1. Introduction

Climate change fundamentally alters rice grain quality through interconnected physiological and biochemical mechanisms that operate throughout grain development. These abiotic stress affects source-sink relationships at first, inhibiting photosynthesis in the vegetative canopy, leading to limited biomass accumulation, and in addition limit sucrose transport into developing grains and thus restricting the grain development and maturation [

1]. Rising temperatures modify enzyme kinetics in starch biosynthesis pathways, altering amylose to amylopectin ratios, gelatinisation properties, and protein accumulation patterns. As a result, percent protein content increases and percent amylose decreases under global warming conditions [

2]. Concurrently, drought stress disrupts assimilate translocation and grain filling processes, while elevated CO₂ alters carbon:nitrogen balance in developing grains. These biochemical modifications manifest as quantifiable differences in starch granules with irregular shapes and altered protein bodies, resulting to the increase in air spaces within the endosperm triggering chalk. These global changes in temperature also affect head rice yield due to reduced grain filling duration, increase in chaffy grain with partial grain filling. These biochemical alterations disturb milling quality, appearance attributes, cooking behaviour, and nutritional composition—parameters that directly determine market value and consumer acceptance [

2,

3,

4].

Temperate rice refers to

japonica-type rice varieties that are specifically adapted to grow in cooler climates with distinct seasonal temperature variations. These varieties are typically cultivated in regions such as East Asia, Europe, Australia, and North America [

5,

6]. Temperate rice cultivation, primarily of

japonica varieties, presents distinct research challenges compared to tropical rice production systems. Characterised by cooler climates, shorter growing seasons, longer day lengths, and specific environmental vulnerabilities, temperate regions face unique climate change impacts [

6,

7,

8]. Due to recent climate change, the night temperature has increased rapidly in comparison to high day temperatures and thus high night temperatures are impacting the temperate countries too [

9]. These temperate regions increasingly experience extreme temperature variability ranging between cold stress at early plant establishment to high day and high night temperature during reproductive stages, altered precipitation regimes resulting in water scarcity—all directly influencing grain development and quality [

10].

The Australian rice industry, primarily located in the southern Murray-Darling Basin (approximately 34°S to 36°S) in New South Wales, exemplifies the complexities of temperate rice production under changing climatic conditions. Despite fluctuations in production influenced by water availability and competing land use pressures, this industry has developed significant adaptive capacity through genetic improvement of varieties and optimised agronomic practices [

11]. However, maintaining good grain quality under increasingly variable climate conditions presents ongoing challenges requiring systematic evaluation of adaptation pathways.

Climate change creates a fundamental challenge for temperate rice production systems: maintaining grain quality characteristics valued by consumers and markets while adapting to increasingly variable environmental conditions. This review demonstrates that climate factors affect grain quality through specific biochemical pathways that modify starch structure, protein accumulation, and aroma compound synthesis during grain development. These modifications manifest differently across rice quality classes, with medium-grain japonica varieties showing vulnerability to heat-induced amylose reduction, aromatic varieties experiencing modified fragrance compound synthesis under drought, and long-grain types demonstrating compromised kernel integrity under combined stressors.

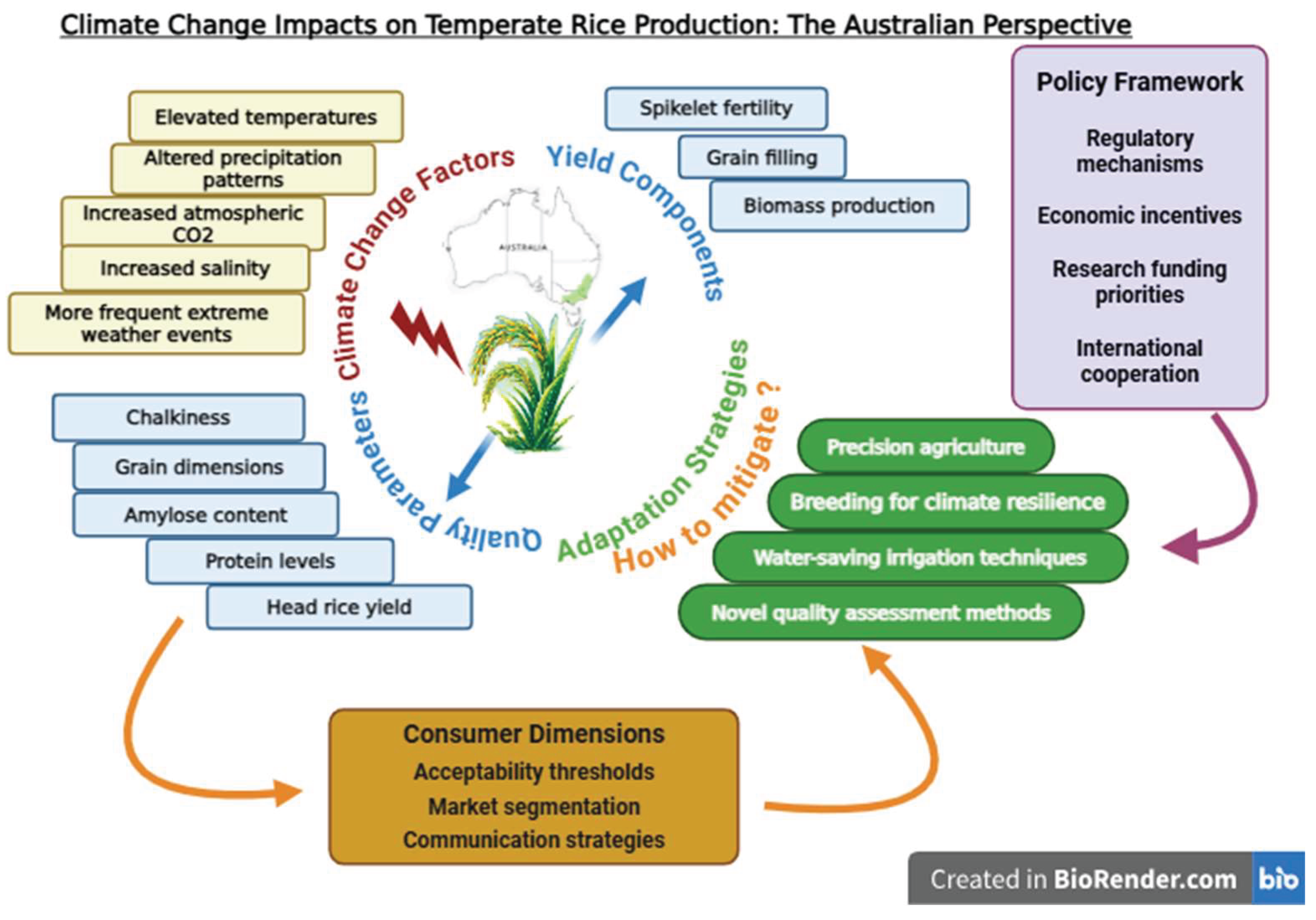

The adaptation pathways identified in this review, spanning genetic, agronomic, technological, and assessment domains, demonstrate that maintaining quality under climate change requires integrated approaches rather than isolated interventions (

Figure 1). Breeding programmes must target quality-specific biochemical pathways showing climate sensitivity, while water management innovations require calibration to variety-specific responses. Technological systems enhance adaptation effectiveness through improved monitoring and precision management, whilst advanced assessment methodologies accelerate the adaptation feedback cycle by providing earlier and more comprehensive quality evaluation.

Effective climate adaptation extends beyond technical approaches to encompass policy frameworks and consumer engagement strategies. Regulatory mechanisms governing water allocation, economic incentives rewarding quality maintenance, and research funding priorities all significantly influence adaptation capacity. Current policy structures often emphasise yield and production volume over grain quality and nutrition, creating potential misalignment with market positioning in premium segments. International cooperation mechanisms facilitating knowledge exchange and germplasm sharing represent underutilised policy approaches for enhancing adaptation efficiency across temperate production regions.

