1. Introduction

As global demand for renewable energy continues to grow, wind power has become a pivotal contributor to achieving sustainability goals. Policies such as the Green New Deal and the 2050 Carbon Neutrality Policy have positioned wind energy as a cornerstone of the hydrogen economy [

1]. Wind turbines, particularly their blades, play a vital role in converting wind energy into electricity. However, the increasing deployment of wind turbines has raised significant concerns about end-of-life management for their blades. Typically made of thermosetting resin-based composite materials, wind turbine blades offer high strength and durability but suffer from limited recyclability due to their irreversible crosslinked structure [

2]. Once a blade reaches the end of its 20–25 year lifespan, physical degradation or irreparable damage necessitates disposal. Traditionally, disposal methods have included landfill burial and incineration [

3]. These methods not only conflict with global carbon neutrality goals but also pose substantial environmental risks. For example, blades in landfills take hundreds of years to decompose, releasing harmful greenhouse gases like methane [

4]. While incineration recovers some energy, it produces toxic gases and ash, further exacerbating pollution [

5]. By 2050, the global accumulation of blade waste is projected to reach 43 million tons, with 40% generated in China, 25% in Europe, 16% in the United States, and the remaining 19% distributed worldwide [

6]. This escalating waste problem highlights the urgent need for alternative solutions, including the development of recyclable materials, advancements in blade design to extend lifespans, and comprehensive lifecycle management policies. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensuring the long-term sustainability of wind energy as a central pillar of the global renewable energy transition [

7].

The growing demand for wind energy has driven the need for advanced manufacturing technologies capable of producing efficient, scalable, and sustainable turbine blades. Among these, resin infusion, originally developed for industries such as wind energy and shipbuilding, has become a widely utilized method for fabricating composite structures. Recent advancements have further highlighted its significance in addressing the challenges of modern wind turbine blade manufacturing. This technique provides distinct advantages that align with the requirements for lightweight yet high-strength composite materials, optimizing energy generation while reducing material usage and environmental impact. For example, the use of a single-sided mold in conjunction with a vacuum-assisted process significantly lowers tooling costs. Moreover, its compatibility with Automated Fiber Placement (AFP) systems ensures precise fiber alignment and efficient layer stacking, maintaining structural integrity even in large-scale applications. Additionally, the low viscosity of thermoplastic resins, such as MMA-based resins, enhances the process by enabling thorough infiltration into dry fibers without disturbing their alignment. This versatility not only facilitates the production of high-performance blades but also supports the integration of recyclable materials, addressing critical end-of-life waste management challenges in the wind energy sector.

Efforts to address this challenge have driven the development of recyclable resin technologies. Notable examples include recyclable epoxy systems, such as Siemens' Recyclamine and Vestas' Swancor, as well as thermoplastic resin systems like Arkema's Elium, used by LM Wind Power. These innovations enable blades to be chemically or mechanically recycled, overcoming the limitations of traditional thermosetting resins. For instance, Arkema's Elium resin facilitates the production of thermoplastic composite blades that are lightweight, durable, and recyclable through depolymerization. Similarly, Siemens has introduced recyclable blades using advanced epoxy systems, establishing new benchmarks for sustainability in wind energy [

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, research on chemical recycling methods has demonstrated significant potential for reclaiming raw materials. Chemical recycling focuses on breaking down polymer chains into monomers, which can be re-polymerized into high-performance resins, whereas mechanical recycling reprocesses materials into secondary products with minimal degradation [

11]. The depolymerization of acrylic thermoplastic resins has also emerged as a pivotal technology, offering a scalable approach to recovering high-quality monomers [

12]. These advancements not only address the end-of-life challenges of wind turbine blades but also align with global sustainability goals by reducing the environmental impact of composite materials [

13].

