1. Introduction

In an era of pervasive digital communication, chatting has become a fundamental social and psychological practice. Whether through WhatsApp, Messenger, Telegram, or in-app live chat features, online communication is not only an extension of human language but also a reflection of the user's cognitive and emotional states. As human interaction increasingly migrates to virtual platforms, understanding the psychological underpinnings of chatting behaviors becomes essential for both mental health research and communication science.

This study explores how moods and mental states shape chatting behaviors and vice versa. How do people communicate when they are anxious, euphoric, depressed, or angry? Does the act of chatting regulate emotion? What implications does this have for digital well-being and emotional literacy?

By adopting a multidisciplinary lens, this study critically engages with the interrelation of minds, moods, and digital chatting practices. It bridges gaps between digital humanities, clinical psychology, and media behavior analysis to better understand the cognitive-affective realities embedded in contemporary communication.

1.1. Background of the Study

In the current era of hyperconnectivity, digital communication has transcended its role as a utility and become an essential extension of human cognition, emotion, and behavior (Baym, 2015; Turkle, 2011). The proliferation of chatting platforms such as Messenger, WhatsApp, Telegram, and university-specific forums has transformed the way young adults in Bangladesh express their moods, form interpersonal relationships, and cope with stress. The pervasiveness of mobile technology, particularly among university students, has resulted in a growing body of sociological and psychological interest in the intersection between digital communication and emotional well-being (Choudhury et al., 2013; Sharma & Pal, 2020).

In Bangladesh, the digital divide has rapidly narrowed with increasing smartphone penetration and affordable mobile data packages (BTRC, 2023). University students, particularly those in urban areas, constitute one of the largest user groups of mobile-based chatting applications. These platforms now mediate their academic coordination, social belonging, romantic exploration, and emotional regulation. This age group—emerging adults aged 18–25—also represents a critical psychological phase marked by identity negotiation, social experimentation, and vulnerability to mood disorders (Arnett, 2000). Chatting behaviors in such populations, therefore, offer a digital lens through which broader psychosocial patterns may be interpreted.

1.2. Rationale and Significance

While global literature has acknowledged the emotional and psychological implications of social media use, there remains a dearth of context-specific research focusing on South Asian populations, particularly in Bangladesh. Furthermore, most existing studies generalize user behavior without adequate disaggregation across gender identities, emotional states, and platform-specific affordances. This research aims to bridge that gap by conducting a critical investigation into how chatting behavior correlates with moods and psychological states among male and female university students of Bangladesh.

In addition to exploring behavioral frequency and platform preferences, this study interrogates the emotive language, symbolic representation (e.g., emojis, memes), and mood-triggered impulsivity embedded within private and group chat environments. With increasing concerns regarding mental health on campuses—heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent digitalization of educational systems—this research aims to contribute empirically grounded insights to the academic discourse and inform digital well-being initiatives.

1.3. The Bangladesh Context

The sociocultural dynamics of Bangladesh provide a unique setting for studying chatting behaviors and mood. Despite being a traditionally conservative society, Bangladesh has undergone rapid urbanization, technological expansion, and demographic transition. Over 60% of the population is under 30, and internet penetration surpassed 75% in 2022 (BTRC, 2023). University students occupy a transitional zone between traditional expectations and digital modernity. As they oscillate between real-world academic stressors and online spaces of expression, their moods and identities are increasingly co-constructed through digital interactions.

Gender norms in Bangladesh further complicate the picture. Male students are often socialized to project emotional stoicism, while female students may face surveillance and reputational risks in digital spaces (Faisal & Rahman, 2021). These gendered performances often play out vividly in private chats, where emotional release, flirtation, aggression, or withdrawal may occur with less public scrutiny. The study, therefore, recognizes that chatting is not a neutral act but a culturally and emotionally loaded behavior shaped by social position, gender expectations, and mood regulation patterns.

