Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

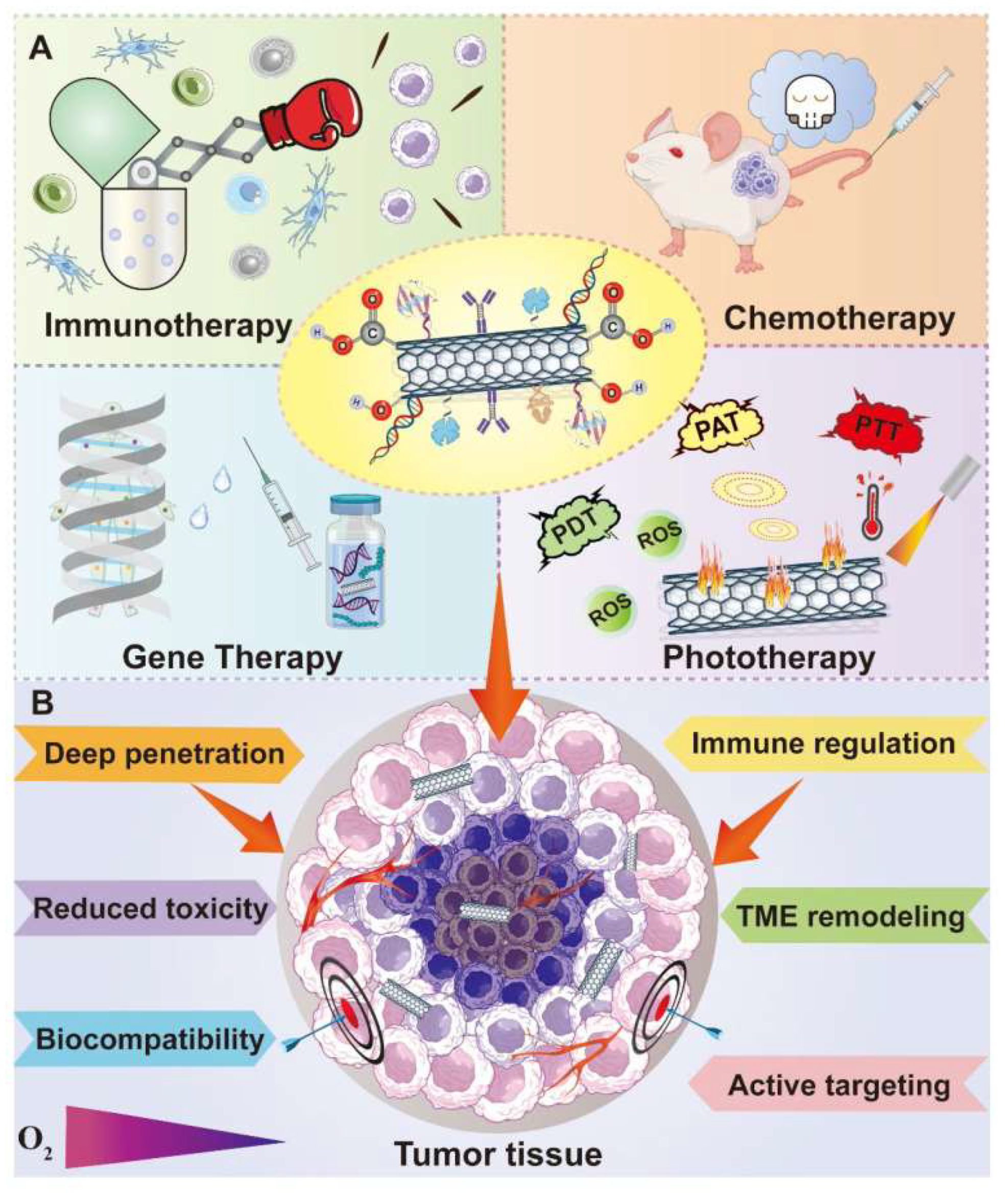

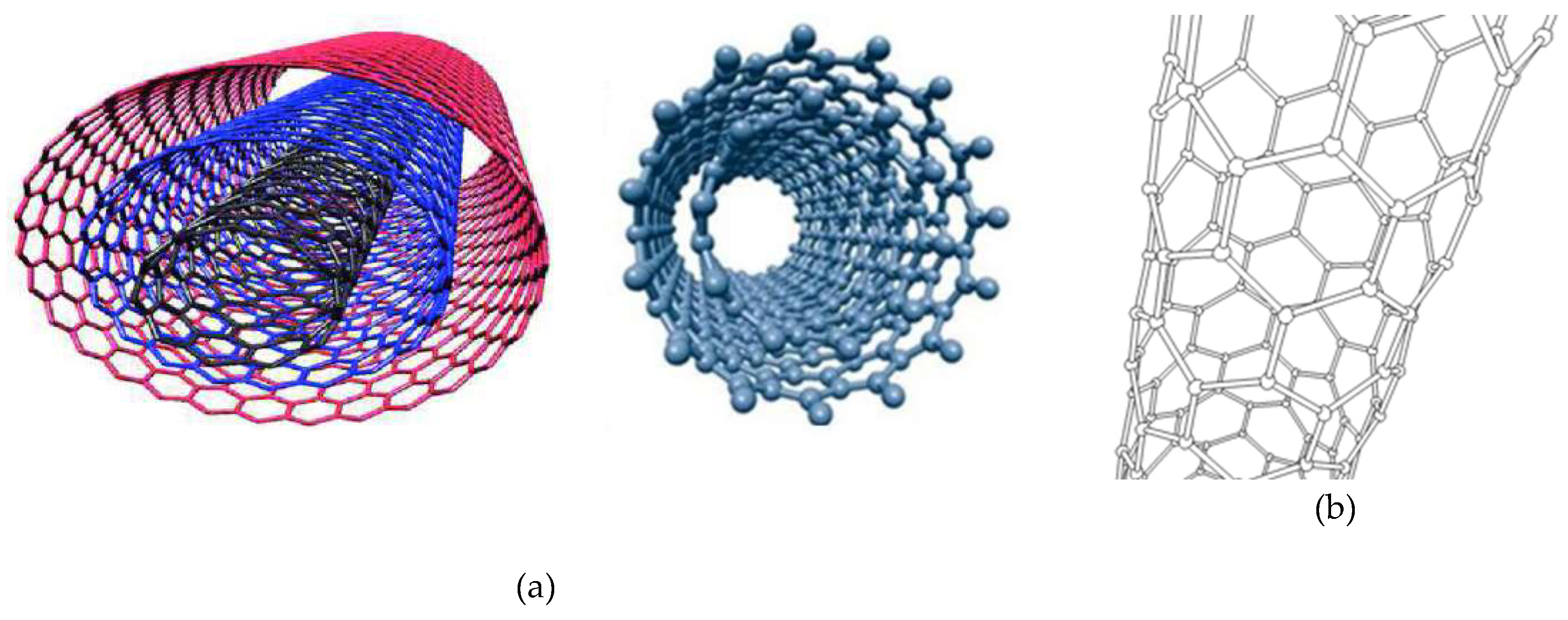

1. Introduction: Carbon Nanotubes in Cancer Therapy

2. Current Synthetic Methods to Obtain CNTs

3. Carbon Nanotubes as Delivery Systems for Anticancer Drugs

- 3.2.2.

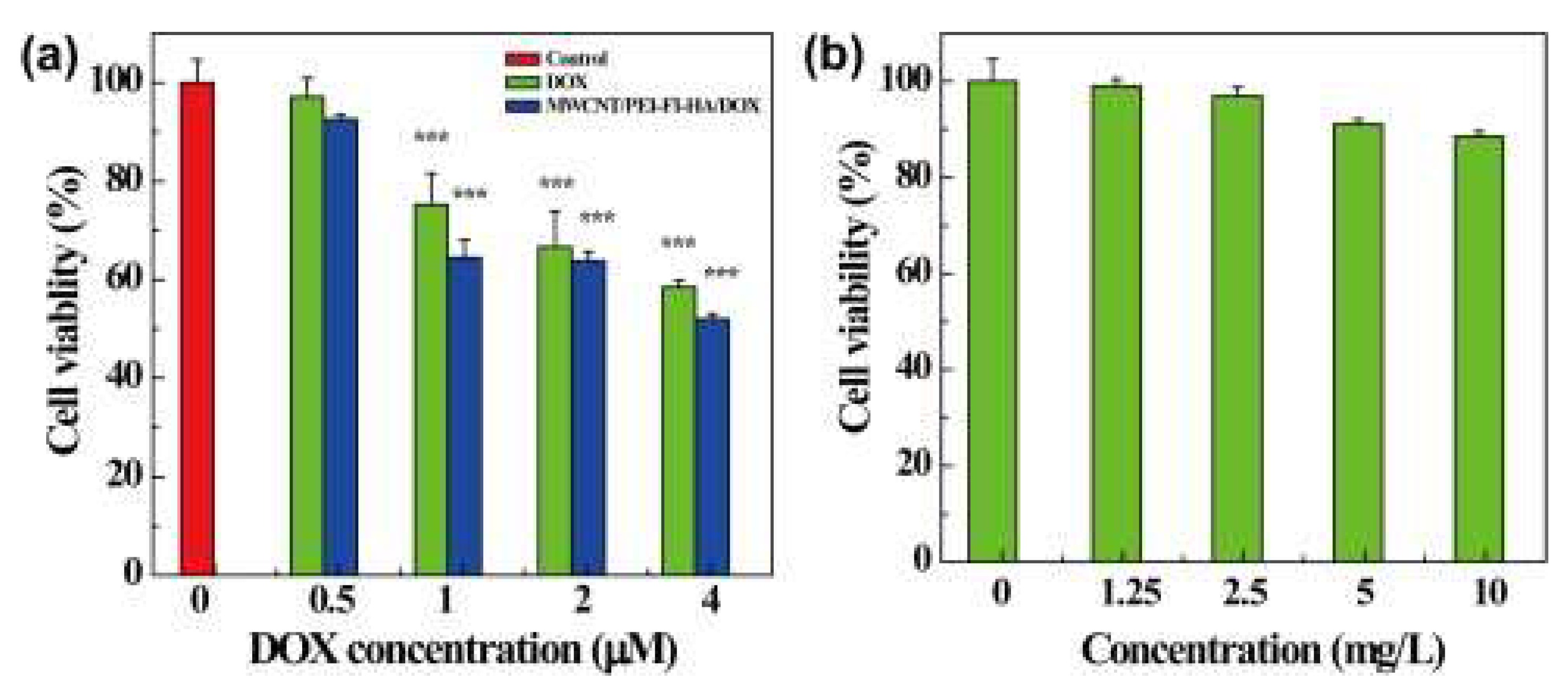

- Carbon Nanotubes-Based Drug Delivery Systems for the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)-Responsive Release of Chemotherapeutics

