1. Introduction

Antibiotic compounds, originating from a plethora of microorganisms, have long been in existence before their therapeutic potential in combating bacterial diseases was fully realized by humans. These antibiotics encompass various types tailored to address infections caused by bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms. The discovery of antibiotics hinges upon understanding their chemical structures and activity spectra [

1]. Antibiotics are classified based on the scope of their action, falling into narrow, broad, or extended categories. Narrow-spectrum agents primarily target gram-positive bacteria. Whereas, broad-spectrum antibiotics combat gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria alike, however, extended-spectrum antibiotics are modified chemically and exert influence over additional bacterial types, typically favoring gram-negative strains [

2]. Each antibiotic manifests distinct mechanisms of action, e.g., the retardation of protein, cell wall, and nucleic acid formation in bacterial cells. The most prevalent antibiotic classes include penicillins, macrolides, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones [

3].

The problem of antimicrobial resistance has emerged as an important event with the widespread use of antibiotics in agriculture and clinical settings, as it poses a substantial threat to public hygiene in the 21st century. According to the latest Lancet report, antimicrobial resistance in 2019 contributed to approximately 4.95 million deaths, with 1.27 million deaths directly linked to this resistance [

4]. Without effective control measures, it is projected that this figure could rise to as high as 10 million by the year 2050. Recent studies highlighted certain environmental sources containing clinically resistant pathogens with Antibiotic Resistant Genes (ARGs) [

5]. While numerous genes can impart resistance, assessing the comparative health risks associated with ARGs proves complicated. Factors like abundance, potential for lateral transmission, and the capacity of ARGs to be activated in infectious agents all contribute significantly [

6]. Consequently, ARGs are increasingly recognized as a new form of environmental pollutant and have garnered significant attention as a global research focus [

7]. Antibiotics as a global health concern were declared by many health organizations in the world such as Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) [

8].

WHO has declared that the rising antimicrobial resistance among bacterial species presents a global concern, representing a significant public health issue. The global concern regarding antibiotic resistance needs more attention from scientists [

9]. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria is a natural process. In addition to mutation in several genes residing on bacterial chromosomes, there are genetic exchange mechanisms between microorganisms that constitute an important role in antimicrobial resistance. One of the most important genetic materials is a plasmid which has antibiotic resistance genes. Transmission of these resistance elements is induced by antibiotics and the selective pressure due to these antimicrobial substances is the primary reason for resistance [

10,

11].

The advent of antibacterial resistance has gained more interest in the form of phage therapy, in which phages can be used as an option for replacement in antibiotic resistance cases. On the other hand, phages play a core role in antibiotic resistance genes dissemination in our environment for all kinds of organisms including human beings. In the current review, we emphasize the ARG’s dissemination through bacteriophages in our universe.

1.1. Bacteriophages: Abundance in the Environment

Bacteriophages, as prevalent as their bacterial counterparts and often surpassing them in abundance, exert significant control over bacterial populations. They achieve this through mechanisms such as lysis, leading to the transformation of bacterial immunity systems, facilitating lateral gene transfer, and modulating the metabolic system of the host via the transfer of supplementary metabolic genes. At their core, bacteriophages are essentially nucleic acids encapsulated within a protein capsid. Despite their simplistic structure, these tiny biological entities exert considerable influence in the microbial realm, serving as expert manipulators. The abundant presence of phages underscores their pivotal role in regulating bacteria and shaping the ecology of various environments through the lysis of bacterial hosts, just as they can influence the cycling of organic matter on a large scale by releasing organic material through bacterial cell lysis alongside influencing microbial diversity by selecting for microorganisms resistant to their attacks, thereby altering the proportions of bacterial strains within communities [

12].

Bacteriophages are abundantly distributed throughout various habitats on Earth. With an estimated 10

31 phage particles globally, they outnumber bacterial populations by a factor of ten, making them the biological entities having the most prevalence in the biosphere [

13]. In the human body, which hosts over 10

12 bacteria, particularly in the gut, phages are also ubiquitous, surpassing bacterial numbers by at least tenfold [

14]. They play crucial roles in shaping bacterial communities across different bodily sites, like the urinary tract, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and oral cavity [

15]. In ocean environments, studies indicate that phages reign as rich biological entities, with an estimated 4 × 10

30 viruses present, indicating that viruses outnumber bacteria and archaea by 15-fold [

16]. Similarly, in various soil types worldwide, phage densities range around 10

10 per gram of dry soil, with minimal variance across different soil types [

17]. However, the virus-to-bacterium (VBR) ratio varies to a great extent among soil types, with the counts of viruses being 10- to 100-fold lesser than bacteria in soils of agricultural and desert lands, but in Antarctic soil, the counts of viruses are 1000-fold than bacteria [

