1. Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are a well-known complication of patient affected by Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [

1], and chemotherapy-related profound neutropenia is nowadays still considered the major risk factor for their development [

2]. The expected incidence of probable/proven IFIs changes during treatment phase, and is estimated to be about 10% during remission induction chemotherapy [

3], and to be decreased to a rate of 1.5-2.5% during consolidation [

4] chemotherapy. Therefore, induction chemotherapy for AML remains the critical period in which the burden of IFIs is still of great concern, with a potential negative impact on outcome [

5], and a mortality risk still accounted up to 30% [

6].

A reduction in IFIs incidence and mortality has been reported after introduction of systematic antifungal prophylaxis, as shown in several studies [

7,

8] and meta-analysis [

9,

10], particularly with the advent of posaconazole [

11]. Posaconazole is an oral triazolic agent, nowadays formally recommended for primary antifungal prophylaxis (PAP) during induction chemotherapy for AML, that shows a peculiar strong activity as CYP3A4 inhibitor [

12]. As oral drug, its administration can be limited by patient conditions such as intercurrent chemotherapy-related gastrointestinal mucositis [

13], or poor performance status given by disease or treatment complications. Moreover, introduction in AML practice of new-targeted drugs able to interact with CYP3A4, such as Venetoclax [

14] and Midostaurin [

15], recently posed some issues on use of posaconazole in AML patients. For Venetoclax a dose reduction by 50% to 75% during coadministration with posaconazole has been suggested from an EHA (European Hematology Association) -experts panel [

16], based mainly on pharmacokinetics studies [

17]. For Midostaurin conflicting recommendations on which antifungal agent coadminister during induction chemotherapy are available, bringing to a real clinical dilemma [

18] on which PAP to choose in this situation. Therefore, alternative antifungal prophylactic strategies in patients treated with Midostaurin or VEN-based regimens, or in patients unable to assume oral drugs due to impaired clinical conditions, remain desirable and warranted.

Caspofungin is a member of echinocandin family that inhibits the enzyme 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase, disrupting fungal cell-wall synthesis. It has a broad spectrum of activity against Candida and Aspergillus species [

19] and is known for its favorable safety profile, largely given by minimal drug–drug interactions [

20]. Importantly, caspofungin is administered intravenously, which ensures consistent plasma levels regardless of gastrointestinal function or patient conditions, with efficacy not compromised by mucositis, food effects, or concurrent medications that affect drug metabolism. In prospective clinical trials caspofungin showed to be effective and safe for the treatment of IFIs in critically ill patients [

21], and in patients with hematological cancer [

22,

23]. Moreover, good results have been observed in AML both as empirical therapy during febrile neutropenia [

24], and as primary prophylaxis in patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [

25]. Finally, two randomized trials and one methanalysis showed good efficacy of Caspofungin when used preemptively [

26] in antifungal treatment of high-risk neutropenic patients with AML, when used as prophylaxis [

27] of IFIs among children and young adults with acute leukemia, and when compared with other azoles in neutropenic AML patients [

28]. Reflecting this growing evidence, clinical guidelines [

29,

30] have started to endorse echinocandins for antifungal prophylaxis, and in the latest ECIL-10 (European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia) recommendations [

31] for AML, echinocandins were upgraded from a previous C-II to a B-II level of evidence for PAP. Consequently, caspofungin and other echinocandins are now considered suitable alternative agents for primary prophylaxis against IFIs in AML.

To further clarify the role of caspofungin in AML, we conducted a real-life retrospective study evaluating the incidence of IFIs in patients who received caspofungin in place of posaconazole as PAP.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A real-life retrospective monocentric study was conducted at the Hematology Division of the Federico II University Medical School of Naples, Italy in patients who received antifungal prophylaxis in the context of the first cycle of chemotherapy for AML. The primary objective of the study was to document the incidence of possible/probable/proven IFIs occurring in AML patients receiving caspofungin instead of posaconazole as PAP to avoid drug-drug interaction (if treated with intensive chemotherapy and Midostaurin, or with a Venetoclax-based regimen), or due to patient conditions that impaired oral drugs absumption. The secondary objectives were to assess the safety of the different prophylaxis strategies, and to identify any potential risk factor correlated with IFIs diagnosis. The tertiary objective of the study was to evaluate the impact on Overall Survival (OS) of IFI diagnosis, type of antifungal prophylaxis, patients demographics and disease related-factors.

2.2. Definitions

IFIs were diagnosed according to EORTC/MSG updated criteria [

32] and categorized as possible, probable and proven. The classification of AML diagnosis was made according WHO [

33] and ICC2022 [

34] criteria, while classification of AML risk and response criteria were made according to ELN 2022 risk stratification [

35]. The duration of neutropenia was defined as the number of days with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) below 500/mmc.

