Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

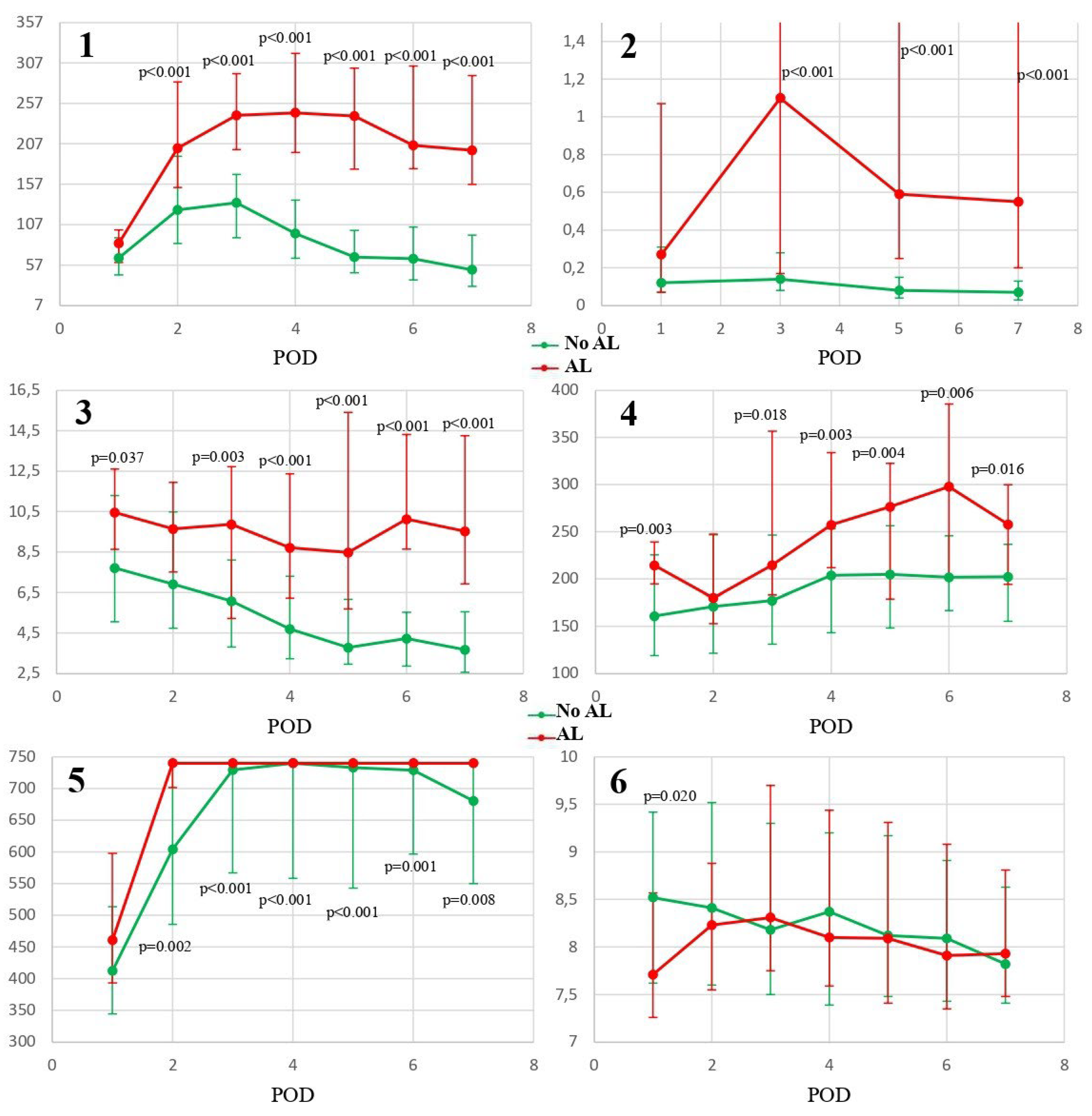

Background/Objectives: Anastomotic leakage (AL) is one of the most feared complications following gastrectomy, with a relatively high incidence rate. The aim of this study was to assess and compare the predictive ability of C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), fibrinogen and mean platelet volume (MPV) in the early diagnosis of post-gastrectomy AL. Methods: A prospective bicentric observational study was conducted including all patients undergoing elective gastrectomy between August 2018 and December 2022, assessing the performance of the noted biomarkers to predict the existence of AL within the first 7 postoperative days (POD). Results: A total of 107 patients were included for analysis. The incidence of AL was 20.56%, and the median day of diagnosis was on POD5 (interquartile range 4-6). CRP, PCT, NLR, PLR and fibrinogen showed significant association with the presence of AL (from POD2 for CRP and fibrinogen and from POD3 for PCT, NLR and PLR). CRP showed the better discrimination on POD4 (cut-off 181.4mg/L; NPV 99%; AUC 0.87, p<0.001); PCT demonstrated the better discrimination on POD7 (cut-off 0.13ng/mL; NPV 98%; AUC 0.84, p<0.001); NLR showed the better discrimination on POD6 (cut-off 6.77; NPV 95%; AUC 0.86, p<0.001); PLR achieved the higher discrimination on POD7 (AUC 0.71; 95%CI 0.58-0.82; cut-off 234; Se 93%; Sp 73%; PPV 47%; NPV 98%; p=0.002); fibrinogen showed the better discrimination on POD5 (AUC 0.74; 95%CI 0.66-0.8; cut-off 734.4; Se 95%; Sp 52%; PPV 35%; NPV 98%; p=0.003). In the comparison of predictive accuracy CPR, PCT and NLR were found superior among all other biomarkers. Conclusions: CRP, PCT and NLR are biomarkers with adequate predictive ability to clinically discard the presence of AL within the first postoperative week.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Endpoints

2.4. Data anal#ysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort characteris#tics

3.2. Dynamics of the Inflammatory Markers

3.3. Diagnostic Accuracy and Cutoffs

3.4. Comparison of Predictive Accuracy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lang, H.; Piso, P.; Stukenborg, C.; Raab, R.; Jähne, J. Management and results of proximal anastomotic leaks in a series of 1114 total gastrectomies for gastric carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2000, 26, 168–171. [CrossRef]

