1. Introduction

Congenital hepatic hemangiomas (CHH) are benign, high-flow vascular tumors that proliferate during the intrauterine period and are fully developed at birth without any postnatal proliferation [

1]. Although most of these tumors present as single, asymptomatic lesions, some can be life-threatening due to complications such as intratumoral hemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, and high output cardiac failure [

1,

2].

The classification and nomenclature of hepatic hemangiomas (HH) have varied widely over the years. In 2007, a systematic classification scheme for HH was first proposed, dividing the lesions into focal, multifocal, and diffuse types [

3]. Five years later, this classification was validated by the Liver Hemangioma Registry at Boston Children’s Hospital, confirming that focal lesions corresponded to HH [

4]. Finally, in 2018, the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) divided HH into CHH and infantile hepatic hemangioma (IHH). These changes reflect a greater understanding of the biological behavior of CHH, confirming that they are distinct from multifocal and diffuse lesions considered IHH, while also presenting a parallel life cycle to their cutaneous counterpart.

Initially, it was hypothesized that all CHH were rapidly involuting congenital hepatic hemangiomas (RICHH) [

5]. However, some patients with CHH-type lesions have been described as showing minimal or no involution during follow-up periods longer than one year [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Although cutaneous non-involuting congenital hemangiomas (NICH) have been widely studied and described in the literature, this has not been the case for their hepatic counterpart, with no series characterizing their postnatal behavior. Classically, cutaneous NICH do not involute but rather persist and grow in proportion to the child; [

9] nevertheless, we observed different patterns of evolutions in liver. We present our series of non-involuting congenital hepatic hemangiomas (NICHH) to characterize their clinical, radiological, histological, and genetic course, as well as to share our experience in treating these lesions with sirolimus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collected

We conducted a retrospective review of patients diagnosed with HH or referred to our center between 1991 and 2022. Patients diagnosed with CHH were selected, and those with NICHH were identified. The variables analyzed included baseline patient characteristics and lesion features (location and size), time of diagnosis, alpha-feto protein (AFP) levels, presence of associated cutaneous hemangiomas, symptoms, radiological findings, histological analysis, genetics, follow-up, and treatment. For patients treated with sirolimus, we assessed dosage, blood levels, treatment response, and any complications.

2.2. Diagnosis, Follow Up and Treatment

The diagnostic process of suspected NICHH was initiated during the follow-up of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CHH. Patients were included in the study if their liver lesions remained stable at least 18 months or more, leading to a diagnosis of NICHH [

6]. Doppler ultrasound was performed at the time of the initial diagnosis for all patients. However, in the diagnosis was unclear, contrast-enhanced MRI was conducted. All patients underwent regular monitoring with ultrasound, initially on a monthly basis and then every 3 months once the lesion stabilized. A panel of expert pediatric radiologist reviewed the imagining studies and confirmed the absence of involution within the first 18 months in all cases.

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: loss of follow-up after imaging diagnosis of HH or imaging follow-up with ultrasound or MIR for less than 18 months.

When radiologists were unable to reach a definitive diagnosis, or if lesion growth was detected in consecutive controls, a biopsy was performed to rule out malignancy and confirm diagnosis. Histological and genetic studies of the lesion were conducted in these cases.

Given the evidence of positive response in patients with other vascular anomalies and similar mutations [

10,

11,

12,

13], treatment with sirolimus was proposed for patients with NICHH. Sirolimus treatment was recommended according to our center’s protocol developed by the vascular anomalies unit. The parents and/or legal guardians of the all patients accepted treatment with sirolimus as compassionate use after being informed of the benefits, risks, and other therapeutic options. Treatment was indicated for giant hemangiomas (defined as having a main diameter ≥ 4 cm) to reduce the necessity for surgical resection and to mitigate the risk of spontaneous and/or traumatic rupture. Therapy with sirolimus was initiated at the recommended dose of 0.8 mg/m

2/12 h. Patients continued to be monitored through ultrasound and MRI to assess their response to therapy. Side effects were evaluated through comprehensive physical examinations and blood test every three months. The blood tests included a complete blood count, biochemical panel, electrolytes, liver function tests, lipid profile, kidney function tests, and sirolimus levels.