2.3. Diagnostic Work-Up

In all patients planned to receive AML treatment, galactomann antigen (GM) and Beta-D-glucan (BD) detection test was performed once weekly, and twice weekly in patient with fever. In neutropenic patients, antibacterial prophylaxis consisted in levofloxacin 500 mg once daily was administered in all patients. Topical antifungal therapy with polyenes agents, and antiviral prophylaxis with acyclovir were also used depending on patient characteristics. At fever onset, patients were tested with blood cultures and chest X-ray. Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment was started, and escalated in case of persistence or recurrence of fever. Moreover, a CT scan was performed in case of persisting ≥72 h fever, or in case of recurring fever, particularly in patients with suggestive infective symptoms (i.e. dyspnea or dyarrea). Switch from caspofungin to a systemic antifungal therapy with other antifungal agents was considered after multidisciplinary discussion with the infectious disease team.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables of interest. Categorical variables were summarized through frequencies and percentage values, while continuous variables through median values and their relative range. Comparisons between groups were tested by Chi-square test and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U-test. Correlation analysis was performed by Spearman's rank correlation ρ testing, while univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate impact of covariates on categorical events. Overall Survival (OS) analysis was carried out by the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method and by Cox proportional hazard regression models. OS was defined as the time from the first diagnosis to the death of the patient or, if censored, last contact with the patient. The log-rank test was used to show any statistically significant difference between subgroups. For estimating risk of specific events, odd ratios (OR) and hazard risks (HR), with relative 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated for each covariate, using the logistic regression model or the cox analysis. In multivariate models, enter method analysis including all clinically relevant variables was used to evaluate interaction between covariates. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in results. Statistical analyses were carried out using R package software (R Statistical Software v4.5.0; R Core Team 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Data from 75 patients [female 40 (53%); 35 male (47%)] treated for AML at the Hematology Division of Federico II University Hospital from January 2021 through January 2025 were retrospectively collected and analyzed. Median age was 61 years (range, 26–75), with no significant differences in the male/female ratio. Median number of comorbidities per patient was of 1 (range 0-4), with type II diabetes (16 patients, 21%) and cardiovascular (12 patients, 16%) as the more frequent comorbidities. According to WHO2022 and ICC2022 classifications, diagnosis was of AML with defined genetic abnormalities in 40 (53.3%) cases, AML with myelodysplastic syndrome gene mutations in 12 (16%) cases, AML defined by differentiation in 8 (11%) cases, AML secondary to previous myeloproliferative neoplams in 7 (9,3%) cases, therapy-related AML in 3 (4%) cases, and finally MDS/AML with TP53 mutation in 5 (6,7%) cases. According to ELN2022 classification, 28 (37%) patients had a low-risk disease, 25 (33%) patients an intermediate-risk disease, and 22 (29%) patients an high-risk disease. Looking at NPM1 and FLT3 status, 26 (34%) patients were NPM1 mutated, and 19 (25%) patients FLT3 mutated. AML chemotherapy consisted in IDA-FLAG in 4 (5%) patients, CPX-352 in 11 (14%) patients, 3+7 in 16 (21%) patients, 3+7+gemtuzumab (3+7+GO) in 15 (20%) patients, 3+7+midostaurin (3+7+Mido) in 12 (16%) patients, hypomethilating agents + Venetoclax (HMA/Ven) in 17 (24%) patients (4 decitabine, 13 azacitidine). Post-chemotherapy neutropenia was observed in all patients, with a median duration of 22 days (range, 12 – 131).

3.2. PAP Strategy

Antifungal prophylaxis was delivered during first cycle of chemotherapy in all patients. Standard prophylaxis with Posaconazole was used in 42 patients (56%), while Caspofungin was used as antifungal prophylaxis in 33 (44%) patients. Caspofungin was the first antifungal of choice to avoid drug-to-drug interactions with Venetoclax or Midostaurin in 20 patients (61%), while in the other 13 patients (39%) caspofungin was preferred to posaconazole as PAP mainly due to patient conditions that impaired oral posaconazole administration (i.e. deteriorated performance status, oral mucositis and gastrointestinal symptoms). According to drug schedules, posaconazole was administered orally at 300 mg once daily, with the first two doses given every 12 hours, while caspofungin was given intravenously (IV) 50 mg once daily, with the first dose at 70 mg. Median duration of PAP was of 22 days (Range: 13 – 68) for posaconazole, of 26 days (Range: 12 – 131) for caspofungin.

3.3. Characteristics of Posa-Group Versus Caspo-Group

No significant differences in terms of demographics (Age, sex, burden of comorbidities, most prevalent comorbidity), AML type and ELN2022 risk, presence of

NPM1 or

FLT3 mutation, and duration of neutropenia were observed across the two groups (Caspofungin

vs. Posaconazole prophylaxis). As expected by the study design, an higher proportion of

FLT3 patients were treated with midostaurin (

P<0.005) in the caspofungin group, while a significantly higher proportion of patients in the posaconazole group received alternative induction regimens such as 3+7

±GO (

P<0.001). Patient’s characteristics with significant differences between the two prophylaxis groups are summarized in

Table 1.