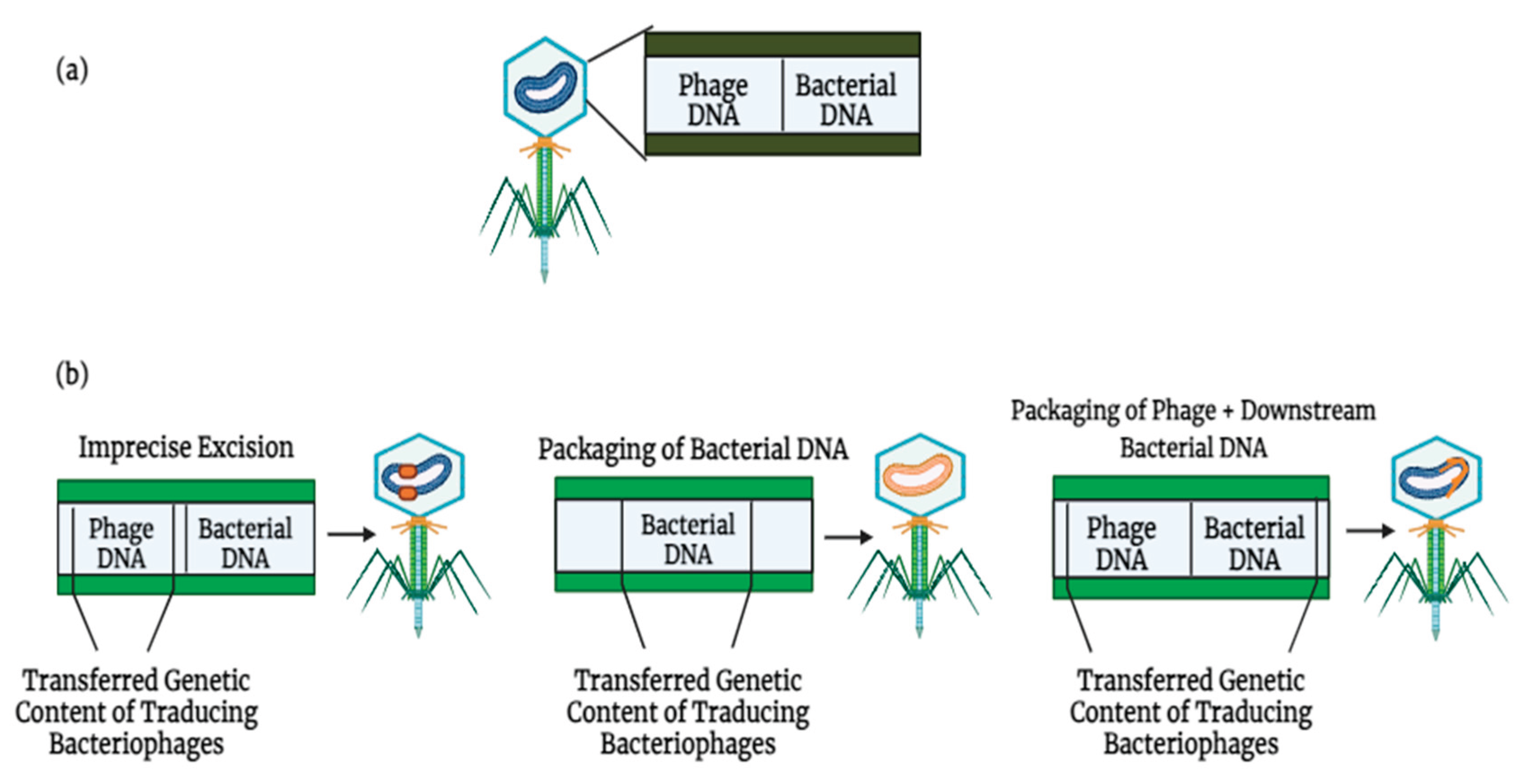

13]. Due to the ample and persistent nature of phages in our environment, the phages help to disseminate the genes responsible for antibiotic resistance among the bacterial cells even in different biome or taxon groups as shown in (

Figure 1).

1.2. Bacteriophages: A Vehicle for Resistance Genes

The viruses that infect and replicate specifically within bacterial cells are called phages or bacteriophages. They vary widely in size, morphology, and genomic structure, but all possess a DNA/RNA genome, encapsulated in a phage-encoded protein coat called capsid. Despite diverse appearances, phages are non-motile and rely on Brownian motion for movement [

18]. While resistance against antibiotics by microbes is innate, the extensive utilization of antimicrobials has extensively led to this mechanism’s prevalence among disease-causing bacteria in animals and humans alike. Many pathogenic species related to human health harbor resistance genes within their chromosomes as an integral component. Various studies indicate that the mechanisms underlying antibiotic resistance observed in clinical settings closely mirror those found in environmental contexts. The extensive mingling of bacteria residing in the environment with bacteria arising from sources related to humans creates ecological conditions that lay the foundation for the advent of antibiotic-resistant strains [

19,

20]. ARGs can be obtained and disseminated among bacteria via mobile genetic elements, like conjugative plasmids, insertion sequences, integrons, transposons, and bacteriophages [

21]. Our review underscores the notable function of bacteriophages in facilitating the transfer of resistance gene elements from environmental reservoirs to pathogens associated with human health, rendering antibiotics ineffective. To mitigate the health issues related to common people associated with antibiotic resistance, it is important to understand the sources and procedures behind the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

1.3. Antibiotic Resistance Genes Transmission Mechanisms

ARGs can transfer between or among bacterial strains through vertical and horizontal gene transfer mechanisms [

22]. The transfer of genes is done through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), including ARGs, from one bacterial strain to another, across different bacterial species or within the same species. In addition to ARGs, other genetic elements such as those encoding virulence factors and metabolic traits can also be transferred through HGT. According to estimates, 25% of the total genes of

Escherichia coli originate from other bacterial species as a result of the HGT mechanism [

23]. Lateral gene transfer mechanisms primarily encompass transformation, transduction, and conjugation [

24].

