1. Introduction

As concerns about fossil fuel depletion and climate change grow, the need for an energy transition has emerged as a global issue. With industrialization and economic growth, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased, worsening the negative environmental impact, and the need for sustainable energy sources has become more pronounced. In response, many countries are actively participating in international agreements, including the Paris Agreement [

1], to reduce GHG emissions and address climate change. Such international efforts have promoted the development of new and renewable energy sources and eco-friendly alternatives to traditional fossil fuels.

Diesel engines are essential for transportation, heavy equipment, power generation, and agriculture due to their high thermal efficiency, powerful output, high torque at low speeds, and excellent durability. Additionally, diesel fuel produces lower emissions of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC), and carbon dioxide (CO₂) than gasoline, providing an advantage in fuel efficiency. However, nitrogen oxides (NO

x) and particulate matter (PM) emissions from diesel engines have adverse effects on the environment and public health [

2], posing a significant limitation in terms of sustainability. To mitigate these issues, advanced fuels such as low-sulfur options have been introduced [

3], along with exhaust gas after-treatment technologies. For instance, diesel oxidation catalysts (DOCs) convert CO into CO₂ and water, while devices combining DOCs and diesel particulate filters (DPFs) effectively reduce fine and nanoparticle emissions when biodiesel-blended fuel is used. Moreover, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) technology has been introduced to reduce NO

x emissions [

4,

5].

Various biofuels, including biodiesel and bioethanol, have been actively studied to reduce pollutant emissions from diesel engines. Alcohol-based fuels are particularly effective in reducing harmful emissions such as smoke. Moreover, alcohol-based fuels are advantaged by their high availability due to their well-established industrial base. Produced from renewable resources such as biomass, alcohol fuels exhibit physicochemical properties that vary with the number of carbon atoms and the bonding structure of the alcohol molecule, influencing combustion performance and emissions. Consequently, they show distinct differences in miscibility, ignition timing, and emission characteristics when blended with diesel or gasoline fuels [

6,

7].

Among alcohols, lower alcohols such as methanol and ethanol are the most extensively studied fuels. These alcohols effectively improve diesel engine fuel efficiency when blended in small quantities [

8,

9], but high-concentration blends encounter limitations due to phase separation [

10]. To address this, surfactants can be added, or dual fuel injection methods may be employed, such as injecting alcohol into the intake port while directly injecting diesel into the combustion chamber [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Lower alcohols are effective in reducing smoke due to their high oxygen content. Still, their low heating value (LHV) and cetane number (CN) limit their ignition performance in compression ignition engines [

15].

To overcome the limitations of lower alcohols, higher alcohols such as butanol and octanol have recently gained attention as alternative fuels for diesel engines. Higher alcohols offer higher energy content and CN, which enhance compatibility with diesel engines and improve performance. Their greater molecular weight and low volatility also help resolve phase separation and volatility issues [

16,

17,

18]. Technologies have also been developed to convert syngas from biomass gasification into higher alcohols through catalytic reactions and microbial genetic engineering [

19,

20]. Synthesizing higher alcohols from CO

2 contributes to GHG reduction, presenting them as a promising eco-friendly fuel source for internal combustion engines [

21].

Butanol, a higher alcohol, can help reduce NO

x emissions by lowering the combustion temperature due to its high latent heat of vaporization when blended with diesel [

22]. However, studies have reported that while increasing the butanol ratio raises the maximum cylinder pressure and brake thermal efficiency (BTE), performance declines when the butanol ratio exceeds 50% due to the cooling effect on the combustion chamber [

23]. In contrast, blending octanol with diesel can reduce PM and NO

x emissions, though BTE varies with operating conditions [

24,

25]. The oxygen content in higher alcohols is crucial for enhancing combustion, reducing smoke and PM emissions, and effortlessly blending with diesel. This compatibility allows for use with minimal modifications to existing infrastructure, offering significant economic advantages [

26].

Current research on butanol and octanol indicates a positive impact on reducing harmful emissions and improving the combustion efficiency of diesel engines; however, further studies are needed to ensure performance consistency. In this context, decanol, a higher alcohol, has gained attention for its diesel-like calorific value and high CN [

27]. Decanol exhibits excellent compatibility with diesel engines, and its high LHV helps maintain stable combustion temperatures, promoting efficient combustion. Additionally, its high oxygen content aids in reducing incomplete combustion and suppressing PM emissions, enhancing the environmental friendliness of conventional diesel engines [

28]. However, decanol’s high viscosity may adversely affect fuel atomization and hinder air mixing, potentially impacting emission characteristics under different operating conditions. In this study, we comprehensively analyzed the performance and emission characteristics of diesel engines with various decanol-diesel blending ratios, identifying decanol’s advantages and potential limitations. Our goal is to evaluate the potential of decanol-blended fuels and provide foundational data for eco-friendly energy conversion.

