1. Introduction

As of May 2022, an unexpected mpox epidemic caused by the clade IIb spread in 122 countries with a global case count higher than 99.000 [

1]. The rapid increase in confirmed cases led to the subsequent declaration of mpox as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

2]. Therefore, the WHO recommended vaccination for high-risk people and other mitigation strategies to control the epidemic [

3].

Licensed vaccines against mpox consist of two doses of the third-generation replication-deficient modified vaccinia Ankara produced by Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) [

4,

5]. The standard route of administration of MVA-BN is subcutaneous (SC), with two doses delivered at least 28 days apart.

The safety and immunogenicity of the standard SC formulation (dose and route) of MVA-BN vs. the intradermal (ID) administration of one-fifth of the standard SC dose was compared in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) [

6]. Although the proportion of local reactions was significantly higher after ID inoculation than that seen with SC, the ID route was considered non-inferior to the SC route regarding neutralization against vaccinia virus, and it was purposed as a valid alternative in the event of an emergency requiring the availability of more doses [

7].

In the summer of 2022, it became necessary to rapidly vaccinate as many high-risk people as possible to contain the epidemic [

8]. Therefore, due to the limited availability of MVA-BN worldwide, the European Medicine Agency and Food and Drugs Administration authorized using the ID of administration with a reduced dose to extend vaccination [

9,

10].

Data from large-scale administration of MVA-BN published by Bavarian Nordic confirmed the overall safety of the vaccine with an increased frequency of syncopal events after ID administration [

11].

Recently, Frey et al. reported data from a phase-2 open-label trial comparing two 2-dose ID regimens of MVA-BN (one-tenth and one-fifth of SC, respectively) with the standard dose SC regimen. MVA-BN administrated ID at fractional doses was safe, and the vaccination with one-fifth (but not one-tenth) dose demonstrated non-inferior immunogenicity by vaccinia virus (Western Reserve strain) plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) after 43 days [

12]. However, even though little evidence for a difference clinical effectiveness of the two different vaccination schedules against mpox was reported from 2022 real-world data [

13], comparative data on the immunogenicity of ID route compared to SC are lacking and, those available are not informative on the humoral response specifically against mpox, nor on the T-cell response.

Although the massive vaccination campaigns during the MPXV Clade IIb outbreak has helped to control the epidemic in high-income countries [

14], many outbreaks were constantly observed in endemic areas during the last year, especially in South Africa, where Clade IIb of mpox virus (MPXV) was still detected [

15] and in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the Clade I had acquired the capability of human-to-human transmission through the sexual route [

16], and it has spread in some neighboring countries where mpox cases have never been reported before (e.g Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda) [

17]. Furthermore, this “new sexually transmitted clade”, named Clade Ib, is particularly worrisome because of its lethality (nearly 3%) [

18], leading WHO to renew the declaration of mpox as a PHEIC on the 14th of August 2024 [

17].

Vaccination is recommended as one of the main tools to control this new increase in mpox cases. WHO and the African Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are producing efforts to step up the vaccination campaign in low-income countries with limited access. Although it has been estimated by the African CDC that 10 million doses will be needed to contain the current outbreak, the negotiations with Bavarian Nordic aim to obtain around 200.000 doses of MVA-BN [

19]. In this setting, enhancing knowledge about the reactogenicity and immunogenicity against MPXV of the ID-sparing strategy compared to the standard SC in people at high-risk of acquiring mpox in the real-world setting is crucial to address an efficient and cost-effective implementation of the arising mpox vaccination campaign.

Here, we report the results of an analysis of observational data comparing the safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity (neutralization and T-cell response) specifically directed against the MPXV target between the two vaccination schedules of MVA-BN (Jynneos) delivered during the mpox outbreak and consequent vaccination campaign in Italy over 2022-2023.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients’ Enrolment

In the Lazio Region of Italy mpox vaccination campaign started on August 8th, 2022, and took place in a hospital setting at the Lazzaro Spallanzani National Institute for Infectious Diseases in Rome, which was identified as the only vaccination center in the entire region.

According to the recommendations of the Ministry of Health [

20], MVA-BN was administered as pre-exposure prophylaxis to a target population, including laboratory personnel with possible direct exposure to orthopoxviruses (OPXV) and high-risk gay-bisexual-men who have sex with men (GBMSM), defined as individuals reporting a recent history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), multiple sexual partners or participation in group sex events, sexual encounters in clubs/cruising/saunas or sexual acts associated with the use of Chemical drugs (Chemsex). For individuals who had never received the smallpox vaccine (vaccine-naïve or non-primed), the vaccination schedule consisted of a two-dose cycle with a 28-day interval between each dose, while individuals who had received the smallpox vaccine in the past (vaccine-experienced or primed) were administered a single-dose cycle. Of note, in Italy, the smallpox vaccination campaign was stopped in 1977 and officially abrogated in 1981 [

21].

The MVA-BN first dose was administered subcutaneously during the first two weeks of the vaccination campaign, after which the intradermal route was adopted, following the ministerial indications [

22].

For the same reason, the vaccine was administered exclusively using the ID route in those receiving a second dose. A prospective observational cohort was integrated into the framework of this vaccination campaign. Not all patients included in this analysis had available data for all the outcome parameters studied. The majority contributed only a diary with recorded adverse events data, a minority only immunogenicity data and some contributed to both. Reasons for missing data outcomes included convenience, costs and laboratory failure results.

2.2. Study Protocol

The protocol for the study named Mpox-Vac (“Studio prospettico osservazionale per monitorare aspetti relativi alla sicurezza, all’efficacia, all’immunogenicità e all’accettabilità della vaccinazione anti Monkeypox con vaccino MVA-BN (JYNNEOS) in persone ad alto rischio”) was approved by the INMI Lazzaro Spallanzani Ethical Committee (approval number 41z, Register of Non-Covid Trials 2022). The study protocol was previously described in detail elsewhere [

23].

