1. Introduction

The biological and economic significance of terpenoids has prompted extensive research into the metabolic enzymes responsible for their chemical diversity (Karunanithi & Zerbe, 2019; Lange, 2015). Terpene biosynthesis adheres to common metabolic patterns, encompassing scaffold-forming and tailoring reactions (Anarat-Cappillino & Sattely, 2014). This process involves the enzymatic conversion of acyclic isoprenoid diphosphate precursors into various cyclic hydrocarbon products, catalysed by terpene synthases (TPSs), which serve as gatekeepers of the committed step in terpene formation (Chen et al., 2011; Tholl, 2006; Oldfield et al., 2012). The precursor's chain length determines the class of terpene produced: monoterpenes (C10) from geranyl diphosphate (GPP), sesquiterpenes (C15) from farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and diterpenes (C20) from geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) (Degenhardt et al., 2009; Gershenzon & Croteau, 1990). Structural studies reveal that TPS enzymes share a common fold comprised of variations of three conserved helical domains: α, βα, or γβα (Gao et al., 2012; Jia et al., 2022). Functional differences within these domains distinguish two major classes of TPSs: class II TPSs generate the initial carbocation intermediate via substrate protonation and catalyse scaffold rearrangements without cleaving the diphosphate ester bond, whereas class I TPSs use ionisation of the diphosphate moiety to form the intermediary carbocation (Cao et al., 2010; Davis & Croteau, 2000). Class I TPSs initiate catalysis through a divalent metal ion-dependent reaction triggered by the ionisation of the diphosphate group, leading to the formation of a high-energy allylic carbocation intermediate (Tholl, 2006; Trapp & Croteau, 2001). Subsequently, TPS enzymes orchestrate a series of carbon skeleton rearrangements, methyl shifts, and hydride transfers, culminating in a wide array of terpene structures (Gershenzon & Dudareva, 2007; Pichersky & Gershenzon, 2002).

Limonene synthase (LMS) is a model Class I monoTPS, catalysing the conversion of GPP to limonene via a simple cyclisation mechanism (Hyatt et al., 2007a; Kumar et al., 2017; Morehouse et al., 2017; Schiff & Oprian, 2023; Srividya et al., 2015, 2020; Xu et al., n.d., 2018; Yu, 2017). The reaction involves stereoselective GPP binding, diphosphate loss to form a geranyl cation, isomerisation to linalyl diphosphate (LPP), and cyclisation to the α-terpinyl cation, followed by deprotonation to yield limonene, whereas alternative termination pathways result in the production of other monoterpenes (Hyatt et al., 2007a; Srividya et al., 2015). Structural studies of LMS from Mentha spicata and Citrus sinensis (PDB: 2ONG (Hyatt et al., 2007a), 5UV1 (Kumar et al., 2017)) have revealed conserved features of plant monoTPSs, including an all-α-helical fold and metal-binding active sites. Substrate analogues have aided mechanistic insights, though crystallisation remains challenging due to enzyme flexibility.

This study reports the crystal structure of (-)-limonene synthase from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS), offering insights into terpene biosynthesis and enzyme specificity. Limonene, a key monoterpene contributing to the citrus aroma in cannabis, holds industrial relevance and is a target for metabolic engineering. The CsLMS apoprotein structure, resolved at 3.2 Å, reveals an open conformation with a solvent-exposed active site, suggesting a pre-catalytic state. Structural analysis highlights conserved features among monoterpene synthases, with variations including Y547 and a flexible J-K loop, likely shaping product specificity. These findings support terpene pathway engineering in cannabis and broader biotechnological contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Macromolecule Production

Cloning and recombinant protein production of CsLMS was carried out as described by (Wiles et al., 2025).

2.2. Crystallisation

Crystallisation screening was performed manually with a 48-condition screen developed for TPSs (Wiles et al., 2025), using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method at 293 K. The best-diffracting crystals of CsLMS were grown in a condition composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 100 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 30% PEG-3350. The obtained crystals were transferred to the reservoir solution supplemented with 28% (v/v) glycerol, mounted on a cryo-loop (Hampton Research) and then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen prior to collection of X-ray diffraction data.

