Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Insects

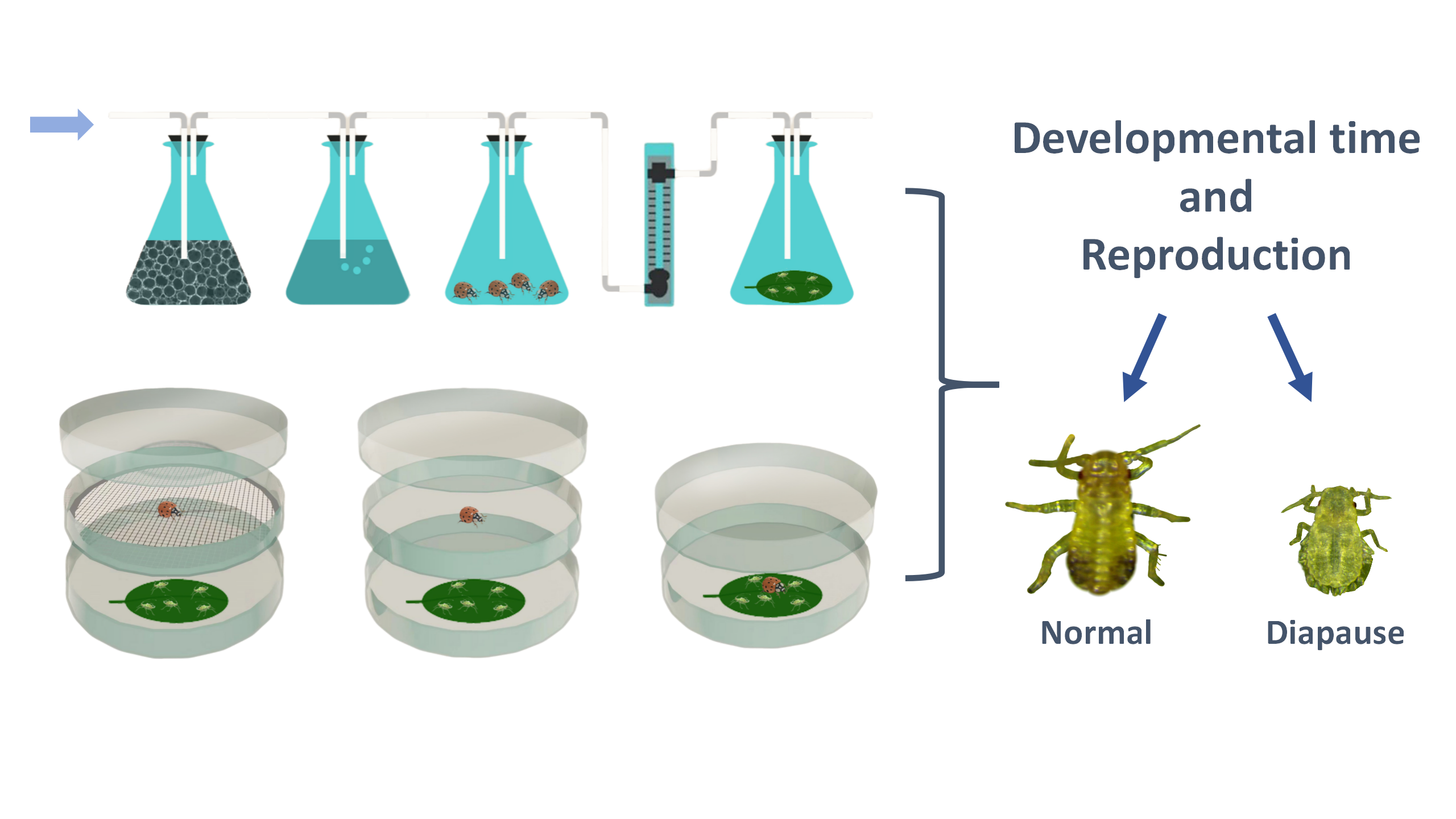

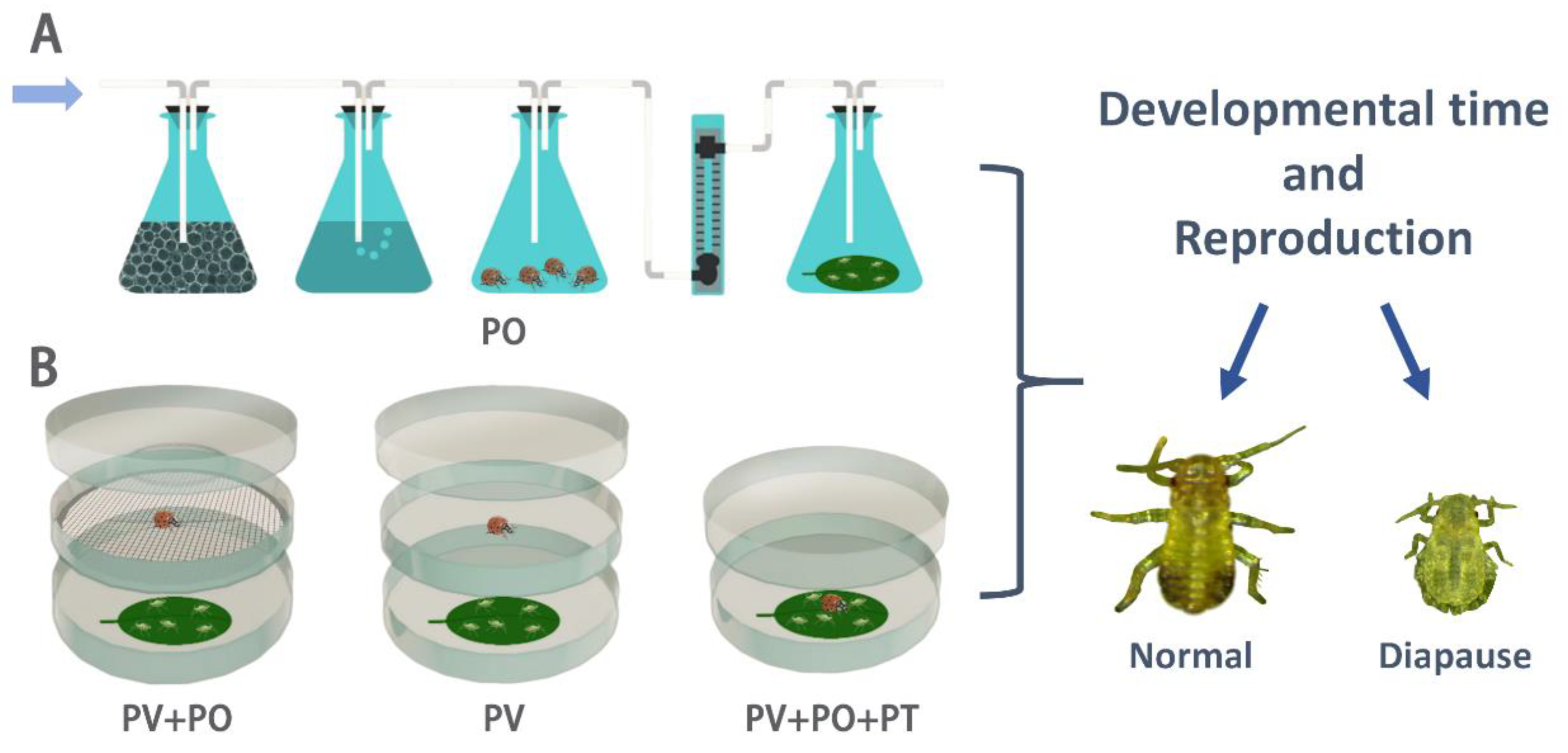

2.2. The Effect of H. axyridis Risk on Development and Reproduction of P. koelreuteriae

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of Different Predation Risk on the Development of Aphids

