Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Results

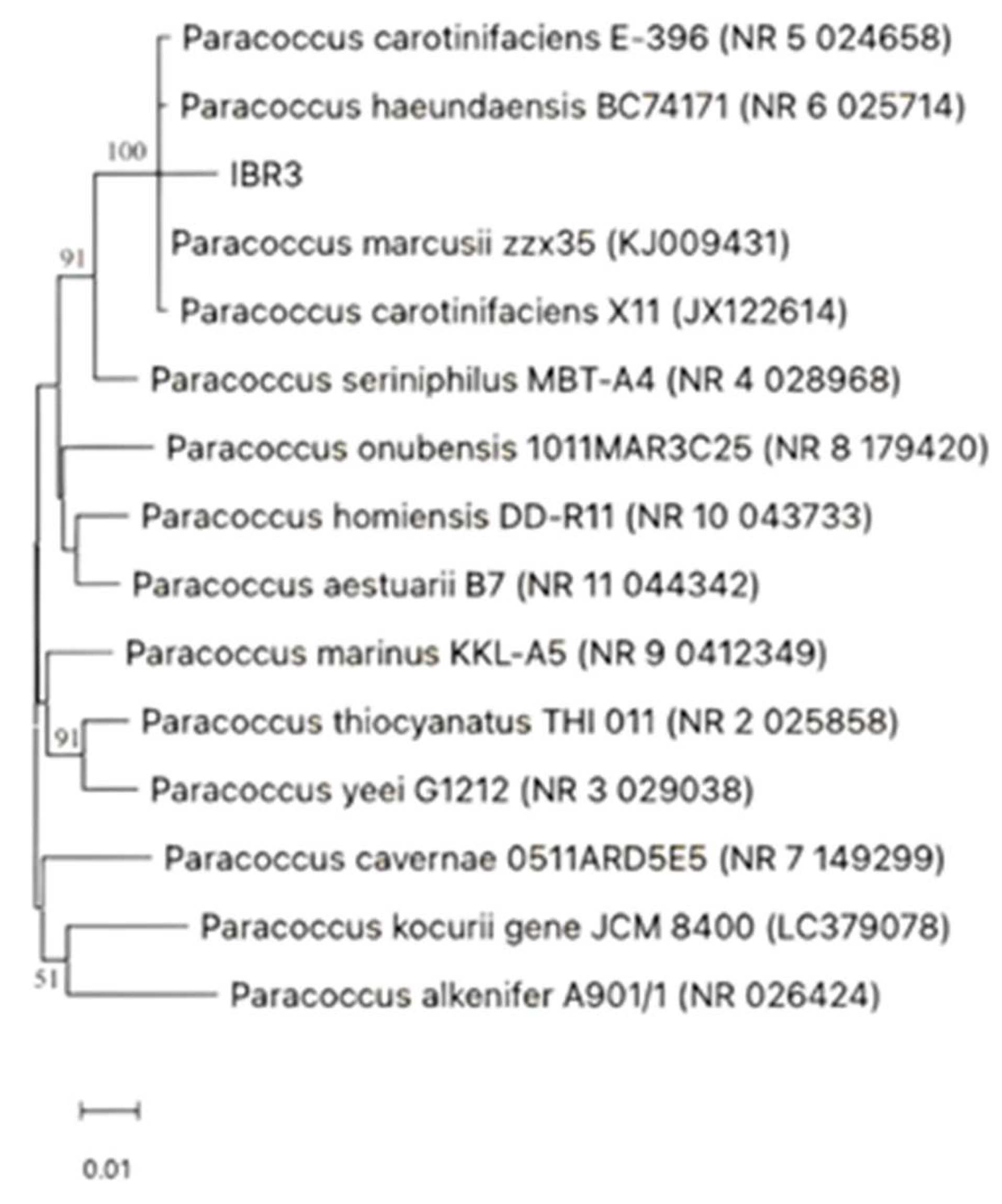

2.1. Identification and Characterization of the IBR3 Bacterial Strain

