1. Introduction

NUVO theory reinterprets gravitational and quantum phenomena within a globally flat, conformally modulated spacetime[

1]. Rather than relying on the Riemann curvature of general relativity, NUVO attributes geometric distortions to a scalar conformal field

that modulates both time and spatial intervals pointwise. This scalar modulation accounts for gravitational redshift, time dilation, orbital advance, and even quantum-level phenomena such as discreteness and binding energy—while preserving flat underlying geometry.

However, to progress beyond scalar formulations and engage with broader field-theoretic constructs—such as stress-energy tensors, electromagnetic fields, and conserved currents—it is necessary to extend NUVO into a covariant tensor framework [

2]. This paper accomplishes that task while maintaining NUVO’s commitment to flat background geometry.

In particular, we seek a formalism that:

Allows scalar, vector, and tensor fields to be defined and differentiated under the conformally transformed metric .

Defines Christoffel symbols, covariant derivatives, and divergence operators consistent with scalar-based modulation.

Preserves conservation laws and energy-momentum flow without invoking spacetime curvature.

Enables consistent coupling of with fields such as and in a purely conformal setting.

We emphasize that this is not a reformulation of NUVO into general relativity. Instead, it is a mathematically rigorous extension that equips NUVO with the standard machinery of covariant tensor calculus—applied not to curved space, but to a flat space modulated by a scalar field.

This framework opens the door to:

Describing how sinertia and pinertia behave as geometric densities.

Tracking fluxes and conservation across scalar-modulated regions.

Coupling NUVO’s scalar modulation to electromagnetic, fluid, and nuclear systems.

Building bridges to gauge theory and possibly uncovering new invariance principles.

In the sections that follow, we review the conformal structure of the NUVO metric, construct covariant derivatives for tensor fields in this setting, derive the relevant Christoffel symbols, and develop the corresponding energy-momentum tensor formalism. We then apply this framework to illustrative examples and discuss implications for future theoretical development.

2. Review of Conformal Metric Structure

NUVO theory is based on a globally flat spacetime background modulated by a scalar conformal field

. This field scales both temporal and spatial intervals without introducing intrinsic curvature. The effective metric is given by a conformal transformation of the Minkowski metric [

3]:

where

is the flat Minkowski background, and

is a dimensionless scalar field depending on spacetime coordinates and possibly on the velocity of the test particle.

2.1. Inverse Metric and Determinant

The inverse metric is given by:

The determinant of the metric is:

since in four-dimensional spacetime, the determinant of the conformal metric scales as the fourth power of the scalar factor.

2.2. Christoffel Symbols for Conformal Metrics

To define covariant derivatives, we need the connection coefficients (Christoffel symbols) associated with the metric (

1). These are given by:

This expression reflects the fact that the entire connection arises from variations in over spacetime; if is constant, the connection vanishes and spacetime behaves as flat Minkowski space.

2.3. Geodesics in Conformal Spacetimes

The geodesic equation in this metric structure is:

Because the Christoffel symbols in (

4) depend only on derivatives of

, the resulting trajectories differ from those in flat space even though the background curvature remains zero. This reinforces the idea that modulation, not curvature, governs dynamics in NUVO theory.

2.4. Interpretation

The conformal metric retains the light cone structure and causal ordering of special relativity but introduces local rescaling of durations and distances. As such, it permits geodesic deviation, redshift, time dilation, and orbit precession, all without invoking intrinsic curvature.

In this framework, tensor fields are not influenced by spacetime curvature in the Riemannian sense but must still transform covariantly under the -scaled metric. This motivates the need for a full covariant formalism built atop this conformal structure, which we develop in the next section.

3. Covariant Derivatives and Tensor Fields

In this section, we define how scalars, vectors, and higher-rank tensors are differentiated under the conformally flat metric . Even though the spacetime has zero Riemannian curvature, the spatial and temporal rescaling induced by introduces non-zero connection coefficients that affect how fields are transported and conserved.