2.3. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted, presenting the data as percentage of the total and medians with their respective ranges. Additionally, a literature review was performed on focal congenital hepatic hemangiomas that persist after the first two years of life. A systematic search was carried out in electronic databases (PubMed, Google Scholar and Clinical Trials) for articles in English and Spanish that included the following terms: “liver hemangioma”, “hepatic hemangioma”, “liver angioma”, “focal hepatic hemangioma”, “focal hepatic angioma”, “congenital hepatic hemangioma”, “congenital hepatic angioma”, “congenital hepatic hemangioendothelioma”, “infantile”, “children”, “childhood” and “adolescent”.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of seven patients were included in this study. The clinical and demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. There was a predominance of females (71.4%). Only two patients (28.6%) were diagnosed prenatally by US, and all were term newborns. Most patients were asymptomatic at birth (71.4%), although two presented with hepatomegaly and an abdominal mass without complications. AFP levels were documented as normal in all patients, and none of the liver lesions were associated with cutaneous hemangiomas.

Most of the lesions were located in the right hepatic lobe (RHL) (71.4%). Histological analysis was available for three patients, all of whom were diagnosed with CHH. In each case, the endothelium stained positive for CD31 and CD34, while showing negative results for Glut-1 and D2-40. Small vascular lobules surrounded by fibrous tissue were identified, with no signs of involution.

Genetic studies were conducted on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples from one patient using a custom next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel of 56 genes related to vascular anomalies, along with a custom bioinformatic pipeline for detecting somatic mosaicism and Droplet Digital PCR for variant validation. The average on-target coverage for NGS ranged from 32 to 800 sequencing reads per base pair after duplicate removal. Variants were excluded as potential disease candidates based on their presence in >0.01% population (according to the 1000 Genomes project [

http://www.internationalgenome.org/], and the Exome Aggregation Consortium [ExAC;

http://exac.broadinstitute.org]), pathogenicity predictors, and descriptions in the scientific literature. Our molecular analysis identified a pathogenic

GNAQ variants: c.626A

≥T; p.Gln209Leu.