2.2. Chemical composition of Thymus serpyllum essential oil

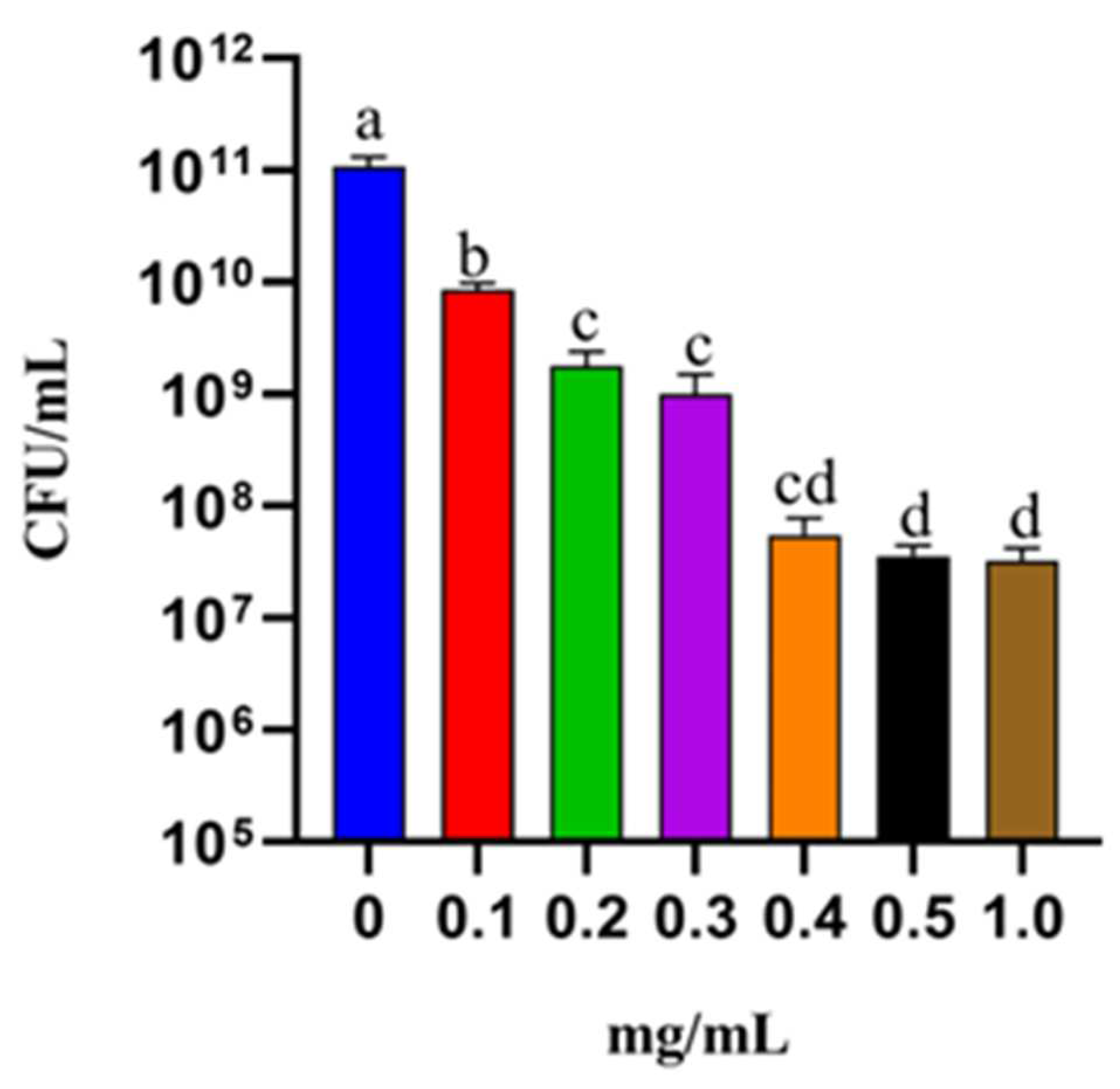

2.3. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Thymus serpyllum Essential Oil

