Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

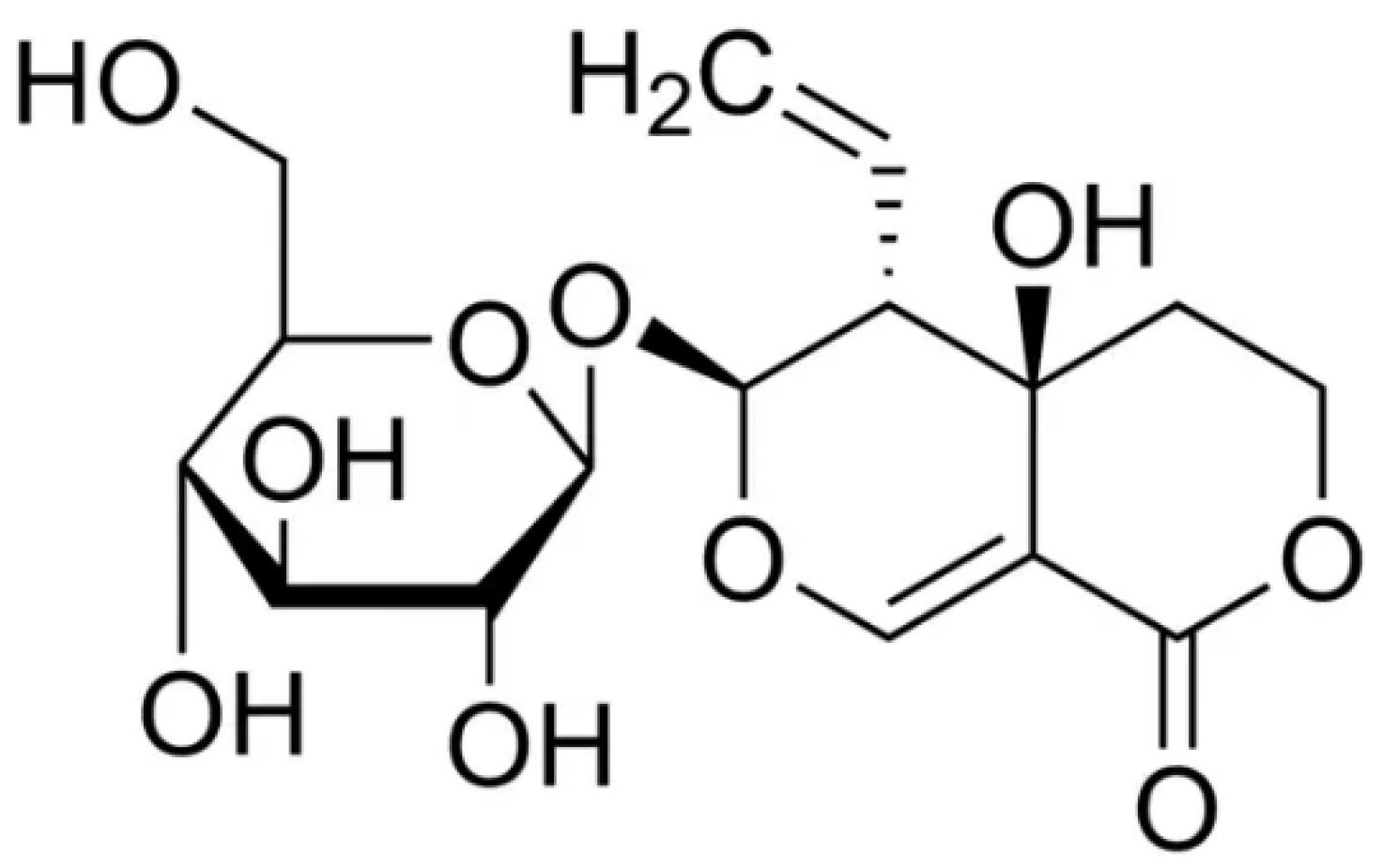

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pharmacokinetic properties

3. Pharmacological Effects

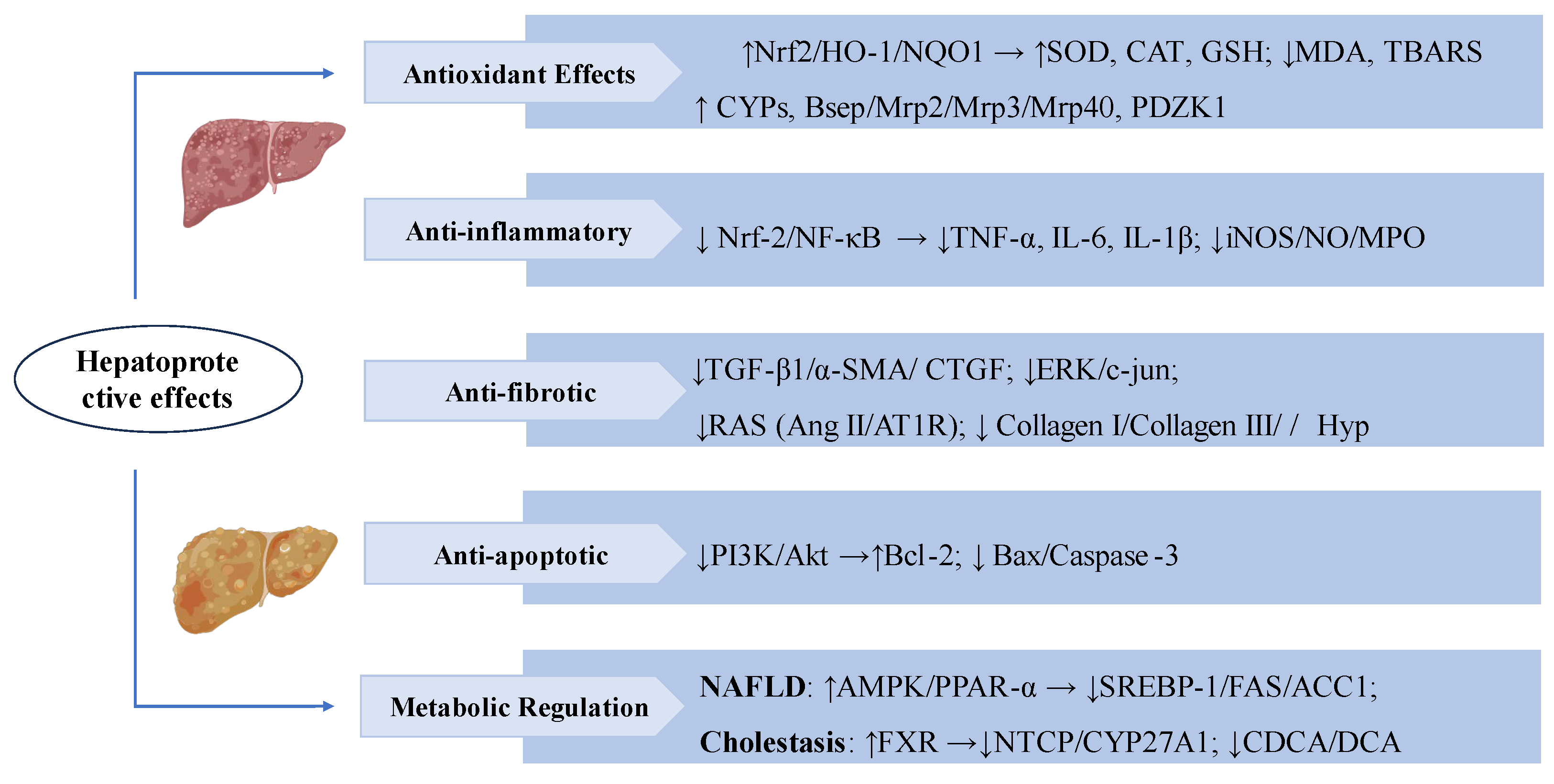

