Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Robustness is the ability of the system to withstand the initial disturbance; it is often quantified by the fraction of components that remain functional immediately after the shock [1].

- Resiliency (or recovery) is the ability to return to acceptable performance after the disturbance. It combines the depth of degradation with the speed and extent of restoration [2].

1.1. Existing Work on Cascading Failures

1.2. Objectives and Contributions of This Work

- 1.

- Concurrent cascade + self-healing model. We formulate two algorithms: one for link-breaking failure and one for distributed healing, that act within the same simulation step, controlled by a budget parameter and a triggering threshold .

- 2.

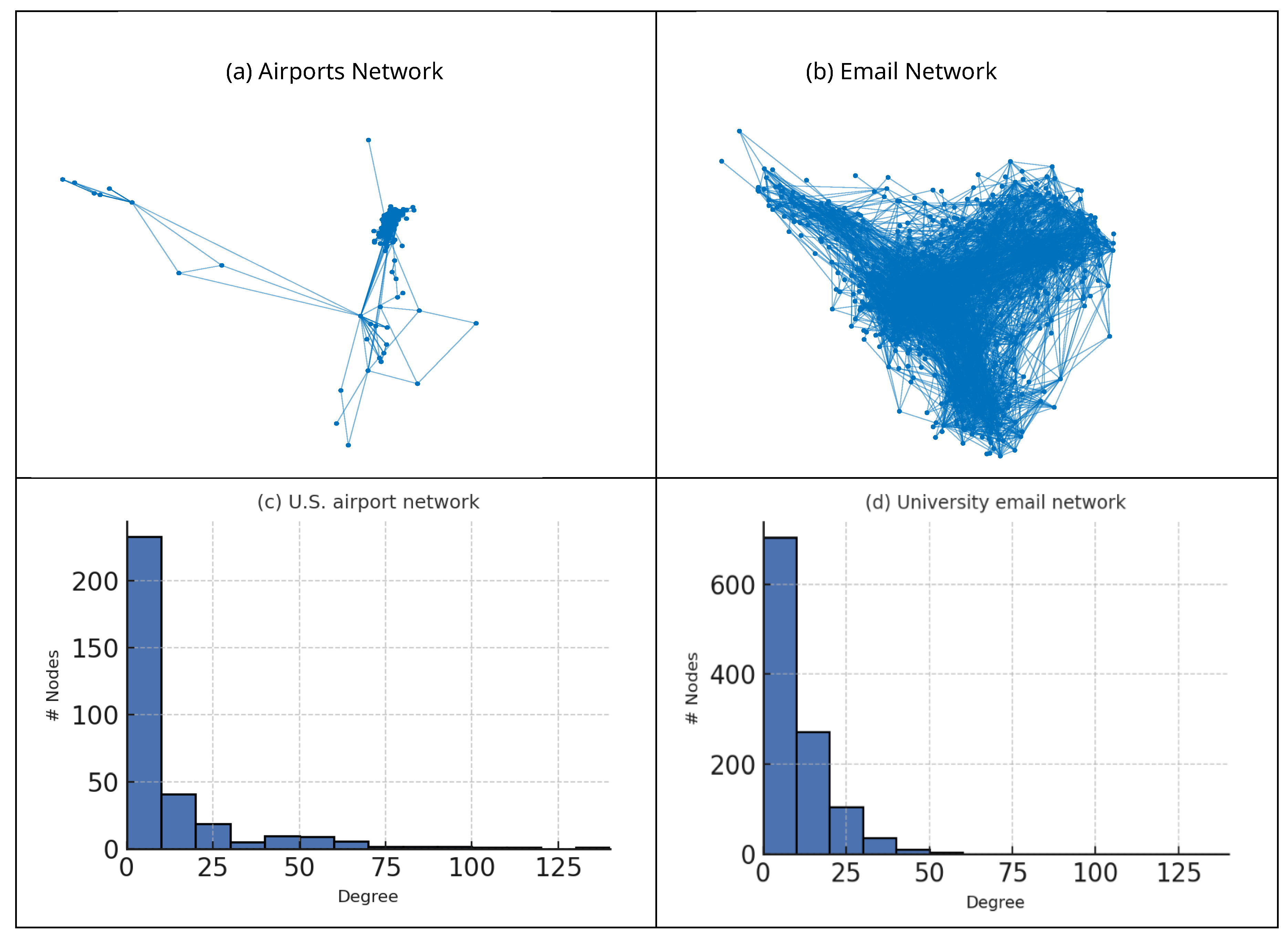

- Quantitative evaluation on real data. Using a U.S. airport network (332 nodes) [26] and a university e-mail network (1133 nodes) we measure robustness and two resiliency metrics: 90 % recovery time T90 and cumulative average damage.

