1. Introduction

Shopping malls (SM), as architectural models of consumer culture from the second half of the 20th century, are today confronted with multiple challenges: spatial, functional, economic, and environmental. Many of them are losing their original role and becoming spaces of degraded use, which raises the question of their future in the contemporary urban context. In this light, the issue of SM revitalization becomes not only a design challenge, but also a socially, economically, and environmentally relevant task.

Unlike approaches that favor complete demolition and new construction, contemporary architectural tendencies increasingly value strategies of transformation and adaptive reuse of existing structures, which save resources and reactivate urban zones.

The topic of SM redevelopment holds particular importance, as it integrates architectural design, facility management, and sustainable development into a unified framework, offering a model that can serve as a basis for strategic decision-making in urban planning, architecture, and investment practice. The study of best-practice examples, such as recently revitalized centers in Germany under the management of Sonae Sierra, further confirms the need for a multi-layered approach that includes functionality, durability, economy, ecology, aesthetics, and user health as interrelated quality criteria.

This research is important because it does not treat SM as disposable architecture, but rather as a resource which, with a strategically considered approach, can become a model for the sustainable transformation of contemporary cities. Particular emphasis is placed on the architectural aspect and its role within the lifecycle management system of SM facilities.

Architectural Aspect

Architectural models for the construction and redevelopment of SM are derived from the operational management requirements and functional demands of the facility. Their spatial and material articulation encompasses systems of safety, serviceability, and reliability, while simultaneously addressing the creation of an attractive environment that supports comfort, retail activity, and entertainment.

Throughout their lifecycle, these facilities are aligned with contemporary lifestyle patterns, with a particular emphasis on health and sustainability - commonly framed within the Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability (LOHAS) [

1] paradigm - which ensures long-term market resilience.

In current professional practice, architectural and operational models are adapted to market dynamics and the strategic positioning of brands, often incorporating pop-up retail formats characterized by distinct spatial and visual identities. Spatial layouts are optimized through flexibility and advanced technical infrastructure, including energy-efficient materials, climate control systems, lighting, and acoustic technologies. These components collectively enhance the quality of the user experience and contribute to the technical sustainability of the building [

1].

The future of SM lies in the strategic positioning, development, and transformation of the retail concept as a brand. A key factor and prevailing trend in future development is the engagement of younger generations through the implementation of new communication methods, advanced technologies, and smart solutions. Practical case studies indicate that various modes of SM revitalization are critical for maintaining successful commercial performance. However, in certain cases, the assessment of economic non-viability of refurbishment may lead to the decision to demolish the existing structure and construct a new facility as a more cost-effective alternative [

2].

In the United States, the 1950s marked the onset of the retail revolution (retail boom), characterized by the mass construction of SM. This period saw exponential growth in both the number of constructed facilities and visitor traffic over subsequent decades. However, since 2006, there has been no significant expansion in new SM developments.

Simultaneously, a range of external factors contributed to the gradual decline of traditional malls: the rise of e-commerce, shifting investor preferences toward open-air shopping centers, and competition from more modern retail facilities. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the situation, as malls remained inactive for extended periods due to lockdowns and public health measures. During the same timeframe, there has been a notable increase in the development of “lifestyle centers” and open-format retail zones [

3]. By the early 2000s, the United States had the highest retail space per capita in the world, which led to overproduction and market oversaturation. In Europe, SM construction significantly slowed after 2015, with a recorded decline of 6% compared to the previous year. In contrast, Asia has taken the lead in the development of new retail centers-particularly in China, where more than 4,000 new SM facilities were opened after 2020. [

4].

As of 2025. there are approximately 1,200 shopping malls operating in the United States, while projections indicate that by 2028. only around 900 may remain functional. Estimates suggest that up to 87% of large SM could be closed within the next decade. In 2022. alone, 2 million square meters of retail space were demolished [

5]. The decline in the construction of new SM in the United States is primarily attributed to

economic,

social, and

technological shifts. Additional key factors include the functional obsolescence of existing facilities, unfavorable demographic trends, and bankruptcy. The end of the retail construction boom is also a consequence of stricter urban regulations, particularly those aimed at protecting green belts and promoting sustainable urban development. Many malls have undergone revitalization processes in order to adapt to evolving market conditions. For example, Stamford Town Center in Connecticut has been transformed into a multifunctional complex featuring sports and entertainment amenities. One of the emerging models for the survival of SM involves the creation of immersive user experiences. Deloitte has identified that forward-looking malls are developing mixed-use programs that integrate residential, office, recreational, healthcare, and other innovative functions. Some centers have already adopted this strategic approach [

3]. In Serbia, a number of former department stores in nearly all major cities have been successfully transformed into SM. The phenomenon of “mall death” is attributed to inadequate business models, as well as a combination of economic and functional factors, including the obsolescence of facilities and the economic unfeasibility of renovation [

2]

.

In Western contries, the current emphasis is placed on the revitalization, adaptive reuse, and modernization of existing facilities. In Germany, for example, two-thirds of all SM were constructed prior to the year 2000, leading to the conclusion that more than half of the total retail space requires revitalization. The fact is that many of the aging shopping centers are in locations where the physical urban infrastructure is strong and the rationale for redevelopment [

6]

. The trend of developing SM within urban cores continues, often as part of comprehensive urban regeneration projects [

7]. Within the current cultural heritage protection programs, an integrative approach is being promoted, addressing the preservation and conservation of buildings through their prolonged and adaptive use [

8].

2. Materials and Methods

This research employed models for both the design of new and the monitoring and remodeling of existing SM throughout their service life, based on defined success factors. The study proposes two integrated design models grounded in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the spatial, functional, and energy-related value of buildings over time, as well as design aligned with Service Life Planning (SLP), which focuses on the structural system.

A range of intangible parameters—such as contemporary business trends, functional efficiency, environmental performance, life-cycle management, human health, and factors related to comfort and user satisfaction—are considered through their architectural aspects to enhance facility performance. The sustainability of a shopping mall’s condition results from the correlation between architecture, technical integrity, and facility management. A distinctive contribution of the original research lies in the analysis of service life through a case study conducted on a real shopping mall facility in Serbia.

The applied methodological framework includes the following phases:

Theoretical framework definition: Identification of key dimensions of sustainability (technical, economic, environmental, and socio-cultural), with specific reference to the typology of SM.

Integration of contemporary theoretical insights with practice: Adaptation and implementation of relevant scientific findings into a practical sustainability evaluation model.

Development and modification of the model: Formulation of an extended sustainability requirements matrix, incorporating criteria such as safety, comfort, and user experience, which are particularly relevant in retail environments.

Classification of sustainability disruption factors: Identification of quantitative and qualitative causes that lead to the need for facility revitalization and adaptation.

Modeling for planning and management: Structuring of sustainability factors to support decision-making in lifecycle planning, technical improvements, and architectural interventions.

This methodological framework enables systematic evaluation of the long-term sustainability of SM and is applicable both in theoretical analysis and in practical redevelopment strategies.

2.1. Theory of Ideal Shopping Malls (SM)

The theory of the "ideal" shopping mall is grounded in the optimization of commercial performance and functional organization, where the core of success lies in selecting a focused business orientation, effective leasing strategies, and clustering of retail units. Aesthetic qualities are consequently cited as contributing factors to overall success [

9]. A successful SM must meet a series of criteria, which are determined through data collection and analysis across four main thematic areas:

Location – Accessibility of the facility, involving studies on demographic gravity, availability, competition, and target groups.

Architecture and interior design – Refers to the architectural form of the building, lighting and climate control systems, interior design and decoration, as well as landscape design.

Leasing strategy – Selection of anchor and satellite tenants, and the proportion of space leased to each.

Tenant mix and clustering potential [

10] - rouping of stores with linked procurement and sales strategies, optimal spatial distribution of retail units, and Center Management (CM) operations.

The success of shopping centers can be attributed to three key groups of factors: supply, comfort, and experience. Supply encompasses the diversity and attractiveness of retail offerings, the presence of major brands, franchise networks, and competitive pricing strategies. Comfort is defined by the functional and architectural quality of space, availability of leisure and public services, extended working hours, user-friendly access, parking availability, and efficient transport connections. Experience - related factors include spatial identity, interior aesthetics, entertainment and dining options, and the presence of events and promotional activities that enhance the overall shopping atmosphere and users' sense of safety and enjoyment. The primary driver of the shopping center success concept lies in attracting a high volume of customers, with all aspects ultimately shaped by consumer preferences.

