Submitted:

24 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| OS | Overall survival |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| EFS | Event free survival |

| IFI | Invasive fungal infection |

References

- Seth R, Singh A. Leukemias in Children. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82(9):817–24. [CrossRef]

- Hiroto Inaba, Mel Greaves CGM. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Lancet. 2014;381(9881):1–27. [CrossRef]

- Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1541–52. [CrossRef]

- Hough R, Rowntree C, Goulden N, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of a paediatric protocol in teenagers and young adults with Philadelphia chromosome negative acute lymphoblastic leukaemia : results from UKALL 2003. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:439–51. [CrossRef]

- Stary J, Zimmermann M, Campbell M, et al. Intensive Chemotherapy for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia : Results of the Randomized Intercontinental Trial ALL IC-BFM 2002. Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019;32(3):172–84. [CrossRef]

- Toft N, Birgens H, Abrahamsson J, et al.Toxicity profile and treatment delays in NOPHO ALL2008 — comparing adults and children with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 2015;96:160–9. [CrossRef]

- Pui C-H, Pei D, Raimondi SC, et al. Clinical Impact of Minimal Residual Disease in Children with Different Subtypes of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated with Response-Adapted Therapy. Leukemia. 2017;31(2):333–9. [CrossRef]

- Veerman AJ, Kamps WA, Berg H Van Den, et al. Dexamethasone-based therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia : results of the prospective Dutch Childhood Oncology Group ( DCOG ) protocol ALL-9 ( 1997 – 2004 ). Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(10):957–66. [CrossRef]

- Place AE, Stevenson KE, Vrooman LM, et al. Intravenous pegylated asparaginase versus intramuscular native Escherichia coli L-asparaginase in newly diagnosed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia ( DFCI 05-001 ): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;2045(15):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Freyer DR, Devidas M, La M, et al. Postrelapse survival in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is independent of initial treatment intensity : a report from the Children ’ s Oncology Group. Blood J. 2018;117(11):3010–6. [CrossRef]

- Hao TK, Hiep PN. Causes of Death in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia at Hue Central Hospital for. Glob Pediatr Heal. 2020;7:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Jeha S, Pei D, Choi J, et al. Improved CNS control of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation: St Jude Total Therapy Study 16. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(35):3377–91. [CrossRef]

- Surapolchai P, Anurathapan U, Sermcheep A, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Modified St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Total Therapy XIIIB and XV Protocols for Thai Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin Lymphoma, Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(8):497–505. [CrossRef]

- Horibe K, Yumura-Yagi K, Kudoh T, et al. Long-term results of the risk-adapted treatment for childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Report from the Japan association of childhood leukemia study ALL-97 trial. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39(2):81–9. [CrossRef]

- Kiem Hao T, Nhu Hiep P, Kim Hoa NT, et al. Causes of Death in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia at Hue Central Hospital for 10 Years (2008-2018). Glob Pediatr Heal. 2020;7:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hossain MJ, Xie L, McCahan SM. Characterization of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survival Patterns by Age at Diagnosis. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;2014. [CrossRef]

- Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved Survival for Children and Adolescents With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Between 1990 and 2005 : A Report From the Children ’ s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;10:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Pui C, Pei D, Raimondi SC, et al. Clinical Impact of Minimal Residual Disease in Children with Different Subtypes of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated with Response-Adapted Therapy. Leukemia. 2017;31(2):333–9. [CrossRef]

- Rheingold SR, Ji L, Xu X, et al. Prognostic factors for survival after relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): A Children’s Oncology Group (COG) study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):10008. [CrossRef]

- Maloney KW, Devidas M, Wang C, et al. Outcome in Children With Standard-Risk B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia : Results of Children ’ s Oncology Group Trial AALL0331. J Clin Oncol. 2019;38(6):602–12. [CrossRef]

