1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among patients presenting to emergency departments (EDs). Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), particularly those originating from peptic ulcers, is associated with high mortality rates and often necessitates urgent blood transfusion. The annual incidence of UGIB ranges from 84 to 160 per 100,000 adults, with reported mortality rates between 5% and 10% [

1]. In contrast, lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) typically follows a milder course; however, in elderly populations, it can result in severe outcomes [

2]. Blood transfusions administered for GI bleeding aim to reduce in-hospital mortality and minimize the risk of complications, representing a crucial therapeutic approach [

3].

Blood transfusion in GI bleeding is commonly performed to maintain hemodynamic stability and ensure adequate tissue perfusion. However, there is no consensus regarding transfusion strategies. Some studies suggest that liberal transfusion approaches may increase the risk of mortality and rebleeding [

4]. Particularly, in patients with portal hypertension, liberal transfusion strategies have been linked to a heightened risk of bleeding, leading to adverse outcomes [

5]. In contrast, restrictive transfusion strategies, aiming for lower hemoglobin targets (generally 7 g/dL), have shown better outcomes [

6]. Additionally, a systematic review conducted by Cochrane reported that restrictive transfusion strategies do not increase 30-day mortality compared to liberal strategies and may, in some cases, reduce the need for transfusion [

7].

Nevertheless, there is limited data on the impact of the transfusion site (ED vs. inpatient units) on clinical outcomes. Existing studies have not clearly established whether significant differences in mortality and hospital stay duration exist between patients who received transfusions in the ED versus inpatient units [

4]. Furthermore, comprehensive analyses linking risk scores such as the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS), AIMS65 (Albumin-International Normalized Ratio-Mental Status-Systolic Blood Pressure-65), and Rockall with transfusion location are also scarce [

8].

The aim of this study is to retrospectively evaluate the impact of the transfusion site (ED vs. inpatient units) on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with GI bleeding who received red blood cell suspension (RBCS) transfusion. We hypothesize that rapid transfusions performed in the ED may reduce mortality; however, transitioning to inpatient care after stabilization might introduce additional risks. In this context, we compared the effects of ED versus inpatient transfusions on mortality and hospital stay duration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in the ED of a tertiary care hospital. The annual number of ED visits is approximately 250,000. The study period covers patients admitted to the ED with a diagnosis of GI bleeding between June 1, 2021, and June 1, 2023. Only hospitalized patients who received RBCS transfusion were retrospectively analyzed. The primary outcomes were mortality rates and length of hospital stay among transfused patients.

