1. Introduction

The

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) is the microorganism that lies between viruses and bacteria, often co-infecting with other viruses [1−2]. It is an essential respiratory pathogen, causing illnesses from mild upper respiratory infections to severe atypical pneumonia, primarily affecting children and young adults. Typically, this disease presents with symptoms related to respiratory and lung infections, and in hospital settings, the mortality rate is around 10-30% [1−4]. Up to now, a large number of reports have been published on the relationships between

M. pneumoniae and networks of the community-acquired infections [5−7]. Although the investigation report offers a wealth of data, managing and treating

M. pneumoniae infection effectively continues to be difficult. The limited biosynthetic capability and slow replication speed of

M. pneumoniae are due to its extremely small genome [8−10]. Transmission of

M. pneumoniae occurs through close interaction between respiratory droplets and mucosal surfaces, resulting in local inflammation and other effects [

11]. At the initial stage of

M. pneumoniae infection, the organism attaches to the columnar epithelium of ciliated cells, shielding itself from local cytotoxic effects and mucociliary clearance [

6]. A specialized organelle facilitates cell adhesion to sialic acid glycoproteins and sulfate glycolipids, featuring a central core of dense filaments and a pointed structure of adhesins and accessory proteins [

12,

13]. The key proteins such as the p1 adhesin, p30 adhesin, and p65 adhesin are involved in binding to receptors. The high molecular weight proteins HMW-1, HMW-2, and HMW-3 interact with the adhesins p1, p30 and p65 to aid in cell fusion [

14,

15]. These proteins could be targeted by drugs for effective treatment and vaccine development to prevent the

M. pneumoniae infection. Besides, the increasing rate of macrolide resistant strains and the harmful side effects of other sensitive antibiotics in young children make them difficult to treat and increase health risks or reinfection [16−20].

The design of vaccines using epitopes is currently a focal point in the treatment of infectious diseases [

21]. Epitope vaccines dynamically stimulate the immune system’s humoral and cellular branches. The vaccine is made up of highly immunogenic T cell epitopes, which activate the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), or helper T lymphocyte (HTL) to respond specific epitopes [

22]. Protective immune responses are stimulated significantly by HTL in many bacterial infections. Hence, recognizing the peptides responsible for T cell responses is vital for creating powerful epitope-based peptide vaccines [

22]. Peptide vaccines that utilize epitopes may provide benefits such as affordable production, the ability to choose immune types, and better safety. Methods from immunoinformatics or computational biology have been crucial in designing peptide vaccines based on epitopes. Up to now, various types of

M. pneumoniae vaccines have been reported, including whole cell vaccines, subunit vaccines and DNA vaccines [

20]. However, due to the continuous mutation of pathogens, traditional vaccines are unable to provide effective efficacy protection for the human body. Therefore, it is necessary to design broad-spectrum vaccines for preventing large numbers of wild-type microorganisms. Thus, vaccine design based on conserved regions of antigens can effectively avoid the failure caused by pathogen mutations. In this study, we aim to design consensus sequences through the conserved regions of antigenic proteins from

M. pneumoniae to extensively cover

M. pneumoniae strains with various resources. The proposed immunoinformatics approach here for vaccines can be broadly applied as a promising candidate for pathogen-specific vaccines in treating pneumonia and the associated infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proteome Data and Consensus Sequences

The entire biological structural proteins such as HMW-1, HMW-2, HMW-3, and p1-adhesin from M. pneumoniae were chosen to predict the effective CTL and HTL epitopes. First, the proteins were de-duplicated through CD-HIT with 100% identification. Then, MAFFT v7.487 was used to perform multiple sequence alignment on these proteins. After further verification of these aligned sequences, the Python script was used to identify their common regions, i.e., to retain the most frequently occurring amino acids, thus forming a consensus sequence. By comparing the genome sequences of different species or individuals, common conserved regions can be identified, which are often closely related to gene function.

2.2. Prediction and Evaluation of the MHC I and II Epitopes

The sites that bind to major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) with 9-mer and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) with 15-mer were assessed through NetMHCIIpan-3.2 and NetMHCpan-4.1, respectively. We selected the corresponding Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) alleles based on the researches of Guan et al (2025) [

23]. For MHC I, the epitopes exhibiting the highest affinity to HLA (< 0.5%) were chosen, while for MHC II, those epitopes displaying a comparatively lower affinity (< 10%) were picked.

The VaxiJen v2.0, IEDB-tools, ToxinPred were chosen for antigenicity prediction, epitope conservation analysis and toxic peptides prediction, respectively [

23].

2.3. Immunogenicity of MHC class I Peptides

We anticipated the immunogenicity of MHC I peptides with the Class I Immunogenicity (

http://tools.iedb.org/immunogenicity/) from IEDB. It assesses the immunogenic epitopes by analyzing the physicochemical traits of amino acids and their sequence-specific localization. The peptides with positive predictions were likely to have immunogenicity, and we preserved the epitopes with scores exceeding 0.12.

2.4. Cytokine Induction of MHC Class II Peptides

Furthermore, the MHC II epitopes were evaluated by their capacity to induce cytokine production, including IL10, IL4 and IFN-γ. In this case, the IFNepitope, IL4pred and IL10pred servers were used to predict the characteristics of these epitopes with default parameters [

23].

2.5. Population Coverage

To calculate population coverage, the T-cell epitopes and their corresponding HLA binding alleles were used. The population coverage of each epitope was predicted with the online tool (

http://tools.immuneepitope.org/population) from the IEDB server [

23].

2.6. The multi-Epitope Vaccine Construction

The multi-epitope vaccine was constructed using epitopes that showed the best antigenicity, immunogenicity, as determined by the prior prediction and sequence filter. Specifically, the HTL epitopes were adjoined with the GPGPG linker, while linear CTL epitopes were adjoined with the AAY linker, both of which belonged to the flexible linker. The effective linkers can prevent protein misfolding and overlap of functional regions.

2.7. Assessment of Physicochemical Properties and Solubility

The physicochemical traits are significant characteristics in protein. The physicochemical characteristics of the predicted epitopes were analyzed using Expasy Protparam (

https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) to gain further insight into the basic nature of the vaccine. In addition, the solubility of the vaccine was analyzed through the Protein-Sol website (

http://protein-sol.manchester.ac.uk).