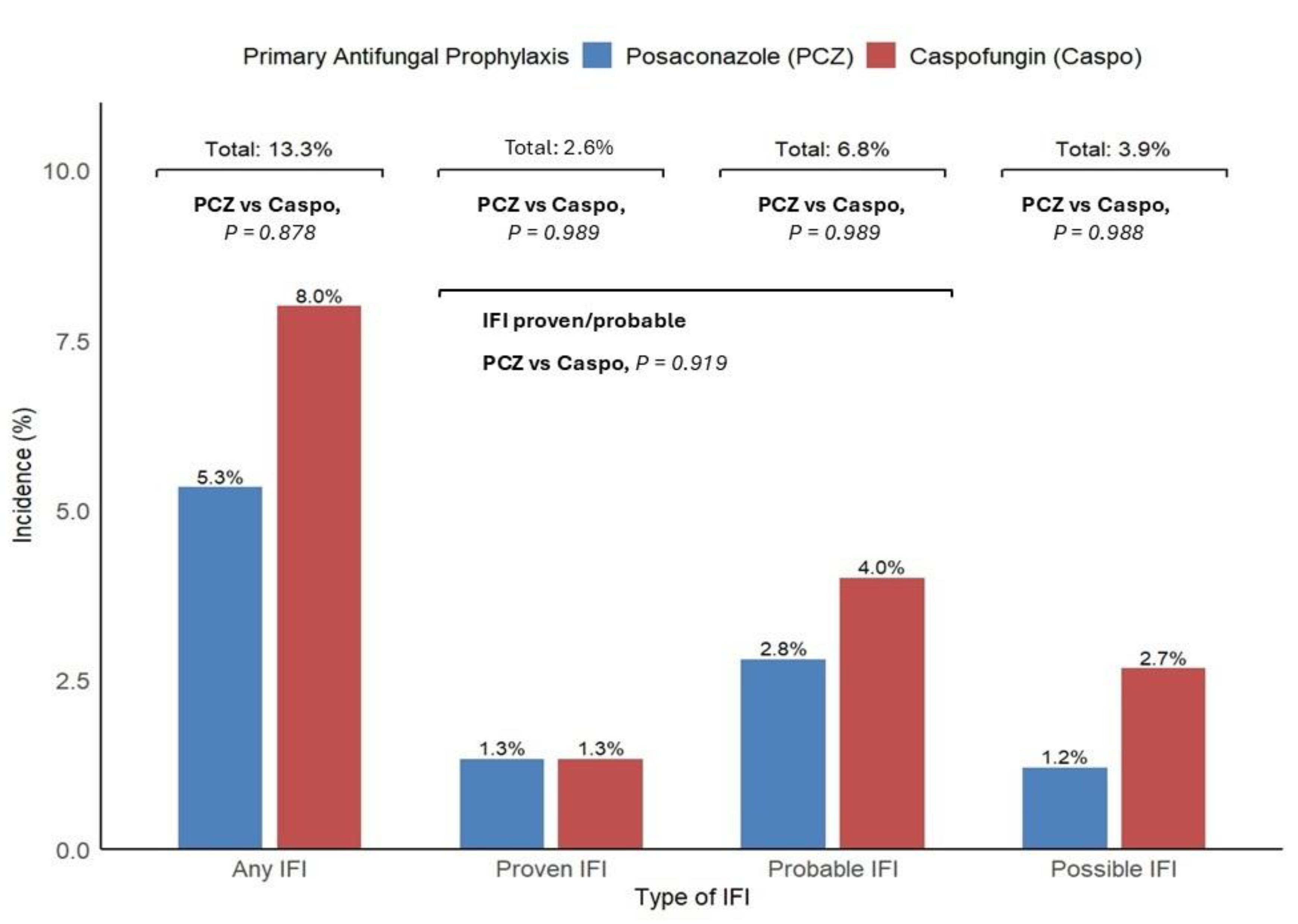

3.4. IFIs Incidence, Association with Type of Prophylaxis, Clinical Course and Safety

A total of 10 episodes of IFI were diagnosed in the study, for an overall incidence of 13,3%. IFI diagnosis occurred after intensive 3+7

±Midostaurin chemotherapy in 6 cases, and after Venetoclax-based therapy in the remaining 4. According to EORTC/MSG criteria, IFIs were classifiable as proven, probable and possible in 2 (2.6%), 5 (6.8%) and 3 (3.9%) cases respectively, for an incidence of 9,4% for proven and probable infections. The median time from chemotherapy start to diagnosis of IFI was of 25 (range 18 – 53) days. When IFIs were grouped according to antifungal prophylaxis, an increased but not significant number of IFIs were observed in the caspofungin prophylaxis group (6

vs. 4;

P= 0.878). Even when only proven and probable IFIs were considered, the difference between the two prophylaxis groups remained not significant (5

vs. 3;

P= 0.919), but still with a majority of cases in the caspofungin group (

Figure 1).

Diagnosis of possible IFIs was made in two neutropenic patients in the caspofungin group due to persistent fever with clinical respiratory symptoms, absence of specific microbiological isolates, and positive CT scan showing lung macronodules, finally compatible with possible lung aspergillosis. In one neutropenic patient in the posaconazole group, diagnosis of possible candidiasis was made due to liver and spleen micronodules with target-signs detected by ultrasound, radiologically compatible with mycotic localization, in absence of significant BD or GM serum-level increase, and without any microbiological isolates. In 5 cases (3 in Caspofungin group, and 2 in Posaconazole group), diagnosis of IFI was compatible with probable lung aspergillosis, with typical radiological finding by lung CT scan and serum GM elevation (median GM value 1.1; range 0.93 – 2.28). Overall lung remained the main site of infection in caspofungin group, with 5 (71%) cases recorded (3 probable + 2 possible IFIs). Geotrichum spp. and Saprochaete capitata were responsible for the two cases of proven IFI. Geotrichum was isolated from blood coltures of a patient in the caspofungin prophylaxis group. After switching to systemic antifungal therapy, an head CT scan performed for neurological symptoms showed radiological findings compatible with fungal CNS disease. Saprochaete capitata was isolated from blood coltures and liver biopsy of a patient in the posaconazole prophylaxis group. In both patients, these fungal infections were resistant to second line therapy with liposomal B amphotericin (L-AmB), and finally determined patient death, for a global fungal death rate of 2% (2/75).

