1. Introduction

Canine chronic inflammatory enteropathies (CIE) are a group of disorders characterized by persistent or recurrent gastrointestinal (GI) signs (diarrhea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain) that have no identifiable extraintestinal cause [

1,

2]. The following CIE subtypes can be identified based on the treatment response: food-responsive enteropathy (FRE), antibiotic (microbiome)-responsive enteropathy, immunosuppressant-responsive enteropathy, and non-responsive enteropathy [

1,

2]. Of these, FRE is the most common subtype that accounts for up to 50–70% of chronic enteropathies in dogs [

1,

2]. The affected dogs usually improve within 2–4 weeks when placed on an elimination diet containing a novel protein or a hydrolyzed protein source [

3,

4]. The selection of novel, less antigenic protein sources is critical, as many dogs have been exposed to common dietary ingredients such as beef, poultry, or dairy [

5,

6]. These findings have increased the interest in alternative proteins for hypoallergenic diets.

Edible insects have emerged as a promising novel protein source in pet nutrition [

3]. Insects are abundant in nutrients and proteins with a favorable amino acid profile, and they are often a rich source of lipids [

5,

6]. The larvae of the black soldier fly (

Hermetia illucens) and yellow mealworm (

Tenebrio molitor), as well as adult house crickets (

Acheta domesticus) are among the leading candidates for pet nutrition [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Yellow mealworm larvae are attractive feed ingredients on account of their high content of protein (approx. 50%), fat (30%), and dietary fiber [

10]. Mealworm proteins have high amino acid scores. According to the literature, the quality of

T. molitor protein is comparable to that of animal-derived products [

11]. Bosch et al. reported that the digestibility of insect protein can vary across species, but the protein content and amino acid profiles of mealworms and crickets are similar to those of fish meal and are characterized by high in vitro nitrogen digestibility [

11]. Subsequent research has confirmed that the apparent total tract digestibility of insect-based diets is comparable to that of traditional diets [

12]. Case studies have shown that insect-based diets were well tolerated by dogs with severe food allergies and led to clinical improvement. In the work of Cesar et al., a dog with a food allergy and chronic diarrhea responded well to a diet incorporating BSF larvae, which led to symptom resolution with no adverse reactions [

5]. However, a cautious approach is still needed because insect proteins share some epitopes with other allergens. Premrov Bajuk et al. demonstrated that dogs allergic to dust mites can exhibit IgE cross-reactivity to mealworm proteins [

13].

Beyond basic nutrition and allergenicity, insects offer additional functional benefits. Insect meals naturally contain chitin, a fiber-like polysaccharide from the exoskeleton, as well as other bioactive compounds (such as antimicrobial peptides and medium-chain fatty acids) that may positively influence gut health and immunity [

14,

15]. For instance, lauric acid (abundant in BSF larvae oil) has antibacterial properties and can modulate the gut microbiome [

16]. Chitin and its derivatives can act as prebiotic fiber and exert immunostimulatory effects on gut mucosa [

17,

18]. Feeding trials in dogs revealed only minimal changes in the fecal microbiome when traditional proteins were replaced with insect meal, and the counts of some beneficial bacterial genera (such as

Lactobacillus and

Faecalibacterium) were found to increase [

19].

In addition to gut-localized effects, emerging evidence indicates that insect proteins could confer systemic health benefits. In vivo models have shown that insect-based diets exert anti-inflammatory effects and lead to metabolic improvements. Feeding trials conducted in rodents demonstrated that diets enriched with mealworm proteins improved serum lipid profiles (by increasing HDL cholesterol and lowering LDL cholesterol) and reduced weight gain in obese mice [

20]. In a mouse model of accelerated aging, supplementation with

T. molitor protein decreased the levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) by 17–75% and increased the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 [

21]. The same study demonstrated that mealworm protein enhanced the activity of antioxidant enzymes and even lengthened telomeres in mice, suggesting anti-aging and cell-protective effects [

21]. A study of rats fed high-fat diets also revealed that the replacement of animal protein with insect protein (such as BSF larvae meal) can attenuate hepatic steatosis and reduce triglyceride accumulation in the liver [

22]. These systemic effects may be attributed to bioactive peptides, improved amino acid profiles, or functional fatty acids in insects that influence metabolic pathways and inflammation.