2.3. Data Collection, Processing and Structure Solution

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Australian Synchrotron (MX2 beamline). The CsLMS structure was determined by molecular replacement using

Phaser crystallographic software in the CCP4 package (McCoy et al., 2007), using MsLMS (PDB entry 2ONH) as a search probe (Hyatt et al., 2007b). Iterative cycles of refinement and manual adjustment of the model were performed with REFMAC5 and COOT, respectively (Emsley et al., 2010; Potterton et al., 2003). Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood method” (Murshudov et al., 1997). Final refinement statistics are listed in

Table 1.

2.4. Product Identification by GC-MS

Enzyme assays were conducted in 2 ml Eppendorf tubes with a total reaction volume of 500 µl. Each reaction consisted of 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5% (v/v) glycerol, supplemented with 100 µM GPP and 10 µM enzyme. Reactions were overlaid with 500 µl hexane, mixed, and incubated for 16 hours at 37°C. Terpene products were extracted by vortexing for 30 seconds and transferring to glass vial inserts within 2 ml screw-top amber glass vials (Agilent) for GC-MS analysis.

GC-MS analysis was performed using a Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 GC with TSQ 8000 Evo MS and TriPlus autosampler. Separation used a TG-5SILMS column (60 m × 0.25 mm, 1.0 µm) with helium at 1.5 ml/min. Injections (1 µl, 5:1 split) were made at 280°C. Oven ramped from 50°C to 300°C at 5°C/min, held for 5 min. MS operated in full-scan mode (35–400 amu) with 70 eV ionisation. Data were acquired and analysed using XCalibur v4.7 and FreeStyle v1.8. Reaction products were identified by comparison with known terpene standards and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) mass spectral libraries.

2.5. Steady-State Kinetics

Kinetic analyses were conducted using a malachite green assay (Vardakou et al., 2014). Standard curves for Pi and PPi (0.01–100 µM) were generated for product quantification. Reactions (50 µl) included assay buffer (25 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), 25 mM 3-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS), 50 mM Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris), 2.5 mU of inorganic pyrophosphatase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Sigma), 100 µM GPP, and CsLMS (0.01–100 µM), incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 623 nm (Bio-Rad xMark™). Steady-state kinetics were performed using varying GPP concentrations (0.01–100 µM).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Overview of CsLMS

