Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

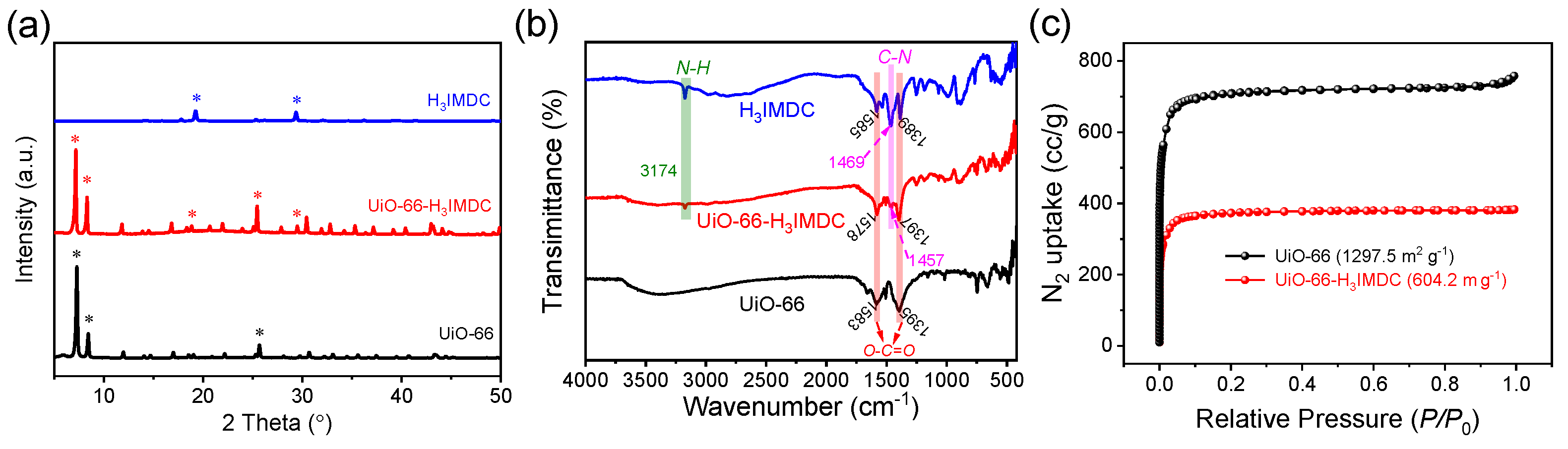

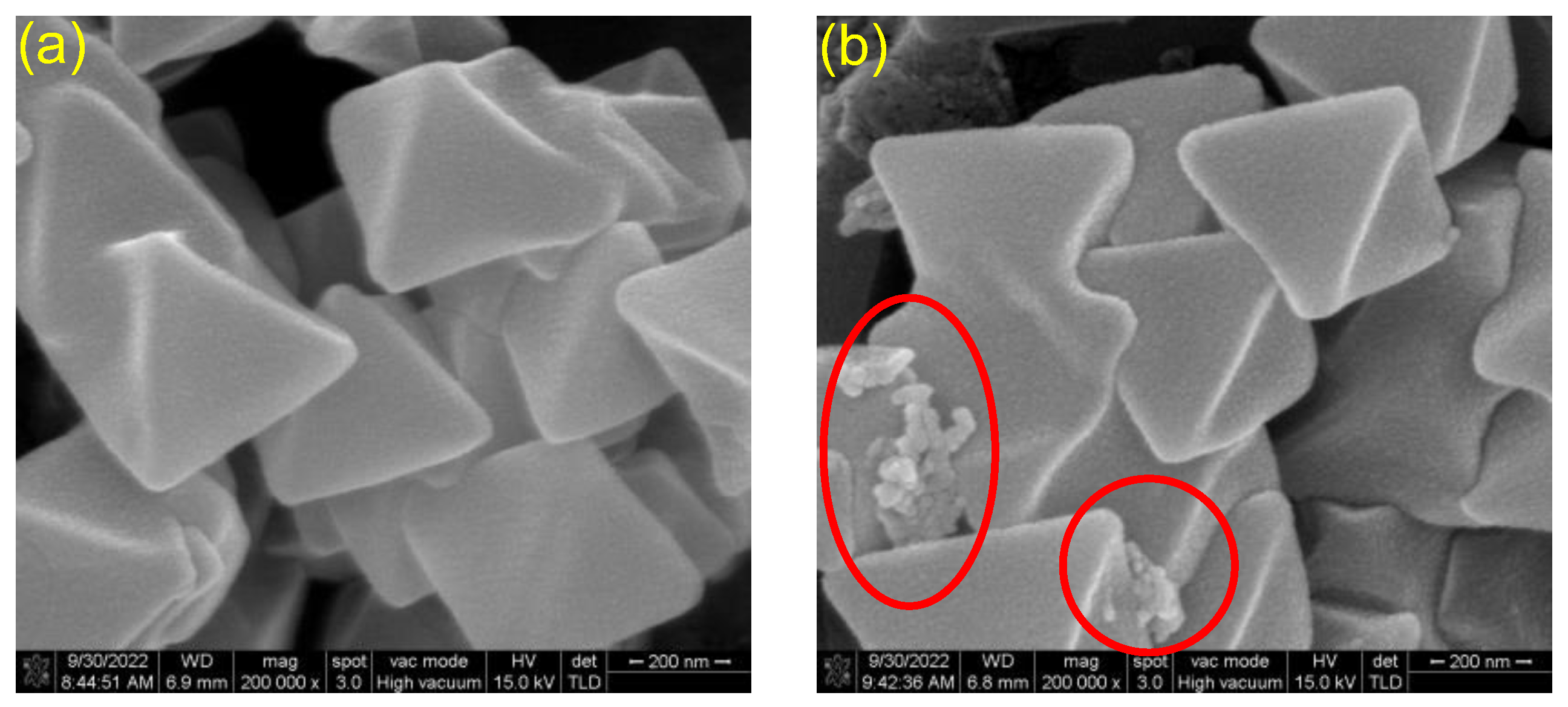

2.1. Characterization of MOFs

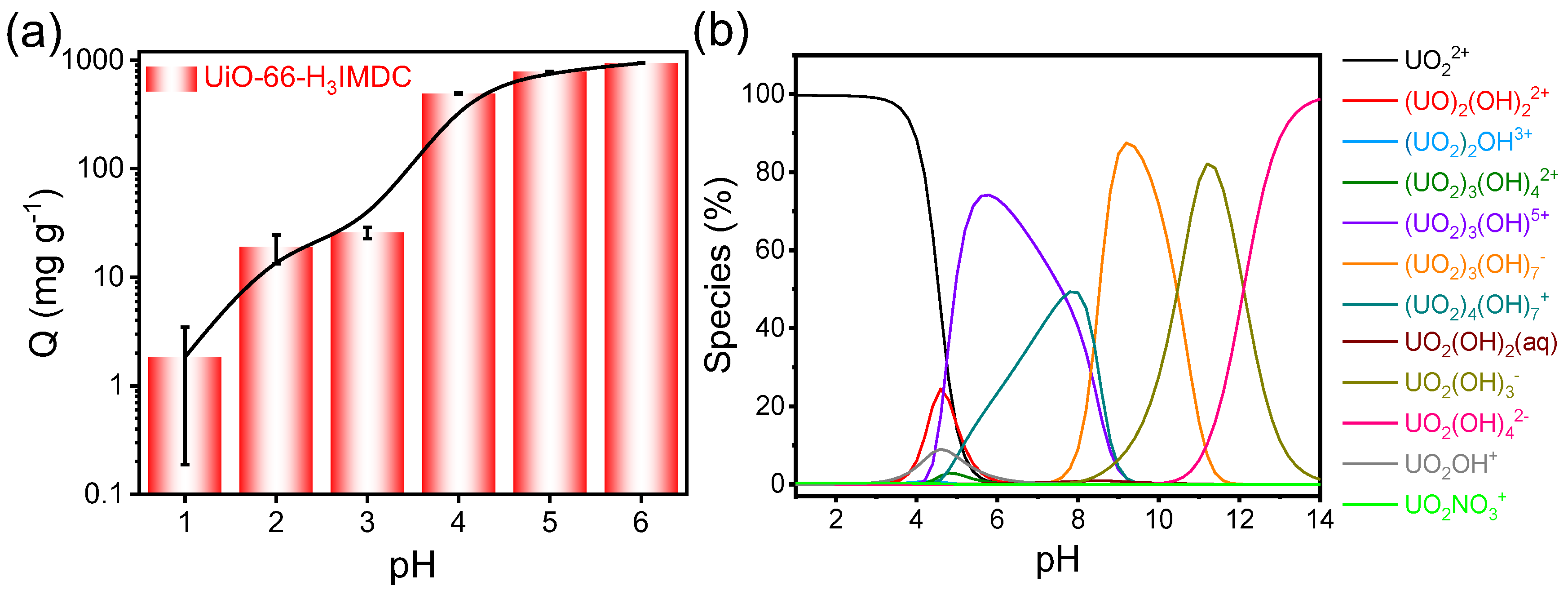

2.2. Effect of Initial pH

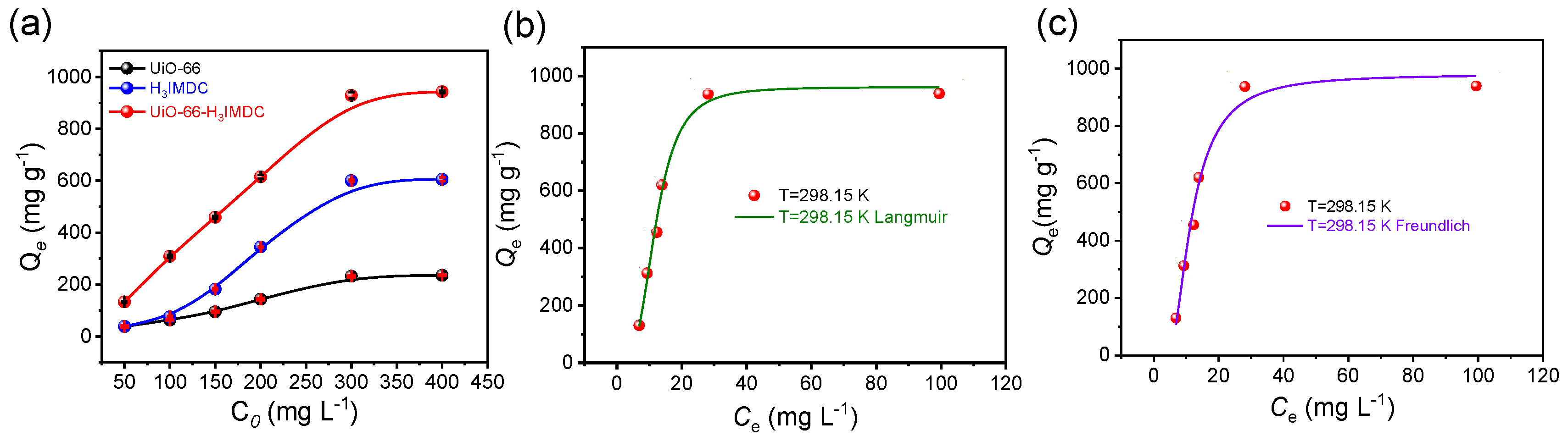

2.3. Adsorption Isotherm

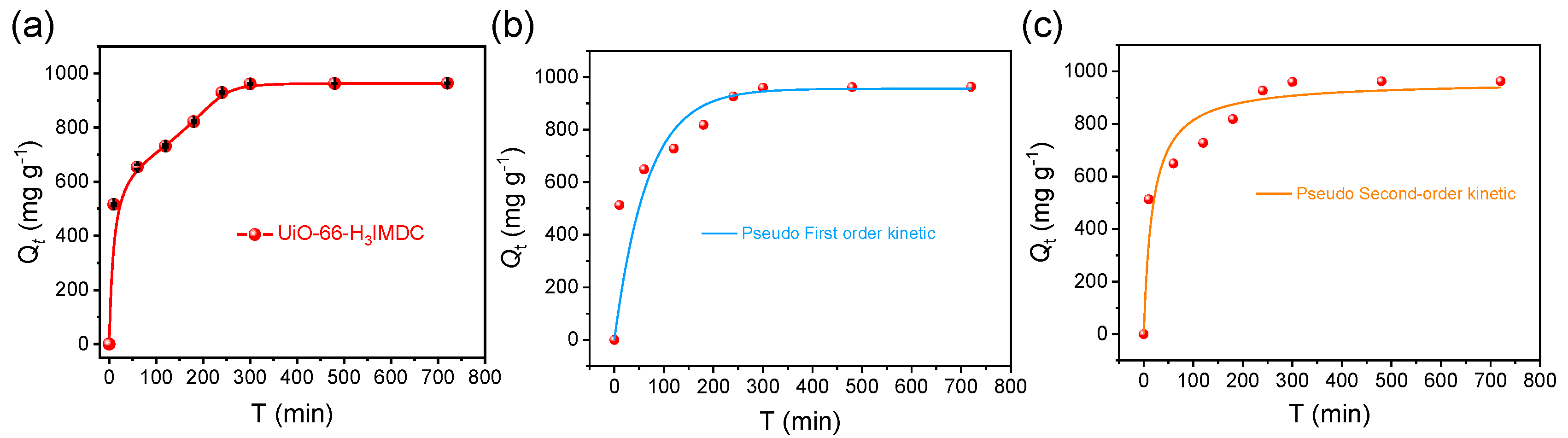

2.4. Adsorption Kinetics

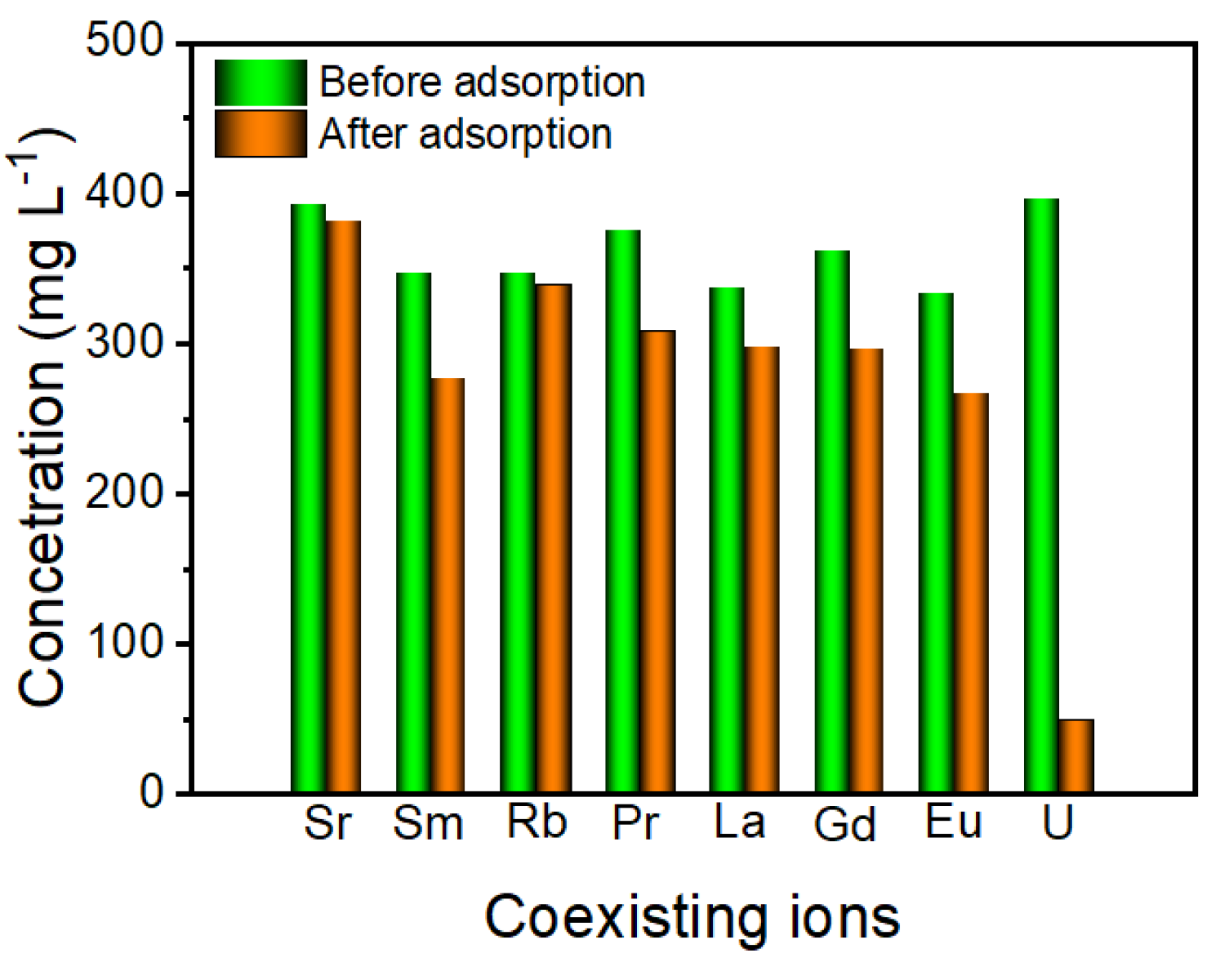

2.5. Effect of Co-Existing Ions

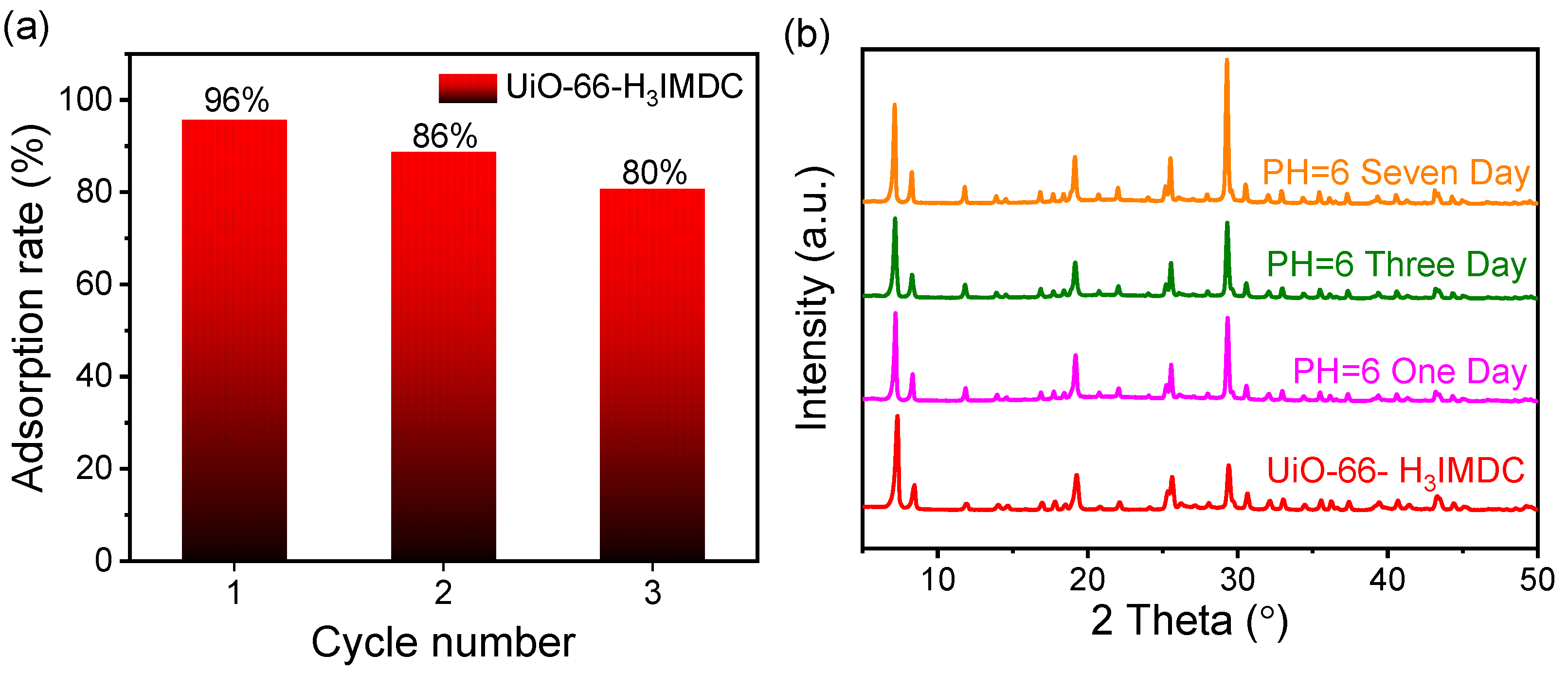

2.6. Regeneration and Stability Investigation

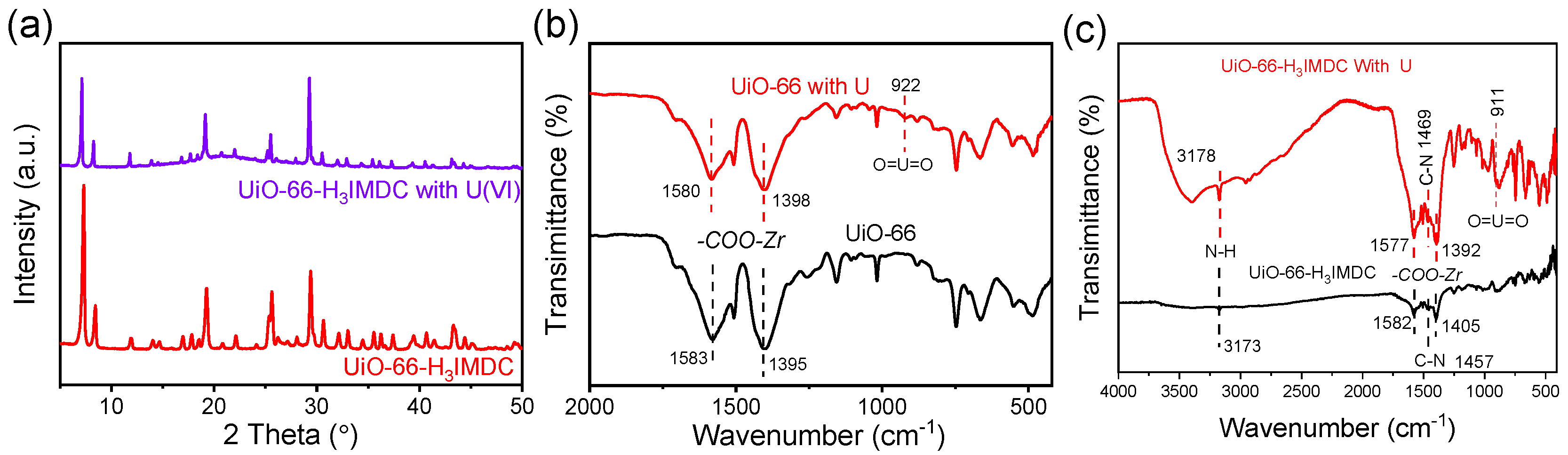

