1. Introduction

Cellular life operates through the precise orchestration of molecular flux across dynamically structured compartments. Classical models of intracellular signaling emphasize linear cascades initiated by receptor-ligand interactions and propagated through protein kinases and gene transcription. However, beneath these complex top-down hierarchies lies a more fundamental mechanism: the thermodynamically driven movement of metabolites and ions through selectively permeable membranes.

In this work, we propose a paradigm shift - from signaling as hierarchical control to metabolism as real-time computation. We frame the cell as a distributed, compartmentalized processor where metabolite concentrations act as dynamic information vectors, and membrane-bound transporters operate as logic gates. These gates regulate access to spatially distinct compartments, shaping each organelle’s biochemical awareness and determining its metabolic response.

This concept builds upon prior synthetic biology efforts, such as metabolic perceptrons - engineered circuits that compute analog outputs based on intracellular metabolite levels [

1].

While these systems were designed artificially, we suggest that nature implements an analogous architecture endogenously. Specifically, the cell’s network of transporters and channels defines a logic-based control layer for biochemical computation, where flux and gating determine what each compartment “knows” and how it acts.

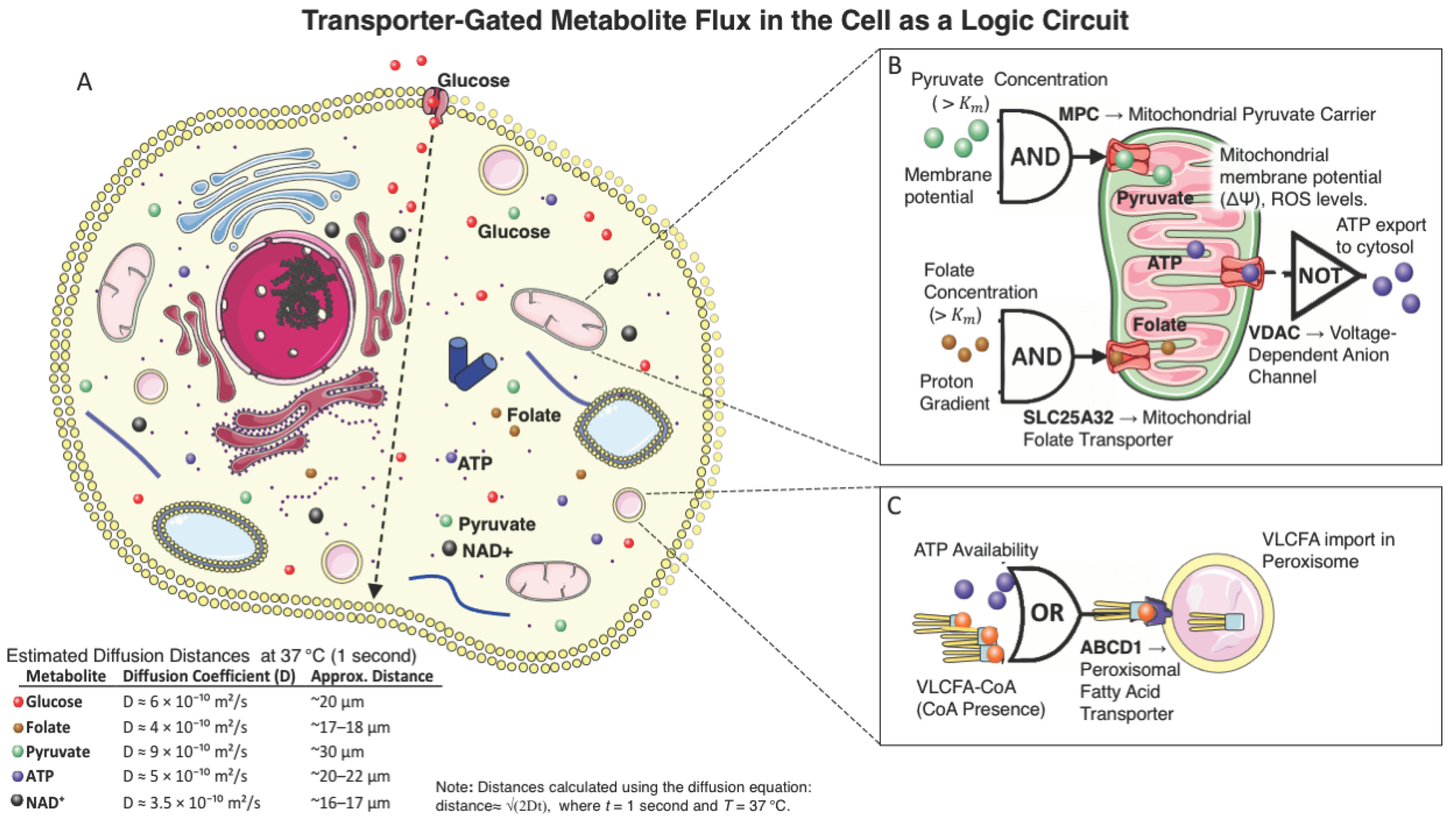

By integrating diffusion dynamics, transporter kinetics, and gating thermodynamics, we derive a formal model of intracellular information flow. We demonstrate how transporters such as the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC), voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), and ABCD1 function not merely as conduits but as computational gates—performing AND, OR, and NOT operations based on substrate availability, membrane potential, and regulatory inputs. This logic gate analogy reveals how cellular behavior emerges from the physical rules of metabolite movement constrained by membrane topology and selective transport.

Recent synthetic biology advances support this framework successfully designed de novo protein logic gates—including AND, OR, NAND, NOR, and NOT—by engineering modular protein-protein interactions with cooperative binding and orthogonal[

