1. INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent a prevalent bacterial infection in children. The clinical manifestations can often be non-specific, particularly in younger populations, which underscores the necessity of considering this diagnosis in all children and teenagers.

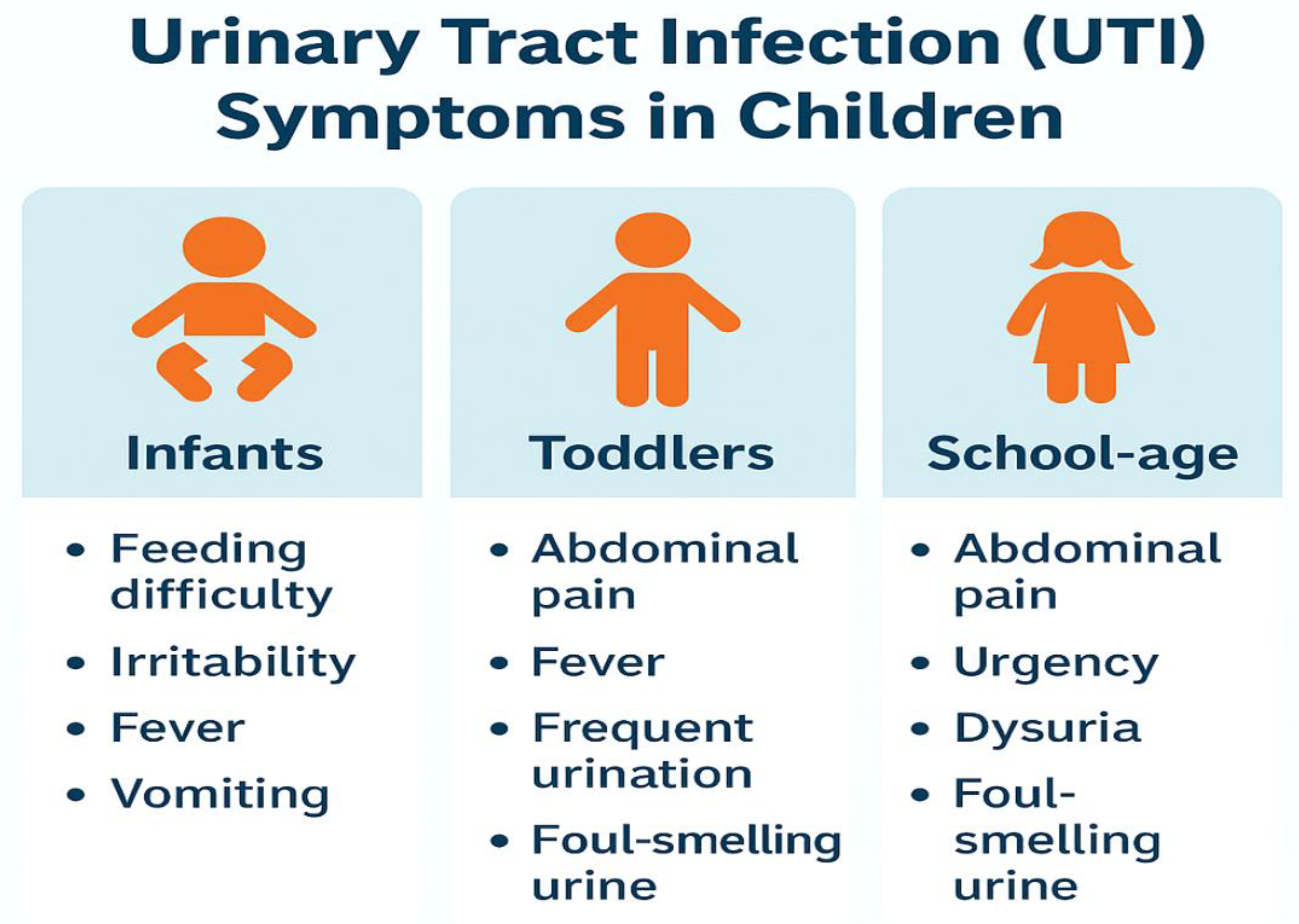

Figure 1.

Infographic showing UTI symptoms in children across age groups (infants, toddlers, school-age).

Figure 1.

Infographic showing UTI symptoms in children across age groups (infants, toddlers, school-age).

In practical terms, UTIs in children can be challenging to identify. In developed nations, approximately 7% of febrile, pre-continent infants and children seeking medical attention are diagnosed with a UTI (1), with even higher rates reported in developing countries (2).

Consequently, they frequently emerge as a potential diagnosis among the numerous cases of unexplained fever that clinicians encounter in general practice, emergency departments, and hospital environments. Prompt and precise diagnosis of UTIs is crucial, as misdiagnosis, overlooked cases, and delays in treatment can lead to adverse outcomes. Infants, particularly neonates, represent the demographic most susceptible to acute complications associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs). This population also exhibits the least specific clinical manifestations of UTIs, making the collection of urine samples for diagnostic evaluation particularly challenging. While the majority of children diagnosed with UTIs experience complete recovery, there exists a risk of serious short-term complications such as urosepsis and meningitis, as well as long-term issues including renal scarring, impairment, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease, particularly when caused by antimicrobial-resistant pathogens (3, 4). Although these severe outcomes occur in a relatively small percentage of cases, the high incidence of UTIs in pediatric populations results in a notable absolute frequency of these complications.

Globally, UTIs account for 5–14% of pediatric outpatient visits and a considerable proportion of hospital admissions in children under five years of age (1). A growing body of evidence has identified Gram-negative uropathogens, particularly Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as the predominant etiologic agents in both community-acquired and hospital-acquired pediatric UTIs (5, 6). These organisms frequently harbour resistance determinants, notably extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), which compromise the efficacy of standard therapeutic regimens (7, 8).

ESBLs are enzymes that hydrolyse penicillins, third-generation cephalosporins, and aztreonam, rendering these antibiotics ineffective. Their production is often associated with multidrug resistance (MDR), plasmid-mediated gene transfer, and the co-existence of other resistance mechanisms, such as carbapenemases and aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. The CTX-M family of ESBLs, particularly CTX-M-15, has become globally dominant, replacing the earlier TEM and SHV types in clinical isolates. In pediatric settings, the implications of ESBL production are profound, as treatment options become limited and more toxic or expensive alternatives, such as carbapenems, must be used (9).

The pediatric population is especially vulnerable to the consequences of antimicrobial resistance due to age-related immunological immaturity, higher rates of congenital anomalies, and limited pharmacologic options for young children. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where laboratory diagnostics and antimicrobial stewardship infrastructures are often underdeveloped, ESBL-producing organisms frequently go undetected, leading to inappropriate empirical therapy and increased morbidity. Nigeria exemplifies this situation, with recent studies indicating a high prevalence of ESBL-producing uropathogens among children, including the widespread presence of blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes.

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the global and regional burden of ESBL-producing uropathogens in pediatric populations, with a particular emphasis on Nigeria and Sub-Saharan Africa. It explores the molecular biology of ESBL production, clinical and epidemiological trends, diagnostic challenges, and treatment implications. Finally, the review highlights the critical role of antimicrobial stewardship in addressing this escalating public health threat and offers actionable recommendations for clinicians, microbiologists, and policymakers.

2. METHODOLOGY

This literature review was conducted using a systematic and comprehensive search strategy to ensure broad coverage and scholarly rigour. The approach aimed to identify peer-reviewed studies and grey literature relevant to the prevalence, molecular characteristics, clinical impact, and antimicrobial resistance patterns of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing uropathogens in pediatric populations.

