Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

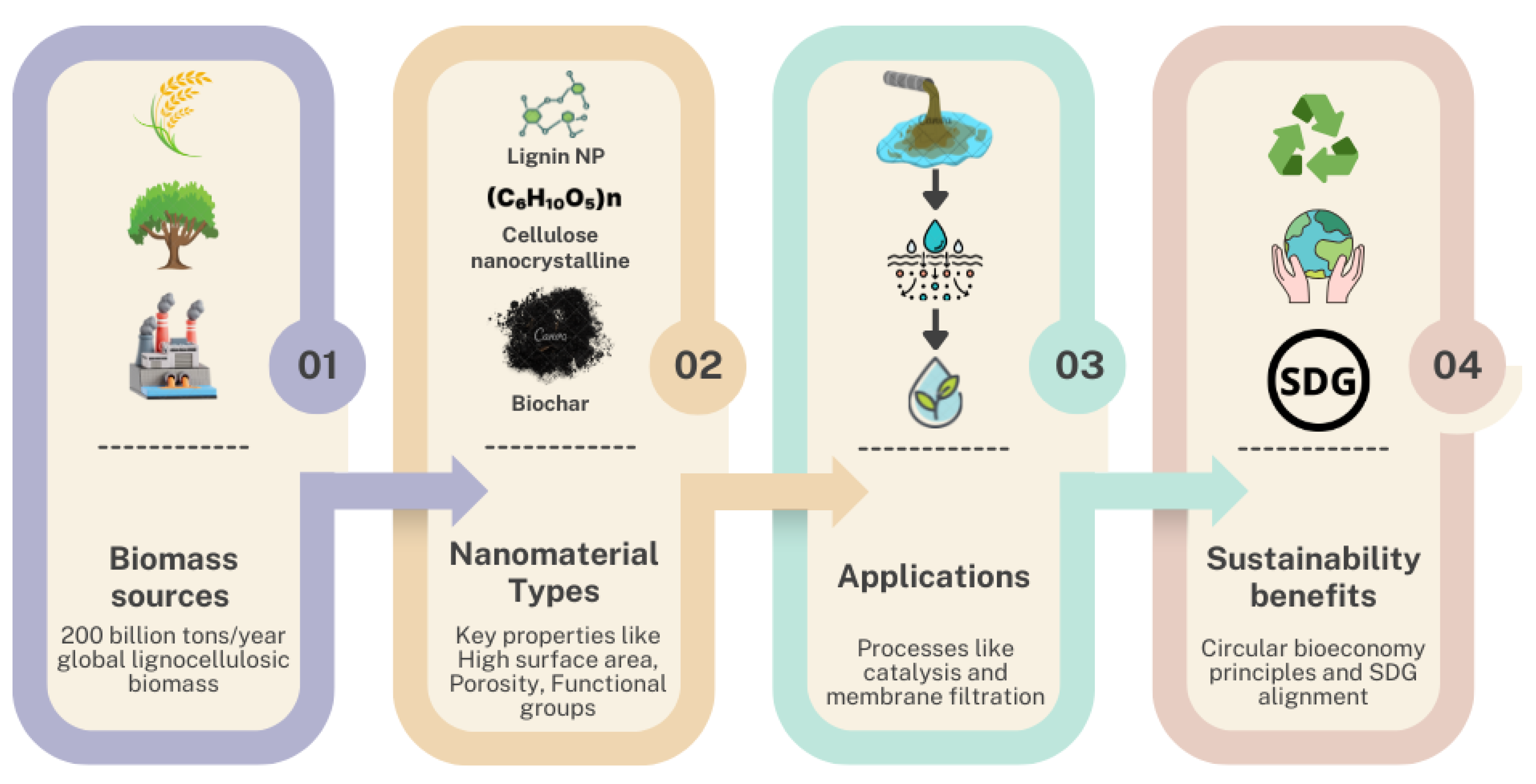

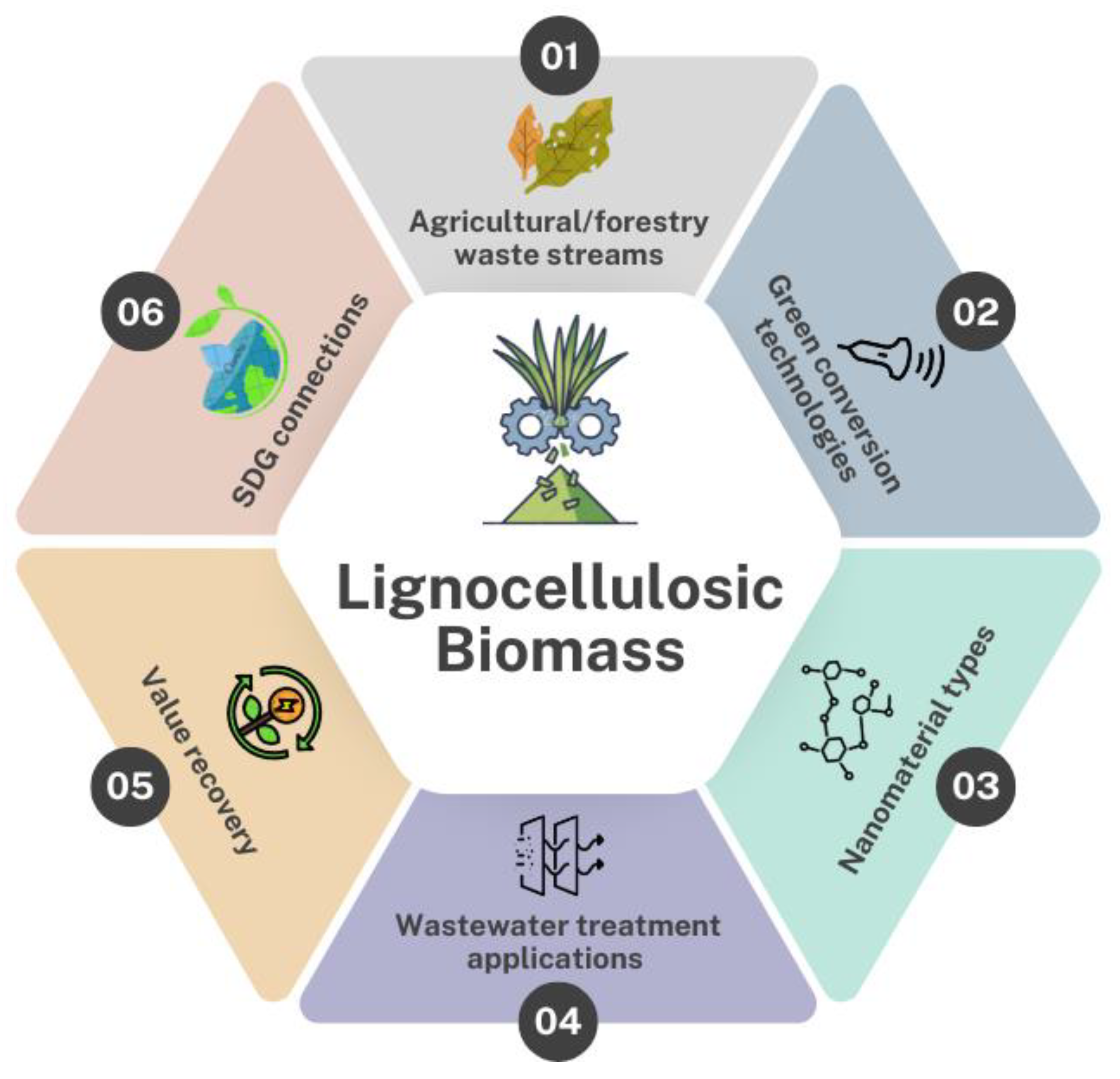

1.1. Lignocellulosic Biomass

1.2. Nanomaterials Derived from Lignocellulosic Biomass

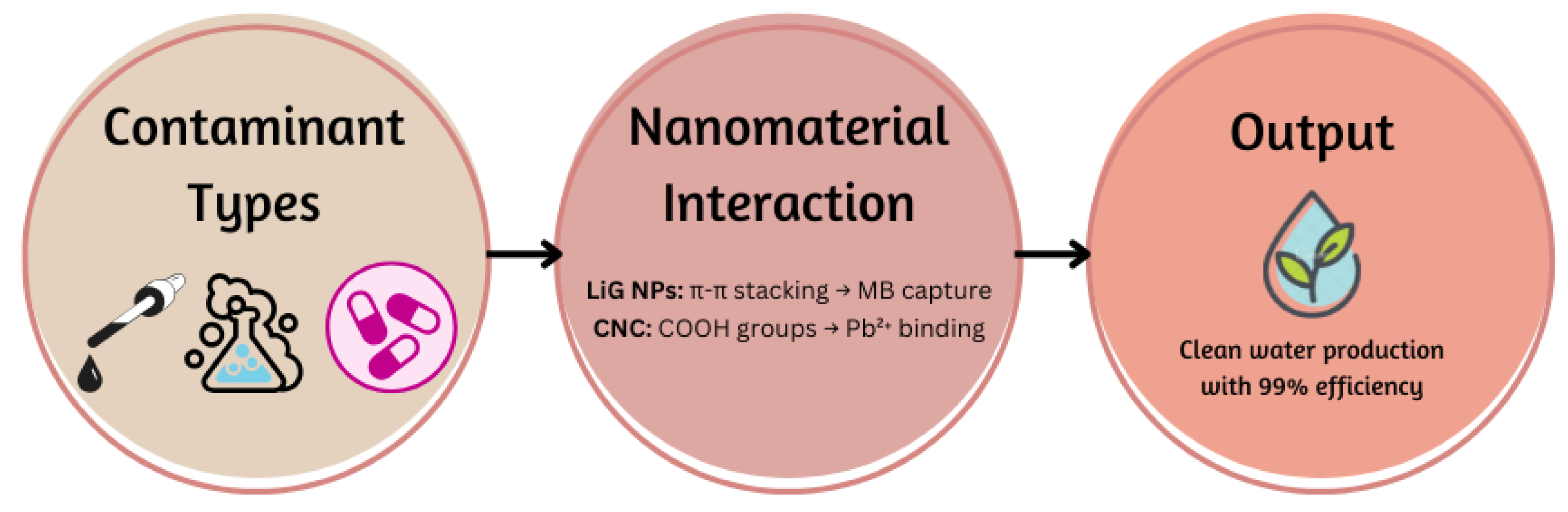

1.3. Nanomaterials in Wastewater Treatment

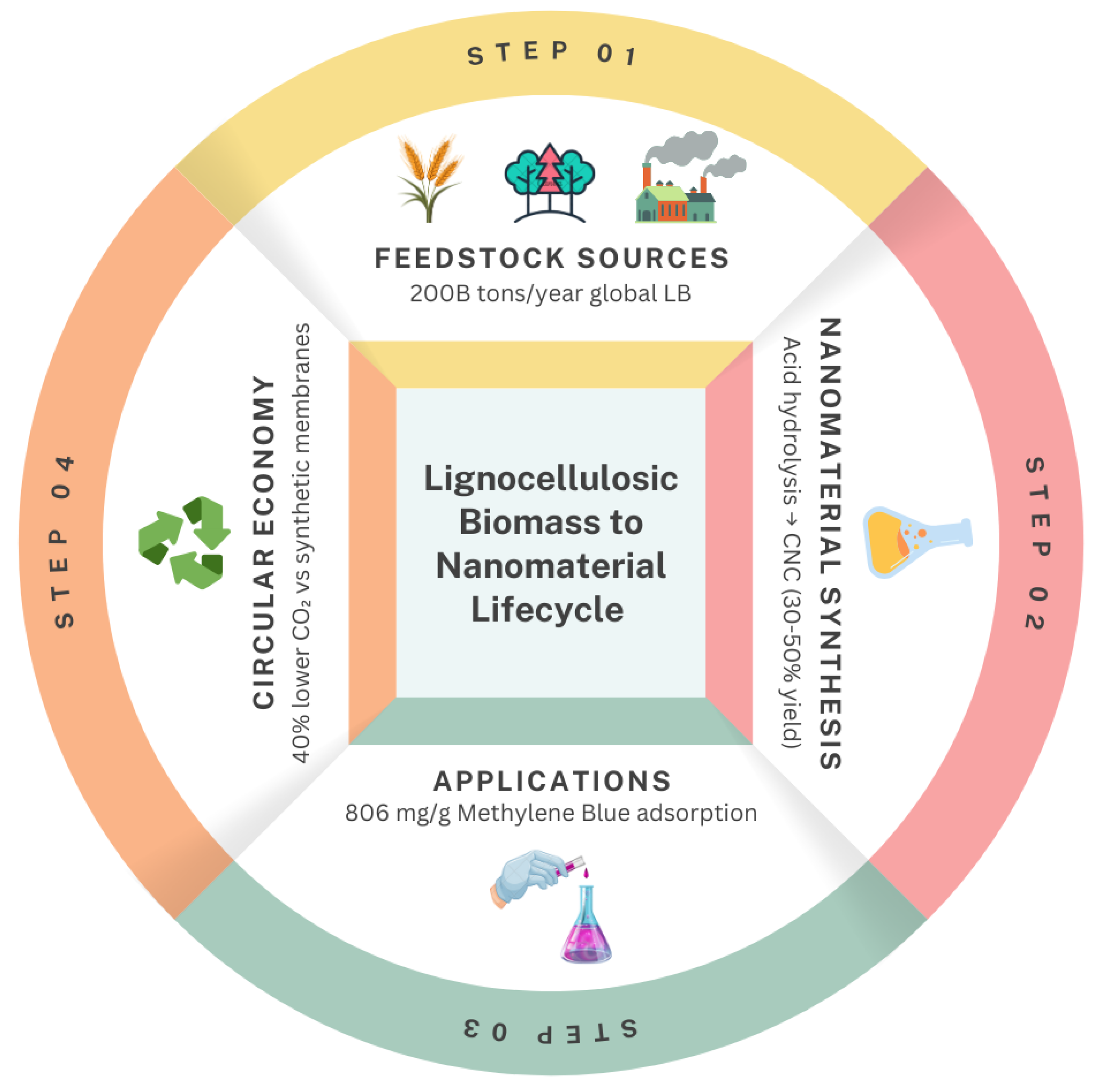

2. Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Renewable Resource

2.1. Sources and Availability

2.2. Structural Composition

2.3. Current Utilization

3. Nanomaterials from Lignocellulosic Waste

3.1. Types of Nanomaterials

3.2. Extraction Techniques

3.3. Properties of Nanomaterials

4. Applications in Wastewater Treatment

4.1. Nanocellulose-Based Composites

4.2. Catalytic Applications

4.3. Lignin Valorization

4.4. Case Studies: Real-World Applications

5. Related Challenges

5.1. Technical Barriers

5.2. Economic Viability

5.3. Environmental Considerations

5.4. Integrated Challenges

6. Innovations and Future Prospects

6.1. Emerging Technologies

6.2. Circular Bioeconomy

6.3. Policy and Industry Support

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Vieira S, Barros MV, Sydney ACN, Piekarski CM, De Francisco AC, Vandenberghe LPDS, et al. Sustainability of sugarcane lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment for the production of bioethanol. Bioresour Technol. 2020 Mar;299:122635. [CrossRef]

