1. Introduction

Over the past decades, the global health community has made concerted efforts to develop effective vaccines against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a pathogen that continues to pose a significant public health challenge. Despite the progress made in understanding the virology and immunopathogenesis of HIV, the creation of a universally effective prophylactic vaccine remains elusive. This difficulty largely arises from the virus’s high genetic variability, its ability to evade immune surveillance, and the absence of clear correlates of immune protection. These challenges have necessitated the exploration of innovative immunological paradigms and delivery strategies that extend beyond conventional vaccine approaches.

Traditional immunisation methods typically involve the administration of attenuated pathogens, inactivated organisms, or recombinant antigens via parenteral routes to induce humoral and cellular immunity. However, such techniques often require cold-chain logistics, trained personnel, and medical infrastructure, which limits their scalability in resource-poor settings. Additionally, the administration of foreign antigens may elicit variable immune responses depending on the host’s immunocompetence and prior exposure history. This has led researchers to investigate alternative approaches, including the use of immunologically active antibodies that can trigger secondary immune cascades in the host without necessitating exposure to the primary pathogen.

Among these alternative approaches, the use of idiotype-based immunomodulation, rooted in the theory of the immune network, has gained increasing attention. Niels Jerne’s idiotypic network hypothesis, proposed in the 1970s, provides a theoretical foundation for how antibodies can act as both antigenic stimulants and regulatory elements within the immune system. According to this model, every antibody (Ab1) carries a unique idiotype—a set of determinants within the variable region of the immunoglobulin—that can be recognised as an antigen by other B cell receptors. This recognition leads to the production of anti-idiotypic antibodies (Ab2), which, in some cases, may mimic the three-dimensional configuration of the original antigen. A subsequent round of immune activation may then lead to the generation of anti-anti-idiotypic antibodies (Ab3), capable of structurally and functionally emulating the native antigen [

1].

This immunological model implies that protective immune responses can be induced indirectly through a network of idiotype–anti-idiotype interactions, without introducing the actual pathogen or its derivatives. The potential of this approach lies in its capacity to evoke specific and lasting immunity by leveraging the body’s internal regulatory circuits, thus providing an alternative platform for vaccine development. Several studies have already demonstrated the potential of anti-idiotypic antibodies as vaccine surrogates in oncology, parasitology, and virology [

2].

In the context of HIV, the envelope glycoprotein gp120 represents a key target for immunological intervention. This protein facilitates viral attachment to host CD4+ T cells and contains multiple conserved domains essential for infectivity. The peptide fragment spanning amino acids 254–274 has been identified as a conserved and immunogenic epitope critical for viral neutralisation [

3]. Immunological strategies that target this region have shown promise in eliciting neutralising antibodies in various model systems.

In this study, we explore the possibility of using orally administered, antigen-specific antibodies as a means to initiate idiotypic responses in a mammalian host. This method bypasses the need for live attenuated or inactivated viruses, instead relying on the immunomodulatory properties of antibodies themselves to stimulate secondary antibody production. When administered via the gastrointestinal tract, these antibodies are hypothesised to interact with gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), leading to the activation of B cells that recognise the idiotypic determinants of the ingested antibodies. Through this process, anti-idiotypic and potentially anti-anti-idiotypic antibodies may be generated, mimicking the original HIV antigen and thereby priming the immune system against future exposure.

The oral route was chosen not only for its practicality and non-invasiveness but also for its capacity to engage the mucosal immune system. The mucosal immune network plays a vital role in defending against pathogens that enter through epithelial surfaces, which are also primary sites of HIV transmission. Furthermore, the oral administration of biologically active antibodies is a promising avenue for vaccine delivery in populations where traditional methods are either impractical or contraindicated.

Among various sources of antibodies, those derived from eggs (specifically immunoglobulin Y, or IgY) have demonstrated several advantageous properties that make them ideal candidates for immunological applications. Egg-derived antibodies do not bind to mammalian Fc receptors and do not activate the mammalian complement system, reducing the risk of inflammatory side effects. Moreover, they exhibit minimal cross-reactivity with human antibodies, rheumatoid factors, or heterophilic antibodies, which increases the specificity of immunological assays and therapies [

4]. In addition, IgY is known for its biochemical stability under acidic conditions and partial resistance to gastrointestinal degradation, which allows it to retain immunological activity during transit through the digestive tract [

5]. These characteristics make IgY antibodies particularly suitable for oral administration, where they can reach mucosal surfaces and maintain functional binding to target antigens.

Studies have also indicated that IgY can be produced in large quantities in a cost-effective and non-invasive manner. This scalability makes them particularly attractive for use in low-resource settings and for large-scale immunisation campaigns. Their stability during storage and processing adds to their logistical feasibility in public health contexts [

2].

Aims: The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the immunogenicity and functionality of orally administered anti-HIV antibodies targeting the gp120 254–274 region in a controlled mammalian model. Specifically, the research aims to:

Determine whether oral delivery of these antibodies can induce the production of anti-idiotypic and anti-anti-idiotypic antibodies in recipient animals.

Assess the capacity of these secondary antibodies to inhibit the binding of the original antigen to its cognate antibody, thus demonstrating functional mimicry.

Validate the potential of this approach as a foundation for developing oral immunotherapeutics against HIV and potentially other viral pathogens.

By integrating foundational immunological theories with contemporary challenges in vaccine development, this study aims to contribute a novel perspective to the field of mucosal immunisation and advance the understanding of idiotypic vaccine strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

This investigation employed a multi-phase experimental design to assess the immunogenic potential of orally administered antibodies targeting a specific epitope of the HIV gp120 envelope protein. The methodology was structured to replicate the conditions of mucosal immune activation and to evaluate the subsequent systemic antibody response within a mammalian model.

Design and Synthesis of Immunogen: The target antigen utilised in this study was a conserved peptide region of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein, comprising the amino acid sequence Gly-Ile-Arg-Pro-Val-Val-Ser-Thr-Gln-Leu-Leu-Leu-Asn-Gly-Ser-Leu-Ala-Glu. This sequence corresponds to a functionally relevant site implicated in viral attachment and fusion with host cells [

5]. The synthetic peptide was conjugated to a highly immunogenic carrier protein, keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), through a glutaraldehyde-mediated cross-linking reaction. The conjugation reaction was carried out in a borate buffer at alkaline pH to facilitate covalent binding. Post-reaction, the conjugate was purified via overnight dialysis against a series of buffered solutions to eliminate unreacted reagents and ensure biochemical stability [

6].

Immunisation of Donor Organisms: Donor animals were selected and acclimatised under controlled conditions prior to immunisation. Each subject received an intramuscular injection of the KLH-peptide conjugate suspended in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) on day 0. Booster doses were subsequently administered on days 15, 60, and 90 using incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) to maintain a robust antibody response. Injection sites were rotated to prevent localised tissue irritation. Blood and biological specimens were periodically collected post-immunisation for antibody isolation.

Extraction and Processing of Immune Material: The antibody-rich material was subjected to a multi-step purification protocol adapted from Polson’s aqueous two-phase separation method. This procedure allowed for the isolation of immunoglobulins within the water-soluble fraction (WSF), which contains bioactive IgY or equivalent antibodies depending on the species employed. The extraction process was performed under chilled, sterile conditions to preserve antibody integrity and minimise proteolytic degradation [

2].