- Binitha Rajeswari, Reghu K Sukumaran Nair, C S Guruprasad, et al. Infections during Induction Chemotherapy in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia – Profile and Outcomes : Experience from a Cancer Center in South India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2021;39(02):188–92. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa S, Kato M, Imamura T, et al. In-Hospital Management Might Reduce Induction Deaths in Pediatric Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Results From a Japanese Cohort. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;43(2):39–46. [CrossRef]

- Ruijters VJ, Oosterom N, Wolfs TFW, et al. Frequency and Determinants of Invasive Fungal Infections in Children With Solid and Hematologic Malignancies in a Nonallogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation Setting: A Narrative Review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41(5):345–54. [CrossRef]

- Rambaldi, B. , Russo D. PL. Letters to the Editor: Defining Invasive Fungal Infection Risk in Hematological Malignancies : A New Tool for Clinical Practice. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2017;9(1):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez H, Martinez LR. Relationship of environmental disturbances and the infectious potential of fungi. Microbiology. 2018;164:233–41. [CrossRef]

- Kanamori H, Rutala WA, Sickbert-bennett EE, et al. Review of Fungal Outbreaks and Infection Prevention in Healthcare Settings During Construction and Renovation. Helathcare Epidemiol. 2015;61:433–44. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki M, Kanda J, Hishizawa M, et al. Effect of laminar air flow and building construction on aspergillosis in acute leukemia patients : a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(38):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Tuong PN, Kiem Hao T, Kim Hoa NT. Relapsed Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Single-Institution Experience. Cureus. 2020;12(7):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Abdelmabood S, Elsayed A, Boujettif F, et al. Treatment outcomes of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a middle-income developing country : high mortalities, early relapses, and poor survival J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kelly ME, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Treatment of Relapsed Precursor-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia with Intensive Chemotherapy: POG (Pediatric Oncology Group) Study 9411 (SIMAL 9). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(7):509–13. [CrossRef]

| Number of patients (%) | 5-year EFS (%) | 5-year OS (%) | Number of relapsed patients | Percentage of relapsed patients | 5-year OS of relapsed patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in relation to overall number at the diagnosis (%) | ||||||

| Patients | 302 (100%) | 80% | 83% | 41 | 14% | 22% |

| GENDER | ||||||

| Male | 178 (59%) | 77% | 81% | 30 | 17% | 23% |

| Female | 124 (41%) | 85% | 86% | 11 | 9% | 18% |

| AGE GROUPS | ||||||

| Infants | 8 (3%) | 50% | 50% | 4 | 50% | 0% |

| 1 - 4 y. | 165 (55%) | 85% | 88% | 16 | 10% | 31% |

| 5 - 9 y. | 66 (22%) | 77% | 83% | 11 | 17% | 36% |

| 10 - 17 y. | 63 (21%) | 73% | 73% | 10 | 16% | 0% |

| IMMUNOPHENOTYPE | ||||||

| common | 181 (60%) | 82% | 86% | 22 | 12% | 27% |

| pre B | 63 (21%) | 73% | 78% | 12 | 19% | 25% |

| pro B | 5 (1%) | 60% | 60% | 2 | 40% | 0% |

| T | 53 (18%) | 83% | 83% | 5 | 10% | 0% |

| RISK GROUPS | ||||||

| SR | 69 (23%) | 87% | 96% | 4 | 6% | 25% |

| IR | 154 (51%) | 85% | 89% | 16 | 10% | 44% |

| HR | 79 (26%) | 53% | 63% | 21 | 27% | 5% |

| Number | Percentage | Survival | 5-year OS (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Relapsed patients |