Briefly, all subjects eligible for mpox vaccination according to the ministerial guidelines and who signed a written informed consent were enrolled in the study. Data measured in laboratory personnel were excluded from the analysis. At baseline (when receiving the first MVA-BN dose, T1), subjects were evaluated for demographic and behavioral characteristics linked to mpox exposure. Information regarding HIV status, CD4 count, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and any history of previous STIs was collected. In non-primed participants, other time points were scheduled at the administration of the second dose (T2) and one month after the completion of the cycle (T3). For the vaccine-experienced individuals (primed) who received a single-dose schedule as a complete vaccination cycle, T2 was the time point corresponding to one month after vaccination completion.

2.3. Assessment of Adverse Reactions

As part of the protocol, participants were delivered a paper symptoms diary after each vaccine dose (T1 and T2) to collect self-reported adverse effects following immunization (AEFIs) for 28 consecutive days (the 28 days following T1 and the 28 days following T2). Participants returned the completed diaries at their next day appointment. Because the SC route was never used as second dose, safety and reactogenicity by administration route could only be compared 28 days after T1. Those who agreed to collect their diary were included in the Group 1 sub-group analysis.

Participants were able to report the presence of systemic symptoms (S-AEFIs) classified as fatigue, muscle pain, headache, gastrointestinal effects, and chills, and local injection site symptoms (LIS-AEFIs), such as redness, induration, and pain. AEFIs were graded by the vaccinees as absent (grade 0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3). Here, we report the results regarding erythema and induration as recalculated with the use of the current FDA Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials. According to that scale, a diameter of 25 to 50 mm indicates a mild reaction, 51 to 100 mm is a moderate reaction, and more than 100 mm is a severe reaction [

24].

2.4. Assessment of Immunogenicity

In a specific population of participants for whom blood samples collected at each time point were available, the assessment of the early humoral and cellular immune response was performed (Group 2). Blood samples were collected from eligible participants who gave a specific consent to blood collection at T1 and T2, independently to the participation to the report of the presence of adverse events above described.

2.4.1. MPXV-Specific IgG and Neutralization Assays

Specific anti-MPXV immune response was evaluated by measuring MPXV-specific IgGs and neutralizing antibodies in the serum as previously described [

25]. The presence of anti-MPXV IgGs was assessed on immunofluorescence slides in-house prepared with Vero E6 cells (ATCC) infected with an MPXV isolated from the skin lesion of a patient infected with MPXV during the 2022 outbreak (GenBank: ON745215.1, referred to the clinical sample). Serum samples were tested with a starting dilution of 1:20, and serial two-fold dilutions were performed to determine anti-MPXV IgG titer. MPXV-specific neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) were measured by 50% plaque-reduction-neutralization test (PRNT

50) with a starting dilution of 1:10. Specifically, serum samples were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and titrated in duplicate in 4 four-fold serial dilutions. Each serum dilution was added to the same volume (1:1) of a solution containing 100 TCID

50 MPXV isolate (GenBank: ON745215.1, referred to the clinical sample) and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Subconfluent Vero E6 cells were infected with virus/serum mixtures and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. After 5 days, the supernatant was carefully discarded, and a crystal violet solution (Diapath S.P.A.) containing 10% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) was added for 30 min, then cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 1X; Sigma-Aldrich). Using the Cytation 5 reader (Biotek), the number of plaques was counted. The neutralizing titers were estimated by measuring the plaques number reduction as compared to the control virus wells. The highest serum dilution showing at least 50% of the plaque number reduction was indicated as the 50% neutralization titer (PRNT

50). Each test included serum control (1:10 dilution of each sample tested without virus), cell control (Vero E6 cells alone), and virus control (100 TCID

50 MPXV in octuplicate).

2.4.2. PBMC Isolation

Using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Pancoll human, PAN Biotech) methodperipheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated, frozen in FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum, Gibco, USA) added of 10% of DMSO (Merck Life sciences, Milan, Italy) at vapors of liquid nitrogen for further experiments.

2.4.3. Elispot Assay

The frequency of T-cell-specific responses to the MVA-BN vaccine was assessed by Interferon-γ ELISpot assay. Briefly, PBMC were thawed and suspended in a complete medium [RPMI-1640 added of 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Euroclone S.p.A, Italy)]. Live PBMC were counted by Trypan blue exclusion, plated at 3x105 cells per well in ELISpot plates (Human IFN-γ ELISpot plus kit; Mabtech, Nacka Strand, Sweden), and stimulated for 20 h with MOI 1 of the MVA-BN vaccine suspension [JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, non-replicating)] and anti-CD28/ anti-CD49d (1 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) at 37 °C (5% CO2), using T cell superantigen (SEB 200 nM, Sigma) as positive control. At the end of the of incubation, the ELISpot assay was developed following manufacturer’s instructions. Results are expressed as spot-forming cells per 106 PBMCs (SFC/106 PBMCs) in stimulating cultures after subtracting the background (unstimulated culture).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Demographic and epidemiological characteristics of the patients are presented both for the overall sample population and after stratification by route of administration. Continuous variables were described using median and Interquartile Range (IQR), while categorical variables were summarized using absolute numbers and percentages.

The main characteristics of participants according to the route of administration were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test when appropriate for qualitative variables and the Mann-Whitney or Kruskall-Wallis test for numerical variables. We then used collected diaries to calculate the prevalence of reported AEFIs within 28 days after T1 according to the route of administration, as well as the duration and maximum level of severity ever experienced over the 28 days following T1 for each S-AEFI and LIS-AEFI, according to the above-mentioned grading (none to severe).