- Chandel H, Kumar P, Chandel AK, Verma ML. Biotechnological advances in biomass pretreatment for bio-renewable production through nanotechnological intervention. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2024 Feb;14(3):2959–81. [CrossRef]

- Marriott PE, Gómez LD, McQueen-Mason SJ. Unlocking the potential of lignocellulosic biomass through plant science. New Phytol. 2016 Mar 1;209(4):1366–81.

- Cai J, He Y, Yu X, Banks SW, Yang Y, Zhang X, et al. Review of physicochemical properties and analytical characterization of lignocellulosic biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017 Sep 1;76:309–22. [CrossRef]

- Yousuf A, Pirozzi D, Sannino F. Chapter 1 - Fundamentals of lignocellulosic biomass. In: Yousuf A, Pirozzi D, Sannino F, editors. Lignocellulosic Biomass to Liquid Biofuels [Internet]. Academic Press; 2020. p. 1–15. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128159361000010.

- Bajpai P. Structure of Lignocellulosic Biomass. In: Bajpai P, editor. Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuel Production [Internet]. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2016. p. 7–12. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Mankar AR, Pandey A, Modak A, Pant KK. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: A review on recent advances. Bioresour Technol. 2021 Aug 1;334:125235.

- Brethauer S, Studer MH. Biochemical Conversion Processes of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Fuels and Chemicals – A Review. CHIMIA. 2015 Oct 28;69(10):572. [CrossRef]

- Dutta S, Saravanabhupathy S, Anusha, Rajak RC, Banerjee R, Dikshit PK, et al. Recent Developments in Lignocellulosic Biofuel Production with Nanotechnological Intervention: An Emphasis on Ethanol. Catalysts. 2023 Nov 14;13(11):1439. [CrossRef]

- Okolie JA, Nanda S, Dalai AK, Kozinski JA. Chemistry and Specialty Industrial Applications of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2021 May;12(5):2145–69.

- Amalina F, Syukor Abd Razak A, Krishnan S, Sulaiman H, Zularisam AW, Nasrullah M. Advanced techniques in the production of biochar from lignocellulosic biomass and environmental applications. Clean Mater. 2022 Dec;6:100137. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Xi J, Wang Y. Recent advances in the catalytic production of glucose from lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem. 2015;17(2):737–51. [CrossRef]

