1. Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have shown clinical activity for patients with

EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Multiple clinical trials have shown that EGFR-TKIs provide better efficacy than conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC [

1,

2,

3]. In addition, a pivotal phase III study showed that treatment with osimertinib, as third-generation EGFR-TKI, has provided superior efficacy compared with treatment with first-generation EGFR-TKIs, including erlotinib and gefitinib [

4,

5]. Recent pivotal clinical trials have led to an evolution in the standard of care for patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC. The FLAURA2 and MARIPOSA studies demonstrated that novel combination therapies confer significant clinical benefits in patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Specifically, the combination of amivantamab and lazertinib in the MARIPOSA trial, as well as the combination of platinum-based chemotherapy and osimertinib in the FLAURA2 trial, both showed improved progression-free survival and favourable efficacy profiles compared with the current standard of care, osimertinib monotherapy [

6,

7]. However, the development of resistance to EGFR-TKIs remains almost inevitable and continues to pose a major challenge to achieving prolonged survival in patients [

8]. Although multiple resistance mechanisms to third-generation EGFR-TKIs—such as C797S mutation, MET amplification, and BRAF mutations—have been identified, effective strategies to fully overcome these challenges remain elusive [

9]. "Oligometastatic disease was first conceptualized by Hellman and Weichselbaum in 1995 as an intermediate state between localized and widespread systemic disease, defined by a limited number and sites of metastases. Initially proposed in the context of stage IV breast cancer, this paradigm has since been recognized across multiple tumor types, suggesting a distinct biological state potentially amenable to curative-intent local therapies [

10]. Initially, oligometastatic disease described a specific condition in which there were few metastatic lesions at the time of diagnosis. However, the concept has since evolved to encompass broader clinical scenarios, including oligopersistence (oligo-residual disease after systemic therapy) and oligo-progressive disease (Oligo-PD; limited progression with otherwise effective systemic treatment) [

11]. These broader definitions underscore a deeper understanding of the biological heterogeneity inherent in metastatic dissemination and have important therapeutic implications, particularly with the integration of local ablative therapies into multimodal treatment strategies [

11].

Local ablative therapy (LAT) has shown promising high regional control of involved lesions and potential survival benefits for patients with oligometastatic NSCLC [

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, in patients with oligo-residual disease—where individuals with EGFR-mutated NSCLC transition to an oligometastatic state following a period of EGFR-TKI therapy—there is emerging evidence suggesting that the addition of local ablative therapy (LAT) to target residual lesions may confer further clinical benefit [

15]. Additionally, Oligo-PD refers to the progression of a few lesions or new lesions during EGFR-TKI treatment. In patients with Oligo-PD, additional LAT for progressive lesions and continued EGFR-TKI therapy may be more effective than conventional salvage chemotherapy [

16].

This review highlights evolving multidisciplinary treatment strategies for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC. It focuses on current and emerging therapeutic options tailored to specific clinical scenarios, including oligometastatic disease at diagnosis, oligo-residual disease emerging during EGFR-TKI treatment, and oligo-progressive disease after the development of resistance. By exploring these distinct disease states, we aim to provide practical insights into how local and systemic therapies can be integrated to optimize patient outcomes.

2. Oligometastatic Disease in EGFR-Mutated NSCLC

2.1. Concept of Oligometastatic Disease

Hellman and Weichselbaum originally proposed oligometastatic disease as an intermediate state between local and advanced breast cancer [

10]. Oligometastatic disease is increasingly recognized as a distinct clinical state in which cancer exhibits limited metastatic potential, resulting in a slower progression and fewer lesions. In particular, synchronous oligometastatic disease refers to cases where both the primary tumor and a small number of metastases are present simultaneously, offering a unique therapeutic window in which all visible disease sites may be effectively targeted with LAT.

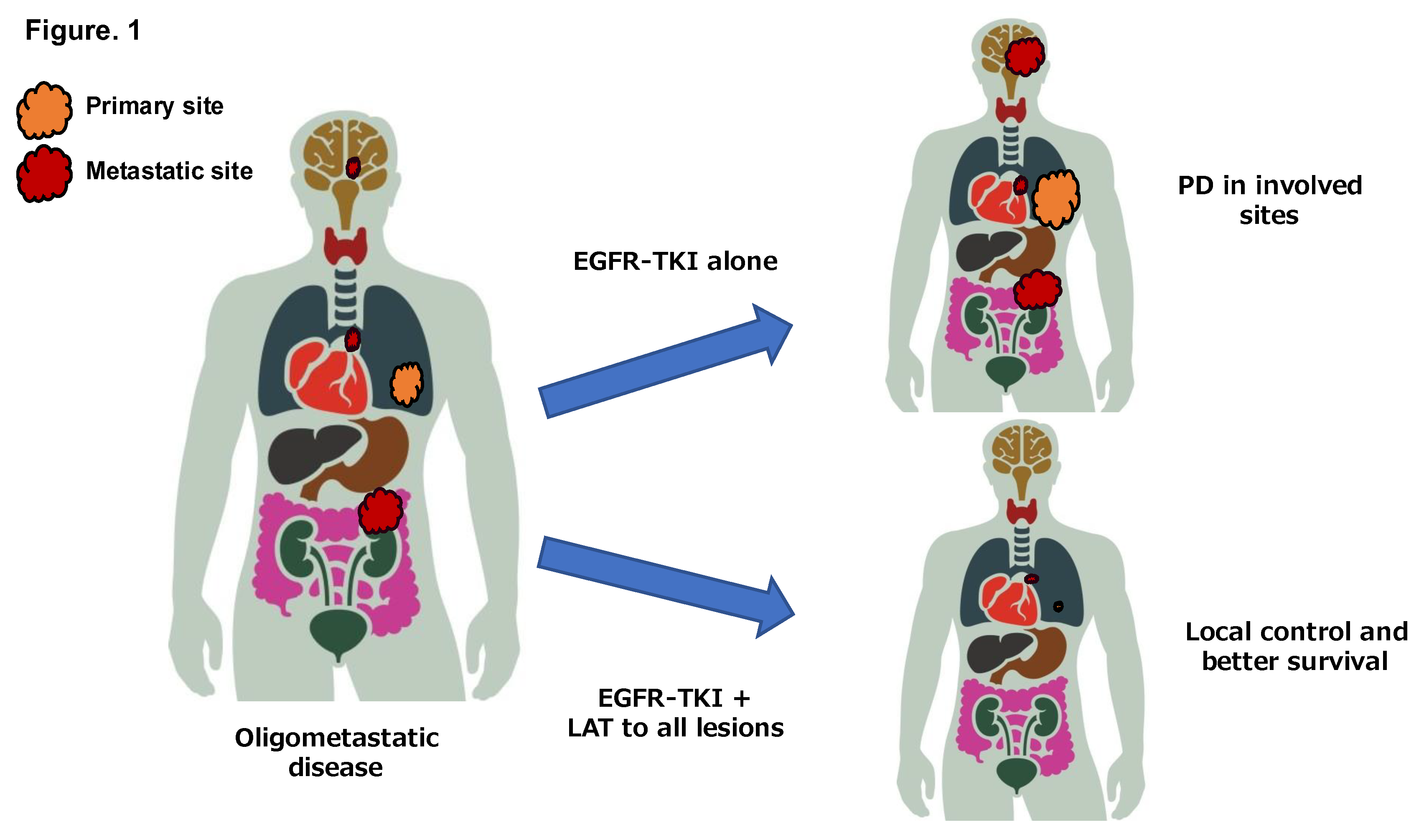

In patients with oligometastatic NSCLC, progressive disease (PD) after first-line chemotherapy has been shown to be substantially limited to the involved sites of disease (