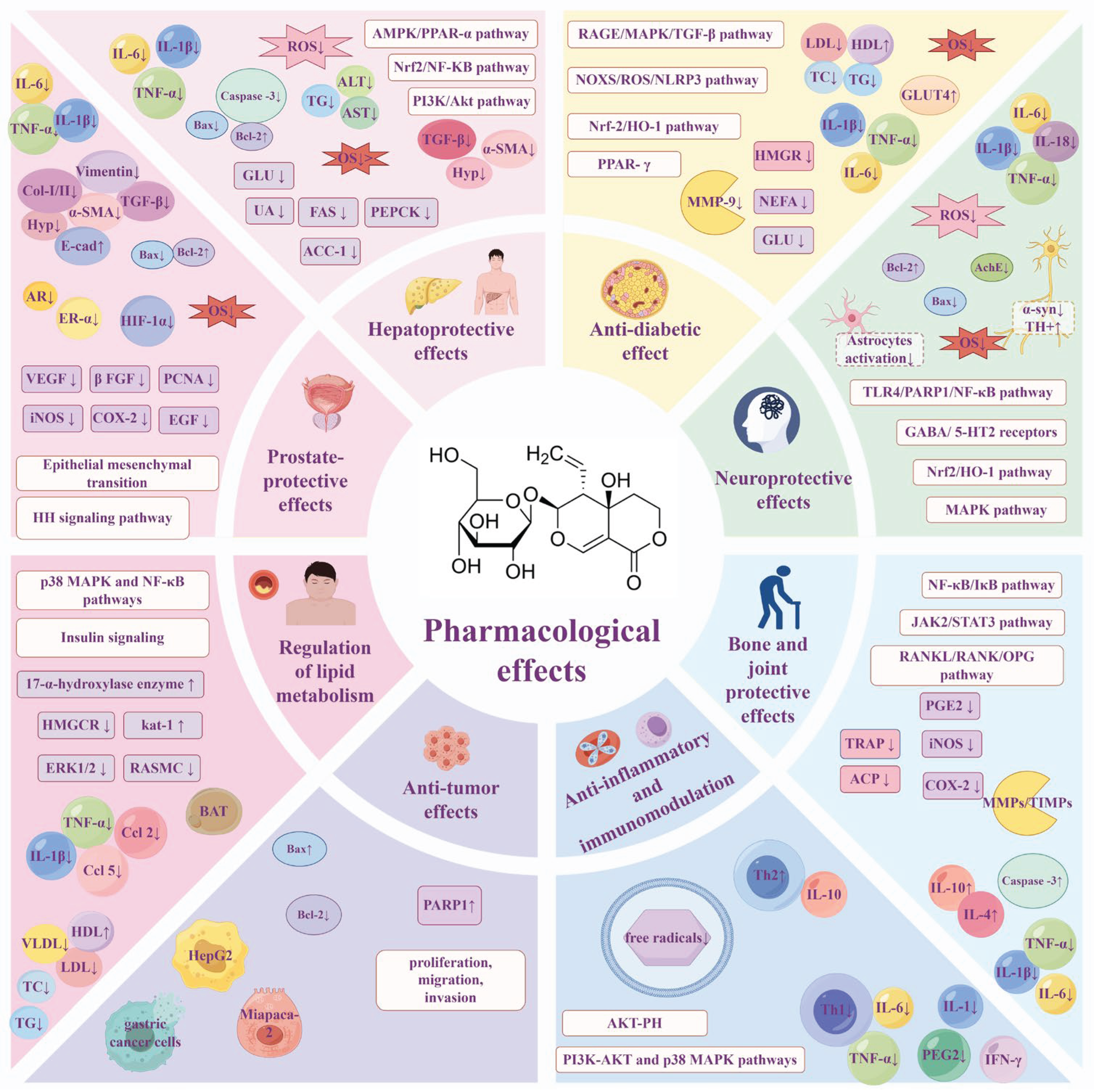

3.1. Hepatoprotective Effects

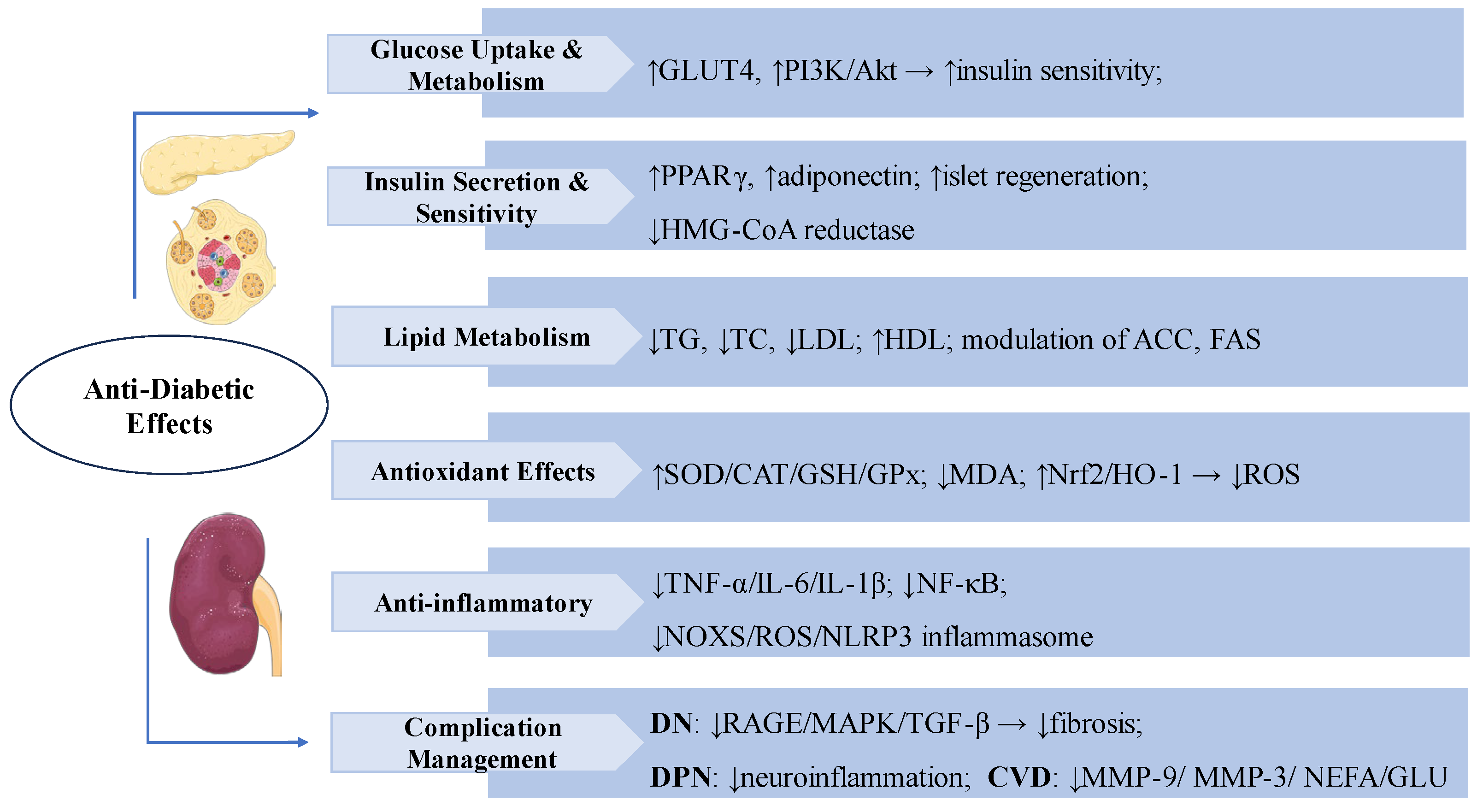

3.2. Anti-Diabetic Effects

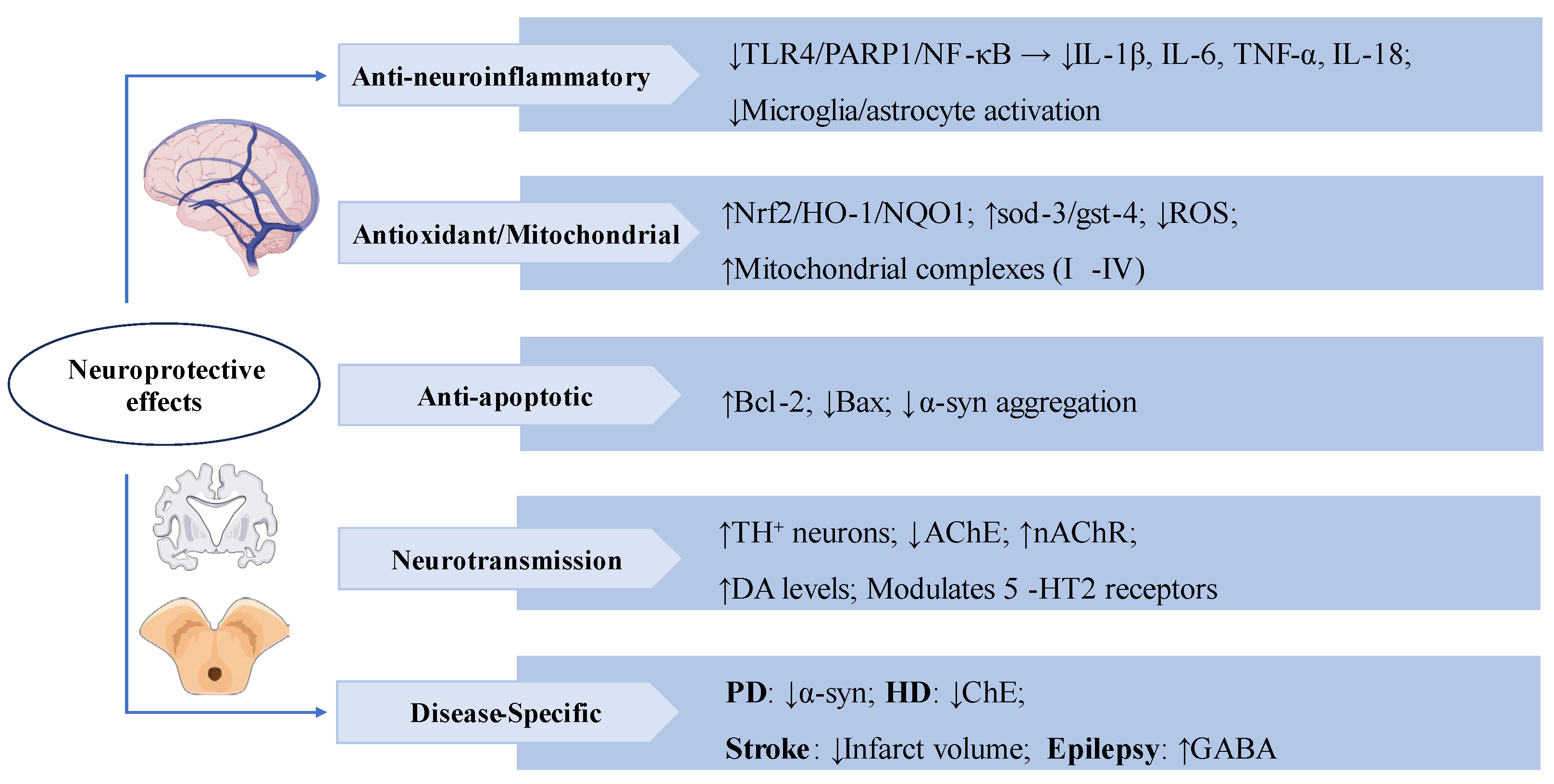

3.3. Neuroprotective Effects

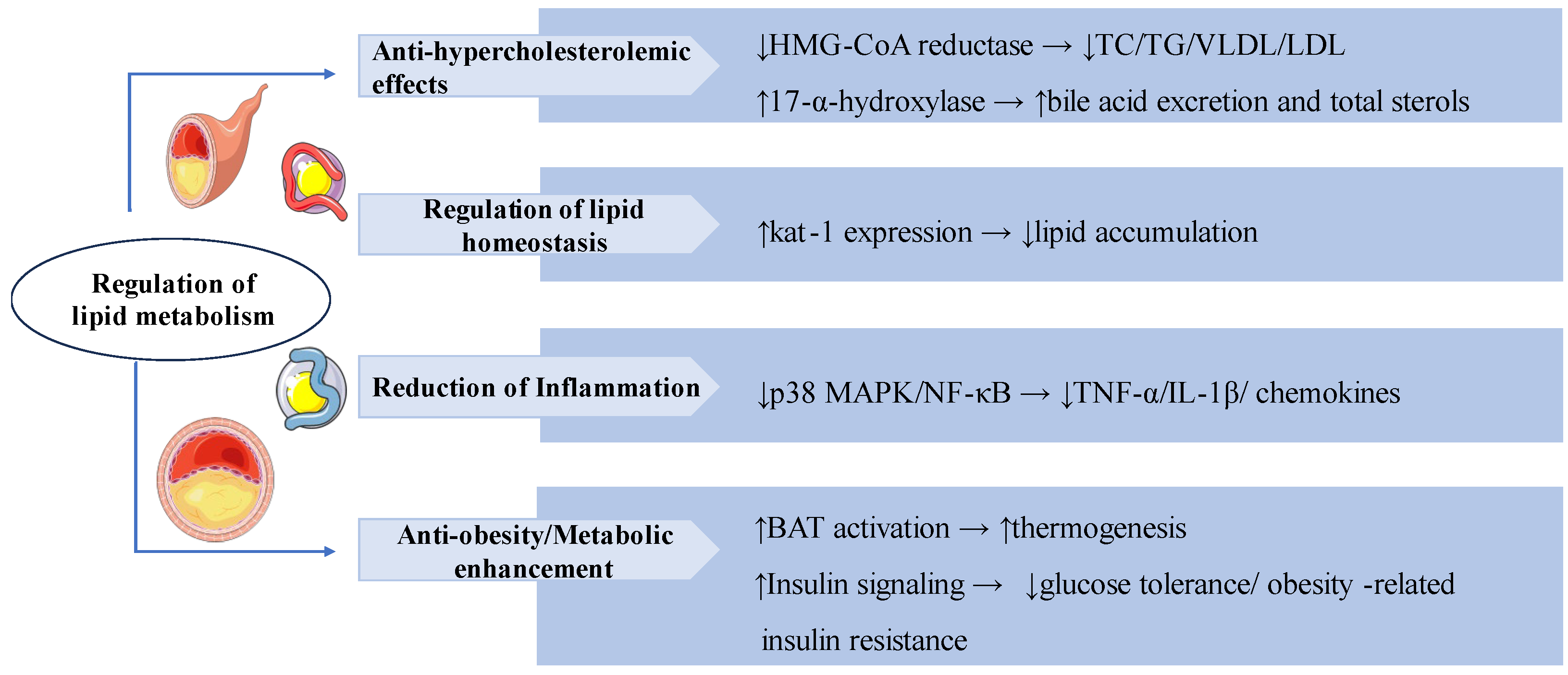

