1. Introduction

To address the challenges of "who farms the land" and "how to farm efficiently", agricultural production trusteeship (APT) has emerged as an innovative socialized service model. This approach allows producers to retain land management rights while delegating partial or full agricultural activities (e.g., plowing, planting, pest control, harvesting) to specialized service organizations or individuals, effectively integrating smallholder farmers into modern agricultural development[

1].By 2023, China had over 1.07 million agricultural socialized service organizations, serving more than 91 million smallholders[

2] and significantly increasing their income through production trust services. However, rapid expansion of APT has exposed critical issues: supply-demand imbalances[

3], service mismatches[

4], and weak benefit-sharing mechanisms[

5], which threaten its sustainability[

6]. Compared to land transfer models[

7,

8],APT exhibits two distinct features[

9].Scale through Coordination: Concentrating fragmented plots into contiguous fields and transferring production activities to specialized providers, thereby deepening division of labor among stakeholders[

10].Multi-Actor Collaboration: Facilitating risk-sharing and benefit-allocation through coordinated partnerships, reducing conflicts inherent in traditional land leasing[

11].From the perspective of symbiosis theory, symbiotic units with diverse resource endowments form mutually beneficial relationships under specific symbiotic modes[

12]. These relationships drive the emergence of functionally specialized symbiotic units based on division of labor [

13], where "specialized division of labor" serves as the foundation for symbiotic evolution. The stability of symbiotic systems depends on balanced development among stakeholders: significant disparities weaken system resilience, making "coordinated development" a core requirement for symbiotic evolution. The principles of "division of labor" and "coordinated development" align with the dual characteristics of agricultural production trusteeship [

14], offering theoretical and practical guidance for resource allocation, benefit distribution, and risk management in service implementation.

Against this backdrop, this study focuses on trusteeship smallholders, service organizations, and the government as core agents within the system. Existing research employs symbiosis theory, niche theory, and Lotka-Volterra models to examine agricultural symbiosis: analyses of dyadic co-evolution (e.g., agribusiness-farmers or agribusiness-cooperatives [

15]) predominantly emphasize mutualism as the optimal evolutionary trajectory [

16]. Key variables influencing symbiotic relationships include default costs, trust levels, niche overlap, blocking coefficients [

17], specialization of symbiotic units [

18], and symbiotic network environments [

19]. The government plays a critical role by providing policy support and market safeguards for trusteeship services. While no studies directly address symbiosis between trusteeship organizations and governments, research on agricultural industrialization alliances acknowledges governmental importance[

20], offering indirect insights. Given the complexity of tripartite symbiosis, current literature lacks direct exploration of multi-agent interactions among smallholders, organizations, and governments [

21]. However, methodological foundations exist: multi-agent symbiotic models (e.g., Lotka-Volterra applications in maker spaces [

22] and digital innovation ecosystems [

23]) provide frameworks for analyzing tripartite dynamics. Case studies on fruit cold-chain logistics [

24], safety production systems [

25], camellia oleifera industries [

26], and BOP entrepreneurship [

27] further validate how multi-agent co-evolution enhances systemic efficacy, offering theoretical and empirical support [

28].

Existing literature reveals evolutionary mechanisms of symbiosis among diverse agents, yet agricultural studies predominantly focus on dyadic relationships, overlooking systemic dynamics of multi-agent networks. Direct analysis of symbiosis within agricultural production trusteeship systems remains scarce [

29,

30]. Furthermore, while simulation-based studies of symbiotic relationships abound, few probe the equilibrium conditions or dynamic evolutionary patterns underlying their formation. To bridge these gaps, this study conceptualizes agricultural production trusteeship as a complex dynamic ecosystem. By examining the fundamental architecture of agent symbiosis, we investigate how symbiotic morphologies co-evolve with system developmental stages [

31]. Through analyzing variations in symbiotic coefficients, we reveal dynamic evolutionary pathways and stability conditions. Building on agent-based modeling of dual-agent and tripartite evolutionary trajectories, we further simulate governmental impacts on symbiotic modes. This framework aims to foster resource complementarity and synergistic advantages among trusteeship agents, ultimately achieving win-win mutualism across organizations, smallholders, and governments.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Operational Mechanism

2.1. Agricultural Production trusteeship Service Ecosystem

Ecosystem theory originated in ecology and was innovatively extended to business domains by scholars including Moore [

32], forming the conceptual framework of business ecosystems. Symbiosis theory, proposed by German mycologists in the late 19th century, emphasizes interdependence and co-evolution among organisms. Chinese scholar Yuan Chunjing [

33] applied this theory to economic management, establishing a framework centered on coexistence and mutualism, encompassing three symbiotic elements, fundamental principles, and mode classifications [

34]. Building on these foundations, this study conceptualizes the agricultural production trusteeship service ecosystem as a complex, dynamic, and polycentric symbiotic entity. Within this system, trusteeship organizations, smallholders, and governments function as core symbiotic units, exhibiting interconnected evolution in resource acquisition and value co-creation [

35]. Through self-organizing evolution, these units progressively advance symbiotic modes to achieve resource complementarity, output expansion, and sustainable agricultural development [

26].

