Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Allure and Difficulty of Origins

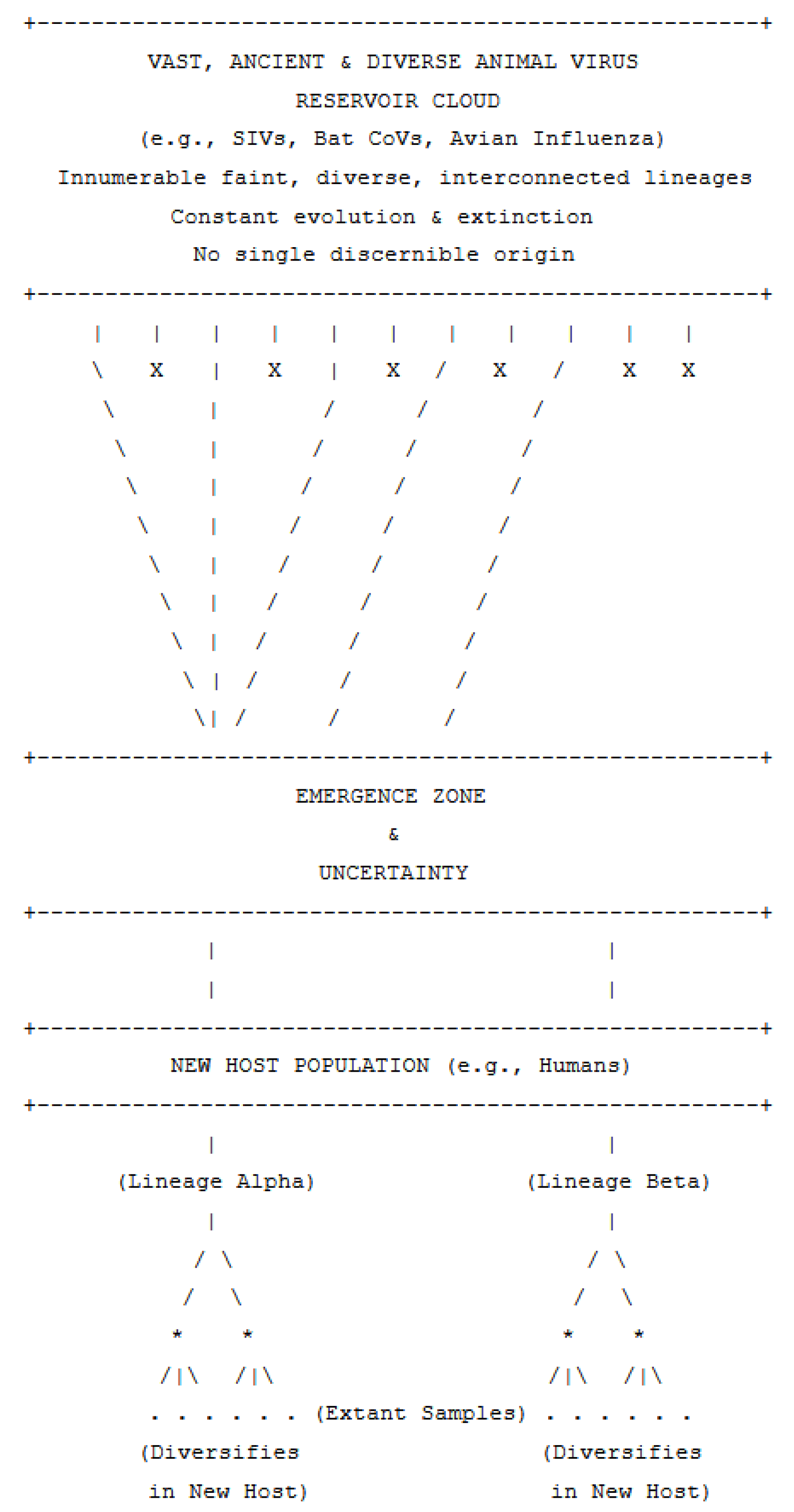

2. The Challenge of Pinpointing Viral Ancestors: An Analogy

3. Case Studies in Viral Emergence and Deep History

3.1. The Multiplicity of Origins: Lessons from Simian and Human Immunodeficiency Viruses

- Diverse SIV Reservoir. Dozens of SIV lineages have been identified in many species of African non-human primates. These SIVs are often species-specific and have likely co-evolved with their primate hosts for thousands, if not millions, of years, creating an immense and ancient "reservoir cloud" of viral diversity.