The raw proportions of participants whose maximum reported AEFIs was none, mild, moderate or severe are also shown by route of administration. We also computed the Odds ratio (OR) of the maximum severity level of AEFIs experienced by the administration route using multinomial logistic regression models, both univariable and after adjusting for age and HIV status. In these models, the never-reported AEFIs category was chosen as the reference group, and the estimated ORs show the risk of reporting mild, moderate or severe AEFIs as the maximum level ever experienced vs. none according to the administration route. For a proportion of participants, the diary data were censored at day six, so we have also performed a sensitivity analysis after restricting to only the level of AEFI severity ever experienced over the six days following T1.

As a second continuous outcome, we calculated the average number of days in which participants experienced each of the 4 levels of symptoms over the 28 days following T1. We then compared the average duration in days of any systemic or local reactions by route of administration by means of an unpaired t-test. Also, in this analysis, we compared the mean duration of any grade of reaction (from mild to severe, grade 1 to 3) and after restricting to moderate/severe grades (2 or 3). For these analyses with continuous outcomes instead of using a standard regression model adjusted for covariates (like for the categorical endpoint above), we aimed to emulate a randomized comparison of the ID vs SC first dose strategy. Specifically, we calculated counterfactual estimates of what would have been the average duration of any adverse response to the MVA-BN vaccine had everybody in the sample received the ID vs. had everybody received the SC route of administration instead (the average treatment effect – ATE). We used a doubly robust method (using augmented inverse probability weighting-AIPW) to obtain estimates which are robust against misspecification of either the propensity model or the outcome model. Both the propensity and outcome models included HIV and age as confounding variables. Because of the collinearity between being primed and age we did not further control for the imbalance in proportion of participants who had been primed. For the outcome model, we also used the saturated model, including the interaction parameter between exposure and HIV status (results were similar, not shown).

Finally, the same approach to analysis (a marginal model and the calculation of the ATE after weighting for HIV and age) was conducted in the population vaccinated subjects for whom stored samples were available and analyzed to compare the overall increase in the average levels (on a log2 scale) of IgG and nAb as well as ELISPOT response 1 month after the complete vaccination cycle according to route of the first dose administration (a single dose for the primed but two doses for the non-primed participants). The strategies were classified according to the type of the inoculation used as first dose – as none of the non-primed used SC as second dose. In other words, the exact strategies being compared in this second part of the emulation analysis were homologous (ID+ID) vs. heterologous (SC+ID) complete course of vaccination.

In addition, we also described the raw immunogenic response data feeding this analysis by plotting the geometric mean titers (GMT) or SFC at T1 and T2 and the average change over T1-T2 stratified by strategy received under the natural course. The crude mean T1-T2 change was compared by strategy using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for unpaired data.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

Between August 8th and December 31st, 2022, 3,296 individuals received at least one dose of MVA-BN, of which 654 (19.8%) received the first dose via SC route and 2,642 (80.2%) via ID route (see

Supplementary Figure S1).

Among these, 1,008 (30.6%) agreed to be enrolled either completing the symptom diary and/or accepting to consent blood collection at T1 and T2.

Supplementary Table S1 show the characteristics of these 1,008 subjects, of which 269 (26.7%) vaccinated through SC route. Overall, 783 subjects (77.7%) completed the diary, 160 (15.9%) completed the diary and were tested for immunogenicity of vaccine and 65 (6.5%) did not complete diary but they had blood samples available which were tested, and the results were included in the immunogenicity study (see

Supplementary Figure S1). There was weak evidence for a difference in key outcome predictors between populations according to data availability and contribution, suggesting that random selection due to convenience and costs have occurred.

For the analysis, we split the population in two groups: those who could be included in the analysis of diary data (n=943, Group 1) and those with available test results from the blood samples stored 1 month after the complete vaccination cycle (n=225, Group 2).

Among the 943 individuals included in Group 1, 225 (23.9%) received the first dose via the SC route, of whom 26 as a single dose because they were vaccine-experienced (11.6% of this group), and 718 (76.1%) via the ID route; of this latter group 99 (13.8%) received only the first of the two doses scheduled for the previously unvaccinated.

All were male, and the majority (90.9%) self-identified as MSM. Overall, the median age was 44 years (IQR 36-51), 43 (36-48) years in the SC group, and 45 (38-52) years in the ID, respectively (p=0.15). Regarding other characteristics, 167 participants (17.7%) were on PrEP, 227 (24.1%) reported at least one STI diagnosed within the previous year, and 261 subjects (27.7%) were people living with HIV (PLWH), all on highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV infection was more prevalent in the SC (35%) vs. the ID group (25%, p=0.0004). In those with HIV, CD4-cell count was lower than 200 cells/µL only in 10 participants (3.8%), while it was higher than 500 cells/µL in 211 (80.8%), with no evidence for a difference between the two groups (p=0.232). In contrast, data carried evidence for a difference between strategies according to the use of PrEP (25.8% vs. 15.2%, for SC and ID groups respectively, p<0.001) and in the proportion of participants who reported one or more comorbidities (0% vs. 8.2%, for SC and ID group, respectively, p<0.001), while there was no evidence for a difference in all other examined factors (i.e. sexual orientation, history of STI other than HIV, CD4 counts for those with HIV, and history of smallpox vaccination.