2.7. Removal Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of UiO-66(Zr)

3.3. Preparation of UiO-66-H3IMDC

3.4. Characterization Techniques

3.5. Adsorption Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Penalonga, L.; Soria, B.Y.M. A Review of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Strategies and the Spent Nuclear Fuel Management Technologies. Energies 2017, 10, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, L.; Yu, F.; Xiao, S.; Wang, C.; Yuan, D.; Liu, Y. Sulfonated heteroatom co-doped carbon materials with a porous structure boosting electrosorption capacity for uranium (VI) removal. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadadou, D.; Said, E.A.; Ajaj, R.; Hasan, S.W. Research advances in nuclear wastewater treatment using conventional and hybrid technologies: Towards sustainable wastewater reuse and recovery. J. Water Process. Eng. 2023, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Parida, V.K.; Majumder, A.; Gupta, B.; Gupta, A.K. Treatment of saline wastewater using physicochemical, biological, and hybrid processes: Insights into inhibition mechanisms, treatment efficiencies and performance enhancement. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Wang, W.; He, Y. Prediction of Uranium Adsorption Capacity in Radioactive Wastewater Treatment with Biochar. Toxics 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhan, L.; Chen, H.; Mao, J.; Chen, H.; Ma, X.; Yang, L. Study on the evaporation performance of concentrated desulfurization wastewater and its products analysis. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Meng, X. The utilization of waste by-products for removing silicate from mineral processing wastewater via chemical precipitation. Water Res. 2017, 125, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, L.B.; Silva, G.C.; Ladeira, A.C.Q. Pre-concentration and partial fractionation of rare earth elements by ion exchange. Miner. Eng. 2023, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Chen, T.; Jiao, C.; Zhang, H.; Hou, K.; Jin, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W.; He, R. Ion pair sites for efficient electrochemical extraction of uranium in real nuclear wastewater. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.; Khayatan, D.; Barzegar, P.E.F.; Ranjbar, R.; Yazdanian, M.; Tahmasebi, E.; Alam, M.; Abbasi, K.; Ghaleh, H.E.G.; Tebyaniyan, H. Biodegradation of pharmaceutical compounds in industrial wastewater using biological treatment: a comprehensive overview. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 5659–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Liu, L.; Yan, B. Adsorption of uranium (VI) by metal-organic frameworks and covalent-organic frameworks from water. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Furukawa, K.E. Cordova, M. O’Keeffe, O.M. Yaghi, The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks, Science, 2013, 341, 1230444.

