Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

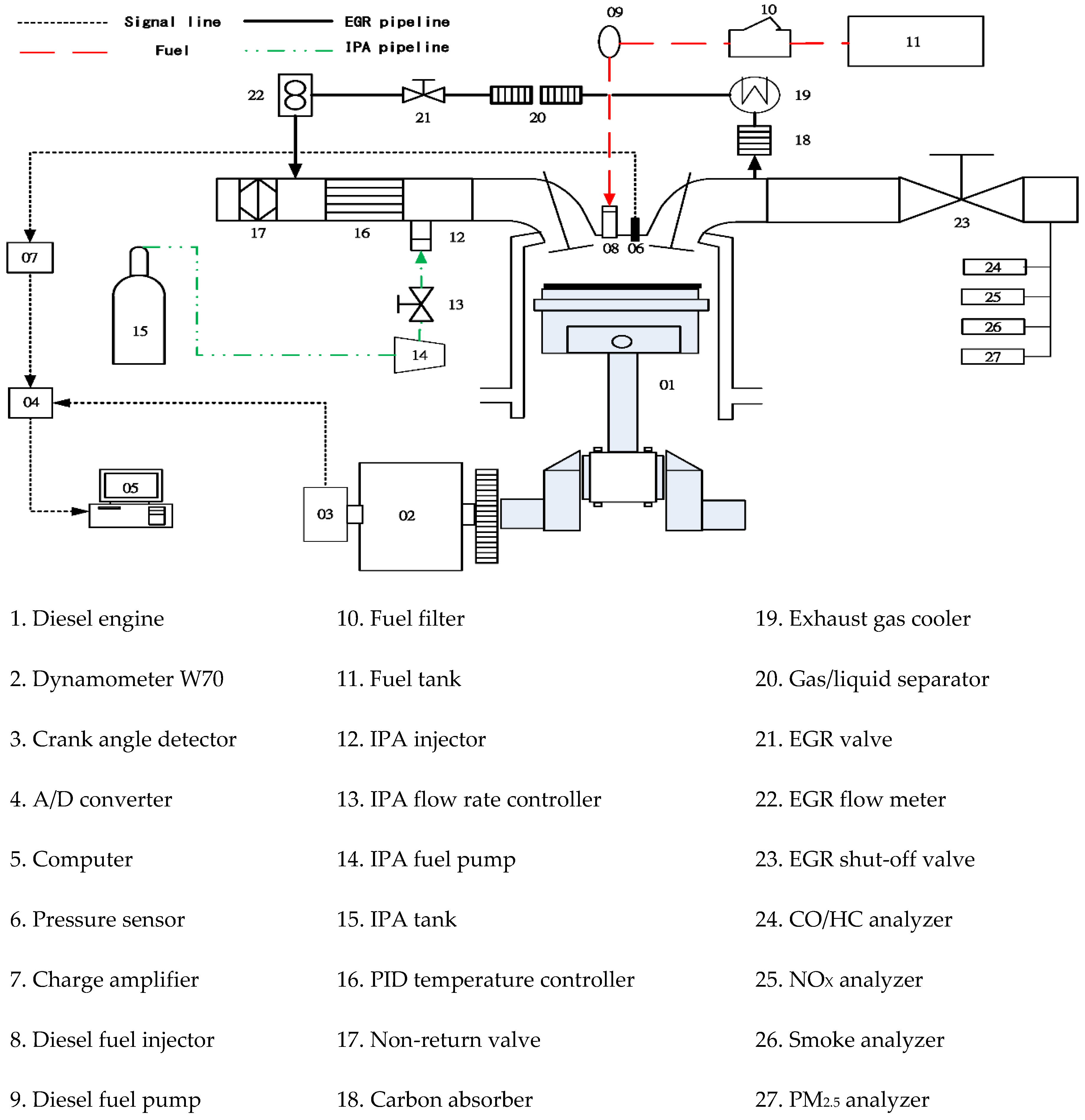

2. Experimental Arrangement

3. Methodology Descriptions

4. Results and Discussion

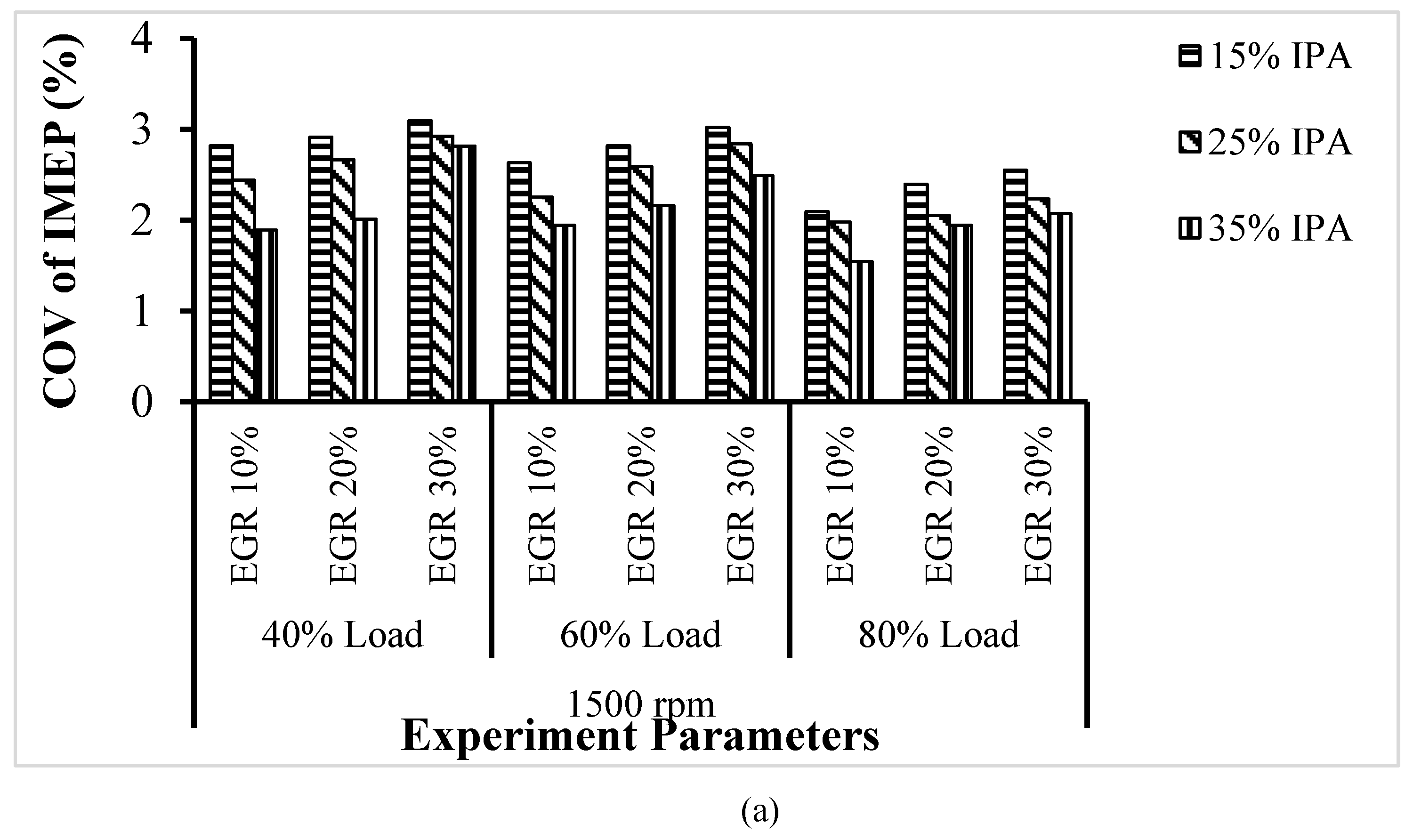

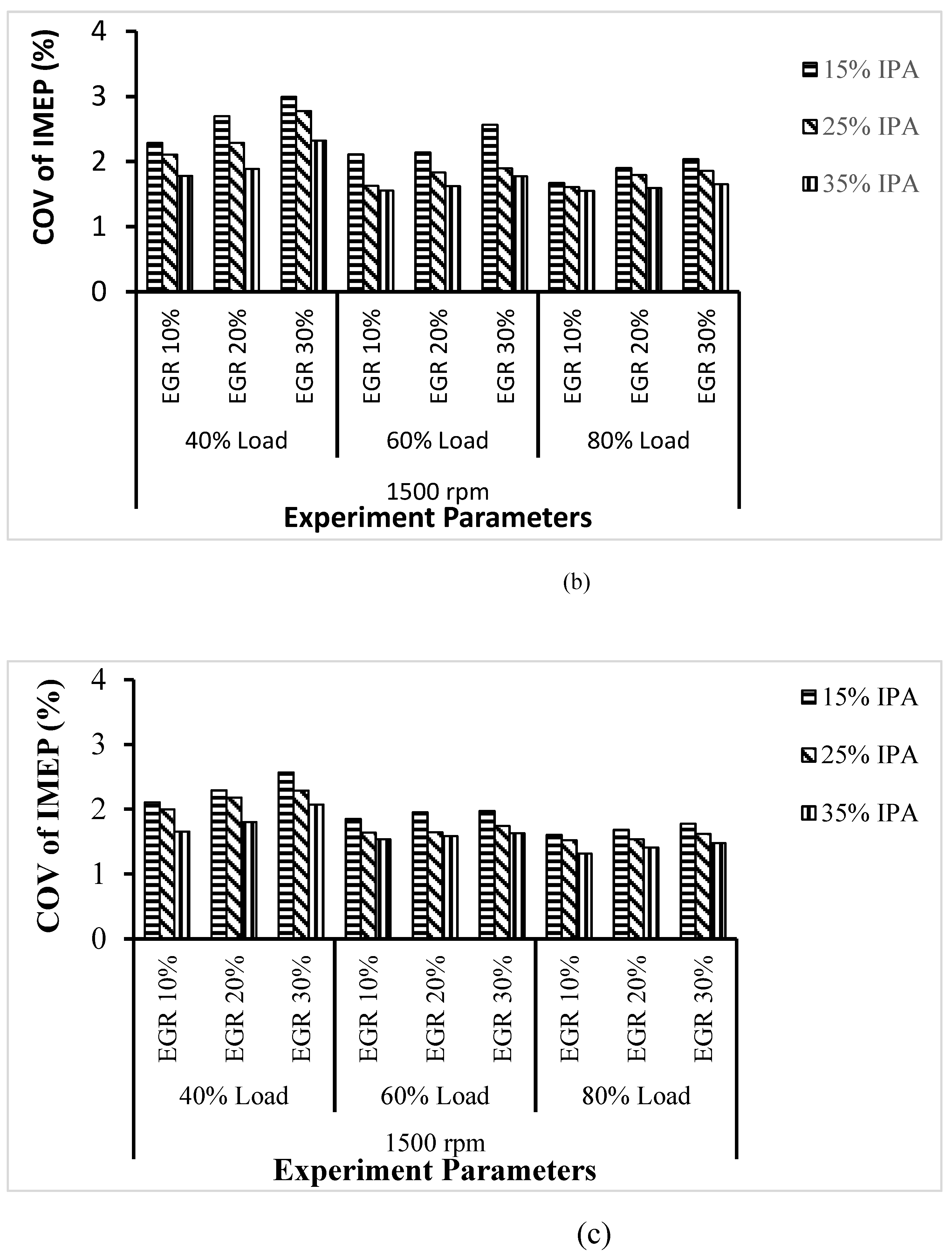

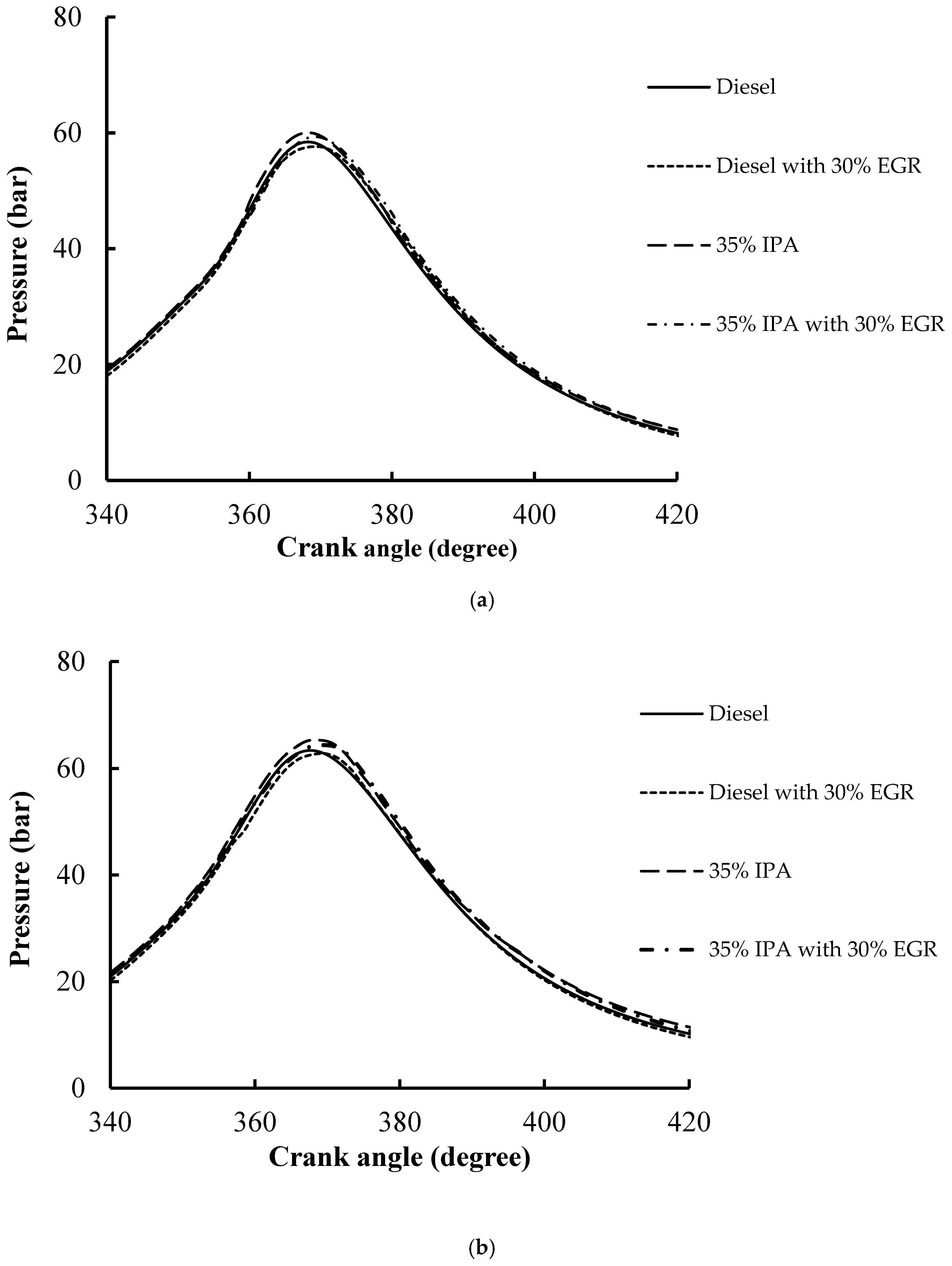