Animal Model and Oral Administration: Six adult cats (age range: 2–3 years) were selected for the oral administration study. These animals were housed in individual enclosures under standardised lighting and feeding conditions, in compliance with animal welfare regulations. Three animals were designated as the test group and received 2 mL of the antibody-enriched WSF diluted in 10 mL of soy-based milk substitute, administered orally once per week for a duration of ten consecutive weeks. The remaining cats formed the control group and received an identical volume of WSF obtained from non-immunised donor animals. All animals were closely monitored for behavioural and physiological responses.

Sample Collection and Storage: Following the ten-week administration period, 2 mL of blood was collected from each subject via venipuncture. Serum was separated through centrifugation and stored at −20°C until further analysis. Samples were coded and processed in a blinded manner to reduce potential bias during data interpretation.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): To detect anti-gp120 antibodies in both donor extracts and recipient serum, an indirect ELISA was performed. Microtiter plates were coated with 51 ng/well of the gp120 peptide dissolved in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer and incubated at 37°C for 4 hs. After washing with PBS-Tween, non-specific binding sites were blocked using 3% non-fat dried milk in PBS. Serial dilutions of test samples were applied in triplicate. Bound antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-species secondary antibodies—either rabbit anti-IgY or protein LA-HRP, depending on the sample origin. The colourimetric substrate tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used for signal development, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader [

2,

5].

Competitive Binding Inhibition Assay: To evaluate the functional specificity of anti-idiotypic antibodies, a competitive inhibition assay was conducted. Microplates were coated with the gp120 peptide as described above. Serial dilutions of recipient serum were incubated in the wells, followed by the addition of a standardised concentration of anti-gp120 primary antibody. After a second incubation, bound antibodies were detected using HRP-labelled anti-IgY, and absorbance was measured post-TMB development. Percentage inhibition was calculated by comparing the absorbance of wells containing serum samples to those without competitor antibody. Inhibition above 10% was considered indicative of anti-idiotypic activity.

Ethical Considerations: All animal procedures were approved by the University of the West Indies Ethics Committee. Faculty of Medical Sciences, Mona Campus. Experimental protocols conformed to institutional and international guidelines for the ethical use of animals in research.

Statistical Analysis: Data were processed using the Epi Info 3.5.3 software package. Descriptive statistics were employed to compute geometric mean titres and standard deviations. Inferential analyses, including the chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test, were used to compare categorical outcomes between experimental and control groups. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied for all statistical comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Antibody Titre in Donor Extracts:

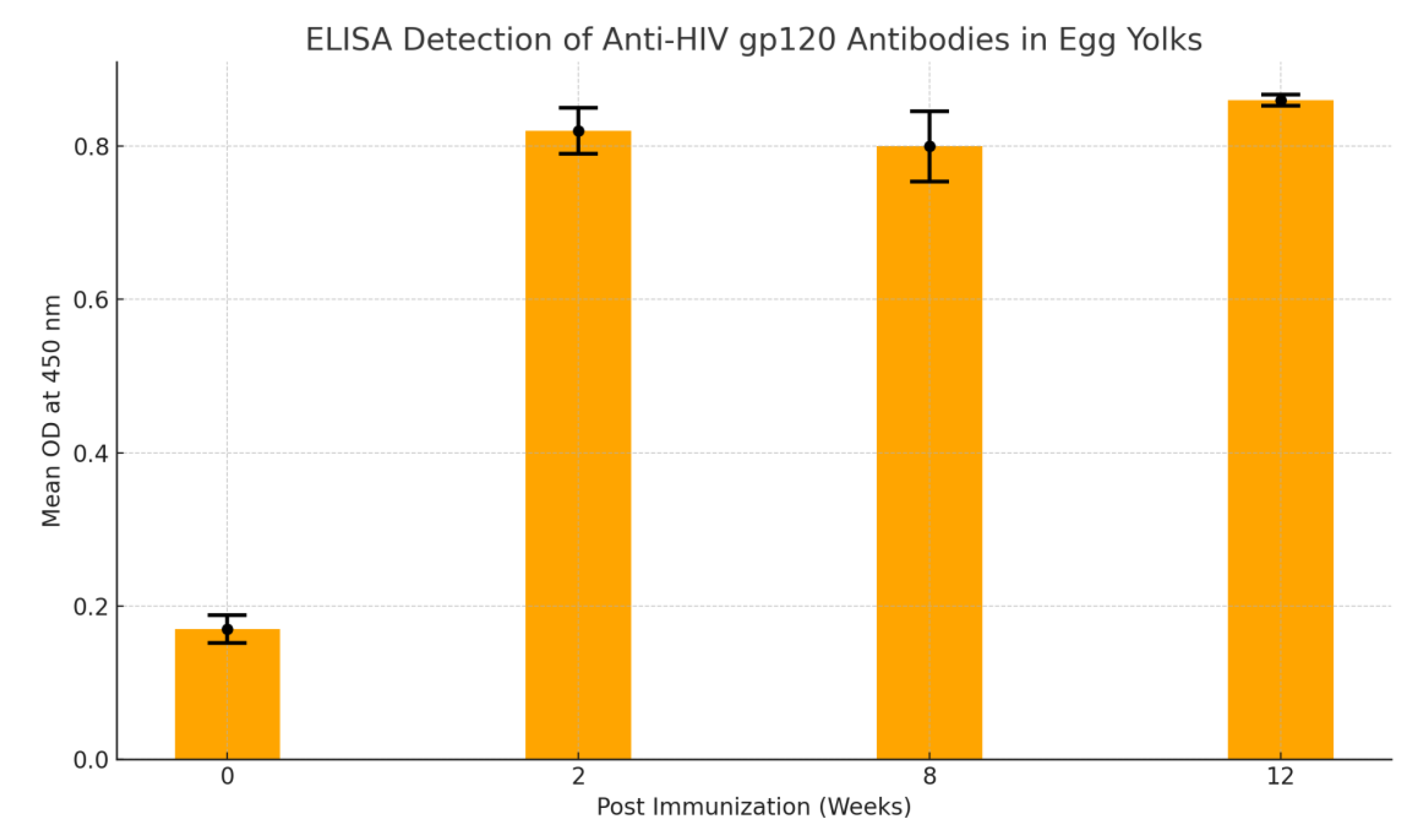

High titres of anti-gp120 antibodies were detected in donor samples. ELISA revealed consistent absorbance values indicating sustained antibody production from week 2 to week 12 post-immunisation. The geometric mean titre (

Figure 1) was calculated as 1024 using Perkins’ method [

7].

