Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genome

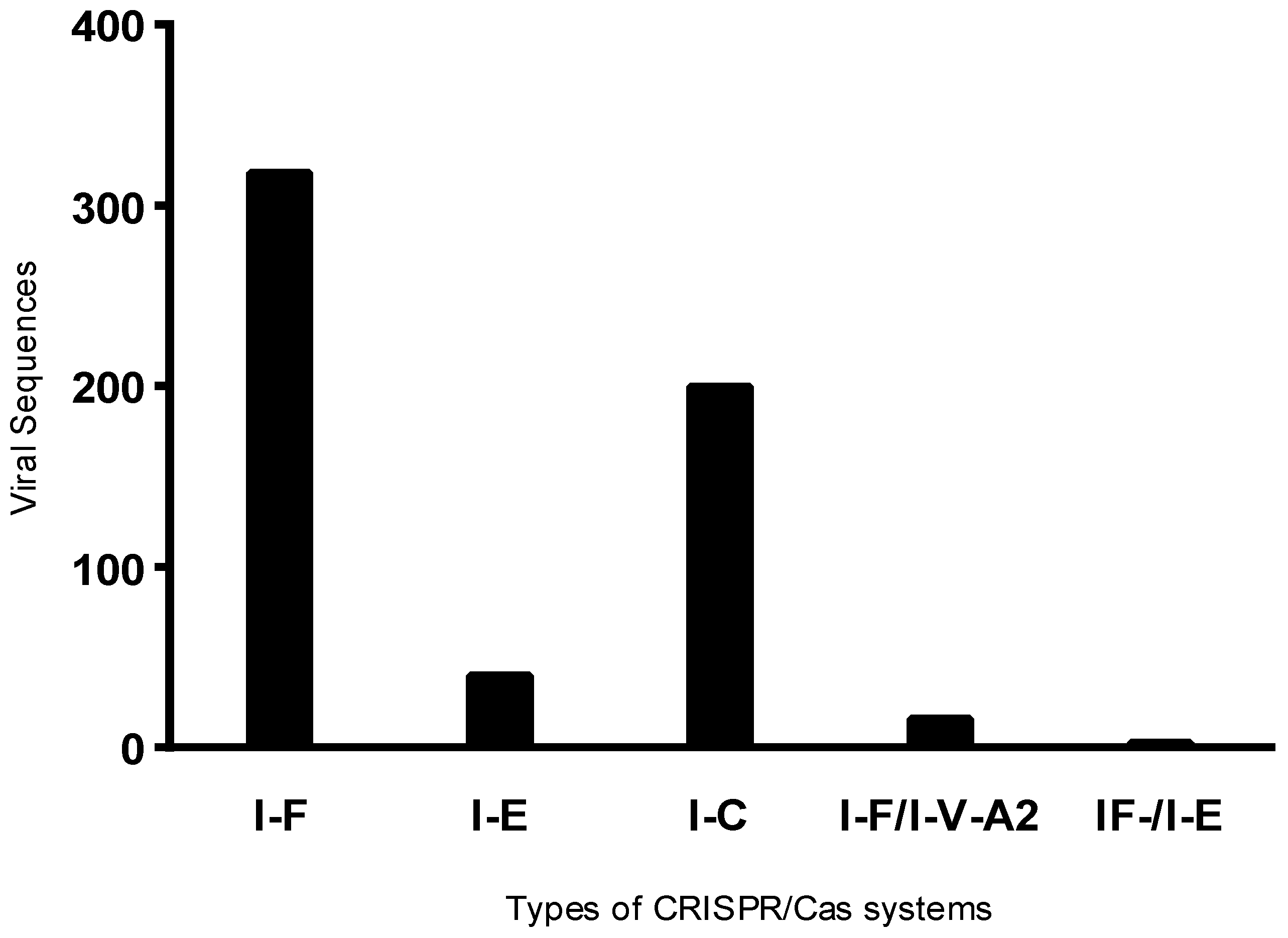

2.2. CRISPR System Identification

2.3. Prophage Identification

2.4. Prophage Distribution in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genomes