3.1. Covariant Derivative of Scalar, Vector, and Tensor Fields

The covariant derivative of a scalar field

is simply the partial derivative:

For a vector field

, the covariant derivative is:

For a rank-2 tensor

, the covariant derivative is:

Lower indices follow similar rules, with signs reversed:

3.2. Behavior of under Covariant Differentiation

Since

is a scalar field, its covariant derivative reduces to the partial derivative:

However, composite expressions involving , such as or energy-momentum tensors, acquire additional contributions due to the connection terms when differentiated.

The second covariant derivative of

, which appears in wave equations or conservation laws, is:

This form will appear in the scalar field equation and in curvature-like quantities constructed from gradients.

3.3. Commutation Relations and Derivative Identities

While the Riemann tensor vanishes in a globally flat background, the presence of a non-trivial

leads to non-zero commutators for covariant derivatives acting on vector and tensor fields. For example, acting on a vector:

since the Riemann tensor still vanishes in this conformally flat geometry. However, **derivatives of

appear in the Christoffel symbols**, so functional dependencies in

must still be accounted for when evaluating nested derivatives or divergence expressions.

3.4. Interpretation

Even in the absence of curvature, the conformal modulation by introduces a nontrivial geometric structure that demands the use of covariant derivatives for consistency. This allows NUVO theory to retain flat geometry while still capturing tensorial transport, field divergence, and energy–momentum conservation across scalar-modulated domains.

This covariant structure is particularly important for modeling field interactions (e.g., electromagnetic, fluid, nuclear) that obey conservation laws but evolve within a modulated spacetime geometry. In the next section, we apply this framework to define the energy–momentum tensor and derive its divergence properties.

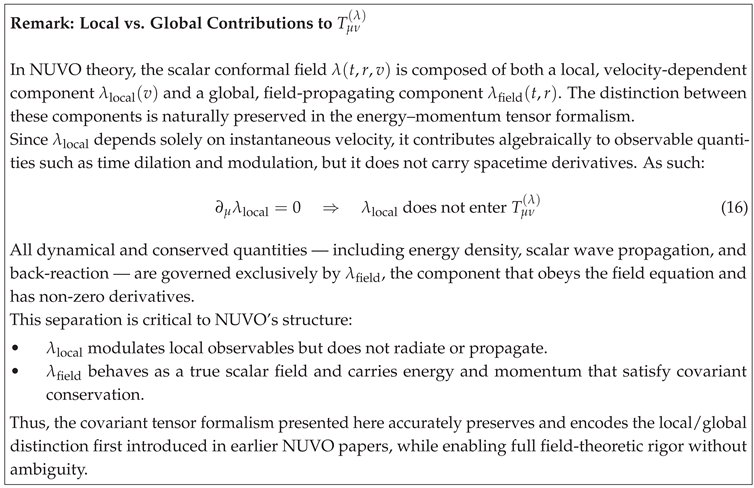

4. Conservation Laws and Energy-Momentum Tensor

In any field theory with continuous symmetries, conservation laws arise naturally via Noether’s theorem. In NUVO, although the background remains globally flat, the presence of a position- and velocity-dependent scalar field

modulates the geometry and necessitates a consistent energy–momentum description under the conformal metric:

Covariant Divergence and Conservation

Conservation of energy and momentum in a scalar-modulated spacetime requires the covariant divergence of

to vanish:

This condition, expanded in terms of the conformal metric and its Christoffel symbols, reads:

where

as derived previously.

This ensures that in any region where evolves continuously and differentiably, the scalar field’s energy and momentum remain conserved in a covariant sense, even in the absence of curvature.

Implications for Field Propagation and Back-Reaction

The conservation law (

14) implies that

carries real energy and momentum — capable of being sourced, transported, and dissipated. Key consequences include:

Scalar field energy can propagate in response to matter motion, , or orbital acceleration.

Sinertia collapse or closure resonance can release scalar radiation modeled through .

Coupled field systems (e.g., ) conserve total energy–momentum across both sectors.

Because the source term in the field equation for is often matter density , any local change in is balanced by an adjustment in scalar energy density through .