2.4. Role of Paracoccus IBR3 in Mural Painting Deterioration

2.5. Cell Membrane Integrity

2.6. Crystal Violet Uptake Assay

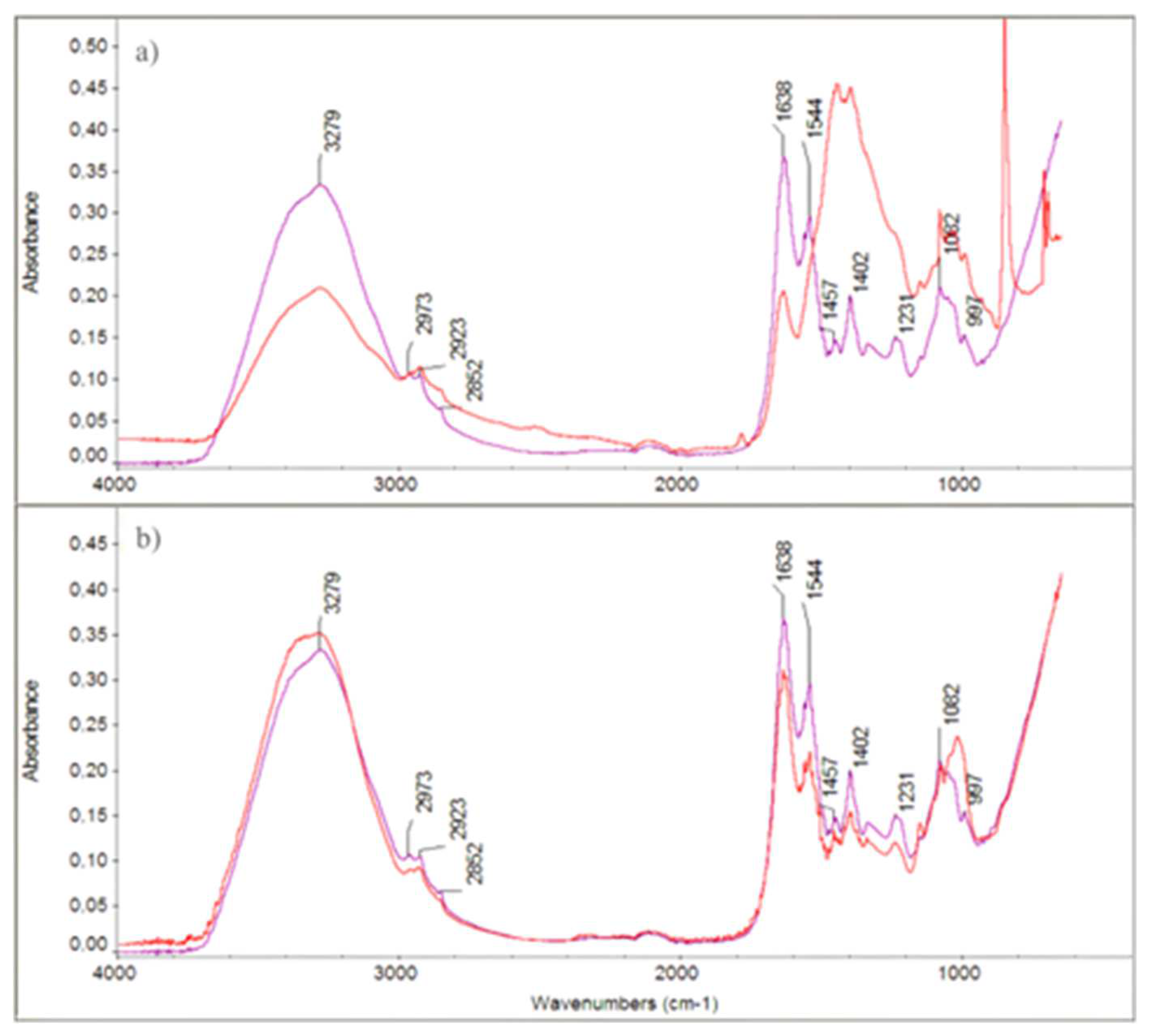

2.7. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy

3. Discussions

4. Material and methods

4.1. Isolation and Characterization of a Bacterial Strain

4.2. Molecular Identification

4.3. Essential Oil of Thymus serpyllum

4.4. Growth Inhibition Assays

4.5. Membrane Integrity of IBR3

4.6. Crystal Violet Assay for IBR3 Membrane Permeability

4.7. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy

4.8. Role of Paracoccus in Mural Painting Deterioration

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

References

- Suphaphimol, N.; Suwannarach, N.; Purahong, W.; Jaikang, C.; Pengpat, K.; Semakul, N.; Yimklan, S.; Jongjitngam, S.; Jindasu, S.; Thiangtham, S.; et al. Identification of Microorganisms Dwelling on the 19th Century Lanna Mural Paintings from Northern Thailand Using Culture-Dependent and -Independent Approaches. Biology 2022, 11, 228. [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Wu, F.; Chen, Y.; Ma, W.; He, D.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, J.-D.; Wang, W.; Tian, T.; Feng, H. Mechanisms of Lead-Containing Pigment Discoloration Caused by Naumannella Cuiyingiana AFT2T Isolated from 1500 Years Tomb Wall Painting of China. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2023, 185, 105689. [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Wu, F.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.-D.; Duan, Y.; Xu, R.; Feng, H.; Wang, W.; Li, S.-W. Insights into the Bacterial and Fungal Communities and Microbiome That Causes a Microbe Outbreak on Ancient Wall Paintings in the Maijishan Grottoes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 163, 105250. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L. Caves and Other Low-Light Environments: Aerophitic Photoautotrophic Microorganisms. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology; Bitton, G., Ed.; Wiley, 2003 ISBN 978-0-471-35450-5.