3. Results and Discussion

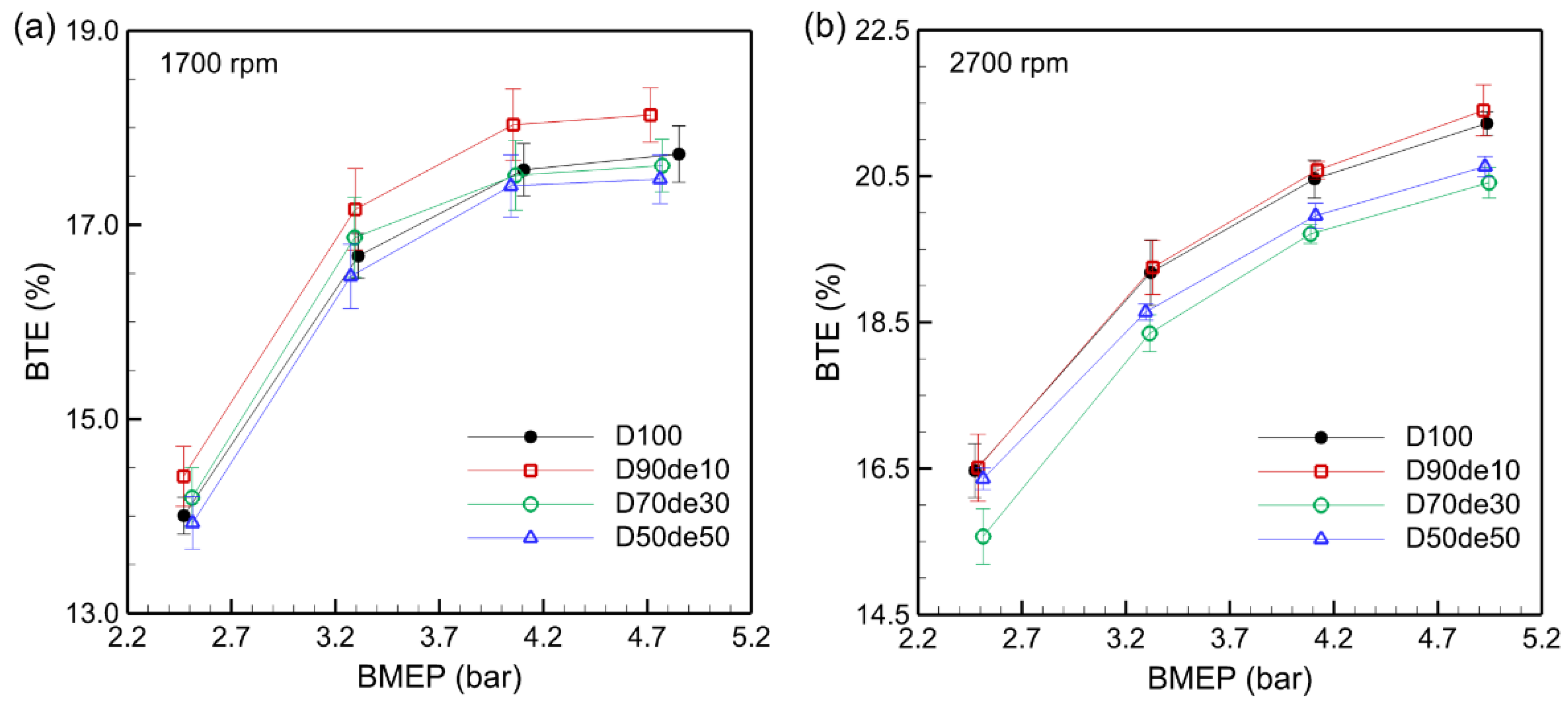

3.1. Brake Thermal Efficiency

Figure 2 shows that BTE tends to increase as brake mean effective pressure (BMEP) increases for all fuels, including pure diesel. At 2700 rpm, BTE was overall higher than at 1700 rpm. This is because the temperature inside the combustion chamber increases, as shown in

Table 4, and heat loss through the cylinder wall decreases as the fuel injection amount increases during high-speed operation. In addition, as shown in

Table 5, the air-fuel ratio is relatively close to the theoretical value, so heat loss to excess air also decreases. At 1700 rpm, BTE tends to decrease as the decanol blending ratio increases. Overall, D90de10 showed the highest BTE, and D50d50 showed the lowest BTE. However, D70de30 showed the lowest BTE at 2700 rpm.

Since these outcomes arise from various factors, several aspects should be considered to understand the correlation between the decanol blending ratio and BTE. First, decanol is an oxygenated fuel, and because 10.1 wt.% of oxygen is additionally generated during the fuel decomposition process, it reduces local incomplete combustion, increasing combustion efficiency and BTE. However, due to the higher kinematic viscosity of decanol (6.5 mm²/s), it is difficult to atomize the fuel, which hinders the uniform mixing of air and fuel at high speeds and leads to incomplete combustion, which may decrease BTE. Moreover, the higher heat of vaporization than diesel can lower the temperature inside the combustion chamber, thereby suppressing the initial combustion reaction upon ignition and slightly reducing BTE.

As shown in

Table 5, especially at 2700 rpm, the AFR of D70de30 is lower than that of D50de50, which relatively increases the oxygen-deficient area and enhances the cooling effect during the fuel evaporation process, tending to decrease combustion efficiency. Previous studies have also reported that oxygenated fuels such as decanol positively affect combustion efficiency, but atomization may become difficult due to increased viscosity [

31]. Based on these results, applying a high-pressure injection technique to enhance fuel atomization and a fuel preheating device to improve viscosity and increase the decanol blending ratio at high speeds seems necessary. Furthermore, optimizing the initial combustion reaction by controlling injection timing could also be effective.