In all other cases of probable/possible IFIs, an antifungal switch therapy was performed. Isavuconazole was the drug of choice in 4 cases of probable aspergillosis. Only one patient with probable lung aspergillosis was treated with L-AmB, and L-AmB was used in the other 3 cases with possible IFIs. Radiologically documented response to newer antifungal therapy was observed in 7 of 10 (70%) cases, and allowed prosecution of AML treatment. Overall PAP was safe and well tolerated with both drugs. No particular toxicities were observed with caspofungin, while grade 1-2 liver enzymes elevations, not determining drug suspension, was observed in 15(33%) patients receiving posaconazole.

3.5. Risk Factors Associated with IFIs Incidence and Survival Analysis

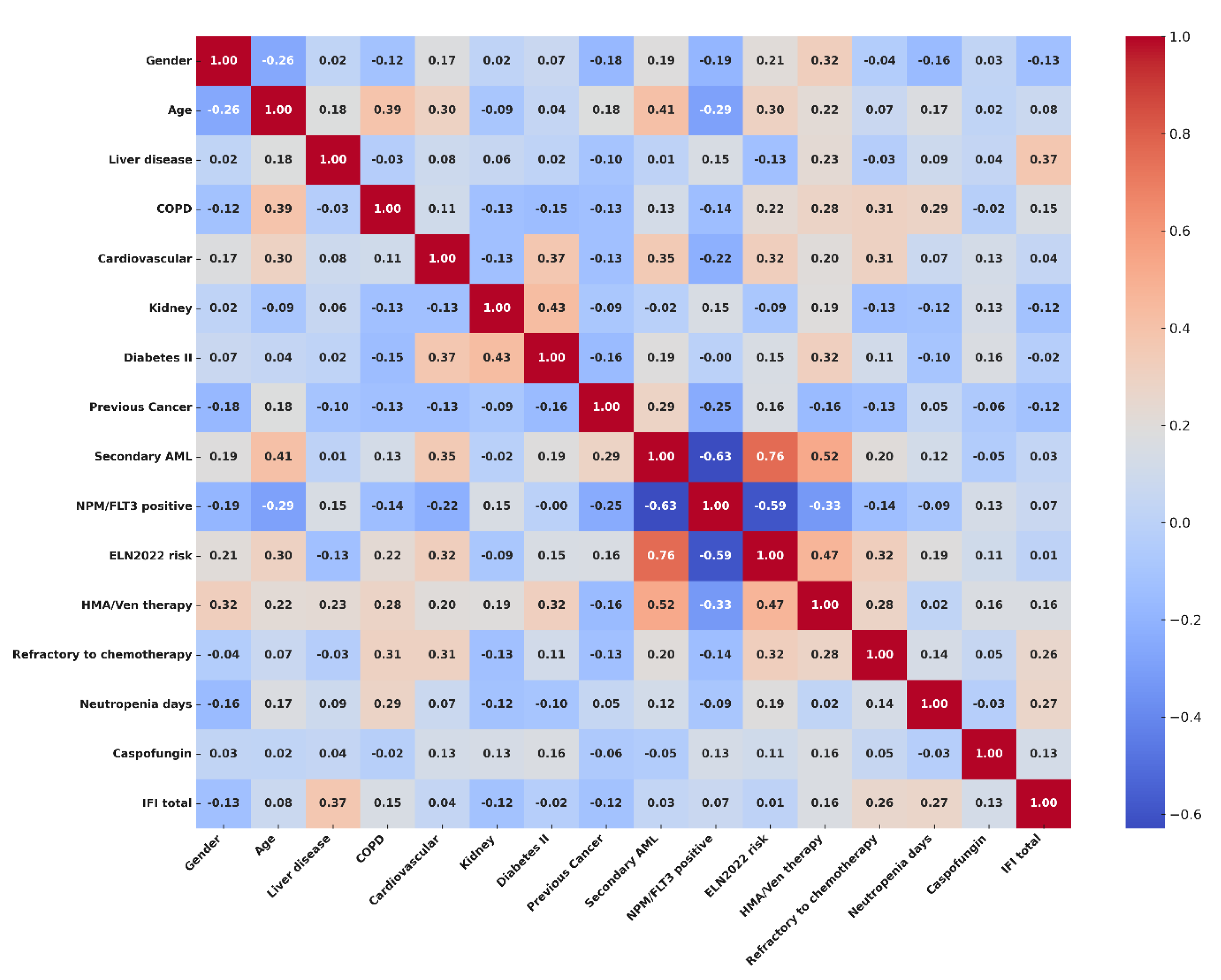

To explore the risk factors potentially related with incidence of IFI in our population, we performed an exploratory analysis with Spearman's rank correlation test. Categorical variables included in the analysis were: gender (Male vs Female), presence or not of clinically significant comorbidities such as liver disease (i.e. severe liver steatosis), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd), cardiovascular comorbidity, kidney function impairment (i.e. moderate to severe renal failure), type II diabetes, history of previous cancer (Yes vs No), diagnosis according to WHO and ICC2022 (Comparing Secondary AML vs De Novo AML), positivity for NPM or FLT3 mutation (positive vs negative), ELN2022 risk (High vs Low/Intermediate), type of chemotherapy (HMA/VEN vs Intensive regimens) and disease status after treatment (Refractory vs Responding disease). Age of the patients, and number of days of severe neutropenia were included in the model as continuous variables. Strong positive correlation was found with liver disease (ρ= 0.373; CI95%, 0.033-0.676), days of severe neutropenia (ρ= 0.257; CI95%, 0.087-0.428) and disease status (ρ= 0.269; CI95%, 0.064-0.539) after chemotherapy. Mild correlation with IFIs was observed for presence of COPD (ρ= 0.150; CI95%, 0.122-0.414), exposure to a HMA/Ven regimen (ρ= 0.162; CI95%, 0.087-0.421), and usage of Caspofungin as antifungal prophylaxis (ρ= 0.126; CI95%-0.131-0.360). Complete results of correlation analysis are available in supplemental results (S1), and a correlation matrix showing interaction between covariates and correlation with IFIs is visualized in

Figure 2.