2.1. Databases Searched

The electronic databases searched included:

In addition, grey literature such as national surveillance reports, WHO policy documents, and data from the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) were reviewed to complement published sources and ensure regional context.

2.2. Search Terms and Strategy

A combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords were used, including: "Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase" OR "ESBL"; "Pediatric" OR "Children" OR "Child Health"; "Urinary Tract Infections" OR "UTI"; "Antimicrobial Resistance" OR "AMR"; "CTX-M" OR "TEM" OR "SHV"; "Nigeria" OR "Sub-Saharan Africa".

Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to refine searches. Searches were limited to articles published in English between January 2000 and April 2025.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

Studies published in peer-reviewed journals or validated surveillance sources.

Articles focusing on pediatric populations (0–18 years).

Reports addressing ESBL-producing organisms in urinary tract infections.

Studies that discussed molecular biology, epidemiology, clinical impact, diagnostics, or treatment implications.

Exclusion Criteria:

Articles not in English.

Studies not involving pediatric subjects.

Case reports and opinion pieces without primary data.

Studies focused solely on adult or animal models.

2.4. Selection and Review Process

The initial search yielded approximately 480 articles. After removal of duplicates, 410 articles were screened by title and abstract. Full texts of 135 potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 92 articles were included in the final review.

The literature was reviewed thematically under the following categories: global and regional prevalence, molecular ESBL gene profiles, risk factors and clinical implications, diagnostics, and antimicrobial stewardship. The findings were critically analysed to provide a coherent narrative aligned with the objectives of this review. Citation management software (Zotero) was used to organise references and ensure accuracy in citation formatting.

3. GLOBAL EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ESBL-PRODUCING UROPATHOGENS

The rise of antibiotic resistance presents a significant global challenge across various infections, including urinary tract infections (11). There is a growing recognition of the resistance exhibited by prevalent uropathogens, particularly Escherichia coli, to the first-line empiric antibiotics recommended for treatment (9, 12).

The fundamental factor contributing to the rise in antibiotic resistance is the acquisition of advanced characteristics of beta-lactamase enzymes. Certain gram-negative uropathogens can inactivate beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillin and first-generation cephalosporins, owing to their natural beta-lactamase enzymes. Furthermore, some of these pathogens have adapted to exhibit multidrug resistance, allowing them to hydrolyse and neutralise extended-spectrum cephalosporins and carbapenem antibiotics (13). These organisms are categorised as producers of ESBL.

The worldwide distribution of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing uropathogens is characterised by regional variability, influenced by differences in antibiotic use, infection control practices, healthcare infrastructure, and surveillance capabilities. Over the past two decades, ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae have transitioned from isolated hospital outbreaks to widespread community-acquired infections, with pediatric populations increasingly affected (14).

The guidelines established in the United States advocate for the selection of antibiotics based on local sensitivity patterns, with the recommendation to modify these choices once the sensitivity profiles of the isolated uropathogens are determined. However, it is recognised that relying on local sensitivity data for the initial selection of antimicrobial agents can pose challenges due to the potential unavailability of relevant information. Notably, there is a growing incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) exhibiting resistance to these antibiotics in Australia, the UK, and the USA (9, 15). While extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) organisms were predominantly identified in hospital environments, there is now an observable increase in ESBL UTI cases within community settings (14).

The rise of ESBLs poses a major public health issue, especially among children and teenagers, where urinary tract infections (UTIs) are becoming common. The increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing uropathogens in children highlights the urgent need for a thorough investigation into these resistant strains' distribution and genetic characteristics. For instance, research by Parajuli et al. (16) showed that 32.6% of isolates from children harboured ESBL genes, with E. coli and K. pneumoniae identified as the predominant uropathogens. This observation is corroborated by another study indicating that 30.5% of isolated E. coli strains were ESBL producers, with the TEM gene being the most frequently detected (49%), followed by SHV (44%) and CTX-M (28%). In a broader context, Ferreira et al. (17) reported that all 25 isolates examined in their research were ESBL producers, with 100% carrying the blaKPC and blaTEM genes. Additionally, Reuland et al. (18) noted that among 1,695 samples, 8.6% were classified as ESBL-E, predominantly consisting of E. coli (91%), with the CTX-M group identified as the most prevalent ESBL genes. These studies collectively emphasise the widespread presence of ESBL genes, posing a considerable threat to uropathogens in UTIs in children and teenagers.

In Europe, surveillance data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reveal rising rates of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli among pediatric UTI cases, particularly in southern and eastern Europe (19). In Italy and Spain, the prevalence of ESBL producers among pediatric isolates ranges between 20% and 40% (20).

In Asia, the burden is even greater. Studies from India, Pakistan, and China have reported ESBL prevalence rates exceeding 60% among pediatric uropathogens, with CTX-M-15 emerging as the dominant genotype. This is compounded by widespread over-the-counter antibiotic use, limited regulation, and inadequate antimicrobial stewardship (21).

Sub-Saharan Africa presents a particularly alarming picture due to the convergence of poor sanitation, high infectious disease burden, and weak laboratory diagnostic networks. Data from Nigeria, Kenya and Burkina Faso indicate ESBL prevalence rates of 40–70% in pediatric UTIs (22, 23, 24). A recent study in Lagos showed that over 75% of Gram-negative uropathogens harboured at least one ESBL gene, underscoring the magnitude of the problem (5).

In the Americas, while the prevalence of ESBL producers is lower in North America due to stronger regulatory frameworks, outbreaks of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) highlight the vulnerability of hospitalised infants (25). In Latin America, countries such as Brazil and Argentina report prevalence rates of 30–50% among pediatric UTI pathogens (26, 27).

Global data also demonstrate a trend toward the spread of community-onset ESBL infections in children, challenging the historical notion that such infections were confined to hospitals (28). The mobility of resistance genes via plasmids, coupled with global travel and agricultural antibiotic use, facilitates cross-border dissemination (29, 30).

These findings point to a clear need for global coordination in surveillance, improved antimicrobial stewardship in pediatric care, and equitable access to diagnostic tools and effective antimicrobials. In the sections that follow, we delve deeper into the molecular mechanisms underpinning ESBL production and their clinical consequences in pediatric populations.

4. REGIONAL FOCUS: NIGERIA AND SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Nigeria, faces a disproportionate burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) due to systemic healthcare challenges, high infectious disease prevalence, and the widespread availability of over-the-counter antibiotics (31, 32). The region's pediatric population is especially vulnerable, and emerging evidence suggests that ESBL-producing uropathogens are alarmingly prevalent among children with UTIs (33).

4.1. Prevalence and Clinical Trends in Nigeria

Recent studies conducted in urban and semi-urban centres in Nigeria have consistently reported high prevalence rates of ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae in pediatric urine isolates. In a molecular surveillance study in Lagos, 165 urine samples were collected from children aged 0–18 years presenting with UTI symptoms. Of these, 75.5% of Gram-negative isolates were confirmed to harbour ESBL genes, predominantly blaCTX-M-1 and blaTEM (34). Similar findings have been reported in Abuja, Port Harcourt, and Enugu, pointing to a nationwide trend of increasing ESBL incidence in pediatric uropathogens (35, 36).