4. Carbon Nanotubes Application in Anticancer Phototherapy

4.1. Anticancer Photothermal Therapy

4.2. Anticancer Photodynamic Therapy

4.3. Enhanced Anticancer Phototherapies by CNTs-Improved Drug Delivery

4.4. Application of CNTs for Enhanced Anticancer Combined PTT and PDT

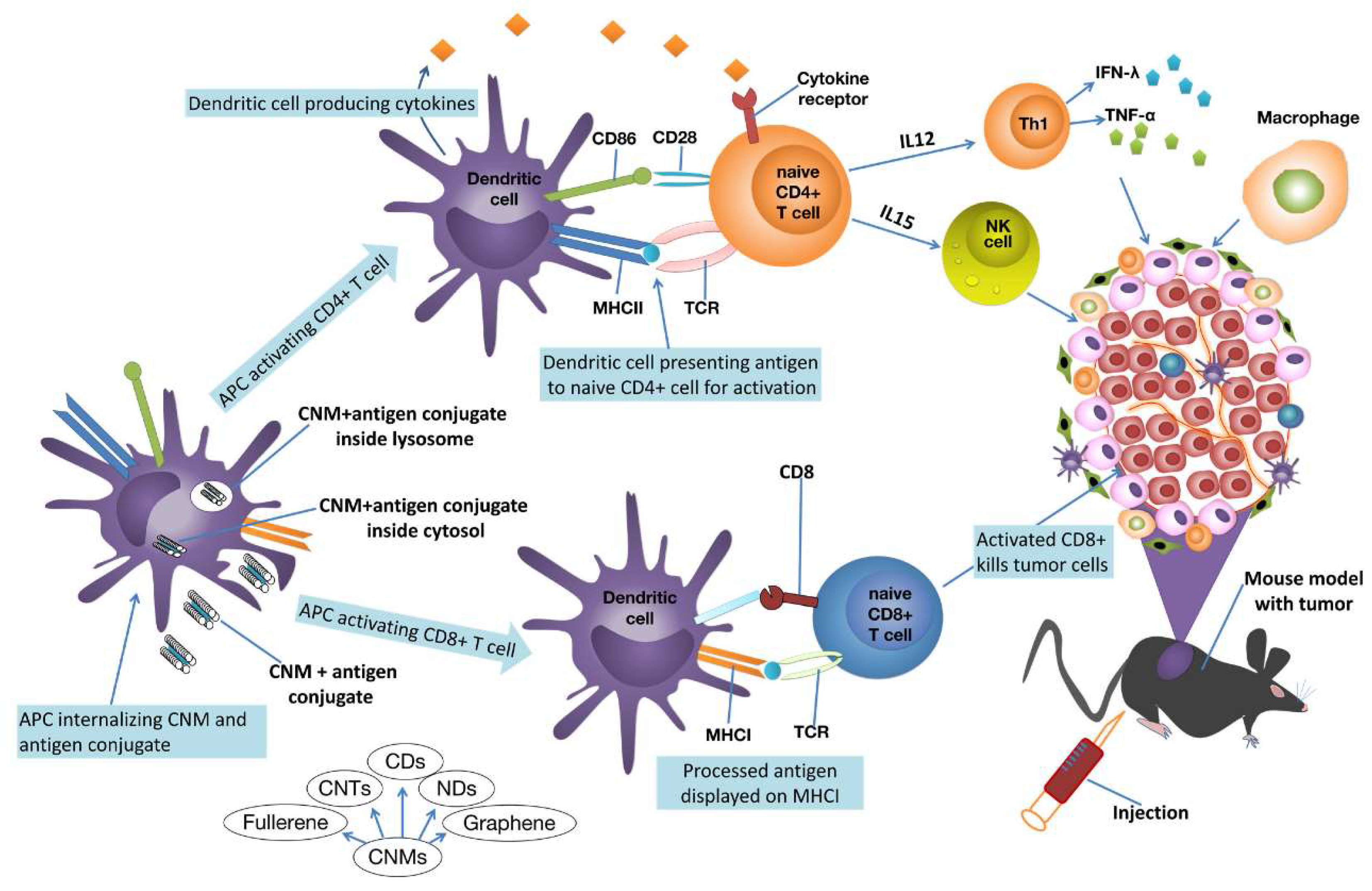

6. Carbon Nanotubes Application in Anticancer Immunotherapy

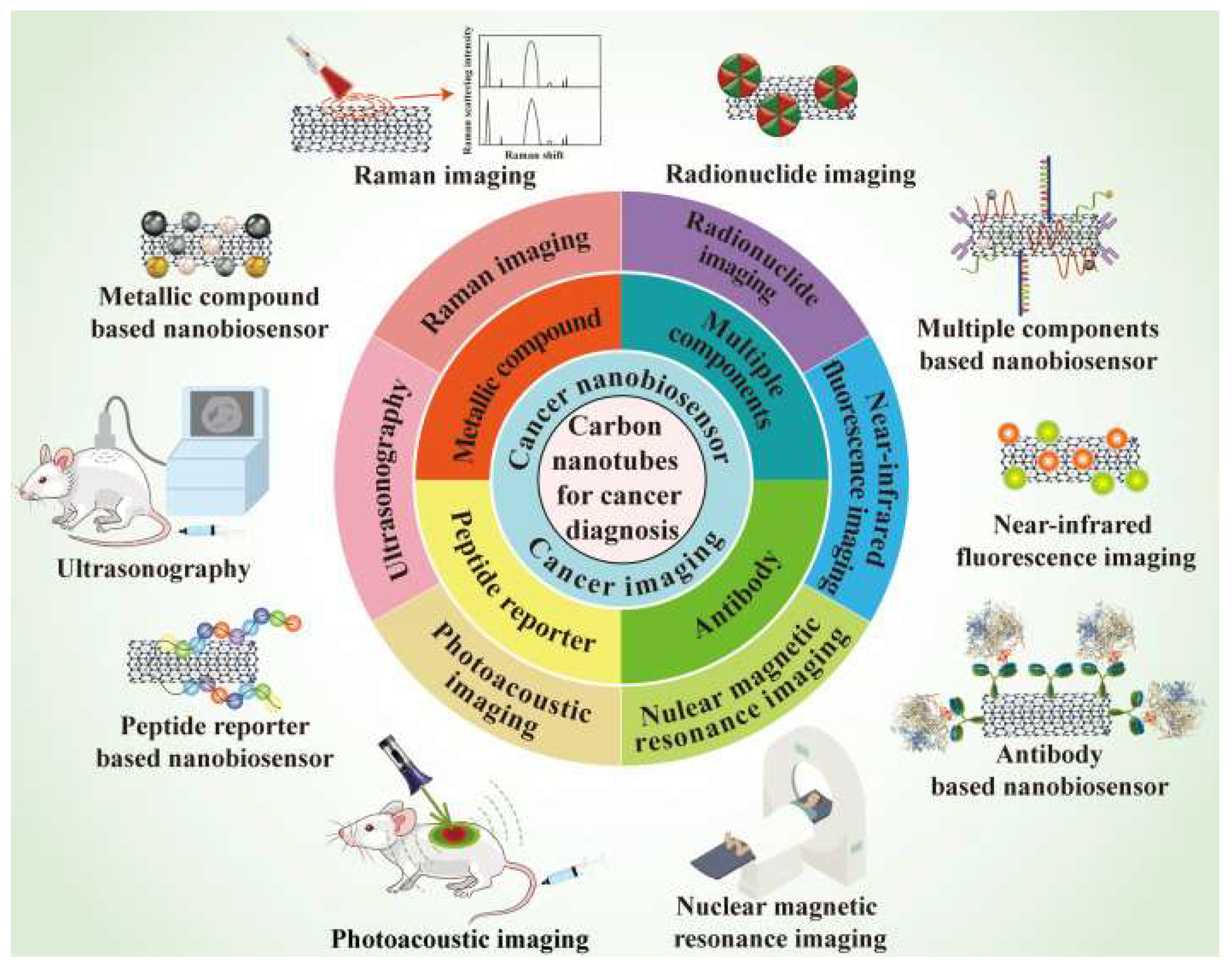

7. Carbon Nanotubes Application in Cancer Diagnosis

7.1. Raman Imaging

7.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging

7.3. Ultrasonography

7.4. Photoacoustic Imaging

7.5. Radionuclide Imaging

7.6. Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging

7.7. CNTs in Nano Biosensors

7.8. CNTs Combination with Metallic Nanoparticles

7.9. CNTs Combination with Antibody

7.10. CNTs Combination with Peptide Reporter

7.11. CNTs Combination with Multiple Modifications

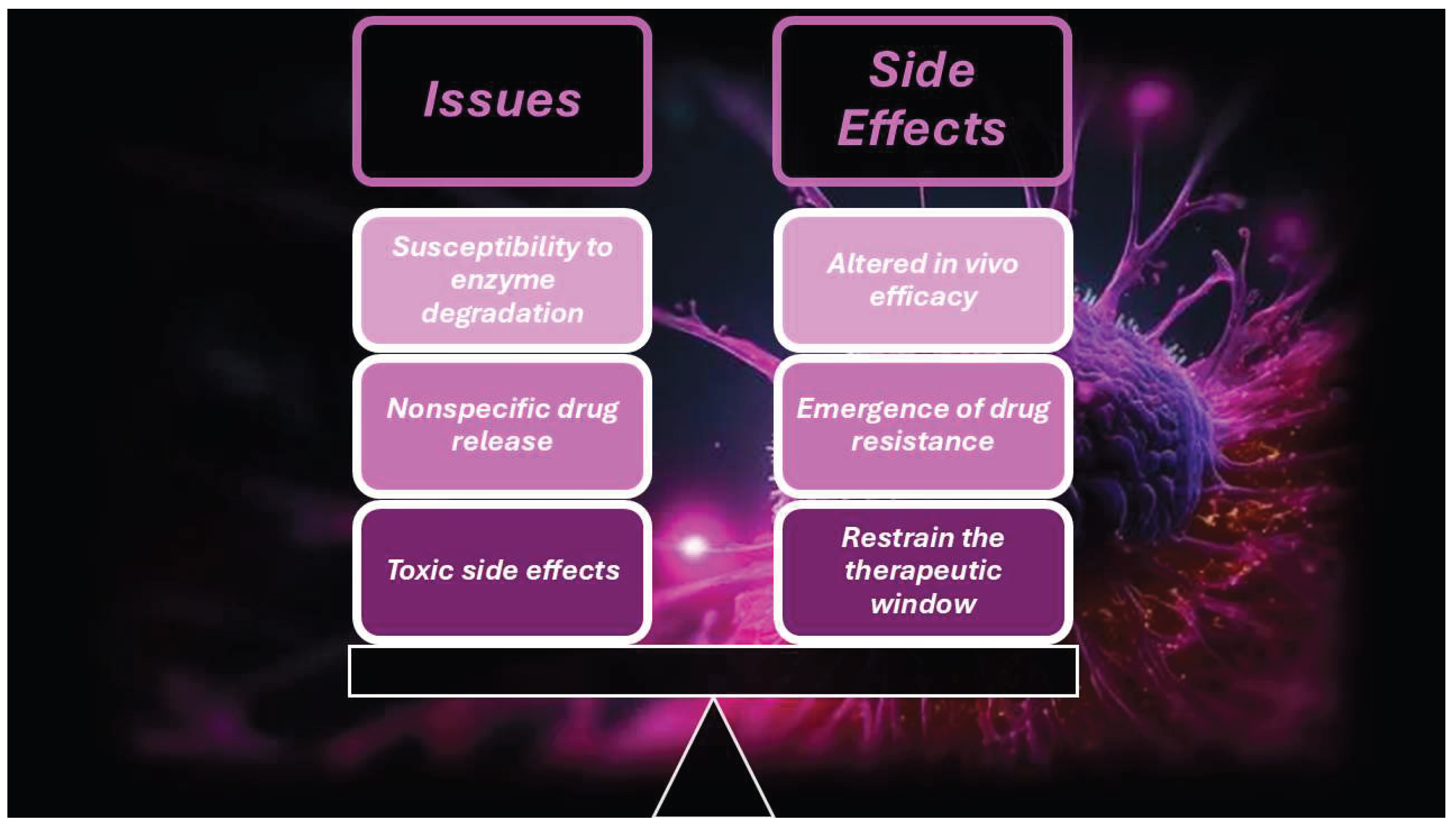

8. Clinical Translatability and Challenges Concerning CNTs

- the mechanisms of action of CNTs on normal cells and tissues are not fully unveiled

- potential toxic effects can occur, due to their special structure

- the mechanisms of CNT-induced toxicity are not fully clarified

- the biodegradability of raw CNTs is too low because their hydrophobic prevents enzymes from approaching them, thus impeding enzymatic degradation

,” “high risk

,” “high risk  ,” or “some concerns

,” or “some concerns  ,” based on specific criteria [290,291]. This assessment processes emphasized the importance of transparency and rigor. Using the Cochrane Risk of Bias, two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias (Table 17).