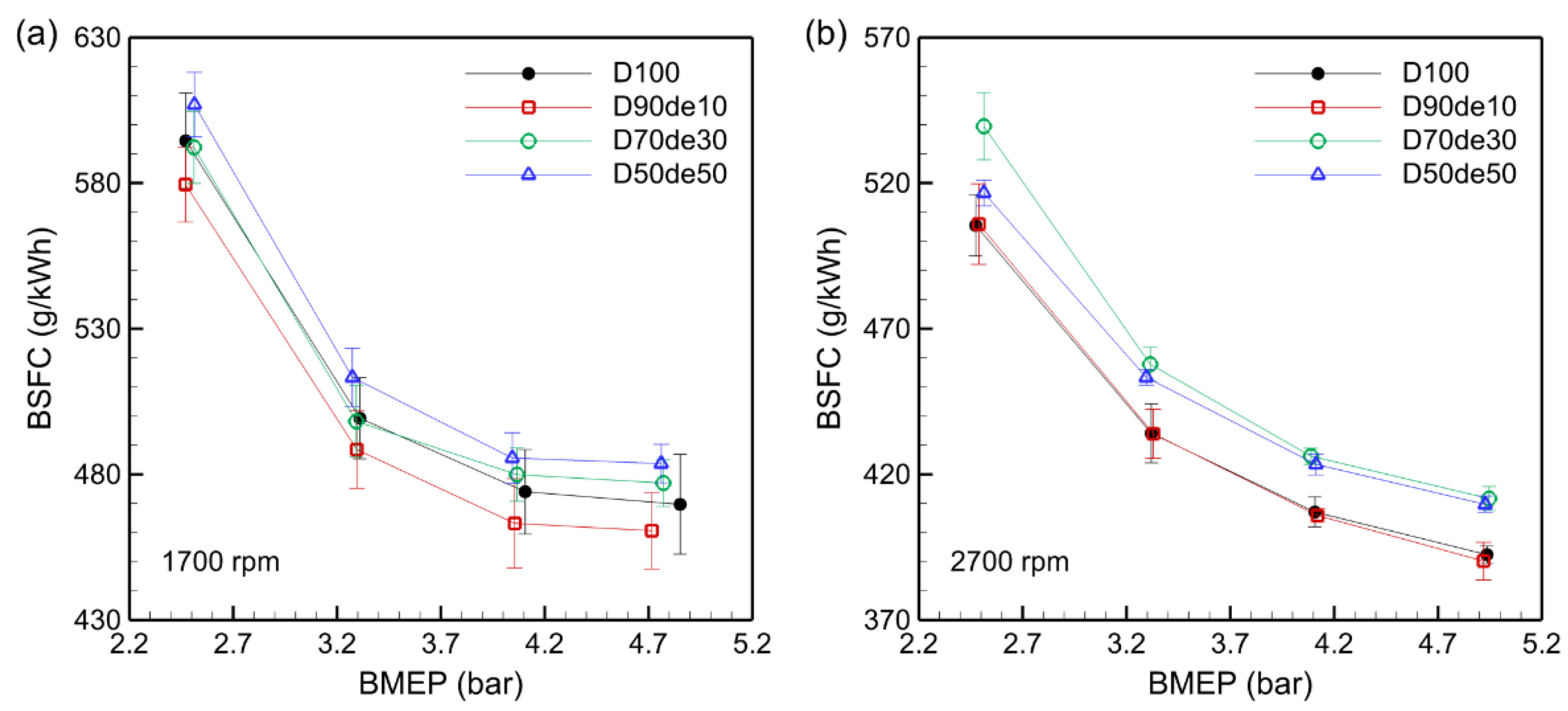

3.2. Brake Specific Fuel Consumption

BSFC is the amount of fuel consumed to produce a unit of power and is an essential indicator for evaluating the fuel economy and its environmental impact. The higher the BSFC, the more fuel is consumed, which increases operating costs and can generate more exhaust gas. The calorific value of the fuel is the dominant factor in BSFC, and since the LHV of decanol (41.9 MJ/kg) is about 2.4% lower than that of diesel, more fuel is needed to generate the same power, which is the main cause of the increase in BSFC.

Figure 3 clearly shows the decreasing trend of BSFC with increasing BMEP for all fuels. This is because the amount of fuel injected increases as the load increases, leading to increased heat release. The resulting increase in combustion chamber temperature and pressure promotes the combustion reaction. In addition, the heat loss due to excess air is reduced due to the lower AFR, so the heat released by the combustion reaction can be used more efficiently.

At 1700 rpm, BSFC increases as the decanol blending ratio increases; in particular, D90de10 has a lower BSFC than D100. At 2700 rpm, BSFC is relatively lower than at 1700 rpm, which is due to the turbulent flow inside the combustion chamber being strengthened at high speeds, allowing more uniform mixing of fuel and air, more stable combustion, and reduced incomplete combustion. At high speed, BSFC is highest for D70de30. Although combustion efficiency might improve due to the oxygen content, the high viscosity impedes uniform fuel injection, hindering air mixing, thereby reducing combustion efficiency and causing BSFC to increase. Additionally, the fuel is not sufficiently vaporized owing to reduced intake air; this suppresses the early-stage combustion temperature increase, delays the combustion reaction, and causes an increase in BSFC. This trend has also been confirmed in previous studies, which have reported that oxygenated fuels with high viscosity and low calorific value can cause a decrease in combustion efficiency and increase BSFC [

32,

33].