4.2. Molecular Profiles and Resistance Patterns

The molecular landscape of ESBL-producing organisms in Nigeria mirrors global trends, with CTX-M-15 emerging as the most dominant variant (37). Plasmid profiling reveals that blaCTX-M-1 is frequently co-located with resistance determinants for fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides, contributing to multidrug resistance. Resistance to commonly prescribed antibiotics such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin exceeds 70%, leaving carbapenems, fosfomycin, and nitrofurantoin as the only reliable options in many clinical settings. However, these agents are often unavailable or unaffordable in Nigeria's public healthcare institutions (38).

4.3. Contributing Factors to the ESBL Burden

Multiple systemic and behavioural factors contribute to the high prevalence of ESBLs in Nigeria. These include:

Inadequate diagnostic infrastructure, resulting in reliance on empirical therapy (39).

Poor regulation of antibiotic sales, leading to widespread self-medication and overuse (40).

Lack of pediatric-specific antimicrobial stewardship programs, particularly in primary and secondary care settings (41).

Suboptimal infection control practices in both outpatient clinics and hospital wards (42).

High patient-to-clinician ratios reduce the feasibility of individualised care (43).

4.4. Surveillance and Research Gaps

There is a notable paucity of large-scale surveillance data on antimicrobial resistance in Nigerian pediatric populations. Most available studies are institution-specific and conducted over limited timeframes (34). Molecular diagnostics are rarely utilised in routine clinical settings and are mostly confined to academic research (44). This lack of reliable and representative data significantly hampers the development of evidence-based treatment guidelines and policy interventions.

4.5. Regional Comparisons

Compared to neighbouring countries like Ghana and Cameroon, Nigeria appears to have a higher burden of ESBL-producing pediatric uropathogens. A 2020 study in Ghana reported an ESBL prevalence of 48% in pediatric UTIs—substantially lower than the >70% reported across multiple Nigerian centres (45). While differences in study methodologies may limit direct comparisons, the collective regional data highlight Sub-Saharan Africa as a critical ESBL hotspot, warranting urgent regional coordination on surveillance and intervention.

This regional focus underscores the urgent need for context-specific data and targeted interventions. In the next sections, we will explore how these patterns affect clinical management and diagnostic approaches in pediatric care.

5. MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OF ESBLS IN PEDIATRIC UTIS

The molecular underpinnings of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production in uropathogenic bacteria are complex and multifactorial, involving both chromosomal mutations and the horizontal acquisition of resistance genes. Among pediatric populations, where empirical treatment is common and diagnostic delays are frequent, understanding the molecular biology of ESBLs is essential for tailoring effective treatment and containment strategies (46, 47).

ESBLs are primarily encoded by genes located on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, integrons, and transposons, which facilitate their horizontal transfer among bacterial populations (48). The most clinically significant ESBLs belong to three main families: TEM (Temoniera), SHV (sulfhydryl-variable), and CTX-M (cefotaximase). Of these, CTX-M enzymes have emerged as the most prevalent globally, particularly in pediatric isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae (49, 50).

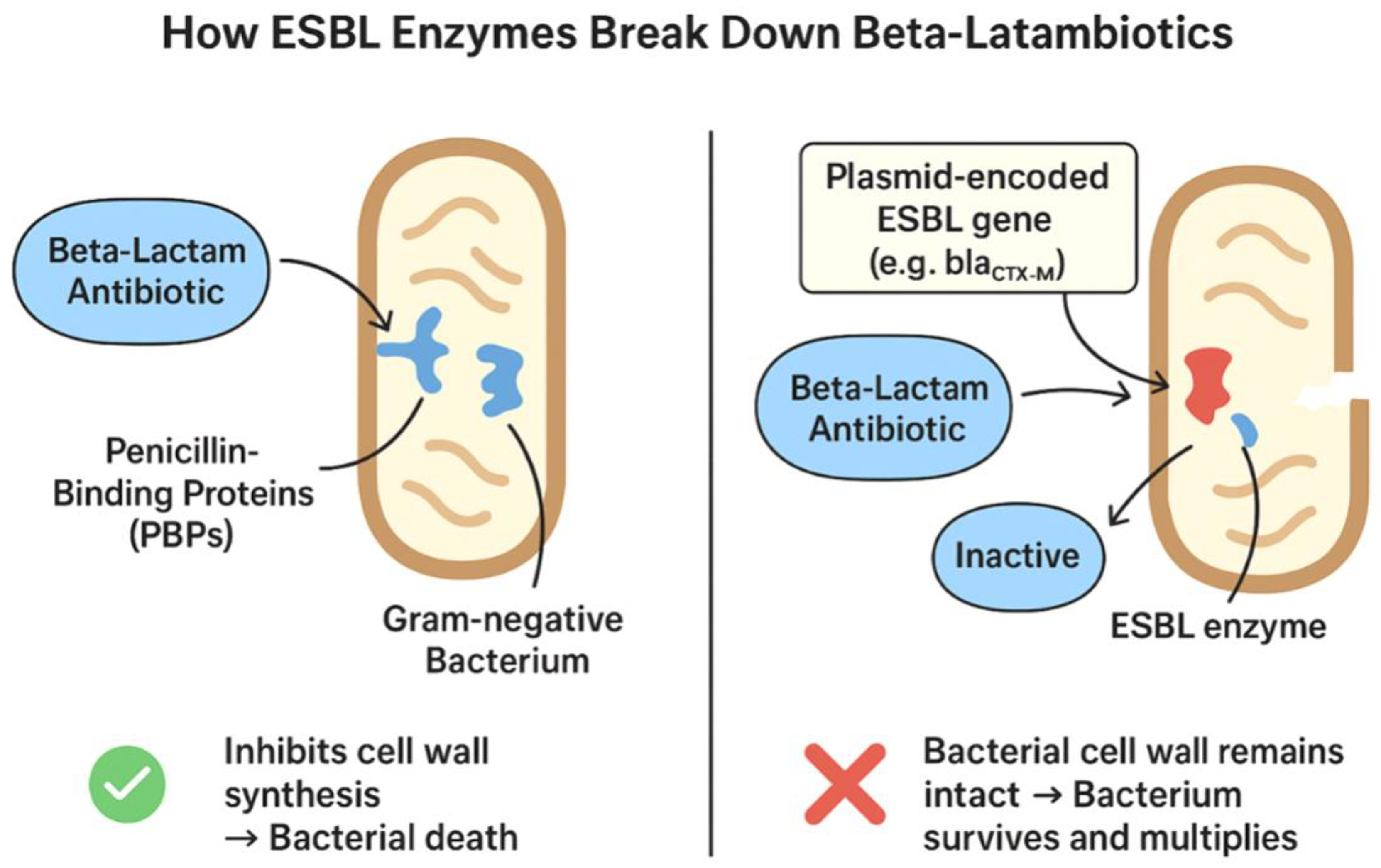

Figure 2.

Mechanism of ESBL-mediated resistance. In non-ESBL-producing bacteria, beta-lactam antibiotics bind to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), inhibiting cell wall synthesis.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of ESBL-mediated resistance. In non-ESBL-producing bacteria, beta-lactam antibiotics bind to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), inhibiting cell wall synthesis.

5.1. The TEM and SHV Families

Historically, the TEM and SHV beta-lactamases were the first identified ESBLs, originally found in E. coli and K. pneumoniae, respectively. TEM-1 and SHV-1 are the progenitors of these families and do not possess extended-spectrum activity. However, point mutations in these genes have resulted in derivatives such as TEM-3 and SHV-2, which can hydrolyse third-generation cephalosporins (51, 52). Although still relevant, these variants are now overshadowed by CTX-M types in many regions.