2.2. Patient Selection

Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

Patients under 18 years of age

Patients with a GI bleeding diagnosis followed on an outpatient basis

Patients diagnosed with GI bleeding who did not receive a transfusion

Patients who underwent cross-match testing for reasons other than GI bleeding

Patients with incomplete or inaccessible data

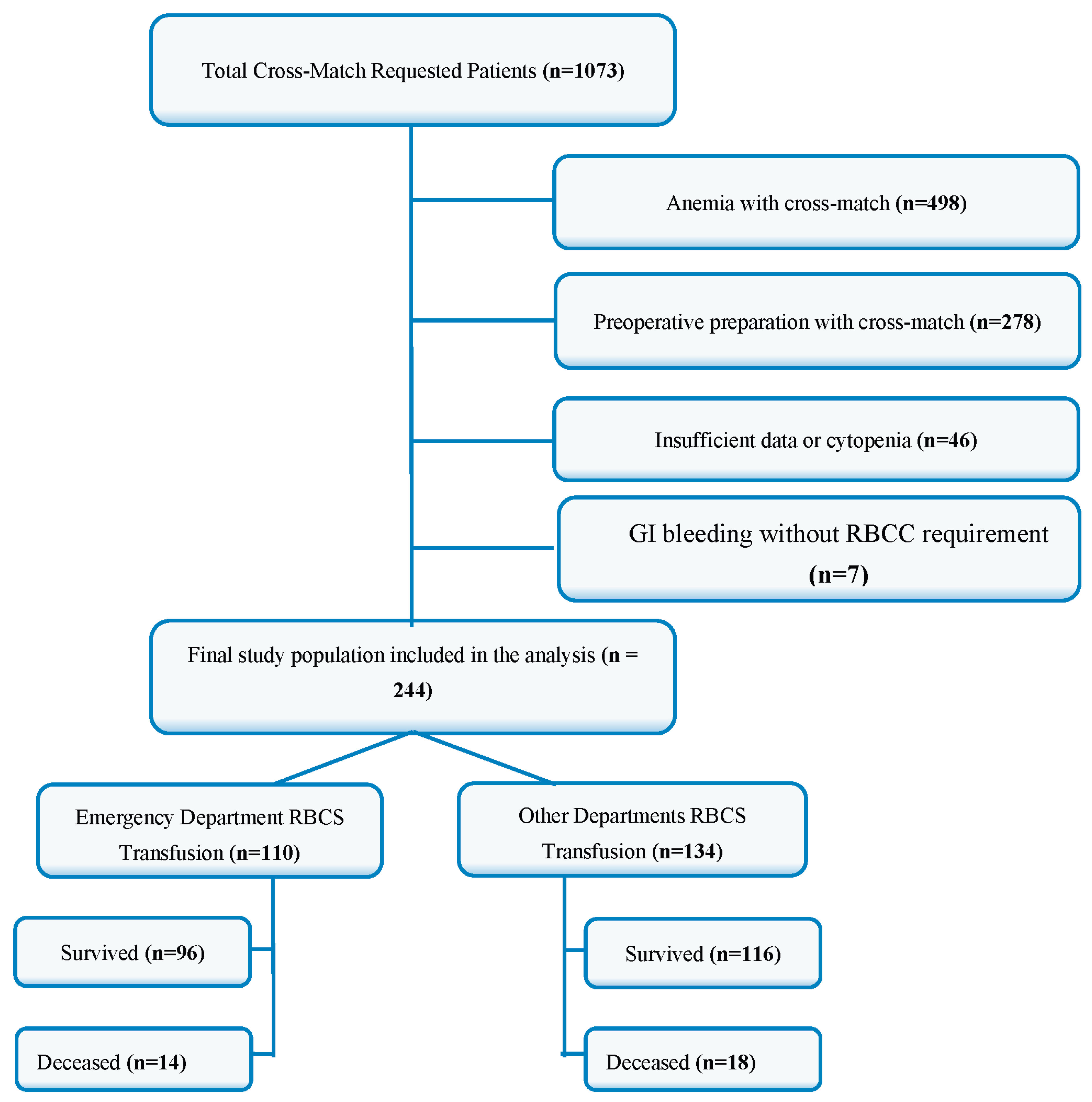

After applying these criteria, a total of 244 patients were included in the study (

Figure 1.).

2.3. Data Collection

Data for this study were retrospectively obtained from the hospital information management system (HIMS) of the tertiary care hospital. Demographic data (age, gender), presenting complaints, vital signs, and laboratory parameters (hemoglobin, hematocrit, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin, INR) were recorded. Additionally, information regarding the amount of RBCS transfused and the transfusion location (ED or inpatient unit) was collected. Outcome variables, including length of hospital stay and mortality status, were also retrieved from the same system and recorded for analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were presented as mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of distribution for continuous variables. For normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors independently associated with mortality. Variables with p<0.05 in univariate analysis and clinically significant variables (p<0.2) were included in the multivariate model. Multicollinearity was assessed, and variables with a correlation coefficient >0.75 were excluded. Model fit was evaluated using the Omnibus test and was found to be significant (p<0.01). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.5. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kütahya Health Sciences University (approval number: 2023/09-29, dated August 16, 2023). Additionally, necessary permissions were obtained from the Kütahya Provincial Health Directorate Scientific Research Evaluation Committee (approval number: 2024/9, dated January 31, 2024).

3. Results

The demographic analysis revealed that in the group receiving RBCS transfusion in the ED, 49 patients (44.5%) were male, and 61 patients (55.5%) were female. In contrast, among the patients who received transfusion in other hospital departments, 77 patients (57.7%) were male, and 57 patients (42.5%) were female. A statistically significant difference was observed between the groups regarding gender distribution (p=0.045).