- Multiple Independent Spillovers. Crucially, HIV-1 did not arise from a single SIV transmission. Phylogenetic analyses reveal at least four distinct HIV-1 groups (M, N, O, and P), each reported [3] as an independent cross-species transmission of SIVcpz from chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) or SIVgor from gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) – gorillas themselves likely acquired their SIV from chimpanzees. HIV-2 also has at least nine distinct groups (A-I), each originating from independent transmissions of SIVsmm from sooty mangabeys (Cercocebus atys). These findings are subject to refinement as other primate populations are sampled.

- Stochastic Nature of Establishment. Each of these successful spillovers represents a rare, stochastic event where a particular SIV variant managed to infect a human, replicate, adapt sufficiently to sustain human-to-human transmission, and establish a new lineage. Countless other SIV exposures to humans likely occurred without leading to sustained epidemics.

- Recombination's Role. Once established in humans, particularly for HIV-1 Group M (responsible for the vast majority of the global pandemic), recombination between different co-infecting subtypes has led to the generation of numerous Circulating Recombinant Forms (CRFs), further diversifying the virus and complicating phylogenetic reconstruction [4,5].

3.2. Influenza A Virus: Ancient Reservoirs and Stochastic Reassortment

- Avian Reservoir. Wild aquatic birds, particularly waterfowl, are considered the primary natural reservoir for almost all IAV subtypes (HxNy) [6]. Within these bird populations, IAVs exhibit enormous genetic diversity and generally cause asymptomatic infections, co-evolving over long periods.

- Reassortment and Antigenic Shift. IAVs have a segmented genome (eight RNA segments). If two different IAV strains co-infect the same cell, their segments can be "shuffled" during the assembly of new virus particles, producing reassortant viruses with novel combinations of genes. This is the primary mechanism behind antigenic shift, which can lead to the emergence of pandemic influenza strains when a virus with a hemagglutinin (HA) and/or neuraminidase (NA) subtype novel to the human population acquires the ability to transmit efficiently between humans.

- Pandemic Origins:

- The 1957 (H2N2 "Asian flu") and 1968 (H3N2 "Hong Kong flu") pandemics arose from reassortment events where human-adapted IAVs acquired HA/NA and polymerase (PB1) segments from avian influenza viruses.

- The 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus was a particularly complex "quadruple reassortant," possessing segments derived from North American swine, Eurasian swine, human seasonal, and North American avian IAV lineages, likely assembled through multiple reassortment steps in swine, which act as "mixing vessels" [7,8]. Each of these reassortment events is a stochastic process, dependent on co-infection and the viable packaging of a new constellation of segments.

- Challenges in Deep Ancestry. While we can trace the origins of segments in recent pandemic strains to broad avian or swine lineages, identifying the specific ancestral avian virus that contributed, for example, the HA to the 1957 H2N2 pandemic, or the precise sequence of reassortment events in swine leading to the 2009 H1N1, becomes increasingly difficult further back in time due to continuous evolution and extinction of intermediate lineages in animal reservoirs.

3.3. SARS-CoV-2: Reconstructing Recent Emergence and Ongoing Recombination

- Zoonotic Origin. The weight of evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2 originated from a coronavirus in an animal reservoir, most likely bats, potentially with an intermediate animal host facilitating its spillover to humans [9].

- Role of Recombination. The Spike protein's receptor-binding domain (RBD), crucial for human ACE2 receptor binding, shows evidence suggestive of recombination with coronaviruses from other animal species (e.g., pangolins), although the exact details and timing of such events are still debated and subject to the availability of more comprehensive animal reservoir sampling [10].