,” based on specific criteria [290,291]. This assessment processes emphasized the importance of transparency and rigor. Using the Cochrane Risk of Bias, two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias (Table 17).Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Sauer, A.G.; Fedewa, S.A.; Butterly, L.F.; Anderson, J.C.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 2021, 127, 3029–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Prettner, K.; Kuhn, M.; Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Geldsetzer, P.; Bärnighausen, T.; et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories From 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naief, M.F.; Mohammed, S.N.; Mayouf, H.J.; Mohammed, A.M. A review of the role of carbon nanotubes for cancer treatment based on photothermal and photodynamic therapy techniques. J. Organomet. Chem. 2023, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klochkov, S.G.; Neganova, M.E.; Nikolenko, V.N.; Chen, K.; Somasundaram, S.G.; Kirkland, C.E.; Aliev, G. Implications of nanotechnology for the treatment of cancer: Recent advances. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 69, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Cao, X.; Li, M.; Su, Y.; Li, H.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, H.; Xu, X.; Han, Y.; et al. A TRAIL-Delivered Lipoprotein-Bioinspired Nanovector Engineering Stem Cell-Based Platform for Inhibition of Lung Metastasis of Melanoma. Theranostics 2019, 9, 2984–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, J. Lysosome-Independent Intracellular Drug/Gene Codelivery by Lipoprotein-Derived Nanovector for Synergistic Apoptosis-Inducing Cancer-Targeted Therapy. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Massagué, J. Targeting metastatic cancer. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibaie, M.; Hajighasemi, E.; Adeli-Sardou, M.; Doostmohammadi, M.; Forootanfar, H. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities of Bi subnitrate and BiNPs produced by Delftia sp. SFG against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis. IET Nanobiotechnology 2019, 13, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.N.; Al-Rawi, K.F.; Mohammed, A.M. Kinetic evaluation and study of gold-based nanoparticles and multi-walled carbon nanotubes as an alkaline phosphatase inhibitor in serum and pure form. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naief, M.F.; Mohammed, A.M.; Khalaf, Y.H. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of ALP enzyme in the presence and absence MWCNTs and Pt-NPs nanocomposites. Results Chem. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naief, M.F.; Ahmed, Y.N.; Mohammed, A.M.; Mohammed, S.N. Novel preparation method of fullerene and its ability to detect H2S and NO2 gases. Results Chem. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naief, M.F.; Mohammed, S.N.; Ahmed, Y.N.; Mohammed, A.M. Synthesis and characterisation of MWCNTCOOH and investigation of its potential as gas sensor. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Z.A.A.; Mohammed, A.M.; Abbass, N.M. Synthesis and characterization of polymer nanocomposites from methyl acrylate and metal chloride and their application. Polym. Bull. 2019, 77, 5879–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, O.H.; Mohammed, A.M. GREEN SYNTHESIS OF AuNPs FROM THE LEAF EXTRACT OF PROSOPIS FARCTA FOR ANTIBACTERIAL AND ANTI-CANCER APPLICATIONS. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2020, 15, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, G.A.; Najm, M.A.; Hussein, A.L. The Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on Braf Gene Expression. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.M.; Saud, W.M.; Ali, M.M. GREEN SYNTHESIS OF Fe2O3 NANOPARTICLES USING OLEA EUROPAEA LEAF EXTRACT AND THEIR ANTIBACTERIAL ACTIVITY. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2020, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwied, D.H.; Nayef, U.M.; Mutlak, F.A.-H. Synthesis of C:Se nanoparticles ablated on porous silicon for sensing NO2 and NH3 gases. Optik 2021, 241, 167013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaee, M.F.; Yaaqoob, L.A.; Kamona, Z.K. Evaluation of the Biological Activity of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles as Antibacterial and Anticancer Agents. Iraqi J. Sci. 2020, 2888–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghdeeb, N.J.; AbdulMajeed, A.M.; Mohammed, A.H. Role of Extracted Nano-metal Oxides From Factory Wastes In Medical Applications. Iraqi J. Sci. 2023, 1704–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A.A.; Alsalami, K.A.S.; Athbi, A.M. Cytotoxic effects of CeO2 NPs and β-Carotene and their ability to induce apoptosis in human breast normal and cancer cell lines. Iraqi J. Sci. 2022, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.A.; Abdo, G.M. Water Conservation in the Arab Region. In Water, Energy and Food Sustainability in the Middle East: The Sustainability Triangle; 2017.

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, G.C. Antimicrobial Nanotubes: From Synthesis and Promising Antimicrobial Upshots to Unanticipated Toxicities, Strategies to Limit Them, and Regulatory Issues. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, G.C. Nanotubes: Carbon-Based Fibers and Bacterial Nano-Conduits Both Arousing a Global Interest and Conflicting Opinions. Fibers 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Haider, Q.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, H.; Baili, J.; Aljahdaly, N.H.; Hassan, A. A thermal conductivity model for hybrid heat and mass transfer investigation of single and multi-wall carbon nano-tubes flow induced by a spinning body. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobamowo, M.; Akanmu, J.; Adeleye, O.; Akingbade, S.; Yinusa, A. Coupled effects of magnetic field, number of walls, geometric imperfection, temperature change, and boundary conditions on nonlocal nonlinear vibration of carbon nanotubes resting on elastic foundations. Forces Mech. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Carbon Nanomaterials: 30 Years of Research in Agroecosystems. In Carbon Nanomaterials for Agri-Food and Environmental Applications; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 1–18.

- Anzar, N.; Hasan, R.; Tyagi, M.; Yadav, N.; Narang, J. Carbon nanotube—A review on Synthesis, Properties and plethora of applications in the field of biomedical science. Sens. Int. 2020, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, V.; Pacheco-Torres, J.; Calle, D.; López-Larrubia, P. Carbon Nanotubes in Biomedicine. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020, 378, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, M.; Pedata, P.; Sannolo, N.; Porto, S.; De Rosa, A.; Caraglia, M. Carbon nanotubes: Properties, biomedical applications, advantages and risks in patients and occupationally-exposed workers. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2015, 28, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rani, R.; Dilbaghi, N.; Tankeshwar, K.; Kim, K.-H. Carbon nanotubes: a novel material for multifaceted applications in human healthcare. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 46, 158–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Gan, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Carbon dots derived from pea for specifically binding with Cryptococcus neoformans. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 589, 113476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, S.; Jafari, S.M. Application of nanofluids for thermal processing of food products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Dougherty, C.A.; Zhu, K.; Hong, H. Theranostic applications of carbon nanomaterials in cancer: Focus on imaging and cargo delivery. J. Control. Release 2015, 210, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.K.; Leung, A.W.N.; Xu, C.; Au, D.C.T. Is It Possible for Curcumin to Conjugate with a Carbon Nanotube in Photodynamic Therapy? Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, M.A.; Jeon, J.-Y.; Ha, T.-J. Carbon nanotubes: An effective platform for biomedical electronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 150, 111919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.M.; Bourgognon, M.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Al-Jamal, K.T. Functionalised carbon nanotubes: From intracellular uptake and cell-related toxicity to systemic brain delivery. J. Control. Release 2016, 241, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, A.; Kaushik, A.; Vashist, A.; Sagar, V.; Ghosal, A.; Gupta, Y.K.; Ahmad, S.; Nair, M. Advances in Carbon Nanotubes–Hydrogel Hybrids in Nanomedicine for Therapeutics. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2018, 7, e1701213–e1701213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, G.; Vittorio, O.; Kunhardt, D.; Valli, E.; Voli, F.; Farfalla, A.; Curcio, M.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Hampel, S. Combining Carbon Nanotubes and Chitosan for the Vectorization of Methotrexate to Lung Cancer Cells. Materials 2019, 12, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, J. Novel Span-PEG Multifunctional Ultrasound Contrast Agent Based on CNTs as a Magnetic Targeting Factor and a Drug Carrier. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 31525–31534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, R.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Palos, M.; Cebolla, V.L.; Osada, J.; Muñoz, E.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J. Toxicity of Carbon Nanomaterials and Their Potential Application as Drug Delivery Systems: In Vitro Studies in Caco-2 and MCF-7 Cell Lines. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corletto, A.; Shapter, J.G. Nanoscale Patterning of Carbon Nanotubes: Techniques, Applications, and Future. Adv. Sci. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Hashemi, H.; Feng, J.; Jafari, S.M. Carbon nanomaterials against pathogens; the antimicrobial activity of carbon nanotubes, graphene/graphene oxide, fullerenes, and their nanocomposites. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 284, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Zuccari, G. Carbon-Nanotube-Based Nanocomposites in Environmental Remediation: An Overview of Typologies and Applications and an Analysis of Their Paradoxical Double-Sided Effects. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, O.G.; O'Byrne, J.P.; Torrente-Murciano, L.; Jones, M.D.; Mattia, D.; McManus, M.C. Identifying the largest environmental life cycle impacts during carbon nanotube synthesis via chemical vapour deposition. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 42, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, D.; Wu, C.; Gu, S. State-of-the-art on the production and application of carbon nanomaterials from biomass. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 5031–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, M.R.; Elkhenany, H.; Hafez, I.H.; El-Badawy, A.; Essawy, M.; El-Badri, N. Efficient Tailoring of Platinum Nanoparticles Supported on Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for Cancer Therapy. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Song, L.; Zhou, S.; Hu, M.; Jiao, Y.; Teng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Enhanced ultrasound imaging and anti-tumor in vivo properties of Span–polyethylene glycol with folic acid–carbon nanotube–paclitaxel multifunctional microbubbles. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 35345–35355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadpour, N.; Ranjbar, A.; Azarpira, N.; Sattarahmady, N. Development of a Composite of Polypyrrole-Coated Carbon Nanotubes as a Sonosensitizer for Treatment of Melanoma Cancer Under Multi-Step Ultrasound Irradiation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 2322–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Shen, S.; She, X.; Shi, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Pang, Z.; Jiang, X. Fibrin-targeting peptide CREKA-conjugated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for self-amplified photothermal therapy of tumor. Biomaterials 2016, 79, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, Z.; Behnam, M.A.; Emami, F.; Dehghanian, A.; Jamhiri, I. Photothermal therapy of melanoma tumor using multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, ume 12, 4509–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosca, F.; Corazzari, I.; Foglietta, F.; Canaparo, R.; Durando, G.; Pastero, L.; Arpicco, S.; Dosio, F.; Zonari, D.; Cravotto, G.; et al. SWCNT–porphyrin nano-hybrids selectively activated by ultrasound: an interesting model for sonodynamic applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 21736–21744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, S. Cancer Targeting and Diagnosis: Recent Trends with Carbon Nanotubes. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizaji, B.F.; Khoshbakht, S.; Farboudi, A.; Azarbaijan, M.H.; Irani, M. Far-reaching advances in the role of carbon nanotubes in cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2020, 257, 118059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, K.H.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, J.W. Carbon nanotubes as cancer therapeutic carriers and mediators. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, ume 11, 5163–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-R.; Lin, R.; Li, H.-J.; He, W.; Du, J.-Z.; Wang, J. Strategies to improve tumor penetration of nanomedicines through nanoparticle design. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 11, e1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Meng, K.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Qu, W.; Chen, D.; Xie, S. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of nanocarriers in vivo and their influences. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 284, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, H.; Ahmadi, S.; Ghasemi, A.; Ghanbari, M.; Rabiee, N.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Karimi, M.; Webster, T.J.; Hamblin, M.R.; Mostafavi, E. Carbon Nanotubes: Smart Drug/Gene Delivery Carriers. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.; Nia, A.H.; Abnous, K.; Ramezani, M. Polyethylenimine-functionalized carbon nanotubes tagged with AS1411 aptamer for combination gene and drug delivery into human gastric cancer cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 516, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-P.; Lin, I.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Lee, M.-J. Delivery of small interfering RNAs in human cervical cancer cells by polyethylenimine-functionalized carbon nanotubes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 267–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhirde, A.A.; Chikkaveeraiah, B.V.; Srivatsan, A.; Niu, G.; Jin, A.J.; Kapoor, A.; Wang, Z.; Patel, S.; Patel, V.; Gorbach, A.M.; et al. Targeted Therapeutic Nanotubes Influence the Viscoelasticity of Cancer Cells to Overcome Drug Resistance. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, X.; Dong, X.; Liu, L.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, H. Transactivator of transcription (TAT) peptide–chitosan functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes as a potential drug delivery vehicle for cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, ume 10, 3829–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Blais, M.-O.; Harris, G.M.; Jabbarzadeh, E. Correction: PLGA-Carbon Nanotube Conjugates for Intercellular Delivery of Caspase-3 into Osteosarcoma Cells. PLOS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chiou, S.-H.; Chou, C.-P.; Chen, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-J.; Peng, C.-A. Photothermolysis of glioblastoma stem-like cells targeted by carbon nanotubes conjugated with CD133 monoclonal antibody. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2011, 7, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, N.; Lu, S.; Wickstrom, E.; Panchapakesan, B. Integrated molecular targeting of IGF1R and HER2 surface receptors and destruction of breast cancer cells using single wall carbon nanotubes. Nanotechnology 2007, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.; Park, S.B.; Yoon, E.; Yoo, H.M.; Lee, D.; Heo, J.-N.; Ahn, S. αVβ3-Targeted Delivery of Camptothecin-Encapsulated Carbon Nanotube-Cyclic RGD in 2D and 3D Cancer Cell Culture. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 3704–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhirde, A.A.; Patel, V.; Gavard, J.; Zhang, G.; Sousa, A.A.; Masedunskas, A.; Leapman, R.D.; Weigert, R.; Gutkind, J.S.; Rusling, J.F. Targeted Killing of Cancer Cellsin Vivoandin Vitrowith EGF-Directed Carbon Nanotube-Based Drug Delivery. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