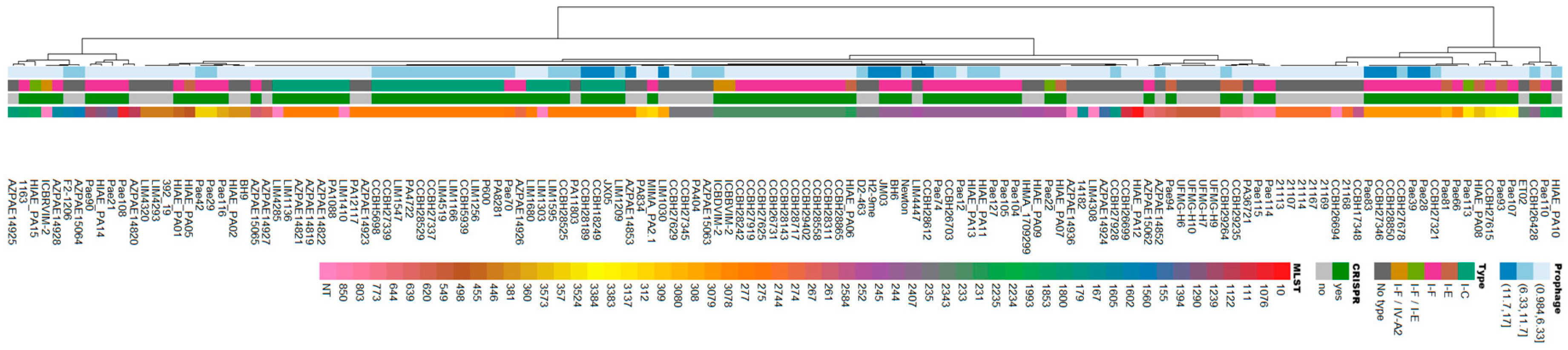

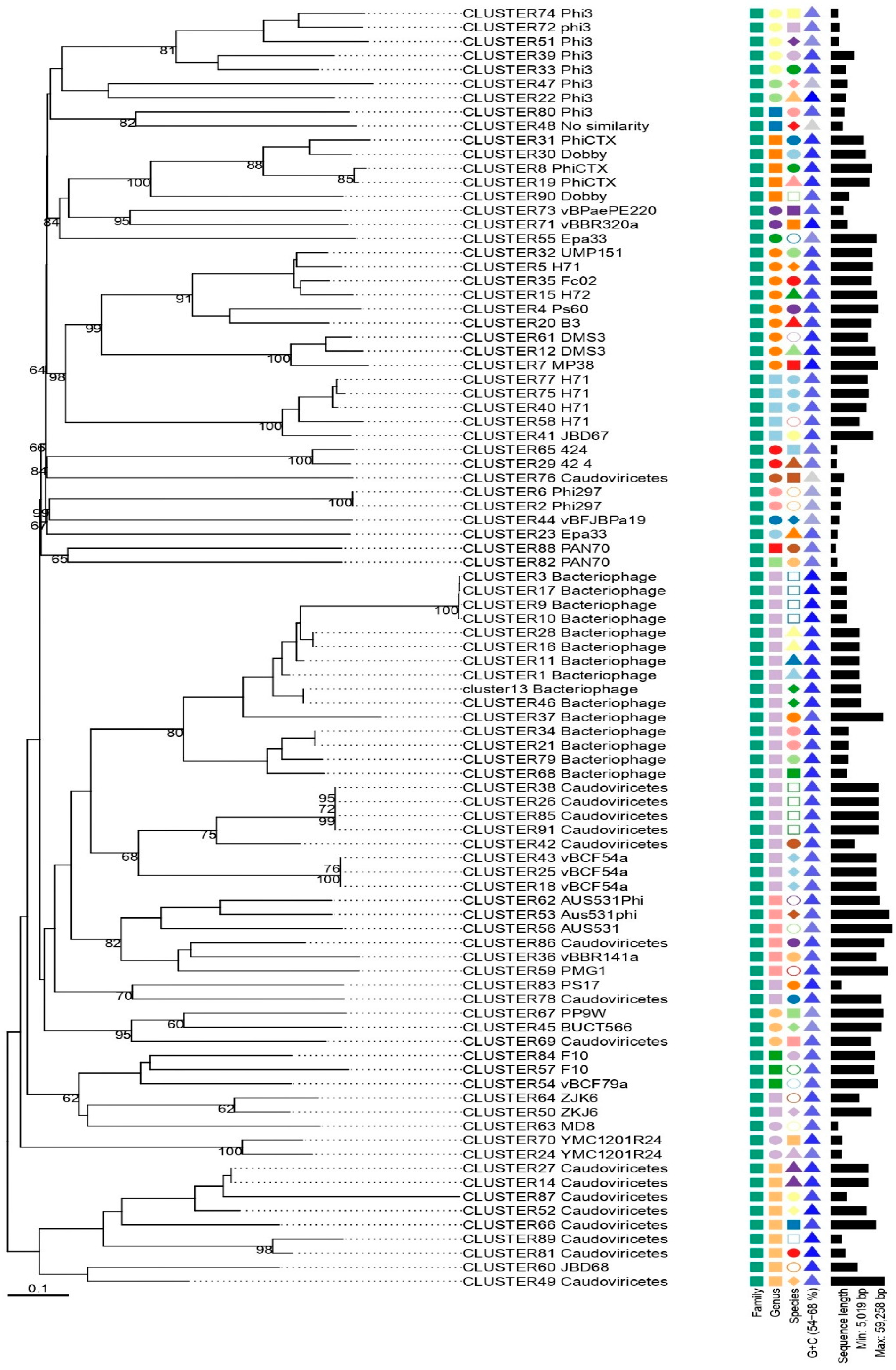

2.5. Clustering, Phylogeny and dendogram

2.6. Identification of Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors in Prophages

2.7. Prophage Life Cycle

2.8. Statistical Correlations

3. Results

