3.2.1. Group Differences in Perceptions of Disaster Risk Perception and Community Resilience: Independent Samples T-Test Results

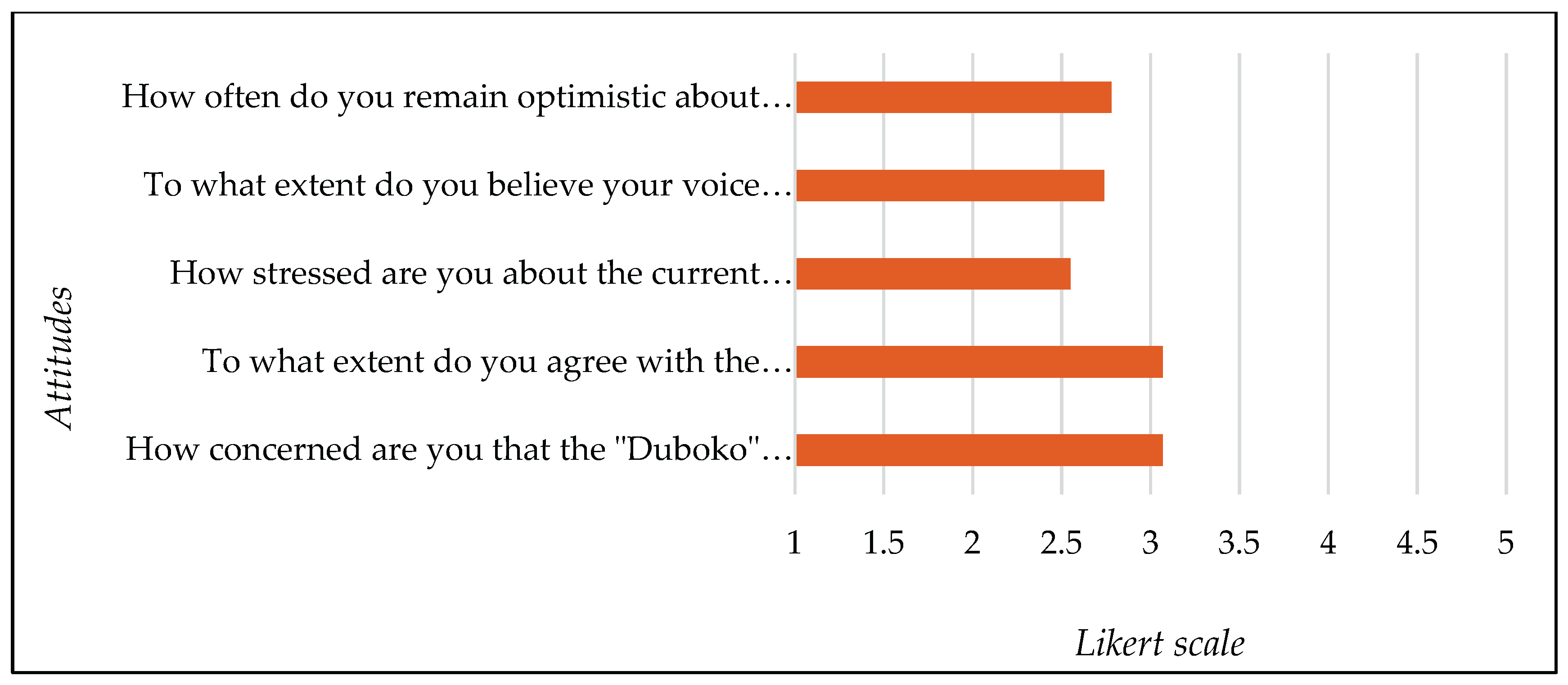

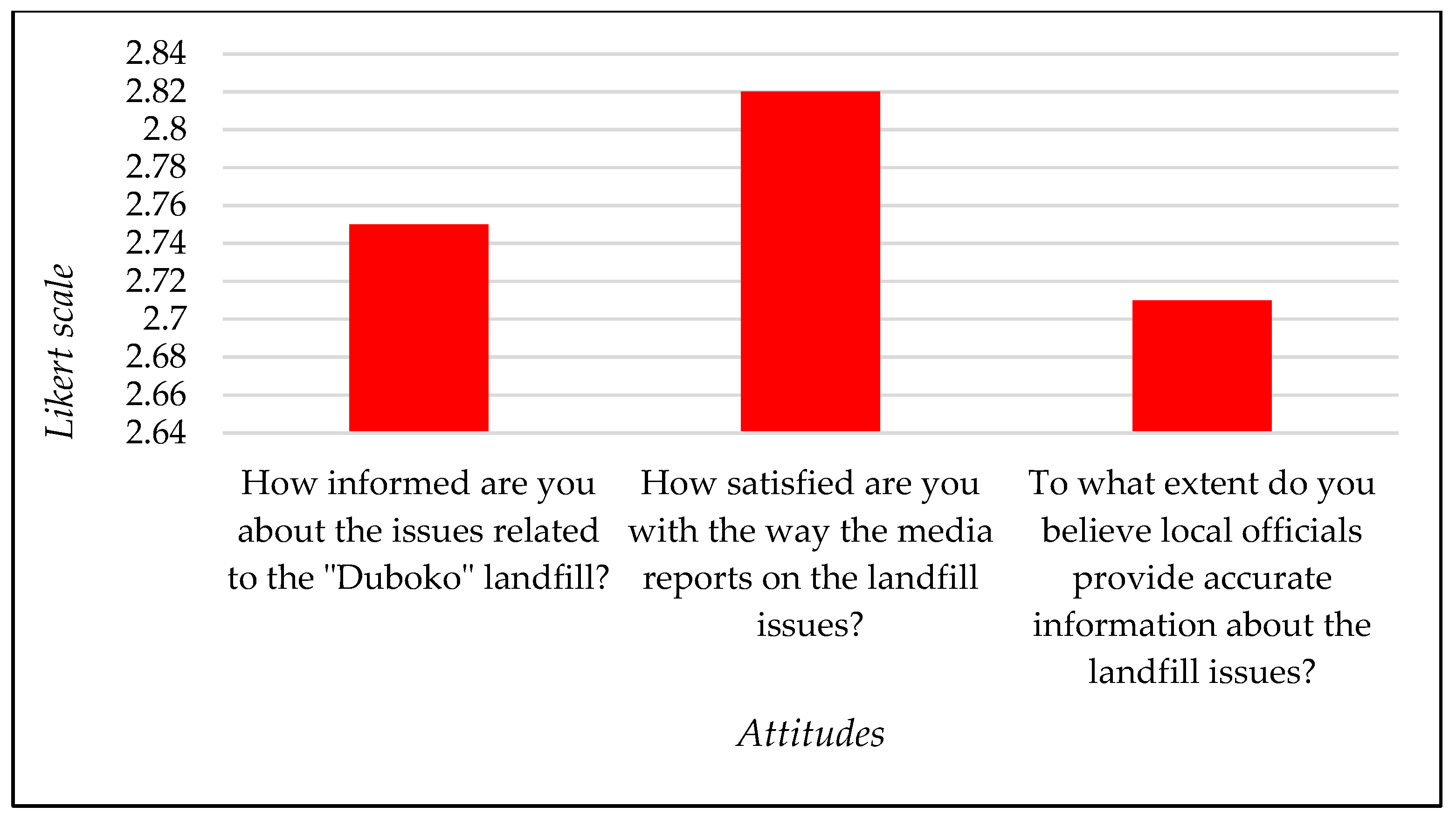

The study uncovered notable gender-related differences in how individuals perceive and respond to environmental risks tied to the “Duboko” landfill. Women reported significantly higher stress levels regarding the landfill (M = 2.69, SD = 1.25) than men (M = 2.42, SD = 1.32), a difference that proved highly significant (t = -3.613, p < 0.001). This points to a heightened emotional response among women when confronted with environmental threats.

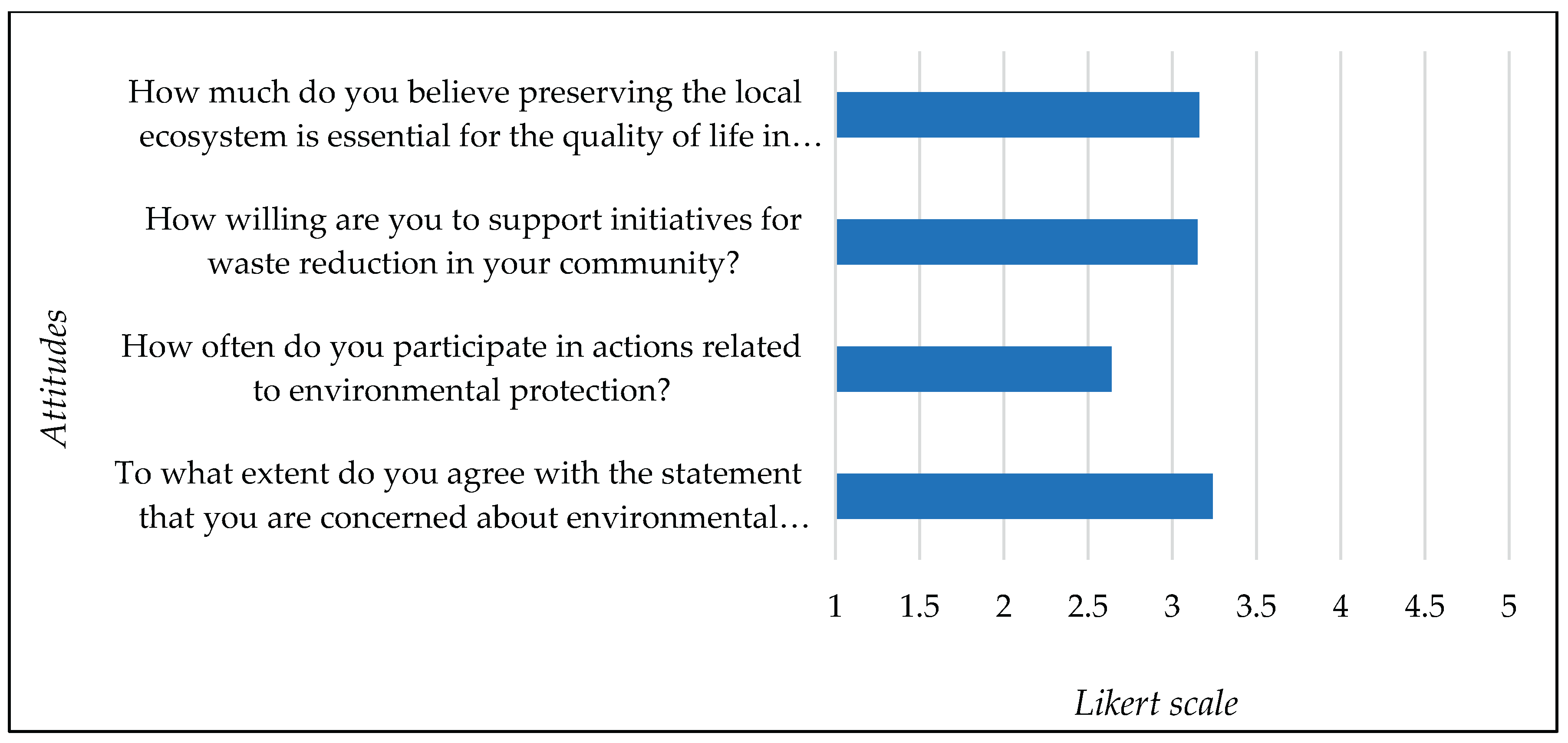

Participation in environmental protection efforts also differed by gender. Women reported greater involvement (M = 2.74, SD = 1.70) than men (M = 2.53, SD = 1.21), with the difference reaching statistical significance (t = -2.45, p = 0.014). These results echo prior research indicating that women are often more engaged in ecological and civic initiatives.