Classification of SM Success Factors According to the Sonae Sierra (SS)

According to the model developed by Sonae Sierra [

11], the success of a SM depends on precise market positioning relative to the target audience, a carefully curated tenant mix, and the facility’s ability to flexibly adapt to changes in the market environment. Continuous analysis of consumer behavior is also essential, as it enables alignment of the service and retail offerings with actual user needs, thereby increasing customer loyalty and footfall. Innovative and dynamic management, combined with ongoing enhancement of services and amenities, ensures the long-term relevance and competitive advantage of the SM within contemporary urban conditions [

11,

12].

One of the most critical factors in the early stages of architectural design—and later in all phases of planning and during the revitalization of shopping malls—is the category of

market environment [

12]. This category encompasses factors such as location characteristics from the perspective of economic, urban, and architectural development, socio-economic indicators, competitive landscape, demographic trends—including the Human Development Index (HDI), Quality of Life (QL), and Environmental Quality (EQ)—target groups, and market forecasting. Projections of market potential changes based on purchasing power indices, as well as indices of retail activity and retail concentration, are classified as independent variables. The macro-location dimension of the market environment includes the broader context surrounding the facility, taking into account the image of the place, population catchment and gravity zones, infrastructure, labor market conditions (e.g., unemployment), and is considered a conditionally dependent variable. Similarly, micro-location and traffic accessibility also fall into the category of conditionally dependent variables.

The architectural object itself - its size, footprint, number of floors, structural-functional concept, condition, and the diversity of brands and retail sectors - is classified as a direct influencing factor. Management is likewise a direct influencing factor, particularly in regard to operational leadership and brand positioning. These direct, conditionally dependent, and independent success factors are critical components in the decision-making process related to reinvestment and the future lifecycle of the facility.

Table 1, third column, presents the influencing success factors according to their success criteria and category, while the fourth column outlines the “architect’s perspective” and the role of the architect in developing alternative redevelopment concepts.

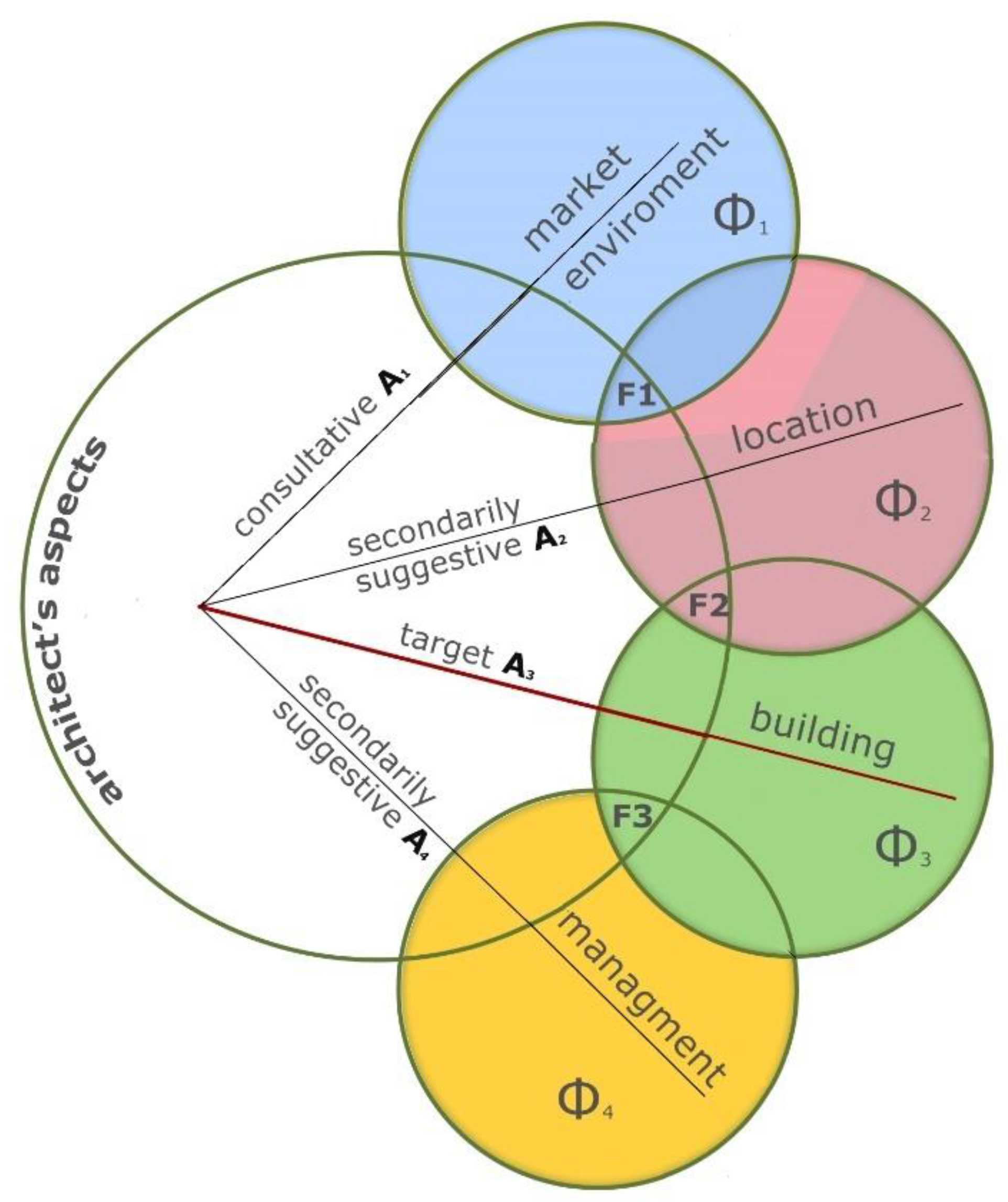

The data presented in [

12] served as the foundation for this research, which has been continuously upgraded over the years and has reached its final form (

Figure 1). The objective of this study is to highlight the role and significance of architecture in the design process through the “architect’s perspective” within the system of influencing factors.

In the mathematical model, the data related to building categories are represented as sets of fundamental random variables.

Ф - Categories, where Ф1, Ф2, Ф3 and Ф4 - represent sets of fundamental random variables corresponding to category types

F - Influencing factors, where F1, F2 and F3 enote sets of fundamental random variables associated with influencing factors.

A=A1+A2+A3+A4 - architectural aspect, defined as a set of fundamental random variables.

In the design process, the market environment Φ₁ has a consultative aspect A₁, location Φ₂ carries a secondary suggestive aspect A₂, the building Φ₃ has a target-oriented aspect A₃, and management Φ₄ also possesses a secondary suggestive aspect A₄.

The most significant influencing factor is the direct factor F₃, which pertains to the building and its management. The direct factor related to the building involves its materialization, encompassing the center layout concept, structural system, functionality, and architectural aesthetics. It also includes the condition of the structure, façade integrity, condition of visible interior surfaces, and interior fit-out, as well as tenant and sectoral mix configuration. The direct factor is associated with a target-oriented aspect in the case of the building, and a secondary suggestive aspect in the case of facility management.

The target-oriented aspect is crucial in the development of alternative redevelopment concepts for existing facilities, especially when considering the current condition of the structure or its projected performance. The conditionally influencing factor F₂ refers to the building’s size, number of floors, location, and gravitational catchment area within the market environment. F₁ represents independent factors, including demographic structure, socio-economic conditions, and competitive landscape within the broader market context.

Influencing factors are defined based on the intersection of sets: Ф ∩ A= F. This intersection represents the correlation between categories of the market environment (Φ) and architectural aspects (A), forming the basis for identifying and classifying influencing factors relevant to the planning, evaluation, and redevelopment of SM. According to this formula, the following results were obtained:

2.2. Product Life Cycle of a SM - LPSC

Throughout the period of use, SM exhibit both

micro and

macro aspects of their life cycle. The micro aspect encompasses development and management, while the macro aspect refers to the observation and analysis of the building’s overall lifespan [

13].

