Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Demographic Characteristics

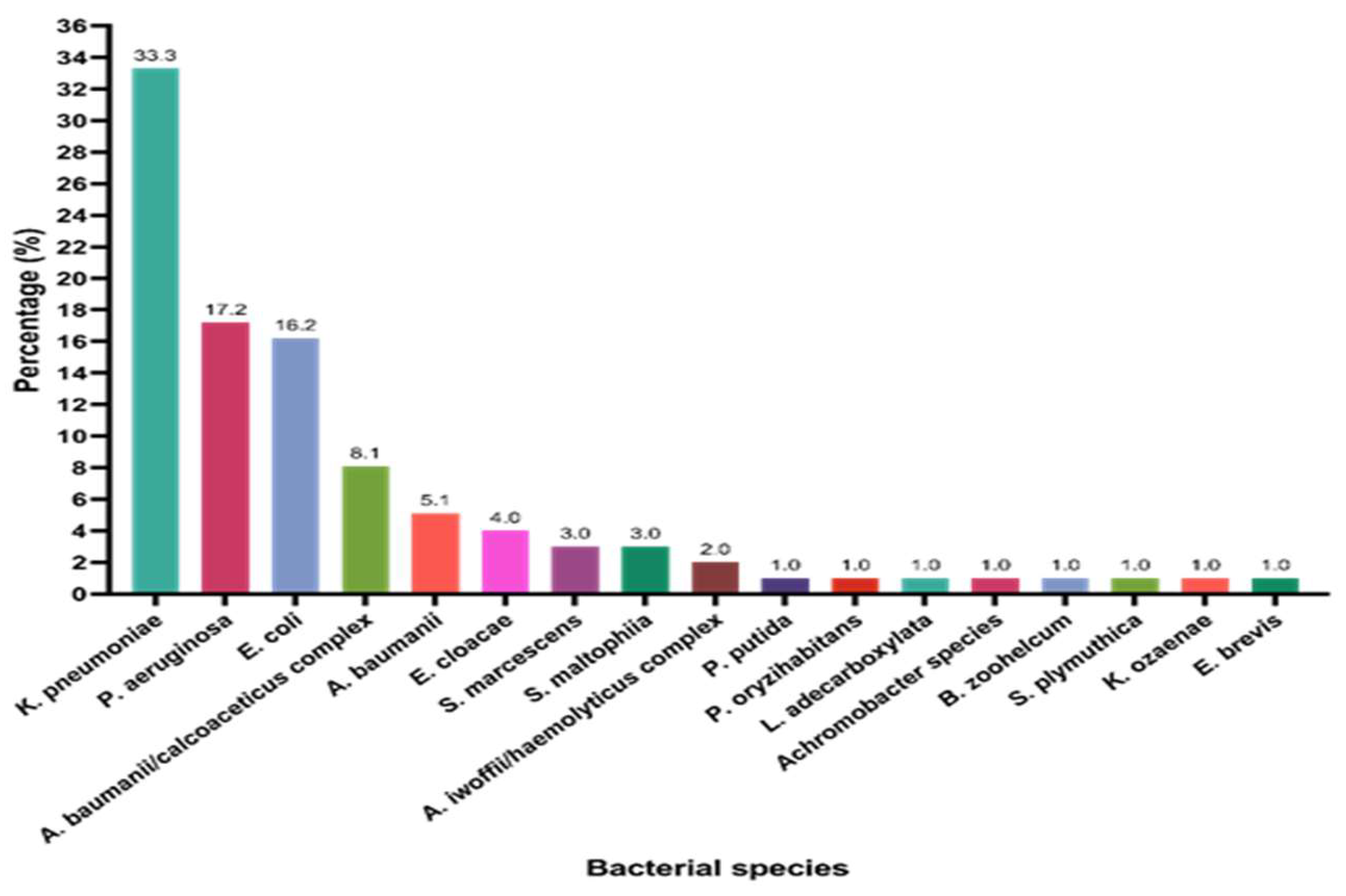

2.2. Organism Identification and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

2.1. Subsection

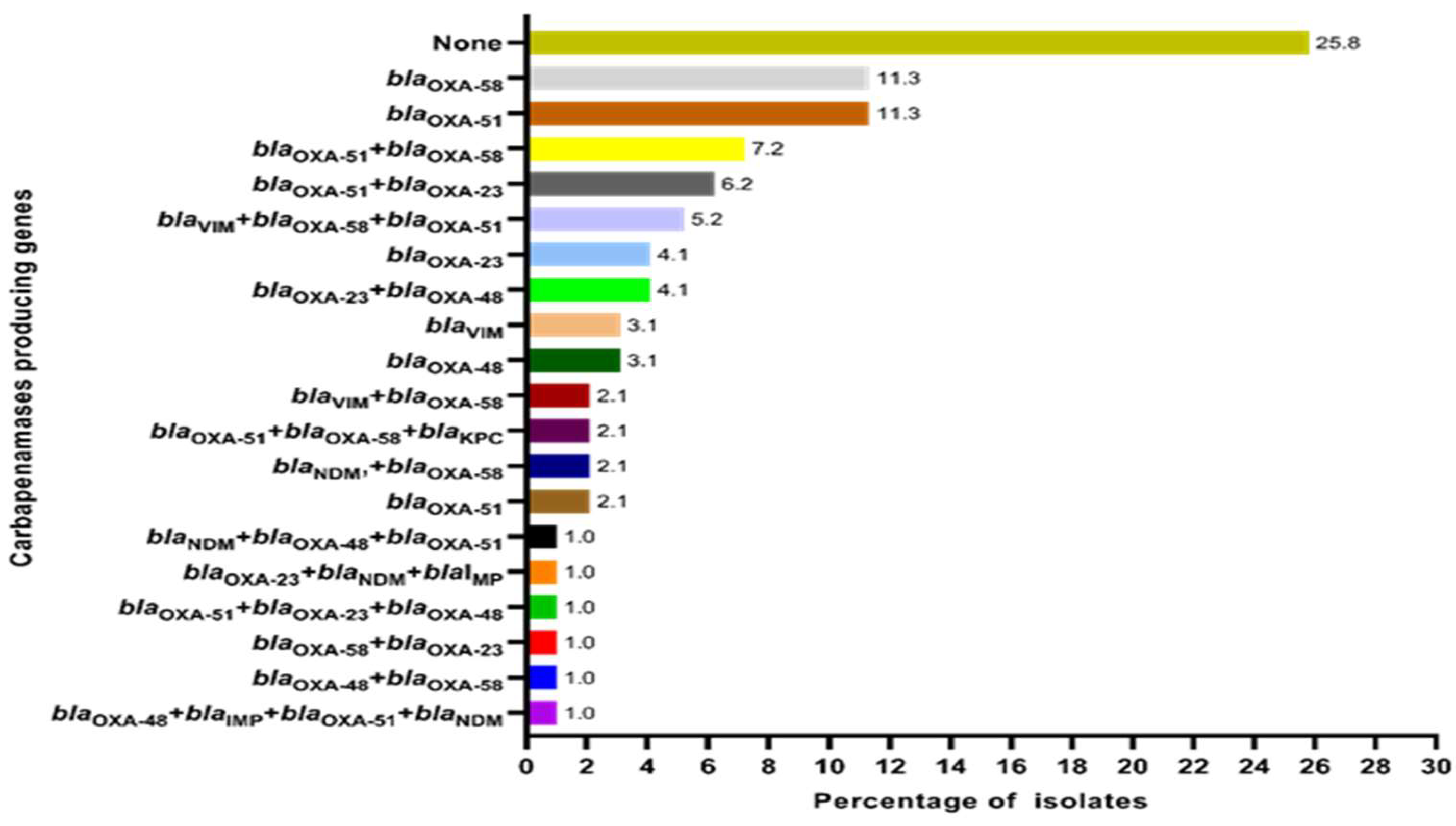

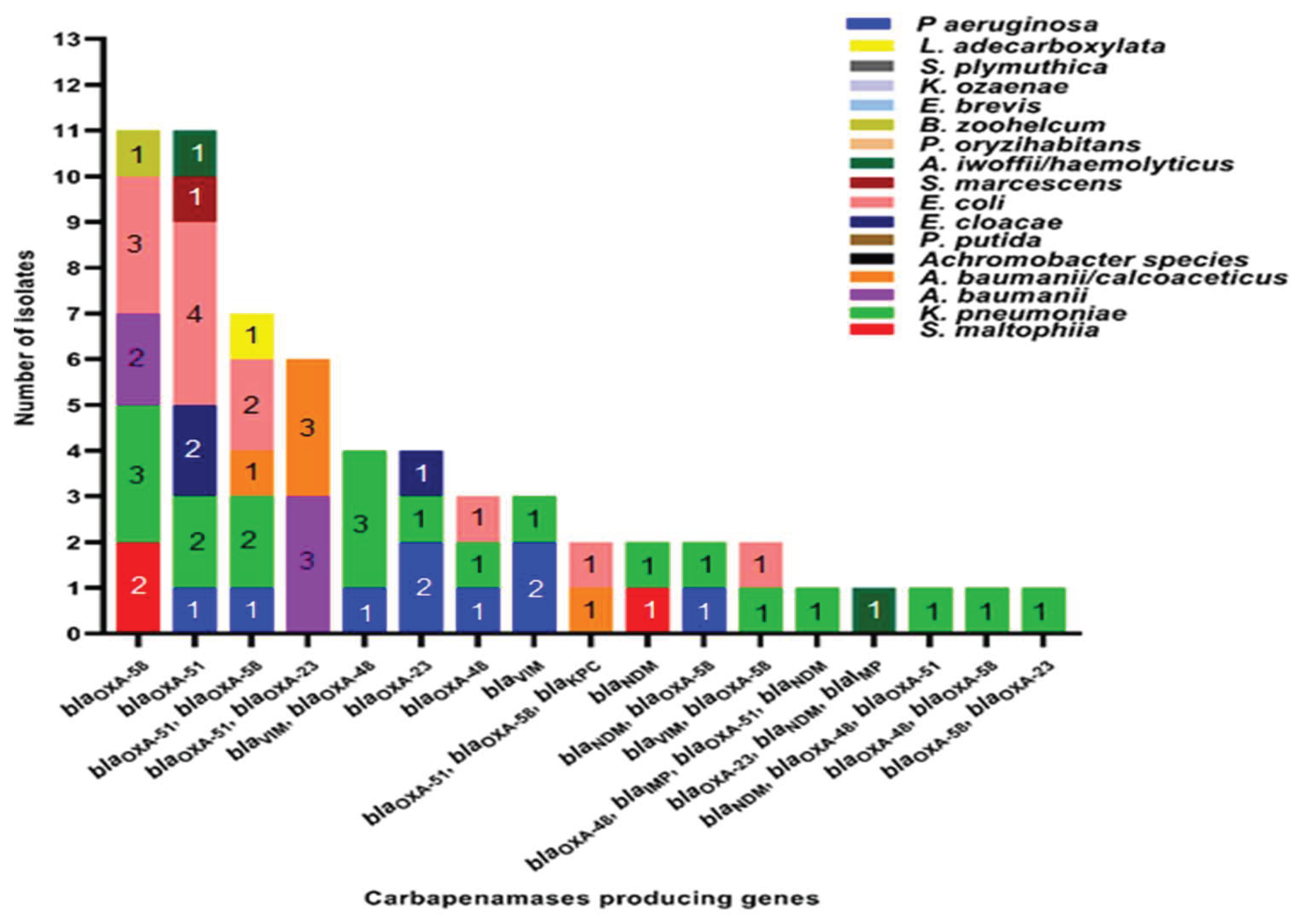

2.2. Distribution of Carbapenemase-Encoding Genes in the Study Sample

2.3. Demographic Characteristics Versus Carbapenemase Gene Presence

2.4. Clinical Characteristics Versus Carbapenemase Gene Presence

2.4.1. Type of Current UTI

2.4.2. Antibiotic Usage History

2.4.3. History of Episodes of UTIs in the Past Six Months

| Variables, n (%) | Total (n=97) | CRG present (n=72, %) | CRG absent (n=25, %) | p value | |||

| Demographic factors (n=97) | Age (mean ± SD, years=52.6 ± 22.5) |

0 – 10 | 7 | 6 (85.7 %) | 1 (14.3 %) | 0.634 | |

| 11 – 20 | 4 | 3 (75.0 %) | 1 (25.0 %) | ||||

| 21 – 30 | 6 | 5 (83.3 %) | 1 (16.7 %) | ||||

| 31 – 40 | 8 | 7 (97.5 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | ||||