The main characteristics of the study population belonging to Group 1, according to the administration route, are reported in more detail in

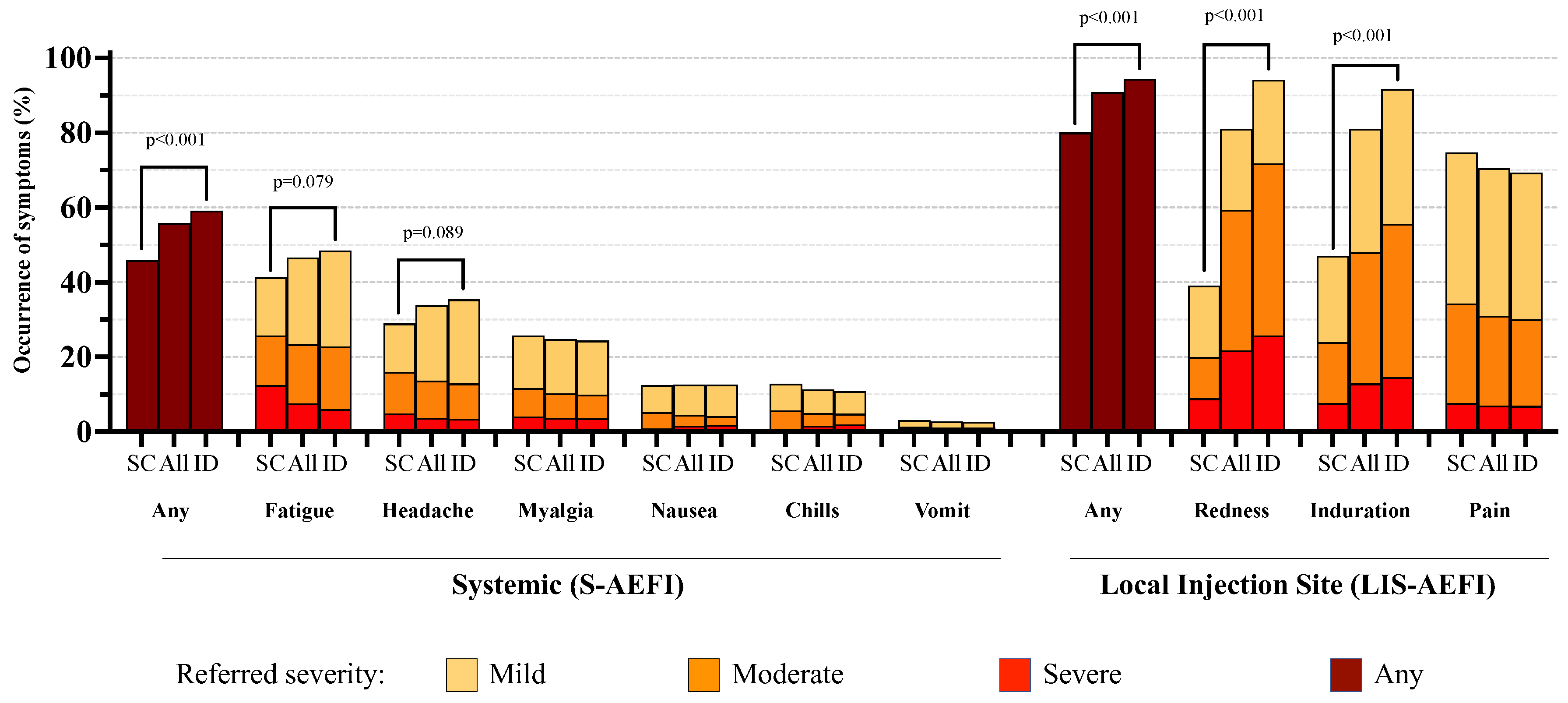

Table 1. The crude proportions of participants reporting various grades of the evaluated adverse effect are reported in

Figure 1 and

Table 2.

3.2. Systemic Reactions

No serious adverse events were observed over the 28-day follow-up. Overall systemic reactions occurred in 526 (55.9%) participants, with a higher proportion observed in the ID group compared to the SC group (59.1% vs 45.8%, p<0.001). The most common S-AEFIs were fatigue and headache, occurring in 46.7% and 33.8% of participants, which appeared to be slightly higher in the ID group (p=0.08 and p=0.09, respectively); however, when considering only moderate or severe grades, there was no evidence for a difference between the two groups.

After adjusting for age and HIV status in a multinomial regression model, we found evidence that participants in the ID group had an increased risk of developing mild-grade headaches (2.91; 95% Confidence Interval, 95% CI: 1.23,6.89; p=0.045) compared to the SC group (

Table 3). Results were similar after restricting the analysis only to the first 6 days of the diary (OR=2.66, 95% CI:1.13-6.27, p=0.07), suggesting that most of the difference is likely to occur early after vaccination (

Supplementary Table S2).

Systemic reactions were of short duration, 3.7 days on average for any grade and any type of S-AEFI, with no evidence for a difference in symptom duration between the ID and SC groups in the unadjusted analysis and after controlling for HIV and age (

Table 4).

3.3. Local Reactions

LIS-AEFIs were reported by a total of 852 (90.9%) participants, with a higher proportion in those receiving the ID route (94.4% vs 80.0%, p<0.001).

Among LIS-AEFIs, redness and induration at the injection site were the most frequently reported adverse effects (80.9% and 81.0%, respectively), with a significantly higher proportion (about twice as high) in the ID group than in the SC group (p<0.001); a similar difference was also observed considering only moderate or severe grade adverse events (

Table 2).

In contrast, 74.7% of participants in the SC group reported any-grade pain at the injection site vs. 69.2% in the ID group, although there was no evidence for a difference (p=0.14); the same applied when considering moderate or severe grade pain (34.2% vs. 30.1%, p=0.13).

After controlling for HIV and age, we found a higher risk of occurrence for any grade of redness and induration at the local site in the ID than in the SC group (p<0.001). Conversely, a higher degree of pain was reported by participants who received the vaccine through the SC modality (p<0.002). ORs with 95% CI from fitting the multinomial regression models are reported in

Table 3. Results were similar after restricting the analysis to the 0-6 days diary data (

Supplementary Table S2).