- Arif MD, Hoque ME, Rahman MZ, Shafoyat MU. Emerging directions in green nanomaterials: Synthesis, physicochemical properties and applications. Mater Today Commun. 2024 Aug 1;40:109335.

- Rahman S, Sadaf S, Hoque ME, Mishra A, Mubarak NM, Malafaia G, et al. Unleashing the promise of emerging nanomaterials as a sustainable platform to mitigate antimicrobial resistance. RSC Adv. 2024;14(20):13862–99.

- Leng L jian, Yuan X zhong, Huang H jun, Wang H, Wu Z bin, Fu L huan, et al. Characterization and application of bio-chars from liquefaction of microalgae, lignocellulosic biomass and sewage sludge. Fuel Process Technol. 2015 Jan;129:8–14.

- Shukla BK, Sharma PK, Yadav H, Singh S, Tyagi K, Yadav Y, et al. Advanced membrane technologies for water treatment: utilization of nanomaterials and nanoparticles in membranes fabrication. J Nanoparticle Res. 2024 Sep;26(9):222. [CrossRef]

- Choe B, Lee S, Won W. Process integration and optimization for economical production of commodity chemicals from lignocellulosic biomass. Renew Energy. 2020 Dec;162:242–8.

- Mohan D, Sarswat A, Ok YS, Pittman CU. Organic and inorganic contaminants removal from water with biochar, a renewable, low cost and sustainable adsorbent – A critical review. Spec Issue Biosorption. 2014 May 1;160:191–202.