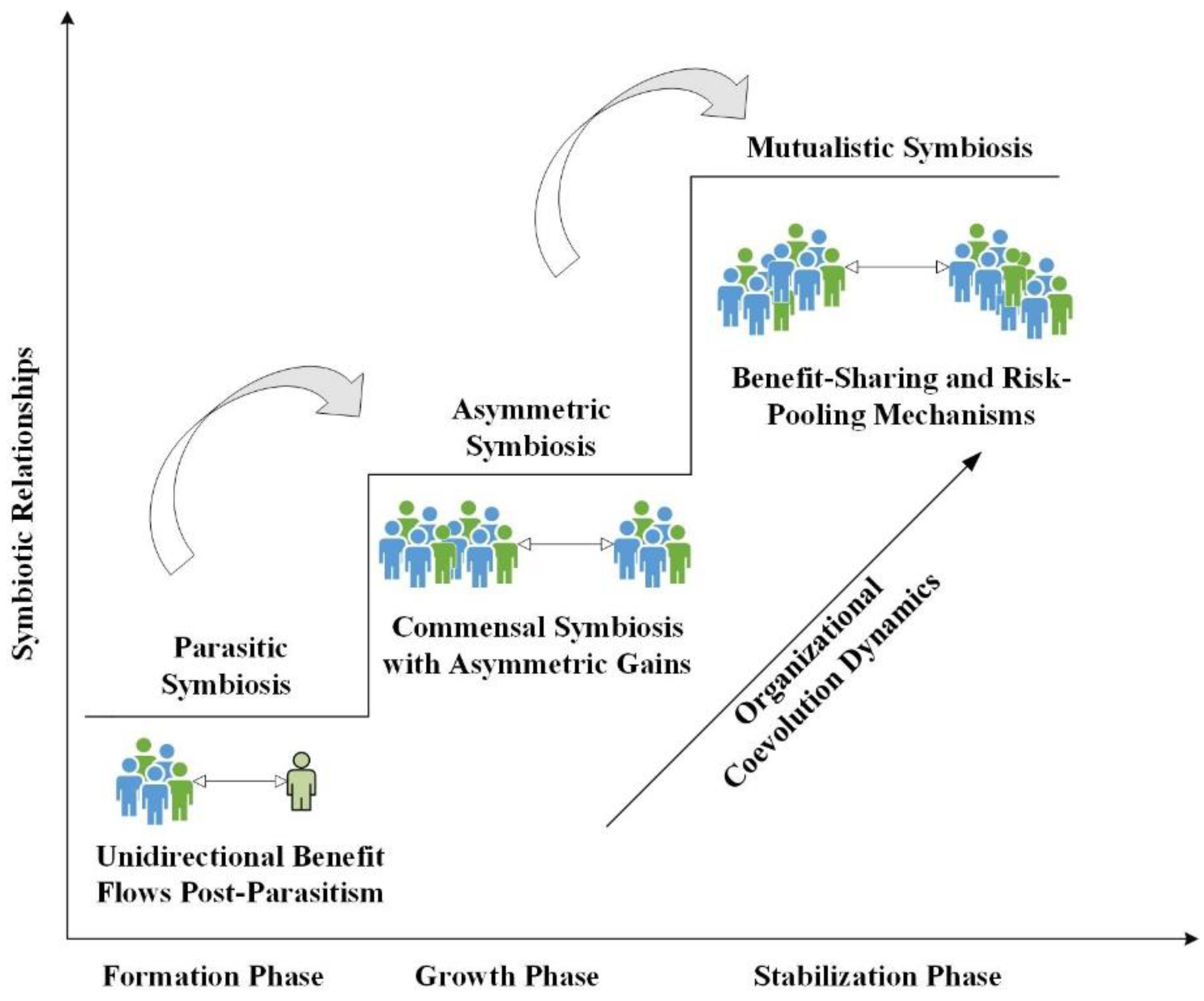

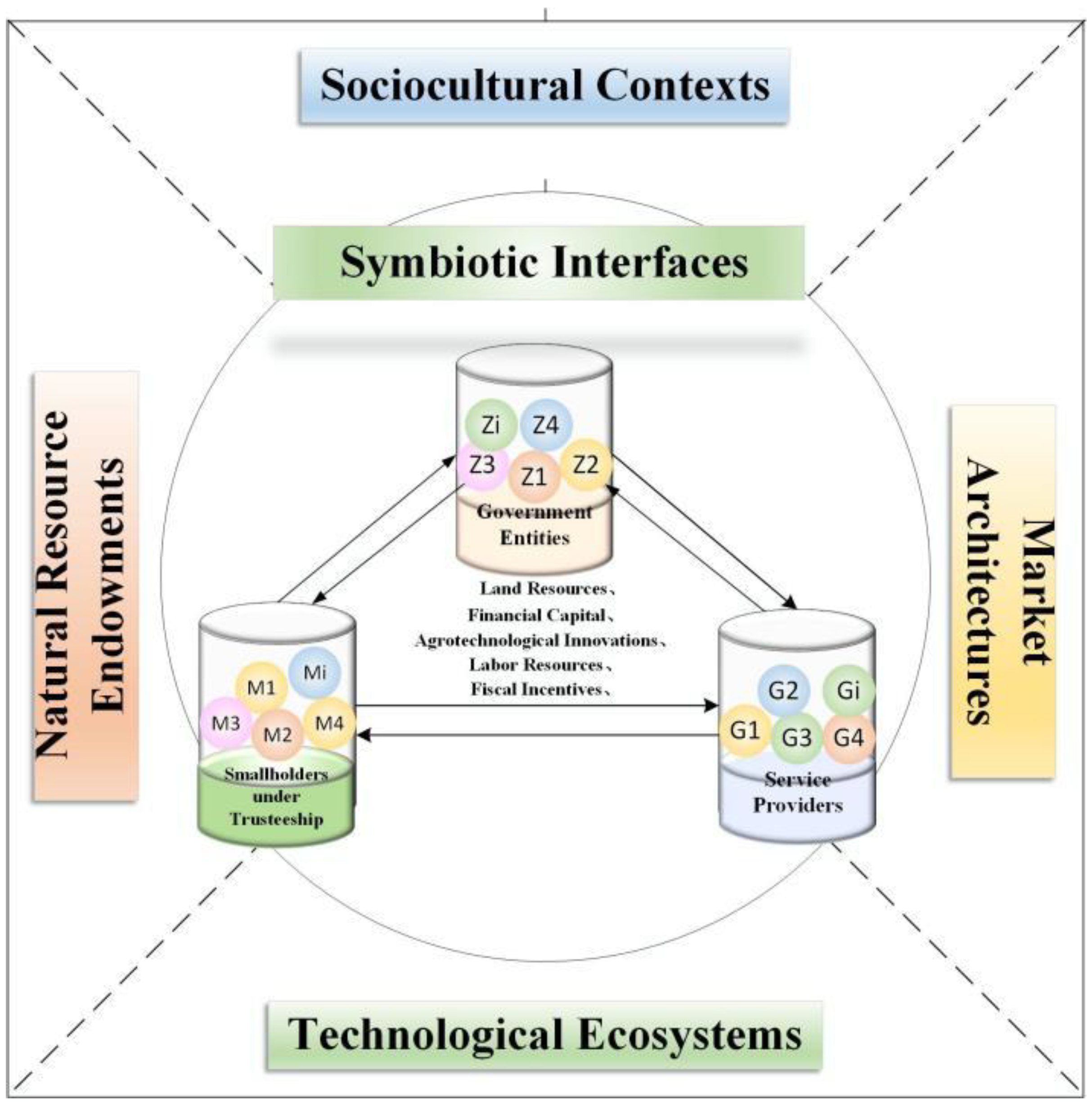

2.2. Dynamic Symbiotic Coordination in Agricultural Production trusteeship Service Ecosystems

This study deconstructs the APT service ecosystem through the “Triadic Symbiosis Framework” (symbiotic units, modes, and environments) and elaborates its evolutionary mechanisms, as visualized in

Figure 1.

2.2.1. Synergistic Linkages Among Symbiotic Units

As the fundamental units for energy flow and transformation within symbiotic systems, symbiotic units optimize resource allocation and exchange. Trusteeship organizations, smallholders, and governments constitute the three core units, achieving resource complementarity and shared value through dynamic interactions of key parameters like capital and technology, thereby establishing mutualistic cooperation. Specifically, trusteeship organizations rely on smallholders' financial contributions to sustain operations and generate service revenues. By introducing advanced crop varieties and technologies, they enhance smallholders' productivity and income. Reciprocally, benefited smallholders amplify organizations' brand influence and market share, expanding service coverage through strong resource synergy. The government, functioning as the regulatory nexus, facilitates systemic functionality [

37]. It provides fiscal subsidies and technical training to enhance agricultural value-added and market competitiveness. Legal safeguards protect farmer rights and service security, fostering an enabling environment for industrial development. This tripartite linkage drives integrated advancement [

38].

2.2.2. Evolutionary Dynamics of Symbiotic Modes

As the metric for inter-unit connectivity and interaction intensity, symbiotic modes differ from biological population symbiosis yet share core logic of interdependence and co-evolution. Given tight inter-agent linkages, independent coexistence is precluded, focusing analysis on three modes: parasitic, commensalistic, and mutualistic symbiosis—the latter being the evolutionary ideal [

39].

Under parasitic symbiosis, benefits flow unidirectionally. Manifestations include: service organizations disregarding farmers' informed consent and misappropriating government subsidies; farmers violating contracts or delaying payments; local governments delaying subsidies or inequitable resource allocation. These opportunistic behaviors cause imbalanced benefit distribution, destabilizing the system and precipitating cooperation collapse. Commensalistic symbiosis benefits only one unit. Service organizations leverage industrial advantages to monopolize market information and channels, gaining control at potential opportunity cost to farmers. While not directly harming farmers, this mode constrains coordinated development by limiting mutual gains. Mutualistic symbiosis establishes bidirectional benefit flows among smallholders, organizations, and governments. All agents enhance efficacy or revenue through cooperation, achieving peak efficiency in information and energy exchange. This fosters stable social trust, cooperative mechanisms, and benefit synergy-representing the optimal configuration for agricultural production trusteeship.

2.2.3. Mechanisms of influence in symbiotic environments

As the foundational milieu enabling dynamic evolution of symbiotic units and modes, the symbiotic environment safeguards system stability [

40]. A robust environment encompasses multidimensional domains-human, market, natural resource, and technological dimensions-providing fertile ground for optimized resource allocation and efficient utilization. Within a supportive market environment, symbiotic relationships reduce transaction costs and internalize cooperative mechanisms, enhancing systemic operational efficiency to foster an inclusive co-adaptive ecosystem. Regarding the human dimension, rural-urban labor migration creates production pressures mitigated by trusteeship services, which simultaneously diversify income streams for part-time farmers. Critically, an optimal symbiotic environment amplifies positive externalities, deepening resource complementarity and sharing mechanisms. This empowers symbiotic units to achieve peak growth under dual guarantees of efficiency and institutional order.

Figure 2.

Symbiotic evolution trend.

Figure 2.

Symbiotic evolution trend.

3. Dyadic Symbiotic Evolution in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems: Agent-Based Simulation of Service Providers and Smallholders

The symbiotic environment, as a composite of critical factors underpinning the dynamic evolution of symbiotic units and modes, ensures the stable operation of APT ecosystems. A well-structured symbiotic environment provides fertile ground for optimal resource allocation and efficient utilization within the system. Under the catalysis of a positive market environment, the establishment of symbiotic relationships effectively reduces transaction costs, thereby enhancing overall operational efficiency and fostering an inclusive, co-evolutionary market landscape. In socio-demographic contexts, the rise of APT models addresses challenges posed by rural labor migration, alleviating production pressures on aging agricultural labor and creating diversified income channels for part-time farmers. An ideal symbiotic environment promotes the deepening of resource complementarity and sharing mechanisms, ultimately enabling symbiotic units to achieve optimal growth under dual guarantees of efficiency and institutional order.

3.1. Modeling Dyadic Symbiotic Evolution: Service Providers and Smallholders

This study constructs an evolutionary model to analyze the co-development dynamics between service providers and smallholders in APT ecosystems, grounded in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. The APT ecosystem comprises two core agents—smallholders and service providers—whose growth trajectories are constrained by intrinsic factors (e.g., technological capacity, financial access, operational costs) and follow Logistic growth dynamics, implying intrinsic growth ceilings rather than indefinite expansion.

