1. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a diverse family of oxidants derived from molecular oxygen during cell processes such as respiration and include both radical species like superoxide (O₂·⁻) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), as well as non-radical molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [

1]. Under normal physiological conditions, ROS are necessary components to various cellular processes, such as signaling and metabolic pathways, and the maintenance of redox homeostasis [

1,

2]. These physiological levels of ROS contribute to what is known as oxidative eustress, which is essential for regular cell function by activating transcription factors like nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades [

3]. However, if the production of ROS exceeds the capacity of cellular antioxidant defenses, the resulting imbalance may lead to oxidative stress which causes cell and tissue damage [

4].

One significant target of ROS during oxidative stress is the extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM is a complex network of structural proteins such as collagens and elastin, glycoproteins like fibronectin, and proteoglycans, including glycosaminoglycans like hyaluronic acid (HA) [

5]. Beyond providing structural support to tissues, the ECM regulates crucial processes, including cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation [

6,

7]. Chemical modifications to ECM components caused by ROS can severely impact tissue integrity and repair [

8,

9]. For example, oxidative damage to collagen fibers compromises their structural stability, making them more susceptible to enzymatic degradation [

10]. Similarly, alterations to HA can result in increased fragmentation and in the loss of its viscoelastic and hydrating properties [

11]. These changes disrupt the ECM’s ability to mediate cell signaling and bind growth factors, further impairing tissue regeneration and repair [

12].

ECM degradation is particularly pronounced in chronic inflammatory conditions such as periodontitis, aging, and impaired wound healing [

13]. Excessive ROS production destabilizes the delicate balance between ECM synthesis and turnover, initiating destructive processes [

14]. For instance, in the gingival tissues affected by periodontitis, ROS-induced modifications to proteoglycans alter their core proteins and glycosaminoglycan chains, impairing their ability to regulate tissue homeostasis [

15].

Addressing ROS-induced ECM damage is crucial, given the ECM’s pivotal role in maintaining tissue function and facilitating repair. Numerous research efforts are actively focused on this challenge [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, effective solutions must go beyond neutralizing ROS; they must also provide specific biochemical and structural cues to restore tissue integrity. To this effect, interventions capable of reestablishing a regenerative microenvironment under oxidative stress conditions are needed [

20,

21,

22].

Biomaterial scaffolds are particularly well-suited for this purpose, as they are a commonly used strategy to promote tissue repair and regeneration [

23,

24]. In particular, hydrogels have attracted attention as promising tools in tissue engineering [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Hydrogels are versatile, three-dimensional networks capable of mimicking the natural structure and function of the ECM [

29]. They are highly biocompatible and possess unique physicochemical properties, including high water content and porosity, making them ideal scaffolds for supporting cell adhesion and viability [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. By providing a biomimetic microenvironment, hydrogels facilitate cellular processes that are essential for tissue repair and regeneration [

35].

Polynucleotides HPT

TM and hyaluronic acid (HA) have shown significant potential as components of hydrogel scaffolds due to their combined biochemical and structural contributions. PN-HPT

TM, derived from DNA fragments, support cell vitality by providing a stable and physiological microenvironment [

36,

37]. HA, a major glycosaminoglycan in the ECM, is known for its viscoelasticity, hydrating properties, and useful scaffold characteristics to modulate tissue repair [

38,

39,

40,

41]. More recently, products with PN-HPT

TM and with PN-HPT

TM combined with HA have been proposed for improved tissue conditions and have demonstrated considerable clinical potential [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

Despite these advancements, the potential of PN-HPTTM and PN-HPTTM +HA hydrogels for mitigating oxidative stress has not been explored. We hypothesize that these hydrogels can effectively reduce ROS levels and thereby help preserve ECM integrity under oxidative stress conditions. Therefore, in this brief report, to investigate this hypothesis, we utilized a cell free in vitro model of H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress to assess the direct ROS-scavenging capabilities of these hydrogels.