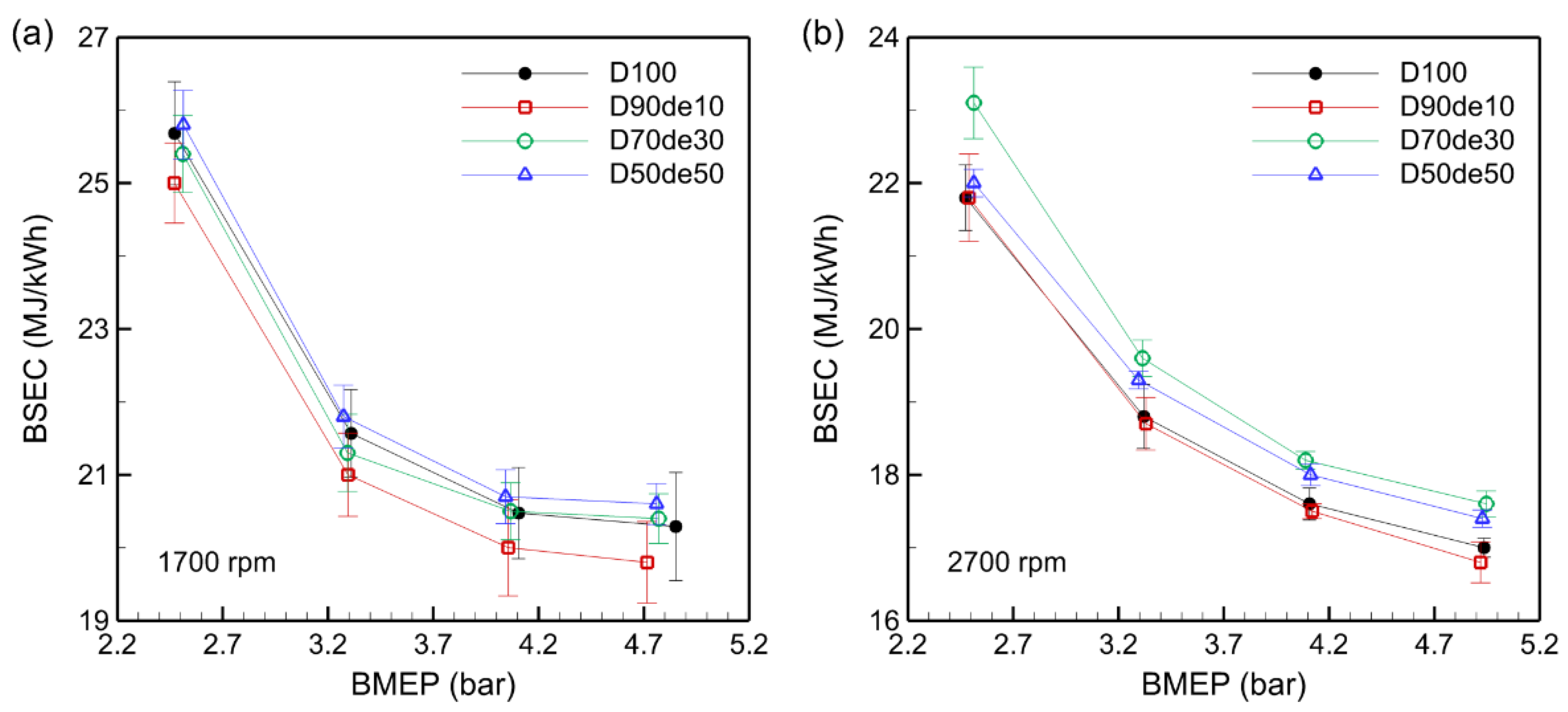

3.3. Brake Specific Energy Consumption

BSEC measures the energy consumed by fuel to generate a unit of power, serving as an indicator of energy efficiency. Unlike BSFC, which focuses on fuel consumption, BSEC offers a different perspective on fuel performance. This is important for an objective comparison of energy efficiency between fuels with different calorific values.

As shown in

Figure 4, BSEC at 1700 rpm was higher than that at 2700 rpm due to low temperature inside the combustion chamber during low-speed operation, slowing down the combustion reaction and increasing heat loss due to excessive air intake. At 2700 rpm, the high speed led to more uniform mixing of fuel and air, while the increased temperature and pressure in the combustion chamber promoted a more active combustion reaction, slightly reducing energy consumption.

When D90de10 and D70de30 were used at 1700 rpm, BSEC was lower than that of D100 overall, but at 2700 rpm, BSEC was lower than that of D100 only for D90de10. This means that decanol blending is relatively effective in low-speed operation. Air and fuel mix less actively at low speeds, increasing the likelihood of incomplete combustion. However, the oxygen content in decanol helps compensate for this, reducing local incomplete combustion and enhancing combustion efficiency. This reduces BSEC and can increase energy consumption efficiency.

Moreover, at low speed, the combustion chamber temperature is lower than at high speed, so the cooling effect is relatively less significant. The higher AFR and longer residence time increase the contact between fuel and air, allowing the combustion reaction to occur more uniformly. This improves combustion efficiency and helps reduce BSEC. On the other hand, since the engine used in the experiment is air-cooled, it can be understood that the high calorific value and cooling limitations can have a negative effect on efficiency at high speed, but the thermal management ability has minimal impact on BSEC at low speed.