2.8. Antigenicity and Allergenicity Analysis

Further research was conducted on the peptides to verify their potential for inducing allergies and immunogenicity. For antigenicity prediction, we used VaxiJen v2.0 (threshold ≥ 0.4) to determine the ability of the multi-epitope to elicit an immune response and the AllerTop v2.0 (

https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/) was used to evaluate its allergic properties.

2.9. Secondary Structure, Three Dimensional Structure Optimization and Verification

The secondary structure of the designed vaccine was predicted on the PSIPRED server (

http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/), which provided a range of protein structure prediction methods. The AlphaFold 3.0 server (

https://alphafoldserver.com/) was used to predict the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the vaccine that was developed. Afterward, the identified 3D structure underwent refinement via the GalaxyRefine web server (

http://galaxy.seoklab.org/refine). We identified the selected structure based on the lowest energy score and the highest RMSD value. The structure was visualized using PyMOL v2.5.7 following optimization and identification. Furthermore, the refined 3D mode of the designed vaccine was accessed through the Rampage website (

https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/) and the ProSA website (

https://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at/prosa.php), aiming to analyze the deviations from the average [

23].

2.10. Disulfide Engineering of the Designed Vaccine

The disulfide bonds usually play a crucial part in stabilizing protein folded state by reducing its structural disorderliness and enhancing its energetic stability. In order to enhance stability, the Disulfide by Design 2.0 website (

http://cptweb.cpt.wayne.edu/DbD2/) was used to predict the disulfide bonds of the constructed vaccine (accessed on February 21

th, 2025). The structure was used to scrutinize potential cysteine mutations, which resulted in the creation of disulfide bonds within the vaccine. The energy of residue pairs ≤ 2.2 kcal/mol was selected as the threshold [

23].

2.11. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was used to explain how model proteins bind with receptor molecules. As viral glycoproteins and dsRNA can always identify the toll-like receptors TLR4 (PDB ID: 2Z63) and TLR3 (PDB ID: 1ZIW), so that the two receptors were chosen as the immunological receptors. In this case, the refined model was submitted as a ligand for molecular docking with ClusPro v2.0 (

https://cluspro.bu.edu/). Before docking, water molecules in the ligand and receptor are removed, while hydrogen ions are added.

2.12. Molecular Dynamic (MD) Simulation

The iMODS tool (

http://imods.chaconlab.org/) was used for molecular dynamics simulations to examine the stability and physical movements of the vaccine-receptor docked complexes. This tool can use normal mode analysis (NMA) in the inner coordinates to predict the collective motions of proteins. The IMODS tool calculates the deformability, eigenvalues, variance, covariance plot, B-factor, and elastic network of vaccine-receptor complexes.

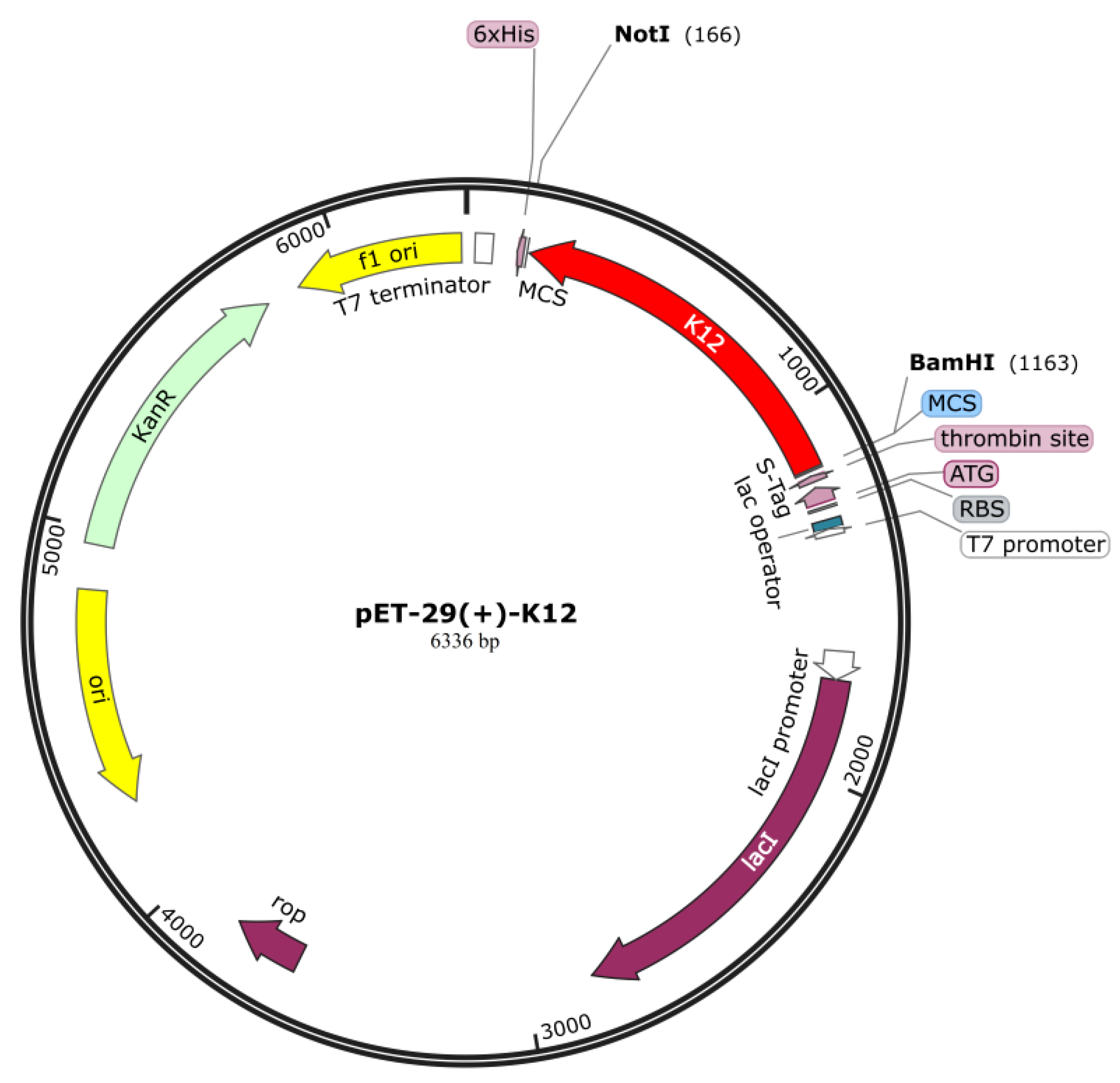

2.13. In silico Vaccine Cloning

Exerting maximum effect of codons which was optimized before can boost the production of vaccine antigens in the host. The EMBOSS Backtranseq (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/st/emboss_backtranseq) was utilized to translate the vaccine protein in reverse (accessed on February 24

th, 2025). The JCat website (

http://www.jcat.de/) was utilized to obtain the level of protein expression (accessed on February 24

th, 2025). We chose the

Escherichia coli K12 as the organism of host expression. We inferred the protein expression level through the CAI (codon adaptation index) and the GC content percentage. As reported, the score ≥ 0.8 generally signified a satisfactory score for CAI and the GC% was between 30%-70% which meant that the efficiency of gene translation and transcription is high [