- Gonzalez, I.; Laiz, L.; Hermosin, B.; Caballero, B.; Incerti, C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Bacteria Isolated from Rock Art Paintings: The Case of Atlanterra Shelter (South Spain). J. Microbiol. Methods 1999, 36, 123–127. [CrossRef]

- Pavić, A.; Ilić-Tomić, T.; Pačevski, A.; Nedeljković, T.; Vasiljević, B.; Morić, I. Diversity and Biodeteriorative Potential of Bacterial Isolates from Deteriorated Modern Combined-Technique Canvas Painting. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 97, 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Jimenez, I.G., C. Actinomycetes in Hypogean Environments. Geomicrobiol. J. 1999, 16, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gorbushina, A.A.; Heyrman, J.; Dornieden, T.; Gonzalez-Delvalle, M.; Krumbein, W.E.; Laiz, L.; Petersen, K.; Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Swings, J. Bacterial and Fungal Diversity and Biodeterioration Problems in Mural Painting Environments of St. Martins Church (Greene–Kreiensen, Germany). Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2004, 53, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Coppola, R.; Feo, V.D. Essential Oils and Antifungal Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 86. [CrossRef]

- Palla, F.; Bruno, M.; Mercurio, F.; Tantillo, A.; Rotolo, V. Essential Oils as Natural Biocides in Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Molecules 2020, 25, 730. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Badri, W.; Dumas, E.; Ghnimi, S.; Elaissari, A.; Saurel, R.; Gharsallaoui, A. Nanoencapsulation of Essential Oils as Natural Food Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5778. [CrossRef]

- Vettraino, A.M.; Zikeli, F.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Vinciguerra, V.; Tabet, D.; Romagnoli, M. Lignin Nanoparticles Containing Essential Oils for Controlling Phytophthora Cactorum Diseases. For. Pathol. 2022, 52, e12739. [CrossRef]

- Vettraino, A.M.; Zikeli, F.; Humar, M.; Biscontri, M.; Bergamasco, S.; Romagnoli, M. Essential Oils from Thymus Spp. as Natural Biocide against Common Brown- and White-Rot Fungi in Degradation of Wood Products: Antifungal Activity Evaluation by in Vitro and FTIR Analysis. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2023, 81, 747–763. [CrossRef]