Figure 1). Retrospective studies examining the patterns of progression of oligometastatic NSCLC patients have demonstrated that 70%-90% of the patients develop PD limited to previous involved disease sites after first-line systemic therapy [

17,

18]. Furthermore, almost half of the patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC have PD limited to previous localized disease after first-line treatment with EGFR-TKIs [

19,

20,

21]. Synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC accounts for a variable prevalence of approximately 20-30% of advanced NSCLC and represents a not-rare population [

22,

23].

Previous studies and guidelines have defined synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC differently, with the definitions including 1-3 metastases or 1-5 metastases [

18,

24,

25,

26]. To date, no standard definition of synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC has been identified. Patients with synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC have been frequently defined as those with 1-3 metastases or 1-5 metastases in recent phase III trials [

27,

28,

29,

30].

Furthermore, in a survey by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), nearly half of the respondents indicated 1-3 metastases as the criteria for synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC [

25]. Whereas, the European Multidisciplinary Consensus Group proposed the criteria for synchronous oligometastatic disease as 1-5 metastases and 1-3 metastatic organs [

31]. Furthermore, a single-institution retrospective study suggested that the presence of 1–3 metastases may serve as a reasonable criterion for defining synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC, based on observed patterns of progression following first-line systemic therapy [

18]. Furthermore, in a survey with 444 physicians in the EORTC, about half of the respondents answered that the standard number of metastases for synchronous oligometastatic disease of NSCLC would be 1-3 metastases [

32].

2.3. Clinical Trials for Oligometastatic Disease

Several clinical trials have suggested that LAT may offer survival benefits in patients with oligometastatic NSCLC, regardless of driver gene mutation status [

12,

33,

34,

35]. "In a randomized phase II trial enrolling patients with oligometastatic NSCLC, the incorporation of LAT into standard systemic treatment resulted in significantly improved clinical outcomes compared with systemic therapy alone. The median PFS was 14.2 months versus 4.4 months (

P = 0.022), and the median OS was 41.2 months versus 17.0 months (

P = 0.017) [

13]. Another randomized phase II trial in patients with oligometastatic NSCLC demonstrated significantly improved efficacy with the addition of LAT (

P = 0.01), reporting a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 9.7 months in the LAT group compared to 3.5 months in the maintenance therapy group following initial systemic treatment [

36].

The was a randomized phase II trial evaluating the role of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) in patients with a controlled primary tumor and 1–5 metastatic lesions. The study demonstrated that the addition of SABR to standard palliative care significantly improved both OS and PFS in patients with oligometastatic solid cancer. Specifically, median OS was 41.0 months in the SABR group versus 28.0 months in the control group (

P = 0.006), and median PFS was 11.6 months compared to 5.4 months (

P = 0.001) [

14].

In recent years, the first prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of a multidimensional approach combining immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy and local ablative therapy (LAT) in patients with driver mutation-negative or unknown NSCLC has been reported. This is a single-arm, phase II study that evaluated the efficacy of pembrolizumab following radical local therapy (LAT) in 45 patients with metastatic NSCLC. The primary endpoint of progression-free survival from the start of LAT (PFS-L) was 19.1 months, significantly exceeding the previous benchmark of 6.6 months (

P = 0.005) [

37].

Multidisciplinary treatment development has also progressed in EGFR-mutated NSCLC with oligometastatic disease. In a recent phase III trial involving patients with EGFR-mutated oligometastatic NSCLC, the addition of LAT to first-generation EGFR-TKIs (LAT + TKI arm) significantly improved both PFS and OS compared to EGFR-TKIs alone (TKI arm), with median PFS of 20.2 vs. 12.5 months (

P < 0.001) and median OS of 25.5 vs. 17.4 months (

P < 0.001), respectively [

38].

A recent phase III trial demonstrated that the addition of thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) to EGFR-TKI therapy significantly improved survival in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC and oligo-organ metastases. Among 136 patients with ≤5 metastatic lesions in ≤2 organs, median PFS was 13.8 vs. 10.1 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.56;

P = 0.006) and median OS was 31.2 vs. 24.5 months (HR 0.59;

P = 0.030) in the TRT and control arms, respectively [

39].

Notably, these studies utilized first-generation EGFR-TKIs, rather than third-generation agents, which have since become the standard therapeutic approach in this clinical setting [

40]. Furthermore, the frequency of synchronous oligometastatic disease in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC constitutes a rare population (6%) [

15]. Therefore, the clinical benefit of incorporating LAT in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with synchronous oligometastatic disease remains insufficiently established.

Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the combination of LAT with third-generation EGFR-TKIs provides optimal benefits, necessitating clinical trials investigating the efficacy of a combination of third-generation EGFR-TKIs and LAT. A single-arm phase II study evaluating the efficacy of osimertinib plus LAT in

EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with synchronous oligometastatic disease is currently ongoing (NCT04908956). In addition, a randomized phase II trial comparing lazertinib, as third-generation EGFR-TKI, plus LAT to lazertinib alone for patients with synchronous oligometastatic

EGFR-mutated NSCLC has been ongoing (NCT05167851). The results of these ongoing clinical trials for patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC and synchronous oligometastatic disease could provide the basis for new therapeutic approaches in the future. In addition, a randomized phase II trial comparing molecular-targeted therapy plus LAT to residual lesions versus molecular-targeted therapy alone is ongoing for patients with

EGFR-mutated /

ALK-rearranged oligometastatic NSCLC (NCT05277844) (

Table 1).