- S Rangabhashiyam, P Balasubramanian. The potential of lignocellulosic biomass precursors for biochar production: Performance, mechanism and wastewater application—A review. Ind Crops Prod. 2019 Feb;128:405–23. [CrossRef]

- Saud A, Gupta S, Allal A, Preud’homme H, Shomar B, Zaidi SJ. Progress in the Sustainable Development of Biobased (Nano)materials for Application in Water Treatment Technologies. ACS Omega. 2024 Jul 9;9(27):29088–113. [CrossRef]

- Renju, Singh R. Re-routing lignocellulosic biomass for the generation of bioenergy and other commodity fractionation in a (Bio)electrochemical system to treat sewage wastewater. Ind Crops Prod. 2024 Dec 15;222:119664.

- Wang H, Zhu S, Elshobary M, Qi W, Wang W, Feng P, et al. Enhancing detoxification of inhibitors in lignocellulosic pretreatment wastewater by bacterial Action: A pathway to improved biomass utilization. Bioresour Technol. 2024 Oct 1;410:131270. [CrossRef]

- Guleria A, Kumari G, Lima EC, Ashish DK, Thakur V, Singh K. Removal of inorganic toxic contaminants from wastewater using sustainable biomass: A review. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Jun 1;823:153689. [CrossRef]

- Rashid AB, Hoque ME, Kabir N, Rifat FF, Ishrak H, Alqahtani A, et al. Synthesis, Properties, Applications, and Future Prospective of Cellulose Nanocrystals. Polymers. 2023 Oct 12;15(20):4070.

- Bhardwaj A, Bansal M, Garima, Wilson K, Gupta S, Dhanawat M. Lignocellulose biosorbents: Unlocking the potential for sustainable environmental cleanup. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025 Mar 1;294:139497. [CrossRef]

- Shoudho KN, Khan TH, Ara UR, Khan MR, Shawon ZBZ, Hoque ME. Biochar in global carbon cycle: Towards sustainable development goals. Curr Res Green Sustain Chem. 2024 Jan 1;8:100409.

- Hoque ME, Shafoyat MU. Biopolymers and Their Composites for Biotechnological Applications. In: Applications of Biopolymers in Science, Biotechnology, and Engineering [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 4]. p. 189–217. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Yadav VK, Gupta N, Kumar P, Dashti MG, Tirth V, Khan SH, et al. Recent Advances in Synthesis and Degradation of Lignin and Lignin Nanoparticles and Their Emerging Applications in Nanotechnology. Materials. 2022 Jan 26;15(3):953. [CrossRef]

- Norfarhana AS, Khoo PS, Ilyas RA, Ab Hamid NH, Aisyah HA, Norrrahim MNF, et al. Exploring of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Lignocellulosic Sources as a Powerful Adsorbent for Wastewater Remediation. J Polym Environ. 2024 Sep;32(9):4071–101.

- Li Y, Bhagwat SS, Cortés-Peña YR, Ki D, Rao CV, Jin YS, et al. Sustainable Lactic Acid Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021 Jan 25;9(3):1341–51. [CrossRef]

- Kumar B, Bhardwaj N, Agrawal K, Chaturvedi V, Verma P. Current perspective on pretreatment technologies using lignocellulosic biomass: An emerging biorefinery concept. Fuel Process Technol. 2020 Mar;199:106244.

- Hassan SS, Williams GA, Jaiswal AK. Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2018 Aug;262:310–8. [CrossRef]

- Dollhofer V, Dandikas V, Dorn-In S, Bauer C, Lebuhn M, Bauer J. Accelerated biogas production from lignocellulosic biomass after pre-treatment with Neocallimastix frontalis. Bioresour Technol. 2018 Sep;264:219–27.

- Singhvi M, Kim BS. Current Developments in Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion into Biofuels Using Nanobiotechology Approach. Energies. 2020 Oct 12;13(20):5300. [CrossRef]

- Motagamwala AH, Won W, Maravelias CT, Dumesic JA. An engineered solvent system for sugar production from lignocellulosic biomass using biomass derived γ-valerolactone. Green Chem. 2016;18(21):5756–63.

- El-Sakhawy M, Kamel S, Tohamy HAS. A Greener Future: Carbon Nanomaterials from Lignocellulose. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(1):21–47. [CrossRef]

- Zhai R, Hu J, Chen X, Xu Z, Wen Z, Jin M. Facile synthesis of manganese oxide modified lignin nanocomposites from lignocellulosic biorefinery wastes for dye removal. Bioresour Technol. 2020 Nov;315:123846.

- Choudhury RR, Sahoo SK, Gohil JM. Potential of bioinspired cellulose nanomaterials and nanocomposite membranes thereof for water treatment and fuel cell applications. Cellulose. 2020 Aug;27(12):6719–46. [CrossRef]

- Jain K, Patel AS, Pardhi VP, Flora SJS. Nanotechnology in Wastewater Management: A New Paradigm Towards Wastewater Treatment. Molecules. 2021 Mar 23;26(6):1797.

