Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Immunohistochemical Expression of MST1 in TETs

2.2. Immunohistochemical Expression of SAV1 in TETs

2.3. Immunohistochemical Expression of LATS1 in TETs

2.4. Immunohistochemical Expression of MOB1A in TETs

2.5. Immunohistochemical Expression of YAP1 in TETs

2.6. Immunohistochemical Expression of Active YAP (AYAP) in TETs

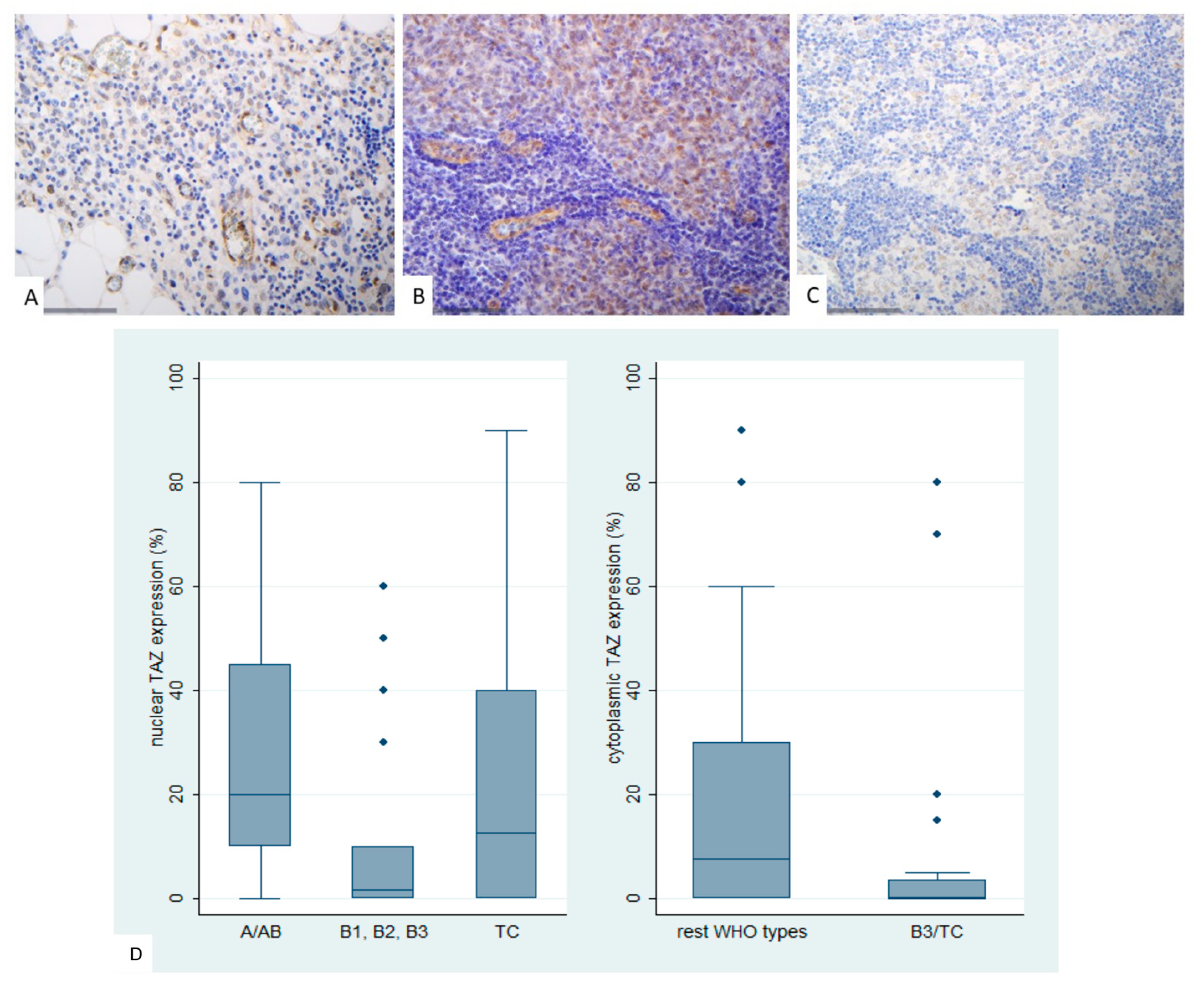

2.7. Immunohistochemical Expression of TAZ in TETs

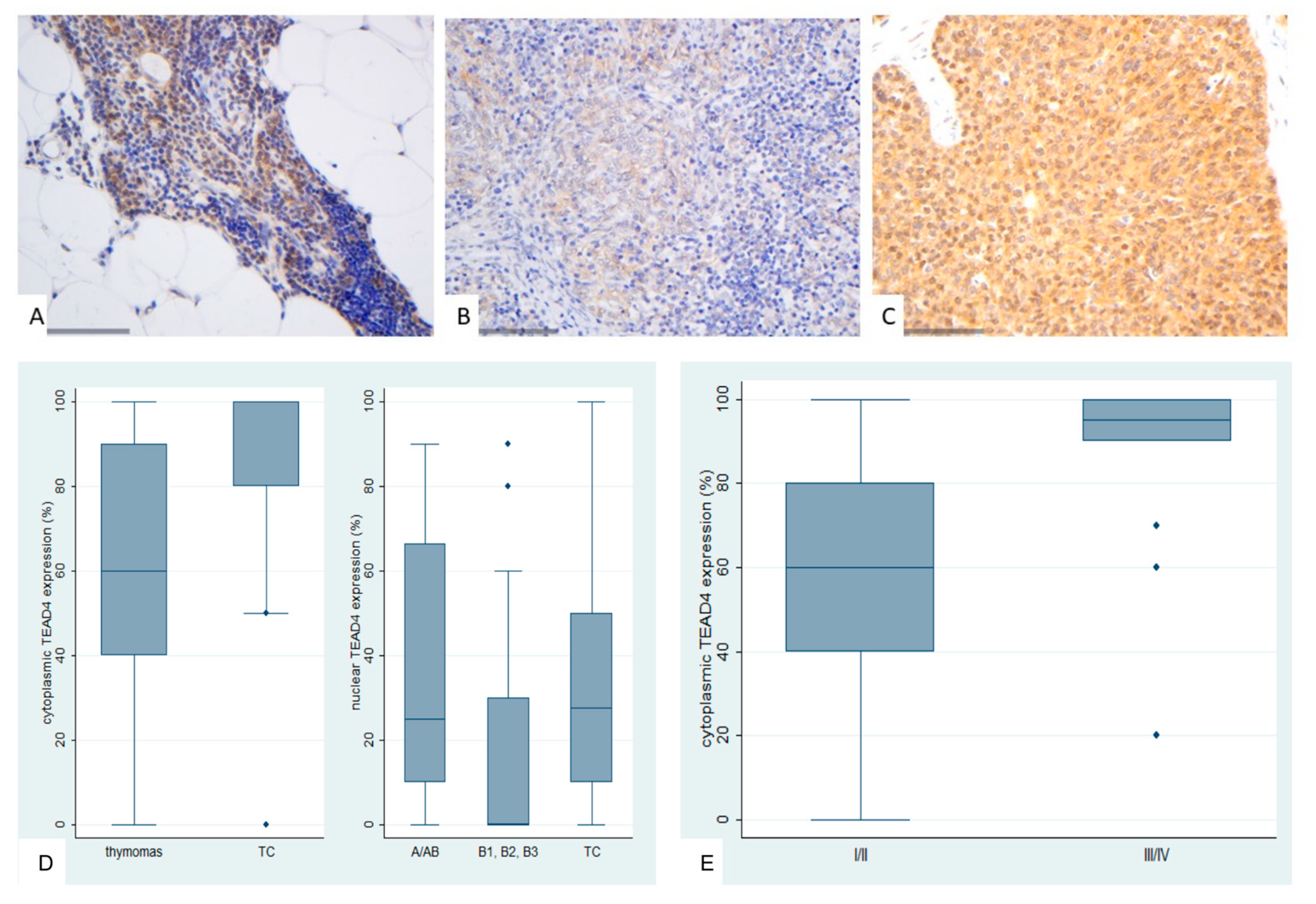

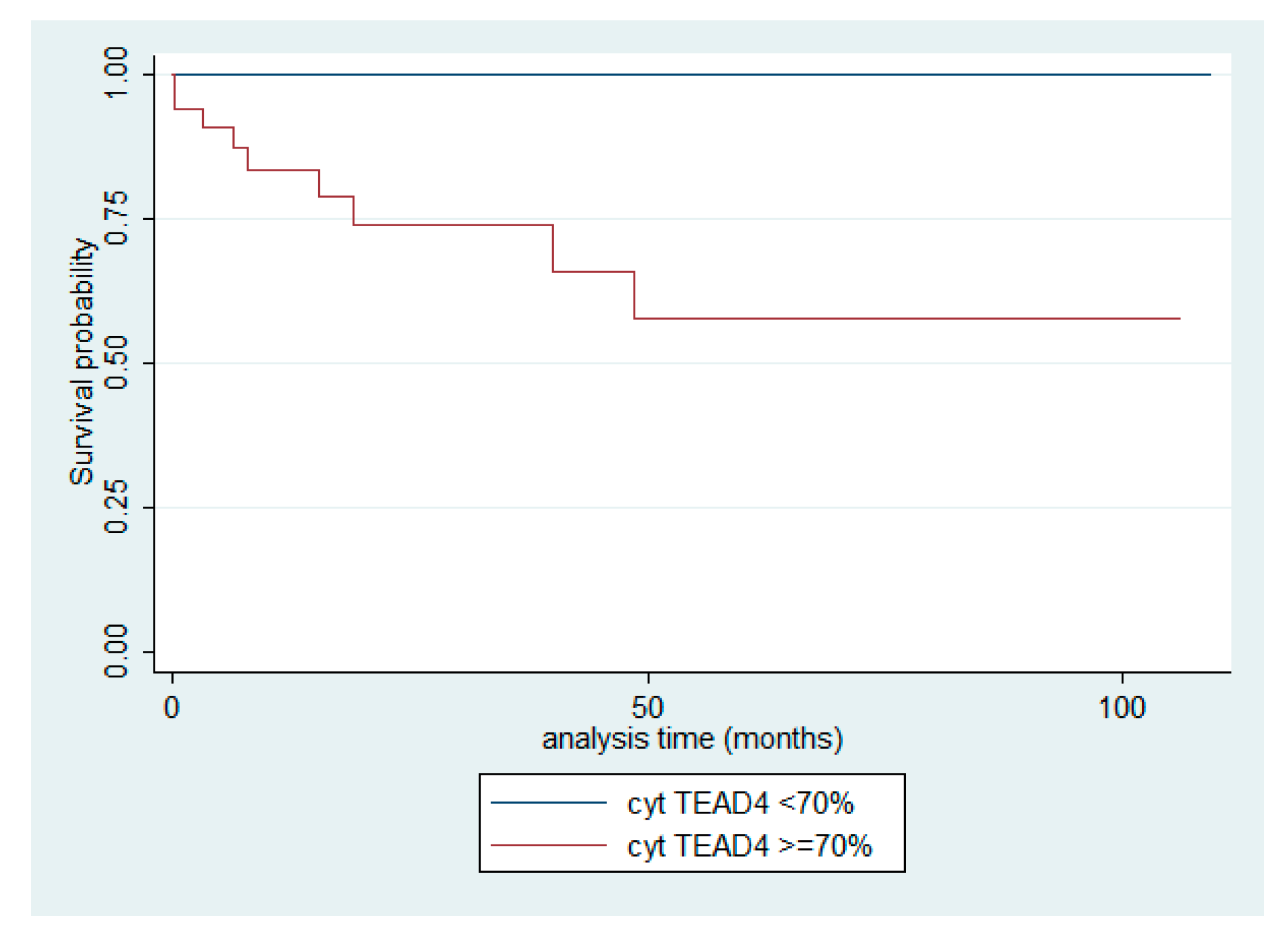

2.8. Immunohistochemical Expression of TEAD4 in TETs

2.9. Associations Between the Investigated Molecules of the Hippo Cascade

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Immunohistochemistry

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TET(s) | Thymic Epithelial Tumor(s) |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| TC | Thymic Carcinoma |

| MST1/2 | Mammalian STE20-like kinases |

| LATS1/2 | Large tumor suppressor kinases). |

| TAZ | Transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| MOB1(A) | Mps one binder 1(A) |

| SAV1 | Salvador homolog 1 |

| TEAD4 | TEA domain transcription factor 4 |

| AYAP | Active YAP1 |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OXPHOS | Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation |

| FFPE | Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

| WWTR1 | WW domain-containing transcription regulator 1 |

| MNT | Micronodular thymoma with lymphoid stroma |

| PMU | Paracelsus Medical University |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1: MST1

| Parameter | MST1 cytoplasmic expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = −0.08 | p = 0.465 |

| Tumor size | R = 0.18 | p = 0.152 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min–max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 15 (0–100) | p =0.370 |

| Female | 10 (1–95) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Thymomas | 10 (0–95) | p =0.014 |

| Thymic carcinomas (TC) | 70 (1–100) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 10 (0–95) | p =0.002 |

| III-IV | 45 (0–100) |

Appendix A.2: SAV1

| Parameter | SAV1 expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables |

<100% Median (min–max) |

100% Median (min–max) |

p-value* |

| Age (years) | 74 (45–88) | 67 (21–85) | p = 0.264 |

| Tumorsize (cm) | 4.5 (2.4–9) | 6, (0.9–14) | p = 0.237 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | |||

| <100% (n) | 100% (n) | p-value** | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 4 | 35 | p = 0.138 |

| Female | 9 | 29 | |

| WHO subtypes | |||

| Rest WHO types | 12 | 37 | p = 0.025 |

| B3/TC | 1 | 27 | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | |||

| I-II | 11 | 36 | p = 0.027 |

| III-IV | 0 | 18 | |

Appendix A.3: LATS1

| Parameter | LATS1 cytoplasmic expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = −0.08 | p = 0.788 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.07 | p = 0.566 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min–max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 90 (10–100) | p = 0.528 |

| Female | 90 (20–100) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Rest WHO types | 80 (10–100) | p < 0.001 |

| B3/TC | 100 (15–100) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 80 (20–100) | p = 0.007 |

| III-IV | 100 (40–100) |

Appendix A.4: MOB1A

| Parameter | MOB1A cytoplasmic expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = −0.01 | p = 0.879 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.10 | p = 0.389 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min–max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 100 (10–100) | p = 0.438 |

| Female | 100 (55–100) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Rest WHO types | 100 (55–100) | p = 0.063 |

| B3/TC | 100 (10–100) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 100 (55–100) | p = 0.033 |

| III-IV | 100 (10–100) |

Appendix A.5: YAP1

| Parameter | YAP1 nuclear expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.04 | p = 0.669 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.02 | p = 0.870 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min-max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 (0–95) | p = 0.506 |

| Female | 40 (0–90) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Thymomas | 50 (0–95) | p = 0.001 |

| TC | 5 (0–50) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 60 (0–95) | p = 0.023 |

| III-IV | 12.5 (0–95) | |

| Parameter | YAP1 cytoplasmic expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.12 | p = 0.273 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.18 | p = 0.144 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min-max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 20 (0–100) | p = 0.470 |

| Female | 10 (0–100) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Rest WHO types | 50 (0–95) | p = 0.740 |

| B3/TC | 5 (0–50) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I | 5 (0–80) | p = 0.032 |

| II-IV | 30 (0–100) | |

Appendix A.6: AYAP

| Parameter | AYAP nuclear expression | AYAP cytoplasmic expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.01 | p = 0.905 | R = 0.12 | p = 0.281 |

| Tumor size | R = 0.04 | p = 0.740 | R = −0.18 | p = 0.131 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||||

| Median (min-max) | p-value | Median (min-max) | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 50 (0–100) | p = 0.299* | 40 (0–100) | p = 0.384* |

| Female | 35 (0–90) | 17.5 (0–100) | ||

| WHO subtypes | ||||

| A/AB | 70 (20–100) | p = 0.001** | 60 (0–100) | p = 0.011** |

| B1, B2, B3 | 30 (0–95) | 10 (0–100) | ||

| TC | 5 (0–60) | 12.5 (0–80) | ||

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||||

| I-II | 60 (2–95) | p = 0.007* | 45 (0–100) | p = 0.947** |

| III-IV | 17.5 (0–100) | 45 (0–95) | ||

Appendix A.7: TAZ

| Parameter | TAZ nuclear expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.197 | p = 0.086 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.001 | p > 0.999 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min-max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 10 (0–90) | p = 0.872 |

| Female | 10 (0–70) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Thymomas A/AB | 20 (0–80) | p = 0.004 |

| B1, B2, B3 | 1.5 (0–60) | |

| TC | 12.5 (0–90) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 15 (0–70) | p = 0.182 |

| III-IV | 0 (0–80) | |

| Parameter | TAZ cytoplasmic expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.101 | p = 0.384 |

| Tumor size | R = 0.198 | p = 0.123 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min-max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 5 (0–90) | p = 0.298 |

| Female | 0 (0–80) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Rest WHO types | 7.5 (0–90) | p = 0.004 |

| B3/TC | 3.5 (0–80) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 5 (0–80) | p = 0.281 |

| III-IV | 0 (0–90) | |

Appendix A.8: TEAD4

| Parameter | TEAD4 cytoplasmic expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.25 | p = 0.027 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.11 | p = 0.348 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min-max) | p-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 80 (0–100) | p = 0.198 |

| Female | 60 (0–100) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Thymomas | 60 (0–100) | p = 0.002 |