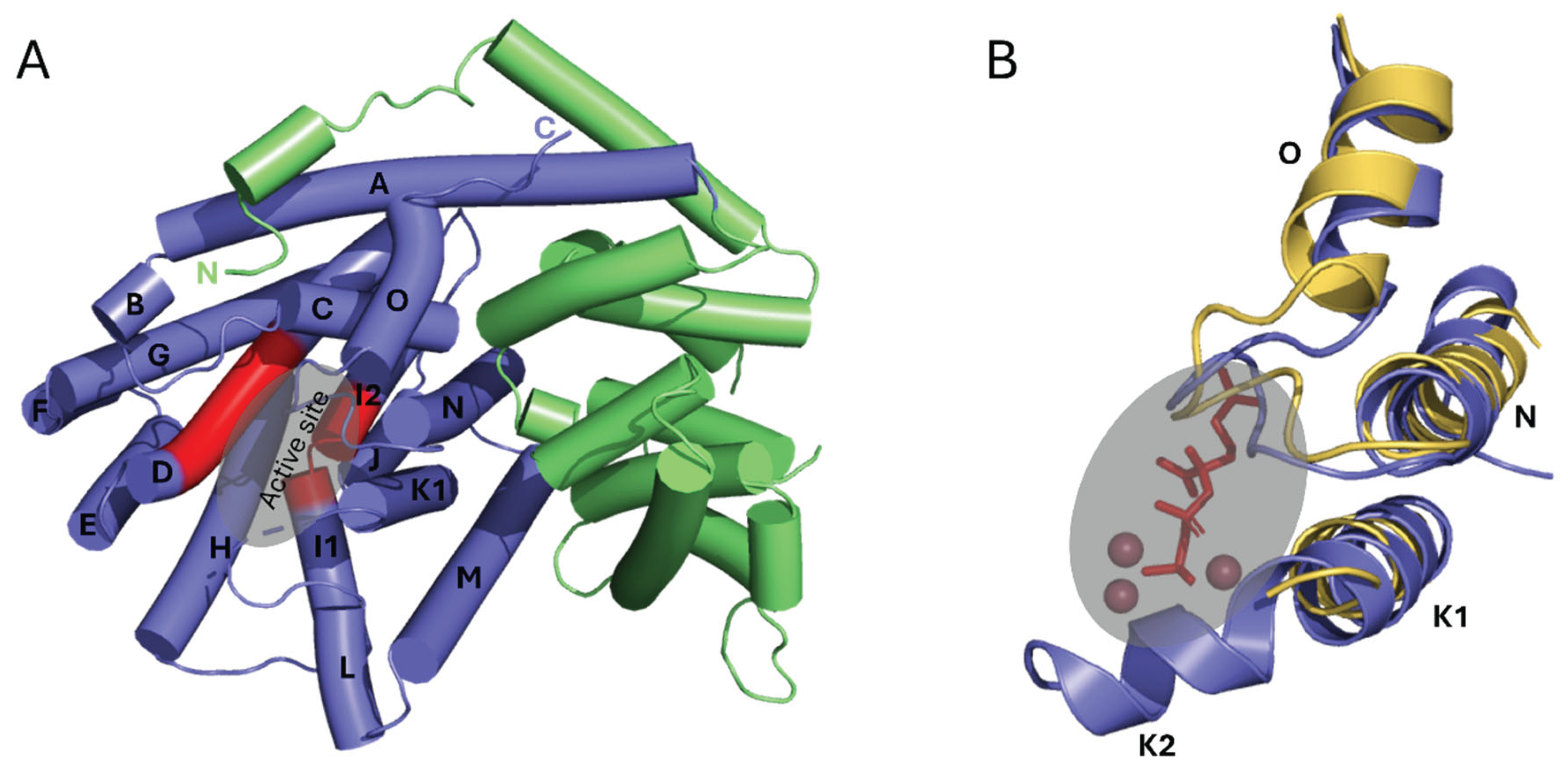

The catalytic mechanism of CsLMS was investigated by determining the crystal structure of wild-type CsLMS. The structure was obtained at a resolution of 3.2 Å, and it was found that the asymmetric unit consisted of a monomer of CsLMS, with a homodimer formed through crystallographic symmetry. For the purposes of analysis, the monomer was used unless otherwise stated. Size-exclusion chromatography confirmed CsLMS as monomeric (

Supplementary Figure S1). The crystal structure of CsLMS, with an overall resolution of 3.2 Å, adopts an α-helical bundle topology or isoprenoid fold in its unliganded form, as described by Wendt & Schulz, 1998 (

Figure 1). The isoprenoid fold consists of 15 mostly anti-parallel α-helices arranged in a compact bundle featuring distinct N- and C-terminal domains (

Figure 1A). The C-terminal domain (residues 270-567) houses the active site, which for CsLMS is deeply embedded within the catalytic domain, and includes residues W345, Y366, V367, L369, T370, I479, L514, Y547 and H553 (

Figure 1B). This structural organisation forms a hydrophobic binding pocket that supports the accommodation of the geranyl substrate, facilitating the cyclisation and production of limonene and other monoterpenes. The entrance to the active site is flanked by loops that contain conserved metal-binding motifs: ‘DDxxD’ and ‘DD’, positioned on opposing helices at the entrance of the active site (

Figure 1B.). For CsLMS the Mg

2+-coordinating aspartic acid residues are D373, D374, D377, D518, D519, which undergo conformational changes upon substrate binding, a feature observed in other class I TPSs. This is consistent with TPS functioning as metalloenzymes, where Mg

2+ or Mn

2+ plays a crucial role in stabilising the PP

i substrates leaving group and facilitating catalysis. These findings provide a structural basis for investigating CsLMS catalytic specificity and highlight conserved features among monoTPSs, which may guide future efforts in enzyme engineering for biotechnological applications.