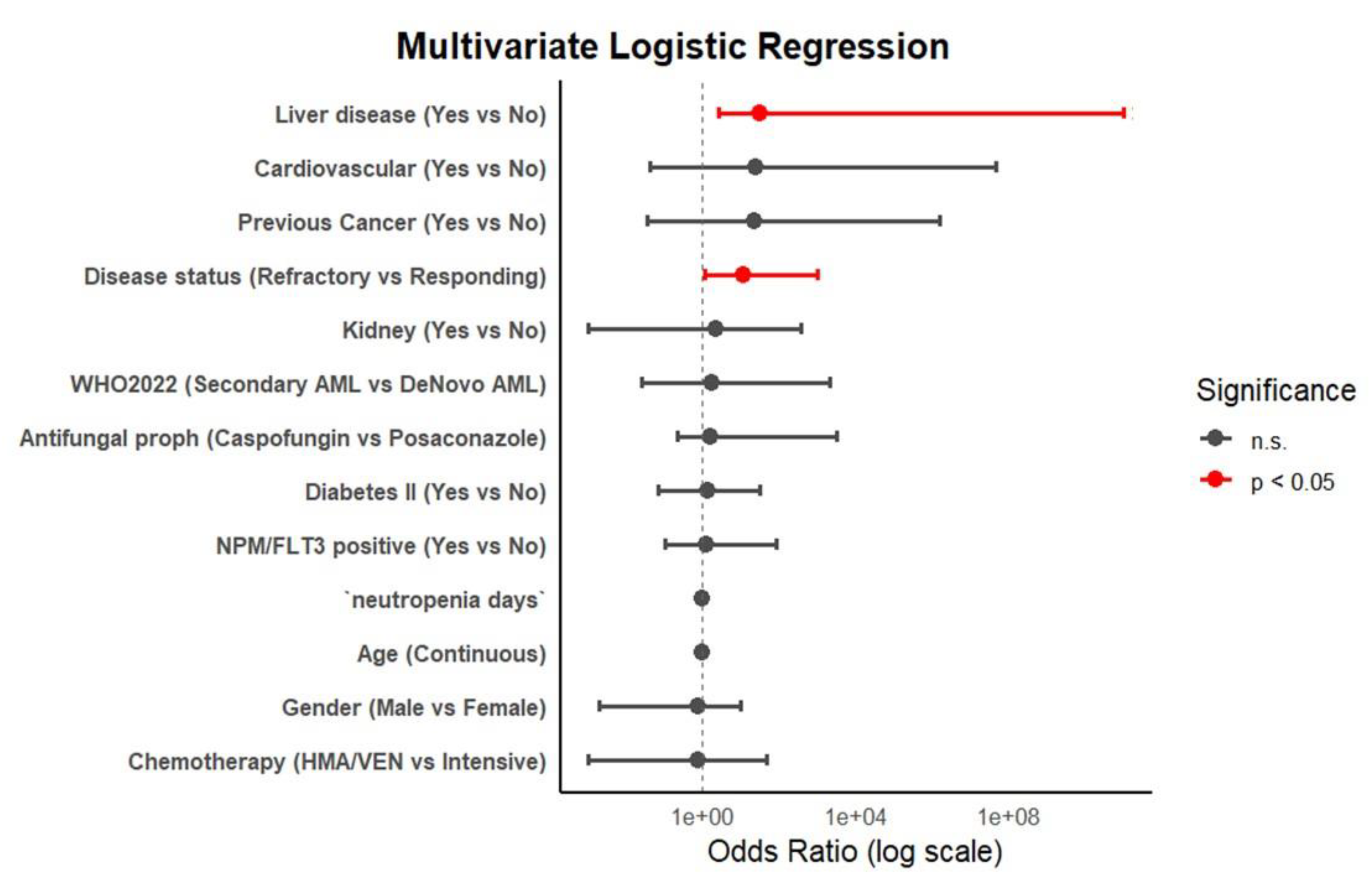

To further assess the possible independent association of clinical factors with diagnosis of IFI, and to assess the interactions between covariates, we performed an univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. An initial exploratory analysis who took into account all the variables, with incidence of proven, probable and possible IFI is reported in supplemental results (S2). Considering sample dimensions, and number of events, we then focused our analysis only on the group of proven and possible IFIs. In the univariate model, only liver disease (p=0.01; CI95%, 1.53-56.79), duration of neutropenia, and refractory disease after chemotherapy (p=0.05; CI95%, 0.86-26.17) showed to be statistically significant. However, in multivariate logistic analysis, only liver disease (OR=30.4; p=0.004) and refractory disease status after chemotherapy (OR=11.9; p=0.003) were confirmed as significant factors in IFIs incidence. Impact of COPD, exposure to an HMA/Ven regimen, and usage of Caspofungin were not confirmed in univariate nor in multivariate analysis (See supplemental S3 for complete results). Forrest plot analysis visualizing multivariate logistic regression results is available in

Figure 3.