Local redness and induration (regardless of grade) were the most long-lasting symptoms, especially in the ID group (on average, 18.7 and 16.6 days in ID vs. 5.9 and 5.5 in the SC group, respectively).

After controlling for HIV status and age, we estimated that the duration of redness (regardless of grade) in participants who received the vaccine in ID modality was 12.8 days (95% CI: 9.96, 15.55; p < 0.0001) longer than that of subjects receiving the SC strategy. Similar results were observed for induration, which lasted on average 11.1 days (95% CI: 8.45, 13.7; p < 0.0001) longer in the ID vs. SC strategy. After restricting the analysis to only moderate or severe grades, we observed a shorter duration of these AEFIs, although still significantly longer in the ID vs. SC group (7.14 vs. 4.24 days for redness, p=0.023 and 5.55 vs. 3.23 days for induration, p=0.004). Overall, local pain (regardless of grade) had a shorter duration, not exceeding 7 days on average, but still with a longer duration in the ID vs. SC group (mean difference 1.8 days (95% CI: 0.2, 3.4; p=0.025) in the unadjusted analysis, which was however largely attenuated after considering only moderate and severe grade and controlling for age and HIV-status (p=0.312,

Table 4).

4.4. Immunogenicity

Finally, Group 2 consisted of 225/1,008 (22.3%) vaccine recipients for whom samples have been stored and analysed: In this population, we compared the average change in immunogenicity one month after the completion of the vaccination cycle according to the route of administration (ID vs SC) both using the raw data and using a counterfactual marginal model.

Within Group 2, the proportion of primed participants was higher in those who received the vaccine through the ID- vs the SC-route (48% vs 37%, p=0.03,

Table 5). There was no evidence for an imbalance in other factors between strategies received under the natural course.

The crude analysis of the raw immunogenicity data showed some evidence for a larger increase of MPXV-specific IgG (GMT, p=0.04) and nAb titers (GMT, p=0.05) in favour of the ID vs. SC administration. While weaker evidence for a difference by administration route was found in the variation of MVA-BN specific T-cell response measured by Elispot assay (p=0.1776) (see

Supplementary Figure S3).

Results were confirmed by our trial emulation analysis weighted for age and HIV status, showing the following mean differences in the log

2 scale: (0.26 log

2, p=0.05 for MPXV-specific IgG) and (0.34 log

2, p=0.08 for nAb titers) and (0.36 log

2, p=0.25 for MVA-BN specific T-cell response measured by Elispot assay,

Table 6).

4. Discussion

Our analysis shows that in our study population the ID route of administration of the MVA-BN vaccine was safe and well tolerated despite higher reactogenicity than the SC route. We did not observe serious adverse effects or syncope, as recently reported by the manufacturer [

11]. However, among the participants receiving the vaccine ID, we observed a slightly higher prevalence of headache and fatigue than in the SC group. This difference, already mild in the unadjusted analysis, was further attenuated after controlling for the potential confounding effect of age and HIV status. Local redness and induration were confirmed to be more prevalent (94%) and long-lasting (around 18 days) among participants receiving the ID route than those receiving the SC route. On the contrary, pain was more common after SC administration. These findings are quite expected considering the modality of inoculation and are consistent with those of reports. Recently, Frey et al. reported proportions of adverse effects in people receiving the ID dose of 97% for the local and 79% for the systemic symptoms, and no severe grade events. Moreover, local symptoms lasted over a month after the intradermal administration [

12].

Although expected and not severe, redness and induration in the forearm were not well accepted by vaccinated people because they were considered a mark of vaccination and, consequently, of sexual behaviour associated with a high risk of contracting mpox.

Stigma could represent a barrier to vaccination, especially in countries where discrimination and racism are deep-rooted, and the LGBT community is criminalized [

26]. Luckily, MVA-BN can also be inoculated intradermally into the upper back just below the shoulder blade or into the skin of the shoulder above the deltoid muscle [

27], where the spot is less visible than in the forearm. Knowledge of these data might help clinicians provide more appropriate counselling, make people aware of the course of side effects, and, therefore, make vaccination more acceptable and sufficiently widespread enough to protect the “core group” who sustains the virus transmission and contributes to its possible spread to the general population [

28].

Regarding immunogenicity, our data collected one month after completing the vaccination cycle found a substantially equivalent immune response between the participants receiving the first dose intradermally and those receiving it subcutaneously. Differently from previously published data, analysing humoral immune response against vaccinia virus (VACV, not MPXV) [

15], we measured both titers of specific IgG and nAbs against MPXV, and we found that slightly higher titers of MPXV IgG and nAbs were elicited after the homologous (ID+ID) course of vaccination that after the heterologous (SC+ID) one.

These findings may at least partly explain the results of a report from a study conducted over May 2022 to May 2024 in the USA, showing a higher incidence of breakthrough infections among people fully vaccinated with the heterologous than the homologous ID vaccination cycle. However, of note, in our cohort, we did not observe breakthrough infections [

29].

Finally, ours is the first analysis providing data regarding the cellular immune response according to the administration route of MVA-BN. There was no evidence for a difference in the cellular immune response between participants receiving the first dose intradermally or subcutaneously. T-cell response has been known to be crucial for the control and resolution of poxvirus infections [

30,

31], and T-cell reactivity to VACV and MPXV was detected decades post-vaccination with first-generation vaccine, suggesting a role of long-lasting cross-reactive T-cell memory responses in vaccine efficacy [

32]. A good T-cell response was also demonstrated after third-generation MVA-BN [

33]. T-cells elicited from VACV-based vaccines were found to recognize MPXV-derived epitopes, suggesting that it is crucial for the cross-reactivity between different Orthopox strains [

34]. Consequently, T-cells could contribute to the recognition of the different MPXV clades and to a broader vaccine efficacy. Interestingly, we found no evidence for a difference in the cellular immune response between participants receiving the first dose intradermally or subcutaneously and therefore our data are consistent with no benefit in using one strategy over the other to achieve long-term cross-reactive impact.