3.2. Enzymatic Activity of CsLMS

The functional analysis of recombinant CsLMS confirmed its role as a monoTPS, catalysing the cyclisation of GPP to produce mainly limonene (74.72%), with minor products like β-pinene, terpinolene, α-pinene, and β-myrcene (Figure 2A), consistent with prior findings (Günnewich et al., 2007). Our study also identified additional minor products: α-terpineol, β-terpineol, camphene, fenchol, and geraniol, previously unreported for CsLMS, indicating a broader catalytic repertoire. Compared to other LMSs like Mentha spicata and Citrus sinensis, which show higher fidelity for limonene biosynthesis (94–99% limonene), CsLMS maintains a balance between specificity and catalytic flexibility, producing a more diverse product profile. This variability suggests an evolutionary adaptation enhancing terpene diversity in cannabis and contributing to chemotype variation. Genomic studies (Allen et al., 2019) indicate that CsTPS1 (CsLMS) is one of the top-expressed TPS genes, reinforcing its role in D-limonene biosynthesis in trichomes. Variability in limonene concentrations across cannabis cultivars adds complexity. A study by Allen et al., (2019) found TPS1, encoding D-limonene synthase, among the top five TPS transcripts detected, constituting about 70% of total TPS expression. The limited variability suggests few enzymes contribute to limonene production in C. sativa. This is supported by Booth et al., (2017),who analysed the correlation between TPS gene expression and metabolite concentration in Finola trichomes. The only significant correlation was between TPS1 (CsLMS) and D-limonene, indicating that CsLMS is the primary source of D-limonene in Finola trichomes, as an independent synthase would likely reduce this correlation.

While TPSs can produce multiple terpene products, CsLMS exhibits a high degree of control and mainly generates a single product. Its adaptability to produce both limonene and minor products offers insights into its evolutionary development of a broad catalytic repertoire. This aligns with the knowledge that these molecules likely arise from the same carbocation intermediate (α-terpinyl cation) and are often by-products of synthases that produce limonene. These findings enhance understanding of CsLMSs catalytic properties and its potential for metabolic engineering aimed at optimising monoterpene production.

To inform protein engineering of TPSs, understanding catalytic activity is essential. We chose a high-throughput enzyme assay based on phosphate production, performed without specialised equipment. The steady-state kinetic parameters (V

max, K

m, k

cat) were conducted in triplicate and analysed with non-linear regression using the Michaelis–Menten model in Graphpad Prism. The kinetic profiles of CsLMS are shown in

Figure 2 B, with substrate concentrations (FPP, GPP) ranging from 0 to 100 µm. The analysis revealed that CsTPS1SK has a low K

m for GPP (7.809 ± 0.678 µM) alongside a high V

max (0.2038 ± 0.0053 µM⁻¹ s⁻¹) and k

cat (0.0204 s⁻¹), indicating strong substrate affinity and rapid catalysis, highlighting its efficiency in monoterpene production (

Figure 2B). Günnewich et al., (2007) first discovered (-)-limonene synthase in

C. sativa, reporting a K

m of 6.8 μM, V

max of 1.1 x 10-4 µmol/min, V

max/K

m of 0.016, a pH optimum of 6.5, and a temperature optimum of 40°c. However, this does not clarify the catalysis rate for individual terpenes. Given the broad spectrum of monoterpene products of CsLMS from GPP, utilising GC-MS would provide insights into individual rates of catalysis for these products. Approximately 74.72% of CsLMS products are (-)-limonene, indicating that most catalytic efficiency targets GPP conversion to limonene, while other products may result from premature deprotonation or cyclisation, suggesting substrate plasticity for metabolic engineering applications.

3.3. Comparison of the Overall Structure of CsLMS to That of Other TPS

Multiple sequence and structural alignments of CsLMS with limonene synthases from

M. spictata (MsLMS; (Hyatt et al., 2007a)) and

C. sinensis (CsiLMS; (Kumar et al., 2017)), reveal high structural similarity, including conserved active site topology that supports a similar catalytic mechanism. Subtle differences in aromatic residue arrangement suggest variations in substrate stabilisation, explaining differences in product specificity. Superposition of apo-CsLMS and FGPP-bound CsiLMS (PDB entry 2ONG) shows no significant fold differences, despite only 45.41% sequence identity (

Figure 3B). Notable differences observed in the catalytic C-terminal domain reflect distinct conformational states: an open active site in apo-CsLMS and a closed, ligand-bound conformation in FGPP-bound CsiLMS. The N-terminal strand and loop between helices N and O form a lid over the active site in CsLMS (

Figure 4A). In FGPP-bound CsiLMS, a secondary K2 α-helix shifts inward to cover the active site, as described previously (

Figure 4B; (Morehouse et al., 2017). In apo-CsLMS, poor electron density in the K2 region mirrors other apo structures like bornyl diphosphate synthase and 1,8-cineole synthase, indicating an open, flexible conformation. In this open state, the K2 helix is thought to stabilise through hydrogen bonds with residues on helix M, disrupted upon active site closure during substrate binding.