3.4. NOx Emissions

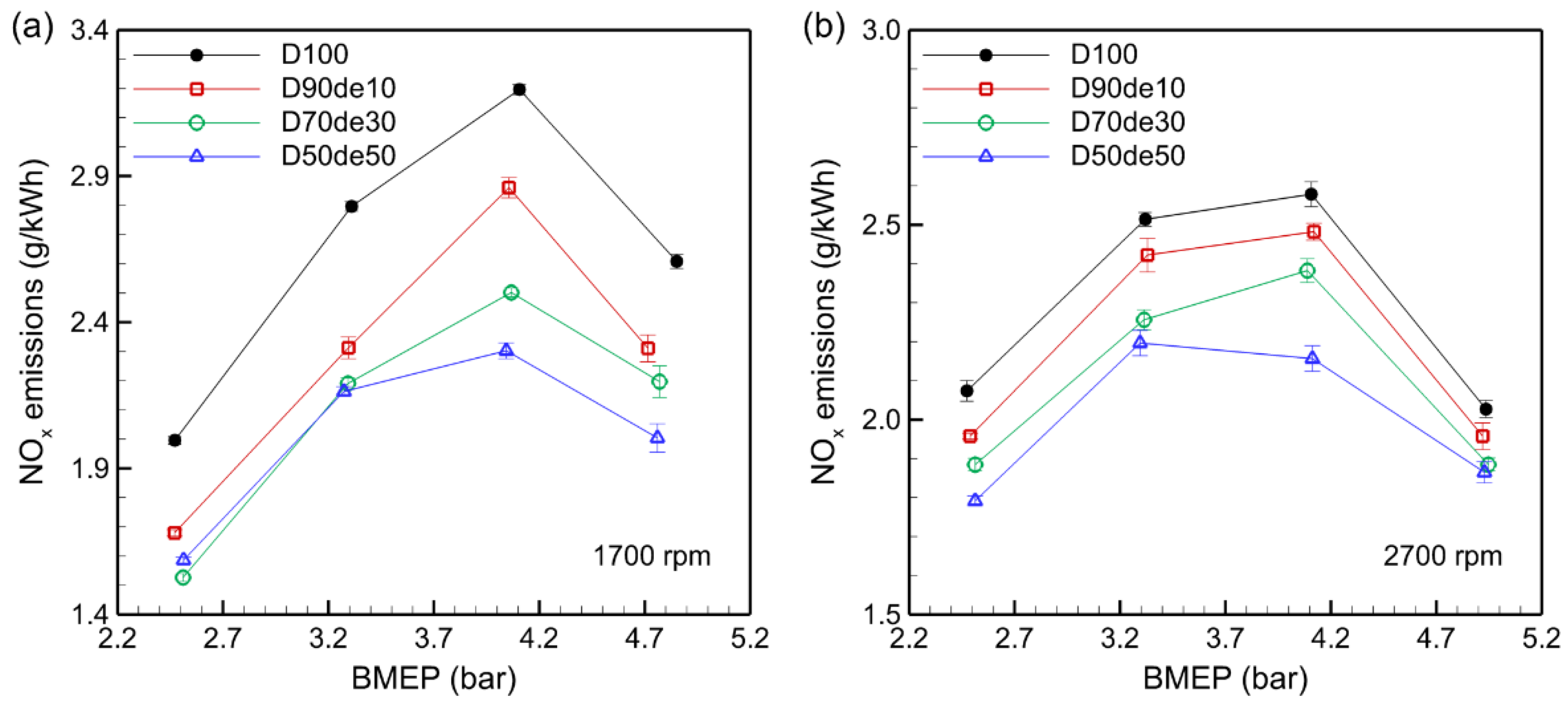

NO

x emissions are primarily produced during high-temperature combustion processes through the reaction of nitrogen and oxygen in the air, and their levels tend to increase as engine loads or combustion temperatures rise.

Figure 5 illustrates the trends of NOx emissions according to the decanol blending ratio and BMEP at 1700 rpm and 2700 rpm, showing a clear tendency for NOx emissions to decrease with increasing decanol ratios at each speed. For instance, when the BMEP was 4.11 bar at 1700 rpm, NO

x emissions from D100 were 3.20 g/kWh, decreasing to 2.30 g/kWh for D50de50. A similar trend is observed at 2700 rpm, where NOx emissions dropped from 2.58 g/kWh with D100 to 2.16 g/kWh with D50de50.

As BMEP rises, pressure and temperature inside the combustion chamber increase, providing sufficient activation energy and promoting NOx formation. However, under the experimental conditions in this study, the AFR is lower than the theoretical AFR at the maximum BMEP of 4.9 bar, which decreases the oxygen concentration in the combustion chamber and limits NOx formation. Decanol enhances combustion stability and reduces incomplete combustion due to its oxygen content. However, its high latent heat of vaporization and lower calorific value decrease the combustion temperature, thereby suppressing NOx formation, which predominantly occurs at high temperatures. These properties are particularly effective in reducing NOx emissions under high-load conditions.

During high-speed operation, the combustion chamber temperature is already sufficiently high, so the cooling effect of decanol is relatively less effective, limiting the temperature reduction. Conversely, at low speeds, where the combustion chamber temperature is lower, the latent heat of vaporization has a larger impact, helping to suppress the temperature and contributing to NOx reduction. Additionally, under high-speed conditions, turbulent mixing inside the combustion chamber is enhanced, making the fuel-air mixture more uniform and reducing local hot spots, which helps to lower NOx production.

However, the high viscosity of decanol can negatively affect fuel atomization. It may cause localized unstable combustion reactions, indicating that further research is needed to assess its complex effects on NOx reduction quantitatively. Moreover, the air-cooled engine used in this experiment has limitations in thermal management compared to a water-cooled engine, making it more prone to overheating at high speeds. Accordingly, decanol-blended fuel may be less effective in reducing NOx at higher speeds. Future studies should optimize the decanol and diesel blending ratio and injection strategy for more efficient NOx reduction.