1.3.1. Conjugation

The process of conjugation occurs by the transferring of genetic material either through plasmid DNA or direct cell-to-cell contact from one bacterium to the other. This process is dependent on the exchange of MGEs like plasmids and integrating and conjugation elements (ICEs) by a pore or pilus formation between closely situated bacterial strains [

25]. The transfer of ARGs through plasmid-mediated conjugation poses a serious risk to the health of humans because of the transmission of drug resistance. Research has shown that mechanisms for transmitting drug resistance via ICEs may be observed in Gram-positive bacteria, like

Streptococcus species [

26].

1.3.2. Transformation

Transformation is the process by which recipient bacteria absorb external DNA, primarily plasmid DNA or fragmented DNA produced during bacterial lysis or active secretion [

27]. This acquired DNA is then integrated into the genomes of the recipient bacteria, enabling them to acquire new traits [

28]. Studies have demonstrated that under natural conditions,

Escherichia coli can transform by absorbing plasmid DNA, suggesting that

E. coli can absorb DNA in the digestive tract. It is acknowledged that one possible mechanism influencing the spread of genes resistant to antibiotics is transformation [

21].

1.3.3. Transduction

To facilitate the acquisition of new features, transduction uses bacteriophages to function as carriers to transmit chromosomal and extrachromosomal DNA from donor bacteria to recipient bacteria. Phages can accompany antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) within the same environmental niche and bacterial populations, implicitly implying their potential part in the dissemination of genes resistant to drugs [

29]. Methicillin-resistant strains of

Staphylococcus aureus are more prone to resistance transduction, whereby they obtain the

mecA gene from other bacterial species by phage-mediated transduction. The occurrence of transduction in nature is unpredictable, highlighting its profound significance in the transmission of drug resistance, extending beyond conventional understanding [

30].