3.4. Regulation of Lipid Metabolism

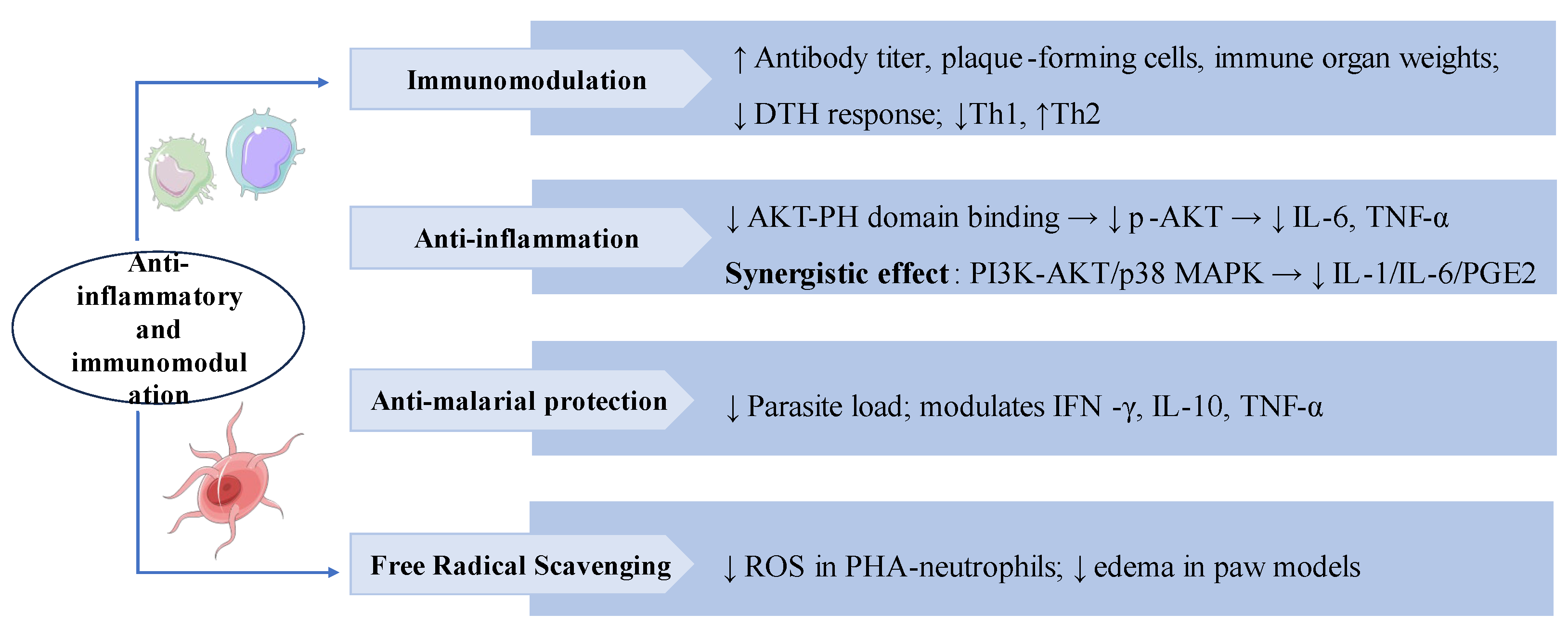

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulation

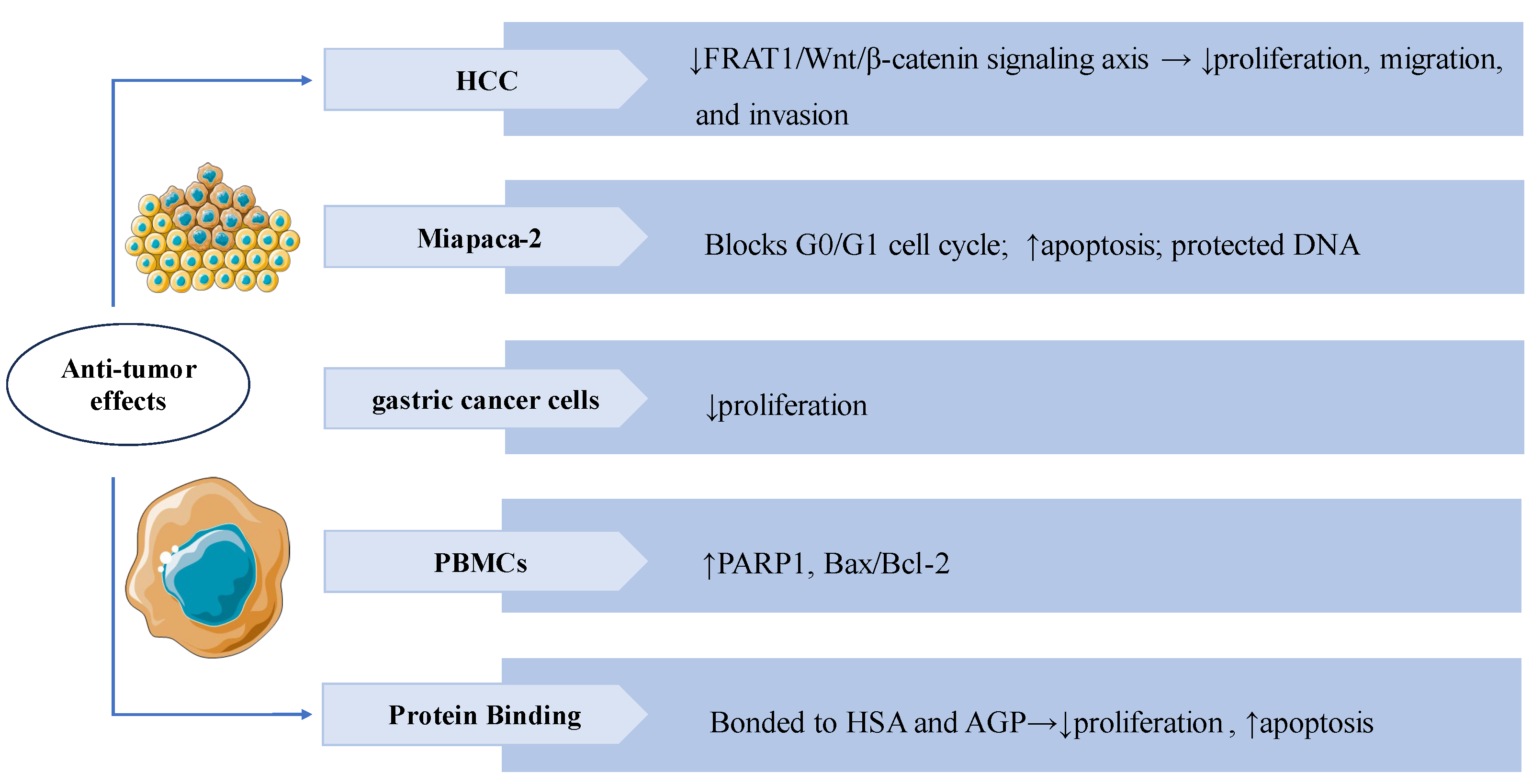

3.6. Anti-Tumor Effects

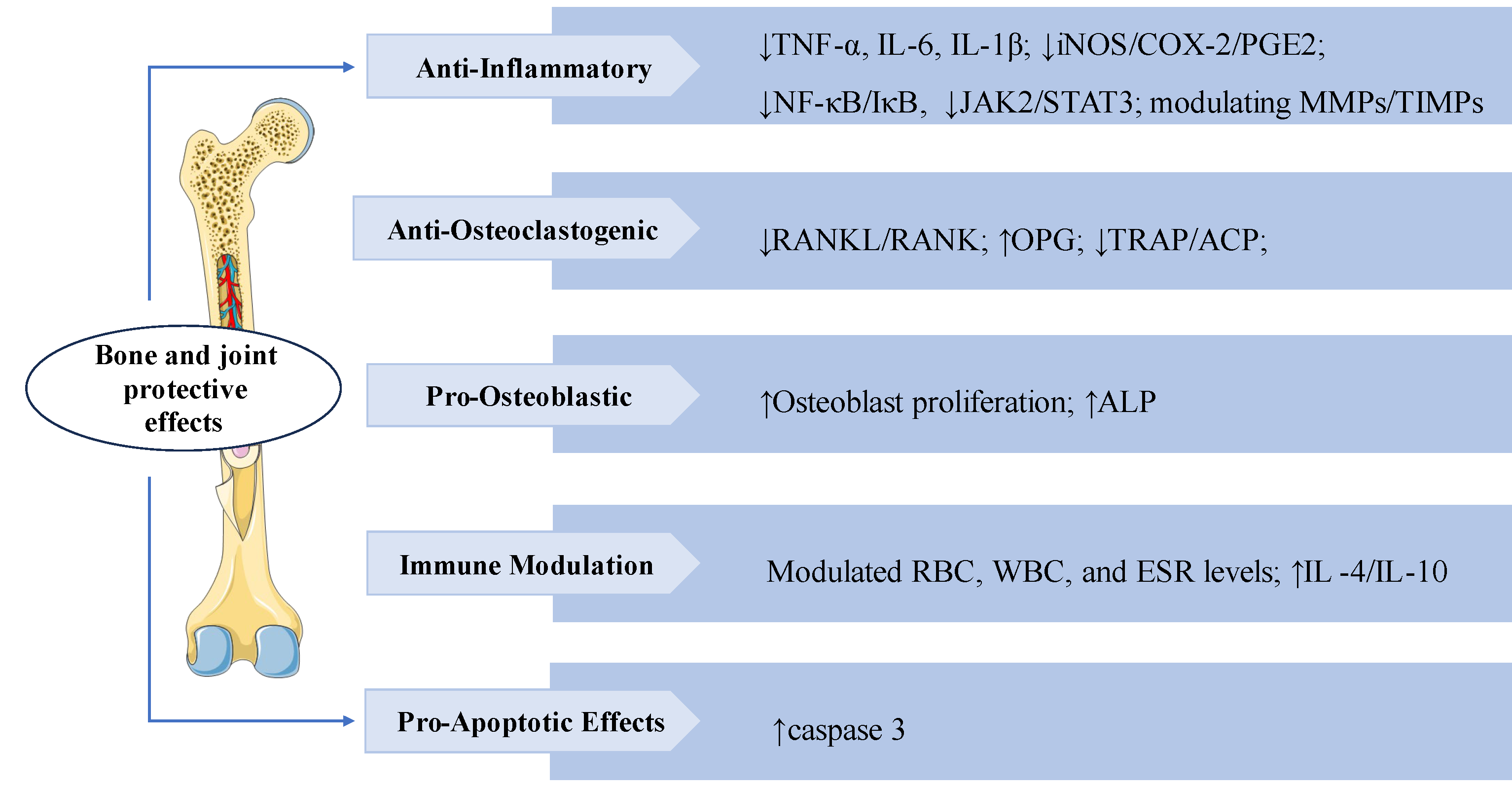