Arkema's Elium resin has been a transformative innovation in advancing thermoplastic composite technology for wind turbine blades. Its unique properties—lightweight, high durability, and recyclability through depolymerization—have positioned it as a preferred material in numerous industrial applications. One significant advancement was the fabrication of a 12-meter thermoplastic blade by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) using Elium resin. This project demonstrated the resin's compatibility with vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding (VARTM) and its capability to produce large-scale components with exceptional mechanical performance [

14]. Furthermore, Arkema's collaboration with LM Wind Power led to the production of a 100-meter thermoplastic composite blade, representing a major milestone in sustainable wind energy solutions [

15]. Despite these accomplishments, Elium-based resins for wind turbine blades have certain limitations. The resin's fixed infusion parameters restrict customization for varying blade lengths or geometries, limiting its adaptability to different manufacturing requirements. Nevertheless, Elium's successful commercialization has catalyzed global research and innovation in thermoplastic resin systems, underscoring its potential to redefine the future of composite materials [

16].

Arkema's Elium resin has been a transformative innovation in advancing thermoplastic composite technology for wind turbine blades. Its unique properties—lightweight, high durability, and recyclability through depolymerization—have positioned it as a preferred material in numerous industrial applications. One significant advancement was the fabrication of a 12-meter thermoplastic blade by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) using Elium resin. This project demonstrated the resin's compatibility with vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding (VARTM) and its capability to produce large-scale components with exceptional mechanical performance [

14]. Furthermore, Arkema's collaboration with LM Wind Power led to the production of a 100-meter thermoplastic composite blade, representing a major milestone in sustainable wind energy solutions [

15]. Despite these accomplishments, Elium-based resins for wind turbine blades have certain limitations. The resin's fixed infusion parameters restrict customization for varying blade lengths or geometries, limiting its adaptability to different manufacturing requirements. Nevertheless, Elium's successful commercialization has catalyzed global research and innovation in thermoplastic resin systems, underscoring its potential to redefine the future of composite materials [

16].

Long before the development of Arkema's Elium resin, research into acrylic resins established a strong foundation for their industrial applications. Acrylic resins, primarily based on methyl methacrylate (MMA), exhibit exceptional mechanical properties, including high strength, ductility, and impact resistance, while retaining a thermoplastic nature. These attributes, combined with their liquid state, make them ideal for infusion processes used to fabricate complex composite structures [

17,

18]. The primary constituents of acrylic resins, such as MMA, dimethyl aniline (DMA), and benzoyl peroxide (BPO), have been extensively studied to optimize curing and polymerization behavior. For instance, DMA extends working life and enhances mechanical properties, while BPO effectively initiates polymerization at room temperature [

19,

20]. Additionally, recent studies on dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) as a resin additive have shown its potential to improve curing kinetics and material toughness under specific conditions [

21]. Efforts to enhance acrylic resin performance have also involved incorporating advanced materials like trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TMPTMA) to improve thermal stability and mechanical strength. Moreover, the inclusion of nanoparticles such as silica and carbon nanotubes has further enhanced resin properties by improving dispersion and interfacial adhesion, resulting in superior composites for applications in sectors ranging from automotive to renewable energy [

22,

23]. Extensive research on acrylic resins underscores their versatility and potential to revolutionize composite manufacturing. These advancements not only paved the way for Elium's commercial success but also highlighted the importance of continuous innovation in acrylic resin technologies.

Despite significant advancements in acrylic resin research, several limitations remain unresolved. Current production methods for PMMA-based acrylic resins are relatively rigid, limiting the ability to tailor resin properties for specific applications. Furthermore, existing techniques for predicting resin infusion, especially for structures with varying lengths or geometries, lack precision and scalability. This limitation hampers the optimization of infusion processes for large-scale applications, such as wind turbine blades [

24]. Additionally, a comprehensive modeling approach that links resin composition to key factors, such as induction time and mechanical properties, is largely absent in current research [

25].

