1. Introduction

Corporate bankruptcy represents a critical event with profound economic and social repercussions. This phenomenon impacts not only business owners and employees but also commercial partners, investors, and the broader financial ecosystem [

11]. In the contemporary economic landscape characterized by heightened volatility, unpredictability, and competition, the capacity to foresee corporate financial turmoil has emerged as a crucial strategic necessity. Early detection of warning signals enables stakeholders to implement proactive risk mitigation measures, reallocate resources, and potentially prevent economic collapse [

22]. This pressing need has driven growing interest in developing sophisticated bankruptcy prediction models that combine analytical rigor with computational power [

1]. Traditional bankruptcy prediction studies relied on classical statistical methods such as linear discriminant analysis, logistic regression, and financial scoring models like Altman’s (1968) Z-score [

12]. Although these methodologies have substantially enhanced our comprehension of failure mechanisms, they also exhibit numerous constraints. Most notably, their capacity to capture complex nonlinear relationships between explanatory variables and bankruptcy probability is constrained. Furthermore, they typically impose strict assumptions about data normality and variable independence that are rarely satisfied in real-world financial data [

31].

The advent of machine learning (ML) methodologies has proffered optimistic solutions to surmount these constraints. ML offers more flexible, adaptive, and powerful tools for modeling the inherent complexity of economic phenomena [

2]. Unlike statistical approaches, ML algorithms impose no a priori functional form on variable relationships, enabling them to capture complex interactions and nonlinear effects prevalent in financial data [

26]. Popular methods in this domain include Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and ensemble techniques like gradient boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) [

36] ML’s advantages for bankruptcy prediction include its ability to [

8]

Process heterogeneous datasets

Handle missing or noisy variables

Adapt to high-dimensional data structures

Learn from vast historical observation sets to generate robust predictions

However, these approaches also present challenges:

Significant data preprocessing requirements

Reduced interpretability compared to traditional models

Performance sensitivity to hyperparameter selection

Computational complexity in some implementations

In light of the proliferation of extensive datasets and refined computational technologies, deep learning (DL) strategies have garnered considerable attention in the area of financial forecasting. As a subset of ML, DL employs deep neural architectures capable of automatically extracting hierarchical representations from raw data. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and specialized variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have demonstrated effectiveness across diverse applications, including financial and economic forecasting [

35]. In bankruptcy prediction, DL architectures achieve high performance by [

2]

Precisely modeling temporal sequences in financial data

Capturing complex nonlinear interactions

Leveraging massive datasets for improved generalization

LSTM networks are particularly well-suited for financial time series analysis due to their ability to capture long-term dependencies

CNNs have proven effective for extracting discriminative features from transformed financial ratio matrices or tabular representations

Despite their predictive power, DL techniques face criticism regarding:

High computational complexity and resource requirements

"Black box" nature that reduces interpretability

Difficulty justifying predictions for critical applications like credit assessment

Model performance fundamentally relies on data quality. The availability, accuracy, frequency, and granularity of financial information significantly impact predictive system effectiveness. Traditional accounting data, while informative, may insufficiently capture a company’s true financial health dynamics. Emerging research explores integrating alternative data sources (e.g., annual reports, economic news, social media signals) to enrich model training.

A critical additional challenge is class imbalance - a common issue in bankruptcy datasets where non-bankrupt firms vastly outnumber bankrupt ones. Technically, a dataset is considered imbalanced when there exists significant (or extreme) disproportion between class representations. Standard ML algorithms typically exhibit bias toward the majority class because [

4]: Rules correctly predicting majority instances receive positive weighting in accuracy metrics

Minority class prediction rules may be treated as noise

Minority instances are consequently misclassified more frequently

The principal contributions delineated within this article may be encapsulated as follows:

We propose a comprehensive framework of the Fuzzy Support Vector Machine (Fuzzy SVM) using a diverse range of membership functions, including geometric, density-based, and entropy-driven approaches, to quantify the uncertainty of individual samples and enhance model robustness in imbalanced data scenarios.

We extend the Rough Support Vector Machine (Rough SVM) paradigm by integrating multiple weighting strategies that reflect the granularity of lower and upper approximations, enabling the model to better capture data ambiguity and improve classification performance.

We introduce a novel Shadowed Support Vector Machine (Shadowed SVM) approach that employs a Multi-Metric Fusion mechanism to define shadow regions near the decision boundary. This is achieved through a combination of geometric distances and margin-based metrics, followed by shadowed combination to control the influence of uncertain instances.

We develop a Quotient Space Support Vector Machine (QS SVM) model that utilizes a Quotient Space Generator per class. This mechanism delineates the input space into localized regions by employing clustering algorithms, including K-Means or DBSCAN, thus facilitating the model’s ability to develop classifiers that are specific to each region and to accommodate the variations inherent in local data distributions.

We empirically observe that Fuzzy SVM excels in achieving high overall accuracy, while the Shadowed SVM provides superior performance in handling data imbalance. Motivated by these complementary strengths, we propose a novel hybrid model—Fuzzy Shadowed Support Vector Machine (Fuzzy Shadowed SVM)—which combines fuzzy membership weighting with shadowed instance discounting to achieve both high accuracy and class balance.

The subsequent sections of this manuscript are organized as delineated below:

Section 2 offers an extensive examination of the existing literature pertinent to the prediction of bankruptcy.

Section 3 discusses the concept of granular computing, particularly fuzzy sets, rough sets, shadowed sets, and quotient space theory.

Section 4 offers a concise overview of the proposed granular Support Vector Machine approach .

Section 5 delineates the empirical findings and their subsequent examination, whereas Section 7 articulates the ramifications of the results, delineates prospective avenues for further investigation, and encapsulates the principal contributions and outcomes of this scholarly endeavor.

2. Literature Review

Corporate bankruptcy prediction has long represented a critical challenge in quantitative finance and risk management. Identifying early warning signals enables financial loss anticipation, credit risk assessment, investment optimization, and economic policy guidance. As available data grows in volume and variety, traditional methods face inherent limitations, while machine learning (ML)[

23] and deep learning (DL) [

35] techniques emerge as powerful adaptive alternatives.

However, applying these techniques to bankruptcy prediction encounters a persistent structural obstacle: class imbalance in datasets. Bankrupt firms typically constitute a tiny minority (often <5%, sometimes <1%) in real-world databases. This disparity between the majority class (solvent firms) and minority class (bankrupt firms) fundamentally challenges effective predictive model development [

6].

Early bankruptcy prediction research was dominated by statistical models like linear discriminant analysis (Altman 1968), logistic regression (Ohlson 1980), and financial scoring models (Z-score, O-score) [

29]. While robust, these exhibit critical limitations with imbalanced data: their parametric nature imposes strict distributional assumptions (normality, variable independence) rarely satisfied empirically, and their symmetric cost functions minimize overall error without distinguishing minority-class misclassification impacts - precisely the class of interest.

Consequently, while such models achieve high accuracy rates, they frequently demonstrate poor sensitivity (recall) for bankrupt firms, yielding excessive false negatives - a critical error in risk management contexts. For instance, in datasets with only 3% bankrupt firms, a trivial "always solvent" classifier achieves 97% accuracy while failing completely at bankruptcy detection.

To address this imbalance, researchers initially explored data-level rebalancing techniques before model training, primarily:

Machine learning algorithms have attained extensive utilization in contemporary bankruptcy research owing to their ability to elucidate nonlinear interdependencies, manage diverse data types, and enhance the generalizability of predictive models. Prominent approaches include( [

26,

27]

Random Forests: Bootstrap-aggregated decision trees robust to noise and correlations

Support Vector Machines (SVM): Margin-maximizing classifiers in transformed spaces

Decision Trees (CART, C4.5): Interpretable rule-based models

Boosting algorithms (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost): Ensemble methods combining weak learners

To counter class dominance effects, key strategies include:

Cost-sensitive learning: Algorithms like XGBoost permit class weighting (scale pos-weight) to penalize minority-class errors

Integrated sampling: Techniques like Balanced Random Forest perform per-iteration resampling

Alternative metrics: F1-score, AUC-PR, G-mean, or Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) better evaluate imbalanced contexts [

37].

Empirical studies confirm these approaches, combined with judicious data rebalancing, improve overall performance while maintaining bankruptcy detection capability ( [

10,

33]).

DL methods have rapidly expanded in financial applications due to automated feature extraction capabilities. Research has shown that Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

9] work effectively for predicting bankruptcies [

16]. These methodologies also demonstrate considerable efficacy when integrated with alternative techniques, including Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs/LSTMs) [

17] and diverse configurations of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [

14].