Hypothesis 2. Bidirectional interactions exist between agents, with directional effects quantified by symbiotic coefficients (positive values denote mutualistic facilitation, negative values indicate antagonistic inhibition).

Hypothesis 3. Agents attain optimal fitness states (maximum efficiency) when marginal output equals marginal input, after which growth stabilizes.

The symbiotic evolution of the two-agent system is formalized by the following equations:

E1(t)、E2(t):Fitness indices (resource acquisition and value creation efficiency) of service providers and smallholders at time t. ri>0 (i =1、2): Intrinsic growth rates. Ki(i =1、2) :Maximum fitness under resource constraints (Logistic coefficients).1-:Self-inhibition effects due to intra-agent resource competition. σij(i≠j, i=1,2 j=1,2): Symbiotic coefficients reflecting inter-agent facilitation.

3.2. Evolutionary Patterns and Stability Conditions in Dyadic Symbiosis

The interplay between service providers and smallholders generates distinct symbiotic patterns based on directional intensity variations of symbiotic coefficients

σij, as summarized in

Table 1:

A stable equilibrium occurs when both agents achieve maximum fitness (

=0,

=0), yielding four equilibrium points:

Z1(0,0),

Z2(0,

),

Z3(

,0),

Z4.The system’s stability is evaluated via the Jacobian matrix[

41]:

An equilibrium is asymptotically stable if

Det(J)>0、

Tr(J)<0.Stability conditions for each equilibrium are detailed in

Table 2.

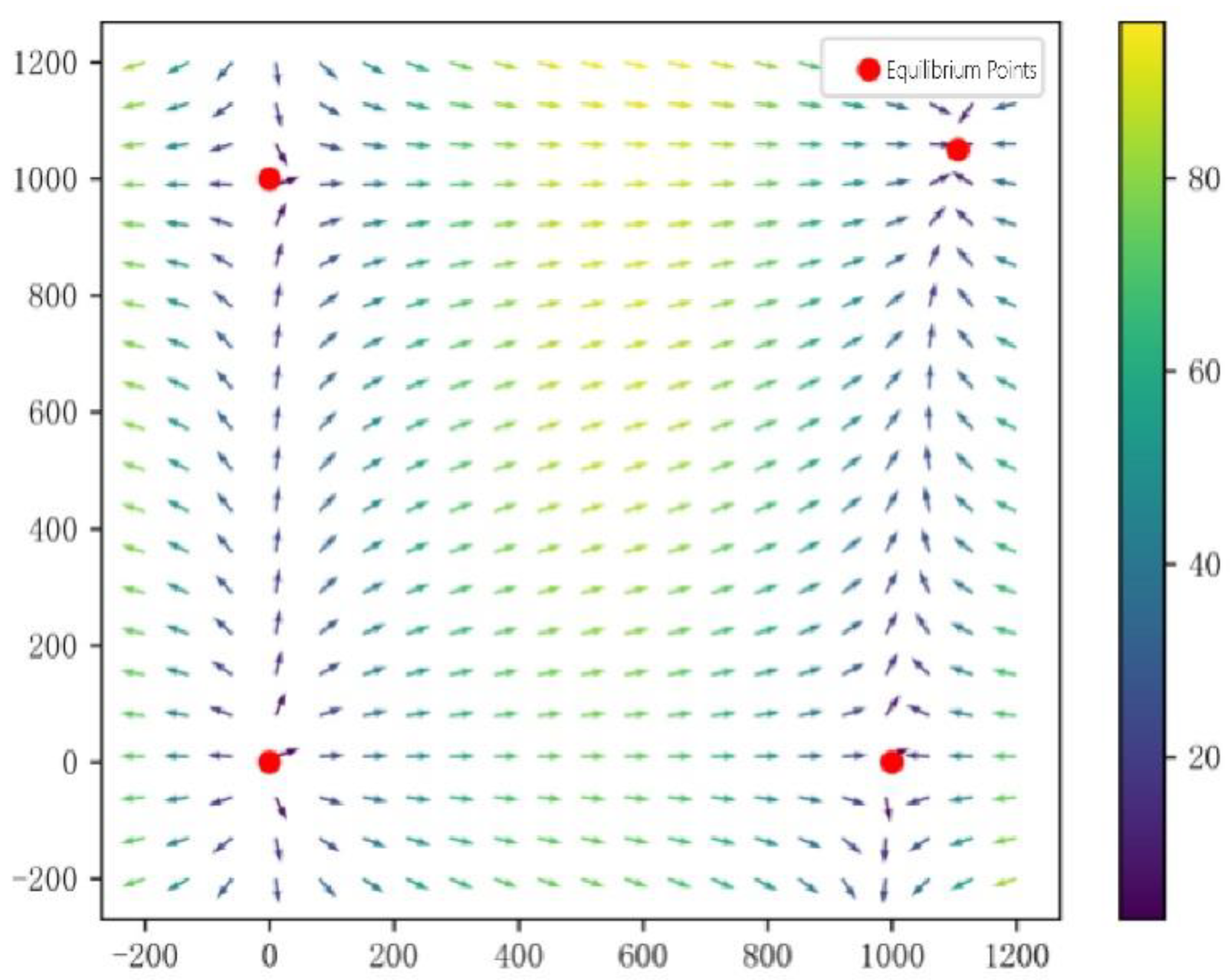

The analysis reveals that equilibrium points in the dyadic symbiosis are intrinsically linked to symbiotic modes, governed by the magnitudes of symbiotic coefficients(σ12,σ21)and intrinsic growth ceilings(K1,K2).Both commensalism and symmetric mutualism converge to the same equilibriumZ4, while parasitism may stabilize at Z1(0,0),Z2(0,),Z3(,0).Upon reaching equilibrium, agents’ fitness stabilizes at their respective maxima. Phase portraits (visualized via Python’s Matplotlib) illustrate system dynamics. Z1(0,0):All trajectories diverge from this equilibrium, indicating zero systemic resilience to external shocks. Z2(0,),Z3(,0):Partial inward trajectories suggest transient stability, yet systemic collapse is inevitable as one agent dominates. Z4: Represents asymptotically stable mutualism/commensalism. Deviations from Z4 self-correct through bidirectional resource flows, maximizing efficiency in information and energy exchange. Z1、Z2、Z3are economically unsustainable (agent extinction at xi=0). Z4 embodies Pareto-efficient cooperation, where both agents enhance fitness through synergies, aligning with evolutionary stable strategy (ESS) principles.

Figure 3.

Phase Portraits and Equilibrium Analysis of Symbiotic Evolution in APT Service Ecosystems.

Figure 3.

Phase Portraits and Equilibrium Analysis of Symbiotic Evolution in APT Service Ecosystems.

3.3. Agent-Based Simulation of Provider-Smallholder Symbiosis

Based on the theoretical analysis above, to explore the impact of varying conditions on system stability, this study conducts simulation analyses of the two-agent system. This aims to deeply investigate the co-evolutionary trajectories and steady-state characteristics of the system under different symbiotic conditions. To better compare the changes in growth efficacy of trusteeship organizations and farmers under non-symbiotic conditions, and considering that trusteeship organizations possess more abundant material resources, play a dominant role in the service process, and experience stronger growth-promoting effects, this paper—drawing on parameter-setting approaches from relevant mainstream literature[

42]-sets the maximum efficacy of both parties under resource and technological constraints to 1000. The intrinsic growth rates for the organization and farmers are set to 0.3 and 0.1, respectively. As trusteeship services act simultaneously on both agents, the initial efficacy values for both are assumed to be 100 and 100. The system is observed over 400 iterations [

43].