Recently, the Afro-Mpox bulletin showed a spreading outbreak involving several African countries, and clade Ib and clade IIb have been sequenced [

35]. On balance, although confirmatory studies performed in people infected with the clade Ib are needed, in the wake of our reactogenicity and IgG and nAbs responses data, we support the use of vaccination by MVA-BN administered by an ID route in low-income countries, as already recommended by WHO [

17]. One advantage of this strategy lies in the fact that the sparing-dose protocol of ID-based vaccination provides a cost-effective approach to the current global vaccination campaign.

Before drawing firm conclusions some limitations need to be stated. First, the study's observational design could not account for unmeasured bias, although the analysis was controlled for the main measured confounders. Furthermore, we were not able to compare the two homologous cycles (SC+SC vs ID+ID) because the second doses were only administered intradermally due to the regulatory recommendations. For this reason, for the diary data we have limited the comparison to the first dose while for the immunogenicity response we compared the full cycles SC+ID vs ID+ID. Although we found a difference in IgG and nAbs response which was not consistent with the null hypothesis of no difference by strategy and potentially reflects the causal effect of using ID vs SC as first dose it is difficult to attach a clinical meaning in terms of risk of infection to the magnitude of the difference found. As mentioned, although we extensively assessed the immune response against MPXV clade IIb, we cannot provide at this stage information on the humoral and cellular response against Clade I.

In conclusion, our study shows that the ID route of administration of MVA-BN appears to elicit higher titers of MPXV-specific IgG and nAbs than the SC route. At the same time, we found no evidence for a difference in cellular response by strategy. MVA-BN was globally well tolerated despite higher reactogenicity with the ID than the SC route. Based on these results, we believe that ID administration of MVA-BN is feasible, safe, and immunogenic, and our data support the use of this dose-sparing strategy to increase the feasibility of a broad vaccination campaign to control the current multiclade mpox outbreak in Africa.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org,

Supplementary Figure S1. Flow-chart showing overall vaccinated subjects and study participants, according to route of administration of the first MVA-BN dose (Sub-cutaneous, SC or Intra-dermal route, ID) and availability of data (from symptom-reporting daily diary and/or data from blood samples).

Supplementary Table S1. Main characteristics of participants according to availability of data from symptom-reporting daily diary and/or data from blood samples.

Supplementary Figure S2. Heatmap summarizing grade and duration of Systemic (Panel a) and Local Injection Site (Panel b) Adverse Effect Following Immunisation (S-AEFI and LIS-AEFI) with MVA-BN Vaccine within 28-days from vaccination according to route of vaccination [Sub-cutaneous (SC): N=225; Intra-dermal (ID): N=718]. Every row represents results for a participant between Days 1-28 which are presented as columns. Cells are color-coded by severity.

Supplementary Table S2: Prevalence and risk of developing different grades of Systemic and Local Adverse Effects Following Immunisation (S-AEFIs and L-AEFIs) with MVA-BN Vaccine up to six days from fitting a multinomial logistic regression according to administration route - intradermal (ID) vs subcutaneous (SC).

Supplemental Figure S3: MPXV-specific antibodies response (IgG, Panel A), MPXV-specific neutralizing antibodies response (nAbs, Panel B) and frequency of T cells responding to MVA-BN vaccine expressed as the number of Forming colonies (SFC x10

6 PBMC) tested by interferon-γ ELISpot assay (Panel C) in sub-cutaneously administered (red plot) vs. intra-dermal administered (blue plot). Panel A. Titers of MPXV-specific IgG were measured by immunofluorescence (1:20) starting dilution. Panel B. Titers of MPXV-specific nAbs were measured by 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT

50, 1:10 starting dilution). Titers are expressed as Geometric Mean Titres (GMT) of the reciprocal serum dilution (log

2 scale). On the right part of each panel, the comparison of fold-change of antibody titers or number of SFC (on the log

2 scale) are shown together with the Mann-Whitney test result. The horizontal lines refer to the median.

Author Contributions

V.M., A.A., and A.C.L. conceived the study; V.M., G.Ma., E.C., and F.C. wrote the protocol. P.P. and V.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.A., F.M., A.C.L., E.C., G.Ma., F.C., E.G., E.N. and C.F. revised the manuscript. G.Ma., F.C., S.M., L.B., S.N., R.C., and G.G. performed the laboratory analyses. P.P., J.P., A.C. and C.C. were responsible for data management. P.P. and A.C.L. performed statistical analysis. V.M., R.E., A.G., G.M., A.O., S.G.T., G.D.D. and R.G. enrolled and followed the patients during the study time points. M.L., L.S., E.T., C.M., and A.L. contributed to the enrolment. P.G., A.S., F.V., P.F. and A.B. contributed to the realization of the study. V.M. and A.A. provided the grant for funding the study. All authors gave their final approval of the submitted version.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Institute for Infectious Disease Lazzaro Spallanzani IRCCS “Advanced grant 5x1000, 2021” and by the Italian Ministry of Health “Ricerca Corrente Linea 2” INMI Spallanzani IRCCS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol for the study named Mpox-Vac (“Studio prospettico osservazionale per monitorare aspetti relativi alla sicurezza, all’efficacia, all’immunogenicità e all’accettabilità della vaccinazione anti Monkeypox con vaccino MVA-BN (JYNNEOS) in persone ad alto rischio”) was approved by the INMI Lazzaro Spallanzani Ethical Committee (approval number 41z, Register of Non-Covid Trials 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who gave their time to the project, the nurse, the laboratory staff, and the bio-banking personnel. Thanks to all the members of the Mpox Vaccine Lazio Study Group: C Aguglia, A Antinori, E Anzalone, A Barca, M Camici, F Cannone, P Caputi, R Casetti, L Caterini, C Cimaglia, E Cimini, F Colavita, L Coppola, R Corso, F Cristofanelli, S Cruciani, N De Marco, G Del Duca, G D’Ettorre, S Di Bari, S Di Giambenedetto, P Faccendini, F Faraglia, D Farinacci, A Faticoni, C Fontana, M Fusto, R Gagliardini, P Gallì, S Gebremeskel, G Giannico, S Gili, E Girardi, G Grassi, MR Iannella, A Junea, D Kontogiannis, A Lamonaca, S Lanini, A Latini, D Lapa, M Lichtner, MG Loira, F Maggi, A Marani, M Marchili, R Marocco, A Masone, C Mastroianni, I Mastrorosa, G Matusali, V Mazzotta, S Meschi, S Minicucci, A Mondi, V Mondillo, A Nappo, G Natalini, E Nicastri, S Notari, A Oliva, A Parisi, J Paulicelli, C Pinnetti, P Piselli, MM Plazzi, A Possi, G Preziosi, R Preziosi, G Prota, M Ridolfi, S Rosati, A Russo, L Sarmati, P Scanzano, L Scorzolini, C Stingone, E Tamburrini, E Tartaglia, V Tomassi, F Vaia, A Vergori, M Vescovo, S Vita, J Volpi, P Zuccalà.