| 41 – 50 | 11 | 6 (54.5 %) | 5 (45.5 %) | ||||

| 51 – 60 | 17 | 13 (76.5 %) | 4 (23.5 %) | ||||

| 61 - 70 | 21 | 13 (61.9 %) | 8 (38.1 %) | ||||

| 71 – 80 | 19 | 15 (78.94 %) | 4 (21.1 %) | ||||

| 81 – 90 | 3 | 3 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| 91 - 100 | 1 | 1 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 50 | 38 (76.0 %) | 12 (24.0 %) | 0.680 | ||

| Female | 47 | 34 (72.3 %) | 13 (27.7 %) | ||||

| Education level | Primary | 23 | 19 (82.6 %) | 4 (17.4 %) | 0.034* | ||

| Secondary | 50 | 31 (62.0 %) | 19 (38.0 %) | ||||

| Higher education | 21 | 19 (90.5 %) | 2 99.5 %) | ||||

| No schooling | 3 | 3 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 25 | 19 (76.0 %) | 6 (24.0 %) | 0.680 | ||

| Retired | 4 | 2 (50.0 %) | 2 (50.0 %) | ||||

| Unskilled worker | 10 | 7 (70.0 %) | 3 (30.0 %) | ||||

| Skilled worker | 46 | 34 (73.9 %) | 12 (23.1 %) | ||||

| Professional or managerial | 7 | 5 (71.4 %) | 2 (28.6 %) | ||||

| Other | 5 | 5 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) | ||||

| Clinical presentation and history related factors (n=97) | Type of current urinary tract infection | Uncomplicated cystitis | 4 | 4 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.415 | |

| Complicated cystitis | 16 | 13 (81.3 %) | 3 (18.8 %) | ||||

| Uncomplicated pyelonephritis | 2 | 2 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| Complicated pyelonephritis | 30 | 23 (76.7 %) | 7 (23.3 %) | ||||

| Other | 45 | 30 (66.7 %) | 15 (33.3 %) | ||||

| Outpatient antibiotic treatment prior to admission for the current illness | Yes | 95 | 70 (73.7 %) | 25 (26.3 %) | 0.400 | ||

| No | 2 | 2 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| History of episodes of UTI in last 6 months | None | 19 | 15 (78.9 %) | 4 (21.1 %) | 0.593 | ||

| One | 11 | 10 (90.9 %) | 1 (9.1 %) | ||||

| Two | 13 | 10 (76.9 %) | 3 (23.1 %) | ||||

| Three | 13 | 9 (69.2 %) | 4 (30.7 %) | ||||

| More than three | 41 | 28 (68.3 %) | 13 (31.7 %) | ||||

| Clinical outcome assessment during hospital stay (n=97) | |||||||

| Clinical improvement during hospital stay | Clinical improvement at day 3 of treatment | Yes | 23 | 18 (78.3 %) | 5 (21.7 %) | 0.613 | |

| No | 74 | 54 (72.9 %) | 20 (27.0 %) | ||||

| Clinical improvement on day 5 treatment | Yes | 43 | 34 (79.1 %) | 9 (20.9 %) | 0.459 | ||

| No | 31 | 22 (70.9 %) | 11 (35.5 %) | ||||

| Clinical improvement at day 7 of treatment | Yes | 28 | 18 (64.3 %) | 10 (35.7 %) | 0.251 | ||

| No | 3 | 3 (50.0 %) | 0 | ||||

| Worsening after day 7 of treatment | Yes | 3 | 3 (100 %) | 0 | 0.402 | ||

| No | 90 | 68 (75.6 %) | 22 (24.4 %) | ||||

| Death | Death during hospital stay | Yes | Due to UTI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.971 |

| Due to other reasons | 4 | 3 (75.0 %) | 1 (25.0 0 %) | ||||

| No | 93 | 69 (74.2 %) | 24 (25.8 %) | ||||

| Clinical outcome assessment following hospital discharge (n=93) | |||||||

| UTI symptom recurrence following hospital discharge | UTI symptom recurrence within 30 days of infection | Yes | 33 | 25 (75.8 %) | 8 (24.2 %) | 0.761 | |

| No | 60 | 47 (78.3 %) | 13 (21.7 %) | ||||

| UTI symptom recurrence within 30-60 days of infection | Yes | 24 | 21 (87.5 %) | 3 (12.5 %) | 0.288 | ||

| No | 69 | 51 (73.9 %) | 18 (26.1 %) | ||||

| UTI symptom recurrence within 60-90 days of infection | Yes | 12 | 8 (66.7 %) | 4 (33.3 %) | 0.260 | ||