2. Results and Discussion

The purpose of our investigation was to assess whether Polynucleotides High Purification Technology (PN- HPT

TM) could hamper ROS under challenging conditions that mimic the oxidative stress associated with harmful tissue and organ conditions [

53]. To this purpose, we relied on a cell-free model we previously developed and chacterized to evaluate H₂O₂-induced ROS [

54]. This approach allowed us to focus on direct ROS-scavenging activity, minimizing confounding variables such as cellular metabolism or signaling.

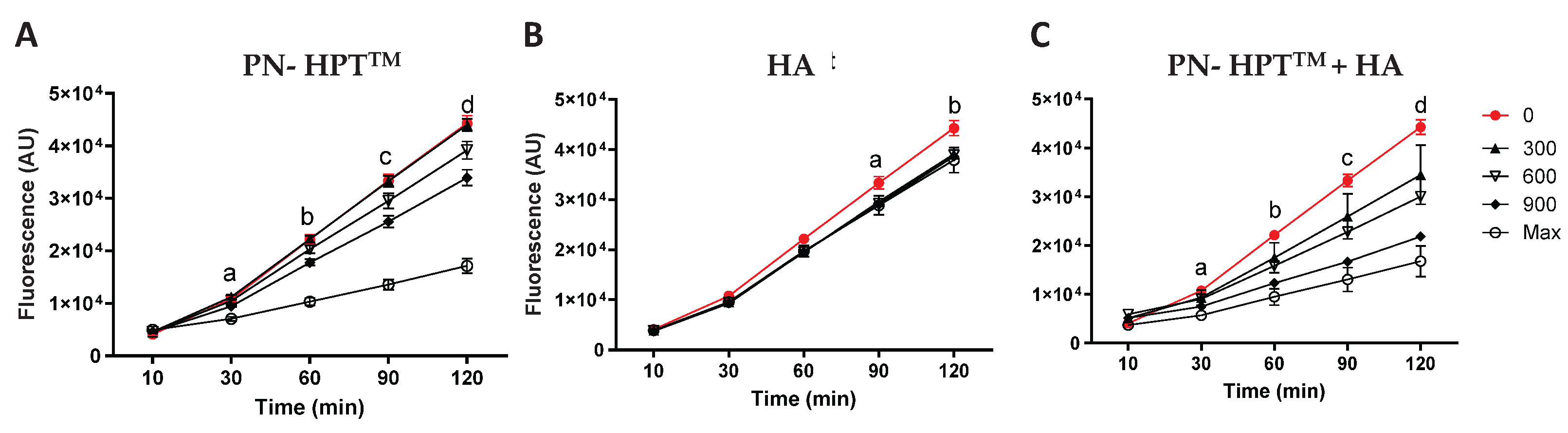

Figure 1 illustrates fluorescence levels measured using the Calcein-AM probe for PN-HPT

TM (

Figure 1A), HA (

Figure 1B), and PN- HPT

TM +HA (

Figure 1C) products at different concentrations of these compounds (300, 600, and 900 μg/mL, including the maximum concentration) over time (10, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after H₂O₂ addition).

As visible in

Figure 1, the rising intensity of Calcein-AM fluorescence in the control group (0 μg/mL, red line) indicated that ROS levels progressively increased over time after addition of H₂O₂. PN-HPT

TM products exhibited a strong, dose-dependent scavenging activity, as evidenced by significantly reduced fluorescence at concentrations ≥900 μg/mL (

Figure 1A). At the highest concentration, PN-HPT

TM products significantly lowered fluorescence as early as 30 minutes after H₂O₂ exposure. Lower concentrations produced statistically significant reductions later, around 60–120 minutes. These observations underscore the robust antioxidant properties of PN-HPT

TM compounds and suggest that sufficient PN-HPT

TM concentration can rapidly and effectively neutralize free radicals. This aligns with reports suggesting that nucleotides or nucleotide-containing fragments can act as scavengers for multiple ROS species, possibly by directly donating electrons or forming stable complexes that inhibit radical propagation [

55].