1.4. Conceptualizing Mood and Chatting Behavior

Mood, as a transient and subjective emotional state, significantly affects communication behavior (Larsen & Diener, 1992). In the context of digital chats, mood manifests not just through words but through affective symbols, linguistic style, frequency of engagement, and timing of messages (Tov et al., 2013). Youth in emotionally heightened states often turn to messaging platforms for catharsis, validation, or distraction. Unlike structured social media posts, chats offer a relatively private, asynchronous, and interactive form of mood expression and emotional negotiation. In psychological literature, mood refers to a pervasive and sustained emotional state that colors an individual's perception of the world and responses to stimuli (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Moods differ from emotions in their duration, intensity, and lack of specific triggers. In contrast, chatting behaviors refer to the habitual patterns, linguistic styles, timing, content choices, and interactive tendencies demonstrated during digital text-based communication. The convergence of these domains—mood and chatting—suggests a dynamic interface where affective states both shape and are shaped by digital communication.

Research in affective computing and psycholinguistics has demonstrated that language can serve as a reliable marker of psychological states (Pennebaker, Mehl, & Niederhoffer, 2003). Chat-based interactions, which are often unfiltered and immediate, offer a rich data source for assessing mental well-being, emotional regulation, and behavioral tendencies. However, the micro-psychological implications of everyday chatting remain understudied, particularly in low-resource and culturally diverse contexts such as South Asia, where language, social norms, and digital access vary widely.

Previous research has explored the role of digital communication in mood regulation, particularly in Western contexts (Kross et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). However, less is known about how such dynamics unfold in collectivist, patriarchal, and academically competitive societies like Bangladesh. Do students use chats to cope with anxiety, depression, or loneliness? Are there gendered differences in the way negative moods are vented or suppressed through messaging apps? These questions demand empirical inquiry that combines psychological frameworks with sociocultural sensitivity.

1.5. Gender and Emotional Communication

Gender differences in emotional expression and communication behavior have long been established in psychological literature. Studies suggest that women are more likely to express sadness, anxiety, and affection, while men exhibit more anger or suppress emotional disclosure (Brody & Hall, 2008). In digital environments, these tendencies may become amplified or recalibrated depending on the level of anonymity, intimacy, and peer pressure. For example, women may prefer emoji-rich, empathetic conversations, while men may engage in humor or aggression-laced exchanges as a proxy for emotional connection.

In Bangladesh, these gendered scripts are both challenged and reinforced by the affordances of digital chatting platforms. Female students may find new freedoms for self-expression in encrypted apps, yet they also face moral judgment or threats of exposure. Male students, on the other hand, may perform masculinity through late-night group chats, meme wars, or romantic pursuits. This study, therefore, pays close attention to how chatting behavior is embedded within the cultural politics of gender performance and emotional coping.

1.6. Chatting as Psychological Outlet and Risk Factor

Digital chatting serves a dual role—it is both a psychological outlet and a behavioral risk factor. On the one hand, individuals use chatting to vent frustrations, express joy, seek validation, and gain emotional support. On the other, compulsive engagement in chatting—marked by habitual checking, inability to disengage, and emotional dependence on replies—has been increasingly associated with behavioral addiction (Andreassen et al., 2016).

The compulsive nature of chatting behaviors mirrors symptoms of digital addiction: salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (Griffiths, 2005). Young adults and adolescents, in particular, are susceptible due to their developmental need for social validation and identity formation (Twenge, 2017). Thus, the emotional and behavioral consequences of chatting demand critical inquiry into not just what people say in messages, but why, how, and how often they engage in such interactions.

1.7. Cultural and Regional Dimensions

While the bulk of research on digital communication has been concentrated in Western contexts, there is a growing need to investigate the phenomenon in non-Western, Global South, and multilingual environments. In South Asia—particularly in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan—chatting serves unique purposes shaped by linguistic plurality, social norms, class distinctions, and digital literacy. For instance, code-switching between English, Bangla, and Romanized scripts, as well as the use of regional emotive expressions, adds complexity to mood inference and behavioral interpretation.