5.2. The CTX-M Family

CTX-M enzymes are now the dominant ESBLs in both adult and pediatric populations. These enzymes are subdivided into five main groups based on amino acid sequence similarity: CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, CTX-M-8, CTX-M-9, and CTX-M-25. CTX-M-15, a member of the CTX-M-1 group, has been particularly successful in spreading globally (53; 54). Its prevalence in pediatric uropathogens is attributed to its localisation on conjugative plasmids that often carry other resistance determinants, such as qnr (quinolone resistance) and aac(6')-Ib (aminoglycoside resistance) (55).

5.3. Genetic Context and Co-Resistance

ESBL genes are frequently co-located with other antimicrobial resistance genes, contributing to multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotypes. This genetic linkage means that the use of one antibiotic class can co-select for resistance to others, exacerbating the resistance crisis (56). In pediatric UTIs, co-resistance to fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is common among ESBL-producing strains (57).

5.4. Clonal Expansion and Horizontal Gene Transfer

Certain clones, such as E. coli ST131 and K. pneumoniae ST258, are known for acquiring and disseminating ESBL genes. ST131, in particular, has been identified in pediatric isolates worldwide and is strongly associated with CTX-M-15 production (58; 59). Clonal expansion of such high-risk clones further entrenches resistance within both hospital and community settings.

5.5. Implications for Molecular Surveillance

Molecular characterisation of ESBL genes is crucial for understanding the dynamics of resistance and tailoring stewardship efforts. PCR, sequencing, and more recently, whole genome sequencing (WGS), provide insights into the genetic diversity and evolution of ESBL-producing pathogens (60). However, the adoption of these techniques in many LMICs, including Nigeria, remains limited due to cost and technical capacity constraints (44, 61).

Understanding the molecular basis of ESBL production provides a foundation for designing effective diagnostic, therapeutic, and surveillance strategies. In pediatric populations, where rapid and accurate identification of resistance determinants can significantly impact outcomes, the role of molecular tools is indispensable and increasingly urgent.

6. CLINICAL IMPACT AND RISK FACTORS IN PEDIATRIC POPULATIONS

The clinical consequences of UTIs caused by ESBL-producing organisms in children are multifaceted, ranging from treatment failure and prolonged illness to severe complications such as pyelonephritis, renal scarring, and recurrent infections (1). In neonates and infants, UTIs can rapidly progress to urosepsis, particularly when empirical treatments are ineffective against resistant strains, underscoring the urgent need for timely and accurate diagnosis and appropriate therapy (25, 62).

6.1. Disease Severity and Complications

Children infected with ESBL-producing uropathogens often experience longer durations of fever, delayed clinical response, and increased hospitalisation rates compared to those with susceptible strains (63). Ineffective empirical treatment—especially with third-generation cephalosporins—may result in progression to upper urinary tract infection or bacteremia. Recurrent infections have been linked to renal parenchymal damage and long-term sequelae such as hypertension and chronic kidney disease (64).

6.2. Recurrent UTIs and Healthcare Burden

Recurrent UTIs are a common issue among pediatric patients previously infected with ESBL-producing bacteria. These episodes often lead to increased outpatient visits, repeat hospital admissions, and extended antibiotic therapy (65). Children with structural anomalies or immunodeficiencies face elevated risks for recurrence and complications (66).

6.3. Risk Factors for ESBL Colonization and Infection

Multiple risk factors are associated with colonization and infection by ESBL-producing organisms:

Prior antibiotic exposure, particularly to cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones (67).

Hospitalisation, catheterisation, and recent medical procedures (68).

Congenital urinary anomalies (e.g., vesicoureteral reflux) (69).

Poor hygiene and inadequate sanitation (70).

Household or community-level transmission (71).

6.4. Vulnerable Subgroups

Premature infants, immunocompromised children (e.g., HIV or cancer patients), and those on long-term antibiotic prophylaxis are more likely to harbour multidrug-resistant bacteria (72). Additionally, limited pharmacologic options for these subgroups complicate treatment and increase the risk of poor outcomes.

6.5. Psychological and Social Impact

Recurrent infections, hospitalisation, and the need for IV therapy can be emotionally distressing for both children and caregivers. The economic burden from prolonged illness, diagnostic testing, and missed workdays further strains low-income families (9).

7. DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES: CURRENT PRACTICES AND MOLECULAR ADVANCES

Accurate and timely diagnosis of ESBL-producing UTIs in children is critical for guiding therapy and avoiding complications. However, in resource-constrained environments like Nigeria, challenges such as infrastructure deficits, delayed cultural results, and reliance on empirical therapy persist (36).

7.1. Traditional Diagnostic Methods

Standard UTI diagnosis includes urinalysis, urine culture, and AST (antimicrobial susceptibility testing). Urinalysis provides a quick screening, but urine culture is the definitive method for identifying the causative pathogen and its susceptibility profile (73). ESBL production is detected using phenotypic methods like double-disk synergy tests (DDST) and combination disk methods (CDM) (74). These methods rely on demonstrating synergy between cephalosporins and clavulanic acid.

7.2. Limitations of Phenotypic Testing

Phenotypic tests, although accessible, can take 48–72 hours, delaying treatment. They may miss low-level resistance or misclassify isolates with overlapping resistance mechanisms, such as AmpC β-lactamase producers (75).

7.3. Molecular Diagnostics

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) enables rapid and specific detection of ESBL genes such as blaCTX-M, blaSHV, and blaTEM (48). Multiplex PCR allows simultaneous detection of multiple genes, improving diagnostic efficiency (76). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is emerging as a practical option in LMICs due to its low cost and simplicity (77).

7.4. Advanced Genomic Tools

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) enables comprehensive surveillance by mapping resistance genes, virulence factors, and clonal relationships (60). Despite its diagnostic power, WGS remains largely limited to research settings in LMICs due to cost and technical capacity barriers (44).

7.5. Diagnostic Challenges in Pediatric Populations

Urine sample collection in children is complicated by contamination with bag samples or discomfort with catheterization. Accurate collection methods such as suprapubic aspiration are rarely used due to invasiveness (1). Misleading or delayed results contribute to empirical treatment failures.

7.6. The Role of Rapid Point-of-Care Testing (POCT)

POCT platforms integrating PCR or isothermal amplification could offer real-time detection of resistance genes. These tools are especially useful in pediatric settings but are still in early deployment stages in most LMICs (78).

7.7. Recommendations for Diagnostic Improvement

To improve diagnostics and treatment of pediatric UTIs, especially in high-burden settings like Nigeria, the following are recommended:

Strengthening laboratory infrastructure and personnel training.

Incorporating PCR-based diagnostics in tertiary hospitals.

Developing cost-effective POCT for pediatric care.

Encouraging public-private partnerships to scale diagnostic tools.

A combination of improved phenotypic methods and expanded access to molecular diagnostics is essential for accurate detection of ESBL-producing organisms in pediatric UTIs. Such integration will improve treatment outcomes and enhance antimicrobial stewardship.

8. ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE PATTERNS AND TREATMENT IMPLICATIONS

Understanding the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles of ESBL-producing uropathogens in pediatric patients is essential for guiding empiric therapy and shaping public health responses. The presence of ESBL genes not only renders many beta-lactam antibiotics ineffective but is often associated with multidrug resistance (MDR) to other critical antibiotic classes such as fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25, 75, 79).