| No | 81 | 64 (79.0 %) | 17 (20.9 %) | ||||

| OPD treatment for UTI following hospital discharge | OPD treatment for UTI within 30 days of infection | Yes | 19 | 15 (78.9 %) | 4 (21.1 %) | 0.591 | |

| No | 74 | 57 (77.0 %) | 17 (22.9 %) | ||||

| OPD treatment for UTI with 30-60 days | Yes | 11 | 8 (72.2 %) | 3 (27.3 %) | 0.904 | ||

| No | 82 | 64 (78.1 %) | 18 (21.9 %) | ||||

| OPD treatment within 60-90 days for UTI infection | Yes | 6 | 3 (50.0 %) | 3 (50.0 %) | 0.161 | ||

| No | 87 | 69 (79.3 %) | 18 (20.7 %) | ||||

| Readmissions due to UTI during three months | Hospital admission due to UTIs within 30 days of infection | Yes | Ward admission | 26 | 19 (73.1 %) | 7 (26.9 %) | 0.699 |

| ICU admission | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| No | 67 | 53 (79.1 %) | 14 (20.9 %) | ||||

| Hospital admission due to UTIs within 30-60 days of infection | Yes | Ward admission | 17 | 15 (88.2 %) | 2 (11.8 %) | 0.223 | |

| ICU admission | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| No | 76 | 57 (75.0 %) | 19 (25.0 %) | ||||

| Hospital admission due to UTIs within 60-90 days of infection | Yes | Ward admission | 6 | 3 (50.0 %) | 3 (50.0 %) | 0.171 | |

| ICU admission | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| No | 87 | 69 (79.3 %) | 18 (20.7 %) | ||||

| Outcome if readmitted due to UTI during three months | If admitted outcome within 30days | Complete recovery | 24 | 18 (75.0 %) | 6 (25.0 %) | 0.310 | |

| Complicated infection | 2 | 0 | 2 (100 %) | ||||

| No hospital admission | 67 | 53 (79.1 %) | 14 (20.9 %) | ||||

| If admitted outcome within 30 to 60 days of infection | Complete recovery | 16 | 14 (87.5 %) | 2 (12.5 %) | 0.525 | ||

| Complicated infection | 1 | 1 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| No hospital admission | 76 | 57 (75.0 %) | 19 (25.0 %) | ||||

| If admitted outcome within 60-90 days of infection | Complete recovery | 6 | 4 (66. 7 %) | 2 (33.3 %) | 0.455 | ||

| Complicated infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| No hospital admission | 87 | 72 (82.8 %) | 15 (17.2 %) | ||||

| Deaths occurred during three mo | Death within 30 days | Yes | Due to UTI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.265 |

| Due to other reasons | 4 | 2 (50.0 %) | 2 (50.0 %) | ||||

| No | 93 | 69 (74.2 %) | 24 (25.8 %) | ||||

| Death within 30-60 days | Yes | Due to UTI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.554 | |

| Due to other reasons | 1 | 1 (100 %) | 0 | ||||

| No | 96 | 71 (74.0 %) | 25 (26.0 %) | ||||

| Death within 60-90 nthsdays | Yes | Due to UTI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.554 | |

| Due to other reasons | 1 | 1 (100.0 %) | 0 | ||||

| No | 96 | 71 (74.0 %) | 25 (26.0 %) | ||||

2.4.4. In-Hospital Clinical Improvement with the Presence Carbapenemase Genes

2.4.5. Clinical Improvement Following Hospital Discharge with the Presence of Carbapenemase Genes

2.4.6. Deaths Associated with the Presence of Carbapenemase Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Screening for Carbapenem Resistance in Uropathogens by the Disk Diffusion Test

4.2. Organism Identification and Susceptibility Testing by the BD Phoenix Automated System

4.3. Molecular Characterization of CROs

4.4. Demographics, Clinical Factors and Clinical Outcome Assessment

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABST | Antibiotic susceptibility testing |

| BPH | Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| CFU | Colony forming units |

| CRO | Carbapenem resistant organisms |

| CRE | Carbapenem resistant enterobacteriaceae |

| CLSI | Clinical laboratory standard institute |

| GNB | Gram negative bacteria |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NCI | National cancer institute |

| OPD | Out-patient depatment |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| UHKDU | University hospital, Kotelawala Defence University |

| USA | United states of America |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| WBC | White blood cells |