Views on environmental education revealed further contrasts. Women were more inclined to believe that workshops enhance understanding (M = 3.04, SD = 1.05) compared to men (M = 2.91, SD = 1.12), a difference that was statistically significant (t = -2.094, p = 0.036). They also demonstrated higher awareness of landfill-related issues (M = 2.84, SD = 1.16) than their male counterparts (M = 2.65, SD = 1.25), as supported by the data (t = -2.698, p = 0.007).

Another key difference appeared in perceptions of local authorities. Women showed greater trust in the accuracy of information provided by regional officials (M = 2.82, SD = 1.15) compared to men (M = 2.60, SD = 1.26), with statistical analysis confirming the gap (t = -3.119, p = 0.002).

In contrast, no significant gender differences were observed in other areas, such as institutional trust, transparency, pollution concerns, or fears about property value decline. These findings suggest a broadly shared baseline of concern and understanding across genders. In summary, women tend to display stronger emotional, informational, and participatory engagement with environmental and public health challenges. These distinctions offer essential insights for tailoring communication strategies and shaping inclusive community outreach efforts (

Table 9).

Apparent differences emerged between urban and rural residents in how they perceive and respond to environmental risks associated with the “Duboko” landfill. Rural respondents expressed significantly stronger concern for environmental protection (M = 3.46, SD = 1.12) than their urban counterparts (M = 3.10, SD = 1.18), with the difference being highly significant (t = −5.234, p < 0.001). This heightened awareness was reflected across a range of indicators.

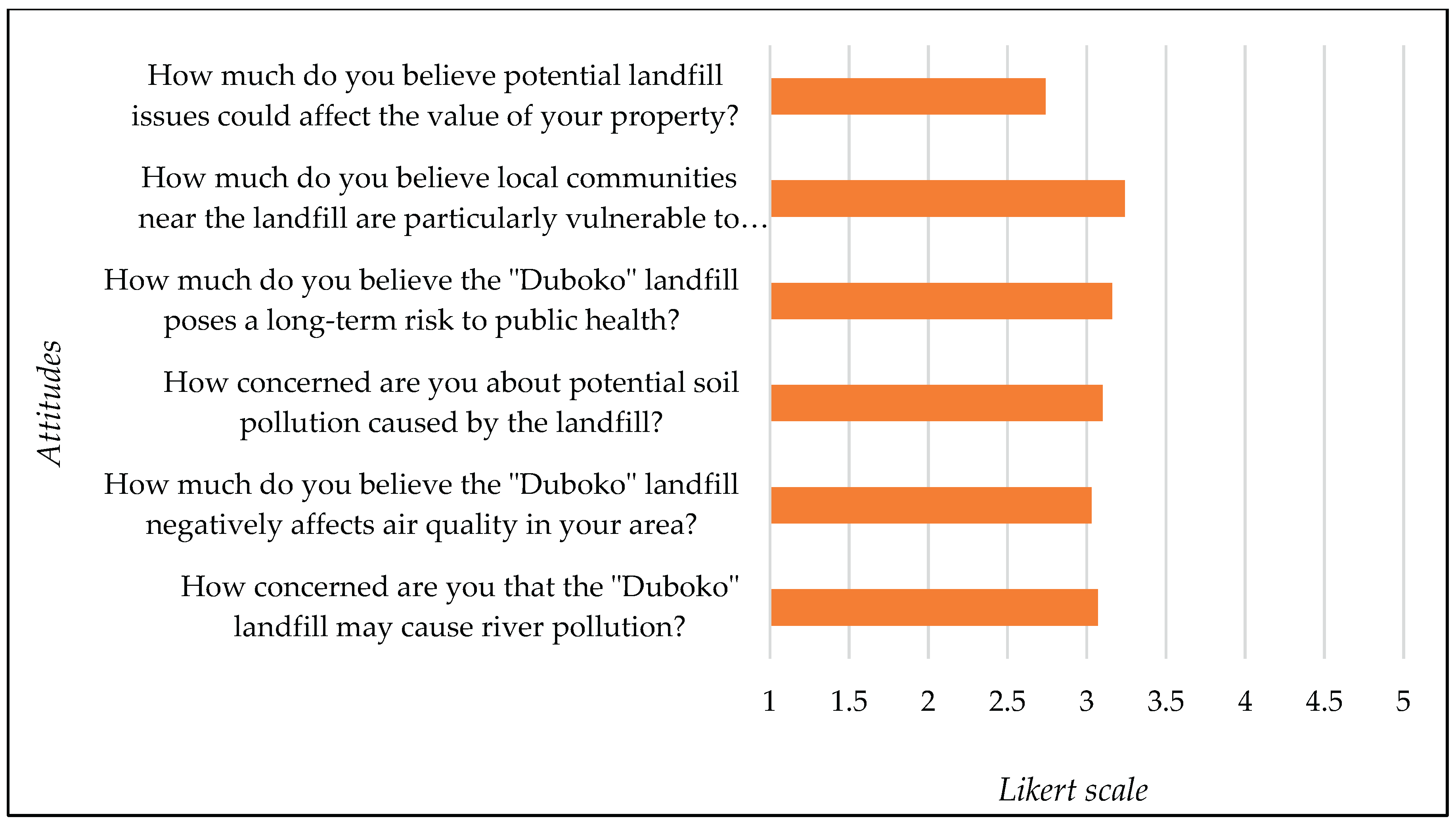

For instance, rural participants felt more capable of influencing landfill-related outcomes (M = 3.30, SD = 3.23) compared to urban residents (M = 2.91, SD = 1.18; t = −2.995, p = 0.003). They also reported higher stress related to the landfill (M = 2.66) than those in urban areas (M = 2.49; t = −2.263, p = 0.024). Concerns were particularly elevated among rural respondents regarding river pollution (M = 3.22 vs 2.97; p < 0.001), air quality (M = 3.17 vs 2.94; p = 0.002), soil contamination (M = 3.27 vs. 3.00; p < 0.001), and potential health impacts (M = 3.35 vs. 3.03; p < 0.001).