- 3.

- Systematic exploration of parameter space. We vary the degree-loss threshold , the attack mode (random vs. targeted), the healing budget and the trigger time, producing a comprehensive map of robustness and resiliency responses.

- 4.

- First empirical correlation study. Scatter-plot analysis reveals that robustness and resiliency are only weakly correlated unless the trigger is early and the budget adequate; high robustness can coexist with slow or costly recovery and vice versa. We summarize the relationship with a simple multiplicative fit and discuss design implications.

1.3. Paper Organization

2. Description of Models and Methods

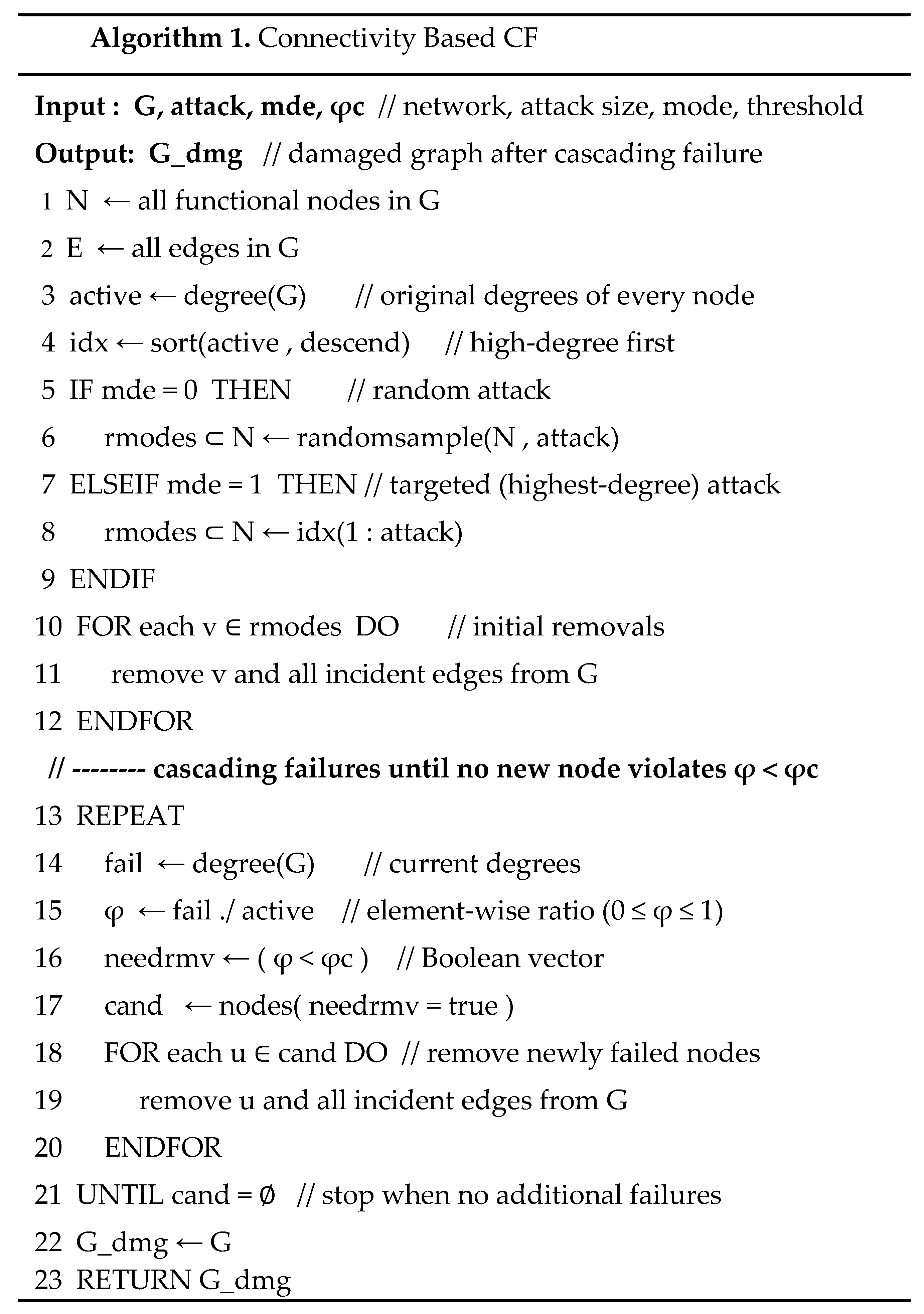

2.1. Connectivity – Based Failure and Healing

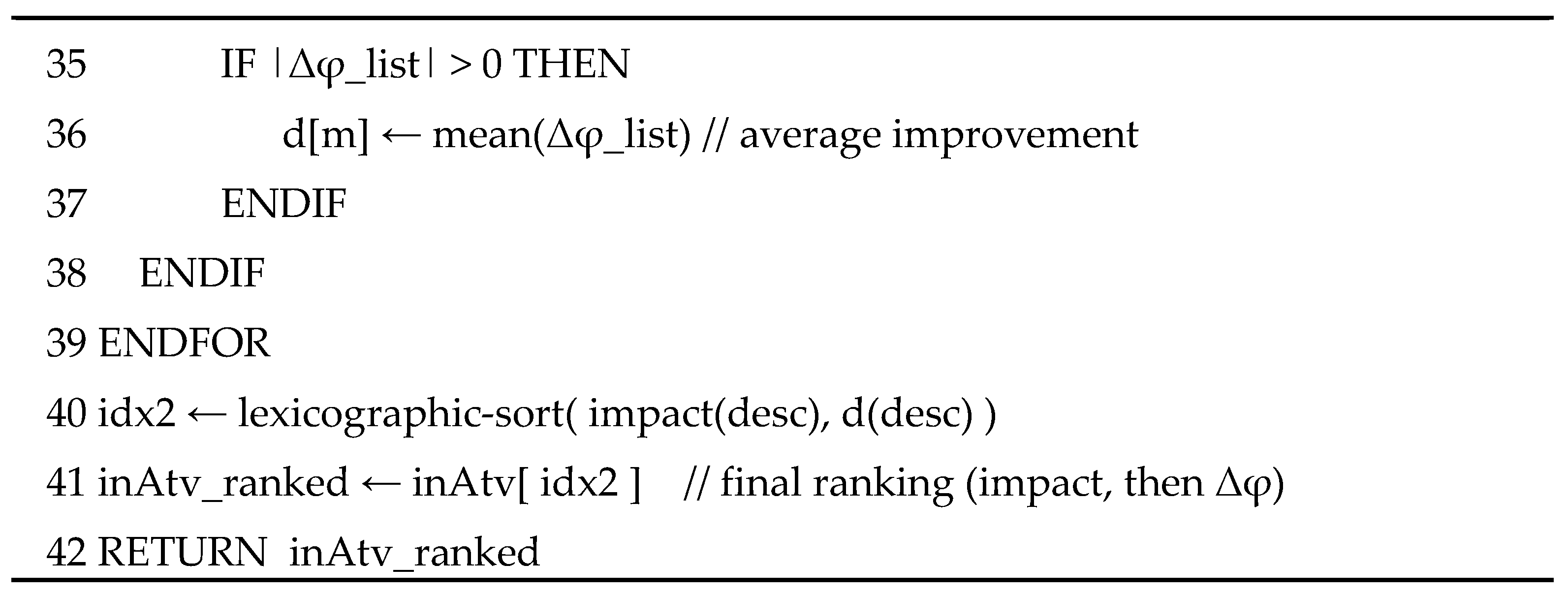

- Step 1 – Decision (Algorithm 2a).

- A primary impact: the number of active neighbors that would be saved if the node were reactivated (i.e., neighbors whose ratio would rise from <φc to ).

- A secondary impact: the average increase of those neighbors. Nodes are ranked first by primary impact and then, to break ties, by secondary impact.

- Step 2 – Implementation (Algorithm 2b).

2.2. Robustness and Resiliency Metrics

- 1.

- Average Damage over a predefined time window :

- 2.

- 90% Recovery time, .