3.1. In Silico Analysis Identifies Prophages in Brazilian Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

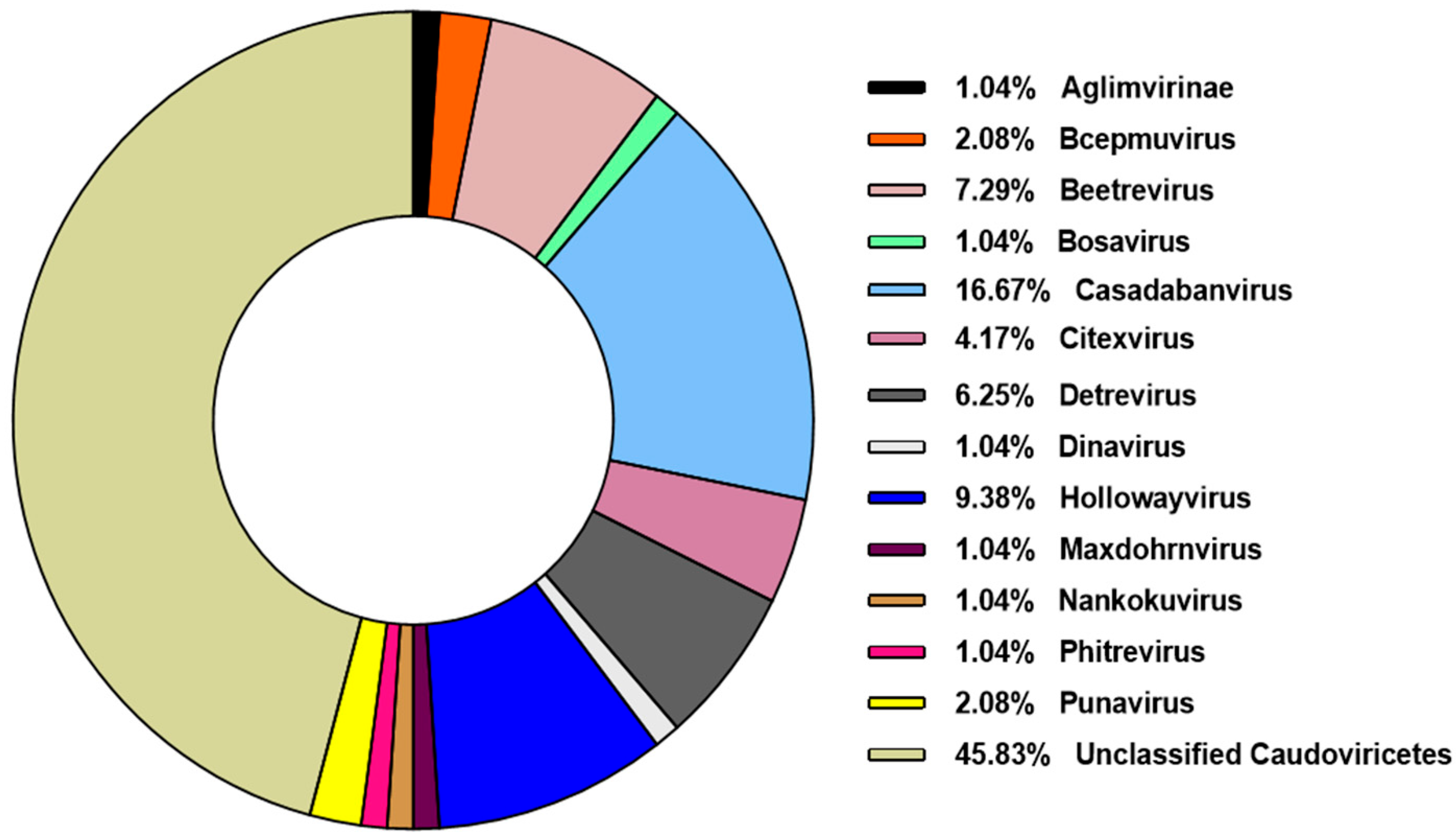

3.2. Caudoviricetes is the Most Commonly Identified Class of Prophages in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genomes

