Zeng, A., Chen, M., Xu, Z., Lai, Q., Ma, L., Xu, Q.: Scinet: Time series modeling and forecasting with sample convolution and interaction. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 5816–5828 (2022).

- Salinas, D., Flunkert, V., Gasthaus, J., Januschowski, T.: Deepar: Probabilis- tic forecasting with autoregressive recurrent networks. International journal of forecasting 36(3), 1181–1191 (2020).

- Cho, K., Van Merri¨enboer, B., Gulcehre, C., Bahdanau, D., Bougares, F., Schwenk, H., Bengio, Y.: Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder- decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.1078 (2014).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).