However, with severe class imbalance, these models become prone to majority-class overfitting, particularly when bankruptcies are extremely underrepresented. Additionally, their massive data requirements complicate application in low-default portfolios. Mitigation strategies include:

Weighted loss functions: Modifying binary cross-entropy with class-frequency weights or adopting focal loss [

30] to emphasize hard samples

Balanced batch training: Curating mini-batches with controlled class proportions [

20]

Temporal data augmentation: For LSTM/GRU models, generating synthetic sequences via dynamic time warping or Gaussian perturbation [

18]

A critical adoption barrier for complex models - especially in finance - remains interpretability. Deep neural networks often function as "black boxes", providing accurate predictions without decision transparency. Post-hoc explanation tools like LIME [

21] and SHAP [

34] address this by quantifying variable importance for individual predictions, even on rare cases. Alternative approaches embed interpretability directly into model architectures through neural-rule hybrids or accounting-informed filtering layers. Toward Hybrid and Multimodal Approaches:

Data-level rebalancing (SMOTE, ADASYN)

DL representation power

Secondary classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) for refined decisions

Innovations include incorporating textual data (financial reports, news) via NLP models and behavioral indicators. Here’s a more humanized version of your text:

For example, Zhang et al. [

32] integrate an autoencoder to detect anomalies in financial ratios, an LSTM network for capturing sequential patterns, and SHAP explanations to support human interpretation. Building on this, Wang and colleagues [

25] show that using CNN-LSTM models trained on SMOTE-generated synthetic data can substantially improve prediction accuracy, boosting both F1-scores and recall rates.

ML/DL-based bankruptcy prediction constitutes a rapidly evolving field constrained by inherent class imbalance. This structural data characteristic biases conventional models, necessitating specialized data treatments and algorithmic adaptations. While oversampling, cost-sensitive learning, weighted loss functions, and hybrid approaches demonstrate effectiveness, the field must still reconcile predictive performance with stability, generalizability, and interpretability - particularly in regulated finance, banking, and auditing contexts.

3. Granular Computing

Granular computing elucidates the manner in which granular reasoning may be utilized to forecast corporate insolvency. For instance, artificial neural networks—with fuzzy concept such as those referenced by Jabeur et al. [

40] are used to sort and classify a wide range of economic data while accounting for the diverse behaviors of various economic agents. A well-orchestrated training process enables these models to uncover, sometimes in unexpected ways, hidden structures within highly complex datasets, thereby making it easier to detect early warning signals of financial distress. Borowska et al. [

15] have advocated for an updated version of the rough–granular approach (RGA), aiming to improve the classification performance on bankruptcy data. Granular computing focuses on multi-level data processing—an emerging domain that already shows significant promise. It involves organizing information in a hierarchical manner, which proves particularly useful for analyzing complex systems such as corporate bankruptcy prediction. Typically, the use of multiple datasets enriches predictive models.

In the long term, the goal is to improve decision-making processes and risk assessment strategies within the financial sector. By developing more accurate predictive models, stakeholders can better identify at-risk firms, enabling timely interventions and fostering a more resilient financial environment.

Support Vector Machine (SVM) has emerged as a preeminent classification methodology in the domain of bankruptcy prediction, attributable to its robust theoretical underpinnings and its capacity to delineate an optimal hyperplane that maximizes the separation between distinct classes. Its efficacy is especially pronounced in high-dimensional parameter spaces, wherein SVM adeptly differentiates between solvent and bankrupt enterprises by employing kernel functions that elucidate non-linear relationships within financial metrics. Furthermore, SVM demonstrates commendable generalization capabilities even when confronted with sparse training datasets, a phenomenon frequently encountered in financial analytics. Nevertheless, notwithstanding its advantages, SVM is confronted with a substantial limitation when deployed in the context of imbalanced datasets, a prevalent feature of bankruptcy forecasting wherein non-bankrupt entities vastly outnumber their bankrupt counterparts. In such instances, the conventional SVM exhibits a propensity to favor the majority class, resulting in inadequate identification of the minority class (i.e., bankrupt firms). This bias arises from the margin-based optimization paradigm, which fails to explicitly account for class distribution. Consequently, the classifier may attain a high overall accuracy yet inadequately recognize instances of financial distress, thereby undermining its practical applicability in the realm of real-world bankruptcy prediction.

To address the challenges posed by imbalanced datasets in bankruptcy prediction, numerous techniques grounded in Granular Computing (GrC) have been proposed. Granular computing provides a powerful paradigm for processing complex and uncertain information by decomposing data into meaningful granules. In this context, several researchers have explored granular-based strategies to enhance data representation and learning performance. Among these, the work of Shuyin Xia et al. [

3] introduced the concept of granular-ball computing within the framework of fuzzy sets, aiming to improve the preprocessing phase of imbalanced classification. The authors proposed a novel fuzzy set model where the data space is adaptively covered using a set of hyperspheres (granular-balls), each representing a localized region of the input space. These hyperspheres are generated based on the distribution of the data, and the boundary points of the balls serve as representative sampled data. This approach effectively reduces data redundancy while preserving critical structural information, thereby enhancing the learning process in fuzzy environments. The granular-ball model offers a promising direction for mitigating the impact of class imbalance by enabling more balanced data distribution through adaptive sampling and localized granulation.

In conjunction with granular-ball computing, numerous alternative granular computing paradigms have been formulated to mitigate data imbalance through the alteration of either the data distribution or the intrinsic learning mechanism. Granular Support Vector Machines (GSVM) represent a notable example, where the input space is divided into granular regions, each associated with specific levels of uncertainty or importance. This decomposition facilitates the design of more robust classifiers by emphasizing the minority class during training, thus improving sensitivity and generalization.

Moreover, granular computing has been effectively amalgamated with additional soft computing frameworks, including rough sets and fuzzy sets [

5,

13,

24,

38,

39]. For instance, hybrid models that combine fuzzy set theory with granular principles enable the construction of fuzzy partitions that are sensitive to local imbalances. These partitions can adaptively reflect the underlying data distribution, which is especially critical in domains such as bankruptcy prediction, where misclassifying a minority instance can have significant financial implications A representative approach in this direction is the work of Ibrahim, H et al. [

13], who proposed a Rough Granular SVM (RG-SVM) that incorporates rough approximations into the granular structure of the input space. The model leverages lower and upper approximations to deal with boundary uncertainty, allowing the classifier to differentiate more effectively between borderline and well-defined instances. This technique not only improves classification accuracy but also enhances the interpretability of the decision regions.

3.1. Fuzzy Sets

The fuzzy set methodology, initially proposed by Lotfi A. Zadeh in the year 1965, constitutes a pivotal extension of traditional set theory. It enables the modeling of vagueness and uncertainty intrinsic to many complex systems, including engineering, artificial intelligence, economics, and social sciences.

In traditional set theory (often called crisp sets), membership is black and white - an element either fully belongs to a set or doesn’t belong at all, with no middle ground. In other words, for any element

x in the universe

U, the membership function

of a set

A takes values exclusively in {0, 1}:

This binary framework demonstrates efficacy for distinctly defined parameters (e.g., “Is it an even integer?”, “Is he/she a citizen of the state?”); however, it is insufficient for the representation of ambiguous or continuous constructs such as “tallness,” “youthfulness,” “riskiness,” or “low socioeconomic status.”

Fuzzy set theory offers a more flexible framework that corresponds with the elusive nature of human communication and the complexities of the empirical realm. A fuzzy set over a universe X is defined by a membership function , which assigns to each element a membership degree ranging from 0 to 1.

For example, in a fuzzy set , one might have:

This implies that 1.80 m is somewhat tall, 1.90 m is very tall, and 2.00 m is fully tall.

Key characteristics of fuzzy sets include:

Membership Function: The core of fuzzy logic, which can take various shapes (triangular, trapezoidal, Gaussian, sigmoidal), chosen according to interpretative or modeling needs.

Support: The set of elements where , indicating the domain of influence.

Core: The set of elements where , representing full membership.

Height: The maximum value of ; the set is normalized if the height equals 1.

Fuzzy operations generalize classical set operations:

Union:

Intersection:

Complement:

Advanced operators such as t-norms and t-conorms allow for more refined conjunctions and disjunctions.

The utility of fuzzy sets lies in their ability to incorporate approximate reasoning into computational systems. For example, in an intelligent driving system, rules like:

“If speed is high and visibility is low, then decelerate sharply”

are based on subjective concepts that fuzzy sets represent effectively.