Hyaluronic acid (HA) alone based-products also reduced fluorescence intensity compared to the control group, though their effects were less pronounced than those of PN-HPT

TM or PN-HPT

TM +HA (

Figure 1B). HA’s scavenging activity was not strongly concentration-dependent, with statistically significant reductions observed starting at 90 minutes and only for the concentration of 600 μg/mL. Albeit limitedly, HA reduced ROS levels; however, its scavenging activity remained lower than that of PN-HPT

TM products at any concentration.

The PN-HPT

TM +HA combination demonstrated the most pronounced reduction in fluorescence intensity across all time points (

Figure 1C). At 60-120 minutes, PN- HPT

TM +HA significantly reduced ROS levels compared to the control, even at 600 μg/mL. This enhanced activity may result from complementary mechanisms of PN- HPT

TM and HA; we hypothesize that while specific chemical groups in Polynucleotides HPT

TM (e.g., nitrogenous bases) can directly interact with and neutralize free radicals, HA’s large, charged glycosaminoglycan structure might provide multiple additional reactive sites for binding or quenching ROS. However, the peculiar behavior of PN- HPT

TM +HA compounds could be also centered on HA’s high water-binding capacity, which could create a hydrophilic microenvironment that dilutes ROS or slows their diffusion, thus reducing their local concentration. Collectively, these properties suggest a synergistic interaction in which HA’s structural and hydrating functions support and amplify PN- HPT

TM’s direct radical-scavenging potential.