Despite these promising results, the use of insects in pet foods can be challenging in practice. Pet owner acceptance can be a hurdle – some consumers are hesitant to feed “bugs” to their pets due to neophobia or misconceptions [

23]. Safety and quality control must also be ensured in insect farming. Insects can accumulate contaminants (such as heavy metals or pathogens) under inadequate rearing conditions [

24]. However, commercial insect producers operate under controlled conditions, and research has shown that the risk of contamination is low when insects are raised on clean feedstocks.

The aim of this case study was is to analyze the impact of a mealworm-based diet in a dog with FRE. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to report on the resolution of chronic enteropathy as well as a concomitant improvement in gallbladder pathology (biliary sludge) in a dog fed an insect-based diet.

2. Case Presentation

A five-year-old intact male Yorkshire Terrier (body weight: 4.5–5.4 kg before the dietary intervention; body condition score (BCS) 6 or 7/9, i.e. overweight) was evaluated for chronic GI issues at the Veterinary Polyclinic of the University of Warmia and Mazury (Poland). The dog had pre-existing cardiac disease (insufficiency of the right and left atrioventricular valves and ACVIM stage C endocardiosis) that was managed with pimobendan, furosemide, and benazepril. The patient had also been diagnosed with tracheal collapse that was controlled with glucosamine and chondroitin supplements. In January 2021, gallbladder sludge (biliary inspissation) was accidentally discovered during an abdominal ultrasound exam. The dog was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid for six months, and follow-up ultrasonography revealed a minor improvement, but not complete resolution of the sludge.

In early 2021, the dog was fed a conventional diet (dry kibble with lamb and wet canned food with venison). Despite these novel protein diets, the owner reported chronic intermittent GI signs, including vomiting, diarrhea, borborygmus/belching, abdominal discomfort, bloating, and soft stools. These symptoms were exacerbated by other foods. During acute episodes, the dog’s condition deteriorated to an extent that required veterinary intervention. Treatments typically included subcutaneous or IV fluids, antiemetic therapy (maropitant), gastroprotectants and antispasmodics (such as metamizole with hyoscine, or buprenorphine for visceral pain), antidiarrheals, and probiotics (containing Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium animalis). These interventions would lead to improvement after 4–10 days. Given the pattern of GI issues correlating with dietary indiscretions and the dog’s partial response to the elimination diet, FRE was confirmed in the course of a diet trial.

In August 2021, the dog was switched to dry food with a 35% inclusion level of

T. molitor larvae meal as the sole source of animal protein. The diet consisted of a formulation that had been previously described by Gałęcki et al. [

25], with a modification of the amino acid profile. No other changes in the dog’s lifestyle were made at the time of the dietary transition. The new diet was introduced gradually over a period of around seven days, and it was well accepted by the dog. According to the owner, the dog eagerly ate insect-based kibbles and even showed a preference for the new diet over his previous food. A notable improvement in GI signs was observed two to three weeks after the dietary change: the dog’s stools were well-formed and regular; vomiting ceased, and abdominal discomfort and bloating resolved. The dog’s overall condition, energy levels, and appetite improved. In the following months, the dog’s body weight decreased to around 4.0 kg (BCS 4–5/9, an ideal score) from, presumably due to the combined effects of the new diet and controlled food intake. After several months of adherence to the

T. molitor diet, a follow-up ultrasound exam revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible sludge, marking an improvement from previous scans. The

T. molitor-based diet was continued, and by early 2022, the dog was free of FRE symptoms and was considered to be in clinical remission.

The dog was subjected to periodic recheck examinations involving blood tests and interviews with the owner. Clinical severity was quantified using the Canine IBD Activity Index (CIBDAI) and the Canine Chronic Enteropathy Clinical Activity Index (CCECAI), which assess factors such as attitude, appetite, vomiting frequency, stool consistency and frequency, weight loss, serum albumin levels, ascites, and pruritus. Retrospectively, the dog’s scores before the dietary intervention were indicative of severe disease (CIBDAI = 9, CCECAI = 11; consistent with severe enteropathy and significant clinical disease). After several months on the

T. molitor diet, the dog’s scores improved to two points on each scale, corresponding to clinically insignificant disease. In particular, chronic vomiting (previous score of 3 points for vomiting frequency/severity) was eliminated (0 points), stool consistency was normalized (from soft = 2 points, to normal = 0 points), and appetite improved from moderate reduction (2 points) to normal (0 points). Mild pruritus (2 points, possibly related to food sensitivity) was also resolved (0 points). Weight loss was the only score component that was not fully normalized (the dog scored 2 points after switching to the new diet), but the goal of the dietary intervention was to achieve a healthy weight, rather than cachexia. CIBDAI and CCECAI scores are presented in

Table 1.