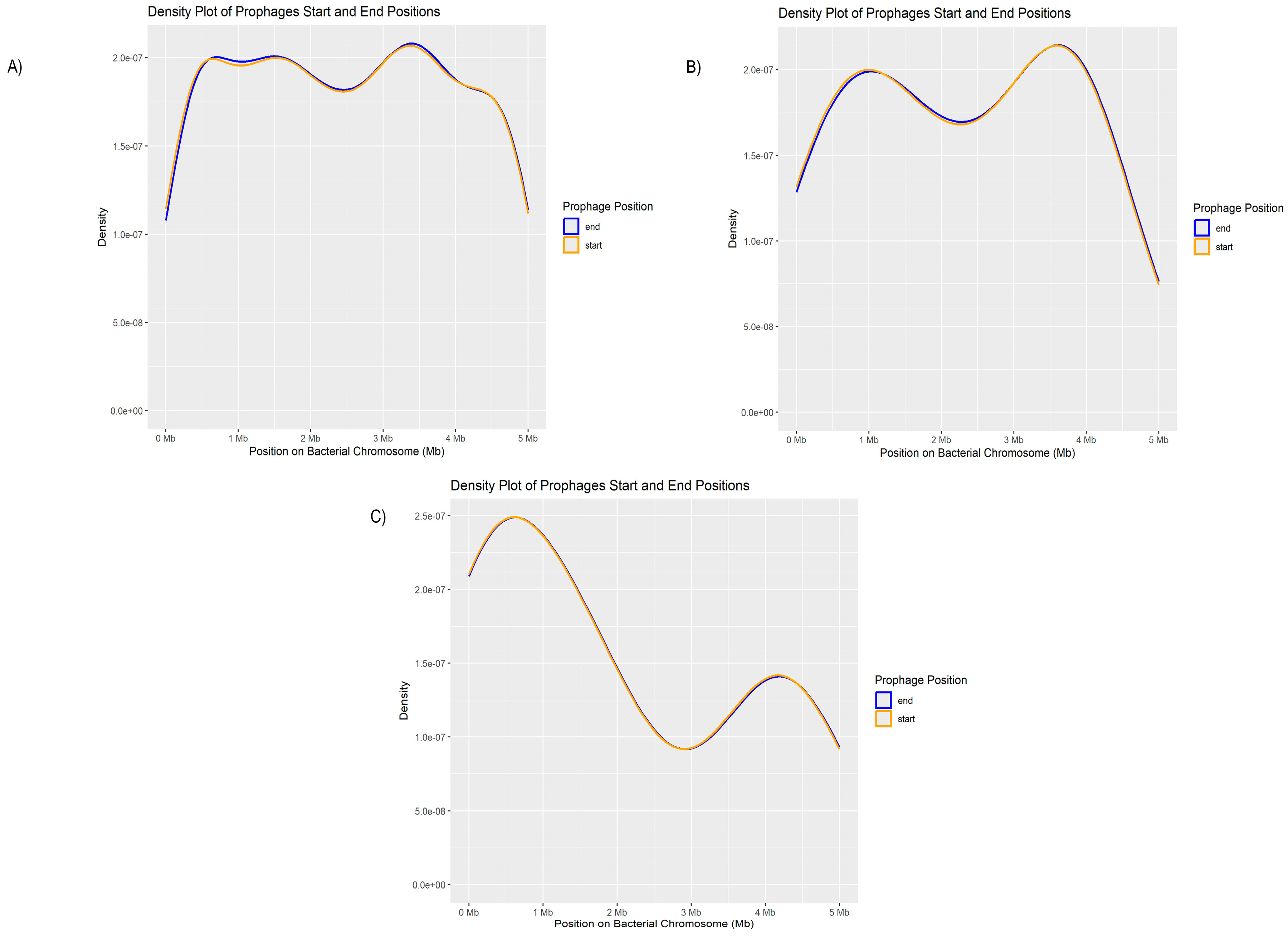

3.3. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Prophages Do Not Exhibit Unique Insertion Sites