3.7. Bone and Joint Protective Effects

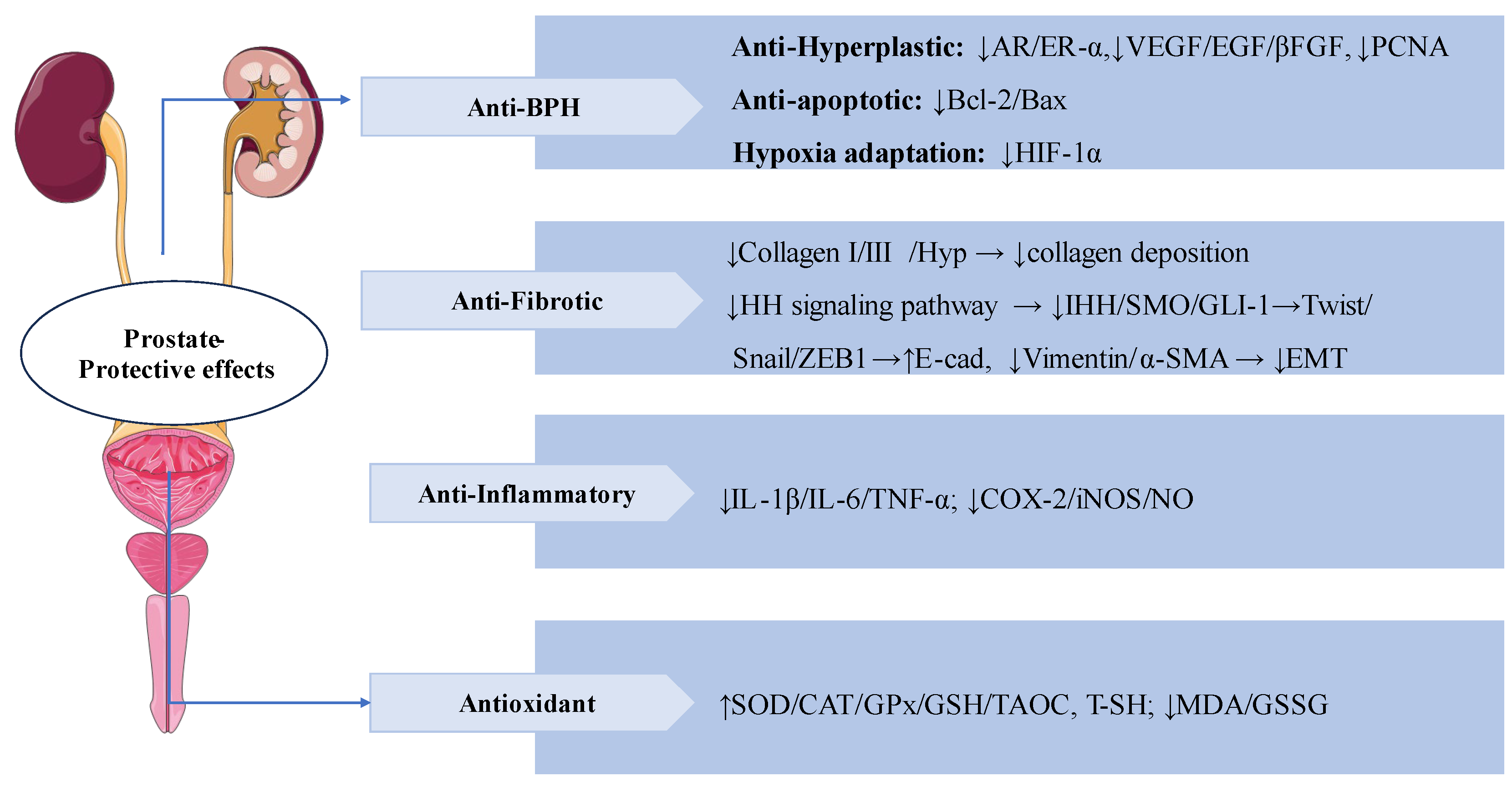

3.8. Prostate-Protective Effects

3.9. Other Therapeutic Effects

4. Toxicology

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Declaration of competing interest