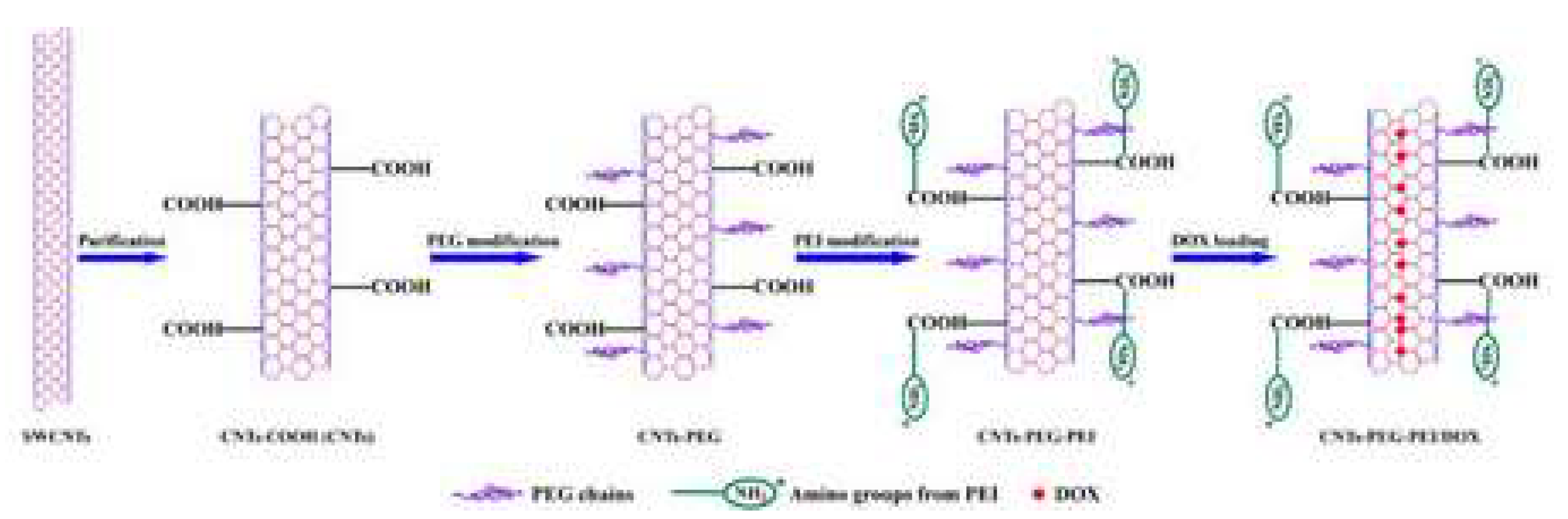

- Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Ping, Y.; Miao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Qu, L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J. PEG/PEI-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes as delivery carriers for doxorubicin: synthesis, characterization, and in vitro evaluation. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 11, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Nakayama-Ratchford, N.; Dai, H. Supramolecular Chemistry on Water-Soluble Carbon Nanotubes for Drug Loading and Delivery. ACS Nano 2007, 1, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahamathulla, M.; Bhosale, R.R.; Osmani, R.A.M.; Mahima, K.C.; Johnson, A.P.; Hani, U.; Ghazwani, M.; Begum, M.Y.; Alshehri, S.; Ghoneim, M.M.; et al. Carbon Nanotubes: Current Perspectives on Diverse Applications in Targeted Drug Delivery and Therapies. Materials 2021, 14, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Patharkar, A.; Kuche, K.; Maheshwari, R.; Deb, P.K.; Kalia, K.; Tekade, R.K. Functionalized carbon nanotubes as emerging delivery system for the treatment of cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 548, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, A.; Mansouri, A.; Azamat, J. Molecular dynamics simulation of non-covalent single-walled carbon nanotube functionalization with surfactant peptides. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2016, 64, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnain, M.S.; Ahmad, S.A.; Hoda, M.N.; Rishishwar, S.; Rishishwar, P.; Nayak, A.K. Stimuli-responsive carbon nanotubes for targeted drug delivery. In Stimuli Responsive Polymeric Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery Application; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tao, L.; Wen, S.; Hou, W.; Shi, X. Hyaluronic acid-modified multiwalled carbon nanotubes for targeted delivery of doxorubicin into cancer cells. Carbohydr. Res. 2015, 405, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Gu, Y.-J.; Jin, J.; Cheng, S.H.; Wong, W.-T. Development and evaluation of pH-responsive single-walled carbon nanotube-doxorubicin complexes in cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 2889–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Javaid, F.; Chudasama, V. Advances in targeting the folate receptor in the treatment/imaging of cancers. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 790–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-J.; Wei, K.-C.; Ma, C.-C.M.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chen, J.-P. Dual targeted delivery of doxorubicin to cancer cells using folate-conjugated magnetic multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2012, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feazell, R.P.; Nakayama-Ratchford, N.; Dai, H.; Lippard, S.J. Soluble Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Longboat Delivery Systems for Platinum(IV) Anticancer Drug Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 8438–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, S.; Kunze, D.; Haase, D.; Krämer, K.; Rauschenbach, M.; Ritschel, M.; Leonhardt, A.; Thomas, J.; Oswald, S.; Hoffmann, V.; et al. Carbon Nanotubes Filled with a Chemotherapeutic Agent: A Nanocarrier Mediates Inhibition of Tumor Cell Growth. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Man, C.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Ma, Q.; Cai, Y.; Ma, W. PEGylated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Encapsulation and Sustained Release of Oxaliplatin. Pharm. Res. 2012, 30, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; He, Z.; Li, S. Effect of intratumoral injection on the biodistribution and therapeutic potential of novel chemophor EL-modified single-walled nanotube loading doxorubicin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2012, 38, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Boucetta, H.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; McCarthy, D.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A.; Kostarelos, K. Multiwalled carbon nanotube–doxorubicin supramolecular complexes for cancer therapeutics. Chem. Commun. 2007, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Wu, R.; Zhao, L.; Wu, M.; Yang, L.; Zou, H. P-Glycoprotein Antibody Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Overcomes the Multidrug Resistance of Human Leukemia Cells. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, N.; Arora, A.; Vasu, K.S.; Sood, A.K.; Katti, D.S. Combination of single walled carbon nanotubes/graphene oxide with paclitaxel: a reactive oxygen species mediated synergism for treatment of lung cancer. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 2818–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Meng, L.; Lu, Q.; Fei, Z.; Dyson, P.J. Targeted delivery and controlled release of doxorubicin to cancer cells using modified single wall carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6041–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atyabi, F.; Sobhani, Z.; Adeli, M.; Dinarvand, R.; Ghahremani, M. Increased paclitaxel cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines using a novel functionalized carbon nanotube. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 705–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, K.; Davis, C.; Sherlock, S.; Cao, Q.; Chen, X.; Dai, H. Drug Delivery with Carbon Nanotubes forIn vivoCancer Treatment. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 6652–6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Kuznetsova, L.V.; Wong, S.S.; Ojima, I. Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Rationally Designed Vehicles for Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16778–16785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzazan, A.; Atyabi, F.; Kazemi, B.; Dinarvand, R. In vivo drug delivery of gemcitabine with PEGylated single-walled carbon nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater Biol. Appl. 2016, 62, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeusz, G.; Cherukuri, P.; Kingston, J.; Cognet, L.; Lemos, R.; Leeuw, T.K.; Gumbiner-Russo, L.; Weisman, R.B.; Powis, G. In vivo therapeutic silencing of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) using single-walled carbon nanotubes noncovalently coated with siRNA. Nano Res. 2009, 2, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkouhi, A.K.; Foillard, S.; Lammers, T.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Doris, E.; Hennink, W.E.; Storm, G. SiRNA delivery with functionalized carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 416, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Targeted RNA Interference of Cyclin A2 Mediated by Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Induces Proliferation Arrest and Apoptosis in Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia K562 Cells. ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Al-Jamal, W.T.; Toma, F.M.; Bianco, A.; Prato, M.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Kostarelos, K. Design of Cationic Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes as Efficient siRNA Vectors for Lung Cancer Xenograft Eradication. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Samorì, C.; Toma, F.M.; Bussy, C.; Nunes, A.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Prato, M.; Kostarelos, K.; Bianco, A. Polyamine functionalized carbon nanotubes: Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity and siRNA binding. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 4850–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Salmasi, Z.; Hashemi, M.; Mosaffa, F.; Abnous, K.; Ramezani, M. Single-walled carbon nanotubes functionalized with aptamer and piperazine–polyethylenimine derivative for targeted siRNA delivery into breast cancer cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 485, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jamal, K.T.; Toma, F.M.; Yilmazer, A.; Ali-Boucetta, H.; Nunes, A.; Herrero, M.; Tian, B.; Eddaoudi, A.; Al-Jamal, W.; Bianco, A.; et al. Enhanced cellular internalization and gene silencing with a series of cationic dendron-multiwalled carbon nanotube:siRNA complexes. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 4354–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podesta, J.E.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Herrero, M.A.; Tian, B.; Ali-Boucetta, H.; Hegde, V.; Bianco, A.; Prato, M.; Kostarelos, K. Antitumor Activity and Prolonged Survival by Carbon-Nanotube-Mediated Therapeutic siRNA Silencing in a Human Lung Xenograft Model. Small 2009, 5, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battigelli, A.; Wang, J.T.; Russier, J.; Da Ros, T.; Kostarelos, K.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A. Ammonium and Guanidinium Dendron–Carbon Nanotubes by Amidation and Click Chemistry and their Use for siRNA Delivery. Small 2013, 9, 3610–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shi, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C.; et al. RETRACTED: Synergistic anticancer effect of RNAi and photothermal therapy mediated by functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Jiang, X.; Deng, Z.; Narain, R. Cationic Glyco-Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Efficient Gene Delivery Vehicles. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009, 20, 2017–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biris, A.; Karmakar, A.; Braton, S.M.; Dervishi, E.; Ghosh, A.; Mahmood, M.; Saeed, L.M.; Mustafa, T.; Casciano, D.; Pandya, R. Ethylenediamine functionalized-single-walled nanotube (f-SWNT)-assisted in vitro delivery of the oncogene suppressor p53 gene to breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantarotto, D.; Singh, R.; McCarthy, D.; Erhardt, M.; Briand, J.; Prato, M.; Kostarelos, K.; Bianco, A. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes for Plasmid DNA Gene Delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 5242–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Yang, K.; Tang, H.; Tan, L.; Xie, Q.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. Improved GFP gene transfection mediated by polyamidoamine dendrimer-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes with high biocompatibility. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2011, 84, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yang, R.; Chen, Y. Multi-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes as tumor cell targeting biological transporters. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2007, 10, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Ding, L.; Yan, F.; Ji, H.; Ju, H. The use of polyethylenimine-grafted graphene nanoribbon for cellular delivery of locked nucleic acid modified molecular beacon for recognition of microRNA. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3875–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crinelli, R.; Carloni, E.; Menotta, M.; Giacomini, E.; Bianchi, M.; Ambrosi, G.; Giorgi, L.; Magnani, M. Oxidized Ultrashort Nanotubes as Carbon Scaffolds for the Construction of Cell-Penetrating NF-κB Decoy Molecules. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Cui, D.; Xu, P.; Ozkan, C.; Feng, G.; Ozkan, M.; Huang, T.; Chu, B.; Li, Q.; He, R.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of polyamidoamine dendrimer-coated multi-walled carbon nanotubes and their application in gene delivery systems. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossche, J.V.D.; Al-Jamal, W.T.; Tian, B.; Nunes, A.; Fabbro, C.; Bianco, A.; Prato, M.; Kostarelos, K. Efficient receptor-independent intracellular translocation of aptamers mediated by conjugation to carbon nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7379–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, Y.; Sun, R.; Song, T.; Shi, X.; Yin, S. Stacking of doxorubicin on folic acid-targeted multiwalled carbon nanotubes for in vivo chemotherapy of tumors. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Du, Y.; Su, H.; Cheng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, Y.; Qi, X.-R. Interfacial properties and micellization of triblock poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-caprolactone)-polyethyleneimine copolymers. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, N.; Alihosseini, A.; Pirouzfar, V.; Pedram, M.Z. Analysis of Dynamics Targeting CNT-Based Drug Delivery through Lung Cancer Cells: Design, Simulation, and Computational Approach. Membranes 2020, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Huang, H.-Y.; Chen, L.-Q.; Du, H.-H.; Cui, J.-H.; Zhang, L.W.; Lee, B.-J.; Cao, Q.-R. Enhanced Lysosomal Escape of pH-Responsive Polyethylenimine–Betaine Functionalized Carbon Nanotube for the Codelivery of Survivin Small Interfering RNA and Doxorubicin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 9763–9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Yang, S.; Wei, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, D.; Pu, X.; He, S.; Zhang, Y. Construction of Aptamer-siRNA Chimera/PEI/5-FU/Carbon Nanotube/Collagen Membranes for the Treatment of Peritoneal Dissemination of Drug-Resistant Gastric Cancer. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2020, 9, e2001153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Domínguez, J.; Grasa, L.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; Abás, E.; Domínguez-Alfaro, A.; Mesonero, J.; Criado, A.; Ansón-Casaos, A. Intrinsic and selective activity of functionalized carbon nanotube/nanocellulose platforms against colon cancer cells. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2022, 212, 112363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. A precision-guided MWNT mediated reawakening the sunk synergy in RAS for anti-angiogenesis lung cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2017, 139, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwameer, M.R.; Salman, S.A.; Noori, F.T.M.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Jabir, M.S.; Khalil, K.A.A.; Ahmed, E.M.; Soliman, M.T.A. Antiproliferative Activity of PEG-PEI-SWCNTs against AMJ13 Breast Cancer Cells. J. Nanomater. 2023, 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, J.; Pan, T.; Yin, Y.; Mei, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, R.; Yan, Z.; Wang, W. Versatile carbon nanoplatforms for cancer treatment and diagnosis: strategies, applications and future perspectives. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2290–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harisa, G.I.; Faris, T.M. Direct Drug Targeting into Intracellular Compartments: Issues, Limitations, and Future Outlook. J. Membr. Biol. 2019, 252, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Mei, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, S.; Xiao, Q.; Yin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shao, J.; Wang, W.; Cai, Z. Nanoparticle-Mediated Targeted Drug Delivery to Remodel Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, ume 16, 5811–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, F.; Su, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W. Nanoparticles designed to regulate tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2018, 201, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymak, I.; Williams, K.S.; Cantor, J.R.; Jones, R.G. Immunometabolic Interplay in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2020, 39, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Faraj, A.; Shaik, A.S.; Al Sayed, B.; Halwani, R.; Al Jammaz, I. Specific Targeting and Noninvasive Imaging of Breast Cancer Stem Cells Using Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Novel Multimodality Nanoprobes. Nanomedicine 2015, 11, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, T.; Zhi, D.; Zhang, E.; Zhong, F.; Zhen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S. Integrin αvβ3-targeted liposomal drug delivery system for enhanced lung cancer therapy. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 201, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, T.; Cao, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, H.; Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhen, Y.; Liang, X.-J.; et al. Temperature-Sensitive Lipid-Coated Carbon Nanotubes for Synergistic Photothermal Therapy and Gene Therapy. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6517–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.-H.; Shang, W.-T.; Deng, H.; Han, Z.-Y.; Hu, M.; Liang, X.-Y.; Fang, C.-H.; Zhu, X.-H.; Fan, Y.-F.; Tian, J. Targeting carbon nanotubes based on IGF-1R for photothermal therapy of orthotopic pancreatic cancer guided by optical imaging. Biomaterials 2019, 195, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Ding, W.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Microwave pumped high-efficient thermoacoustic tumor therapy with single wall carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.A.; Smyth, L.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Costa, P.M.; Ratnasothy, K.; Diebold, S.S.; Lombardi, G.; Al-Jamal, K.T. Dual stimulation of antigen presenting cells using carbon nanotube-based vaccine delivery system for cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2016, 104, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lian, L.; Huang, H.; Guo, L.; Chen, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Wan, L.; et al. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes co-delivering sorafenib and epidermal growth factor receptor siRNA enhanced tumor-suppressing effect on liver cancer. Aging 2021, 13, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, V.; Heister, E.; Costa, S.; Tîlmaciu, C.; Flahaut, E.; Soula, B.; Coley, H.M.; McFadden, J.; Silva, S.R.P. Design of double-walled carbon nanotubes for biomedical applications. Nanotechnol. 2012, 23, 365102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Jin, J.-O.; Oh, J. Photothermal-triggered control of sub-cellular drug accumulation using doxorubicin-loaded single-walled carbon nanotubes for the effective killing of human breast cancer cells. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C.; Chiou, Y.-C.; Wong, J.-M.; Peng, C.-L.; Shieh, M.-J. Targeting colorectal cancer cells with single-walled carbon nanotubes conjugated to anticancer agent SN-38 and EGFR antibody. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8756–8765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, S.L.; Wong, B.S.; Zhou, Q.L.; Chin, C.F.; Li, J.; Venkatesan, T.; Ho, H.K.; Yu, V.; Ang, W.H.; Pastorin, G. Enhanced cytotoxicity to cancer cells by mitochondria-targeting MWCNTs containing platinum(IV) prodrug of cisplatin. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-W.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Hong, J.H.; Khang, D. PEGylated anticancer-carbon nanotubes complex targeting mitochondria of lung cancer cells. Nanotechnol. 2017, 28, 465102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ruan, L.; Zheng, T.; Wang, D.; Zhou, M.; Lu, H.; Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y. A surface convertible nanoplatform with enhanced mitochondrial targeting for tumor photothermal therapy. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2020, 189, 110854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Wu, S.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, W.R.; Xing, D. Mitochondria-Targeting Photoacoustic Therapy Using Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Small 2012, 8, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, I.; Silva, A.A.K.; Guilbert, T.; Kolosnjaj-Tabi, J.; Marchiol, C.; Natkhunarajah, S.; Chamming'S, F.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Bianco, A.; Gennisson, J.-L.; et al. Tumor Stiffening, a Key Determinant of Tumor Progression, is Reversed by Nanomaterial-Induced Photothermal Therapy. Theranostics 2017, 7, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pan, Y.; Ren, J.; Ye, M.; Xia, F.; Huang, R.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, S.; Songyang, Z.; et al. Single-walled carbon nanotube: One specific inhibitor of cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma upon downregulation of the TGFβ1 signaling. Biomaterials 2017, 149, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Nariya, P.; Joshi, A.; Vohra, A.; Devkar, R.; Seshadri, S.; Thakore, S. Carbon nanotube embedded cyclodextrin polymer derived injectable nanocarrier: A multiple faceted platform for stimulation of multi-drug resistance reversal. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, H.; Ji, D. Carbon nanotubes (CNT)-loaded ginsenosides Rb3 suppresses the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in triple-negative breast cancer. Aging 2021, 13, 17177–17189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Jing, H.; Dong, X.; Leng, X. MWCNT-mediated combinatorial photothermal ablation and chemo-immunotherapy strategy for the treatment of melanoma. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 4245–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.W.; Bae, Y.H. EPR: Evidence and fallacy. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhier, F. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: Since the EPR effect fails in the clinic, what is the future of nanomedicine? J. Control. Release 2016, 244, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasey, P.A.; Kaye, S.B.; Morrison, R.; Twelves, C.; Wilson, P.; Duncan, R.; Thomson, A.H.; Murray, L.S.; Hilditch, T.E.; Murray, T.; et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of PK1 [N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer doxorubicin]: first member of a new class of chemotherapeutic agents-drug-polymer conjugates. Cancer Research Campaign Phase I/II Committee. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, Y.; Maeda, H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: Mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 6387–6392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.G.; Surendran, S.P.; Jeong, Y.Y. Tumor Microenvironment-Stimuli Responsive Nanoparticles for Anticancer Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Mu, T.; Qin, H.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Sui, L. A large-inner-diameter multi-walled carbon nanotube-based dual-drug delivery system with pH-sensitive release properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, N.; Jing, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Meng, L. A tumor-microenvironment fully responsive nano-platform for MRI-guided photodynamic and photothermal synergistic therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8271–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, J.; Bi, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, H.; Gao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z. Near-infrared light remote-controlled intracellular anti-cancer drug delivery using thermo/pH sensitive nanovehicle. Acta Biomater. 2015, 17, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, A.C.; Hoover, A.R.; Layton, E.; Murray, C.K.; Howard, E.W.; Chen, W.R. Nanomaterial Applications in Photothermal Therapy for Cancer. Materials 2019, 12, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, A.J.; Tunnell, J.W. Combinatorial immunotherapy and nanoparticle mediated hyperthermia. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 114, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, P.; Abrahamse, H. Phototherapy Combined with Carbon Nanomaterials (1D and 2D) and Their Applications in Cancer Therapy. Materials 2020, 13, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Su, L.; Liu, S.; Shi, X.; Han, D.; Liang, F. Decorating gold nanostars with multiwalled carbon nanotubes for photothermal therapy. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKernan, P.; Virani, N.A.; Faria, G.N.F.; Karch, C.G.; Silvy, R.P.; Resasco, D.E.; Thompson, L.F.; Harrison, R.G. Targeted Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Photothermal Therapy Combined with Immune Checkpoint Inhibition for the Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachilo, S.M.; Balzano, L.; Herrera, J.E.; Pompeo, F.; Resasco, D.E.; Weisman, R.B. Narrow (n,m)-Distribution of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Grown Using a Solid Supported Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11186–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Xing, D.; Ou, Z.; Wu, B.; Resasco, D.E.; Chen, W.R. Cancer photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009, 14, 021009–021009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, R.; Fish, R.J.; Casini, A.; Neerman-Arbez, M. Fibrin(ogen) in human disease: both friend and foe. Haematologica 2020, 105, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Shen, S.; She, X.; Shi, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Pang, Z.; Jiang, X. Fibrin-targeting peptide CREKA-conjugated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for self-amplified photothermal therapy of tumor. Biomaterials 2016, 79, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.N.; Mohammed, A.M.; Al-Rawi, K.F. Novel combination of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and gold nanocomposite for photothermal therapy in human breast cancer model. Steroids 2022, 186, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naief, M.F.; Khalaf, Y.H.; Mohammed, A.M. Novel photothermal therapy using multi-walled carbon nanotubes and platinum nanocomposite for human prostate cancer PC3 cell line. J. Organomet. Chem. 2022, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doix, B.; Trempolec, N.; Riant, O.; Feron, O. Low Photosensitizer Dose and Early Radiotherapy Enhance Antitumor Immune Response of Photodynamic Therapy-Based Dendritic Cell Vaccination. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbodu, R.O.; Limson, J.L.; Prinsloo, E.; Nyokong, T. Photophysical properties and photodynamic therapy effect of zinc phthalocyanine-spermine-single walled carbon nanotube conjugate on MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Synth. Met. 2015, 204, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbodu, R.O.; Nyokong, T. The effect of ascorbic acid on the photophysical properties and photodynamic therapy activities of zinc phthalocyanine-single walled carbon nanotube conjugate on MCF-7 cancer cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 151, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, P.; Abrahamse, H. Effective Photodynamic Therapy for Colon Cancer Cells Using Chlorin e6 Coated Hyaluronic Acid-Based Carbon Nanotubes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, K.H.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, J.W. Carbon nanotubes as cancer therapeutic carriers and mediators. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, ume 11, 5163–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ma, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Gao, J.; Li, L.; Hou, L.; et al. The application of hyaluronic acid-derivatized carbon nanotubes in hematoporphyrin monomethyl ether-based photodynamic therapy for in vivo and in vitro cancer treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 2361–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dheyab, M.A.; Aziz, A.A.; Khaniabadi, P.M.; Jameel, M.S.; Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Rahman, A.A.; Braim, F.S.; Mehrdel, B. Gold nanoparticles-based photothermal therapy for breast cancer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 42, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ren, Y.; Shao, Y.; Yu, D.; Meng, L. Facile Preparation of Doxorubicin-Loaded and Folic Acid-Conjugated Carbon Nanotubes@Poly(N-vinyl pyrrole) for Targeted Synergistic Chemo–Photothermal Cancer Treatment. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 2815–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Erfan, M.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Ghorbani-Bidkorbeh, F.; Kobarfard, F.; Shirazi, F.H. Functionalisation of carbon nanotubes by methotrexate and study of synchronous photothermal effect of carbon nanotube and anticancer drug on cancer cell death. IET Nanobiotechnology 2018, 13, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yi, W.; Hou, J.; Yoo, S.; Jin, W.; Yang, Q. A carbon nanotube-gemcitabine-lentinan three-component composite for chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy of cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, ume 13, 3069–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Akhmetova, A.; Kulsharova, G. Multifunctional Hybrid Nanoparticles for Theranostics. Core-Shell Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostics: Challenges, Strategies and Prospects for Novel Carrier Systems 2018, 177–244. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Erfan, M.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Ghorbani-Bidkorbeh, F.; Landi, B.; Kobarfard, F.; Shirazi, F.H. The Photothermal Effect of Targeted Methotrexate-Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on MCF7 Cells. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Xing, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C. 3D CNT/MXene microspheres for combined photothermal/photodynamic/chemo for cancer treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 996177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