24]. Finally, we modified the N-terminus and C-terminus of the vector by using restriction enzymes

NotI

and BamHI, respectively.

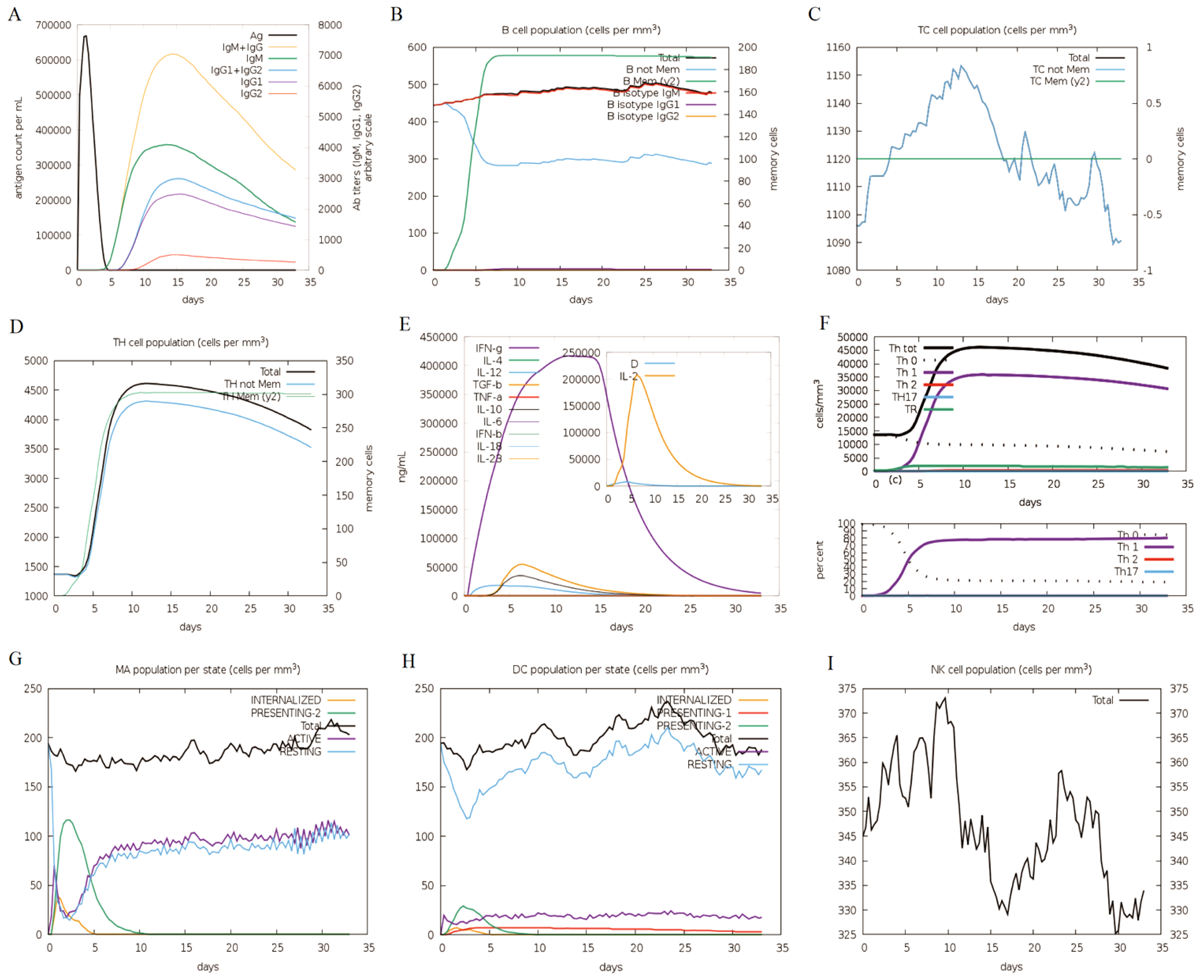

2.14. Immune Response Simulation

To assess the possible immune response to this vaccine, we further examined the vaccine through the C-ImmSim server (

https://150.146.2.1/C-IMMSIM/index.php). According to the previous studies [

25], two doses were given with at least a 30-day interval. In silico, we gave the injection at three time-steps such as 1, 84 and 168 where 8 hours per step in the real world.

3. Results

3.1. The Process of Vaccine Design

Antigenic peptide vaccines consist of T-cell epitopes. The structural proteins including HMW1 (n = 10), HMW2 (n = 10), HMW3 (n = 10) and p1-adhesin protein (n = 4) were selected and downloaded from NCBI (

Figure 1A), and the vaccine design process was shown in

Figure 1B. Initially, the HMW1-3 and p1-adhesin proteins were chosen and aligned to maintain sequence consistency. The generated consensus sequence showed 99.71%, 99.94%, 99.85% and 96.46% sequence similarity with the reference proteins such as HMW1 (WP_010874803.1), HMW2 (WP_010874666.1), HMW3 (WP_010874808.1) and p1-adhesin (WP_010874498.1), respectively. Then the consensus sequences were chosen to predict the putative T cell epitopes for the vaccine design. The vaccine design logic is to first connect the CTL epitope, and then connect the HTL epitope. The adjuvant should be connected at the N-terminus, and AAY linkers were used to connect the CTL epitopes, while GPGPG linkers were used to connect the HTL epitopes (

Figure 1C), which were then used for further vaccine evaluation.