- Makuuchi, R.; Irino, T.; Tanizawa, Y.; Bando, E.; Kawamura, T.; Terashima, M. Esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg. Today 2018, 49, 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, M.; Tanizawa, Y.; Bando, E.; Kawamura, T.; Terashima, M. Poor Survival Rate in Patients with Postoperative Intra-Abdominal Infectious Complications Following Curative Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 20, 1575–1583. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, H.; Ichikura, T.; Ono, S.; Sugasawa, H.; Hiraki, S.; Sakamoto, N.; Yaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Hase, K. Impact of Postoperative Infection on Long-Term Survival After Potentially Curative Resection for Gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 16, 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Polish Gastric Cancer Study Group; Sierzega, M.; Kolodziejczyk, P.; Kulig, J. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival after total gastrectomy for carcinoma of the stomach. Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 1035–1042. [CrossRef]

- Roh, C.K.; Choi, S.; Seo, W.J.; Cho, M.; Kim, H.-I.; Lee, S.-K.; Lim, J.S.; Hyung, W.J. Incidence and treatment outcomes of leakage after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Experience of 14,075 patients from a large volume centre. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2021, 47, 2304–2312. [CrossRef]

- Cananzi, F.C.M.; Biondi, A.; Agnes, A.; Ruspi, L.; Sicoli, F.; De Pascale, S.; Fumagalli, U.R.; D’ugo, D.; Quagliuolo, V.; Persiani, R. Optimal Predictors of Postoperative Complications After Gastrectomy: Results from the Procalcitonin and C-reactive Protein for the Early Diagnosis of Anastomotic Leakage in Esophagogastric Surgery (PEDALES) Study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 478–488. [CrossRef]

- Shishido, Y.; Fujitani, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Hirao, M.; Tsujinaka, T.; Sekimoto, M. C-reactive protein on postoperative day 3 as a predictor of infectious complications following gastric cancer resection. Gastric Cancer 2015, 19, 293–301. [CrossRef]

- van Winsen, M.; McSorley, S.T.; McLeod, R.; MacDonald, A.; Forshaw, M.J.; Shaw, M.; Puxty, K. Postoperative C-reactive protein concentrations to predict infective complications following gastrectomy for cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 124, 1060–1069. [CrossRef]

- Chadi, S.A.; Fingerhut, A.; Berho, M.; DeMeester, S.R.; Fleshman, J.W.; Hyman, N.H.; Margolin, D.A.; Martz, J.E.; McLemore, E.C.; Molena, D.; et al. Emerging Trends in the Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Anastomotic Leakage. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 20, 2035–2051. [CrossRef]

- De Mooij, C.M.; Maassen van den Brink, M.; Merry, A.; Tweed, T.; Stoot, J. Systematic review of the role of biomarkers in predicting anastomotic leakage following gastroesophageal cancer surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

- Dripps RD. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology. 1963;24:111.