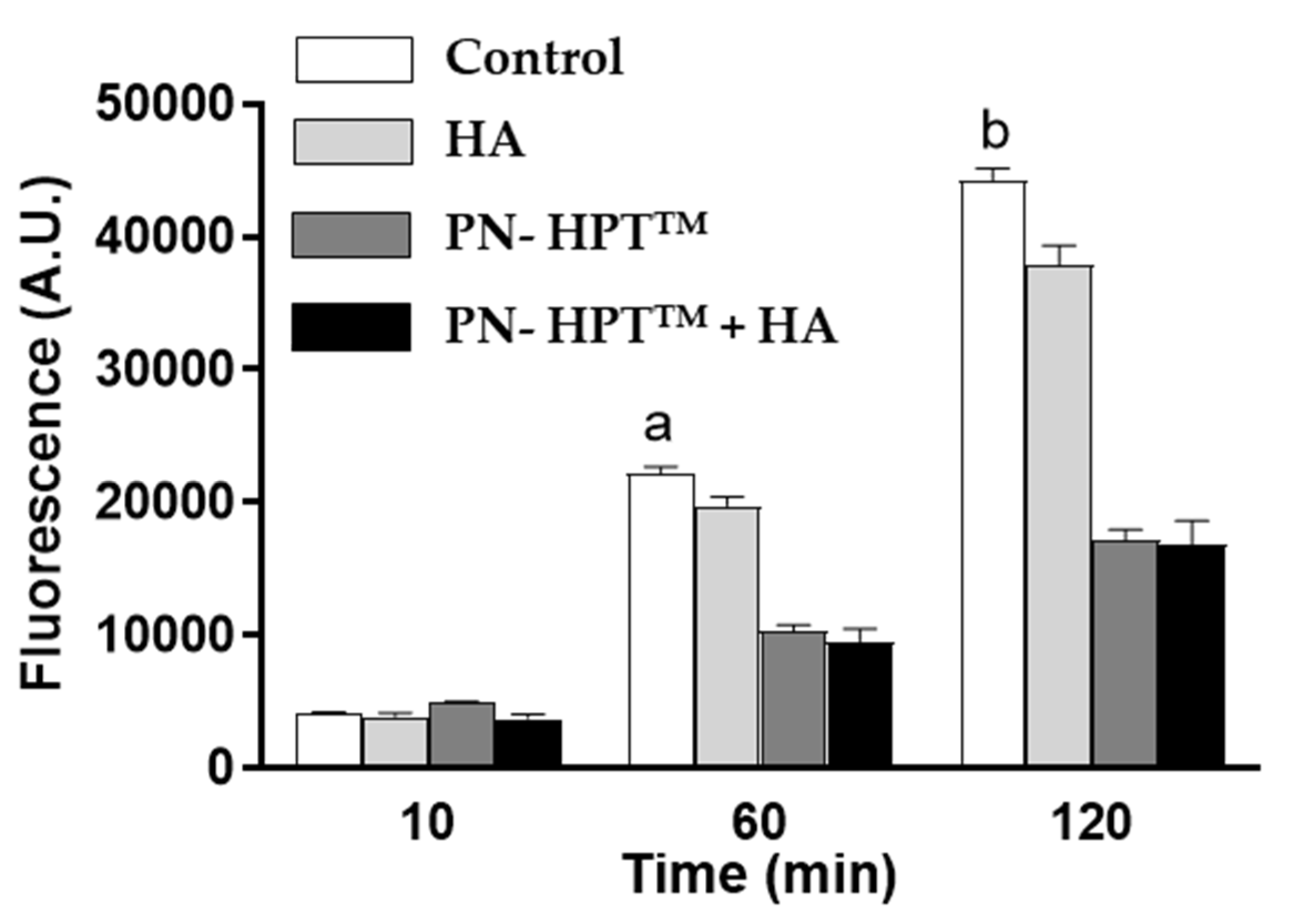

Figure 2 illustrates fluorescence levels at the highest compound concentrations at 10, 60, and 120 minutes post-H₂O₂ exposure, highlighting the superior scavenging efficacy of PN-HPT

TM and PN- HPT

TM + HA products over HA alone based products.

The significant reductions in fluorescence intensity observed for PN- HPTTM and PN- HPTTM +HA products reflect their capacity to neutralize reactive oxygen species. The superior performance of the PN- HPTTM +HA combination across different concentrations suggests a synergistic effect, potentially arising from the complementary mechanisms of PN- HPTTM and HA. Taken together, these combined properties of PN-HPTTM and HA produce a more potent antioxidant effect than either component alone.

The implications of these findings are significant, given the central role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of numerous conditions, including aging [

4,

56,

57,

58] , periodontitis [

59,

60], and osteoarthrosis [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. This study demonstrates antioxidant activity of PN-HPT

TM and PN-HPT

TM + HA products, positioning them as promising candidates for therapeutic applications aimed at locally reducing oxidative damage. Their robust activity against ROS could also partially explain the favourable clinical outcomes observed with PN-HPT

TM -containing products across diverse clinical contexts, including dermatology, wound healing, gynecology, osteoarthrosis, dentistry and aesthetic medicine [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

66,

67,

68,

69].

Nevertheless, our approach has limitations. While the cell-free system effectively isolates scavenging activity, it does not recapitulate the complexity of living tissues, where factors like enzymatic activity, local pH, and cellular signaling may influence ROS levels. Further in vitro and in vivo experiments are needed to clarify how PN- HPTTM and PN- HPTTM +HA functions within the physiological milieu, how quickly it is metabolized or replaced, and whether its protective effects extend to diverse cell types and tissues. Investigating the molecular details of how PN- HPTTM and HA interact—both with each other and with endogenous antioxidant systems—will yield deeper insights into optimizing their use against oxidative stress.

3. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the significant antioxidant properties of Polynucleotides High Purification Technology (PN- HPTTM), Hyaluronic Acid (HA), and their combination (PN- HPTTM +HA) in a cell-free model of oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. The findings indicate that PN- HPTTM and PN- HPTTM +HA effectively reduce ROS activity in a dose- and time-dependent manner, with PN- HPTTM +HA showing the most pronounced scavenger effect.

The synergistic activity observed in the PN- HPTTM +HA combination underscores its potential as a powerful therapeutic tool for mitigating oxidative damage. These results suggest promising applications in medical and aesthetic fields, particularly in contexts such as tissue repair, wound healing, osteoarthrosis and anti-aging therapies.

