Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

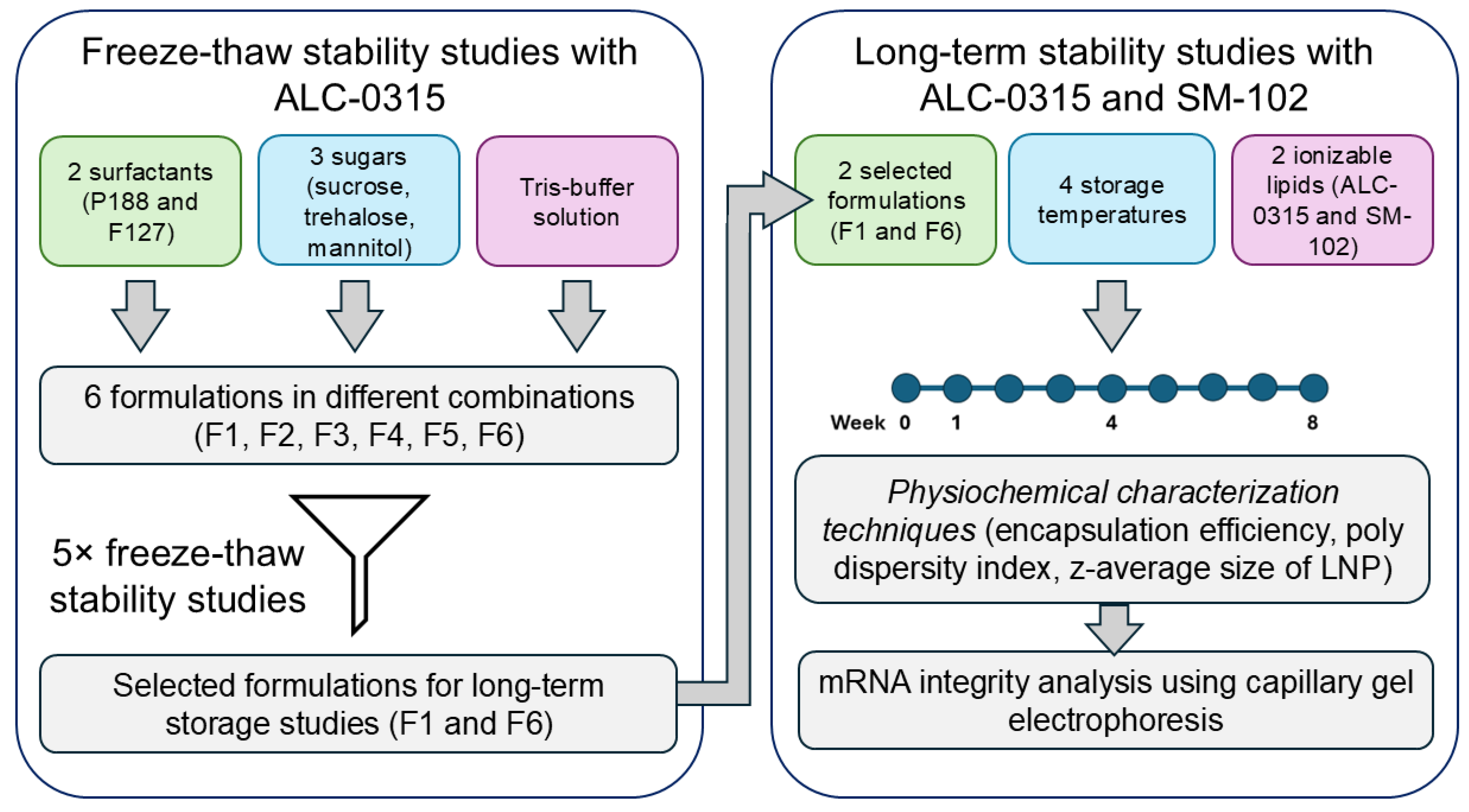

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. mRNA Synthesis and Purification