- Zikeli, F.; Vettraino, A.M.; Biscontri, M.; Bergamasco, S.; Palocci, C.; Humar, M.; Romagnoli, M. Lignin Nanoparticles with Entrapped Thymus Spp. Essential Oils for the Control of Wood-Rot Fungi. Polymers 2023, 15, 2713. [CrossRef]

- Isola, D.; Capobianco, G.; Tovazzi, V.; Pelosi, C.; Trotta, O.; Serranti, S.; Lanteri, L.; Zucconi, L.; Spizzichino, V. Biopatinas on Peperino Stone: Three Eco-Friendly Methods for Their Control and Multi-Technique Approach to Evaluate Their Efficacy. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 375. [CrossRef]

- Corbu, V.M.; Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Marinas, I.C.; Avramescu, S.M.; Pecete, I.; Geanǎ, E.I.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Eco-Friendly Solution Based on Rosmarinus Officinalis Hydro-Alcoholic Extract to Prevent Biodeterioration of Cultural Heritage Objects and Buildings. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 11463. [CrossRef]

- Corbu, V.M.; Gheorghe, I.; Marinaș, I.C.; Geană, E.I.; Moza, M.I.; Csutak, O.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Demonstration of Allium Sativum Extract Inhibitory Effect on Biodeteriogenic Microbial Strain Growth, Biofilm Development, and Enzymatic and Organic Acid Production. Molecules 2021, 26, 7195. [CrossRef]

- Geweely, N.S.; Afifi, H.A.; Ibrahim, D.M.; Soliman, M.M. Efficacy of Essential Oils on Fungi Isolated from Archaeological Objects in Saqqara Excavation, Egypt. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019, 36, 148–168. [CrossRef]

- Senbua, W.; Wichitwechkarn, J. Molecular Identification of Fungi Colonizing Art Objects in Thailand and Their Growth Inhibition by Local Plant Extracts. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 356. [CrossRef]

- Albasil, M.D.; Mahgoub, G.; El Hagrassy, A.; Reyad, A.M. Evaluating the Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils in the Conservation of Mural Paintings. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. : 21 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Korayem, A.S.; Abu-Hussien, S.H.; Rashidy, W.B. Antifungal, Toxicological, and Colorimetric Properties of Origanum Vulgare, Moringa Oleifera, and Cinnamomum Verum Essential Oils Mixture against Egyptian Prince Yusuf Palace Deteriorative Fungi. BMC Biotechnol 2025, 25, 4. [CrossRef]

- Harker, M.; Hirschberg, J.; Oren, A. Paracoccus Marcusii Sp. Nov., an Orange Gram-Negative Coccus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48, 543–548. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Yan, Z.-F.; Lin, P.; Gao, W.; Yi, T.-H. Paracoccus Pueri Sp. Nov., Isolated from Pu’er Tea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 1535–1542. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, T.-J.; Lee, W.J.; Kim, Y.T. Paracoccus Haeundaensis Sp. Nov., a Gram-Negative, Halophilic, Astaxanthin-Producing Bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1699–1702. [CrossRef]

- Tsubokura, A.; Yoneda, H.; Mizuta, H. Paracoccus Carotinifaciens Sp. Nov., a New Aerobic Gram-Negative Astaxanthin-Producing Bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1999, 49, 277–282. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Sheng, H.; Feng, H.; An, L. Paracoccus Tibetensis Sp. Nov., Isolated from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Permafrost. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1902–1905. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Moñino, I.; Jurado, V.; Hermosin, B.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Paracoccus Cavernae Sp. Nov., Isolated from a Show Cave. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 2265–2270. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Patricio, S.; Gonzalez-Pimentel, J.L.; Miller, A.Z.; Hermosin, B.; Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Jurado, V. Paracoccus Onubensis Sp. Nov., a Novel Alphaproteobacterium Isolated from the Wall of a Show Cave. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2021, 71, 004942. [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Bajaj, A.; Singh, Y.; Lal, R. Harnessing Taxonomically Diverse and Metabolically Versatile Genus Paracoccus for Bioplastic Synthesis and Xenobiotic Biodegradation. J Appl Microbiol 2022, 132, 4208–4224. [CrossRef]