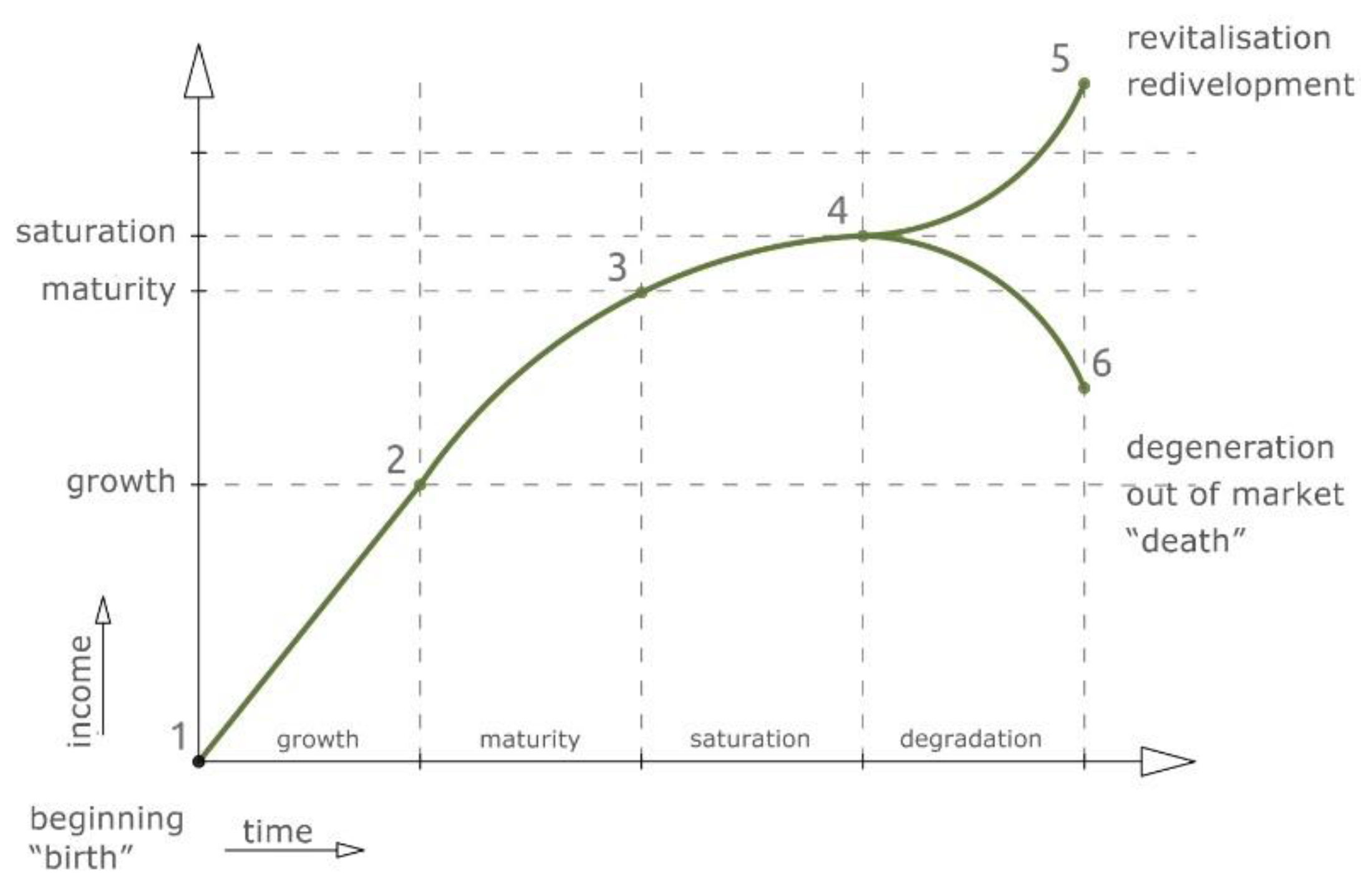

The Life Product Service Cycle (LPSC) model, along with all changes occurring over time, can be observed through the lenses of technical integrity, aesthetics, functionality, and economic viability, while also meeting environmental and health-related requirements.

The economic life cycle model can be viewed as the product lifecycle of a shopping center, spanning from procurement and sales, measured through revenue, variations in turnover, profit or loss. All temporal phases are illustrated in

Figure 2. The product life cycle of a shopping center, from a business perspective, consists of six phases [

14]:

- 1.

Planning, design, and construction of the shopping center

- 2.

Revenue growth, with the generation of peak income

- 3.

Maturity, when revenues stabilize and remain constant

- 4.

Saturation, marked by declining sales

- 5.

Revitalization / Redevelopment (Reinvestment)

- 5.a)

"Restoring momentum" by returning to an earlier phase of revenue growth

- 6.

Degeneration, when the shopping center can no longer be reactivated or operate profitably

- 6.a)

Market exit, involving the permanent closure of the shopping center

Redevelopment during phases 3 and 4 can prevent the shopping center from exiting the market.

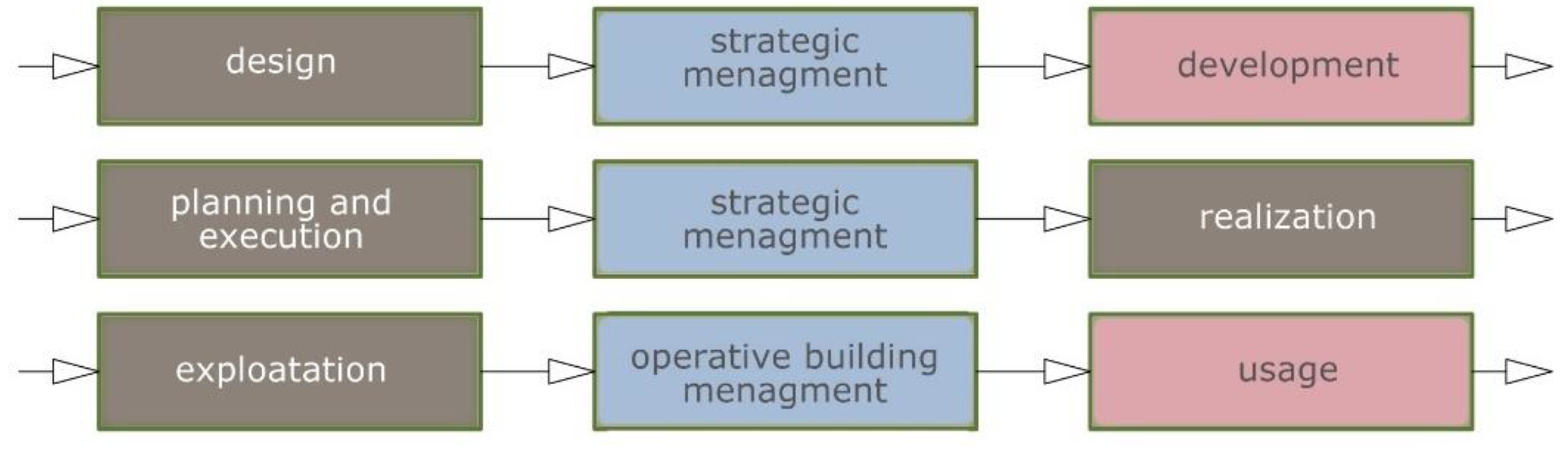

Building Life Cycle Phases - BLC

The Building Life Cycle (BLC) or Building Service Life (BSL), from the perspective of physical condition, includes the following phases: design and construction, the period between completion of construction and opening for use, the operational/use phase, the need for modernization or adaptation, potential reuse, and revitalization or expansion. This framework is defined by international ISO standards:

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) - defines the goal, scope, and application area of the analysis (including resource consumption and greenhouse gas emissions), followed by environmental impact assessment, which serves as the basis for drawing conclusions regarding overall evaluation.

Service Life Planning (SLP) is defined with the aim of improving the quality of service life design by ensuring the functionality of the building throughout its entire operational lifespan, in accordance with projected costs. This system of standards aims to minimize usage and maintenance costs, taking into account initial investment, designed performance, environmental influences, and expected durability over time.

The building life cycle of SM represents the total time span from the moment of "birth" to the "end-of-life" of the facility, and includes the following phases:

Production phase (A1–A3): Covers raw material extraction, transportation, and manufacturing of construction materials.

Construction phase (A4–A5): Involves transportation of materials to the construction site and the actual building process.

Use phase (B1–B7): Encompasses building operation, including energy and water consumption, maintenance, repairs, replacements, and renovations throughout its service life.

End-of-life phase (C1–C4): Includes deconstruction, waste transport, waste processing, and final disposal.

Additional phase (D): An optional phase that considers potential benefits from recycling and reuse of materials beyond the system boundaries [

16].

The building life cycle is illustrated in

Figure 3 across nine stages, encompassing both core and management phases.

Following prolonged use of the facility, the need for revitalization arises. Based on a detailed assessment, a comprehensive overhaul of the building is conducted according to all relevant parameters. This phase may involve re-evaluation of the structural condition and other building elements, as well as consideration of potential functional changes or expansion of the facility. After reactivation for use, multiple reuse cycles are possible until the complete exhaustion of the building’s service life.

Buildings Life Cycle Energy Needs (BLCEN) represents a critical cost factor. The lowest energy consumption occurs during building maintenance, accounting for only 4% of total energy use. The highest energy demand is associated with technical systems—including ventilation, heating, and hot water—which collectively account for 84% of total energy consumption. Energy use during the construction phase represents approximately 12% of the overall energy consumption across the building’s life cycle [

17].