2.3. Description of Data

3. Results and Discussion

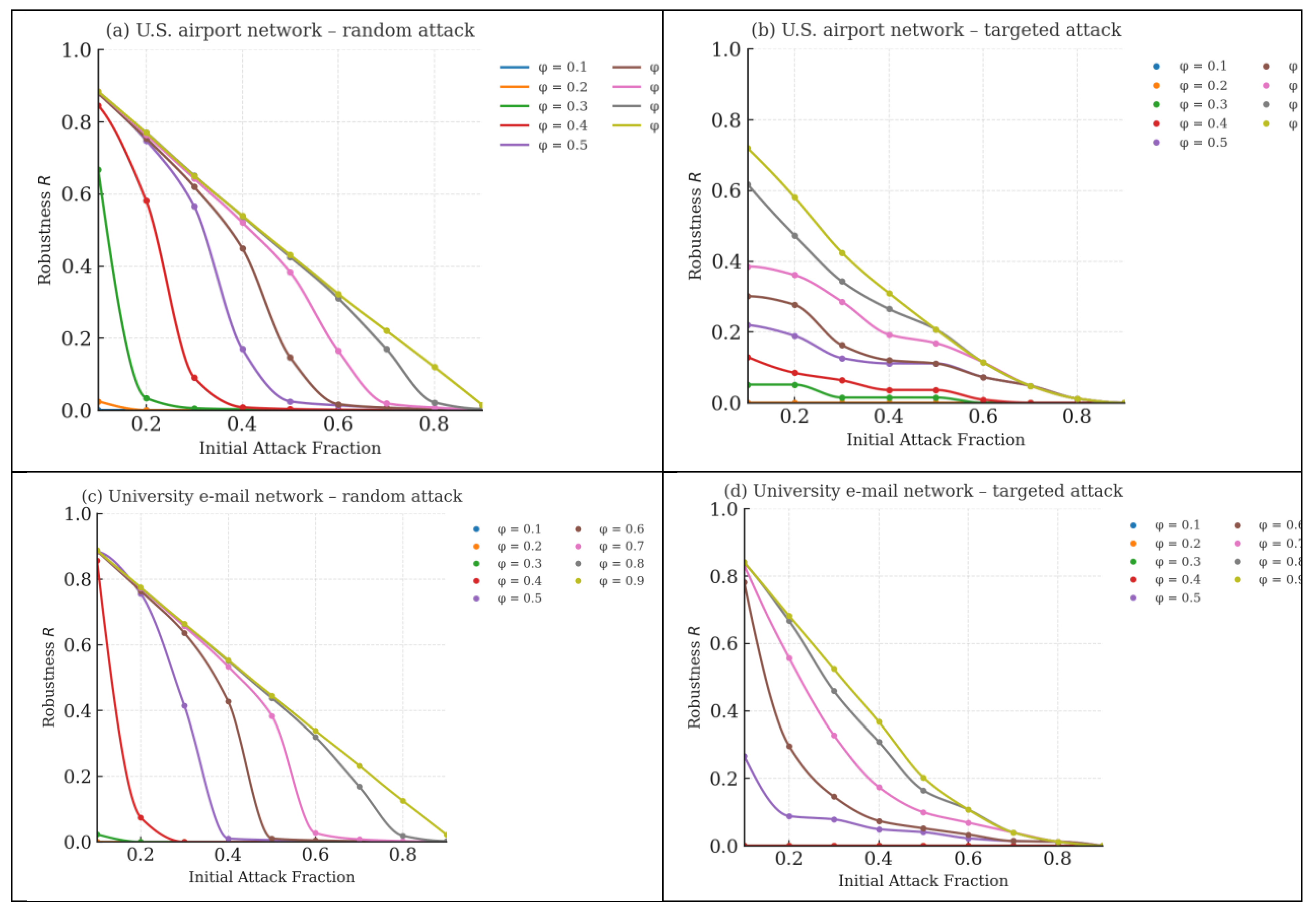

3.1. Robustness Patterns

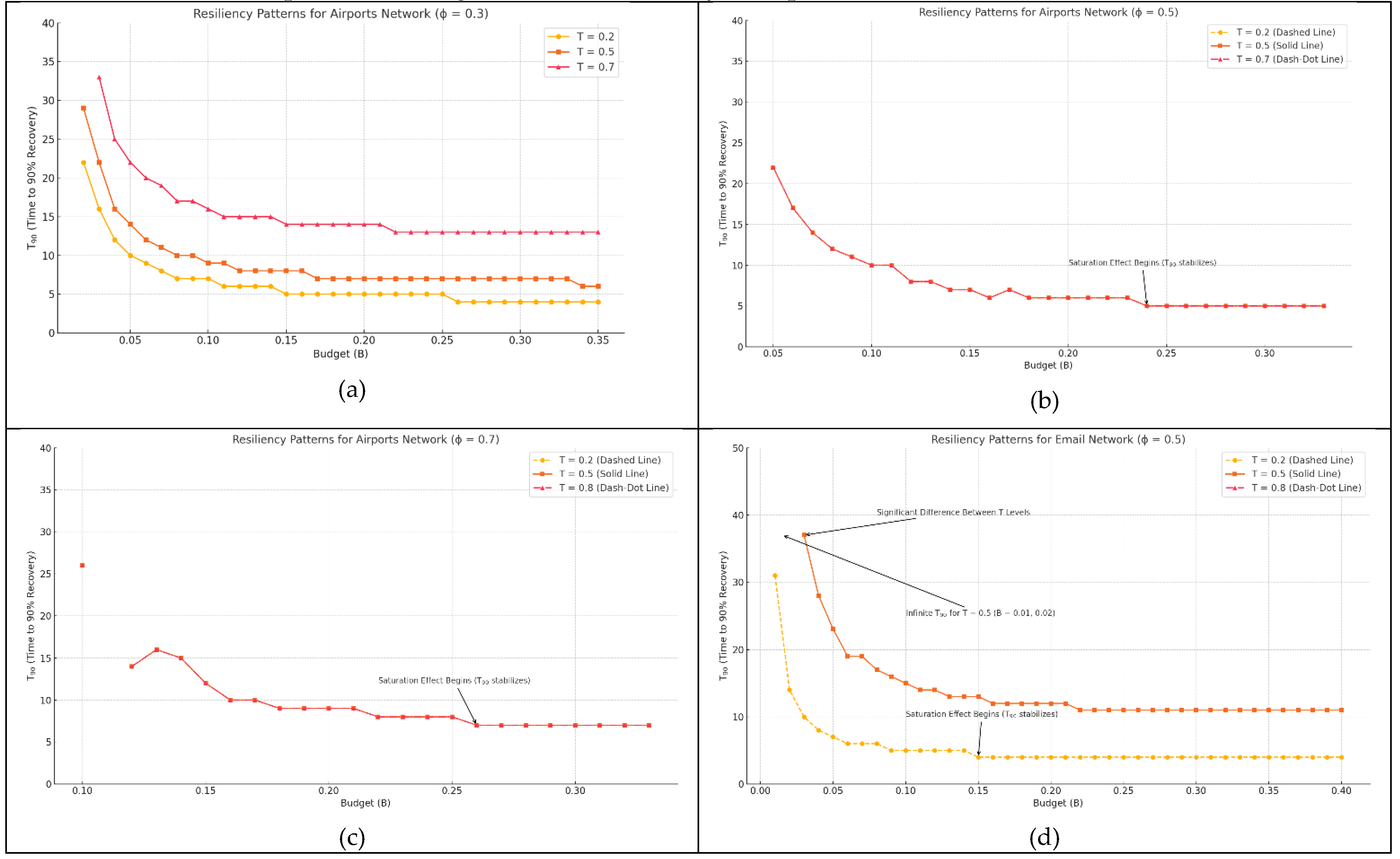

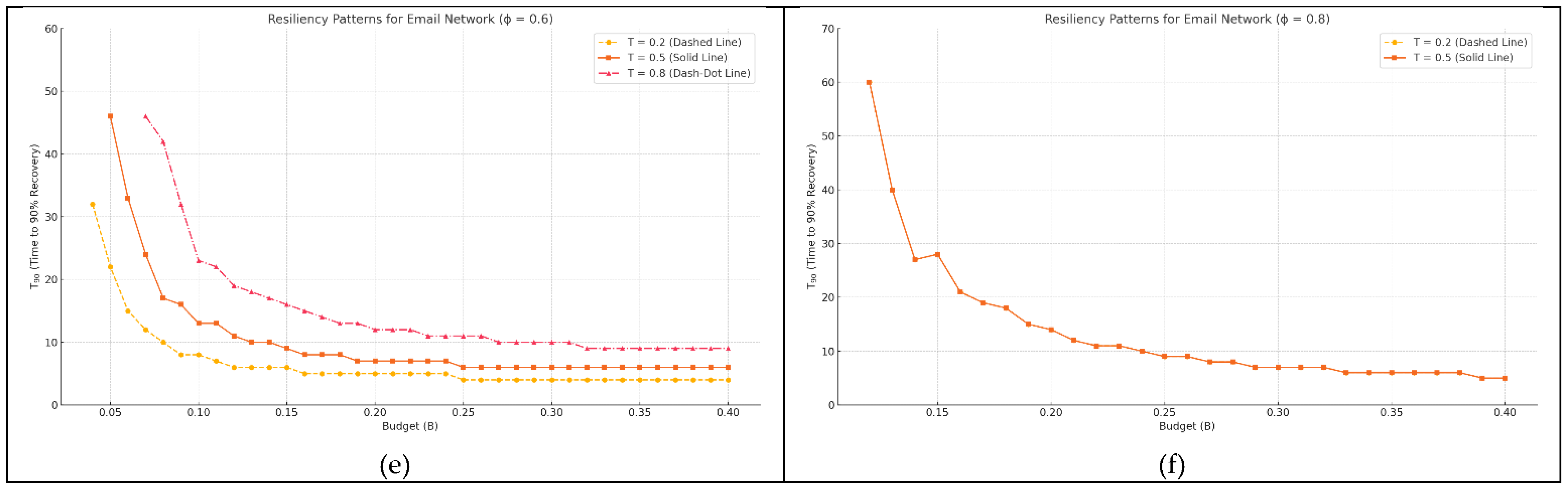

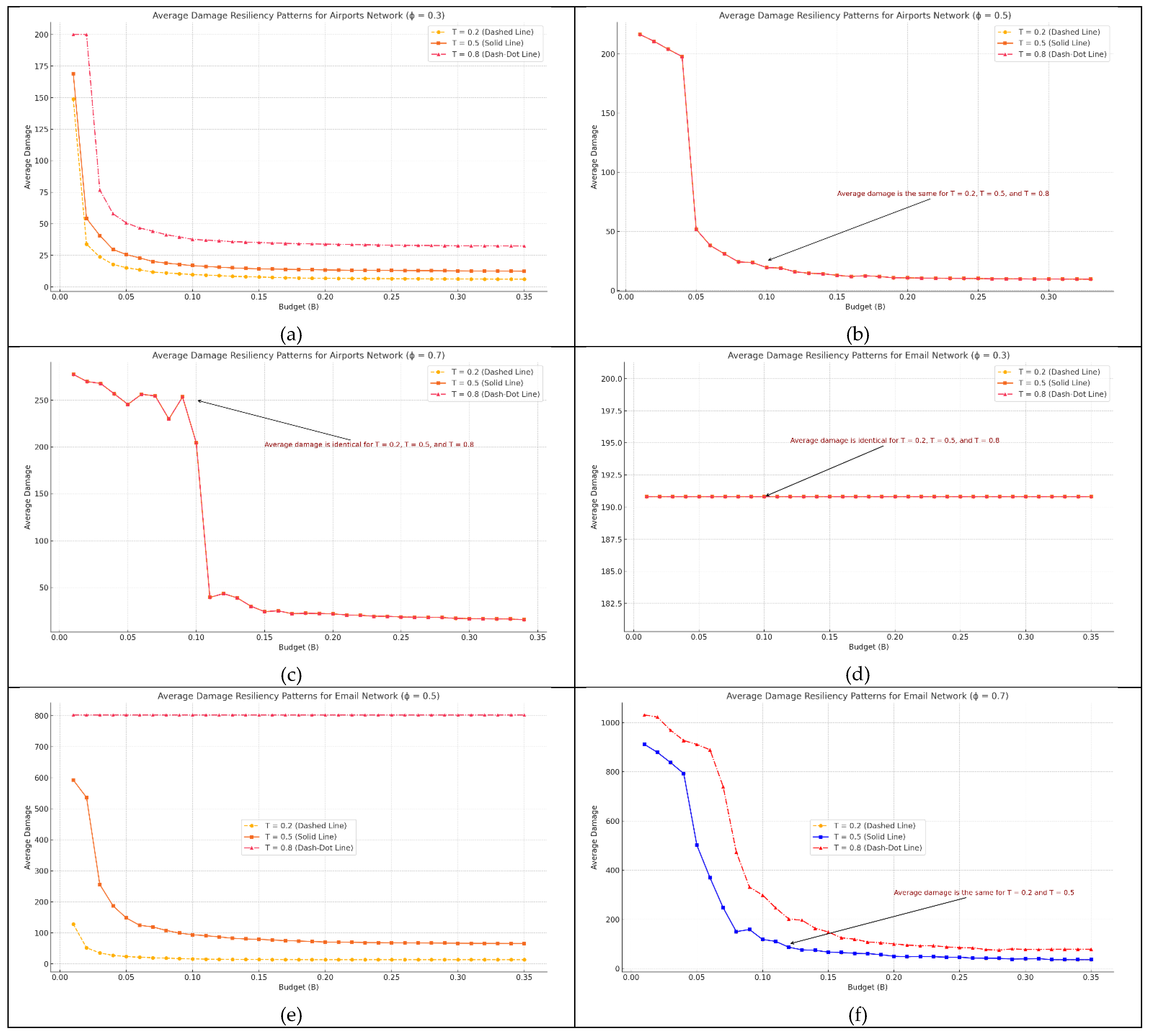

3.2. Resiliency Patterns

3.2.1. Budget Thresholds and Non-Linear Effects

3.2.2. Interplay Between Robustness and Resiliency

3.2.3. Implications

3.2.4. Average Damage as an Alternative Resiliency Metric

3.3 Correlation Between Robustness and Resiliency (Airport Network, 10 % Initial Attack)

3.3.1. Robustness Versus T90 (Panels a–c)

3.3.2. Robustness Versus Average Damage (Panels d–f)

3.3.3. Interpretation and Design Implications

4. Conclusion

- 1.

- Distinct robustness regimes. Robustness declines smoothly under random attack but collapses abruptly under targeted hub removal; increasing mitigates both effects, although the airport network remains consistently more robust owing to its higher mean degree and redundant hub set.