3. Oligo-Residual Disease in EGFR-Mutated NSCLC

3.1. Concept of Oligopersistent Disease / Oligo-Residual Disease

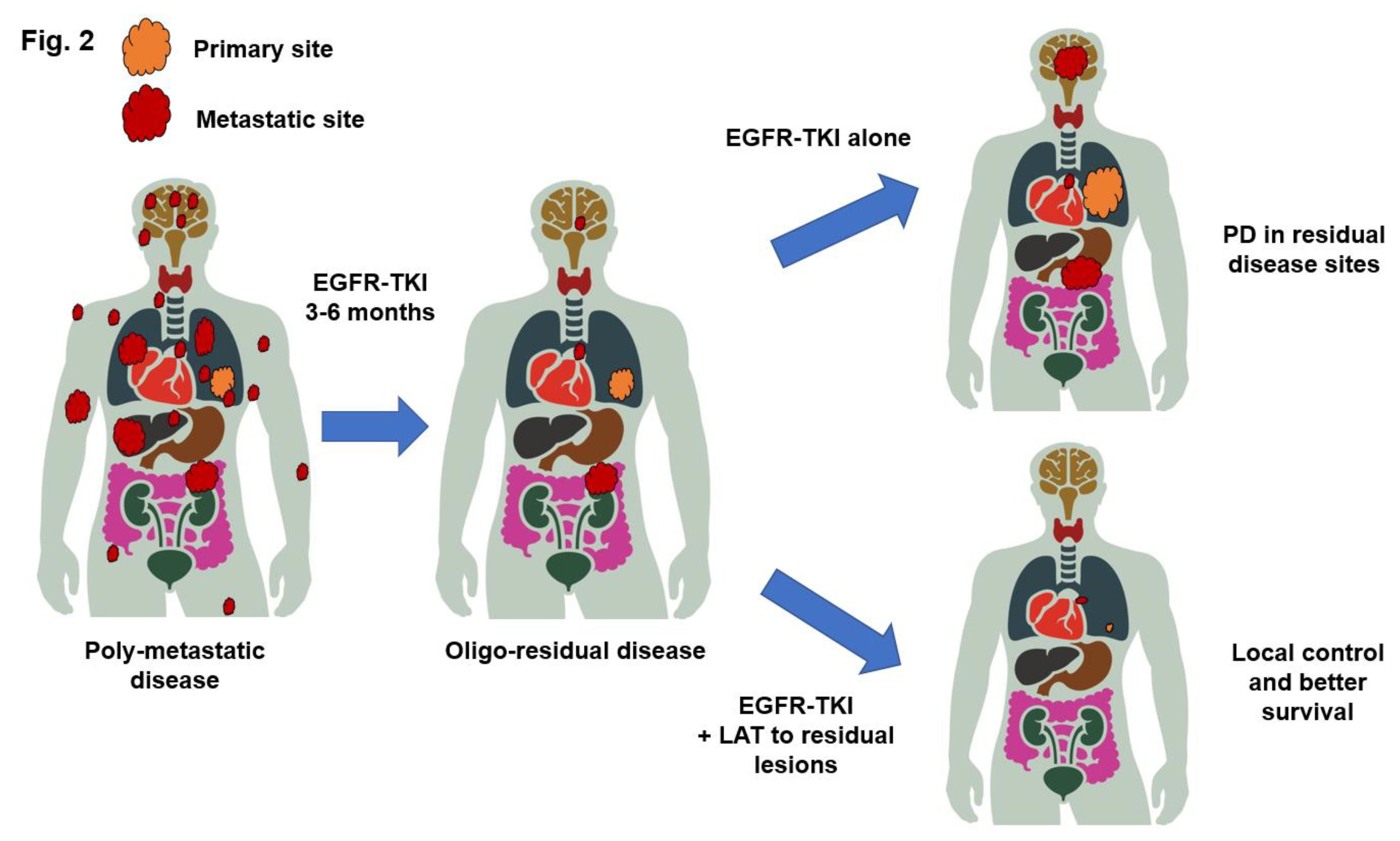

In the ESTRO/EORTC consensus on the characterization and classification of oligometastatic disease, the concepts of oligoresidual and oligopersistent disease were introduced to reflect evolving clinical scenarios in which patients, initially diagnosed with polymetastatic cancer, achieve a limited number of residual or persistent metastases following systemic therapy—highlighting the dynamic nature of metastatic progression and the need to redefine oligometastasis not only by the number of lesions, but also by disease biology and treatment response [

11]. Although most patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC respond to EGFR-TKIs, nearly all patients develop EGFR-TKI resistance. Unfortunately, few effective salvage systemic therapy options are available after the development of resistance to EGFR-TKIs [

41,

42]. Complete responses remain rare even with EGFR-TKIs, and almost all patients have a certain burden of residual disease, even with the best response. The addition of LAT to residual disease during the best response to EGFR-TKIs has been hypothesized to eliminate resistant clones and potentially lead to a better response duration (

Figure 2) [

43].

In metastatic NSCLC or colorectal cancer, oligo-residual disease (also known as oligo-persistent disease) is a newly proposed disease setting, and several retrospective studies have shown that LAT at all sites of residual disease shows favorable efficacy in patients with oligo-residual disease [

34,

44,

45,

46]. Oligo-residual disease represents a state of conversion from multiple initial metastases to oligometastatic disease induced by effective systemic therapy.

The results of a previous study showed that the majority of patients with oligo-residual disease had PD limited to residual sites after EGFR-TKI treatment, providing a rationale for LAT of all disease sites in patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC and oligo-residual disease. Furthermore, only 6% of the patients had synchronous oligometastatic disease before treatment, which increased to 32% after treatment. These findings suggest that EGFR-TKI treatment for 3 months increases the number of patients eligible for LAT by more than fivefold [

15]. In addition, osimertinib treatment was found to be an independent predictor of oligo-residual disease and PD limited to the residual sites. Therefore, osimertinib has replaced the standard of care for

EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients, which suggests that oligo-residual diseases are more significant.

Recent studies have defined oligo-residual disease by the presence of 1-4 residual lesions, including the primary site, at 3-6 months after the initiation of EGFR-TKI therapy. Residual disease was defined by the presence of detectable lesions on imaging–3-6 months after EGFR-TKI therapy. The definition of oligo-residual disease varies from trial to trial and no definitive criteria have yet been identified.

3.3. Clinical Trials for Oligo-Residual Disease

The first large retrospective study of oligo-residual disease divided patients into three groups according to the category of LAT to residual sites: the all-LAT group (patients who received LAT to all residual lesions, including primary sites, lymph nodes, and metastases), the part-LAT group (patients who received LAT to primary sites or other metastatic sites), and the non-LAT group (patients who received no prior LAT anywhere). The median OS in the all-LAT, part-LAT, and non-LAT groups were 40.9, 34.1, and 30.8 months, respectively (

P < 0.001). This retrospective study revealed that consolidative LAT may improve the survival outcomes of

EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who had oligo-residual disease during first-line EGFR-TKI therapy [

34].

However, few prospective studies have evaluated whether the addition of LAT to residual disease provides survival benefits. A recent single-arm phase II trial explored the efficacy of adding LAT to the treatment of residual disease in patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC who achieved oligo-residual disease after 3 months of EGFR-TKI treatment. Among the 16 patients included in the analysis, the median PFS and OS for EGFR-TKI were 15.2 months and 43.3 months, respectively. Furthermore, patients included in the analysis had significantly better PFS than those who failed screening, suggesting that additional LAT was associated with a reduced risk of PD (HR: 0.41,

P = 0.0097;

Table 2) [

44].

Another randomized phase II study of osimertinib with or without local consolidation therapy for EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with oligo-residual disease (NCT03410043) is currently ongoing. A randomized phase II study of consolidative radiotherapy for residual lesions during osimertinib monotherapy (ORIHALCON trial/WJOG13920L, JRCTs041220115) evaluated patients who received osimertinib monotherapy for at least 90 days but not more than 120 days at the time of enrollment after the initiation of first-line osimertinib monotherapy. Patients with residual disease at the time of enrollment based on the following definitions, with a total of three or fewer residual lesions. The results of these prospective randomized trials highlight the significance of additional LAT for patients with NSCLC with oligo-residual disease (

Table 2).