This review addresses three critical knowledge gaps in understanding climate change impacts on temperate rice grain quality:

How do temperature extremes, altered precipitation patterns, and elevated atmospheric CO₂ specifically affect grain quality parameters in temperate japonica varieties compared to tropical indica varieties?

What differences exist in climate vulnerability across quality classes (medium grain, short grain, aromatic varieties) within temperate production systems?

Which adaptation strategies demonstrate evidence-based effectiveness for maintaining grain quality under projected climate scenarios in temperate regions?

By integrating analysis of mechanistic relationships between environmental factors and grain quality parameters, differential vulnerability across rice quality classes, and adaptation strategy effectiveness, this review provides direction for research priorities to secure high-quality rice production in temperate production zones. This review is particularly timely given the increasing global demand for high-quality rice and the pressing need for climate-resilient agricultural systems.

2. Overview of the Australian Rice Industry

The Australian rice industry has evolved through distinct developmental phases that have progressively enhanced its adaptive capacity to environmental constraints—creating institutional structures, knowledge systems, and technological approaches now central to its climate change response capabilities. This historical evolution provides critical context for understanding contemporary adaptation challenges and opportunities.

2.1. Historical Development and Adaptive Evolution

The industry

’s formative period (1850s-1920s) established fundamental geographical and genetic foundations while addressing the challenges of temperate rice cultivation in the Australian environment. Initial cultivation attempts by Chinese prospectors in the 1850s proved not commercially viable due to inadequate understanding of local agroclimatic conditions. The first documented successful cultivation occurred in Northern Queensland during the 1860s, though even these operations faced constraints from soil toxicities and pest pressures [

12,

13,

14]. This early period demonstrated the significant climate and environmental barriers requiring adaptation for sustainable production.

The industry’s infrastructural foundation emerged with the establishment of the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area in the early 20th century. Government policy and infrastructure development, particularly the construction of the Burrinjuck Dam, created the hydrological conditions necessary for reliable temperate rice production [

13,

14,

15]. This confluence of infrastructure development and genetic adaptation established the geographical concentration and varietal orientation that continues to cater the need of the Australian rice industry.

The industry’s institutional foundation developed with the formation of Ricegrowers’ Co-operative Mills Limited in 1955. This cooperative structure, created in response to concerns regarding price transmission to producers, established frameworks for coordinated industry response to production challenges. The launch of the ‘Sunwhite’ rice brand emphasised quality differentiation as a core strategic approach, establishing the quality focus that remains central to industry identity and market positioning [

13,

14,

16].

The modern adaptation phase (post-1970s) has featured increasing engagement with environmental constraints, particularly water limitations. The development of varieties with shorter growing cycles (e.g., ‘Quest’) and enhanced cold tolerance (e.g., ‘Sherpa’) exemplifies the industry’s genetic adaptation to resource constraints and temperature vulnerabilities. This period has also seen significant technological adoption, establishing Australia’s rice production systems as the world’s most water-efficient practices [

13,

17].

This historical development trajectory has created three critical adaptive capacity elements that influence contemporary climate response:

Institutional knowledge systems that facilitate information transfer and coordinated adaptation

Genetic adaptation capacity through established breeding programmes targeting environmental constraints

Technological innovation systems that systematically address resource limitations

These adaptive capacity elements provided the foundation for contemporary climate adaptation strategies while shaping the industry’s approach to emerging challenges.

The New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (NSW-DPI), established in 1928, oversees agriculture, while the Yanco Agricultural Institute (YAI), in collaboration with NSW-DPI, leads rice research in the Murray and Murrumbidgee Irrigation Areas. YAI’s rice improvement program, which began in 1959, received additional investment and support in 1979, enabling further progress in varietal improvement and grain quality [

15].

For decades, the NSW DPI led Australian rice breeding and established the benchmark for grain quality assessment through its dedicated facilities and protocols at the YAI. In 2022, driven by strategic goals for improved water productivity, accelerated genetic gain, and enhanced commercial focus, these responsibilities transitioned to Rice Breeding Australia (RBA), a new entity formed by AgriFutures Australia, SunRice, and the Ricegrowers

’ Association of Australia. This shift signifies a move away from YAI as the custodian of quality standards, with RBA adopting faster assessment methods and technologies at critical points in its accelerated breeding cycle and prioritising quality traits based on direct commercial imperatives [

18].

2.2. Contemporary Production Systems and Market Position

The modern Australian rice industry occupies a distinctive market niche characterised by high-quality temperate japonica production within a highly variable production environment. Production exhibits substantial interannual fluctuations primarily driven by water availability, exemplified by the contrast between 2019-20 (approximately 57,000 tonnes) and 2020-21 (423,000 tonnes) despite yield reductions from cooler temperatures [

19]. This production volatility creates significant challenges for industry planning and climate adaptation investments.

The industry operates within a complex agricultural landscape where crop rotation practices (integrating rice with wheat, barley, canola, or livestock) provide agronomic benefits while introducing economic complexities that influence adaptation decisions. Increasing competition from alternative crops, particularly cotton and high-value horticultural production like almonds and walnuts, further complicates rice adaptation planning by altering the economic calculations for water allocation and infrastructure development [

11].

Water policy interventions create additional complexity for climate adaptation efforts. Recovery policies in the Murray-Darling Basin, implemented to address broader environmental sustainability concerns, have constrained water availability for rice cultivation, particularly during drier periods [

20]. This creates a policy environment where climate adaptation efforts must address both direct climate impacts and policy-mediated effects on resource availability.

Despite production volatility, domestic rice consumption has demonstrated consistent growth over the past three decades, driven substantially by immigration from rice-consuming countries [

21]. This demographic shift has diversified quality demands, complicating the definition of quality priorities for breeding and adaptation efforts. The industry maintains significant export orientation of short to medium grain Japonica type, with 2022-2023 export values of AU

$394 million against imports of long-grain Basmati and Jasmine quality type accounting AU

$312 million, indicating both strong domestic demand for imported varieties and important international markets for Australian production [

19].

Market projections suggest moderate growth, with market size expected to reach US

$ 172 million in 2024 and maintain a 1.4% annual growth rate through 2028 [

22]. However, these projections incorporate significant uncertainty regarding climate change impacts on production capacity, quality parameters, and international competitiveness. The industry

’s ability to maintain quality attributes under changing climate conditions will directly influence its position in premium market segments.

2.3. Climate Vulnerability and Adaptation Capacity

The contemporary Australian rice industry demonstrates specific climate vulnerabilities and adaptation capacities that will determine its sustainability under projected climate scenarios. Key vulnerabilities include:

Water dependency in a region experiencing increasing precipitation variability and competing water demands

Temperature sensitivity during critical reproductive and grain filling stages

Geographical concentration creating systemic vulnerability to localised climate impacts

Quality differentiation strategy requiring maintenance of specific parameters under changing conditions

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including prolonged droughts and floods, raising temperatures overlapping with grain set and filling presents adaptation challenges that exceed historical experience. The devastating 2019-2020 bushfires exemplify these impacts—while major agricultural areas avoided direct fire damage, associated drought conditions severely reduced crop yields, with irrigation storages depleted to critically low levels [

23].

This profile of specific vulnerabilities and adaptation capacities creates a complex adaptation landscape requiring integrated approaches spanning genetic, agronomic, technological, and institutional domains. The industry’s historical experience with environmental constraints provides valuable adaptation foundations, though projected climate change rates may exceed historical adaptive capacity without accelerated innovation.