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of age (p=0.074) or the presence of comorbid conditions such as coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT), stroke, atrial fibrillation (AF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), malignancy, cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and congestive heart failure (CHF). The demographic and comorbidity characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1.

The analysis of laboratory parameters showed that patients who received RBCS transfusion in the ED had significantly lower hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (Hct) levels compared to those in other hospital departments (p<0.001). No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of other laboratory parameters, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, platelet count (Plt), international normalized ratio (INR), and albumin levels. The detailed laboratory values are presented in

Table 2.

The comparison of hospital stay and mortality rates between the groups revealed that the median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the ED group (4 days) compared to other departments (5.5 days) (p<0.001). The number of RBCS units transfused did not differ significantly between the groups (p=0.142).

Regarding mortality outcomes, 14 patients (12.7%) in the ED group and 18 patients (13.4%) in the other departments group were recorded as deceased. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups in terms of mortality rates (p=0.871). The distribution of hospital stay duration and mortality rates is presented in

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of mortality among patients receiving RBCS transfusion. The model included six variables: mean arterial pressure (MAP), albumin, creatinine, Hb, length of hospital stay, and transfusion location (ED vs. other departments). The model fit was confirmed using the omnibus test (p<0.01), indicating that the model was statistically significant. The model explained approximately 47% of the variance in mortality (Nagelkerke R2=0.472).

Among the six variables analyzed, five were identified as independent predictors of mortality (p<0.05). The most significant predictors were MAP and albumin, both showing a protective effect, as indicated by OR values less than 1. In contrast, hemoglobin, creatinine, and length of hospital stay had OR values greater than 1, indicating an increased risk of mortality with higher values. The variable representing transfusion location (ED vs. other departments) did not reach statistical significance (p=0.516), suggesting that the location of RBCS administration did not independently affect mortality in this model. The detailed results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in

Table 4.