41 | 14% (in relation to entire cohort) | 9 | 22% | |

| TIME OF RELAPSE | |||||

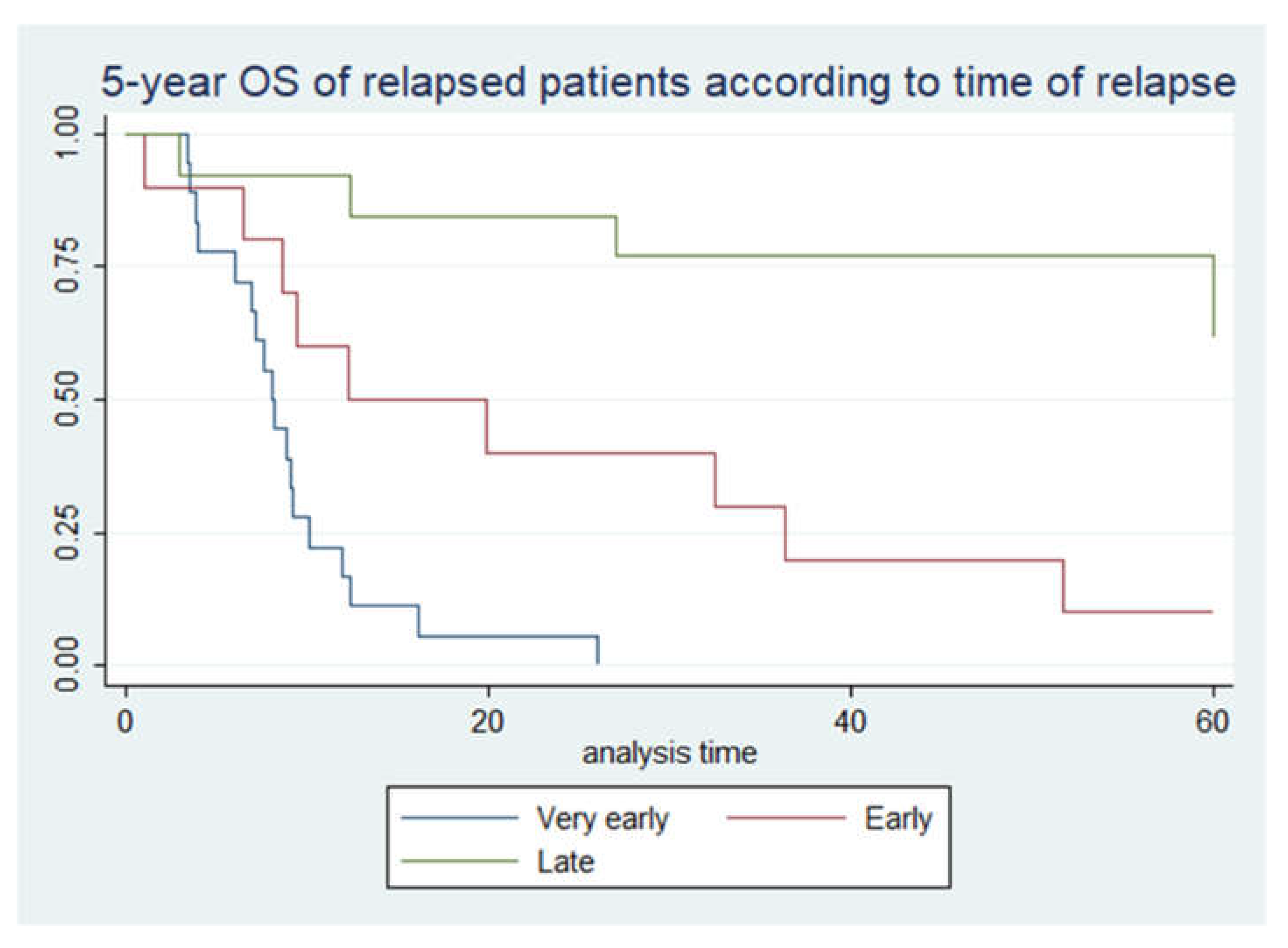

| Very early | 18 | 44% | 0 | 0% | |

| Early | 10 | 24% | 1 | 10% | |

| Late | 13 | 32% | 8 | 62% | |

| SITE OF RELAPSE | |||||

| Bone marrow | 27 | 66% | 6 | 22% | |

| Isolated CNS | 1 | 2% | 1 | 100% | |

| Bone marrow + CNS | 13 | 32% | 2 | 15% | |

| TREATMENT | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 22 | 54% | 3 | 14% | |