A critical challenge lies in optimizing induction time and tensile strength, which are essential for large-scale composite structures like wind turbine blades. Induction time plays a pivotal role in the resin infusion process, ensuring sufficient working time before curing initiates. During the infusion of large-scale structures, premature curing can lead to incomplete infiltration, resulting in voids or defects in the composite. Optimizing induction time is therefore vital to balancing process efficiency with complete resin distribution, ensuring structural integrity [

23]. Tensile strength, on the other hand, is a key performance indicator for assessing the mechanical performance of composite materials. High tensile strength ensures that the composite can withstand operational loads and stress, making it a critical parameter in evaluating material performance [

12].

Despite these considerations, current research lacks a systematic methodology for optimizing resin performance tailored to large-scale wind turbine blade applications. Existing studies often fail to establish correlations between critical parameters such as induction time, viscosity, and mechanical strength, making it challenging to achieve consistent manufacturing performance [

24]. Moreover, comprehensive evaluations of mechanical properties, including tensile strength and fatigue performance, remain scarce [

25].

To address these challenges, this study proposes a methodology for developing recyclable thermoplastic resin systems optimized for large-scale structural applications. By establishing predictive models to optimize resin composition and conducting detailed evaluations of induction time and tensile strength, this research provides a robust framework for sustainable wind turbine blade manufacturing. Additionally, the study validates these methodologies in composite materials, facilitating direct comparisons between experimental and simulated conditions and addressing real-world challenges in resin infusion and curing processes [

12,

23].