- Kim EY, Yim HW, Park CH, Song KY. C-reactive protein can be an early predictor of postoperative complications after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(1):445–54.

- Nam, J.H.; Noh, G.T.; Chung, S.S.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, R.-A. Validity of C-Reactive Protein as a Surrogate Marker for Infectious Complications After Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Surg. Infect. 2023, 24, 488–494. [CrossRef]

- Bona, D.; Danelli, P.; Sozzi, A.; Sanzi, M.; Cayre, L.; Lombardo, F.; Bonitta, G.; Cavalli, M.; Campanelli, G.; Aiolfi, A. C-reactive Protein and Procalcitonin Levels to Predict Anastomotic Leak After Colorectal Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 166–179. [CrossRef]

- Imai Y, Tanaka R, Honda K, Matsuo K, Taniguchi K, Asakuma M, et al. The usefulness of prepepsin in the diagnosis of postoperative complications after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):21289.

- Gordon, A.C.; Cross, A.J.; Foo, E.W.; Roberts, R.H. C-reactive protein is a useful negative predictor of anastomotic leak in oesophago-gastric resection. ANZ J. Surg. 2016, 88, 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Kano, K.; Tamagawa, H.; Sawazaki, S.; Ohshima, T.; Yukawa, N.; Rino, Y.; Masuda, M. [The Postoperative C-Reactive Protein Level Is an Early Predictor of Infectious Complications after Gastric Cancer Resection].. 2015, 42, 1256–8.

- Ji, L.; Wang, T.; Tian, L.; Gao, M. The early diagnostic value of C-reactive protein for anastomotic leakage post radical gastrectomy for esophagogastric junction carcinoma: A retrospective study of 97 patients. Int. J. Surg. 2016, 27, 182–186. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, F.; Hou, S.; Ying, X.; Huangfu, L.; Li, Z.; Ji, J. Clinical predictive efficacy of C-reactive protein for diagnosing infectious complications after gastric surgery. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hoeboer, S.H.; Groeneveld, A.B.J.; Engels, N.; van Genderen, M.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; van Bommel, J. Rising C-Reactive Protein and Procalcitonin Levels Precede Early Complications After Esophagectomy. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2015, 19, 613–624. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Ma, M.; Lin, C.; Luo, J.; Quan, H.; Tao, K.; Huang, G. Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin as an early predictor of infection after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A prospective bicenter cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 75, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Tao, K. Procalcitonin as an Early Predictor of Intra-abdominal Infections Following Gastric Cancer Resection. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 258, 352–361. [CrossRef]

- Mohri Y, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Ohi M, Yasuda H, Inoue Y, et al. Impact of preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and postoperative infectious complications on survival after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A single institutional cohort study. Med. 2016;95(11):1–7.

- Mungan İ, Bay Ç, Bekta Ş, Sar S, Yamanyar S, Çavu M. Does the preoperative platelet-to- lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to- lymphocyte ratio predict morbidity after gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):9.

- Clemente-Gutiérrez, U.; Sarre-Lazcano, C.; Casanueva-Pérez, E.; Sánchez-Morales, G.; Terán-Ellis, S.M.Y.; Contreras-Jiménez, E.; Santes, O.; Alfaro-Goldaracena, A.; Cortés, R.; Medina-Franco, H. Usefulness of inflammatory markers in detecting esophagojejunostomy leakage. Rev. De Gastroenterol. De Mex. 2021, 86, 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Çetin, D.A.; Gündeş, E.; Çiyiltepe, H.; Aday, U.; Uzun, O.; Değer, K.C.; Duman, M. Risk factors and laboratory markers used to predict leakage in esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage after total gastrectomy. Turk. J. Surg. 2019, 35, 6–12. [CrossRef]

- Giaccaglia, V.; Salvi, P.F.; Antonelli, M.S.; Nigri, G.R.; Corcione, F.; Pirozzi, F.; de Manzini, N.; Casagranda, B.; Balducci, G.; Ziparo, V. Procalcitonin reveals early dehiscence in colorectal surgery: the PREDICS study. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 219, e8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; Rong, H.; Guo, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G. Serum procalcitonin levels distinguish Gram-negative bacterial sepsis from Gram-positive bacterial and fungal sepsis. J. Res. Med Sci. 2016, 21, 39. [CrossRef]