8.1. Resistance to Beta-Lactam Antibiotics

The hallmark of ESBL-producing pathogens is their resistance to penicillins, third-generation cephalosporins, and monobactams like aztreonam. Clinical studies in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria, show resistance rates exceeding 80% to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftazidime in pediatric UTI isolates (22, 36). These resistance levels result in frequent empirical treatment failures, especially in settings lacking microbiological diagnostics.

8.2. Cross-Resistance and Multidrug Resistance (MDR)

Most ESBL producers carry additional resistance mechanisms—such as efflux pumps and aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes—resulting in MDR phenotypes (56).

8.3. Retained Susceptibility and Alternative Options

Despite the broad resistance, some agents retain efficacy. Nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin show high susceptibility (>85%) in pediatric UTIs caused by ESBL producers (80, 81). These are especially valuable for uncomplicated cystitis, though nitrofurantoin is not effective in pyelonephritis. Carbapenems like meropenem remain the cornerstone for severe infections, though their use is limited by cost, IV-only administration, and rising resistance (82). Piperacillin-tazobactam may still be effective in some ESBL contexts, though its success is variable in high-inoculum infections (25).

8.4. Empirical Therapy Considerations

In the absence of rapid diagnostics, empirical treatment is often based on regional antibiograms. In countries like Nigeria, where oral antibiotic resistance is rampant, empirical regimens should be reconsidered. Pediatric patients with recent hospitalization, prior antibiotic exposure, or recurrent UTIs are at higher risk for ESBL infections and may require broader-spectrum empiric therapy (63).

8.5. Treatment Challenges in LMICs

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), effective treatment is hindered by:

Limited access to effective antibiotics such as carbapenems and fosfomycin.

Lack of pediatric formulations for many antibiotics (70).

Financial barriers lead to incomplete treatments.

Poor adherence to protocols due to training gaps and lack of updated guidelines (32, 83).

8.6. Role of Pharmacovigilance and Resistance Monitoring

Addressing these challenges requires national AMR surveillance programs and integration of ESBL detection in AST protocols. Routine pediatric antibiogram dissemination and participation in global AMR initiatives will improve decision-making (43). Ongoing pharmacovigilance and updated treatment guidelines can reduce inappropriate antibiotic use and help preserve remaining therapeutic options (84).

9. PUBLIC HEALTH AND STEWARDSHIP IMPLICATIONS

The increasing prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing uropathogens in pediatric populations has profound public health consequences, particularly in resource-limited settings (25). These organisms, often resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics, compromise standard therapeutic regimens and threaten the effectiveness of empirical treatment protocols (43). The implications extend beyond individual patient care to broader systemic challenges in infection control, healthcare resource allocation, and antimicrobial policy.

9.1. Strain on Health Systems

ESBL-related pediatric UTIs frequently result in prolonged illness, increased hospitalization rates, and the need for more expensive second-line or intravenous antibiotics such as carbapenems (81). This puts additional pressure on already strained healthcare infrastructures in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to advanced diagnostics and newer antibiotics is limited (85). In some settings, recurrent infections in children may also lead to long-term health consequences such as renal scarring, chronic kidney disease, or hypertension, which require sustained follow-up and specialist care (86).

9.2. Implications for Infection Control and Hospital Policy

Hospital-acquired infections with ESBL-producing organisms are increasingly reported in neonatal and pediatric wards (87). The high transmissibility of ESBL genes, especially via plasmid-mediated horizontal gene transfer, makes rigorous infection control protocols essential. However, many facilities in LMICs lack adequate isolation measures, hand hygiene enforcement, or staff training programs (43). Surveillance programs should be strengthened, with mandatory reporting of ESBL infections and routine screening in high-risk wards.

9.3. Antibiotic Stewardship in Pediatric Care

The cornerstone of curbing resistance lies in rational antibiotic use (88). Pediatric antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) should be implemented in both primary and tertiary healthcare settings. These programs must include:

Development and dissemination of pediatric-specific treatment guidelines.

Regular audit and feedback mechanisms for antibiotic prescriptions.

Engagement of paediatricians, pharmacists, and microbiologists in multidisciplinary stewardship teams.

Training programs for junior clinicians on the principles of prudent antibiotic use.

Pharmacovigilance is equally essential. Clinicians should be encouraged to use narrow-spectrum agents guided by antibiogram data wherever possible. In resource-limited settings, access to updated regional resistance profiles can greatly enhance the precision of empirical therapy (89).

9.4. Role of Pharmacists and Community Engagement

Pharmacists play a pivotal role in antibiotic dispensing and caregiver education. Unfortunately, in many LMICs, antibiotics are frequently sold without prescriptions (90). Community pharmacists should be integrated into national stewardship frameworks and trained to educate caregivers about the dangers of antibiotic misuse.

Public education campaigns targeting parents, schools, and community leaders are vital. These should address:

When and why antibiotics are necessary (and when they are not).

Risks of self-medication and incomplete courses.

Recognition of early UTI symptoms and importance of clinical evaluation.

9.5. Policy and Regulatory Measures

Governments and health ministries must enact and enforce regulations that restrict over-the-counter sales of antibiotics (43). Policy frameworks should also incentivize research and development of pediatric formulations of essential antibiotics. National action plans on antimicrobial resistance must prioritize:

Expansion of diagnostic laboratories capable of detecting ESBL-producing strains.

Investment in electronic medical records and surveillance systems.

Inclusion of pediatric resistance data in national AMR reports.

9.6. International and Multisectoral Collaboration

Global health agencies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), must continue to support LMICs in developing antimicrobial stewardship infrastructure. Cross-border surveillance networks and international research collaborations can facilitate data sharing and harmonization of guidelines (43).

Figure 3.

Conceptual illustration of antimicrobial stewardship, highlighting the critical balance between effective treatment of infections and the prevention of antibiotic resistance.

Figure 3.

Conceptual illustration of antimicrobial stewardship, highlighting the critical balance between effective treatment of infections and the prevention of antibiotic resistance.

10. FUTURE DIRECTION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Ultimately, addressing the spread of ESBL-producing uropathogens in children requires a comprehensive and coordinated response. This includes strengthening clinical practices, enforcing policy controls, empowering healthcare workers, and educating the public. Without urgent and sustained intervention, the effectiveness of available antibiotics will continue to wane, putting millions of children at risk of preventable complications from common infections.

10.1. Revision of Empirical Treatment Protocols

Based on the high resistance rates recently being observed, it is recommended that healthcare practitioners consider the use of nitrofurantoin and cephalexin as first-line treatments for pediatric UTIs, as these have shown lower resistance levels in several studies. Regular updates to treatment guidelines should be based on continuous surveillance of local antimicrobial resistance patterns.

10.2. Strengthening Antibiotic Stewardship Programs

There is a critical need to establish and enforce antibiotic stewardship programs to curb the misuse of antibiotics in the community. This includes training healthcare providers on the judicious use of antibiotics and promoting the adoption of guidelines that restrict the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Antibiotic stewardship programs must be strengthened to prevent the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, which contribute to the emergence of resistance. Strategies such as de-escalation of therapy, shorter treatment durations, and the use of targeted antibiotics based on susceptibility profiles are critical in reducing the selective pressure that drives resistance. Finally, the development of new antibiotics and alternative therapies, such as bacteriophage therapy and antimicrobial peptides, should be prioritised to address the growing threat of multidrug-resistant pathogens.

10.3. Implementation of Routine Diagnostic Testing

Routine urine culture and sensitivity testing should be encouraged, especially in cases of recurrent UTIs or treatment failures. This approach will enable more precise targeting of antibiotics, thereby reducing the risk of resistance development.