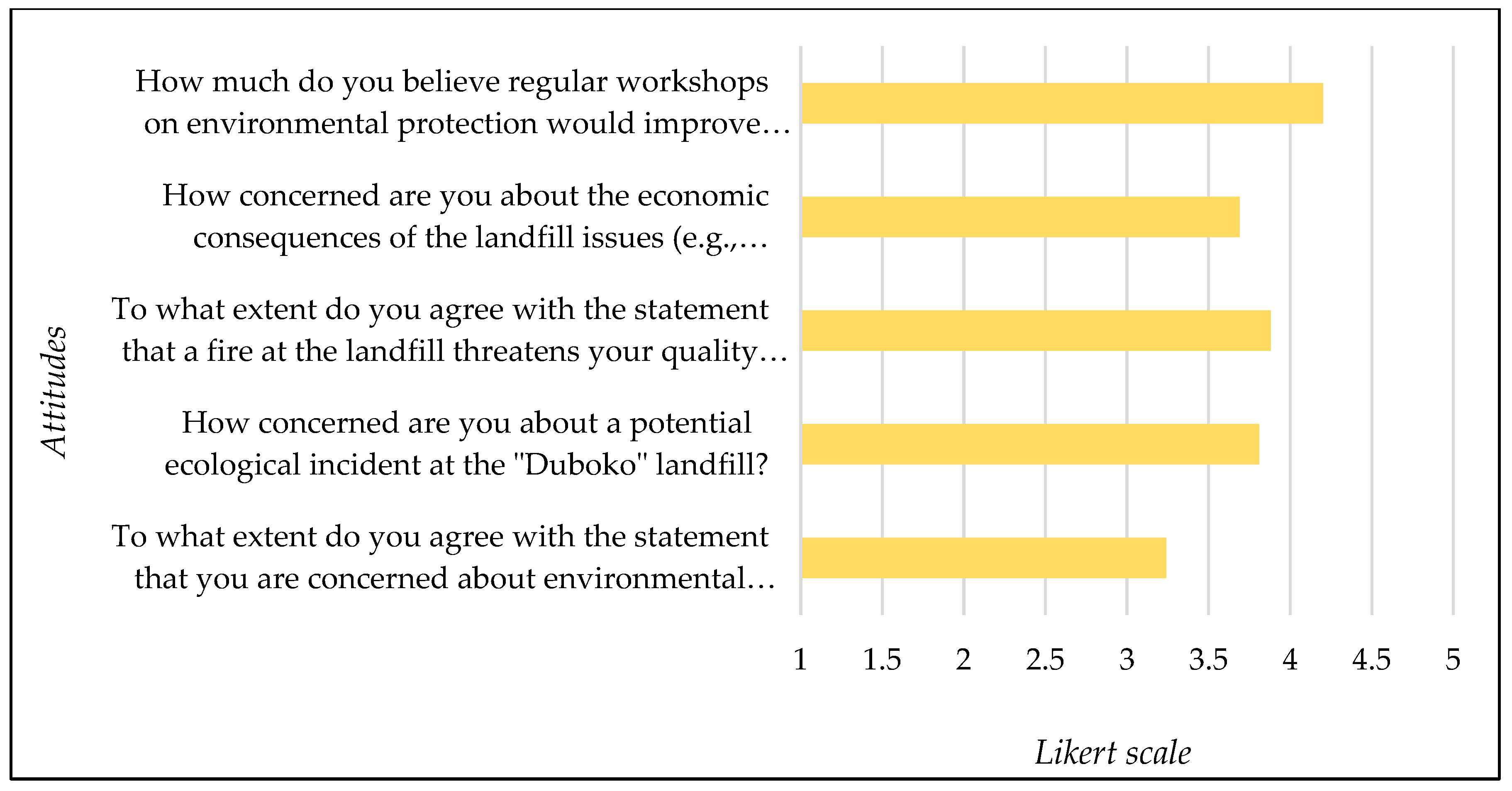

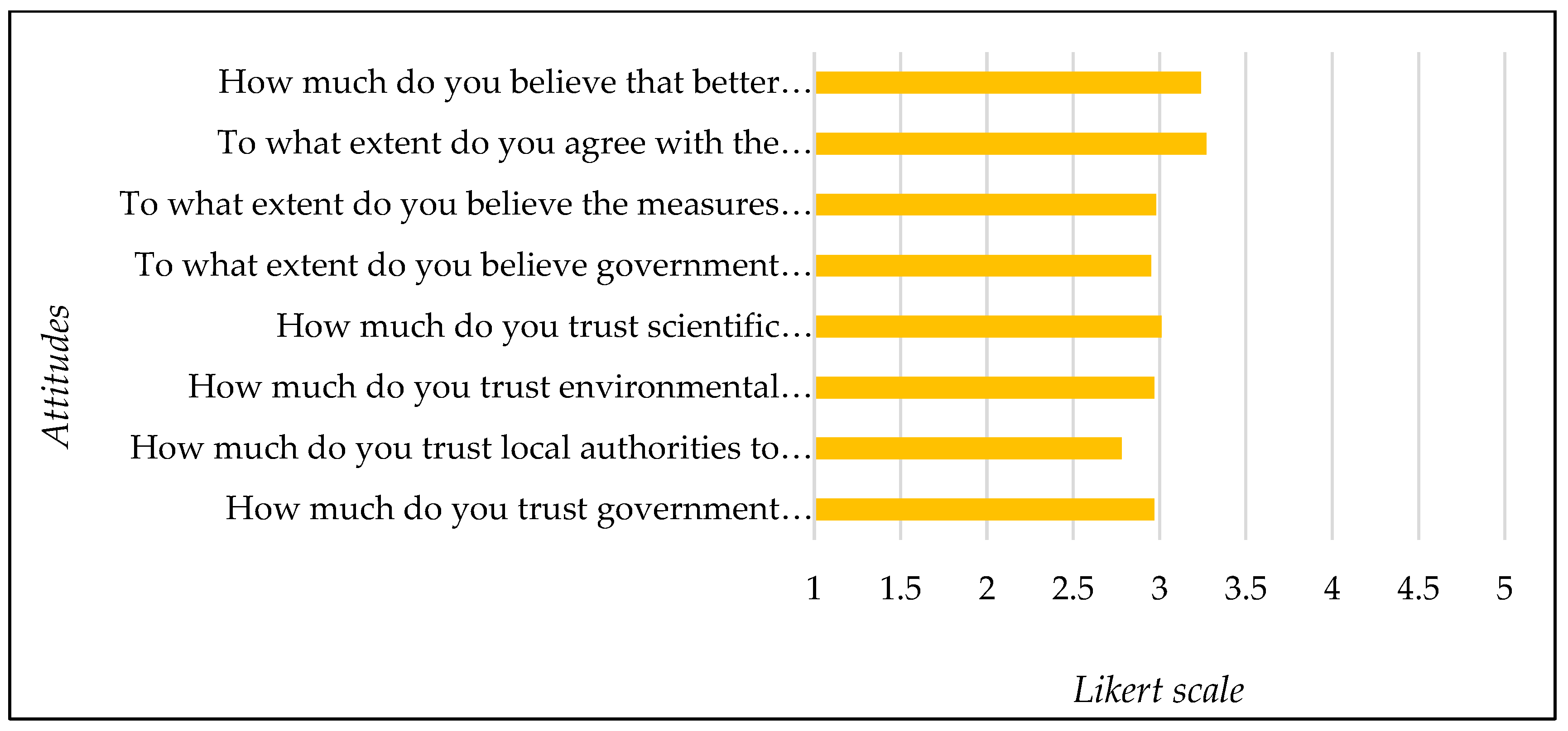

Trust in institutions and perceptions of transparency also varied. Rural residents showed higher confidence in government institutions (M = 3.15 vs 2.85; p < 0.001), local authorities (M = 2.91 vs 2.70; p = 0.003), environmental inspectors (M = 3.22 vs 2.80; p < 0.001), and scientific bodies (M = 3.12 vs 2.94; p = 0.015). They were more inclined to view government actions as transparent (M = 3.14 vs. 2.83; p < 0.001) and believed such transparency could build public trust (M = 3.44 vs. 3.15; p < 0.001).

Communication also played a role. Rural respondents were more likely to agree that improved public communication would alleviate concerns (M = 3.46 vs. 3.11; p < 0.001), and they perceived communities near the landfill as being especially vulnerable (M = 3.46 vs. 3.10; p < 0.001). They also viewed landfill problems as having a more direct impact on property values (M = 2.90 vs. 2.64; p = 0.013).

In terms of environmental action, rural participants expressed more substantial support for waste reduction efforts (M = 3.35 vs. 3.02; p < 0.001) and more strongly endorsed the importance of protecting the local ecosystem for quality of life (M = 3.28 vs. 3.08; p = 0.002). They were also more optimistic about the potential for resolving landfill-related problems (M = 2.87 vs. 2.72; p = 0.025).

Taken together, the data indicate that rural communities are more deeply engaged—emotionally, cognitively, and behaviorally—across nearly all aspects of environmental risk perception and trust in institutional response. These insights highlight the need for targeted communication and participatory approaches that reflect the heightened concerns and increased engagement levels of rural residents (

Table 10).

3.2.3. ANOVA Analysis of Sociodemographic Determinants of Disaster Risk Perception and Community Resilience

The results of the ANOVA analysis indicate that education level has a significant impact on how people perceive environmental risks, trust institutions, and engage in civic activities related to the “Duboko” landfill. One of the clearest findings relates to perceptions of institutional transparency. Participants with a secondary education reported the highest levels of perceived transparency in state institutions (M = 3.06, SD = 1.18), followed closely by those with higher education (M = 3.01, SD = 1.57). Interestingly, those without any formal education (M = 2.42, SD = 1.56) and individuals with postgraduate degrees (M = 2.62, SD = 1.13) expressed noticeably lower perceptions of transparency (F(4, 1191) = 4.59, p = 0.001).