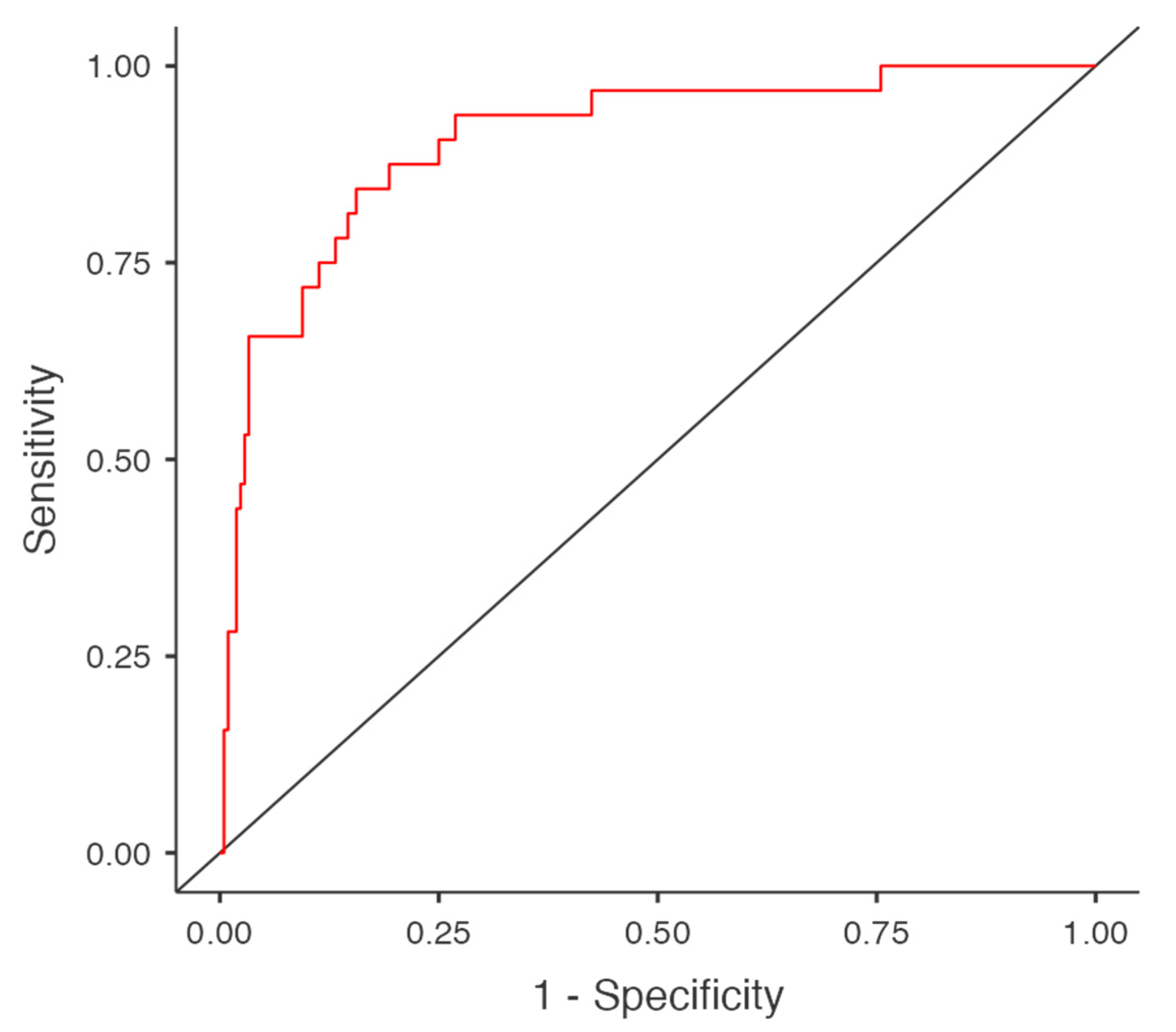

The diagnostic accuracy of the model was assessed using the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, which was calculated as 0.906. Sensitivity and specificity were found to be 46.9% and 97.6%, respectively. The model's accuracy was 91%, indicating good predictive power despite moderate sensitivity. (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

GI bleeding is a critical condition frequently encountered in EDs and remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Optimal transfusion strategies, particularly regarding the timing and location of RBCS administration, continue to be debated. Recent studies have shown that early transfusion in the ED can improve patient outcomes by stabilizing hemodynamics and reducing hospital stay without significantly increasing mortality [

9,

10].

In this study, we evaluated the effect of RBCS transfusion location on mortality and length of hospital stay in patients admitted with GI bleeding. Our findings revealed that transfusion performed in the ED was associated with a significantly shorter length of hospital stay, but no difference in mortality compared to transfusion in inpatient units. These results suggest that the primary advantage of ED-based transfusion may be related to more efficient patient management rather than improved survival outcomes. Similar observations have been reported in recent guidelines that emphasize a balance between early stabilization and careful transfusion practices to avoid complications [

11].

When evaluating the demographic and comorbidity characteristics of the patients, it was observed that male patients constituted the majority of the cohort. Similar studies have also demonstrated that male patients tend to present more frequently to EDs with GI bleeding [

3]. For instance, a recent study by Sezer et al. (2025) evaluated the effectiveness of various scoring systems, including GBS, AIMS65, Rockall, and the International Normalized Bleeding Score (INBS; ABC), in predicting hospital admission, transfusion need, and mortality. Consistent with our findings, they reported that approximately 65% of patients admitted to the ED due to GI bleeding were male [

8].

However, our study revealed that patients requiring early RBCS transfusion and receiving it in the ED were predominantly female. This can be explained by the physiological differences in Hb levels and blood volume between genders. Since the threshold for RBCS transfusion is generally set at 7 g/dL, females, who typically have lower baseline Hb levels and reduced blood volume compared to males, may meet this criterion earlier. This observation is consistent with studies highlighting that lower baseline Hb levels in females may lead to earlier decisions for transfusion, even with moderate reductions [

12,

13].

