Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms of Photodetection in 2D Materials

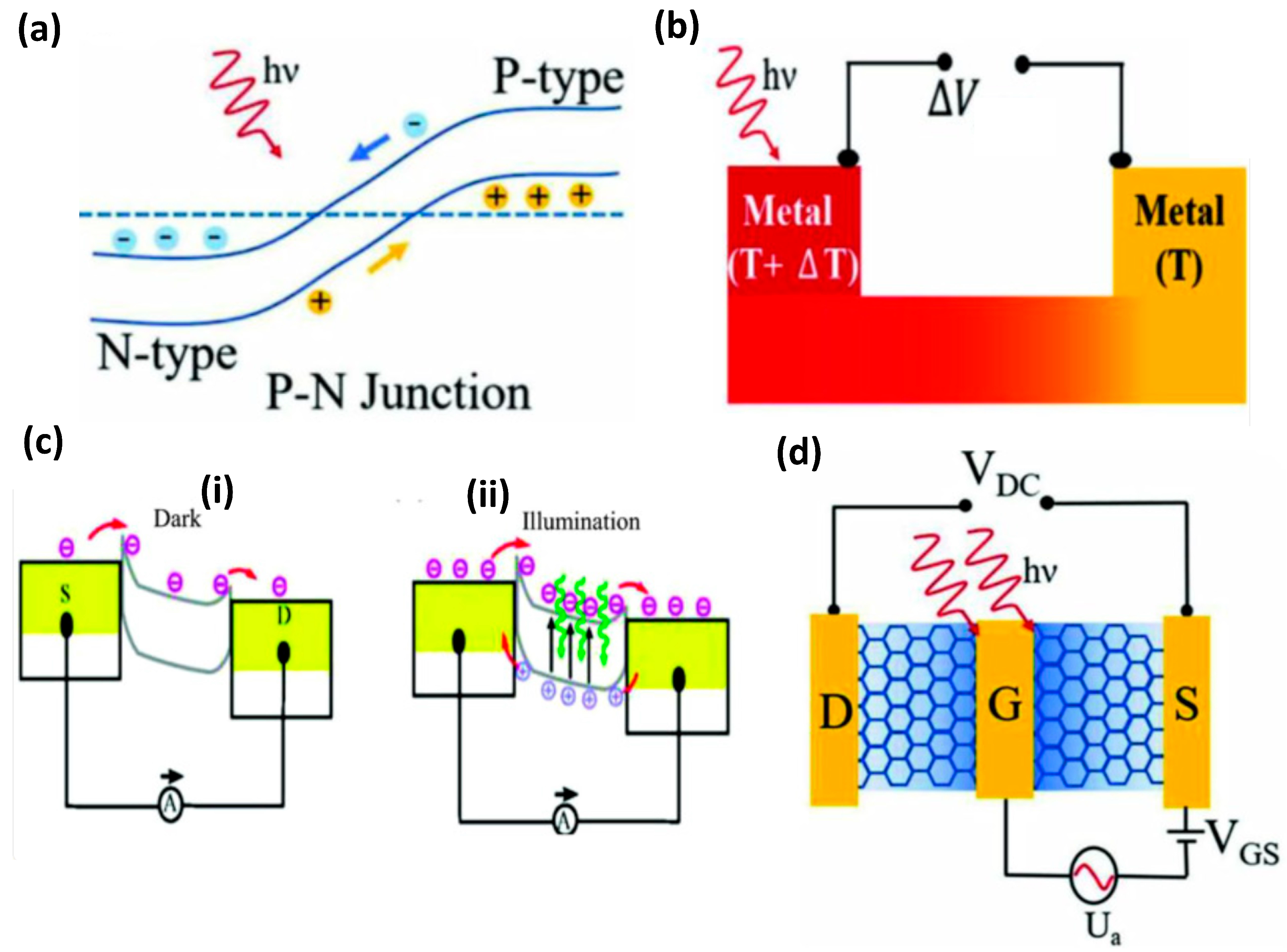

2.1. Photovoltaic Effect

2.2. Photothermoelectric Effect

2.3. Photoconductive Mechanism

2.4. Bolometric Effect

2.5. Carrier generation and trapping effects

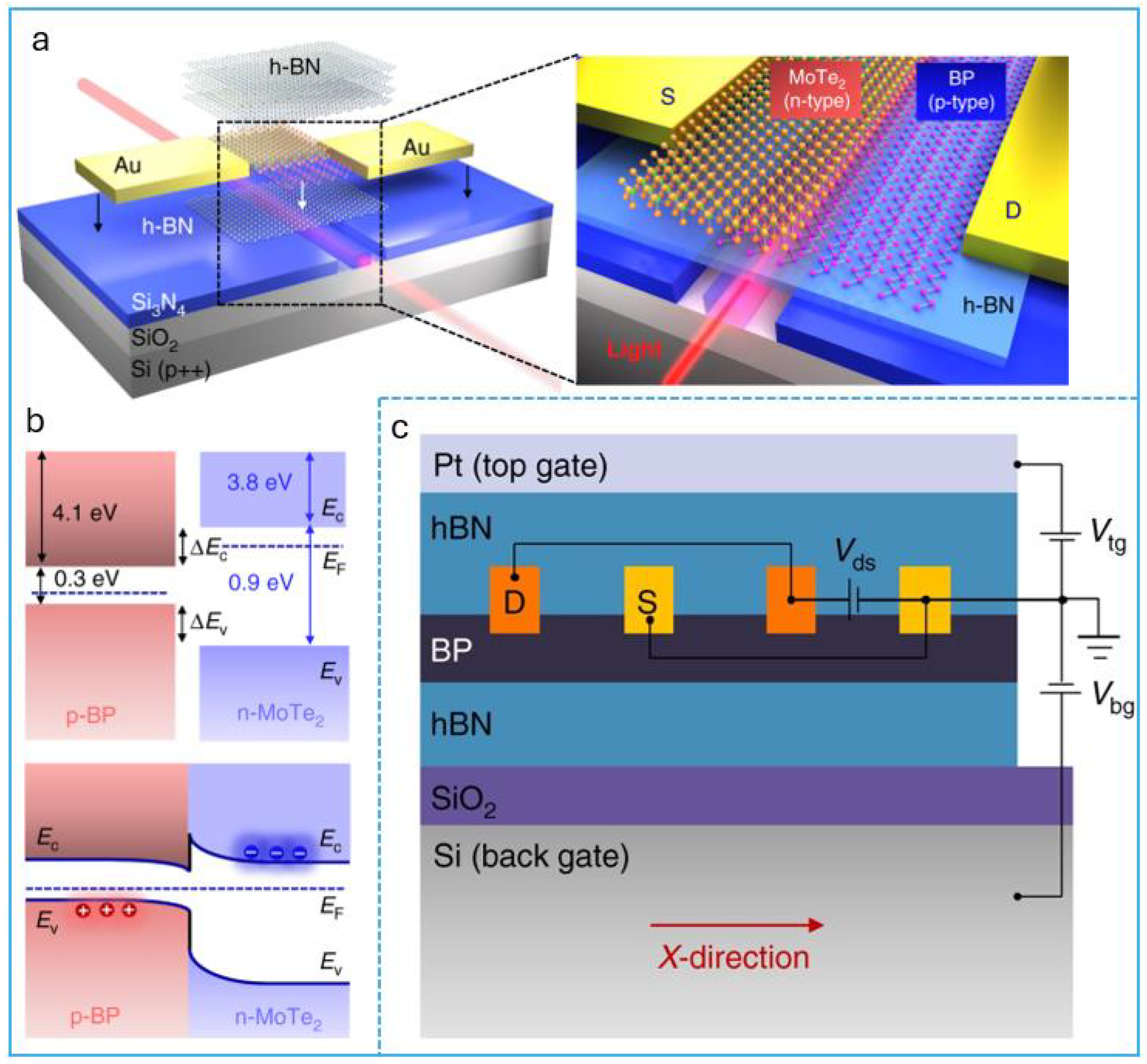

2.6. Built-in electric field in heterostructures

2.7. Plasmon-Enhanced 2D hetrostrucutres

3. 2D Materials for Photodetection

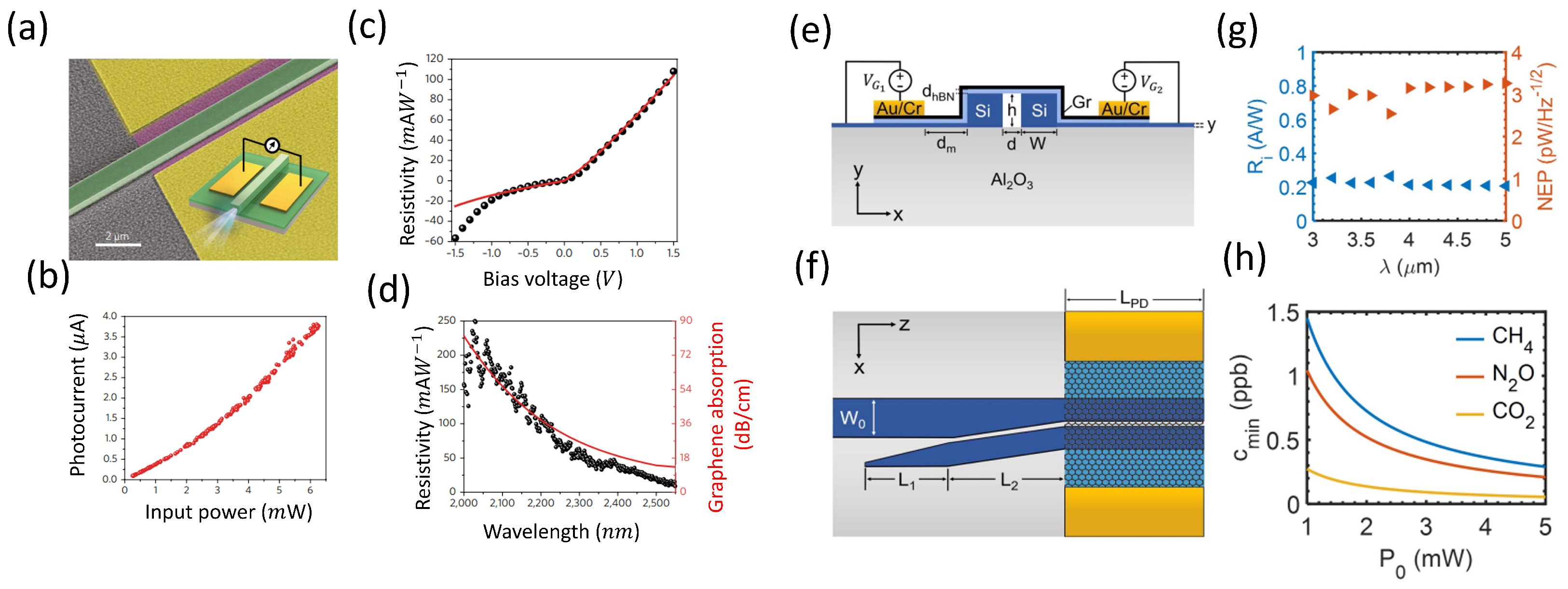

3.1. Graphene-Based Photodetectors

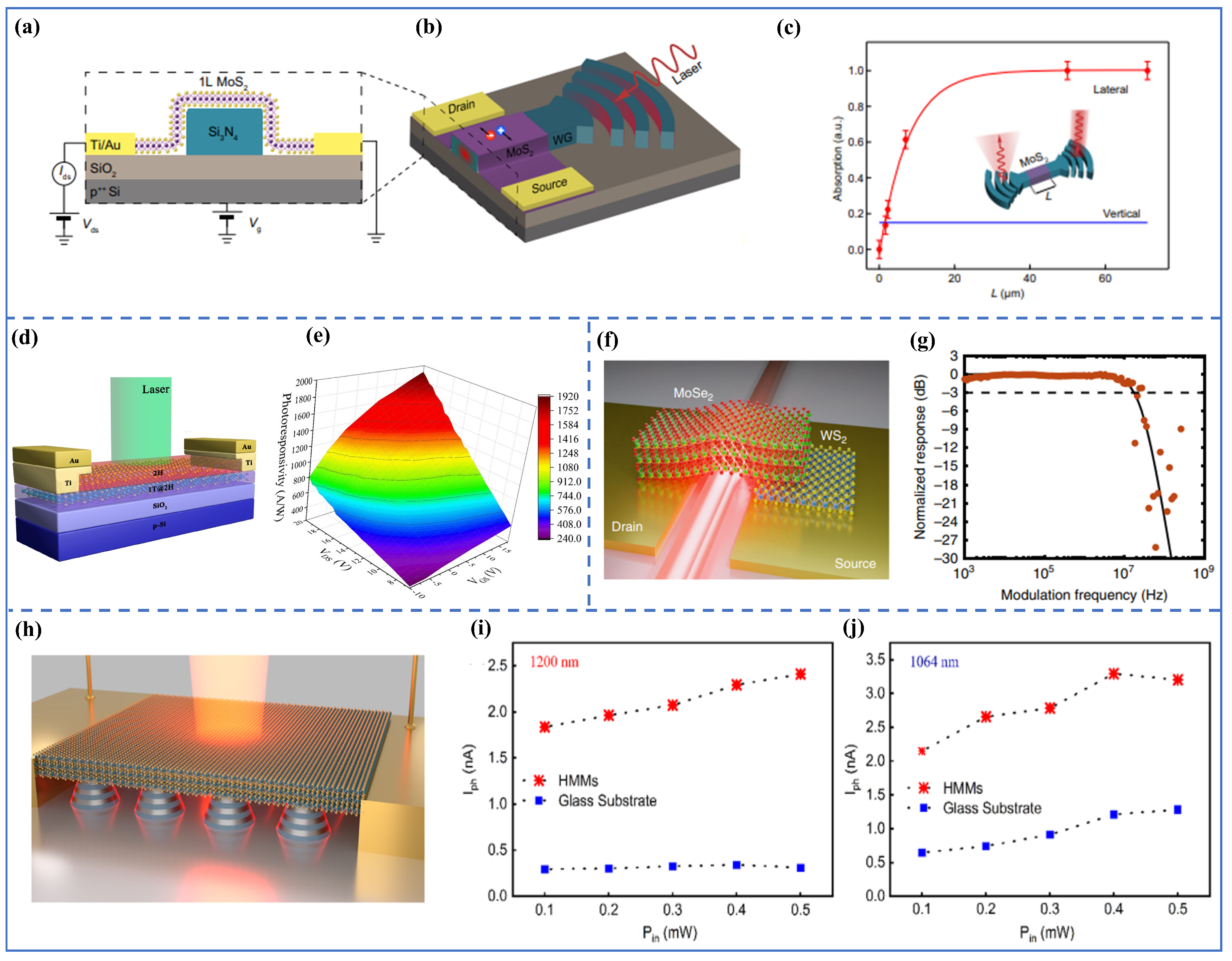

3.2. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides Photodetectors

3.3. Black Phosphorus (BP) Photodetectors

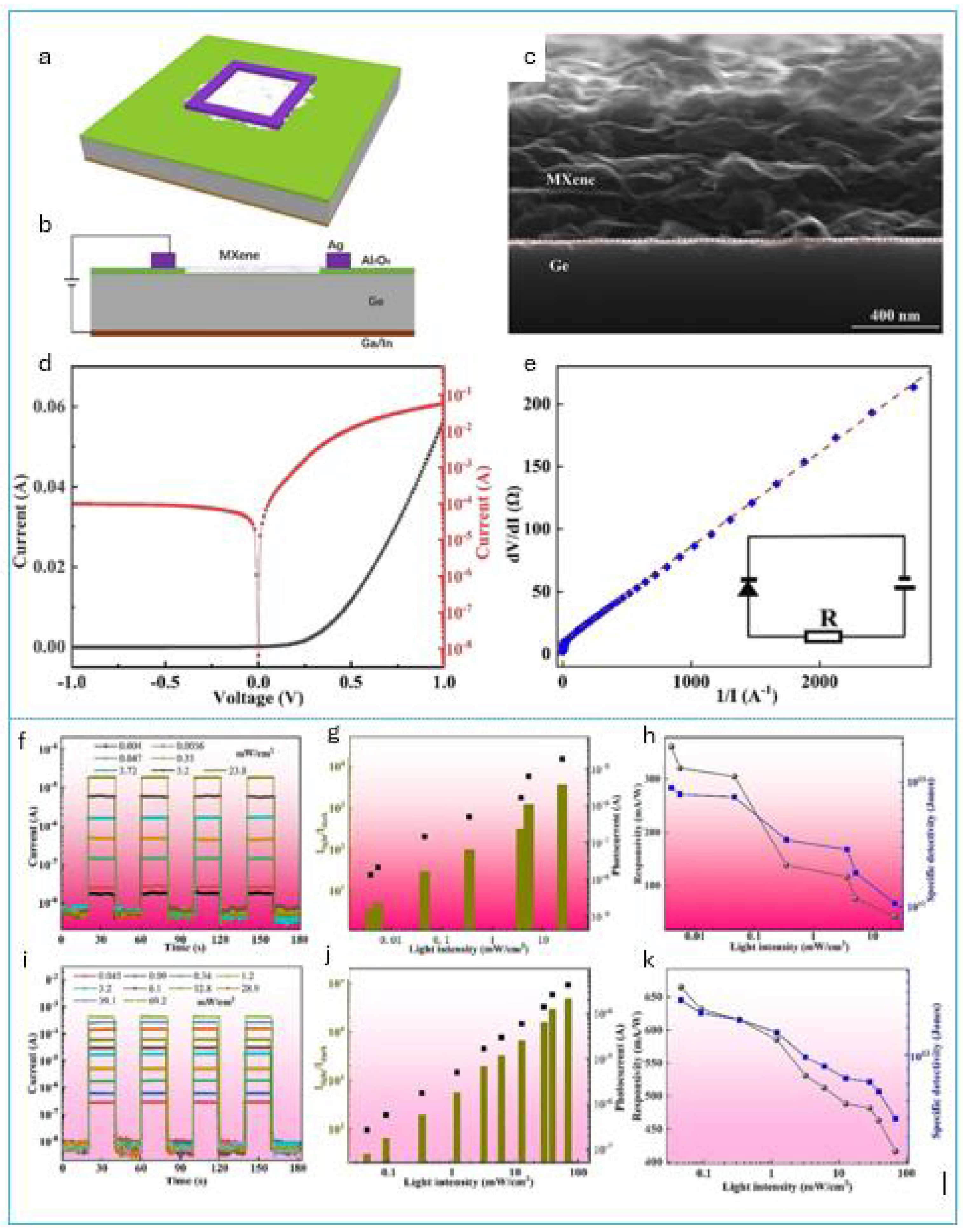

3.4. MXenes Photodetectors

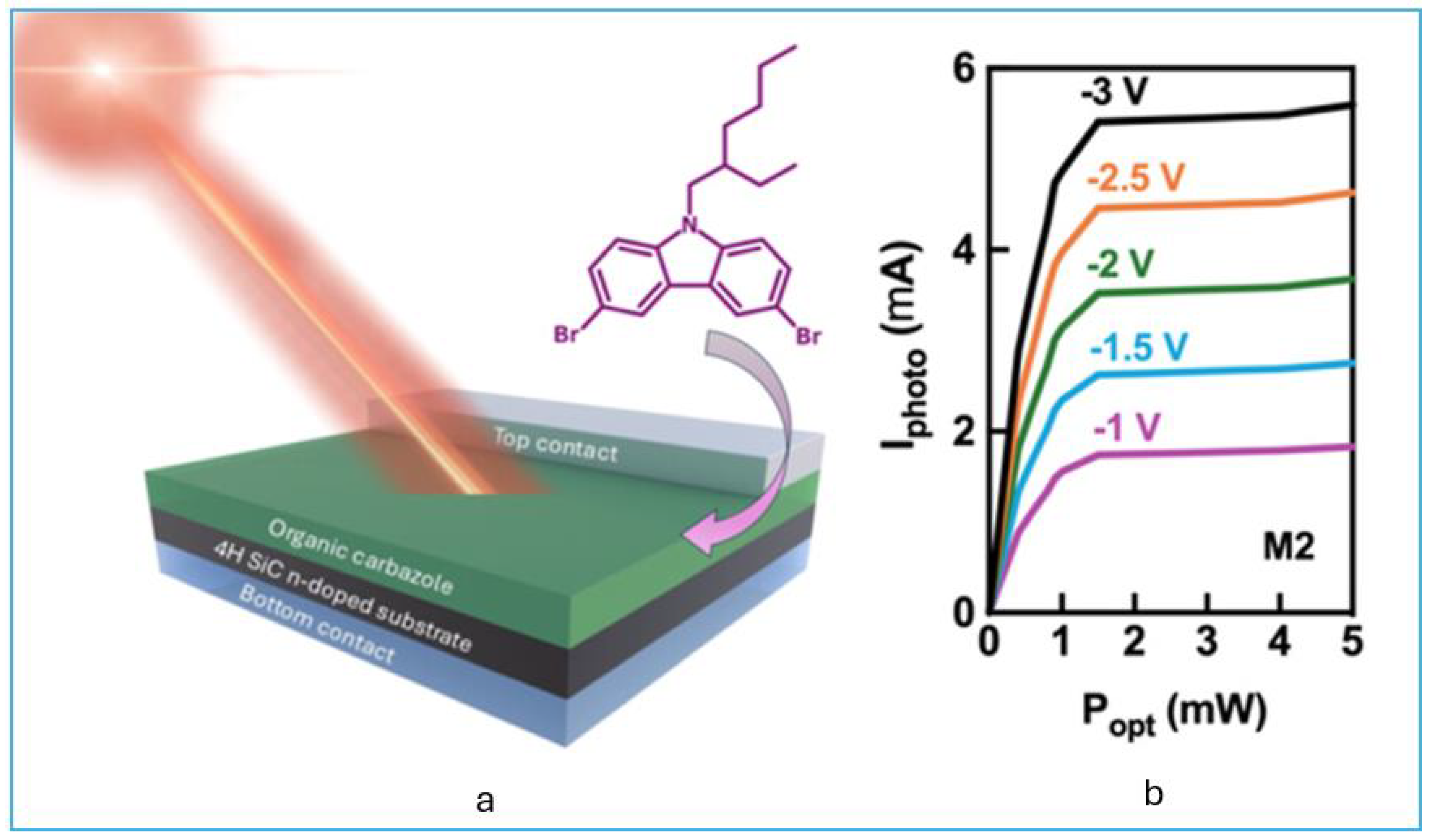

3.5. Carbide Photodetectors

3.6. Bismuth Chalcogenide Photodetectors

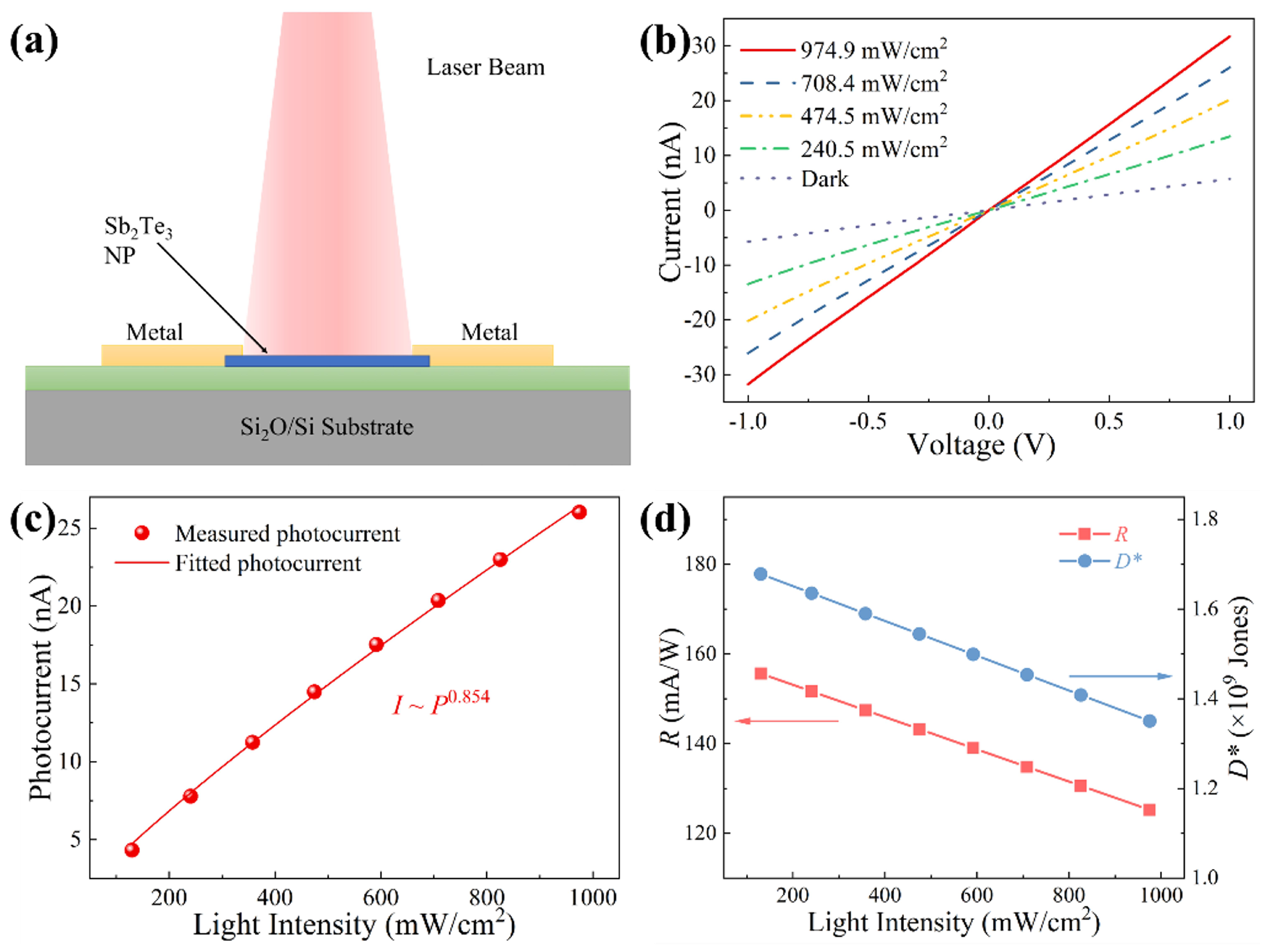

3.7. Antimony Chalcogenide Photodetectors

3.8. Tin Chalcogenide Photodetectors

4. Performance Metrics of different 2D based Photodetectors

5. Applications of 2D Photodetectors

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

- Material Synthesis and Scalability: High-quality and uniform synthesis of 2D materials over large areas remains a critical barrier. Techniques such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and liquid-phase exfoliation often face limitations in layer control, reproducibility, and interfacial purity, which can compromise device performance.