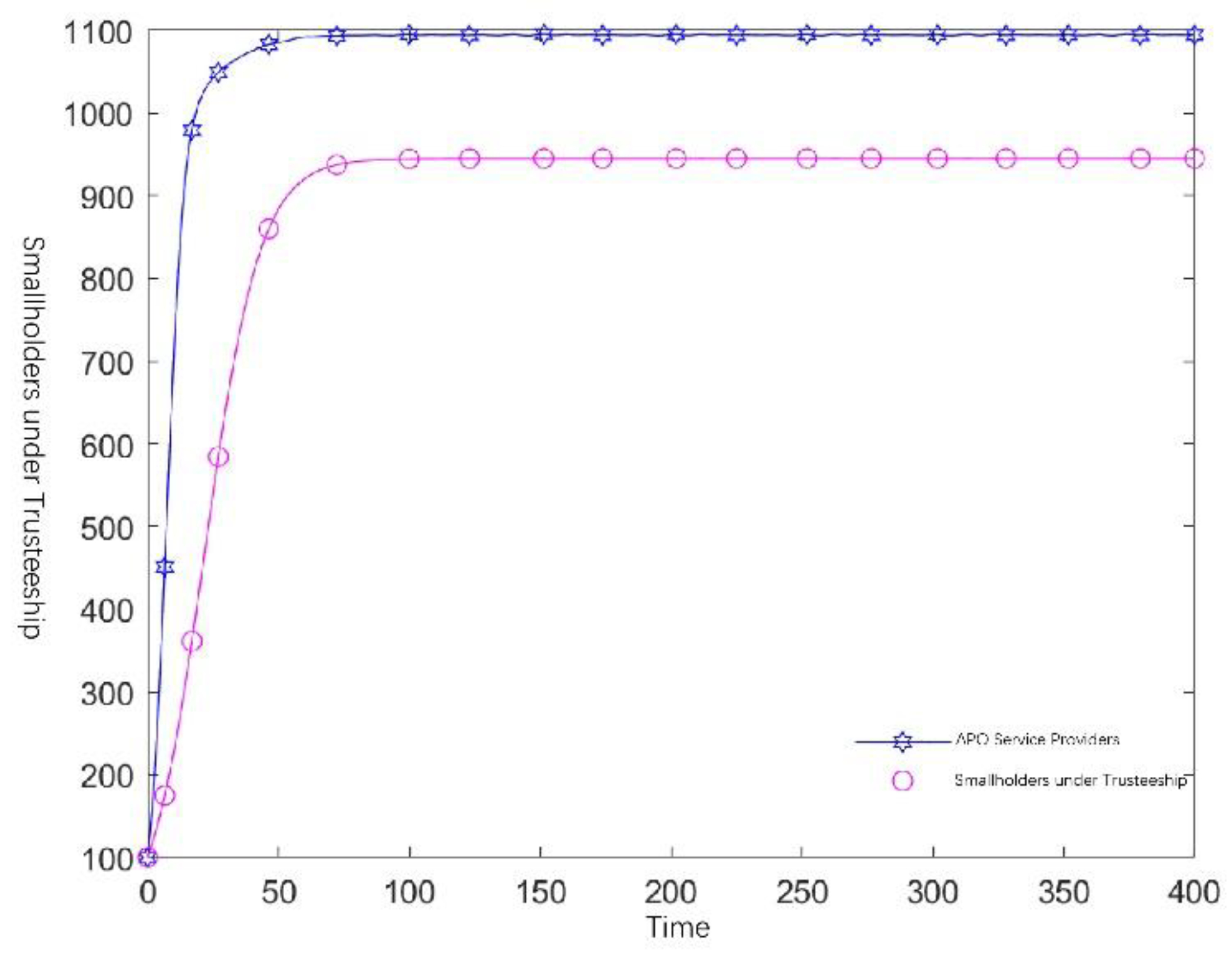

3.3.1. Parasitic Symbiosis

As shown in

Figure 4, when

σ12σ21<0,

σ12=0.1,

σ21=-0.05,the system exhibits parasitic symbiosis, typical in early developmental stages. Under this scenario, resource transfer occurs unidirectionally during symbiosis. Leveraging substantial external support, trusteeship organizations surpass their standalone growth ceilings-yet this growth often occurs at the expense of farmers' interests, manifesting as neglect of their right to information and choice and introducing latent default risks. Farmers exhaust resources without securing proportional profits, resulting in diminished resource acquisition capabilities compared to autonomous operations. Consequently, the partnership paradoxically inhibits farmer efficacy. Over time, such relationships inevitably collapse. Parasitic entities cannot perpetually depend on hosts but must proactively transition toward mutualistic symbiosis.

The underlying reasons involve:1. Institutional deficiencies: Early-stage development lacks robust oversight and benefit-distribution mechanisms. Absent uniform service standards and effective supervision compromise service quality, damaging system credibility and farmer participation;2. Information asymmetry: Organizations possess superior market intelligence and privileged access to agricultural innovations, restricting farmers' productivity and income gains;3. Inadequate contractual enforcement: While contracts should safeguard interests, weak enforcement coupled with farmers' limited legal awareness enables frequent defaults.

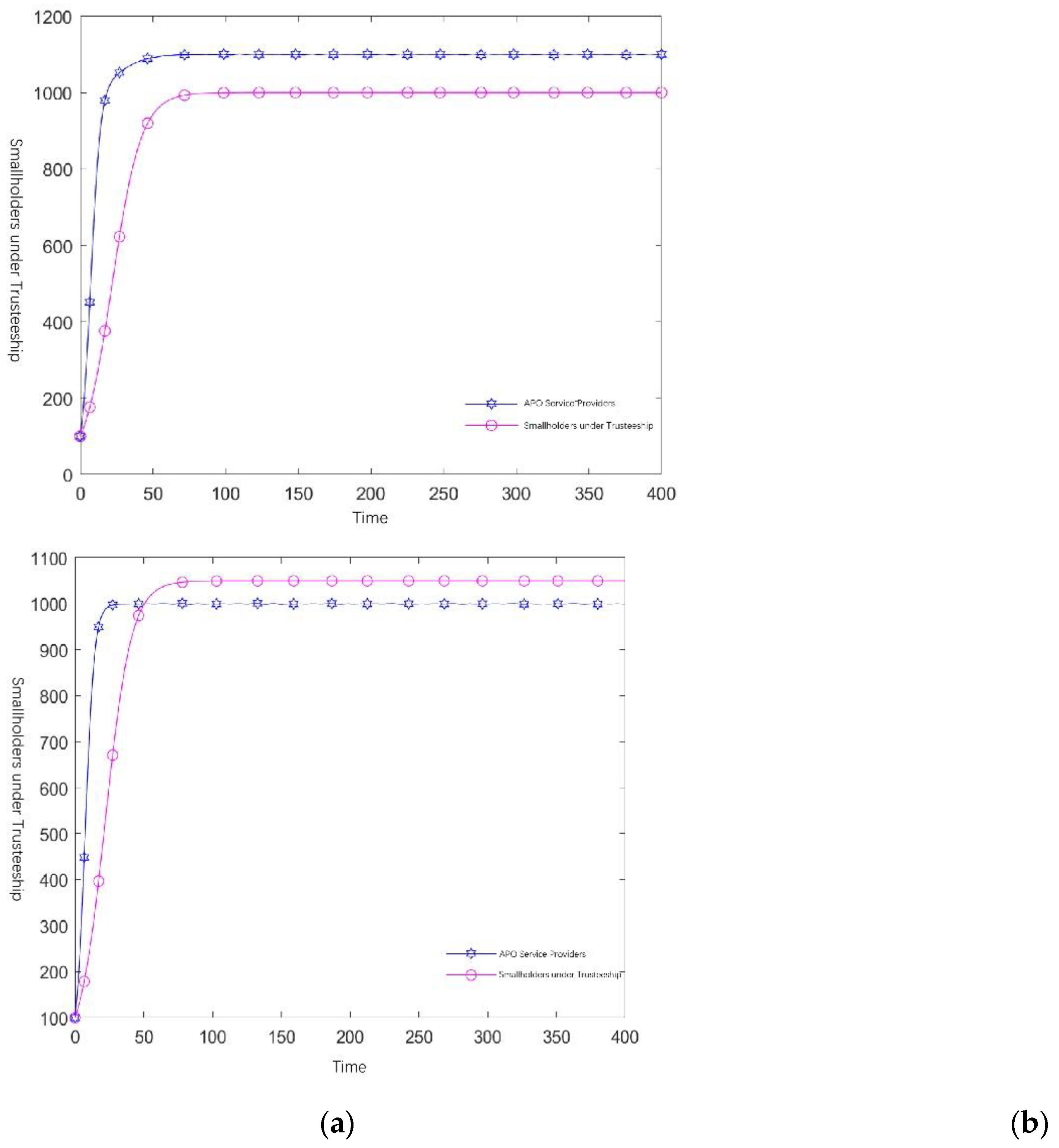

3.3.2. Commensal Symbiosis Between Service Providers and Smallholders

In commensal symbiosis (

σ12=0.1,

σ21=0,

Figure 5a), trusteeship organizations demonstrate significant benefit. Farmers exert substantial positive effects on organizations, enabling them to exceed maximum efficacy achievable in standalone operations. Conversely, when farmers are beneficiaries (

σ12=0,

σ21=0.05,

Figure 5b), they exhibit neutral feedback—neither significantly enhancing nor inhibiting organizational efficacy. Though benefited, farmers cannot yet adequately reciprocate or reinforce organizational growth. This pattern features unidirectional resource transfer from agents with positive symbiosis coefficients (

σij>0) to those with neutral coefficients (

σij =0), effectively compensating for detriments observed in parasitic symbiosis. Commensalism represents a transitional phase toward mutualism, heralding a more rational multi-agent agricultural production trusteeship ecosystem.

