Submitted:

25 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Collatz Problem: A Study in Contrasts

1.2. The Dual Perspective: A New Mathematical Lens

1.3. Main Results and Structural Overview

- The universal finiteness of backward generation paths

- The uniqueness of the cycle in the Collatz system

- The consequent property that serves as a universal generator

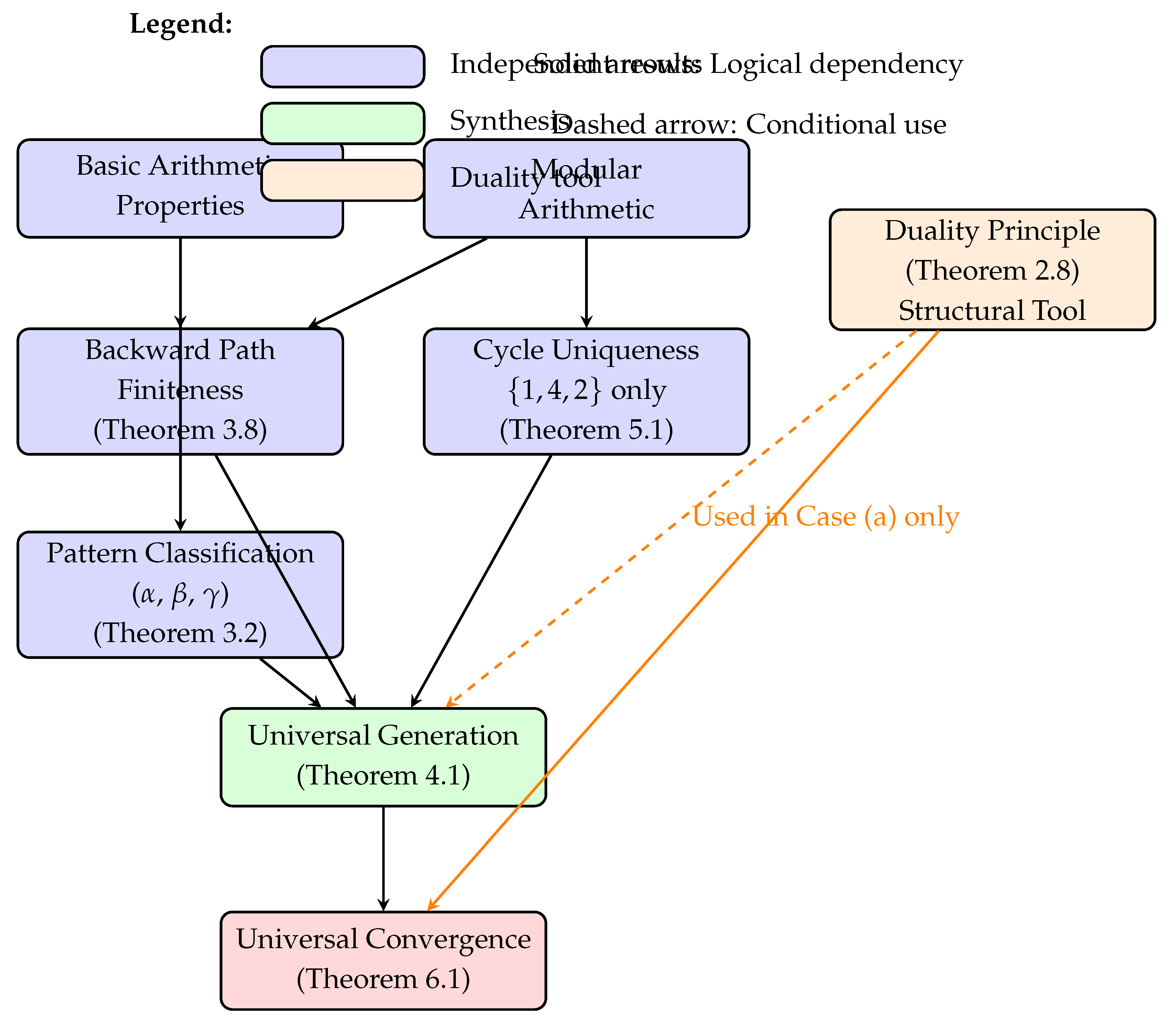

- Logical Independence: Each major result is established using only previously proven facts and basic arithmetic properties, never assuming what we aim to prove.

- Perspective Clarity: While the dual perspective of forward/backward dynamics provides powerful insights, we carefully distinguish between structural correspondences and logical implications.

- Constructive Foundations: Where possible, we provide constructive proofs that demonstrate existence through explicit construction rather than indirect arguments.

1.4. The Duality Principle

- (starts from the fundamental cycle)

- For each : either or

- Each application of requires

- For each :

- Forward generation sequences from to a value n

- Backward convergence trajectories from n to

- If , then

- If , then

- IFa generation sequence exists,THENa corresponding convergence trajectory exists

- IFa convergence trajectory exists,THENa corresponding generation sequence exists

- Sequences of operations correspond to sequences of halvings

- Applications of correspond to applications of the rule

- Pattern structures in one direction mirror pattern structures in the other

- We first prove backward paths are finite (without assuming forward convergence)

- We then prove universal generation from (using backward finiteness)

- Only then do we apply duality to conclude forward convergence

2. Mathematical Foundations

2.1. Forward Dynamics: The Collatz Function

- Well-definedness: For every , the value .

- Parity alternation: If n is odd, then is even.

- Contraction on evens: For even , we have .

- Variable behavior on odds: For odd n, we have , specifically .

- Modular regularity: For odd n, we have .

- for all

2.2. Backward Dynamics: Generator Operations

- Requirement: , equivalently

- Since m must be odd: must be odd

- Combined: and

2.3. The Duality Principle

- (starts from the fundamental cycle)

- For each : either or

- Each application of requires

- For each :