- Interfacial Engineering: The presence of defects, trap states, and uncontrolled band alignments at heterointerfaces can hinder carrier mobility and lead to increased recombination losses. Advanced interface passivation strategies and precision heterojunction design are needed to enhance charge transport.

- Stability and Environmental Sensitivity: Many 2D materials, including MXenes and chalcogenides, are susceptible to oxidation, moisture degradation, and structural deterioration over time. Encapsulation techniques and material functionalization are necessary to improve environmental robustness.

- Trade-offs Between Speed and Responsivity: Achieving a balance between high responsivity and ultrafast response time remains a design challenge, particularly for applications requiring real-time signal processing or imaging.

- Integration and Circuit Compatibility: Seamless integration of 2D photodetectors with existing CMOS technology and flexible electronics platforms is essential for commercial adoption. This necessitates innovations in contact engineering, packaging, and interface compatibility.

- The development of high-entropy MXenes and functionalized chalcogenide derivatives offers new pathways for enhancing photoresponse tunability and spectral coverage.

- Incorporating machine learning and inverse design frameworks could accelerate material discovery and device optimization.

- Emphasis on flexible and wearable device applications will drive the need for stretchable substrates.

- Finally, a shift toward multi-functional devices—such as those combining photodetection with memory or logic functionalities—could enable more compact and energy-efficient optoelectronic systems.