- Liu A, Wu H, Naeem A, Du Q, Ni B, Liu H, et al. Cellulose nanocrystalline from biomass wastes: An overview of extraction, functionalization and applications in drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Jun 30;241:124557.

- Kumar A, Kumar V. A Comprehensive Review on Application of Lignocellulose Derived Nanomaterial in Heavy Metals Removal from Wastewater. Chem Afr. 2023 Feb;6(1):39–78. [CrossRef]

- EL-Bestawy E, Hassan SWM, Mohamed AA. Enhanced biodegradation of lignin and lignocellulose constituents in the pulp and paper industry black liquor using integrated magnetite nanoparticles/bacterial assemblage. Appl Water Sci. 2024 Oct;14(10):211. [CrossRef]

- El-Gendy NSh, Nassar HN. Biosynthesized magnetite nanoparticles as an environmental opulence and sustainable wastewater treatment. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Jun;774:145610.

- Ahmad M, Rajapaksha AU, Lim JE, Zhang M, Bolan N, Mohan D, et al. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere. 2014 Mar 1;99:19–33.

- Osman AI, Abdelkader A, Johnston CR, Morgan K, Rooney DW. Thermal Investigation and Kinetic Modeling of Lignocellulosic Biomass Combustion for Energy Production and Other Applications. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2017 Oct 25;56(42):12119–30. [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä M, Benavente V, Fullana A. Hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass: Effect of process conditions on hydrochar properties. Appl Energy. 2015 Oct;155:576–84. [CrossRef]

- Akobi C, Yeo H, Hafez H, Nakhla G. Single-stage and two-stage anaerobic digestion of extruded lignocellulosic biomass. Appl Energy. 2016 Dec;184:548–59.

- Ge X, Xu F, Li Y. Solid-state anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass: Recent progress and perspectives. Bioresour Technol. 2016 Apr;205:239–49.

- Li DC, Jiang H. The thermochemical conversion of non-lignocellulosic biomass to form biochar: A review on characterizations and mechanism elucidation. Bioresour Technol. 2017 Dec;246:57–68. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Chen G, Yan B, Ma W, Cheng Z, Hou L. Exergy analysis of a new lignocellulosic biomass-based polygeneration system. Energy. 2017 Dec;140:1087–95.

- Soares JF, Confortin TC, Todero I, Mayer FD, Mazutti MA. Dark fermentative biohydrogen production from lignocellulosic biomass: Technological challenges and future prospects. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020 Jan;117:109484. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Wang J, Hu Z, Zhu AL, Shen X, Cao X, et al. Harnessing Renewable Lignocellulosic Potential for Sustainable Wastewater Purification. Research. 2024 Jan;7:0347.

- He J, Huang K, Barnett KJ, Krishna SH, Alonso DM, Brentzel ZJ, et al. New catalytic strategies for α,ω-diols production from lignocellulosic biomass. Faraday Discuss. 2017;202:247–67.

- Sharma A, Anjana, Rana H, Goswami S. A Comprehensive Review on the Heavy Metal Removal for Water Remediation by the Application of Lignocellulosic Biomass-Derived Nanocellulose. J Polym Environ. 2022 Jan;30(1):1–18.

- Kim H, Lee S, Ahn Y, Lee J, Won W. Sustainable Production of Bioplastics from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Technoeconomic Analysis and Life-Cycle Assessment. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020 Aug 24;8(33):12419–29. [CrossRef]

- Hartoyo APP, Solikhin A. Valorization of Oil Palm Trunk Biomass for Lignocellulose/Carbon Nanoparticles and Its Nanomaterials Characterization Potential for Water Purification. J Nat Fibers. 2023 Apr 24;20(1):2131688. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gutiérrez E. Biogas production from different lignocellulosic biomass sources: advances and perspectives. 3 Biotech. 2018 May;8(5):233.

- Rai M, Ingle AP, Pandit R, Paralikar P, Biswas JK, Da Silva SS. Emerging role of nanobiocatalysts in hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass leading to sustainable bioethanol production. Catal Rev. 2019 Jan 2;61(1):1–26. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramírez J, Martínez-Hernández JL, Segura-Ceniceros P, López G, Saade H, Medina-Morales MA, et al. Cellulases immobilization on chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles: application for Agave Atrovirens lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2017 Jan 1;40(1):9–22.

- Ahmad M, Lee SS, Dou X, Mohan D, Sung JK, Yang JE, et al. Effects of pyrolysis temperature on soybean stover- and peanut shell-derived biochar properties and TCE adsorption in water. Bioresour Technol. 2012 Aug 1;118:536–44.

- Integrated Composites Laboratory (ICL), Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA, Yuan B, Li L, School of Forest Resources, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5755, USA, Murugadoss V, Integrated Composites Laboratory (ICL), Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA, et al. Nanocellulose-based composite materials for wastewater treatment and waste-oil remediation. ES Food Agrofor [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Mar 2]; Available from: http://www.espublisher.com/journals/articledetails/315.