Further research is needed to validate these findings in more complex biological systems and to explore the mechanisms underlying their antioxidant effects. The insights provided by this study form a solid foundation for advancing the development of PN- HPTTM and PN- HPTTM +HA as innovative solutions to oxidative stress-related challenges.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Polynucleotides High Purification Technology (PN- HPTTM)

Polynucleotides High Purification Technology (PN- HPT

TM) used in this study were obtained from Mastelli S.r.l. (Sanremo, Italy). PN- HPT

TM is a compound containing DNA fragments of varying chain lengths, extracted from the gonads of salmon trout (

Oncorhynchus mykiss) through an original high-purification technology (HPT™). This technology provides high-quality DNA while minimizing immunological side effects [

34]. The products employed in the present study are commercially available Class III medical devices: PN- HPT

TM (20 mg/mL), hyaluronic acid (HA) (20 mg/mL), and a combination of PN- HPT

TM and HA (PN- HPT

TM +HA) containing 10 mg/mL PN- HPT

TM and 10 mg/mL HA.

4.2. Oxidative Stress Assay

The scavenger activity of PN-HPTTM, HA, and PN-HPTTM +HA products was evaluated using a cell-free fluorimetric assay with Calcein-AM fluorescence as a marker for oxidative stress. Stock solutions of PN-HPT™, HA, and PN-HPT™ + HA were tested at the commercially available concentration (undiluted, indicated as “Max” in the figures) and at 900, 600, and 300 μg/ml, obtained by dilution in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).The samples were then aliquoted into a 96-well black microplate (Thermo-Fisher), with 100 μl added to each well. PBS alone was used as control.

To initiate the assay, 2 μM Calcein-AM (Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes to allow for fluorescence development. Following this, 600 μM H₂O₂ was introduced to induce oxidative stress. Fluorescence signals were measured at an emission wavelength of 530 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite F200 TECAN, Switzerland) at time intervals of 10, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes. This experimental setup allowed for the assessment of the scavenger effects of the treatments over time.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Fluorescence data were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were assessed using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test to compare treated samples against the control, using Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the entire procedure was repeated three times to ensure reproducibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G. and S.G.; methodology, S.B. and M.T.C.; formal analysis, S.B. and M.T.C.; resources, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G.; visualization, C.G. and M.T.C.; supervision, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Mastelli s.r.l., Sanremo Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Scavenging activity of Polynucleotides High Purification Technology (PN- HPT

TM), Hyaluronic acid (HA), or Polynucleotides HPT

TM + Hyaluronic Acid (PN- HPT

TM +HA) compounds in response to H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress. Results of the Bonferroni post-test for the experiment in

Figure 1 are presented below.

PN- HPTTM:

30’: a p=0.002 Control vs Max concentration

60’: b p=0.0004 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.01 Control vs 900 μg/ml

90’: c p=0.0002 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.005 Control vs 900 μg/ml

120’: d p<0.001 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.004 Control vs 900 μg/ml.

HA

90’: a p=0.05 Control vs 600 μg/ml.

120’: b p=0.04 Control vs 600 μg/ml.

PN- HPTTM +HA

30’: a p=0.01 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.02 Control vs 900 μg/ml.

60’: b p=0.004 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.006 Control vs 900 μg/ml, p= 0.02 Control vs 600 μg/ml.

90’: c p=0.004 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.002 Control vs 900 μg/ml and Control vs 600 μg/ml.

120’: d p=0.004 Control vs Max concentration, p=0.001 Control vs 900 μg/ml, p=0.01 Control vs 600 μg/ml.

References

- Sies H, Belousov V V., Chandel NS, et al (2022) Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23:499–515. [CrossRef]

- Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ (2014) Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS Release. Physiol Rev 94:909–950. [CrossRef]

- Sies H (2017) Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: Oxidative eustress. Redox Biol 11:613–619. [CrossRef]

- Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, et al (2023) Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol 97:2499–2574.

- Bateman JF, Boot-Handford RP, Lamandé SR (2009) Genetic diseases of connective tissues: Cellular and extracellular effects of ECM mutations. Nat Rev Genet 10:173–183.