Complete blood counts and serum biochemistry panels were performed roughly every 6–12 months to monitor systemic health and screen for any issues related to the new diet. The results remained largely unremarkable for more than two years during which the dog remained on the insect-based diet. At the beginning of the study, hematocrit and hemoglobin levels were in the mid-normal range (HCT ≈ 50%, Hgb ≈ 17 g/dL) and remained stable, with a minor decrease in late 2024 (HCT = 39%, Hgb = 10.5 g/dL) that was not associated with clinical anemia (the dog was active and had pink mucous membranes). Total protein and albumin levels remained stable or slightly increased on the new diet (albumin increased from 3.3 g/dL in 2021 to 4.6 g/dL in 2024, exceeding the upper reference limit by ≈ 15%). High-normal albumin was associated with improved nutritional status or mild hemoconcentration, but there were no signs of protein-losing enteropathy at any point in the study (normal albumin and globulins). The activity of liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP) and total bilirubin remained within the reference intervals, and kidney markers (urea, creatinine) were within the norm, which suggests that the diet did not lead to organ toxicity. Cholesterol levels were low-normal (123 mg/dL) during acute episodes of FRE, and increased to around 175–214 mg/dL during remission (still within the normal range, potentially indicative of improved nutrient intake). These results indicate that the insect-based diet provided adequate nutrition and did not cause any metabolic disturbances. The results of blood morphology and biochemistry tests are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