Interpretation

This structure gives NUVO a rigorous mechanism to describe energy–momentum exchange in a purely scalar-geometric setting. Unlike general relativity, which ties curvature to matter via Einstein’s equation [

4]:

NUVO retains a globally flat background and instead uses scalar modulation and its gradients to mediate dynamics. The modulation field

is both the generator of geometric structure and the carrier of scalar energy, unified through Eq. (

13) and Eq. (

14).

5. Examples of Tensor Coupling

With a covariant formalism in place, we now explore how common physical tensor fields couple to the NUVO conformal background. Although the underlying spacetime remains flat, the presence of the scalar modulation field modifies the transport, divergence, and propagation of tensor fields. These examples illustrate how classical fields like electromagnetism, as well as NUVO-specific constructs like sinertia and pinertia, can be embedded within this geometric framework.

Electromagnetic Tensor in NUVO Background

The electromagnetic field tensor in flat spacetime is defined as:

This antisymmetric tensor is invariant under conformal transformations and retains its structure under the transformation . However, its divergence is affected by the -modulated metric determinant.

The covariant form of Maxwell’s equations becomes:

The divergence of

under a conformally scaled metric with

becomes:

Thus, scalar modulation enters the field equations multiplicatively:

This implies that while retains its form, its divergence — and hence the effective energy density and wave propagation — are modulated by the local value and gradient of .

Sinertia and Pinertia as Tensor Densities

NUVO introduces two fundamental geometric properties:

Pinertia: The coupling of matter to space, associated with the anchoring of mass to the scalar field.

Sinertia: The coupling of space to matter, representing how scalar modulation responds to geometric stress.

While originally conceived as scalar quantities, sinertia and pinertia can be promoted to tensor densities in dynamic contexts. For example, a sinertia flux in a modulation-driven system may be expressed as:

where

is the scalar sinertia density and

is a locally defined 4-velocity under the conformal metric.

In such contexts, sinertia collapse or modulation closure (e.g., in black hole or nuclear regimes) can be modeled using tensorial stress–energy terms that track the scalar field’s back-reaction.

Geometric Stress–Energy Flow in Modulated Spacetime

Scalar modulation directly affects the energy and momentum flow of all tensor fields coupled to the conformal geometry. Effective energy and momentum densities are rescaled by powers of .

For a given bare energy density

, the observed value becomes:

Likewise, the momentum flux is given by:

These expressions highlight how modulation alters local observables, energy propagation, and radiative transfer. Scalar energy carried by can accumulate, collapse, or emit under these scaling rules, providing a mechanism for gravitational radiation or quantum transitions without curved spacetime.

Summary

These examples demonstrate that NUVO’s scalar-modulated geometry supports consistent tensor coupling while preserving physical structures such as gauge symmetry and conservation laws. Classical fields such as and NUVO-native concepts like sinertia and pinertia can be described rigorously using the covariant formalism developed in this paper. The result is a unified, flat-space geometric theory in which energy and momentum flow through modulated fields rather than curved spacetime.

6. Interpretation and Limitations

The covariant tensor formalism developed in this paper extends NUVO theory beyond scalar-only formulations while preserving its foundational assumption: that spacetime is globally flat and all gravitational or inertial effects arise from modulation via a scalar field . This section clarifies what this approach enables, how it differs from curvature-based theories, and where its applicability may be limited.

Preserved Flatness and Non-Curvature

Although we have introduced Christoffel symbols, covariant derivatives, and energy–momentum tensors, these arise entirely from the conformal scalar field

. The underlying spacetime remains flat in the Riemannian sense:

This distinguishes NUVO from general relativity, where gravitational dynamics are tied directly to spacetime curvature. In NUVO, all geometric structure and dynamical deviation from flatness emerge instead through pointwise modulation by , leading to gravitational and quantum effects without invoking curvature.

Boundaries of Applicability

While powerful and internally consistent, the NUVO covariant formalism has explicit limitations:

It does not model Riemannian curvature. Predictions based purely on curvature (e.g., Einstein–Hilbert action derivations, lensing via geodesic deviation in curved space) must be recovered from -modulated dynamics instead.

It assumes is differentiable. Singularities, step discontinuities, or topological defects require special treatment or matching conditions not yet formalized.