10.4. Public Health Education Campaigns

Educational initiatives aimed at informing the public about the importance of completing prescribed antibiotic courses and the risks associated with self-medication are essential. Increasing awareness can help reduce the incidence of antimicrobial resistance in the community.

10.5. Enhanced Surveillance and Research

Continued surveillance of antimicrobial resistance patterns and the genetic mechanisms underlying resistance is crucial. Future research should focus on expanding the molecular characterisation of resistant pathogens to guide the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

11. CONCLUSIONS

The escalating prevalence of ESBL-producing uropathogens in pediatric populations underscores a growing threat to global child health. The clinical challenges associated with diagnosis, limited therapeutic options, and poor outcomes demand urgent action. Strengthening diagnostic capacity, promoting rational antibiotic use, enforcing rigorous infection control measures, and prioritising research on novel therapeutics are essential pillars to combat this evolving crisis. Global collaboration is essential to advance these research agendas and safeguard pediatric health. A coordinated One Health approach, integrating human, animal, and environmental health perspectives, offers the most promising pathway to mitigate the spread of antimicrobial resistance and protect vulnerable pediatric populations.

References

- Shaikh, N., Morone, N. E., Bost, J. E. and Farrell, M. H.(2008). Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 27(4):302–308.

- Masika, W. G., O’Meara, W. P., Holland, T. L. and Armstrong, J. (2017). Contribution of urinary tract infection to the burden of febrile illnesses in young children in rural Kenya. PLOS ONE 12(3): e0174199. [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, M. G., Lambert, H. J., Vernon, S. J., Hunter, E. W., Keir, M. J., & Matthews, J. N. (2014). Does prompt treatment of urinary tract infection in preschool children prevent renal scarring: mixed retrospective and prospective audits. Archives of disease in childhood, 99(4), 342–347. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, N., Hoberman, A., Keren, R., Gotman, N., Docimo, S. G., Mathews, R., Bhatnagar, S., Ivanova, A., Mattoo, T. K., Moxey-Mims, M., Carpenter, M. A., Pohl, H. G., & Greenfield, S. (2016). Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Children With Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction. Pediatrics, 137(1), e20152982. [CrossRef]

- Ekpunobi, N. F., Mgbedo, U. G., Okoye, L. C. and Agu, K. C. (2024). Prevalence of ESBL genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae from individuals with community-acquired urinary tract infections in Lagos state, Nigeria. Journl of RNA and Genomics, 20 (2):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Ekpunobi, N., Adesanoye, S., Orababa, O., Adinnu, C., Okorie, C., Akinsuyi, O. (2024). Public health perspective of public abattoirs in Nigeria, challenges and solutions. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 26. 115-127. [CrossRef]

- Okoye, L. C., Ugwu, M. C., Oli, A. N., Okoye, E. C. S., Ekpunobi, N. F., Okezie, U. M. and Mgbedo, U. G. (2024). Genotypic detection of metallo-Beta-Lactamases among multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from urine samples of UTI patients GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 29(03), 248-255. [CrossRef]

- Chukwunwejim, C.R., Ekpunobi, N.F., Ogunmola, T., Obidi, N., Ajasa, O. S. and Obidi, N. L. (2025). Molecular identification of multidrug-resistant bacteria from eggshell surfaces in Nigeria: A growing threat to public health. Magna Scientia Advanced Biology and Pharmacy, 2025, 15(01), 021-028. [CrossRef]

- Bryce, A., Hay, A. D., Lane, I. F., Thornton, H. V., Wootton, M., & Costelloe, C. (2016). Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in paediatric urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli and association with routine use of antibiotics in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 352, i939. [CrossRef]

- Obidi, N.O. and Ekpunobi, N. F. (2025). A narrative review exploring phage therapy as a sustainable alternative solution to combat antimicrobial resistance in Africa: Applications, challenges, and future directions. Afr. J. Clin. Exper. Microbiol. 26 (2): 106-113.

- Ekpunobi, N. F. and Agu, K.C. (2024). Emergence and Re-Emergence of Arboviruses: When Old Enemies Rise Again. Cohesive J Microbiol Infect Dis. 7(2). CJMI. 000658. [CrossRef]

- Chakupurakal, R., Ahmed, M., Sobithadevi, D. N., Chinnappan, S., & Reynolds, T. (2010). Urinary tract pathogens and resistance pattern. Journal of clinical pathology, 63(7), 652–654. [CrossRef]

- Murray, T.S. and Peaper, D.R. (2015) The Contribution of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases to Multidrug-Resistant Infections in Children. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 27, 124-131. [CrossRef]

- Lukac, P. J., Bonomo, R. A., & Logan, L. K. (2015). Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in children: old foe, emerging threat. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 60(9), 1389–1397. [CrossRef]

- Edlin, R. S., Shapiro, D. J., Hersh, A. L., & Copp, H. L. (2013). Antibiotic resistance patterns of outpatient pediatric urinary tract infections. The Journal of urology, 190(1), 222–227. [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, N. P., Maharjan, P., Parajuli, H., Joshi, G., Paudel, D., Sayami, S., & Khanal, P. R. (2017). High rates of multidrug resistance among uropathogenic Escherichia coli in children and analyses of ESBL producers from Nepal. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control, 6, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I. C. D. S., Menezes, R. P., Jesus, T. A., Lopes, M. S. M., Araújo, L. B., Ferreira, D. M. L. M., & Röder, D. V. D. B. (2024). Unraveling the epidemiology of urinary tract infections in neonates: Perspective from a Brazilian NICU. American journal of infection control, 52(8), 925–933. [CrossRef]

- Reuland, E. A., Sonder, G. J., Stolte, I., Al Naiemi, N., Koek, A., Linde, G. B., van de Laar, T. J., Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C. M., & van Dam, A. P. (2016). Travel to Asia and traveller's diarrhoea with antibiotic treatment are independent risk factors for acquiring ciprofloxacin-resistant and extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae-a prospective cohort study. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 22(8), 731.e1–731.e7317. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). (2020). Antimicrobial resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net) – Annual epidemiological report for 2019. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-antimicrobial-resistance-europe-2019.

- Peirano, G., & Pitout, J. D. (2019). Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: update on molecular epidemiology and treatment options. Drugs, 79, 1529-1541.

- Laxminarayan, R., Duse, A., Wattal, C., Zaidi, A. K., Wertheim, H. F., Sumpradit, N., Vlieghe, E., Hara, G. L., Gould, I. M., Goossens, H., Greko, C., So, A. D., Bigdeli, M., Tomson, G., Woodhouse, W., Ombaka, E., Peralta, A. Q., Qamar, F. N., Mir, F., Kariuki, S., … Cars, O. (2013). Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 13(12), 1057–1098. [CrossRef]

- Aibinu I, Odugbemi T, Koenig W, Ghebremedhin B. Sequence Type ST131 and ST10 Complex (ST617) predominant among CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Nigeria Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E49–51.

- Maina, D., Makau, P., Nyerere, A. and Revathi, G. (2013) Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns in Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in a Private Tertiary Hospital, Kenya. Microbiology Discovery, 1, 5.