3.2. Follow-Up and Radiological Characteristics

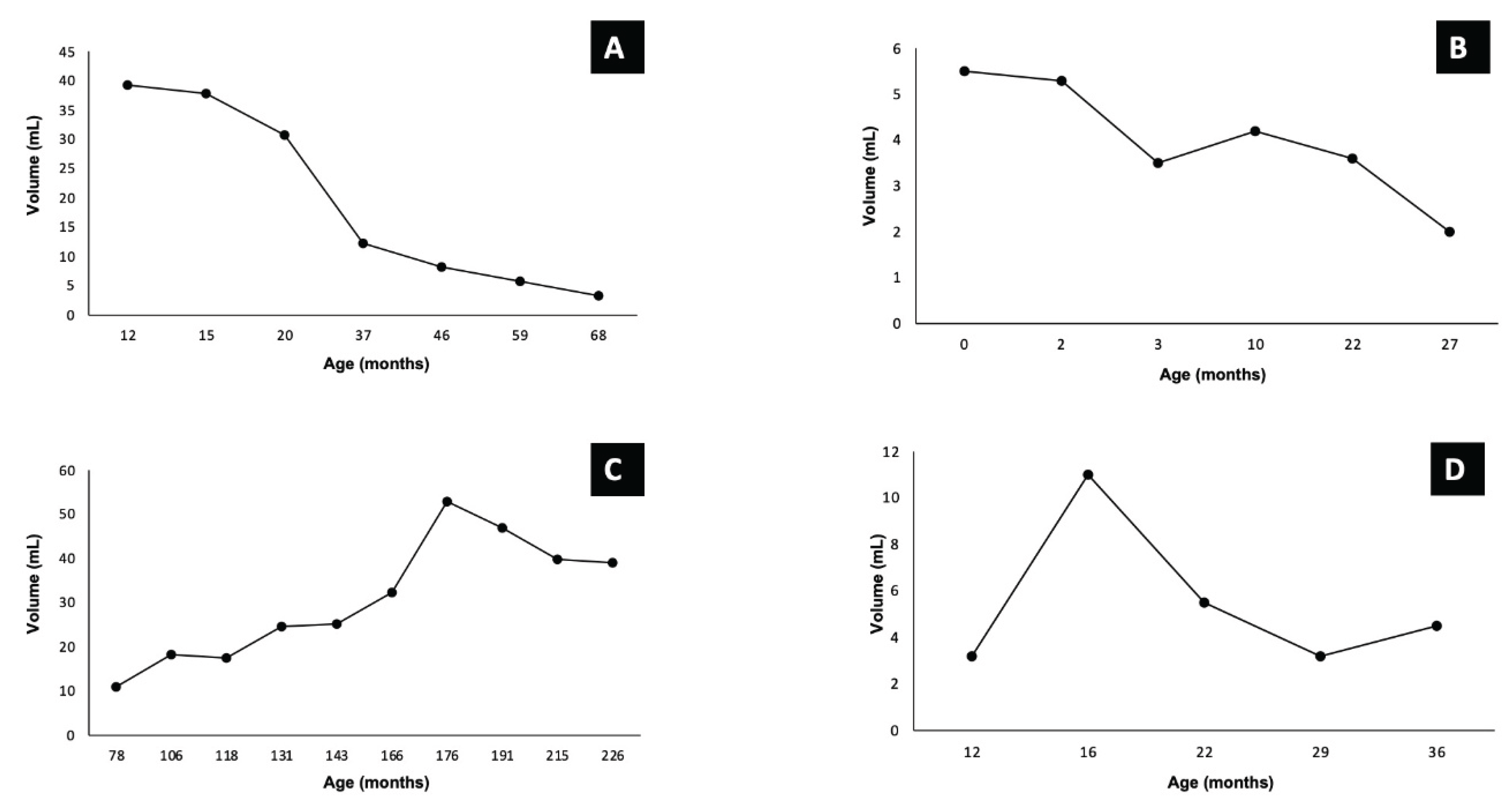

The median follow-up period was 75 months (range: 35-191months), and all patients remained alive. Among the four patients who did not receive any medication, two exhibited delayed involution (

Figure 1A,B

), while the other two later experienced tardive growth (

Figure 1C,D).

Most lesions appeared as solid tumors on ultrasound, characterized by poorly defined borders and multiple ill- defined hypoechogenic areas, which corresponded to vascular structures confirmed by Doppler imaging. Many of these lesions also contained gross calcifications.

On MRI, all the lesions exhibited hyperintense signal changes on T2-weighted images (T2-W1) and hypointense signal changes on T1- weighted images (T1-W1), with serpiginous signal voids indicative of intralesional vessels. Only one lesion showed a portosystemic shunt, connecting the anterior branch of right portal vein to a prominent draining vein that emptied into the middle hepatic vein.

After reviewing all imaging studies, no specific radiologic features were significantly associated with a particular evolutionary pattern of NICHH.

3.3. Treatment and Sirolimus

In three patients with lesions larger than 4 cm and no signs of involution, treatment with sirolimus was initiated. Data of patient’s treatment and outcome are summarized in

Table 2.

Sirolimus therapy was started at a median age of 30 months (range: 12-49 months) and continued for a median duration of 39 months (range: 34-45 months). Therapeutic drug monitoring was performed for all patients, maintaining sirolimus levels within the target range of 4 and 12 ng/mL. No side effects were observed besides self-limiting mucositis in one patient, and no dose adjustments were necessary.