4. Current Status of Oligo-PD

4.1. Concept of Oligo-PD

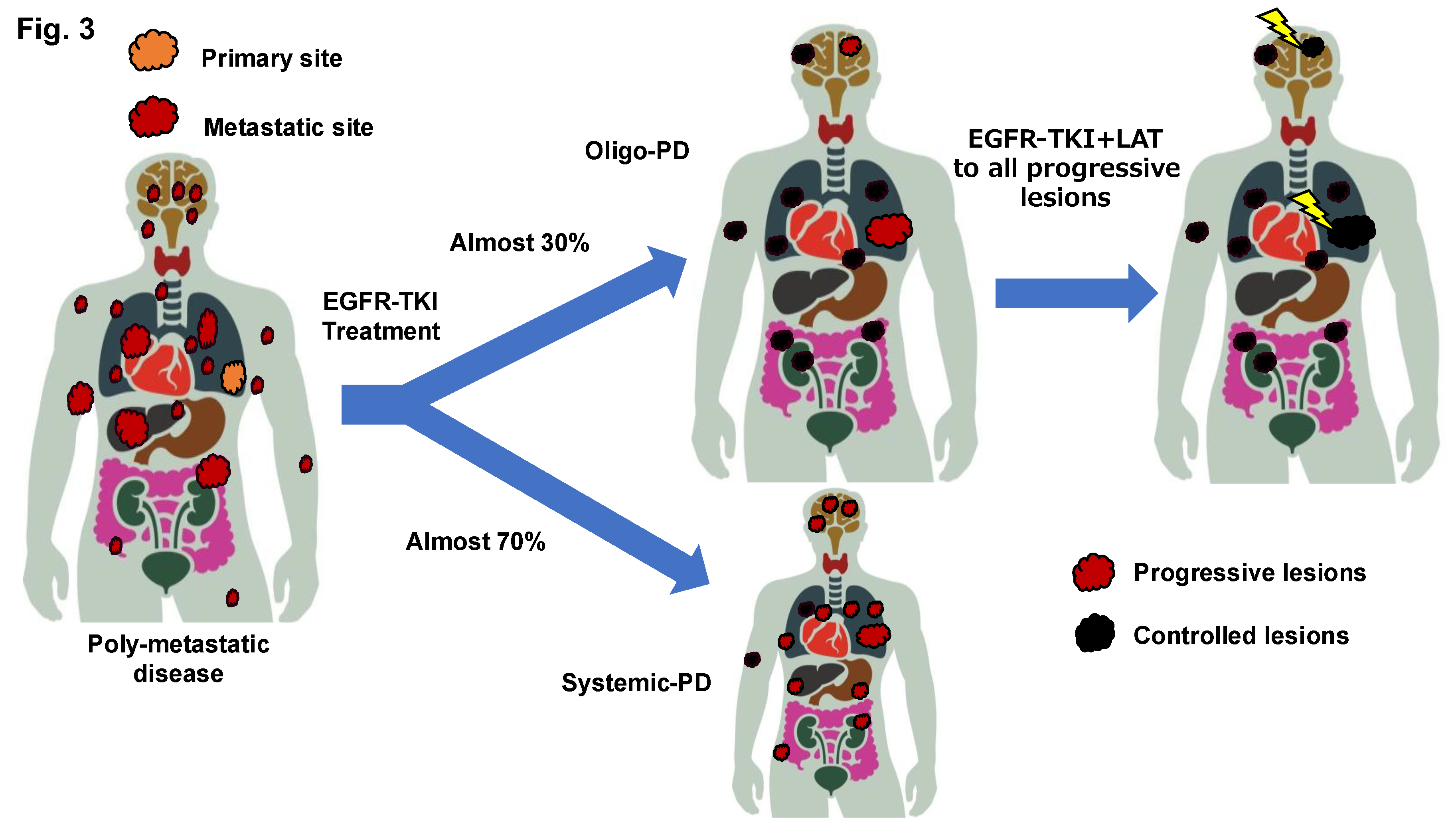

Oligo-progression (Oligo-PD) might be a relatively new concept that has emerged with the development of more effective systemic therapies, indicating the progression of few lesions in patients whose disease has been extensively controlled by systemic therapy [

11,

47]. A recent consensus of the American Radium Society (ARS) recommends that the criteria for Oligo-PD be restricted to 1-3 sites of progression [

48]. Furthermore, previous studies showed the addition of LAT to the lesions of progression may provide additional survival benefit in patients with Oligo-PD during PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy [

49,

50].Focal/regional progression (with overall disease control at other sites) can occur due to tumor heterogeneity, with the selective pressure of EGFR-TKIs causing the outgrowth of subclones with pre-existing or acquired alterations conveying a fitness advantage. The resistant subclones may be spatially confined to distinct anatomical sites because of factors such as local microenvironments and the timing of branch points in clonal evolution with respect to site seeding. This pattern of localized drug resistance or pharmacokinetic failure raises the possibility that local therapies can be used to address resistant subclones or sanctuary sites, and prolong the clinical benefits of ongoing TKI therapy.

Previous studies have shown that LAT may eliminate resistant subclones in a few progressive lesions and prevent local symptoms and further complications from tumor proliferation [

35]. On the basis of these principles, the addition of LAT may be beneficial for patients with Oligo-PD during pembrolizumab monotherapy or PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy plus chemotherapy.

Oligo-PD is generally assumed to be a consequence of the development of isolated resistant subclones that occur only at a few metastatic sites and emerge when more effective systemic therapies are available. In

EGFR-mutated NSCLC, Oligo-PD has been proposed to be histologically heterogeneous, with coexisting tumor cells that are resistant and sensitive to EGFR-TKIs [

51,

52].

Although approximately half of patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC have been suggested to develop PD during treatment with EGFR-TKIs and this has been exclusively attributed to existing lesions, it remains unclear whether the pattern of disease progression during EGFR-TKI treatment varies according to the number of metastatic lesions (

Figure 3). The results of the FLURA trial have shown that the proportion of patients with PD limited to residual disease was higher in the osimertinib arm, at 81%, compared to 63% in the first-generation EGFR TKI arm [

53]. In addition, a recent nationwide cohort study in Switzerland showed that 77% of 147 patients who received osimertinib in the first-line setting had Oligo-PD [

54].

As recommended by the most recent ESMO and NCCN guidelines, local ablative therapy (LAT) should be considered for patients with oligoprogressive disease (OPD) [

55,

56]. This strategy enables targeted control of limited sites of progression, allowing continued benefit from the ongoing systemic therapy and offering a potential survival advantage without compromising the patient's overall treatment plan.