The IEDB website (

http://tools.iedb.org/) were utilized to identify potential CTL and HTL epitopes from the structural proteins of

M. pneumoniae. A total of 350 CTL epitopes with 9-mer core sequences were identified in the chosen HMW1-3 and p1-adhesin proteins. The choice of immunogen or epitope is the initial step for effective vaccine design; henceforth, to find out the most probable antigenic protein, the protein sequences of

M. pneumoniae were retrieved for dataset construction. Further evaluation revealed that 16 optimal CTL epitopes showed high antigenicity, immunogenicity, non-toxicity and non-allergenicity, which were selected for the final vaccine development (

Table 1). Similarly, a total of 1,271 HTL epitopes with 15-mer core sequences were identified by using the IEDB server. Among them, only 7 optimal HTL epitopes triggered the production of 3 specific cytokines: IFN-γ, IL4, and IL10, which were selected for the ultimate vaccine design as

Table 1 shown.

Finally, the constructed vaccine was comprised of 329 amino acids, which was designed based on 23 epitopes, including 16 CTL epitopes and 7 HTL epitopes, respectively (

Table 1;

Figure 1B).

3.2. Global Population Coverage

The chosen CTL and HTL epitopes were assessed the population coverage as shown in

Table 1. As a whole, 90.57% population coverage of the CTL and HTL epitopes was observed worldwide. The global average population coverage of CTL epitopes is 78.43%, while HTL epitopes is 56.31% (

Figure 2A). The selected epitopes engaged with numerous HLA alleles across various geographical areas, including the United States (91.69%), North America (91.4%), East Asia (77.49%), Northeast Asia (78.04%), and Europe (95.54%) (

Figure 2B). The high global population coverage indicates that the designed vaccines with these epitopes may be effective for the majority of the global population.

3.3. Physicochemical Properties and Immunological Evaluation

We assessed the vaccine’s physical and chemical characteristics without any adjuvant linkage. The results showed that the molecular weight of the vaccine was 35,714.85 Da, the antigenicity score was 0.65 (reference value: 0.4), and the immunogenicity score was 6.26, indicating a pronounced antigen and considerable immunogenicity (

Table 2). Moreover, other characteristics were assessed, such as the pI of theoretical isoelectric point (4.71), the index of instability (29.59), the index of aliphatic (71.46), grand average of hydropathicity (-0.234) and the scaled solubility (0.49), revealing a high solubility and hydrophilicity (

Table 2).

3.4. Secondary and 3D Structure, Verification and Optimization

The secondary structure of the vaccine such as β-strand, α-helix and random coils was conducted on the PSIPRED server. The results showed that its secondary structure comprised 14.89% (49/329) α-helix, 8.21% (27/329) β-strand, and 76.90% (253/329) random coils (

Table 2).

Furthermore, the 3D structure of the vaccine was refined for assessment and verification (

Figure 3A). The Ramachandran plot for the improved vaccine model showed that 87.9% of the residues were in favorable regions, 12.1% were in allowed regions, and none were in non-allowed regions (

Figure 3B). Similarly, the entire quality of model was indicated by the indicator of

Z-score generated by the ProSA server. The area of NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) spectroscopy and X-radiation was similar with the

Z-score, pointing to outstanding structural quality. The results showed that the

Z-score of the refined model was -1.9 (

Figure 3C), corresponding more closely to the areas generated by NMR and X-rays.

3.5. Disulfide Engineering

Disulfide bonds enhance the stability of numerous extracellular and secreted proteins by reducing their conformational entropy and increasing the free energy of their denatured state, thereby stabilizing their folded forms [

26]. Leaning on disulfide bonds established between the residues, the stability of the vaccine’s structure was maintained. After we investigated with the Disulfide by Design 2.0 website (

http://cptweb.cpt.wayne.edu/DbD2/), the result indicated that in the vaccine construct contained 9 potential residue pairs which had the potential for forming disulfide bonds as shown in

Table 3. The pair of Glu16-Asp41 (residue pair and 1.77 kcal/mol) could be mutated with the lowest threshold score (< 2.2 kcal/mol) [

26] (

Figure 4).

3.6. Molecular Docking

The vaccines served as ligand for molecular docking with the TLR4/3 receptors to predict their interactions and binding affinities. In this scenario, 30 docked complexes with various poses were generated by the ClusPro (version 2.0) server. Finally, only model 3 satisfied the required standards due to its lowest energy score. The result showed that the optimal vaccine-TLR4 compound had a score (-1276.2) of energy (

Figure 5A), indicating that the vaccine-TLR4 compound had a compact conformation and stable binding interactions.

An analysis was conducted on the binding interactions of the selected complex, as well as an exploration of its involvement in active site residues. The interplay between 4 Van der Waals and 2 hydrogen bonds were displayed by vaccine-TLR3 compound in interaction plane. The Glu111 and Asp220 residues of the vaccine can form hydrogen bonds with the Thr483 and Ser12 residues of TLR3. Similarly, as to the van der Waals, the Glu87, Arg74, Lys587 and Asp220 residues of vaccine could interact strongly with the His539, Glu7, His13 and Glu16 residues of the TLR3 receptor (

Figure 5B).

3.7. Molecular Simulation Analysis

The MD simulation of iMODS was used to check the stability and motion of docking complexes. The slow kinetics of docking complexes and demonstrated their large amplitude conformational changes were analyzed using the normal mode analysis (NMA). The results showed that the receptor and ligand tended to cluster together (

Figure 6A), and the covariance map showed that the binding region covered many red colors, indicating that the key region of the protein had coordinated amino acid movement and stable ligand binding (

Figure 6B). The deformability built up the independent distortion of each residue portrayed by the method of chain hinges (

Figure 6C). The overall binding peak of the vaccine-TLR4 complex is moderate, indicating a certain degree of flexibility, but it will not be excessively twisted, which is a good manifestation of docking results. After docking, the B-factor fluctuated within a reasonable range without affecting the natural movement pattern of the protein (

Figure 6D). Eigenvalue, which is a crucial parameter of a stable structure, must be high to have a stable complex. The eigenvalue determined for the complex was found to be 3.36E-5 with the variance of each typical mode being gradually decreased (

Figure 6E-F). These rates are significantly higher for structural stability. The moderate eigenvalues indicated that the protein maintained its biological activity after binding and adapted to ligand binding.