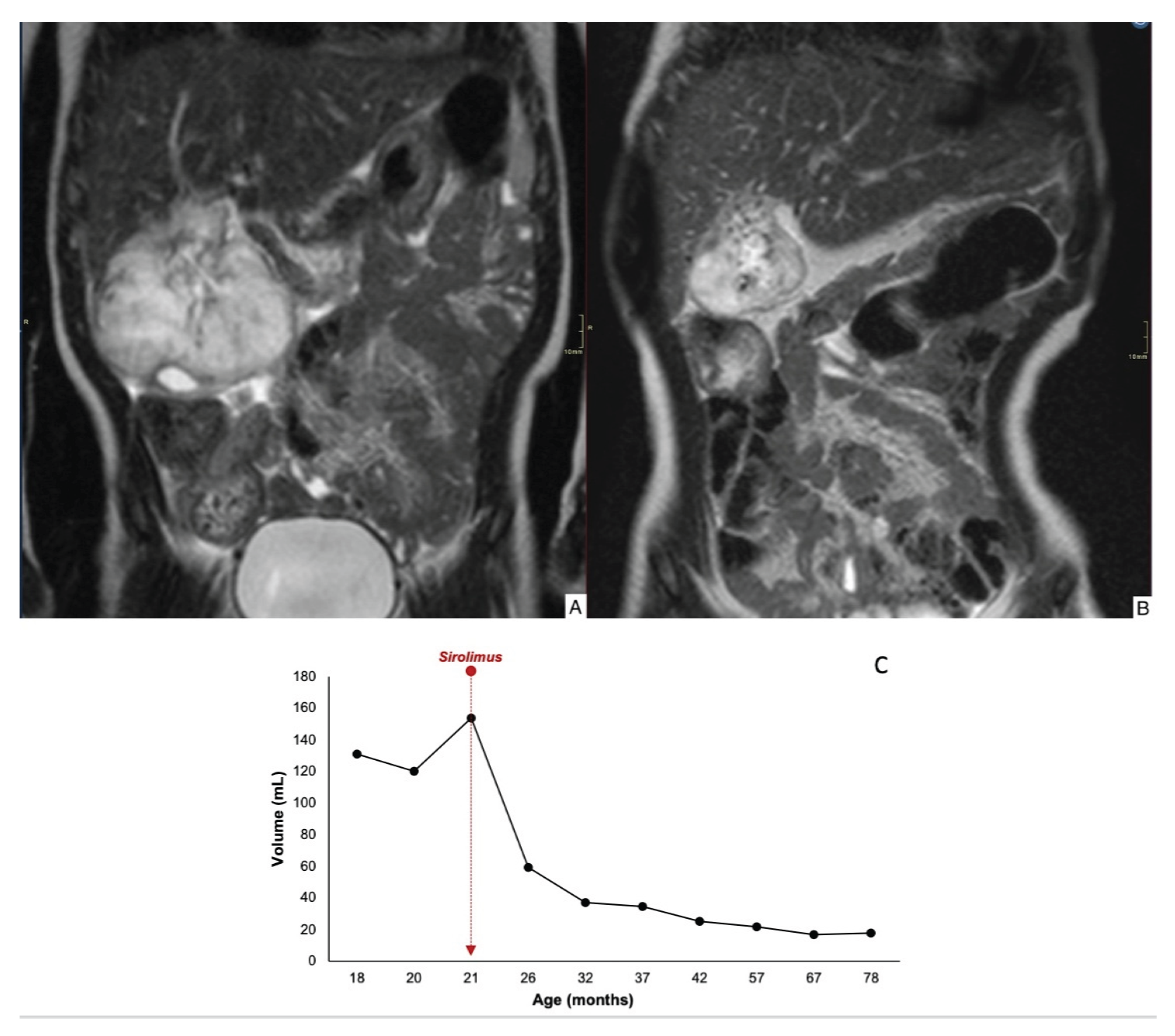

Case 1 demonstrated an 84% reduction in lesion volume, with decreased contrast uptake in the periphery and completely regression by 78 months of age (