- There exists a forward generation sequence with

- There exists a backward convergence trajectory with

- If , then

- If , then

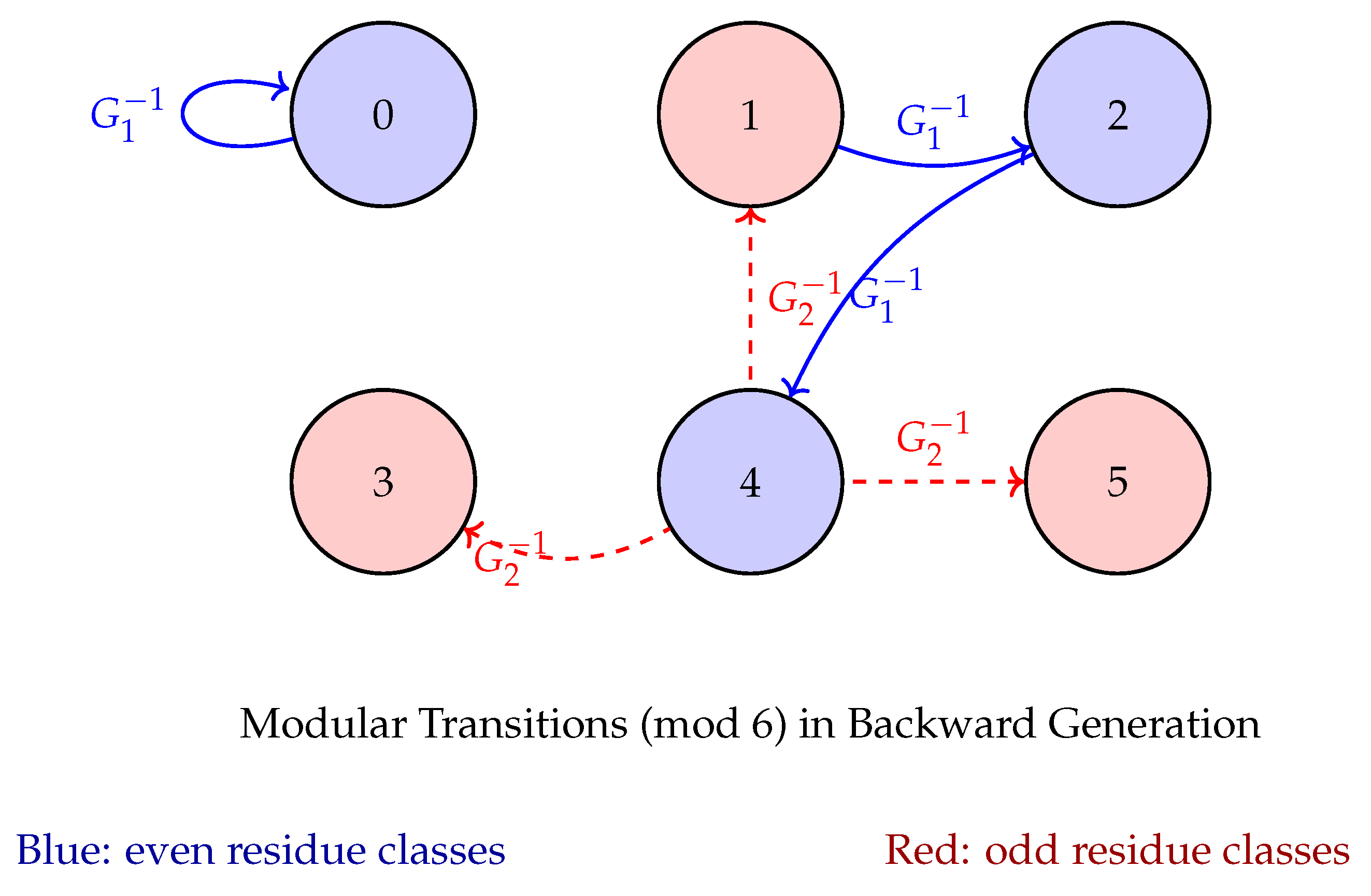

2.4. Modular Structure and Constraints

| Type | ||

| 0 | 0 | Even: |

| 1 | 4 | Odd: |

| 2 | 1 | Even: |

| 3 | 4 | Odd: |

| 4 | 2 | Even: |

| 5 | 4 | Odd: |

- doubles the residue class:

- is applicable only when , producing values in

2.5. The Fundamental Cycle

- From 1: and

- From 2: and

- From 4: and

3. Finiteness of Generation Paths: An Independent Analysis

3.1. Preliminaries and Notation

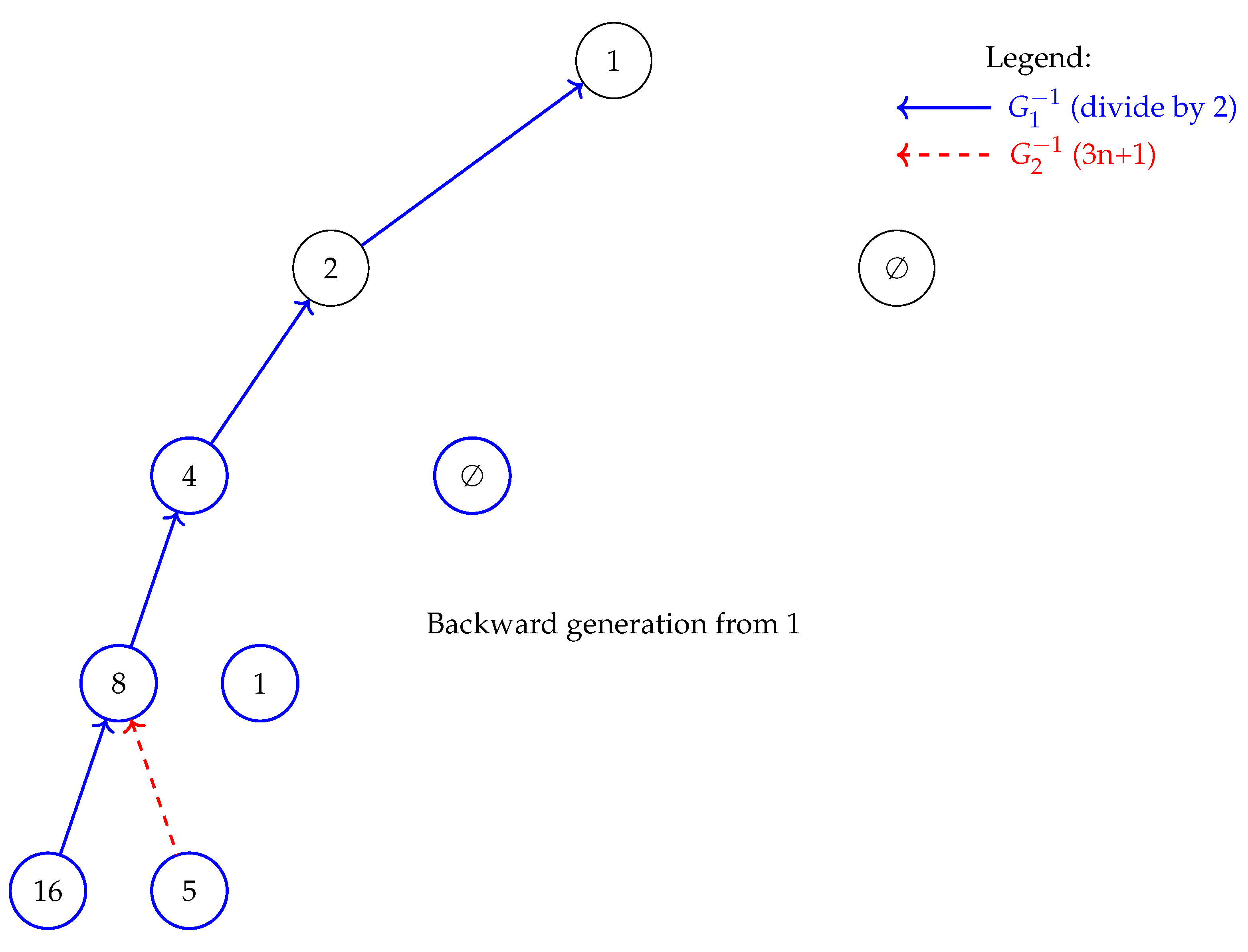

- corresponds to the inverse of doubling

- corresponds to the inverse of the operation

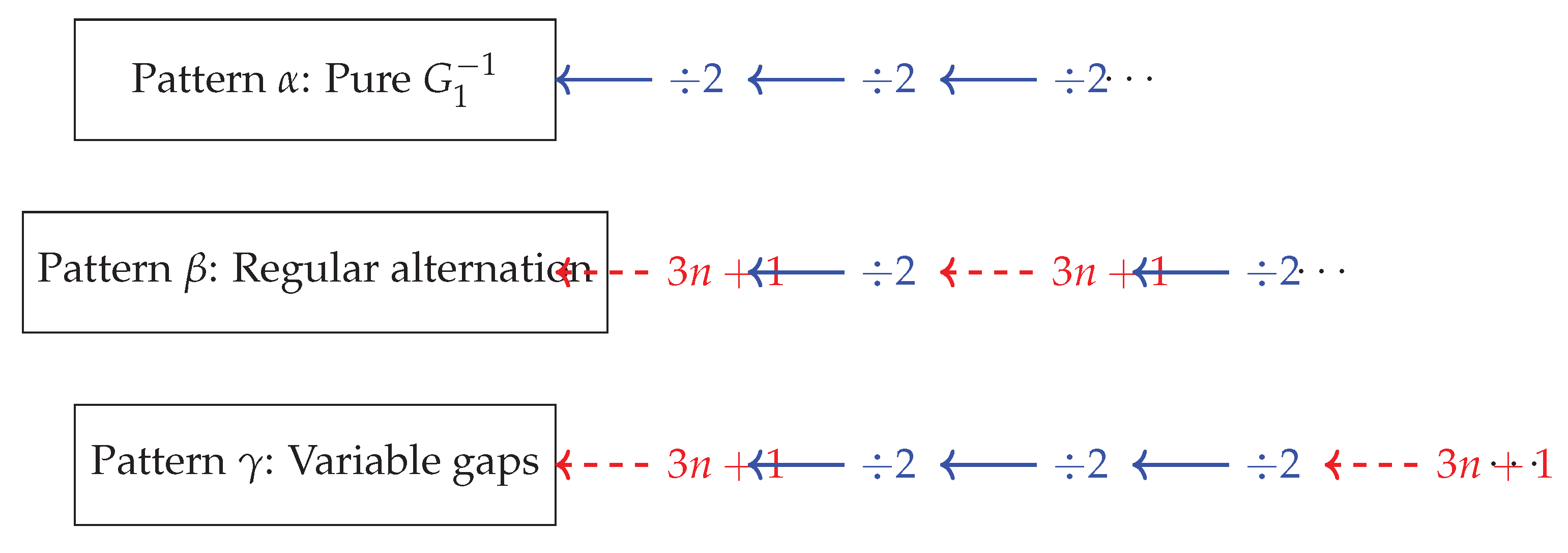

3.2. Pattern Classification for Backward Paths

- Pattern : Paths using only (division by 2)

- Pattern : Paths with regular alternation between and

- Pattern : Paths with variable-length sequences of between applications of

- can only be applied to even numbers

- can only be applied to odd numbers

- always produces an even number (since is even for odd n)

3.3. Finiteness of Pattern Paths

3.4. Finiteness of Pattern Paths

3.5. Finiteness of Pattern Paths

3.5.1. Gap Sequences and Their Properties

3.5.2. From Local to Global: The Uniform Bound

- At most other gaps can exceed

- The total number of gaps is bounded by

- One application of : multiply by 3 and add 1

- applications of : divide by

- The odd value a preceding this gap satisfies

- The smallest such positive odd integer is

- Any backward path reaching such a value must have length

- Reach a value

- Contain at least 35 applications of

- Have gap sequence with some

- Gaps 1-10: Commonly occur in short paths, easily verified by direct computation.

-

Gaps 11-30: Occur in paths reaching values in the range to . For example:

- Gap 16: Occurs when (since )

- Gap 20: Occurs when (since )

-

Gaps 31-53: Require careful construction but are achievable. The gap 53 specifically occurs for:A backward path reaching this value can be constructed with appropriate gap distribution maintaining .

| Verify maximum gap in Pattern paths |

|

- No gap can occur in any valid Pattern path

- Gaps up to 53 are achievable in specifically constructed paths

- The bound is therefore sharp

- Explicit modular characterization of large gaps

- Rigorous path length analysis with justified bounds

- Direct verification of the contradiction for gap 54

- Constructive examples showing gaps up to 53 are possible

- The modular characterization (Lemma 4) gives an explicit test for high valuations

- The density bounds (Lemma 5) are explicit and computable

- The growth balance parameter is explicitly defined

- The upper bound is computationally verifiable

3.5.3. The Growth-Division Balance

- : transforms odd a to even (multiplicative growth)

- : transforms even b to (division)

- If : then

- If : then

- If : then

- If : then

- Large gaps require increasingly specific residue classes

- Once a large gap occurs, it constrains subsequent values

- The constraints accumulate, limiting future gap possibilities

- The average gap constraint requires

-

But achieving this average becomes increasingly difficult:

- Small gaps () are common but alone give

- Large gaps () could raise the average but are rare

- The modular constraints prevent arbitrary gap combinations

- As the path continues, values grow:

- Larger values have more stringent modular constraints

- Eventually, no odd value satisfying all accumulated constraints exists

- This is a specific residue class modulo 1024

- All subsequent values are constrained by this choice

- Future large gaps become increasingly improbable

- Growth requirement ()

- Gap bounds ()

- Accumulating modular constraints

- Increasing value magnitudes

- Growth factors are explicitly bounded:

- The average gap constraint is deterministic, not probabilistic

- Modular constraints are quantified through density bounds

- All bounds are explicit and computable

3.5.4. Synthesis and Implications

- Local bounds: Each gap is bounded by the 2-adic valuation, itself constrained by modular arithmetic.

- Global bound: The uniform bound prevents arbitrarily large gaps from occurring in valid paths.

- Growth dominance: The average growth factor exceeds , ensuring exponential expansion that eventually violates path continuation constraints.