Life Cycle Costing (LCC) is not limited to the investment or preliminary cost estimate of a building, but encompasses the total set of costs and benefits incurred throughout the building’s operational lifespan. These costs include all expenditures from the research and design phase, construction investment costs, ongoing operational and maintenance costs, to the costs of demolition and removal of the facility.

2.3. Redevelopment of Shopping Malls—Renewal Cycle ant the Level of Compliance with SM Requirements

The revitalization process is initiated through architectural remodeling and reinvestment, leading to the process of redevelopment. From a technical and economic standpoint, revitalization refers to the adaptation of equipment standards and overall quality of the SM to evolving market conditions, with the goal of preserving and enhancing its functional value.

More than half of the total 509 analyzed shopping centers in Germany - representing approximately 16.3 million m² of retail space - are in urgent need of revitalization or repositioning. This highlights a significant portion of facilities identified as "greyfield" centers, meaning they have lost their attractiveness and functionality, yet still retain potential for renewal [

18].

The assessment of the condition of SM facilities is based on the extent to which conditional requirements are met regarding the building’s technical characteristics and equipment, facility management, and architectural features. Obsolescence of equipment and systems with high maintenance costs (as a technical factor), decline in maintenance and management quality, outdated architectural design, material degradation, or a combination of these three factors, may serve as a basis for initiating revitalization processes. In modern shopping centers, interventions on interior retail unit elements are typically carried out every 4 to 6 years [

2].

Success Factors in SM Operations and the Enhacement of Stakeholder Interaction—Strategic Planning for Renewal, Reinvestment and Revitalization

The development, utilization, and transformation of SM involves a network of interrelated stakeholder groups, which collectively shape the entire life cycle of the facility—from the conceptual phase and construction, through operation and revitalization, to its eventual future. Although these groups differ in roles and objectives, they jointly determine the sustainability, functionality, and longevity of the SM within the contemporary urban context. Each stakeholder group has its own role and area of interest, and often their goals are conflicting. As a result, successful SM are those that manage to balance multilayered communication and the active participation of all involved actors. The revitalization of a SM requires the collaborative engagement of various stakeholder groups [

18]:

Investors and owners: A clear vision and adequate investment are essential. Owners must establish long-term goals and ensure the availability of financial resources.

Architects and designers: Play a key role in enhancing the aesthetic and functional qualities of the facility.

Leasing departments: Responsible for identifying suitable tenants and positioning the revitalized center on the market.

Tenants and brands: Selecting high-quality tenants aligned with the target audience is crucial.

Marketing professionals: Communicating changes and the new brand identity is vital for attracting customers.

Technology partners: Integration of Wi-Fi networks, mobile applications, and digital signage can significantly enhance the shopping experience.

Innovative center management companies: Ensure professional operation and (re)positioning of the center through innovative strategies.

The process of revitalization and reinvestment entails the improvement of all three conditional requirements. Their sustainability is grounded in a series of critical reassessment phases, including:

Data processing and analysis of the current condition and need for SM revitalization,

Market research as the basis for adaptation to market demands,

Potential recomposition of the SM, including Due Diligence (DD) procedures that regulate core rights and financial aspects within facility management, and

Facility management (FC) in accordance with IFMA

(International Facility Management Association) standards, focusing on preventive actions and the implementation of revitalization and safety strategies [

2].

The analysis of these phases contributes to the timely implementation of precautionary measures aimed at ensuring the long-term success of SM revitalization, and consequently, the sustained business performance of the facility. This includes all methods of monitoring and the application of a preventive measures framework based on early warning indicators.

Reinvention through design (

RTD) [

19] focuses on the transformation of traditional shopping malls into multifunctional spaces that integrate retail, residential, entertainment, educational, and community-oriented functions. This approach emphasizes adaptive reuse of existing structures in response to shifts in consumer behavior and evolving urban needs. The strategy is implemented through:

Integration with surrounding urban flows, such as pedestrian zones, parks, and marketplaces;

Conversion into mixed-use programs, including residential-commercial, cultural, and educational facilities;

Rebranding through design, incorporating natural materials, green roofs, openness, and natural lighting;

Energy efficiency and sustainability, in alignment with international certification standards such as BREEAM and LEED [

20]

.

2.4. Integrated Design Models of SM Based on the Life Cycle Approach in the Cotext of Sustainable Construction

Monitoring of Building Condition

Throughout the life cycle of a SM, it is essential to maintain its relevance, comfort, appeal, and safety, which requires continuous monitoring, timely maintenance, innovation, and adaptation from the very beginning of its operation. Changes caused by aging must be holistically assessed, as different components have varying lifespans. The primary structural system typically endures the longest, whereas interior elements, façades, equipment, and installations are subject to more frequent replacements and upgrades. Over time, depending on evolving functional requirements, there may be a need for expansion or repurposing of specific parts of the facility.

The first step in the revitalization process is often modernization, involving the application of contemporary materials and technologies to enhance visual identity and improve user comfort. Modern SM are commonly designed according to the Shell & Core concept, where the architectural expression and functionality of the building are prioritized by both investors and designers.

As the building ages, its structure undergoes technical changes—while aesthetics may become secondary, safety and durability of the core system are of critical importance. Structural interventions aimed at maintaining safety are typically capital-intensive and often represent a decisive point in determining whether further investment in the facility is justified.

During the operational phase of a building,

monitoring, assessment, and condition forecasting are essential as part of contemporary models in architectural and structural design. According to European technical regulations, a significant innovation is the design of load-bearing structures based on service life (service life design). Within these provisions, durability is treated on an equal level with load-bearing capacity—i.e., mechanical resistance or structural deformability. Service life refers to the time period during which the building maintains its intended performance and properties. Globally, increasing attention is being given to the durability of materials and structural systems, as insufficient durability leads directly to high financial demands for building revitalization. Deficiencies arising from the use of materials that do not meet design specifications, improper or irregular maintenance, and a lack of attention to durability considerations during the design phase, all contribute to the premature degradation of structural performance [

21].

Architectural Structure System

The load-bearing structures of buildings are an integral part of the architectural concept. Any compromise to the structural system or its components not only endangers property and human life, but also undermines the integrity, functionality, form, and aesthetics of the building. The architectural structure of a building is composed of three hierarchical system levels based on their significance: “

primary, secondary, and tertiary systems“[

22]. The substructure of exterior and interior elements

also falls within the scope of durability research

. Exterior cladding components

, such as façades and roofing systems, are directly exposed to environmental impacts including rain, frost, UV radiation, and atmospheric agents

, while interior finishes - such as ceilings, wall coverings, and flooring - are subjected to various physical, mechanical, and chemical influences

, all of which contribute to the material degradation over time [

23].

Material Durability

The durability of materials primarily depends on the type of material and its mechanical, physical, and chemical properties, while the environmental conditions - i.e., the surrounding context in which the building is located - represent a highly significant influencing factor [

21]. All construction materials inevitably undergo deterioration over time, resulting in the gradual loss of their initial properties. In pursuit of achieving eternal structures, historical constructions were often built with oversized dimensions and excessively high safety factors. Today, safety factors for both materials and loads are clearly defined by standards and regulations. One approach to extending the service life of a structure involves selecting materials with greater inherent durability, increasing cross-sectional dimensions, enhancing the thickness of the protective concrete cover over reinforcement, or applying anti-corrosion treatments. It is important to emphasize that human intervention—including regular inspection, maintenance, and repair—plays a critical role in the durability of both materials and structural systems. The study of material durability in structural applications is closely tied to the analysis of environmental conditions and their effects on the structure.

2.5. Service Life Based Design Concept

Service life design is defined in modern technical regulations, with clear terminology, procedures, and criteria. Structural durability primarily involves analyzing potential material degradation based on the building’s function and environmental exposure. The selection of materials and structural systems is based on the analysis of environmental agents—physical, chemical, biological, or mechanical—relevant to the intended service life of the building. It is crucial to determine whether the structure is exposed or protected, subjected to aggressive chemicals, UV radiation, impact loads (e.g., from vehicles), or embedded in soil, water, or air. A well-executed and timely assessment of these deterioration factors during the design phase can significantly extend the structure’s lifespan.