Funding

References

- Chi, X.; Zhang, F.; Gao, Q.; Xing, R.; Chen, S. A Review on the Ethnomedicinal Usage, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties of Gentianeae (Gentianaceae) in Tibetan Medicine. Plants 2021, 10, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Gadimli, A.I.; Isaev, J.I.; Kashchenko, N.I.; Prokopyev, A.S.; Kataeva, T.N.; Chirikova, N.K.; Vennos, C. Caucasian Gentiana Species: Untargeted LC-MS Metabolic Profiling, Antioxidant and Digestive Enzyme Inhibiting Activity of Six Plants. Metabolites 2019, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Zhang, J.; Su, H.; Yang, Q.; Wulu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, Z. Comparative analysis of phytochemical profile and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of four Gentiana species from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 326, 117926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, G.; Thamotharan, G.; Sengottuvelu, S.; Narmatha Bai, V. RETRACTED: Anti-diabetic activity of Swertia corymbosa (Griseb.) Wight ex C.B. Clarke aerial parts extract in streptozotocin induced diabetic. Diabet. rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoboo, S.; Pinto Mda, S.; Barbosa, A.C.; Sarkar, D.; Bhowmik, P.C.; Jha, P.K.; Shetty, K. Phenolic-linked biochemical rationale for the anti-diabetic properties of Swertia chirayita (Roxb. ex Flem.) Karst. Phytother. Res.: PTR 2013, 27, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.B.; Mishra, S.H. Hypoglycemic activity of C-glycosyl flavonoid from Enicostemma hyssopifolium. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, H.; Bhatnagar, D. Amelioration of oxidative and inflammatory changes by Swertia chirayita leaves in experimental arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2016, 24, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudecová, A.; Kusznierewicz, B.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Magdolenová, Z.; Hasplová, K.; Rinna, A.; Fjellsbø, L.M.; Kruszewski, M.; Lankoff, A.; Sandberg, W.J.; Refsnes, M.; Skuland, T.; Schwarze, P.; Brunborg, G.; Bjøras, M.; Collins, A.; Miadoková, E.; Gálová, E.; Dusinská, M. Silver nanoparticles induce premutagenic DNA oxidation that can be prevented by phytochemicals from Gentiana asclepiadea. Mutagenesis 2012, 27, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Yi, X.J.; Huang, X.J.; Muhammad, A.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Yang, G.Z.; Gao, Y. Hepatoprotective activity of iridoids, seco-iridoids and analog glycosides from Gentianaceae on HepG2 cells via CYP3A4 induction and mitochondrial pathway. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 2673–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, V.; Katanić, J.; Mišić, D.; Stanković, V.; Mihailović, M.; Uskoković, A.; Arambašić, J.; Solujić, S.; Mladenović, M.; Stanković, N. Hepatoprotective effects of secoiridoid-rich extracts from Gentiana cruciata L. against carbon tetrachloride induced liver damage in rats. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Tyagi, R.K.; Tandel, N.; Garg, N.K.; Soni, N. The Molecular Targets of Swertiamarin and its Derivatives Confer Anti- Diabetic and Anti-Hyperlipidemic Effects. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 19, 1958–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.P.; Sashidhara, K.V. Lipid lowering agents of natural origin: An account of some promising chemotypes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 140, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, X.Y.; Thanikachalam, P.V.; Pandey, M.; Ramamurthy, S. A systematic review of the protective role of swertiamarin in cardiac and metabolic diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. = Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.L.; Peng, X.J.; He, J.C.; Feng, E.F.; Xu, G.L.; Rao, G.X. Development and validation of a LC-ESI-MS/MS method for the determination of swertiamarin in rat plasma and its application in pharmacokinetics. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2011, 879, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; He, J.C.; Bai, M.; Song, Q.Y.; Feng, E.F.; Rao, G.X.; Xu, G.L. Determination of the plasma pharmacokinetic and tissue distributions of swertiamarin in rats by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Arzneim. -Forsch. 2012, 62, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.M.; Lin, L.C.; Tsai, T.H. Determination and pharmacokinetic study of gentiopicroside, geniposide, baicalin, and swertiamarin in Chinese herbal formulae after oral administration in rats by LC-MS/MS. Molecules 2014, 19, 21560–21578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong-Li, W.; Cong-Cong, Z.; Feng, Z.; Jian, H.; Dan-Dan, W.; Yong-Fang, Z.; Wei, L.; Guang-Bo, G.E.; Jian-Guang, X.U. [Chemical profiling and tissue distribution study of Jingyin Granules in rats using UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HR-MS]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi = Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi = China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2020, 45, 5537–5554. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.L.; Li, H.L.; He, J.C.; Feng, E.F.; Shi, P.P.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, C.X. Comparative pharmacokinetics of swertiamarin in rats after oral administration of swertiamarin alone, Qing Ye Dan tablets and co-administration of swertiamarin and oleanolic acid. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 149, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ai, Y.; Wang, F.; Ma, W.; Bian, Q.; Lee, D.Y.; Dai, R. Simultaneous determination of four secoiridoid and iridoid glycosides in rat plasma by ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and its application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study. Biomed. Chromatogr. BMC 2016, 30, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, T.; Han, H. Metabolite Profiling of Swertia cincta Extract in Rats and Pharmacokinetics Study of Three Bioactive Compounds Using UHPLC-MS/MS. Planta Medica 2023, 89, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhu, H.; Guan, J.; Zhao, L.; Gu, J.; Yin, L.; Fawcett, J.P.; Liu, W. A rapid and sensitive UFLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of gentiopicroside and swertiamarin in rat plasma and its application in pharmacokinetics. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, N.; Zhi, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Pharmacokinetic and excretion study of three secoiridoid glycosides and three flavonoid glycosides in rat by LC-MS/MS after oral administration of the Swertia pseudochinensis extract. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2014, 967, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Wang, X.J.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Ma, C.M. Determination of novel nitrogen-containing metabolite after oral administration of swertiamarin to rats. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 14, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, H.; Goyal, R.K.; Cheema, S.K. Anti-diabetic activity of swertiamarin is due to an active metabolite, gentianine, that upregulates PPAR-γ gene expression in 3T3-L1 cells. Phytother. Res.: PTR 2013, 27, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Liu, C.; Han, Z.Z.; Han, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.T. Microbial Biotransformation of Iridoid Glycosides from Gentiana Rigescens by Penicillium Brasilianum. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Highly sensitive determination of new metabolite in rat plasma after oral administration of swertiamarin by liquid chromatography/time of flight mass spectrometry following picolinoyl derivatization. Biomed. Chromatogr.: BMC 2014, 28, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Tang, S.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hattori, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. New analytical method for the study of metabolism of swertiamarin in rats after oral administration by UPLC-TOF-MS following DNPH derivatization. Biomed. Chromatogr.: BMC 2015, 29, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Xiong, K.; Zhang, T.; Han, H. Pharmacokinetics and metabolic profiles of swertiamarin in rats by liquid chromatography combined with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 179, 112997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Lou, T.; Wang, T.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Yu, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Comprehensive metabolism study of swertiamarin in rats using ultra high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with Quadrupole-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Xenobiotica; Fate Foreign Compd. Biol. Syst. 2021, 51, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishree, V.; Badami, S. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effect of swertiamarin from Enicostemma axillare against D-galactosamine induced acute liver damage in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Song, H. Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effect of Swertiamarin on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatotoxicity via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. : Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 41, 2242–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xiao, S.; Dai, X.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ali, M.; Ataya, F.S.; Sahar, I.; Iqbal, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, K. Multi-omics analysis and the remedial effects of Swertiamarin on hepatic injuries caused by CCl(4). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 282, 116734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, K.; Wu, T.; Song, H. Swertiamarin ameliorates carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic apoptosis via blocking the PI3K/Akt pathway in rats. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol.: Off. J. Korean Physiol. Soc. Korean Soc. Pharmacol. 2019, 23, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolure, R.; Vinaitheerthan, N.; Thakur, S.; Godela, R.; Doli, S.B.; Santhepete Nanjundaiah, M. Protective effect of Enicostemma axillare - Swertiamarin on oxidative stress against nicotine-induced liver damage in SD rats. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2024, 82, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, G.L.; Ma, X.X.; Khan, A.; Tan, W.H.; Yang, Z.Y.; Zhou, Z.H. Sweritranslactones A-C: Unusual Skeleton Secoiridoid Dimers via [4 + 2] Cycloaddition from Swertiamarin. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 13263–13267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.D.; Ma, X.X.; Du, S.N.; Qi, P.X.; He, F.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Tan, W.H.; Khan, A.; Zhou, Z.H.; Liu, L. Sweritranslactone D, a hepatoprotective novel secoiridoid dimer with tetracyclic lactone skeleton from heat-transformed swertiamarin. Fitoterapia 2021, 151, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Xia, R.; Zhang, P.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Z.; Khan, A.; Zhou, Z.; Tan, W.; Liu, L. Swertiamarin or heat-transformed products alleviated APAP-induced hepatotoxicity via modulation of apoptotic and Nrf-2/NF-κB pathways. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gea, V.; Friedman, S.L. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011, 6, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Tao, Y.; Liu, C. Swertiamarin Attenuates Experimental Rat Hepatic Fibrosis by Suppressing Angiotensin II-Angiotensin Type 1 Receptor-Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 359, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, T.G.; Rinella, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease 2020: The State of the Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1851–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, C.; He, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Qiao, B.; He, J. Amelioration of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by swertiamarin in fructose-fed mice. Phytomedicine: Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2019, 59, 152782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.P.; Rawal, K.; Soni, S.; Gupta, S. Swertiamarin ameliorates oleic acid induced lipid accumulation and oxidative stress by attenuating gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis in hepatic steatosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Chen, C.; Ziani, S.; Nelson, L.J.; Ávila, M.A.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; Cubero, F.J. Fibrotic Events in the Progression of Cholestatic Liver Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padda, M.S.; Sanchez, M.; Akhtar, A.J.; Boyer, J.L. Drug-induced cholestasis. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Tang, J.; Zhang, T.; Han, H. Swertiamarin, an active iridoid glycoside from Swertia pseudochinensis H. Hara, protects against alpha-naphthylisothiocyanate-induced cholestasis by activating the farnesoid X receptor and bile acid excretion pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 291, 115164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Shan, Q.; Jiang, L. The hepatoprotective effect and chemical constituents of total iridoids and xanthones extracted from Swertia mussotii Franch. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Du, X.; Chen, S.; Feng, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Peng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Luo, W.; Wang, R.; Chen, W.; Chai, J. Swertianlarin, an Herbal Agent Derived from Swertia mussotii Franch, Attenuates Liver Injury, Inflammation, and Cholestasis in Common Bile Duct-Ligated Rats. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med.: eCAM 2015, 2015, 948376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Gaglia, J.L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Johnson, E.L.; Khunti, K.; Lingvay, I.; Matfin, G.; Mccoy, R.G.; Perry, M.L.; Pilla, S.J.; Polsky, S.; Prahalad, P.; Pratley, R.E.; Segal, A.R.; Seley, J.J.; Selvin, E.; Stanton, R.C.; Gabbay, R.A. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S20–S42. [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane, R.D.; Deore, V.B.; Patil, S.D.; Patil, C.R.; Surana, S.J.; Goyal, R.K. Role of 5-HT2 receptors in diabetes: Swertiamarin seco-iridoid glycoside might be a possible 5-HT2 receptor modulator. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 144, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishree, V.; Narsimha, S. Swertiamarin and quercetin combination ameliorates hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus in wistar rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. = Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.P.; Soni, S.; Parikh, P.; Gosai, J.; Chruvattil, R.; Gupta, S. Swertiamarin: An Active Lead from Enicostemma littorale Regulates Hepatic and Adipose Tissue Gene Expression by Targeting PPAR- γ and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Experimental NIDDM Rat Model. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med.: Ecam 2013, 2013, 358673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Long, J.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, D. Uncovering the key pharmacodynamic material basis and possible molecular mechanism of Xiaoke formulation improve insulin resistant through a comprehensive investigation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 323, 117752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanavathy, G. Immunohistochemistry, histopathology, and biomarker studies of swertiamarin, a secoiridoid glycoside, prevents and protects streptozotocin-induced β-cell damage in Wistar rat pancreas. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2015, 38, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwani, K.; Patel, F.; Bhagwat, P.; Dilip, H.; Patel, D.; Thiruvenkatam, V.; Mandal, P. Swertiamarin mitigates nephropathy in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by inhibiting the formation of advanced glycation end products. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 130, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.L.; Cho, S.B.; Li, H.F.; ALS, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Ji, X.P.; Pan, S.; Bao, M.L.; Bai, L.; Ba, G.N.; Fu, M.H. Lomatogonium rotatum extract alleviates diabetes mellitus induced by a high-fat, high-sugar diet and streptozotocin in rats. World J. Diabetes 2023, 14, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, H.; Prajapati, A.; Rajani, M.; Sudarsanam, V.; Padh, H.; Goyal, R.K. Beneficial effects of swertiamarin on dyslipidaemia in streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. Phytother. Res.: PTR 2012, 26, 1259–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwani, K.; Patel, F.; Patel, D.; Mandal, P. Protective Effects of Swertiamarin against Methylglyoxal-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Improving Oxidative Stress in Rat Kidney Epithelial (NRK-52E) Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, R.D.; Vishwakarma, S.L.; Lakshmi, S.; Rajani, M.; Padh, H.; Goyal, R.K. Amelioration of STZ-induced type 1 diabetic nephropathy by aqueous extract of Enicostemma littorale Blume and swertiamarin in rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2010, 340, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.W.; Chen, Y.G.; Xing, N.; Lin, H.B.; Zhou, P.; Yu, X.P. Progress in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. = Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, D.; Kar, D.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J.; Scott, A.R.; Walker, J.; Tesfaye, S. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Advances in diagnosis and strategies for screening and early intervention. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yao, J.; Yao, X.; Lao, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, C.; Lu, Y. [Swertiamarin alleviates diabetic peripheral neuropathy in rats by suppressing NOXS/ ROS/NLRP3 signal pathway]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao = J. South. Med. Univ. 2021, 41, 937–941. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya, H.; Giri, S.; Jain, M.; Goyal, R. Decrease in serum matrix metalloproteinase-9 and matrix metalloproteinase-3 levels in Zucker fa/fa obese rats after treatment with swertiamarin. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2012, 17, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Malim, F.M.; Goswami, A.; Sharma, N.; Juvvalapalli, S.S.; Chatterjee, S.; Kate, A.S.; Khairnar, A. Neuroprotective Effect of Swertiamarin in a Rotenone Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Role of Neuroinflammation and Alpha-Synuclein Accumulation. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, S.F.; Elbadry, A.M.M.; Elbokhomy, A.S.; Salama, G.A.; Salama, R.M. The dual face of microglia (M1/M2) as a potential target in the protective effect of nutraceuticals against neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1231706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, T.; Smita, S.S.; Mishra, A.; Sammi, S.R.; Pandey, R. Swertiamarin, a secoiridoid glycoside modulates nAChR and AChE activity. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 138, 111010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ss, S. To Study the Effect of Swertiamarin in Animal Model of Huntington’s Disease. Open Access J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 2, 000163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Quan, J.; Su, N.; Li, P.; Yu, Q. Proteomic Analysis of Swertiamarin-treated BV-2 Cells and Possible Implications in Neuroinflammation. J. Oleo Sci. 2022, 71, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Wu, T.; Liu, L.; Song, H. Swertiamarin protects neuronal cells from oxygen glucose deprivation/reoxygenation via TLR4/PARP1/NF-κB pathway. Die Pharm. 