In our study, comorbid conditions did not significantly influence the need for early RBCS transfusion in the ED. This finding is consistent with a 2024 study, which reported that comorbidities such as antithrombotic therapy increased the risk of mortality and rebleeding in patients presenting with GI bleeding but did not directly affect transfusion requirements [

4]. In contrast, other studies have suggested that advanced age and higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores may necessitate higher transfusion thresholds, indicating a more cautious approach [

6].

Moreover, it has been proposed that patients with cirrhosis are more likely to require early transfusion due to factors such as decreased coagulation factors related to impaired liver function or variceal bleeding resulting from portal hypertension, both of which can lead to massive bleeding and increased mortality [

14]. This variability in findings indicates that the relationship between comorbidities and transfusion requirements is not entirely clear, emphasizing the importance of individualized patient assessment. In our cohort, the lack of a significant association between comorbid conditions and early transfusion decisions suggests that clinical judgment primarily relies on acute clinical parameters and hemoglobin levels rather than underlying chronic diseases.

When evaluating the laboratory values, we observed that Hb and Htc levels were lower in patients receiving RBCS transfusion in the ED compared to those transfused in other units. This finding is expected, as restrictive transfusion strategies commonly used in GI bleeding recommend transfusion when Hb levels fall below 7 g/dL [

15,

16]. The lower Hb levels observed in the ED group are consistent with this guideline, indicating that our findings align with the current literature. In the literature, studies have reported that the BUN/creatinine ratio can be used as a potential biomarker to determine the localization and severity of GI bleeding. For instance, a study by Calim et al. (2025) demonstrated that patients with a BUN/creatinine ratio greater than 23.3 had higher rates of RBCS transfusion, endoscopic intervention, and mortality [

17]. However, that study included both outpatient and inpatient cases. In contrast, our study exclusively analyzed hospitalized patients who received transfusion, which may explain why no significant differences were observed in BUN, creatinine, platelet, INR, and albumin levels between the groups.

Our study demonstrated that patients who received RBCS transfusion in the ED had a shorter length of hospital stay compared to those transfused in other inpatient units. This finding aligns with the concept that early transfusion in the ED may promote rapid hemodynamic stabilization and facilitate timely discharge. Similar results have been reported by Maher et al. (2020) and Chang et al. (2025), who found that empiric transfusion practices in the ED, driven by acute clinical parameters, can reduce the length of stay by addressing critical needs promptly, thereby optimizing hospital resource utilization [

18,

19].

Regarding mortality, our study found no statistically significant difference between the ED and inpatient transfusion groups. This is consistent with the findings of Carson et al. (2023), who noted that while early transfusion may stabilize patients initially, it does not necessarily correlate with a reduction in in-hospital mortality [

7]. This outcome may be related to the fact that once the acute phase is managed, subsequent care in inpatient units does not substantially impact survival outcomes.

Our findings also resonate with the guideline recommendations by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (2022), which emphasize that the decision for transfusion should not solely be based on hemoglobin levels but also consider the overall clinical status and comorbidities of the patient [

20]. This approach helps prevent unnecessary transfusions and reduces the risk of transfusion-related complications while maintaining effective clinical outcomes .

Our study identified five independent predictors of mortality among the six variables included in the logistic regression model: age, albumin levels, length of hospital stay, Hb levels, and creatinine levels. Among these, age and albumin made the most substantial contribution to the model, while the unit where RBCS transfusion was performed had the least impact. This finding is consistent with the results of Chen et al. (2021), who demonstrated that low albumin levels were independently associated with increased mortality in patients presenting with acute UGIB, highlighting the prognostic value of albumin in critically ill patients [

21].

Hb level also emerged as a significant predictor of mortality in our study. This aligns with the findings of Custovic et al. (2020) and Morarasu et al. (2023), who emphasized that hemoglobin is a key variable in risk scoring systems like GBS and AIMS65, widely used for predicting outcomes in GI bleeding [

22,

23]. Lower Hb levels at admission have been linked to higher mortality risk, as also demonstrated by Aljarad et al. (2021), who found a moderate inverse relationship between hemoglobin levels and mortality among hospitalized GI bleeding patients [

24].