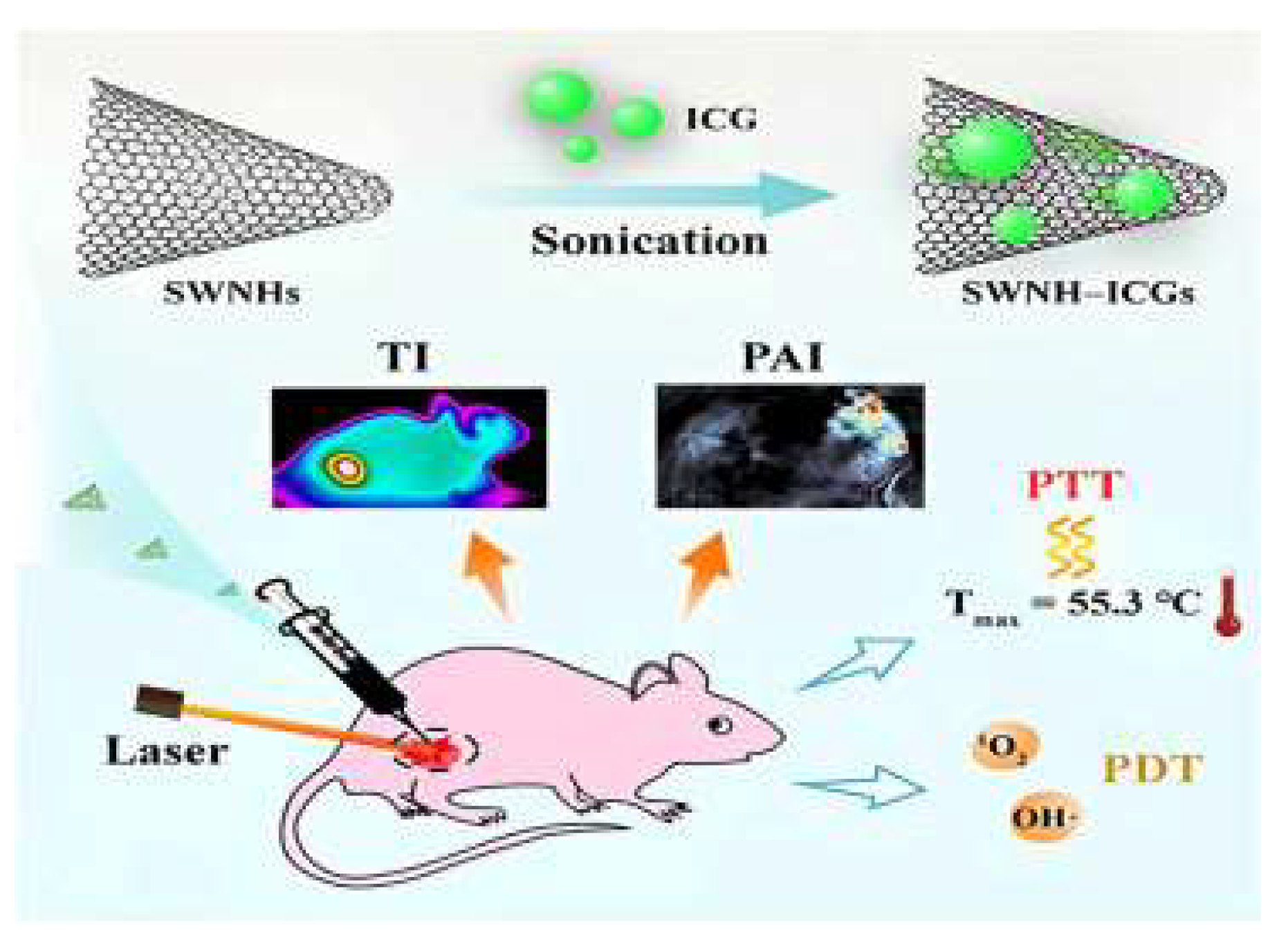

- Gao, C.; Dong, P.; Lin, Z.; Guo, X.; Jiang, B.; Ji, S.; Liang, H.; Shen, X. Near-Infrared Light Responsive Imaging-Guided Photothermal and Photodynamic Synergistic Therapy Nanoplatform Based on Carbon Nanohorns for Efficient Cancer Treatment. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12827–12837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Jian, J.; Lin, Z.; Yu, Y.-X.; Jiang, B.-P.; Chen, H.; Shen, X.-C. Hypericin-Loaded Carbon Nanohorn Hybrid for Combined Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy in Vivo. Langmuir 2019, 35, 8228–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Hou, M.; Sun, W.; Wu, Q.; Xu, J.; Xiong, L.; Chai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Sequential PDT and PTT Using Dual-Modal Single-Walled Carbon Nanohorns Synergistically Promote Systemic Immune Responses against Tumor Metastasis and Relapse. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.; Chen, D.; Zou, J.; Shao, J.; Tang, H.; Xu, H.; Si, W.; Dong, X. Tumor Microenvironment Responsive Oxygen-Self-Generating Nanoplatform for Dual-Imaging Guided Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 4366–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Cui, Y.; Chu, X.; Sun, B.; Zhou, N.; Shen, J. Magnetofluorescent Fe3O4/carbon quantum dots coated single-walled carbon nanotubes as dual-modal targeted imaging and chemo/photodynamic/photothermal triple-modal therapeutic agents. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 338, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, I.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Silva, A.K.; Bianco, A.; Luciani, N.; Gazeau, F. Synergic mechanisms of photothermal and photodynamic therapies mediated by photosensitizer/carbon nanotube complexes. Carbon 2016, 97, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, M.A.; Emami, F.; Sobhani, Z.; Koohi-Hosseinabadi, O.; Dehghanian, A.R.; Zebarjad, S.M.; Moghim, M.H.; Oryan, A.; Sm, Z. Novel Combination of Silver Nanoparticles and Carbon Nanotubes for Plasmonic Photo Thermal Therapy in Melanoma Cancer Model. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 8, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Roche, P.J.; Giannopoulos, P.N.; Mitmaker, E.J.; Tamilia, M.; Paliouras, M.; A Trifiro, M. Prostate-specific membrane antigen–directed nanoparticle targeting for extreme nearfield ablation of prostate cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinabadi, O.K.; Behnam, M.A.; Khoradmehr, A.; Emami, F.; Sobhani, Z.; Dehghanian, A.R.; Firoozabadi, A.D.; Rahmanifar, F.; Vafaei, H.; Tamadon, A.-D.; et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment using plasmonic nanoparticles irradiated by laser in a rat model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrar, A.; Sobhani, Z.; Behnam, M.A. Melanoma Cancer Therapy Using PEGylated Nanoparticles and Semiconductor Laser. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 12, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-P.; Xie, C.-F.; Luo, Y.-S.; Song, F.-T.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhu, J.-H.; Zhang, X.-H. Solubilities of betulin and betulinic acid in sodium hydroxide aqueous solutions of varied mole fraction at temperatures from 283.2K to 323.2K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2013, 67, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, I.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Silva, A.K.; Bianco, A.; Luciani, N.; Gazeau, F. Synergic mechanisms of photothermal and photodynamic therapies mediated by photosensitizer/carbon nanotube complexes. Carbon 2016, 97, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S. Cationic Materials for Gene Therapy: A Look Back to the Birth and Development of 2,2-Bis-(hydroxymethyl)Propanoic Acid-Based Dendrimer Scaffolds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piña, M.J.; Girotti, A.; Serrano, S.; Muñoz, R.; Rodríguez-Cabello, J.C.; Arias, F.J. A double safety lock tumor-specific device for suicide gene therapy in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, B.; Ramirez, A.; Carrillo, E.; Jimenez, G.; Griñán-Lisón, C.; López-Ruiz, E.; Jiménez-Martínez, Y.; Marchal, J.A.; Boulaiz, H. Deciphering the Mechanism of Action Involved in Enhanced Suicide Gene Colon Cancer Cell Killer Effect Mediated by Gef and Apoptin. Cancers 2019, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-C.; Wang, M.; Chou, M.-C.; Chao, C.-N.; Fang, C.-Y.; Chen, P.-L.; Chang, D.; Shen, C.-H. Gene therapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer cells using JC polyomavirus-like particles packaged with a PSA promoter driven-suicide gene. Cancer Gene Ther. 2019, 26, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Hossain, J.; Marchini, A.; Fehse, B.; Bjerkvig, R.; Miletic, H. Suicide gene therapy for the treatment of high-grade glioma: past lessons, present trends, and future prospects. Neuro-Oncology Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-N.; Lin, M.-C.; Fang, C.-Y.; Chen, P.-L.; Chang, D.; Shen, C.-H.; Wang, M. Gene Therapy for Human Lung Adenocarcinoma Using a Suicide Gene Driven by a Lung-Specific Promoter Delivered by JC Virus-Like Particles. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0157865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelsen, S.R.; Christensen, C.L.; Sehested, M.; Cramer, F.; Poulsen, T.T.; Patterson, A.V.; Poulsen, H.S. Single agent- and combination treatment with two targeted suicide gene therapy systems is effective in chemoresistant small cell lung cancer cells. J. Gene Med. 2012, 14, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Sutariya, V.; Gupta, S.V.; Bhatia, D. GADD45α-targeted suicide gene therapy driven by synthetic CArG promoter E9NS sensitizes NSCLC cells to cisplatin, resveratrol, and radiation regardless of p53 status. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, ume 12, 3161–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni-Dargah, M.; Akbari-Birgani, S.; Madadi, Z.; Saghatchi, F.; Kaboudin, B. Carbon Nanotube-Delivered Ic9 Suicide Gene Therapy for Killing Breast Cancer Cells In Vitro. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, W.; Tang, R.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, X. Gene regulation with carbon-based siRNA conjugates for cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 104, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.; Hu, R.; Yang, C.; Yoon, H.S.; Yong, K.-T. Pancreatic cancer gene therapy using an siRNA-functionalized single walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) nanoplex. Biomater. Sci. 2014, 2, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koury, J.; Lucero, M.; Cato, C.; Chang, L.; Geiger, J.; Henry, D.; Hernandez, J.; Hung, F.; Kaur, P.; Teskey, G.; et al. Immunotherapies: Exploiting the Immune System for Cancer Treatment. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Bevan, M.J. CD8+ T Cells: Foot Soldiers of the Immune System. Immunity 2011, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Wang, C.; Cong, L.; Marjanovic, N.D.; Kowalczyk, M.S.; Zhang, H.; Nyman, J.; Sakuishi, K.; Kurtulus, S.; Gennert, D.; et al. A Distinct Gene Module for Dysfunction Uncoupled from Activation in Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells. Cell 2016, 166, 1500–1511.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, L.; Liang, C.; Xiang, J.; Peng, R.; Liu, Z. Immunological Responses Triggered by Photothermal Therapy with Carbon Nanotubes in Combination with Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy to Inhibit Cancer Metastasis. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 8154–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Qi, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Yan, Y.; Gao, M. Application of Carbon Nanomaterials to Enhancing Tumor Immunotherapy: Current Advances and Prospects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, ume 19, 10899–10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ullah, A.; Fan, X.; Xu, Z.; Zong, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, G. Delivery of nanoparticle antigens to antigen-presenting cells: from extracellular specific targeting to intracellular responsive presentation. J. Control. Release 2021, 333, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.-I.; Lee, A.-H.; Shin, H.-Y.; Song, H.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, T.-B.; Lee, S.-R.; Yang, S.-H. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tau, G.; Rothman, P. Biologic Functions of the IFN-γ Receptors. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1999, 54.