4.2. Definition of Oligo-PD

The frequency of Oligo-PD during EGFR-TKI treatment has been suggested to be 15%–47% [

48]. In clinical trials of Oligo-PD in previously treated NSCLC, the criteria for the number of metastases varied from trial to trial. However, no common criteria have yet been established. The consensus definition of Oligo-PD generally assumes that patients exclusively have progressive disease (up to two or five lesions) with slower tumor biological features. The American Radium Society (ARS) recently proposed a criterion of 1-3 progressive lesions for Oligo-PD in NSCLC.

In advanced NSCLC patients with

EGFR mutations, LAT for Oligo-PD after EGFR-TKI therapy may eradicate the lesions, including resistant clones [

57,

58,

59]. A metastasis-directed treatment approach may prolong the duration of targeted therapy and delay the transition to the next systemic therapy as long as possible, thereby achieving the maximum longevity of TKI efficacy and contributing to prolonged survival. Advancements in radiotherapy have contributed to new treatment strategies for

EGFR-mutated NSCLC with Oligo-PD owing to the availability of stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT), an advanced radiotherapy modality with high local tumor control rates.

4.3. Current Status of Clinical Trials for Oligo-PD

A recent randomized phase II trial examined the effectiveness of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) of progressive lesions in patients with metastatic NSCLC and breast cancer with oligo-OD. The results of that study showed that SBRT could be beneficial for NSCLC patients with Oligo-PD (median PFS: 10.6 months in the SBRT group vs. 2.1 months in the salvage-chemotherapy group,

P = 0.004) [

60].

Other previous studies on Oligo-PD after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment in patients with NSCLC have also not identified the benefits of LAT for patients with Oligo-PD [

61,

62]. However, these studies included heterogeneous populations in terms of pretreatment systemic therapy, including molecular-targeted therapy as well as immune checkpoint inhibitors, and the numbers of treatment sequences. The frequency of Oligo-PD in EGFR-mutant NSCLC after treatment with first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs has previously been shown to be 15-45%, while the frequency of Oligo-PD after osimertinib has been reported to be 73-75%.

The frequency of Oligo-PD in patients with advanced NSLC after treatment with ICI has been described to be approximately 20 to 30 percent. Furthermore, the frequency of Oligo-PD after a therapeutic response to ICI was 56%. Oligo-PD may be more frequent with more effective treatment.

4.4. Ongoing Trials for Oligo-PD

Information regarding the ongoing clinical trials for patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC with Oligo-PD are shown in

Table 3. A single-arm phase II trial is ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of furmonertinib, a third-generation EGFR-TKI, combined with radiotherapy for

EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with Oligo-PD (NCT04970693). Additionally, two single arm phase II trials (NCT02759835, NCT04216121) are ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of osimertinib combined with LAT in patients with

EGFR-mutated Oligo-PD NSCLC. The results of these prospective trials will help establish a multidisciplinary treatment regimen for

EGFR-mutated NSCLC with Oligo-PD.

5. Local Ablative Therapy

The mainstay of LAT for oligometastatic NSCLC has been recently shifted to RT, in particular SBRT. The role of RT in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC has historically been limited to palliative purposes [

63]. Conventional low-dose RT has been shown to be effective in palliating symptoms associated with metastases at different sites of the body. Conventional irradiation has provided symptomatic relief, yet irradiated tumours often re-expand after some time and have not contributed to long-term local control or prolonged survival [

64].

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a new technique of radiation therapy that delivers a precise dose to the target tumor in several doses equal to or greater than conventional radical radiotherapy, is relatively safe, and provides a high degree of local control of lesions within the field of radiation [

65]. Furthermore, the cytological mechanism of the therapeutic effect of SBRT has been shown to result not only in direct cytotoxicity, as well as microvascular damage and endothelial apoptosis leading to the death of perfused tissue [

66]. SBRT has been the predominant type of LAT in the majority of clinical trials for the treatment of oligometastatic, oligo-residual and oligo-progressive disease.

5.1. Primary Site and Lung Metastases

Surgery has traditionally been the mainstay of LAT for chest lesions such as primary tumours and lung metastases in patients with Oligometastatic NSCLC. Surgery for primary tumours or lung metastases in patients with oligometastatic NSCLC has been shown to contribute to long-term survival since the concept of oligometastatic disease was introduced. Currently, in highly selected cohorts of patients with oligometastatic NSCLC, pulmonary resection still has the potential to contribute to long-term survival and local control.

Dramatic advances in radiation techniques have led to the advent of high-dose radiotherapy, including SBRT which now dominate LAT for primary and lung metastases in patients with oligometastatic NSCLC [

64]. A recent observational study evaluating the efficacy of SBRT for primary site or lung metastases in patients with oligometastatic NSCLC has demonstrated 2-year local control rates of 88.9% and no grade 4 pulmonary toxicity [

67]. Furthermore, a retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of SBRT for lung metastases in 140 patients with oligometastatic solid tumors showed 2-year local control rates of 85.1% with only 1.7% grade 2 pulmonary toxicity [

68]. Due to the favorable local control and safety of SBRT to lung lesions, SBRT has been the mainstay of treatment in most of the previous and ongoing clinical trials in Oligometastatic NSCLC.

A recent randomised phase III clinical trial (Northern Radiation Oncology Group of China-002) evaluated the efficacy and safety of first-line thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) combined with EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in patients with oligo-organ metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring EGFR mutations, compared with TKI monotherapy.

The combination of TKI plus TRT significantly improved survival, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 17.1 months versus 10.6 months in the TKI alone group (HR 0.57; P = .004) and a median overall survival (OS) of 34.4 months versus 26.2 months (HR 0.62; P = .029).

In terms of safety, the TKI plus TRT group experienced higher rates of serious adverse events, including radiation esophagitis (6.8%), radiation pneumonitis (5.1%) and leukopenia or neutropenia (3.4%), all of which were significantly more common than in the TKI monotherapy group [

69].

5.2. Brain Metastases

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has been widely performed for a few brain metastases, replacing the previously widely performed whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT), due to fewer neurocognitive side effects [

70]. In a phase III trial comparing stereotactic radiotherapy alone with stereotactic radiotherapy plus WBRT for patients with four or fewer metastatic brain tumours, median overall survival was 8 months in the stereotactic radiotherapy alone group and 7.5 months in the stereotactic radiotherapy plus WBRT group, with no significant difference [

71].

Furthermore, phase III trial comparing the treatment efficacy of WBRT+SRS versus WBRT alone in solid tumours patients with 1-3 brain metastases revealed prolonged survival benefit in the WBRT+SRS group (median OS 6.5 vs 4.9 months,

p = 0.0393) [

72]. Based on the results of several studies, SRS for brain metastases has been performed in most clinical trials for Oligometastatic NSCLC, resulting in favourable local control [

12,

73,

74].

5.3. Adrenal Gland Metastases

The advent of SBRT in radiation oncology has provided a promising option for the local treatment of adrenal gland metastases [

75]. SBRT has been widely applied as a local treatment for adrenal gland metastases in NSCLC with oligometastatic disease or Oligo-PD, with favorable local control achieved [

60,

76,

77,

78]. In addition, side effects of SBRT for adrenal metastases have been shown to be rare, minimal and well managed [

79,

80]. As an alternative to SBRT, high-dose conventional radiation has been applied for adrenal grand metastases, such as 60 Gy / 30 Fr or 45 Gy / 15 Fr, which has resulted in a favorable local control [

13,

36,

81].