A similar pattern emerged when looking at trust in state institutions. Again, individuals with secondary (M = 3.07, SD = 1.25) and higher education (M = 3.02, SD = 1.21) expressed more trust, whereas respondents without formal education (M = 2.67, SD = 1.67) and those with advanced degrees (M = 2.65, SD = 1.01) appeared more sceptical (F(4, 1192) = 3.34, p = 0.010). This trend was mirrored in levels of trust in environmental inspectors (F(4, 1192) = 3.73, p = 0.005), where participants with secondary education (M = 3.08, SD = 1.63) and higher education (M = 2.95, SD = 1.16) again reported the highest trust, while the extremes of the educational scale showed the lowest levels.

Education level had a significant influence on participation in environmental protection efforts (F(4, 1193) = 4.527, p = 0.001). Individuals with higher education reported the most active involvement (M = 2.79, SD = 1.19), followed closely by those with secondary education (M = 2.65, SD = 1.20). In contrast, participation was notably lower among respondents with only primary education (M = 2.33, SD = 1.06) and those without formal education (M = 2.29, SD = 1.08), suggesting a clear divide in civic engagement tied to educational background. The belief that one’s voice can help address the landfill issue also varied significantly depending on education (F(4, 1192) = 4.277, p = 0.002). Respondents with secondary (M = 2.85, SD = 1.27) and higher education (M = 2.81, SD = 1.16) were more likely to feel their input mattered, whereas those without formal schooling were the least hopeful (M = 2.22, SD = 1.07).

Perceptions of the landfill's negative environmental impact differed across educational groups as well (F(4, 1193) = 4.535, p = 0.001). People with higher education (M = 3.21, SD = 1.11) and those with secondary education (M = 3.09, SD = 1.09) viewed the landfill as more harmful, while those without formal education rated its impact less severely (M = 2.66, SD = 1.21). Further, concern over the landfill's economic consequences also showed a significant link to education level (F(4, 1193) = 4.611, p = 0.001). The strongest concerns were expressed by respondents with secondary (M = 3.10, SD = 1.11) and higher education (M = 3.03, SD = 1.08), while those without any formal education were the least concerned (M = 2.52, SD = 1.22). Next, satisfaction with how the media covers landfill-related issues varied significantly (F(4, 1190) = 6.288, p < 0.001). Respondents with higher education expressed greater satisfaction (M = 2.93, SD = 1.20), whereas individuals lacking formal education reported lower satisfaction levels (M = 2.34, SD = 1.21), pointing to potential disparities in media literacy or access to quality information.