- Paul, S.; Lal, G. The Molecular Mechanism of Natural Killer Cells Function and Its Importance in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1124–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, B.; Akhtar, T.; Kousar, R.; Huang, C.-C.; Li, X.-G. Carbon Nanomaterials: Emerging Roles in Immuno-Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Yang, M.; Jia, F.; Kong, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Xing, J.; Xie, S.; Xu, H. Subcutaneous injection of water-soluble multi-walled carbon nanotubes in tumor-bearing mice boosts the host immune activity. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 145104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Gao, S.; Song, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Intratumorally CpG immunotherapy with carbon nanotubes inhibits local tumor growth and liver metastasis by suppressing the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of colon cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2020, 32, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, T.S.; Saxena, R.K. Enhanced antibody response to ovalbumin coupled to poly-dispersed acid functionalized single walled carbon nanotubes. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 217, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ahmed, M.; Khan, A.; Xu, L.; Walters, A.A.; Ballesteros, B.; Al-Jamal, K.T. Tailoring the Architecture of Cationic Polymer Brush-Modified Carbon Nanotubes for Efficient siRNA Delivery in Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 30284–30294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Gong, C.; Gu, F.; Wang, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhang, L.; Qiang, L.; Ding, X.; Gao, S.; Gao, Y. Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Targeting Delivery of Immunostimulatory CpG Oligonucleotides Against Prostate Cancer. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2018, 14, 1613–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Alizadeh, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Farrukh, O.; Manuel, E.; Diamond, D.J.; Badie, B. Carbon Nanotubes Enhance CpG Uptake and Potentiate Antiglioma Immunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzi, M.R.M.; Johari, N.A.; Zawawi, W.F.A.W.M.; Zawawi, N.A.; Latiff, N.A.; Malek, N.A.N.N.; Wahab, A.A.; Salim, M.I.; Jemon, K. In vivo evaluation of oxidized multiwalled-carbon nanotubes-mediated hyperthermia treatment for breast cancer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2022, 134, 112586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.H.; Dao, T.; Ahearn, I.; Fehrenbacher, N.; Casey, E.; Rey, D.A.; Korontsvit, T.; Zakhaleva, V.; Batt, C.A.; Philips, M.R.; et al. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Deliver Peptide Antigen into Dendritic Cells and Enhance IgG Responses to Tumor-Associated Antigens. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5300–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, T.R.; Steenblock, E.R.; Stern, E.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Haller, G.L.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Fahmy, T.M. Enhanced Cellular Activation with Single Walled Carbon Nanotube Bundles Presenting Antibody Stimuli. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 2070–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, T.R.; Look, M.; Staffier, P.A.; Haller, G.L.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Fahmy, T.M. Clustering of Stimuli on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Bundles Enhances Cellular Activation. Langmuir 2009, 26, 5645–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, T.R.; Li, N.; Shah, S.; Look, M.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Haller, G.L.; Justesen, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Fahmy, T.M. Adsorption of Multimeric T Cell Antigens on Carbon Nanotubes: Effect on Protein Structure and Antigen-Specific T Cell Stimulation. Small 2012, 9, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkert, S.C.; He, X.; Shurin, G.V.; Nefedova, Y.; Kagan, V.E.; Shurin, M.R.; Star, A. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotube Cups for Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 5, 13685–13696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ali, S.F.; Dervishi, E.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Casciano, D.; Biris, A.S. Cytotoxicity Effects of Graphene and Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Neural Phaeochromocytoma-Derived PC12 Cells. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3181–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Xiao, Q.; Mei, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, W. Insights on functionalized carbon nanotubes for cancer theranostics. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiyama, S.; Umezawa, M.; Iizumi, Y.; Ube, T.; Okazaki, T.; Kamimura, M.; Soga, K. Delayed Increase in Near-Infrared Fluorescence in Cultured Murine Cancer Cells Labeled with Oxygen-Doped Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Langmuir 2018, 35, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Cheng, L.; Lee, S.-T.; Liu, Z. Noble Metal Coated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Applications in Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering Imaging and Photothermal Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7414–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Chen, C.; Hou, L.; Zhang, H.; Che, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Z. Single-walled carbon nanotube-loaded doxorubicin and Gd-DTPA for targeted drug delivery and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Drug Target. 2016, 25, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, N.; Shen, J. Magnetofluorescent Carbon Quantum Dot Decorated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for Dual-Modal Targeted Imaging in Chemo-Photothermal Synergistic Therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 4, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghatchi, F.; Mohseni-Dargah, M.; Akbari-Birgani, S.; Saghatchi, S.; Kaboudin, B. Cancer Therapy and Imaging Through Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Decorated with Magnetite and Gold Nanoparticles as a Multimodal Tool. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delogu, L.G.; Vidili, G.; Venturelli, E.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Zoroddu, M.A.; Pilo, G.; Nicolussi, P.; Ligios, C.; Bedognetti, D.; Sgarrella, F.; et al. Functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes as ultrasound contrast agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 16612–16617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avti, P.K.; Hu, S.; Favazza, C.; Mikos, A.G.; Jansen, J.A.; Shroyer, K.R.; Wang, L.V.; Sitharaman, B. Detection, Mapping, and Quantification of Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Histological Specimens with Photoacoustic Microscopy. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e35064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Bao, C.; Liang, S.; Fu, H.; Wang, K.; Deng, M.; Liao, Q.; Cui, D. RGD-conjugated silica-coated gold nanorods on the surface of carbon nanotubes for targeted photoacoustic imaging of gastric cancer. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 264–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.T.-W.; Fabbro, C.; Venturelli, E.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Chaloin, O.; Da Ros, T.; Methven, L.; Nunes, A.; Sosabowski, J.K.; Mather, S.J.; et al. The relationship between the diameter of chemically-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes and their organ biodistribution profiles in vivo. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 9517–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chao, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Pan, J.; Guo, W.; Wu, J.; Sheng, M.; Yang, K.; Wang, J.; et al. Polydopamine Coated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as a Versatile Platform with Radionuclide Labeling for Multimodal Tumor Imaging and Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Bagley, A.F.; Na, Y.J.; Birrer, M.J.; Bhatia, S.N.; Belcher, A.M. Deep, noninvasive imaging and surgical guidance of submillimeter tumors using targeted M13-stabilized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13948–13953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsher, K.; Liu, Z.; Sherlock, S.P.; Robinson, J.T.; Chen, Z.; Daranciang, D.; Dai, H. A route to brightly fluorescent carbon nanotubes for near-infrared imaging in mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, I.; Al-Fandi, M.G.; Makableh, Y.; Harahsha, T. Developing a nano-biosensor for early detection of pancreatic cancer. Sens. Rev. 2020, 41, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Hong, S.; Singh, R.; Jang, J. Single-walled carbon nanotube based transparent immunosensor for detection of a prostate cancer biomarker osteopontin. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 869, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tîlmaciu, C.M.; Dinesh, B.; Pellerano, M.; Diot, S.; Guidetti, M.; Vollaire, J.; Bianco, A.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Josserand, V.; Morris, M.C. Nanobiosensor Reports on CDK1 Kinase Activity in Tumor Xenografts in Mice. Small 2021, 17, 2007177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodi, P.; Rezayi, M.; Rasouli, E.; Avan, A.; Gholami, M.; Mobarhan, M.G.; Karimi, E.; Alias, Y. Early-stage cervical cancer diagnosis based on an ultra-sensitive electrochemical DNA nanobiosensor for HPV-18 detection in real samples. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Tabakman, S.; Welsher, K.; Dai, H. Carbon nanotubes in biology and medicine: In vitro and in vivo detection, imaging and drug delivery. Nano Res. 2009, 2, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Young, R.J.; Macpherson, J.V.; Wilson, N.R. Silver-decorated carbon nanotube networks as SERS substrates. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011, 42, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Su, J.; Wu, K.; Ma, W.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Sun, P.; Shen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Fan, Q. Multifunctional Thermosensitive Liposomes Based on Natural Phase-Change Material: Near-Infrared Light-Triggered Drug Release and Multimodal Imaging-Guided Cancer Combination Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 10540–10553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaghada, K.B.; Starosolski, Z.A.; Bhayana, S.; Stupin, I.; Patel, C.V.; Bhavane, R.C.; Gao, H.; Bednov, A.; Yallampalli, C.; Belfort, M.; et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of a nanoparticle-based blood-pool contrast agent for MR imaging of the placenta. Placenta 2017, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanginario, A.; Miccoli, B.; Demarchi, D. Carbon Nanotubes as an Effective Opportunity for Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Biosensors 2017, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Ding, W.; Ye, F.; Lou, C.; Xing, D. Shape-adapting thermoacoustic imaging system based on flexible multi-element transducer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 094104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Zerda, A.; Zavaleta, C.; Keren, S.; Vaithilingam, S.; Bodapati, S.; Liu, Z.; Levi, J.; Smith, B.R.; Ma, T.-J.; Oralkan, O.; et al. Carbon nanotubes as photoacoustic molecular imaging agents in living mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Shi, K.; Pei, P.; Ge, F.; Yang, K.; Liu, T. Versatile labeling of multiple radionuclides onto a nanoscale metal–organic framework for tumor imaging and radioisotope therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2947–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; Massey, C.F.; Pinchuk, A.N.; Bitton, A.N.; Patel, R.; Zhang, R.; Rao, A.V.; Iyer, G.; et al. 177Lu-NM600 Targeted Radionuclide Therapy Extends Survival in Syngeneic Murine Models of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 61, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Peng, R.; Liu, Z. Carbon nanotubes for biomedical imaging: The recent advances. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1951–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, A.K.; Wu, X.; Ferreira, J.S.; Kim, M.; Powell, L.R.; Kwon, H.; Groc, L.; Wang, Y.; Cognet, L. Fluorescent sp3 Defect-Tailored Carbon Nanotubes Enable NIR-II Single Particle Imaging in Live Brain Slices at Ultra-Low Excitation Doses. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalet, X.; Pinaud, F.F.; Bentolila, L.A.; Tsay, J.M.; Doose, S.; Li, J.J.; Sundaresan, G.; Wu, A.M.; Gambhir, S.S.; Weiss, S. Quantum Dots for Live Cells, in Vivo Imaging, and Diagnostics. Science 2005, 307, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silindir-Gunay, M.; Sarcan, E.T.; Ozer, A.Y. Near-infrared imaging of diseases: A nanocarrier approach. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.C., Jr.; Lyons, C. Electrode systems for continuous monitoring in cardiovascular surgery. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1962, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Murthy, C.; Prabha, C.R. Recent advances in carbon nanotube based electrochemical biosensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.; Cha, Y.K.; Kim, S.-O.; Cho, S.; Ko, H.J.; Park, T.H. FET-based nanobiosensors for the detection of smell and taste. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellan, L.M.; Wu, D.; Langer, R.S. Current Trends in Nanobiosensor Technology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoosefian, M.; Etminan, N. Leucine/Pd-loaded (5,5) single-walled carbon nanotube matrix as a novel nanobiosensors for in silico detection of protein. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovics, P.; Awadallah, W.N.; Kohrt, S.E.; Case, T.C.; Miller, N.L.; Ricke, E.A.; Huang, W.; Ramirez-Solano, M.; Liu, Q.; Vezina, C.M.; et al. Prostatic osteopontin expression is associated with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate 2020, 80, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewski, T.; Winiecki, J.; Makarewicz, R.; Zekanowska, E. The effect of radiotherapy and hormone therapy on osteopontin concentrations in prostate cancer patients. 2020, 25, 527–530.