3.8. Codon Optimization and Vaccine Cloning

To ensure high-level expression and ease of production of vaccines, codon optimization is performed through JCat servers. The cDNA length of the designed vaccine is 990 bp with a stop codon being added in the end of the cDNA. The CAI value (score: 1) and GC content (55.72%) of the vaccine are both ideal, indicating the possibility of high gene expression potential and excellent expression ability in the type strain

Escherichia coli K12. Finally, the cDNA sequence of the vaccine was cloned into the pET291a (+) vector with SnapGene v5.2.3 (

Figure 7).

3.9. Vaccine Immune Response Simulation

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the immune response simulation mirrors the real immune phenomenon induced by specific pathogens. The immune system showed increased levels of antibodies, such as IgM and IgG+ IgM, reaching a peak between 10 and 15 days. In this case, it suggested that continuous exposure improved antigen elimination, aligning with the observed decrease in antigen levels (

Figure 8A). Additionally, the survival time of B cells, cytotoxic T cells and helper T cells was prolonged, indicating a transition from immune cells to IgM memory generation as

Figure 8B-D shown. After five days, the memory of B cells started to rise, while the non-memory of B cells decreased until reaching a stable state five days later as shown in

Figure 8B. The fluctuating changes occurred in the non-memory area of Tc cells, reaching their peak between 10 and 15 days (

Figure 8C). At the same time, Th cells significantly increased after the immune response, with the peak occurring on the tenth day (

Figure 8D). Moreover, it was noted that the IFN-γ levels had increased significantly (

Figure 8E). The quantity and percentage of the Th0-type immune response declined compared to the Th1-type response (

Figure 8F). After immunization, there was a significant rise in Th1 cells, reaching its peak on the tenth day. Conversely, the number of Th0 cells decreased significant, reaching its lowest point on the fifth day, followed by a stabilization (

Figure 8F). It displayed a rising trend in movement of macrophage, while dendritic cell migration was predictable (

Figure 8G-H). Conversely, the count of natural killer (NK) cells varied and peaked on the tenth day (

Figure 8I).

4. Discussion

The

M. pneumoniae was a major cause of lower respiratory tract infections in both newborns and older people with weakened immune systems. Currently, there is no effective vaccine for treating the Mp infection. Contemporary immunoinformatics tools offered a practical and efficient alternative to traditional vaccine development, providing a less labor-intensive screening method [27−28]. Vaccines have consistently demonstrated high safety and efficacy in preventing infectious diseases, offering acquired immunity against diseases [29−30]. An ideal target should be very conservative, capable of inducing neutralizing cellular immunity and producing antibodies against

M. pneumoniae, which is more important for the development of effective pneumonia vaccines. The membrane associated proteins and cell adhesion proteins of

M. pneumoniae are extensively produced during disease progression and exhibit strong conservation and immunogenicity, making them the optimal immunogens for triggering humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. Due to the continuous mutations of the wild-type viruses, this study aimed to develop an T cell epitope-based vaccine, providing cross-protection against various wild-types. If T cell epitopes have a nice conservation in the selected protein, they are considered strong and effective. Although vaccines have the potential to act as a preventive tool for future epidemic occurrences, developing effective broad-spectrum vaccines remains a challenging task in the current scenario. Thus, it became clear that a novel approach to vaccine development was necessary to find solutions to pressing public health threats. Given the established roles of HMW1-3 and p1-adhesin as critical determinants of immune evasion and interhuman transmission, this investigation prioritized the engineering of a multi-epitope vaccine construction [31−32]. That involved generating consensus sequences of the target structural proteins through rigorous multiple sequence alignment (MSA) to maximize coverage of evolutionarily conserved residues across prevalent clinical isolates, thereby targeting immunodominant epitopes with high population coverage frequencies. Furthermore, we aimed to identify the surface antigen regions of antigens that facilitated recognition by the systems of the humoral immune and cellular. Here, we employed an immunoinformatic driven approach to screen for significant dominant immunogens against

M. pneumoniae, and the results indicated that all membrane-bound proteins and cell adhesion proteins had a nice antigenicity, with the highest antigen scores. All possible epitopes of HTL and CTL should be identified and assessed at the initial step. The elimination of the amount of virus present depended on a response of the cell (CD8+ T) initiated by the host. The research relating to the cells (CD8+ T) infected between humans and mice with

M. pneumoniae was scarce [33−34]. The epitopes that triggered strong and effective CTL responses deserve thorough study and are promising candidates for antiviral vaccine development. The evaluation including epitopes (HTL and CTL) and required linkers was carried out using an integrated ranking process in the ultimate vaccine. The process of developing the vaccine was crucial in order to enhance expression of profiles, folding properties of vaccine and stability. The vaccine’s stability and durability were increased by linking the adjuvants and epitopes of CTL via the EAAAK linkers, which assisted in eliciting strong cellular and humoral immunity targeting particular antigens [35−36]. However, in this study, we did not evaluate the vaccine efficacy after connecting adjuvant, as different adjuvant may have different effects on vaccine efficacy. The properties of vaccine proteins themselves seem to be a more concerning issue, which can help to make reasonable adjustments to the designed vaccine. In addition, solubility was the essential physicochemical property of any potential vaccine, making it a vital feature of recombinant vaccines [

37]. As a result, solubility assessment tools can be used to predict the solubility quality of vaccines. The solubility of the vaccine construct was confirmed by this methodology. The vaccine properties were found to be acidic based on the theoretical pI values. The server tool suggests that this protein will maintain its stability after being synthesized, as indicated by the unsteadiness index. Oppositely, the vaccines could withstand high temperatures and were hydrophilic, which is supported by the value of GRAVY and the index of lipids. The predicted favorable physicochemical properties and positive parameter scores of the designed vaccine indicated a high likelihood of being an effective candidate against infections.