Additionally, trust in the accuracy of information provided by local officials was influenced by education (F(4, 1190) = 3.210, p = 0.012). The highest trust levels were found among those with secondary education (M = 2.80, SD = 1.22), while those without education again reported the lowest trust (M = 2.26, SD = 1.26). Although overall trust in local authorities approached but did not reach statistical significance (F(4, 1192) = 2.052, p = 0.085), the trend still aligned with previous findings—respondents with secondary and higher education generally expressed more confidence than others.

Lastly, while education did not significantly affect concern over ecological incidents linked to the landfill (F(4, 1193) = 1.428, p = 0.222), employment status did show a significant impact (F = 4.946, p = 0.000), so further breakdowns by education aren’t needed here.

The usefulness of civic initiatives was also rated differently across education groups (F(4, 1192) = 2.88, p = 0.022). Respondents with higher education were most likely to view such initiatives as valuable (M = 3.10, SD = 1.07), with slightly lower ratings among those with secondary education (M = 2.98, SD = 1.03). In contrast, those with postgraduate degrees were the most sceptical (M = 2.68, SD = 1.22). Willingness to support local waste reduction initiatives followed a similar pattern (F(4, 1193) = 3.41, p = 0.009), with respondents holding higher education expressing the strongest support (M = 3.26, SD = 1.10) and those without formal education the least (M = 2.83, SD = 1.40).

Other dimensions also showed meaningful variation. Concern about river pollution was significantly influenced by education level (F(4, 1193) = 2.45, p = 0.044), with the highest concern expressed by respondents with higher education (M = 3.19, SD = 1.10) and the lowest by those with postgraduate degrees (M = 2.62, SD = 1.18). Similarly, education level shaped perceptions of the long-term consequences of a potential fire at the landfill (F(4, 1192) = 2.85, p = 0.024) and levels of trust in scientific institutions (F(4, 1192) = 3.17, p = 0.013), again highlighting a pattern where those with moderate education tend to express greater confidence than those at either end of the educational spectrum.

However, not all variables showed statistically significant differences. For example, levels of general concern for the environment (F(4, 1193) = 1.65, p = 0.162), stress caused by the landfill (F(4, 1193) = 1.29, p = 0.274), and the belief that one’s voice can contribute to solving the landfill problem (F(4, 1192) = 1.22, p = 0.302) were relatively uniform across educational levels. The average scores for these dimensions ranged from M = 2.50 to M = 3.42, suggesting a broadly shared perception regardless of formal education.

Overall, these findings highlight the significant role that education plays in shaping individuals' environmental perceptions and their trust in institutions. Individuals with secondary and higher education tend to express more trust, greater civic optimism, and more substantial support for local environmental initiatives. Meanwhile, those at the lower and upper ends of the educational spectrum appear more skeptical, disengaged, or ambivalent. These insights underscore the importance of tailoring communication and engagement efforts to distinct educational groups when developing strategies to foster public trust and encourage participation in environmental problem-solving.

Further ANOVA results indicate that employment status plays a significant role in shaping how individuals perceive environmental issues, trust institutions, and engage civically concerning the “Duboko” landfill. Differences across employment groups were statistically significant across a wide range of variables.

Environmental protection concern showed notable variation (F = 9.640, p < 0.001), with pensioners (M = 3.65, SD = 1.23) and seasonal workers (M = 3.73, SD = 0.99) reporting higher levels of concern than unemployed individuals (M = 2.87, SD = 1.27). Participation in environmental activities also differed by employment (F = 7.268, p < 0.001), with pensioners (M = 3.04, SD = 1.39) and part-time workers (M = 2.84, SD = 1.20) more involved than the unemployed (M = 2.39, SD = 1.12).

Belief in personal ability to contribute to solving the landfill issue was significantly stronger among full-time employees (M = 3.25, SD = 2.86) and pensioners (M = 3.36, SD = 1.35), compared to the unemployed (M = 2.37, SD = 1.19; F = 4.841, p < 0.001). Similarly, the belief that one’s voice matters (F = 8.135, p < 0.001) was highest among pensioners (M = 3.16, SD = 1.45) and seasonal workers (M = 3.22, SD = 1.21) and lowest among unemployed respondents (M = 2.38, SD = 1.25).

Stress linked to the landfill was significantly higher among pensioners (M = 3.06, SD = 1.47) and seasonal workers (M = 3.14, SD = 1.38), while unemployed individuals reported lower stress (M = 2.37, SD = 1.24; F = 9.383, p < 0.001). This trend was echoed in concern over river pollution (F = 10.529, p < 0.001), where pensioners (M = 3.40, SD = 1.14) and seasonal workers (M = 3.39, SD = 1.10) again showed more concern than the unemployed (M = 2.78, SD = 1.15).

Concern for air pollution also varied significantly (F = 8.519, p < 0.001), with higher values among pensioners (M = 3.40, SD = 1.26) and seasonal workers (M = 3.38, SD = 1.21), as compared to the unemployed (M = 2.80, SD = 1.23). Concern about soil contamination (F = 10.711, p < 0.001) followed a similar pattern, with pensioners showing the highest concern (M = 3.36, SD = 1.20) and the unemployed reporting the lowest (M = 2.76, SD = 1.14). Health-related concerns were also significantly higher among pensioners and seasonal workers across several measures: general health risk (F = 7.090, p < 0.001), potential fire consequences (F = 7.511, p < 0.001), and adequacy of fire protection (F = 12.018, p < 0.001). Concerns about specific health problems were also more pronounced among pensioners (M = 3.19, SD = 1.30) compared to the unemployed (M = 2.58, SD = 1.12; F = 5.136, p < 0.001).