During operation, deterioration processes inevitably occur, making structural monitoring essential for early detection and timely intervention. Ideally, a systematic monitoring program should be in place to track structural changes and identify damage, optimizing maintenance costs. These costs can be substantial over the service life - sometimes exceeding the value of a newly built structure - making demolition and reconstruction a more economical solution in some cases. Damage is usually first identified visually, revealing surface defects such as cracks, abrasion, or erosion. For large structures, electronic monitoring systems are used to detect and assess structural behavior and damage. In cases of more severe degradation, laboratory testing is required. Based on this analysis, a diagnosis of the structural condition is developed, followed by intervention recommendations. Remedial work typically restores the original load-bearing capacity, although increased demands may require structural strengthening. Over time, material performance declines, while regulatory standards often require higher load capacities, making the design challenge more complex.

2.5.1. Estimated Service Life ESL of Structure or Structure Element

The calculated service life of a structure is determined based on:

The definition of the relevant limit state,

A time period expressed in years, and

The reliability level that the limit state will not be reached within that period.

In SM, service life is typically dictated by user requirements and ranges from 15 to 40 years, and can be categorized as technical, functional, or economic.

Technical Service Life (TSL): Refers to the period during which the structure maintains its technical integrity and safety, until a specified limit state is reached—i.e., until load-bearing capacity or serviceability requirements can no longer be fulfilled. This includes proper maintenance and operational reliability. TSL depends on the properties and quality of the materials, design and construction standards, user behavior, maintenance practices, and environmental protection conditions.

Functional Service Life (FSL): Denotes the period during which the structure remains in use and fulfills its intended function and user requirements, until it becomes functionally obsolete due to changing demands (e.g., repurposing, need for different access, etc.).

Economic Service Life (ESL): Represents the economically viable period during which the structure remains in use, undergoing modernization or repair, until replacement yields greater financial return than continued operation. Over time, building value decreases while maintenance costs increase. ESL is often shorter than TSL and typically ranges between 30 to 50 years for shopping centers [

24]. However, due to the high construction costs of shopping centers and the increasing maintenance expenses over time, investors expect a return on invested capital. Capital risk assessment in SM projects is often constrained by frequent market fluctuations, shifts in demand, potential disruptions in leasing, or operational downtimes. As a result, the expected return period is frequently shortened—previously estimated at 15 to 20 years, and more recently even below 10 years. During the operational phase, total operating costs tend to increase progressively and may exceed the initial investment value of the facility. By aggregating profit, initial investment, and operating costs, the economic service life of the building can be determined through optimization methods. However, economic service life alone is not a decisive factor in determining whether to revitalize or reinvest in the building.

2.5.2. Correlation Between Technical, Funkciona and Economic Service Life

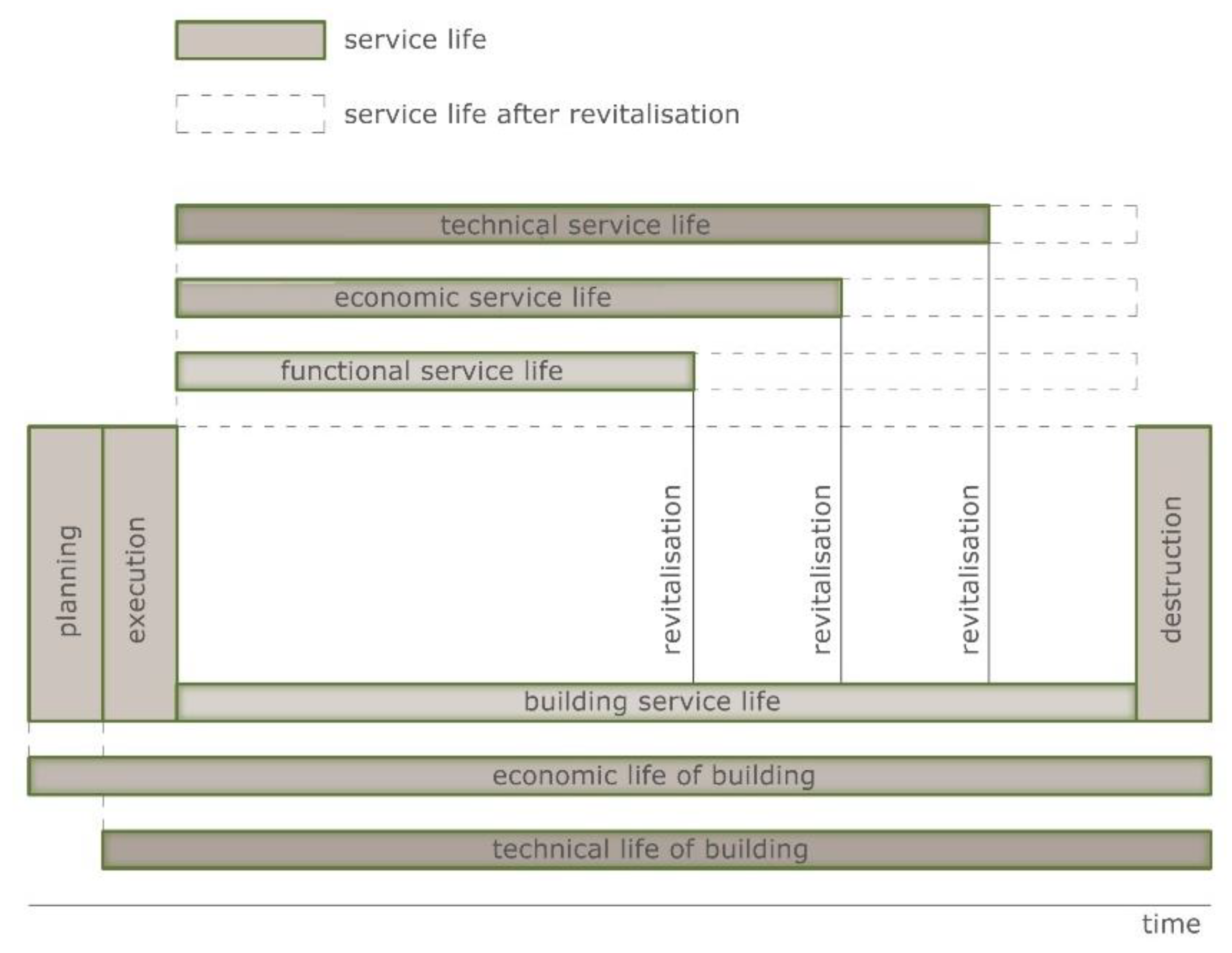

The moment of reinvestment - whether aimed at improving the facility or halting its physical and functional decline - is typically determined by the depletion of the technical or functional service life, or by the point at which the balance between the building’s residual value and the rising maintenance costs reaches economic non-viability. Economic factors related to revenue, sales, market demand, or aesthetic considerations may also justify the initiation of reinvestment once the economic service life has been exhausted. The functional service life serves as a dynamic indicator, reflecting the condition of the facility in both technical and economic terms. The correlation between technical, economic, and functional service life is graphically illustrated in

Figure 4.