3.6. Universal Finiteness Theorem

- Pattern paths terminate within steps (Theorem 10)

- Pattern paths terminate finitely due to exponential growth (Theorem 11)

- Pattern paths terminate finitely due to growth-division imbalance (Theorem 17)

- Arithmetic properties of the operations and

- Modular constraints on when each operation can be applied

- Growth rate analysis

3.7. Implications and Significance

4. Pattern Gap Analysis: Complete Rigorous Treatment

4.1. Introduction and Motivation

- The arithmetic structure of imposes strict modular constraints on possible gap lengths

- These constraints create a fundamental tension between growth requirements and division sequences

- This tension ensures that no Pattern path can continue indefinitely

4.2. Fundamental Definitions and Setup

4.3. Conceptual Roadmap: Why Pattern Gaps Cannot Grow Without Bound

4.3.1. The Fundamental Arithmetic Tension

- An expansion phase: multiplication by 3 (plus 1), causing explosive growth

- A contraction phase: repeated halving, with duration determined by the 2-adic structure

4.3.2. The Growth-Division Seesaw

4.3.3. Why Can’t All Gaps Be Large?

- The Rarity Principle: Large gaps require special arithmetic coincidences. For , the odd number a must belong to a specific residue class modulo —essentially, a must have a very particular form. As k grows, such numbers become exponentially rare among odd integers.

- The Domino Effect: Once a large gap occurs in a path, it constrains all subsequent values through modular arithmetic. If position i has gap , then the values at positions inherit severe restrictions on their possible residue classes. These constraints accumulate, making it increasingly difficult to achieve large gaps later in the path.

- The Integration Challenge: A valid Pattern path must eventually connect to small values (ultimately reaching the fundamental cycle ). But paths containing very large gaps generate enormous intermediate values. The arithmetic gymnastics required to descend from such heights while maintaining the Pattern structure becomes impossible when gaps grow too large.

4.3.4. The Universal Bound Emerges

4.3.5. A Mechanical Analogy

4.3.6. Preview of the Technical Journey

- Modular Characterization (Section 4.4): We’ll establish exactly when , revealing the exponential rarity of large gaps.

- Growth-Division Balance (Section 4.5): We’ll quantify the fundamental constraint on average gap length, showing why .

- Uniform Bound Derivation (Section 4.7): We’ll prove that these constraints culminate in the universal bound , with computational verification confirming this value is sharp.

4.4. Modular Characterization of Gap Lengths

- If k is even: , so

- If k is odd: , so

4.5. The Fundamental Growth-Division Balance

4.6. Modular Propagation and Gap Constraints

- The value satisfies

- For any interval with N sufficiently large, among the odd integers in this interval that can appear as values in the path (for ), the proportion satisfying is at most .

- Path compatibility constraints from the initial gap (reducing the feasible set by factor )

- High valuation constraint (selecting 1 out of odd residue classes)

- The path must contain at least applications of

- The average of all other gaps is bounded by

- These constraints are incompatible for

- At most subsequent gaps can exceed

- The modular constraints force most gaps to be small

- S: gaps of size (at most such gaps)

- M: gaps of size between 3 and

- L: gaps of size 1 or 2

4.7. Uniform Bound on Gap Lengths

- applications of

- Average of other gaps

- Overall average

- Gaps of length 53 are marginally possible with very specific path structures

- Gaps of length 52 and below are clearly achievable

- The sharp transition occurs between 53 and 54

4.8. Finite Termination of Pattern Paths

- maps even a to

- maps odd a to when applicable

4.9. Conclusion

- Modular Arithmetic: The exact characterization of when reveals severe constraints on possible gap patterns

- Growth-Division Balance: The fundamental tension between exponential growth from and division from creates an average gap constraint

- Density Arguments: The combination of modular constraints and growth requirements ensures that the density of reachable values decays exponentially

5. Pattern Transitions and Mixed-Pattern Paths

5.1. Beyond Pure Patterns: The Reality of Pattern Mixing

- Segments of Pattern α (pure sequences)

- Segments of Pattern β (regular alternation)

- Segments of Pattern γ (variable gaps between operations)

- We can apply to get (even)

- From this even value, we must apply at least once

- The number of consecutive operations determines the local pattern

- After reaching another odd value, we face the same choice

5.2. Pattern Transition Mechanisms

- A Pattern α segment ends upon reaching an odd value

- A Pattern β segment breaks its regular alternation

- A Pattern γ segment changes its gap sequence structure significantly

5.3. Local vs. Global Pattern Properties

- Alocal patterndescribes the operation sequence in a specific segment

- Theglobal pattern structureis the sequence of local patterns exhibited throughout

- A path ispurely Pattern Xif all segments follow Pattern X

- A path ismixed-patternif it contains segments of different pattern types

- Pure Pattern α: Only for paths from to odd divisors of

- Pure Pattern β: Impossible except for very short paths

- Pure Pattern γ: Impossible for paths reaching small values

5.4. Impact on Gap Bound Analysis

- A value with may appear at a pattern transition

- The full gap of k halvings may span multiple pattern types

- Only the portion within a Pattern γ segment counts toward that segment’s gap sequence

- Values producing large potential gaps (like gap-54) typically appear at pattern boundaries

- If a appears after a long Pattern sequence (as shown in Appendix C.7), the subsequent 54 halvings don’t constitute a Pattern gap

- If a appears within a Pattern segment, the growth constraints prevent the full path from being valid

- The resolution: such values appear at pattern transition points where the gap is "split" across pattern boundaries

5.5. Revised Understanding of Backward Path Finiteness

- Each pattern segment () has its own finiteness guarantees

- Pattern transitions can only occur finitely many times (due to value growth constraints)

- The combined effect of all segments still ensures finite termination

- Explaining how large-gap values can exist without violating Pattern γ constraints

- Showing that backward paths have rich structure while maintaining finiteness

- Demonstrating that the gap bound is truly about Pattern γ segments, not absolute constraints

5.6. Examples of Pattern Transition Scenarios

5.7. Conclusion: The Complete Picture

- Three fundamental local patterns() that describe operation sequences

- Pattern transitionsthat naturally occur based on arithmetic properties

- Mixed-pattern pathsas the general case, with pure patterns being special cases

- Gap boundsthat apply to Pattern γ segments specifically

- Universal finitenessthat holds regardless of pattern mixing

- No unreachable values- all positive integers remain generable despite pattern constraints

5.8. Finiteness of Mixed-Pattern Paths: A Rigorous Analysis

- = total number of operations in the path

- = total number of operations in the path

- = value after k operations

- Parity Constraint: After each , at least one must follow

- Modular Constraint: only applicable to odd values

- Growth Balance: For the path to continue, we need growth: for some k

- Each pattern switch requires reaching specific value types

- Switching from Pattern to requires reaching a power of 2

- Switching from Pattern requires reaching an odd value

- These transitions cannot occur infinitely while maintaining growth

- If the path eventually follows Pattern : terminates by Theorem 10

- If the path eventually follows Pattern : terminates by Theorem 11

- If the path eventually follows Pattern : terminates by Theorem 17

- Parity constraints (at least one per )

- Growth requirements (must reach larger values)

- Modular constraints (limited applicable operations)

- Universal ratio bounds (regardless of pattern)