It does not yet quantize tensor fields or . Quantum fluctuations, operator structure, and discrete modulation dynamics are addressed in later papers.

Why It Remains Scalar-Based

Although the introduction of tensors might suggest a shift toward more traditional field theory, NUVO remains scalar-based at its core. The modulation field

is the sole generator of geometric structure:

All tensor quantities are defined and evolve within this conformally scaled geometry, not as fundamental curvatures but as secondary objects tracking flux, stress, and conservation. The scalar alone determines time dilation, orbital advance, redshift, and radiation.

Summary

The covariant tensor formalism developed here enables NUVO to express energy, momentum, and field interaction in a scalar-modulated, flat-space setting. It preserves NUVO’s foundational principles while providing rigorous mathematical tools needed to describe classical field dynamics, conservation, and propagation.

By combining scalar modulation with tensor calculus, NUVO bridges the conceptual gap between Newtonian force models and relativistic field theory — all while remaining free of intrinsic spacetime curvature.

7. Outlook and Future Work

The extension of NUVO theory to a covariant tensor formalism on a conformally flat background provides a powerful and consistent foundation for describing field dynamics without invoking spacetime curvature. By anchoring all geometric effects in the scalar modulation field , and defining covariant derivatives and conservation laws accordingly, NUVO now gains the tools required to explore a broad class of physical phenomena within a unified framework.

Enabling Advanced Applications

This covariant formalism paves the way for several advanced applications:

Gravitational radiation: The stress–energy tensor supports dynamic scalar radiation without requiring a curved background. The framework developed here can describe radiation from orbiting or collapsing systems in terms of scalar field gradients and their conserved fluxes.

Electromagnetic and gauge field coupling: The covariant derivative structure allows consistent interaction between and tensor fields such as , laying the groundwork for a NUVO-compatible gauge theory.

Fluid, plasma, and continuum systems: Modulation-aware formulations of hydrodynamic and thermodynamic fields may now be implemented using -dependent stress–energy flow and divergence.

Sinertia collapse modeling: Tensor descriptions of pinertia and sinertia will enable detailed simulations of black hole analogs, nuclear resonance, and scalar field emissions under confinement and collapse.

Bridge to Quantum Geometry

Although this paper remains entirely classical in its formulation, it prepares the foundation for quantum developments by:

Introducing a geometric, modulation-dependent energy carrier (),

Formalizing how field propagation and quantized exchange may arise from boundary conditions and standing wave closure (e.g., resonance in ),

Offering a language to describe operator-valued fields on a scalar-modulated, flat background (to be developed in future NUVO quantum papers).

This structure allows future work to derive quantum discreteness [

5], particle–field duality, and geometric interpretations of Planck-scale effects without modifying the flat geometric foundation.

Path Forward

Future work will build directly on the formalism developed here:

Extend the field equation to allow for nonlinear modulation coupling and higher-order interactions between and its sources.

Formalize the role of geometric closure and scalar standing waves in triggering global field propagation (modulated quantum transitions).

Develop a gauge theory compatible with conformal scalar geometry, possibly revealing deeper symmetry structure in NUVO.

Quantize the scalar modulation field and construct operator algebras that yield quantum commutation rules from geometric modulation patterns.

Conclusion

This paper has extended NUVO theory into a fully covariant tensor framework while preserving its flat-space, scalar-modulated foundation. The result is a consistent and physically meaningful structure that supports conservation laws, field interactions, and stress-energy transport — all derived from a scalar field with no intrinsic curvature.

By enabling the language of modern field theory to coexist with NUVO’s geometric simplicity, this work opens the door to future developments in gravitational radiation, quantum discreteness, and unified field modeling in flat-space scalar geometry.

References

- Austin, R.W. From Newton to Planck: A Flat-Space Conformal Theory Bridging General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. Preprints 2025. Preprint available at https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202505.1410/v1.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. The Classical Theory of Fields; Pergamon Press, 1975.

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; W. H. Freeman, 1973.

- Einstein, A. Explanation of the Perihelion Motion of Mercury from General Relativity Theory. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1915, pp. 831–839.

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).