3.2. Immune Response in Recipients:

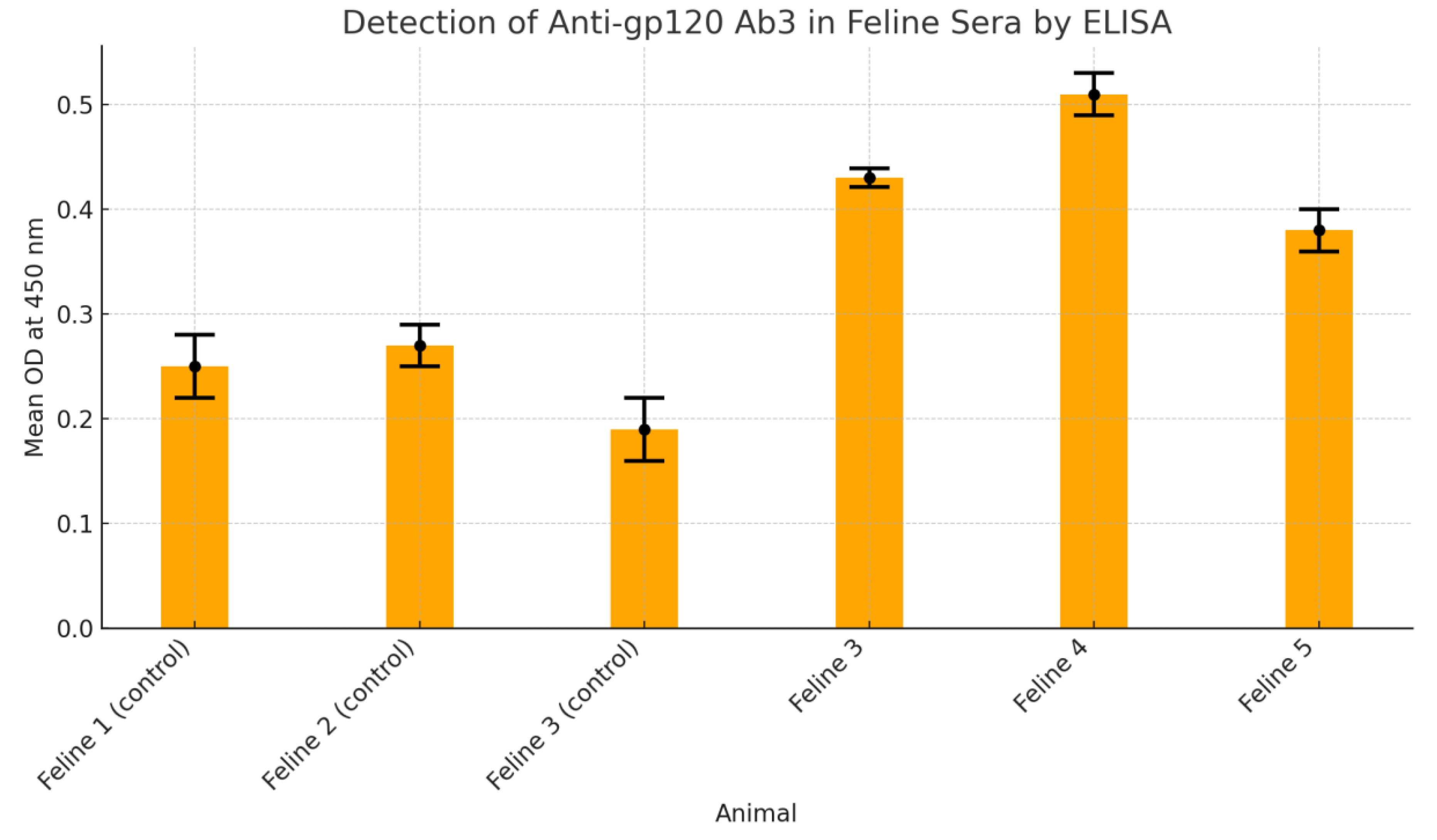

Among the feline subjects receiving the immunised preparation, all three exhibited ELISA values above the designated cut-off (0.35), indicating seroconversion (

Figure 2). In contrast, control animals exhibited readings well below threshold.

3.3. Detection of Ab-3 in Feline Sera

Figure 3 presents findings from an ELISA-based assay designed to detect anti-gp120 Ab3 antibodies in feline serum samples. Three control animals—Feline 1, 2, and 3—demonstrated low mean optical density (OD) values (0.25, 0.27, and 0.19 respectively), all below the established cut-off of 0.35, indicating negative results for the presence of Ab3 antibodies. In contrast, test animals—Feline 4, 5, and 6—showed elevated OD readings of 0.43, 0.51, and 0.38 respectively, all surpassing the threshold, signifying positive antibody detection. These values were calculated from triplicate sample measurements, ensuring statistical reliability. Standard deviations were minimal, underscoring consistent assay performance. The results validate the successful elicitation of Ab3 antibodies in immunised felines, while negative controls confirmed assay specificity. This evaluation supports the efficacy of the immunisation strategy in stimulating an anti-idiotypic antibody response against HIV-gp120, providing a foundational insight into potential oral immunotherapy models.

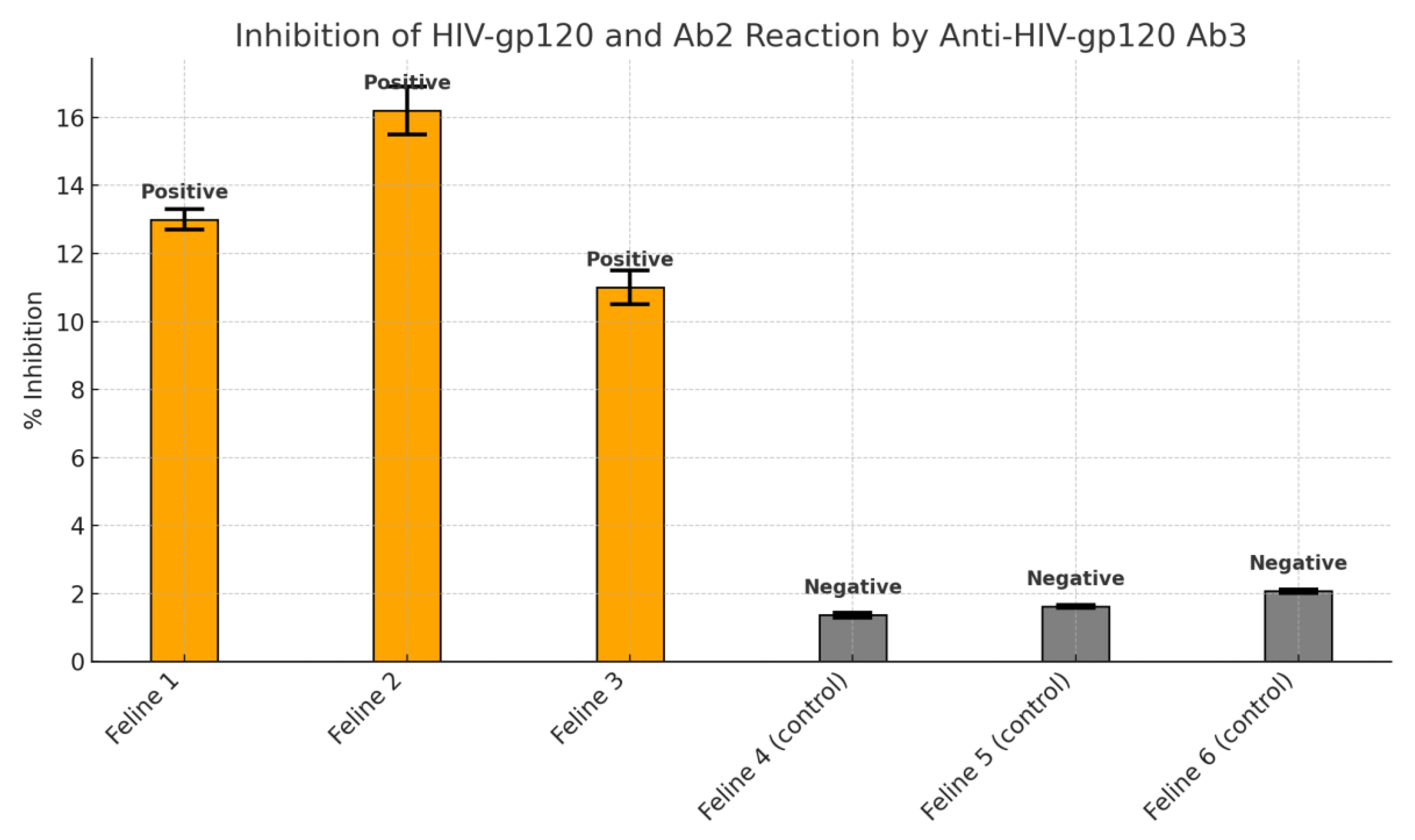

3.4. Competitive Inhibition Results

Serum from treated animals demonstrated 10–16.2% inhibition of gp120 antibody binding, strongly suggesting the generation of anti-idiotypic antibodies. Control subjects showed inhibition levels below 2%, confirming the specificity of the response. The results were statistically significant (p = 0.003).