2.2. Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation

2.3. Freeze-Thaw Studies

2.4. Long-Term Storage

2.5. mRNA-LNP Characterization

2.6. Capillary Electrophoresis for mRNA Integrity

3. Results

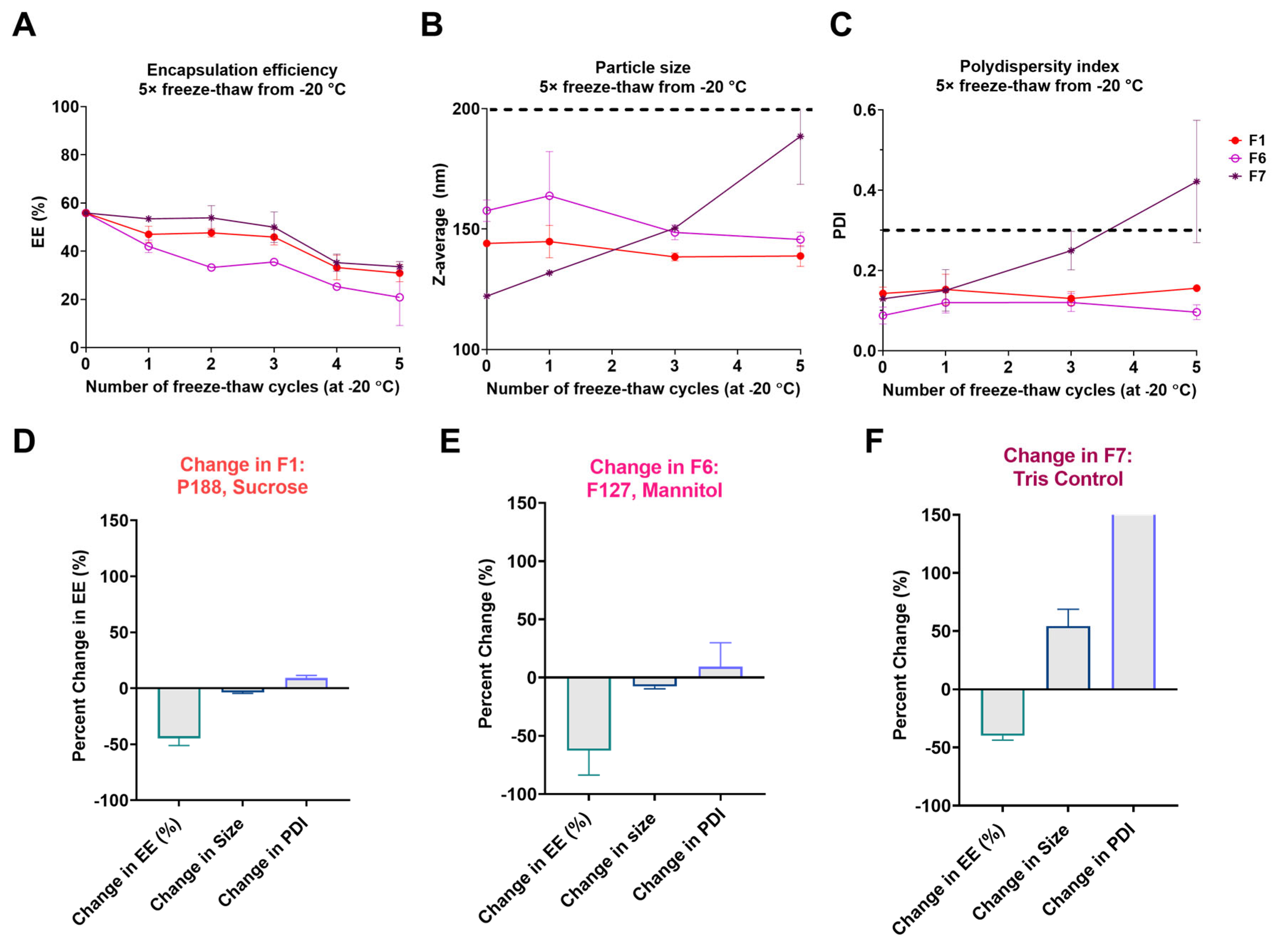

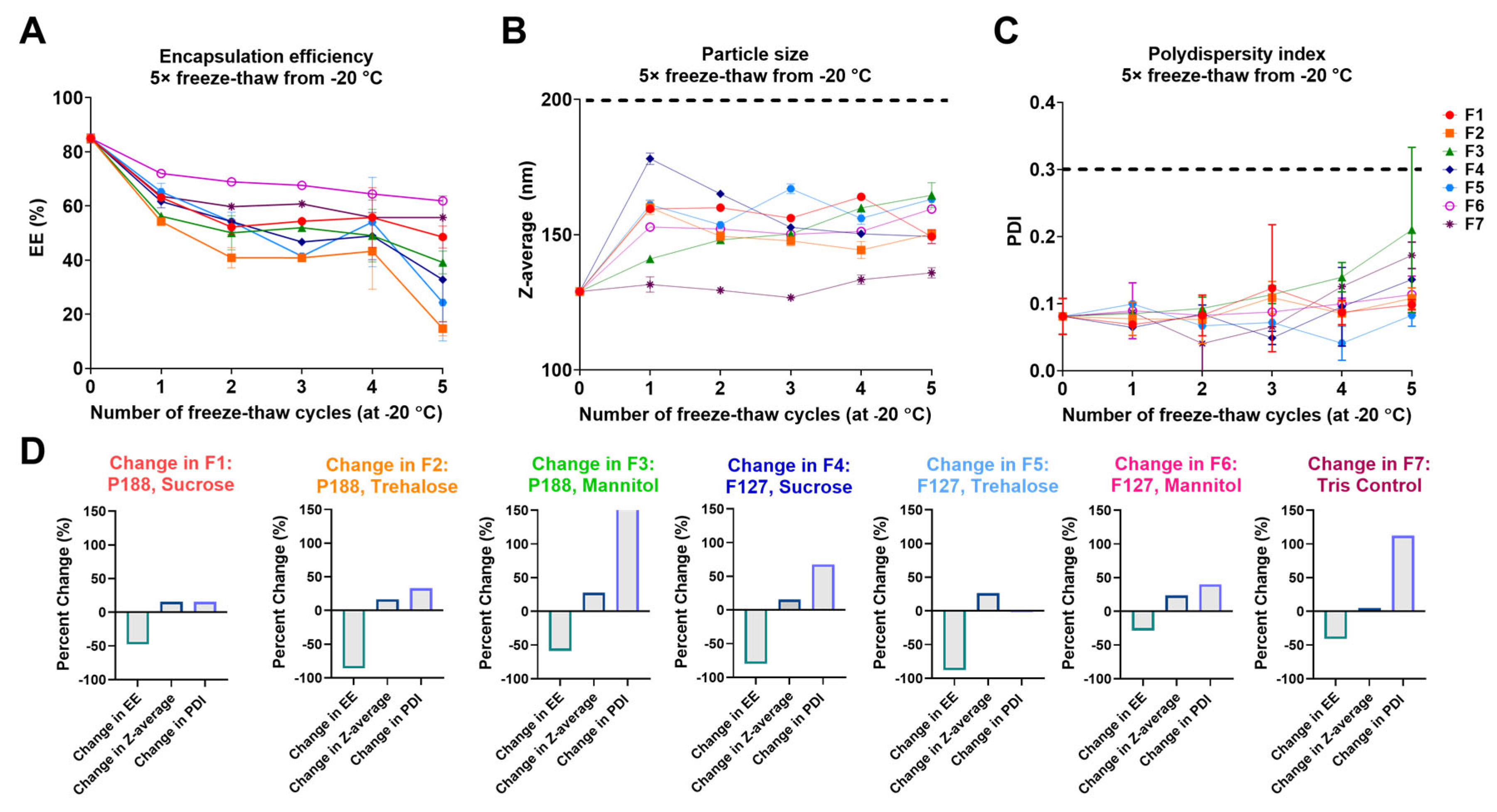

3.1. Screening LNP Buffer-Excipient Formulations by Freeze-Thaw Cycles

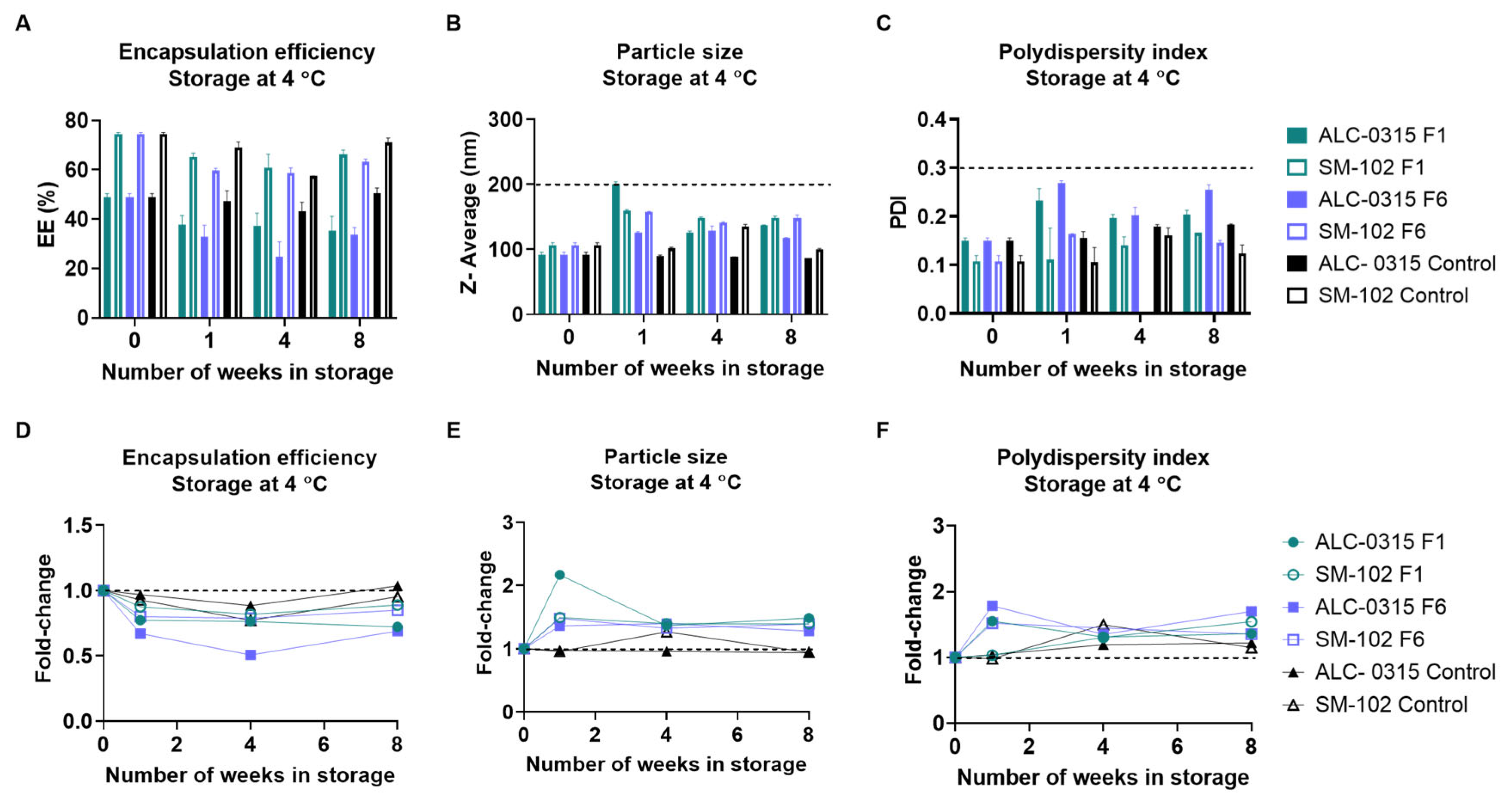

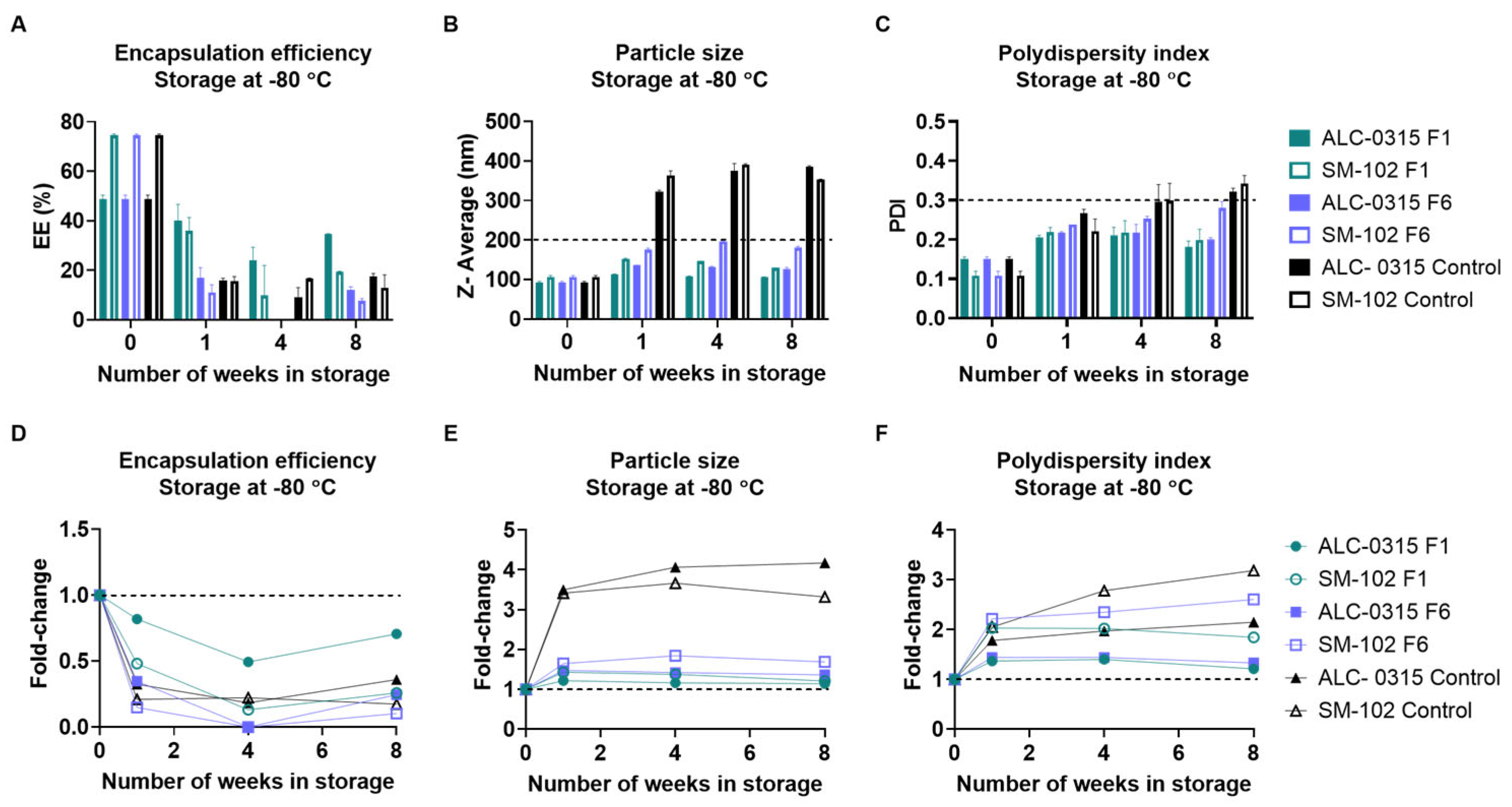