6. Summary and Conclusion

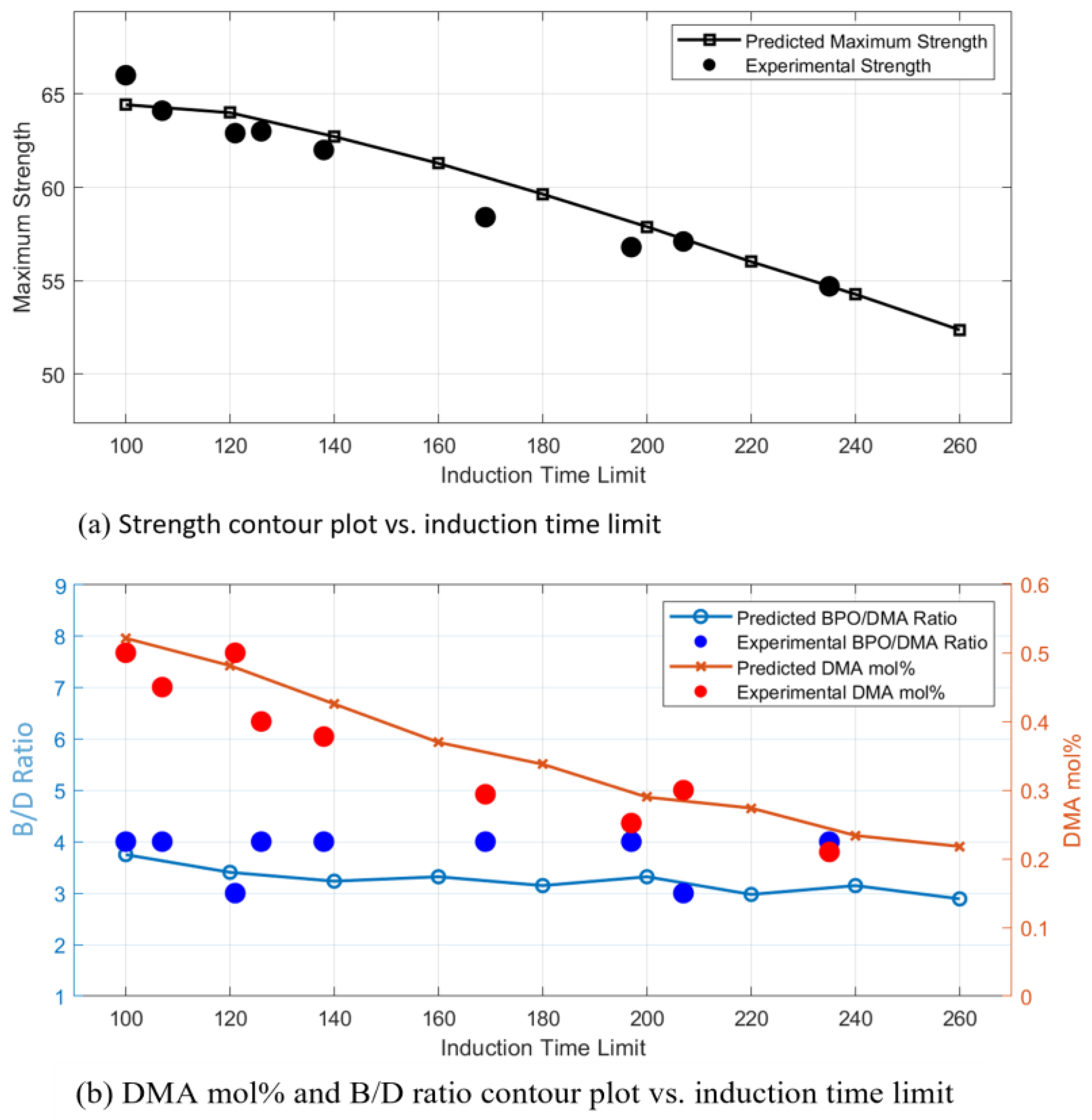

This study developed polynomial regression models to predict both induction time (IT) and tensile strength based on two key composition parameters: DMA mol% and the BPO/DMA (B/D) ratio. These models captured the complex interplay among MMA, DMA, and BPO, enabling a formulation design tool that effectively balances processing time with mechanical performance. The resulting predictive framework provides a reliable method for identifying optimal resin compositions to achieve maximum tensile strength within a target IT range.

The PMMA resin formulations derived from this framework were applied in the fabrication of composite panels using vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding (VARTM). The resins exhibited excellent infusion characteristics, enabling uniform impregnation of both unidirectional (UD) and biaxial (BX) fiber reinforcements. Compared to conventional epoxy systems, the composites achieved higher fiber volume fractions, demonstrating improved flowability and fiber packing. The fabricated panels also exhibited stable mechanical behavior, indicating that PMMA resins are well-suited for producing recyclable, high-performance composite structures using standard infusion techniques.

It can be concluded that the PMMA resins show strong potential to replace conventional thermosetting resins in large-scale structural infusion processes, such as wind turbine blade manufacturing. Their tunable processing behavior, combined with competitive mechanical properties and inherent recyclability, provides significant advantages in terms of design flexibility and alignment with sustainability and circular economy goals. Furthermore, the applicability of PMMA-based composites can be extended to fatigue-critical applications, where their performance under cyclic loading may support long-term use in high-efficiency, recyclable composite structures.

Figure 1.

Chemical formulas and sample photos of components required for polymerization.

Figure 1.

Chemical formulas and sample photos of components required for polymerization.