- Jones MJ, Jones MC (2024) Cell cycle control by cell-matrix interactions. Curr Opin Cell Biol 86:102288. [CrossRef]

- Novoseletskaya ES, Evdokimov PV, Efimenko AY (2023) Extracellular matrix-induced signaling pathways in mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Cell Communication and Signaling 21:244. [CrossRef]

- Richter K, Kietzmann T (2016) Reactive oxygen species and fibrosis: further evidence of a significant liaison. Cell Tissue Res 365:591–605.

- Martins SG, Zilhão R, Thorsteinsdóttir S, Carlos AR (2021) Linking Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage to Changes in the Expression of Extracellular Matrix Components. Front Genet 12:. [CrossRef]

- Tu Y, Quan T (2016) Oxidative Stress and Human Skin Connective Tissue Aging. Cosmetics 3:28. [CrossRef]

- Lin X, Moreno IY, Nguyen L, et al (2023) ROS-Mediated Fragmentation Alters the Effects of Hyaluronan on Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing. Biomolecules 13:1385. [CrossRef]

- Kennett EC, Chuang CY, Degendorfer G, et al (2011) Mechanisms and consequences of oxidative damage to extracellular matrix. Biochem Soc Trans 39:1279–1287. [CrossRef]

- Diller RB, Tabor AJ (2022) The Role of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) in Wound Healing: A Review. Biomimetics 7:87. [CrossRef]

- Marangio A, Biccari A, D’Angelo E, et al (2022) The Study of the Extracellular Matrix in Chronic Inflammation: A Way to Prevent Cancer Initiation? Cancers (Basel) 14:5903. [CrossRef]

- Moseley R, Waddington RJ (2021) Modification of gingival proteoglycans by reactive oxygen species: potential mechanism of proteoglycan degradation during periodontal diseases. Free Radic Res 55:970–981. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Wang L, Kang Y, et al (2023) Nanomaterial-based reactive oxygen species scavengers for osteoarthritis therapy. Acta Biomater 162:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Wang RM, Mesfin JM, Hunter J, et al (2022) Myocardial matrix hydrogel acts as a reactive oxygen species scavenger and supports a proliferative microenvironment for cardiomyocytes. Acta Biomater 152:47–59. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Xia X, Liu J, et al (2024) Cartilage-inspired self-assembly glycopeptide hydrogels for cartilage regeneration via ROS scavenging. Bioact Mater 32:319–332. [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Wang Q, Li T, et al (2024) ECM-mimetic glucomannan hydrogel promotes pressure ulcer healing by scavenging ROS, promoting angiogenesis and regulating macrophages. Int J Biol Macromol 280:135776. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueni G, Scalzone A, Licini C, et al (2021) Insights into oxidative stress in bone tissue and novel challenges for biomaterials. Materials Science and Engineering: C 130:112433. [CrossRef]

- Buzoglu HD, Burus A, Bayazıt Y, Goldberg M (2023) Stem Cell and Oxidative Stress-Inflammation Cycle. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 18:641–652. [CrossRef]

- Patel KD, Keskin-Erdogan Z, Sawadkar P, et al (2024) Oxidative stress modulating nanomaterials and their biochemical roles in nanomedicine. Nanoscale Horiz 9:1630–1682. [CrossRef]

- Echeverria Molina MI, Malollari KG, Komvopoulos K (2021) Design Challenges in Polymeric Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9:. [CrossRef]

- Suamte L, Tirkey A, Barman J, Jayasekhar Babu P (2023) Various manufacturing methods and ideal properties of scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Smart Materials in Manufacturing 1:100011. [CrossRef]

- Fan F, Saha S, Hanjaya-Putra D (2021) Biomimetic hydrogels to promote wound healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9:718377.