- 2.

- Budget-trigger trade-off in resiliency. Early activation with a modest budget outperforms late activation with a larger budget. A critical “saturation” budget exists—about 12 % of nodes for the airport graph and 10 % for the e-mail graph—beyond which additional resources yield only marginal gains in T90 and average damage.

- 3.

- Weak correlation between robustness and resiliency. Scatter-plot analysis showed that configurations with high robustness can still recover slowly when under-funded, while low-robustness configurations can rebound rapidly if healing is timely and well resourced. A simple multiplicative fit (with) summarizes this interaction.

4.1. Design Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

Abbreviations

| G | Current graph |

| Gdmg | Graph after the cascading-failure phase |

| Grec | Graph returned after the healing phase |

| N | List (or count) of currently functional nodes |

| E | List of currently present edges |

| active | Vector of original degrees |

| fail | Vector of current degrees |

| φc | Degree-loss threshold that triggers node failure |

| φ | Ratio current degrees/ original degrees for a node |

| needrmv | Boolean vector marking nodes with φ<φc |

| cand | Set of nodes that newly fail in the current sweep |

| idx | Indices of nodes sorted by descending original degree |

| rmodes | Initial attack set (random or targeted) |

| inAtv | List of inactive nodes that still have ≥1 active neighbor |

| impact | Primary-impact score: # of endangered neighbors rescued by healing a candidate node |

| d | Secondary score: mean improvement (φ′−φ) for neighbors rescued by that candidate |

| nbx | Set of active neighbors of a specific inactive node |

| d_orig | Original degree of a neighbor |

| d_dmg | Current degree of a neighbor |

| drst | Degree neighbor would have after edge restoration |

| φ′ | Updated degree ratio after hypothetical healing |

| idx2 | Permutation that ranks inAtv lexicographically by primary and secondary impact |

| inAtv_ranked | Final ranked list of inactive nodes to heal |

| B | Healing-budget cap: max # of nodes reactivated in a step |

| healed | Counter for how many nodes have been reactivated so far |

| nb | Individual active neighbor |

| T | Triggering level: fraction of inactive nodes that starts healing |

References

- J. M. Carlson and J. Doyle, “Complexity and robustness,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 99, no. suppl_1, pp. 2538–2545, Feb. 2002. [CrossRef]

- “The Resilience of Networked Infrastructure Systems | Systems Research Series.” Accessed: May 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldscientific.com/worldscibooks/10.1142/8741.