3.5. CO Emissions

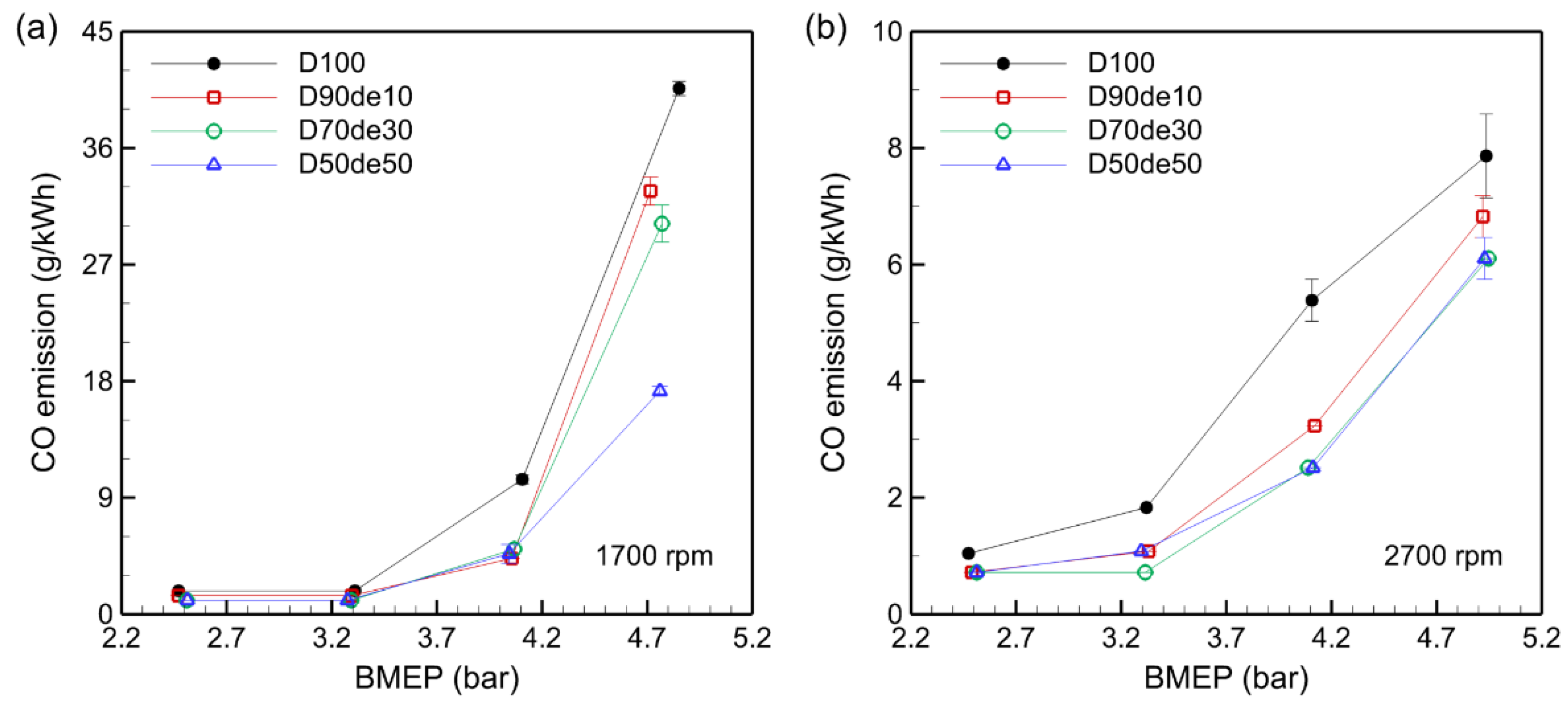

CO is a colorless, odorless, toxic gas mainly produced under rich combustion conditions, with formation more likely when the combustion temperature is low, or the air-fuel mixture is uneven.

Figure 6 depicts the CO emission trend according to the decanol blending ratio and BMEP, and it is clearly shown that CO concentration increases as BMEP increases in all fuel mixtures. This occurs because, as BMEP increases, the mixture in the combustion chamber becomes richer, leading to local oxygen-deficient zones that inhibit CO oxidation and increase CO emissions. Under low-load conditions, a leaner air-fuel mixture results from a higher AFR than the stoichiometric value, supplying sufficient oxygen to fully oxidize CO and reduce emissions.

At 1700 rpm, CO emissions are higher overall, primarily because the combustion temperature decreases during low-speed operation. This slows the CO oxidation reaction rate and increases incomplete combustion, raising CO emissions. For D100, CO emissions were 40.6 g/kWh at 1700 rpm and 7.9 g/kWh at 2700 rpm under BMEP 4.9 bar, indicating a difference of up to fivefold.

As the decanol blending ratio increased, CO emissions decreased under most conditions. Under BMEP 4.9 bar conditions at 1700 rpm, CO emissions of D100, D90de10, D70de30, and D50de50 were 40.6 g/kWh, 32.7 g/kWh, 30.2 g/kWh, and 17.2 g/kWh, respectively, with the CO reduction being the most prominent at approximately 58% in D50de50. The oxygen content in decanol promotes CO oxidation even in fuel-rich zones, helping to suppress CO emissions.

However, the high viscosity of decanol may adversely affect fuel atomization and mixing, potentially creating localized fuel-rich regions. This study confirmed that decanol’s oxygen content offsets viscosity-related drawbacks, aiding CO emission reduction. In conclusion, decanol-blended fuel, an oxygenated fuel, effectively reduces CO emissions by promoting CO oxidation in fuel-rich areas. This demonstrates the potential of decanol as an eco-friendly additive for diesel engines and proves its viability as a fuel blending strategy to reduce the environmental pollution of diesel engines in the future.