This study presented compelling findings regarding the immunogenic potential of orally administered antibodies specific to a conserved region of the HIV gp120 protein. The initial phase confirmed the success of the immunisation protocol by demonstrating robust antibody titres in the donor samples. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results indicated consistent production of anti-gp120 antibodies from week two through week twelve post-immunisation, with a geometric mean titre calculated as 1024 using Perkins’ logarithmic method [

7]. These high titres verified that the immunogen and adjuvant protocol effectively stimulated a durable immune response in the donor models.

The key focus then shifted to the recipients, where the goal was to evaluate the systemic immunological impact of consuming these antibody-enriched materials. Notably, all three cats receiving the immunologically active preparation demonstrated ELISA absorbance values above the established threshold of 0.35. These readings reflect successful seroconversion and provide strong evidence that oral exposure to immunoglobulins can provoke measurable antibody production in mammals. Importantly, this was achieved without the use of traditional adjuvants or direct antigen exposure, suggesting the oral preparations maintained sufficient biological integrity to engage the mucosal immune system.

In contrast, the two control animals that were administered non-immunised materials exhibited no such immune responses. Their absorbance values remained well below the cut-off, confirming the specificity of the immune reaction observed in the treated group. This differentiation ruled out nonspecific immune activation due to the oral delivery vehicle or environmental variables, thereby strengthening the argument that the antibodies themselves were immunogenic.

The use of a competitive inhibition assay further substantiated these results. Serum samples from the treated animals exhibited a significant capacity (10–16.2%) to inhibit the anti-gp120 Ab - gp120 peptide binding. Such inhibition indicates the presence of secondary Ab capable of mimicking the antigen-binding region—a characteristic feature of anti-idiotypic antibodies. This capacity to interfere with antigen–antibody binding reinforces the concept that the recipient animals not only generated antibodies in response to the ingested preparation but that these antibodies were functionally relevant within the context of idiotypic network theory.

Moreover, statistical analysis validated these observations with a p-value of 0.003, denoting a high level of confidence in the difference between the test and control groups. The chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests further supported the robustness of the data and ruled out the likelihood of random variation influencing the outcomes.

These findings provide significant insights into the immunological processing and recognition of orally delivered antibodies. The data indicate that the gastrointestinal tract, traditionally viewed as a site of immunotolerance or degradation, can be recontextualised as a portal for immunological education. The generation of anti-idiotypic responses in this setting not only aligns with Jerne’s theoretical framework but also exemplifies its translational potential.

Another notable observation is the timeline of the antibody response. Detectable antibody levels were present only after multiple weeks of exposure, reflecting a delayed yet sustained activation of the adaptive immune system. This mirrors the kinetics observed in classical immunisation, where repeated exposures are necessary to prime and expand the B-cell repertoire. The persistence of antibody production in donors, combined with the gradual but consistent immune response in recipients, highlights the importance of dosage and exposure frequency in oral immunisation protocols.

Collectively, these findings validate a foundational hypothesis: that orally introduced antibodies, when targeting structurally significant regions of pathogenic proteins such as HIV gp120, can elicit a cascade of immune recognition events culminating in the production of anti-idiotypic antibodies. This secondary antibody population may be instrumental in mimicking the native antigen and could potentially serve as a surrogate immunogen in broader vaccine development strategies.

Thus, the results of this study bridge a critical gap between theoretical immunology and practical application. They not only affirm the viability of idiotypic network theory but also demonstrate its applicability in designing alternative immunisation strategies that may be particularly beneficial in resource-limited or immunologically complex settings.

4. Discussion

This study highlights a promising alternative to conventional immunisation strategies by demonstrating the capacity for oral delivery of antibodies to induce functionally significant anti-idiotypic responses. The findings build upon Jerne’s hypothesis of an idiotypic cascade and affirm the concept that ingested antibodies can trigger internal immune feedback loops resulting in secondary antibody production [

2,

5].

Oral administration offers a number of advantages over traditional parenteral vaccination. These include improved compliance, absence of needle-associated risks, and potential for mass immunisation campaigns. Additionally, the mucosal immune system, particularly gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), plays a critical role in intercepting pathogens and initiating immune responses. Therefore, targeting this immunological compartment via oral delivery is both rational and strategic.

The structural and functional resistance of immunoglobulins to gastrointestinal degradation, particularly when delivered in bioactive matrices, supports their viability as orally active agents [

8,

9]. This delivery mode is further reinforced by the presence of natural protective elements that stabilise antibodies in the digestive tract.

In terms of immunological relevance, the gp120 envelope protein remains a primary target in HIV vaccine development. The peptide used in this study—covering a conserved sequence implicated in viral entry—offers a potent antigenic determinant [

5]. The results demonstrated here suggest that antibodies against this region, when orally administered, may successfully prime the immune system for a secondary idiotypic response.

This study also contributes to the broader understanding of idiotype–anti-idiotype interactions as mediators of immune regulation. It provides empirical support for the therapeutic use of anti-idiotypic antibodies not only as vaccines but also as modulators of immune homeostasis [

10].

The findings presented in this investigation contribute substantially to the broader field of immunoprophylaxis by demonstrating the utility of orally administered antibodies in eliciting measurable systemic immune responses. In particular, this study validates the practical relevance of Jerne’s idiotypic network theory, highlighting the immunological interplay between ingested antibodies and host adaptive mechanisms.

The concept of anti-idiotypic vaccination, once predominantly theoretical, gains empirical support through these findings. Jerne’s hypothesis posits that antibodies not only function as immune effectors but can themselves serve as antigens to stimulate a second wave of immune responses. The emergence of anti-idiotypic antibodies—especially those mimicking the original epitope (Ab3)—confirms the recursive and adaptive nature of the immune network [

2]. This response was evident in the treated subjects who developed specific antibodies that could inhibit the interaction between the original anti-HIV antibodies and the gp120 peptide. Such interference suggests that these secondary antibodies mimicked the structural characteristics of the HIV epitope [

2].

Central to this discussion is the implication that the immune system can recognise and mount a response to a molecular signature encoded within the idiotype of a primary antibody. This phenomenon underscores the system’s internal capacity for antigen-independent immunological learning and memory—a concept that challenges the conventional paradigm that immune memory must be pathogen-derived [

10,

11].

The immunological relevance of the gp120 envelope protein of HIV, particularly its conserved 254–274 region, cannot be overstated. This region plays a crucial role in viral binding and entry into host cells, making it an ideal target for vaccine development [

2]. By inducing a cascade of idiotype and anti-idiotype interactions, the study demonstrates that immune recognition of this critical domain can be initiated indirectly, without the need for direct antigen exposure. This model may be particularly advantageous in immunocompromised individuals or populations where exposure to live or attenuated virus presents undue risk.