2019, 74, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, T.; Shukla, A.; Trivedi, M.; Khan, F.; Pandey, R. Swertiamarin from Enicostemma littorale, counteracts PD associated neurotoxicity via enhancement α-synuclein suppressive genes and SKN-1/NRF-2 activation through MAPK pathway. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 108, 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Q.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Gan, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Lu, B. Pharmacological therapy to cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: Focus on saponins. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 155, 113696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wei, W.; Lan, X.; Liu, N.; Li, Y.; Ma, H.; Sun, T.; Peng, X.; Zhuang, C.; Yu, J. Neuroprotective Effect of Swertiamain on Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Inducing the Nrf2 Protective Pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 2276–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, P.S.; Ma, L.; Niu, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhou, R.; Yu, J.Q. Anticonvulsant Effect of Swertiamarin Against Pilocarpine-Induced Seizures in Adult Male Mice. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 3103–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaijanathappa, J.; Puttaswamygowda, J.; Bevanhalli, R.; Dixit, S.; Prabhakaran, P. Molecular docking, antiproliferative and anticonvulsant activities of swertiamarin isolated from Enicostemma axillare. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 94, 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, M.; Ma, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Sun, Z.; Dong, D. Anthelmintics nitazoxanide protects against experimental hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis in hamsters and mice. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1322–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, J. Mechanisms of Abnormal Lipid Metabolism in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, H.; Rajani, M.; Sudarsanam, V.; Padh, H.; Goyal, R. Swertiamarin: A lead from Enicostemma littorale Blume. for anti-hyperlipidaemic effect. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 617, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, H.; Rajani, M.; Sudarsanam, V.; Padh, H.; Goyal, R. Antihyperlipidaemic activity of swertiamarin, a secoiridoid glycoside in poloxamer-407-induced hyperlipidaemic rats. J. Nat. Med. 2009, 63, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, J. Swertiamarin decreases lipid accumulation dependent on 3-ketoacyl-coA thiolase. Biomed. Pharmacother. = Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Chen, G.; He, W.; Chi, H.; Abe, H.; Yamashita, K.; Yokoyama, M.; Kodama, H. Inhibitory effects of secoiridoids from the roots of Gentiana straminea on stimulus-induced superoxide generation, phosphorylation and translocation of cytosolic compounds to plasma membrane in human neutrophils. Phytother. Res.: PTR 2012, 26, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, M.E.; Tchernof, A.; Després, J.P. Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Li, D.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, S.; Liang, X.; Tang, Y.; Jin, S.; Ding, C. Swertiamarin supplementation prevents obesity-related chronic inflammation and insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Adipocyte 2021, 10, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, O.; Cai, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Jin, S.; Ding, C.; Xu, L. Swertiamarin ameliorates diet-induced obesity by promoting adipose tissue browning and oxidative metabolism in preexisting obese mice. Acta Biochim. Et Biophys. Sin. 2022, 55, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Pandikumar, P.; Prakash Babu, N.; Hairul Islam, V.I.; Thirugnanasambantham, K.; Gabriel Paulraj, M.; Balakrishna, K.; Ignacimuthu, S. In vivo and in vitro immunomodulatory potential of swertiamarin isolated from Enicostema axillare (Lam.) A. Raynal that acts as an anti-inflammatory agent. Inflammation 2014, 37, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Xu, H.; Wu, W.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Hou, Y.; Bai, G. A natural AKT inhibitor swertiamarin targets AKT-PH domain, inhibits downstream signaling, and alleviates inflammation. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 1816–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Zinzuvadia, A.; Prajapati, M.; Tyagi, R.K.; Dalai, S. Swertiamarin-mediated immune modulation/adaptation confers protection against Plasmodium berghei. Future Microbiol. 2022, 17, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitlani, D.; Choudhary, R.; Pandey, D.P.; Bodakhe, S.H. Ameliorative antimalarial effects of the combination of rutin and swertiamarin on malarial parasites. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2016, 6, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, L.; Han, Y.; Ma, X.; Hou, Y.; Bai, G. Mechanism Assay of Honeysuckle for Heat-Clearing Based on Metabolites and Metabolomics. Metabolites 2022, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaijanathappa, J.; Badami, S. Antiedematogenic and free radical scavenging activity of swertiamarin isolated from Enicostemma axillare. Planta Medica 2009, 75, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ke, Y.; Ren, Z.; Lei, X.; Xiao, S.; Bao, T.; Shi, Z.; Zou, R.; Wu, T.; Zhou, J.; Geng, C.A.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed genes in hepatocellular carcinoma cells exposed to Swertiamarin. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 6526–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tang, H.; Bai, Y.; Zou, R.; Ren, Z.; Wu, X.; Shi, Z.; Lan, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, T.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L. Swertiamarin suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via negative regulation of FRAT1. Eur. J. Histochem. : EJH 2020, 64, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, B.A.; Ramamoorthy, D.; Rather, M.A.; Arumugam, N.; Qazi, A.K.; Majeed, R.; Hamid, A.; Ganie, S.A.; Ganai, B.A.; Anand, R.; Gupta, A.P. Induction of apoptosis in human pancreatic MiaPaCa-2 cells through the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) by Gentiana kurroo root extract and LC-ESI-MS analysis of its principal constituents. Phytomedicine: Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2013, 20, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Lv, J.; Jiang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H. Iridoid compounds from the aerial parts of Swertia mussotii Franch with cytotoxic activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta Šobot, A.; Drakulić, D.; Todorović, A.; Janić, M.; Božović, A.; Todorović, L.; Filipović Tričković, J. Gentiopicroside and swertiamarin induce non-selective oxidative stress-mediated cytotoxic effects in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2024, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Kallubai, M.; Subramanyam, R. Comparative binding of Swertiamarin with human serum albumin and α-1 glycoprotein and its cytotoxicity against neuroblastoma cells. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38, 5266–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; Mcinnes, I.B. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Islam, V.I.; Thirugnanasambantham, K.; Pazhanivel, N.; Raghuraman, N.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ignacimuthu, S. Swertiamarin ameliorates inflammation and osteoclastogenesis intermediates in IL-1β induced rat fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Inflamm. Res.: Off. J. Eur. Histamine Res. Soc. 2014, 63, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, N.; Takayanagi, H. Mechanisms of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis - immune cell-fibroblast-bone interactions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairul-Islam, M.I.; Saravanan, S.; Thirugnanasambantham, K.; Chellappandian, M.; Simon Durai Raj, C.; Karikalan, K.; Gabriel Paulraj, M.; Ignacimuthu, S. Swertiamarin, a natural steroid, prevent bone erosion by modulating RANKL/RANK/OPG signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 53, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Islam, V.I.; Babu, N.P.; Pandikumar, P.; Thirugnanasambantham, K.; Chellappandian, M.; Raj, C.S.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ignacimuthu, S. Swertiamarin attenuates inflammation mediators via modulating NF-κB/I κB and JAK2/STAT3 transcription factors in adjuvant induced arthritis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.: Off. J. Eur. Fed. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 56, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, V.; Stöckle, M.; Junker, K.; Roggenbuck, D. Benign prostatic hyperplasia - A novel autoimmune disease with a potential therapy consequence? Autoimmun. Rev. 2024, 23, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gu, Y.; Li, L. The anti-hyperplasia, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of Qing Ye Dan and swertiamarin in testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 265, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Lei, Y.; Liu, M. The anti-inflammation, anti-oxidative and anti-fibrosis properties of swertiamarin in cigarette smoke exposure-induced prostate dysfunction in rats. Aging 2019, 11, 10409–10421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Liang, Y.; Tian, S.; Jin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, H. Radiation-Induced Intestinal Injury: Injury Mechanism and Potential Treatment Strategies. Toxics 2023, 11, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; He, D.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Gong, L.; Tang, C.; Peng, H.; Qiu, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, T.; Li, J. Swertiamarin relieves radiation-induced intestinal injury by limiting DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 2277–2290. [Google Scholar]