With the methods in this study, the global coverage rate of the best population has reached to 90.57%, thus, the designed vaccine will become a probably high-promising competitor. The Ramachandran plot is used to evaluate the rationality of protein conformation, which does not consider energy issues and only evaluates whether the conformation is reasonable. The evaluation of the model quality after homology modeling shows that the proportion of amino acid residues falling within the allowed and maximum allowed regions is close to 90%, indicating that the conformation of the model is reasonable. In addition, after molecular docking, the peptide vaccine shows potential for inhibiting infection by interacting with TLR3/TLR4, a favorable receptor. The model of vaccine may act as a ligand by means of a significant interaction occurring on the surface of the TLR3/TLR4 receptor. Furthermore, the vaccine-TLR4 docked complex was also subjected to MD simulation to determine its stability. The results revealed that the vaccine can adapt to the ligand without drastic fluctuations, showing a stable binding force. The CAI value and GC content are used to evaluate the effectiveness of the vaccine development process. The designed vaccine is predicted to be expressed well in the system of E. coli K12. In addition, we conducted immune simulation experiments and determined the optimal immune response to pathogens. It was predicted that the immune system could be activated by the increasing dosage of vaccine, causing the memory B cells and T cells to multiply. The activation of HTL will continue to expand following immunization, leading to the generation of IL-2 and IFN-γ. As a result, the designed vaccine was predicted to successfully boost the humoral immune response, causing an increase in immunoglobulin levels. Nevertheless, further experimental studies are still needed to substantiate the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing the M. pneumoniae infection.

5. Conclusions

Immunogenic epitope analysis provided a crucial insight that guided the creation of vaccines that were both safe and effective, capable of triggering strong and wide-ranging immune responses. In this study, the consensus sequences were used to predict potential T cell epitopes from structural proteins, ensuring the breadth and conservation of the antigens. The widely-protective vaccine was designed to have promising immune dominance traits, wide population reach, and the ability to effectively interact with TLR3 or TLR4 immune receptors, leading to a strong immune response after viral infection. The designed multi-epitope vaccine is the antigen with structurally stability, high solubility, high immunogenicity and non toxin, which is a candidate vaccine with great application prospects.

Author Contributions

Lingling Chen: Writing - original draft, Investigation. Yang Li: Software, Data curation, Formal analysis. Xiao Jiang: Formal analysis. Henan Cao: Formal analysis. Shulei Jia: Conception, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Youth Fund of the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (24JCQNJC00460).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The computational requirements of this work were supported by the High-performance Computing Platform of Tianjin Medical University, and the China Academy of Aerospace Electronics Technology company.

References

- GBD 2021 Lower Respiratory Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, 974–1002.

- Fu S, Jia W, Li P, Cui J, Wang Y, Song C. Risk factors for pneumonia among children with coinfection of influenza A virus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024, 43, 1437-1444. [CrossRef]

- He Y, He X, He N, Wang P, Gao Y, Sheng J, Tang J. Epidemiological trends and pathogen analysis of pediatric acute respiratory infections in Hanzhong Hospital, China: Insights from 2023 to 2024. Front Public Health. 2025, 13, 1557076. [CrossRef]

- Urbieta AD, Barbeito Castiñeiras G, Rivero Calle I; et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae at the rise not only in China: Rapid increase of Mycoplasma pneumoniae cases also in Spain. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2332680. [CrossRef]

- Rowlands RS, Meyer Sauteur PM, Beeton ML, On Behalf Of The Escmid Study Group For Mycoplasma And Chlamydia Infections Esgmac. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Not a typical respiratory pathogen. J Med Microbiol. 2024, 73, 001910.

- Hu J, Ye Y, Chen X, Xiong L, Xie W, Liu P. Insight into the Pathogenic Mechanism of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Curr Microbiol. 2022, 80, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang XB, He W, Gui YH; et al. Current Mycoplasma pneumoniae epidemic among children in Shanghai: Unusual pneumonia caused by usual pathogen. World J Pediatr. 2024, 20, 5-10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Kumar S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Among the smallest bacterial pathogens with great clinical significance in children. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2023, 46,100480.

- Fonsêca MM, da Zaha A, Caffarena ER, Vasconcelos ATR. Structure-based functional inference of hypothetical proteins from Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Mol Model. 2012, 18,1917-1925. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Kang H, Dou H; et al. Comparative genomic sequencing to characterize Mycoplasma pneumoniae genome, typing, and drug resistance. Microbiol Spectr. 2024, 12,e0361523.

- Xu M, Li Y, Shi Y, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children, Wuhan, 2020-2022. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24,23.

- Berry IJ, Widjaja M, Jarocki VM; et al. Protein cleavage influences surface protein presentation in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Sci Rep. 2021, 11,6743. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry R, Varshney AK, Malhotra P. Adhesion proteins of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Front Biosci. 2007, 12:690-699. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Luo Y, Li L; et al. Immune response plays a role in Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Front Immunol. 2023, 14:1189647. [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulou VE, Lempesis IG, Sklapani P; et al. Exploring the pathogenetic mechanisms of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2024, 28,271. [CrossRef]

- Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS; et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: Clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 53, e25-76.

- Okada T, Morozumi M, Tajima T; et al. Rapid effectiveness of minocycline or doxycycline against macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a 2011 outbreak among Japanese children. Clin Infect Dis. 2012, 55,1642-1649. [CrossRef]

- Eshaghi A, Memari N, Tang P; et al. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in humans, Ontario, Canada, 2010–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013, 19.

- Peuchant O, Ménard A, Renaudin H; et al. Increased macrolide resistance of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in France directly detected in clinical specimens by real-time PCR and melting curve analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009, 64,52-58. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Li S, Zhu C; et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections: Pathogenesis and vaccine development. Pathogens. 2021, 10,119. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Yu X. An introduction to epitope prediction methods and software. Rev Med Virol. 2009, 19,77-96. [CrossRef]

- Farhadi T, Nezafat N, Ghasemi Y; et al. Designing of complex multi-epitope peptide vaccine based on omps of Klebsiella pneumoniae: An in silico approach. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2015, 21,325-341. [CrossRef]

- 23. Guan P, Qi C, Xu G; et al. Designing a T cell multi-epitope vaccine against hRSV with reverse vaccinology: An immunoinformatics approach. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2025, 251:114599. [CrossRef]

- Fu H, Liang Y, Zhong X; et al. Codon optimization with deep learning to enhance protein expression. Sci Rep. 2020, 10,17617. [CrossRef]

- Stolfi P, Castiglione F, Mastrostefano E; et al. In-silico evaluation of adenoviral COVID-19 vaccination protocols: Assessment of immunological memory up to 6 months after the third dose. Front Immunol. 2022,13:998262. [CrossRef]

- Craig DB, Dombkowski AA. Disulfide by Design 2.0: A web-based tool for disulfide engineering in proteins. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013, 14:346. [CrossRef]

- Rapin N, Lund O, Bernaschi M, Castiglione F. Computational immunology meets bioinformatics: The use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5,e9862. [CrossRef]