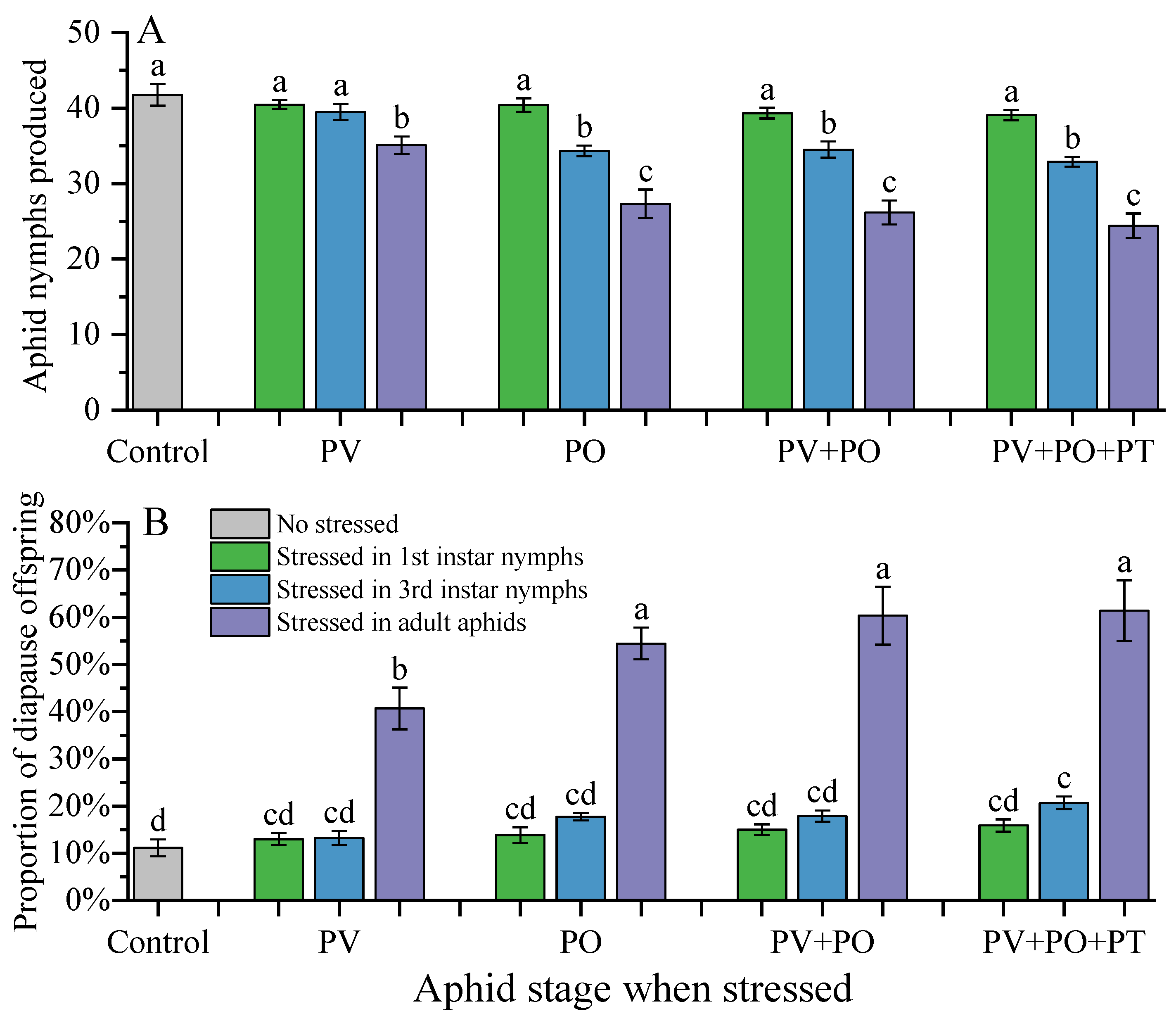

3.2. The Effects of Different Predation Risk on the Reproduction of Aphids

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orrock, J.L.; Grabowski, J.H.; Pantel, J.H.; Peacor, S.D.; Peckarsky, B.L.; Sih, A.; Werner, E.E. Consumptive and nonconsumptive effects of predators on metacommunities of competing prey. Ecology 2008, 89, 2426–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, E.G.; Johnson, C.N. Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation. Ecology Letters 2009, 12, 982–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawlena, D.; Schmitz, O.J. Herbivore physiological response to predation risk and implications for ecosystem nutrient dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 15503–15507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culshaw-Maurer, M.; Sih, A.; Rosenheim, J.A. Bugs scaring bugs: enemy-risk effects in biological control systems. Ecology Letters 2020, 23, 1693–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacor, S.D.; Peckarsky, B.L.; Trussell, G.C.; Vonesh, J.R. Costs of predator-induced phenotypic plasticity: A graphical model for predicting the contribution of nonconsumptive and consumptive effects of predators on prey. Oecologia 2013, 171, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisser, E.L.; Bolnick, D.I.; Benard, M.F. Scared to death? The effects of intimidation and consumption in predator–prey interactions. Ecology 2005, 86, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, K. Visually guided search behavior during walking in insects with different habitat utilization strategies. J Insect Behav 2019, 32, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuzzo, F.S.; de, C. Bovolato, A.L.; Pereira, R.T.; Valença-Silva, G.; Barcellos, L.J.G.; Barreto, R.E. Innate response based on visual cues of sympatric and allopatric predators in Nile tilapia. Behavioural Processes 2019, 164, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, T.C. Antipredator defenses in birds and mammals. The Auk 2006, 123, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, N.E.; Blumstein, D.T. Multisensory perception in uncertain environments. Behavioral Ecology 2012, 23, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettena, A.M.; Munoz, N.; Blumstein, D.T. Prey responses to predator’s sounds: A review and empirical study. Ethology 2014, 120, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, S.L.; Thaler, J.S. Prey perception of predation risk: Volatile chemical cues mediate non-consumptive effects of a predator on a herbivorous insect. Oecologia 2014, 176, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.E.; Magnavacca, G. Predator