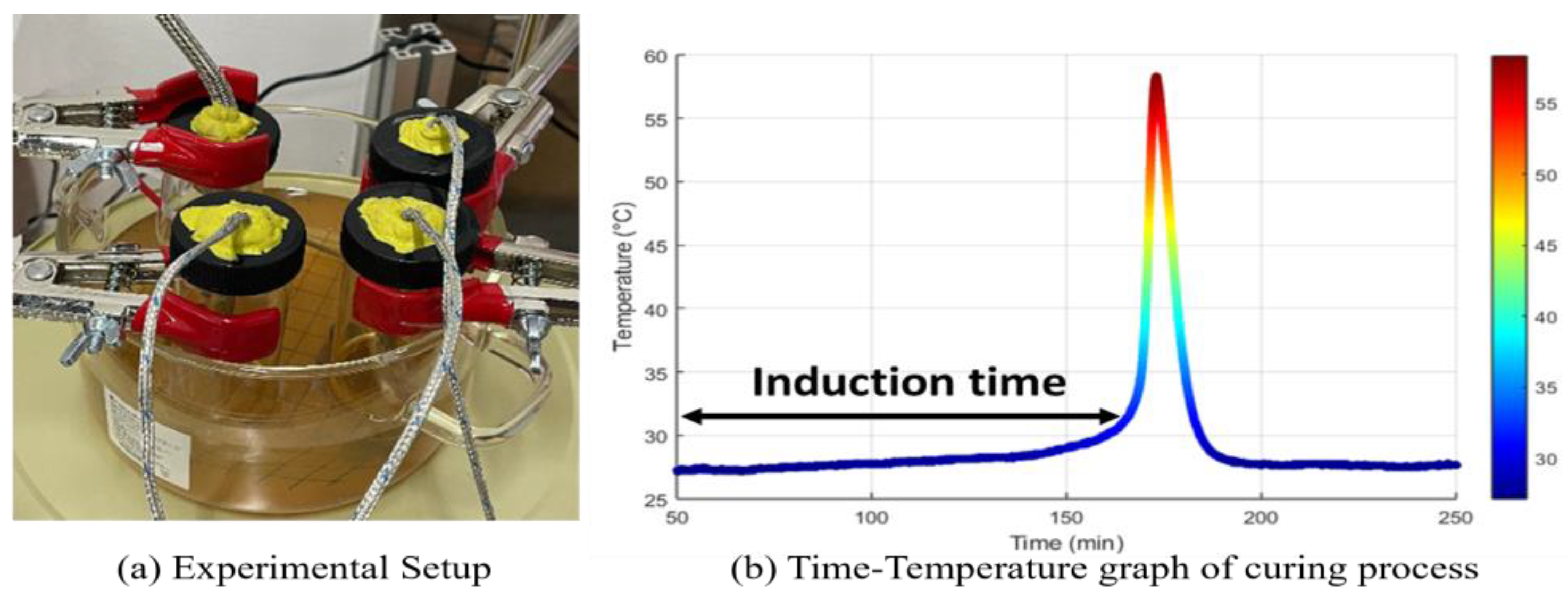

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental setup to measure the temperature evolution during the curing reaction of resin in constant temperature bath, (b) Time-Temperature graph of curing Resin Process.

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental setup to measure the temperature evolution during the curing reaction of resin in constant temperature bath, (b) Time-Temperature graph of curing Resin Process.