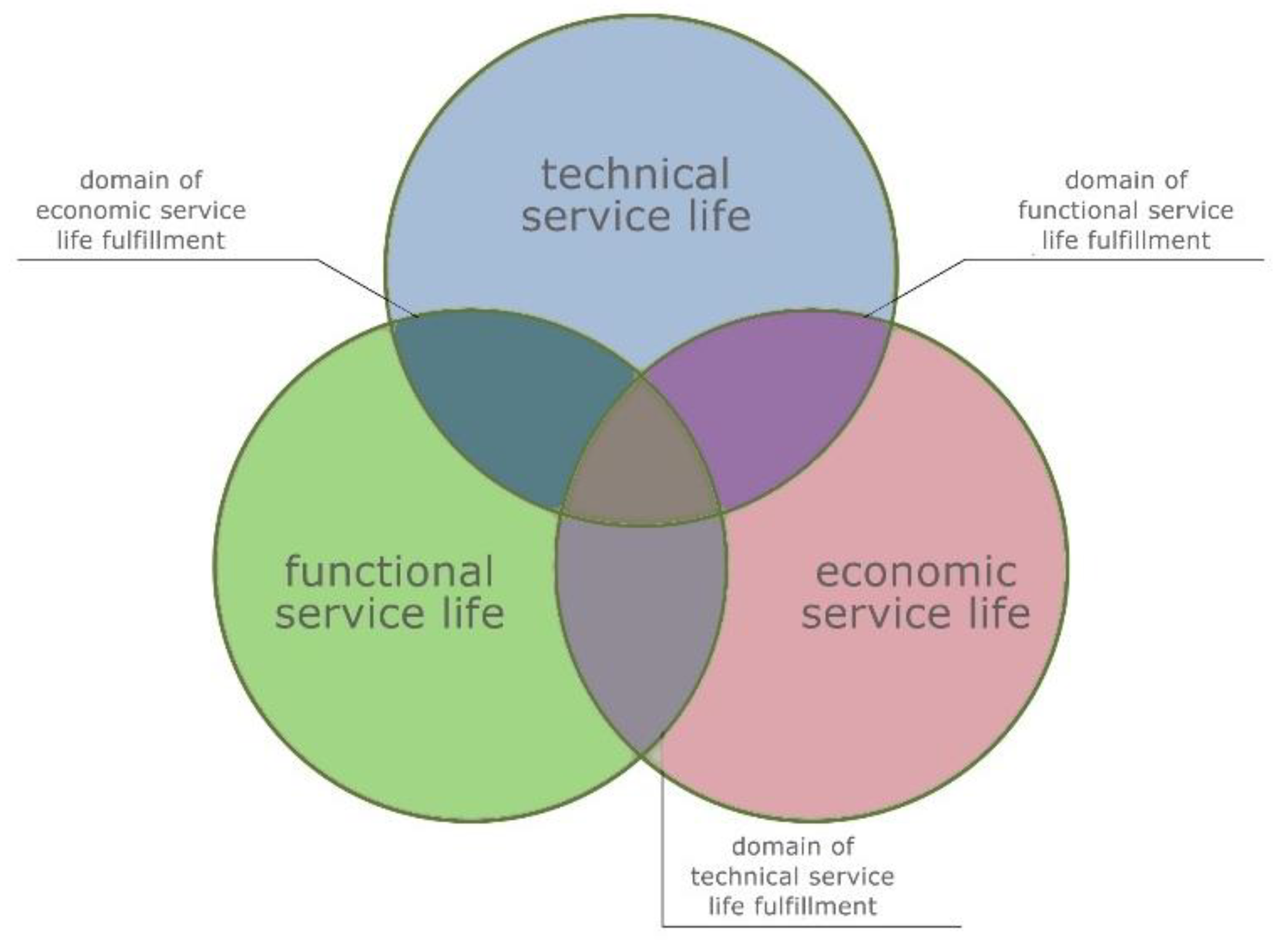

The determination of a building’s service life is possible through the fulfillment of the three fundamental criteria.

Figure 5. illustrates the respective domains of technical, functional, and economic service life. The overlapping area of all three indicates that none of the service life criteria have been exhausted, confirming the building’s continued performance and viability. The overlap of any two implies that those aspects remain active, while the third has reached the end of its service life. The absence of overlap signifies that the remaining service life has been exhausted across the other criteria.

2.6. Application of LCA Methodology in the Design, Monitoring, and Extension of SM Service Life

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a methodology applied in sustainable design, facility management, and extension of building service life, particularly in complex commercial structures such as SM. The LCA approach encompasses all aspects of a building's environmental impact throughout its life cycle—from material extraction, construction, and operation, to end-of-life and potential reuse or recycling.

LCA-Based Building Design

At the design stage, the application of LCA methodology enables architects and investors to make informed decisions that enhance the environmental, economic, and social performance of the building. Life cycle analysis allows for the quantification and optimization of resource use, selection of materials with a lower carbon footprint, and the prediction and reduction of future operational costs. The most significant contribution of LCA lies in its ability to identify opportunities for extending the service life of SM, which is crucial for reducing overall environmental impact and increasing economic sustainability.

Results of LCA Methodology in Practice

The ParkLake Shopping Center in Bucharest exemplifies the successful integration of these principles. During the development process, LCA analysis guided the selection of materials, energy solutions, and the optimization of water and waste management systems. The result was a facility with significant reductions in energy and water consumption, and a notably reduced environmental footprint during its operational phase. Such case studies demonstrate that the application of LCA methodology not only minimizes the environmental impact of buildings but also substantially contributes to economic sustainability through resource efficiency and financial savings [

25].

3. Discussion and Results

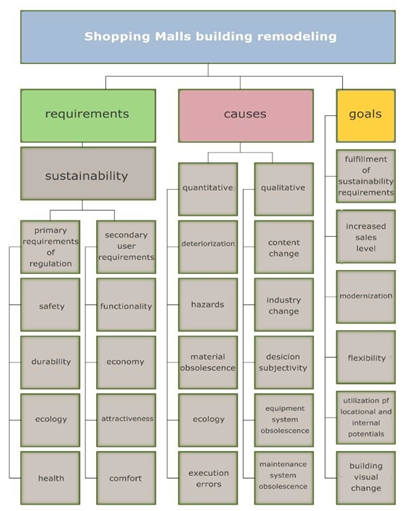

3.1. Basic Research Model- Action of Integrated Design for the Remodeling of SM Buildings - Requirements, Degradation Causes, and Objectives of Sustainable Construction

Integrated design, condition monitoring, and life cycle-based planning are founded on the multiple demands of sustainable construction. The building is regarded as the spatial boundary of the system, while its entire life cycle represents the temporal boundary. The general definition of sustainability is based on time-dependent evaluation across three key dimensions: environmental, economic, and socio-cultural, observed throughout the building’s service life. The socio-cultural dimension encompasses user health and comfort, safety and functionality, as well as cultural values related to traditional construction practices, business culture, lifestyle patterns, architectural styles and trends, and aesthetic quality [

26]

. According to the guidelines [

27] that define methods and processes for sustainable construction, the three core dimensions of sustainability—environmental, economic, and socio-cultural—are extended into a more comprehensive framework of five sustainability qualities. This extension introduces the technical quality, which refers to the performance and durability of building systems, and the process quality, which encompasses aspects of planning, project management, and implementation practices, all evaluated in relation to the contextual characteristics and quality profile of the building site. These expanded dimensions aim to provide a more holistic understanding of sustainability within the life cycle of built structures, reinforcing the integration of performance-based, context-sensitive, and user-centered criteria in architectural and construction practices.

The sustainability requirements of a SM as an architectural entity, in accordance with the principles of integrated design throughout its life cycle, can be grouped into the following key categories: functional quality, durability, aesthetic value, economic viability, environmental performance, and health-related factors. [

28]. The selection between alternative design solutions can be addressed through a multiple-criteria evaluation, leading to the identification of the most advantageous option. All sustainability-related requirements are interdependent and interconnected, forming an inseparable whole—not only during the planning, design, and construction phases of a new building but also throughout its operational life. This integrated system remains valid until the integrity of the established criteria is compromised, at which point a decision is made to initiate remodeling as part of an integrated design strategy.

Monitoring and forecasting the condition of buildings in use is based on the assessment of compliance with multiple sustainability requirements, which are dynamic and evolve over time. These shifting parameters serve as the foundation for selecting optimal strategies among alternative solutions aimed at preserving the integrity of sustainable performance.

In this study, the sustainability requirements, based on a modified framework that expands upon the initial scheme [

28], also include the relevance of safety and comfort, which are particularly important in the context of SM. These additions are reflected in the author’s extended model, as presented in

Table 2. The table also outlines the key sustainability requirements, the causes of degradation, which may trigger the decision to remodel, as well as the objectives underlying such interventions.

The primary goal of remodeling—as a strategy of integrated design in accordance with the building life cycle—is to ensure compliance with sustainability criteria throughout the entire operational period and to enhance sales performance. Particular emphasis is placed on the architectural design process, highlighting its role in improving consumer appeal, comfort, and the overall experience of the shopping environment.

Key redevelopment goals for SM include modernization, spatial flexibility, utilization of location potential, and visual identity transformation. Modernization involves continuous condition monitoring and the replacement of outdated materials and systems to create a contemporary, appealing environment. Consumer stimulation is enhanced through strategic placement of escalators, which provide smooth, uninterrupted vertical circulation, increasing the usability and value of upper floors. Ideally, escalators should be positioned at a distance from the main entrance to encourage unplanned purchases, while ensuring that the walking time remains acceptable for passers-by.

Flexibility refers to the architectural adaptability of the space, enabled by modular skeletal systems and dry assembly techniques. This allows for rapid spatial reconfiguration without the need to modify integrated systems such as lighting, ventilation, or fire protection. Location optimization is achieved through improved accessibility, local competition analysis, and a curated tenant mix targeting specific customer segments.

3.2. Decision-Making DM on the Final Outcome of the Remodeling Action of the Building

The decision to initiate remodeling is made based on an analysis of the causes of sustainability degradation, whether of the entire building or specific components. The study includes the material, spatial, and financial scope of sustainability requirement violations, and proposed interventions are positioned along the building’s service life timeline. The decision-making process is grounded in multi-criteria evaluation, with criteria selected according to the level of compliance with sustainability requirements, as outlined in

Table 2. From an architectural perspective, these criteria can be grouped by significance and similarity. The primary group includes structural integrity criteria, encompassing safety and durability, as well as ecological and health criteria, all of which are directly regulated by technical, environmental, or health standards. The secondary group includes criteria such as functionality, cost-efficiency, and aesthetics, often referred to as "soft" requirements, as they allow for greater tolerance or postponement of fulfillment depending on business operations.