| WHO | World health organization |

| blaKPC | Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase |

| blaIMP | Imipenemase |

| blaNDM | New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase |

| BlaOXA | Oxacillinase |

| blaVIM | Verona Integron encoding metallo-β-lactamase |

References

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Marra, M.; Zummo, S.; Biondo, C. Urinary Tract Infections: The Current Scenario and Future Prospects. Pathogens. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshamy, A.A.; Aboshanab, K.M. A review on bacterial resistance to carbapenems: Epidemiology, detection and treatment options. Futur Sci OA. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. World Heal Organ. 2013, 43, 348–365. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Diasease Control Prevention, C.D.C. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterals. Centers for Disease Control and prevention. 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cre/about/index.html (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Van, D.; Kaye, S.; Neuner, A.B. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes. J Neurochem. 2015, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Epidemiology and Diagnostics of Carbapenem Resistance in gram-negative Bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2019, 69 (Suppl. 7), S521–S528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, V.D.; Costache, R.C.; Onofrei, P.; Miron, A.; Bandac, C.-A.; Arseni, D.; et al. Urinary Tract Infections with Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Urology Clinic—A Case‒Control Study. Antibiotics. 2024, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girija, S.A.; Priyadharsini, J.V.; Paramasivam, A. Prevalence of carbapenem-hydrolysing OXA-type β-lactamases among Acinetobacter baumannii in patients with severe urinary tract infection. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2020, 67, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, F.; Yazdanpour, Z.; Khademi, F.V.H. Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Metallo-Beta-Lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Med Lab J. 2023, 17, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, G.; De Gaetano, S.; Midiri, A.; Zummo, S.; Biondo, C. The Challenge of Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: “Attack on Titan”. Microorganisms. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan-Aydogan, O.; Alocilja, E.C. A Review of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales and Its Detection Techniques. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Mathai, D.; Bell, J.M.; Jones, R.N.; Mendes, R.E. Early dissemination of NDM-1- and OXA-181-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Indian hospitals: Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2006-2007. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1274–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.M.; Corea, E.; Sanjeewani, A.H.D.; Inglis, T.J.J. Molecular mechanisms of β-lactam resistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumonia from Sri Lanka. J Med Microbiol. 2014, 63 Pt 8, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammour, K.A.; Abu-Farha, R.; Itani, R.; Karout, S.; Allan, A.; Manaseer, Q.; et al. The prevalence of Carbapenem Resistance Gram negative pathogens in a Tertiary Teaching Hospital in Jordan. BMC Infect Dis. 2023, 23, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfa, T.; Mitiku, H.; Edae, M.; Assefa, N. Prevalence and incidence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae colonization: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sys Rev. 2022, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liyanapathirana, V.; Li, C.; Pinto, V.; Hui, M.; Lo, N.; et al. Characterizing mobilized virulence factors and multidrug resistance genes in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Sri Lankan hospital. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tissera, K.; Liyanapathirana, V.; Dissanayake, N.; Pinto, V.; Ekanayake, A.; Tennakoon, M.; et al. Spread of resistant gram negatives in a Sri Lankan intensive care unit. BMC Infect Dis. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilaka, S.H.; Jayatissa, A.H.; Chandrasiri, S.N.; Jayatilleke, K.; Kottahachchi, J. Detection of carbapenemase producing enterobacterales using the Modified Hodge Test from clinical isolates in Colombo South Teaching Hospital and Sri Jayewardenepura General Hospital, Sri Lanka in 2017. Sri Lankan J Infect Dis. 2024, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.M.P.S.C.; Luke, W.A.N.V.; Miththinda, J.K.N.D.; Wickramasinghe, R.D.S.S.; Sebastiampillai, B.S.; Gunathilake, M.P.M.L.; et al. Extended spectrum beta lactamase producing organisms causing urinary tract infections in Sri Lanka and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern –A hospital based cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017, 17, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumudunie, W.G.M.; Wijesooriya, L.I.; Namalie, K.D.; Sunil-Chandra, N.P.; Wijayasinghe, Y.S. Epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Sri Lanka: First evidence of blaKPC harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Infect Public Health. 2020, 13, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suranadee, Y.W.S.; Dissanayake, Y.; Dissanayake, B.M.B.T.; Jayalatharachchi, H.R.; Gamage, S.; Gunasekara, S.P. Gut colonization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among patients with haematological malignancies in National Cancer Institute, Sri Lanka. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2022, 4(Supplement_1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8849380/.