7. Conclusion

Supplementary information

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| List of Acronyms | |

| Acronym | Meaning |

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| A/W | Ampere per Watt |

| APTES | Aminopropyltriethoxysilane |

| APS | Active Pixel Sensor |

| BP | Black Phosphorus |

| CMOS | Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor |

| CVD | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| dB | Decibel |

| DLP | Dember-Like Photocurrent |

| ECM | Electrochemical Metallization |

| FET | Field-Effect Transistor |

| FIR | Far-Infrared |

| GHz | Gigahertz |

| HMM | Hyperbolic Metamaterial |

| III–V | Group III–V Compound Semiconductors |

| InGaAs | Indium Gallium Arsenide |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IR | Infrared |

| Jones | Unit of Specific Detectivity |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| MeV | Milli Electron Volt |

| MHz | Megahertz |

| MIR | Mid-Infrared |

| MoS2 | Molybdenum Disulfide |

| MoSe2 | Molybdenum Diselenide |

| MoTe2 | Molybdenum Ditelluride |

| MWIR | Mid-Wave Infrared |

| MXene | Transition Metal Carbide/Nitride |

| NEP | Noise Equivalent Power |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| OTS | Octadecyltrichlorosilane |

| PD | Photodetector |

| pJ | Picojoule |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| QE | Quantum Efficiency |

| RGO | Reduced Graphene Oxide |

| SAM | Self-Assembled Monolayer |