Furthermore, oral immunisation represents a frontier in immunological accessibility and compliance. Unlike parenteral routes, oral delivery can engage mucosal immune responses and has the potential to prime both systemic and local immunity through gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). The data from this study reinforce the mucosal compartment’s role as an immunologically competent site capable of generating functionally relevant antibody responses. This finding aligns with prior studies that demonstrate the oral mucosa’s involvement in tolerance as well as active immunity, depending on the context and antigen presentation [

12,

13].

Critically, the structural resilience of antibodies used in this study likely contributed to their successful transit through the gastrointestinal tract. IgY, for instance, has shown high resistance to proteolytic degradation compared to mammalian IgG, retaining functional integrity in harsh environments such as the gut [

2,

13]. The use of suitable matrices or delivery vehicles may further augment stability and bioavailability, enhancing oral vaccine efficacy.

Moreover, the delayed onset of antibody detection in recipient subjects echoes the kinetics of conventional vaccine responses, where repeated exposure is typically required to achieve robust seroconversion. This delay highlights a key consideration for future vaccine schedules—namely, that oral immunisation protocols may benefit from booster doses to ensure sustained and high-affinity responses. Notably, the serological assays confirmed antibody presence only after several weeks of repeated administration, suggesting a threshold exposure necessary to breach mucosal tolerance and activate systemic immunity.

The inhibition assay results, showing up to 16.2% blockage of antigen–antibody binding, serve as a quantitative marker of anti-idiotypic antibody activity. While this percentage may appear modest, it is critical to interpret this in the context of functional mimicry. The mere ability of a secondary antibody to interfere with the binding of a high-affinity primary antibody suggests structural congruence with the original epitope. This supports the notion that anti-idiotypic antibodies may act as antigen surrogates, stimulating both B and T cell responses analogous to those elicited by conventional vaccines.

Additionally, these results raise important questions regarding the potential regulatory effects of anti-idiotypic antibodies. In autoimmune diseases, anti-idiotypic responses may serve as natural brakes on pathogenic antibodies. Conversely, in infectious disease settings, they may bolster immunity by simulating continual antigenic stimulation. This dual role merits further exploration, especially in the design of immune-modulating therapies or vaccines.

The statistical robustness of the findings, underscored by a p-value of 0.003, confirms that the observed effects were unlikely due to random chance. This statistical validation is critical, as it supports the reproducibility of the model and provides a framework for further experimental expansion. These findings also provide a template for evaluating idiotypic responses in other infectious diseases, including influenza, hepatitis, and emerging viral pathogens.

Beyond the scientific implications, the practical advantages of this strategy are noteworthy. Oral delivery is non-invasive, reduces the need for medical infrastructure, and has high patient acceptability—factors particularly beneficial in low-resource settings [

14]. The scalability of such immunisation protocols is also promising, given that the raw materials and preparation methods can be adapted to various local contexts.

Another layer of discussion involves the possibility of synergistic action between administered antibodies and the host’s innate immune components. The presence of naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides, enzymes, and mucosal IgA in the digestive tract may synergise with orally administered antibodies to enhance immune activation [

15]. These interactions could amplify antigen presentation and help cross-prime T cells, leading to a more integrated and effective immune response.

In the context of HIV, where mucosal surfaces are key entry points for viral transmission, the development of mucosal immunity is particularly pertinent. Traditional vaccines often fail to generate strong mucosal responses [

16]. Therefore, the oral route offers a promising alternative, not only for systemic immunity but also for neutralising viruses at their initial points of contact with the host [

15].

It is also worth considering how the idiotypic network model integrates with broader concepts in immunology, such as clonal selection and immune homeostasis. The idiotypic network does not contradict these frameworks but rather complements them by providing an explanation for how immune responses are fine-tuned and maintained over time. It introduces a feedback loop that can self-limit or potentiate responses depending on the immunological context, adding a layer of dynamic regulation that could be harnessed therapeutically [

17].

Finally, the success of this model paves the way for investigating a broader spectrum of orally delivered immunotherapies. While the present study focused on antibodies targeting HIV, the platform could be extended to other applications such as cancer immunotherapy, allergy desensitisation, and modulation of autoimmune responses. The ability to control and direct the immune response through idiotype-based interventions could usher in a new era of precision immunology.

In summary, this study enriches our understanding of how oral immunisation strategies can exploit the idiotypic network to generate protective and functional immune responses. It affirms the potential of antibody-based immunotherapy in circumventing traditional limitations of vaccine design and introduces a paradigm shift in how we conceptualise antigen delivery, immune priming, and memory induction. Continued research in this area holds the promise of unveiling more nuanced mechanisms and novel therapeutic opportunities for managing infectious and immune-mediated diseases.

HIV-1 gp120 254–274 Epitope in Peptide Vaccine Development

Developing an effective HIV vaccine remains a formidable challenge due to the virus’s diversity and immune evasion. One strategy has been to target highly conserved and functionally important epitopes on the envelope glycoprotein gp120, hoping to induce broadly protective responses. A prominent example is the conserved region encompassing amino acids 254–274 of gp120 (within the second conserved (C2) domain). Early studies identified this segment as immunogenic and potentially involved in viral neutralization [

18]. This critical evaluation examines the historical and current insights into the 254–274 epitope’s role in neutralization, and assesses the evidence from preclinical and clinical studies targeting this epitope with peptide-based vaccines. We also discuss peptide design strategies, delivery systems (e.g. nanoparticle carriers and adjuvants), and the immunological outcomes observed.

The Conserved 254–274 gp120 Epitope and Its Role in Neutralization

The gp120 254–274 region lies in a relatively conserved part of the Env protein’s C2 domain. Notably, this segment is highly conserved across diverse HIV-1 strains [

19] and contains residues crucial for Env function. In the context of intact gp120 on the viral spike, the 254–274 region is thought to be structurally buried or “immunosilent”, meaning it’s poorly accessible to antibodies [

19]. However, once gp120 binds to CD4 on a host cell, conformational changes occur that expose inner domains (including the 254–274 region), which then participate in coreceptor binding and trigger gp41-mediated fusion [

19]. Indeed, this fragment has been implicated in post-CD4 binding events required for viral entry, suggesting that antibodies binding this site could neutralize the virus after it attaches to the cell [

20]. Early structural studies supported a propensity of the isolated 254–274 peptide to form defined secondary structures (β-turn or helix) under certain conditions [

19], hinting that in the context of the native trimer this region adopts specific conformations linked to its function. Because of its conserved sequence and essential role in entry, the 254–274 epitope was proposed as a promising vaccine target for inducing antibodies that broadly neutralize HIV-1 [

20].

Historically,

Ho et al. (1988) provided the first direct evidence of this epitope’s neutralization relevance [

20]. Rabbits immunized with a synthetic peptide spanning gp120 residues 254–274 produced antisera that neutralized multiple HIV-1 isolates in vitro [

20]. Remarkably, these antibodies did not block the virus’s attachment to CD4-positive cells, but they still prevented infection, consistent with interference at a post-binding step [

20]. This finding indicated that the conserved C2 segment is an attractive target: antibodies to this region can neutralize HIV without preventing initial receptor binding, presumably by blocking the subsequent conformational changes or gp41 fusion activation [

20]. Early on, some even termed this site a “principal” neutralizing epitope alongside the more variable V3 loop [

21]. However, follow-up studies nuanced this view. For example, Profy et al. (1990) fractionated broadly neutralizing human serum and found that antibodies targeting the classic V3 loop accounted for type-specific neutralization, whereas antibodies against peptides 254–274 (and another conserved segment in gp41) did not absorb the broad neutralizing activity [

22]. This suggested that while 254–274 is immunogenic and can induce neutralizing antibodies, natural broad neutralization in patients may target other epitopes not yet identified at that time [

22]. In other words, 254–274-directed antibodies in an infected individual’s polyclonal serum were not the dominant source of breadth, hinting that the virus might hide this epitope or that typical infection doesn’t elicit sufficient antibody titers to it.