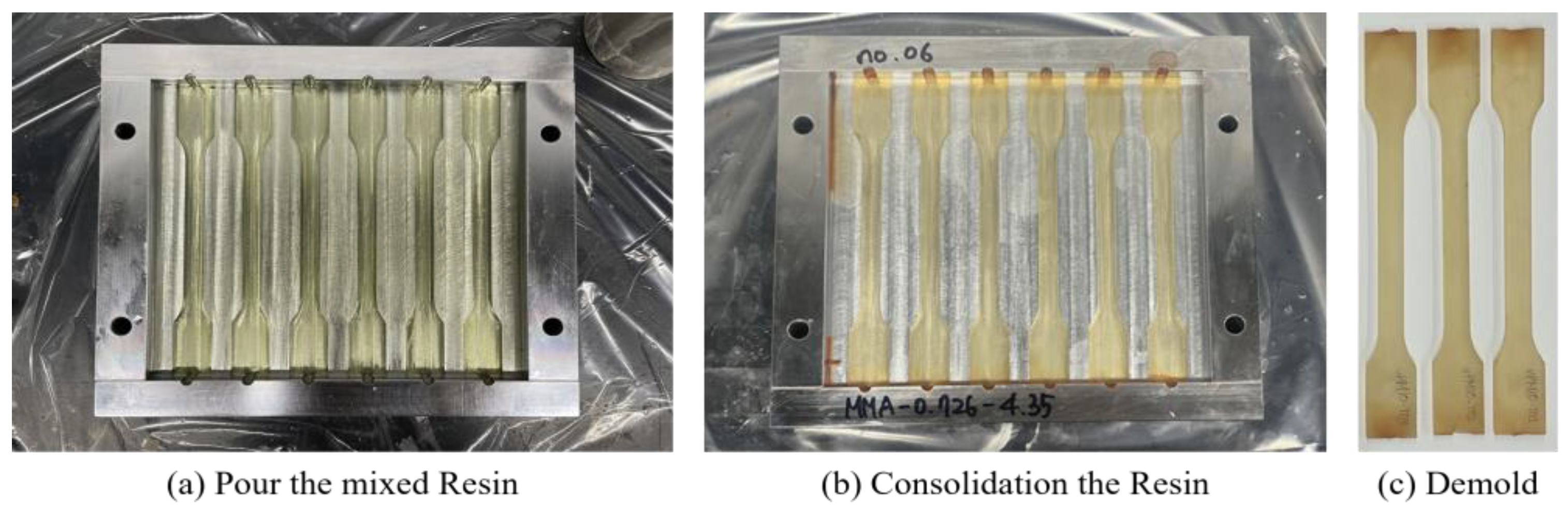

Figure 3.

(a) Pour the mixed resin into ISO 527-2 Steel mold, after applied release agent, (b) Consolidation at Room temperature, followed by Post curing (70°C for 2hours), (c) Demold and sand lightly to make surface uniform.

Figure 3.

(a) Pour the mixed resin into ISO 527-2 Steel mold, after applied release agent, (b) Consolidation at Room temperature, followed by Post curing (70°C for 2hours), (c) Demold and sand lightly to make surface uniform.