| Si | Silicon |

| SiN | Silicon Nitride |

| SnS | Tin Sulfide |

| SnSe | Tin Selenide |

| SnTe | Tin Telluride |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SWIR | Short-Wave Infrared |

| Te | Tellurium |

| TMDC | Transition Metal Dichalcogenide |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VCM | Valence Change Memory |

| vdW | van der Waals |

| WSe2 | Tungsten Diselenide |

| WS2 | Tungsten Disulfide |

References

- Li, D.; Lan, C.; Manikandan, A.; Yip, S.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, X.; Shu, L.; Chueh, Y.L.; Han, N.; Ho, J.C. Ultra-fast photodetectors based on high-mobility indium gallium antimonide nanowires. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1664. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Choi, J.R.; Pham, P.V. 2D Materials for Efficient Photodetection: Overview, Mechanisms, Performance and UV-IR Range Applications. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10, 905404. [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, M.; Alani, I.; As’ham, K.; Khurgin, J.; Hattori, H.; Miroshnichenko, A. Mid-Wave Infrared Graphene Photodetectors With High Responsivity for On-Chip Gas Sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.; Mishchenko, O.A.; Carvalho, A.; Neto, A.C. 2D Materials and van der Waals Heterostructures. Science 2016, 353. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; et al. Waveguide-Integrated Black Phosphorus Photodetector for Mid-Infrared Applications. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 913–921. [CrossRef]