| TC | 100 (0–100) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 60 (0–100) | p < 0.001 |

| III-IV | 95 (20–100) | |

| Parameter | TEAD4 nuclear expression | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical variables | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p-value |

| Age | R = 0.12 | p = 0.292 |

| Tumor size | R = −0.15 | p = 0.222 |

| Categorical/nominal variables | ||

| Median (min-max) | p-value | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 20 (0–90) | p = 0.545* |

| Female | 12.5 (0–100) | |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| A/AB | 25 (0–90) | p = 0.005** |

| B1, B2, B3 | 0 (0–90) | |

| TC | 27.5 (0–100) | |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I-II | 10 (0–90) | p = 0.957* |

| III-IV | 7.5 (0–90) | |

References

- Palamaris, K.; Levidou, G.; Kordali, K.; Masaoutis, C.; Rontogianni, D.; Theocharis, S. Searching for Novel Biomarkers in Thymic Epithelial Tumors: Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Hippo Pathway Components in a Cohort of Thymic Epithelial Tumors. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gameiro, J.; Nagib, P.; Verinaud, L. The thymus microenvironment in regulating thymocyte differentiation. Cell Adh Migr 2010, 4, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Gao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, B. Editorial: Revisiting the thymus: the origin of T cells. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, Editorial. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Lan, B.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Tian, J. Prognostic CT features in patients with untreated thymic epithelial tumors. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, A.; Fujimoto, K. Is there any consensus of long-term follow-up for incidental anterior mediastinal nodular lesions? Shanghai Chest 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraar, C.; Janik, S.; Thanner, J.; Veraar, C.; Mouhieddine, M.; Schiefer, A.-I.; Müllauer, L.; Dworschak, M.; Klepetko, W.; Ankersmit, H. J.; et al. Clinical prognostic scores for patients with thymic epithelial tumors. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 18581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, L.; Levidou, G. The Molecular Landscape of Thymic Epithelial Tumors: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, A.; Ströbel, P.; Badve, S. S.; Chalabreysse, L.; Chan, J. K.; Chen, G.; de Leval, L.; Detterbeck, F.; Girard, N.; Huang, J.; et al. ITMIG consensus statement on the use of the WHO histological classification of thymoma and thymic carcinoma: refined definitions, histological criteria, and reporting. J Thorac Oncol 2014, 9, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, N.; Johkoh, T.; Mihara, N.; Honda, O.; Kozuka, T.; Koyama, M.; Hamada, S.; Okumura, M.; Ohta, M.; Eimoto, T.; et al. Using the World Health Organization Classification of Thymic Epithelial Neoplasms to Describe CT Findings. American Journal of Roentgenology 2002, 179, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassi, V.; Vannucci, J.; Ceccarelli, S.; Gili, A.; Matricardi, A.; Avenia, N.; Puma, F. Stage-related outcome for thymic epithelial tumours. BMC Surg 2019, 18 (Suppl 1), 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. D.; Kim, H. R.; Choi, S. H.; Kim, Y. H.; Kim, D. K.; Park, S. I. Prognostic stratification of thymic epithelial tumors based on both Masaoka-Koga stage and WHO classification systems. J Thorac Dis 2016, 8, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Ke, X.; Man, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J. Predicting Masaoka-Koga Clinical Stage of Thymic Epithelial Tumors Using Preoperative Spectral Computed Tomography Imaging. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. Original Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Song, G. The Hippo Pathway: A Master Regulatory Network Important in Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, B. Regulation of the tumor immune microenvironment by the Hippo Pathway: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. International Immunopharmacology 2023, 122, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J. S.; Park, H. W.; Guan, K. L. The Hippo signaling pathway in stem cell biology and cancer. EMBO reports 2014, 15, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshe Oren, Y. A. The Hippo Signaling Pathway and Cancer Springer, 2013. 15, 642-656.