Six α-helices of the TPS fold (C, D, H, I1-I2, K1-K2, N) form the active site cavity walls, primarily lined with nonpolar, hydrophobic, and aromatic residues. In CsLMS, helix N is a half-turn longer, and the loop between N and O projects outward compared to the ligand-bound structure. Upon substrate binding, this loop moves to cover the active site, partially unwinding helix N by about half a turn at residue Y547. This unwinding repositions the side chain of Y547, allowing it to flip inward toward the active site. In the closed conformation, the hydroxyl group of Y547 approaches the metal ion-coordinating residue D488 and gets closer to the bound FGPP molecule. These structural changes suggest that the movement of the phenolic side chain into the active site is key for catalysis, likely aiding in stabilising carbocation intermediates and efficient product formation. Transitioning to a closed conformation is critical for excluding solvent molecules that could quench high-energy carbocation intermediates, thus maintaining the reaction mechanism's fidelity. Furthermore, the structural flexibility in the apo-CsLMS structure may contribute to its broader product profile, including minor oxygenated monoterpene byproducts.

4. Conclusion

This study presents the first crystal structure of (-)-limonene synthase from Cannabis sativa, resolved at 3.2 Å resolution. The structure reveals an "open" conformation, offering insights into how the enzyme binds its substrate and catalyses the production of (-)-limonene, a commercially important monoterpene. Structural comparisons show high similarity to other limonene synthases, with a conserved active site, but subtle differences in aromatic residues and a ''lid” domain over the active site combined with a shortened C-terminal loop in CsLMS may explain variations in product specificity. Functional analysis confirmed that CsLMS primarily produces limonene yet also produces newly identified minor byproducts. CsLMS exhibits strong substrate affinity and rapid catalysis, highlighting its efficiency in monoterpene production. The research improves the understanding of terpene biosynthesis and offers a basis for developing metabolic engineering strategies to produce specialized metabolites in cannabis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Danielle Wiles: Writing: review & editing, Writing: original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualisation. James Roest: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Writing: review & editing. Julian P. Vivan: Writing: review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation. Travis Beddoe: Writing: review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualisation.

Availability of data and materials: The model coordinates and structure factors for CsLMS have been deposited in the PDB (

https://www.rcsb.org/pdb) under accession code 9OPS.

Declaration of competing interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Research Industrial Transformation Research Hub for Medicinal Agriculture (IH180100006). This research was undertaken in part using the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, part of ANSTO, and made use of the ACRF detector.

References

- Allen, K. D., McKernan, K., Pauli, C., Roe, J., Torres, A., & Gaudino, R. (2019). Genomic characterization of the complete terpene synthase gene family from Cannabis sativa. PLoS ONE, 14(9), e0222363. [CrossRef]

- Anarat-Cappillino, G., & Sattely, E. S. (2014). The chemical logic of plant natural product biosynthesis. In Current Opinion in Plant Biology (Vol. 19, pp. 51–58). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Booth, J. K., Page, J. E., & Bohlmann, J. (2017). Terpene synthases from Cannabis sativa. PLoS ONE, 12(3). [CrossRef]

- Cao, R., Zhang, Y., Mann, F. M., Huang, C., Mukkamala, D., Hudock, M. P., Mead, M. E., Prisic, S., Wang, K., Lin, F. Y., Chang, T. K., Peters, R. J., & Oldfield, E. (2010). Diterpene cyclases and the nature of the isoprene fold. Proteins: Structure, Function and Bioinformatics, 78(11), 2417–2432. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Tholl, D., Bohlmann, J., & Pichersky, E. (2011). The family of terpene synthases in plants: A mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant Journal, 66(1), 212–229. [CrossRef]

- Davis, E. M., & Croteau, R. B. (2000). Cyclization enzymes in the biosynthesis of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes. In Topics in Current Chemistry (Vol. 301).

- Degenhardt, J., Köllner, T. G., & Gershenzon, J. (2009). Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases and the origin of terpene skeletal diversity in plants. In Phytochemistry (Vol. 70, Issues 15–16, pp. 1621–1637). Pergamon. [CrossRef]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G., & Cowtan, K. (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography, 66(4), 486–501. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Honzatko, R. B., & Peters, R. J. (2012). Terpenoid synthase structures: A so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. In Natural Product Reports (Vol. 29, Issue 10, pp. 1153–1175). Royal Society of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Gershenzon, J., & Croteau, R. (1990). Biochemistry of the Mevalonic Acid Pathway to Terpenoids.