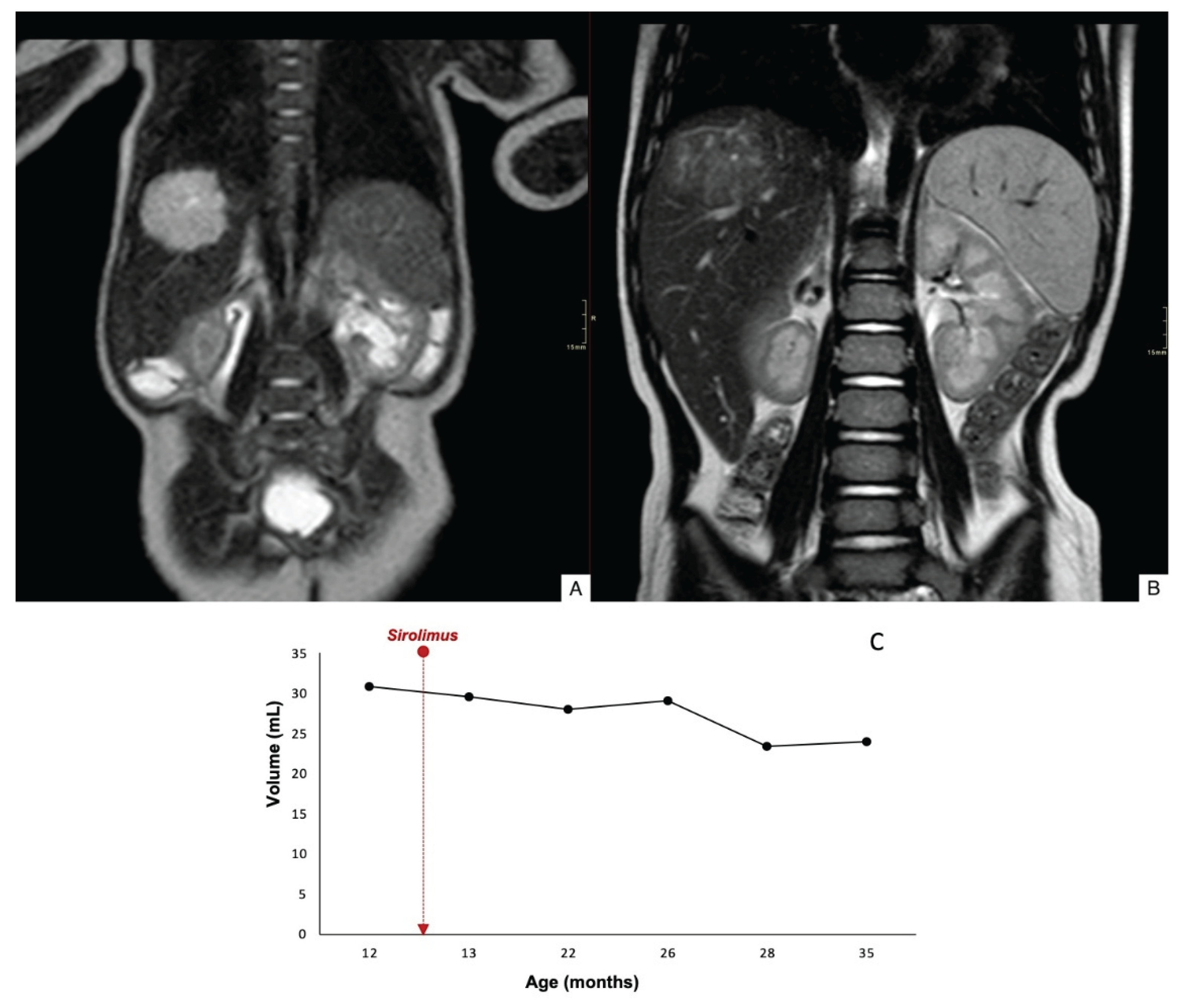

Figure 2). Case 2 showed a mild reduction in lesion size, and there was worsening contour definition and reduced contrast uptake. The lesion remained stable at 35 months of age (