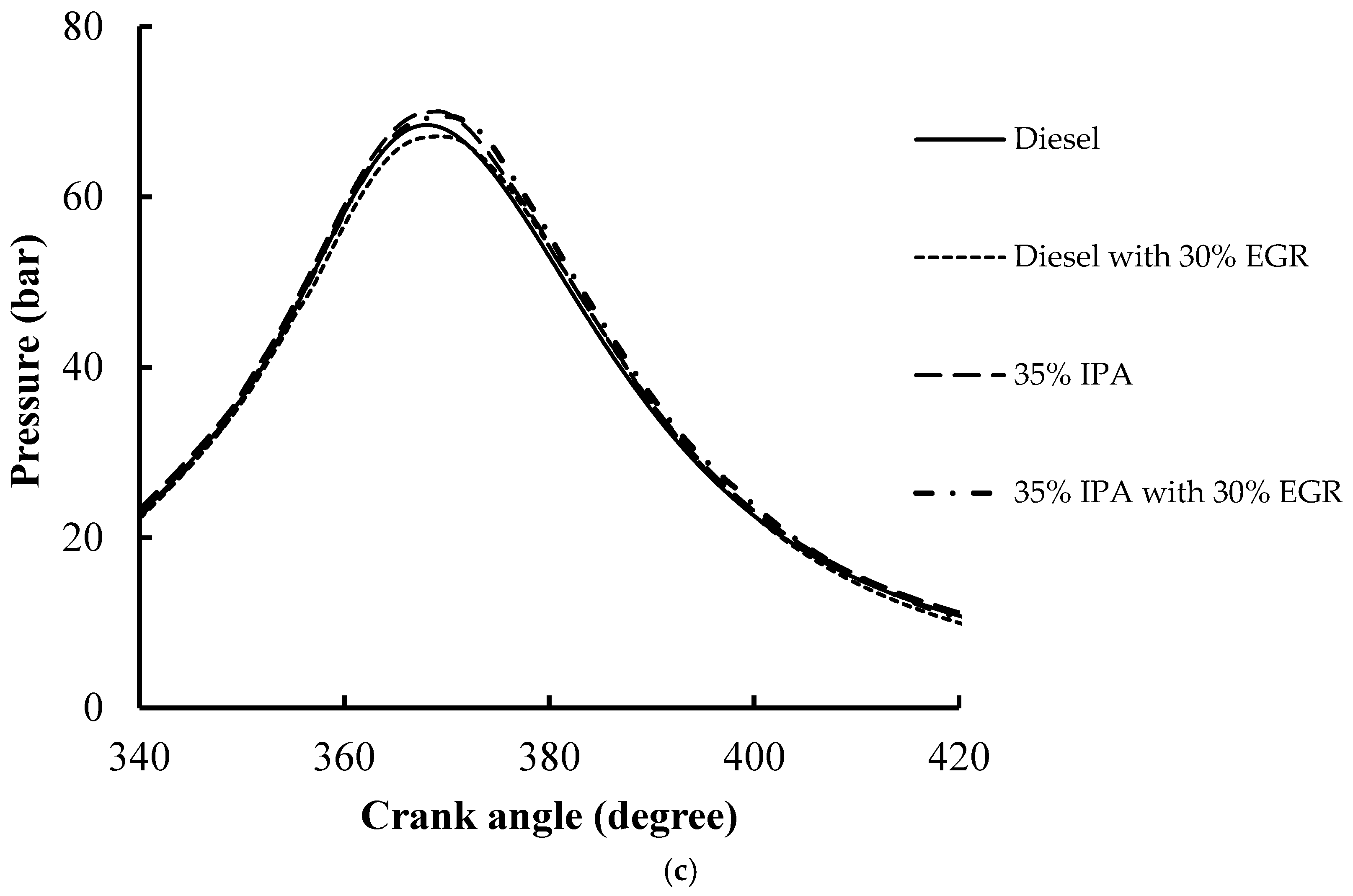

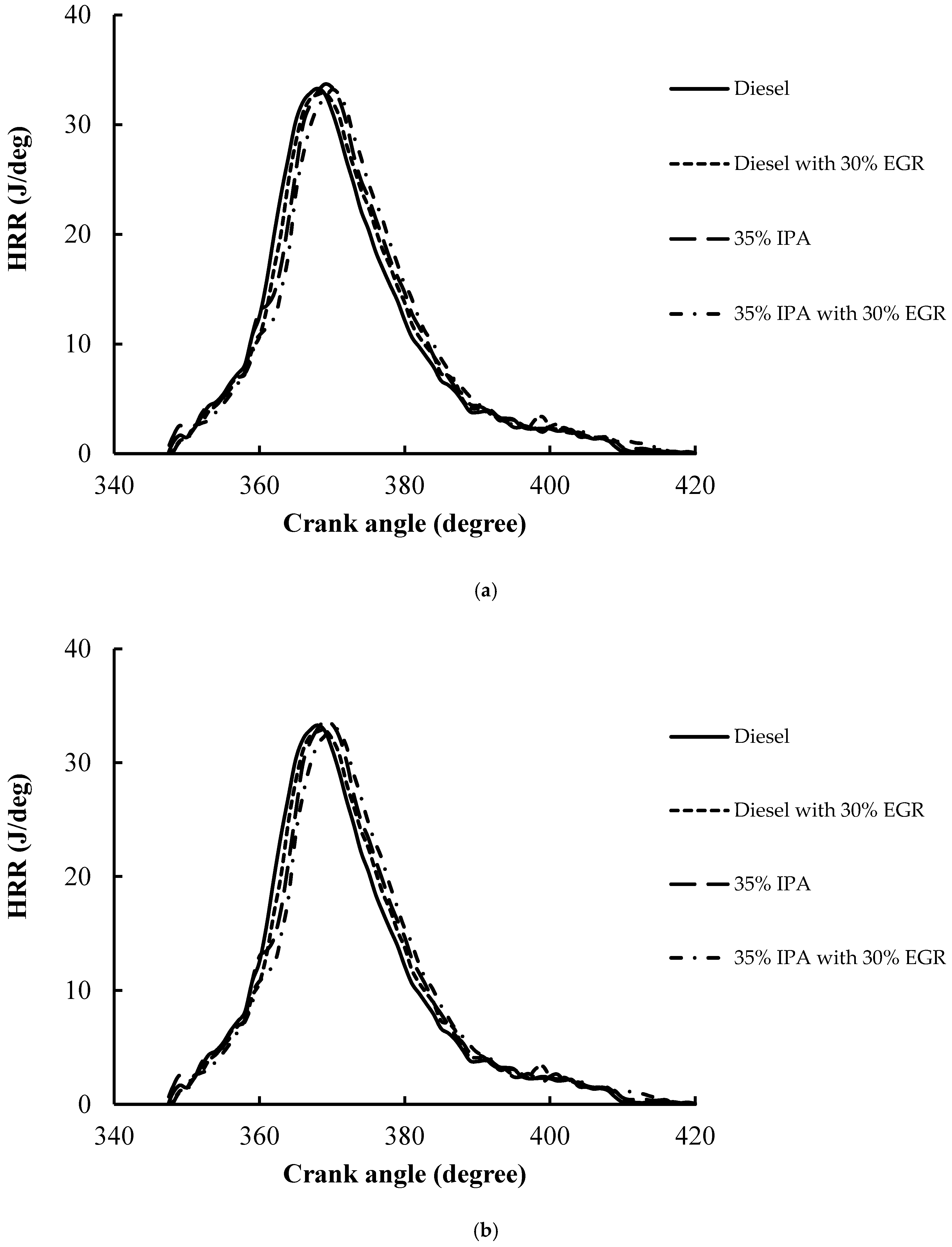

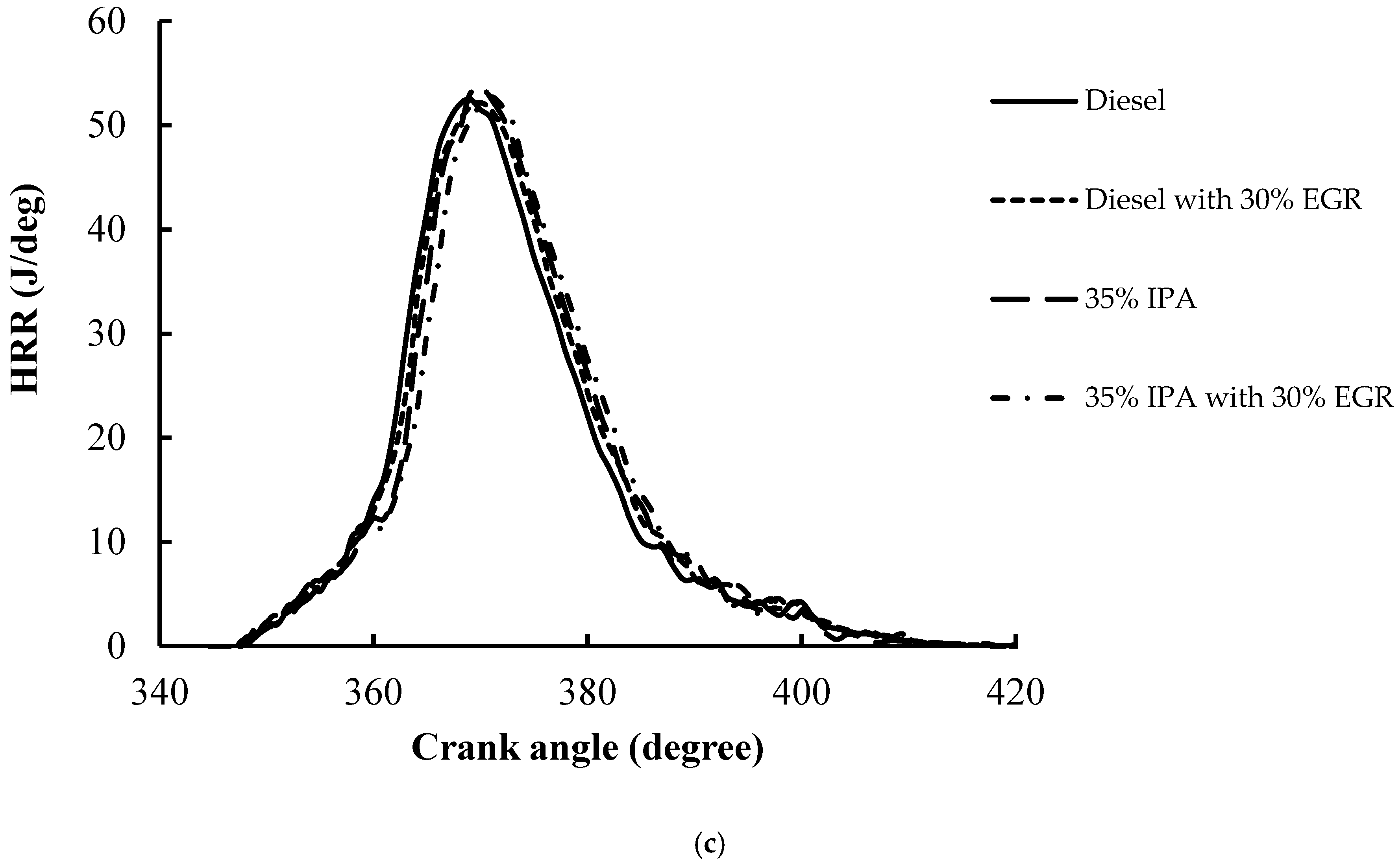

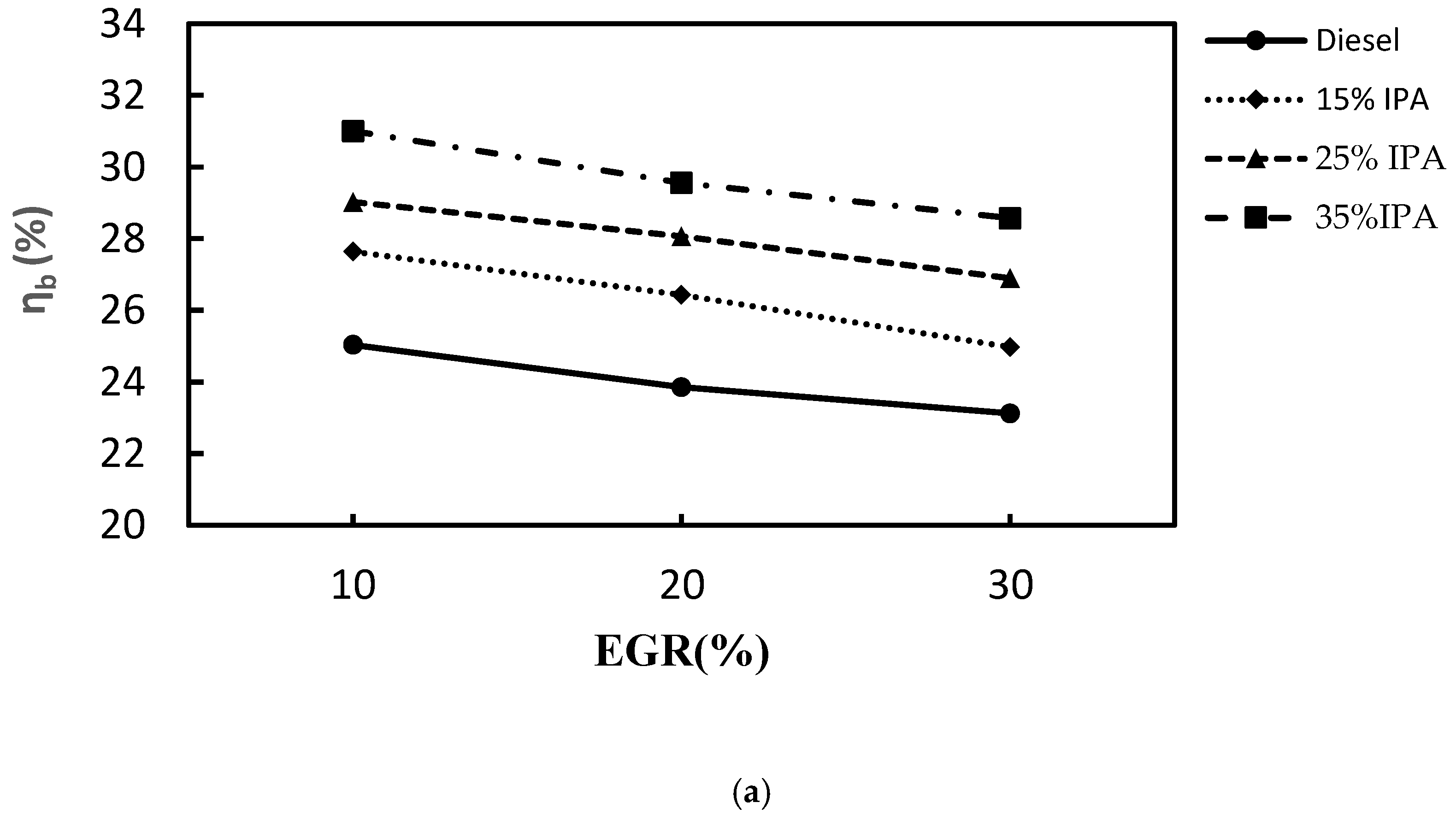

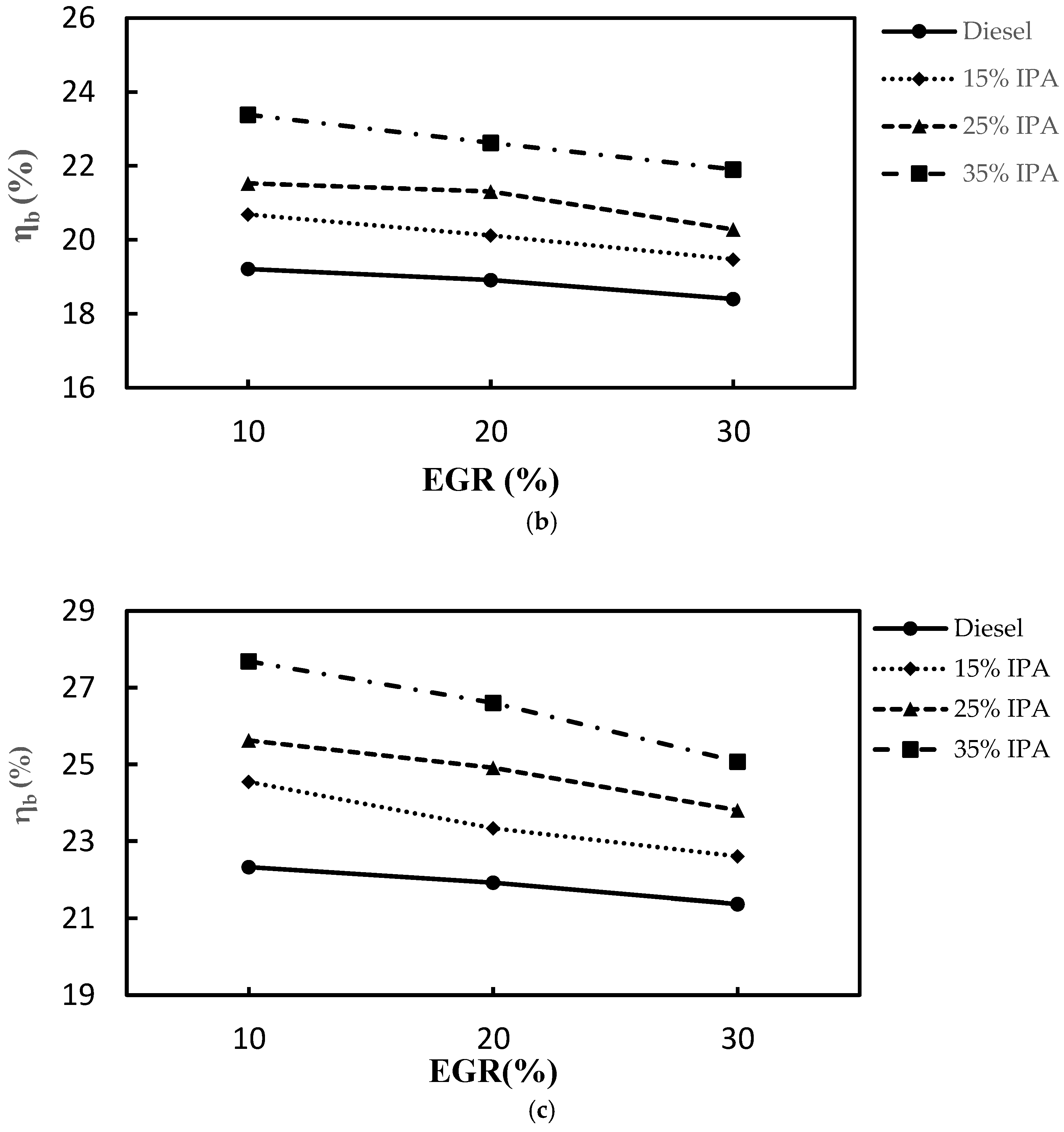

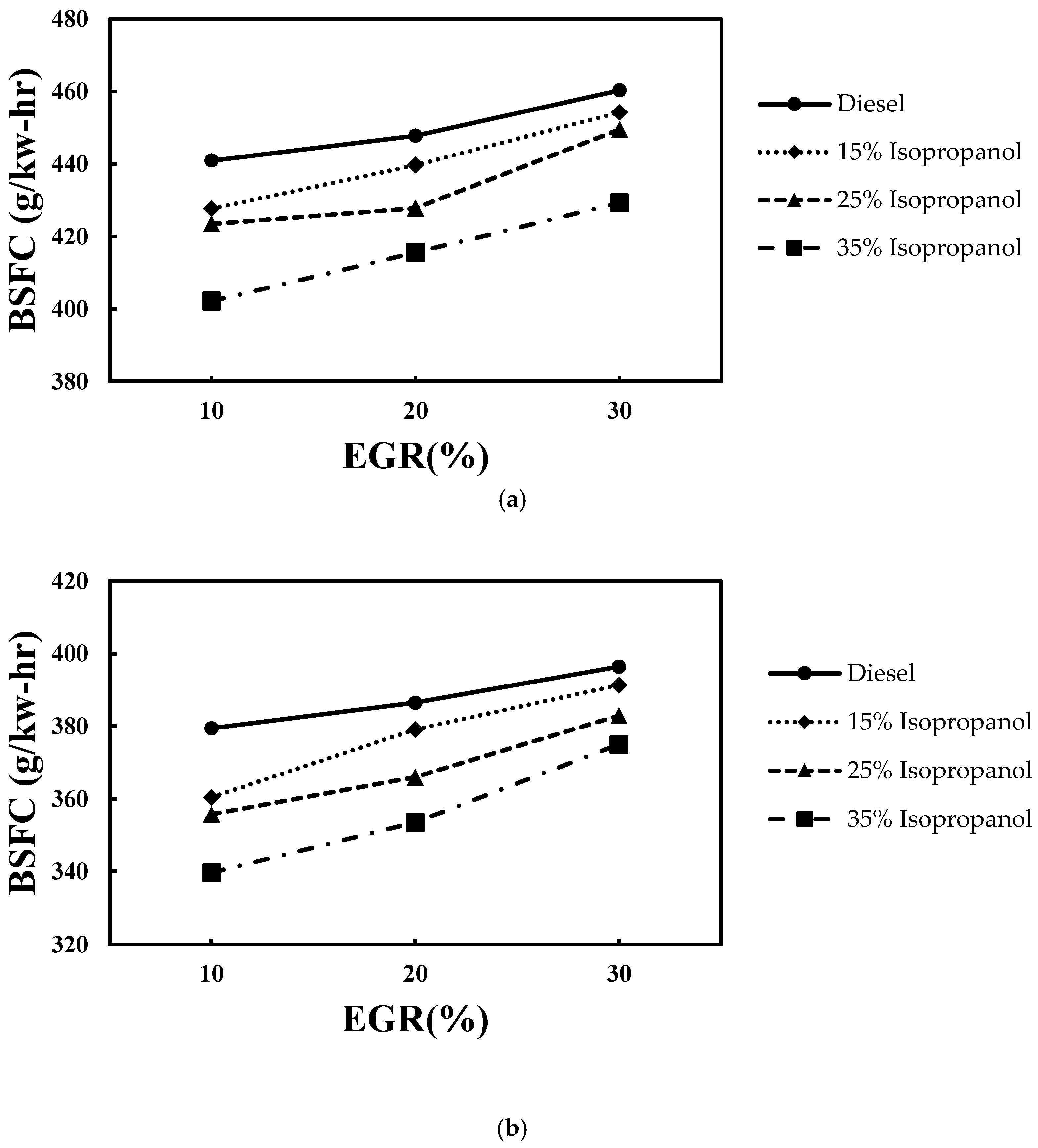

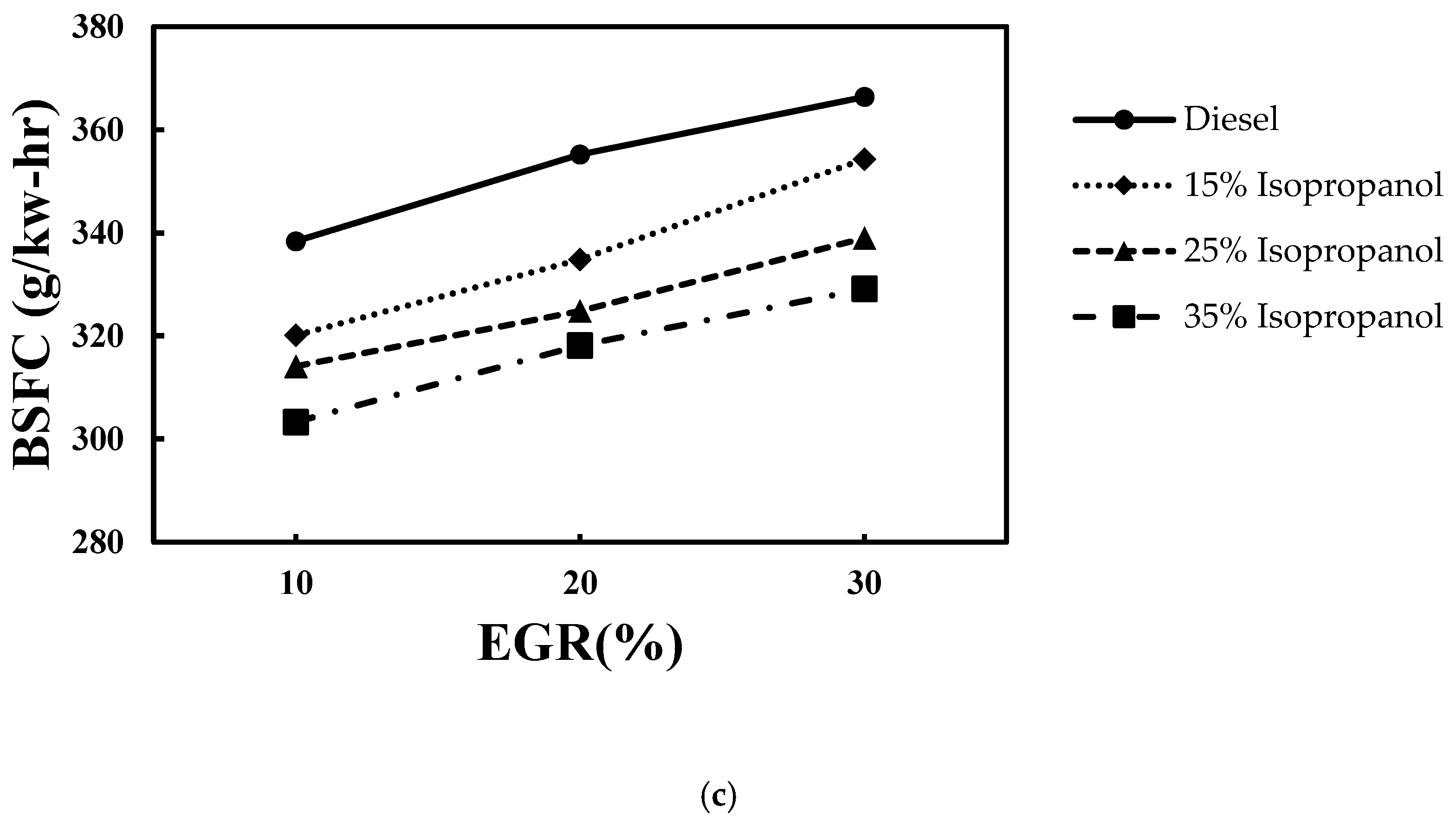