inspection behaviour in a characin fish: an interaction between chemical and visual information? Ethology 2003, 109, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.E.; Peacor, S.D. A review of trait-mediated indirect interactions in ecological communities. Ecology 2003, 84, 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, N.; Lynch, B.; Rochette, R. Trade-off between mating and predation risk in the marine snail, littorina plena. Invertebrate Biology 2007, 126, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M.C. The growth–predation risk trade-off under a growing gape-limited predation threat. Ecology 2007, 88, 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Ge, F. Effects of predatory stress imposed by Harnonia axyridis on the development and fecundity of Drosophila melanogaster. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2010, 29, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforsch, C.; Tollrian, R. Inducible defenses in multipredator environments: Cyclomorphosis in Daphnia cucullata. Ecology 2004, 85, 2302–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Crossley, M.S.; Fu, Z.; Meier, A.R.; Crowder, D.W.; Snyder, W.E. Exposure to predators, but not intraspecific competitors, heightens herbivore susceptibility to entomopathogens. Biological Control 2020, 151, 104403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepielski, A.M.; Fallon, E.; Boersma, K. Predator olfactory cues generate a foraging–predation trade-off through prey apprehension. R. Soc. open sci. 2016, 3, 150537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X.; Zhong, T.S. Economic Insect Fauna of China, Fasc. 25. Homoptera: Aphidomorpha. 25th ed.; Science Press, Beijing, 1983.

- Li, D.X.; Ren, J.; Du, D.; Wang, Q.C. Life tables of the laboratory population of Periphyllus koelreuteriae (Hemiptera: Chaitophoridae) at different temperatures. Acta Entomolohica Sinica 2015, 58, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.C.; Li, Z.H.; Liu, G.L.; Ye, B.H.; Dong, J.X.; Ren, P. Studies on the bionomics of Periphyllus koelreuteriae and its control. Journal of Shandong Agricultural University 1990, 21, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, P.; Zhou, L.Q.; Xu, Z. Biological characteristics and control of Periphyllus koelreuteriae (Takahashi) in Shanghai district. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University 2004, 22, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, J.P. Coccinellids in biological control. In Ecology and Behaviour of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae); Wiley, 2012; pp. 488–519 ISBN 978-1-4051-8422-9.