2]. These circuits operate robustly across stoichiometric ranges, validating the principle that biological computation can be implemented through molecular gating.

Our model extends this principle to endogenous cellular systems, proposing that natural transporters and channels may fulfill an analogous computational role within metabolic architectures. Just as logic gates in synthetic designs govern output activation based on molecular inputs, we argue that transporters dynamically gate metabolite flux to coordinate intracellular "awareness" across compartments.

2. Diffusion as Information Flow

At 37°C, small molecules such as glucose (~180 Da), ATP (~507 Da), pyruvate (~88 Da), and NAD+ (~663 Da) diffuse with different rates, but all within a range fast enough to be functionally instantaneous inside most cells. The effective diffusion coefficient (D) can be approximated using the Stokes–Einstein equation:

Where: D is the diffusion coefficient; k is the Boltzmann constant; T is the absolute temperature (Kelvin); η is the viscosity of water; r is the hydrodynamic radius of the molecule.

Typical values yield D ≈ 6 ×

m²/s for glucose, allowing such molecules to diffuse across a 20 µm cell in under one second. In an unbounded cytoplasm, diffusion allows enzymes to rapidly experience and respond to metabolic flux. However, the intracellular environment is not a uniform solution. Membrane-bound transporters drastically reduce the effective diffusion coefficient—by several orders of magnitude—necessitating active gating mechanisms (

Figure 1A).

Cellular membranes compartmentalize the cytosol, converting free diffusion into a gated, logic-based computational network.

3. Compartments as Cognitive Modules

Organelles—such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, the nucleus, and endoplasmic reticulum—maintain chemically distinct environments. Each acts as a semi-autonomous module, processing a filtered version of the global metabolic state. These filtering processes define what each compartment “knows,” shaping local responses to systemic changes — an idea supported by Danchin and Sekowska’s framing of metabolism as a logic-based but fuzzy information system[

3] Thus, organelles do not access the cell’s full biochemical state; rather, they receive inputs through specific gates, allowing the compartment to “perceive” only permitted signals. In this model, each compartment performs local computation, and the cell’s behavior emerges from the integration of these distributed, gated processors.