5.4. Bone Metastases

Bone metastases are often associated with pain, as well as fractures, spinal cord compression and hypercalcemia, which can significantly reduce the physical and functional quality of life. Conventionally, low-dose irradiation has been predominantly applied for the prevention or palliation of skeletal-related adverse events (SREs) associated with bone metastases. Furthermore, the most effective treatment for palliation for pain due to bone metastases from solid tumors has been shown to be radiotherapy, including single and multiple fractions [

82,

83]. SBRT is a new option for radiotherapy of bone metastases and has been shown to improve local control and pain relief in patients with spinal metastases [

84].

Most clinical trials in patients with oligometastatic solid tumors have applied SBRT as spinal cord irradiation and have shown high local control rates of 75-95% [

85,

86,

87]. Recent phase II/III trials have shown that the risk of local failure and re-irradiation for spinal cord metastases has been lower with SBRT than with conventional radiation therapy [

88].

Previous study of 106 solid tumors with non-spine bone metastases revealed a favorable 2-year local control rate of approximately 85% for stereotactic radiotherapy for non-spine bone metastases [

89]. In addition, a recent randomized phase II trial comparing conventional radiotherapy and SBRT for bone metastases in non-spinal bone metastases showed 24-month local control rates of 100% in the SBRT group, which was significantly better than the conventional radiotherapy group (

P = 0.02) [

90].

5.5. Liver Metastases

Several retrospective studies have evaluated the efficacy of SBRT for liver metastases and have shown favorable 3-year local control of 70-90% [

91,

92,

93]. In a recent large registry study, SBRT for liver metastases showed favorable local control, 87% at 1 year and 68%t at 3 years. In addition, the incidence of grade 3 or higher toxicity was 3.9% in the study, indicating that the safety of SBRT for liver metastases seems to be ensured [

94].

5. Summary

The multidisciplinary treatment strategy for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC and the appropriate timing of LAT in combination with EGFR-TKIs for patients with oligometastatic, oligo-residual, and Oligo-PD. The findings indicate that LAT can be considered not only before EGFR-TKI treatment, but also during EGFR-TKI treatment and even after EGFR-TKI failure, depending on the oligo status of the patient (oligometastatic disease, oligo-residual disease, or Oligo-PD).

A recent phase III trial showed better survival with additional LAT, indicating that LAT could be considered for the treatment of synchronous oligometastatic disease in patients with

EGFR-mutated NSCLC [

33,

39]. Synchronous Oligometastatic disease may be rare accounting for only 6% of patients with advanced

EGFR-mutated NSCLC [

15], while oligo-residual disease accounts for approximately 30% of

EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients. Even if patients have poly-metastatic disease at the start of the initial therapy and if they have oligo-residual disease after 3-6 months of EGFR-TKI treatment, LAT for residual disease could be considered.

Oligometastatic disease or oligo-residual disease represents a state prior to resistance to EGFR-TKI treatment, whereas Oligo-PD represents a state after resistance to EGFR-TKI treatment and may be a different clinical entity. Oligometastatic disease, oligo-residual disease, or poly-metastatic disease can potentially develop into Oligo-PD after treatment with EGFR-TKIs or LAT. To avoid the potential loss of additional LAT, Oligo-PD should be reviewed in patients of progressive disease during EGFR-TKI treatment regardless of previous treatment. Meanwhile, the criteria for oligometastatic, oligo-residual, and Oligo-PD in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC have not been adequately established, and it is necessary to establish globally common criteria to stimulate therapeutic development. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the addition of LAT to EGFR-TKI treatment confers a survival benefit for both oligometastatic disease, oligo-residual disease, and Oligo-PD. Several ongoing clinical trials should address these issues and establish LAT as a standard treatment for all oligo-diseases in the foreseeable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing original draft preparation, TM; review and editing, TS.; supervision, NS and KT; All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Miyawaki reports personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., personal fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca K.K., personal fees from Taiho Pharma, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kenmotsu reports grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Eli Lilly K.K, personal fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Novartis Pharma K.K., grants and personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca K.K., personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Taiho Pharma, outside the submitted work. Dr. Ko reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Lilly, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kazuhisa Takahashi received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca K.K., Pfizer Japan, Inc., Eli Lilly K.K., MSD, and Boehringer Ingelheim and grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Japan K.K., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., and Novartis Pharma K.K., which are not related to the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest that could be positively or negatively influenced by the content of this article.

References

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2010; 11 (2): 121-128. [CrossRef]

- Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2012; 13 (3): 239-246. [CrossRef]

- Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K et al. Gefitinib or Chemotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Mutated EGFR. New England Journal of Medicine 2010; 362 (25): 2380-2388. [CrossRef]

- Soria J-C, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2017; 378 (2): 113-125.

- Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2020; 382 (1): 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Cho BC, Lu S, Felip E et al. Amivantamab plus Lazertinib in Previously Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2024; 391 (16): 1486-1498. [CrossRef]

- Planchard D, Jänne PA, Cheng Y et al. Osimertinib with or without Chemotherapy in EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2023; 389 (21): 1935-1948. [CrossRef]

- Schmid S, Li JJN, Leighl NB. Mechanisms of osimertinib resistance and emerging treatment options. Lung Cancer 2020; 147: 123-129. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi H, Nadal E, Gray JE et al. Overall Treatment Strategy for Patients With Metastatic NSCLC With Activating EGFR Mutations. Clin Lung Cancer 2022; 23 (1): e69-e82. [CrossRef]

- Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13 (1): 8-10.

- Guckenberger M, Lievens Y, Bouma AB et al. Characterisation and classification of oligometastatic disease: a European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendation. The Lancet Oncology 2020; 21 (1): e18-e28. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE et al. Consolidative Radiotherapy for Limited Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4 (1): e173501.

- Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J et al. Local Consolidative Therapy Vs. Maintenance Therapy or Observation for Patients With Oligometastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Long-Term Results of a Multi-Institutional, Phase II, Randomized Study. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37 (18): 1558-1565.

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of Oligometastatic Cancers: Long-Term Results of the SABR-COMET Phase II Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38 (25): 2830-2838. [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki T, Kenmotsu H, Kodama H et al. Association between oligo-residual disease and patterns of failure during EGFR-TKI treatment in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2021; 21 (1): 1247. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CJ, Yang JT, Guttmann DM et al. Final Analysis of Consolidative Use of Radiotherapy to Block (CURB) Oligoprogression Trial - A Randomized Study of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive Metastatic Lung and Breast Cancers. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2022; 114 (5): 1061. [CrossRef]

- Rusthoven KE, Hammerman SF, Kavanagh BD et al. Is there a role for consolidative stereotactic body radiation therapy following first-line systemic therapy for metastatic lung cancer? A patterns-of-failure analysis. Acta Oncol 2009; 48 (4): 578-583. [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki T, Wakuda K, Kenmotsu H et al. Proposing synchronous oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer based on progression after first-line systemic therapy. Cancer Sci 2020. [CrossRef]

- Al-Halabi H, Sayegh K, Digamurthy SR et al. Pattern of Failure Analysis in Metastatic EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancer Treated with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors to Identify Candidates for Consolidation Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10 (11): 1601-1607.