- Rappuoli R, Bottomley MJ, D’Oro U; et al. Reverse vaccinology 2.0: Human immunology instructs vaccine antigen design. J Exp Med. 2016, 213,469-481. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Joshi MD, Singhania S; et al. Peptide Vaccine: Progress and Challenges. Vaccines (Basel). 2014, 2,515-536. [CrossRef]

- Bol KF, Aarntzen EH, Pots JM; et al. Prophylactic vaccines are potent activators of monocyte-derived dendritic cells and drive effective anti-tumor responses in melanoma patients at the cost of toxicity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016, 65,327-339. [CrossRef]

- Willby MJ, Balish MF, Ross SM; et al. HMW1 is required for stability and localization of HMW2 to the attachment organelle of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186,8221-8228. [CrossRef]

- Shams M, Nourmohammadi H, Majidiani H; et al. Engineering a multi-epitope vaccine candidate against Leishmania infantum using comprehensive Immunoinformatics methods. Biologia (Bratisl). 2022, 77,277-289. [CrossRef]

- Volkers SM, Meisel C, Terhorst-Molawi D; et al. Clonal expansion of CD4+CD8+ T cells in an adult patient with Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated Erythema multiforme majus. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021, 17,17. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood M, Javaid A, Shahid F, Ashfaq UA. Rational design of multimeric based subunit vaccine against Mycoplasma pneumonia: Subtractive proteomics with immunoinformatics framework. Infect Genet Evol. 2021, 91:104795. [CrossRef]

- Bonam SR, Partidos CD, Halmuthur SKM, Muller S. An Overview of Novel Adjuvants Designed for Improving Vaccine Efficacy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017, 38,771-793.

- Samad A, Ahammad F, Nain Z; et al. Designing a multi-epitope vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: An immunoinformatics approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022, 40,14-30. [CrossRef]

- Khatoon N, Pandey RK, Prajapati VK. Exploring Leishmania secretory proteins to design B and T cell multi-epitope subunit vaccine using immunoinformatics approach. Sci Rep. 2017, 7,8285. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The pipeline of the Mp vaccine construction. (A): The structural proteins of M. pneumoniae. (B): The process of constructing a multi-epitope vaccine. (C): The candidate T cell vaccine was structurally designed by combining CTL and HTL epitopes with the C-terminus of the vaccine being added with 6 × His (histidine).

Figure 1.

The pipeline of the Mp vaccine construction. (A): The structural proteins of M. pneumoniae. (B): The process of constructing a multi-epitope vaccine. (C): The candidate T cell vaccine was structurally designed by combining CTL and HTL epitopes with the C-terminus of the vaccine being added with 6 × His (histidine).

Figure 2.

The global distribution and coverage of total epitopes, HTL epitopes and CTL epitopes (A). The regional population coverage of Europe, North America and Northeast Asia (B).

Figure 2.

The global distribution and coverage of total epitopes, HTL epitopes and CTL epitopes (A). The regional population coverage of Europe, North America and Northeast Asia (B).

Figure 3.

The tertiary structure of the multi-epitope vaccine has been validated. (A): The optimized 3D structure of the vaccine. (B): The statistics of Ramachandran plot, indicating the most acceptable, disallowed and favorable regions. (C): The ProSA-web result, with a Z-score of -1.9 for the optimized vaccine model.

Figure 3.

The tertiary structure of the multi-epitope vaccine has been validated. (A): The optimized 3D structure of the vaccine. (B): The statistics of Ramachandran plot, indicating the most acceptable, disallowed and favorable regions. (C): The ProSA-web result, with a Z-score of -1.9 for the optimized vaccine model.

Figure 4.

Disulfide bond design in the multi-epitope vaccine. The mutant variant features Glu16 and Asp41 (a pair of amino acids) that have been mutated into cysteine residues, which form disulfide bonds represented by yellow sticks.

Figure 4.

Disulfide bond design in the multi-epitope vaccine. The mutant variant features Glu16 and Asp41 (a pair of amino acids) that have been mutated into cysteine residues, which form disulfide bonds represented by yellow sticks.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking of the multi-epitope vaccine with TLR4 molecules was performed, and the model with the lowest energy was selected as the optimal binding mode (A). Additionally, molecular docking of the multi-epitope vaccine with TLR3 molecules is shown in a three-dimensional diagram (B). The yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds, while the red dashed lines represent van der Waals forces.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking of the multi-epitope vaccine with TLR4 molecules was performed, and the model with the lowest energy was selected as the optimal binding mode (A). Additionally, molecular docking of the multi-epitope vaccine with TLR3 molecules is shown in a three-dimensional diagram (B). The yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds, while the red dashed lines represent van der Waals forces.

Figure 6.

Molecular dynamics simulation of the vaccine-TLR4 complex. (A): Affine-arrows of the vaccine-TLR4 complex; (B): Covariance map of the complex. Covariance matrix indicates coupling between pairs of residues, i.e. whether they experience correlated (red), uncorrelated (white) or anti-correlated (blue) motions. (C): Deformability index; (D): B-factor column; (E-F): Eigenvalue and NMA variance.

Figure 6.

Molecular dynamics simulation of the vaccine-TLR4 complex. (A): Affine-arrows of the vaccine-TLR4 complex; (B): Covariance map of the complex. Covariance matrix indicates coupling between pairs of residues, i.e. whether they experience correlated (red), uncorrelated (white) or anti-correlated (blue) motions. (C): Deformability index; (D): B-factor column; (E-F): Eigenvalue and NMA variance.

Figure 7.

The designed vaccine was virtually cloned into the pET-29a (+) vector using in-silico methods: the recombinant product, with the vaccine construct inserted and highlighted in red within the vector, is shown.

Figure 7.

The designed vaccine was virtually cloned into the pET-29a (+) vector using in-silico methods: the recombinant product, with the vaccine construct inserted and highlighted in red within the vector, is shown.

Figure 8.

The designed vaccine elicits an immune response. (A): The immune responses, (B): B cell population, (C): Tc cell population, (D): Th cell population, (E): Induction of cytokines and interleukins, (F): Immune response of Th1 and Th0, (G): Macrophage (MA) population per state, (H): DC (dendritic cell) population per state, (I): NK cell population.

Figure 8.