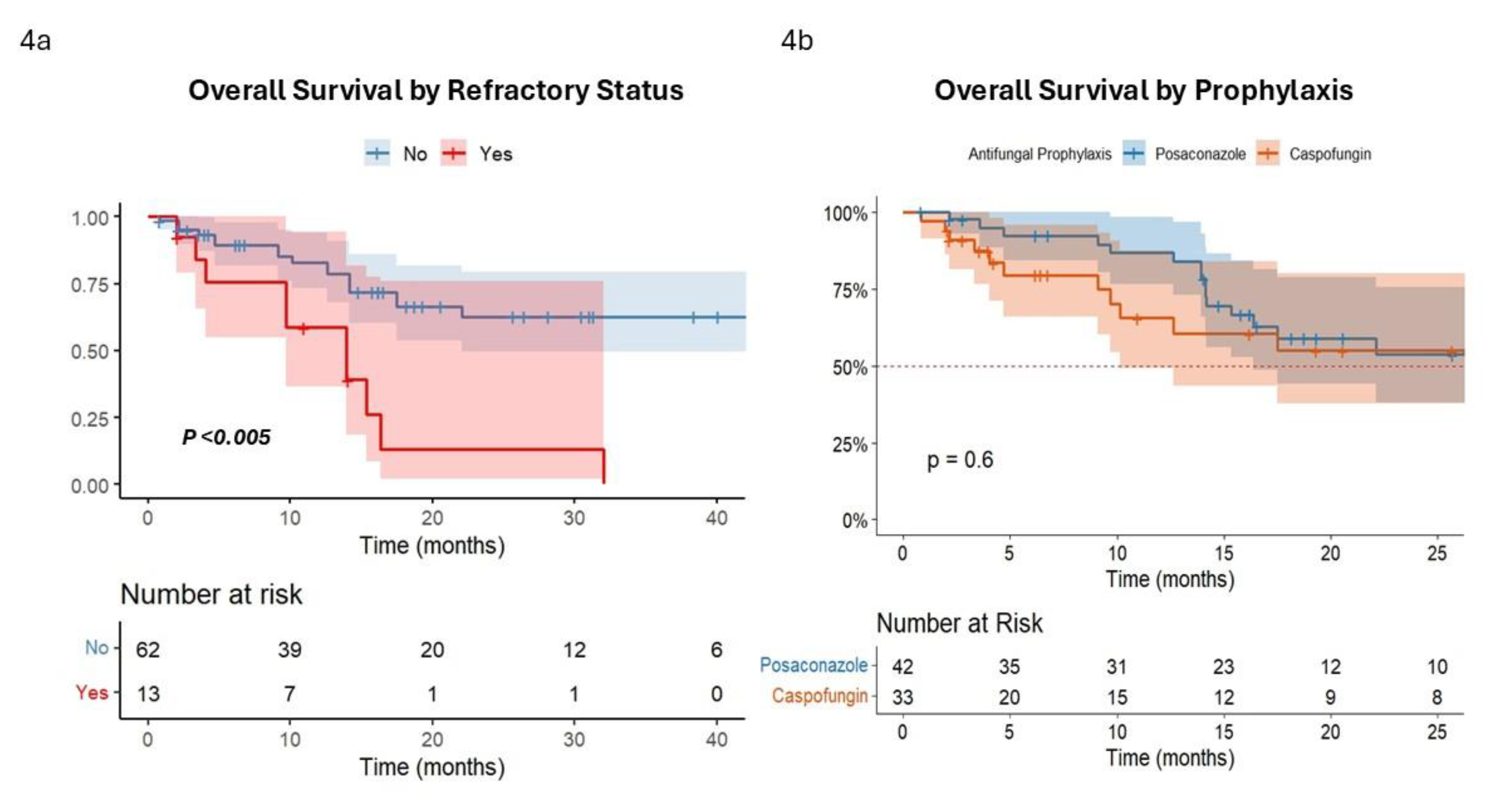

In survival analysis, OS of patients with refractory disease after treatment was significantly inferior to responding patients (median OS =13.9 months [CI95% 9.5 – 13.7] vs. 34.4 months [CI95% 17.5 – 42.1],

P<0.005) (

Figure 4a). Conversely, no significant difference in OS were observed according to type of prophylaxis (Caspofungin vs Posaconazole, (median OS =29.3 months [CI95% 19.5 – 35.7] vs. 32.1 months [CI95% 17.5 – 33.1],

P=0.6) (

Figure 4b).

Univariate Cox regression showed that classical risk factor as age, type of AML, FLT3 status, type of chemotherapy, duration of neutropenia, disease status after treatment, HSCT and diagnosis of IFIs have a significant impact on survival. However, only age and disease status retained their significancy in multivariate analysis model (See

Table 2). Considering that refractory disease significantly influenced OS in our cohort, we finally analyzed the impact of different PAP strategies in patients with refractory disease status. Interestingly a significant difference emerged between patient groups in favor of posaconazole (Posaconazole = 15.3 months [CI95% 13.9 – NA] vs Caspofungin = 4.03 months [CI95% 3.3 – 10.1], p<0.001). (See supplemental results S5).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The evolving therapeutic landscape of AML, marked by the integration of targeted agents such as Venetoclax and Midostaurin, has prompted renewed attention toward antifungal prophylaxis strategies that minimize pharmacologic interactions. Moreover, several guidelines [

29,

30] and recently updated ECIL-10 recommendations [

31] have enforced the role of echinocandins as primary antifungal agents in hematological patients. Therefore, alternative strategies for antifungal prophylaxis are now deemed in AML.