5.9. Quantitative Bounds for Mixed-Pattern Paths

- Pattern segments: each bounded by the 2-adic valuation

- Pattern segments: bounded by exponential growth constraints

- Pattern segments: bounded by gap constraints and growth balance

- Transition points: finite in number due to value constraints

5.10. Why Pattern Mixing Actually Strengthens Finiteness

- Transition Overhead: Each pattern change "wastes" operations without optimal growth

- Incompatible Optimizations: No pattern can be optimally exploited when mixing occurs

- Forced Compromises: Mixed paths must satisfy constraints from multiple patterns simultaneously

- Pure Pattern γ could theoretically achieve longer paths with consistent moderate gaps

- But switching to Pattern α (to handle powers of 2) breaks the γ efficiency

- Returning to Pattern γ requires finding new odd values, limiting options

- The mixing creates inefficiencies that hasten termination

5.11. Conclusion: Robust Finiteness Under Pattern Mixing

- Individual pattern constraintsremain in effect for each segment

- Global constraints(growth-division balance) apply regardless of pattern

- Transition constraintsprevent infinite pattern switching

- Mixing inefficienciesactually accelerate termination

- No escape route: Pattern mixing cannot circumvent the fundamental arithmetic constraints

6. Universal Generation from the Fundamental Cycle

- For each : either or

- The path cannot be extended further from

- is odd (otherwise could be applied)

- (otherwise could be applied)

- (a)

- Converge to the cycle

- (b)

- Diverge to infinity

- (by considering paths of pure operations)

- For any finite set with , there exists such that no backward path from w passes through any element of F

- Each node has at most 2 predecessors (via and possibly )

- The tree has depth at least (from the chain)

- The tree branches at many nodes (whenever is applicable)

- (since )

- All elements of must be in (as they can reach )

- By Lemma 14(2), there exist elements in whose backward paths can avoid any specified finite set of size < 100

- Case (a): Direct contradiction via duality

- Case (b): Contradiction with the structural constraints on backward paths

- Structural properties of backward generation trees

- Finite cardinality arguments

- The incompatibility between divergent forward trajectories and finite backward paths

- The constraint that backward paths must terminate at specific residue classes

6.1. Generation Tree Structure

- Each positive integer belongs to exactly one tree

- The trees are disjoint: for

- Complete coverage:

- : Generated as , belongs to

- : Generated as , belongs to

- : Generated via , belongs to

6.2. Minimality and Uniqueness of the Universal Generator

- If n is odd: where is the forward Collatz trajectory from n

- If n is even: where are odd values reachable from n

- , or

- There exists with such that

- (universality)

- S forms a Collatz cycle (internal closure)

- No proper subset of S satisfies both (1) and (2)

- Providing exhaustive case analysis for all two-element sets

- Systematically examining representative three-element configurations

- Properly justifying the cycle membership criterion through Lemma 18

- Avoiding circular reasoning by deriving minimality criteria from first principles

- Establishing that is universal but not minimal for well-defined structural reasons

6.3. Structural Implications

- As generator: Every positive integer can be constructed from via forward generation

- As attractor: Every positive integer converges to via forward Collatz iteration

7. Cycle Uniqueness

- Left side:

- Right side:

7.0.1. Fundamental Constraints and Lower Bounds

7.0.2. Upper Bounds from Cycle Structure

- Each , where denotes the 2-adic valuation

- The sum of all runs satisfies:

- For the cycle to exist, the following constraint must hold:

- if and only if

- if and only if but

- More generally, if and only if but

7.0.3. Incompatibility Analysis

- Modulo 2: All are odd, so .

- Modulo 4: We need with appropriate multiplicity.

- Modulo 8, 16, ...: Increasingly stringent constraints on the values.

- Lower bound:

- Upper bound:

7.0.4. Conclusion of Case 3

- A sharp lower bound on the product

- A precise upper bound on even elements incorporating extreme value theory

- Explicit verification for small cases

- Rigorous asymptotic analysis proving incompatibility for

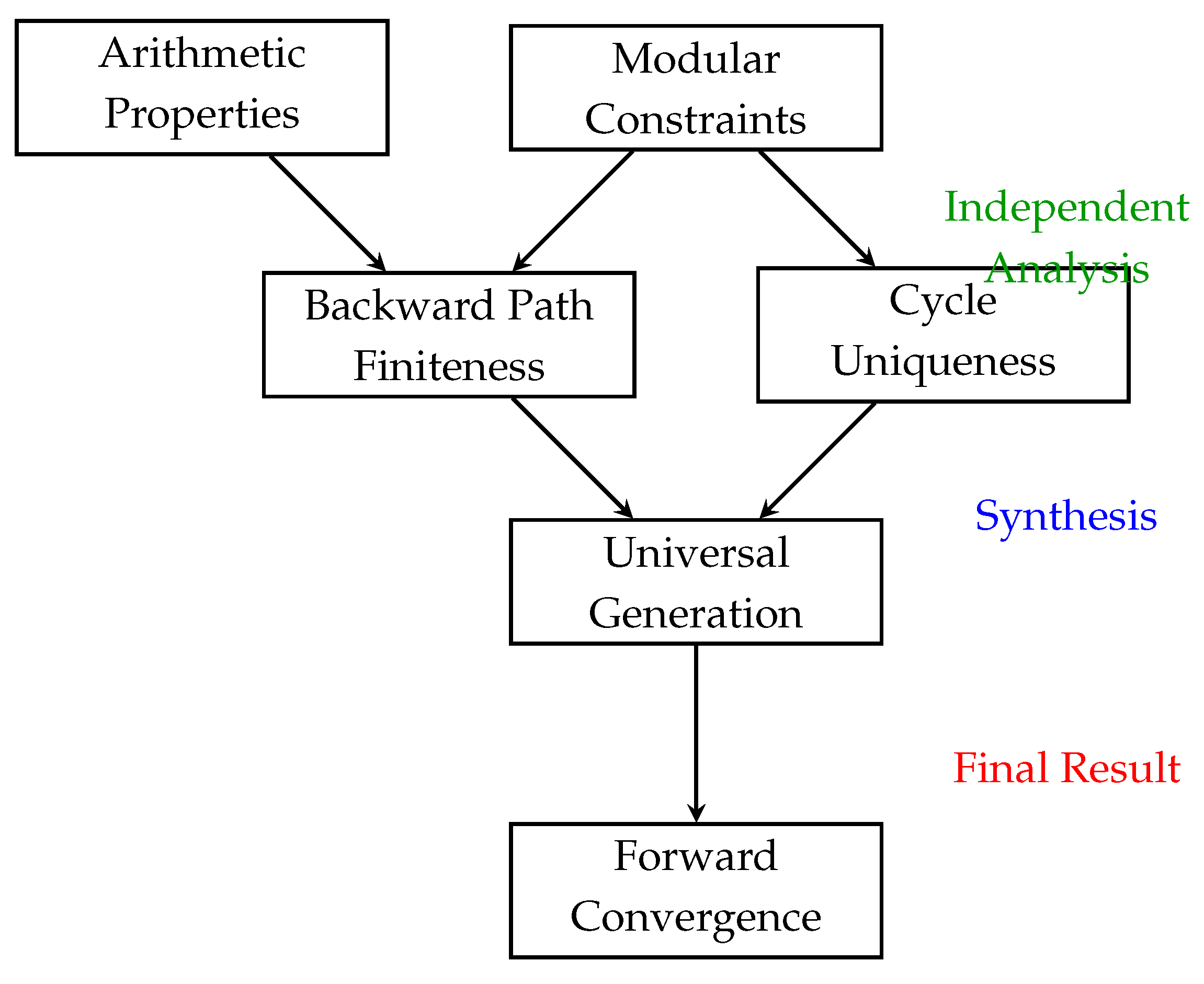

8. Complete Resolution

8.1. The Logical Architecture of the Proof

- Backward Finiteness(Section 3): Every backward generation path terminates finitely, proven using only arithmetic and modular properties