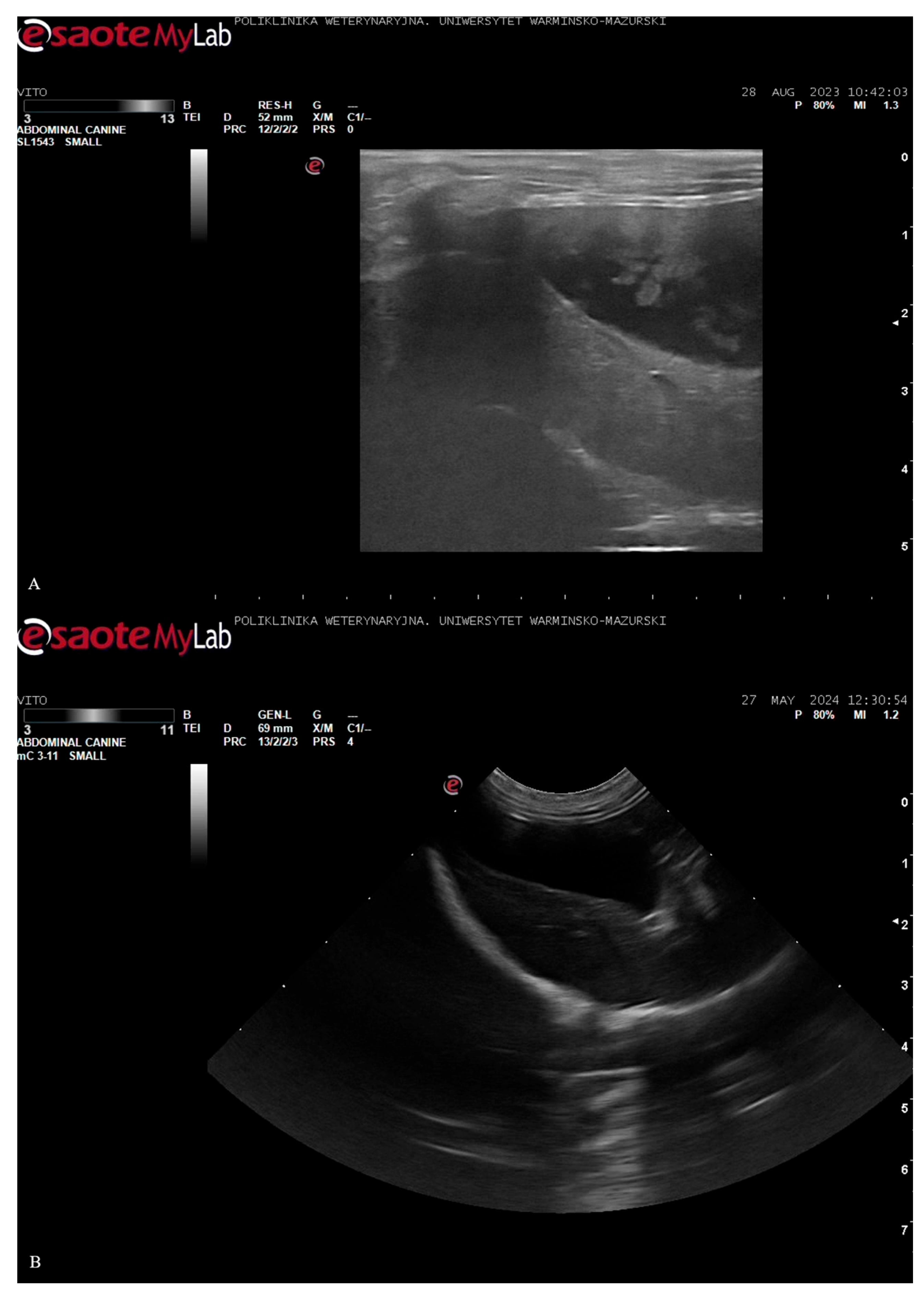

In late July/early August 2023, the dog’s health deteriorated, probably due to acute poisoning (potential toxin ingestion), which led to severe systemic illness. The patient presented with vomiting, anorexia, and lethargy, and the results of diagnostic tests were indicative of acute gastritis, enteritis, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder). The dog was admitted to an intensive care unit and received IV fluids, antibiotics, analgesics, and antiemetics. During hospitalization, the dog was placed on a veterinary prescription GI diet (commercial wet food) to improve appetite and facilitate digestion. The patient recovered from the acute episode within one to two weeks and was discharged. However, due to lingering anorexia and taste aversion after the illness, the dog refused to eat the low-fat prescription diet at home. The owner attempted to find alternative commercial diets with <8% fat content that the dog would accept and experimented with several different protein sources (fish-based, hydrolyzed poultry) over the span of one week. The palatability of these alternatives was poor – the dog ate very little, prompting concerns about nutritional maintenance.

A recheck abdominal ultrasound was performed approximately one week after hospital discharge. Gallbladder sludge reappeared after nearly two years on the

T. molitor diet. The above could be attributed to multiple factors, with the recent anorexia and rapid dietary changes as potential contributors. The prescription GI diet, while low in fat, was moderate in fiber and contained ingredients that might have affected bile composition or gallbladder motility. In early August 2023, ursodeoxycholic acid was re-started to help dissolve the sludge. However, the treatment was discontinued by the owner due to difficulties with oral administration. Appetite issues persisted in the following three weeks, and the owner decided to switch back to the

T. molitor-based diet (given the dog’s previous positive response and willingness to eat it). The dog’s food intake improved immediately. One month later, a follow-up ultrasound (after around 3–4 weeks on the

T. molitor diet) revealed that the sludge had once again cleared (anechoic, normal bile). In October 2023, a repeat ultrasound confirmed that the gallbladder was clear. This timeline suggests that the

T. molitor diet might have played a role in maintaining gallbladder health because sludge appeared during the dietary break and was eliminated once the dog had resumed the diet. The patient remained on the

T. molitor-based diet, and its condition was assessed as stable in late 2023. Ultrasound images are presented in

Figure 1.

As of mid-2024, the dog had been kept on the T. molitor-based diet for around two years in total (with a short break during the poisoning incident). The owner reported that dog’s overall condition had shown unparalleled improvement. The dog no longer experienced significant GI flare-ups after scavenging small amounts of novel foods during walks. At most, the only consequence was a soft stool, which resolved quickly without an anti-diarrheal, marking a significant change from acute episodes that previously required a visit to the clinic. Food-responsive enteropathy was effectively in remission as long as the dog stayed on the insect-based diet. Frequent dietary changes (every few weeks) caused by food aversion were no longer an issue, and the dog willingly ate the same T. molitor diet continuously. Stools remained consistently well-formed, and defecation frequency normalized to 1–2 times a day. The dog’s coat, previously dull and prone to thinning, developed a healthy shine and fullness. No dermatological problems or pruritus were observed while on the insect-based diet. The dog's condition had not deteriorated by the time this article was submitted for publication.

With the exception of cardiac drugs, the dog did not require any other medications while on the T. molitor diet. Probiotics and other GI drugs were tapered off. Preventive care such as vaccinations, deworming, and dental prophylaxis was kept up to date. By the end of the observation period, the dog’s FRE was well-controlled with diet alone.