- Hermann, S.L.; Bird, S.A.; Ellis, D.R.; Landis, D.A. Predation risk differentially affects aphid morphotypes: Impacts on prey behavior, fecundity and transgenerational dispersal morphology. Oecologia 2021, 197, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansman, J.T.; Nersten, C.E.; Hermann, S.L. Smelling danger: lady beetle odors affect aphid population abundance and feeding, but not movement between plants. Basic and Applied Ecology 2023, 71, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoks, R. Food Stress and predator-induced stress shape developmental performance in a damselfly. Oecologia 2001, 127, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotthard, K. Increased risk of predation as a cost of high growth rate: an experimental test in a butterfly. Journal of Animal Ecology 2000, 69, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.M.; McCauley, S.J. Predation risk increases immune response in a larval dragonfly (Leucorrhinia intacta). Ecology 2016, 97, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenke, R.A.; Lazzaro, B.P.; Wolfner, M.F. Reproduction–immunity trade-offs in insects. Annual Review of Entomology 2016, 61, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.-Q. Level-dependent effects of predation stress on prey development, lifespan and reproduction in mites. Biogerontology 2022, 23, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, T.; Feng, J.; Jiang, T. Effects of predation risks of bats on the growth, development, reproduction, and hormone levels of Spodoptera litura. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1126253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Cui, X.; Tang, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, J. Predation risk effects of lady beetle Menochilus sexmaculatus (Fabricius) on the melon aphid, aphis Gossypii glover. Insects 2024, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wen, J.; Geng, X.; Xiao, L.; Zou, Y.; Shan, Z.; Lu, X.; Fu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Cao, F. The impact of predation risks on the development and fecundity of Bactrocera dorsalis Hendel. Insects 2024, 15, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.-Q. Predation stress experienced as immature mites extends their lifespan. Biogerontology 2023, 24, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Atlihan, R.; Chai, R.; Dong, Y.; Luo, C.; Hu, Z. Assessment of non-consumptive predation risk of Coccinella septempunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on the population growth of Sitobion miscanthi (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Insects 2022, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempraj, V.; Park, S.J.; Taylor, P.W. Forewarned is forearmed: Queensland fruit flies detect olfactory cues from predators and respond with predator-specific behaviour. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersch-Becker, M.F.; Thaler, J.S. Plant resistance reduces the strength of consumptive and non-consumptive effects of predators on aphids. Journal of Animal Ecology 2015, 84, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariel, J.; Plénet, S.; Luquet, É. Transgenerational plasticity in the context of predator-prey interactions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 548660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A.; Yoshida, T.; Choh, Y. Maternal exposure to predation risk increases winged morph and antipredator dispersal of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Appl Entomol Zool 2022, 57, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberty, A.F.; Denno, R.F. Trade-off in investment between dispersal and ingestion capability in phytophagous insects and its ecological implications. Oecologia 2006, 148, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernays, E.A. Feeding by lepidopteran larvae is dangerous. Ecological Entomology 1997, 22, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duempelmann, L.; Skribbe, M.; Bühler, M. Small RNAs in the transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic information. Trends in Genetics 2020, 36, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouzitallab, P.; Baruah, K.; Vanrompay, D.; Bossier, P. Can epigenetics translate environmental cues into phenotypes? Science of The Total Environment 2019, 647, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, B. The role of olfaction in aphid host location. Physiological Entomology 2012, 37, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkovic, V.; Feng, Y.; Olsson, U.; Pettersson, J. Ladybird footprints induce aphid avoidance behavior. Biological Control 2013, 65, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, T.W.; Godin, J.G.J. The visual ecology of predator-prey interactions. In: Barbosap, castellanosi (eds) ecology of predator-prey interactions. Oxford University Press: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, A.F.G.; McKay, S. Aggregation in the sycamore aphid Drepanosiphum platanoides (Schr.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and its relevance to the regulation of population growth. The Journal of Animal Ecology 1970, 39, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartbauer, M. Collective defense of Aphis Nerii and Uroleucon hypochoeridis (Homoptera, Aphididae) against natural enemies. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ari, M.; Inbar, M. Aphids link different sensory modalities to accurately interpret ambiguous cues. Behavioral Ecology 2014, 25, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gish, M. Aphids detect approaching predators using plant-borne vibrations and visual cues. J Pest Sci 2021, 94, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, T.F.; Spaethe, J. Measurements of eye size and acuity in aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Entomol Gen 2009, 32, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.L.; Steury, T.D. Perception of predation risk: the foundation of nonlethal predator-prey interactions. In: Ecology Of Predator-Prey Interactions; Barbosa, P., Castellanos, I., Eds.; Oxford University PressNew York, NY, 2005; pp. 166–188 ISBN 978-0-19-517120-4.