3.2. Long-Term Stability Assessment of nLuc mRNA-LNPs

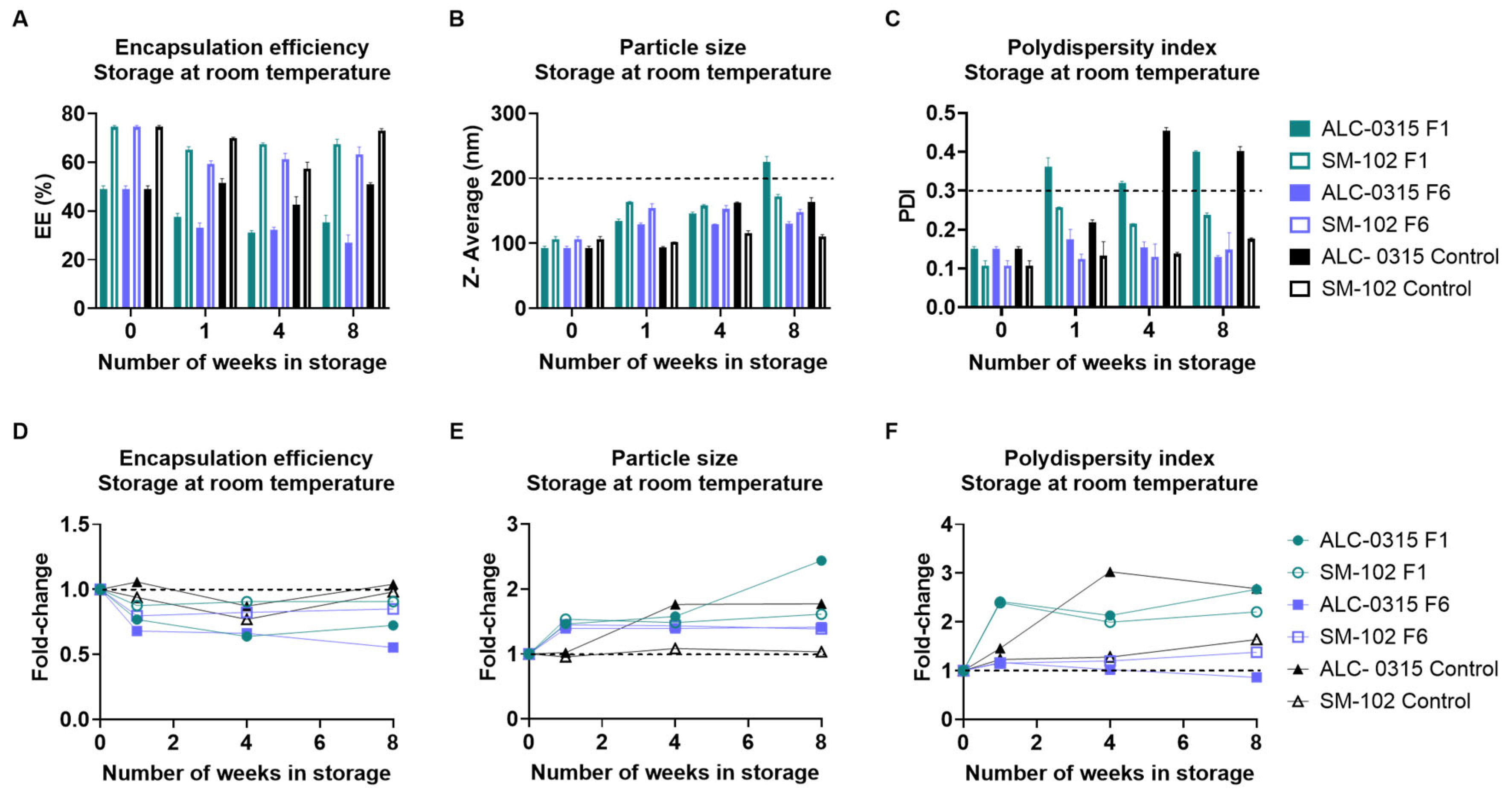

3.2.1. Long-Term Storage at Room Temperature

3.2.2. Long-Term Storage at 4 °C

3.2.3. Long-Term Storage at −20 °C

3.2.4. Long-Term Storage at −80 °C

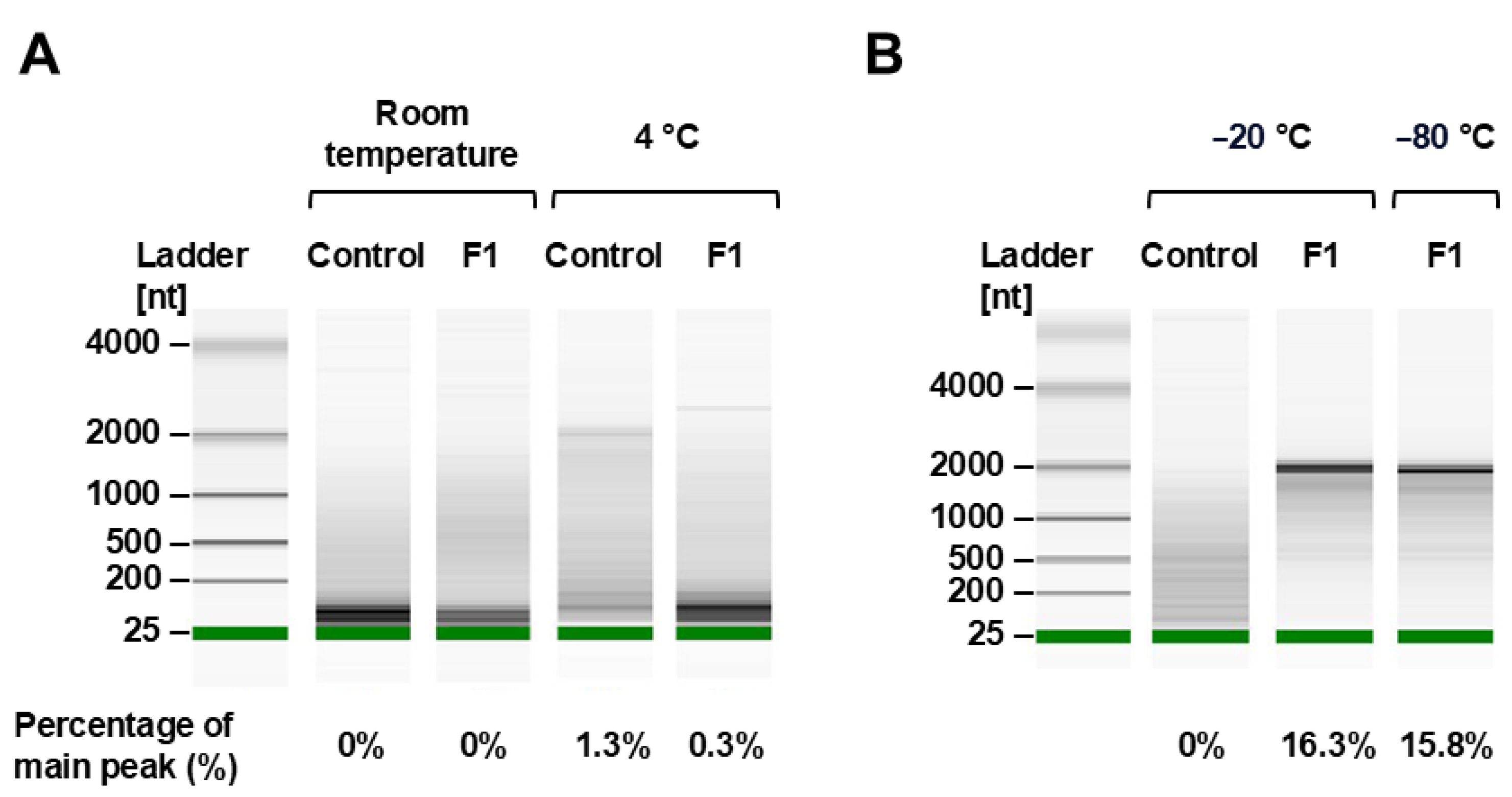

3.2.5. mRNA Integrity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| LNP | Lipid nanoparticle |

| EE | Encapsulation efficiency |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| eGFP | Enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| nLuc | NanoLuc luciferase |

| RT | Room temperature |

References

- Labouta, H.I.; Langer, R.; Cullis, P.R.; Merkel, O.M.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Gomaa, Y.; Nogueira, S.S.; Kumeria, T. Role of drug delivery technologies in the success of COVID-19 vaccines: a perspective. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2022, 12, 2581–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchio, R.; Gentile, L.; Tafuri, S.; Costantino, C.; Odone, A. Exploring future perspectives and pipeline progression in vaccine research and development. Ann Ig 2024, 36, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderer, S. FDA Approves Updated COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA 2024, 332, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRODUCT MONOGRAPH INCLUDING PATIENT MEDICATION INFORMATION SPIKEVAX. Available online: https://covid-vaccine.canada.ca/info/pdf/covid-19-vaccine-moderna-pm-en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- PRODUCT MONOGRAPH INCLUDING PATIENT MEDICATION INFORMATION COMIRNATY. Available online: https://covid-vaccine.canada.ca/info/pdf/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-pm1-en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Das, R. Update on Moderna’s RSV vaccine, mRESVIA (mRNA-1345), in adults≥ 60 years of age. 2024.