Applications encompass:

Fuzzy control mechanisms (e.g., thermal regulation, self-operating vehicles)

Multi-criteria decision analysis under conditions of uncertainty (fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process, fuzzy Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution)

Medical diagnostics involving indistinct symptoms

Fuzzy data examination and clustering methodologies (e.g., fuzzy c-means algorithm)

Risk assessment and behavioral finance considerations

Expert systems and symbolic artificial intelligence

Despite their advantages, fuzzy sets have limitations:

Subjectivity in choosing membership functions

Difficulty in aggregating a large number of fuzzy rules

Increasing computational complexity in large-scale systems

Unsuitability for random uncertainties (where probability theory is more appropriate)

Extensions encompass:

Type-2 Fuzzy Sets (characterized by uncertainty pertaining to the membership function itself)

Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets (which incorporate a quantifiable measure of non-membership)

Rough Sets (which are pertinent within contexts reliant on granularity)

Fuzzy set theory represents a significant conceptual evolution in the representation of imprecise phenomena. By diverging from rigid binary logic, it facilitates the development of models that more accurately reflect human cognitive processes, exhibit enhanced flexibility, and are better aligned with the ambiguity that characterizes real-world scenarios. Its incorporation into hybrid frameworks (neuro-fuzzy systems, fuzzy expert systems, extended fuzzy logics) perpetually expands its relevance across the domains of artificial intelligence, engineering, economics, and beyond.

3.2. Rough Sets

The conceptual framework of rough set theory, pioneered by Zdzisław Pawlak in 1982, offers a rigorous mathematical structure for the representation of uncertainty, imprecision, and deficiencies in information within data systems. Unlike probability theory or fuzzy sets, rough sets rely on the concept of indiscernibility: when an object’s membership in a set cannot be determined precisely, upper and lower approximations are used to bound the set. In many real-world contexts—such as machine learning, classification, data mining, and knowledge discovery—available data is incomplete or imprecise, preventing a sharp partitioning of objects. Rough set theory enables reasoning based on approximations by leveraging the indiscernibility relation among observed objects.

The foundation of this study is an information system conceptualized as a table representation. , where:

Each attribute is a function , where is the value domain of f.

are indiscernible with respect to a subset

if they share identical attribute values over

C. This induces an equivalence relation:

This equivalence relation partitions U into equivalence classes known as information granules. Given , the lower and upper approximations are defined as:

Lower approximation

: the set of objects that certainly belong to

X, i.e., those whose equivalence classes are fully contained within

X:

Upper approximation

: the set of objects that possibly belong to

X, i.e., those whose equivalence classes intersect with

X:

The rough boundary of

X is:

It consists of objects for which membership is uncertain. A set is exact if its boundary is empty (); otherwise, it is rough.

The precision of the approximation is measured by:

This ratio, in , quantifies the confidence in the approximation.

Rough set theory also facilitates attribute reduction and dependence analysis:

Applications of rough sets include:

Feature selection and dimensionality reduction

Interpretable decision rule generation

Analysis of incomplete or imprecise data

Multi-criteria decision analysis

Bioinformatics, finance (bankruptcy prediction), healthcare (diagnosis)

Rough set theory is frequently integrated with alternative models (such as fuzzy sets and neural networks) to create sophisticated hybrid frameworks. It is especially effective with discrete data; continuous data must usually be discretized. It is sensitive to data quality and may require preprocessing for large datasets due to the computational cost of reduct calculation.

Overall, rough set theory offers a robust framework for modeling indiscernibility-based uncertainty, complementing probabilistic and fuzzy methods—especially when prior knowledge on membership degrees is lacking

3.3. Shadowed Sets

The conceptual framework of shadowed sets, as delineated by Wang et al. (1992), serves to augment the traditional fuzzy set theory initially articulated by Zadeh (1965). It was developed to address specific limitations of fuzzy sets, particularly the interpretability of membership degrees close to 0.5. Shadowed sets simplify fuzzy representations by offering a three-valued approximation: a definite inclusion, a definite exclusion, and an indeterminate or shadowed region, which captures uncertainty or vagueness In fuzzy modeling, each element x in a universe X is associated with a membership degree . Nevertheless, membership values that approach the median (e.g., ) may present challenges in the interpretation within the framework of decision-making processes. For instance, if , should the element be considered a member of the set or not? This ambiguity can hinder effective decisions in expert systems, classification tasks, or reasoning under uncertainty To overcome this issue, shadowed sets replace the continuum of fuzzy membership values with a three-level approximation:

⇒ the element clearly belongs to the set;

⇒ the element clearly does not belong to the set;

⇒ the element lies in a shadowed region, indicating indeterminacy.

Let A be a fuzzy set over X with membership function . The corresponding shadowed set is constructed using two thresholds and , where . The universe is then partitioned into three distinct regions:

Positive region (membership 1): if , then ;

Negative region (membership 0): if , then ;

Shadowed region (indeterminate): if , then is undefined or remains within .

Illustrative example in fuzzy classification:

Patient A: ⇒ classified as ill;

Patient B: ⇒ classified as healthy;

Patient C: ⇒ classification is indeterminate.

Assuming

and

, the interpretation is as follows:

Optimal threshold determination: Wang proposed an optimization-based approach to determine the ideal values of

and

by minimizing the total approximation error:

The goal is to find

and

(with

) that minimize

, thereby maximizing the transfer of ambiguity into the shadowed region while retaining interpretive clarity in the crisp regions.

3.4. Quotient Space Theory

Quotient Space Theory (QST), as delineated by Zhang et al. (2004), presents a systematic approach for the representation of human cognition, positing that this cognition is intrinsically situated, ambiguous, and structured in a hierarchical manner. This theoretical framework is grounded in the mathematical concept of quotient space, a construct frequently employed in topology and abstract algebra, to elucidate the granularity and complexity of information representation Let

X be a set representing an information space, and let

R be an equivalence relation on

X. The relation

R partitions

X into equivalence classes

, each representing an information granule The set of all equivalence classes forms the quotient space:

A quotient space is formally defined as a triplet:

where:

X is the original information space,

R is an equivalence relation on X,

f is a function defined on the equivalence classes of R.

QST is founded on two fundamental cognitive principles:

Cognitive partiality: human perception is inherently local and approximate,

Local processing: reasoning is performed within subspaces of the global problem.

These principles justify the construction of a hierarchy of successive quotient spaces, each representing a distinct level of abstraction.

QST introduces a hierarchical tree structure:

the root node represents the global space,

lower levels denote finer abstractions,

child nodes refine the representations of their parents.

In machine learning, each class can be interpreted as a quotient space. QST facilitates:

dimensionality reduction,

reasoning over aggregated representations,

robustness against uncertain or noisy data.

Two fundamental stages are involved:

Construction of a quotient space: selecting relevant attributes and defining R,

Reasoning and prediction: operating within a simplified space, and refining representations when uncertainty arises.

Imbalanced data is characterized by the underrepresentation of one or more classes, leading to:

model bias toward the majority class,

low recall on the minority class,

limited generalization capabilities.

QST enables:

intelligent grouping of data samples,

localized treatment of the minority class,

adaptive granularity tailored to rarity.

A Support Vector Machine (SVM) delineates distinct classes by optimizing the separation margin that exists between them. In imbalanced contexts, support vectors from the minority class are often insufficient.

The integration procedure encompasses the subsequent stages:

Pre-granulation employing QST,

Structured resampling predicated on granule characteristics,

SVM training utilizing balanced granules,

Hierarchical prediction facilitated through a QS Tree framework.

QST facilitates a hierarchical and granular depiction of complexity and uncertainty. When amalgamated with SVM in contexts characterized by imbalanced learning, it markedly improves classification efficacy—particularly for minority classes—while maintaining the integrity of the overarching model architecture. In other words, the integration of QST promotes:

enhances recall for the minority class,

mitigates tendencies toward overfitting,

promotes adaptable and localized decision-making.