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.-L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, M. Hippo pathway in non-small cell lung cancer: mechanisms, potential targets, and biomarkers. Cancer Gene Therapy 2024, 31, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Mei, Z.; Liang, Z.; Cui, A.; Wu, T.; Liu, C. Y.; Cui, L. Increased TEAD4 expression and nuclear localization in colorectal cancer promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a YAP-independent manner. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Conrad, C.; Xia, F.; Park, J.-S.; Payer, B.; Yin, Y.; Lauwers, G. Y.; Thasler, W.; Lee, J. T.; Avruch, J.; et al. Mst1 and Mst2 Maintain Hepatocyte Quiescence and Suppress Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development through Inactivation of the Yap1 Oncogene. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Sun, P.-L.; Yao, M.; Jia, M.; Gao, H. Expression of YES-associated protein (YAP) and its clinical significance in breast cancer tissues. Human Pathology 2017, 68, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng J, R. P. , Gou J, Li Z. Prognostic significance of TAZ expression in various cancers: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2016, 9, 5235–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home, P.; Saha, B.; Ray, S.; Dutta, D.; Gunewardena, S.; Yoo, B.; Pal, A.; Vivian, J. L.; Larson, M.; Petroff, M.; et al. Altered subcellular localization of transcription factor TEAD4 regulates first mammalian cell lineage commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 7362–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, K. J.; DePamphilis, M. L. TEAD4 establishes the energy homeostasis essential for blastocoel formation. Development 2013, 140, 3680–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, B.; Fang, P. K.; Lutchman, M.; Di Vizio, D.; Adam, R. M.; Pavlova, N.; Rubin, M. A.; Yelick, P. C.; Freeman, M. R. The pro-apoptotic kinase Mst1 and its caspase cleavage products are direct inhibitors of Akt1. The EMBO Journal 2007, 26, 4523–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen M, H. B. , Zhu L, Chen K, Liu M, Zhong C. Structural and Functional Overview of TEAD4. Cancer Biology. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 9865–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Collins, C. C.; Chen, C.-L.; Kung, H.-J. TEAD4 as an Oncogene and a Mitochondrial Modulator. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 10, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yu, J.; Han, W.; Fan, X.; Qian, H.; Wei, H.; Tsai, Y.-h. S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; et al. A splicing isoform of TEAD4 attenuates the Hippo–YAP signalling to inhibit tumour proliferation. Nature Communications 2016, 7, ncomms11840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, H.; Jiao, F.; Li, N.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Quan, M. MST1 Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Progression via ROS-Induced Pyroptosis. Molecular Cancer Research 2019, 17, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhu, L.; Xiao, S.; Cui, Z.; Tang, J.; Yu, J.; Xie, M. MST1 inhibits the progression of breast cancer by regulating the Hippo signaling pathway and may serve as a prognostic biomarker. Mol Med Rep 2021, 23, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Mak, K. K.; Topol, L.; Yun, K.; Hu, J.; Garrett, L.; Chen, Y.; Park, O.; Chang, J.; Simpson, R. M.; et al. Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 1431–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, S. P.; von Nandelstadh, P.; Öhman, T.; Gucciardo, E.; Seashore-Ludlow, B.; Martins, B.; Rantanen, V.; Li, H.; Höpfner, K.; Östling, P.; et al. FGFR4 phosphorylates MST1 to confer breast cancer cells resistance to MST1/2-dependent apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2019, 26, 2577–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ura, S.; Masuyama, N.; Graves, J. D.; Gotoh, Y. Caspase cleavage of MST1 promotes nuclear translocation and chromatin condensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 10148–10153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K. H.; He, J.; Wang, D. L.; Cao, J. J.; Li, M. C.; Zhao, X. M.; Sheng, X.; Li, W. B.; Liu, W. J. Methylation-associated inactivation of LATS1 and its effect on demethylation or overexpression on YAP and cell biological function in human renal cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2014, 45, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, P. P.; Wang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, F.; Li, L.; Cui, J. J.; Wang, L. W. Expression profile and prognostic value of SAV1 in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 16207–16213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, N.; Tanaka, K.; Otsubo, K.; Toyokawa, G.; Ikematsu, Y.; Ide, M.; Yoneshima, Y.; Iwama, E.; Inoue, H.; Ijichi, K.; et al. Association of Mps one binder kinase activator 1 (MOB1) expression with poor disease-free survival in individuals with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2020, 11, 2830–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, W.; Nishio, M.; To, Y.; Togashi, H.; Mak, T. W.; Takada, H.; Ohga, S.; Maehama, T.; Suzuki, A. MOB1 regulates thymocyte egress and T-cell survival in mice in a YAP1-independent manner. Genes Cells 2019, 24, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Huang, Z.; Xu, C.; Seo, G.; An, J.