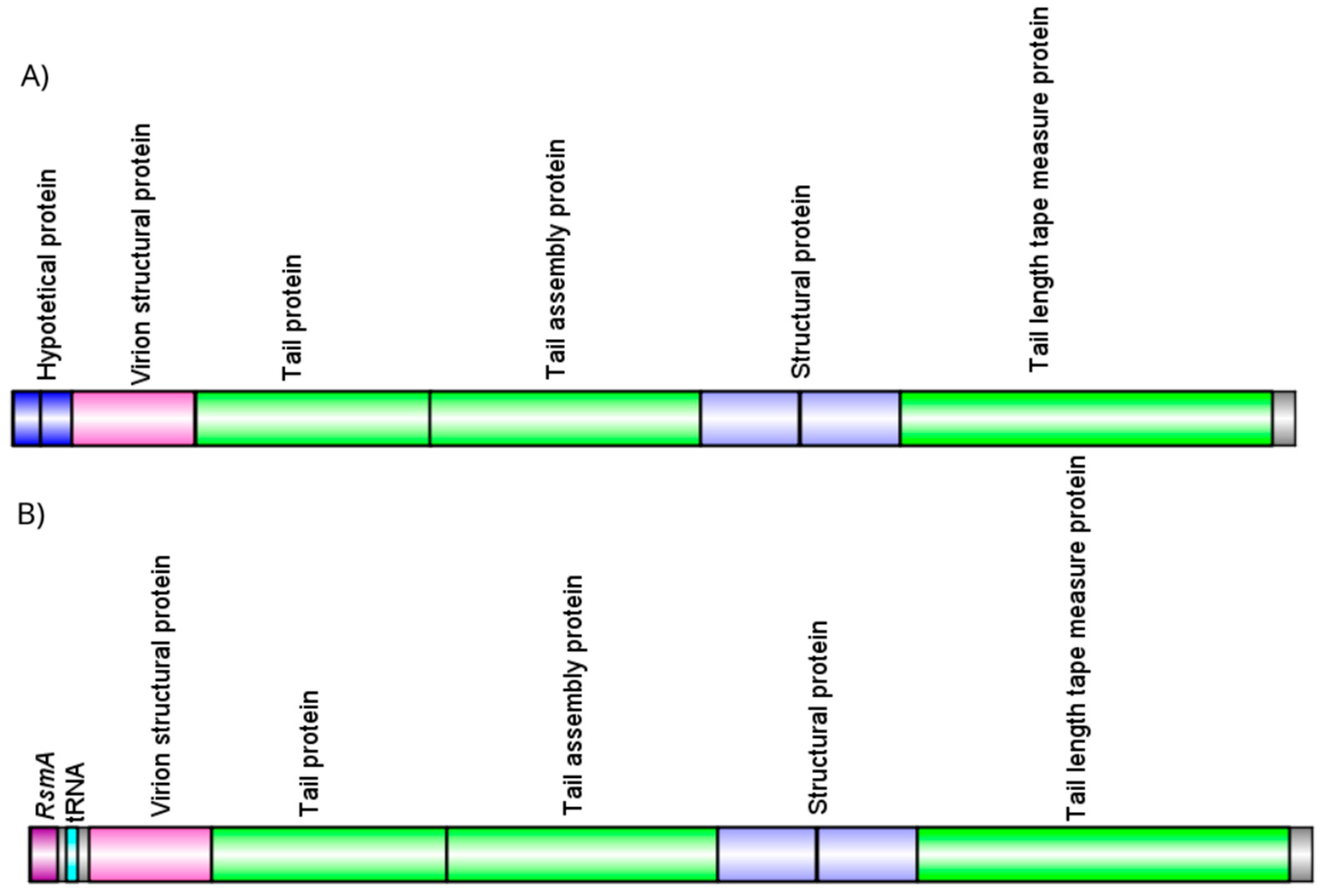

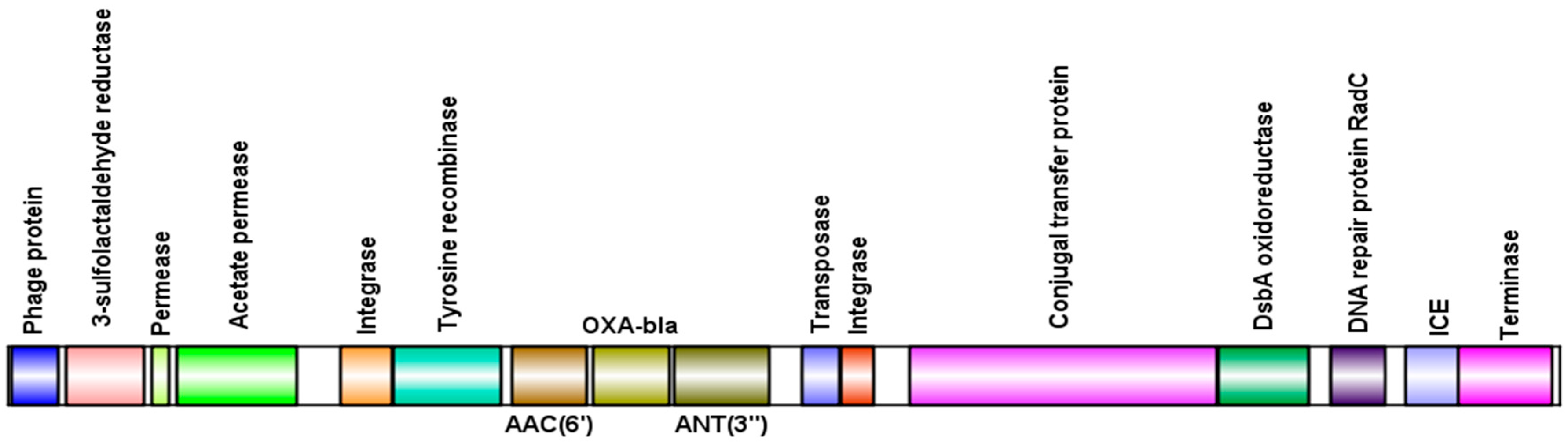

3.4. Presence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Viral sequences

3.5. The Lytic Cycle Is More Frequent in Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRISPR/CAS | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated genes |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ICEs | Integrative and Conjugative Elements |

| PAGIs | Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genomic Islands |

References

- Codjoe F, Donkor E. Carbapenem Resistance: A Review. Medical Sciences 2017;6:1. [CrossRef]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance, to Guide Research, Development, and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024.