- Xu F, Dawson C, Lamb M, et al (2022) Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering: Addressing Key Design Needs Toward Clinical Translation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10:. [CrossRef]

- Radulescu D-M, Neacsu IA, Grumezescu A-M, Andronescu E (2022) New Insights of Scaffolds Based on Hydrogels in Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 14:799. [CrossRef]

- Khan MUA, Stojanović GM, Abdullah MF Bin, et al (2024) Fundamental properties of smart hydrogels for tissue engineering applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 254:127882. [CrossRef]

- Guan X, Avci-Adali M, Alarçin E, et al (2017) Development of hydrogels for regenerative engineering. Biotechnol J 12:1600394. [CrossRef]

- Ho T-C, Chang C-C, Chan H-P, et al (2022) Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 27:2902. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Yang L, Liu K, Gao F (2023) Hydrogel scaffolds in bone regeneration: Their promising roles in angiogenesis. Front Pharmacol 14:. [CrossRef]

- Stepanovska J, Supova M, Hanzalek K, et al (2021) Collagen Bioinks for Bioprinting: A Systematic Review of Hydrogel Properties, Bioprinting Parameters, Protocols, and Bioprinted Structure Characteristics. Biomedicines 9:1137. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed NS, Kamel S (2022) Polysaccharides-Based Injectable Hydrogels: Preparation, Characteristics, and Biomedical Applications. Colloids and Interfaces 6:78. [CrossRef]

- Colangelo MT, Guizzardi S, Laschera L, et al (2025) The effects of Polynucleotides-based biomimetic hydrogels in tissue repair: a 2D and 3D in vitro study. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Ye S, Wei B, Zeng L (2022) Advances on Hydrogels for Oral Science Research. Gels 8.

- Colangelo MT, Govoni P, Belletti S, et al (2021) Polynucleotide biogel enhances tissue repair, matrix deposition and organization. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 35:355–362. [CrossRef]

- Maioli L (2020) Polynucleotides Highly Purified Technology and nucleotides for the acceleration and regulation of normal wound healing. Aesthetic Medicine 6:.

- Collins MN, Birkinshaw C (2013) Hyaluronic acid based scaffolds for tissue engineering—A review. Carbohydr Polym 92:1262–1279. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Deng Z, Guo Y, Xu P (2022) Designing functional hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Mater Today Bio 17:100495. [CrossRef]

- Hwang HS, Lee C-S (2023) Recent Progress in Hyaluronic-Acid-Based Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering. Gels 9:588. [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar K, Park S, Santosh SS, et al (2022) Application of hyaluronic acid in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and nanomedicine: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 222:2744–2760. [CrossRef]

- Colangelo MT, Belletti S, Govoni P, et al (2021) A Biomimetic Polynucleotides–Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Promotes Wound Healing in a Primary Gingival Fibroblast Model. Applied Sciences 11:4405. [CrossRef]

- Colangelo MT, Vicedomini ML, Belletti S, et al (2023) A Biomimetic Polynucleotides–Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Promotes the Growth of 3D Spheroid Cultures of Gingival Fibroblasts. Applied Sciences 13:743.

- Guizzardi S, Uggeri J, Belletti S, Cattarini G (2013) Hyaluronate Increases Polynucleotides Effect on Human Cultured Fibroblasts. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications 03:124–128. [CrossRef]

- De Caridi G, Massara M, Acri I, et al (2016) Trophic effects of polynucleotides and hyaluronic acid in the healing of venous ulcers of the lower limbs: a clinical study. Int Wound J 13:754–758. [CrossRef]

- Segreto F, Carotti S, Marangi GF, et al (2020) The use of acellular porcine dermis, hyaluronic acid and polynucleotides in the treatment of cutaneous ulcers: Single blind randomised clinical trial. Int Wound J 17:1702–1708. [CrossRef]

- Saggini R, Di Stefano A, Capogrosso F, et al (2014) Viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid or polynucleotides: Results and hypothesis for condro-synchronization. J Clin Trials 4:2167–2870.

- Migliore A, Graziano E, Martín LSM, et al (2021) Three-year management of hip osteoarthritis with intra-articular polynucleotides: a real-life cohort retrospective study. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 35:1189–1194.