- Nora, D.; Salluh, J.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Póvoa, P. Biomarker-guided antibiotic therapy—strengths and limitations. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 208–208. [CrossRef]

- Póvoa, P.; Salluh, J.I.F. Biomarker-guided antibiotic therapy in adult critically ill patients: a critical review. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2012, 2, 32–32. [CrossRef]

- D’Ugo D, Agnes A, Grieco M, Biondi A, Persiani R. Global updates in the treatment of gastric cancer: a systematic review. Part 2: perioperative management, multimodal therapies, new technologies, standardization of the surgical treatment and educational aspects. Updat Surg. 2020;72(2):355–78.

- Parikh, R.; Mathai, A.; Parikh, S.; Sekhar, G.C.; Thomas, R. Understanding and using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 56, 45–50. [CrossRef]

| Overall (n=107) |

Patients without AL (n=85) |

Patients with AL (n=22) |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73 (64-79) | 73 (64-78) | 74 (68-80) | 0.20 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 50 (46.73%) | 37 (43.53%) | 13 (59.09%) | 0.19 | |

| Female | 57 (53.27%) | 48 (56.47%) | 9 (40.91%) | ||

| ASA score | |||||

| I | 6 (5.61%) | 6 (7.06%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.64 | |

| II | 46 (38.32%) | 32 (37.65%) | 9 (40.91%) | ||

| III | 36 (52.34%) | 44 (51.76%) | 12 (54.55%) | ||

| IV | 4 (6.54%) | 3 (3.53%) | 1 (4.55%) | ||

| Histology | |||||

| ADC | 96 (89.72%) | 76 (89.41%) | 30 (90.91%) | 0.83 | |

| GIST | 3 (2.80%) | 2 (2.35%) | 1 (4.55%) | ||

| PUD | 2 (1.87%) | 2 (2.35%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Other | 6 (5.61%) | 5 (5.88%) | 1 (4.55%) | ||

| NAT | 41 (38.32%) | 37 (43.53%) | 4 (18.18%) | 0.029 | |

| Type of gastrectomy | |||||

| Total | 44 (41.12%) | 31 (36.47%) | 13 (59.09%) | 0.28 | |

| Near-total (95%) | 13 (12.15%) | 11 (12.94%) | 2 (9.09%) | ||

| Subtotal | 49 (45.79%) | 42 (49.41%) | 7 (31.82%) | ||

| Proximal | 1 (0.93%) | 1 (1.18%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Surgical approach | |||||

| Open | 28 (26.17%) | 22 (25.88%) | 6 (27.27%) | 0.002 | |

| Laparoscopic | 72 (67.29%) | 61 (71.76%) | 11 (50.00%) | ||

| LCO | 7 (6.54%) | 2 (2.35%) | 5 (22.73%) | ||

| Procedure duration (min) | 290 (246-334) | 280 (240-324) | 320 (263-370) | 0.010 | |

| Other complications | 66 (61.68%) | 49 (57.65%) | 17 (77.27%) | 0.091 | |

| Clavien-Dindo score | |||||

| I | 19 (26.03%) | 19 (22.35%) | 0 (0.00%) | <0.001* | |

| II | 33 (45.21%) | 26 (30.59%) | 7 (31.82%) | ||

| III | 8 (10.96%) | 2 (2.35%) | 6 (27.27%) | ||

| IV | 4 (5.48%) | 2 (2.35%) | 2 (9.09%) | ||

| V | 9 (12.33%) | 2 (2.35%) | 7 (31.82%) | ||

| Postoperative stay (days) | 10 (7-17) | 9 (7-12) | 25 (17-39) | <0.001* | |

| Mortality | 9 (8.41%) | 2 (2.35%) | 7 (31.82%) | <0.001* | |

| CPR | PCT | NLR | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p | Coefficient | 95% CI | p | Coefficient | 95% CI | p | ||