4.1. Combustion Performance

4.1.1. COV (IMEP), Within-Cylinder Pressure, and

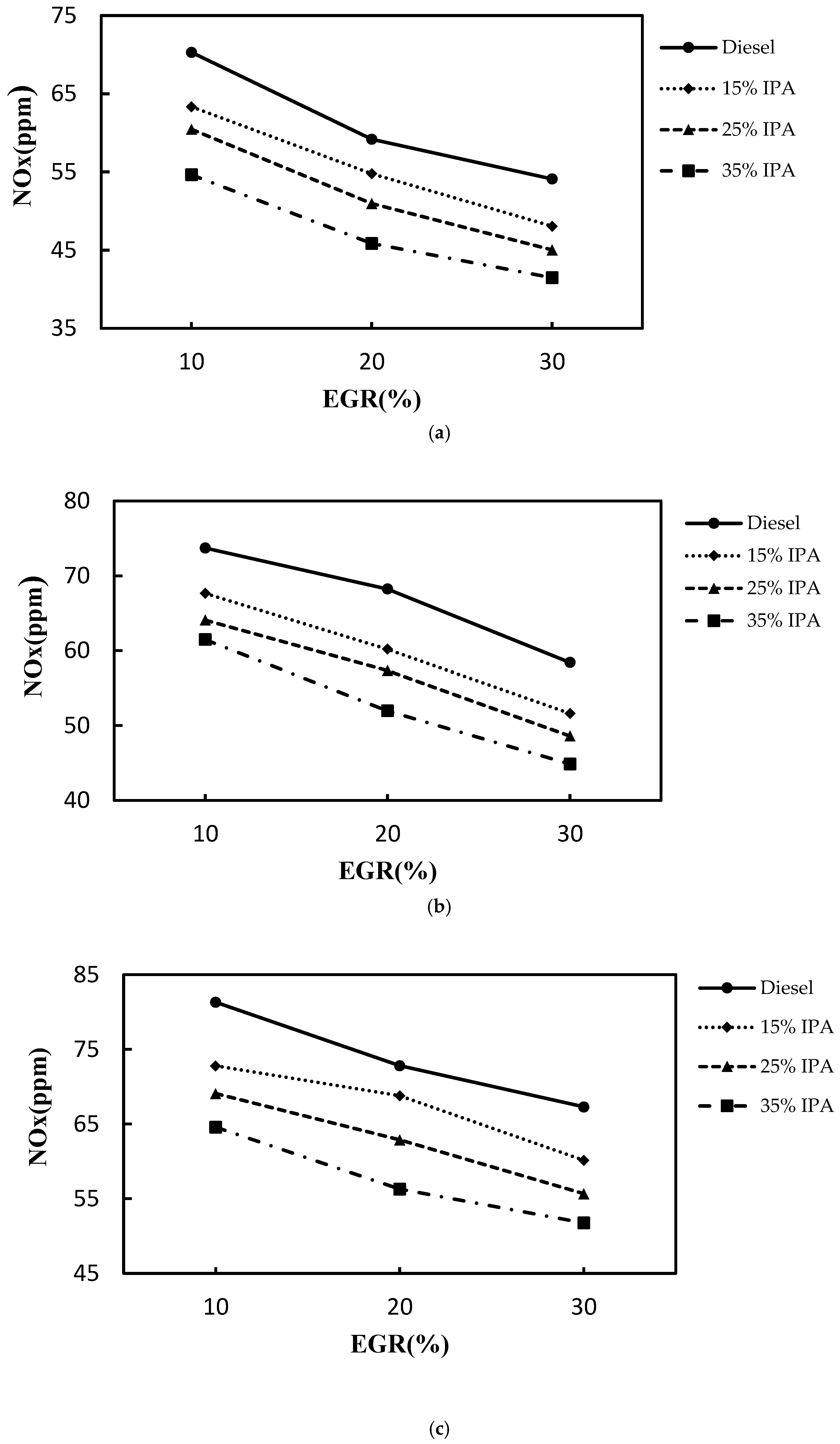

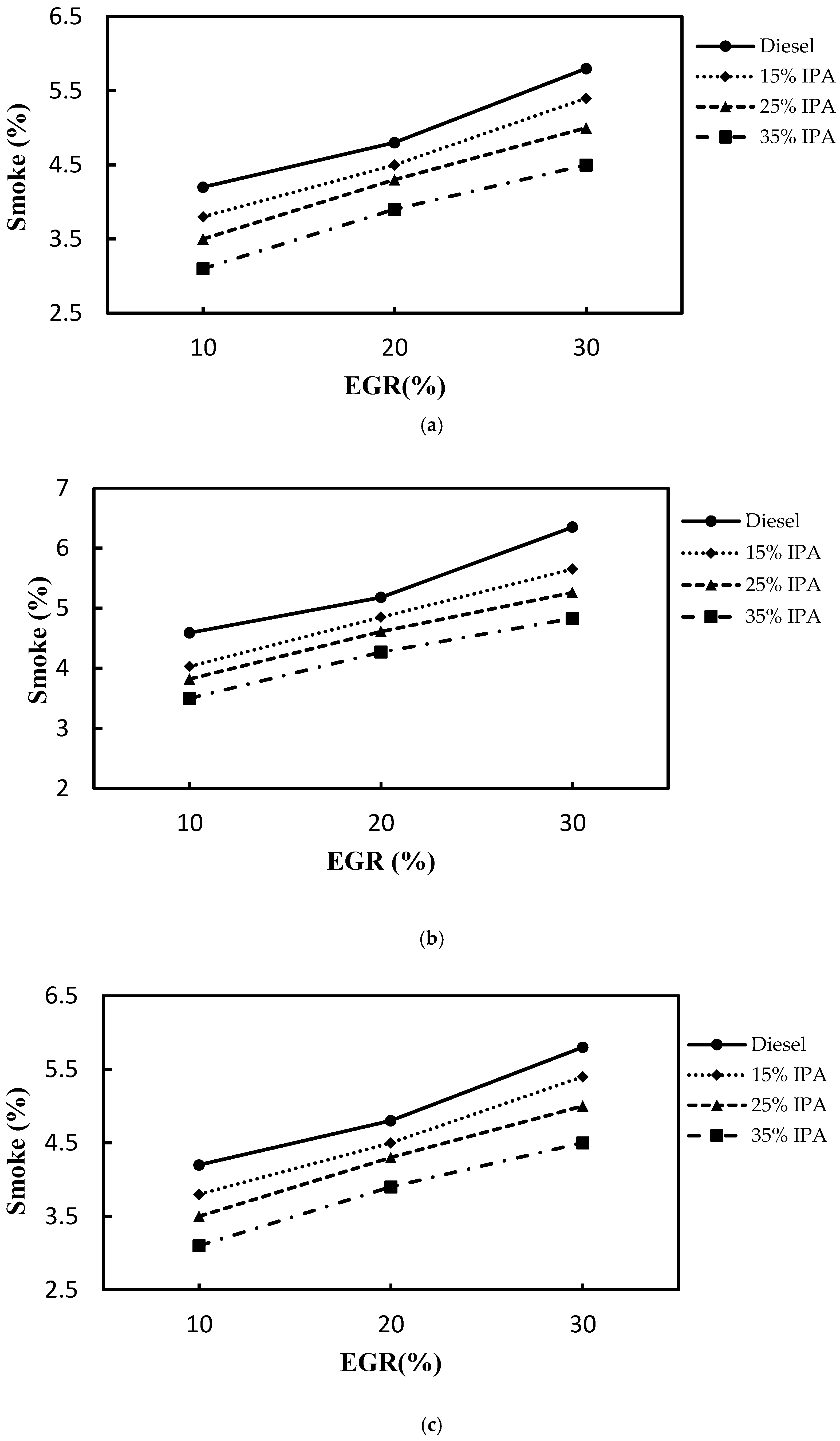

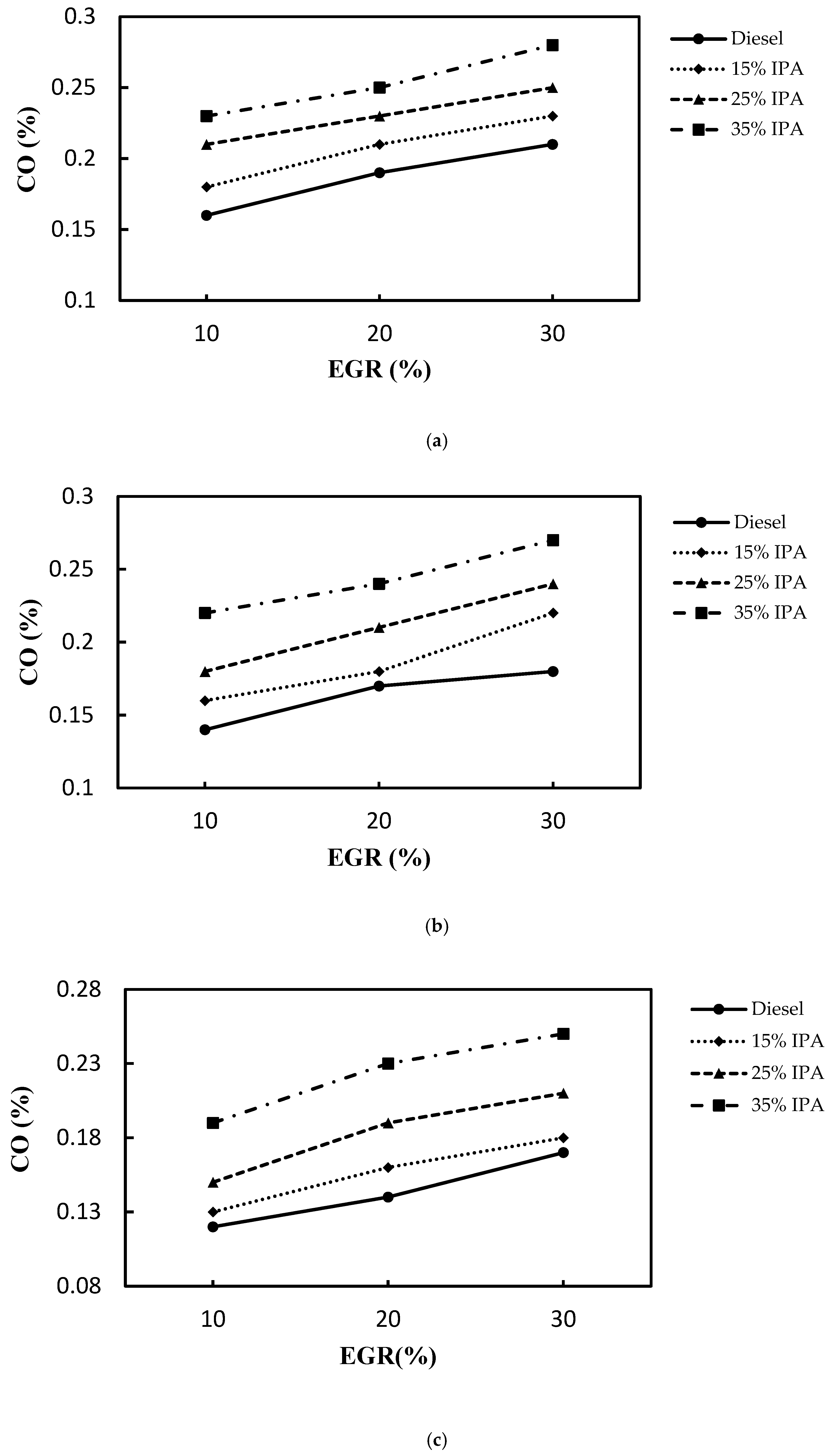

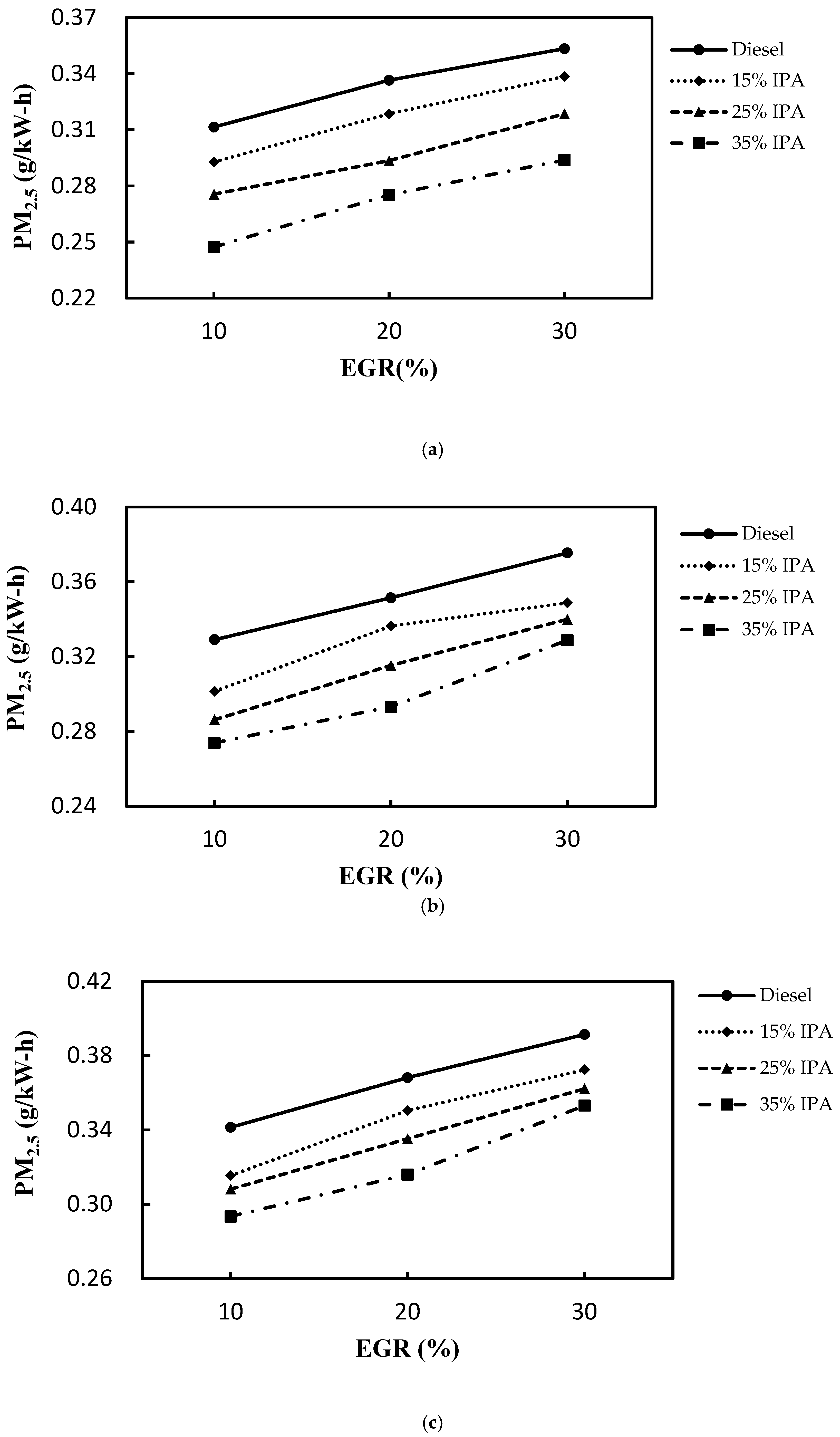

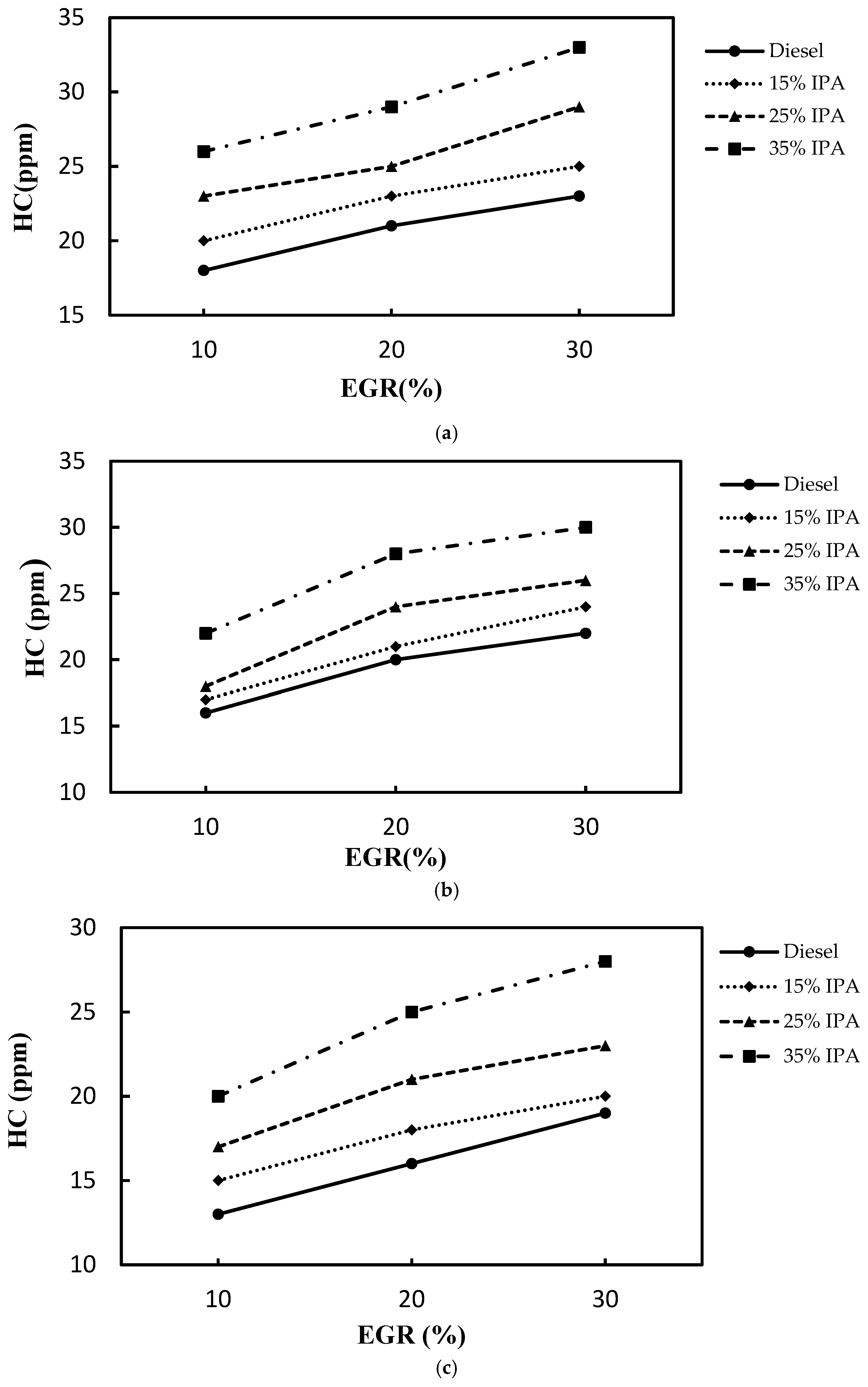