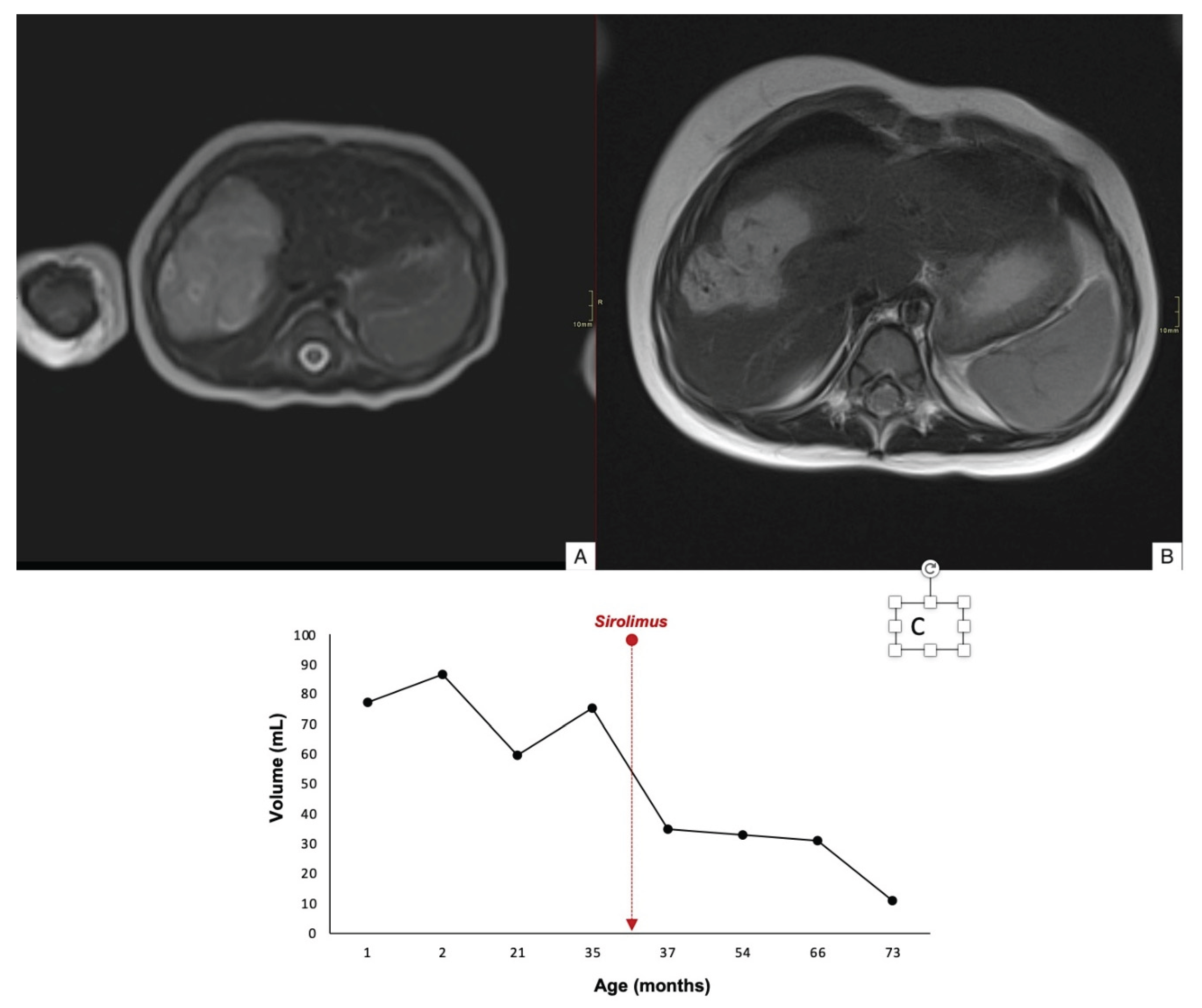

Figure 3). Case 3 exhibited a 60% reduction in tumor volume; however, complete involution did not occur, and portosystemic fistulas persisted (

Figure 4).

After one year of continuous excellent response to therapy and lesion stability, we decided to gradually reduce the treatment dose in Case 1. Once we confirmed that there was no increase in lesion size or rebound effect, we discontinued the treatment. The other two patients remain on treatment at the time of this report.

4. Discussion

This study represents the largest series describing NICHH, confirming their existence and characterizing their patters of evolution. Most reports on CHH indicate a biological behavior and involution pattern similar to cutaneous congenital hemangiomas [

5,

6,

7]. Despite this similarity, only a few cases have been documented in the literature as NICHH. In 2012, Kulungowski

et al. [

5]. described a focal HH that showed no change after three years of follow-up. Recent reviews on the characteristics of CHH report similar findings: one study noted two patients who exhibited no radiological changes after 24 and 72 months, another reported two cases of non-involuting tumors after more than one year, and the most recent identified two out of 13 patients with no evidence of involution [

6,

7,

8]. Considering the involution patterns of their cutaneous counterparts and based on these previous reports, we identified seven patients with NICHH, all of whom showed no changes or signs of involution during the first 18 months of follow-up.

Cutaneous NICH are characterized by a similar sex distribution and a predilection for the same locations [

14]. In contrast, our patients with NICHH exhibited a predominance of females and a higher proportion of tumors affecting the RHL. Given their presentation as large hepatic masses, the differential diagnosis of these lesions includes hepatoblastoma, mesenchymal hamartoma, and metastatic tumors in children. While normal AFP levels can help distinguish between malignant and benign tumors, AFP may remain elevated in CHH [

15,

16]. In this series, we did not observe alterations in AFP levels; however, we performed biopsies in three patients due to diagnostic uncertainty in imaging examinations. In this group, the histological features were confirmed, and the genetic variant

GNAQ: p.Gln209Leu was detected in one patient, findings that have been previously described by our group [

6].

In general, there is no consensus on the exact frequency of follow-up imaging for CHH. However, the guidelines for evaluating and monitoring HH emphasize the necessity of stablishing the evolutionary pattern of CHH. Most previous reports propose that RICHH reduce in size by approximately 80% by 12-13 months of age, while NICHH do not change significantly during follow-up, similar to cutaneous hemangioma [

15,

17]. In contrast, this cohort showed displayed different evolution patterns of NICHH. We observed a delayed regression in two patients who received no treatment; these lesions may correspond to Partially Involuting Congenital Hepatic Hemangioma (PICHH), which has not been previously described in liver.