- Li XY, Zhu XR, Zhang CC et al. Analysis of Progression Patterns and Failure Sites of Patients With Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma With EGFR Mutations Receiving First-line Treatment of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Clin Lung Cancer 2020; 21 (6): 534-544. [CrossRef]

- Patel SH, Rimner A, Foster A et al. Patterns of initial and intracranial failure in metastatic EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib. Lung Cancer 2017; 108: 109-114. [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki T, Wakuda K, Kenmotsu H et al. Proposing synchronous oligometastatic non–small-cell lung cancer based on progression after first-line systemic therapy. Cancer Science 2021; 112 (1): 359-368.

- Gobbini E, Bertolaccini L, Giaj-Levra N et al. Epidemiology of oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer: results from a systematic review and pooled analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2021; 10 (7): 3339-3350. [CrossRef]

- Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer☆. Annals of Oncology 2021; 32 (12): 1475-1495.

- Levy A, Hendriks LEL, Berghmans T et al. EORTC Lung Cancer Group survey on the definition of NSCLC synchronous oligometastatic disease. Eur J Cancer 2019; 122: 109-114. [CrossRef]

- Dingemans AC, Hendriks LEL, Berghmans T et al. Definition of Synchronous Oligometastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer-A Consensus Report. J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14 (12): 2109-2119. [CrossRef]

- Conibear J, Chia B, Ngai Y et al. Study protocol for the SARON trial: a multicentre, randomised controlled phase III trial comparing the addition of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy and radical radiotherapy with standard chemotherapy alone for oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ Open 2018; 8 (4): e020690. [CrossRef]

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of 4–10 oligometastatic tumors (SABR-COMET-10): study protocol for a randomized phase III trial. BMC Cancer 2019; 19 (1): 816. [CrossRef]

- Tibdewal A, Agarwal JP, Srinivasan S et al. Standard maintenance therapy versus local consolidative radiation therapy and standard maintenance therapy in 1-5 sites of oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a study protocol of phase III randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2021; 11 (3): e043628. [CrossRef]

- Garon EB, Peterson P, Rizzo MT, Kim JS. Overall Survival and Safety With Pemetrexed/Platinum ± Anti-VEGF Followed by Pemetrexed ± Anti-VEGF Maintenance in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 4 Randomized Studies. Clin Lung Cancer 2022; 23 (3): 253-263. [CrossRef]

- Dingemans A-MC, Hendriks LEL, Berghmans T et al. Definition of Synchronous Oligometastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer—A Consensus Report. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2019; 14 (12): 2109-2119.

- Levy A, Hendriks LEL, Berghmans T et al. EORTC Lung Cancer Group survey on the definition of NSCLC synchronous oligometastatic disease. Eur J Cancer 2019; 122: 109-114. [CrossRef]

- Wang XS, Bai YF, Verma V et al. Randomized Trial of First-Line Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor With or Without Radiotherapy for Synchronous Oligometastatic EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2023; 115 (6): 742-748. [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Zhou F, Liu H et al. Consolidative Local Ablative Therapy Improves the Survival of Patients With Synchronous Oligometastatic NSCLC Harboring EGFR Activating Mutation Treated With First-Line EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol 2018; 13 (9): 1383-1392. [CrossRef]

- Gomez DR, Blumenschein GR, Lee JJ et al. Local consolidative therapy versus maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer without progression after first-line systemic therapy: a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology 2016; 17 (12): 1672-1682. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE et al. Consolidative Radiotherapy for Limited Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology 2018; 4 (1): e173501-e173501.

- Schuler A, Huser J, Schmid S et al. Patterns of progression on first line osimertinib in patients with EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A Swiss cohort study. Lung Cancer 2024; 187: 107427. [CrossRef]

- Wang X-S, Bai Y-F, Verma V et al. Randomized Trial of First-Line Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor With or Without Radiotherapy for Synchronous Oligometastatic EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Li M, Huang W et al. Thoracic Radiotherapy Improves the Survival in Patients With EGFR-Mutated Oligo-Organ Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol 2025; 43 (4): 412-421.

- Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 378 (2): 113-125. [CrossRef]

- Haratake N, Shimokawa M, Seto T et al. Survival benefit of using pemetrexed for EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in a randomized phase III study comparing gefitinib to cisplatin plus docetaxel (WJTOG3405). Int J Clin Oncol 2022; 27 (9): 1404-1412. [CrossRef]

- Lee DH, Lee J-S, Fan Y et al. Pemetrexed and platinum with or without pembrolizumab for tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-resistant, EGFR-mutant, metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: Phase 3 KEYNOTE-789 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023; 41 (17_suppl): LBA9000-LBA9000. [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018; 15 (2): 81-94. [CrossRef]

- Chan OSH, Lam KC, Li JYC et al. ATOM: A phase II study to assess efficacy of preemptive local ablative therapy to residual oligometastases of NSCLC after EGFR TKI. Lung Cancer 2020; 142: 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Elamin YY, Gomez DR, Antonoff MB et al. Local Consolidation Therapy (LCT) After First Line Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) for Patients With EGFR Mutant Metastatic Non-small-cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Clin Lung Cancer 2019; 20 (1): 43-47. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Koom WS, Byun HK et al. Metastasis-Directed Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive or Oligopersistent Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2022; 21 (2): e78-e86. [CrossRef]

- Doebele RC, Pilling AB, Aisner DL et al. Mechanisms of resistance to crizotinib in patients with ALK gene rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18 (5): 1472-1482. [CrossRef]

- Amini A, Verma V, Simone CB, 2nd et al. American Radium Society Appropriate Use Criteria for Radiation Therapy in Oligometastatic or Oligoprogressive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022; 112 (2): 361-375.

- Gettinger SN, Wurtz A, Goldberg SB et al. Clinical Features and Management of Acquired Resistance to PD-1 Axis Inhibitors in 26 Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018; 13 (6): 831-839. [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Memon D et al. Acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in NSCLC. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020; 38 (15_suppl): 9621-9621.

- Bozzetti C, Tiseo M, Lagrasta C et al. Comparison between epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene expression in primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and in fine-needle aspirates from distant metastatic sites. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3 (1): 18-22. [CrossRef]

- Suda K, Murakami I, Yu H et al. Heterogeneity of EGFR Aberrations and Correlation with Histological Structures: Analyses of Therapy-Naive Isogenic Lung Cancer Lesions with EGFR Mutation. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11 (10): 1711-1717. [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. New England Journal of Medicine 2019; 382 (1): 41-50.

- Schuler A, Huser J, Schaer S et al. 365P Patterns of progression on first-line osimertinib in patients with EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A Swiss cohort study. Annals of Oncology 2022; 33: S1584-S1585. [CrossRef]

- Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018; 29 (Suppl 4): iv192-iv237. [CrossRef]

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023; 21 (4): 340-350.