- Suranadee, Y.W.S.; Jyalathacrachchi, H.R.; Gamage, S.G. Occurrence of blaKPC, blaNDM and bla OXA-48 genes among carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in National Cancer Institute, Sri Lanka. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2022;4(Supplement-1):17–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9040066/. [CrossRef]

- Pothoven, R. Management of urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Drug Target Insights. 2023, 17, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirapanmethee, K.; Srisiri-A-nun, T.; Houngsaitong, J.; Montakantikul, P.; Khuntayaporn, P.; Chomnawang, M.T. Prevalence of OXA-type β-lactamase genes among carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates in Thailand. Antibiotics. 2020, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, E.; Al-dughmani, H.; Koura, B.; Bader, M.; Deen MAl Bueid, A.; et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenem resistant Enterobacterales in thirteen tertiary care hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2021, 41, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, M.G.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Mohamed, N.; Hermsen, E.D.; Kamat, S.; Townsend, A.; et al. Global trends in carbapenem- and difficult-to-treat-resistance among World Health Organization priority bacterial pathogens: ATLAS surveillance program 2018–2022. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2024, 37, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, H.S.; Elhag, K.M.; Mahgoub, E.; Altayb, H.N.; Ntoumi, F.; Elton, L.; et al. Detection and characterization of carbapenem resistant Gram-negative bacilli isolates recovered from hospitalized patients at Soba University Hospital, Sudan. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Tsai, I.T.; Lai, C.H.; Lin, K.H.; Hsu, Y.C. Risk Factors and Outcomes of Community-Acquired Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in Elderly Patients. Antibiotics. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, F.; Donkor, E. Carbapenem Resistance: A Review. Med Sci. 2017, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, K.; Nurjadi, D.; Heeg, K.; Frede, A.; Dalpke, A.H.; Boutin, S. Molecular Detection of Carbapenemases in Enterobacterales : A Comparison of Real-Time Multiplex PCR and Whole-Genome Sequencing. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, M.; Parvizi, E.; Navidifar, T.; Bostanghadiri, N.; Mofid, M.; Golab, N.; et al. Geographical mapping and temporal trends of Acinetobacter baumannii carbapenem resistance: A comprehensive meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, N.A. Phenotype-genotype correlations among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales recovered from four Egyptian hospitals with the report of SPM carbapenemase. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Q.; Sri La Sri Ponnampalavanar, S.; Chong, C.W.; Karunakaran, R.; Vellasamy, K.M.; Abdul Jabar, K.; et al. Characterization of non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae based on their clinical and molecular profile in Malaysia. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarasamy, K.K.; Toleman, M.A.; Walsh, T.R.; Bagaria, J.; Butt, F.; Balakrishnan, R.; et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: A molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010, 10, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Khalid, S.; Ali, S.M.; Khan, A.U. Occurrence of blaNDM variants among enterobacteriaceae from a neonatal intensive care unit in a Northern India hospital. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Xu, G.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. Molecular epidemiology and drug-resistant mechanism in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from paediatric patients in Shanghai, China. PLoS One. 2018, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Chen, R.; Qiao, J.; Ge, H.; Fang, L.; Liu, R.; et al. Distribution and molecular characterization of carbapenemase - producing gram - negative bacteria in Henan, China. Sci Rep. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Albadery, A.; Shakir Mahdi Al-Amara, S.; Abd-Al-Ridha Al-Abdullah, A. Phenotyping and Genotyping Evaluation of E. coli Produces Carbapenemase Isolated from Cancer Patients in Al-Basrah, Iraq. Arch Razi Inst. 2023, 78, 823–829. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, B.; Haque, A.; Qasim, M.; Ali, A.; Sarwar, Y. High prevalence of extensively drug resistant and extended spectrum beta lactamases (ESBLs) producing uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from Faisalabad, Pakistan. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allel, K.; García, P.; Labarca, J.; Munita, J.M.; Rendic, M.; Undurraga, E.A. Socioeconomic factors associated with antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli in Chilean hospitals (2008-2017). Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Heal. 2020, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasi, P.; Jamadarakhani, Siddappa; Rajani, KR.; Sujatha, M. Awareness Regarding the Disease and Its Prevention amongst Women with Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection: A Cohort Study. Kerala Surgica Journal 2024, 30, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Otaigbe, I.I.; Elikwu, C.J. Drivers of inappropriate antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2023, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihombing, B.; Bhatia, R.; Srivastava, R.; Aditama, T.Y.; Laxminarayan, R.; Rijal, S. Response to antimicrobial resistance in South‒East Asia Region. Lancet Reg Heal - Southeast Asia. 2023, 18, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, T.; Wijayaratne, G.B.; Dabrera, T.M.; Drew, R.J.; Nagahawatte, A.; Bodinayake, C.K.; et al. Point-prevalence study of antimicrobial use in public hospitals in southern Sri Lanka identifies opportunities for improving prescribing practices. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, P.D.; Simner, P.J. Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms from clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, P.; Sagar, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, D.; Lalwani, S.; et al. Does the presence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase and New Delhi metallo - β - lactamase - 1 genes in pathogens lead to fatal outcome ? Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016, 34, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Fang, Y.; Mu, X.; Xiao, N.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z. Risk Factors for and Clinical Outcomes of Nosocomial Infections: A Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Hospital in Beijing, China. Infect Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudpong, K.; Pattharachayakul, S.; Santimaleeworagun, W.; Nwabor, O.F.; Laohaprertthisan, V.; Hortiwakul, T.; et al. Association Between Types of Carbapenemase and Clinical Outcomes of Infection Due to Carbapenem Resistance Enterobacterales. Infect Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 3025–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, R.; Paruk, F.; Becker, P.; Neuhoff, M.; Chausse, J.; Said, M. Clinical utility of the BioFire FilmArray Blood Culture Identification panel in the adjustment of empiric antimicrobial therapy in the critically ill septic patient. PLoS One. 2021, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakizaki, N.; Asai, K.; Kuroda, M.; Watanabe, R.; Kujiraoka, M.; Sekizuka, T.; et al. Rapid identification of bacteria using a multiplex polymerase chain reaction system for acute abdominal infections. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Paterson, D.L. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015, 36, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI M100 for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33rd ed. CLSI supplement M100. Vol. 40, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institue. 2023. 32–41 p.