- Herberholz, J.; Marquart, G.D. Decision making and behavioral choice during predator avoidance. Front. Neurosci. 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schadegg, A.C.; Herberholz, J. Satiation level affects anti-predatory decisions in foraging juvenile crayfish. J Comp Physiol A 2017, 203, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooijman, S.A.L.M. Dynamic Energy Budget Theory for Metabolic Organisation; 3rd ed.; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, 2010; ISBN 978-0-521-13191-9.

- Tamai, K.; Choh, Y. Previous exposures to cues from conspecifics and ladybird beetles prime antipredator responses in pea aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Appl Entomol Zool 2019, 54, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.E.; Ferrari, M.C.O.; Malka, P.H.; Oligny, M.-A.; Romano, M.; Chivers, D.P. Growth rate and retention of learned predator cues by juvenile rainbow trout: faster-growing fish forget sooner. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2011, 65, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.C.O.; Vrtělová, J.; Brown, G.E.; Chivers, D.P. Understanding the role of uncertainty on learning and retention of predator information. Anim Cogn 2012, 15, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predator risk | N1 | N2 | N3 | N4 | Total nymph stage | Adult longevity |

| CK | 3.14 ± 0.13 c | 2.05 ± 0.09 c | 1.82 ± 0.09 bc | 1.85 ± 0.09 a | 8.84 ± 0.20 c | 9.72 ± 0.15 a |

| PV | 3.20 ± 0.11 c | 2.09 ± 0.08 c | 1.87 ± 0.09 bc | 1.86 ± 0.09 a | 9.03 ± 0.24 c | 9.34 ± 0.21 a |

| PO | 3.64 ± 0.15 b | 2.39 ± 0.09 b | 2.11 ± 0.07 ab | 1.95 ± 0.09 a | 10.09 ± 0.23 b | 9.95 ± 0.34 a |

| PV+PO | 3.65 ± 0.12 b | 2.43 ± 0.10 ab | 2.14 ± 0.08 ab | 2.02 ± 0.11 a | 10.25 ± 0.20 b | 9.33 ± 0.37 a |

| PV+PO+PT | 4.66 ± 0.16 a | 2.66 ± 0.09 a | 2.24 ± 0.08 a | 2.09 ± 0.12 a | 11.65 ± 0.26 a | 8.86 ± 0.35 a |

| Predator risk | N3 | N4 | Adult longevity |

| CK | 1.89 ± 0.10 c | 1.83 ± 0.11 a | 9.75 ± 0.18 a |

| PV | 2.00 ± 0.09 bc | 1.86 ± 0.11 a | 9.03 ± 0.20 a |

| PO | 2.31 ± 0.08 ab | 1.92 ± 0.07 a | 9.08 ± 0.27 a |

| PV+PO | 2.33 ± 0.11 ab | 1.94 ± 0.09 a | 9.47 ± 0.31 a |

| PV+PO+PT | 2.56 ± 0.11 a | 1.94 ± 0.08 a | 9.14 ± 0.28 a |

| Predator risk | Adult longevity |

| CK | 9.75 ± 0.18 a |

| PV | 8.78 ± 0.31 b |

| PO | 8.25 ± 0.22 bc |

| PV+PO | 7.61 ± 0.23 cd |

| PV+PO+PT | 7.22 ± 0.29 d |

| Trait | source | df | Mean-Square Value (MS) | F-Values | p |

| Fecundity | Stressed aphid stage | 2 | 1625.215 | 104.908 | <0.001 |

| Stress type | 3 | 259.581 | 16.756 | <0.001 | |

| Stressed aphid stage× Stress type | 6 | 55.928 | 3.610 | 0.002 | |

| Error | 132 | 15.492 | |||

| Proportion of diapause offspring | Stressed aphid stage | 2 | 2.367 | 191.616 | <0.001 |

| Stress type | 3 | 0.077 | 6.238 | 0.001 | |

| Stressed aphid stage× Stress type | 6 | 0.023 | 1.845 | 0.095 | |

| Error | 132 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).