Key drivers include:1. Fragmented resource integration: Critical elements—land, capital, technology, and expertise—remain inadequately consolidated. Disjointed regional planning further causes disorderly development and redundant infrastructure, impeding structured organizational systems and economies of scale;2. Immature agent development: Prolonged cooperation risks eroding farmers' autonomous management and technological innovation capacities, fostering over-reliance on organizations. Simultaneously, organizations' truncated service chains and limited service typology constrain their ability to meet diversified farmer needs, undermining long-term competitiveness and sustainability.

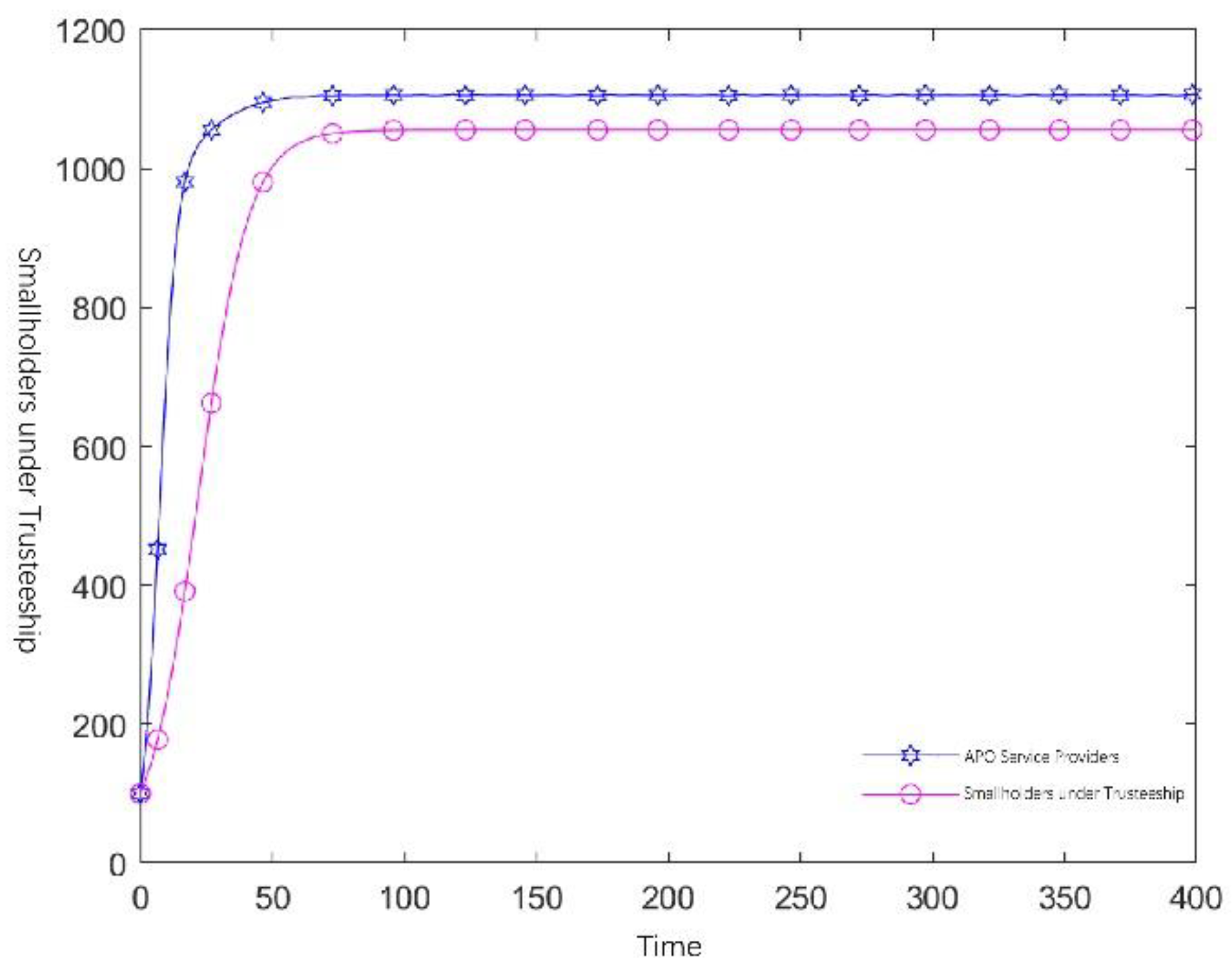

3.3.3. Mutualistic Symbiosis Between Service Providers and Smallholders

Under mutualistic symbiosis, both service providers and smallholders exhibit positive symbiotic coefficients. As illustrated in

Figure 6(

σ12=0.1,

σ21=0.05),mutualism enhances resource acquisition efficiency beyond autonomous growth limits, with fitness gains proportional to the magnitude of symbiotic coefficients. This reflects resource complementarity through specialized division of labor, where bidirectional resource sharing and collaborative governance optimize agricultural input allocation, achieving authentic mutualism.

The evolutionary trajectory toward stable equilibrium depends critically on the interplay of σ12 and σ21.While parasitic and commensal modes represent transitional or suboptimal states (e.g., power asymmetry or contractual fragility), mutualism emerges as the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). It resolves inefficiencies inherent in early-stage APT systems by aligning incentives, minimizing transaction costs, and institutionalizing cooperative norms—ultimately driving systemic resilience and Pareto-optimal outcomes.

4. Tripartite Symbiotic Evolution in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems: Government-Mediated Agent-Based Simulation

Building upon the dyadic framework, this section introduces government entities as a third-party agent endowed with regulatory oversight, stabilization mechanisms, and multidimensional support, thereby constructing a tripartite symbiotic ecosystem. We analyze how governmental integration reshapes evolutionary trajectories while retaining prior model parameters. Given the government’s multifaceted roles-spanning policy formulation, coordination, and institutional safeguards-that transcend unidimensional quantification, we operationalize its impact through government efficacy, a composite metric reflecting dynamic adjustments in symbiotic coefficients and resource allocation efficiency. This approach aligns with FAO’s governance frameworks for inclusive agricultural service systems, where state interventions recalibrate power asymmetries and optimize Pareto frontiers without oversimplifying institutional complexity.

4.1. Tripartite Evolutionary Model: Integrating Government Entities

The dyadic ecosystem (service providers-smallholders) faces inherent limitations in resource accessibility and directional governance, necessitating the integration of government entities to catalyze systemic resilience. The tripartite symbiotic evolution is formalized as:

>0:Intrinsic growth rate of government efficacy.

: Maximum institutional capacity under resource constraints.: Self-inhibition coefficient (growth-inhibiting effects from intra-governmental resource competition).

σij(i≠j,i=1,2,3 j=1,2,3): Cross-agent symbiotic coefficients. Let

、

、

=0 and further derive the ecosystem's interaction matrix for equilibrium point Z as follows:

When ,.Then, equilibrium point Z8(,) is globally asymptotically stable.The equilibrium points and their corresponding stability conditions are summarized as follows:

Table 3.

Equilibrium Points and Stability Analysis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship System

Table 3.

Equilibrium Points and Stability Analysis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship System