- Gomoiu, I.; Mohanu, D.; Radvan, R.; Dumbravician, M.; Neagu, S.E.; Cojoc, L.R.; Enache, M.I.; Chelmus, A.; Mohanu, I. Environmental Impact on Biopigmentation of Mural Painting. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2017, 131, 48–51. [CrossRef]

- Cojoc, L.R.; Enache, M.I.; Neagu, S.E.; Lungulescu, M.; Setnescu, R.; Ruginescu, R.; Gomoiu, I. Carotenoids Produced by Halophilic Bacterial Strains on Mural Paintings and Laboratory Conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, fnz243. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, Y.; Tian, T.; Xiang, T.; Liu, X.; Wu, F.; An, L.; Wang, W.; Gu, J.-D.; et al. The Community Distribution of Bacteria and Fungi on Ancient Wall Paintings of the Mogao Grottoes. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 7752. [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, K.; Puchalski, M.; Otlewska, A.; Wrzosek, H.; Guiamet, P.; Piotrowska, M.; Gutarowska, B. Microbial Diversity of Pre-Columbian Archaeological Textiles and the Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Misting Disinfection. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 23, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Saridaki, A.; Katsivela, E.; Glytsos, T.; Tsiamis, G.; Violaki, E.; Kaloutsakis, A.; Kalogerakis, N.; Lazaridis, M. Identification of Bacterial Communities on Different Surface Materials of Museum Artefacts Using High Throughput Sequencing. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 54, 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, J.; Puškárová, A.; Planý, M.; Farkas, Z.; Rusková, M.; Kvalová, K.; Kraková, L.; Bučková, M.; Pangallo, D. Colored Stains: Microbial Survey of Cellulose-Based and Lignin Rich Papers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124456. [CrossRef]

- Borrego, S.; Saravia, S.G.D.; Oderlaise Valdés; Isbel Vivar; Battistoni, P.; Guiamet, P. Biocidal activity of two essential oils on the fungal biodeterioration of historical documents. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2016, 7, 369-380. [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F.; Mollea, C.; Demichela, M.; Fissore, D. Application of Essential Oils to Control the Biodeteriogenic Microorganisms in Archives and Libraries. Heritage 2022, 5, 2181–2195. [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.; Palla, F. Plant Essential Oils as Biocides in Sustainable Strategies for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8522. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Paiva, D.S.; Pereira, E.; Rufino, A.C.; Landim, E.; Marques, M.P.; Cabral, C.; Portugal, A.; Mesquita, N. Evaluating the Antifungal Activity of Volatilized Essential Oils on Fungi Contaminating Artifacts from a Museum Collection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2378. [CrossRef]

- Lavin, P.; De Saravia, S.G.; Guiamet, P. Scopulariopsis Sp. and Fusarium Sp. in the Documentary Heritage: Evaluation of Their Biodeterioration Ability and Antifungal Effect of Two Essential Oils. Microb Ecol 2016, 71, 628–633. [CrossRef]

- Casiglia, S.; Bruno, M.; Scandolera, E.; Senatore, F.; Senatore, F. Influence of Harvesting Time on Composition of the Essential Oil of Thymus Capitatus (L.) Hoffmanns. & Link. Growing Wild in Northern Sicily and Its Activity on Microorganisms Affecting Historical Art Crafts. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 2704–2712. [CrossRef]

- Vaara, M.; Vaara, T. Outer Membrane Permeability Barrier Disruption by Polymyxin in Polymyxin-Susceptible and -Resistant Salmonella Typhimurium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1981, 19, 578–583. [CrossRef]