- Cavka, J.H.; Jakobsen, S.; Olsbye, U.; Guillou, N.; Lamberti, C.; Bordiga, S.; Lillerud, K.P. A New Zirconium Inorganic Building Brick Forming Metal Organic Frameworks with Exceptional Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13850–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.-C.; Yuan, L.-Y.; Chai, Z.-F.; Shi, W.-Q.; Tang, Q. U(VI) capture from aqueous solution by highly porous and stable MOFs: UiO-66 and its amine derivative. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2015, 307, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaei, A.; Ghani, K.; Jafari, M. Modification of UiO-66 for removal of uranyl ion from aqueous solution by immobilization of tributyl phosphate. J. Chem. Sci. 2021, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. -G. Zhai, R.-R. Zeng, S.-N. Li, Y.-C. Jiang, M.-C. Hu, Alkyl substituents introduced into novel d10-metalimidazole-4,5-dicarboxylate frameworks: synthesis, structure diversities and photoluminescence properties, CrystEngComm, 2013, 15, 965–976.

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. Metal–organic frameworks constructed from imidazole dicarboxylates bearing aromatic substituents at the 2-position. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 7382–7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, B. Construction of cobalt-imidazole-based dicarboxylate complexes with topological diversity: From metal–organic square to one-dimensional coordination polymer. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2012, 22, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Bao, K.; Cao, J.; Qian, Y. Sunlight-assisted fabrication of a hierarchical ZnO nanorod array structure. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, J. High efficiency biosorption of Uranium (VI) ions from solution by using hemp fibers functionalized with imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylic. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, C.; Cao, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, G.; Huo, Q.; Liu, Y. Lewis basic site (LBS)-functionalized zeolite-like supramolecular assemblies (ZSAs) with high CO2 uptake performance and highly selective CO2/CH4 separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 21429–21434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Mondal, B.C.; Das, D.; Das, A.K. Use of Imidazole 4,5-Dicarboxylic Acid Resin in Vanadium Speciation. Microchim. Acta 2003, 141, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, T.; Zeng, Z.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Q. Stability of metal-organic frameworks towards β-ray irradiation: Role of organic groups. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Pan, N.; Wang, X.; Zou, H. Facile Synthesis of Phytic Acid Impregnated Polyaniline for Enhanced U(VI) Adsorption. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2018, 63, 3989–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayari, A.; Hamoudi, S.; Yang, Y. Applications of Pore-Expanded Mesoporous Silica. 1. Removal of Heavy Metal Cations and Organic Pollutants from Wastewater. Chem. Mater. 2004, 17, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, K.; Jin, T.; Feng, Z.; Lan, T.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, S. Highly radiation-resistant Al-MOF selected based on the radiation stability rules of metal–organic frameworks with ultra-high thorium ion adsorption capacity. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, C.; Feng, Z.; Ma, K.; Liu, X.; et al. Efficient capture of thorium ions by the hydroxyl-functionalized sp2c-COF through nitrogen-oxygen cooperative mechanism. Green Chem. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Yu, C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S.; Feng, Z.; Ma, K.; Ding, X.; et al. Efficient and rapid adsorption of thorium by sp2c-COF with one-dimensional regular micropores channels. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Che, R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, R.; Jing, X.; Wang, J. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-67: A promising candidate for recovery of uranium (VI) from seawater. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 547, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavka, J.H.; Jakobsen, S.; Olsbye, U.; Guillou, N.; Lamberti, C.; Bordiga, S.; Lillerud, K.P. A New Zirconium Inorganic Building Brick Forming Metal Organic Frameworks with Exceptional Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13850–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).