- Basler L, Kroeze SG, Guckenberger M. SBRT for oligoprogressive oncogene addicted NSCLC. Lung Cancer 2017; 106: 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM et al. Local ablative therapy of oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7 (12): 1807-1814. [CrossRef]

- Shukuya T, Takahashi T, Naito T et al. Continuous EGFR-TKI administration following radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients with isolated CNS failure. Lung Cancer 2011; 74 (3): 457-461. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CJ, Yang JT, Guttmann DM et al. Consolidative Use of Radiotherapy to Block (CURB) Oligoprogression ― Interim Analysis of the First Randomized Study of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Patients With Oligoprogressive Metastatic Cancers of the Lung and Breast. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2021; 111 (5): 1325-1326. [CrossRef]

- Kagawa Y, Furuta H, Uemura T et al. Efficacy of local therapy for oligoprogressive disease after programmed cell death 1 blockade in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2020; 111 (12): 4442-4452. [CrossRef]

- Rheinheimer S, Heussel CP, Mayer P et al. Oligoprogressive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer under Treatment with PD-(L)1 Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12 (4). [CrossRef]

- Lutz S, Berk L, Chang E et al. Palliative Radiotherapy for Bone Metastases: An ASTRO Evidence-Based Guideline. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2011; 79 (4): 965-976.

- Baker S, Jiang W, Mou B et al. Progression-Free Survival and Local Control After SABR for up to 5 Oligometastases: An Analysis From the Population-Based Phase 2 SABR-5 Trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022; 114 (4): 617-626. [CrossRef]

- Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: can SBRT be comparable to surgery? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 81 (5): 1352-1358.

- Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. Engaging the vascular component of the tumor response. Cancer Cell 2005; 8 (2): 89-91. [CrossRef]

- De Rose F, Cozzi L, Navarria P et al. Clinical Outcome of Stereotactic Ablative Body Radiotherapy for Lung Metastatic Lesions in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Oligometastatic Patients. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016; 28 (1): 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Virbel G, Cox DG, Olland A et al. Outcome of lung oligometastatic patients treated with stereotactic body irradiation. Front Oncol 2022; 12: 945189. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Li M, Huang W et al. Thoracic Radiotherapy Improves the Survival in Patients With EGFR-Mutated Oligo-Organ Metastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled, Phase III Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2025; 43 (4): 412-421.

- Muacevic A, Wowra B, Siefert A et al. Microsurgery plus whole brain irradiation versus Gamma Knife surgery alone for treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized controlled multicentre phase III trial. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 2008; 87 (3): 299-307. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006; 295 (21): 2483-2491.

- Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet 2004; 363 (9422): 1665-1672. [CrossRef]

- Collen C, Christian N, Schallier D et al. Phase II study of stereotactic body radiotherapy to primary tumor and metastatic locations in oligometastatic nonsmall-cell lung cancer patients. Annals of Oncology 2014; 25 (10): 1954-1959. [CrossRef]

- De Ruysscher D, Wanders R, van Baardwijk A et al. Radical Treatment of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients with Synchronous Oligometastases: Long-Term Results of a Prospective Phase II Trial (Nct01282450). Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2012; 7 (10): 1547-1555. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Zhu X, Zhuang H et al. Clinical efficacy of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) for adrenal gland metastases: A multi-center retrospective study from China. Scientific Reports 2020; 10 (1): 7836. [CrossRef]

- Plichta K, Camden N, Furqan M et al. SBRT to adrenal metastases provides high local control with minimal toxicity. Adv Radiat Oncol 2017; 2 (4): 581-587. [CrossRef]

- Rudra S, Malik R, Ranck MC et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for curative treatment of adrenal metastases. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2013; 12 (3): 217-224. [CrossRef]

- Casamassima F, Livi L, Masciullo S et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy for adrenal gland metastases: university of Florence experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 82 (2): 919-923. [CrossRef]

- Franzese C, Franceschini D, Cozzi L et al. Minimally Invasive Stereotactical Radio-ablation of Adrenal Metastases as an Alternative to Surgery. Cancer Res Treat 2017; 49 (1): 20-28. [CrossRef]

- Voglhuber T, Kessel KA, Oechsner M et al. Single-institutional outcome-analysis of low-dose stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) of adrenal gland metastases. BMC Cancer 2020; 20 (1): 536. [CrossRef]

- Oshiro Y, Takeda Y, Hirano S et al. Role of radiotherapy for local control of asymptomatic adrenal metastasis from lung cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2011; 34 (3): 249-253. [CrossRef]

- Chow E, van der Linden YM, Roos D et al. Single versus multiple fractions of repeat radiation for painful bone metastases: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15 (2): 164-171.

- McDonald R, Ding K, Brundage M et al. Effect of Radiotherapy on Painful Bone Metastases: A Secondary Analysis of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group Symptom Control Trial SC.23. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3 (7): 953-959.

- Sprave T, Verma V, Förster R et al. Randomized phase II trial evaluating pain response in patients with spinal metastases following stereotactic body radiotherapy versus three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2018; 128 (2): 274-282. [CrossRef]

- Bishop AJ, Tao R, Rebueno NC et al. Outcomes for Spine Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy and an Analysis of Predictors of Local Recurrence. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015; 92 (5): 1016-1026. [CrossRef]

- Tseng CL, Soliman H, Myrehaug S et al. Imaging-Based Outcomes for 24 Gy in 2 Daily Fractions for Patients with de Novo Spinal Metastases Treated With Spine Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018; 102 (3): 499-507. [CrossRef]

- Wang XS, Rhines LD, Shiu AS et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for management of spinal metastases in patients without spinal cord compression: a phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13 (4): 395-402. [CrossRef]

- Zeng KL, Myrehaug S, Soliman H et al. Mature Local Control and Reirradiation Rates Comparing Spine Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy With Conventional Palliative External Beam Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022; 114 (2): 293-300. [CrossRef]

- Erler D, Brotherston D, Sahgal A et al. Local control and fracture risk following stereotactic body radiation therapy for non-spine bone metastases. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2018; 127 (2): 304-309. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen QN, Chun SG, Chow E et al. Single-Fraction Stereotactic vs Conventional Multifraction Radiotherapy for Pain Relief in Patients With Predominantly Nonspine Bone Metastases: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial. JAMA Oncol 2019; 5 (6): 872-878.

- Clerici E, Comito T, Franzese C et al. Role of stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of liver metastases: clinical results and prognostic factors. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 2020; 196 (4): 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Goodman BD, Mannina EM, Althouse SK et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiation therapy for hepatic oligometastases. Practical Radiation Oncology 2016; 6 (2): 86-95. [CrossRef]

- Méndez Romero A, Keskin-Cambay F, van Os RM et al. Institutional experience in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Reports of Practical Oncology & Radiotherapy 2017; 22 (2): 126-131.

- Méndez Romero A, Schillemans W, van Os R et al. The Dutch-Belgian Registry of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Liver Metastases: Clinical Outcomes of 515 Patients and 668 Metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021; 109 (5): 1377-1386.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).