| Carbapenemases encoded by gene/s | Age categories in years | Gender | ||||||||||

| 0-10 | 11-20 | 21-30 | 31-40 | 41-50 | 51-60 | 61-70 | 71-80 | 81-90 | 91-100 | Males | Females | |

| blaNDM | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| blaVIM | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| blaOXA-51 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 8 |

| blaOXA-23 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| blaOXA-48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| blaOXA-58 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 |

| blaNDM, blaOXA-58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| blaVIM, blaOXA-48 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| blaVIM, blaOXA-58 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| blaOXA-51, blaOXA-23 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| blaOXA-51, blaOXA-58 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| blaOXA-48, blaOXA-58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| blaOXA-48, blaOXA-23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| blaOXA-58, blaOXA-23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| blaOXA-51, blaOXA-23, blaOXA-48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| blaVIM, blaOXA-58, blaOXA-51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| blaOXA-51, blaOXA-58, blaKPC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| blaOXA-23, blaNDM, blaIMP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| blaNDM, blaOXA-48, blaOXA-51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| blaOXA-48, blaOXA-51, blaIMP, blaNDM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| No carbapenemase encoding genes detected | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 13 |

| Total | 7 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 17 | 21 | 19 | 3 | 1 | 50 | 47 |

| Period of death | Gender | Age (years) | Name of the CRO present | Carbapenemase genes present |

| During the hospital stay (n=4) | Female | 45 | K. pneumoniae | None |

| Male | 49 | A. baumannii | blaOXA-51+blaOXA-23 | |

| Female | 69 | K. pneumoniae | blaOXA-48 | |

| Female | 24 | K. pneumoniae | blaOXA-51 | |

| Within 30 days of discharge (n=4) |

Male | 65 | P. aeruginosa | None |

| Male | 79 | S. marcescens | blaOXA-51 | |

| Female | 80 | K. pneumoniae | None | |

| Female | 80 | K. pneumoniae | blaOXA-51 | |

| Within 30-60 days of discharge (n=1) | Male | 82 | A. baumannii/calcoaceticus complex | blaKPC+blaOXA-51+blaOXA-58 |

| Within 60-90 days of discharge (n=1) | Female | 70 | E. coli | blaOXA-51+blaOXA-58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).