3.6. HC Emissions

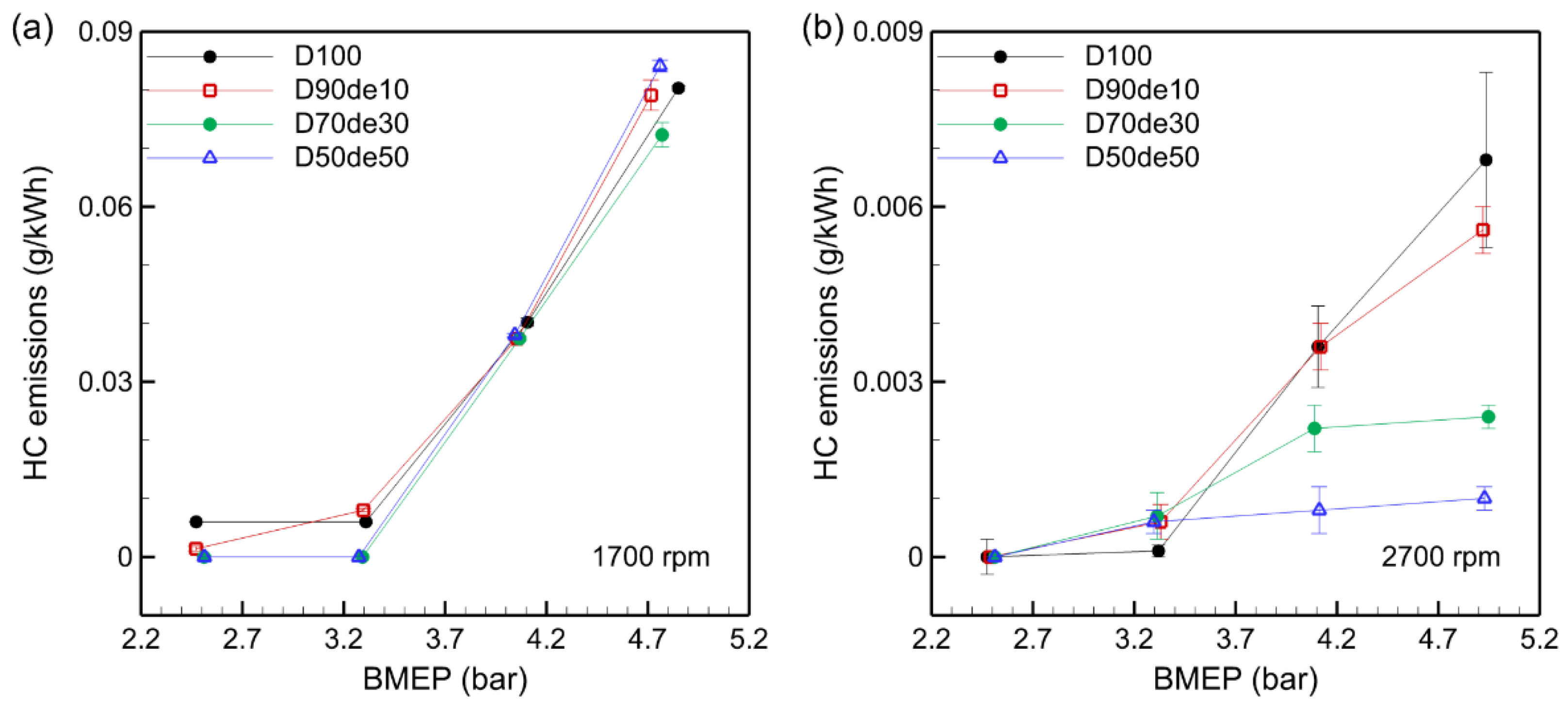

HC emissions are generated when fuel undergoes incomplete combustion and are influenced by uneven fuel spray, delayed evaporation, and other combustion inefficiencies.

Figure 7 illustrates the trend in HC emissions, showing that HC emissions tend to increase as the engine load rises. This results from fuel-rich zones formed in the combustion chamber as BMEP increases, which promotes incomplete combustion. For example, in D100, when BMEP increases from 2.47 bar to 4.85 bar at 1700 rpm, HC emissions increase more than tenfold, from 0.006 g/kWh to 0.08 g/kWh. This indicates the difficulty of achieving complete combustion under high-load conditions.

Although adding decanol to diesel fuel generally reduces HC emissions, the reduction effect is relatively small compared to D100 at 1700 rpm. This is because the combustion chamber temperature decreases due to the high latent heat of vaporization of decanol at low speed, delaying the combustion reaction and causing incomplete combustion, which limits the HC reduction effect. In contrast, at 2700 rpm, there is a clear tendency for HC emissions to decrease as the decanol blending ratio increases. This is because the combustion chamber temperature is sufficiently high at high speed. Hence, the cooling effect is relatively small, and the oxygen component of decanol promotes the combustion reaction in fuel-rich zones.

The results of this study suggest that combustion efficiency and HC emissions can vary significantly depending on fuel composition, engine load, and engine speed, emphasizing the need for further research to find the optimal decanol blending ratio. Adjusting the decanol blending ratio according to load and engine speed is expected to reduce environmental pollution by improving diesel engine combustion efficiency and lowering harmful exhaust gases, including HC emissions.