- Abate, Y.; et al. Recent Progress on Stability and Passivation of Black Phosphorus. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1704749. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; et al. High-Performance Silicon–Graphene Hybrid Plasmonic Waveguide Photodetectors Beyond 1.55 μm. Light: Science & Applications 2020, 9, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Odebowale, A.; Abdulghani, A.; Berhe, A.; Somaweera, D.; Akter, S.; Abdo, S.; As’ham, K.; Saadabad, R.; Tran, T.; Bishop, D.; et al. Emerging Low Detection Limit of Optically Activated Gas Sensors Based on 2D and Hybrid Nanostructures. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1521. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Chakravarty, S.; Chung, C.J.; Xu, X.; Chen, R.T. Midinfrared Silicon Photonic Waveguides and Devices. Photonics Research 2018, 6, 254–276. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Shim, J.; Kwon, K.; You, J.B.; Choi, K.; Yu, K. Hybrid Integration of III–V Semiconductor Lasers on Silicon Waveguides Using Optofluidic Microbubble Manipulation. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Koppens, F.; Mueller, T.; Avouris, P.; et al. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nature Nanotechnology 2014, 9, 780–793. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, Q.; Bi, C.; et al. Giant Switchable Photovoltaic Effect in Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Devices. Nature Materials 2015, 14, 193–198. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Huang, Z. Photodetectors of 2D Materials From Ultraviolet to Terahertz Waves. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2008126. [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Wang, P.; Fang, H.; Hu, W. Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities for 2D Material-Based Photodetectors. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29, 1803807. [CrossRef]

- Frisenda, R.; Molina-Mendoza, A.J.; Mueller, T.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Van Der Zant, H.S.J. Atomically Thin P-N Junctions Based on Two-Dimensional Materials. Chemical Society Reviews 2018, 47, 3339–3358. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, Z.; Yeow, J.T.W. Two-Dimensional Materials Applied for Room-Temperature Thermoelectric Photodetectors. Materials Research Express 2020, 7, 112001. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.R. Thermocouple: Facts and Theories. Himalayan Physics 2017, 6, 10–14. [CrossRef]

- Kasirga, T.S. Thermal Conductivity Measurements in Atomically Thin Materials and Devices; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 29–50. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, Y.; Bao, X.; Sun, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y. High-Performance Infrared Self-Powered Photodetector Based on 2D Van der Waals Heterostructures. Advanced Functional Materials 2025, p. 2421525. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, R.; Liao, L.; Zhou, H.; Bai, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Plasmon resonance enhanced multicolour photodetection by graphene. Nature communications 2011, 2, 579.

- Tong, J.; Muthee, M.; Chen, S.Y.; Yngvesson, S.K.; Yan, J. Antenna Enhanced Graphene THz Emitter and Detector. Nano Letters 2015, 15, 5295–5301. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, K.; Tsang, H.K.; Shu, C. Graphene on Silicon-on-Sapphire Waveguide Photodetectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of CLEO: Science and Innovations. Optical Society of America, 2015, pp. 2224–2225.

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Xu, K.; Tsang, H.K.; Xu, J.B. High-Responsivity Graphene/Silicon-Heterostructure Waveguide Photodetectors. Nature Photonics 2013, 7, 888–891. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Wu, Y.; Penades, J.S.; Khokhar, A.Z.; Cao, W.; Osman, A.M.; Qi, Y.; Aspiotis, N.K.; Morgan, K.A.; et al. Waveguide Integrated Graphene Mid-Infrared Photodetector. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SPIE, Feb 2018, Vol. 10537, p. 105371N. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.; Lin, H.; Deckoff-Jones, S.; Hempel, M.; Lu, A.Y.; Richardson, K.A.; Palacios, T.; Kong, J.; Hu, J.; Englund, D. Waveguide-Integrated Mid-Infrared Photodetection Using Graphene on a Scalable Chalcogenide Glass Platform, 2021, [2112.14857].

- Ma, Y.; Chang, Y.; Dong, B.; Wei, J.; Liu, W.; Lee, C. Heterogeneously Integrated Graphene/Silicon/Halide Waveguide Photodetectors Toward Chip-Scale Zero-Bias Long-Wave Infrared Spectroscopic Sensing. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 10084–10094. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Song, Y.; Huang, Y.; Kita, D.; Deckoff-Jones, S.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Luo, Z.; et al. Chalcogenide Glass-on-Graphene Photonics. Nature Photonics 2017, 11, 798–805. [CrossRef]

- Urich, A.; Unterrainer, K.; Mueller, T. Intrinsic response time of graphene photodetectors. Nano Letters 2011, 11, 2804–2808. [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.W.; Shi, S.F.; Ralph, D.C.; Park, J.; McEuen, P.L. Photocurrent measurements of supercollision cooling in graphene. Nature Physics 2013, 9, 103–108. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Jang, C.; Adam, S.; Fuhrer, M.S.; Williams, E.D.; Ishigami, M. Charged-impurity scattering in graphene. Nature Physics 2008, 4, 377–381. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Xu, K.; Tsang, H.K.; Xu, J.B. High-responsivity graphene/silicon-heterostructure waveguide photodetectors. Nature Photonics 2013, 7, 888–891. [CrossRef]

- Shiue, R.J.; Gao, Y.; Tan, C.; Peng, C.; Robertson, A.D.; Efetov, D.K.; Walker, D.; Moodera, J.S.; Kong, J.; Englund, D. High-responsivity graphene–boron nitride photodetector and autocorrelator in a silicon photonic integrated circuit. Nano Letters 2015, 15, 7288–7293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chu, H.S.; Ang, K.W. High-responsivity graphene-on-silicon slot waveguide photodetectors. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 13206–13211. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sanchez, O.; Lembke, D.; Kayci, M.; Radenovic, A.; Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nature Nanotechnology 2013, 8, 497–501. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nature nanotechnology 2012, 7, 699–712.

- Marin, J.G.; Unuchek, D.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Kis, A. MoS2 photodetectors integrated with photonic circuits. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2019, 3, 14.

- Wang, W.; Zeng, X.; Warner, J.H.; Guo, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, J.; Jin, W.; Wang, S.; Lu, J.; et al. Photoresponse-bias modulation of a high-performance MoS2 photodetector with a unique vertically stacked 2H-MoS2/1T@ 2H-MoS2 structure. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 33325–33335.

- Gherabli, R.; Indukuri, S.; Zektzer, R.; Frydendahl, C.; Levy, U. MoSe2/WS2 heterojunction photodiode integrated with a silicon nitride waveguide for near infrared light detection with high responsivity. Light: Science & Applications 2023, 12, 60.

- Singla, S.; Frydendahl, C.; Joshi, P.; Mazurski, N.; Indukuri, S.C.; Chakraborty, B.; Levy, U. Enhancing Broad Band Photoresponse of 2D Transition-Metal Dichalcogenide Materials Integrated with Hyperbolic Metamaterial Nanocavities. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 4398–4406.

- Kang, D.H.; Kim, M.S.; Shim, J.; Jeon, J.; Park, H.Y.; Jung, W.S.; Yu, H.Y.; Pang, C.H.; Lee, S.; Park, J.H. High-performance transition metal dichalcogenide photodetectors enhanced by self-assembled monolayer doping. Advanced Functional Materials 2015, 25, 4219–4227.

- Malik, M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Choi, J.R.; Pham, P.V. 2D materials for efficient photodetection: overview, mechanisms, performance and UV-IR range applications. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10, 905404.

- Li, C.; Tian, R.; Chen, X.; Gu, L.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, R.; Li, Z.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; et al. Waveguide-integrated MoTe2 p–i–n homojunction photodetector. ACS nano 2022, 16, 20946–20955.