The designed vaccine elicits an immune response. (A): The immune responses, (B): B cell population, (C): Tc cell population, (D): Th cell population, (E): Induction of cytokines and interleukins, (F): Immune response of Th1 and Th0, (G): Macrophage (MA) population per state, (H): DC (dendritic cell) population per state, (I): NK cell population.

Table 1.

Overall of the HTL and CTL epitopes selected to construct the candidate vaccine (%percentile rank: MHC I < 0.5%, MHC II < 10%).

Table 1.

Overall of the HTL and CTL epitopes selected to construct the candidate vaccine (%percentile rank: MHC I < 0.5%, MHC II < 10%).

| Pprotein |

GRAVY |

Peptides |

Length |

Location |

Alleles |

Antigenicity score |

Class I immunogenicity |

IFN-γ score |

IL-4 prediction |

IL-10 prediction |

Population coverage |

| CTL epitopes |

| HMW1 |

-0.04 |

SLDPIGETA |

9 |

256-265 |

HLA-A*02:01 |

0.87 |

0.26 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

39.08% |

| -0.24 |

LQPEPVTEV |

9 |

290-299 |

HLA-A*02:01 |

1.14 |

0.22 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

39.08% |

| 0.56 |

TIAEITPQV |

9 |

326-335 |

HLA-A*26:01 |

0.98 |

0.20 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

5.82% |

| 0.22 |

AINFDDIFK |

9 |

746-755 |

HLA-A*11:01 |

0.47 |

0.34 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

15.53% |

| -1.02 |

KLDDFDFET |

9 |

982-991 |

HLA-A*02:01 |

1.81 |

0.32 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

39.08% |

| HMW2 |

-0.90 |

SRYANWADF |

9 |

133-142 |

HLA-B*27:05 |

1.89 |

0.29 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

4.78% |

| -1.26 |

KRREIDDLL |

9 |

421-430 |

HLA-B*27:05 |

1.13 |

0.28 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

4.78% |

| -0.10 |

FLEGEFNHL |

9 |

590-599 |

HLA-A*02:01 |

0.61 |

0.29 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

39.08% |

| -0.37 |

ASKERILDF |

9 |

738-747 |

HLA-B*08:01 |

1.08 |

0.21 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

10.55% |

| 0.31 |

TEELEAAFL |

9 |

836-845 |

HLA-B*40:01 |

0.76 |

0.26 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

7.81% |

| 0.84 |

ELKIAFADL |

9 |

919-928 |

HLA-B*08:01 |

1.92 |

0.26 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

10.55% |

| -1.43 |

NLAEREREI |

9 |

1539-1548 |

HLA-B*08:01 |

1.43 |

0.36 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

10.55% |

| -0.90 |

YPYPYPWFY |

9 |

1622-1631 |

HLA-A*01:01 |

0.95 |

0.23 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

17.34% |

| HMW3 |

0.98 |

APVVEPTAV |

9 |

287-296 |

HLA-B*07:02 |

0.63 |

0.20 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

12.78% |

| p1 |

-0.20 |

KADDFGTAL |

9 |

334-343 |

HLA-B*39:01 |

0.90 |

0.23 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

2.75% |

| -0.08 |

YVPWIGNGY |

9 |

811-820 |

HLA-A*26:01 |

0.53 |

0.40 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

5.82% |

| HTL epitopes |

| HMW1 |

-1.00 |

DYLQYVGNEAYGYYD |

15 |

105-120 |

HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB1*09:01 |

0.49 |

N/A |

0.91 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

17.24% |

| -0.97 |

RSLSNDFTIAHRPSD |

15 |

825-840 |

HLA-DRB1*03:01 |

0.81 |

N/A |

0.47 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

17.84% |

| -0.37 |

KNIQITLKELKAVYK |

15 |

866-881 |

HLA-DRB1*03:01 |

1.37 |

N/A |

0.47 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

17.84% |

| HMW2 |

-0.54 |

ARTQFDNRVSLLSAR |

15 |

608-623 |

HLA-DRB1*03:01 |

1.21 |

N/A |

0.23 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

17.84% |

| -0.53 |

QSQPAFLATQQSISK |

15 |

1780-1795 |

HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB1*01:01 |

0.61 |

N/A |

0.30 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

22.06% |

| HMW3 |

0.68 |

TPIASRFTGVTPMAV |

15 |

573-588 |

HLA-DRB1*01:01, HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01, HLA-DRB1*09:01 |

0.52 |

N/A |

0.49 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

43.06% |

| p1 |

-0.48 |

WAPRPWAAFRGSWVN |

15 |

1160-1175 |

HLA-DRB1*09:01 |

0.68 |

N/A |

0.98 |

IL4-inducer |

IL10-inducer |

6.40% |

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties, immunogenicity and secondary structure of the multi-epitope vaccine.

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties, immunogenicity and secondary structure of the multi-epitope vaccine.

| Physical and Chemical Properties |

Instability and Theoretical pI |

Immuno-Reactivity |

Secondary Structure |

| Number of amino acids: 329 |

Instability index (II): 29.59 |

Non-allergen |

α-helix: 14.89% (49/329) |

| Molecular weight: 35,714.85 |

Aliphatic index: 71.46 |

Immunogenicity: 6.26 |

β-strand: 8.21% (27/329) |

| Predicted scaled solubility: 0.49 |

Theoretical pI: 4.71 |

Antigen: 0.65 |

Random coils: 76.90% (253/329) |

|

Grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY): -0.234 |

Table 3.

List of residue pairs in the constructed vaccine that are capable of forming disulfide bonds, along with their energy scores and chi 3 (dihedral angles).

Table 3.

List of residue pairs in the constructed vaccine that are capable of forming disulfide bonds, along with their energy scores and chi 3 (dihedral angles).

| Res 1 AA |

Res 2 AA |

Chi 3 |

Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Glu16 |

Asp41 |

111.3 |

1.77 |

| Lys49 |

Lys73 |

110.15 |

5.68 |

| Ala64 |

Ala67 |

-96.01 |

5.74 |

| Glu76 |

Lys99 |

81.87 |

2.89 |

| Asn133 |

Ala157 |

123.1 |

7.41 |

| Pro148 |

Asp171 |

-68.8 |

4.45 |

| Tyr208 |

Ser228 |

119.26 |

9.2 |

| Phe259 |

Ala279 |

96.97 |

6.25 |

| Asn261 |

Ser264 |

-110.29 |

4.74 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).