Additionally, creatinine levels were found to independently predict mortality in our cohort. This is in line with the study by Dajti et al. (2025), who reported that elevated creatinine was a significant predictor of in-hospital mortality among patients with lower GI bleeding [

25]. Renal dysfunction in the context of acute bleeding may reflect systemic hypoperfusion and multi-organ failure, which could explain its association with poorer outcomes.

We also observed that prolonged hospital stay was correlated with increased mortality, likely reflecting the higher burden of comorbidities and advanced age in patients requiring extended care. Similar observations have been reported by Belete et al. (2024), who found that older patients with comorbid conditions tend to have longer hospital stays and higher mortality, underlining the importance of early risk stratification and multidisciplinary management [

26].

Although our study did not find a significant difference in mortality between ED and inpatient transfusion groups, this may be due to the heterogeneous nature of patients’ initial presentations and the variability in clinical stability upon admission. Previous studies have often categorized transfusion timing within the first 4 hours as early and beyond that as delayed, with the latter associated with higher mortality rates [

27]. However, our analysis did not specifically stratify timing, which could have influenced the outcomes.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design may introduce selection and information bias, as data collection was based on medical records, which may contain inaccuracies. Additionally, the study was conducted at a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Furthermore, the lack of precise data on transfusion timing and the absence of stratification based on the severity of bleeding and comorbid conditions may have influenced the results. To validate our findings, prospective, multicenter studies with more comprehensive data collection are warranted.

6. Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that early RBCS transfusion performed in the ED is associated with a shorter length of hospital stay compared to transfusion in inpatient units. However, this difference did not result in a significant reduction in mortality. This suggests that the primary advantage of ED-based transfusion may be related to more efficient patient management rather than improved survival outcomes. Logistic regression analysis identified age, albumin levels, length of hospital stay, Hb levels, and creatinine levels as independent predictors of mortality, highlighting the importance of early risk stratification. These findings underscore the need for individualized transfusion strategies that consider both clinical status and patient-specific factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and H.Y.; Methodology, M.T. and H.Y.; Software, M.K. and A.H.; Validation, M.K. and E.S.; Formal analysis, M.K. and M.U.; Investigation, M.T., H.Y., and A.Ç.; Resources, H.Y. and M.U.; Data curation, M.T., H.Y., M.K., and A.Ç.; Writing—Original draft preparation, M.T. and H.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.S. and A.H.; Visualization, M.K. and A.H.; Supervision, E.S. and M.K.; Project Administration, H.Y.; Funding Acquisition, M.T. and H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All authors declared that the research was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki “Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.” This study was approved by the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kütahya Health Sciences University (approval number: 2023/09-29, dated August 16, 2023). Additionally, necessary permissions were obtained from the Kütahya Provincial Health Directorate Scientific Research Evaluation Committee (approval number: 2024/9, dated January 31, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Because the study was based on medical record review and all individuals’ information were not appeared in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABC |

Age, Blood tests, and Comorbidities |

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| AIMS65 |

Albumin-International Normalized Ratio-Mental Status-Systolic Blood Pressure-65 |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BUN |

Blood Urea Nitrogen |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| CHF |

Congestive Heart Failure |

| CKD |

Chronic Kidney Disease |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| ES |

Erythrocyte Suspension |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| GIB |

Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

| GBS |

Glasgow-Blatchford Score |

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| Hct |

Hematocrit |

| HT |

Hypertension |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| INBS |

International Normalized Bleeding Score |

| INR |

International Normalized Ratio |

| MAP |

Mean Arterial Pressure |

| NV-AUGIB |

Non-Variceal Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| Plt |

Platelet |

| RBCS |

Red Blood Cell Suspension |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| UGIB |