- Crommelin, D.J.; Anchordoquy, T.J.; Volkin, D.B.; Jiskoot, W.; Mastrobattista, E. Addressing the cold reality of mRNA vaccine stability. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2021, 110, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenke, E.O.; Örnskov, E.; Schöneich, C.; Nilsson, G.A.; Volkin, D.B.; Mastrobattista, E.; Almarsson, Ö.; Crommelin, D.J. The storage and in-use stability of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics: not a cold case. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2023, 112, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, L.; Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Verbeke, R.; Kersten, G.; Jiskoot, W.; Crommelin, D.J. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. International journal of pharmaceutics 2021, 601, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liang, Z.; Mao, Q.; Liu, D.; Wu, X.; Xu, M. Research advances on the stability of mRNA vaccines. Viruses 2023, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, M.; Bernard, M.-C.; Vaure, C.; Bazin, E.; Commandeur, S.; Perkov, V.; Lemdani, K.; Nicolaï, M.-C.; Bonifassi, P.; Kichler, A. An imidazole modified lipid confers enhanced mRNA-LNP stability and strong immunization properties in mice and non-human primates. Biomaterials 2022, 286, 121570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottger, R. mRNA vaccine stabilization through modulating LNP composition and utilizing drying technologies. 2022.

- Dumpa, N.; Goel, K.; Guo, Y.; McFall, H.; Pillai, A.R.; Shukla, A.; Repka, M.; Murthy, S.N. Stability of vaccines. Aaps Pharmscitech 2019, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandau, D.T.; Jones, L.S.; Wiethoff, C.M.; Rexroad, J.; Middaugh, C.R. Thermal stability of vaccines. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2003, 92, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, T.; Toro-Córdova, A.; Fernández, L.; Rivero, A.; Stoian, A.M.; Pérez, L.; Navarro, V.; Martínez-Oliván, J.; de Miguel, D. Comprehensive Optimization of a Freeze-Drying Process Achieving Enhanced Long-Term Stability and In Vivo Performance of Lyophilized mRNA-LNPs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 10603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Jia, L.; Xie, Y.; Ma, W.; Yan, Z.; Liu, F.; Deng, J.; Zhu, A.; Siwei, X.; Su, W. Lyophilization process optimization and molecular dynamics simulation of mRNA-LNPs for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perche, F.; Clemençon, R.; Schulze, K.; Ebensen, T.; Guzmán, C.A.; Pichon, C. Neutral lipopolyplexes for in vivo delivery of conventional and replicative RNA vaccine. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids 2019, 17, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, A.; Cui, C. Design strategies for and stability of mRNA–lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines. Polymers 2022, 14, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.I.; Eygeris, Y.; Jozic, A.; Herrera, M.; Sahay, G. Leveraging biological buffers for efficient messenger RNA delivery via lipid nanoparticles. Molecular pharmaceutics 2022, 19, 4275–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moderna, E. Assessment Report COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna. Procedure No; EMEA/H/C/005791/0000. Netherlands: European Medicines Agency: 2021.

- Peter Marks, M.D., Ph.D., Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. FDA. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/150386/download?attachment.

- Daniel, S.; Kis, Z.; Kontoravdi, C.; Shah, N. Quality by Design for enabling RNA platform production processes. Trends in biotechnology 2022, 40, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Bui, T.A.; Yang, X.; Aksoy, Y.; Goldys, E.M.; Deng, W. Lipid-based nanoparticles for drug/gene delivery: An overview of the production techniques and difficulties encountered in their industrial development. ACS Materials Au 2023, 3, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, K.J.; Higgins, J.; Woods, A.; Levy, B.; Xia, Y.; Hsiao, C.J.; Acosta, E.; Almarsson, Ö.; Moore, M.J.; Brito, L.A. Impact of lipid nanoparticle size on mRNA vaccine immunogenicity. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 335, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Darjuan, M.M.; Mercer, J.E.; Chen, S.; Van Der Meel, R.; Thewalt, J.L.; Tam, Y.Y.C.; Cullis, P.R. On the formation and morphology of lipid nanoparticles containing ionizable cationic lipids and siRNA. ACS nano 2018, 12, 4787–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, A.-G.; Osterwald, A.; Ringler, P.; Leiser, Y.; Lauer, M.E.; Martin, R.E.; Ullmer, C.; Schumacher, F.; Korn, C.; Keller, M. Investigations into mRNA Lipid Nanoparticles Shelf-Life Stability under Nonfrozen Conditions. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2023, 20, 6492–6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhijani, S.; Elossaily, G.M.; Rojekar, S.; Ingle, R.G. mRNA-based Vaccines–Global Approach, Challenges, and Could Be a Promising Wayout for Future Pandemics. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Kawai, M.; Sato, Y.; Maeki, M.; Tokeshi, M.; Harashima, H. The effect of size and charge of lipid nanoparticles prepared by microfluidic mixing on their lymph node transitivity and distribution. Molecular pharmaceutics 2020, 17, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, J.; Du, Z.; Wu, K.; Jin, S.; Wang, X.; Li, T.; Xu, Y. Biodistribution and non-linear gene expression of mRNA LNPs affected by delivery route and particle size. Pharmaceutical research 2022, 39, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, B.; Pabst, G.; Prassl, R. Long-term stability of sterically stabilized liposomes by freezing and freeze-drying: Effects of cryoprotectants on structure. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2010, 41, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirane, D.; Tanaka, H.; Nakai, Y.; Yoshioka, H.; Akita, H. Development of an alcohol dilution–lyophilization method for preparing lipid nanoparticles containing encapsulated siRNA. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2018, 41, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Almarsson, O.; Brito, L. Stabilized formulations of lipid nanoparticles. 2020.