2. Resistance Genes Transmission Mechanisms in Bacteriophages

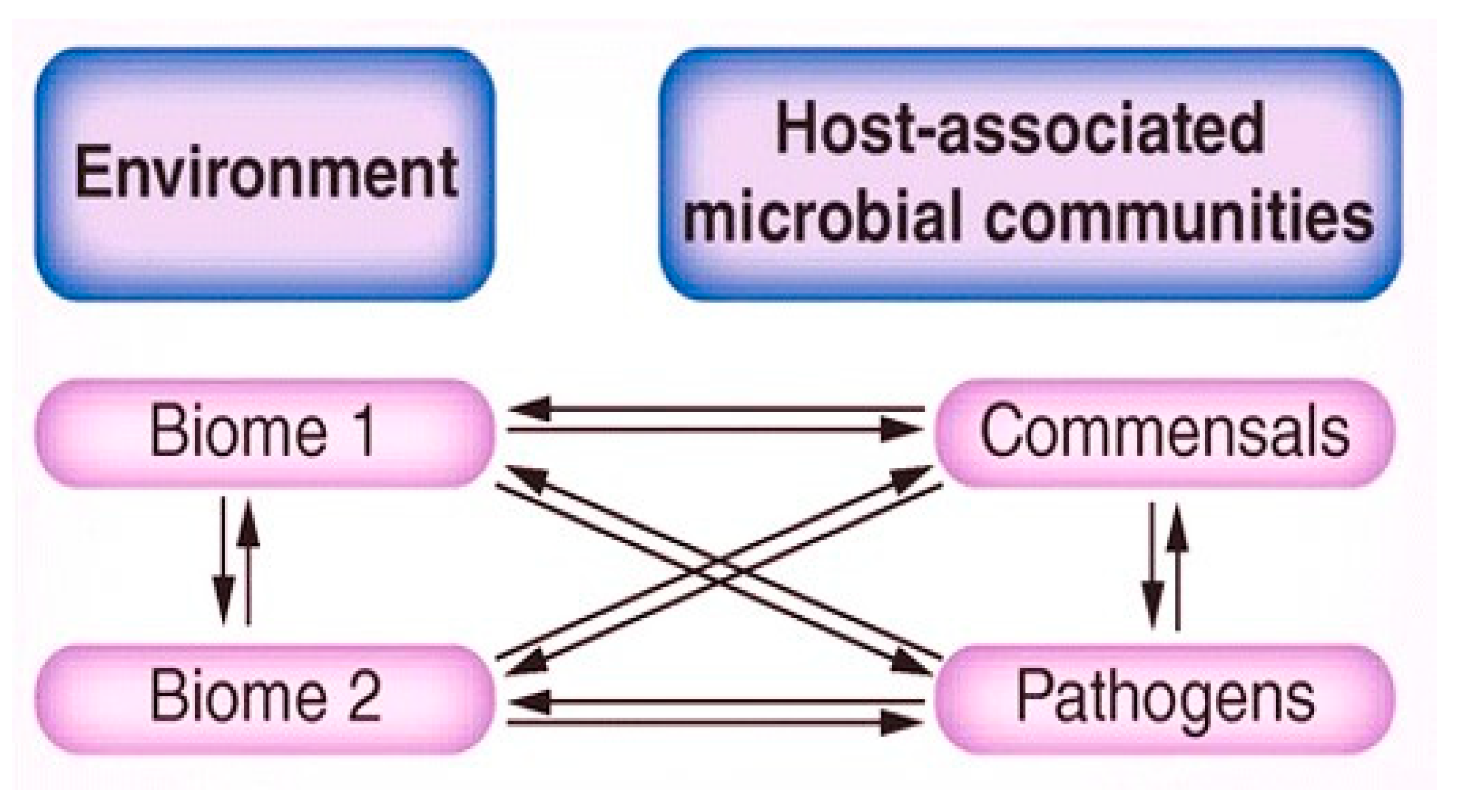

Bacteriophages facilitate genetic exchange through generalized and specialized transduction, enabling generic material transfer from donor to receiving cells (

Figure 2). They exhibit high host specificity and typically infect only a single bacterial species or specific strains. Upon latching onto a host, phages adapt to go through either a lytic or lysogenic cycle of replication. The lytic cycle is characterized by the injection of viral genome in the host cell by the phage, this genome later on hijacks the ribosomes of the host to produce viral proteins. This then leads to the rapid synthesis of new phages and this later on leads to the eventual lysis of the host cell, releasing progeny phages to infect other cells. The lysogenic cycle is characterized by the integration of the phage genome into the bacterial chromosome which replicates alongside the host genome without causing immediate cell death. These integrated phage genomes, known as prophages, can revert to the lytic cycle under certain conditions, leading to host cell lysis [

31].

As per the latest study, through HGT, mobile genetic elements (MGEs) facilitate the transfer of resistance genes to non-resistant bacterial species, facilitating the accumulation and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes in both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. It has been reported that phage particles can transduce genes (imipenem, aztreonam, and ceftazidime) in

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

33], in

Staphylococcus epidermidis (methicillin) [

34],

S. aureus (tetracycline), and can also disseminate genes from

Salmonella enterica serovar

Typhimurium DT10 [

35]. The resistance genes for beta-lactamases encoded on bacterial chromosomes and plasmid can also be disseminated in gram-negative bacteria which are clinically important [

36].