To counterbalance these vulnerabilities, the Australian rice industry needs to adapt holistic approaches which includes significant adaptation capacities including:

Established breeding programmes focused on environmental stress tolerance

Advanced water management systems with demonstrated efficiency improvements

Technological innovation capacity supporting precision agriculture approaches

Institutional knowledge systems facilitating information transfer and coordinated response with strengthened value chain

3. Global Temperate Rice-Growing Regions and Rice Grain Quality Classes

Temperate rice breeding programmes worldwide have developed region-specific strategies to maintain and enhance quality segmentation, responding to the complex interplay between consumer preferences, environmental constraints, and market demands. These strategies have produced benchmark varieties that define the quality standards for temperate

japonica rice across diverse production regions (

Table 1). These benchmark varieties serve multiple critical functions: they establish reference points for quality assessment, create targets for breeding programmes, and provide genetic resources for climate adaptation efforts. The establishment of these quality benchmarks reflects each region’s distinct culinary traditions, consumer preferences, and environmental conditions, creating a complex matrix of quality parameters that must be maintained under changing climate conditions.

In temperate East Asia, varieties such as Koshihikari (Japan) and Dongjinbyeo (Korea) define quality standards emphasising soft texture, low amylose content, and glossy appearance [

24,

25]. These quality characteristics reflect deep cultural preferences and showcase the profound influence of consumer demand on breeding objectives in these regions. The primacy of texture and appearance in East Asian quality assessment frameworks has significant implications for climate adaptation efforts, as these parameters demonstrate sensitivity to temperature fluctuations during grain development [

26,

27].

European temperate rice production, centred in Mediterranean countries including Italy, Spain, and France, has established distinct quality profiles oriented toward culinary applications like risotto. Benchmark varieties such as Arborio and Carnaroli in Italy as well as Bomba and Bahia in Spain define quality standards characterised by specific textural properties and cooking behaviour [

28,

29]. These varieties exhibit higher amylopectin content that produces the creamy texture essential for traditional European rice dishes, creating specific vulnerability to climate factors that affect starch composition and structure.

The California rice industry thrives in the temperate climate of the Sacramento Valley, where hot days and cool nights create ideal conditions for growing high-quality japonica rice. More than 85% of all California rice is a Calrose, a medium-grain variety prized for its soft, sticky texture and recognised both nationally and internationally. About 10% of rice grown in California consists of short grain varieties (Koshihikari and Akitakomachi). These varieties are valued for their ideal texture and cooking properties, particularly in sushi and other Asian cuisines.

Temperate rice production extends to regions not traditionally associated with rice cultivation, including Eastern Europe, Russia, and temperate regions of South America. In these areas, benchmark varieties emphasise adaptation to local environmental conditions alongside quality parameters, representing a different balance between environmental resilience and quality maintenance. This diversity in quality benchmarks across temperate regions creates both challenges and opportunities for climate adaptation, as it provides genetic resources with varied adaptive capacities while requiring maintenance of diverse quality profiles under variable climatic conditions.

3.1. Quality Class Differentiation and Climate Vulnerability

Temperate rice-growing regions cultivate a diverse range of rice quality classes, each presenting distinct climate vulnerabilities related to their biochemical composition, genetic background, and quality parameters. Medium-grain

japonica varieties constitute the dominant quality class in many temperate regions, valued for their soft, slightly sticky texture resulting from specific amylose:amylopectin ratios and protein profiles. These varieties serve as the foundation for dishes ranging from steamed rice to rice-based desserts, with their multi-purpose culinary applications creating significant economic and cultural importance [

30,

31,

32]. Their quality profile demonstrates specific vulnerabilities to temperature fluctuations during grain filling, which can alter starch structure and composition with consequent effects on cooking behavior and textural properties.

Short-grain rice varieties, including those used for sushi production, share fundamental characteristics with medium-grain types but exhibit even stickier texture due to low amylose preferences with specific starch structural properties. Koshihikari represents the definitive benchmark for this quality class, with its soft characteristic texture, glossy endosperm, and minimal chalkiness establishing quality standards across major temperate rice-growing countries [

33]. The exacting quality requirements for these varieties create climate vulnerabilities, as the biochemical pathways governing starch biosynthesis demonstrate sensitivity to temperature fluctuations and water stress during critical developmental periods. Elevated night temperatures shown to substantially increase percent chalk and reduce head rice yield and as well affect starch metabolism by triggering alpha amylases [

1,

34].

While traditionally associated with tropical climates, jasmine rice is increasingly cultivated in some temperate regions where aromatic rice demand exists. Premium indica varieties classified under the jasmine rice quality class, such as Khao Dawk Mali 105 (KDML105), serve niche markets with distinct preferences for fragrant aromas and soft texture [

35,

36]. These aromatic varieties exhibit specific climate vulnerabilities related to the biosynthetic pathways governing aroma compound production, which demonstrate sensitivity to temperature and water availability during grain development.

Italian rice production represents a specialised segment within temperate

japonica cultivation, with varieties such as Arborio developed for specific culinary applications. Many Italian varieties possess protected geographical indications (PGI), establishing strict quality standards linked to specific production regions [

28]. This geographical specialisation creates complex climate vulnerabilities where changes in local environmental conditions can affect the capacity to maintain quality parameters essential for PGI designation, potentially undermining economic value and market position.

Non-fragrant long-grain rice varieties grown in temperate regions serve consumers preferring drier, separate-grained texture resulting from higher amylose content and specific protein characteristics. These varieties demonstrate different climate vulnerabilities compared to medium-grain types, particularly regarding temperature sensitivity during starch synthesis phases. Basmati rice, traditionally grown in subtropical regions of South Asia, presents an interesting case where genomic studies indicate closer genetic similarities with

japonica than with typical indica varieties despite its classification [

37,

38,

39]. This genomic complexity may influence its climate adaptation capacity and offers potential genetic resources for climate resilience breeding.

4. Impact of Climate Change and Fluctuating Environmental Conditions on Grain Quality

Climate change is fundamentally altering the environmental conditions under which rice is cultivated, with significant implications for both yield stability and grain quality parameters. In temperate regions, these environmental shifts pose challenges due to their specific effects on the biochemical and physiological processes governing quality traits in

japonica rice varieties. The combined influence of temperature extremes, altered precipitation patterns, elevated atmospheric CO₂, and increased salinity creates a complex matrix of interacting stressors that affect grain development and quality characteristics through multiple pathways. Beyond direct climatic influences, shifting pest and disease dynamics, soil deterioration, and changes in water resource availability further complicate rice production in temperate regions. Understanding these complex interactions is essential for predicting long-term impacts on

japonica rice quality and developing targeted adaptation strategies, including climate-resilient varieties and optimised agronomic practices [

40,

41,

42].

The interaction between grain quality parameters and climate factors in temperate rice production creates a complex adaptive challenge requiring integrated approaches spanning genetics, agronomy, and technological innovation. Temperature regimes during grain development exert particularly significant influences on quality formation, affecting enzymatic activities governing starch biosynthesis, protein accumulation, and aroma compound production. Cold temperature stress during critical reproductive stages represents a distinct challenge in temperate systems, with potential effects on grain filling, starch structure, and ultimately cooking quality [

7,

42,

43].

Consumer preferences regarding quality characteristics demonstrate substantial regional variation while exhibiting general resistance to change, creating adaptation challenges where climate impacts affect established quality parameters. This fixed consumer preference creates imperative for breeding and management approaches that maintain the consistency of quality under changing environmental conditions, rather than attempting to shift consumer expectations to accommodate climate-induced quality alterations. This consumer-driven constraint significantly shapes adaptation pathways and priorities across temperate production regions [

44].

The differentiation of quality classes across temperate regions provides potential genetic resources for climate adaptation while creating challenges related to maintaining distinct quality profiles under changing conditions. Understanding these quality-climate interactions requires integrated research approaches examining biochemical pathways, genetic regulation, environmental influences, and their combined effects on grain quality and nutrition. This understanding forms the foundation for developing targeted adaptation strategies that address specific vulnerabilities across quality classes while maintaining the distinct characteristics that define market segments and consumer preferences.