4. Channels as Logic Gates: Concept and Mechanism

We conceptualize transporters and ion channels as biochemical logic gates. Rather than passively permitting molecule movement, they regulate access based on concentration gradients, membrane potential, and regulatory factors—akin to how digital logic gates process voltage inputs.

4.1. Logic Gate Analogy

Inputs: Substrate concentrations or membrane potentials

Gate: Transporter or channel, which opens/closes based on specific conditions

Output: Presence (1) or absence (0) of a metabolite in the target compartment

4.2. Key Transporters as Logic Gates

MPC (Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier) — AND Gate

MPC facilitates pyruvate transport into mitochondria only when both pyruvate availability and mitochondrial membrane potential are optimal, mimicking an AND gate[

4].

Inputs: Cytosolic pyruvate concentration, MPC activity

Output: Pyruvate flux into mitochondria (TCA cycle activation)

Mathematics: Follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics

Where:

- -

J: Flux of metabolite through the channel (mol/s)

- -

: Maximum transport rate

- -

: Substrate concentration at half-maximum flux

- -

[S]: Substrate concentration (e.g., pyruvate in cytosol)

This equation mimics a logic gate’s threshold behavior. If [S] <, flux is low (gate “closed”).

If [S] >> , flux approaches (gate “open”).

For MPC, pyruvate flux into mitochondria depends on cytosolic pyruvate concentration and MPC’s state (open/closed). If inhibited (e.g., by UK5099[

5]),

≈ 0, blocking pyruvate entry, akin to a gate outputting “0.” See also

Figure 1B and C for visual representation of MPC and other logic gates.

VDAC (Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel) - NOT Gate

VDAC closes in response to high membrane potential, inhibiting metabolite flow, which resembles a NOT gate operation[

6].

Input: Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ), ROS levels.

Output: ATP export to cytosol

Behavior: Under oxidative stress or low ΔΨ, VDAC closes, preventing ATP flux — analogous to a NOT gate.

Model: Open probability approximated using Boltzmann distribution

VDAC’s open probability can be modeled with a Boltzmann distribution:

- -

: Free energy change (influenced by ΔΨ)

- -

: Gas constant (8.314 J )

- -

T: Temperature (310 K)

Where ΔG is affected by membrane potential and oxidative status.

If (ΔΨ) drops, decreases, closing VDAC and isolating mitochondria, similar to a NOT gate flipping the output.

ABCD1 (Peroxisomal VLCFA Transporter) — OR Gate

ABCD1 transports very long-chain fatty acids when either ATP or coenzyme A is available, functioning like an OR gate[

7].

Inputs: Very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and ABCD1 expression

Output: Fatty acid import into peroxisomes for β-oxidation

Logic: Transport occurs if either substrate concentration is high OR transporter is upregulated.

SLC25A32 (Mitochondrial Folate Carrier) — AND Gate

SLC25A32 transports folate into mitochondria only when both folate and a proton gradient are present, analogous to an AND gate[

8].

Inputs: Cytosolic folate and transporter expression

Output: Folate delivery to mitochondria, enabling one-carbon metabolism and NADPH production

4.3. Gating Logic as Computation

We can represent transporter logic mathematically. For MPC:

Let:

[Pyr]: Pyruvate concentration in cytosol

G: Gate status (1 = open, 0 = closed)

: Flux of pyruvate into mitochondria

: Maximum transport rate

: Substrate concentration at half-maximum flux

If G = 1 and [Pyr] >> : high flux → mitochondria "see" glycolytic activity.

If G = 0: zero flux → mitochondria "blind" to glycolysis

Figure 1.

Transporter-Gated Metabolite Flux in the Cell as a Logic Circuit.

Figure 1.

Transporter-Gated Metabolite Flux in the Cell as a Logic Circuit.