Our study supports the use of caspofungin as a viable alternative to posaconazole, particularly in clinical contexts where oral posaconazole administration is impractical due to patient conditions, or contraindicated due to drug–drug interactions. The overall incidence of IFIs (13.3%) observed in our study is consistent with data reported in literature [

1,

2,

3], remained comparable between prophylaxis groups with no statistical difference, and with no significant correlation between caspofungin and IFIs in logistic regression analysis, supporting the non-inferiority of echinocandins as PAP in AML. Although a numerically higher frequency of probable lung aspergillosis was observed in patients receiving caspofungin, probably due to the narrowed efficacy on molds infections compared to azoles, this condition did not translate into worse outcome, and reflect the ability of second-line antifungal therapy to provide good clinical responses in this setting. Moreover the 70% response rate observed with Isavuconazole and L-AmB confirm in our real-life setting good efficacy of this drugs in managing lung [

36] and liver [

37] IFIs, as reported in literature.

Beyond the choice of prophylactic agent, key risk factors for IFI that can inform clinical practice are evidenced in our study. Correlation analysis and multivariate logistic regression identified pre-existing liver dysfunction and refractory leukemia (failure to achieve remission) as the strongest independent predictors of IFI development. Liver failure has been already associated with an increased risk for IFIs in non-hematological patients [

38]. Probably even in AML patients with significant hepatic comorbidity might present a markedly higher likelihood of breakthrough infection, due to their intrinsic vulnerability or altered drug metabolism, although this data needs to confirmed in larger number, given the retrospective nature of our study. Differently, the evidence that persistent disease and prolonged cytopenias were associated with higher risk of IFIs in our population confirms a well-reported data, and reflects the crucial impact of disease control on infection susceptibility. Other commonly cited factors such as the chemotherapy regimen intensity (e.g. cytarabine/anthracycline

± midostaurin or GO vs. hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax), presence of moderate comorbidities (like COPD, cardiovascular or diabetes), did not independently predict IFI in our analysis, even if some underestimation could be derived from the retrospective nature and the small size of the study.

Survival analysis confirmed that IFI occurrence did not independently influence OS once other prognostic variables were accounted for, supporting the notion that most IFIs, when promptly diagnosed and treated, do not compromise AML outcomes, given the therapeutic options available today. Only infections caused by uncommon molds (i.e proven IFIs by Saprochete spp and Geotrichum spp) led to specific fungal mortality, underlining the need for continued vigilance and aggressive management in such cases, where actually an effective prophylactic agent is still missing [

39]. However, in patients with refractory disease, a significant OS difference emerged based on the prophylaxis strategy, favoring posaconazole treatment. Although this data need to be confirmed in larger studies, the difference may reflect a more robust mold coverage of posaconazole in the setting of prolonged neutropenia, which is more likely to happen in non-responders patients. In line with this, the finding that duration of neutropenia remained a significant factor only in univariate analysis enforces the idea that not in global population, but only in specific setting (i.e. refractory disease) may exert its prognostic impact.

Our study is inherently limited by its retrospective design and the heterogeneity of the study population, which includes patients receiving both intensive and less-intensive venetoclax-based treatment regimens for AML (Where actually real risk for IFIs remain debated) [

40,

41]. However, these therapeutic approaches reflect a real-world context in which the optimal strategy for antifungal prophylaxis need to be refined. Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that caspofungin is clinically comparable to posaconazole for antifungal prophylaxis in AML patients, particularly in scenarios where azole use is contraindicated. Prospective studies are needed to better define individual risk profiles and guide personalized antifungal prophylactic strategies in this population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

FG designed the study, and wrote the manuscript. FG, MM, SA and RI participated in patient care. CC, MG, IC, DL and DDA performed data collection, statistical analysis and data interpretation. NSM, EZ and VG participated in patient care as part of infectious disease team. IG, FP and MP reviewed the manuscript. FG and FP approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethics Declarations

The study was approved by academic local Ethical Committee of Federico II University. For this retrospective study with anonymized data, no formal patient consent was required. Treatment study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Authors Declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary results file.

References

- Logan, C.; Koura, D.; Taplitz, R. Updates in infection risk and management in acute leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020, 2020, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, A.B.; Lyman, G.H.; Walsh, T.J.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Walter, R.B. Primary antifungal prophylaxis during curative-intent therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015, 126, 2790–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Veiga, R.; Montesinos, P.; Boluda, B.; et al. Incidence and outcome of invasive fungal disease after front-line intensive chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: impact of antifungal prophylaxis. Ann Hematol. 2019, 98, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Principe, M.I.; Dragonetti, G.; Verga, L.; et al. ‘Real-life’ analysis of the role of antifungal prophylaxis in preventing invasive aspergillosis in AML patients undergoing consolidation therapy: Sorveglianza Epidemiologica Infezioni nelle Emopatie (SEIFEM) 2016 study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019, 74, 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragonetti, G.; Criscuolo, M.; Fianchi, L.; Pagano, L. Invasive aspergillosis in acute myeloid leukemia: Are we making progress in reducing mortality? Med. Mycol 2017, 55, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, L.; Caira, M.; Candoni, A.; et al. The epidemiology of fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies: the SEIFEM-2004 study. Haematologica. 2006, 91, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Coussement, J.; Lindsay, J.; The, BW.; et al. Choice and duration of antifungal prophylaxis and treatment in high-risk haematology patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021, 34, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copley, M.S.; Waldron, M.; Athans, V.; et al. Itraconazole vs. posaconazole for antifungal prophylaxis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing intensive chemotherapy: A retrospective study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020, 55, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldi, R.L.; Bernardes Coelho, Y.N.; Paranhos, R.L.; Silva, M.J.B. The impact of antifungal prophylaxis in patients diagnosed with acute leukemias undergoing induction chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2023, 23, 3231–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragiannidis, A.; Dokos, C.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Groll, A.H. Antifungal chemoprophylaxis in children and adolescents with haematological malignancies and following allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Review of the literature and options for clinical practice. Drugs.