Pensioners and seasonal workers were more likely to view the landfill as degrading the environment (F = 6.845, p < 0.001) and more strongly believed that a landfill fire would impact the quality of life (F = 8.496, p < 0.001). Employment status also shaped institutional trust. Pensioners and seasonal workers showed higher trust in environmental inspectors (F = 7.674, p < 0.001) and scientific institutions (F = 6.840, p < 0.001), while the unemployed expressed the least trust. Similar trends were observed in trust toward government institutions (F = 7.606, p < 0.001), where pensioners (M = 3.27, SD = 1.35) and full-time workers (M = 3.10, SD = 1.22) showed higher levels of trust compared to unemployed respondents (M = 2.59, SD = 1.28).

Views on institutional transparency (F = 7.056, p < 0.001) and the effectiveness of government measures (F = 8.946, p < 0.001) also differed significantly, with employed and retired groups expressing greater confidence than the unemployed or those in irregular jobs.

Employment status further influenced civic participation. Support for citizen associations (F = 7.379, p < 0.001) was more prevalent among pensioners (M = 3.28, SD = 1.23) and part-time workers (M = 3.22, SD = 1.19). The perceived usefulness of civic initiatives (F = 8.275, p < 0.001) was especially recognised by the employed and retired. Media satisfaction (F = 7.915, p < 0.001) and belief in the accuracy of information from local officials (F = 6.813, p < 0.001) were also highest among full-time workers and pensioners and lowest among unemployed respondents.

Finally, access to information on landfill issues varied significantly by employment status (F = 8.256, p < 0.001), with retirees and employed individuals feeling better informed than those who were unemployed.

Overall, these findings underscore the significance of employment status as a key factor influencing people’s engagement, trust, and awareness of environmental issues. Pensioners and those with stable employment appear more informed, more engaged, and more trusting of institutions—while unemployed individuals tend to report lower levels of concern, participation, and perceived influence. This suggests that future interventions must be sensitive to employment-related disparities to address community responses to environmental challenges effectively.

Table 12.

One-way ANOVA results examine the relationship between socio-economic characteristics (education, employment, property ownership, household size) and selected variables (n = 1.180).

Table 12.

One-way ANOVA results examine the relationship between socio-economic characteristics (education, employment, property ownership, household size) and selected variables (n = 1.180).

| Variables |

Education |

Employment |

Property Ownership |

Household Members |

| F |

p |

F |

p |

F |

p |

F |

p |

| Concern about environmental protection |

3.722 |

0.005 |

9.64 |

0.000 |

27.36 |

0.000 |

2.307 |

0.075 |

| Participation in environmental protection actions |

4.527 |

0.001 |

7.268 |

0.000 |

0.289 |

0.749 |

1.072 |

0.36 |

| Belief in the ability to influence solving the 'Duboko' landfill problem |

5.374 |

0.000 |

4.841 |

0.000 |

2.089 |

0.124 |

1.853 |

0.136 |

| Stress level due to the 'Duboko' landfill |

1.268 |

0.281 |

9.383 |

0.000 |

1.604 |

0.202 |

4.853 |

0.002 |

| The belief that your voice contributes to solving the problem |

4.277 |

0.002 |

8.135 |

0.000 |

3.488 |

0.031 |

0.471 |

0.703 |

| Concern about river pollution from the landfill |

5.755 |

0.000 |

10.529 |

0.000 |

13.176 |

0.000 |

2.692 |

0.045 |

| The belief that landfill negatively affects air quality |

7.85 |

0.000 |

8.519 |

0.000 |

6.898 |

0.001 |

2.086 |

0.1 |

| Concern about soil pollution caused by the landfill |

4.133 |

0.002 |

10.711 |

0.000 |

13.811 |

0.000 |

2.643 |

0.048 |

| The belief that landfill is a health risk |

3.451 |

0.008 |

7.09 |

0.000 |

16.302 |

0.000 |

2.932 |

0.033 |

| Concern about the long-term consequences of a fire at the landfill |

3.56 |

0.007 |

7.511 |

0.000 |

22.946 |

0.000 |

2.837 |

0.037 |

| Adequacy of fire protection measures at the landfill |

3.944 |

0.003 |

12.018 |

0.000 |

4.834 |

0.008 |

1.716 |

0.162 |

| Concern about potential health issues linked to the landfill |

2.198 |

0.067 |

5.136 |

0.000 |

6.609 |

0.001 |

2.556 |

0.054 |

| The belief that landfill worsens environmental quality |

4.535 |

0.001 |

6.845 |

0.000 |

4.716 |

0.009 |

0.339 |

0.797 |

| Concern about potential ecological incidents at the landfill |

1.428 |

0.222 |

4.946 |

0.000 |

2.313 |

0.099 |

2.378 |

0.068 |

| The belief that fire at the landfill threatens the quality of life |

3.092 |

0.015 |

8.496 |

0.000 |

11.513 |

0.000 |

2.215 |

0.085 |

| Concern about the economic consequences of the landfill |

4.611 |

0.001 |

7.997 |

0.000 |

9.193 |

0.000 |

2.049 |

0.105 |

| Support for citizen association activities |

1.794 |

0.128 |

7.379 |

0.000 |

5.163 |

0.006 |

4.416 |

0.004 |

| The usefulness of initiatives to solve landfill problems |

2.658 |

0.032 |

8.275 |

0.000 |

3.564 |

0.029 |

2.518 |

0.057 |

| Level of information on landfill-related problems |

3.644 |

0.006 |

8.256 |

0.000 |

2.44 |

0.088 |

2.251 |

0.081 |

| Satisfaction with media reporting on landfill issues |

6.288 |

0.000 |

7.915 |

0.000 |

5.092 |

0.006 |

2.868 |

0.035 |

| The belief that local officials provide accurate information |

3.21 |

0.012 |

6.813 |

0.000 |

0.387 |

0.679 |

1.161 |

0.324 |

| Trust in government institutions to solve the landfill issue |

5.415 |

0.000 |

7.606 |

0.000 |

8.847 |

0.000 |

7.353 |

0.000 |

| Trust in local authorities to solve the problem |

2.052 |

0.085 |

6.368 |

0.000 |

0.93 |

0.395 |

2.338 |

0.072 |

| Trust in Environmental Protection inspectors |

3.354 |

0.01 |

7.674 |

0.000 |

5.634 |

0.004 |

3.835 |

0.01 |

| Trust in scientific institutions addressing landfill issues |

8.585 |

0.000 |

6.84 |

0.000 |

11.246 |

0.000 |

5.825 |

0.001 |

| The belief that institutions are transparent about landfill issues |

6.449 |

0.000 |

7.056 |

0.000 |

10.729 |

0.000 |

3.098 |

0.026 |

| The belief that institutions take clear and practical measures |

4.074 |

0.003 |

8.946 |

0.000 |

17.319 |

0.000 |

3.898 |

0.009 |

The analysis reveals that property ownership has a significant impact on how individuals perceive environmental risks, their trust in institutions, and their level of civic engagement regarding the “Duboko” landfill.