4. Granular Support Vector Machines: Proposed Approach

Support Vector Machines (SVM) constitute a formidable approach for tackling classification issues; nevertheless, this conceptual paradigm is not devoid of its drawbacks. Each training instance is assumed to belong exclusively to one of the two defined classes. Clearly, within the SVM paradigm, all training instances relevant to a specific class are treated uniformly The technology of Support Vector Machines has garnered increasing attention within the machine learning community (as evidenced by the vast volume of publications dedicated to SVM) Support Vector Machines (SVM) are based on the principle of Structural Risk Minimization (SRM), which aims to balance model complexity and training error in order to improve generalization performance. . In numerous applications, SVMs have demonstrated superior performance compared to classical learning methods and are now regarded as powerful tools for tackling classification problems SVM involves two main stages: first, it maps input data points into a high-dimensional feature space; then, it seeks to identify a separating hyperplane that optimally maximizes the margin between the two classes within this transformed space. The process of maximizing the margin is formulated as a quadratic programming (QP) problem, which can be efficiently solved by addressing its dual form via Lagrange multipliers Without requiring explicit knowledge of the projection function, the SVM skillfully determines the optimal hyperplane using inner product functions in the feature space, known as kernels. The resulting solution can be expressed as a linear combination of a limited subset of input data points, referred to as support vectors SVM-based methodologies are increasingly adopted across a wide range of disciplines. Notwithstanding, in certain applications, it is not feasible to unequivocally categorize all data points into one of the two delineated classifications. Certain instances are critical and require strict classification to ensure proper separation. Conversely, other data points—possibly affected by noise—are less significant, and it would be advantageous for the model to disregard them Formally, an SVM can be defined as follows:

Let S denote a dataset with training instances , where and .

In numerous instances, the endeavor to directly ascertain a hyperplane within the input space is found to be unduly limiting for effective practical application. A potential solution to this constraint involves projecting the input space into a higher-dimensional feature space and then seeking the optimal hyperplane in this modified environment Support Vector Machines, introduced by Vapnik [

7], are a supervised learning method rooted in statistical learning theory. Their primary goal is to determine an optimal decision boundary—called the

separating hyperplane—that maximizes the margin between different classes. This methodology, founded upon the principles of convex optimization and kernel theory, is characterized by its resilience and capacity for generalization, even within the confines of high-dimensional spaces.

Let a training set be given by

, where

represents a feature vector and

denotes its label. The optimization problem for a linear SVM is formulated as:

where

w is the weight vector orthogonal to the hyperplane, and

b is the bias. The optimal solution

defines the separating hyperplane

, with a margin of

.

When data are not linearly separable, SVMs employ a kernel function to map the data into a higher-dimensional space where linear separation becomes feasible. Common kernels include:

Gaussian Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel:

Polynomial Kernel:

For problems involving noise or class overlap, a

soft-margin formulation introduces slack variables

, leading to the optimization problem:

where

C controls the trade-off between margin maximization and tolerance for misclassification SVMs are widely applied in pattern recognition, text classification, and bioinformatics, due to:

Their resistance to overfitting

Their flexibility through kernel selection

Their effectiveness in high-dimensional spaces

Challenges include hyperparameter tuning (e.g., selecting C and the appropriate kernel), and computational complexity when handling large-scale datasets. Variants including multi-class Support Vector Machines (for instance, one-versus-all methodologies) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) enhance the applicability of the Support Vector Machine paradigm to a more extensive array of challenges. The classical Support Vector Machine (SVM) framework lacks an inherent mechanism to handle the varying importance or informativeness of individual training instances. This limitation becomes critical in scenarios where data quality or relevance differs across the dataset. In many classification tasks, certain examples carry greater significance or provide more valuable information than others. Consequently, it is desirable to achieve high accuracy on these key instances while allowing for some misclassification of noisy or less relevant samples.

Put simply, a training instance should not be strictly assigned to a single class. For instance, an example might belong to a class with 90% confidence and have 10% ambiguity, or alternatively, it may show 20% association with one class and 80% non-relevance. Hence, each sample can be attributed a fuzzy membership degree, which quantifies the level of confidence or affiliation of the instance to a class. The complementary degree indicates the irrelevance or insignificance of the sample in the decision process.

Building on this foundation, we propose enhancing the standard Support Vector Machine (SVM) by incorporating fuzzy membership values—resulting in a more flexible Fuzzy Support Vector Machine (FSVM) model.

Bankruptcy prediction is a crucial financial task aimed at forecasting firms likely to encounter financial distress. A significant challenge arises from the class imbalance inherent in such data: bankrupt firms are far fewer than healthy ones. This imbalance biases classical supervised models, including SVM, towards the majority class.

To tackle these complexities, we propose an advanced augmentation of the conventional Support Vector Machine (SVM) paradigm, designated as the Granular Support Vector Machine (GSVM). This methodology amalgamates various granular computing methodologies, encompassing:

Fuzzy Support Vector Machine (Fuzzy SVM),

Rough Support Vector Machine (Rough SVM),

Shadowed Support Vector Machine (Shadowed SVM),

Quotient Space Support Vector Machine (QS SVM),

Fuzzy Shadowed Support Vector Machine (Fuzzy Shadowed SVM).

These approaches aim to better capture the uncertainty, ambiguity, imprecision, and cognitive granularity typically present in noisy or incomplete financial datasets.

This work presents the theoretical foundations, implementation details, and application of each approach in the context of bankruptcy prediction.

Specifically, the Fuzzy SVM assigns fuzzy membership values to training points, reflecting their reliability and handling uncertainty or label noise.

In bankruptcy datasets, some firms exhibit intermediate financial indicators, being neither clearly healthy nor definitively risky. FSVM mitigates the influence of such ambiguous instances by assigning lower weights during optimization, thereby:

Reducing the impact of outliers,

Emphasizing firms on the brink of bankruptcy,

Attenuating bias towards the majority class.

Based on Pawlak’s Rough Set Theory, Rough SVM decomposes the set of companies into three regions:

The positive region (certainly bankrupt or non-bankrupt),

The negative region (certainly not bankrupt or bankrupt),

The boundary region (uncertain).

Rough SVM treats these regions differently within the cost function, assigning varying importance levels based on certainty. This is particularly useful for classifying companies with conflicting or vague features.

Shadowed SVM leverages the concept of shadowed sets, which simplify fuzzy sets using three discrete values: 0, 1, and uncertain. This allows the model to identify a shadowed region in the feature space where companies are difficult to classify.

This mechanism:

Creates a fuzzy boundary between classes,

Enhances the detection of critical regions,

Reduces the influence of weakly informative examples.

Quotient Space Theory enables the modeling of cognitive granularity by introducing abstraction levels over the data. QSSVM learns to classify firms across different quotient spaces defined by aggregated or specific financial attributes (e.g., liquidity and solvency ratios).

This approach:

Structures data according to equivalence relations,

Enables hierarchical classification,

Enhances robustness against local variations.

This model merges fuzzy approximation of instances and rough delineation of class regions. It offers a joint modeling of imprecision and structural uncertainty in financial data.

Application:

This model combines the flexibility of fuzzy membership with the decisional simplification of shadowed sets. It provides smooth weighting while explicitly defining shadow zones for ambivalent companies.

Advantages:

These proposed methods aim to more accurately model uncertainty, ambiguity, imprecision, and cognitive granularity present in often noisy or incomplete financial datasets. In this work, we academically detail the theoretical foundations, implementation strategies, and application of each technique in the context of bankruptcy prediction.

4.1. Fuzzy Support Vector Machine (Fuzzy SVM)

The Fuzzy SVM introduces a fuzzy weight for each training point, based on its degree of reliability. This fuzzy membership degree reflects the uncertainty associated with the label of in noisy or ambiguous scenarios.

In bankruptcy contexts, certain companies may exhibit intermediate financial indicators—neither clearly healthy nor clearly distressed. Fuzzy SVM addresses such instances with reduced weight in the objective function, minimizing their influence on the separating hyperplane. This allows for:

Reduction of the effect of outliers,

Emphasis on borderline companies near financial distress,

Mitigation of bias toward the majority class.

In this study, we present several membership functions designed to assign continuous confidence values to samples based on geometric and statistical properties. These functions are crucial in fuzzy modeling, granular computing, and imbalance-aware learning.

-

Center Distance-Based Membership

This function evaluates the membership of a sample based on its Euclidean distance to the nearest class center.

For minority class samples, the membership is amplified:

Description: Samples closer to any class center receive higher membership. Minority class instances are emphasized by doubling their score.

-

Global Sphere-Based Membership

This function defines a membership value based on the distance to the global center of all samples.

where

is the global centroid and

is the radius.

Description: Points farther from the center receive lower membership. Minority samples get amplified membership values.

-

Hyperplane Distance Membership

This function calculates membership values based on the distance to the decision hyperplane of a linear SVM.

Description: Samples closer to the decision boundary receive higher scores. Minority class points have doubled membership.

-

Local Density-Based Membership (k-NN)

This method uses the average distance to

k-nearest neighbors to assess local density.