| No. |

Equilibrium Point |

Stability Condition |

Eigenvalues |

| 1 |

Z1(0,0,0) |

Unstable |

All positive |

| 2 |

Z2(K1,0,0) |

<-1 |

All negative |

| 3 |

Z3(0,K2,0) |

<-1 |

All negative |

| 4 |

Z4(0,0,K3) |

<-1 |

All negative |

| 5 |

|

Unstable |

Contains positive values |

| 6 |

|

Unstable |

Contains positive values |

| 7 |

|

Unstable |

Contains positive values |

| 8 |

) |

|

All negative |

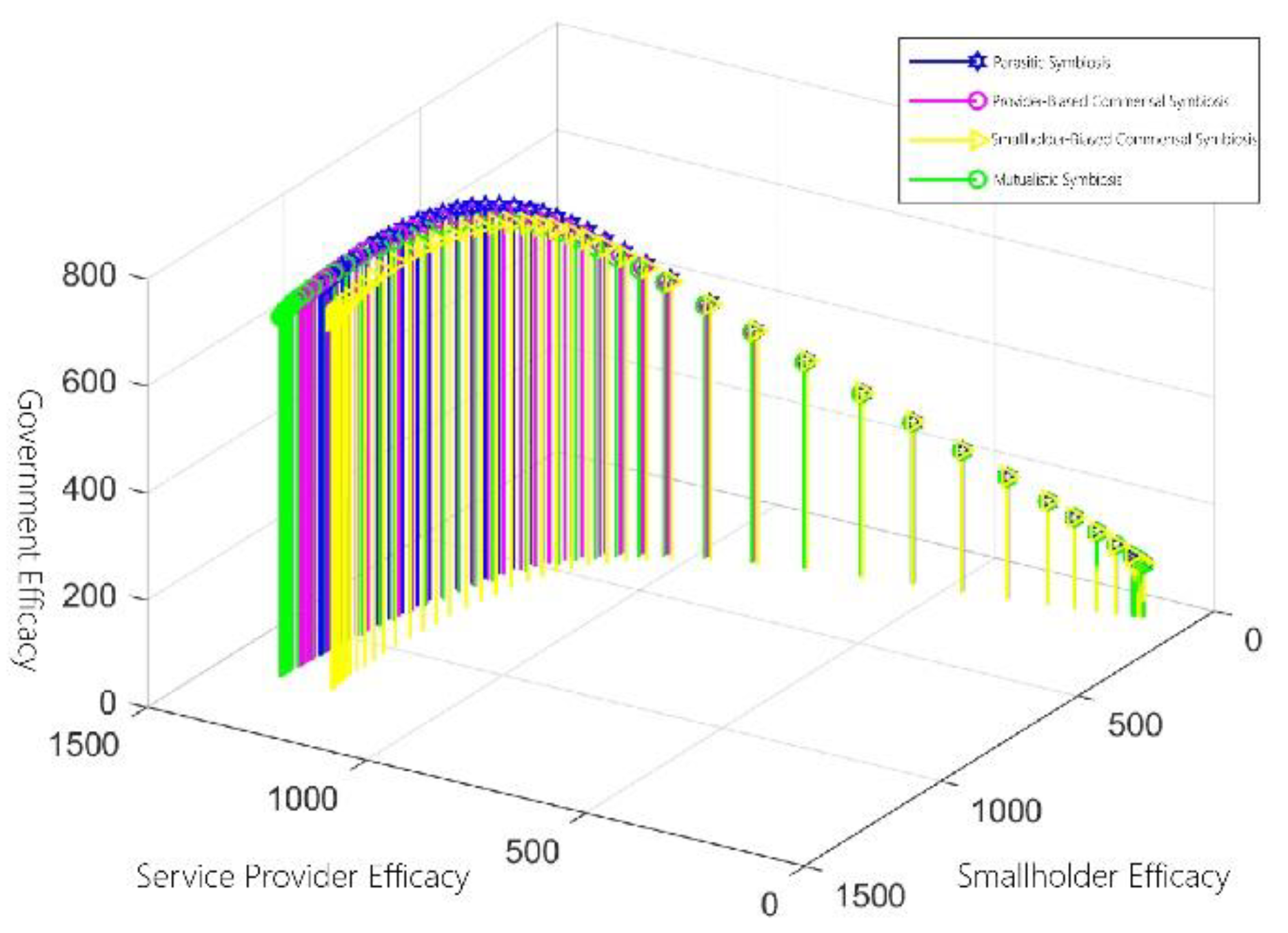

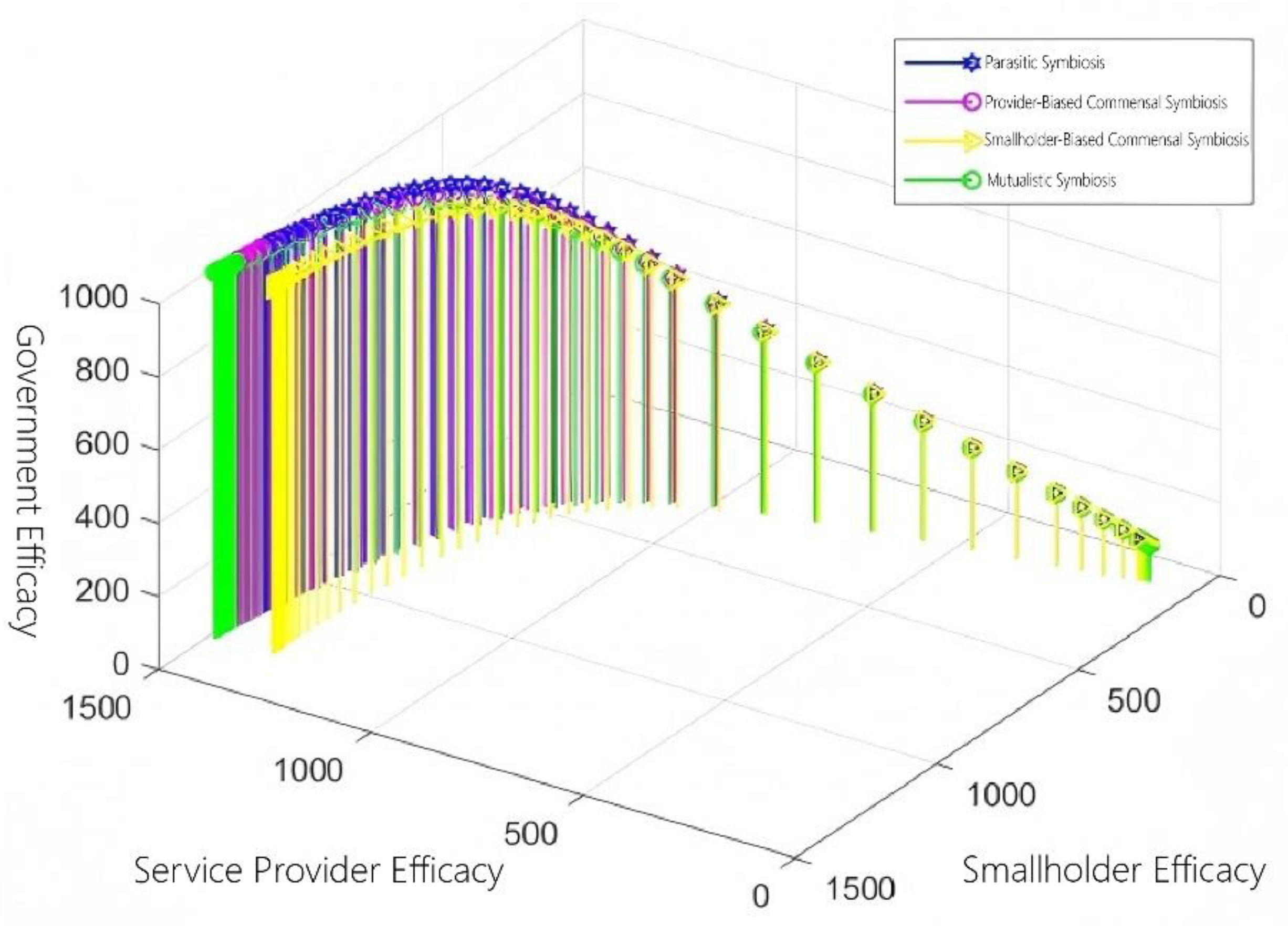

4.2. Tripartite Symbiotic Simulation: Government-Mediated Parasitic Dynamics

Based on the preceding stability analysis of the system, numerical simulations are conducted to further investigate the impact of government participation on ecosystem agents and their interactive evolution. Drawing on mainstream literature designs, the government’s intrinsic growth rate is set at 0.2, with its maximum efficacy under density-dependent constraints at 1000 for autonomous development. The evolutionary cycle spans t = 400 iterations.

4.2.1. Government-Mediated Tripartite Parasitic Symbiosis Simulation

Under the scenario where government intervention—as an external factor—establishes parasitic symbiosis with the original dual-agent system (organizations and farmers), this study thoroughly examines its impact on the system's co-evolutionary pathways, with detailed parameter configurations provided in

Table 4.In this context, regardless of pre-existing symbiotic modes, government involvement consistently enhances growth efficacy for both agents, exerting positive developmental influences while injecting new vitality and safeguards into the ecosystem. Government-participated parasitic symbiosis predominates during initial collaboration phases, where loose inter-agent coordination often leads to over-reliance on governmental resources. This neglects endogenous capacity building and may trigger improper subsidy-seeking behaviors. Consequently:1. Government fiscal burdens intensify while its developmental efficacy remains constrained.2. Expected leadership and safeguarding functions remain under-realized.3. Subjectively driven incentive measures suppress governmental efficacy.4. Eroded governance credibility and unsustainable practices emerge.5. Socioeconomic stability faces latent risks.

Figure 7.

Tripartite Symbiosis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems Under.

Figure 7.

Tripartite Symbiosis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems Under.

4.2.2. Government-Mediated Tripartite Commensal Symbiosis Simulation

Under government-mediated commensal symbiosis, symbiotic coefficients (

Table 5) reveal asymmetric resource flows: service providers and smallholders leverage governmental subsidies to enhance service capacity and accelerate growth, surpassing autonomous fitness ceilings . Government entities exhibit positive symbiotic coefficients, indicating dual roles as growth catalysts (e.g., subsidized mechanization) and regulatory enforcers (e.g., contract standardization). While providers and smallholders optimize value creation through policy-enabled resource integration, government efficacy stagnates due to absent reciprocal feedback, constraining systemic supply-demand structure optimization.