4.2. Effect on Emissions (NOX, Smoke, CO, PM2.5, and HC)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Brake power (kW) |

| BSFC | Brake specific fuel consumption (g/kW-h) |

| COV( IMEP) | Coefficient of variance for IMEP (%) |

| EGR ratio | Exhaust gas recirculation ratio (%) |

| IMEP | Indicated mean effective pressure (bar) |

| Averaged mean effective pressure (bar) | |

| LHV | Lower heating value (kJ/g) |

| Mass rate (g/h) | |

| N | Sampling cycles number |

| NOX | Nitric oxides concentrations (ppm) |

| p | In-cylinder pressure (bar) |

| ppm | Part per million |

| Q | Heat release (J) |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| T | Gas temperature (K) |

| V | Volume (m3) |

| Specific heat ratio | |

| Brake thermal efficiency (%) | |

| θ | Crank angle (degrees) |

| Standard deviation |

| a | Actual |

| air | Air |

| D | Diesel oil |

| i | The ith cycle |

| IPA | Isopropanol |

| s | Stoichiometric |

References

- A.T. Kirkpatrick. Internal combustion engines: applied thermosciences, 4th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Y.F. Xing; Y.H. Xu; M.H. Shi; Y.X. Lian. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J Thorac Dis. 2016; 8, 69–74.