On the other hand, the other two patients exhibited a later and small spontaneous increased in size. Although the radiological findings confirmed the diagnosis of CHH, we recommended biopsies in both cases, but the parents did not provide consent. We believe that these two NICHH cases may correspond to an evolution pattern recently described in cutaneous hemangioma called tardive expansion congenital hemangioma (TECH). This study reported 11 patients with NICH who exhibited the spontaneous and dramatic expansion between the ages of 12 months and 61 months [

9]. Like the authors of that study, we cannot explain the cause of this sudden growth; however, we believe that in these unusual cases, it is important to consider the possibility of them being TECH and rule out malignancy with biopsy before indicating a liver resection. Undoubtedly, the evolutionary patterns of CHH are not clearly established, and continuous follow-up over time is necessary to differentiate and define the type of CHH, as this is essential for making informed treatment decisions.

Guidelines on the treatment of CHH are currently limited. It is well established that if the patient is asymptomatic, observation and close surveillance are the recommended general treatment [

15]. In symptomatic patients with severe complications, giant lesions, no response to drug therapy, or absence of involution, embolization or surgical resection is considered. Although the tumor size and volume have not been not described as predictive factors for mortality [

18] a few studies have reported cases of CHH that underwent surgical resection due to lesions larger than 4 cm in diameter, suspicion of malignancy, or absence of involution after a prolonged period [

7,

8]. The median age of most patients with resected CHH in these studies was less than 1 year, suggesting that these tumors might have followed a NICHH-type evolution pattern, making surgical resection unnecessary and potentially avoiding associated surgical complications.

When assessing the risks of complications in the adult population with HH, Mocchegiani

et al. [

19]. reported on a series of 2,071 patients, identifying five cases of spontaneous HH rupture. Among these, four cases presented with hemoperitoneum, resulting in a rupture rate of 0.47% and a significant mortality of 20%. Their analysis led to the conclusion that surgical treatment should be considered in cases of peripherally located giant hemangiomas (defined as having a main diameter of ≥ 4 cm) exhibiting an exophytic growth pattern, as there carry a higher risk of rupture. Conversely, Donati

et al. [

20]. noted that spontaneous rupture of HH is rare and that preventive surgery should be reserved for specific patients with lesions larger than 11 cm. In our NICHH series, none of the patients experienced complications during the neonatal period or during follow-up, indicating an indolent behavior of these tumors.

There is insufficient evidence in the literature to support the successful use of pharmacological treatment for CHH. While a few reports describe the use of propranolol, corticosteroids, or vincristine (widely used in multifocal infantile hemangiomas), their effectiveness in treating focal congenital hemangiomas has not been proven. On the other hand, successful experiences with sirolimus in treating other vascular conditions associated with

GNAQ mutation, as well as in neonates with complicated CHH, alongside our extensive experience in managing various vascular anomalies with sirolimus, prompted us to consider its use in three patients with NICHH [

10,

11,

12,

13,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Two of our cases demonstrated a moderate response, with more than 50% reduction in lesion size after 15 months of treatment, while the third case exhibited a mild response. These findings suggest that sirolimus treatment may effectively reduce the size of these lesions or accelerate their involution. Therefore, we recommend initiating pharmacological treatment for lesions larger than 4 cm to mitigate potential complication of traumatic rupture or the need for surgical intervention.

The heterogeneity in the use of the term “hemangioma” over the years, combined with limited data on NICHH, has delayed their complete characterization and hindered adequate patient registration in the literature. We have identified 29 cases in the literature of patients presenting with non-involuting focal hepatic lesions persisting beyond 24 months of life [

2,

4,

6,

7,

8,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Despite the lack of histologic diagnosis in most cases, we conjecture that these described lesions are all NICHH. Expanding our review to include adult hepatic vascular neoplasms, we discovered a distinct type of liver vascular tumor with uncertain malignant potential, recently referred to as hepatic small vessel neoplasm (HSVN). Although the pathogenesis of HSVN is unclear, mutations in the

GNAQ have been identified, similar to those found in CHH [

29,

30,

31,

32]. This similarity in G proteins mutations may suggest a common origin for both types of vasoformative tumors. In our series, most patients were diagnosed incidentally during childhood, indicating that other undiagnosed NICHH could remain unnoticed until adulthood and subsequently be classified ad HSVN. Therefore, it is essential to investigate and compare the genetic and histologic characteristics of both tumors to elucidate their relationship and confirm whether they correspond to the same neoplasm.