- Cavallini M, Bartoletti E, Maioli L, et al (2024) Value and Benefits of the Polynucleotides HPTTM Dermal Priming Paradigm: A Consensus on Practice Guidance for Aesthetic Medicine Practitioners and Future Research. Clinical & Experimental Dermatology and Therapies 9:224.

- Cenzato N, Crispino R, Russillo A, et al (2024) Clinical effectiveness of polynucleotide TMJ injection compared with physiotherapy: a 3-month randomised clinical trial. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 62:807–812.

- Guelfi M, Fabbrini R, Guelfi MG (2020) Intra-articular treatment of knee and ankle osteoarthritis with polynucleotides: prospective case record cohort vs historical controls. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 34:1949–1953.

- Dallari D, Sabbioni G, Del Piccolo N, et al (2020) Efficacy of intra-articular polynucleotides associated with hyaluronic acid versus hyaluronic acid alone in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 30:1–7.

- Reddy VP (2023) Oxidative Stress in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 11:2925. [CrossRef]

- Uggeri J, Gatti R, Belletti S, et al (2000) Calcein-AM is a detector of intracellular oxidative activity. Histochem Cell Biol 122:499–505. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Shi R, Lu W, et al (2024) Framework nucleic acids as promising reactive oxygen species scavengers for anti-inflammatory therapy. Nanoscale 16:7363–7377. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado E, Morales-Pison S, Urbina F, Solari A (2023) Aging Hallmarks and the Role of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 12:651. [CrossRef]

- Hajam YA, Rani R, Ganie SY, et al (2022) Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells 11:552. [CrossRef]

- Papaccio F, D′Arino A, Caputo S, Bellei B (2022) Focus on the Contribution of Oxidative Stress in Skin Aging. Antioxidants 11:1121. [CrossRef]

- Sczepanik FSC, Grossi ML, Casati M, et al (2020) Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of oxidative stress: We should treat it that way. Periodontol 2000 84:45–68. [CrossRef]

- Shang J, Liu H, Zheng Y, Zhang Z (2023) Role of oxidative stress in the relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases. Front Physiol 14:. [CrossRef]

- Matyushkin AI, Ivanova EA, Voronina TA (2022) New Directions in the Development of Pharmacotherapy for Osteoarthrosis Based on Modern Concepts of the Disease Pathogenesis (A Review). Pharm Chem J 55:1282–1287. [CrossRef]

- Arra M, Abu-Amer Y (2023) Cross-talk of inflammation and chondrocyte intracellular metabolism in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 31:1012–1021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Xu J, Si H, et al (2022) The Role Played by Ferroptosis in Osteoarthritis: Evidence Based on Iron Dyshomeostasis and Lipid Peroxidation. Antioxidants 11:1668. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Hou L, Guo Z, et al (2023) Lipid peroxidation in osteoarthritis: focusing on 4-hydroxynonenal, malondialdehyde, and ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov 9:320. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Luo P, Yang M, et al (2022) The role of oxidative stress in the development of knee osteoarthritis: A comprehensive research review. Front Mol Biosci 9:. [CrossRef]

- Pia Palmieri I, Raichi M (2019) Biorevitalization of postmenopausal labia majora, the polynucleotide/hyaluronic acid option. Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports 3:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Vanelli R, Costa P, Rossi SMP, Benazzo F (2010) Efficacy of intra-articular polynucleotides in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 18:901–907. [CrossRef]

- Stagni C, Rocchi M, Mazzotta A, et al (2021) Randomised, double-blind comparison of a fixed co-formulation of intra-articular polynucleotides and hyaluronic acid versus hyaluronic acid alone in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: Two-year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22:1–12.

- Cairo F, Cavalcanti R, Barbato L, et al (2024) Polynucleotides and Hyaluronic Acid (PN-HA) Mixture With or Without Deproteinized Bovine Bone Mineral as a Novel Approach for the Treatment of Deep Infra-Bony Defects: A Retrospective Case-Series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1–24. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).