3. Discussion

This case study demonstrated that an insect-based diet (

T. molitor larvae) can be successfully used as a novel protein source to manage chronic FRE in a dog. Over a two-year period, the dog’s GI signs improved dramatically to a point where clinical disease activity indices were stabilized within the normal range of values indicative of remission. Notably, recurring gallbladder issues (biliary sludge) were also resolved after the patient had been placed on an insect-based diet. In dogs, biliary sludge is often an incidental finding that is not always clinically significant [

26,

27,

28], but in the current study, the presence of sludge correlated with periods of GI problems and vomiting, which suggests it did have clinical relevance. Before the dietary change, the dog frequently vomited bile and had abdominal pain, and these signs can be associated with gallbladder dysmotility or cholestasis. After sustained feeding with the

T. molitor diet, those signs abated, and ultrasound exams revealed an empty, normally functioning gallbladder. When the diet was briefly discontinued (due to the poisoning incident), sludge reappeared and vomiting recurred, and both issues once again resolved when the insect diet was resumed. This temporal association suggests a cause-and-effect relationship, though the exact mechanism is speculative.

One hypothesis is that the low fat content and the fatty acid composition of the

T. molitor diet facilitated gallbladder emptying. High-fat, high-cholesterol diets and obesity are known risk factors for bile stasis and sludge formation in dogs [

28]. In contrast, diets with a moderate fat content and balanced fatty acid composition may promote gallbladder contraction and bile flow. For example, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have been reported to enhance gallbladder motility and alter prostaglandin synthesis in ways that could reduce biliary sludge [

28]. In the described case, the insect-based diet had an omega-6:omega-3 ratio of approximately 7.3:1. A very high omega-6:3 ratio can have pro-inflammatory effects, whereas a very low ratio can lead to oxidative stress or coagulopathies [

29]. A 7:1 ratio is moderate, and it might have contributed to an anti-inflammatory effect supporting biliary health. Additionally,

T. molitor fat contains some lauric acid (C12:0) and other medium-chain triglycerides with antimicrobial and emulsifying properties [

23,

30]. Lauric acid can inhibit the growth of certain biliary pathogens and reduce bile sludge formation through its cleansing effects [

31]. Although this observation could be speculative based on the results of a single report, the inclusion of these fatty acids in the dog’s diet could have contributed to a decrease in bile viscosity.

The second major theme to emerge from this study is the apparent anti-inflammatory and gut-stabilizing effect of the mealworm-based diet. By definition, FRE improves with dietary modification, but the degree of improvement in the examined dog was striking. After years of frequent visits to the clinic, the dog’s symptoms disappeared completely, and no medical interventions, other than the diet, were required. This suggests that insect protein was truly hypoallergenic, and perhaps even exerted additional anti-inflammatory effects beyond allergen avoidance. This observation aligns with the growing body of scientific evidence that insect proteins contain bioactive peptides that modulate inflammation.

Tenebrio molitor proteins have been shown to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines in experimental models. For example, Shang et al. demonstrated that

T. molitor peptide supplementation reduced the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 genes in mice with intestinal injury [

32]. Similarly, Anusha and Negi reported significant reductions in the circulating levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in aged mice fed mealworm protein, as well as an increase in the levels of the IL-4 anti-inflammatory cytokine [

21]. These cytokines (TNF, IL-1, IL-6) are the key mediators in canine inflammatory bowel disease, contributing to mucosal inflammation. By lowering their levels, the insect diet may have helped restore normal intestinal immune homeostasis in the dog. These findings align with the observations made in the present study: the dog’s GI problems resolved on the insect-based diet, hinting at reduced inflammatory activity. The CIBDAI score for vomiting decreased from 3 (severe) to 0, and stool consistency normalized, which could point to healing of the previously inflamed gut lining. Intestinal biopsies or cytokine assays were not performed in this case (the patient had suffered from cardiological problems, and the owner did not consent to an endoscopic examination), but the clinical remission was consistent with what one might expect if intestinal inflammation were markedly reduced.

Another notable observation was the improvement in dermatological signs. Before starting the insect diet, the dog had some pruritus and a poor coat, which was initially attributed to either low-grade food allergy or general ill thrift. After the patient had been placed on the

T. molitor diet, pruritus resolved, and coat quality improved. Similar reports can be found in the literature, where insect-based diets benefitted dogs with cutaneous adverse food reactions. Böhm et al. evaluated dogs with food-responsive atopic dermatitis that had been switched to an insect-based diet, and reported a significant reduction in dermatological symptoms and an improvement in coat condition [

33]. The authors postulated that the novel insect protein reduced allergen exposure and possibly provided omega-3 fatty acids that improved the skin barrier function [

33]. In addition,

T. molitor meal contains linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid (fatty acids that are essential for skin health) and is rich in minerals such as zinc and copper than enhance coat quality [

5]. Thus, improved nutrition could have directly contributed to a healthier skin and coat. Regardless of the exact cause, cutaneous improvements provide further evidence for the holistic benefits of an insect-based diet for dogs.