4.1. Cold Temperature Stress

Cold temperature stress represents a distinctive challenge in temperate rice production systems, particularly during critical reproductive and grain-filling stages. Australian research has extensively documented yield impacts from low-temperature stress [

7,

45,

46], though investigations specifically examining grain quality implications remain comparatively limited [

47,

48]. Low temperatures during key developmental phases can reduce rice yields by over 40%, with cold snaps during pollination proving particularly damaging by inducing spikelet sterility and disrupting fertilisation processes.

The development of cold-tolerant varieties like Sherpa demonstrates the Australian industry’s adaptive response to this challenge. This variety provides enhanced resilience by requiring less water to protect against low temperature while maintaining yield stability through critical growth stages [

49]. The physiological mechanisms underlying cold tolerance include improved pollen viability under low temperatures and enhanced capacity to maintain metabolic processes during stress periods. These adaptations extend to flowering and grain-filling phases, reducing cold-induced sterility and stabilising yield potential. Additionally, shorter growth cycles help ensure rice matures before potentially damaging cold weather events mostly in February that coincides with critical reproductive growth stages [

6,

50,

51].

Low temperatures during early developmental stages can indirectly affect grain quality by altering subsequent grain-filling processes [

52]. Research from southern China, experiencing more frequent low temperatures and reduced solar radiation during heading and grain-filling stages, demonstrates how these conditions negatively impact multiple quality parameters. The combination of low temperature and reduced light intensity increases chalkiness incidence and severity while reducing milling quality, which significantly impacts head rice yield. Additionally, these stress conditions alter starch viscosity properties, with the most pronounced effects occurring during the initial 21 days of grain filling [

53].

The Riverina region in southeastern Australia benefits from abundant solar radiation and typically cooler grain-filling periods that generally favour enhanced quality. However, when low temperatures during reproductive development coincide with other stressors, yield potential and quality parameters face compound threats [

54]. This regional experience highlights the importance of expanded research on rice grain quality responses to temperature fluctuations in Australian production systems, particularly during autumn when similar environmental conditions affect grain-filling processes.

4.2. High Temperature Stress

Anthropogenic climate change has significantly increased environmental temperatures in many regions, negatively affecting both crop productivity and grain quality parameters. High-temperature stress during grain development reduces grain filling duration and negatively impact grain quality, increases chalkiness incidence and severity, lowers head rice yield, and lowers grain weight in temperate rice varieties, directly affecting multiple quality attributes [

54]. Importantly, research distinguishes between high night temperature (HNT) effects and high day temperature impacts, with HNT demonstrating particularly significant influences on grain quality impairment.

HNT reduces final grain weight by slowing grain growth rates during early to mid-grain filling phases. These effects occur through multiple mechanisms, including decreased endosperm cell expansion, particularly affecting cells between the central and peripheral regions of the endosperm [

55]. The yield reductions associated with HNT stem from decreased biomass accumulation, reduced crop growth rates, and lower harvest indices. At the grain level, HNT negatively affects grain weight, grain filling duration, and spikelet fertility [

56].

The cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying HNT effects include activation of stress signalling pathways that can cause permanent cell membrane damage. These disruptions to cellular integrity manifest as reduced kernel quality and increased chalkiness, directly lowering market value [

57]. Research in southern China

’s double rice cropping system found that post-anthesis warming increased canopy temperatures without significantly affecting grain yield. However, this elevated temperature reduced milling and appearance quality while paradoxically improving eating and nutritional quality parameters, demonstrating the complex and sometimes contradictory effects of temperature on different quality attributes [

58].

In Australian production systems, timing cultivation to ensure vegetative growth during warmer temperatures and high solar radiation, while positioning grain filling during milder autumn temperatures, represents a key adaptive strategy for quality management [

59,

60]. Australian research examining heat stress during different developmental stages found significant yield losses when high temperatures coincided with panicle exertion and early grain filling, though genetic variation in tolerance was evident [

46]. Varieties including YRM 67, Koshihikari, and Opus demonstrated greater heat tolerance during these phases. During late grain filling, yield reductions appeared in specific varieties (Opus and YRM 67) while others remained relatively unaffected. Though genetic variation exists, no variety demonstrated consistent heat tolerance across all developmental stages, highlighting the need for broader germplasm screening and targeted breeding efforts [

46].

4.3. Altered Precipitation Patterns and Water Management Implications

Changes in precipitation patterns directly affect water availability for irrigation while creating secondary effects through humidity levels, disease pressure, and soil conditions. Research examining rice responses to different seasonal conditions found that grain yield and quality parameters, including head rice yield, chalkiness incidence, and gelatinisation temperature, responded differently to wet, cool, and hot seasonal conditions. These findings indicate that adaptation strategies must consider both yield stability and grain quality maintenance under increasingly variable climate conditions [

61].

Water management practices interact with temperature effects to influence quality development, creating complex vulnerabilities in temperate rice production systems. The Australian rice industry exemplifies this interaction, having developed sophisticated water management approaches that address both resource efficiency and quality maintenance objectives [

47,

59,

62,

63]. These management approaches must continually evolve to address changing climate conditions, particularly increasing temperature variability and altered precipitation patterns that affect both water availability and grain quality.

Direct-Seeded Rice (DSR) is increasingly recognised as a resource-conserving technology that reduces water use and labour input while enabling mechanisation and early crop establishment. When combined with Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) (section 6.2 in this review) irrigation, DSR enhances water use efficiency and water productivity, offering a sustainable pathway for rice production under limited resource availability [

64]. In addition to water savings, AWD with DSR has been shown to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions—particularly methane (CH₄) by 60–87%—and lower total arsenic concentrations in milled rice grain by up to 65%, without compromising grain yield or requiring increased nitrogen inputs. This reduction in grain arsenic levels represents a notable improvement in rice grain quality from a food safety perspective, reinforcing AWD’s role as a climate-smart and quality-conscious irrigation strategy in rice systems [

65].

Research from Charles Sturt University has demonstrated that water-saving irrigation practices like AWD and delayed permanent water (DPW) can maintain key quality parameters when properly managed. Wood et al. [

47] found that DPW with post-flower flush supplementation maintains milling quality when combined with appropriate nitrogen management (>60 kg/ha), though the effects vary by variety and quality class. Interestingly, some water stress during the vegetative growth phase can actually improve grain quality during subsequent grain-filling periods through physiological adaptations that enhance translocation efficiency [

66]. These findings highlight the complex interactions between water management strategies and grain quality formation.

Further, deploying drought-tolerant and water-efficient rice varieties can help mitigate the impacts of altered precipitation patterns. These varieties are bred to withstand drought conditions and use water more efficiently, which is crucial in temperate production zones facing climate change [

6].

Precipitation changes affect both direct water availability for irrigation and broader hydrological systems supporting rice cultivation [

67]. Increased humidity from higher rainfall can promote disease development, indirectly affecting both yield potential and quality parameters, particularly milling quality. Excessive rainfall sometimes causes waterlogging issues, though rice demonstrates better tolerance to saturated conditions than many other broadacre crops. This was evident in Australia

’s Northern Rivers region, where rice crops experienced fewer losses than other commodities during extreme flooding in February and March 2022 [

19].

Extreme precipitation events during grain filling, particularly those combining increased rainfall with reduced solar radiation, significantly reduce whole grain percentage while increasing the proportion of immature and chalky grains. These quality impacts under wet conditions demonstrate how precipitation extremes can directly impact market value through appearance and milling quality deteriorations [

68]. Water management adaptations under changing precipitation regimes must therefore consider quality implications alongside water use efficiency objectives.