- Sayyed AJ, Pinjari DV, Sonawane SH, Bhanvase BA, Sheikh J, Sillanpää M. Cellulose-based nanomaterials for water and wastewater treatments: A review. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021 Dec 1;9(6):106626. [CrossRef]

- Salama A, Abouzeid R, Leong WS, Jeevanandam J, Samyn P, Dufresne A, et al. Nanocellulose-Based Materials for Water Treatment: Adsorption, Photocatalytic Degradation, Disinfection, Antifouling, and Nanofiltration. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(11).

- Nasrollahzadeh M, Sajjadi M, Iravani S, Varma RS. Starch, cellulose, pectin, gum, alginate, chitin and chitosan derived (nano)materials for sustainable water treatment: A review. Carbohydr Polym. 2021 Jan 1;251:116986. [CrossRef]

- Pérez H, Quintero García OJ, Amezcua-Allieri MA, Rodríguez Vázquez R. Nanotechnology as an efficient and effective alternative for wastewater treatment: an overview. Water Sci Technol. 2023 Jun 15;87(12):2971–3001. [CrossRef]

- Barhoum A, Jeevanandam J, Rastogi A, Samyn P, Boluk Y, Dufresne A, et al. Plant celluloses, hemicelluloses, lignins, and volatile oils for the synthesis of nanoparticles and nanostructured materials. Nanoscale. 2020;12(45):22845–90. [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz M, Baqar Z, Hussain N, Afifa, Bilal M, Azam HMH, et al. Application of nanomaterials for enhanced production of biodiesel, biooil, biogas, bioethanol, and biohydrogen via lignocellulosic biomass transformation. Fuel. 2022 May 1;315:122840.

- Wilk M, Magdziarz A, Jayaraman K, Szymańska-Chargot M, Gökalp I. Hydrothermal carbonization characteristics of sewage sludge and lignocellulosic biomass. A comparative study. Biomass Bioenergy. 2019 Jan;120:166–75.

- Yang Z, Qian K, Zhang X, Lei H, Xin C, Zhang Y, et al. Process design and economics for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into jet fuel range cycloalkanes. Energy. 2018 Jul;154:289–97. [CrossRef]

- Thanigaivel S, Priya AK, Dutta K, Rajendran S, Sekar K, Jalil AA, et al. Role of nanotechnology for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into biopotent energy: A biorefinery approach for waste to value-added products. Fuel. 2022 Aug 15;322:124236.

- Park SH, Shin SS, Park CH, Jeon S, Gwon J, Lee SY, et al. Poly(acryloyl hydrazide)-grafted cellulose nanocrystal adsorbents with an excellent Cr(VI) adsorption capacity. J Hazard Mater. 2020 Jul 15;394:122512. [CrossRef]

- Mei M, Du P, Li W, Xu L, Wang T, Liu J, et al. Amino-functionalization of lignocellulosic biopolymer to be used as a green and sustainable adsorbent for anionic contaminant removal. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Feb 1;227:1271–81.

- Singha AS, Guleria A. Chemical modification of cellulosic biopolymer and its use in removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014 Jun 1;67:409–17. [CrossRef]

- Godvin Sharmila V, Kumar Tyagi V, Varjani S, Rajesh Banu J. A review on the lignocellulosic derived biochar-based catalyst in wastewater remediation: Advanced treatment technologies and machine learning tools. Bioresour Technol. 2023 Nov 1;387:129587.

- Chon K, Mo Kim Y, Bae S. Advances in Fe-modified lignocellulosic biochar: Impact of iron species and characteristics on wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol. 2024 Mar 1;395:130332. [CrossRef]

- Ghalkhani M, Teymourinia H, Ebrahimi F, Irannejad N, Karimi-Maleh H, Karaman C, et al. Engineering and application of polysaccharides and proteins-based nanobiocatalysts in the recovery of toxic metals, phosphorous, and ammonia from wastewater: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Jul 1;242:124585.

- Isikgor FH, Becer CR. Lignocellulosic biomass: a sustainable platform for the production of bio-based chemicals and polymers. Polym Chem. 2015;6(25):4497–559. [CrossRef]

- Nasir S, Hussein MZ, Zainal Z, Yusof NA. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials/Allotropes: A Glimpse of Their Synthesis, Properties and Some Applications. Materials. 2018;11(2).

- Sawatdeenarunat C, Surendra KC, Takara D, Oechsner H, Khanal SK. Anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass: Challenges and opportunities. Bioresour Technol. 2015 Feb;178:178–86. [CrossRef]

- Alonso DM, Hakim SH, Zhou S, Won W, Hosseinaei O, Tao J, et al. Increasing the revenue from lignocellulosic biomass: Maximizing feedstock utilization. Sci Adv. 2017 3(5):e1603301.