Furthermore, social stigma around mental health in many Asian societies often inhibits face-to-face emotional expression, pushing individuals toward anonymous or semi-anonymous platforms like Telegram or WhatsApp groups where they can express vulnerabilities more freely (Mahmood, 2022). In such cases, chatting not only serves as emotional refuge but also becomes a form of digital resistance against traditional taboos around psychological discourse.

1.8. Chatting as Emotional Labor and Digital Intimacy

Drawing on Hochschild’s (1983) theory of emotional labor, chatting can be understood as a site where individuals regulate and display emotions to align with social expectations—whether to comfort a friend, maintain romantic rapport, or assert dominance. In the digital realm, such labor is often unacknowledged yet emotionally taxing. University students, especially those navigating multiple academic and relational pressures, may experience digital fatigue or emotional dissonance when chatting becomes obligatory rather than optional.

Simultaneously, chatting may function as a vehicle for digital intimacy. Through daily check-ins, voice notes, or even "seen" receipts, students maintain a sense of ambient co-presence (Baym, 2015). This can provide emotional support but also induce anxiety, particularly when expectations around responsiveness or message tone are misaligned. The oscillation between emotional reward and exhaustion forms a key area of investigation in this study.

1.9. Digital Disinhibition and Mood Instability

Suler’s (2004) theory of online disinhibition effect posits that digital environments lower social inhibitions, enabling individuals to express emotions they might suppress in face-to-face interactions. University students, particularly during episodes of sadness, anger, or excitement, may exhibit unfiltered chatting behaviors such as impulsive venting, cyber aggression, or risky disclosures. These behaviors, often fueled by mood volatility, can have cascading effects on academic performance, peer relationships, and psychological well-being. The digitization of emotional life is not without consequence. While chatting facilitates instant gratification, emotional catharsis, and connection, it also risks miscommunication, addiction, emotional exhaustion, and affective dissonance (Turkle, 2011). Moreover, users increasingly report feeling pressured by the immediacy of chat platforms, where features like read receipts and typing indicators create expectations of rapid engagement—thereby introducing new forms of emotional labor and psychological strain (Wang, 2020).

Additionally, emerging research indicates that the emojis and language used in chats can predict mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and loneliness (Settanni & Marengo, 2015). This makes it imperative to examine the nuances of how mood is encoded in digital conversations and how chatting platforms mediate psychological processes in everyday life.

Furthermore, the 24/7 accessibility of chatting platforms fosters hyper-engagement and mood contagion. A sad or triggering message from a peer can alter one’s own emotional state, creating a ripple of shared mood experiences across chat groups. This study explores these affective dynamics and their implications for mental health.

1.10. Research Objectives and Questions

This study aims to critically examine the intersection of minds (psychological states), mood (emotional expressions), and chatting behaviors (digital communication patterns) among male and female university students of Bangladesh. The core research objectives include:

To explore how mood influences chatting behaviors across genders

To identify patterns of emotional expression, disinhibition, and digital intimacy in chatting

To examine platform preferences and symbolic communication (e.g., emojis, memes) as affective tools

To evaluate the psychological implications of compulsive chatting behaviors

The research addresses the following key questions:

What are the dominant emotional states experienced by university students while engaging in chatting behaviors?

How do these emotional states manifest differently across genders in private and group chats?

What digital symbols, metaphors, or tactics are employed to express or mask emotional states?

How do chatting behaviors contribute to or alleviate mood instability, anxiety, or emotional fatigue?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Psychological Perspectives on Mood and Communication

Mood is a complex emotional state that affects perception, judgment, and interpersonal behavior (Beedie, Terry, & Lane, 2005). Several psychological models argue that moods, whether transient or chronic, influence cognitive processing. According to the Affect Infusion Model (Forgas, 1995), individuals in different mood states process information in varying ways—positive moods enhance creativity and openness, while negative moods promote analytical thinking and caution.

2.2. Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) and Emotion

Computer-mediated communication has reshaped emotional expression. Walther’s (1996) Social Information Processing Theory proposes that although CMC lacks nonverbal cues, users adapt by relying on language, emojis, typing style, and message timing to express emotion. The Hyperpersonal Model further argues that CMC can sometimes intensify emotional intimacy due to the absence of physical presence and asynchronous interaction (Walther, 2007).