- Hiraoka, D.; Hosoda, E.; Chiba, K.; Kishimoto, T. SGK phosphorylates Cdc25 and Myt1 to trigger cyclin B–Cdk1 activation at the meiotic G2/M transition. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 3597–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Curreli, M.; Lin, H.; Lei, B.; Ishikawa, F.N.; Datar, R.; Cote, R.J.; Thompson, M.; Zhou, C. Complementary Detection of Prostate-Specific Antigen Using In2O3 Nanowires and Carbon Nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12484–12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Munge, B.; Patel, V.; Jensen, G.; Bhirde, A.; Gong, J.D.; Kim, S.N.; Gillespie, J.; Gutkind, J.S.; Papadimitrakopoulos, F.; et al. Carbon Nanotube Amplification Strategies for Highly Sensitive Immunodetection of Cancer Biomarkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11199–11205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S. Multilayers enzyme-coated carbon nanotubes as biolabel for ultrasensitive chemiluminescence immunoassay of cancer biomarker. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 2961–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.; Tang, M.; Chai, R.; He, X. A novel amperometric immunosensor based on layer-by-layer assembly of gold nanoparticles–multi-walled carbon nanotubes-thionine multilayer films on polyelectrolyte surface. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 603, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.; Chen, S.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.; Zhong, X. Layer-by-layer self-assembled multilayer films of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and platinum–Prussian blue hybrid nanoparticles for the fabrication of amperometric immunosensor. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2008, 624, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Jin, X.; Lu, H.; Shen, G.; Yu, R. Poly-l-lysine/hydroxyapatite/carbon nanotube hybrid nanocomposite applied for piezoelectric immunoassay of carbohydrateantigen 19-9. Anal. 2007, 133, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, S.; Roldán, M.; Pérez, S.; Fàbregas, E. Toward a Fast, Easy, and Versatile Immobilization of Biomolecules into Carbon Nanotube/Polysulfone-Based Biosensors for the Detection of hCG Hormone. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 6508–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.; Chen, S.; An, H. Sensitive immunoassay of human chorionic gonadotrophin based on multi-walled carbon nanotube–chitosan matrix. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2008, 31, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.P.; Lee, B.Y.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Sim, S.J. Enhancement of sensitivity and specificity by surface modification of carbon nanotubes in diagnosis of prostate cancer based on carbon nanotube field effect transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 3372–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.; Min, L.; Li, W.; Xu, Y. Electrochemical sensing platform based on tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)cobalt(III) and multiwall carbon nanotubes–Nafion composite for immunoassay of carcinoma antigen-125. Electrochimica Acta 2009, 54, 7242–7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; He, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. Sensitive amperometric immunosensor for α-fetoprotein based on carbon nanotube/gold nanoparticle doped chitosan film. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 384, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Zhang, R.; Dong, C.; Jiang, T.; Tian, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yi, W.; Hou, J. A simple MWCNTs@paper biosensor for CA19-9 detection and its long-term preservation by vacuum freeze drying. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Yang, L.; Deng, S.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xie, M. Development of nanosensor by bioorthogonal reaction for multi-detection of the biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2021, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Yin, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M. Tetrahedral DNA nanostructure based biosensor for high-performance detection of circulating tumor DNA using all-carbon nanotube transistor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 197, 113785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Lan, Q.; Xie, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Label-Free Electrochemical Immunosensor for Ultrasensitive Detection of Carbohydrate Antigen 125 Based on Antibody-Immobilized Biocompatible MOF-808/CNT. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 3295–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil Song, C.; Oh, E.; Kang, M.S.; Shin, B.S.; Han, S.Y.; Jung, M.; Lee, E.S.; Yoon, S.-Y.; Sung, M.M.; Ng, W.B.; et al. Fluorescence-based immunosensor using three-dimensional CNT network structure for sensitive and reproducible detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma biomarker. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1027, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Dan, W.; Fu, Y.; Liu, S. Construction of carbon nanotube based nanoarchitectures for selective impedimetric detection of cancer cells in whole blood. Anal. 2014, 139, 5086–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Li, Y.; Tjong, S.C. Graphene Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Biocompatibility, and Cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasena, T.; Francis, A.P.; Ramaprabhu, S. Toxicity of Graphene: An Update. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; 2021; Vol. 259.

- Zhao, C.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Ye, L.; Wang, N.; Wang, F.; Li, L.; Mohammadniaei, M.; Zhang, M.; et al. Synthesis of graphene quantum dots and their applications in drug delivery. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Kollie, L.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Ying, X.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; Yu, M. Antitumor Activity and Potential Mechanism of Novel Fullerene Derivative Nanoparticles. Molecules 2021, 26, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, N.; Audira, G.; Castillo, A.L.; Siregar, P.; Ruallo, J.M.S.; Roldan, M.J.; Chen, J.-R.; Lee, J.-S.; Ger, T.-R.; Hsiao, C.-D. An Update Report on the Biosafety and Potential Toxicity of Fullerene-Based Nanomaterials toward Aquatic Animals. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Ma, Q. Advances in mechanisms and signaling pathways of carbon nanotube toxicity. Nanotoxicology 2014, 9, 658–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qin, X.; Zeng, G. Biodegradation of Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene, and Their Derivatives. Trends Biotechnol 2017, 35, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Xu, K. Clinical application of carbon nanoparticles in lymphatic mapping during colorectal cancer surgeries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; Gu, J. The application of carbon nanoparticles in the lymph node biopsy of cN0 papillary thyroid carcinoma: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Asian J. Surg. 2017, 40, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ao, S.; Bu, Z.; Wu, A.; Wu, X.; Shan, F.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, Z.; Ji, J. Clinical study of harvesting lymph nodes with carbon nanoparticles in advanced gastric cancer: a prospective randomized trial. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Tucker, A.; Gidcumb, E.; Shan, J.; Yang, G.; Calderon-Colon, X.; Sultana, S.; Lu, J.; Zhou, O.; Spronk, D.; et al. High resolution stationary digital breast tomosynthesis using distributed carbon nanotube x-ray source array. Med Phys. 2012, 39, 2090–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amal, H.; Leja, M.; Funka, K.; Skapars, R.; Sivins, A.; Ancans, G.; Liepniece-Karele, I.; Kikuste, I.; Lasina, I.; Haick, H. Detection of precancerous gastric lesions and gastric cancer through exhaled breath. Gut 2015, 65, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-Q.; Broza, Y.Y.; Ionsecu, R.; Tisch, U.; Ding, L.; Liu, H.; Song, Q.; Pan, Y.-Y.; Xiong, F.-X.; Gu, K.-S.; et al. A nanomaterial-based breath test for distinguishing gastric cancer from benign gastric conditions. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittar, R.; Alves, N.G.P.; Bertoldo, C.; Brugnera, C.; Oiticica, J. Efficacy of Carbon Microcoils in Relieving Cervicogenic Dizziness. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 21, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CNTs | Measures | Cell Line/Animal Models | Drug(s) | Concentration/Dose | Results | Refs |

| MWCNTs | L = 110–980 nm | H1299 | MTX | 7.72×10−5 -1.51×10−3 mg/mL | pH dependant selective delivery of MTX to H1299 Low damage to healthy MRC-5 |

[41] |

| MWCNTs | L = 330 nmØ = 30 nm | BM-MSCs, MDA-MB-231 CD44high, CD24low CSCs | Pt-NPs, PBI | 100 µM | Cause cell cycle arrest, diminish drug resistance Impede DNA repair in breast CSCs. |

[49] |

| CNTs | N.R. | Kunming mice | Span, PEG, FA Paclitaxel | 350 mg/kg | Penetrate breast tumours Inhibited development, induced tumour cells death |

[50] |

| SWCNTs | N.R. | HT-29 | Porphyrin, PEG | 25 mg/mL | No antitumour activity | [54] |

| MWCNTs | Ø = 17.1±3.0 nm | C540 Male Balb/c mice | Poly pyrrole | 250 mg/mL, 10 mg/kg | Concentration-dependent cytotoxicity under multi-step ultrasonic irradiation (8.9% cell viability for 250 mg/mL) 75% Necrosis and 50% TVR after 10 days of SDT |

[51] |

| MWCNTs | Ø = 10 nmL = 5–15 µm | Male Balb/c mice | CREKA | MWNTs-PEG 2 mg/kg CMWNTs-PEG 4 mg/kg |

6.4 Times ⬆ accumulation in tumour tissue Xenograft eradicated after 4 cycles of illumination |

[52] |

| MWCNTs | Ø = 5–20 nmL = 1–10 µm | HepG2, HeLa cells C57BL/6J female mice |

PEG-O-CNTs | 0–1000 mL 1 mg/mL injected in tumour at 200 µL/cm3 |

⬆Cell toxicity of PEG-O-CNTs, O-CNTs, pure CNTs Continuous-wave NIR laser diode (808 nm) for 10 min ⬆TVR in animal group (PEG-O-CNTs) |

[53] |

| CNTs | Functionalizing molecules | Effectiveness | Tumor model | Biocompatibility test | Refs. |

| SWNTs | PEG | ⬆Solubility, prevent particle aggregation, ⬇side effects | Gastric cancer | ⬇Toxicity towards normal tissue | [61] |

| SWNTs/MWNTs | PEI | ⬆Solubility, homogeneity, dispersity, ⬇particle size ⬆Positive charge to interact with siRNA |

Cervical cancer | N/A | [62] |

| SWNTs | HA | ⬆Stability in serum, overcome MDR Target CD44-overexpressing cancer cells |