- Cornely, O.A.; Maertens, J.; Winston, D.J.; et al. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulou, P.; Roilides, E. Evaluating posaconazole, its pharmacology, efficacy and safety for the prophylaxis and treatment of fungal infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022, 23, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Ferreira, A.R.; Märtson, A.G.; De Boer, A.; et al. Does Chemotherapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Mucositis Affect the Bioavailability and Efficacy of Anti-Infective Drugs? Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, R.M.; Mandrekar, S.J.; Sanford, B.L.; et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Jonas, B.A.; Pullarkat, V.; et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemler, J.; de Jonge, N.; Skoetz, N.; et al. Antifungal prophylaxis in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia treated with novel targeted therapies: a systematic review and expert consensus recommendation from the European Hematology Association. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e361–e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Di Nardo, C.; Potluri, J.; et al. Management of Venetoclax-Posaconazole Interaction in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients: Evaluation of Dose Adjustments. Clin Ther. 2017, 39, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemler, J.; Koehler, P.; Maurer, C.; et al. Antifungal prophylaxis and novel drugs in acute myeloid leukemia: the midostaurin and posaconazole dilemma. Ann Hematol. 2020, 99, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaoutis, T.E.; Jafri, H.S.; Huang, LM.; et al. A prospective, multicenter study of caspofungin for the treatment of documented Candida or Aspergillus infections in pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2009, 123, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, A.L.; Bourque, M.R.; Lupinacci, R.J.; et al. Overview of safety experience with caspofungin in clinical trials conducted over the first 15 years: a brief report. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011, 38, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S.M.; Farhadi, T.; Velayati, A.A. Caspofungin: a review of its characteristics, activity, and use in intensive care units. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020, 18, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C.; Monte, S.; Algarotti, A.; et al. A randomized comparison of caspofungin versus antifungal prophylaxis according to investigator policy in acute leukaemia patients undergoing induction chemotherapy (PROFIL-C study). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66, 2140–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.F.; Xue, Y.; Zhu, X.B.; Fan, H. Efficacy and safety of echinocandins versus triazoles for the prophylaxis and treatment of fungal infections: a meta-analysis of RCTs. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.J.; Teppler, H.; Donowitz, G.R.; et al. Caspofungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for empirical antifungal therapy in patients with persistent fever and neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorak, C.C.; Fisher, B.T.; Esbenshade, A.J.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Caspofungin vs Triazoles Prophylaxis for Invasive Fungal Disease in Pediatric Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020, 10, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, J.; Lodewyck, T.; Donnelly, JP.; et al. Empiric vs Preemptive Antifungal Strategy in High-Risk Neutropenic Patients on Fluconazole Prophylaxis: A Randomized Trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 76, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.T.; Zaoutis, T.; Dvorak, CC.; et al. Effect of Caspofungin vs Fluconazole Prophylaxis on Invasive Fungal Disease Among Children and Young Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019, 322, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, R.; Bai, C.Q.; et al. Caspofungin for prophylaxis and treatment of fungal infections in adolescents and adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmazie. 2012, 67, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Stemler, J.; Mellinghoff, S.C.; Khodamoradi, Y.; et al. Primary prophylaxis of invasive fungal diseases in patients with haematological malignancies: 2022 update of the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Haematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). J Antimicrob Chemother 2023, 78, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; Swaminathan, S.; Almyroudis, N.G.; et al. Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Infections, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024, 22, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, L.; Maschmeyer, G.; Lamoth, F.; et al. Primary antifungal prophylaxis in hematological malignancies. Updated clinical practice guidelines by the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL). Leukemia. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Chen, S.C.; Kauffman, C.A.; et al. Revision and Update of the Consensus Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease From the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 71, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.D.; Johnson, M.; Bresnik, M.; et al. Real-World Antifungal Therapy Patterns Across the Continuum of Care in United States Adults with Invasive Aspergillosis. Journal of Fungi. 2024, 10, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pepa, R.; Picardi, M.; Sorà, F.; et al. Successful management of chronic disseminated candidiasis in hematologic patients treated with high-dose liposomal amphotericin B: a retrospective study of the SEIFEM registry. Support Care Cancer. 2016, 24, 3839–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Mohamad, B.; Soubani, A.O. Epidemiology and Inpatient Outcomes of Invasive Aspergillosis in Patients with Liver Failure and Cirrhosis. Journal of Fungi. 2025, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprute, R.; Seidel, D.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. EHA Endorsement of the Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Rare Mold Infection: An Initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in Cooperation With International Society for Human and Animal Mycology and American Society for Microbiology. Hemasphere 2021, 5, e519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aldoss, I.; Dadwal, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Invasive fungal infections in acute myeloid leukemia treated with venetoclax and hypomethylating agents. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 4043–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candoni, A.; Lazzarotto, D.; Papayannidis, C.; et al. Prospective multicenter study on infectious complications and clinical outcome of 230 unfit acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving first-line therapy with hypomethylating agents alone or in combination with Venetoclax. Am J Hematol 2023, 98, E80–E83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).