4.4. Elevated Atmospheric CO₂ Concentrations

Increasing atmospheric CO₂ concentrations present complex implications for rice production, potentially boosting yield while simultaneously altering grain quality parameters. Field experiments using Free-Air Carbon dioxide Enrichment (FACE) technology demonstrate that elevated CO₂ can enhance rice yield while deteriorating certain grain quality parameters, particularly milling quality and nutritional attributes [

69]. The mechanisms underlying these changes include altered carbon partitioning, modified nitrogen metabolism, and changes in starch biosynthesis pathways.

Research with the short-duration Australian cultivar Jarrah revealed increased yield under elevated CO₂ conditions, primarily through increased grain number and size. These yield benefits came with significant quality alterations, including firmer cooked rice texture but reduced grain nitrogen and protein concentration. Phosphorus content per grain increased under elevated CO₂, demonstrating differential effects across nutritional components. These findings highlight the need to develop rice genotypes that maintain quality attributes under rising CO₂ levels [

70] considering the possibility of quality improvement at slightly elevated CO

2 but potential deterioration in further elevation.

The nutritional implications of elevated CO₂ extend beyond protein content, with studies showing reduced grain nutrient levels but increased heavy metal concentrations under higher CO₂ conditions. Canopy warming mitigates some nutrient losses but increases metal accumulation risks when combined with elevated CO₂ [

71]. Comparative analysis of wild and domesticated rice under elevated CO₂ found increased grain size and weight across genotypes, with altered starch gelatinisation properties showing genotype-specific responses. Nitrogen and amylose content remained relatively stable, indicating differential sensitivity across quality parameters and potential genetic resources for adaptation in wild germplasm [

72].

Recent research in China examining

japonica rice under elevated CO₂ (550 μmol/mol) in open-field conditions found decreased head rice yield, increased chalky grain percentage, and reduced appearance quality. Paradoxically, cooking and eating quality improved under these conditions, evidenced by altered starch RVA profiles and enhanced palatability. However, nutritional quality declined, with reductions in essential nutrients including nitrogen, phosphorus, zinc, and amino acids [

73]. Comparative analysis between

japonica and

indica cultivars under elevated CO₂ revealed that

japonica varieties (Wuyunjing27) exhibited greater quality deterioration than

indica types (Yangdao6), suggesting potential for exploiting indica genetic resources to maintain quality under future CO₂-enriched conditions [

74].

4.5. Increased Salinity

It is important to distinguish between different types of salinity affecting agricultural systems. While irrigation salinity in broader landscapes often arises from rising water tables and inefficient irrigation practices, salinity in rice cultivation is more commonly associated with the direct use of poor-quality irrigation water, particularly in regions where freshwater resources are limited. In both cases, the diffusion of salt through the soil plays a central role, but the mechanisms and management strategies differ. For rice, the immediate concern is the accumulation of salts in the root zone from saline water, which can impair plant growth, reduce yield, and degrade soil structure over time [

75,

76,

77]. Rice demonstrates high sensitivity to salinity compared to other cereal crops, with most varieties exhibiting a salinity threshold around 3dS/m [

78].

Research examining

japonica rice under moderate salinity stress (1.11 dS/m) found compromised grain quality compared to control conditions (0.21 dS/m), with reduced amylose content and increased protein content. Interestingly, appearance quality remained relatively unaffected, suggesting differential sensitivity across quality parameters [

79]. Studies with

japonica rice (Nipponbare) under low-to-moderate salinity stress (2 and 4 dS/m) revealed that timing influences response patterns. Salinity positively influenced starch accumulation under seedling and anthesis treatments, while higher salinity levels (4 dS/m) reduced grain weight and seed viability. Protein and nitrogen content increased under these conditions without significantly altering starch fine structure or composition, demonstrating complex and context-dependent responses to mild salinity stress [

80].

While literature on salinity effects on grain composition and quality remains limited compared to its impact on yield [

75,

77,

81,

82], evidence indicates that salt-induced changes during vegetative development can significantly affect subsequent grain development, composition and quality formation [

83]. Rice demonstrates highest salinity sensitivity between the 3-leaf stage and panicle initiation, creating a critical window where salinity management has particularly significant quality implications [

77].

Comparative analysis of salt-tolerant and salt-susceptible rice varieties revealed differential quality responses across tolerance groups. Salt-tolerant varieties initially showed improved milling quality and reduced chalkiness at lower salinity levels, with these benefits diminishing at higher salinity. Salt-susceptible varieties demonstrated consistent quality degradation as salinity increased. This variable response suggests potential for targeted breeding, utilising salt-tolerant germplasm to maintain quality under increasingly saline conditions [

84]. Interestingly, moderate salt stress (0.1% NaCl) improved appearance, milling, and eating qualities in high-quality

japonica cultivars despite yield reductions. These improvements corresponded with favourable changes in starch structure and physicochemical properties, suggesting potential for cultivating premium rice in mildly saline environments [

85].

4.6. Extreme Weather Events

Australian agriculture faces increasing disruption from more frequent extreme weather events, including floods, droughts, and bushfires [

86]. The devastating 2019-2020 Australian bushfires exemplify these impacts. While major agricultural areas avoided direct fire damage, associated drought conditions severely reduced crop yields, with irrigation storages depleted to critical levels. These conditions produced the smallest rice crop in Australian production history, demonstrating extreme event impacts on production capacity [

23].

Drought conditions severely affect both rice yield and quality parameters [

47]. Water limitation during grain development leads to multiple quality defects, including smaller grain dimensions, incomplete grain filling, increased chalkiness, and reduced milling quality. Drought stress often causes grain cracking, directly affecting appearance and market value, while potentially altering biochemical composition, including reduced amylose content affecting cooking quality [

45,

87].

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme events poses challenges for quality maintenance in temperate rice production. These events often create compound stresses combining temperature extremes, water limitations, and altered radiation conditions that affect multiple quality parameters simultaneously. Developing adaptation strategies addressing these compound stresses requires integrated approaches spanning genetics, agronomy, and water management to maintain quality stability under increasingly variable climate conditions.

5. Differential Climate Vulnerability Across Rice Quality Classes

Temperate rice-growing regions cultivate diverse quality classes, each demonstrating distinct climate vulnerabilities related to their biochemical composition, genetic background, and quality parameters.

Table 1 synthesises current understanding of benchmark varieties, quality characteristics, and climate vulnerability across quality classes in temperate production regions.

5.1. Mechanistic Basis of Differential Climate Responses

The variation in climate vulnerability across rice quality classes stems from underlying differences in biochemical pathways during grain development influencing yield and quality. Medium-grain

japonica varieties demonstrate sensitivity to heat stress during grain development due to temperature effects on starch synthase activity, which regulates amylose synthesis. Elevated temperatures (>30°C) during grain filling disrupt the expression and activity of granule-bound starch synthase I (GBSSI) enzyme, directly reducing amylose content and altering pasting properties [

88,

89].

Aromatic varieties possess unique vulnerability related to 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) accumulation pathways. Heat stress downregulates key genes in the 2AP biosynthetic pathway, including betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH2) enzyme, directly reducing the synthesis of this fragrance compound [

90]. Paradoxically, moderate drought and salinity stress can enhance 2AP concentration through increased proline accumulation, which serves as a precursor for 2AP synthesis, demonstrating how the severity of different environmental stressors can produce opposing effects on specific quality attributes [

91]. It must be noted that during high temperatures, the volatile compounds synthesized during grain development can potentially evaporate, thus retaining aroma under high temperature is a difficult challenge.

Long-grain varieties with high amylose content exhibit distinct responses to temperature fluctuations due to different starch granule architecture and amylose:amylopectin ratios. These varieties typically contain higher proportions of crystalline starch regions, which demonstrate greater susceptibility to structural disruption under temperature and moisture fluctuations, manifesting as increased kernel cracking and reduced milling quality [

92].