Description: Samples in dense regions (smaller average distances) get higher membership values.

-

Local Entropy-Based Membership

Using a probabilistic

k-NN classifier, this function computes local class entropy.

Description: Samples with high uncertainty (high entropy) receive lower membership values.

-

Intra-Class Distance Membership

This function measures the distance of a sample to the center of its own class.

Description: Points that are closer to the center of their own class get higher membership scores.

-

RBF-Based Membership

This method uses a Gaussian radial basis function to assign membership based on distance to the global center.

Description: Samples near the center receive values close to 1; distant ones decay exponentially.

-

RBF-SVM Margin Membership

This function derives membership based on the confidence margin from an RBF-kernel SVM.

where

is the decision function of the RBF-SVM.

Description: Samples close to the RBF-SVM boundary have high membership scores, capturing uncertainty near the decision margin.

-

Combined Membership Function

A weighted aggregation of all eight membership functions is proposed as:

Description: This function enables flexible integration of various membership strategies with user-defined weights for enhanced generalization and robustness in imbalanced scenarios.

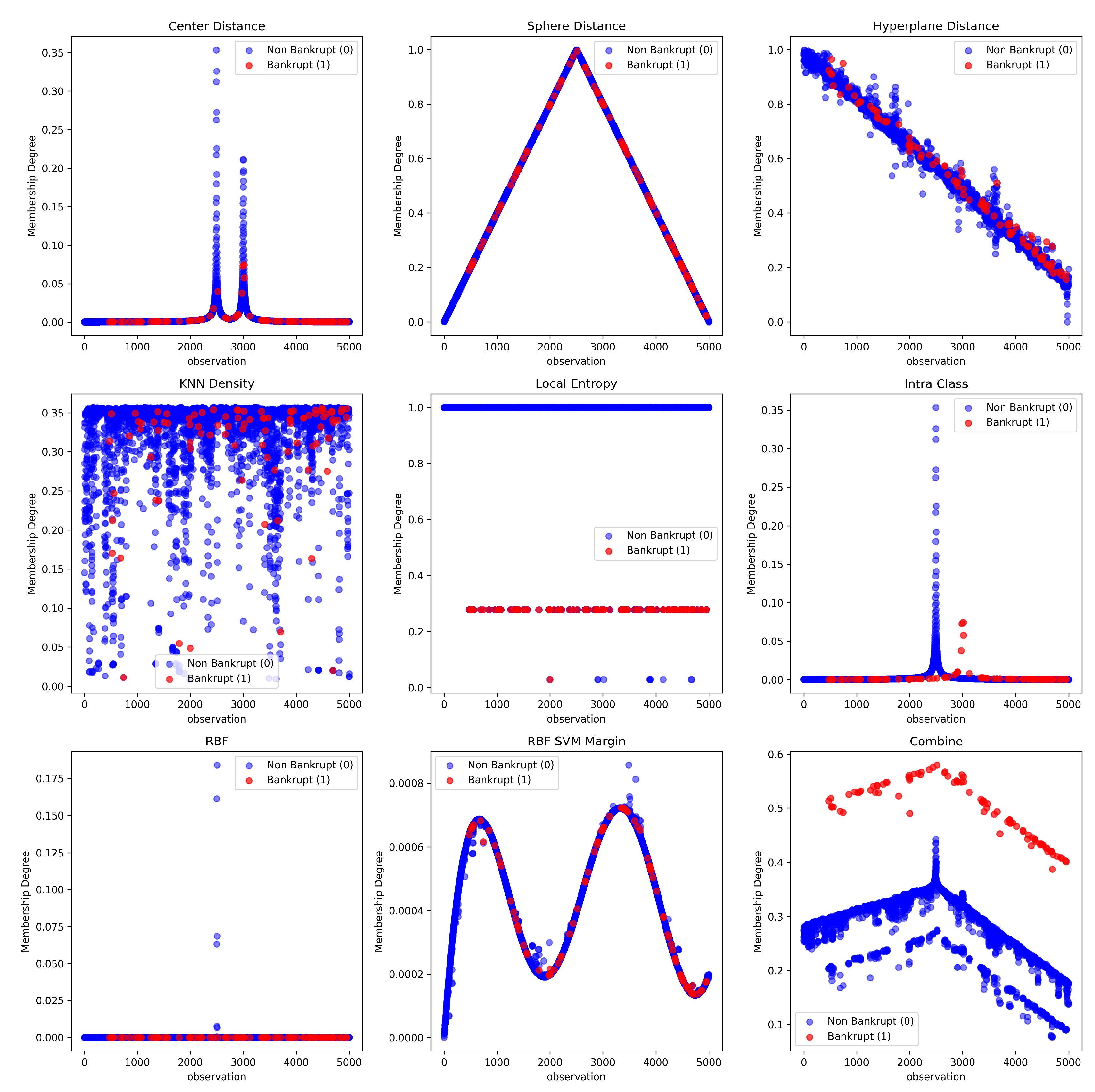

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of various membership functions in distinguishing the minority class (i.e., bankrupt companies), we applied nine different membership strategies to the financial dataset.

Figure 1 displays the scatter plots for each membership function, where the

x-axis represents a selected financial ratio (feature index 0), and the

y-axis denotes the computed membership degree.

Each subplot contrasts the membership values between the majority class (non-bankrupt, labeled 0) and the minority class (bankrupt, labeled 1). Blue (or green) dots correspond to the majority class, while red dots indicate the minority class.

From these visualizations, it is evident that the individual membership functions—such as center distance, sphere distance, KNN-based density, local entropy, and SVM-based distances—fail to consistently isolate the minority class. In most of these functions, the points from both classes are widely dispersed, leading to significant overlap and ambiguous boundaries between the classes.

In contrast, the combined membership function, which aggregates eight individual strategies using a weighted mean, shows a clear and sharp separation between classes. The bankrupt entities (minority class) are concentrated in the upper part of the graph (high membership degrees), while the non-bankrupt entities (majority class) are predominantly located in the lower region (low membership degrees). This indicates a successful granulation and robust class-specific membership estimation.

Conclusion: The combined function demonstrates a superior capacity for minority class discrimination by leveraging the complementarity of multiple geometric, probabilistic, and topological measures. This result highlights the benefit of ensemble-based membership modeling in imbalanced learning contexts such as bankruptcy prediction.

4.2. Rough Support Vector Machine (Rough SVM)

Based on Pawlak’s Rough Set Theory, the Rough SVM decomposes the set of companies into three regions:

Positive region (certainly bankrupt or non-bankrupt),

Negative region (certainly not bankrupt or bankrupt),

Boundary region (uncertain cases).

In supervised classification tasks such as bankruptcy prediction, the class distribution is frequently imbalanced, where the number of non-defaulting firms overwhelmingly exceeds that of defaulting ones. This imbalance, often extreme in financial datasets, severely affects the learning ability of traditional classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVM). Specifically, SVMs tend to bias decision boundaries toward the majority class, resulting in high overall accuracy but extremely poor recall for the minority class (i.e., failing firms), which is often the most critical to detect in practical applications. To address this fundamental challenge, we propose a novel preprocessing strategy grounded in Rough Set Theory (RST). The method constructs a granular representation of the input space, thereby structuring the dataset into subsets of varying classification certainty. This granulation-based approach is employed prior to training an SVM classifier and is particularly well-suited to scenarios involving extreme data imbalance. Core Idea: Rough Set-Based Approximation of the Input Space Rough Set Theory, originally introduced by Pawlak, enables the modeling of vagueness and uncertainty in data by defining lower and upper approximations of a concept (or class) based on indiscernibility relations. In the context of our study, each instance is assessed in relation to its resemblance to other instances, employing a linear kernel-based similarity metric. Depending on the proportion of its neighbors that share the same class, each instance is then categorized into one of three regions:

Positive Region (POS): Instances with high class certainty (e.g., ≥90% similar neighbors belong to the same class).

Boundary Region (BND): Instances with moderate uncertainty (50%–90% similar neighbors from the same class).

Negative Region (NEG): Instances with strong evidence of belonging to the opposite class (less than 50%).

This decomposition reflects the underlying structure of the data and respects its intrinsic uncertainty, which is crucial in the case of imbalanced datasets where minority class examples may not form dense clusters. Sampling Strategy Guided by Granular Regions Based on this approximation, we design a sampling mechanism that constructs a balanced training dataset from the rough-set-labeled granules: The POS region for both classes is retained entirely due to its high representational certainty.

The NEG region (typically dominated by majority class examples) is undersampled in a controlled manner.