- Qin S, Xiao W, Zhou C, Pu Q, Deng X, Lan L, Liang H, Song X, Wu M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:199. [CrossRef]

- Luong T, Salabarria A-C, Roach DR. Phage Therapy in the Resistance Era: Where Do We Stand and Where Are We Going? Clinical Therapeutics 2020;42:1659–80. [CrossRef]

- Davies EV, Winstanley C, Fothergill JL, James CE. The role of temperate bacteriophages in bacterial infection. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2016;363:fnw015. [CrossRef]

- Chevallereau A, Pons BJ, Van Houte S, Westra ER. Interactions between bacterial and phage communities in natural environments. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022;20:49–62. [CrossRef]

- Tsao Y-F, Taylor VL, Kala S, Bondy-Denomy J, Khan AN, Bona D, Cattoir V, Lory S, Davidson AR, Maxwell KL. Phage Morons Play an Important Role in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phenotypes. J Bacteriol 2018;200. [CrossRef]

- Bucher MJ, Czyż DM. Phage against the Machine: The SIE-ence of Superinfection Exclusion. Viruses 2024;16:1348. [CrossRef]

- Couvin D, Bernheim A, Toffano-Nioche C, Touchon M, Michalik J, Néron B, Rocha EPC, Vergnaud G, Gautheret D, Pourcel C. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of CRISRFinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Research 2018;46:W246–51. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed M, Casjens SR, Millard AD, Harrison C, Gannon L, Chattaway MA. Genomic analysis of Anderson typing phages of Salmonella Typhimrium: towards understanding the basis of bacteria-phage interaction. Sci Rep 2023;13:10484. [CrossRef]

- Luz ACDO, Da Silva JMA, Rezende AM, De Barros MPS, Leal-Balbino TC. Analysis of direct repeats and spacers of CRISPR/Cas systems type I-F in Brazilian clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Genet Genomics 2019;294:1095–105. [CrossRef]

- Xavier KVM, De Oliveira Luz AC, Silva-Junior JW, De Melo BST, De Aragão Batista MV, De Albuquerque Silva AM, De Queiroz Balbino V, Leal-Balbino TC. Molecular epidemiological study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from hospitals in Brazil by MLST and CRISPR/Cas system analysis. Mol Genet Genomics 2025;300:33. [CrossRef]

- Kieft K, Zhou Z, Anantharaman K. VIBRANT: automated recovery, annotation and curation of microbial viruses, and evaluation of viral community function from genomic sequences. Microbiome 2020;8:90. [CrossRef]

- Angiuoli SV, Salzberg SL. Mugsy: fast multiple alignment of closely related whole genomes. Bioinformatics 2011;27:334–42. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier CH, Cresawn SG, Hatfull GF. PhaMMseqs: a new pipeline for constructing phage gene phamilies using MMseqs2. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2022;12:jkac233. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier CH, Hatfull GF. PhamClust: a phage genome clustering tool using proteomic equivalence. mSystems 2023;8:e00443-23. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M. VICTOR: genome-based phylogeny and classification of prokaryotic viruses. Bioinformatics 2017;33:3396–404. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk H-P, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 2013;14:60. [CrossRef]

- Lefort V, Desper R, Gascuel O. FastME 2.0: A Comprehensive, Accurate, and Fast Distance-Based Phylogeny Inference Program: Table 1. Mol Biol Evol 2015;32:2798–800. [CrossRef]

- Farris JS. Estimating Phylogenetic Trees from Distance Matrices. The American Naturalist 1972;106:645–68. [CrossRef]

- Yu G. Using ggtree to Visualize Data on Tree-Like Structures. CP in Bioinformatics 2020;69:e96. [CrossRef]

- Göker M, García-Blázquez G, Voglmayr H, Tellería MT, Martín MP. Molecular Taxonomy of Phytopathogenic Fungi: A Case Study in Peronospora. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e6319. [CrossRef]

- Alcock BP, Huynh W, Chalil R, Smith KW, Raphenya AR, Wlodarski MA, Edalatmand A, Petkau A, Syed SA, Tsang KK, Baker SJC, Dave M, McCarthy MC, Mukiri KM, Nasir JA, Golbon B, Imtiaz H, Jiang X, Kaur K, Kwong M, Liang ZC, Niu KC, Shan P, Yang JYJ, Gray KL, Hoad GR, Jia B, Bhando T, Carfrae LA, Farha MA, French S, Gordzevich R, Rachwalski K, Tu MM, Bordeleau E, Dooley D, Griffiths E, Zubyk HL, Brown ED, Maguire F, Beiko RG, Hsiao WWL, Brinkman FSL, Van Domselaar G, McArthur AG. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Research 2023;51:D690–9. [CrossRef]

- McNair K, Bailey BA, Edwards RA. PHACTS, a computational approach to classifying the lifestyle of phages. Bioinformatics 2012;28:614–8. [CrossRef]

- Turner D, Shkoporov AN, Lood C, Millard AD, Dutilh BE, Alfenas-Zerbini P, Van Zyl LJ, Aziz RK, Oksanen HM, Poranen MM, Kropinski AM, Barylski J, Brister JR, Chanisvili N, Edwards RA, Enault F, Gillis A, Knezevic P, Krupovic M, Kurtböke I, Kushkina A, Lavigne R, Lehman S, Lobocka M, Moraru C, Moreno Switt A, Morozova V, Nakavuma J, Reyes Muñoz A, Rūmnieks J, Sarkar B, Sullivan MB, Uchiyama J, Wittmann J, Yigang T, Adriaenssens EM. Abolishment of morphology-based taxa and change to binomial species names: 2022 taxonomy update of the ICTV bacterial viruses subcommittee. Arch Virol 2023;168:74. [CrossRef]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