- Leong, E.W.; Ge, R. Lipid nanoparticles as delivery vehicles for inhaled therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.N.K.; Davis, M.M.; Croyle, M.A. Identification of film-based formulations that move mRNA lipid nanoparticles out of the freezer. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, H.; Helgason, T.; Aulbach, S.; Kristinsson, B.; Kristbergsson, K.; Weiss, J. Influence of co-surfactants on crystallization and stability of solid lipid nanoparticles. Journal of colloid and interface science 2014, 426, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, H.; Helgason, T.; Kristinsson, B.; Kristbergsson, K.; Weiss, J. Formation of nanostructured colloidosomes using electrostatic deposition of solid lipid nanoparticles onto an oil droplet interface. Food Research International 2016, 79, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Yuan, Z.; He, L.; Han, L. Pluronic F127 coating performance on PLGA nanoparticles: enhanced flocculation and instability. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2023, 226, 113328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, N.V.; Khatri, H.N.; Patel, M.M. Formulation, optimization, and characterization of rifampicin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for the treatment of tuberculosis. Drug development and industrial pharmacy 2018, 44, 1975–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, A.; Bucolo, C.; Romano, G.L.; Platania, C.B.M.; Drago, F.; Puglisi, G.; Pignatello, R. Influence of different surfactants on the technological properties and in vivo ocular tolerability of lipid nanoparticles. International journal of pharmaceutics 2014, 470, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, N.U.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Sung, D.; Kim, H. Pluronic F-68 and F-127 based nanomedicines for advancing combination cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Liu, X.; Fan, D.; Qian, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, P.; Zhong, L. Study of Oncolytic Virus Preservation and Formulation. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, A.-L.; Colotte, M.; Luis, A.; Tuffet, S.; Bonnet, J. An efficient method for long-term room temperature storage of RNA. European Journal of Human Genetics 2014, 22, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summary Basis of Decision - Onpattro - Health Canada. Available online: https://hpr-rps.hres.ca/reg-content/summary-basis-decision-detailTwo.php?linkID=SBD00446 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Suzuki, Y.; Ishihara, H. Difference in the lipid nanoparticle technology employed in three approved siRNA (Patisiran) and mRNA (COVID-19 vaccine) drugs. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics 2021, 41, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamashita, K.; Izumi, T.; Kawaguchi, M.; Mizukami, S.; Tsurumaru, M.; Mukai, H.; Kawakami, S. Stability study of mRNA-lipid nanoparticles exposed to various conditions based on the evaluation between physicochemical properties and their relation with protein expression ability. pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Hosn, R.R.; Remba, T.; Yun, D.; Li, N.; Abraham, W.; Melo, M.B.; Cortes, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Optimization of storage conditions for lipid nanoparticle-formulated self-replicating RNA vaccines. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 353, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, U.; Truong, H.Q.; Nguyen, C.T.G.; Meng, F. Development of Thermally Stable mRNA-LNP Delivery Systems: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2024, 21, 5944–5959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Rigas, D.; Kim, L.J.; Chang, F.-P.; Zang, N.; McKee, K.; Kemball, C.C.; Yu, Z.; Winkler, P.; Su, W.-C. Physicochemical and structural insights into lyophilized mRNA-LNP from lyoprotectant and buffer screenings. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 373, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vaccine Name | Ionizable Lipid | 2-8 °C Shelf Life | Room Temp Shelf Life | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 | ALC-0315 | Up to 5 days | Up to 2 hours | 6-10 doses per vial |

| mRNA-1273 | SM-102 | 30 days | Up to 12 hours | 5-20 doses per vial |

| Buffer | Surfactant | Sugar | Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 M Tris (pH 8) | 0.5% P188 | 8% Sucrose | F1 |

| 8% Trehalose | F2 | ||

| 8% Mannitol | F3 | ||

| 0.5% F127 | 8% Sucrose | F4 | |

| 8% Trehalose | F5 | ||

| 8% Mannitol | F6 | ||

| None | None | Control (F7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).