- Nan, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Ostrikov, K.K.; Ni, Z.; Gu, X.; Xiao, S. Effect of the surface oxide layer on the stability of black phosphorus. Applied Surface Science 2021, 537, 147850.

- Dodda, A.; Jayachandran, D.; Pannone, A.; Trainor, N.; Stepanoff, S.P.; Steves, M.A.; Radhakrishnan, S.S.; Bachu, S.; Ordonez, C.W.; Shallenberger, J.R.; et al. Active pixel sensor matrix based on monolayer MoS2 phototransistor array. Nature Materials 2022, 21, 1379–1387.

- Hong, S.; Zagni, N.; Choo, S.; Liu, N.; Baek, S.; Bala, A.; Yoo, H.; Kang, B.H.; Kim, H.J.; Yun, H.J.; et al. Highly sensitive active pixel image sensor array driven by large-area bilayer MoS2 transistor circuitry. Nature communications 2021, 12, 3559.

- Park, Y.; Ryu, B.; Ki, S.J.; McCracken, B.; Pennington, A.; Ward, K.R.; Liang, X.; Kurabayashi, K. Few-layer MoS2 photodetector arrays for ultrasensitive on-chip enzymatic colorimetric analysis. Acs Nano 2021, 15, 7722–7734.

- Berhe, A.M.; As’ham, K.; Al-Ani, I.; Hattori, H.T.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. Strong coupling and catenary field enhancement in the hybrid plasmonic metamaterial cavity and TMDC monolayers. Opto-Electronic Advances 2024, 7, 230181–1.

- Berhe, A.M.; Odebowale, A.; As’Ham, K.; Hattori, H.T.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. Large Rabi splitting and Purcell factor in coupled Ag metamaterial cavity and MoS2 monolayer. In Proceedings of the 2024 24th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–4.

- Miao, J.; Wang, C. Avalanche photodetectors based on two-dimensional layered materials. Nano Research 2021, 14, 1878–1888.

- Song, J.; Liang, Y.; Ding, F.; Ke, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Lai, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. Te2-Regulated Black Arsenic Phosphorus Monocrystalline Film with Excellent Uniformity for High Performance Photodetection. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2025, 16, 826–834.

- Wan, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Chen, E.; Chen, K.; Wang, S.; Shao, F.; Gu, X.; et al. Large-Area Black Phosphorus by Chemical Vapor Transport for Vertical and Lateral Memristor Devices. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2024, 129, 526–534.

- Zhang, H.; Shan, C.; Wu, K.; Pang, M.; Kong, Z.; Ye, J.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Wang, Z.; Pak, Y.L.; et al. Modification Strategies and Prospects for Enhancing the Stability of Black Phosphorus. ChemPlusChem 2025, p. e202400552.

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, G.; Feng, Q. Solution-Processable Large-Area Black Phosphorus/Reduced Graphene Oxide Schottky Junction for High-Temperature Broadband Photodetectors. Small 2024, 20, 2401289.

- Shen, Y.; Hou, P. An asymmetric Schottky black phosphorus transistor for enhanced broadband photodetection and neuromorphic synaptic functionality. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 125.

- Chen, S.; Liang, Z.; Miao, J.; Yu, X.L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Long, G.; et al. Infrared optoelectronics in twisted black phosphorus. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 8834.

- Hu, R.; Chen, W.; Lai, J.; Li, F.; Qiao, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Qi, X. Heterogeneous Interface Engineering of 2D Black Phosphorus-Based Materials for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Small 2025, 21, 2409735.

- Lien, M.R.; Wang, N.; Guadagnini, S.; Wu, J.; Soibel, A.; Gunapala, S.D.; Wang, H.; Povinelli, M.L. Black Phosphorus Molybdenum Disulfide Midwave Infrared Photodiodes with Broadband Absorption-Increasing Metasurfaces. Nano Letters 2023, 23, 9980–9987.

- Hao, Y.; Hang, T.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Yu, C.; Wu, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Anisotropic Coupling-Based 2D Material Dember Polarized Photodetectors. Advanced Functional Materials 2025, 35, 2416475.

- Li, Q.; Fang, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhou, W.; Ren, D.; Sun, X.; Lu, J. Photodetector Based on Elemental Ferroelectric Black Phosphorus-like Bismuth. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 63786–63794.

- Ogawa, S.; Fukushima, S.; Shimatani, M.; Iwakawa, M. Graphene/black phosphorus-based infrared metasurface absorbers with van der Waals Schottky junctions. Journal of Applied Physics 2024, 136.

- Wang, S.; Chapman, R.J.; Johnson, B.C.; Krasnokutska, I.; Tambasco, J.L.J.; Messalea, K.; Peruzzo, A.; Bullock, J. Integration of black phosphorus photoconductors with lithium niobate on insulator photonics. Advanced Optical Materials 2023, 11, 2201688.

- Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Wang, N.; Hao, R.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Large-area black phosphorus/PtSe2 Schottky junction for high operating temperature broadband photodetectors. Small 2023, 19, 2206590.

- Higashitarumizu, N.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Kim, H.; Bullock, J.; Javey, A. Black Phosphorus for Mid-Infrared Optoelectronics: Photophysics, Scalable Processing, and Device Applications. Nano letters 2024, 24, 13107–13117.

- Zhu, X.; Cai, Z.; Wu, Q.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Q. 2D Black Phosphorus Infrared Photodetectors. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2025, 19, 2400703.

- Tian, R.; Gan, X.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Hu, S.; Gu, L.; Van Thourhout, D.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, J. Chip-integrated van der Waals PN heterojunction photodetector with low dark current and high responsivity. Light: Science & Applications 2022, 11, 101.

- Chen, X.; Lu, X.; Deng, B.; Sinai, O.; Shao, Y.; Li, C.; Yuan, S.; Tran, V.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. Widely tunable black phosphorus mid-infrared photodetector. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1672.

- Zhou, S.; Jiang, C.; Han, J.; Mu, Y.; Gong, J.R.; Zhang, J. High-Performance Self-Powered PEC Photodetectors Based on 2D BiVO4/MXene Schottky Junction. Advanced Functional Materials 2025, 35, 2416922.

- Ding, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Sang, Y.; Cui, M.; Li, W.; Yan, Y.; Tao, T.; Xu, W.; Ren, F.; et al. Self-powered MXene/GaN van der Waals Schottky ultraviolet photodetectors with exceptional responsivity and stability. Applied Physics Reviews 2024, 11.

- Rhyu, H.; Shin, J.H.; Kang, M.H.; Song, W.; Lee, S.S.; Lim, J.; Myung, S. Rapid and Scalable Synthesis of In2O3-Decorated MXene Nanosheets for High-Performance Flexible Broadband Photodetectors. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2024, 11, 2400545.

- Gao, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wei, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Huang, Z.; Du, B.; Xie, Z.; et al. Emerging Application of High-Entropy MXene in Efficient Photoelectrochemical-Type Photodetectors and Wideband Mode Lockers. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2024, 18, 2400082.

- Hu, C.; Wei, Z.; Li, L.; Shen, G. Strategy Toward Semiconducting Ti3C2Tx-MXene: Phenylsulfonic Acid Groups Modified Ti3C2Tx as Photosensitive Material for Flexible Visual Sensory-Neuromorphic System. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33, 2302188.

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Geng, H.; Tang, Z. Facile construction of MXene/Ge van der Waals Schottky junction with Al2O3 interfacial layer for high performance photodetection. Diamond and Related Materials 2023, 140, 110442.

- Ghosh, K.; Giri, P. Experimental and theoretical study on the role of 2D Ti3C2Tx MXenes on superior charge transport and ultra-broadband photodetection in MXene/Bi2S3 nanorod composite through local Schottky junctions. Carbon 2024, 216, 118515.

- Li, L.; He, Y.; Lin, T.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, T.; Zhou, C.; Li, G.; Wang, W. MXene/AlGaN van der Waals heterojunction self-powered photodetectors for deep ultraviolet communication. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 124.