- Huleihel, M.; Pavlov, V.; Erukhimovitch, V. The Use of FTIR Microscopy for the Evaluation of Anti-Bacterial Agents Activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2009, 96, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Devi, K.P.; Nisha, S.A.; Sakthivel, R.; Pandian, S.K. Eugenol (an Essential Oil of Clove) Acts as an Antibacterial Agent against Salmonella Typhi by Disrupting the Cellular Membrane. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Di Rosario, M.; Continisio, L.; Mantova, G.; Carraturo, F.; Scaglione, E.; Sateriale, D.; Forgione, G.; Pagliuca, C.; Pagliarulo, C.; Colicchio, R.; et al. Thyme Essential Oil as a Potential Tool Against Common and Re-Emerging Foodborne Pathogens: Biocidal Effect on Bacterial Membrane Permeability. Microorganisms 2024, 13, 37. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B.-P.; Pei, R.-S.; Xu, N. The Antibacterial Mechanism of Carvacrol and Thymol against Escherichia Coli. Lett Appl Microbiol 2008, 47, 174–179. [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Yusoff, K.; Lim, S.-H.E.; Chong, C.-M.; Lai, K.-S. Membrane Disruption Properties of Essential Oils—A Double-Edged Sword? Processes 2021, 9, 595. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mijalli, S.H.; El Hachlafi, N.; Jeddi, M.; Abdallah, E.M.; Assaggaf, H.; Qasem, A.; Lee, L.-H.; Law, J.W.-F.; Aladhadh, M.; Alnasser, S.M.; et al. Unveiling the Volatile Compounds and Antibacterial Mechanisms of Action of Cupressus Sempervirens L., against Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115609. [CrossRef]

- Kauser, S.; Raj, N.; Ahmedi, S.; Manzoor, N. Mechanistic Insight into the Membrane Disrupting Properties of Thymol in Candida Species. Microbe 2024, 2, 100045. [CrossRef]

- Coico, R. Gram Staining. CP Microbiol. 2006, 00. [CrossRef]

- Reller, L.B.; Mirrett, S. Motility-Indole-Lysine Medium for Presumptive Identification of Enteric Pathogens of Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 1975, 2, 247–252. [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, M.; Forchhammer, K. Carbon-Source-Dependent Nitrogen Regulation in Escherichia Coli Is Mediated through Glutamine-Dependent GlnB Signalling. Microbiology 2003, 149, 2163–2172. [CrossRef]

- Kraková, L.; Chovanová, K.; Selim, S.A.; Šimonovičová, A.; Puškarová, A.; Maková, A.; Pangallo, D. A Multiphasic Approach for Investigation of the Microbial Diversity and Its Biodegradative Abilities in Historical Paper and Parchment Documents. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 70, 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Dhawale, M.R.; Wilson, J.J.; Khachatourians, G.G.; Ingledew, W.M. Improved Method for Detection of Starch Hydrolysis. Appl Env. Microbiol 1982, 44, 747–750. [CrossRef]

- Cacchio, P.; Contento, R.; Ercole, C.; Cappuccio, G.; Martinez, M.P.; Lepidi, A. Involvement of Microorganisms in the Formation of Carbonate Speleothems in the Cervo Cave (L’Aquila-Italy). Geomicrobiol. J. 2004, 21, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Jurado, V.; Gonzalez-Pimentel, J.L.; Hermosin, B.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Biodeterioration of Salón de Reinos, Museo Nacional Del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8858. [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Yıldız, Z.; Aksöz, N.; Eninanç, A.B.; Dağ, İ.; Yıldız, A.; Doğan, H.H.; Yamaç, M. Flask and Reactor Scale Production of Plant Growth Regulators by Inonotus Hispidus: Optimization, Immobilization and Kinetic Parameters. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 53, 1210–1223. [CrossRef]

- Hussain Qadri, S.M.; Zubairi, S.; Hawley, H.P.; Mazlaghani, H.H.; Ramirez, E.G. Rapid Test for Determination of Urea Hydrolysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1984, 50, 417–423. [CrossRef]

- Woodman, M.E.; Savage, C.R.; Arnold, W.K.; Stevenson, B. Direct PCR of Intact Bacteria (Colony PCR). CP Microbiol. 2016, 42. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Schmid, M.; Rothballer, M.; Hause, G.; Zuccaro, A.; Imani, J.; Kämpfer, P.; Domann, E.; Schäfer, P.; Hartmann, A.; et al. Detection and Identification of Bacteria Intimately Associated with Fungi of the Order Sebacinales. Cell. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2235–2246. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences. J Mol Evol 1980, 16, 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [CrossRef]