- Jaishree, V.; Badami, S.; Rupesh Kumar, M.; Tamizhmani, T. Antinociceptive activity of swertiamarin isolated from Enicostemma axillare. Phytomedicine: Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2009, 16, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabane, S.; Boudjelal, A.; Bouaziz-Terrachet, S.; Spinozzi, E.; Maggi, F.; Petrelli, R.; Tail, G. Analgesic effect of Centaurium erythraea and molecular docking investigation of the major component swertiamarin. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, Y.; Nahar, L.; Cox, P.J.; Jaspars, M.; Sarker, S.D. Bioactivity of secoiridoid glycosides from Centaurium erythraea. Phytomedicine: Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2003, 10, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siler, B.; Misić, D.; Nestorović, J.; Banjanac, T.; Glamoclija, J.; Soković, M.; Cirić, A. Antibacterial and antifungal screening of Centaurium pulchellum crude extracts and main secoiridoid compounds. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Perumal, S.; Gopal Samy, M.; Subramanian, D. In vitro and in silico screening of novel typhoid drugs from endangered herb (Enicostema axillare). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 2926–2936. [Google Scholar]

- Perumal, S.; Samy, M.G.; Subramanian, D. Effect of novel therapeutic medicine swertiamarin from Enicostema axillare in zebrafish infected with Salmonella typhi. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 100, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belani, M.A.; Shah, P.; Banker, M.; Gupta, S.S. Investigating the potential role of swertiamarin on insulin resistant and non-insulin resistant granulosa cells of poly cystic ovarian syndrome patients. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Sumiyoshi, M. Effects of Swertia japonica extract and its main compound swertiamarin on gastric emptying and gastrointestinal motility in mice. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Zou, S.; Xu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, D. Screening of Inhibitors against Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Few-shot Machine Learning and Molecule Docking based Drug Repurposing. Curr. Comput. -Aided Drug Des. 2024, 20, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Zou, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, D. Identification and validation of targets of swertiamarin on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through bioinformatics and molecular docking-based approach. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, S.; Ibrahim Ia, A.; Fan, L. Cardioprotective Role of Swertiamarin, a Plant Glycoside Against Experimentally Induced Myocardial Infarction via Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Functions. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 5394–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, V.A.; Kuberapandian, D. Evaluation of Anti-hypertrophic Potential of Enicostemma littorale Blume on Isoproterenol Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Indian J. Clin. Biochem.: IJCB 2021, 36, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Gopal Samy, M.V.; Subramanian, D. Developmental toxicity, antioxidant, and marker enzyme assessment of swertiamarin in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Niguram, P.; Jairaj, V.; Chauhan, N.; Jinagal, S.; Sagar, S.; Sindhu, R.K.; Chandra, A. Exploring the potential of semi-synthetic Swertiamarin analogues for GLUT facilitation and insulin secretion in NIT-1 cell lines: A molecular docking and in-vitro study. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Niguram, P.; Bhat, V.; Jinagal, S.; Jairaj, V.; Chauhan, N. Synthesis, molecular docking and ADMET prediction of novel swertiamarin analogues for the restoration of type-2 diabetes: An enzyme inhibition assay. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 2197–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, X.X.; Geng, C.A.; Huang, X.Y.; Ma, Y.B.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, R.P.; Chen, J.J. Five new secoiridoid glycosides and one unusual lactonic enol ketone with anti-HBV activity from Swertia cincta. Fitoterapia 2015, 102, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).