- Xiong, G.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Feng, W. MXene-Germanium Schottky Heterostructures for Ultrafast Broadband Self-Driven Photodetectors. Advanced Electronic Materials 2022, 8, 2200620.

- Zheng, T.; Wang, W.; Du, Q.; Wan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, P. 2D Ti3C2-MXene nanosheets/ZnO nanorods for UV photodetectors. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2024, 7, 3050–3058.

- Nandi, S.; Ghosh, K.; Meyyappan, M.; Giri, P. 2D MXene Electrode-Enabled High-Performance Broadband Photodetector Based on a CVD-Grown 2D Bi2Se3 Ultrathin Film on Silicon. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2023, 5, 6985–6995.

- Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Shi, W.; Xie, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Y. A polarization-sensitive, high on/off ratio and self-powered photodetector based on Nb2CT x and Nd2CT x@ MoS2. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 155704.

- Li, L.; Shen, G. MXene based flexible photodetectors: progress, challenges, and opportunities. Materials Horizons 2023, 10, 5457–5473.

- Hao, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Li, G. Modulate the work function of MXene in MXene/InGaN heterojunction for visible light photodetector. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 125.

- Rhyu, H.; Park, C.; Jo, S.; Kang, M.H.; Song, W.; Lee, S.S.; Lim, J.; Myung, S. Stretchable Ag2S–MXene Photodetector Designed for Enhanced Electrical Durability and High Sensitivity. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2025.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.L. Highly Sensitive Photoelectric Detection and Imaging ... in 4H–SiC. Advanced Materials 2022. [CrossRef]

- Abdo, S.; As’ham, K.; Odebowale, A.A.; Akter, S.; Abdulghani, A.; Al Ani, I.A.M.; Hattori, H.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. A Near-Ultraviolet Photodetector Based on the TaC: Cu/4 H Silicon Carbide Heterostructure. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Alaloul, M.; Odebowale, A.A.; Ani, I.A.; As’Ham, K.; Abdo, S.; and, H.T.H. Near-ultraviolet photodetector using cerium hexaboride alloy. Journal of Modern Optics 2024, 71, 25–33, [. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wang, C.; Cai, J.; Karki, K.J. Probing Silicon Carbide with Phase-Modulated Femtosecond Laser Pulses. arXiv 2023, [2310.16315].

- Koller, P.; Astner, T.; Tissot, B.; Burkard, G.; Trupke, M. Strain-enabled control of the vanadium qudit in silicon carbide. arXiv 2025, [2501.05896].

- Abdo, S.; As’ham, K.; Odebowale, A.A.; Akter, S.; Abdulghani, A.; Al-Ani, I.; Hattori, H.T.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. A Near-Ultraviolet Photodetector Based on the TaC:Cu/4H Silicon Carbide Heterostructure. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 970. [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Somaweera, D.; As’ham, K.; Abdo, S.; Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Hattori, H.T. High-performance near-ultraviolet photodetector using Mo2C/SiC heterostructure. Advanced Photonics Research 2025, n/a, 2400210.

- Altaleb, S.; Patil, C.; Jahannia, B.; Asadizanjani, N.; Heidari, E.; Dalir, H. Photodetector for mid-infrared applications using few-layer vanadium carbide MXene. Proc. SPIE 2024. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Mondal, D.; Jana, D. First-Principles Calculations of Group-IV Carbide Quantum Dots ... ACS Applied Nano Materials 2025. [CrossRef]

- Remeš, Z.; Stuchlík, J.; Kupčík, J.; Babčenko, O. Thin Hydrogenated Amorphous Silicon Carbide Layers with Embedded Ge Nanocrystals. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 176. [CrossRef]

- Hattori, H.T.; Akter, S.; Al-Ani, I.A.M.; Li, Z. Near ultraviolet photoresponse of a silicon carbide and tantalum boride heterostructure. IEEE Photonics Journal 2023, 15, 5500607.

- Akter, S.; Abdo, S.; As’ham, K.; Al-Ani, I.; Hattori, H.T. Deep and near UV photodetector based upon Zirconium diboride and n-doped silicon carbide. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 6063–6070.

- Hattori, H.T.; Abdulghani, A.; Akter, S.; Somaweera, D.; As’ham, K. Hybrid organic carbazole and 4H silicon carbide photodetectors. ACS Applied Optical Materials 2024, 2, 2165–2174. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Hu, J.; Li, H.e.a. All-Optical Modulation Photodetectors Based on the CdS/Graphene/Ge Sandwich Structures. Advanced Science 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Zeng, L. Recent advances in two-dimensional graphitic carbon nitride based photodetectors. Materials & Design 2023, 242, 112405. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, H. Engineering graphitic carbon nitride for next-generation photodetectors. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 19763–19772. [CrossRef]

- Lionas, V.e.a. Photodetectors based on chemical vapor deposition or liquid processed multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Optical Materials 2023, 141, 114283. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.e.a. Probing Silicon Carbide with Phase-Modulated Femtosecond Laser Pulses. arXiv 2023, [2310.16315].

- Woo, S.e.a. High Detectivity Dual-Band Infrared Photodetectors ... Advanced Functional Materials 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, W.; Luo, G.; Yuan, C.; Ren, Y.; Lei, W. High performance visible photodetectors based on thin two-dimensional Bi2Te3 nanoplates. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 798, 656–664.

- Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, W.; Yuan, G.; Yuan, C.; Ren, Y.; Lei, W. Ultra-fast and high flexibility near-infrared photodetectors based on Bi2Se3 nanobelts grown via catalyst-free van der Waals epitaxy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 818, 152819.

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, X.; Luo, H.; Liu, J.; Mu, Z.; Liu, R.; Yuan, G.; Liang, Y.; Tan, J.; et al. Bi2O2Se nanoplates for broadband photodetector and full-color imaging applications. Nano Research 2023, 16, 7638–7645.

- Dun, C.; Hewitt, C.A.; Li, Q.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, J.; Marcus, G.; Schall, D.C.; Carrol, D.L. Self-Assembled Heterostructures: Selective Growth of Metallic Nanoparticles on V-2-VI3 Nanoplates. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1702968.

- Singh, S.; Kim, S.; Jeon, W.; Dhakal, K.P.; Kim, J.; Baik, S. Graphene grain size-dependent synthesis of single-crystalline Sb2Te3 nanoplates and the interfacial thermal transport analysis by Raman thermometry. Carbon 2019, 153, 164–172.

- Dong, G.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, L. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of Sb2Te3 nanosheets and thermoelectric properties of bulk samples prepared by spark plasma sintering. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2010, 20, 1976–1981.

- Zhang, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Suvorova, A.; Ren, Y.; Yuan, C.; Lei, W. Controlled growth of Sb2Te3 nanoplates and their applications in ultrafast near-infrared photodetection. Optical Materials 2024, 150.

- Yang, H.; et al. Sn vacancy engineering for enhancing the thermoelectric performance of two-dimensional SnS. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2019, 7, 3351–3359.

- Parenteau, M.; Carlone, C. Influence of Temperature and Pressure on the Electronic-Transitions in SnS and SnSe Semiconductors. Physical Review B 1990, 41, 5227–5234.

- Wang, H.; et al. SnSe Nanoplates for Photodetectors with a High Signal/Noise Ratio. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2021, 4, 13071–13078.

- Li, Z.; et al. Single Crystalline Nanostructures of Topological Crystalline Insulator SnTe with Distinct Facets and Morphologies. Nano Letters 2013, 13, 5443–5448.

- Yang, J.; et al. Ultra-Broadband Flexible Photodetector Based on Topological Crystalline Insulator SnTe with High Responsivity. Small 2018, 14, 1802598.

- Liu, J.; et al. Ultrathin High-Quality SnTe Nanoplates for Fabricating Flexible Near-Infrared Photodetectors. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 31810–31822.