| POD1 | BL | BL | NA | BL | BL | NA | BL | BL | NA | |

| POD2 | 77.60 | 63.34–91.87 | <0.001* | NA | NA | NA | 0.49 | (-)1.46–1.56 | 0.949 | |

| POD3 | 86.94 | 72.72–101.17 | <0.001* | 0.22 | (-)1.70–2.15 | 0.821 | -1.61 | (-)3.11–(-)0.10 | 0.036* | |

| POD4 | 61.65 | 47.31–74.99 | <0.001* | NA | NA | NA | -2.82 | (-)4.34–(-)1.30 | <0.001* | |

| POD5 | 37.38 | 22.92–51.85 | <0.001* | 1.45 | (-)0.49–3.39 | 0.145 | -3.52 | (-)5.04–(-)1.99 | <0.001* | |

| POD6 | 31.44 | 16.13–46.75 | <0.001* | NA | NA | NA | -3.41 | (-)5.02–(-)1.79 | <0.001* | |

| POD7 | 21.21 | 6.68–36.73 | 0.007* | 0.46 | (-)1.61–2.53 | 0.663 | -3.31 | (-)4.96–(-)1.67 | <0.001* | |

| AL | 115.37 | 92.87–137.88 | <0.001* | 3.43 | 1.72 – 5.15 | <0.001* | 4.27 | 2.43–6.12 | <0.001* | |

| PLR | Fibrinogen | MPV | ||||||||

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p | Coefficient | 95% CI | p | Coefficient | 95% CI | p | ||

| POD1 | BL | BL | NA | BL | BL | NA | BL | BL | NA | |

| POD2 | 19.16 | (-)17.43–55.75 | 0.305 | 167.04 | 145.956– 188.12 | <0.001* | -0.66 | (-)1.44–0.13 | 0.101 | |

| POD3 | 8.65 | (-)27.84–45.14 | 0.642 | 219.77 | 198.62–240.91 | <0.001* | -0.62 | (-)1.40–0.16 | 0.120 | |

| POD4 | 16.74 | (-)20.05–53.53 | 0.372 | 222.94 | 201.73–244.15 | <0.001* | -0.86 | (-)1.65–(-)0.07 | 0.033* | |

| POD5 | 14.15 | (-)22.85–51.14 | 0.454 | 215.92 | 194.57–237.27 | <0.001* | -0.85 | (-)1.66–(-)0.06 | 0.035* | |

| POD6 | 24.12 | (-)15.11–63.34 | 0.228 | 214.39 | 191.82-236.97 | <0.001* | -0.88 | (-)1.72–(-)0.04 | 0.040* | |

| POD7 | 1.91 | (-)37.92–41.73 | 0.925 | 181.87 | 158.96–204.77 | <0.001* | -0.97 | (-)1.82-(-)0.12 | 0.026* | |

| AL | 60.49 | 12.07–108.91 | 0.014* | 80.94 | 35.12–126.76 | 0.001* | -0.35 | (-)1.17–(+)0.46 | 0.398 | |

| CRP | PCT | NLR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| POD1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1,039 (0,974-1,109) | 0,244 |

| POD2 | 1,011 (1,005-1,017) | <0,001* | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| POD3 | 1,018 (1,010-1,026) | <0,001* | 1,451 (1,030-2,043) | 0,033* | 1,076 (1,000-1,157) | 0,05* |

| POD4 | 1,025 (1,015-1,035) | <0,001* | NA | NA | 1,161 (1,049-1,285) | 0,004* |

| POD5 | 1,025 (1,015-1,035) | <0,001* | 6,831 (1,865-25,023) | 0,004* | 1,333 (1,160-1,533) | <0,001* |

| POD6 | 1,032 (1,018-1,047) | <0,001* | NA | NA | 1,681 (1,326-2,130) | <0,001* |

| POD7 | 1,030 (1,016-1,045) | <0,001* | 18,83 (2,45-144,51) | 0,005* | 1,585 (1,259-1,994) | <0,001* |

| PLR | Fibrinogen | MPV | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| POD1 | 1,002 (0,999-1,005) | 0,229 | NA | NA | 0,589 (0,384-0,904) | 0,015* |

| POD2 | NA | NA | 1,007 (1,002-1,012) | 0,006* | NA | NA |

| POD3 | 1,005 (1,001-1,009) | 0,008* | 1,015 (1,003-1,028) | 0,018* | NA | NA |

| POD4 | 1,007 (1,002-1,012) | 0,007* | 1,020 (1,001-1,039) | 0,036* | NA | NA |

| POD5 | 1,007 (1,002-1,012) | 0,006* | 1,019 (1,002-1,035) | 0,027* | NA | NA |

| POD6 | 1,006 (1,001-1,010) | 0,014* | 1,013 (1,001-1,025) | 0,029* | NA | NA |

| POD7 | 1,005 (0,999-1,010) | 0,06 | 1,002 (0,998-1,006) | 0,286 | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).