- Ouedraogo, A. S., Sanou, M., Kissou, A., Sanou, S., Solaré, H., Kaboré, F., Poda, A., Aberkane, S., Bouzinbi, N., Sano, I., Nacro, B., Sangaré, L., Carrière, C., Decré, D., Ouégraogo, R., Jean-Pierre, H., & Godreuil, S. (2016). High prevalence of extended-spectrum ß-lactamase producing enterobacteriaceae among clinical isolates in Burkina Faso. BMC infectious diseases, 16, 326. [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P. D., Avdic, E., Li, D. X., Dzintars, K., & Cosgrove, S. E. (2017). Association of Adverse Events With Antibiotic Use in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA internal medicine, 177(9), 1308–1315. [CrossRef]

- Pillonetto, M., Jordão, R. T. S., Andraus, G. S., Bergamo, R., Rocha, F. B., Onishi, M. C., de Almeida, B. M. M., Nogueira, K. D. S., Dal Lin, A., Dias, V. M. C. H., & de Abreu, A. L. (2021). The Experience of Implementing a National Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System in Brazil. Frontiers in public health, 8, 575536. [CrossRef]

- Pavez, M., Troncoso, C., Osses, I., Salazar, R., Illesca, V., Reydet, P., Rodríguez, C., Chahin, C., Concha, C., & Barrientos, L. (2019). High prevalence of CTX-M-1 group in ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae infection in intensive care units in southern Chile. The Brazilian journal of infectious diseases : an official publication of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases, 23(2), 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Woerther, P. L., Burdet, C., Chachaty, E., & Andremont, A. (2013). Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clinical microbiology reviews, 26(4), 744–758. [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A. (2013). Plasmids and the spread of resistance. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 303(6-7), 298–304.

- Van Boeckel, T. P., Brower, C., Gilbert, M., Grenfell, B. T., Levin, S. A., Robinson, T. P., Teillant, A., & Laxminarayan, R. (2015). Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(18), 5649-5654.

- O'Neill, J. (2016). Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. https://amr-review.org.

- Ayukekbong, J.A., Ntemgwa, M. and Atabe, A.N. (2017) The Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries: Causes and Control Strategies. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, 6, 47. [CrossRef]

- Ogbolu, D. O., Daini, O. A., Ogunledun, A., Alli, A. O., & Webber, M. A. (2011). High levels of multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Gram-negative pathogens from Nigeria. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 37(1), 62–66. [CrossRef]

- Adekanmbi, A. O., Akinlabi, O. C., Usidamen, S., Olaposi, A. V., & Olaniyan, A. B. (2022). High burden of ESBL- producing Klebsiella spp., Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter cloacae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in diagnosed cases of urinary tract infection in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Acta microbiologica et immunologica Hungarica, 69(2), 127–134. [CrossRef]

- Gulumbe, B.H. and Faggo, A.A. (2019). Epidemiology of Multidrug-resistant Organisms in Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Infection Microbes and Antimicrobials, 8(1), 25-25.

- Onanuga A, Eboh DD, Odetoyin B, Adamu OJ. (2020). Detection of ESBLs and NDM-1 genes among urinary Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae fromhealthy students in Niger delta University, Amassoma, Bayelsa State, Nigeria.PAMJ - One Heal. 2:12.

- Bello, R., Ibrahim, Y.K., Olayinka, B.O., Jimoh, G.A., Afolabi-Balogun, N., Oni-Babatunde, A.O., Olabode, H.O., David, M.S., Aliyu, A., & Olufadi-Ahmed, H.Y. (2021). Molecular Characterization of Extended Spectrum Beta – Lactamase Producing Escherichia Coli Isolated from Pregnant Women with Urinary Tract Infections Attending Ante–Natal Clinics in Ilorin Metropolis. Nigerian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research.

- Auta, A., Hadi, M. A., Oga, E., Adewuyi, E. O., Abdu-Aguye, S. N., Adeloye, D., Strickland-Hodge, B., & Morgan, D. J. (2019). Global access to antibiotics without prescription in community pharmacies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of infection, 78(1), 8–18. [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Caldes, C., Hernández-Alomía, F., Almeida, M., Ormaza, M., Boada, J., Graham, J., Calvopiña, M., & Castillejo, P. (2024). Molecular identification and antimicrobial resistance patterns of enterobacterales in community urinary tract infections among indigenous women in Ecuador: addressing microbiological misidentification. BMC infectious diseases, 24(1), 1195. [CrossRef]

- Fadare, J. O., Ogunleye, O., Iliyasu, G., Adeoti, A., Schellack, N., Engler, D., Massele, A., & Godman, B. (2019). Status of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Nigerian tertiary healthcare facilities: Findings and implications. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance, 17, 132–136. [CrossRef]

- Iregbu KC, Nwajiobi-Princewill PI, Medugu N, Umeokonkwo, C. D., Uwaezuoke, N. S., Peter, Y. J., Nwafia, I. N., Elikwu, C., 7Shettima, S. A., Suleiman, M. R., Awopeju, A. T. O., Udoh, U., Adedosu, N., Mohammed, A., Oshun, P., Ekuma, A., Manga, M. M., Osaigbovo, I. I., Ejembi, C. J., Akujobi, C. N., Samuel, S. O., Taiwo, S. S., and Oduyebo, O. O. (2021). Antimicrobial Stewardship Implementation in Nigerian Hospitals: Gaps and Challenges. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology.22(1):60-66.https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajcem/article/view/203077.

- Obiageli J.O., Uzoma I., Sanda U. I., Uzairue L. I., Emmanuel C. A. (2023). Systematic review of surveillance systems for AMR in Africa, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 78(1): 31–51, . [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027336.

- Olalekan, A., Onwugamba, F., Iwalokun, B., Mellmann, A., Becker, K., & Schaumburg, F. (2020). High proportion of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae among extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producers in Nigerian hospitals. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance, 21, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- Sampah J, Owusu-Frimpong I, Aboagye FT, Owusu-Ofori A (2023) Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a teaching hospital in Ghana. PLoS ONE 18(10): e0274156.

- Bush, K., & Bradford, P. A. (2020). Epidemiology of β-Lactamase-Producing Pathogens. Clinical microbiology reviews, 33(2), e00047-19. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D. L., & Bonomo, R. A. (2005). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clinical microbiology reviews, 18(4), 657–686. [CrossRef]

- Cantón, R., González-Alba, J. M., & Galán, J. C. (2012). CTX-M Enzymes: Origin and Diffusion. Frontiers in microbiology, 3, 110. [CrossRef]

- Bevan, E. R., Jones, A. M., & Hawkey, P. M. (2017). Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 72(8), 2145–2155. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet R. (2004). Growing group of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: the CTX-M enzymes. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 48(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bradford P. A. (2001). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clinical microbiology reviews, 14(4), 933–951. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, G. A., & Munoz-Price, L. S. (2005). The new beta-lactamases. The New England journal of medicine, 352(4), 380–391. [CrossRef]

- D'Andrea, M. M., Arena, F., Pallecchi, L., & Rossolini, G. M. (2013). CTX-M-type β-lactamases: a successful story of antibiotic resistance. International journal of medical microbiology : IJMM, 303(6-7), 305–317. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Baño, J., Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, B., Machuca, I., & Pascual, A. (2018). Treatment of Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-, AmpC-, and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clinical microbiology reviews, 31(2), e00079-17. [CrossRef]

- Coque, T. M., Novais, A., Carattoli, A., Poirel, L., Pitout, J., Peixe, L., Baquero, F., Cantón, R., & Nordmann, P. (2008). Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerging infectious diseases, 14(2), 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Mathers, A. J., Peirano, G., & Pitout, J. D. (2015). The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clinical microbiology reviews, 28(3), 565–591. [CrossRef]