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

| LGIB |

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Raţiu, I.; Lupuşoru, R.; Popescu, A.; et al. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: A comparison between variceal and nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e31543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Hirata, Y.; Yamada, A.; Koike, K. Initial management for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal, E.; Acar, Y.A. Features of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and factors affecting the re-bleeding risk. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022, 28, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerbage, A.; Nammour, T.; Tamim, H.; et al. Impact of blood transfusion on mortality and rebleeding in gastrointestinal bleeding: an 8-year cohort from a tertiary care center. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2024, 37, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, S.B.; Oakland, K.; Laine, L.; et al. ABC score: a new risk score that accurately predicts mortality in acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: an international multicentre study. Gut 2021, 70, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmo, R.; Soncini, M.; de Franchis, R.; GISED – Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell'Emorragia Digestiva. Patient's performance status should dictate transfusion strategy in nonvariceal acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NV-AUGIB): A prospective multicenter cohort study: Transfusion strategy in NV-AUGIB. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.L.; Stanworth, S.J.; Dennis, J.A.; et al. Transfusion thresholds for guiding red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 12, CD002042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkoğlu, S.; Tezel, O.; Büyükturan, G.; Başgöz, B.B. The efficacy and comparison of upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk scoring systems on predicting clinical outcomes among emergency unit patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Koo, Y.K.; Kim, S.; et al. Association of time to red blood cell transfusion on outcomes in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Med. 2025, 57, 2474858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kim, S.; Chung, H.S.; Park, I.; Kwon, S.S.; Myung, J. Predictive indicators for determining red blood cell transfusion strategies in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2023, 30, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpen-Palmer, J.; Stanley, A.J. Update on the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, F.; Cao, L.; Ren, X. , et al. Age and sex trend differences in hemoglobin levels in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Räsänen, J.; Ellam, S.; Hartikainen, J.; Juutilainen, A.; Halonen, J. Sex Differences in Red Blood Cell Transfusions and 30-Day Mortality in Cardiac Surgery: A Single Center Observational Study. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkun, A.N.; Almadi, M.; Kuipers, E.J. , et al. Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Guideline Recommendations From the International Consensus Group. Ann Intern Med. 2019, 171, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, L.; Barkun, A.N.; Saltzman, J.R.; Martel, M.; Leontiadis, G.I. ACG Clinical Guideline: Upper Gastrointestinal and Ulcer Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, C.A.; Razavi, S.A.; Roback, J.D.; Murphy, D.J. RBC Transfusion Strategies in the ICU: A Concise Review. Crit Care Med. 2019, 47, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calim, A. The role of BUN/creatinine ratio in determining the severity of gastrointestinal bleeding and bleeding localization. North Clin Istanb. 2025, 12, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, P.J.; Khan, S.; Karim, R.; Richardson, L.D. Determinants of empiric transfusion in gastrointestinal bleeding in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2020, 38, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Sitthinamsuwan, N.; Pungpipattrakul, N. , et al. Impact of duration to endoscopy in patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: propensity score matching analysis of real-world data from Thailand. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and management of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1151–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, H.; Wang, S. Prediction model of emergency mortality risk in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a retrospective study. PeerJ. 2021, 9, e11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Custovic, N.; Husic-Selimovic, A.; Srsen, N.; Prohic, D. Comparison of Glasgow-Blatchford Score and Rockall Score in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Med Arch. 2020, 74, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morarasu, B.C.; Sorodoc, V.; Haisan, A. , et al. Age, blood tests and comorbidities and AIMS65 risk scores outperform Glasgow-Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall score in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Clin Cases. 2023, 11, 4513–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljarad, Z.; Mobayed, B.B. The mortality rate among patients with acute upper GI bleeding (with/without EGD) at Aleppo University Hospital: A retrospective study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021, 71, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajti, E.; Frazzoni, L.; Castellet-Farrús, S. , et al. In-hospital mortality in patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding: development and validation of a prediction score. Endoscopy. 4 April 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, M.W.; Kebede, M.A.; Bedane, M.R. , et al. Factors associated with severity and length of hospital stay in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: insights from two Ethiopian hospitals. Int J Emerg Med. 2024, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasitvarakul, K.; Attanath, N.; Chang, A. Comparison of scoring systems for predicting clinical outcomes of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: A prospective cohort study. World J Surg. 2024, 48, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).