The BND region is partially preserved to maintain instances near the decision boundary, crucial for defining the SVM margin.

This selection strategy ensures that the training dataset presents a balanced view of the class distributions, while also preserving the structural uncertainty around the class boundary — a key requirement for robust margin-based classifiers like SVM. Empirical Impact and Interpretability Once the dataset is reconstructed through this rough-set-driven sampling, it is used to train an SVM classifier with class balancing enabled. The experimental findings indicated noteworthy advancements in recall and F1 score, accompanied by either negligible or no deterioration in overall accuracy.. Notably, this improvement is achieved without introducing synthetic data (as in SMOTE) or relying on cost-sensitive tuning, and retains full interpretability of the data sampling process — a strong advantage in risk-sensitive domains such as finance. Moreover, the approach aligns naturally with the principles of granular computing, whereby the universe is partitioned into information granules (i.e., POS, BND, NEG), and computation proceeds not on raw data points, but on their semantic approximations. This makes the methodology theoretically grounded and practically robust. Advantages over Traditional Techniques Compared to traditional resampling or ensemble techniques, our rough-set-based preprocessing offers the following benefits: Data-dependent and adaptive: The granulation is guided by actual similarity structure in the data, not arbitrary thresholds. No synthetic samples: Avoids artificial inflation of minority class, preserving the fidelity of the dataset. Interpretability: Each instance’s inclusion or exclusion in training is justifiable based on its similarity-based certainty. Robustness: Maintains critical borderline cases (from the boundary region), ensuring effective margin construction by SVM. In highly imbalanced settings, where minority class examples are both sparse and noisy, classical SVM classifiers fail to adequately capture their structure, often collapsing into majority-biased decision boundaries. By incorporating a rough-set-based approximation mechanism prior to SVM training, our method introduces granular discernibility into the learning process, leading to significant performance gains in detecting rare but critical events such as firm bankruptcy. The methodology provides a principled, interpretable, and effective pathway to harness the power of SVMs in domains plagued by extreme class imbalance. Rough SVM handles these regions differently in the cost function, assigning varying importance depending on the certainty level. This approach is well-suited for classifying companies with ambiguous or contradictory features.

Unlike fuzzy logic, which assigns continuous membership degrees, Rough Set Theory defines lower and upper approximations of a set. The key implemented features include:

Indiscernibility Relation: The foundational element of rough set theory, computed using an epsilon distance threshold.

-

Lower and Upper Approximations:

- −

The lower approximation contains objects that definitively belong to a class.

- −

The upper approximation contains objects that may possibly belong to the class.

- −

The boundary region is defined as the difference between these two approximations.

-

Sample Weighting Methods:

- −

Rough Set Membership: Weights based on approximation set membership.

- −

Rough Set Boundary Distance: Weights derived from distance to the boundary region.

- −

Rough Set Quality: Weights determined by approximation quality.

- −

Rough Set kNN Granularity: Weights based on local granularity of k-nearest neighbors.

- −

Rough Set Reduction Importance: Weights reflecting attribute importance.

- −

Rough Set Cluster Boundary: Weights assigned by proximity to cluster boundaries.

- −

Rough Set Local Discernibility: Weights based on local instance discernibility.

- −

Rough Set Combined: A weighted aggregation of all above methods.

Regarding SVM Integration, the Rough Set approach is employed to assign weights to samples. These weights are subsequently utilized as sample-weight parameters during SVM training. Notably, samples from the minority class are assigned higher weights to mitigate class imbalance.

Sample Weighting Methods Based on Rough Set Theory:

Let be a set of instances in , and let be the corresponding class labels. We define C as the set of unique classes in y. Each of the following methods defines a membership score for instance , indicating its importance or certainty within the learning process.

-

Rough Set Membership-Based Weighting

Description:

This method assigns a weight based on whether an instance belongs to the lower approximation (certain region), the upper approximation (possible region), or outside both. Minority class instances are emphasized by doubling their scores.

-

Boundary Distance-Based Weighting:

Description:

This approach refines rough approximations by evaluating the relative position of an instance within the boundary region. A higher rank in the boundary implies greater uncertainty and thus lower weight.

-

Approximation Quality-Based Weighting:

Description:

This weighting method relies on the quality of approximation for each class, computed as the ratio of the size of the lower approximation to the upper approximation. Higher quality indicates clearer class definition.

-

kNN-Based Granularity Weighting:

Description:

This method measures the local purity around each sample, defined by the proportion of its k nearest neighbors that share the same label. High purity indicates greater certainty.

-

Feature Reduction Importance-Based Weighting:

Description:

The importance of each attribute is determined by its discriminative power, computed as the number of label changes when sorting instances by that attribute. Weights are assigned as a weighted sum of absolute attribute values.

-

Cluster Boundary-Based Weighting:

Description:

Weights are based on the distance of each instance to its closest cluster center (using k-means). Central points are given higher weights; marginal instances near boundaries are down-weighted

-

Local Discernibility-Based Weighting:

Description:

Weights reflect how many of the k nearest neighbors belong to different classes. Higher discernibility implies the instance is in a complex region, warranting higher emphasis.

-

Combined Rough Set Weighting:

Description:

This method computes a weighted linear combination of all the seven aforementioned weighting strategies. The weights can be tuned to reflect the relative importance of each criterion.

4.3. Shadowed Support Vector Machine (Shadowed SVM)

Sadowed SVM leverages the concept of shadowed sets, which simplifies fuzzy sets into three discrete values: 0, 1, and uncertain. It identifies a shadowed region within the feature space where companies are difficult to classify.

This mechanism:

Establishes a fuzzy boundary between classes,

Enhances the detection of critical zones,

Reduces the influence of uninformative examples.

Imbalanced datasets pose a significant challenge in classification tasks, especially for Support Vector Machines (SVM), which are sensitive to class distribution. To address this limitation, we incorporate the concept of Shadowed Sets, originally proposed by W. Pedrycz, to modulate the contribution of data instances via adaptive sample weighting. This approach refines the decision boundary by assigning higher influence to informative minority samples and reducing the impact of uncertain or noisy points.

Shadowed Set Theory extends fuzzy sets by introducing a three-region partition of the universe based on certainty:

This tripartite structure allows for a more interpretable handling of uncertainty. In the context of imbalanced learning, it enables the definition of crisp, uncertain, or fully irrelevant instances based on an underlying importance score derived from geometrical or statistical properties.

A central component of this methodology is the conversion of continuous importance scores into discrete shadowed memberships. The function

calculate_alpha_threshold determines lower and upper percentile-based cutoffs using a parameter

, defining the boundary of the shadowed zone. The conversion function

convert_to_shadowed then assigns:

where

typically. We describe eight strategies for computing instance-specific weights using the shadowed set logic. In all cases, the final weight vector is passed to the SVM classifier via the

sample_weight parameter.

-

Distance to Class Centers

This method calculates the Euclidean distance of each instance to its respective class centroid. The inverse of the distance is normalized and passed to the shadowed conversion. This ensures that points near their class center (representing prototypical examples) receive higher importance.

-

Distance to Global Sphere Center

Here, we compute distances to the global mean vector and normalize them. Instances close to the global center are assumed to be more representative and are therefore favored.

-

Distance to Linear SVM Hyperplane

We train a linear SVM and use the absolute value of its decision function as a proxy for confidence. These values are normalized and inverted, assigning higher weights to instances closer to the decision boundary.

-

K-Nearest Neighbors Density

This approach uses the average distance to k-nearest neighbors to estimate local density. High-density points are considered more informative and hence are promoted.

-

Local Entropy of Class Distribution

By training a KNN classifier, we compute the class distribution entropy in the neighborhood of each point. Lower entropy values indicate higher confidence, which translates into higher weights.

-

Intra-Class Compactness

This function assesses each instance’s distance to its own class centroid. The inverse of this distance measures intra-class compactness, helping to down-weight class outliers.

-

Radial Basis Function Kernel

We define a Gaussian RBF centered on the global dataset mean. Points near the center receive higher RBF values and are treated as more central to the learning task

RBF-SVM Margin An RBF-kernel SVM is trained, and the margin is used as a measure of importance. Instances near the margin are prioritized, reflecting their critical role in determining the separating surface.

-

Minority Class Boosting Mechanism

After computing initial weights, an explicit adjustment is applied to enhance minority class representation:

- −

If , assign

- −

If , assign

This ensures that no minority class instance is completely ignored and those with ambiguous status are treated as fully informative. This enhancement is crucial in highly skewed scenarios.