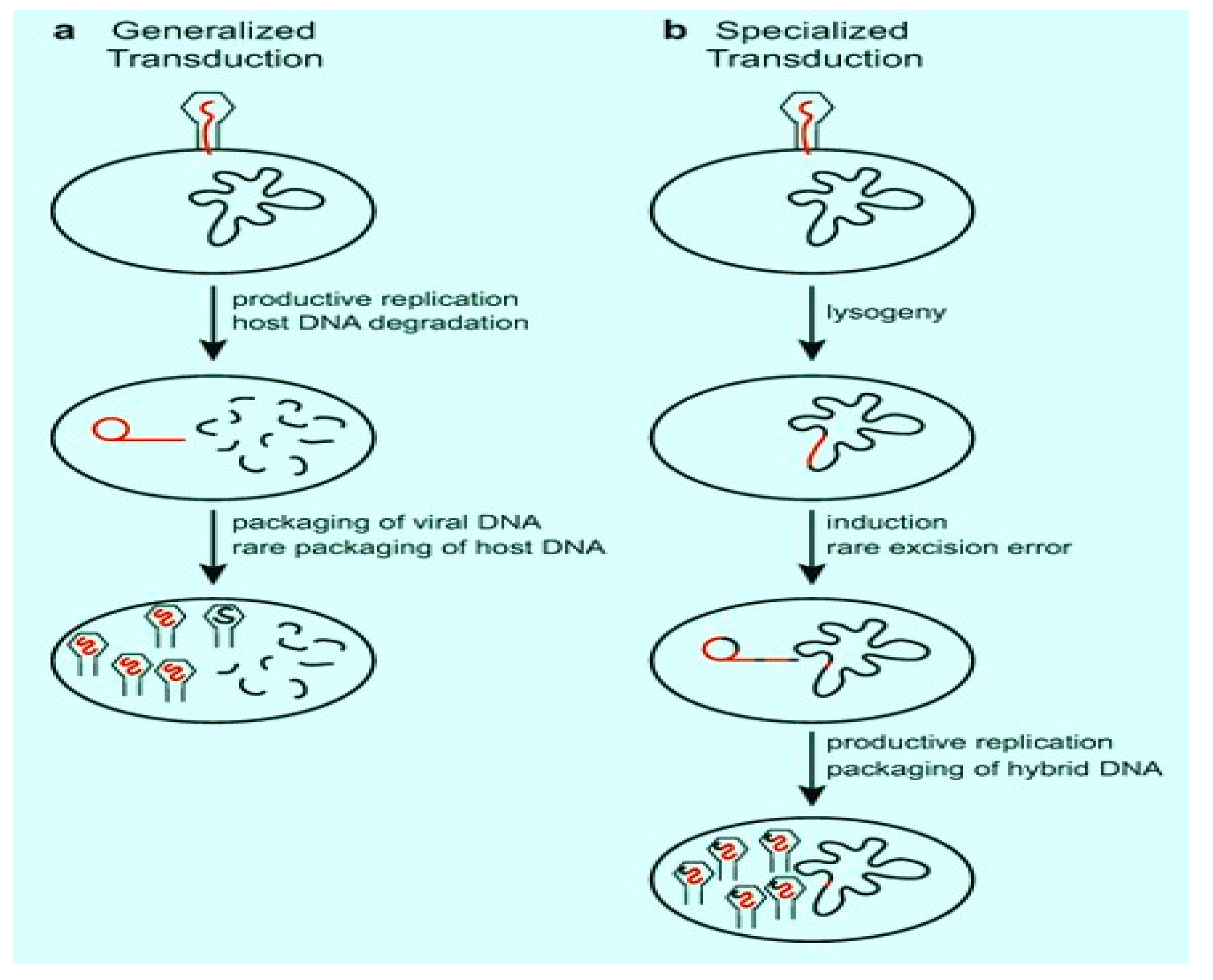

Phages Dissemination of ARGs via Transduction

The dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) can be achieved by both lytic and lysogenic phage cycles, with three distinct methods of phage-mediated transduction identified (

Figure 3). Firstly, specialized transduction is facilitated by temperate phages, which unintentionally mobilize adjacent host genes during imprecise excision from the bacterial genome. Secondly, generalized transduction occurs when bacterial DNA, rather than phage DNA, is encapsulated within the phage head. This ability to package sizable DNA fragments enables transduction to indirectly facilitate the transfer of ARGs associated with other mobile genetic elements (MGEs). For instance, Zhang et al, demonstrated that T

4-like phages erroneously incorporated plasmid-borne ARGs through generalized transduction [

37]. Transduction can also mediate the exchange of ARGs between different bacterial species. Studies have revealed that polyvalent phages can transfer ARGs between various

Enterococcus and

Staphylococcus species under controlled laboratory conditions [

38].

Lastly, it has been a recently identified mechanism of phage-mediated transduction is lateral transduction. In this process, newly formed phage capsids efficiently package primarily bacterial DNA downstream of the phage insertion site. Lateral transduction stands out as the most potent mode of phage-mediated DNA transfer, capable of transporting several hundred kilobases and a broad section of the bacterial genome [

39]. Unlike generalized transduction, which utilizes

ppac sites, lateral transduction employs embedded

pac sites for DNA packaging. Recently, Humphrey et al. (2021) conducted research utilizing

S. aureus and

Salmonella spp. as reference organisms [

40], demonstrating that chromosomally encoded bacterial genes could be transferred at rates up to 1000-fold higher through lateral transduction compared to generalized transduction [

41].

Figure 3.

Lytic and lysogenic phages play a role in the development of bacterial antimicrobial resistance through various means:

(a) Bacteriophages can harbor mobile genetic elements (MGEs) and facilitate the movement of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs).

(b) There exist three primary mechanisms by which phages facilitate the spread of genetic material [

41].

Figure 3.

Lytic and lysogenic phages play a role in the development of bacterial antimicrobial resistance through various means:

(a) Bacteriophages can harbor mobile genetic elements (MGEs) and facilitate the movement of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs).

(b) There exist three primary mechanisms by which phages facilitate the spread of genetic material [

41].

Moreover, transduction frequencies of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) vary among different bacterial species and are influenced by various factors such as the efficiency of phage infection, the presence of suitable phage receptors on bacterial cell surfaces, and the mechanisms of gene transfer involved in transduction (

Table 1). Some bacterial species may exhibit higher transduction frequencies for certain ARGs due to specific interactions between phages and host bacteria. Additionally, the genetic context of ARGs, such as their location within mobile genetic elements like plasmids or transposons, can affect their transduction rates. Understanding the transduction frequencies of different ARGs by various bacterial species is essential for elucidating the dynamics of antibiotic resistance dissemination in microbial communities and developing strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance.