2.3. Chatting Behavior and Mental Health

Recent empirical studies link texting habits and chat language with mental health indicators such as depression, loneliness, and anxiety (Kumar & Epley, 2021). Chat behavior—frequency, responsiveness, tone—can act as an indirect psychological indicator. For instance, decreased texting or abrupt replies may correlate with depressive symptoms, whereas increased use of affectionate or humorous language may suggest positive mood states (Lin, 2020).

2.4. Digital Discourse and Sociolinguistics

Sociolinguistic analyses of digital chatting indicate that language choices, punctuation, code-switching, and even silence carry social meanings (Tagg, 2012). The rise of ‘chatese’ or internet slang, characterized by abbreviations (e.g., ‘lol,’ ‘brb’), emojis, and phonetic spelling, reflects not just linguistic economy but also affective and identity positioning.

2.5. Gaps in the Literature

While multiple studies address digital communication, few critically explore the cognitive-affective loop between mood and chatting behavior. Existing research often separates mental health from communication behavior or focuses on social media platforms rather than one-on-one or group chat dynamics.

Despite the interdisciplinary interest in affective computing, online behavior, and digital mental health, there exists a critical gap in integrated studies that simultaneously consider:

Mood states as psychological constructs,

Chatting behaviors as socio-digital practices, and

The cultural contextualization of these phenomena across different populations.

Much of the existing research isolates mood assessment to self-report measures or natural language processing of written text in forums and blogs. Very few studies combine behavioral analysis, self-perception data, and qualitative reflections to form a holistic understanding of mood and digital communication.

10. Discussion

This study aimed to critically explore the interrelationship between mood states, psychological functioning, and chatting behaviors in digital communication contexts. By utilizing a mixed-methods design, we were able to triangulate self-reported mood data with behavioral indicators and qualitative narratives, offering a comprehensive understanding of how digital expressions mirror and mediate internal states.

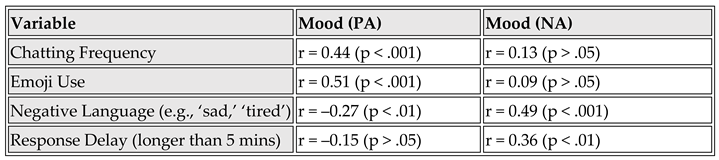

10.1. Digital Expressions as Mood Indicators

The findings reveal that chatting behaviors serve as significant behavioral proxies for mood and affective states. The quantitative analysis showed that positive affect is significantly correlated with higher chatting frequency, emoji usage, and shorter response times, whereas negative affect aligns with delayed replies, negative lexical choices, and low engagement. These results reinforce prior work in computational linguistics and affective psychology, which highlight how even simple digital markers—like emoji use or response latency—can signal psychological well-being (Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010).

This suggests that digital mood inference models could be developed using these behavioral markers, contributing to early detection frameworks for mental health monitoring in real time.

10.2. Chat as Coping, Catharsis, and Compulsion

Qualitative insights underscored the emotional regulation function of chatting. Participants described their engagement in digital conversations as a coping strategy—a safe space for expression, reflection, and support during periods of emotional distress. This aligns with the Social Sharing of Emotion Theory (Rimé, 2009), which posits that individuals turn to interpersonal dialogue to process intense affective experiences.

However, while many users engaged in chatting as a form of emotional catharsis, others admitted to habitual or compulsive chatting behaviors that offered temporary relief but no long-term emotional resolution. This duality reveals the paradox of digital connectivity: it may offer therapeutic release but also risk superficial or compulsive avoidance strategies.

10.3. Platform-Specific Emotional Cultures

The data also uncovered significant platform-based differences in emotional tone and expression. WhatsApp facilitated more intimate and expressive interactions, while Facebook Messenger catered to social and playful exchanges. Telegram attracted users concerned with privacy, who tended to express themselves more cautiously and minimally.