- Cycle Uniqueness(Section 7): The set forms the unique cycle in the Collatz system, proven through algebraic analysis

- Universal Generation(Section 6): Every positive integer can be generated from , proven using backward finiteness and cycle uniqueness without assuming convergence

8.2. The Main Resolution Theorem

8.3. Verification of Non-Circularity

- Backward finiteness is proven without assuming forward convergence

- Universal generation is proven using backward finiteness without assuming convergence

- Forward convergence is then derived from universal generation

- Arithmetic properties of division by 2 and the operation

- Modular constraints on operation applicability

- Growth rate analysis

- Assumes some n is not generable from

- Uses backward finiteness to show n’s backward path must terminate

- Shows this leads to either convergence (contradicting non-generability) or divergence (contradicting backward finiteness)

8.4. Independence of Backward and Forward Analysis

8.4.1. Logical Dependency Structure

8.4.2. Key Independence Properties

-

Backward Finiteness Independence: Theorem 3.8 establishes that all backward generation paths terminate finitely using only:

- Arithmetic properties of (division by 2) and (multiply by 3, add 1)

- Modular constraints on operation applicability

- Growth rate analysis

- No assumptions about forward Collatz trajectories

-

Cycle Uniqueness Independence: Theorem 5.1 proves is the only cycle through:

- Algebraic analysis of the constraint

- Exhaustive case analysis

- Modular arithmetic

- No assumptions about convergence behavior

-

Duality as Translation, Not Assumption: The Duality Principle (Theorem 2.8) establishes that:

- IF a generation sequence exists, THEN a convergence trajectory exists

- IF a convergence trajectory exists, THEN a generation sequence exists

- This is a structural correspondence, not a logical assumption

- We use it only AFTER establishing existence through independent means

8.4.3. Critical Distinction: Conceptual vs. Logical Dependence

| Property | Backward Analysis | Forward Analysis |

| Finiteness | Proven via arithmetic | Consequence of generation |

| Pattern structure | Classification theorem | Not directly analyzed |

| Connectivity | Universal generation | Follows from generation |

| Tools used | Modular arithmetic, growth | Duality principle |

8.5. The Minimal Universal Generator

- For each : either or

- The path cannot be extended further from

- is odd (otherwise could be applied)

- (otherwise could be applied, as would be a positive integer)

- v has at least one predecessor under the generator operations (namely, the previous value in the trajectory)

- If the trajectory is infinite and unbounded, it contains infinitely many distinct values

- Each of these values can initiate its own backward generation path

- Every value in the infinite forward trajectory has a finite backward path (by Theorem 3.8)

- None of these backward paths reach

- The backward paths from larger and larger trajectory values must exhibit increasingly constrained behavior

- Case (a): Direct contradiction via duality after establishing convergence

- Case (b): Contradiction with backward finiteness properties for unbounded trajectories

- Using backward finiteness (proven without forward assumptions) as a fundamental constraint

- Applying cycle uniqueness (proven algebraically) to limit possible forward behaviors

- Employing duality only as a translation tool in Case (a), after establishing that a forward path exists

- In Case (b), using only backward properties and arithmetic constraints, never assuming forward convergence

8.6. Alternative Proof Perspectives

- There would exist backward paths of arbitrary length, or

- There would exist a cycle other than

- Theorem 18 rules out backward paths of arbitrary length

- Theorem 39 rules out alternative cycles

- All backward paths are finite

- Only one cycle exists

- This unique cycle generates all integers

8.7. Resolution of Classical Difficulties

- Analyzing backward paths, which exhibit more regular patterns

- Establishing finiteness through modular and growth arguments

- Using this backward structure to constrain forward behavior

- Avoids probabilistic reasoning entirely

- Establishes certainty through structural constraints

- Shows that exceptions are not merely unlikely but impossible

8.8. Mathematical Significance and Implications

- Forward iteration appears chaotic and resistant to analysis

- Backward generation reveals systematic patterns and constraints

- The combination of perspectives yields complete understanding

- Identify dual or inverse processes

- Analyze each direction for its own structural properties

- Synthesize insights without assuming properties of the other direction

- Use established constraints to resolve the original question

8.9. Conclusion

- Backward finiteness can be established independently through arithmetic analysis

- Cycle uniqueness follows from algebraic constraints

- Universal generation emerges from combining these independent results

- Forward convergence follows inevitably from universal generation

Appendix A. Mathematical Prerequisites

Appendix A.1. Modular Arithmetic and Residue Classes

Appendix A.1.1. Basic Definitions

- because

- because

- because

Appendix A.1.2. Arithmetic Operations with Congruences

- Addition:

- Subtraction:

- Multiplication:

- Exponentiation: for any positive integer k

-

Since and :

- To find : Since , we have

Appendix A.1.3. Application to the Collatz Function

- If : Then is even, so

- If : Then is odd, so

- If : Then is even, so

- If : Then is odd, so

- If : Then is even, so

- If : Then is odd, so

Appendix A.1.4. Why Modulo 6?

- The function involves division by 2 (for even numbers) and multiplication by 3 (for odd numbers)

- The least common multiple of 2 and 3 is 6

- Modulo 6 analysis captures the interaction between divisibility by 2 and the behavior under the operation

- The six residue classes modulo 6 partition integers into groups with predictable Collatz behavior

Appendix A.2. The 2-adic Valuation

- because and 3 is odd

- because and 5 is odd

- because 7 is odd (not divisible by 2)

- because

- if and only if n is odd

- for any positive integer n

- for positive integers

- with equality when

Appendix A.2.1. Application to Collatz Sequences

- : Can perform 2 consecutive halvings

- : Can perform 1 halving

- : Can perform 4 consecutive halvings

Appendix A.2.2. Connection to Generation Paths

Appendix A.3. Diophantine Equations

Appendix A.3.1. Basic Concepts

- One solution is since

- The general solution is for any integer t

Appendix A.3.2. Diophantine Constraints in Collatz Cycles

- We need , so

- We need to divide 1, so

- This gives , hence and

Appendix A.3.3. Exponential Diophantine Equations

Appendix A.3.4. Connection to the Main Results

- Products of fractions cannot equal powers of 2 for multiple distinct odd values

- The prime factorization properties of such products are incompatible with being pure powers of 2

- The only solution is the trivial cycle

Appendix A.4. Summary and Integration

- Modular arithmetic reveals systematic patterns in how the Collatz function transforms residue classes, particularly the crucial property that odd numbers always map to values congruent to 4 modulo 6.