Indeed, in natural HIV infection the 254–274 region appears to be a subdominant or late-emerging B-cell epitope, likely due to its occlusion by gp120’s structure and surrounding glycans. One conformational mAb (15e) identified in the late 1980s was found to neutralize diverse strains and map to C1/C2 regions (overlapping this epitope), but it required the gp120’s native conformation, underscoring that conformation-dependent presentation is key for such epitopes [

20]. Moreover, some CD4-induced (CD4i) antibodies (e.g. A32-like specificities) from HIV+ donors target inner gp120 regions including C2; these typically do not neutralize virus in standard assays but can mediate effector functions like ADCC. Interestingly, analyses from an HIV vaccine trial in macaques showed that after virus challenge, animals that eventually controlled viremia developed anti-CD4i epitope antibodies as part of the response [

23]. This aligns with the notion that once the virus engages cells, antibodies to normally-hidden epitopes (like 254–274) can emerge and contribute to viral control [

23]. These insights set the stage for vaccine strategies to

proactively induce such antibodies.

Preclinical Vaccine Studies Targeting 254–274

Numerous preclinical studies have evaluated peptide vaccines encompassing the 254–274 epitope. Early animal immunizations were promising: as noted, rabbits immunized with the 254–274 peptide (usually coupled to a carrier protein for immunogenicity) produced polyclonal sera neutralizing diverse HIV-1 laboratory strains [

20]. Building on this, researchers in the 1990s explored multi-epitope vaccine constructs. For example, Palker et al. (1989) formulated a polyvalent immunogen combining gp120 B-cell neutralization epitopes (including C2 and V3 segments) with T-helper epitopes [

20]. Such designs aimed to ensure the peptide would induce not only B-cell responses but also receive CD4⁺ T cell help for robust antibody production. In general, short peptides by themselves are poorly immunogenic; thus, conjugation to larger carriers or multimerization is critical. Researchers found that coupling gp120(254–274) to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) via glutaraldehyde greatly enhanced the immune response, whereas the free peptide alone was ineffective [

24]. In one protocol, brown Leghorn chickens immunized with KLH-conjugated 254–274 generated high anti-gp120 antibody titers [

24].

An interesting extension of this work involved the use of avian antibodies (IgY): after hens were immunized with KLH-254–274, the resulting anti-HIV IgY in egg yolks was harvested and fed to naive chicks [

2]. The orally delivered antibodies survived gut passage enough to act as an oral “passive vaccine,” reportedly triggering anti-HIV immune responses in the recipient chicks [

2]. This innovative approach, while aimed at passive immunoprophylaxis, underscores the peptide’s strong immunogenicity – the elicited antibodies were functional enough to be recognized and possibly induce responses upon oral administration.

Concurrently, other delivery platforms have been tested. Nanoparticle-based delivery has shown promise in amplifying peptide vaccines. One recent strategy used polyamidoamine dendrimer nanoparticles (PAMAM G4) as a scaffold to multimerize HIV gp120 peptides. In a mouse model, intranasal administration of peptides – either alone or as peptide–dendrimer complexes – elicited mucosal and systemic immunity, but the dendrimer-peptide nanoparticles induced significantly higher IgG and IgA responses than peptide alone [

25]. This illustrates that clustering the 254–274 epitope on a nanoscale platform can increase its immunogenicity, likely by better activating B-cell receptors (through epitope multivalency) and protecting the peptide from rapid degradation. Other nanoparticle or virus-like particle (VLP) approaches have included fusing gp120 fragments (including C2 region) to self-assembling carriers like Hepatitis B core or surface antigen, creating repetitive arrays of the epitope on VLPs [

26]. Such particles can drain efficiently to lymph nodes and present the antigen in an ordered array to stimulate B cells.

In terms of immune responses in these preclinical studies, the vaccines targeting 254–274 have consistently induced high titers of specific antibodies. Often a strong IgG response was observed in serum, and in mucosal models, IgA was also generated [

25]. Functionally, the antibodies from peptide-immunized animals could bind gp120 and sometimes neutralize homologous virus strains. For instance, the rabbit antisera to 254–274 neutralized not only the immunizing strain but also several other isolates of HIV-1 (across clades IIIB, RF, MN) [

20].

Importantly, the 254–274 region also contains T-cell epitopes that can be targeted by vaccines. Being conserved, it can harbor CD4⁺ T-helper epitopes – indeed, some vaccine formulations have documented Env-specific T cell responses. In macaques primed with a recombinant vaccine exposing CD4-inducible gp120 epitopes (including C2), strong Env-specific CD4 T-cell proliferation and even CD8 T-cell responses were observed alongside antibodies [

27]. Such cellular responses may aid in controlling infection or supporting antibody production. Thus, an ideal vaccine targeting 254–274 might elicit both arms of adaptive immunity.

Clinical Evidence and Vaccine Potential

Clinically, no standalone 254–274 peptide vaccine has yet advanced to large trials, but insights can be drawn from subunit envelope vaccine studies. Notably, the first HIV vaccine trial in the US (early 1990s) tested a recombinant gp160 protein in HIV-seronegative volunteers. Epitope-specific analyses showed that vaccination induced antibodies to the gp120 C2 region (aa 254–274) in ~39% of vaccinees, whereas such antibodies were rarely present after natural infectionjci.org. This finding demonstrated that a vaccine could uncover subdominant conserved epitopes that the natural virus often conceals. However, the neutralizing capacity of these vaccine-induced antibodies was narrow: volunteers developed neutralization against the vaccine strain (“homologous” virus) but not against divergent HIV strainsjci.orgjci.org. In essence, the gp160 vaccine successfully elicited antibodies to 254–274, but those antibodies alone did not provide broad protection. Subsequent large trials of monomeric gp120 vaccines (AIDSVAX) did not prevent HIV infection in humans, though they were later found to induce some non-neutralizing antibody functions. Notably, the partially successful RV144 trial (which combined gp120 with a viral vector) correlated protection with V1/V2 region antibodies rather than C2-specific antibodies, implying that the 254–274 response was not a dominant protective factor in that regimen. It’s possible that the monomeric gp120 immunogen in RV144 (similar to AIDSVAX) did not present the inner C2 epitope in an immunogenic way in vivo, perhaps due to conformational differences or rapid antigen clearance [

20].

On the other hand, alternative immunogen designs have shown encouraging results in primates by specifically focusing on conserved inner-domain epitopes like 254–274. A prime–boost strategy using a gp120–CD4 fusion protein immunogen (the “full-length single chain” or FLSC, which locks gp120 in a CD4-bound conformation exposing CD4i epitopes) was tested in rhesus macaques [

23]. Macaques vaccinated with this CD4i-epitope-focused immunogen had significantly better control of a SHIV challenge compared to controls: they cleared plasma viremia faster and avoided long-term viremia [

23]. Strikingly, the degree of virological control correlated with the magnitude of antibodies against CD4-induced gp120 epitopes (which include the conserved C2 region around 254–274) [

23]. This suggests that vaccine-elicited antibodies recognizing normally hidden conserved sites contributed to containment of the virus, even if those antibodies were not strongly neutralizing in standard assays [

23]. Other studies reported that these responses were associated with functional immunity – possibly through Fc-mediated mechanisms or by neutralizing the virus at the moment of CD4 engagement [

23]. While such findings need to be translated to humans, they reinforce the vaccine potential of the 254–274 epitope: when presented appropriately, it can induce an immune response that helps curtail infection. The challenge moving forward is to design vaccine candidates that reliably elicit high titers of such antibodies and to determine if they can directly protect humans against diverse HIV exposures.