Conflicts of Interest

AA received a grant from Bavarian Nordic for participation in conferences. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox in the United States and Around the World: Current Situation. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/situation-summary/index.html (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO director general declares the ongoing monkeypox outbreak a public health event of international concern (2002). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/23-07-2022-who-director-general-declares-the-ongoing-monkeypox-outbreak-a-public-health-event-of-international-concern (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Hubach, R.D.; Owens, C. Findings on the Monkeypox Exposure Mitigation Strategies Employed by Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in the United States. Archives of sexual behavior 2022, 51, 3653–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency (2022). EMA recommends approval Imvanex prevention monkeypox disease. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-approval-imvanex-prevention-monkeypox-disease (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Food and Drug Administration (2019). BLA approval. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/131079/download?attachment (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Frey, S.E.; Wald, A.; Edupuganti, S.; Jackson, L.A.; Stapleton, J.T.; El Sahly, H.; El-Kamary, S.S.; Edwards, K.; Keyserling, H.; Winokur, P.; Keitel, W.; Hill, H.; Goll, J.B.; Anderson, E.L.; Graham, I.L.; Johnston, C.; Mulligan, M.; Rouphael, N.; Atmar, R.; Patel, S.; et al. Comparison of lyophilized versus liquid modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) formulations and subcutaneous versus intradermal routes of administration in healthy vaccinia-naïve subjects. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5225–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, S.E.; Goll, J.B.; Beigel, J.H. Erythema and Induration after Mpox (JYNNEOS) Vaccination Revisited. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, J.T.; Marks, P.; Goldstein, R.H.; Walensky, R.P. Intradermal Vaccination for Monkeypox - Benefits for Individual and Public Health. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. EMA’s Emergency Task Force advises on intradermal use of Imvanex / Jynneos against monkeypox. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/emas-emergency-task-force-advises-intradermal-use-imvanex-jynneos-against-monkeypox (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Food and Drug Administration. Review Memorandum for the emergency use authorization (EUA) of JYNNEOS. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/160785/download (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Weidenthaler, H.; Vidojkovic, S.; Martin, B.K.; De Moerlooze, L. Real-world safety data for MVA-BN: Increased frequency of syncope following intradermal administration for immunization against mpox disease. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, S.E.; Lerner, A.; Tomashek, K. Safety and Immunogenicity of Fractional Doses of Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Global Congress in Barcelona, Spain. Saturday, April 27, 2024. (Congress communication).