- R.K. Singh; A. Sarkar, J.P. Chakraborty. Influence of alternate fuels on the performance and emission from internal combustion engines and soot particle collection using thermophoretic sampler: a comprehensive review. Waste Biomass Valori. 2019; 10: 2801-2823. [CrossRef]

- B.R. Kumara, S. Saravananb. Use of higher alcohol biofuels in diesel engines: A review. Ren. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016; 60: 84–115.

- C.F. Mao; J.W. Wei; X. Wu; A. Ukaew. Performance and exhaust emissions from diesel engines with different blending ratios of biofuels. Processes 2024; 12I, Article: 501. [CrossRef]

- H.W. Wu; R.H. Wang; Y.C. Chen; D.J. Ou.; T.Y. Chen. Influence of port-inducted ethanol or gasoline on combustion and emission of a closed cycle diesel engine. Energy 2014; 64: 259–267. [CrossRef]

- Redel-Macías; S. Pinzi; M. Babaie; A. Zare; A. Cubero-Atienza; M.P. Dorado. Bibliometric Studies on emissions from diesel engines running on alcohol/diesel fuel blends. a case study about noise emissions. Processes 2021; 9, Article: 623. [CrossRef]

- Z.Y. Wu; H.W. Wu; H.H. Hung. Applying Taguchi method to combustion characteristics and optimal factors determination in diesel/biodiesel engines with port-injecting LPG. Fuel 2014; 117, Part A, 30. 8–14. [CrossRef]

- T.T. Yang; D.D. Chen; L. Liu; L.Y. Zhang; T. Wang; G.X. Li ; H.W. Chen; Y. Chen. Effect of pilot injection strategy on performance of diesel engine under ethanol/F-T diesel dual-fuel combustion mode. Processes 2023;11, Article:1919. [CrossRef]

- H.W. Wu; C.M. Fan; J.Y. He; T.T. Hsu. Optimal factors estimation for diesel/methanol engines changing methanol injection timing and inlet air temperature, Energy 2017; 141:1819-1828. [CrossRef]

- S. Caprioli; A. Volza; F. Scrignoli; T. Savioli; E. Mattarelli; C.A. Rinaldini. Combustion chamber optimization for dual-fuel biogas-diesel co-combustion in compression jgnition engines. Processes 2023; Article: 1113. [CrossRef]

- Erdiwansyah; R. Mamat; M.S.M.Sani,; K. Sudhakar; A. Kadarohman; R.E. Sardjono. An over view of Higher alcohol and biodiesel as alternative fuels in engines. Energy Reports 2019; 5: 467-479. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang; X. Su; H. Chen; L.M Geng; X. Zhao. Experimental investigation on NOx and PM pollutions of a common-rail diesel engine fueled with diesel/gasoline/isopropanol blends. Sustain. Energy & Fuels 2019; 3:2260-2274. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Rayapureddy; J. Matijosius; A. Rimkus. Comparison of research data of diesel-biodiesel-isopropanol and diesel-rapeseed oil-isopropanol fuel blends mixed at different proportions on a CI Engine. Sustainability 2021; 13, Article: 10059. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen; Z.G. Zhou; J.J. He; P. Zhang; X. Zhao. Effect of isopropanol and n-pentanol addition in diesel on the combustion and emission of a common rail diesel engine under pilot plus main injection strategy. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 1734-1747. [CrossRef]

- Y.B. Liu; B. Xu; J.H. Jia; J.A. Wu; W.W. Shang; Z.H. Ma. Effect of injection timing on performance and emissions of DI-diesel engine fueled with isopropanol, International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Mechatronics, ICEEM, 2015.

- V. Talamala; P.R. Kancherla; V.A.R. Basava.; A. Kolakoti. Experimental investigation on combustion, emissions, performance and cylinder vibration analysis of an IDI engine with RBME along with isopropanol as an additive. Biofuels-UK 2017; 8: 307-321. [CrossRef]

- T.V. Babu; B.V. AppaRao; A. Kolakoti Engine combustion analysis of an IDI-diesel engine with Rice Bran Methyl Ester and Isopropanol Injection at suction end, J. Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology. 2014; 1: 254-261.

- H. Chen; Z.G. Zhou; J.J. He; P. Zhang; X. Zhao. Effect of isopropanol and n-pentanol addition in diesel on the combustion and emission of a common rail diesel engine under pilot plus main injection strategy. Energy Reports: 2020; 6: 1734-1747. [CrossRef]

- J. Gong; Y.J. Zhang; C.L. Tang; Z.H. Huang. Emission characteristics of isopropanol/gasoline blends in a spark-ignition engine combined with exhaust gas re-circulation. Thermal Science 2014; 18:269-277. [CrossRef]

- G. Li; J.Y. Dai; Y.Y. Li; T.H. Lee. Optical investigation on combustion and soot formation characteristics of isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE)/diesel blends Energy Sci. & Eng. 2021; 9: 2311-2320.

- Uyumaz. An experimental investigation into combustion and performance characteristics of an HCCI gasoline engine fueled with n-heptane, isopropanol and n-butanol fuel blends at different inlet air temperatures, Energy Conver. Manag. 2015; 98: 199-207. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Kim; S. Jo; J.T. Lee; S. Park. Biodiesel fueled combustion performance and emission characteristics under various intake air temperature and injection timing conditions. Energy 2020; 206, Article: 118154. [CrossRef]

- R.G. Papagiannakis. Study of air inlet preheating and EGR impacts for improving the operation of compression ignition engine running under dual fuel mode. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013; 68: 40-53. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar; U.K. Saha. Experimental probe into a biogas run dual fuel diesel engine using oxygenated ternary blends at optimum Equivalence Ratio and under the effect of intake charge preheating. J Eng. for Gas Turbine Power-Trans. ASME 2022; 144 Article: 061010. [CrossRef]

- D.S. Kim; M.Y. Kim; C.S. Lee. Reduction of nitric oxides and soot by premixed fuel in partial HCCI engine. the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Gas Turbines Power 2005; 128: 497-505. [CrossRef]

- M. Feroskhan; S. Ismail; M.G. Reddy; A.S. Teja. Effects of charge preheating on the performance of a biogas-diesel dual fuel CI engine Eng. Scie. Techno.-An Inter. J-Jestech 2018; 21: 330-337. [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. EPA, http://www.epa.gov/pm/.

- H.W. Wu; T.T. Hsu; C.M. Fan; P.H. He. Reduction of smoke, PM2.5, and NOx of a diesel engine integrated with methanol steam reformer recovering waste heat and cooled EGR. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018; 172: 567-578. [CrossRef]

- J.B. Holman. Experimental methods for engineers, McGraw Hill Publications, New York, 2003.

- F.E. Obert, Internal combustion engines and air pollution, Index Education Publishers, New York, Chap 2, 1973.

- F. Cruz-Peragón, F.J. Jiménez-Espadafor, J.A. Palomar, M.P. Dorado, Influence of a combustion parametric model on the cyclic angular speed of internal combustion engines. Part I: setup for sensitivity analysis. Energy & Fuels 2009: 23: 2921-2929. [CrossRef]

- J.B. Heywood. Internal combustion engine fundamentals, 2nd ed., New York, U.S.A: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 2018.

|

| Measuring instruments | Measurement range | Accuracy |

| CO/HC/CO2 Gas detector |

CO: 0-10% (Vol.) | ± 0.01% |

| HC: 0-15000 (ppm) | ± 0.022% | |

| CO2: 0-20% (Vol.) | ± 0.17% | |

| NOX analyzer | 0-5000(ppm) | ± 0.02% |

| Smoke analyzer | 0%-100% | ± 0.1% |

| Item | Uncertainty |

| Pressure | ± 1.3% |

| Smoke | ± 2.7% |

| NOX | ± 1.4% |

| HC | ± 1.3% |

| PM2.5 | ± 1.8% |

| CO | ± 1.1% |

| Brake power | ± 2.5% |

| ± 3.1% | |

| Heat release rate | ± 3.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).