Starting with environmental concerns, property owners expressed notably stronger concern for environmental protection (F = 27.36, p < 0.001; M = 3.40, SD = 1.09) than those without property (M = 2.76, SD = 1.24), suggesting a heightened sense of responsibility or vulnerability. This trend extended to specific environmental issues: concern over river pollution (F = 13.176, p < 0.001), air quality (F = 6.898, p = 0.001), and soil contamination (F = 13.811, p < 0.001) were consistently higher among owners, with means ranging from 3.16 to 3.26, compared to 2.86–2.93 among non-owners.

Health-related perceptions followed a similar pattern. Owners were more likely to believe the landfill poses health risks (F = 16.302, p < 0.001; M = 3.32, SD = 1.13 vs. M = 2.92, SD = 1.16) and expressed greater concern about long-term consequences of a fire (F = 22.946, p < 0.001), potential health impacts (F = 6.609, p = 0.001), and the adequacy of fire protection (F = 4.834, p = 0.008). In all cases, property owners reported higher average concern or confidence.

Property status also shaped broader environmental perceptions. Owners were more likely to believe that the landfill worsens environmental quality (F = 4.716, p = 0.009) and threatens the quality of life in the event of a fire (F = 11.513, p < 0.001), with an average concern consistently above 3.1, compared to under 3.0 among non-owners. Economic concerns also varied significantly (F = 9.193, p < 0.001), with owners expressing greater worry (M = 3.19, SD = 1.08) than those without property (M = 2.92, SD = 1.14), possibly due to perceived risks to property value.

Differences extended to civic and institutional dimensions. Owners were more likely to believe their voice contributes to solving the issue (F = 3.488, p = 0.031) and showed greater support for citizen association activities (F = 5.163, p = 0.006), along with a higher perception of the usefulness of initiatives addressing landfill problems (F = 3.564, p = 0.029). Satisfaction with media coverage also varied (F = 5.092, p = 0.006), with owners receiving higher ratings.

Trust in institutions showed a clear divide. Property owners had significantly more confidence in government institutions (F = 8.847, p < 0.001), environmental inspectors (F = 5.634, p = 0.004), and scientific institutions (F = 11.246, p < 0.001), with average scores consistently higher than those reported by non-owners. Perceptions of institutional transparency (F = 10.729, p < 0.001) and belief in the effectiveness of institutional actions (F = 17.319, p < 0.001) followed the same pattern, with property owners reporting stronger agreement across the board. Together, these findings suggest a consistent trend: individuals who own property tend to be more environmentally concerned, more engaged in civic activities, and more trusting—or at least more attentive—to institutional responses compared to those without property.

Additionally, the ANOVA analysis reveals that the number of people in a household significantly influences how residents perceive environmental threats, institutional trust, and civic engagement regarding the “Duboko” landfill. One of the most apparent distinctions appears in how people experience stress related to landfills. Households with three members report the highest levels of stress (M = 2.73, SD = 1.35), while those with four members report the lowest (M = 2.37, SD = 1.23), a statistically significant difference (F(3, 1186) = 4.853, p = 0.002). Next, concern about river pollution also varies meaningfully by household size (F(3, 1195) = 2.692, p = 0.045), with three-person households expressing the most concern (M = 3.16, SD = 1.15) compared to those living alone (M = 2.82, SD = 1.23). Similar trends are observed with soil contamination (F(3, 1195) = 2.643, p = 0.048), where individuals in three-member households again expressed the highest concern (M = 3.21, SD = 1.20). Perceived health risks associated with the landfill also differed across household sizes (F(3, 1181) = 2.932, p = 0.033), with the highest scores from three-member households (M = 3.20, SD = 1.17) and the lowest from individuals living alone (M = 2.86, SD = 1.13). Concerns about long-term consequences from potential landfill fires showed similar variation (F(3, 1191) = 2.837, p = 0.037), with a peak again among three-member households (M = 3.38, SD = 1.17).

Besides that, trust in government institutions to handle the landfill issue significantly varied as well (F(3, 1195) = 4.416, p = 0.004), with those living alone showing the least trust (M = 2.51, SD = 1.18) and four-member households the most (M = 3.14, SD = 1.18). Furthermore, trust in environmental inspectors followed a similar trend (F(3, 1195) = 2.868, p = 0.035), as four-member households reported higher trust (M = 3.09, SD = 1.13) than single-person households (M = 2.55, SD = 1.15). Perceptions of scientific institutions’ roles also differed (F(3, 1189) = 3.835, p = 0.010), with trust highest among four-member households (M = 3.14, SD = 1.19) and lowest among individuals living alone (M = 2.59, SD = 1.16). There were also notable differences in how clearly and effectively state institutions were seen to act (F(3, 1195) = 3.098, p = 0.026), with larger households again expressing more confidence.

One of the strongest findings was the belief that transparency would improve institutional trust, where agreement increased with household size (F(3, 1195) = 7.353, p < 0.001). Respondents from larger households were also more likely to believe that improved public information would ease citizens' concerns (F(3, 1192) = 3.898, p = 0.009), with concern lowest among those living alone. Support for civic activities led by citizen associations also showed variation (F(3, 1196) = 2.556, p = 0.054), with three-member households again expressing the most support (M = 3.24, SD = 1.23). Taken together, these findings suggest that individuals from larger households—especially those with three or four members—tend to show greater concern for environmental issues, more trust in institutions, and higher engagement in civic matters. In contrast, those living alone consistently report lower levels across these areas.