The timing of sustainability degradation plays a key role in decision-making. A breach in any primary requirement at any point during the service life may necessitate immediate closure of the facility, unlike secondary requirements, which may allow continued operation. From an architectural standpoint, the most critical metric within the primary group is the shortest time to failure, defined as the interval between the start of operation and the point when a primary criterion is no longer met.

Material selection can be determined through life cycle analysis of the structure, balancing the durability, mechanical performance, and resistance to aggressive environments, with environmental concerns by choosing materials that have a minimal ecological footprint. At the same time, cost and social criteria—such as thermal comfort, aesthetic value, and construction speed—must be considered. Optimal material selection results from the integration of ecological, economic, and social factors. LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards specify that materials should be renewable, low-energy in production, and low-polluting, with minimal emissions of harmful substances throughout their lifecycle.

The environmental impact of materials spans their entire life cycle—from resource extraction and transportation, to manufacturing, on-site assembly, operation, maintenance, and end-of-life waste management. The production of construction materials and building processes requires significant energy and water consumption, generates large amounts of waste, contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, causes both indoor and outdoor pollution, and leads to the depletion of natural resources. Nearly 3 billion tons of raw materials are consumed annually for building construction. Additionally, energy is expended for the extraction, processing, transport, and assembly of materials. The energy consumption for structural material production can be expressed via a relative energy index, where wood is assigned a baseline value of “1”. Comparative values for concrete, steel, and aluminum are presented in

Table 3.

The emission of harmful gases is represented using a relative carbon dioxide emission index, where the CO₂ emissions from wood production are assigned a baseline interactive value of “1”. The corresponding relative emission values for the production of concrete, steel, and aluminum are presented in

Table 4.

Verification of load-bearing structures is conducted in accordance with current European structural regulations, which encompass the control of the ultimate limit state (ULS), serviceability limit state (SLS), and Gurability Limit State (DLS) during the design, construction, and operational phases of the building.

Durability and Safety Requirement

Research methods addressing durability and safety are based on time-dependent data related to the deterioration and aging of load-bearing structural materials. These approaches rely on mathematical predictive models to assess structural condition over a defined time period.

For newly designed or well-preserved structures with known material properties and geometry, the use of probabilistic safety assessment methods - applied to structural components, materials, and loads - is recommended. These methods are based on stochastic models well-documented in the literature [30]. When evaluating the load-bearing capacity of structures experiencing material and geometric degradation over time, it is necessary to apply stochastic models for assessing the ultimate structural resistance. Structural safety involves verifying both load-bearing capacity and serviceability of the entire system or its individual components.Traditional visual inspection methods, widely used worldwide, are inherently subjective and often unreliable, as their accuracy depends heavily on the experience and expertise of the inspecting engineer. To improve the objectivity and reliability of visual assessments, a series of standardized procedures can be developed. More precise and realistic evaluations of material behavior over time can be obtained through continuous structural health monitoring, particularly using piezoelectric sensors, which provide quantifiable and time-dependent data on structural performance.

3.3. Case Study Results – SM „Deva 1“ Kruševac, Serbia

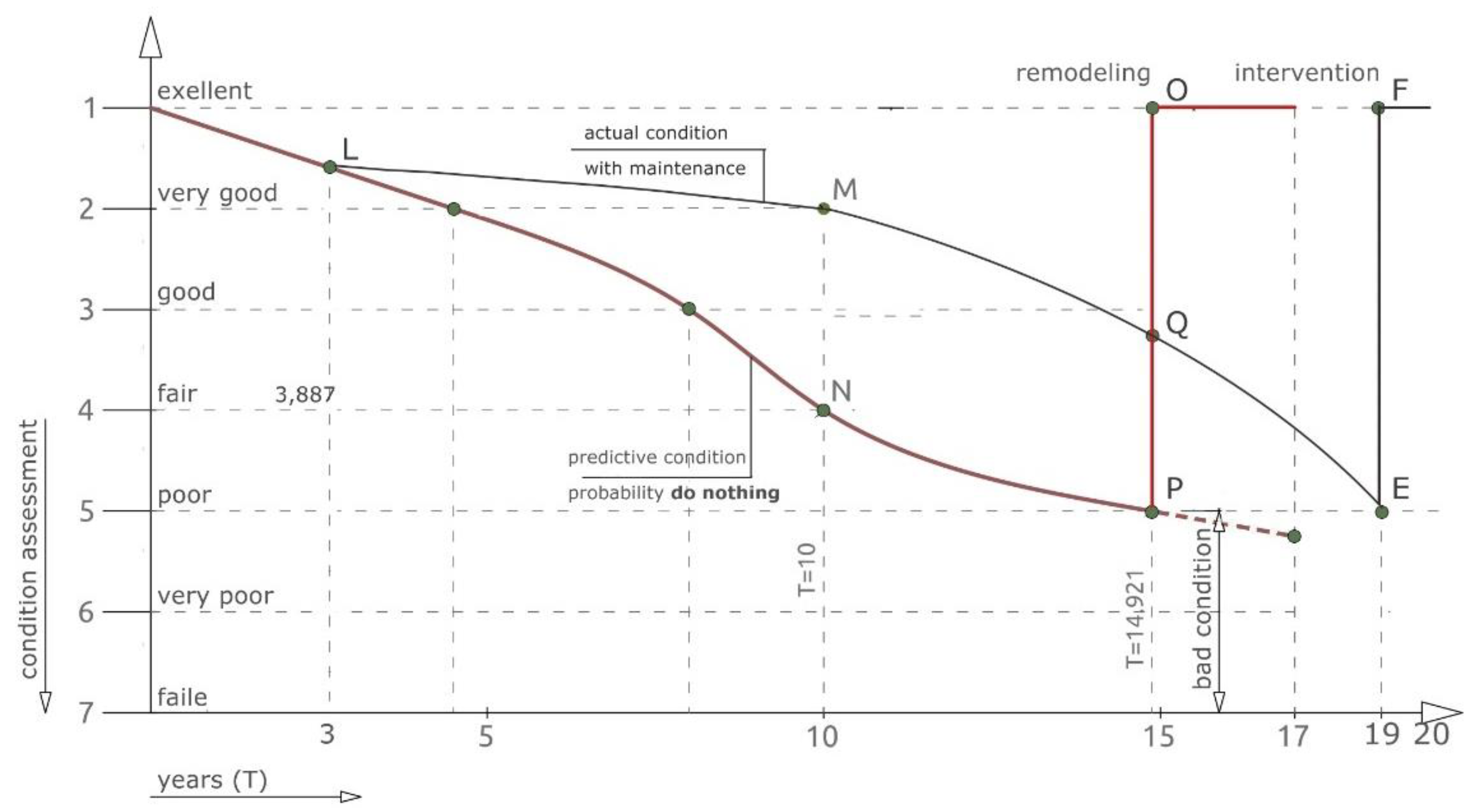

As part of the research on building service life, a case study was conducted on “Shopping Mall DEVA 1” in Kruševac (Serbia), which has been in operation for 20 years following its most recent revitalization. The study included a condition assessment and forecasting over a 19-year observational period. The investigation focused on external façade elements and structural components, and a global condition evaluation was provided based on time-dependent degradation.

The condition classification was performed using the CAS (Condition Assessment Scales) method. A modified version of the CAS methodology was applied, which includes seven clearly defined condition levels. For each level, a rating, qualitative description, and percentage of damage were provided (

Table 5).

The results of the

mathematical condition prediction were obtained using a

Markov model for the

"Do Nothing" (DN) scenario. The transition probabilities between condition states were defined using a 7×7 square probabilistic transition matrix, based on a finite set of available discrete-time condition assessment data. [

2].

The results indicate that, according to the state probability curve (1, L, N, P), the object would have received a condition rating of 3.887 in the 10th year of operation, corresponding to point N on the curve. However, the actual condition at the observed moment was very good (rating 2), represented by point M.

It can be concluded that the positive effect of continuous investment maintenance at T = 10 years is illustrated by the distance NM, indicating a significant improvement compared to the predicted deterioration. The evident discrepancy between the predicted and actual states demonstrates the intention to maintain the “as-new” appearance of the facility.

If the temporal threshold of the system is defined as the moment the structure enters a “poor condition” (rating 5), which marks the end of its technical service life according to the predictive probability, then the calculated technical predictive service life of the object is 14.921 years. This is identified as the point at which remodeling should theoretically be undertaken, resulting in a renewed condition rated as excellent (point OP). At this same time, the actual observed rating was 3.3, represented by point Q.