- Gershenzon, J., & Dudareva, N. (2007). The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. In Nature Chemical Biology (Vol. 3, Issue 7, pp. 408–414). [CrossRef]

- Günnewich, N., Page, J. E., Köllner, T. G., Degenhardt, J., & Kutchan, T. M. (2007). Functional expression and characterization of trichome-specific (-)-limonene synthase and (+)-α-pinene synthase from Cannabis sativa. Natural Product Communications, 2(3), 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J., Spellmon, N., Zhang, Y., Doughan, M., Li, C., & Yang, Z. (2017). Protein crystallization: Eluding the bottleneck of X-ray crystallography. In AIMS Biophysics (Vol. 4, Issue 4, pp. 557–575). American Institute of Mathematical Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D. C., Youn, B., Zhao, Y., Santhamma, B., Coates, R. M., Croteau, R. B., & Kang, C. (2007a). Structure of limonene synthase, a simple model for terpenoid cyclase catalysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(13), 5360–5365. [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D. C., Youn, B., Zhao, Y., Santhamma, B., Coates, R. M., Croteau, R. B., & Kang, C. (2007b). Structure of limonene synthase, a simple model for terpenoid cyclase catalysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(13), 5360–5365. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q., Brown, R., K, T. G., Fu, J., Chen, X., Ka-Shu Wong, G., Gershenzon, J., Peters, R. J., & Chen, F. (2022). Origin and early evolution of the plant terpene synthase family. [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, P. S., & Zerbe, P. (2019). Terpene Synthases as Metabolic Gatekeepers in the Evolution of Plant Terpenoid Chemical Diversity. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. P., Morehouse, B. R., Matos, J. O., Malik, K., Lin, H., Krauss, I. J., & Oprian, D. D. (2017). Structural Characterization of Early Michaelis Complexes in the Reaction Catalyzed by (+)-Limonene Synthase from Citrus sinensis Using Fluorinated Substrate Analogues. Biochemistry, 56(12), 1716–1725. [CrossRef]

- Lange, B. M. (2015). The evolution of plant secretory structures and emergence of terpenoid chemical diversity. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 66, 139–159. [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C., & Read, R. J. (2007). Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of Applied Crystallography, 40(4), 658–674. [CrossRef]

- Morehouse, B. R., Kumar, R. P., Matos, J. O., Olsen, S. N., Entova, S., & Oprian, D. D. (2017). Functional and Structural Characterization of a (+)-Limonene Synthase from Citrus sinensis. Biochemistry, 56(12), 1706–1715. [CrossRef]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. In Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography (Vol. 53, Issue 3, pp. 240–255). [CrossRef]

- Pegan, S., Tian, Y., Sershon, V., & Mesecar, A. (2009). A Universal, Fully Automated High Throughput Screening Assay for Pyrophosphate and Phosphate Release from Enzymatic Reactions. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening, 13(1), 27–38. [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E., & Gershenzon, J. (2002). The formation and function of plant volatiles: perfumes for pollinator attraction and defense. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 5(3), 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Potterton, E., Briggs, P., Turkenburg, M., & Dodson, E. (2003). A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallographica - Section D Biological Crystallography, 59(7), 1131–1137. [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, P., Berz, J., Kreisel, P., & Schwalbe, H. (2019). “CodonWizard” – An intuitive software tool with graphical user interface for customizable codon optimization in protein expression efforts. Protein Expression and Purification, 160, 84–93. [CrossRef]

- Schiff, W. H., & Oprian, D. D. (2023). Mutational Analysis of (+)-Limonene Synthase. Biochemistry, 62(16), 2472–2479. [CrossRef]

- Srividya, N., Davis, E. M., Croteau, R. B., & Lange, B. M. (2015). Functional analysis of (4S)-limonene synthase mutants reveals determinants of catalytic outcome in a model monoterpene synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(11), 3332–3337. [CrossRef]

- Srividya, N., Lange, I., & Lange, B. M. (2020). Determinants of Enantiospecificity in Limonene Synthases. Biochemistry, 59(17), 1661–1664. [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D. (2006). Terpene synthases and the regulation, diversity and biological roles of terpene metabolism. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 9(3), 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Trapp, S. C., & Croteau, R. B. (2001). Genomic Organization of Plant Terpene Synthases and Molecular Evolutionary Implications.