This figure illustrates how intracellular metabolite transport behaves like logic gate operations. Panel A shows glucose, ATP, pyruvate, NAD⁺, and folate diffusing through the cytosol, while panels B and C highlight transporter gating. The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) and folate transporter (SLC25A32) act as AND gates, requiring both substrate availability and electrochemical gradients. VDAC functions as a NOT gate, restricting ATP export under high mitochondrial membrane potential or ROS. ABCD1 in the peroxisome serves as an OR gate, triggered by either ATP or VLCFA-CoA. Diffusion distances (~16–30 µm) were estimated for each metabolite at 37 °C using known cytosolic diffusion coefficients.

Visual elements adapted from Servier Medical Art, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

6. Implications for Disease and Therapy

Transporter dysfunction disrupts the biochemical logic of the cell, cutting off compartments from key metabolites and degrading internal awareness. In this model, disease is understood not merely as a loss of function, but as a loss of informational flow - a collapse in the logic network that normally governs compartmental coordination. Below are key examples illustrating this principle:

6.1. X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD)

Mutations in ABCD1, the peroxisomal transporter responsible for importing very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), impair peroxisomal access to its target substrates. As a result, β-oxidation is blocked, VLCFAs accumulate in the cytosol, and lipid toxicity ensues. The peroxisome becomes “blind” to the very molecules it must process, leading to widespread membrane dysfunction and neurodegeneration[

9].

6.2. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

In autism, impaired function of mitochondrial SLC transporters such as SLC25A12 disrupts the exchange of aspartate and glutamate, leading to redox imbalance and impaired neuronal energy metabolism [

10]. This limits the mitochondrion’s ability to respond to cytosolic cues, silencing its metabolic “awareness” and triggering shifts in neurotransmitter production, oxidative stress, and synaptic dysfunction. Mitochondrial dysfunction in other SLC transporters, such as

SLC25A32, which mediates mitochondrial folate transport[

11], has also been implicated in subsets of ASD. In such cases, one-carbon metabolism and NADPH synthesis are impaired, further reducing mitochondrial redox capacity.

However, not all transporters are suppressed. For example,

SLC25A1, the mitochondrial citrate carrier (CIC), is frequently

upregulated in ASD and related neurodevelopmental models[

12]. Recent studies show that increased expression of SLC25A1 causes an

autistic-like phenotype with altered neuronal morphology and disrupted metabolic signaling. This suggests that the cell, facing blocked canonical pathways, attempts to restore awareness by

rerouting citrate flux through SLC25A1—an adaptive but potentially maladaptive logic transformation. The result is metabolic reprogramming at the compartment level, driven by the cell’s attempt to preserve internal information coherence despite upstream disruptions.

This compensatory behavior supports the core hypothesis: autism is not simply a metabolic deficit, but a reorganized state of intracellular computation, with altered transporter logic reflecting the cell's effort to maintain functional awareness.

6.3. Type 2 Diabetes and the Logic of Pyruvate Misrouting

In type 2 diabetes (T2D), mitochondrial dysfunction is commonly attributed to nutrient overload and insulin resistance. However, our systems-level model reframes this phenomenon as a failure of intracellular information processing—specifically, a logic-level breakdown in metabolite routing. In this framework, transporters act as metabolic “logic gates” that determine the direction and integration of substrate flow. When these gates are disrupted, key metabolic pathways are misrouted, leading to systemic dysfunction.

Notably, inhibition or downregulation of glucose transporters—SLC2A1 (GLUT1) and SLC2A3 (GLUT3)—has been documented in T2D and may reflect impaired substrate entry into the glycolytic pathway[

13,

14]. This results in decreased glycolytic throughput, aligning with our broader metabolic collapse model, which implicates intracellular cofactor deficiencies [

15,

16,

17], and impaired mitochondrial enzyme function [

18] as upstream drivers.

As pyruvate accumulates in the cytoplasm, further disruption occurs at the level of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC), whose restriction limits pyruvate flux into the mitochondria. Consequently, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity is reduced, and downstream metabolic effects are observed. Transcriptomic and metabolomic data reveal several key compensatory and maladaptive responses:

Cytosolic glucose accumulation, which leads to carbon shunting into the polyol pathway, increasing sorbitol and oxidative stress [

19].