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Lan, T.; Yan, J.; Ren, S.; et al. Functional annotation of the Hippo pathway somatic mutations in human cancers. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.; Hansen, Carsten G. The Hippo pathway in cancer: YAP/TAZ and TEAD as therapeutic targets in cancer. Clinical Science 2022, 136, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Lin, J.; Hu, C. Hippo/TEAD4 signaling pathway as a potential target for the treatment of breast cancer. Oncol Lett 2021, 21, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Liu, J.; Mei, C.; Shi, Y.; Liu, N.; Jiang, X.; Liu, C.; Xue, N.; Hong, H.; Xie, J.; et al. TEAD4 functions as a prognostic biomarker and triggers EMT via PI3K/AKT pathway in bladder cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022, 41, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Tang, P.; Cai, J.; Cao, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shen, B. TEAD4 as a Prognostic Marker Promotes Cell Migration and Invasion of Urinary Bladder Cancer via EMT. Onco Targets Ther 2021, 14, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M. A.; Lee, Y. H.; Gu, M. J. High TEAD4 Expression is Associated With Aggressive Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, Regardless of YAP1 Expression. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2023, 31, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Li, N.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Xie, H. A Four-Gene Prognostic Signature Based on the TEAD4 Differential Expression Predicts Overall Survival and Immune Microenvironment Estimation in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13. Original Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yi, R.; Wu, Z.; Lin, J.; Song, Y. Overexpression of TEAD4 correlates with poor prognosis of glioma and promotes cell invasion. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2018, 11, 4827–4835. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, T.; Mazack, V.; Sudol, M. Mst2 and Lats Kinases Regulate Apoptotic Function of Yes Kinase-associated Protein (YAP)*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 27534–27546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Maglic, D.; Dill, M. T.; Mojumdar, K.; Ng, P. K.; Jeong, K. J.; Tsang, Y. H.; Moreno, D.; Bhavana, V. H.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of the Hippo Signaling Pathway in Cancer. Cell Rep 2018, 25, 1304–1317.e1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H. L.; de Castro Brás, L. E.; Brunt, K. R.; Sylvester, M. A.; Parvatiyar, M. S.; Sirish, P.; Bansal, S. S.; Sule, R.; Eadie, A. L.; Knepper, M. A.; et al. Guidelines on antibody use in physiology research. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2024, 326, F511–f533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, C. E.; Tumes, D. J.; Liston, A.; Burton, O. T. Do more with Less: Improving High Parameter Cytometry Through Overnight Staining. Curr Protoc 2022, 2, e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, R.; Akman, H. B.; Tuncer, T.; Erson-Bensan, A. E.; Lindon, C. Differential translation of mRNA isoforms underlies oncogenic activation of cell cycle kinase Aurora A. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Cao, C.; Kumar, M.; Sinha, S.; Chanda, A.; McNeil, R.; Samuel, D.; Arora, R. K.; Matthews, T. W.; Chandarana, S.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct and conserved tumor core and edge architectures that predict survival and targeted therapy response. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.-y.; Wang, H.-q.; Lin, P.; Yuan, J.; Tang, Z.-x.; Li, H. Quantifying and interpreting biologically meaningful spatial signatures within tumor microenvironments. npj Precision Oncology 2025, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borreguero-Muñoz, N.; Fletcher, G. C.; Aguilar-Aragon, M.; Elbediwy, A.; Vincent-Mistiaen, Z. I.; Thompson, B. J. The Hippo pathway integrates PI3K-Akt signals with mechanical and polarity cues to control tissue growth. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyanaga, A.; Masuda, M.; Tsuta, K.; Kawasaki, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Sakuma, T.; Asamura, H.; Gemma, A.; Yamada, T. Hippo Pathway Gene Mutations in Malignant Mesothelioma: Revealed by RNA and Targeted Exon Sequencing. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2015, 10, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, M.; Bareke, E.; Nadaf, J.; Alirezaie, N.; Majewski, J. Whole-exome sequencing as a diagnostic tool: Current challenges and future opportunities. Expert review of molecular diagnostics 2015, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, V.; Vashisht, A.; Mondal, A. K.; Woodall, J.; Kolhe, R. From Genomic Exploration to Personalized Treatment: Next-Generation Sequencing in Oncology. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 12527–12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, Z.; Chen, X.; Pan, B.; Fang, B.; Yang, W.; Qian, Y. Pharmacological regulators of Hippo pathway: Advances and challenges of drug development. The FASEB Journal 2025, 39, e70438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, L.E. Deciphering Molecular Alterations of the Hippo Signaling Pathway in Thymic Epithelial Tumors Using Immunohistochemistry. Proceedings of the 3rd International Electronic Conference on Biomedicines (ECB 2025), Online, 12–15 May 2025; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland.