With regard to nutritional adequacy and safety, the present findings indicate that insect-based diets can meet a dog’s needs in the long term. The patient’s body weight and muscle condition stabilized and were maintained within the ideal range. Nutritional deficiencies were not observed, and serum albumin levels increased to a high-normal range, indicating robust protein nutrition. Jacuńska et al. examined 14 commercial insect-based dog foods and concluded that all met minimal requirements for protein and amino acids, and that most diets provided adequate levels of vitamins and minerals (with some variability depending on the added premixes) [

34]. Notably, dogs consuming these diets did not display any signs of hepatic or renal stress, and liver enzyme and kidney parameters were within the norm. Controlled studies also found that insect protein diets caused no adverse changes in blood parameters [

12]. Lisenko et al. investigated dogs fed diets incorporating cockroach and mealworm meal (up to 15% inclusion) and reported normal blood hematology/biochemistry and high nutrient digestibility across all groups [

19]. The described case and literature data indicate that insect-based diets are physiologically well tolerated.

Insect-based diets could also modulate the gut microbiota. A fecal microbiome analysis was not performed in this study, but the dog’s clinical outcome (improved stool and reduced gas/bloating) may suggest a more balanced gut environment. Insect ingredients, especially chitin, can act as fermentable fiber for gut bacteria. Some studies in dogs have shown that insect-based diets cause only minor shifts in microbial populations. Areerat et al. examined dogs fed cricket or silkworm meal and found no significant changes in major bacterial phyla, except for a slight increase in

Lactobacillus counts in the silkworm group [

9]. Lactic acid bacteria such as

Lactobacillus spp. are generally beneficial for gut health, and an increase in their abundance could correlate with improved stool consistency, as observed in this study. Other researchers reported stable microbiota diversity and normal fecal short-chain fatty acid levels in dogs consuming a BSF larvae diet, which indicates that insects did not disrupt fermentation patterns [

35]. A study investigating mealworm inclusion in canine diets found that insect ingredients such as chitin could act as prebiotics that stimulate the growth of beneficial microbes, including butyrate-producing bacteria of the genus

Faecalibacterium that contribute to gut health [

19].

From a broader perspective, this case study adds to the growing body of evidence that insect-based pet foods provide functional benefits in managing some health conditions. Food-responsive enteropathies encompass both allergies and intolerances, and they can be challenging to manage if the animal is sensitive to multiple ingredients. In this scenario, insects offer a truly novel alternative. In the present study, novel terrestrial proteins (lamb and venison) did not lead to full recovery, and the patient achieved remission only after switching to an insect-based diet. The above implies that even unconventional meat sources can sometimes share cross-reactive epitopes, whereas insects are evolutionarily very distant from traditional livestock and thus less cross-reactive. Finally, it is worth noting that insect-based diets should be introduced with veterinary guidance, particularly in dogs with a complex medical history [

6]. In the examined case, the insect-based diet was beneficial, but veterinarians should ensure that the chosen insect diet complies with the standards of the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) and is suitable for a particular life stage, and they should monitor the pet’s condition. As with any novel ingredient, idiosyncratic reactions, such as a rare allergy to insect protein or fat malabsorption, are possible. In the examined scenario, the insect-based diet was introduced gradually, and the patient was closely monitored.

This case study has a number of potential limitations. Observations were made on a single animal without a controlled rechallenge (except for the dietary break caused by poisoning). The timeline strongly suggests that the insect-based diet led to clinical improvement, but other unacknowledged factors could have contributed. The dog was administered the same cardiac medications and received the same level of care during the entire study; therefore, these factors are unlikely to explain the GI remission. The brief use of ursodeoxycholic acid somewhat confounds the gallbladder outcome. However, the fact that the sludge cleared only after switching to the insect-based diet despite recent ursodeoxycholic acid treatment (and was cleared once again by the diet) suggests that diet was the main factor.

Due to the lack of consent from the owner, the histologic resolution of enteropathy was not confirmed by endoscopy or biopsy, and the assessment was primarily clinical. Anesthesia also posed a potential risk due to cardiac problems. However, in practice, FRE is often managed based solely on the patient’s clinical response to the diet, without the use of invasive diagnostics, especially when the patient is doing well. Another limitation is that inflammatory markers or gut microbiota were not measured directly. The conclusions regarding the diet’s anti-inflammatory and microbiome-stimulating effects were formulated based on a review of the literature, rather than direct observations. Nonetheless, the consistency of the dog’s outcomes with published data lends credence to those interpretations.