Enhanced branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism, mediated by AMPK and mTOR signaling, suggesting that targeted MPC inhibition reprograms energy substrate use to alleviate diabetic phenotypes [

20].

Reduced acetyl-CoA generation, impairing one-carbon metabolism and diminishing the capacity for myelin synthesis and repair [

15].

Collectively, these shifts reflect a breakdown in “biochemical awareness,” where the logic gates (transporters) that normally synchronize energy metabolism, redox balance, and signaling across compartments become desynchronized. This model underscores the importance of metabolic routing and intracellular transporters not merely as passive carriers, but as active processors of physiological information.

7. Therapeutic Framework: Restoring Intracellular Awareness

This logic-based model of autism implies a therapeutic strategy that goes beyond simple supplementation. The goal is not only to replace missing metabolites, but to restore intracellular computation by re-establishing logic coherence across compartments.

This involves three coordinated steps:

Identification of Core Substrate Flow Deficits:Determine which intracellular metabolites (e.g., folate, NAD⁺, glutamate, pyruvate) are failing to reach their target compartments due to transporter suppression or gating collapse. These deficits represent primary informational bottlenecks in cellular awareness.

Transcriptional Equivalency Mapping:Analyze compensatory transcription patterns to identify which transporters or enzymes are being downregulated or upregulated in an attempt to reroute metabolic flow. This reveals the cell’s current logic state—and its attempt to restore coherence.

Therapeutic Reprogramming of Gating Architecture:Restore substrate availability through precision nutrient supplementation, while increasing metabolic resistance (e.g., NAD⁺, ATP, folate tension) to activate feedback loops that upregulate necessary transporters and enzymes. This encourages the cell to reorganize its transporter and enzyme network, recovering the lost biochemical logic.

Ultimately, therapy becomes not a static replacement of molecules, but a reconstruction of cellular information flow - a healing of the intracellular computation that underlies metabolism, signaling, and synaptic function.

8. The Cell as a Biochemical Computer

Cells operate as distributed computational systems, with metabolites as logic variables, transporters as gates, and compartments as processors. Intelligence emerges from parallel molecular flows, governed by thermodynamics and kinetics. Unlike sequential electronic circuits, this system runs simultaneously, integrating local metabolite movements into global biochemical coherence.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

This model is primarily theoretical, offering a novel framework for conceptualizing intracellular metabolism as a logic-based computational network. While we provide mathematical analogies and mechanistic reasoning to support the interpretation of transporters such as MPC, VDAC, ABCD1, and SLC25A32 as logic gates, no direct experimental evidence currently validates this framework. The referenced studies [

8,

20] provide biochemical and structural insights into gating mechanisms but do not explicitly demonstrate Boolean computation or logical integration by endogenous transporters.

As such, the model remains speculative and vulnerable to criticism in the absence of empirical testing. Moreover, presentation constraints—such as the simplification of multi-input dynamics into binary gates—limit its resolution. Future research must explore whether such logic operations can be measured experimentally, for example, by probing transporter kinetics under combinatorial input conditions or through synthetic rewiring of gating domains in live-cell systems.

Despite these limitations, the framework proposed here is, to our knowledge, the first to interpret intracellular metabolite flow using information theory and logic gate analogies grounded in transport biology. We believe this conceptual shift can open new avenues for understanding disease as a breakdown of distributed biochemical computation—and for designing therapies aimed at restoring informational coherence.

10. Conclusions

We propose that intracellular transporters and compartments function as a distributed network of logic gates, processing biochemical inputs into compartment-specific outputs. This reframes metabolism as an active system of information flow, where disease reflects breakdowns in intracellular computation. Although theoretical, the model offers a novel lens for interpreting transporter function. It invites future validation and opens new directions for systems-level therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

Selected visual components in Figure 1 were adapted from Servier Medical Art (

https://smart.servier.com), which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

References

- A. Pandi o.fl., „Metabolic perceptrons for neural computing in biological systems“, Nat. Commun., b. 10, tbl. 1, 2019.