- Duicu, C., Cozea, I., Delean, D., Aldea, A. A., & Aldea, C. (2021). Antibiotic resistance patterns of urinary tract pathogens in children from Central Romania. Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 22(1), 748. [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Chanoine, M. H., Bertrand, X., & Madec, J. Y. (2014). Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clinical microbiology reviews, 27(3), 543–574. [CrossRef]

- Tchesnokova, V., Radey, M., Chattopadhyay, S., Larson, L., Weaver, J. L., Kisiela, D., & Sokurenko, E. V. (2019). Pandemic fluoroquinolone resistant Escherichia coli clone ST1193 emerged via simultaneous homologous recombinations in 11 gene loci. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(29), 14740–14748. [CrossRef]

- Stoesser, N., Sheppard, A. E., Pankhurst, L., De Maio, N., Moore, C. E., Sebra, R., Turner, P., Anson, L. W., Kasarskis, A., Batty, E. M., Kos, V., Wilson, D. J., Phetsouvanh, R., Wyllie, D., Sokurenko, E., Manges, A. R., Johnson, T. J., Price, L. B., Peto, T. E., Johnson, J. R., … Modernizing Medical Microbiology Informatics Group (MMMIG) (2016). Evolutionary History of the Global Emergence of the Escherichia coli Epidemic Clone ST131. mBio, 7(2), e02162. [CrossRef]

- Enyi, E. O., Ekpunobi, N. F. (2022). Secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi of Moringa oleifera: antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Journal of Microbiology and Experimentation 10(5):150‒154. [CrossRef]

- Ekpunobi, N. F. and Adeleye, I. A. (2020). Phenotypic characterization of biofilm formation and efflux pump activity in multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus species isolated from asymptomatic students. Journal of Microbiology and Experimentation 8(6): 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Logan, L. K., Braykov, N. P., Weinstein, R. A., Laxminarayan, R., & CDC Epicenters Prevention Program (2014). Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing and Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Children: Trends in the United States, 1999-2011. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, 3(4), 320–328. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K., Cannings-John, R., Jones, H., Lugg-Widger, F., Lau, T. M. M., Paranjothy, S., Francis, N., Hay, A. D., Butler, C. C., Angel, L., Van der Voort, J., & Hood, K. (2024). Long-term consequences of urinary tract infection in childhood: an electronic population-based cohort study in Welsh primary and secondary care. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 74(743), e371–e378. [CrossRef]

- Afsharpaiman S, Bairaghdar F, Torkaman M, Kavehmanesh Z, Amirsalari S, Moradi M, Safavimirmahalleh MJ. Bacterial Pathogens and Resistance Patterns in Children With Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infection: A Cross Sectional Study. J Compr Ped. 2012;3(1):16- 20. [CrossRef]

- Habib S. (2012). Highlights for management of a child with a urinary tract infection. International journal of pediatrics, 2012, 943653. [CrossRef]

- Drekonja DM, Filice GA, Greer N, Olson A, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Wilt TJ. 2015. Antimicrobial stewardship in outpatient settings: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 36:142–152.

- Cardoso T, Almeida M, Friedman ND, Aragao I, Costa-Pereira A, Sarmento AE, et al. (2014) Classification of healthcare-associated infection: a systematic review 10 years after the first proposal. BMC Med. 12:40.

- Sencan, A., Carvas, F., Hekimoglu, I. C., Caf, N., Sencan, A., Chow, J., & Nguyen, H. T. (2014). Urinary tract infection and vesicoureteral reflux in children with mild antenatal hydronephrosis. Journal of pediatric urology, 10(6), 1008–1013. [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R., Duse, A., Wattal, C., Zaidi, A. K., Wertheim, H. F., Sumpradit, N., Vlieghe, E., Hara, G. L., Gould, I. M., Goossens, H., Greko, C., So, A. D., Bigdeli, M., Tomson, G., Woodhouse, W., Ombaka, E., Peralta, A. Q., Qamar, F. N., Mir, F., Kariuki, S., … Cars, O. (2013). Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 13(12), 1057–1098. [CrossRef]

- Woerther, P. L., Burdet, C., Chachaty, E., & Andremont, A. (2013). Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clinical microbiology reviews, 26(4), 744–758. [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A. P., Srinivasan, A., Carey, R. B., Carmeli, Y., Falagas, M. E., Giske, C. G., Harbarth, S., Hindler, J. F., Kahlmeter, G., Olsson-Liljequist, B., Paterson, D. L., Rice, L. B., Stelling, J., Struelens, M. J., Vatopoulos, A., Weber, J. T., & Monnet, D. L. (2012). Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 18(3), 268–281. [CrossRef]

- Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Roberts, K. B. (2011). Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics, 128(3), 595–610.

- CLSI. (2023). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

- Pitout, J. D., & Laupland, K. B. (2008). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 8(3), 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Giske, C. G., Sundsfjord, A. S., Kahlmeter, G., Woodford, N., Nordmann, P., Paterson, D. L., Cantón, R., & Walsh, T. R. (2009). Redefining extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: balancing science and clinical need. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 63(1), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T., Okayama, H., Masubuchi, H., Yonekawa, T., Watanabe, K., Amino, N., & Hase, T. (2000). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic acids research, 28(12), E63. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Liu, K., Li, Z., & Wang, P. (2019). Point of care testing for infectious diseases. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry, 493, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Sunmonu, A. and Ekpunobi, N. (2023). Larvicidal potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Ocimum gratissimum leaf extracts against anopheles' mosquito. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 25. 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Gajdács, M., Burián, K., & Terhes, G. (2019). Resistance Levels and Epidemiology of Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacteria in Urinary Tract Infections of Inpatients and Outpatients (RENFUTI): A 10-Year Epidemiological Snapshot. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland), 8(3), 143. [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D. M., & Woodford, N. (2006). The beta-lactamase threat in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. Trends in microbiology, 14(9), 413–420. [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, F. S., & Donkor, E. S. (2017). Carbapenem Resistance: A Review. Medical sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 6(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Ekpunobi, N., Markjonathan, I., Olanrewaju, O. and Olanihun, D. (2020). Idiosyncrasies of COVID- 19;A Review. Iranian Journal of Medical Microbiology 14(3): 290-296. [CrossRef]

- Gandra, S., Alvarez-Uria, G., Turner, P., Joshi, J., Limmathurotsakul, D., & van Doorn, H. R. (2020). Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Progress and Challenges in Eight South Asian and Southeast Asian Countries. Clinical microbiology reviews, 33(3), e00048-19. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A., Almubayedh, T., Alkhamis, I. H., AlMubayedh, A. A., Shuiel, H. K., Aldakail, M. (2025). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Saudi parents regarding antibiotic use for children: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 12(1): 20-29.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Urinary tract infection in under 16s: Diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg54.

- Nordmann, P., Naas, T., & Poirel, L. (2011). Global spread of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerging infectious diseases, 17(10), 1791–1798. [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A. L., Jackson, M. A., Hicks, L. A., & American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases (2013). Principles of judicious antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in pediatrics. Pediatrics, 132(6), 1146–1154. [CrossRef]

- Ventola C. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 40(4), 277–283.

- Ogunleye, O. O., Fadare, J. O., Yinka-Ogunleye, A. F., Anand Paramadhas, B. D., & Godman, B. (2019). Determinants of antibiotic prescribing among doctors in a Nigerian urban tertiary hospital. Hospital practice (1995), 47(1), 53–58. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).