Systemic Implications:1.Transitional Bridge: Commensalism acts as an evolutionary pathway from parasitism to mutualism, signaling emergent polycentric governance where multi-stakeholder incentives align.2.Institutional Trade-offs: Unidirectional support models prioritize short-term agricultural output over long-term institutional resilience, echoing FAO’s critique of subsidy-dependent systems in developing contexts.3.Policy Redesign Imperative: Transitioning to mutualism requires recalibrating to incentivize bidirectional resource loops (e.g., farmer-led innovation feeding back into policy design).

Figure 8.

Tripartite Symbiosis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems Under Government-Mediated Commensal Dynamics.

Figure 8.

Tripartite Symbiosis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems Under Government-Mediated Commensal Dynamics.

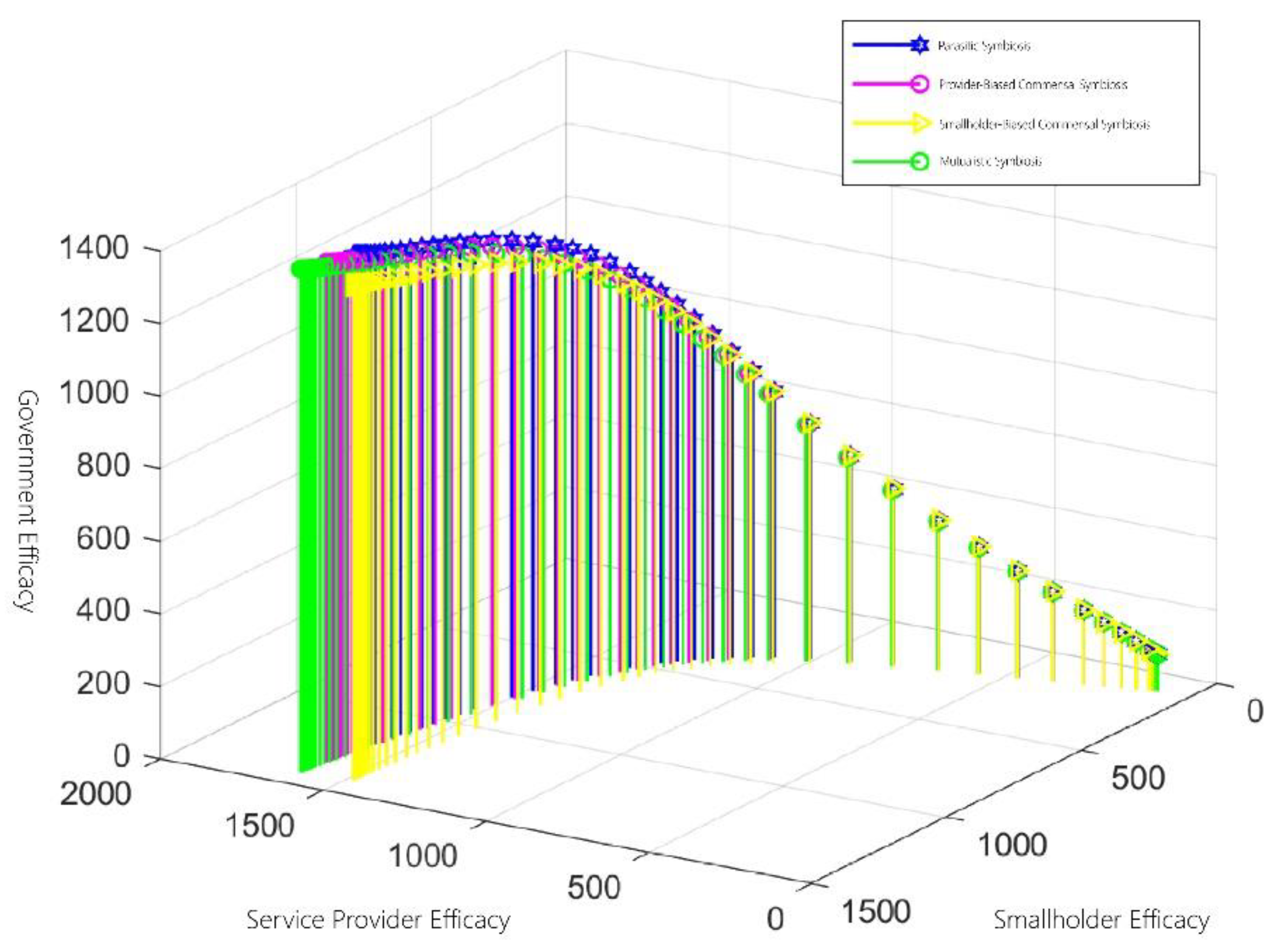

4.2.3. Government-Mediated Tripartite Mutualistic Symbiosis Simulation

The government plays a pivotal role in APT ecosystems by strategically mobilizing its institutional and financial resources to bolster the growth trajectories of service providers and smallholders.Through unhindered resource-information flows and adaptive governance frameworks, tripartite symbiosis fosters synergistic co-evolution: providers and smallholders achieve efficiency gains via specialized division of labor, while government entities enhance their institutional efficacy through participatory policy calibration. Crucially, governmental intervention elevates the evolutionary fitness ceilings across all symbiotic stages—parasitic, commensal, and mutualistic—transcending mere resource provision to act as a systemic catalyst that optimizes input allocation and institutional trust. By institutionalizing cooperative norms (e.g., transparent subsidy mechanisms, digital knowledge-sharing platforms), the APT ecosystem emerges as a resilient, self-reinforcing network where multi-stakeholder collaboration drives sustainable intensification, aligning with FAO’s agroecological transition pathways and SDG-driven agrarian futures.

Table 6.

Tripartite Symbiotic Modes Under Government-Mediated Mutualistic Dynamics

Table 6.

Tripartite Symbiotic Modes Under Government-Mediated Mutualistic Dynamics

| Provider-Smallholder Relationship |

Symbiotic Coefficients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Parasitic Symbiosis |

0.1 |

0.35 |

-0.05 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

0.1 |

| Commensal Symbiosis (Provider-Biased) |

0.1 |

0.35 |

0 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

0.1 |

| Commensal Symbiosis (Smallholder-Biased) |

0 |

0.35 |

0.05 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

0.1 |

| Mutualistic Symbiosis |

0.1 |

0.35 |

0.05 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

0.1 |

Figure 9.

Tripartite Symbiosis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems Under Government-Mediated Mutualistic Dynamics.

Figure 9.

Tripartite Symbiosis in Agricultural Production Trusteeship Ecosystems Under Government-Mediated Mutualistic Dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This study constructs and simulates symbiotic evolutionary dynamics within dual-agent and tri-agent trusteeship service systems from a symbiosis theory perspective. It analyzes equilibrium points, stability conditions, and evolutionary trajectories across symbiotic modes, examining governmental impacts and optimal mutualism conditions. Key findings are:

5.1. Stability Determinants

The steady state of the Agricultural Production Trusteeship Service Ecosystem depends on both symbiosis coefficients and maximum growth efficacy. Each agent’s efficacy growth is intrinsically linked to others’ efficacy levels. When symbiosis coefficients are universally positive, positive synergistic interactions emerge—enabling service organizations, farmers, and government to mutually benefit from cooperation. This elevates their developmental ceilings, with higher coefficients yielding increasingly pronounced enhancements.

5.2. Dynamic Evolutionary Process

APT ecosystems evolve dynamically through sequential transitions—parasitic → commensal → mutualistic symbiosis—each governed by distinct stability thresholds. Parasitic and commensal modes reveal systemic vulnerabilities, including resource overdependence and asymmetric benefits, which hinder genuine mutualism. Mutualism, as the evolutionarily stable equilibrium, maximizes systemic efficiency through balanced resource exchange and Pareto-optimal outcomes.

5.3. Governmental Catalysis

Introducing government entities as third-party agents enhances systemic stability and sustainability. Through policy incentives (e.g., subsidies, technical training) and institutional safeguards (e.g., contract standardization), governments act as resource guarantors and developmental catalysts, elevating tripartite fitness ceilings beyond autonomous limits. With all symbiotic coefficients positive, the system stabilizes at states exceeding independent growth maxima, demonstrating differentiated synergies in resource sharing and value co-creation across modes, ultimately converging toward tripartite mutualism.

6. Practical Implications

Currently, few entities in China’s APT ecosystems have reached the stage of mutualistic symbiosis. Challenges such as insufficient endogenous capacity building, limited resource scalability, and trust deficits persist during the evolutionary process. Based on the findings, this study proposes actionable insights from three perspectives: coordinating symbiotic units, strengthening symbiotic interfaces, and optimizing symbiotic environments.