5.2. Geographical Variation in Quality Response

Quality response to climate stressors demonstrates significant geographical variation across temperate production regions. East Asian production systems have reported more pronounced quality deterioration under heat stress compared to Australian systems, potentially reflecting differences in night temperature profiles during grain filling [

25,

93]. European cultivation of Arborio-type varieties shows vulnerability to combined heat and drought stress, with quality deterioration more severe than observed in Mediterranean climate zones because European regions often experience more extreme and unpredictable weather patterns, and traditional irrigation practices may not be as adaptable to rapid climatic changes.[

28,

94].

These geographical differences in climate response highlight the importance of regionally specific adaptation strategies that address the quality vulnerabilities expressed under local environmental conditions. They also suggest potential for knowledge transfer between production regions experiencing similar climate challenges, though modified for local cultivars and quality parameters.

5.3. Implications for Adaptation Prioritisation

The differential vulnerability across quality classes necessitates class-specific adaptation strategies targeting the biochemical pathways and quality parameters most affected by climate stressors in each variety type. Medium-grain japonica breeding programmes should prioritise temperature stability of starch synthesis pathways, while aromatic rice adaptation requires focus on maintaining 2AP accumulation under variable temperature and moisture conditions.

Water management adaptations must consider class-specific responses, as practices like AWD (see next section) demonstrate differential quality effects across variety types. Similarly, harvest timing and post-harvest management may require quality-class specific modifications to minimise climate-induced quality deterioration, particularly for premium classes with stringent quality requirements.

6. Adaptation Strategies

6.1. Genetic Adaptation Approaches

Breeding programmes in temperate regions increasingly prioritise climate resilience traits alongside quality maintenance, recognising that genetic improvement provides fundamental adaptation pathways for quality preservation. Australian varieties such as Sherpa demonstrate enhanced cold tolerance while maintaining quality parameters under stress conditions [

25]. These breeding efforts integrate multiple resistance mechanisms to address compounding stressors in temperate environments [

47,

48].

Modern breeding methodologies accelerate climate adaptation through complementary approaches:

Diverse germplasm screening identifies genetic resources with heightened stress tolerance while maintaining quality attributes. Wild relatives and landrace collections provide particularly valuable allelic diversity for resilience traits [

51,

95].

Genomic selection tools enhance breeding efficiency for complex quality traits under stress conditions. Marker-assisted selection targeting specific quality-associated loci enables more rapid integration of beneficial alleles into elite backgrounds with higher precision than phenotypic selection alone [

96,

97].

Multi-environment and multi-season testing networks evaluate genotype × environment interactions affecting quality stability. These networks systematically assess quality maintenance across temperature and moisture gradients to identify varieties demonstrating quality robustness under variable conditions [

98].

Integrated resistance breeding addresses climate-induced shifts in pest and disease pressure that indirectly affect grain quality. Resistance to pathogens like panicle blast becomes increasingly important as climate change alters disease incidence patterns during grain development stages [

99].

Priority traits for Australian temperate conditions include enhanced water use efficiency without quality penalties, improved cold tolerance during reproductive development, and maintained grain quality under heat stress. These breeding objectives require sophisticated phenotyping approaches capable of simultaneously evaluating multiple quality parameters under controlled stress conditions.

6.2. Water Management Innovations

Water management strategies provide critical adaptation pathways for quality maintenance under altered precipitation patterns and increased competition for water resources. The Australian rice industry has developed internationally recognised water-saving approaches that balance efficiency objectives while maintaining grain quality [

17]. Two primary water management innovations demonstrate significant adaptation potential:

Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) irrigation cycles flooding and drying phases to reduce water consumption while promoting root development. AWD increases starch thermal stability and alters pasting profiles in some varieties while minimally affecting other quality attributes [

100]. The practice reduces arsenic accumulation but may increase cadmium levels, creating quality-safety trade-offs and requiring context-specific evaluation [

101]. Though AWD typically reduces yield compared to continuous flooding, it generally maintains milling quality—a critical economic parameter [

102].

Delayed Permanent Water (DPW) with post-flower flush supplementation maintains milling quality when combined with appropriate nitrogen management (>60 kg/ha). This approach alters grain protein composition, affecting head rice yield and flour pasting properties while conserving water [

45]. The quality impact varies by variety, with medium-grain types generally showing better quality maintenance than long-grain varieties under DPW management.

Water-saving approaches such as AWD and DPW have demonstrated that quality-water trade-offs vary significantly across rice variety types and environmental conditions. While these methods retain elements of flooded cultivation, fully aerobic rice production where rice is grown under non-flooded, upland conditions throughout the season offers even greater water-saving potential [

103]. However, fully aerobic systems often result in notable reductions in grain quality and yield, particularly in traditionally lowland varieties like Arborio or other

japonica types, which are not well adapted to dry soil conditions [

104]. Integrated management systems that account for variety-specific responses—such as adjusting planting dates, variety selection, and nitrogen management—provide the most effective adaptation pathway for maintaining quality while reducing water use [

105]. Incorporating fully aerobic production into this spectrum of strategies emphasizes the need for targeted varietal breeding and localised agronomic adjustments

6.3. Technological Adaptation Systems

Technological innovation provides rapidly evolving adaptation pathways for quality preservation through enhanced monitoring, prediction, and precision management capabilities. Four integrated technological systems demonstrate adaptation value:

Climate-responsive decision support systems integrate meteorological data with crop models to optimise management decisions affecting quality development. These systems enable adaptive scheduling of irrigation, fertilisation, and harvest operations based on real-time climate conditions and forecasts [

106,

107]. GPS-guided technologies further enhance implementation precision, allowing rapid adjustment to climate-induced field heterogeneity [

108].

Multi-platform sensing networks combine ground, aerial, and satellite monitoring to detect early indicators of climate stress affecting grain yield and quality. Hyperspectral imaging technologies can identify temperature and moisture stress before visible symptoms appear, enabling pre-emptive management adjustments to preserve quality [

109]. Soil sensor networks monitoring moisture, temperature, and nutrient status provide complementary data on root-zone conditions influencing grain development [

110].

Variable-rate application (VRA) systems optimise resource distribution based on field-specific conditions, mitigating climate-induced spatial variability effects on quality development by responding to microclimate variations within the field and allocating water and nutrients to normalise growing conditions. While widely proven in sprinkler- or drip-irrigated systems, their use in conventional flood-irrigated rice remains largely at the research and pilot stage [

111].

Automated irrigation infrastructure adjusts water distribution based on real-time evapotranspiration data and climate forecasts. These systems prevent both water stress and excess moisture conditions that compromise quality, maintaining optimal hydration despite reduced rainfall predictability or increased evaporation rates [

112].

The integration of these technological systems creates comprehensive adaptation platforms capable of maintaining quality parameters despite increasing climate variability. Their effectiveness depends on continued improvement in climate prediction capabilities and development of quality-specific stress indicators detectable through remote sensing technologies.

6.4. Advanced Quality Assessment Methodologies

Novel quality assessment technologies provide essential adaptation tools by enabling rapid evaluation of climate effects on quality parameters and facilitating selection of climate-resilient phenotypes. Four complementary assessment approaches demonstrate value for climate adaptation:

Hyperspectral phenotyping platforms rapidly map chemical composition within individual grains using visible and near-infrared wavelengths. These technologies detect internal quality characteristics including protein distribution, chalkiness development, and structural integrity with minimal sample preparation [

113,

114]. This capability enables identification of varieties maintaining quality under stress and detection of climate-induced quality deterioration before visible symptoms appear.

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) systems provide rapid, non-destructive quality evaluation across multiple parameters simultaneously. NIRS applications have expanded from basic protein assessment to prediction of complex quality traits including chalkiness, head rice yield, grain dimensions, amylose content, and viscosity profiles [

115]. These systems enable high-throughput screening of breeding material for quality stability under stress conditions.