- Z. Chen o.fl., „De novo design of protein logic gates“, Science (80-. )., b. 368, tbl. 6486, 2020.

- A. Danchin og A. Sekowska, „The logic of metabolism and its fuzzy consequences“, Environmental Microbiology, b. 16, tbl. 1. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Bender, G. Pena, og J. Martinou, „Regulation of mitochondrial pyruvate uptake by alternative pyruvate carrier complexes“, EMBO J., b. 34, tbl. 7, 2015.

- J. Wang o.fl., „UK-5099, a mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibitor, recovers impaired neutrophil maturation caused by AK2 deficiency in human pluripotent stem cell models“, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., b. 687, 2023.

- V. Shoshan-Barmatz, V. De Pinto, M. Zweckstetter, Z. Raviv, N. Keinan, og N. Arbel, „VDAC, a multi-functional mitochondrial protein regulating cell life and death“, Molecular Aspects of Medicine, b. 31, tbl. 3. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. P. Chen o.fl., „Structural basis of substrate recognition and translocation by human very long-chain fatty acid transporter ABCD1“, Nat. Commun., b. 13, tbl. 1, 2022.

- M. Z. Peng o.fl., „Mitochondrial FAD shortage in SLC25A32 deficiency affects folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism“, Cell. Mol. Life Sci., b. 79, tbl. 7, 2022.

- J. Berger, S. Forss-Petter, og F. S. Eichler, „Pathophysiology of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy“, Biochimie, b. 98, tbl. 1. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu o.fl., „Association between genetic variants in SLC25A12 and risk of autism spectrum disorders: An integrated meta-analysis“, Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet., b. 168, tbl. 4, 2015.

- D. M. E. I. Hellebrekers o.fl., „Novel SLC25A32 mutation in a patient with a severe neuromuscular phenotype“, Eur. J. Hum. Genet., b. 25, tbl. 7, 2017.

- M. J. Rigby o.fl., „Increased expression of SLC25A1/CIC causes an autistic-like phenotype with altered neuron morphology“, Brain, b. 145, tbl. 2, 2022.

- E. Szabó o.fl., „Alterations in erythrocyte membrane transporter expression levels in type 2 diabetic patients“, Sci. Rep., b. 11, tbl. 1, 2021.

- C. Rong, X. Cui, J. Chen, Y. Qian, R. Jia, og Y. Hu, „DNA methylation profiles in placenta and its association with gestational diabetes mellitus“, Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes, b. 123, tbl. 5, 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Ismail o.fl., „Vitamin B5 (D-pantothenic acid) localizes in myelinated structures of the rat brain: Potential role for cerebral vitamin B5 stores in local myelin homeostasis“, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., b. 522, tbl. 1, 2020.

- S. Porasuphatana, S. Suddee, A. Nartnampong, J. Konsil, B. H. Busakorn, og A. Santaweesuk, „Glycemic and oxidative status of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus following oral administration of alphalipoic acid: A randomized double-blinded placebocontrolled study“, Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr., b. 21, tbl. 1, 2012.

- Y. Zhang o.fl., „Influence of biotin intervention on glycemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis“, Frontiers in Nutrition, b. 9. 2022.

- D. E. Kelley, J. He, E. V. Menshikova, og V. B. Ritov, „Dysfunction of mitochondria in human skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes“, Diabetes, b. 51, tbl. 10, 2002. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Chitra o.fl., „Status of oxidative stress markers, advanced glycation index, and polyol pathway in age-related cataract subjects with and without diabetes“, Exp. Eye Res., b. 200, 2020.

- K. S. McCommis og B. N. Finck, „The Hepatic Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier as a Regulator of Systemic Metabolism and a Therapeutic Target for Treating Metabolic Disease“, Biomolecules, b. 13, tbl. 2. 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).