3. Bacterial Genes and ARGs in Viral Communities

Using outdated techniques in virology and bacteriophage studies has hindered the ability to culture phages within natural viral communities. Not being able to cultivate bacteriophages, various challenges have been encountered in assessing the characteristics of viral communities, such as their variety and the function of HGT in innate conditions. Metagenomic studies of viral communities in the human intestinal tract and wastewater plant-activated dirt deposits have confirmed the presence of genes for antibiotic resistance, including those encoding antibiotic efflux pumps, lipoproteins, TetC protein, streptogramin acetyltransferases, bleomycin, and β-lactamases within phage particles [

48]. Analysis of sputum viromes from cystic fibrosis patients has revealed a significant abundance of genes related to antimicrobial resistance compared to non-cystic fibrosis cases. Specifically, 66 efflux pump genes, nine β-lactamase genes, and fifteen fluoroquinolone resistance genes have been identified. Phylogenetic studies have indicated that these resistance genes originate from different sources within the bacteriophage community of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis [

49].

Recently in a few years, the main and powerful tools of genomic analysis have provided some knowledge to cover the different aspects of viral pollution. However, through metagenomics analysis, we gained much more information about the viral genomic materials that make up the viral populations found in the natural environment’s biomass [

50]. Metagenomics DNA can be sequenced through different sequencing techniques including Whole genome sequencing (WGS), which is better than the culture-dependent method. Viral metagenomics was first conducted in 2002, but before this, the PCR technique used to amplify the specific genes has made this possible to check the abundance of genes in the viral community, which is non-culturable. For instance, it was reported that bacteriophages infecting

E. coli O157: H7 in wastewater reservoirs contained the gene for the Shiga toxin [

51]. Similarly, viral communities present in activated plant sludge liquor contain bacteriophages that harbor sequences of 16S rRNA from various bacterial species. Furthermore, viral communities in raw municipal wastewater were found to contain sequences for blaOX A-2, blaPSE-1, or blaPSE-4, as well as blaPSE-type genes [

52]. These findings collectively suggest that bacteriophages serve as reserves for ARGs in various environmental settings.

ARGs by Bacteriophages

Lysogenic bacteriophages, commonly found in clinical samples and natural environments, play a significant part in the transduction of ARGs, thereby facilitating the spread of antibiotic resistance. For instance, in

Streptococcus pyogenes, tetracycline resistance genes, along with genes conferring resistance to antibiotics such as clindamycin, lincomycin, chloramphenicol, and macrolides have been transduced by bacteriophages. Additionally, erythromycin resistance genes have been induced in

S. pyogenes transductants, making them more resistant to elevated erythromycin concentrations [

53]. Additionally, in

S. pyogenes, a chimeric genetic element consisting of a transposon inserted into a prophage is linked to

mefA gene, which codes for a macrolide efflux protein [

54]. A study carried out by Mazaheri and his coworkers reported that tetracycline-resistant genes were transduced from

E. gallinarum to

Enterococcus faecalis and gentamicin gene was transduced from

Enterococcus faecalis to

Enterococcus faecium and same gene was transduced from

Enterococcus faecium to

Enterococcus casseliflavus [

55].

Table 2 displays the sources of antibiotics found in bacteriophage genomes.

4. Conclusion/Future Perspective

In conclusion, antibiotic-resistant microorganisms and ARGs are prevalent in our surroundings, indicating the likelihood of environmental sources contributing to resistance genes in human-associated microbial communities. Metagenomic sequencing analyses have revealed shared nucleotide sequences of MGEs between human pathogens and soil bacteria, underscoring the function of HGT mechanisms in their dissemination. Phages found naturally worldwide, serve as vehicles for ARG transfer, supplementing the traditional understanding of plasmid-mediated conjugation in HGT. Understanding and characterizing resistomes in natural and anthropogenic environments, including wastewater treatment plants contaminated with veterinary medicine, is crucial. Identifying specific biomes and bacteriophages involved in transferring ARGs among the infectious agents of humans and animals is essential for targeted interventions. Additionally, advancements in gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas offer opportunities for bioengineering phages to create broad-spectrum activities, potentially enhancing treatment efficacy. The convergence of antibiotics and bacteriophages represents an unexplored frontier in ARG research, warranting further investigation. Additional research endeavors are required to thoroughly examine the spread and emergence of ARGs, given their implications for public health. It is essential to investigate the impact of these contacts on the expansion of antibiotic tolerance and resistance.

Author Contributions

Shahid Sher: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Husnain Ahmad Khan: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Dilara Abbas Bukhari: Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Abdul Rehman: Writing - review & editing, Resources, Supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| ARG |

Antibiotic resistance genes |

| HGT |

Horizontal gene transfer |

| MGEs |

Mobile genetic elements |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| CDC |