3.7. Smoke Emissions

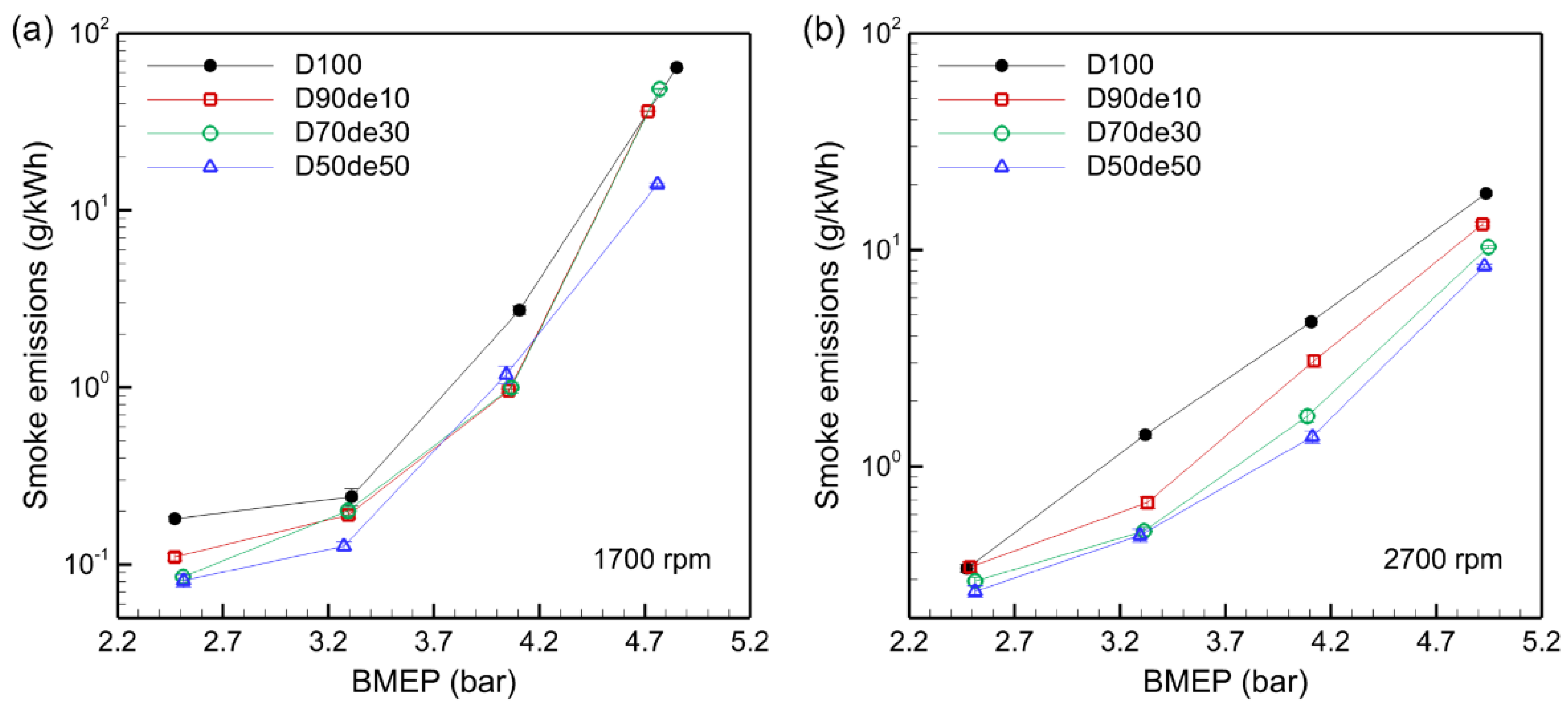

Smoke is a complex mixture of fine solid particles, liquid droplets, and gases produced during incomplete combustion, primarily due to oxygen deficiency and non-uniform fuel spray in the combustion process.

Figure 8 shows that smoke emissions increase with BMEP across all fuel mixtures. Combustion temperature rises as engine load increases, leading to incomplete combustion in fuel-rich zones. Conversely, a lean combustion environment is formed at low loads due to an AFR higher than the stoichiometric value, rapidly reducing CO and smoke emissions.

While decanol-blended fuel helps reduce smoke emissions overall, the smoke reduction effect of decanol was less pronounced at 1700 rpm than at 2700 rpm. This is because low combustion chamber temperatures at low speeds delay the combustion reaction, and the cooling effect of decanol’s high latent heat of vaporization further increases incomplete combustion, limiting smoke suppression. For example, at a BMEP of 4.85 bar, D50de50 demonstrates a noticeable smoke suppression effect; however, other decanol blends show limited impact on smoke reduction under low-speed, high-load conditions.

In contrast, at 2700 rpm, the smoke reduction effect of decanol blending becomes significant. When the combustion chamber temperature is sufficiently elevated at high speeds, decanol’s oxygen content promotes combustion, effectively suppressing incomplete combustion and reducing unburned carbon particle formation. For example, under BMEP 4.11 bar, D100’s smoke emission was 4.66 g/kWh, but D50de50 reduced this by about 63% to 1.71 g/kWh. This occurs because, at high speed, turbulent mixing in the combustion chamber enhances fuel-air mixing uniformity, while the oxygen in decanol aids in suppressing incomplete combustion. In conclusion, decanol-blended fuel effectively suppresses smoke emissions under certain conditions, highlighting its potential as a blending strategy to reduce diesel engine emissions and environmental impact.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effects of various decanol blending ratios on diesel engines’ combustion efficiency and emission characteristics by comprehensively analyzing engine performance and exhaust gas characteristics under various engine loads and speeds. This study aimed to provide foundational data for establishing an eco-friendly fuel blending strategy for diesel engines.

The performance parameter BTE showed different trends depending on engine speed and load. At low speed (1700 rpm), BTE tended to decrease slightly as the decanol blending ratio increased, but there was no clear relationship between the blending ratio and BTE at high speed (2700 rpm). BSFC and BSEC both tended to increase with higher decanol ratios, as the calorific value of decanol is lower than that of pure diesel, requiring more fuel for the same power output.

In terms of emissions, increasing the decanol blending ratio effectively reduced NOx, CO, HC, and smoke emissions. NOx emissions were lowered by the cooling effect from decanol’s higher latent heat of vaporization and lower calorific value, especially at low speeds. CO and HC emissions declined in most conditions, as decanol’s oxygen content promoted oxidation in fuel-rich zones, reducing incomplete combustion. CO emissions remained higher at low speeds, likely due to lower combustion temperatures, which limited CO oxidation. Decanol blends were more effective at reducing CO and HC emissions at high speed due to increased combustion temperatures and the oxygen supply effect.

Smoke emissions also decreased as the decanol blending ratio increased, as the oxygen content in decanol promoted fuel oxidation in rich zones, reducing unburned carbon particles. However, under low-speed conditions, the higher viscosity and latent heat of vaporization of decanol delayed combustion, limiting the smoke suppression effect compared to high speed.

In conclusion, the blended fuel of decanol and diesel can be considered a promising alternative fuel for reducing harmful exhaust gases and improving the combustion efficiency of diesel engines. Further studies are recommended to determine the optimal blending ratio and operating conditions. This study also suggests the potential for developing a commercial eco-friendly fuel using decanol and highlights the need for optimizing injection technology and timing to enhance diesel engine performance.