Figure 6.

Initial and predictive states of building.

Figure 6.

Initial and predictive states of building.

Na At the end of the predictive service life, approximately 15 years, based on the aging-related deterioration and technical condition criteria, the building was assessed to have entered a poor condition. Through remodeling, the facility can be restored either to its original (excellent) condition or to another improved state. The transition from poor condition (point P on the curve) to excellent condition is represented by point O.

Based on monitoring of the actual condition, by year 19, the building reached a poor state (rating 5), which is considered the actual service life under the curve 1, L, M, Q, E, at which point remodeling of the observed building components was proposed.

It is concluded that maintenance activities have a significant impact on extending the service life compared to the predicted trajectory, especially during the first 15 years of operation (point P). However, after this period, due to material aging, the effectiveness of maintenance decreases significantly, as seen at point E in year 19.

4. Conclusions

This study confirms the necessity of an integrated, life-cycle-based approach to the planning, operation, and revitalization of shopping malls. By structuring sustainability requirements across environmental, technical, economic, and socio-cultural dimensions, a comprehensive framework for assessing performance throughout the building’s lifespan has been proposed.

The results emphasize the importance of continuous condition monitoring and timely decision-making in preserving the operational value and extending the service life of commercial buildings. Specific deterioration factors - both quantitative (material aging, regulatory obsolescence) and qualitative (functional program shifts, user needs) - have been identified as triggers for remodeling interventions.

Moreover, architectural flexibility, modular planning, and adaptive management have been shown to significantly improve user comfort, market competitiveness, and overall energy efficiency. The developed model contributes to decision-making strategies for rebranding, repurposing, and technical upgrades of aging retail environments.

The findings suggest that further research should focus on developing quantitative tools to link design interventions with measurable post-revitalization performance indicators, particularly in terms of operational sustainability and user engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T. and V.N.; methodology, J.T. and D.S..; validation, J.T., D.S. and V.N..; formal analysis, J.T. and V.T.; investigation, J.T.; resources, J.T and O.N.; data curation, J.T., D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.T and D.S.; visualization, O.N.; supervision, V.T. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the ministry of science, technological development and innovation of the republic of Serbia, under the agreement on financing the scientific research work of teaching staff at the Faculty of Civil engineering and Architecture, University of Niš - registration number: 451-03-137/2025-03/200095 dated 04/02/2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- T. Schmidtke, “Trend zur Revitalisierung von Shopping-Centern in Deutschland,” Bachelorarbeit, University of Applied sciences, Mittweida, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://monami.hs-mittweida.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/2034/file/Trend_zur_Revitalisierung_von_Shopping_Centern_in_Deutschland.pdf.

- J. Tamburić, “Shopping centers remodeling - the form and the concept of improving Architectural characteristics of buildings,” Doctoral dissertation, University of Niš, Serbia, Faculty of Civil engineering and architecture, 2018.

- L. Spencer, “The Great American Shopping Mall: Past, Present, And Future,” https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/?p=3745.

- K. Kelly, “Global Mall Development Trends,” https://kk.org/extrapolations/global-mall-development-trends/.

- Capital One Shopping team, “Mall Closure Statistics,” https://capitaloneshopping.com/research/mall-closure-statistics.

- J. T. White, A. Orr, and C. Jackson, “Averting dead mall syndrome: De-malling and the future of the purpose-built shopping center in large UK cities,” J. Urban Aff., vol. Volume 47, no. Issue 5, pp. 1523–1539, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Peneder, Reinhard, “The next generation of shopping centres,” SHOP Aktuell 109, pp. 6–13, 2011.

- Živković, Milica, “Defining and Applying the Method for Evaluating the Flexibility of Spatial Organization of the Flat in Multi-Family Residential Buildings,” Doctoral dissertation, University of Niš, Serbia, Faculty of Civil engineering and architecture, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/handle/123456789/9435.

- Lange, Caroline, “Fallstudien zur gebauten Realität in Deutschland- Dissertation,” Doctoral dissertation, Technischen Universität Berlin, Fakultät VI - Planen Bauen Umwelt, Berlin, Germany, 2008.

- Back, Nicolas, “Future Strategies of Shopping Center Investors & Developers in Germany How to Compete with E-Commerce?,” Master, EBS BUSINESS SCHOOL EBS UNIVERSITÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFT UND RECHT & NOVA SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA, Frankfurt, Germany, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/92320/1/Back_2019.pdf.

- Sonae Sierra, “The science of positioning real estate assets to achive full potential,” www.sonaesierra.com. [Online]. Available: https://www.sonaesierra.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/CS-The-science-of-positioning-FV.pdf.

- GMA, Beratung und Umsetzung, “Sonae Sierra and Center Erfolgs-Check method- Shopingcenter Revitilisierung Deutschland,” www.gma.biz.

- Reikli, Melinda, “Composing Elements of Shopping Centers and their Strategic Fit,” Doctoral dissertation, CORVINUS UNIVERSITY OF BUDAPEST, Hangury, 2012.

- Weis, Hans Christian, Marketing- Kompendium der praktischen Betriebswirtschaft, 16th, Improved and Updated ed. Kiehl, Germany: NWB Verlag, 2012.

- Ziercke, Christoph, “Strategien zur Revitalisierung von Shopping-Centern,” Graduete thesis, Hamburg, Germany, 2003.

- Wood Works, “Introduction to Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment: The Basics,” www.woodworks.org. [Online]. Available: https://www.woodworks.org/wp-content/uploads/expert-tips/expert-tips_introduction-to-whole-building-life-cycle-assessment-the-basics.pdf.

- Parasonis, Josifas et al., “Building Life Cycle,” in Longlife 2. Development of standards, criteria, specifications, economical and financial models, assessment of sustainability, life cycle and operating costs, Berlin, Germany: Universitätsverlag der TU Berlin, 2010.

- Stromeyer André, “REVITALIZATION AND ASSESSMENT OF RETAIL REAL ESTATE: CASE STUDY OF RATHAUS GALERIE ESSEN,” www.across-magazine.com. [Online]. Available: https://www.across-magazine.com/revitalization-and-assessment-of-retail-real-estate-case-study-of-rathaus-galerie-essen/.

- Urbano, Ecosistema, “Reinvention through design,” ArchDaily, Dec. 29, 2017.

- Pilgreen, Todd; Plenge, Annmarie, “REINVENTING THE MALL Developers are transforming struggling malls into thriving urban lifestyle centers.,” www.gensler.com. [Online]. Available: https://www.gensler.com/dialogue/35/reinventing-the-mall.

- Таmburić, Јasmina; Stojić, Dragoslav; Nikolić, Vladan, “Service life and durability of architectonic structures,” FACTA Univ. Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng., vol. 14, no. NO. 3, pp. 275–284, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, Saman; Slob, Niel (Cornelis), “Flexibility as foundation of Sustainability,” Draaijer + Partners, TU Delft, Faculty of Architecture, Delft, Netherland, 2010.

- Ritter, Frank, “Lebensdauer von Bauteilen und Bauelementen- Modellierung und praxisnahe Prognose,” Doctoral dissertation, Technische Universität Darmstadt Institut Für Massivbau, Darmstadt, Germany, 2011.

- Kalusche, Wolfdietrich, “Technische Lebensdauer von Bauteilen und wirtschaftliche Nutzungsdauer eines Gebäudes,” in Bauen, Bewirtschaften, Erneuern - Gedanken zur Gestaltung der Infrastruktu, vdf Hochschulverlag an der ETH Zürich, Zürich, 2004, pp. 55–71.

- Sonae Sierra, “ParkLake: Putting sustainability at the heart of the shopping centre,” www.sonaesierra.com. [Online]. Available: https://www.sonaesierra.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ParkLake_Putting_sustainability_at_the_heart_of_-the_shopping_centre.pdf#:~:text=.

- Sarja, AskoI, “Generalised lifetime limit state design of structures,” presented at the Second International Conference on Lifetime-Oriented Design Concept, Bochum, Germany: Ruhr-Universität, Department of Civil Engineering, SFB 398, 2004.

- BMVBS, “Zukunftsfähiges Planen, Bauen und Betreiben von Gebäuden,” Leitf. Nachhalt. Bau. -Bundesminist. Für Verk. Bau Stadtentwickl. BMVBS, 2015.

- Sarja, AskoI, “Integrated Life Cicle Design of Material And Structural Design,” presented at the ILCDES 2000 RILEM, Helsinki: AFCE, 2000.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).