-

Multi-Metric Fusion via Shadowed Combination

The function

shadowed_combined aggregates all eight previously described metrics using a weighted average:

where

is the shadowed membership of instance

i under metric

j and

is the corresponding metric weight.

This Shadowed SVM significantly advances classical SVMs by embedding granular soft reasoning into the training process. Key advantages include:

- −

Data integrity is preserved; no synthetic samples are generated.

- −

Minority class enhancement is performed selectively and contextually.

- −

The methodology is generalizable to any learning algorithm supporting instance weighting.

These functions enable the computation of membership weights for data points based on various metrics of representativeness or ambiguity. By incorporating the theory of shadowed sets, they provide a rigorous framework for handling uncertainty and mitigating data imbalance in SVMs. This approach enhances the identification, reinforcement, and prioritization of minority instances while maintaining robustness against noise or ambiguous cases.

4.4. Quotient Space Support Vector Machine (Quotient Space SVM)

Quotient Space Theory enables modeling of cognitive granularity by introducing levels of abstraction over data. QSSVM learns to classify companies across various quotient spaces defined by aggregated or specific financial attributes (e.g., liquidity or solvency ratios).

This approach:

Structures data based on equivalence relations,

Enables hierarchical classification,

Enhances robustness against local variations.

Class imbalance poses a significant challenge for standard classifiers, particularly Support Vector Machines (SVMs), which tend to exhibit bias toward the majority class. Quotient Space Theory (QST), a framework derived from granular computing, offers a hierarchical and granular approach to abstract the data space while preserving its semantic structure.

The core idea involves transforming the original feature space into a quotient space composed of prototypes (or granules) that represent meaningful subspaces. An SVM is then trained on this enriched representation, enhancing inter-class discrimination—especially for underrepresented minority classes.

Key Implementation Steps:

Class-Specific Space Partitioning: The feature space is partitioned by class, with each subspace further divided into local clusters (granules). These clusters serve as prototypes, capturing the local data structure.

Adaptive Prototype Allocation: Minority classes are assigned more prototypes to compensate for their scarcity. Clustering methods (e.g., K-means for regular structures or DBSCAN for density-adaptive partitioning) generate the prototypes.

Quotient Space Projection: Each sample is mapped to a new feature space defined by its distances to the prototypes. This space is termed quotient because it abstracts the original structure while preserving discriminative relationships.

Weighted SVM Training: Minority-class prototypes are assigned higher weights (density_factor), which propagate to their constituent samples. The final classifier is an SVM trained on the quotient space representation rather than the raw data, enabling: Improved linear separability, Enhanced robustness to class imbalance, and Superior generalization performance.

To overcome these challenges, we propose an alternative based on Quotient Space Theory (QST), a mathematical framework from granular computing that models complex structures through equivalence classes. QST allows the decomposition of the input space into local representations, i.e., granular regions (quotients), enabling a balanced and abstracted view of the data distribution. We integrate QST into SVM learning by transforming the input space into a distance-based representation relative to learned class-dependent prototypes.

The core of the QST-based method lies in constructing a

Quotient Space Generator which, for each class, forms local regions using clustering (e.g., KMeans or DBSCAN). Let

be the feature space and

the class labels. For each class

, we define an equivalence relation via a clustering function

that partitions

(subset of samples with label

c) into

clusters:

Each cluster center (prototype)

represents a granular subspace. The input samples

are projected into a new feature space defined by their distances to all prototypes:

where

d is typically the Euclidean or Mahalanobis distance.

This transformation performs three functions:

Granular abstraction: Converts raw features into semantically richer distance-based representations.

Balancing effect: For the minority class, more granular regions are created to increase representation diversity.

Dimensionality control: Reduces the complexity by condensing local distributions.

To handle imbalance explicitly, a density-based weighting mechanism is introduced. The number of clusters is adaptively set based on the class cardinality . Minority classes receive a higher number of clusters (up to a limit), and their corresponding cluster weights are multiplied by a density factor to emphasize their importance.

Further, during SVM training, we compute sample weights inversely proportional to class frequency:

This ensures the SVM decision boundary is not skewed toward the majority class, even after quotient transformation.

To capture higher-order structural dependencies, we propose a multi-level abstraction using

Hierarchical Quotient Spaces, where the quotient transformation is recursively applied. Formally:

This results in deep representations where each level extracts increasingly abstract granular features. The final representation is fed into a standard SVM classifier.

In an enhanced variant, we integrate

metric learning by adapting the distance function per class. For class

c, we compute the inverse covariance matrix

, leading to Mahalanobis distance computation:

This adaptation allows better alignment with intra-class variations and helps disambiguate overlapping class regions, particularly in high-dimensional spaces.

We provide a modular Python implementation comprising:

QuotientSpaceGenerator: Performs class-wise clustering and prototype extraction using KMeans or DBSCAN.

QuotientSpaceSVM: Applies SVM on the transformed quotient representation with balancing weights.

HierarchicalQuotientSpaceSVM: Constructs layered quotient transformations before SVM training.

AdaptiveMetricQuotientSpaceSVM: Introduces Mahalanobis-based adaptive distance metrics.

The proposed QST framework allows learning in quotient manifolds, which can be seen as coarse-to-fine approximations of the data space. From a topological standpoint, each transformation reduces intra-class variance while preserving class-wise discriminative features. In the context of granular computing, each prototype encapsulates a semantic granule, and learning proceeds by reasoning over these granules, not raw instances.

The integration of Quotient Space Theory with SVM provides a robust, interpretable, and computationally efficient approach to deal with imbalanced data. Through granular abstraction, class-wise clustering, adaptive weighting, and hierarchical modeling, this method enhances the separability of minority classes without sacrificing performance on majority ones. Future directions include its extension to multi-class imbalances and online learning scenarios.

4.5. Fuzzy-Shadowed SVM (FS-SVM)

This hybrid combines the flexibility of fuzzy membership with the decision simplification of shadowed sets. It provides smooth weighting while defining decisive shadow zones for ambivalent companies.

Advantages:

Imbalanced datasets are common in real-world classification problems, where one class (typically the minority class) is significantly underrepresented compared to the majority class. Traditional Support Vector Machines (SVMs) tend to bias toward the majority class, leading to poor performance on the minority class. To mitigate this issue, we propose a hybrid approach based on the combination of Fuzzy Set Theory and Shadowed Set Theory within the SVM framework.

Fuzzy Set Theory enables soft modeling of uncertainty by assigning each training sample a fuzzy membership , indicating its confidence or importance in training. In the context of imbalanced data, higher memberships are usually given to minority class samples, enhancing their influence during model training.

The modified objective function of Fuzzy SVM is:

Shadowed Set Theory transforms fuzzy memberships into three distinct regions:

Positive region (): membership set to 1,

Negative region (): membership set to 0,

Shadowed region (): membership remains uncertain in (0,1).

This partitioning allows the classifier to better model ambiguous samples near the decision boundary, where misclassifications frequently occur in imbalanced data.

Fuzzy sets provide a gradual weighting mechanism, while shadowed sets enable explicit modeling of boundary uncertainty. Their integration yields a hybrid FS-SSVM model that:

Enhances minority class contribution via fuzzy memberships,

Reduces overfitting and misclassification in ambiguous zones through shadowed granulation.

Fuzzy Membership Calculation: Assign fuzzy memberships to each instance using distance-based, entropy-based, or density-based functions.

Modified SVM Training: Use transformed fuzzy-shadowed weights in the SVM loss function to penalize misclassifications proportionally to sample certainty.

Minority Emphasis: The fuzzy component ensures greater influence of rare class examples in decision boundary construction.

Uncertainty Management: Shadowed sets allow safe treatment of boundary points by avoiding hard decisions for uncertain data.

Performance Gains: Improved G-mean, Recall, and F1-score, ensuring better trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.

Adaptability: Thresholds and offer flexibility in managing granularity and uncertainty.

Preprocessing: Normalize data and compute imbalance ratio.

Fuzzy Memberships: Use functions based on distance to class center or local density.

Parameter Selection: Tune , , and regularization parameter C using cross-validation.

Evaluation Metrics: Use G-mean, AUC-ROC, Recall, and F1-score rather than accuracy alone.

The Fuzzy-Shadowed SVM (FS-SSVM) framework integrates the strengths of both fuzzy and shadowed sets to address the imbalanced data problem. This hybridization enables a better balance between classes, robust uncertainty handling, and improved classification performance, particularly in critical domains such as fraud detection, medical diagnostics, and bankruptcy prediction.