- Xia, F.; Mueller, T.; Lin, Y.M.; Valdes-Garcia, A.; Avouris, P. Ultrafast graphene photodetector. Nature Nanotechnology 2009, 4, 839–843. [CrossRef]

- Pospischil, A.; Furchi, M.M.; Mueller, T. Solar-energy conversion and light emission in an atomic monolayer p–n diode. Nature Nanotechnology 2014, 9, 257–261. [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, N.; Chen, C.; Koester, S.J.; Li, M. Waveguide-integrated black phosphorus photodetector with high responsivity and low dark current. Nature Photonics 2015, 9, 247–252. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Padmanabhan, M.; Goswami, S.; Sai, T.P.; Ramalingam, G.; Raghavan, S.; Ghosh, A. Graphene–MoS2 hybrid structures for multifunctional photoresponsive memory devices. Nature Nanotechnology 2013, 8, 826–830. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Tan, H.; Yuan, J.; Fan, Z.; Wan, J.; Yu, W.W. Hybrid graphene–perovskite phototransistors with ultrahigh responsivity and gain. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1700007. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Lin, L.; Ni, Z.; Gu, X.; Ostrikov, K.K.; et al. Fast and broadband MoS2 photodetectors by coupling WO3–x semi-metal nanoparticles underneath. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2024, 193, 217–225.

- Aleithan, S.H.; Younis, U.; Alhashem, Z.; Ahmad, W. Graphene electrode-enhanced InSe/WSe2 van der Waals heterostructure for high-performance broadband photodetector with imaging capabilities. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 1006, 176356.

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shi, K.; Li, J.; Fang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Chu, X. A high-performance WS 2/ZnO QD heterojunction photodetector with charge and energy transfer. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2024, 12, 18291–18299.

- Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, R.; Lin, Y.; Guo, T.; Wu, L.; Hu, X.; Zhao, T.; Yan, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. High-sensitivity hybrid MoSe 2/AgInGaS quantum dot heterojunction photodetector. RSC advances 2024, 14, 1962–1969.

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, T.; Li, L.; Deng, Q.; Pan, Z.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. Ultrafast, broadband and polarization-sensitive photodetector enabled by MoTe2/Ta2NiSe5/MoTe2 van der Waals dual heterojunction. Science China Materials 2024, 67, 2182–2192.

- T. Mueller, F.X.; Avouris, P. Graphene photodetectors for high-speed optical communications. Nature Photonics 2010, 4, 297–301. [CrossRef]

- Kufer, D.; Konstantatos, G. Highly sensitive, encapsulated MoS2 photodetector with gate controllable gain and speed. Nano Letters 2015, 15, 7307–7313. [CrossRef]

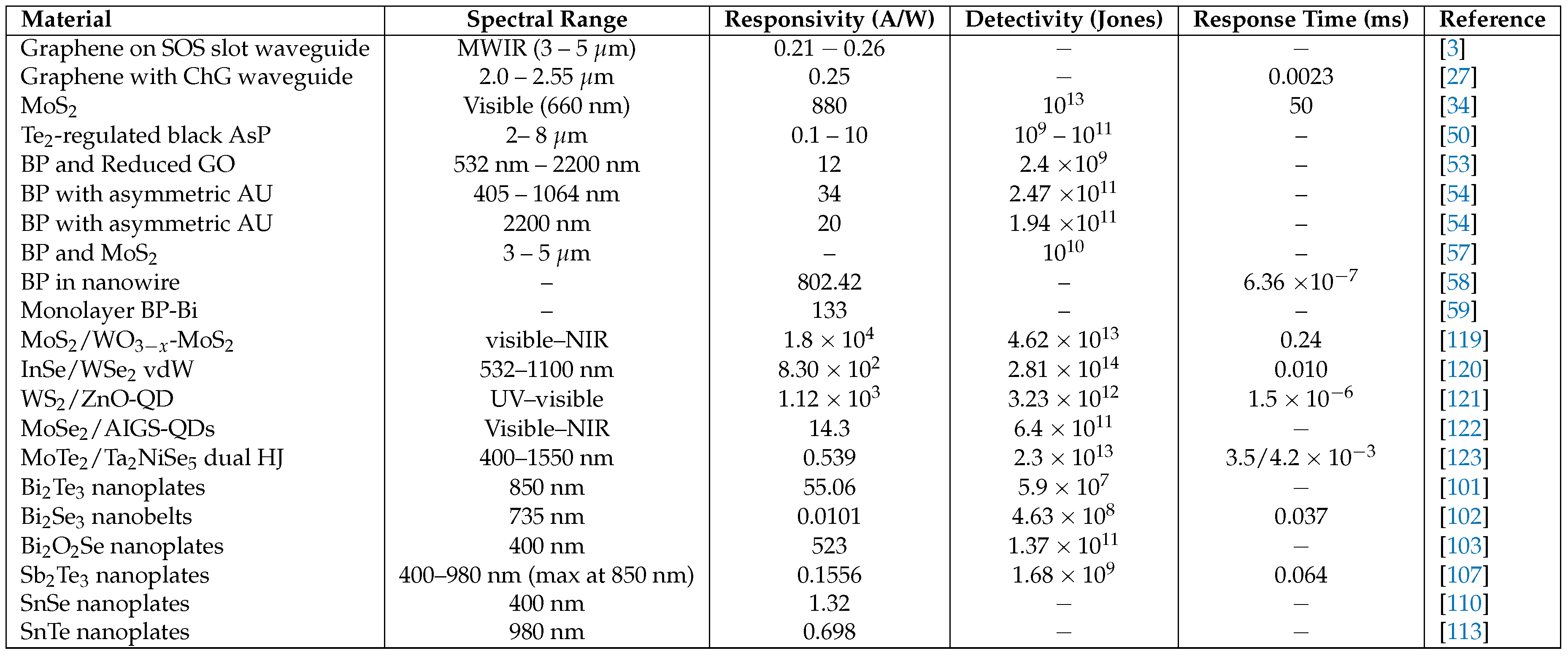

| Material | Spectral Range | Responsivity (A/W) | Detectivity (Jones) | Response Time (ms) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene on SOS slot waveguide | MWIR (3 – 5 m) | − | − | [3] | |

| Graphene with ChG waveguide | 2.0 – 2.55 m | − | [27] | ||

| MoS2 | Visible (660 nm) | 880 | 50 | [34] | |

| Te2-regulated black AsP | 2– 8 m | 0.1 – 10 | – | – | [50] |

| BP and Reduced GO | 532 nm – 2200 nm | 12 | 2.4 | – | [53] |

| BP with asymmetric AU | 405 – 1064 nm | 34 | 2.47 | – | [54] |

| BP with asymmetric AU | 2200 nm | 20 | 1.94 | – | [54] |

| BP and MoS2 | 3 – 5 m | – | – | [57] | |

| BP in nanowire | – | 802.42 | – | 6.36 | [58] |

| Monolayer BP-Bi | – | 133 | – | – | [59] |

| MoS2/WO3−x-MoS2 | visible–NIR | [119] | |||

| InSe/WSe2 vdW | 532–1100 nm | [120] | |||

| WS2/ZnO-QD | UV–visible | [121] | |||

| MoSe2/AIGS-QDs | Visible–NIR | − | [122] | ||

| MoTe2/Ta2NiSe5 dual HJ | 400–1550 nm | [123] | |||

| Bi2Te3 nanoplates | 850 nm | − | [101] | ||

| Bi2Se3 nanobelts | 735 nm | [102] | |||

| Bi2O2Se nanoplates | 400 nm | 523 | − | [103] | |

| Sb2Te3 nanoplates | 400–980 nm (max at 850 nm) | [107] | |||

| SnSe nanoplates | 400 nm | − | − | [110] | |

| SnTe nanoplates | 980 nm | − | − | [113] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).