- Vardakou, M., Salmon, M., Faraldos, J. A., & O’Maille, P. E. (2014). Comparative analysis and validation of the malachite green assay for the high throughput biochemical characterization of terpene synthases. MethodsX, 1, e187–e196. [CrossRef]

- Wendt, U., & Schulz, G. E. (1998). Isoprenoid biosynthesis: manifold chemistry catalyzed by similar enzymes. Structure, 6, 127–133. http://biomednet.com/elecref/0969212600600127.

- Wiles, D., Roest, J., Shanbhag, B., Vivian, J., & Beddoe, T. (2025). Integrated Platform for Structural and Functional Analysis of Cannabis sativa Terpene Synthases. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Ai, Y., Wang, J., Xu, J., Zhang, Y., Phytochemistry, D. Y.-, & 2017, undefined. (n.d.). Converting S-limonene synthase to pinene or phellandrene synthases reveals the plasticity of the active site. Elsevier. Retrieved June 7, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031942217300882?casa_token=kPos2qvmfeMAAAAA:lzc4Ji2MyvlW5mrxQpgFeCUgcblqvTv1p2m9RyEMM3JbTbij43FfnnO1FpNqamueTCVtfZan5WUt.

- Xu, J., Xu, J., Ai, Y., Farid, R. A., Tong, L., & Yang, D. (2018). Mutational analysis and dynamic simulation of S-limonene synthase reveal the importance of Y573: Insight into the cyclization mechanism in monoterpene synthases. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 638(December 2017), 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q. (2017). Exploring the Monoterpene Cyclization Mechanism by Studying (+)-Limonene Synthase Using Novel Fluorinated Substrate Analogues. 13(3), 1576–1580. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of CsLMS. A. Cartoon representation of the overall CsLMS structure. The N- and C-termini are labelled and coloured green and purple, respectively. The active site contains the docked substrate geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP; black) and a tricluster of magnesium ions (red spheres). B. Architecture of the CsLMS substrate and cofactor binding pocket. Ball-and-stick representation of the terpene synthase (TPS) binding site, highlighting the docked GPP and magnesium ions (from the Mentha spicata limonene synthase, PDB: 2ONH) as black sticks and red spheres, respectively. Amino acid residues within 5 Å of the docked GPP and magnesium ions are shown as sticks. All structural visualisations were generated using PyMOL.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of CsLMS. A. Cartoon representation of the overall CsLMS structure. The N- and C-termini are labelled and coloured green and purple, respectively. The active site contains the docked substrate geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP; black) and a tricluster of magnesium ions (red spheres). B. Architecture of the CsLMS substrate and cofactor binding pocket. Ball-and-stick representation of the terpene synthase (TPS) binding site, highlighting the docked GPP and magnesium ions (from the Mentha spicata limonene synthase, PDB: 2ONH) as black sticks and red spheres, respectively. Amino acid residues within 5 Å of the docked GPP and magnesium ions are shown as sticks. All structural visualisations were generated using PyMOL.

Figure 2.

Functional analysis of Limonene synthase from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS) A. GC-MS traces showing the monoterpene products of CsLMS. Traces show GC-MS total ion chromatogram from CsTPS assays with GPP, GGPP, FPP and a boiled enzyme control to account for background noise. Peaks: a) α-pinene, b) camphene c) β-myrcene, d) β -pinene, e) limonene, f) terpinolene, g) fenchol*, h) β-terpineol*, i) α-terpineol, j) geraniol, i.s. = internal standard. *No reference standard available, putative identification of compound using National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library. B. Michaelis-Menten kinetics of CsLMS (A) Non-linear regression analysis of steady-state kinetic assays for CsLMS enzymes using geranyl diphosphate (GPP) as the substrate, showing the rate of GPP catalysis (µM of GPP consumed per second). Each curve represents the data fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine kinetic parameters.

Figure 2.