- Finney, D.J. Statistical Logic in the Monitoring of Reactions to Therapeutic Drugs. Methods Inf Med 1971, 10, 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Du, R.; Zhao, F.; Xiao, H.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Z. The Mode of Action of Bacteriocin CHQS, a High Antibacterial Activity Bacteriocin Produced by Enterococcus Faecalis TG2. Food Control 2019, 96, 470–478. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Luo, M.; Fu, Y.; Zu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yao, L.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Y. Effect of Corilagin on Membrane Permeability of Escherichia Coli, Staphylococcus Aureus and Candida Albicans. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1517–1523. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Feng, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Zhang, L.; Shen, H.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; et al. Protocol for Bacterial Typing Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102223. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic |

Paracoccus IBR3 |

P. marcusii MH1T |

P. haeundaensis BC74171T |

P. carotinifaciens E-396T |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Cocci to short rods, 1.0 μm in size, growing in single, pairs or short chains. | Cocci to short rods, 1.0-1.3 μm in size, growing in single, pairs or short chains. | rod-shaped, | rod-shaped, |

| 0.3–0.7 μm in diameter and 0.8–2.5 μm in length. | 0.3-0.75 μm in diameter and 1.0-5.0 μm in length. | |||

| Motility | - | - | + | + |

| Orange to red pigment | + | + | + | + |

| Growth at 40 °C | - | - | - | - |

| Growth on: | ||||

| Sucrose | + | + | - | + |

| Fructose | + | + | - | + |

| D-Sorbitol | + | + | - | + |

| D-Glucose | + | + | - | + |

| L- Arabinose | + | + | + | - |

| D-Mannose | + | + | - | + |

| D-Mannitol | + | + | - | + |

| Production of: | ||||

| Urease | - | - | - | - |

| Indole from tryptophan | - | - | - | - |

| Organic acids from D-glucose | + | + | NR | + |

| Hidrolysis of: | ||||

| Starch | - | - | + | - |

| Gelatin | W | W | NR | - |

| +, Positive; -, negative; W, weakly positive; NR, not reported. | ||||

| Data for P. marcusii were obtained from Harker et al. [22] and Wang et al. [23], data for P. haeundaensis BC74171ᵀ were from Lee et al. [24] and data for P. carotinifaciens E-396ᵀ were from Tsubokura et al. [25]. | ||||

| Components | Relative concentration (%) |

Retention time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| α-Pinene | 0.82 | 15.082 |

| Fenchene | 0.34 | 15.889 |

| Camphene | 2.06 | 16.018 |

| trans-p-Menthane | 0.17 | 17.366 |

| β-Pinene | 0.71 | 17.443 |

| cis-p-Menthane | 0.22 | 18.104 |

| p-Cymene | 40.28 | 19.657 |

| p-Cymen-8-ol | 0.09 | 28.087 |

| Thymol | 2.45 | 32.980 |

| Carvacrol | 51.88 | 33.478 |

| Paracoccus strain | NCBI ID |

|---|---|

| P. carotinifaciens E-396 | NR 5 024658 |

| P. haeundaensis BC74171 | NR 6 025714 |

| P. marcusi zzx35 | KJ009431 |

| P. carotinifaciens X11 | JX122614 |

| P. seriniphylus MBT-A4 | NR 4 028968 |

| P. onubensis 1011MAR3C25 | NR 8 179420 |

| P. homiensis DD-R11 | NR 10 043733 |

| P. aestuarii B7 | NR 11 044342 |

| P. marinus KKL-A5 | NR 9 0412349 |

| P. thiocyanatus THI 011 | NR 2 025858 |

| P. yeei G1212 | NR 3 029038 |

| P. cavernae 0511ARD5E5 | NR 7 149299 |

| P. kocurii gene JCM 8400 | LC379078 |

| P. alkenifer A 901/1 | NR 026424 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).