Machine learning algorithms integrate multi-parameter data to predict quality outcomes with increasing accuracy. Random Tree modelling approaches have demonstrated superior effectiveness for predicting quality parameters from spectral data [

116,

117], while artificial neural networks reliably predict both biochemical and functional quality attributes simultaneously [

118]. These computational approaches enable more sophisticated understanding of climate-quality interactions and identification of resilient phenotypes.

Genomic and metabolomic profiling tools identify molecular signatures associated with quality maintenance under stress. DNA barcoding approaches characterise genetic resources for quality stability [

119], while metabolomic analysis reveals biochemical pathways maintaining quality despite environmental fluctuations [

120]. These molecular techniques accelerate development of climate-resilient varieties with stable quality profiles.

The integration of these assessment methodologies with adaptation strategies creates feedback systems capable of continuous improvement. As climate conditions evolve, these technologies provide increasingly precise understanding of quality responses, enabling more targeted adaptation interventions across genetic, agronomic, and technological domains.

7. Policy Implications for Climate Adaptation

While technical adaptation strategies provide essential pathways for maintaining grain quality under changing climatic conditions, policy frameworks significantly influence their implementation and effectiveness. Climate adaptation requires coordinated policy approaches spanning multiple governance levels to address the complex challenges facing temperate rice production systems.

7.1. Regulatory Frameworks Supporting Adaptation

Water policy frameworks represent the most significant regulatory influence on rice industry adaptation, particularly in water-constrained regions like the Murray-Darling Basin. Current water recovery policies, implemented to address broader environmental sustainability concerns, have constrained water availability for rice cultivation [

20]. Adaptive regulatory approaches that integrate climate projections into water allocation planning could enhance industry adaptation capacity while maintaining environmental objectives. This might include the development of more sophisticated carryover provisions that account for increasing climate variability and extreme event frequency [

11].

Regulatory approaches to pesticide and agricultural chemical registration require reform to accommodate changing pest and disease pressures under altered climate conditions. Current approval timeframes often fail to provide timely access to management tools addressing emerging climate-related threats, potentially compromising grain quality through increased biotic stress [

86]. Streamlined registration pathways for climate adaptation tools, particularly those with established safety profiles in comparable jurisdictions, could enhance adaptation capacity without compromising risk assessment integrity.

7.2. Economic Incentives for Quality-Maintaining Practices

Economic incentives for climate adaptation currently focus primarily on production volume rather than quality maintenance. Payment structures in the Australian rice industry have historically emphasized yield and broad quality classifications rather than specific quality parameters demonstrating climate vulnerability [

43]. Reform of payment structures to reward climate-resilient quality maintenance could better align producer incentives with adaptation objectives. This might include premium payments for maintaining amylose content stability or low chalkiness thresholds under stress conditions.

Carbon market mechanisms represent an underutilised economic incentive for quality-enhancing adaptation practices. Rice cultivation practices like AWD and DPW can simultaneously reduce methane emissions while maintaining certain quality parameters [

101]. Policy mechanisms that quantify and reward these emission reductions could enhance the economic viability of adaptation practices, particularly where quality-yield trade-offs might otherwise discourage their adoption. Research and development tax incentives currently provide limited support for private sector investment in climate adaptation technologies. Enhanced incentives targeting climate-resilient quality maintenance could accelerate technological innovation, particularly in precision management and phenotyping technologies requiring substantial development investment [

98,

121].

7.3. Research Funding Priorities

Public research funding for rice climate adaptation has focused predominantly on yield maintenance rather than quality preservation. This imbalance reflects an incomplete understanding of quality

’s economic significance within premium market segments [

122]. Reprioritisation of research funding to address quality-specific adaptation challenges could enhance industry sustainability while maintaining market positioning.

The current model of regional research prioritisation creates coordination challenges for addressing common adaptation needs across temperate production regions. Enhanced international coordination mechanisms, particularly for pre-competitive research addressing fundamental quality-climate relationships, could improve research efficiency and accelerate adaptation [

15].

Research infrastructure funding for climate adaptation facilities, particularly controlled environment chambers capable of simulating future climate conditions, represents a critical limitation for quality-focused adaptation research. Enhanced investment in these facilities would enable a more sophisticated understanding of biochemical responses to complex climate scenarios, facilitating targeted adaptation strategy development [

49].

7.4. International Cooperation Mechanisms

Knowledge transfer mechanisms between temperate rice production regions currently operate primarily through

ad hoc arrangements rather than structured cooperation frameworks. Development of more formalised knowledge exchange programmes focusing specifically on quality maintenance under climate stress could enhance adaptation capability while avoiding redundant research investments [

44]. Germplasm exchange restrictions increasingly limit access to genetic resources for climate adaptation. International policy frameworks facilitating responsible germplasm sharing for climate adaptation purposes, while respecting intellectual property considerations, could enhance breeding programme effectiveness across temperate production regions [

7]. Technical standards harmonisation for quality assessment methodologies represents an underutilised cooperation opportunity. Convergence of assessment approaches would facilitate more efficient identification of climate-resilient varieties and practices while enhancing market transparency [

115].

Towards addressing these goals, the Temperate Rice Research Consortium (TRRC) was established by the International Rice Research Institute to address challenges in temperate rice improvement through a collaborative approach [

123]. It focuses on overcoming both biotic and abiotic stresses, enhancing yield potential, improving grain quality and nutrition, and optimising water and nutrient management. The consortium promotes resource-sharing and information exchange among its 18 member countries and partner institutions. This collaboration has led to significant advancements, such as the development of cold-tolerant and high-yielding rice varieties, streamlined SOPs to assess grain quality traits for matching consumer-driven grain quality criteria’s, developing low glycemic index rice and biotic stress resistance.

8. Consumer Perspective on Climate-Induced Quality Changes

Climate adaptation strategies must ultimately address consumer expectations regarding grain quality, which will themselves evolve in response to changing market conditions and product attributes. Understanding potential shifts in consumer preferences under climate change scenarios is essential for prioritising adaptation investments and developing effective market positioning strategies. This will be addressed in the next section.

8.1. Potential Shifts in Consumer Acceptability Thresholds

Consumers in established rice markets demonstrate relatively stable preference patterns for specific sensory attributes, including texture, flavour, and visual appearance [

44]. However, repeated exposure to climate-induced quality variations may gradually shift acceptability thresholds, particularly for parameters like chalkiness that affect visual appearance more than functional cooking properties. Research examining consumer response to quality variations in wine and fruit markets suggests potential for adaptability in sensory preferences following consistent exposure to altered product attributes [

124]. Premium market segments targeting traditional rice dishes (e.g., sushi, risotto) may demonstrate greater resistance to shifted acceptability thresholds due to strong cultural expectations regarding specific quality parameters [

27]. Adaptation strategies for these market segments may require prioritisation of stability in culturally significant quality attributes rather than accepting threshold shifts. Price sensitivity influences willingness to accept quality variations, with lower-priced market segments demonstrating greater flexibility in quality acceptability thresholds [

125,

126]. Climate adaptation strategies targeting different market segments may therefore require differentiated approaches based on price-quality positioning.

8.2. Implications for Market Segmentation

Climate-induced quality changes may necessitate re-evaluation of established market segmentation strategies. Current quality class designations primarily reflect historical consumer preferences rather than climate vulnerability profiles [

33]. Integration of climate resilience characteristics into segmentation frameworks could better align market positioning with adaptation capabilities. Product differentiation based on climate adaptation attributes represents an emerging opportunity for market development. Consumer interest in sustainability credentials creates potential for premium positioning of rice varieties and production systems demonstrating climate resilience while maintaining key quality.