Functional analysis of Limonene synthase from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS) A. GC-MS traces showing the monoterpene products of CsLMS. Traces show GC-MS total ion chromatogram from CsTPS assays with GPP, GGPP, FPP and a boiled enzyme control to account for background noise. Peaks: a) α-pinene, b) camphene c) β-myrcene, d) β -pinene, e) limonene, f) terpinolene, g) fenchol*, h) β-terpineol*, i) α-terpineol, j) geraniol, i.s. = internal standard. *No reference standard available, putative identification of compound using National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library. B. Michaelis-Menten kinetics of CsLMS (A) Non-linear regression analysis of steady-state kinetic assays for CsLMS enzymes using geranyl diphosphate (GPP) as the substrate, showing the rate of GPP catalysis (µM of GPP consumed per second). Each curve represents the data fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine kinetic parameters.

Figure 3.

Structural comparison of limonene synthases (LMS) from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS), Citrus sinensis (CsiLMS), and Mentha spicata (MsLMS). A. Ribbon representation of CsLMS overlayed with C. sinensis limonene synthase in its holoenzyme form complexed with fluorinated geranyl pyrophosphate (FGPP) (CsiLMS; PDB: 5UV1), and M. spicata limonene synthase in its apo form (MsLMS; PDB: 2ONG), highlighting the active site. B. Sequence alignment of CsLMS, CsiLMS, and MsLMS, generated using Geneious with Clustal Omega. Strictly conserved residues are highlighted in purple, while similar residues are shaded in a lighter purple.

Figure 3.

Structural comparison of limonene synthases (LMS) from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS), Citrus sinensis (CsiLMS), and Mentha spicata (MsLMS). A. Ribbon representation of CsLMS overlayed with C. sinensis limonene synthase in its holoenzyme form complexed with fluorinated geranyl pyrophosphate (FGPP) (CsiLMS; PDB: 5UV1), and M. spicata limonene synthase in its apo form (MsLMS; PDB: 2ONG), highlighting the active site. B. Sequence alignment of CsLMS, CsiLMS, and MsLMS, generated using Geneious with Clustal Omega. Strictly conserved residues are highlighted in purple, while similar residues are shaded in a lighter purple.

Figure 4.

A. Cylindrical helix model of apo-limonene synthase from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS). The N-terminal domain is shown in green, and the C-terminal domain is shown in blue. Residues involved in conserved metal ion and substrate binding are highlighted in red. B. Superposition of the active sites of apo-CsLMS (yellow) and FGPP-bound limonene synthase from Citrus sinensis (CsiLMS; PDB ID: 2ONG, blue). The overlay highlights the N-terminal strand and the loop between helices N and O, which together form a lid covering the active site in the closed conformation of LMS, while the K2 α-helix supports the active site from below.

Figure 4.

A. Cylindrical helix model of apo-limonene synthase from Cannabis sativa (CsLMS). The N-terminal domain is shown in green, and the C-terminal domain is shown in blue. Residues involved in conserved metal ion and substrate binding are highlighted in red. B. Superposition of the active sites of apo-CsLMS (yellow) and FGPP-bound limonene synthase from Citrus sinensis (CsiLMS; PDB ID: 2ONG, blue). The overlay highlights the N-terminal strand and the loop between helices N and O, which together form a lid covering the active site in the closed conformation of LMS, while the K2 α-helix supports the active site from below.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for recombinant CsLMS (PDB ID: 9OPS).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for recombinant CsLMS (PDB ID: 9OPS).

| Data collection statistics |

| Temperature (K) |

100 |

| X-ray source |

MX2 Australian synchrotron |

| Space group |

P3221 |

| Cell Dimensions (Å) |

a = 97.3, b = 97.3, c = 117.7 |

| Resolution (Å) |

60 – 3.2 (3.25 – 3.20) |

| Total no. observations |

81866 (4326) |

| No. unique observations |

10899 (545) |

| Multiplicity |

7.5 (7.9) |

| Data completeness (%) |

99.1 (100) |

| I/sI |

7.5 (5.2) |

| Rmerge (%)1

|

0.29 (0.45) |

| CC (1/2) |

0.98 (0.12) |

| Refinement statistics |

| Non-hydrogen atoms |

| Protein |

4290 |

| Rfactor (%)2

|

18 |

| Rfree (%)2

|

23.0 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideality |

| Bond lengths (Å) |

0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) |

0.591 |

| Dihedrals (°) |

14.5 |

| Ramachandran plot |

| Favoured regions (%) |

94.9 |

| Allowed regions (%) |

5.1 |

| B-factors (Å2) |

| Wilson |

41 |

| Average protein |

42 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).