Center For Disease Control |

| VBR |

Virus-to-bacterium |

| VLPs |

Virus-like particles |

References

- Kalyani, A.; Lakshmi, M.M.; Ahalya, N.; Anusha, P.; Seema, S.; Maneesha, T. Classification Of Different Antibiotics And Their Adverse Effects And Uses From Origin To Present. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 2, 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawa, E.M.; Fadel, M.; Al-Rabia, M.W.; Behairy, A.; Nouh, N.A.; Abdo, M.; Olga, R.; Fericean, L.; Atwa, A.M.; El-Nablaway, M. Antibiotic action and resistance: updated review of mechanisms, spread, influencing factors, and alternative approaches for combating resistance. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 14, 1305294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, G.; Saigal, S.; Elongavan, A. Action and resistance mechanisms of antibiotics: A guide for clinicians. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology 2017, 33, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, S.; Richards, G.P.; Parveen, S.; Williams, H.N. Characterization of Antibiotic Resistance in Shewanella Species: An Emerging Pathogen in Clinical and Environmental Settings. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Xu, N.; Lu, T.; Hong, W.; Penuelas, J.; Gillings, M.; Wang, M.; Gao, W. Assessment of global health risk of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature communications 2022, 13, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, T.; Gao, M.; Wang, X. Bacteriophages: Underestimated vehicles of antibiotic resistance genes in the soil. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 936267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coque, T.M.; Cantón, R.; Pérez-Cobas, A.E.; Fernández-de-Bobadilla, M.D.; Baquero, F. Antimicrobial resistance in the global health network: known unknowns and challenges for efficient responses in the 21st century. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A. Antimicrobial resistance: a growing serious threat for global public health. in Healthcare. 2023. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

- Munita, J.M.; Arias, C.A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Microbiology spectrum 2016, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, H.W.; Gillings, M.R. Gene flow, mobile genetic elements and the recruitment of antibiotic resistance genes into Gram-negative pathogens. FEMS microbiology reviews 2011, 35, 790–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puxty, R.J.; Millard, A.D. Functional ecology of bacteriophages in the environment. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2023, 71, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinovic, S.; Wassef, F.; Knowler, S.A.; Rice, D.T.; Stanton, C.R.; Rose, J.; Tucci, J.; Nittami, T.; Vinh, A.; Drummond, G.R. Bacteriophages in natural and artificial environments. Pathogens 2019, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasner, M.E. Finding enzymes in the gut metagenome. Science 2017, 355, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S.; Baker, K.; Padman, B.S.; Patwa, R.; Dunstan, R.A.; Weston, T.A.; Schlosser, K.; Bailey, B.; Lithgow, T.; Lazarou, M. Bacteriophage transcytosis provides a mechanism to cross epithelial cell layers. MBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naureen, Z.; Dautaj, A.; Anpilogov, K.; Camilleri, G.; Dhuli, K.; Tanzi, B.; Maltese, P.E.; Cristofoli, F.; De Antoni, L.; Beccari, T. Bacteriophages presence in nature and their role in the natural selection of bacterial populations. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, e2020024. [Google Scholar]

- Florent, P.; Cauchie, H.-M.; Herold, M.; Jacquet, S.; Ogorzaly, L. Soil ph, calcium content and bacteria as major factors responsible for the distribution of the known fraction of the DNA bacteriophage populations in soils of Luxembourg. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P.; Aiewsakun, P. Virus classification–where do you draw the line? Archives of virology 2018, 163, 2037–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcazar, J.L. Bacteriophages as vehicles for antibiotic resistance genes in the environment. PLoS pathogens 2014, 10, e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, S.; Sultan, S.; Rehman, A. Characterization of multiple metal resistant Bacillus licheniformis and its potential use in arsenic contaminated industrial wastewater. Applied Water Science 2021, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Kwong, S.M.; Firth, N.; Jensen, S.O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clinical microbiology reviews 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qiu, Y.; Song, Y.; Lin, H.; Yin, H. Dissecting horizontal and vertical gene transfer of antibiotic resistance plasmid in bacterial community using microfluidics. Environment International 2019, 131, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Chen, H.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Liang, W. The spread of antibiotic resistance genes in vivo model. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 2022, 2022, 3348695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatkin, A.J.; Sysoeva, T.A.; You, L. Dissecting the effects of antibiotics on horizontal gene transfer: Analysis suggests a critical role of selection dynamics. Bioessays 2016, 38, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, M.; Li, L.; Qi, J. The prevalence of colistin resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from food animals in China: coexistence of mcr-1 and blaNDM with low fitness cost. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2018, 51, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, B.A.; Kumar, A.; Castillo-Ramírez, S. Genomic basis of antibiotic resistance and virulence in Acinetobacter. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Henderson, I.R.; Guo, J. Artificial sweeteners stimulate horizontal transfer of extracellular antibiotic resistance genes through natural transformation. The ISME Journal 2022, 16, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.; Buckling, A.; Harms, K.; Johnsen, P.J.; Vos, M. Antimicrobial resistance acquisition via natural transformation: context is everything. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2021, 64, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, E.; Rall, B.C.; Chatzinotas, A.; Brose, U.; Rosenbaum, B. Phage strategies facilitate bacterial coexistence under environmental variability. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaber, J.; Penadés, J.R.; Ingmer, H. Transfer of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Trends in microbiology 2017, 25, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, L.; Porter, L. Bacteriophages. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022.

- Schneider, C.L. Bacteriophage-mediated horizontal gene transfer: transduction. Bacteriophages: biology, technology, therapy 2021, 151-192.