Geographic indication frameworks currently emphasize historical production practices rather than adaptive management approaches that maintain quality under changing conditions [

28]. Evolution of these frameworks to accommodate climate-adaptive practices while preserving distinctive quality characteristics would enhance market protection for regional production systems.

8.3. Communication Strategies Regarding Quality Variations

Transparency regarding climate-induced quality variations represents an emerging challenge for the rice industry. Current consumer education approaches provide limited information regarding environmental influences on quality attributes, potentially creating unrealistic expectations regarding consistency under changing climate conditions [

127].

Sensory education programmes for consumers represent an underutilised approach for building acceptance of climate-induced quality variations while maintaining market engagement. Research in wine markets demonstrates that enhanced knowledge of environmental influences on product attributes can increase acceptance of vintage-related variations [

128]. Communication strategies emphasising climate adaptation efforts may enhance consumer confidence in industry sustainability while building understanding of quality challenges. Integration of climate resilience messaging with quality narratives could transform potential market threats into differentiation opportunities [

19].

Retailer engagement represents a critical element of effective quality communication strategies. Current retail staff training typically emphasizes broad quality classifications rather than specific attribute variations or environmental influences [

129]. Enhanced training approaches integrating climate-quality relationships could improve consumer guidance regarding product selection and usage.

Table 1.

Rice quality classes in temperate regions: benchmark varieties, quality parameters, and climate vulnerability.

Table 1.

Rice quality classes in temperate regions: benchmark varieties, quality parameters, and climate vulnerability.

| Quality Class |

Region/Countries |

Benchmark Varieties |

Quality Parameters |

Climate Vulnerability |

Cooking/Eating Quality Response |

Reference |

| Medium-Grain Japonica |

Temperate East Asia (Japan, China, Korea), Australia, USA (California) |

Koshihikari (Japan), Reiziq (Australia), Calrose (USA) |

Soft texture, low-moderate amylose (16-18%), glossy appearance, good milling quality |

Heat stress: decreased amylose content, increased chalkiness, altered crystallinity and gelatinisation temperature, increased protein content

Elevated CO₂: increased yield, decreased protein and quality |

Heat stress produces stickier, softer rice; increased protein potentially reduces stickiness |

[4,70,88,130,131] |

| Short-Grain (Sushi Rice) |

Japan, Korea, Australia |

Koshihikari (Japan), Opus (Australia) |

Very low amylose (15-16%), high stickiness, glossy appearance |

Heat stress: increased chalkiness, grain cracking, protein content; reduced grain size, amylose and starch content.

Elevated CO₂: increased yield, decreased protein, increased chalkiness |

Texture becomes inconsistent; eating quality in Koshihikari improves under moderate stress but deteriorates under severe stress |

[33,132,133,134] |

| Aromatic Rice (Jasmine type) |

Thailand, Australia, USA |

KDML105 (Thailand), Topaz (Australia) |

Medium amylose (17-19%), distinctive aroma (2AP), soft texture |

Heat stress: reduced 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline production, increased chalkiness.

Drought/salinity: increased 2AP concentration but reduced yield |

Heat stress causes loss of characteristic fragrance; moderate salinity stress can enhance aroma while reducing other quality parameters |

[36,90,91,135] |

| Arborio (Risotto) |

Italy, Australia |

Arborio, Carnaroli (Italy), Vialone (Australia) |

High amylopectin, medium-high amylose (19-21%), chalky centre, maintains firmness when cooked |

Less tolerant to combined stressors, particularly vulnerable to heat during grain filling |

Deterioration in distinctive creamy consistency and texture essential for risotto preparation |

[28,29,136] |

| Non-Fragrant Long Grain |

USA, Australia, Temperate Eastern Europe |

Wells (USA), Doongara (Australia), Rapan (Russia) |

High amylose (22-25%), separate grains when cooked, firm texture |

Heat/water stress: increased chalkiness, reduced grain dimensions.

Salinity: decreased amylose content |

Dry, separate grain characteristics may be compromised; increased stickiness under salinity stress |

[30,92,137] |

| Basmati |

Northern India, Pakistan, Australia |

Basmati (India/Pakistan), Basmati Signature (Australia) |

Very high amylose (>25%), distinctive aroma, exceptional elongation during cooking |

Temperature fluctuations affect elongation and aroma; high temperature shortens grain filling, reduces starch and amylose content |

Reduced aroma and diminished elongation; compromised fluffiness and grain separation valued in premium markets |

[39,138,139] |

9. Conclusion

Consumer perspectives further complicate the adaptation landscape, as acceptability thresholds for quality parameters may themselves shift in response to consistent exposure to climate-induced variations. Market segmentation strategies will likely require recalibration to incorporate climate resilience characteristics, while communication approaches addressing quality variations present both challenges and opportunities for industry positioning. The integration of consumer education regarding environmental influences on quality with transparent messaging about adaptation efforts could transform potential market threats into differentiation opportunities.

The Australian rice industry exemplifies both the challenges and opportunities of temperate rice adaptation. Its historical development has created significant adaptive capacity through institutional knowledge systems, genetic adaptation programmes, and technological innovation platforms. However, intensifying climate variability, water resource constraints, and extreme event frequency create adaptation challenges exceeding historical experience. The industry’s emphasis on premium quality segments creates vulnerability where climate-induced quality modifications could undermine market positioning and economic viability.

Future research priorities should focus on four critical areas: (1) elucidating the specific genetic regulation of quality-determining pathways under variable climate conditions; (2) developing integrated adaptation systems that simultaneously address multiple climate stressors affecting quality; (3) creating predictive models connecting climate variables to quality outcomes across different production environments and management systems; and (4) examining consumer response to climate-induced quality variations to inform adaptation prioritisation and market development strategies. These research directions would significantly enhance adaptive capacity while providing more robust foundations for climate-resilient production systems that maintain the quality characteristics essential for market acceptance and consumer satisfaction.

The emerging climate adaptation landscape for temperate rice quality will require unprecedented cooperation across production regions, research institutions, market systems, and policy frameworks. Knowledge transfer between regions experiencing similar climate challenges offers value, though requiring careful calibration to local cultivars, quality parameters, and regulatory contexts. Ultimately, securing high-quality rice production in temperate regions under changing climatic conditions will depend on developing climate resilient rice varieties which secures quantity and quality of grain, creating adaptive systems with sufficient sophistication to maintain quality integrity despite increasing environmental variability and stress intensity, supported by enabling policy frameworks and effective consumer engagement strategies and strengthening the value chains.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from AgriFutures Australia Project No. PRP-013062 and PRO-016914.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Swinburne University of Technology, Australia for the Tuition Fee Scholarship and AgriFutures Australia for funding this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NSW-DPI |

New South Waled-Department of Primary Industries |

References

- Sreenivasulu, N., et al., Designing climate-resilient rice with ideal grain quality suited for high-temperature stress. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015. 66(7): p. 1737-1748.

- Wang, Y., et al., Effect of climate warming on the grain quality of early rice in a double-cropped rice field: A 3-year measurement. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2023. 7: p. 1133665.

- Tang, L., et al., Impacts of Climate Change on Rice Grain: A Literature Review on What Is Happening, and How Should We Proceed? Foods, 2023. 12(3): p. 536.

- Zhao, X. and M. Fitzgerald, Climate change: implications for the yield of edible rice. PloS one, 2013. 8(6): p. e66218.

- Kim, A.-N., O.W. Kim, and H. Kim, Varietal differences of japonica rice: Intrinsic sensory and physicochemical properties and their changes at different temperatures. Journal of Cereal Science, 2023. 109: p. 103603.

- Cordero-Lara, K.I., Temperate japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.) breeding: History, present and future challenges. Chilean journal of agricultural research, 2020. 80(2): p. 303-314.

- Reinke, R., et al., Temperate rice in Australia. Advances in temperate rice research’.(Eds KK Jena, B Hardy) pp. 2012. 1-14.