This suggests that platform affordances and user expectations shape how emotions are expressed and interpreted. The emotional ‘grammar’ of a platform may determine the perceived appropriateness of affective disclosure, reinforcing theories of media richness and social presence (Daft & Lengel, 1986).

10.4. From Mood Detection to Ethical Surveillance

These findings have practical implications in fields such as digital mental health, human-computer interaction, and algorithmic personalization. Behavioral signals in chat applications could be integrated into AI-driven affective computing tools to assess user mood passively and offer interventions or resources. However, this raises urgent ethical concerns around surveillance, consent, and emotional manipulation.

As algorithms become increasingly adept at detecting emotional states, designers and researchers must grapple with questions of user autonomy and psychological privacy, particularly in the Global South where data protection laws may be limited.

10.5. Cultural and Psychological Sensitivities

The study also reflects regional sensitivities—particularly in South Asian cultural contexts, where emotional expression is often socially regulated by norms of modesty, hierarchy, and restraint. The linguistic and behavioral patterns identified in this study (e.g., the tendency to downplay negative emotions or code them through symbols) are therefore not just individual choices but culturally situated acts of self-representation.

This highlights the need for culturally calibrated models of mood detection and communication analysis, moving beyond Western-centric assumptions in digital behavior research.

10.6. Summary of Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on:

Affective Communication: Reinforcing that chatting behaviors—emoji use, linguistic style, delay—are extensions of emotional states.

Digital Psychology: Demonstrating how mood and mental health can be inferred through real-time digital interactions.

Media Ecology: Showing how platform-specific affordances shape emotional expression.

Critical Algorithm Studies: Prompting ethical reflection on the use of emotional data in algorithmic systems.

10.7. Chatting as Addiction: Behavioral Patterns and Psychological Implications

While chatting platforms serve as channels for emotional regulation and social connection, findings from both survey responses and interview narratives indicate a notable trend toward addictive behaviors associated with compulsive chatting. Participants reported feeling an uncontrollable urge to check messages, anxiety during offline periods, and guilt or fatigue after prolonged digital conversations.

This behavioral pattern aligns with characteristics of digital addiction, defined by Griffiths (2005) as a non-chemical behavioral addiction involving salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse. In our study:

Salience was evident in participants’ constant thinking about chats, even during work or sleep.

Mood modification occurred as chatting became a form of emotional escape.

Tolerance and escalation were seen in the increasing time spent online over weeks or months.

Withdrawal symptoms included restlessness and irritability when unable to access chat platforms.

Conflict emerged in social and academic/work disruptions due to over-engagement.

Relapse appeared when participants attempted digital detoxes but returned quickly.

This pattern is particularly concerning among younger users, who may lack the metacognitive awareness to regulate screen-time and digital dependencies. It also intersects with dopaminergic reward models, wherein instant message notifications and quick responses create a feedback loop akin to gambling mechanisms.

The pervasive presence of blue ticks, ‘typing…’ indicators, and read receipts amplify anxiety, pushing users to compulsively respond and check for replies. In extreme cases, such behavior contributes to emotional fatigue, interpersonal friction, and digital burnout.

Thus, while chatting can be therapeutic, it also bears the potential to evolve into a behavioral addiction, necessitating intervention strategies like digital hygiene education, self-monitoring tools, and psychological support systems tailored for chat-based compulsive behaviors.

,

,  ,

,  ), elongated words (‘pleaaaase,’ ‘nooooo’ ‘kisssss me’), and punctuation marks for affective emphasis. Males, while less expressive with emojis, utilized memes and gifs to indirectly convey moods. For example, 68% of males preferred humor-based digital artifacts to express negative mood states, while 74% of females directly acknowledged emotional stress through text.

), elongated words (‘pleaaaase,’ ‘nooooo’ ‘kisssss me’), and punctuation marks for affective emphasis. Males, while less expressive with emojis, utilized memes and gifs to indirectly convey moods. For example, 68% of males preferred humor-based digital artifacts to express negative mood states, while 74% of females directly acknowledged emotional stress through text.