Imbalanced data classification presents a persistent challenge in supervised learning, where traditional models tend to be biased toward the majority class. To address this, we propose a novel hybrid approach—Fuzzy Shadowed Support Vector Machine (FuzzyShadowedSVM)—which integrates two complementary uncertainty modeling paradigms: Fuzzy Set Theory and Shadowed Set Theory. This hybridization enhances the robustness of SVM decision boundaries by adjusting instance influence based on fuzzy memberships and proximity to the classification margin.

The proposed model is grounded in two core ideas:

Fuzzy Sets: Fuzzy logic assigns each training instance a degree of membership to its class, reflecting the confidence or representativeness of that instance. High membership indicates a central or prototypical instance; low membership reflects ambiguity or atypicality.

Shadowed Sets: Introduced to model vague regions in uncertain environments, shadowed sets define a shadow region around the decision boundary where class labels are unreliable. In this model, instances in this margin are down-weighted to reduce their impact during training, recognizing their inherent ambiguity.

The hybrid FuzzyShadowedSVM constructs a soft-margin classifier that:

Computes fuzzy membership degrees for all training samples using multiple geometric and statistical criteria;

Identifies shadow regions by evaluating the distance of instances from the SVM decision boundary;

Adjusts sample weights by combining fuzzy memberships and a shadow mask, reducing the influence of uncertain instances and enhancing minority class detection.

The model provides several strategies to compute fuzzy membership values , representing the relative importance of each instance . These methods include:

Center Distance: Membership is inversely proportional to the distance to the class center.

Sphere Distance: Membership decreases linearly with the distance to the enclosing hypersphere.

Hyperplane Distance: Membership is proportional to the absolute distance to a preliminary SVM hyperplane.

k-NN Density and Local Entropy: Measures local structure and class purity via neighborhood statistics.

Intra-Class Cohesion: Membership is inversely related to within-class dispersion.

RBF Kernel and SVM Margin: Membership decays exponentially with Euclidean or SVM margin distance.

For improved stability and expressiveness, a weighted combination of these methods is employed:

where

is the weight of the

method and

is the membership derived from it.

To capture uncertainty near the classification margin, a preliminary SVM is trained. For each instance

, its absolute decision score

is normalized and compared to a shadow threshold

. Instances satisfying:

are flagged as being in the

shadow region. Their membership is then attenuated:

where

is the

shadow weight parameter, allowing us to reduce the influence of ambiguous instances near the decision boundary.

Using the adjusted memberships , the final SVM is trained with instance-specific sample weights. This formulation penalizes misclassification more strongly on highly relevant, non-shadowed instances and less on ambiguous ones. This weighting strategy improves class discrimination and helps alleviate the bias toward majority classes in imbalanced datasets.

The model includes a grid search facility to optimize:

C: SVM regularization parameter;

: RBF kernel width;

: shadow threshold;

: shadow weight;

Membership method (e.g., “center_distance”, “svm_margin”).

This ensures adaptive and robust model selection based on cross-validation performance.

The proposed FuzzyShadowedSVM offers several notable contributions:

It models instance uncertainty on two levels: class confidence (fuzzy membership) and ambiguity near the decision boundary (shadow set).

It provides a flexible and extensible framework with multiple interpretable membership functions.

It introduces region-based instance discounting directly into kernel-based classifiers.

It maintains interpretability, as the weighting mechanisms are derived from geometric or statistical properties of the data.

It improves performance on minority class recognition, often reflected in F1-score, G-mean, and AUC-ROC.

4.6. Imbalanced Data Problem

Let a dataset

where

and the number of positive instances

. The imbalance ratio is defined as:

Our general Granular SVM framework is formulated as:

where

represents the granular operator specific to each variant.

-

Fuzzy SVM Formulation:

With membership degrees

, the optimization problem becomes:

subject to:

-

Rough SVM Formulation

For each class

, we define:

-

Shadowed SVM Formulation:

-

QS SVM Formulation:

Quotient spaces

are defined with:

Multi-scale Objective Function

5. Experimental Studies

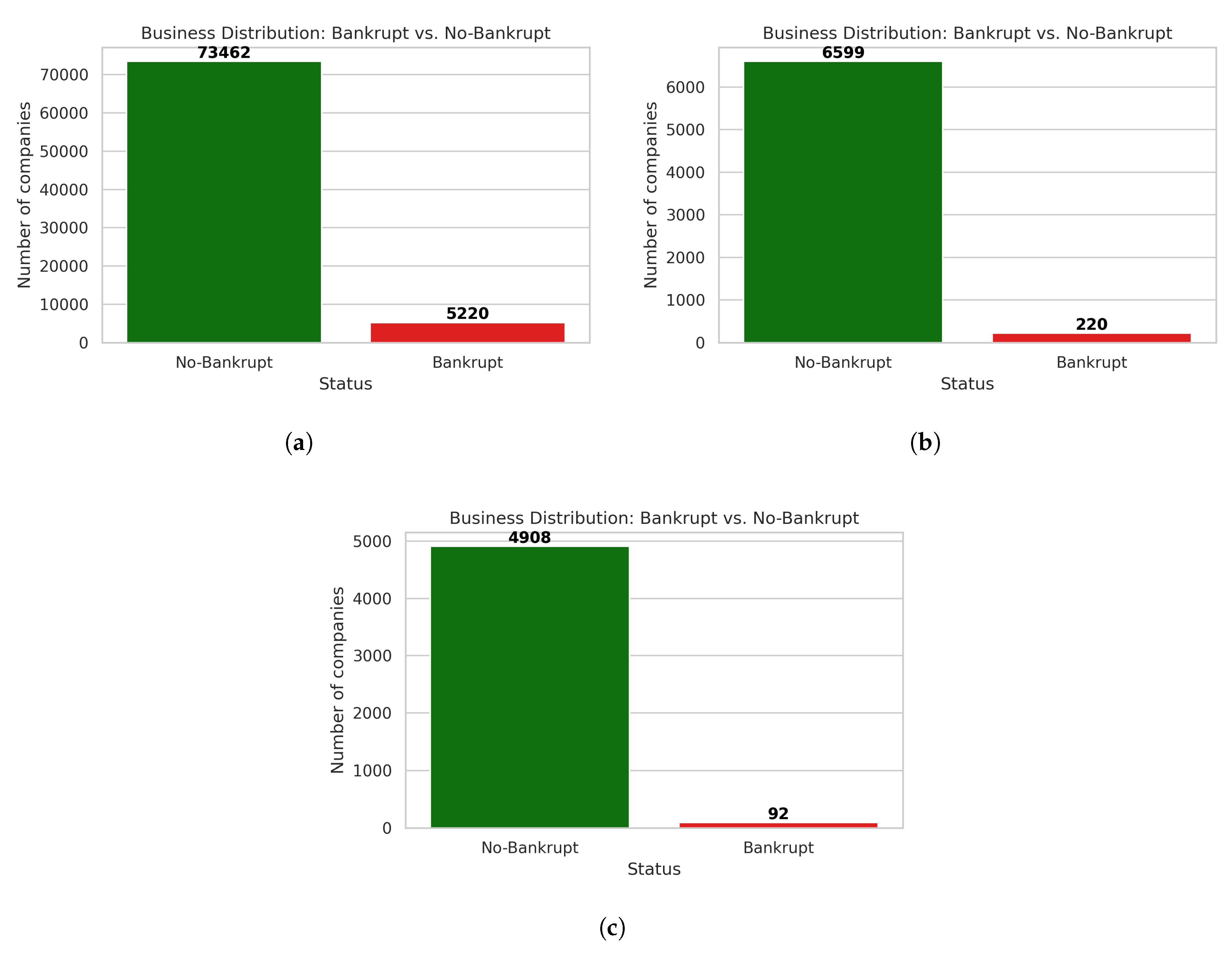

The choice of dataset is crucial in the experimental phase, as it allows for evaluating the robustness of one technique compared to another.

-

The first dataset (data1) is the Bankruptcy Data from the Taiwan Economic Journal for the years 1999–2009, available on Kaggle:

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/fedesoriano

/company-bankruptcy-prediction/data.

It contains 95 features in addition to the bankruptcy class label, and the total number of instances is exactly 6,819.

-

The second dataset (data2) is the US Company Bankruptcy Prediction dataset, also sourced from Kaggle:

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/utkarshx27/

american-companies-bankruptcy-prediction-dataset.

It consists of 78,682 instances and 21 features.

The third dataset (data3) is the UK Bankruptcy Data, containing 5,000 instances and 70 features.