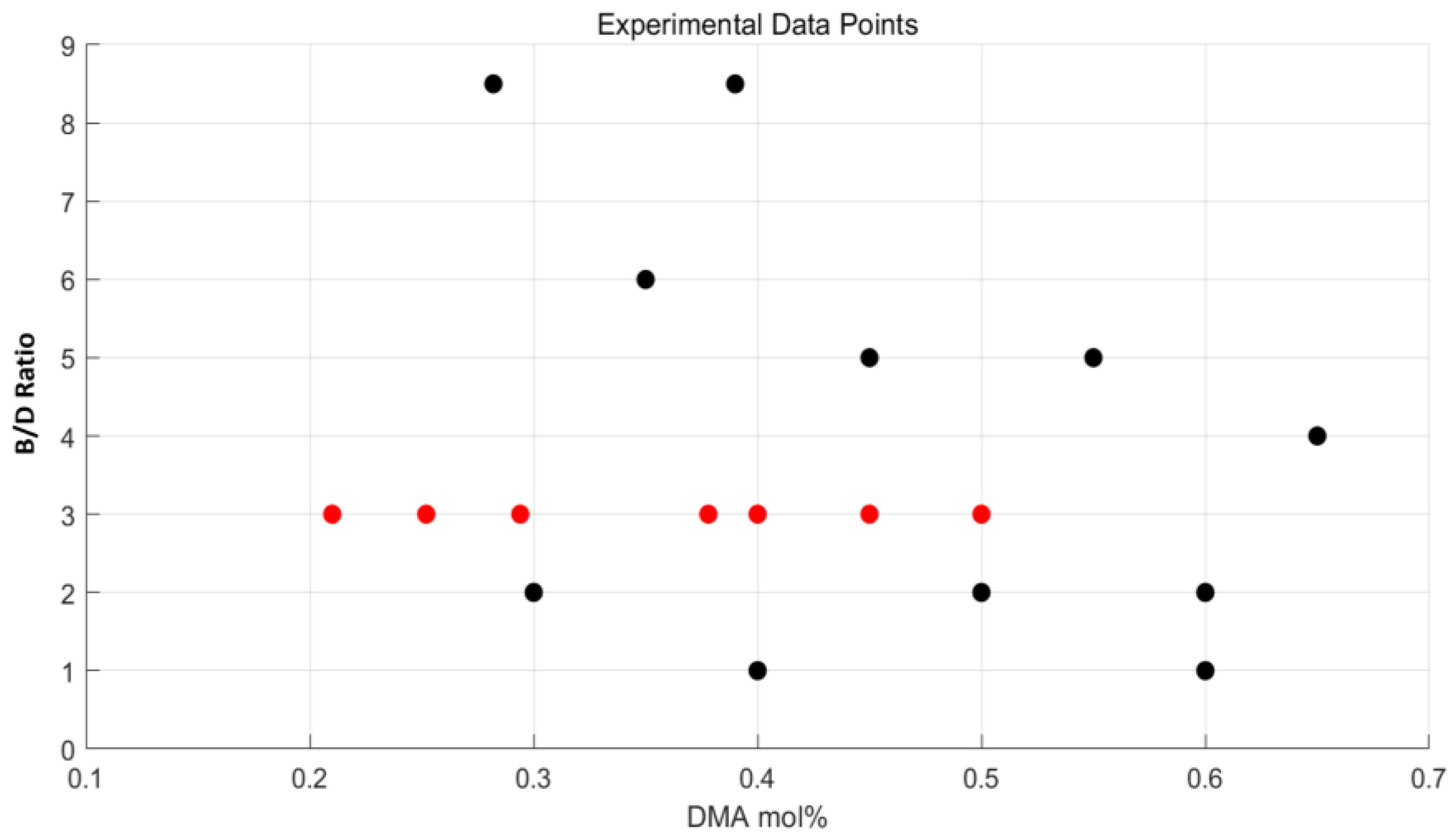

Figure 4.

Experimental Data Points Test showing 18 cases with varying B/D ratio (2.0–9.5) and DMA mol% (0.28–0.65).

Figure 4.

Experimental Data Points Test showing 18 cases with varying B/D ratio (2.0–9.5) and DMA mol% (0.28–0.65).

Figure 5.

(a) 3D plot of Induction time - B/D ratio=4, (b) 2D plot of Induction time - B/D ratio= 4.

Figure 5.

(a) 3D plot of Induction time - B/D ratio=4, (b) 2D plot of Induction time - B/D ratio= 4.

Figure 6.

Grouped by B/D Ratio, Experiment Result of Induction Time-DMA mol%.

Figure 6.

Grouped by B/D Ratio, Experiment Result of Induction Time-DMA mol%.

Figure 7.

Grouped by B/D Ratio, Experiment Result of Strength-DMA mol%.

Figure 7.

Grouped by B/D Ratio, Experiment Result of Strength-DMA mol%.