- Allsopp LP, Wood TE, Howard SA, Maggiorelli F, Nolan LM, Wettstadt S, Filloux A. RsmA and AmrZ orchestrate the assembly of all three type VI secretion systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017;114:7707–12. [CrossRef]

- Van Belkum A, Soriaga LB, LaFave MC, Akella S, Veyrieras J-B, Barbu EM, Shortridge D, Blanc B, Hannum G, Zambardi G, Miller K, Enright MC, Mugnier N, Brami D, Schicklin S, Felderman M, Schwartz AS, Richardson TH, Peterson TC, Hubby B, Cady KC. Phylogenetic Distribution of CRISPR-Cas Systems in Antibiotic-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2015;6:e01796-15. [CrossRef]

- Galetti R, Andrade LN, Varani AM, Darini ALC. SPM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST277 carries a chromosomal pack of acquired resistance genes: An example of high-risk clone associated with ‘intrinsic resistome.’ Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2019;16:183–6. [CrossRef]

- Argov T, Azulay G, Pasechnek A, Stadnyuk O, Ran-Sapir S, Borovok I, Sigal N, Herskovits AA. Temperate bacteriophages as regulators of host behavior. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2017;38:81–7. [CrossRef]

- Olszak T, Latka A, Roszniowski B, Valvano MA, Drulis-Kawa Z. Phage Life Cycles Behind Bacterial Biodiversity. CMC 2017;24. [CrossRef]

- Dion MB, Oechslin F, Moineau S. Phage diversity, genomics and phylogeny. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020;18:125–38. [CrossRef]

- Shah S, Das R, Chavan B, Bajpai U, Hanif S, Ahmed S. Beyond antibiotics: phage-encoded lysins against Gram-negative pathogens. Front Microbiol 2023;14:1170418. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Xie L, Yang M, Liu M, Li Q, Wang P, Fan J, Jin J, Luo C. Synergistic Antibacterial Effect of Phage pB3074 in Combination with Antibiotics Targeting Cell Wall against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii In Vitro and Ex Vivo. Microbiol Spectr 2023;11:e00341-23. [CrossRef]

- Loh B, Chen J, Manohar P, Yu Y, Hua X, Leptihn S. A Biological Inventory of Prophages in A. baumannii Genomes Reveal Distinct Distributions in Classes, Length, and Genomic Positions. Front Microbiol 2020;11:579802. [CrossRef]

- Ramisetty BCM, Sudhakari PA. Bacterial ‘Grounded’ Prophages: Hotspots for Genetic Renovation and Innovation. Front Genet 2019;10:65. [CrossRef]

- Piel D, Bruto M, Labreuche Y, Blanquart F, Goudenège D, Barcia-Cruz R, Chenivesse S, Le Panse S, James A, Dubert J, Petton B, Lieberman E, Wegner KM, Hussain FA, Kauffman KM, Polz MF, Bikard D, Gandon S, Rocha EPC, Le Roux F. Phage–host coevolution in natural populations. Nat Microbiol 2022;7:1075–86. [CrossRef]

- Gogokhia L, Buhrke K, Bell R, Hoffman B, Brown DG, Hanke-Gogokhia C, Ajami NJ, Wong MC, Ghazaryan A, Valentine JF, Porter N, Martens E, O’Connell R, Jacob V, Scherl E, Crawford C, Stephens WZ, Casjens SR, Longman RS, Round JL. Expansion of Bacteriophages Is Linked to Aggravated Intestinal Inflammation and Colitis. Cell Host & Microbe 2019;25:285-299.e8. [CrossRef]

- Naser IB, Hoque MM, Abdullah A, Bari SMN, Ghosh AN, Faruque SM. Environmental bacteriophages active on biofilms and planktonic forms of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae: Potential relevance in cholera epidemiology. PLoS ONE 2017;12:e0180838. [CrossRef]

- Balcázar JL. Implications of bacteriophages on the acquisition and spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment. Int Microbiol 2020;23:475–9. [CrossRef]

- Haaber J, Leisner JJ, Cohn MT, Catalan-Moreno A, Nielsen JB, Westh H, Penadés JR, Ingmer H. Bacterial viruses enable their host to acquire antibiotic resistance genes from neighbouring cells. Nat Commun 2016;7:13333. [CrossRef]

- Hilbert M, Csadek I, Auer U, Hilbert F. Antimicrobial resistance-transducing bacteriophages isolated from surfaces of equine surgery clinics – a pilot study. EuJMI 2017;7:296–302. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva G, Domingues S. Insights on the Horizontal Gene Transfer of Carbapenemase Determinants in the Opportunistic Pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 2016;4:29. [CrossRef]