- Dalton, A.F.; Diallo, A.O.; Chard, A.N.; Moulia, D.L.; Deputy, N.P.; Fothergill, A.; Kracalik, I.; Wegner, C.W.; Markus, T.M.; Pathela, P.; Still, W.L.; Hawkins, S.; Mangla, A.T.; Ravi, N.; Licherdell, E.; Britton, A.; Lynfield, R.; Sutton, M.; Hansen, A.P.; Betancourt, G.S.; et al. CDC Multijurisdictional Mpox Case Control Study Group (2023). Estimated Effectiveness of JYNNEOS Vaccine in Preventing Mpox: A Multijurisdictional Case-Control Study - United States, August 19, 2022-March 31, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023, 72, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vairo, F.; Leone, S.; Mazzotta, V.; Piselli, P.; De Carli, G.; Lanini, S.; Maggi, F.; Nicastri, E.; Gagliardini, R.; Vita, S.; Siddu, A.; Rezza, G.; Barca, A.; Vaia, F.; Antinori, A.; Girardi, E. The possible effect of sociobehavioral factors and public health actions on the mpox epidemic slowdown. Int J Infect Dis 2023, 130, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Weekly Bulletin on Outbreak and Other Emergencies: Week 28: 8 - 14 July 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/378355 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Vakaniaki, E.H.; Kacita, C.; Kinganda-Lusamaki, E.; O'Toole, Á.; Wawina-Bokalanga, T.; Mukadi-Bamuleka, D.; Amuri-Aziza, A.; Malyamungu-Bubala, N.; Mweshi-Kumbana, F.; Mutimbwa-Mambo, L.; Belesi-Siangoli, F.; Mujula, Y.; Parker, E.; Muswamba-Kayembe, P.C.; Nundu, S.S.; Lushima, R.S.; Makangara-Cigolo, J.C.; Mulopo-Mukanya, N.; Pukuta-Simbu, E.; Akil-Bandali, P.; et al. Sustained human outbreak of a new MPXV clade I lineage in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nature medicine 2024, 30, 2791–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Kibungu, E.M.; Vakaniaki, E.H.; Kinganda-Lusamaki, E.; Kalonji-Mukendi, T.; Pukuta, E.; Hoff, N.A.; Bogoch, I.I.; Cevik, M.; Gonsalves, G.S.; Hensley, L.E.; Low, N.; Shaw, S.Y.; Schillberg, E.; Hunter, M.; Lunyanga, L.; Linsuke, S.; Madinga, J.; Peeters, M.; Cigolo, J.M.; Ahuka-Mundeke, S.; et al. Clade I-Associated Mpox Cases Associated with Sexual Contact, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerging infectious diseases 2024, 30, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, M. Growing mpox outbreak prompts WHO to declare global health emergency. Nature 2024, 632, 718–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. Circolare del Ministero della Salute n. 35365 - Indicazioni ad interim sulla strategia vaccinale contro il vaiolo delle scimmie (MPX). Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2022&codLeg=88498&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Istituto Superiore Di Sanita’. EpiCentro sul vaiolo. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/vaiolo/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Ministero della Salute. Aggiornamento sulla modalità di somministrazione del vaccino JYNNEOS (MVA-BN). Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2022&codLeg=88627&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Mazzotta, V.; Lepri, A.C.; Matusali, G.; Cimini, E.; Piselli, P.; Aguglia, C.; Lanini, S.; Colavita, F.; Notari, S.; Oliva, A.; Meschi, S.; Casetti, R.; Mondillo, V.; Vergori, A.; Bettini, A.; Grassi, G.; Pinnetti, C.; Lapa, D.; Tartaglia, E.; Gallì, P.; et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara pre-exposure vaccination against mpox according to previous smallpox vaccine exposure and HIV infection: Prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 68, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry - Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/73679/download (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Colavita, F.; Mazzotta, V.; Rozera, G.; Abbate, I.; Carletti, F.; Pinnetti, C.; Matusali, G.; Meschi, S.; Mondi, A.; Lapa, D.; Vita, S.; Minosse, C.; Aguglia, C.; Gagliardini, R.; Specchiarello, E.; Bettini, A.; Nicastri, E.; Girardi, E.; Vaia, F.; Antinori, A.; et al. Kinetics of viral DNA in body fluids and antibody response in patients with acute Monkeypox virus infection. iScience 2023, 26, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO publishes public health advice on preventing and addressing stigma and discrimination related to mpox. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/11-12-2022-who-publishes-public-health-advice-on-preventing-and-addressing-stigma-and-discrimination-related-to-mpox (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox Vaccine Recommendations. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/vaccines/vaccine-recommendations.html (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Allan-Blitz, L.T.; Klausner, J.D. Prevalence of mpox immunity among the core group and its potential to prevent future large-scale outbreaks. The Lancet. Microbe Advance online publication. 2024, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guagliardo, S.A.J.; Kracalik, I.; Carter, R.J.; Braden, C.; Free, R.; Hamal, M.; Tuttle, A.; McCollum, A.M.; Rao, A.K. Monkeypox Virus Infections After 2 Preexposure Doses of JYNNEOS Vaccine - United States, May 2022-May 2024. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2024, 73, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, G.; Blümel, J.; Burger, R.; Drosten, C.; Gröner, A.; Gürtler, L.; Heiden, M.; Hildebrandt, M.; Jansen, B.; Montag-Lessing, T.; Offergeld, R.; Seitz, R.; Schlenkrich, U.; Schottstedt, V.; Strobel, J.; Willkommen, H.; von König, C.H. Orthopox Viruses: Infections in Humans. Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy 2010, 37, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Chong, T.M.; McClurkan, C.L.; Huang, J.; Story, B.T.; Koelle, D.M. Diversity in the acute CD8 T cell response to vaccinia virus in humans. Journal of immunology 2005, 175, 7550–7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matusali, G.; Petruccioli, E.; Cimini, E.; Colavita, F.; Bettini, A.; Tartaglia, E.; Sbarra, S.; Meschi, S.; Lapa, D.; Francalancia, M.; Bordi, L.; Mazzotta, V.; Coen, S.; Mizzoni, K.; Beccacece, A.; Nicastri, E.; Pierelli, L.; Antinori, A.; Girardi, E.; Vaia, F.; et al. Evaluation of Cross-Immunity to the Mpox Virus Due to Historic Smallpox Vaccination. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, H.; Bloom, N.; Cai, G.Y.; Clark, J.J.; Tarke, A.; Bermúdez-González, M.C.; Altman, D.R.; Lugo, L.A.; Lobo, F.P.; Marquez, S.; Chen, J.Q.; Ren, W.; Qin, L.; Yates, J.L.; Hunt, D.T.; Lee, W.T.; Crotty, S.; Krammer, F.; Grifoni, A.; et al.; PVI Study Group Mpox vaccine and infection-driven human immune signatures: An immunological analysis of an observational study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2023, 23, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandell, J.; Silva Monteiro, V.; Pischel, L.; Fang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Lawres, L.; Conde, L.; Meira de Asis, G.; Maciel, G.; Zaleski, A.; Lira, G.S.; Higa, L.M.; Breban, M.I.; Vogels, C.B.F.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Aoun-Barakat, L.; Grifoni, A.; Sette, A.; Castineiras, T.M.; Chen, S.; Yildirim, I.; Vale, A.M.; Omer, S.B.; Lucas, C. The impact of antigenic distance on Orthopoxvirus Vaccination and Mpox Infection for cross-protective immunity. medRxiv 2024, 2024.01.31.24302065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa. Regional Mpox Bulletin: 11 August 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/378456 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).