- Z. Huang, C. Wang, A. Nayak, and I. Stojmenovic, “Small Cluster in Cyber Physical Systems: Network Topology, Interdependence and Cascading Failures,” IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst., vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 2340–2351, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, E. Yeh, and E. Modiano, “Robustness of Interdependent Random Geometric Networks,” Jun. 04, 2018, arXiv: arXiv:1709.03032. [CrossRef]

- C. Sergiou, M. Lestas, P. Antoniou, C. Liaskos, and A. Pitsillides, “Complex Systems: A Communication Networks Perspective Towards 6G,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 89007–89030, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Pahwa, C. Scoglio, and A. Scala, “Abruptness of Cascade Failures in Power Grids,” Sci. Rep., vol. 4, no. 1, p. 3694, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Schäfer, D. Witthaut, M. Timme, and V. Latora, “Dynamically induced cascading failures in power grids,” Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 1975, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, B. Chen, X. Chen, and X. Gao, “Cascading Failure Model for Command and Control Networks Based on an m-Order Adjacency Matrix,” Mob. Inf. Syst., vol. 2018, p. e6404136, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. A. Aqqad and X. Zhang, “Modeling command and control systems in wildfire management: characterization of and design for resiliency,” in 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), Nov. 2021, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, D. Duan, G. Hu, and Z. Lu, “Discovering Hidden Group in Financial Transaction Network Using Hidden Markov Model and Genetic Algorithm,” in 2009 Sixth International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery, Aug. 2009, pp. 253–258. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Watts, “A simple model of global cascades on random networks,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 99, no. 9, pp. 5766–5771, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- C. Stegehuis, R. van der Hofstad, and J. S. H. van Leeuwaarden, “Epidemic spreading on complex networks with community structures,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 29748, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Motter and Y.-C. Lai, “Cascade-based attacks on complex networks,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 66, no. 6, p. 065102, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, J. Gao, S. V. Buldyrev, S. Havlin, and H. E. Stanley, “Robustness of interdependent networks under targeted attack,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 83, no. 6, p. 065101, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, S. Shao, H. Wang, S. V. Buldyrev, S. Havlin, and H. E. Stanley, “The robustness of interdependent clustered networks,” EPL Europhys. Lett., vol. 101, no. 1, p. 18002, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, S. Shao, H. E. Stanley, and S. Havlin, “How breadth of degree distribution influences network robustness: Comparing localized and random attacks,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 92, no. 3, p. 032122, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Chattopadhyay, H. Dai, D. Y. Eun, and S. Hosseinalipour, “Designing Optimal Interlink Patterns to Maximize Robustness of Interdependent Networks Against Cascading Failures,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 65, no. 9, pp. 3847–3862, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Motter, “Cascade control and defense in complex networks,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 93, no. 9, p. 098701, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- L. K. Gallos and N. H. Fefferman, “Simple and efficient self-healing strategy for damaged complex networks,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 92, no. 5, p. 052806, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Quattrociocchi, G. Caldarelli, and A. Scala, “Self-Healing Networks: Redundancy and Structure,” PLOS ONE, vol. 9, no. 2, p. e87986, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, J. Zhang, X. Sun, and S. Wandelt, “Network repair based on community structure,” Europhys. Lett., vol. 118, no. 6, p. 68005, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, D. Li, B. Fu, S. Yang, Y. Wang, and G. Lu, “Modeling of self-healing against cascading overload failures in complex networks,” Europhys. Lett., vol. 107, no. 6, p. 68003, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Mari, Y. H. Lee, and M. S. Memon, “Sustainable and Resilient Supply Chain Network Design under Disruption Risks,” Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. A. T. H. L. E. E. N. T. I. E. R. N. E. Y. A. N. D. M. I. C. H. E. L. B. R, “Conceptualizing and Measuring Resilience a Key to Disaster Loss Reduction,” Accessed: May 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Conceptualizing-and-Measuring-Resilience-a-Key-to-K.ATHLEENTIERNEYANDMICHELB/a6a6444d31810223d641cfd900c680c396ef3bec.

- G. Pumpuni-Lenss, T. Blackburn, and A. Garstenauer, “Resilience in Complex Systems: An Agent-Based Approach,” Syst. Eng., vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 158–172, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. A. R. others Nesreen K. Ahmed, and, “USAir97 | Miscellaneous Networks | Network Repository,” Network Data Repository. Accessed: May 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://networkrepository.com/USAir97.php.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).