| n- MST1 | c-MST1 | c-SAV1 | c-LATS1 | c-MOB1A | n-TAZ | c-TAZ | n-YAP1 | c-YAP1 | n-AYAP | c-AYAP | n-TEAD4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-MST1 | R = −0.19 p = 0.095 |

|||||||||||

| c-SAV1 | R = 0.048 p = 0.68 |

R = 0.19 p = 0.096 |

||||||||||

| c-LATS1 | R = −0.14 p = 0.206 |

R = 0.45* p < 0.001 |

R = 0.33* p = 0.003 |

|||||||||

| c-MOB1A | R = 0.09 p = 0.441 |

R = 0.24 p = 0.032 |

R = 0.05 p = 0.624 |

R = 0.34 p = 0.002 |

||||||||

| n-TAZ | R = 0.12 p = 0.275 |

R = −0.08 p = 0.459 |

R = −0.10 p = 0.366 |

R = 0.25 p = 0.025 |

R = 0.02 p = 0.814 |

|||||||

| c-TAZ | R = 0.13 p = 0.246 |

R = 0.24 p = 0.038 |

R = 0.01 p = 0.919 |

R = 0.22 p = 0.056 |

R = 0.23 p = 0.042 |

R = 0.19 p = 0.097 |

||||||

| n-YAP1 | R = −0.02 p = 0.816 |

R = −0.21 p = 0.070 |

R = −0.21 p = 0.064 |

R = −0.05 p = 0.631 |

R = 0.04 p = 0.729 |

R = 0.30 p = 0.007 |

R = 0.32 p = 0.004 |

|||||

| c-YAP1 | R = −0.13 p = 0.244 |

R = 0.11 p = 0.340 |

R = −0.02 p = 0.857 |

R = 0.35 p = 0.001 |

R = 0.23 p = 0.044 |

R = 0.13 p = 0.239 |

R = 0.27 p = 0.016 |

R = 0.36 p = 0.001 |

||||

| n-AYAP | R = 0.16 p = 0.16 |

R = −0.20 p = 0.07 |

R = −0.20 p = 0.080 |

R = −0.02 p = 0.826 |

R = 0.05 p = 0.653 |

R = 0.37 p = 0.001 |

R = 0.44 p < 0.001 |

R = 0.80 p < 0.001 |

R = 0.30 p = 0.009 |

|||

| C-AYAP | R = 0.08 p = 0.497 |

R = −0.01 p = 0.872 |

R = −0.03 p = 0.788 |

R = 0.29 p = 0.010 |

R = 0.29 p = 0.009 |

R = 0.28 p = 0.013 |

R = 0.23 p = 0.047 |

R = 0.45 p < 0.001 |

R = 0.68 p < 0.001 |

R = 0.58 p < 0.001 |

||

| n-TEAD4 | R = −0.01 p = 0.867 |

R = 0.13 p = 0.265 |

R = −0.01 p = 0.892 |

R = 0.36 p = 0.001 |

R = 0.01 p = 0.940 |

R = 0.34 p = 0.002 |

R = 0.06 p = 0.600 |

R = 0.07 p = 0.526 |

R = 0.24 p = 0.038 |

R = 0.07 p = 0.519 |

R = 0.13 p = 0.245 |

|

| c-TEAD4 | R = 0.08 p = 0.468 |

R = 0.31 p = 0.005 |

R = 0.13 p = 0.265 |

R = 0.62 p < 0.001 |

R = 0.29 p = 0.012 |

R = 0.25 p = 0.029 |

R = 0.11 p = 0.318 |

R = −0.04 p = 0.706 |

R = 0.27 p = 0.017 |

R = −0.07 p = 0.523 |

R = 0.24 p = 0.031 |

R = 0.31 p = 0.007 |

| Parameter | Median | Min–max |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 | 21–88 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 6.5 | 0.9–14 |

| Number | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 39 | 50.6 |

| Female | 38 | 49.4 |

| WHO subtypes | ||

| Type A | 3 | 3.9 |

| Type AB | 26 | 33.7 |

| Type B1 | 7 | 9 |

| Type B2 | 11 | 14.3 |

| Type B3 | 14 | 18.2 |

| Micronodular with lymphoid stroma (MNT) | 2 | 2.6 |

| Thymic carcinoma (TC) | 14 | 18.2 |

| Masaoka–Koga stage | ||

| I | 22 | 33.8 |

| II | 25 | 38.5 |

| III | 9 | 13.8 |

| IVa | 5 | 7.7 |

| IVb | 4 | 6.1 |

| Presence of myasthenia Gravis | 11 | 14.1 |

| Event | ||

| Cencored-Alive | 51/60, follow-up 0.3–109, 4 months | 85 |

| Dead | 9/60, within 0.1–48.6 months | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).