4. Conclusions

The present case study of a canine patient provides practical insights on how a T. molitor-based diet can be used to manage chronic enteropathy, achieve remission of GI symptoms, and provide ancillary benefits to skin and gallbladder health. These findings reinforce the view that insects are not only an environmentally-sustainable protein source, but also a clinically effective solution for patients with food-responsive diseases. The observed positive outcomes, including high palatability, nutritional adequacy, resolution of clinical signs, and no adverse effects, indicate that insect-based diets have the potential to be integrated into mainstream veterinary dietary therapy. As research on insects in veterinary nutrition and animal science expands, the results of this study are likely to be validated by new case reports or even controlled clinical trials. For now, veterinarians and owners of pets with FRE or similar conditions should be aware that insect protein is a viable option, especially when conventional novel proteins do not bring the anticipated outcomes or when additional health benefits (such as anti-inflammatory effects) are desired.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and I.G.; methodology, R.G. and I.G.; software, R.G.; validation, R.G. and I.G.; formal analysis, R.G. and I.G.; investigation, R.G. and I.G.; resources, R.G.; data curation, R.G.; writing—original draft preparation R.G. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, R.G. and I.G.; visualization, R.G. and I.G.; supervision, R.G.; project administration, R.G.; funding acquisition, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Center for Research and Development (NCBiR) as part of the Lider XII project entitled "Development of an insect protein food for companion animals with food-responsive enteropathies" (Project No. LIDER/5/0029/L-12/20/NCBR/2021). Publication costs were financed by the Minister of Science under the Regional Initiative of Excellence Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All diagnostic procedures were performed as part of routine veterinary care, and the approval of the ethics committee was not required (Chapter 1, Paragraph 1.2.1 of the Act of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes; Journal of Laws 2015, item 266). The dog's owner was informed about the study and consented to the publication of this case report.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the animal’s owner.

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give special thanks to Ms. Sara Stecka, a receptionist at the Veterinary Polyclinic and a student of Animal Sciences at the Faculty of Animal Bioengineering of the University of Warmia and Mazury, for her help with describing the presented case.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALB |

Albumin |

| ALB/GLOB |

Albumin-to-globulin ratio |

| ALKP |

Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT |

Alanine aminotransferase |

| AMY |

Amylase |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BASO |

Basophils |

| BCS |

Body condition score |

| BSF |

Black soldier fly |

| BUN |

Blood urea nitrogen |

| Ca |

Calcium |

| CCECAI |

Chronic Enteropathy Clinical Activity Index |

| CHOL |

Cholesterol |

| CIBDAI |

Canine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Activity Index |

| CIE |

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy |

| CREA |

Creatinine |

| EOS |

Eosinophils |

| FRE |

Food-responsive enteropathy |

| GGT |

Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| GLOB |

Globulin |

| GLU |

Glucose |

| HCT |

Hematocrit |

| HGB |

Hemoglobin |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin 6 |

| K |

Potassium |

| LIPA |

Lipase |

| LYM |

Lymphocytes |

| MCH |

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin |

| MCHC |

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration |

| MCV |

Mean corpuscular volume |

| MPV |

Mean platelet volume |

| Na |

Sodium |

| Na/K |

Sodium-to-potassium ratio |

| NEU |

Neutrophils |

| PCT |

Plateletcrit |

| PHOS |

Phosphorus (phosphate) |

| PLT |

Platelets |

| RBC |

Red blood cell count |

| RDW |

Red cell distribution width |

| RETIC |

Reticulocyte count |

| TBIL |

Total bilirubin |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor α |

| TP |

Total protein |

| TT4 |

Total thyroxine (T4) |

| WBC |

White blood cell count |

References

- Dupouy-Manescau, N. , et al., Updating the classification of chronic inflammatory enteropathies in dogs. Animals 2024, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, Y. , Chronic Enteropathy and Vitamins in Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jergens, A.E. and R.M. Heilmann, Canine chronic enteropathy—Current state-of-the-art and emerging concepts. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 923013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiche, V. , et al., An extensively hydrolysed protein-based extruded diet in the treatment of dogs with chronic enteropathy and at least one previous diet-trial failure: a pilot uncontrolled open-label study. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, C.G.L. , et al., An assessment of the impact of insect meal in dry food on a dog with a food allergy: a case report. Animals 2024, 14, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałęcki, R. Hanuszewska-Dominiak, and E. Kaczmar, Edible insects as a source of dietary protein for companion animals with food responsive enteropathies–perspectives and possibilities. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2024; 309-318-309-318. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, S. Heide, and J. Zentek, Evaluation of an extruded diet for adult dogs containing larvae meal from the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 270, 114699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Wahab, A. , et al., Insect larvae meal (Hermetia illucens) as a sustainable protein source of canine food and its impacts on nutrient digestibility and fecal quality. Animals 2021, 11, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areerat, S. , et al., Possibility of using house cricket (Acheta domesticus) or mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori) pupae meal to replace poultry meal in canine diets based on health and nutrient digestibility. Animals 2021, 11, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordiean, A. , et al., Influence of different diets on growth and nutritional composition of yellow mealworm. Foods 2022, 11, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, G. , et al., Protein quality of insects as potential ingredients for dog and cat foods. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 3, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freel, T.A. McComb, and E.A. Koutsos, Digestibility and safety of dry black soldier fly larvae meal and black soldier fly larvae oil in dogs. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premrov Bajuk, B. , et al., Insect protein-based diet as potential risk of allergy in dogs. Animals 2021, 11, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyatma, N.E. , et al., Mechanical and barrier properties of biodegradable films made from chitosan and poly (lactic acid) blends. J. Polym. Environ. 2004, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj Slimen, I. , et al., Insects as an alternative protein source for poultry nutrition: a review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1200031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elieh Ali Komi, D. Sharma, and C.S. Dela Cruz, Chitin and its effects on inflammatory and immune responses. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 54, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, E. , et al., Reshaping gut bacterial communities after dietary Tenebrio molitor larvae meal supplementation in three fish species. Aquaculture 2019, 503, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, U. , et al., Insect meal as a feed ingredient for poultry. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 35, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisenko, K.G. , et al., Digestibility of insect meals for dogs and their effects on blood parameters, faecal characteristics, volatile fatty acids, and gut microbiota. J. Insects Food Feed 2023, 9, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. , et al., Yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) and lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus) proteins slowed weight gain and improved metabolism of diet-induced obesity mice. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusha, S. and P.S. Negi, Tenebrio molitor (Mealworm) protein as a sustainable dietary strategy to improve health span in D-galactose-induced aged mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, M.J. , et al., Feeding of Hermetia illucens larvae meal attenuates hepatic lipid synthesis and fatty liver development in obese Zucker rats. Nutrients 2023, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kępińska-Pacelik, J. and W. Biel, Insects in pet food industry—Hope or threat? Animals 2022, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałęcki, R., T. Bakuła, and J. Gołaszewski, Foodborne diseases in the edible Insect industry in Europe—New challenges and old problems. Foods 2023, 12, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałęcki, R.; Pszczółkowski, B.; Zielonka, Ł. Experiences in Formulating Insect-Based Feeds: Selected Physicochemical Properties of Dog Food Containing Yellow Mealworm Meal. Preprints 2025, 2025052237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, P. , et al., Prevalence, risk factors, and biochemical markers in dogs with ultrasound-diagnosed biliary sludge. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.K. V. Jambhekar, and A.M. Dylewski, Gallbladder sludge in dogs: ultrasonographic and clinical findings in 200 patients. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2016, 52, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.A. M. Aicher, and R. Duarte, Nutritional Factors Related to Canine Gallbladder Diseases—A Scoping Review. Vet. Sci. 2024, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burron, S. , et al., The balance of n-6 and n-3 fatty acids in canine, feline, and equine nutrition: Exploring sources and the significance of alpha-linolenic acid. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzertiha, A. , et al., Insect fat in animal nutrition–a review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2020, 20, 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmoro, Y.K. H. Franceschi, and C. Stefanello, A Systematic Review and Metanalysis on the Use of Hermetia illucens and Tenebrio molitor in Diets for Poultry. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y. , et al., Study on the mechanism of mitigating radiation damage by improving the hematopoietic system and intestinal barrier with Tenebrio molitor peptides. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 8116–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, T.M. , et al., Effect of an insect protein-based diet on clinical signs of dogs with cutaneous adverse food reactions. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 2018, 46, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Jacuńska, W., W. Biel, and K. Zych, Evaluation of the Nutritional Value of Insect-Based Complete Pet Foods. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, K. , et al., Digestion, faeces microbiome, and selected blood parameters in dogs fed extruded food containing Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) meal. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).