6.1. Coordinate Symbiotic Units to Enhance Agent Capabilities

Service organizations must enhance their resource integration capabilities and value co-creation capacities, elevating service quality to boost effective supply. By consolidating diversified farmer needs and advancing organizational coordination, they can drive contiguous demand aggregation and scale economies in trusteeship services.Concurrently, governments should:Develop and institutionalize an Agricultural Production Trusteeship Service System.Formulate synergistic preferential policies and regulatory strategies to incentivize organizations and farmers.Optimize symbiotic environments while standardizing market mechanisms.

6.2. Strengthen Symbiotic Interfaces to Facilitate Multi-Actor Interaction

Within symbiotic systems, symbiotic interfaces serve as conduits facilitating qualitative parameter exchange among symbiotic units. The system should intensify information flow and energy transfer between agent units, with functional restructuring through mechanisms like introducing agricultural intermediary organizations as connective nodes when necessary. Trusteeship service organizations must prioritize cultivating and recruiting agricultural talent to enhance bilateral connectivity. This strengthens benefit-coupling mechanisms, overcoming developmental bottlenecks during critical phases while enabling symbiotic benefit transfer and information dissemination.

6.3. Optimize Symbiotic Environments to Foster Systemic Resilience

6.3.1. Market Environment Enhancement

Establish a robust agricultural product market system to improve logistics efficiency and market competitiveness. Strengthen market supervision to prevent unfair competition and monopoly practices.

6.3.2. Socio-Environmental Improvement

Upgrade rural infrastructure and social service systems to elevate living standards and resident well-being. Implement skills enhancement programs for rural labor forces to increase their adaptability to modern agricultural development.

6.3.3. Technological Environment Advancement

Intensify agricultural innovation and technology extension to boost production efficiency and product quality. Promote digital enablement in trusteeship services through IT applications, enhancing informationization and intelligentization levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G. and J.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, X.G, J.Z. and J.Z.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, J.Z..; data curation, X.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, H.Z.; visualization, H.Z.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, X.G.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, Youth Program (Grant No. [23JYC00102]), "Effects and Pathways of Comprehensive Trusteeship in Advancing High-Quality Grain Production".

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, F.B.; Zhang, Y.L. Agricultural Family Management: Policy Logic over a Century of the Communist Party and Practical Orientation in the New Era. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 10, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Fu, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Can Agricultural Production Services Influence Smallholders’ Willingness to Adjust Their Agriculture Production Modes? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.W.; Jiang, C.Y. Development Models and Industrial Attributes of Agricultural Producer Services. Jianghuai Trib. 2017, 2, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Y. Practice and Organizational Dilemmas of Land Trusteeship: Reflections on Constructing Agricultural Socialized Service Systems. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.).

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, P.X. Can Agricultural Socialized Services Bridge Smallholders and Agricultural Modernization? A Technical Efficiency Perspective. J. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2019, 9, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.W.; Ding, J.B. Misconceptions and Strategies for High-Quality Development of Agricultural Producer Services in the 14th Five-Year Plan Period. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2021, 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Qian, Y.; Kong, F. Does Outsourcing Service Reduce the Excessive Use of Chemical Fertilizers in Rural China? The Moderating Effects of Farm Size and Plot Size. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Qian, Y.; Yu, H. Farmers’ Participation Model and Stability of Agricultural Scale Management: Based on the Comparison of Land-Scale Management and Service-Scale Management. Econ. Manag. 2021, 35, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Yu, Z. Land Transfer or Trusteeship: Can Agricultural Production Socialization Services Promote Grain Scale Management? Land 2023, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Li, Z. Research on the Coordination of Rural Land Scale Management and Service Scale Management under the Background of “Separation of Three Powers”. Economist 2021, 6, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.K.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, S.Y.; et al. Impact of Land Trusteeship and Green Technology Adoption on Agricultural Productivity. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2024, 45(6), 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; Fahad, S.; Kagatsume, M.; Yu, J. Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Farmland Transfer: Insight on the Mediating Role of Agricultural Production Service Outsourcing. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liang, D. Embedded Development Mechanisms of Agricultural Industrialization Alliances in Linking Farmers. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.).

- Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Lu, Q.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Q. Production Process Outsourcing, Farmers’ Operation Capability, and Income-Enhancing Effects. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.L.; Zhang, S.M. Symbiotic Evolution Mechanisms and Simulation Between Leading Enterprises and Farmer Cooperatives: Based on Logistic Growth Models. J. Shandong Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.).

- Sun, Q.; Yin, G.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Zhu, S. Social Network Analysis of Farmers after the Private Cooperatives’ “Intervention” in a Rural Area of China—A Case Study of the Xiang X Cooperative in Shandong Province. Agriculture 2024, 14, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Andrew. Starbird. Designing Food Safety Regulations: The Effect of Inspection Policy and Penalties for Noncompliance on Food Proces—sor Behavior. Journal of Agricultural & Resource Economics.

- Stephen J Zaccaro, Zachary N.J Horn. Leadership theory and practice: Fostering an effective symbiosis. he Leadership Quarterly, 7: 14(6).

- Mathieu Fortin; François Ningre ;Nicolas Robert; Frédéric Mothe. Quan⁃ tifying the impact of forest management on the carbon balance of the forest-wood product chain: A case study applied to even-aged oak stands in France. (279):, 1: and Management, 2012(279), 2012.

- Wang, Y.R.; Wang, H.Q. Realization Mechanisms and Determinants of Agricultural Industrialization Alliances: An Empirical Analysis Based on Farm Household Survey Data. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44(6), 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H. Agricultural Machinery Service System: Model Comparison and Policy Optimization—An Investigation Based on the Perspective of Differentiation of Agricultural Management Subjects. Rural Econ. 2018, 10, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W.Q.; Li, C.; Hui, S.M. Symbiotic Modes in Innovation Ecosystem of Crowd-Creative Spaces: A Study Based on Lotka-Volterra Model. Audit Econ. Res. 2021, 36(3), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, L.J.; Liu, J.T.; Xiao, Y.X.; et al. Symbiotic Modes in Digital Innovation Ecosystems. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022, 40(8), 1481–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.W.; Deng, X.Y.; Pang, Y.; et al. Tripartite Symbiotic Evolution in Cold Chain Logistics Systems for Forestry Fruits. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2024, 5, 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.H.; Fu, L. Study on the mutualistic symbiosis model among symbiotic units in occupational safety and health symbiotic system. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management.

- Pang, Y. Optimization of Symbiotic Relationships Between Agri-Supply Chain Enterprises and Smallholders: A Case Study of Camellia Oil. Seeker 2016, 6, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X.H.; Miao, X.M.; Ma, H.Y. Achieving Sustainable BOP Entrepreneurship in the Digital Economy: A Tripartite Symbiotic Evolution Perspective. Soft Sci. 2023, 37(9), 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kousar, R.; Abdulai, A. Off-farm work, land tenancy contracts and investment in soil conservation measures in rural Pakistan. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 60, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner R, Kapoor R. Innovation ecosystems and the pace of substitution: Re- examining technology Scurves. Strategic Management Journal,.

- Li, M.; Tian, Z.R.; Lu, Y.Z. Symbiotic Evolution and Cultivation Mechanisms of Green Innovation Ecosystems. Technol. Econ. 2024, 43(4), 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H.; Li, L.; Zhu, H.; et al. Symbiotic Evolution in Emerging Technology Innovation Ecosystems. Chin. Soft Sci. 2024, 1, 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Moore J, F. Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harvard Business review, 1993, 71(3): 75.

- Yuan, C.Q. Symbiosis Theory and Its Application to Small-Scale Economies (Part I). Reform 1998, 2, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenherr, T.; Narayanan, S.; Narasimhan, R. Trust formation in outsourcing relationships: A social exchange theoretic perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 169, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, X. Farmland Rental Market, Outsourcing Services Market and Agricultural Green Productivity: Implications for Multiple Forms of Large-Scale Management. Land 2024, 13, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N.; Pan, J.Y. How Does Agricultural Production Trusteeship Affect Farmers' Adoption of Green Technologies? Chin. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 4, 210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Sriboonchitta, S. Promotion Effect of Agricultural Production Trusteeship on High-Quality Production of Grain—Evidence from the Perspective of Farm Households. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sean, M.H. The perilous effects of capability loss on outsourcing management and performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Li, J. Mechanisms, Dilemmas, and Pathways of "Three-Society" Integrated Development: A Symbiosis Theory Perspective. J. Southwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.).

- Wu, X.L. The Evolutionary Logic of Urban-Rural Governance in China over Seven Decades. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 2, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, Y.L.; Chen, J.F.; Wang, H.M.; et al. Adaptability Assessment of China’s Regional "Water-Energy-Food" Nexus System from a Symbiotic Perspective. Chin. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30(1), 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.L.; Yin, Q.; et al. Land Trusteeship Services: A SWOT Analysis. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2014, 46(10), 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Lu, W.J. How Can Multiple Actors Achieve Symbiosis in Rural Environmental Governance under PPP Mode? An Evolutionary Game Theory Approach. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).