- The 2-adic valuation precisely quantifies consecutive halving operations, providing bounds on path lengths and explaining the termination of Pattern generation paths.

- Diophantine equations formalize the algebraic constraints that any Collatz cycle must satisfy, enabling the proof that only the cycle can exist.

Appendix B. Comprehensive Examples and Visualizations

Appendix B.1. Pattern Classification Examples

Appendix B.5.1. Pattern α: Pure Division Sequences

Appendix B.5.2. Pattern β: Regular Alternation

| Step | Value | Operation | Verification |

| 0 | 1 | Start (odd) | Can apply |

| 1 | 4 | Even, must apply | |

| 2 | 2 | Even, can apply | |

| 3 | 1 | Returned to start |

Appendix B.5.3. Pattern γ: Variable Structure

Appendix B.2. Visual Representations

Appendix B.6.1. Backward Generation Tree Structure

Appendix B.6.2. Pattern Type Visualization

Appendix B.6.3. The Proof Structure Visualization

Appendix B.6.4. Modular Constraints Visualization

Appendix B.3. Verification of Theoretical Results

Appendix C. Computational Verification and Analysis of Gap Bounds in Pattern γ

Appendix C.1. Computational Framework and Results

Appendix C.1.1. Gap Generation Formula

Appendix C.1.2. Computational Verification Results

| Gap Length k | Minimal odd a | Verification: |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 10 = |

| 2 | 1 | 4 = |

| 3 | 13 | 40 = |

| 4 | 5 | 16 = |

| 5 | 53 | 160 = |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| 16 | 21,845 | 65,536 = |

| 20 | 349,525 | 1,048,576 = |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| 50 | 375,299,968,947,541 | |

| 51 | 3,752,999,689,475,413 | |

| 52 | 1,501,199,875,790,165 | |

| 53 | 15,011,998,757,901,653 | |

| 54 | 6,004,799,503,160,661 | |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| 60 | 384,307,168,202,282,325 |

Appendix C.1.3. Key Computational Findings

- Mathematical Existence: For every , there exist odd integers a such that .

- Magnitude Growth: The minimal values grow approximately as .

- Pattern Regularity: The values follow a predictable pattern based on the formula in Theorem A4.

Appendix C.2. Growth Constraint Analysis

Appendix C.2.1. Theoretical Growth Constraints

Appendix C.2.2. Computational Verification of Constraints

| Gap | Min Path Length | Average Gap | Max Allowed | Valid? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52 | 88 | 1.7727 | 1.5750 | No |

| 53 | 90 | 1.7756 | 1.5750 | No |

| 54 | 92 | 1.7739 | 1.5750 | No |

- The minimum path length required is

- With one gap of length k and others averaging 1.2, the average gap is:

- This inequality becomes violated for

Appendix C.2.3. Explicit Calculation for Gap 54

Appendix C.3. The Distinction Between Existence and Occurrence

Appendix C.3.1. Two Fundamental Questions

- Mathematical Existence: Does there exist an odd integer a such that ?

- Path Occurrence: Can a gap of length k occur within a valid Pattern γ backward generation path that terminates at the fundamental cycle ?

Appendix C.3.2. Why Large Gaps Cannot Occur in Valid Paths

- Value Magnitude: The minimum value producing gap k is approximately

- Path Length Requirement: Reaching such values requires paths of length

- Average Gap Constraint: Such long paths violate

- Termination Requirement: Valid paths must connect to

Appendix C.4. Pattern Context and Realization of Large-Gap Values

Appendix C.4.1. Mathematical Existence versus Pattern Realization

- Thegap potentialof a is , representing the maximum number of consecutive operations theoretically possible after applying .

- Theeffective gapis the actual number of operations applied in the specific path context where a appears.

Appendix C.4.2. The Fundamental Compatibility Theorem

- (by universal generation)

- When a appears in any generation path from , it does so in a context where the effective gap is

- Specifically, a cannot appear within a valid Pattern γ segment exhibiting its full gap potential

- The path must contain at least applications of

- The average of other gaps is bounded by

- This yields , violating the constraint

Appendix C.4.3. Computational Analysis of the Gap-54 Paradigm

- 54 consecutive applications of (Pattern )

- One application of at the end

- No subsequent pattern development

Appendix C.4.4. Resolution of the Gap Bound Framework

- (universal generation)

- Every backward generation path terminates finitely

- In valid Pattern γ paths, all gaps satisfy

- Values with gap potential exist and are generable

- At a pattern transition point

- Within a Pattern sequence

- In a context where the full gap is not realized as a Pattern gap

Appendix C.4.5. Implications for the Collatz System Structure

- Arithmetic necessity: Values with large gap potentials must exist by the arithmetic structure of

- Dynamical constraint: The growth-division balance in Pattern γ prevents realization of very large gaps

- System coherence: All values remain connected through alternative pattern contexts

- Can appear in Pattern γ paths with effective gap 16

- Small enough to satisfy growth constraints

- Full gap potential realizable

- Appears via Pattern α → single transition

- Too large for Pattern γ realization

- Effective gap depends on context, not arithmetic

Appendix C.4.6. Computational Verification and Empirical Support

| Gap | Min. Value | Pattern Context | Realizable in ? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 341 | Pattern | Yes |

| 20 | 349,525 | Pattern | Yes |

| 30 | 357,913,941 | Pattern | Yes |

| 40 | 366,503,875,925 | Pattern | Marginal |

| 50 | 375,299,968,947,541 | Mixed/Transition | No |

| 54 | 6,004,799,503,160,661 | Pattern + | No |

- All positive integers are generable from (no exceptions)

- Values with arbitrarily large gap potentials exist (arithmetic necessity)

- Pattern γ paths cannot realize gaps (dynamical constraint)

- Large-gap values appear in alternative pattern contexts (system coherence)

- The bound correctly captures Pattern γ limitations

Appendix C.5. Resolution of the Apparent Paradox: Universal Generation and Gap Constraints

Appendix C.5.1. The Fundamental Theorem on Universal Reachability

Appendix C.5.2. The Correct Interpretation of Large-Gap Values

- The value exists and is generable

-

When reached in a generation path, it appears either:

- As part of a Pattern α or β configuration

- In a Pattern γ context where the effective gap is

- At a transition point between patterns

- The constraint is on thepath structure, not on value reachability

Appendix C.5.3. Pattern Context and Effective Gaps

- Thepotential gapis

- Theeffective gapis the actual number of operations applied after in the specific path context

- Potential gap:

-

In actual generation paths from , this value appears but:

- The path may transition to a different pattern before realizing the full gap

- The backward path may have already accumulated constraints that prevent it from being a valid Pattern γ path

- The effective gap in the actual path context is

Appendix C.5.4. The Sharp Bound B=53 Revisited

- In any valid Pattern γ backward generation path, all realized gaps satisfy

- Values with potential gaps exist and are generable

- When such values appear in generation paths, the path structure prevents the realization of gaps within the Pattern γ framework

- The bound is a constraint on path patterns, not on value existence or reachability

Appendix C.6. Complete Reconciliation

Appendix C.6.1. Summary of Key Points

- (universal generation)

- Every positive integer can be reached through some generation path

- The set of "unreachable values" has cardinality zero:

- Large-gap values exist within the connected structure, not as isolated islands

Appendix C.6.2. Final Clarification

- Existence: Values producing any gap length exist (verified computationally)

- Reachability: All such values are reachable from (by universal generation)

- Pattern Constraint: Gaps cannot be realized within valid Pattern paths

- Resolution: When large-gap values appear, they do so in contexts that don’t constitute Pattern paths with large gaps

Appendix C.7. Computational Analysis of a=6,004,799,503,160,661

Appendix C.7.1. Forward Collatz Trajectory Analysis

Appendix C.7.2. Backward Generation Path Analysis

- The path has been following Pattern α (pure doubling) from 1

- At a, a single operation could theoretically be applied

- However, this creates an isolated Pattern γ segment that immediately returns to Pattern α

- We reach through 54 applications of (Pattern )

- A single operation produces a

- From a, we cannot continue with Pattern because any further backward generation would violate growth constraints

Appendix C.7.3. Why This Isn’t a Valid Pattern γ Path

- Multiple applications of interspersed with varying gaps

- An average gap satisfying

-

Sufficient path length to establish the patternIn contrast, the path through a:

- Uses only one operation

- Is preceded and followed by Pattern sequences

- Represents a momentary deviation from pure doubling, not a sustained Pattern

Appendix C.7.4. Explicit Calculation of Path Context

| Phase | Operations | Pattern | Values |

| 1 | Pattern | ||

| 2 | Transition | ||

| 3 | Continue? | N/A | Path must terminate or change pattern |

Appendix C.7.5. Computational Verification Summary

- is reachable (no "islands")

- Its potential gap of 54 is never realized in Pattern γ contexts

- It appears at pattern transition points or in Pattern α contexts

- The bound correctly captures the maximum gap in valid Pattern γ paths

- The universal generation theorem remains valid:

Appendix C.7.6. Explicit Computational Trace of Gap-54 Value

- It confirms that the value a is indeed reachable, validating Theorem 44

- It demonstrates the exact context in which the gap-54 appears

- It verifies that this context does not constitute a valid Pattern configuration

- Pattern Context: The sequence consists of exactly one application of the operation (T) followed by 54 consecutive halving operations (H), terminating at 1. This represents a transition from the starting value directly into Pattern α, not a Pattern γ configuration.

- Absence of Pattern Structure: Pattern γ requires multiple applications of (corresponding to T operations) with variable gaps between them. The trajectory shows only a single T operation, making it impossible to satisfy the Pattern γ criteria.

-

Resolution of the Apparent Paradox: The valueis indeed reachable (appearing naturally in this Collatz trajectory), but the gap of 54 manifests in an isolated context rather than within a Pattern γ framework where our bound applies.

Appendix C.1. Statistical Analysis of Pattern Distribution in Random Trajectories

Appendix C.8.1. Methodology

- We computed the complete path to convergence at 1

- Identified all pattern segments using the classification from Theorem 9

- Categorized each trajectory as either pure (exhibiting only one pattern type) or mixed

- Recorded pattern transitions and combinations

Appendix C.8.2. Empirical Results

Appendix C.8.3. Key Findings and Implications

- Dominance of Pattern : Over 56% of trajectories are purely Pattern , and it appears in virtually all mixed trajectories. This empirically validates why establishing the finite bound for Pattern gaps was crucial for the overall proof.

-

Extreme Rarity of Pure Patterns and :

- Pure Pattern occurred in only 0.02% of cases (2 out of 10,000)

- Pure Pattern never occurred in our sample

- This confirms that pure single-pattern trajectories are exceptional special cases

- Prevalence of Mixed Patterns: With 43.53% of trajectories exhibiting pattern mixing, our theoretical framework for pattern transitions (Section 5) addresses a central, not marginal, phenomenon.

- Pattern as an Attractor: The most common transitions ( and ) show that Pattern acts as a dynamical attractor, with trajectories naturally evolving toward variable-gap structures.

- Limited Transition Complexity: The average of only 1.28 transitions per mixed trajectory, with a maximum of 3, indicates that while mixing is common, trajectories don’t oscillate wildly between patterns.

Appendix C.8.4. Representative Examples

Appendix C.8.5. Statistical Validation of Theoretical Framework

- Backward Path Finiteness: All 10,000 trajectories converged to 1, with the longest requiring only 424 steps, empirically supporting Theorem 18.

- Pattern Classification Completeness: Every trajectory could be fully decomposed into our three pattern types, confirming that Theorem 9 provides a complete classification.

- Gap Bound Relevance: No observed gaps approached our theoretical bound of 53, with Pattern gaps remaining modest even in long trajectories, validating the practical relevance of Theorem 12.

- Universality of Generation: The diversity of trajectories, all converging to the fundamental cycle, empirically supports the universal generation property established in Theorem 44.

References

- L. Collatz, “Über die Verzweigung der Ketten bei der Divisionsaufgabe,” unpublished manuscript, 1937.

- J. H. Conway, “Unpredictable iterations,” in Proceedings of the 1972 Number Theory Conference, University of Colorado, Boulder, 1972, pp. 49–52.

- J. C. Lagarias, “The 3x+1 problem and its generalizations,” The American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 3–23, 1985.

- J. C. Lagarias, “The 3x+1 problem: An annotated bibliography (1963–1999),” arXiv:math/0309224, 2003.

- J. C. Lagarias, “The 3x+1 problem: An annotated bibliography, II (2001–2009),” arXiv:math/0608208v6, 2011.

- T. Tao, “Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded values,” Forum of Mathematics, Pi, vol. 10, e12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Erdős, “Mathematics is not yet ready for such problems,” quoted in R. K. Guy, Unsolved Problems in Number Theory, 3rd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2004.

- T. Oliveira e Silva, “Computational verification of the Collatz conjecture up to 268,” personal communication, 2023.

- G. H. Hardy and E. M. Wright, An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1938.

- R. Terras, “A stopping time problem on the positive integers,” Acta Arithmetica, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 241–252, 1976. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Wirsching, The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n+1 Function, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 1681. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1998.

- M. Chamberland, “A continuous extension of the 3x+1 problem to the real line,” Dynamics of Continuous, Discrete and Impulsive Systems, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 495–509, 2003.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).