| Chemotherapy + HSCT | 19 | 46% | 6 | 32% | |

| Analysis | Univariate HR | p | Multivariate HR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INITIAL DIAGNOSIS | ||||

| Relapse | ||||

| No | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| Yes | 15,78 (8,76-28,43) | <0,05 | 13,24 (6,92-25,37) | <0,05 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| Female | 0,66 (0,37-1,2) | 0,17 | 1,02 (0,54-1,91) | 0,96 |

| Age groups | ||||

| Infants | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| 1y-4y | 0,19 (0,06-0,55) | 0,002 | 1,07 (0,33-3,54) | 0,9 |

| 5y-9y | 0,24 (0,08-0,77) | 0,016 | 0,66 (0,19-2,3) | 0,52 |

| 10y-17y | 0,43 (0,14-1,28) | 0,128 | 1,03 (0,33-3,27) | 0,95 |

| Immunophenotype | ||||

| common | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| pre B | 1,72 (0,89-3,31) | 0,104 | 1,41 (0,72-2,77) | 0,32 |

| pro B | 3,6 (0,85-15,22) | 0,082 | 1,48 (0,32-6,73) | 0,61 |

| T ALL | 1,3 (0,61-2,78) | 0,502 | 1,75 (0,77-3,98) | 0,18 |

| Risk group | ||||

| SR | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| IR | 2,51 (0.73-8.64) | 0,142 | 2,18 (0,61-7,75) | 0,23 |

| HR | 11,76 (3,59-38,5) | <0,05 | 6,85 (1,87-24,9) | <0,05 |

| Analysis | Univariate HR | p | Multivariate HR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFTER RELAPSE | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| male | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| female | 1,02 (0,47-2,2) | 0,95 | 1,06 (0,44-2,57) | 0,897 |

| Age groups | ||||

| infants | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| 1y-4y | 0,14 (0,04-0,5) | <0,05 | 0,36 (0,05-2,78) | 0,33 |

| 5y-9y | 0,14 (0,03-0,52) | <0,05 | 0,81 (0,14-4,69) | 0,81 |

| 10y-17y | 0,29 (0,08-1,03) | 0,055 | 0,72 (0,14-3,59) | 0,69 |

| Immunophenotype | ||||

| common | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| pre B | 1,96 (0,87-4,4) | 0,102 | 2,16 (0,66-7,1) | 0,21 |

| pro B | 23,56 (3,74-148,2) | <0,05 | 7,17 (0,76-67,76) | 0,086 |

| T ALL | 9,1 (2,77-29,9) | <0,05 | 2,87 (0,49-16,84) | 0,24 |

| Risk group | ||||

| Standard risk | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| Intermediate risk | 0,95 (0,26-3,5) | 0,94 | 3,08 (0,44-21,69) | 0,26 |

| High risk | 3,57 (1,04-12,27) | 0,043 | 14,18 (1,2-167,4) | 0,035 |

| Time of relapse | ||||

| very early | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| early | 0,1 (0,03-0,32) | <0,05 | 0,22 (0,03-1,55) | 0,129 |

| late | 0,02 (0,004-0,08) | <0,05 | 0,008 (0,001-0,06) | <0,05 |

| Site of relapse | ||||

| Bone marrow | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| Isolated CNS | / | / | / | / |

| Bone marrow + CNS | 1,05 (0,5-2,2) | 0,9 | 2,27 (0,6-8,4) | 0,22 |

| Chemo/HSCT | ||||

| Chemotherapy + HSCT | 1,00 | Reference | 1,00 | Reference |

| Chemotherapy | 1,01 (0,5-2,02) | 0,982 | 1,54 (0,64-3,74) | 0,34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).