- Challenges in Identification. 1) Reservoir Sampling. Despite extensive searching, the exact bat coronavirus population that served as the direct progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 has not been definitively identified. Bats host a vast diversity of coronaviruses, and the specific lineage that jumped to humans (or an intermediate host) may be rare, geographically restricted, or even extinct. 2) Intermediate Host(s). If an intermediate host was involved, identifying it and the specific viral lineage it carried is also challenging. 3) Stochasticity of Spillover. The actual spillover event was likely a stochastic process, possibly one of many attempted jumps that only rarely succeeded.

- Ongoing Recombination in Human Variants. During the pandemic, recombination between circulating SARS-CoV-2 lineages (e.g., between different Omicron sublineages like those forming the XBB lineage) has been documented. The XBB lineage, itself a recombinant of two Omicron BA.2 sublineages, subsequently gave rise to further subvariants like XBB.1.16 ("Arcturus"), which acquired additional mutations impacting transmissibility and immune evasion [11]. These events highlight how recombination can create new genetic backbones for further mutational refinement.

4. Broader Implications: Sampling, Modeling, and the Nature of Viral Ancestry

- Sampling Effects are Profound. Our understanding of viral diversity and origins is entirely constrained by what we sample. Wildlife reservoirs are notoriously undersampled, and even within human populations, surveillance is often biased towards symptomatic cases or specific geographic regions. The "viral dark matter" – the vast majority of viruses that exist but have not been sequenced – means our phylogenetic trees are sparse representations of true viral evolutionary history.

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction Limits. While powerful for recent events and well-sampled populations, phylogenetic methods struggle with deep ancestral reconstruction for rapidly evolving viruses with extensive recombination/reassortment. Long branches, homoplasy, and conflicting signals from different genomic regions can obscure deep relationships. Molecular clock estimates for deep viral origins are often highly uncertain due to rate variation and lack of ancient calibration points.

- Ancestral State Reconstruction vs. Pinpointing an Ancestor. It is important to distinguish between inferring the characteristics of an ancestral viral population or node (e.g., likely genetic sequences at certain sites, probable host) and identifying the specific individual ancestral virus. The former is a probabilistic inference based on extant diversity; the latter is generally not feasible for deep time.

- Rethinking "Patient Zero" Narratives. For many viral emergences, the search for a single "patient zero" or a single animal source, while important for initial outbreak control, may be an oversimplification of a more complex ecological and evolutionary process involving a population of viruses in a reservoir and multiple potential spillover opportunities.

5. Conclusion: Embracing Stochasticity and Probabilistic Understanding

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmes, E. C. , & Drummond, A. J. The evolutionary genetics of viral emergence. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, 2007, 315, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedman, R. A Hierarchy of Interactions between Pathogenic Virus and Vertebrate Host. Symmetry, 2022, 14, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P. M. , & Hahn, B. H. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2011, 1, a006841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D. L. , Anderson, J. P., Bradac, J. A., Carr, J. K., Foley, B., Funkhouser, R. K.,... & Korber, B. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science, 2000, 288, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hemelaar, J. The origin and diversity of the HIV-1 pandemic. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 2012, 18, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, R. G. , Bean, W. J., Gorman, O. T., Chambers, T. M., & Kawaoka, Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiological Reviews, 1992, 56, 152–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garten, R. J. , Davis, C. T., Russell, C. A., Shu, B., Lindstrom, S., Balish, A.,... & Cox, N. J. Antigenic and Genetic Characteristics of Swine-Origin 2009 A(H1N1) Influenza Viruses Circulating in Humans. Science, 2009, 325, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, G. J. D. , Vijaykrishna, D., Bahl, J., Lycett, S. J., Worobey, M., Pybus, O. G.,... & Rambaut, A. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature, 2009, 459, 1122–1125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K. G. , Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W. I., Holmes, E. C., & Garry, R. F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine, 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X. , Giorgi, E. E., Marichannegowda, M. H., Foley, B., Xiao, C., Kong, X. P.,... & Gao, F. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection. Science Advances, 2020, 6, eabb9153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uriu, K. , Ito, J., Zahradnik, J., Fujita, S., Kosugi, Y., Schreiber, G. Enhanced transmissibility, infectivity, and immune resistance of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron XBB.1.5 variant. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2023, 23, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).