- Silveira MC, Albano RM, Asensi MD, Carvalho-Assef APD. Description of genomic islands associated to the multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone ST277. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2016;42:60–5. [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento APB, Medeiros Filho F, Pauer H, Antunes LCM, Sousa H, Senger H, Albano RM, Trindade Dos Santos M, Carvalho-Assef APD, Da Silva FAB. Characterization of a SPM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa by comparative genomics and phenotypic analysis. Sci Rep 2020;10:13192. [CrossRef]

| Most common prophages | Less Common Prophages | |||

| Phage | Total | Phage | Total | |

| Bacteriophage sp. | 147 | Pseudomonas phage PAJU2 | 1 | |

| Caudoviricetes sp. | 136 | Escherichia phage P1 | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage phi3 | 50 | Pseudomonas phage JBD26 | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage phi297 | 35 | Pseudomonas phage PA8 | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage H71 | 32 | Pseudomonas phage JBD5 | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage Dobby | 25 | Burkholderia phage phiE255 | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage AUS531phi | 24 | Pseudomonas phage vB_Pae_CF125a | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage phiCTX | 22 | Ralstonia phage Dina | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage vB_Pae_CF54a | 16 | Pseudomonas phage D3112 | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas phage UMP151 | 15 | Pseudomonas phage MP42 | 1 | |

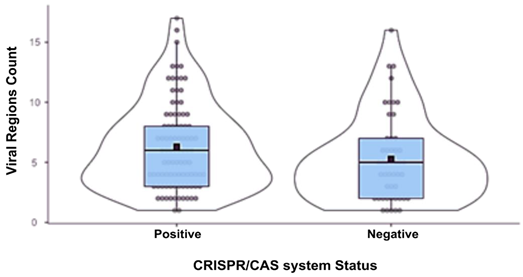

| Group Description | ||||||||||

| Group | N | Mean | median | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | |||||

| Phage Region Count | Positive | 93 | 6.31 | 6 | 3.64 | 0.377 | ||||

| Negative | 48 | 5.29 | 5 | 3.64 | 0.525 | |||||

| ||||||||||

| Correlation matrix | ||||||||||

| Viral region count | CRISPR/Cas status | |||||||||

| CRISPR/Cas status | Spearman’s rho | 0,150 | - | |||||||

| p-value | 0,076 | - | ||||||||

| Note. * p < .05** p <.01*** p <.001 | ||||||||||

| Highest number of prophages identified | Fewest number of prophages identified | |||

| Isolate | Nº prophages | Isolate | Nº prophages | |

| CCBH28612 | 17 | AZPAE15065 | 1 | |

| H2-9me | 16 | ET02 | 1 | |

| Pae28 | 16 | Pae113 | 1 | |

| Pae39 | 15 | UFMG-H6 | 1 | |

| AZPAE14853 | 13 | UFMG-H7 | 1 | |

| CCBH27346 | 13 | UFMG-H9 | 1 | |

| JM03 | 13 | UFMG-H10 | 1 | |

| LIM1030 | 13 | Pae93 | 2 | |

| Pae83 | 13 | Pae94 | 2 | |

| BH6 | 12 | Pae110 | 2 | |

| Isolate | ST | Phage | AMR gene | Life cycle |

| AZEPAE14852 | 639 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Lytic |

| AZEPAE14853 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Lytic |

| CCBH27678 | 3079 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Temperate |

| CCBH28189 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Lytic |

| CCBH28529 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage phi3 | rmtD | Lytic |

| CCBH28529 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | sul1 | Lytic |

| CCBH28850 | 3079 | Caudoviricetes sp. | dfrA21 | Lytic |

| CCBH28850 | 3079 | Caudoviricetes sp. | sul1 | Lytic |

| H2-9me | 235 | Pseudomonas phage DMS3 | rsmA | Temperate |

| JX05 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage AUS531phi | sul1 | Lytic |

| JX05 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage AUS531phi | sul1 | Lytic |

| JX05 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage AUS531phi | cmx | Lytic |

| JX05 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage AUS531phi | aadA7 | Lytic |

| JX05 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage AUS531phi | OXA-56 | Lytic |

| LIM1030 | 308 | Bacteriophage sp. | sul1 | Lytic |

| LIM1030 | 308 | Bacteriophage sp. | sul1 | Lytic |

| LIM1166 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage phi3 | cmx | Lytic |

| LIM1166 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Temperate |

| LIM1166 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Temperate |

| LIM1166 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage phi3 | cmx | Lytic |

| LIM1166 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Temperate |

| LIM1256 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Lytic |

| LIM1410 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | OXA-56 | Temperate |

| LIM1410 | 277 | Pseudomonas phage phi3 | P. aeruginosa emrE | Lytic |

| LIM1410 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | AAC(6')-Ib9 | Temperate |

| LIM1410 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | aadA7 | Temperate |

| LIM1547 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | sul1 | Temperate |

| LIM1547 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | cmx | Temperate |

| LIM1547 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | cmx | Temperate |

| LIM1547 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | sul1 | Temperate |

| LIM1680 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | SPM-1 | Lytic |

| LIM1680 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | OXA-56 | Lytic |

| LIM1680 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | AAC(6')-Ib9 | Lytic |

| LIM1680 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | aadA7 | Lytic |

| LIM4519 | 277 | Bacteriophage sp. | cmx | Lytic |

| LIM4519 | 277 | Caudoviricetes sp. | rsmA | Temperate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).