Peptide Design Strategies and Delivery Systems

Designing an effective peptide vaccine targeting gp120 (254–274) requires overcoming the intrinsic hurdles of peptide immunogens. Peptide length and structure are important considerations: the 254–274 epitope is ~21 amino acids long, and in isolation it may not maintain the conformation it has in native gp120. Researchers have experimented with stabilizing this peptide by adding disulfide bonds, incorporating it into scaffold proteins, or selecting peptide analogs that adopt the desired secondary structure. NMR and molecular dynamics studies indicated this fragment can form a β-turn or helical motif depending on the environment [

19]. Vaccine designers can leverage that by constraining the peptide in a β-turn or helix conformation to mimic the real epitope structure. For instance, adding a cyclic structure or helix-promoting residues could “lock” the peptide. Alternatively, scaffold proteins that present the 254–274 sequence on a stable surface have been explored. One approach fused the C2 region into an unrelated protein loop to create a conformationally-mimicked epitope, aiming to induce antibodies that recognize the native Env. Such structure-based designs are still in experimental phases but represent a rational strategy to focus the immune response on conserved neutralization-relevant shapes.

Because short peptides alone are often poorly immunogenic (they lack the size to efficiently cross-link B cell receptors and typically do not contain T helper epitopes), delivery systems and adjuvants are critical. Conjugation to a large carrier protein like KLH or ovalbumin provides T-helper peptides and increases immunogenicity dramatically [

24]. Similarly, multiple antigen peptide (MAP) systems, in which several copies of the epitope are chemically linked to a central lysine core, have been used to create a “peptide dendrimer” that can stimulate a stronger immune response without an external carrier. These MAP constructs present repetitive B-cell epitopes – an approach known to potentiate B-cell activation. Modern nanoparticle platforms take this further: by arraying tens of copies of the epitope on a virus-like particle or synthetic nanoparticle, one can mimic the repetitive antigen display of pathogens. As mentioned, PAMAM dendrimers with attached gp120(254–274) copies yielded enhanced IgG/IgA levels in mice [

25]. Other nanocarriers like liposomes have been used to deliver HIV peptides with built-in adjuvants; for example, cationic liposomes can both present the peptide and activate immune cells. Adjuvants such as

CpG oligodeoxynucleotides,

MF59, or

AS01 can be combined with peptide vaccines to tip the immune response toward a potent, long-lasting one. In one intranasal vaccine study, co-administering the mucosal adjuvant cholera toxin B with gp120 peptides induced robust local and systemic immunity [

25]. Thus, pairing the 254–274 peptide with appropriate adjuvants (for instance, TLR agonists) and delivery systems (nanoparticles or depot-forming emulsions) is crucial for translating its intrinsic antigenicity into a strong vaccine efficacy.

Immunological Outcomes and Perspectives

Immunologically, vaccines focusing on the 254–274 epitope have consistently shown the ability to induce targeted antibody responses. These antibodies in animals often reach high titers and can recognize the native gp120 protein (not just the peptide), indicating that the linear peptide can elicit antibodies that bind the corresponding sequence on gp120’s surface [

21]. However, the quality of these antibodies must be scrutinized critically. While neutralization of laboratory strains has been documented (e.g., strains IIIB, MN neutralized by rabbit antisera [

20], neutralization breadth and potency remain modest. Many 254–274-induced antibodies are strain-specific or of low potency against primary isolates, meaning they might not prevent infection by a diverse swarm of circulating HIV variants. That said, they could still contribute to protection in vivo via mechanisms like antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or phagocytosis if the virus exposes this region during entry. Interestingly, some studies in macaques imply that even non-neutralizing CD4i-site antibodies can accelerate virus clearance, as discussed above [

23].

On the T-cell side, peptide vaccines can be formulated to include known CD8⁺ T-cell epitopes overlapping conserved regions, potentially inducing cytotoxic responses that target infected cells. The 254–274 region, being part of Env, is more relevant for CD4⁺ T-cell responses (since Env peptides are presented on MHC II by antigen-presenting cells). Indeed, the presence of 254–274-specific T helper responses was observed in some vaccinees of the gp160 protein trialjci.orgjci.org. These T cells can provide necessary help for affinity maturation of B cells. Future peptide vaccine designs might combine C2 (254–274) with conserved Gag or Pol epitopes to also drive CTL responses, creating a multi-layered defense.

From a historical perspective, the quest to harness the 254–274 epitope in vaccines has been a learning experience. Early optimism that a single conserved peptide might confer broad neutralization gave way to the realization that HIV’s conformational masking and glycan shield limit linear epitope antibody efficacy. Nevertheless, with modern immunogen design – including stabilized Env trimers and epitope-focused scaffolds – there is renewed interest in targeting cryptic conserved sites. The 254–274 region’s conservation is an advantage for coverage of global HIV strains (few if any escape mutations can occur here without fitness cost [

19]. Also, accumulating evidence suggests that in a prophylactic setting, pre-formed antibodies to this region could act at the moment HIV tries to enter cells, blocking the crucial trigger for fusion. Even if not fully sterilizing, such a vaccine-elicited response might reduce initial viral replication and give the host’s immune system a head start in controlling the infection.

In summary, the 254–274 conserved gp120 epitope remains an intriguing target for HIV vaccine development. Historically identified as an immunodominant and neutralization-relevant site, it has shown vaccine potential in various animal models. Preclinical studies demonstrate that peptide vaccines can induce antibodies to this epitope, especially when delivered with proper carriers, adjuvants, or nanoparticle platforms, and these antibodies can interfere with HIV’s infection process [

23]. Clinically, while no peptide-focused vaccine is yet in use, data from subunit Env vaccines and novel immunogens (like gp120-CD4 complexes) provide proof-of-concept that engaging this epitope can contribute to protection [

23]. Challenges remain, including improving the breadth and potency of the antibody response and ensuring the epitope is optimally exposed by the immunogen. Ongoing research into epitope-scaffold design, mRNA delivery of epitope immunogens, and multi-target vaccine cocktails will further inform how best to exploit the conserved 254–274 region. With these advances, peptide vaccines centered on this epitope could become a component of an effective strategy to neutralize HIV’s most elusive targets.

The urgent necessity for an effective vaccine has led to computational strategies for vaccine design. This study applied bioinformatic methods to identify promising antigenic regions within the gp120 envelope protein. The candidate vaccine integrates epitopes recognised by B cells, cytotoxic T cells, and helper T cells, joined by flexible linkers (GTG, GSG, GGTGG, GGGGS), and enhanced with the Gb-1 peptide as an immune stimulant. The resulting 315-amino-acid recombinant molecule, weighing approximately 35.49 kDa, exhibited structural reliability and favourable binding with Toll-like receptors in docking and simulation analyses. These characteristics suggest the vaccine construct could elicit effective antibody and cellular responses, showing promise as a preventive measure against HIV-1 [

28]. In silico immunogenicity tests predicted activation of both humoral and cellular immune responses, including the production of key antibodies such as IgA and IgG. Though the current findings are limited to computational analysis, the results offer a strong foundation for experimental development. This work supports the application of multi-epitope vaccine platforms in the ongoing pursuit of HIV-1 immunoprevention [

28].

5. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence for the effectiveness of a novel oral immunisation method based on anti-idiotypic principles. By demonstrating that systemic immune responses can be generated in mammals following ingestion of antigen-specific antibodies, the findings underscore the potential of this technique as a low-cost, accessible, and non-invasive strategy for immune modulation. As HIV remains a global health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings, this immunotherapeutic model could represent a significant advancement in vaccine innovation. Future research focusing on cellular responses and human clinical trials will be essential to validate and optimise this promising platform for widespread use.

Author Contributions

This manuscript was conceptualised by A.J.-V. and planning and discussions were conducted by all authors. All authors participated in writing the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this study is included within the manuscript and its referenced sources, ensuring comprehensive access to the relevant data for further examination and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jerne NK (1974) Towards a network theory of the immune system. Ann Immunol 125: 373-389.

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Soodeen, S.; Gopaul, D.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Thompson, R.; Unakal, C.; Akpaka, P.E. Tackling Infectious Diseases in the Caribbean and South America: Epidemiological Insights, Antibiotic Resistance, Associated Infectious Diseases in Immunological Disorders, Global Infection Response, and Experimental Anti-Idiotypic Vaccine Candidates Against Microorganisms of Public Health Importance. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 282. [CrossRef]

- Levy, D. N., & Weiner, D. B. (2023). Synthetic peptide-based vaccines and antiviral agents including HIV/AIDS as a model system. In Biologically Active Peptides (pp. 219-267). CRC Press.

- Rahman, S. (2023). Egg Yolk Antibody-IgY. In Handbook of egg science and technology (pp. 495-566). CRC Press.

- Vaillant, J., Cosme, F., Smikle, F., & Pérez, O. (2020). Feeding Eggs from Hens Immunized with Specific KLH-Conjugated HIV Peptide Candidate Vaccines to Chicks Induces Specific Anti-HIV gp120 and gp41 Antibodies that Neutralize the Original HIV Antigens. Vaccine Research, 7(2), 92-96.

- Stack, E., & O’Kennedy, R. (2014). Strategies on the use of antibodies as binders for marine toxins. Seafood and Freshwater Toxins: Pharmacology, Physiology, and Detection, 471.

- Hedegaard, C. J., & Heegaard, P. M. (2016). Passive immunisation, an old idea revisited: Basic principles and application to modern animal production systems. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 174, 50-63.

- Grzywa, R., Łupicka-Słowik, A., & Sieńczyk, M. (2023). IgYs: on her majesty’s secret service. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, 1199427.

- Lee, L., Samardzic, K., Wallach, M., Frumkin, L. R., & Mochly-Rosen, D. (2021). Immunoglobulin Y for potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications in infectious diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 12, 696003.

- Nisonoff, A. (1991). Idiotypes: concepts and applications. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 147(8), 2429-2438.

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pooransingh, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Asin-Milan, O.; Akpaka, P.E. Advancements in Immunology and Microbiology Research: A Comprehensive Exploration of Key Areas. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1672. [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, E. C., & Ward, R. W. (2022). Mucosal vaccines—fortifying the frontiers. Nature Reviews Immunology, 22(4), 236-250.

- Ciabattini, A., Olivieri, R., Lazzeri, E., & Medaglini, D. (2019). Role of the microbiota in the modulation of vaccine immune responses. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, 1305.

- Aroffu, M., Manca, M. L., Pedraz, J. L., & Manconi, M. (2023). Liposome-based vaccines for minimally or noninvasive administration: an update on current advancements. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery, 20(11), 1573-1593.

- Zhou, X., Wu, Y., Zhu, Z., Lu, C., Zhang, C., Zeng, L., ... & Zhou, F. (2025). Mucosal immune response in biology, disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 10(1), 7.

- Jorge, S., & Dellagostin, O. A. (2017). The development of veterinary vaccines: a review of traditional methods and modern biotechnology approaches. Biotechnology Research and Innovation, 1(1), 6-13.

- Grossman Z. (2019). Immunological Paradigms, Mechanisms, and Models: Conceptual Understanding Is a Prerequisite to Effective Modeling. Frontiers in immunology, 10, 2522. [CrossRef]

- Zaghouani, H., Hall, B., Shah, H., Bona, C. (1991). Immunogenicity of Synthetic Peptides Corresponding to Various Epitopes of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Envelope Protein. In: Atassi, M.Z. (eds) Immunobiology of Proteins and Peptides VI. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 303. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Kanyalkar, M., Srivastava, S., Saran, A., & Coutinho, E. (2004). Conformational study of fragments of envelope proteins (gp120: 254-274 and gp41: 519-541) of HIV-1 by NMR and MD simulations. Journal of peptide science : an official publication of the European Peptide Society, 10(6), 363–380. [CrossRef]

- Ho, D. D., Kaplan, J. C., Rackauskas, I. E., & Gurney, M. E. (1988). Second conserved domain of gp120 is important for HIV infectivity and antibody neutralization. Science (New York, N.Y.), 239(4843), 1021–1023. [CrossRef]

- Vahlne, A., Syennerholm, B., Rymo, L., Jeansson, S., & Horal, P. (1998). U.S. Patent No. 5,840,313. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Profy, A. T., Salinas, P. A., Eckler, L. I., Dunlop, N. M., Nara, P. L., & Putney, S. D. (1990). Epitopes recognized by the neutralizing antibodies of an HIV-1-infected individual. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), 144(12), 4641–4647.

- DeVico, A., Fouts, T., Lewis, G. K., Gallo, R. C., Godfrey, K., Charurat, M., Harris, I., Galmin, L., & Pal, R. (2007). Antibodies to CD4-induced sites in HIV gp120 correlate with the control of SHIV challenge in macaques vaccinated with subunit immunogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(44), 17477–17482. [CrossRef]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A. (2020). Chicken immunization with Keyhole limpet hemocynin (KLH)-gp120 fragment (254-274) conjugate raises anti-KLH antibodies in egg yolks..protocols.io. [CrossRef]

- García-Machorro, J., Gutiérrez-Sánchez, M., Rojas-Ortega, D. A., Bello, M., Andrade-Ochoa, S., Díaz-Hernández, S., ... & Rojas-Hernández, S. (2023). Identification of peptide epitopes of the gp120 protein of HIV-1 capable of inducing cellular and humoral immunity. RSC advances, 13(13), 9078-9090.

- Berkower, I., Raymond, M., Muller, J., Spadaccini, A., & Aberdeen, A. (2004). Assembly, structure, and antigenic properties of virus-like particles rich in HIV-1 envelope gp120. Virology, 321(1), 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Chua, J. V., Davis, C., Husson, J. S., Nelson, A., Prado, I., Flinko, R., ... & Sajadi, M. M. (2021). Safety and immunogenicity of an HIV-1 gp120-CD4 chimeric subunit vaccine in a phase 1a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine, 39(29), 3879-3891.

- Habib, A.; Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhu, N.; Xie, J. Immunoinformatic Identification of Multiple Epitopes of gp120 Protein of HIV-1 to Enhance the Immune Response against HIV-1 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2432. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).