- Wood, S.J.; Kuzel, T.M.; Shafikhani, S.H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: infections, animal modeling, and therapeutics. Cells 2023, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fišarová, L.; Botka, T.; Du, X.; Mašlaňová, I.; Bárdy, P.; Pantůček, R.; Benešík, M.; Roudnický, P.; Winstel, V.; Larsen, J. Staphylococcus epidermidis phages transduce antimicrobial resistance plasmids and mobilize chromosomal islands. Msphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosini, S.M.; Bond, R.; McCarthy, A.J.; Feudi, C.; Schwarz, S.; Lindsay, J.A.; Loeffler, A. Genes on the move: in vitro transduction of antimicrobial resistance genes between human and canine staphylococcal pathogens. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.I.; Aqib, A.I.; Seleem, M.N.; Shabbir, M.A.; Hao, H.; Iqbal, Z.; Kulyar, M.F.-e.-A.; Zaheer, T.; Li, K. Genetic basis of molecular mechanisms in β-lactam resistant gram-negative bacteria. Microbial pathogenesis 2021, 158, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, X.; Shen, S.; Shi, M.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y. Effects of the newly isolated T4-like phage on transmission of plasmid-borne antibiotic resistance genes via generalized transduction. Viruses 2021, 13, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, M.; Mašlaňová, I.; Indráková, A.; Šiborová, M.; Mikulášek, K.; Bendíčková, K.; Plevka, P.; Vrbovská, V.; Zdráhal, Z.; Doškař, J. Staphylococcus sciuri bacteriophages double-convert for staphylokinase and phospholipase, mediate interspecies plasmid transduction, and package mecA gene. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 46319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Quiles-Puchalt, N.; Chiang, Y.N.; Bacigalupe, R.; Fillol-Salom, A.; Chee, M.S.J.; Fitzgerald, J.R.; Penadés, J.R. Genome hypermobility by lateral transduction. Science 2018, 362, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, S.; Fillol-Salom, A.; Quiles-Puchalt, N.; Ibarra-Chávez, R.; Haag, A.F.; Chen, J.; Penadés, J.R. Bacterial chromosomal mobility via lateral transduction exceeds that of classical mobile genetic elements. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Dharmaraj, T.; Cai, P.C.; Burgener, E.B.; Haddock, N.L.; Spakowitz, A.J.; Bollyky, P.L. Bacteriophage and bacterial susceptibility, resistance, and tolerance to antibiotics. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.; Hussain, H.; Chang, B.J.; Emmett, W.; Riley, T.V.; Mullany, P. Phage ϕC2 mediates transduction of Tn 6215, encoding erythromycin resistance, between Clostridium difficile strains. MBio 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z. Distribution of acquired antibiotic resistance genes among Enterococcus spp. isolated from a hospital in Baotou, China. BMC research notes 2019, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavecchio, A.; Cadieux, B.; Lo, A.; Goodridge, L.D. Bacteriophages contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance genes among foodborne pathogens of the Enterobacteriaceae family–a review. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ge, Y.; Wang, N.; Shi, Y.; Guo, G.; Zou, Q.; Liu, Q. Identification and characterization of a novel major facilitator superfamily efflux pump, SA09310, mediating tetracycline resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2023, 67, e01696-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindolire, M.A.; Babalola, O.O.; Ateba, C.N. Detection of antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus from milk: A public health implication. International journal of environmental research and public health 2015, 12, 10254–10275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoir, V. Mechanisms of Streptococcus pyogenes antibiotic resistance. Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet]. 2nd edition, 2022.

- Mutuku, C.; Gazdag, Z.; Melegh, S. Occurrence of antibiotics and bacterial resistance genes in wastewater: resistance mechanisms and antimicrobial resistance control approaches. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2022, 38, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pailhoriès, H.; Herrmann, J.-L.; Velo-Suarez, L.; Lamoureux, C.; Beauruelle, C.; Burgel, P.-R.; Héry-Arnaud, G. Antibiotic resistance in chronic respiratory diseases: from susceptibility testing to the resistome. European Respiratory Review 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debroas, D.; Siguret, C. Viruses as key reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment. The ISME journal 2019, 13, 2856–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Haarmann, N.; Schwidder, M.; Muniesa, M.; Schmidt, H. Bacteriophages of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and their contribution to pathogenicity. Pathogens 2021, 10, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesté, E.; Blanch, A.R.; Muniesa, M.; García-Aljaro, C.; Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Martín-Díaz, J.; Pascual-Benito, M.; Jofre, J. Bacteriophages in sewage: abundance, roles, and applications. FEMS microbes 2022, 3, xtac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShan, W.M.; Nguyen, S.V. The bacteriophages of Streptococcus pyogenes. Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet], 2016.

- Giovanetti, E.; Brenciani, A.; Vecchi, M.; Manzin, A.; Varaldo, P.E. Prophage association of mef (A) elements encoding efflux-mediated erythromycin resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2005, 55, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri Nezhad Fard, R.; Barton, M.; Heuzenroeder, M. Bacteriophage-mediated transduction of antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Letters in applied microbiology 2011, 52, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer-Lluch, M.; Jofre, J.; Muniesa, M. antibiotic resistance genes in environmental bacteriophages.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).