- Tobin T, Gustafson R, Bura R, Gough HL. Integration of wastewater treatment into process design of lignocellulosic biorefineries for improved economic viability. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2020 Dec;13(1):24. [CrossRef]

- Kang KE, Jeong JS, Kim Y, Min J, Moon SK. Development and economic analysis of bioethanol production facilities using lignocellulosic biomass. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019 Oct;128(4):475–9.

- Sakthivel S, Muthusamy K, Thangarajan AP, Thiruvengadam M, Venkidasamy B. Nano-based biofuel production from low-cost lignocellulose biomass: environmental sustainability and economic approach. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2024 Jul;47(7):971–90. [CrossRef]

- Sani A, Savla N, Pandit S, Singh Mathuriya A, Gupta PK, Khanna N, et al. Recent advances in bioelectricity generation through the simultaneous valorization of lignocellulosic biomass and wastewater treatment in microbial fuel cell. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2021 Dec 1;48:101572. [CrossRef]

- Nanda S, Azargohar R, Dalai AK, Kozinski JA. An assessment on the sustainability of lignocellulosic biomass for biorefining. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015 Oct;50:925–41. [CrossRef]

- Hitam CNC, Jalil AA. A review on biohydrogen production through photo-fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2023 Jul;13(10):8465–83. [CrossRef]

| Nanomaterial Type | Source Biomass | Key Properties | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose Nanocrystals | Sugarcane bagasse | Surface area: 500 m2/g; Tensile strength: 220 GPa | Heavy metal adsorption, membranes | [29] |

| Lignin Nanoparticles | Rice straw | Thermal stability: >300°C; Functional groups: -OH, -COOH | Dye removal, catalytic supports | [37] |

| Biochar | Forestry residues | Porosity: 0.8 cm3/g; Adsorption capacity: 806 mg/g | Organic pollutant degradation | [15] |

| Graphene Oxide | Wheat straw | Electrical conductivity: 103 S/m; Surface charge: -25 mV | Photocatalysis, sensors | [36] |

| Magnetic Fe3O4 NPs | Corn stover | Superparamagnetic; Adsorption capacity: 95% Pb(II) | Magnetic recovery systems | [43] |

| Method | Energy Use | Yield (%) | Environmental Impact | Scalability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Hydrolysis | High | 45–60 | Toxic effluent generation | Moderate | [8] |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Low | 30–40 | Biodegradable by-products | High | [28] |

| Pyrolysis | Very High | 50–70 | CO₂ emissions | Low | [45] |

| Microwave-Assisted | Moderate | 55–65 | Reduced solvent use | High | [52] |

| γ-Valerolactone | Low | 60–75 | Solvent recyclability | High | [35] |

| Features | CNC | Lignin NPs | Biochar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock sources | Sugarcane bagasse | Hardwood | Rice husk |

| Key properties | High crystallinity (220 GPa) | Antioxidant and UV-resistant | Mesoporous (500 m2/g) |

| Pollutant removal efficiency | Pb2+ (96% removal) | Methylene blue (806 mg/g) | Zn2+ (85% ion exchange) |

| Cost range | $50-100/kg | $20-50/kg | $5-20/kg |

| Pollutant | Nanomaterial | Removal Efficiency | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb(II) | Carboxylated CNCs | 1,237 mg/g | Electrostatic interaction | [29] |

| Methylene Blue | MnO2-Lignin nanocomposites | 806 mg/g | Chemical adsorption | [37] |

| Cr(VI) | TEMPO-oxidized cellulose | 96% | Redox reaction | [29,71] |

| Tetracycline | CNC-chitosan membranes | 97% | Size exclusion | [20] |

| Cu(II) | Biochar-ZnO hybrid | 92% | Ion exchange | [19] |

| Parameter | Conventional Materials | Lignocellulosic Nanomaterials | Improvement Factor | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production Cost ($/kg) | 1–5 | 20–50 | 4–10x | [62] |

| Carbon Footprint (kg CO2/kg) | 8–12 | 2–4 | 3–4x reduction | [11] |

| Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | 100–300 | 500–1,200 | 2–5x | [41] |

| Reusability Cycles | 3–5 | 8–12 | 2–3x | [52] |

| Functionalization Method | Nanomaterial | Outcome | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEMPO Oxidation | Cellulose nanocrystals | Increased carboxyl groups (-COOH) | Selective Cr(VI) adsorption | [29] |

| MnO₂ Deposition | Lignin NPs | Hierarchical pore structure | Dye degradation | [37] |

| Fe3O4 Coating | Biochar | Magnetic separation capability | Heavy metal recovery | [43] |

| Chitosan Grafting | CNC membranes | Antifouling properties | Oil-water separation | [20] |

| DES Modification | Lignin-carbon | Enhanced dispersibility | Flocculation | [52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).