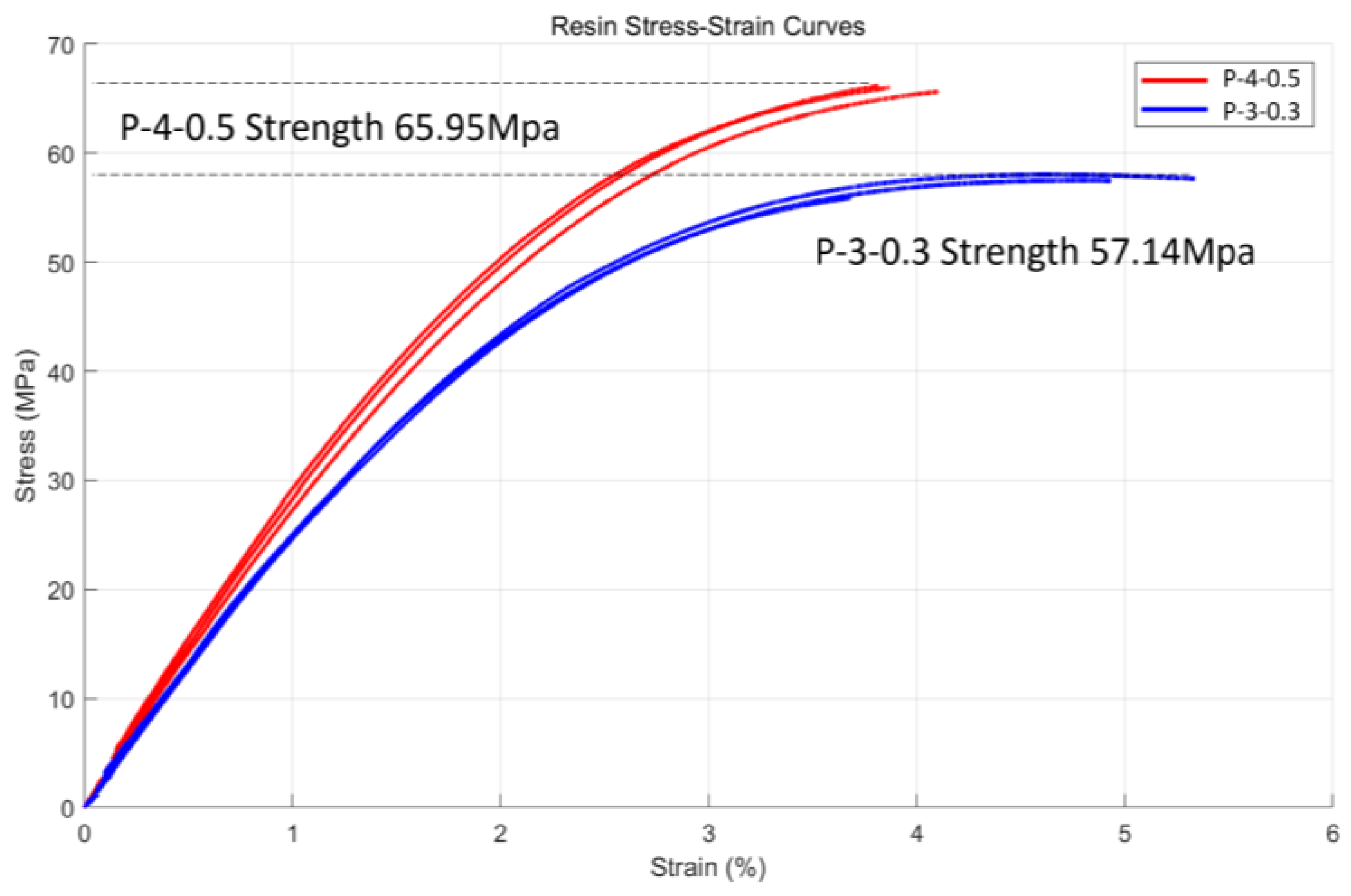

Figure 8.

Tensile Stress – Strain Curve of Resin, ‘P-4-0.5’ and ‘P-3-0.3’.

Figure 8.

Tensile Stress – Strain Curve of Resin, ‘P-4-0.5’ and ‘P-3-0.3’.

Figure 9.

Strength surface and contour plots with experimental points, showing the effects of DMA mol% and B/D ratio, (a) Strength - B/D ratio (Side view), (b) 3D Strength Surface Plot with Projected contour, (c) Strength Contour Plot, (d) Strength - DMA mol% (Side view).

Figure 9.

Strength surface and contour plots with experimental points, showing the effects of DMA mol% and B/D ratio, (a) Strength - B/D ratio (Side view), (b) 3D Strength Surface Plot with Projected contour, (c) Strength Contour Plot, (d) Strength - DMA mol% (Side view).

Figure 10.

Induction time surface and contour plots with experimental points, showing the effects of DMA mol% and B/D ratio, (a) Induction time - B/D ratio (Side view), (b) 3D Induction time Plot with Projected contour, (c) Induction time Contour Plot, (d) Induction time DMA mol% (Side view).

Figure 10.

Induction time surface and contour plots with experimental points, showing the effects of DMA mol% and B/D ratio, (a) Induction time - B/D ratio (Side view), (b) 3D Induction time Plot with Projected contour, (c) Induction time Contour Plot, (d) Induction time DMA mol% (Side view).

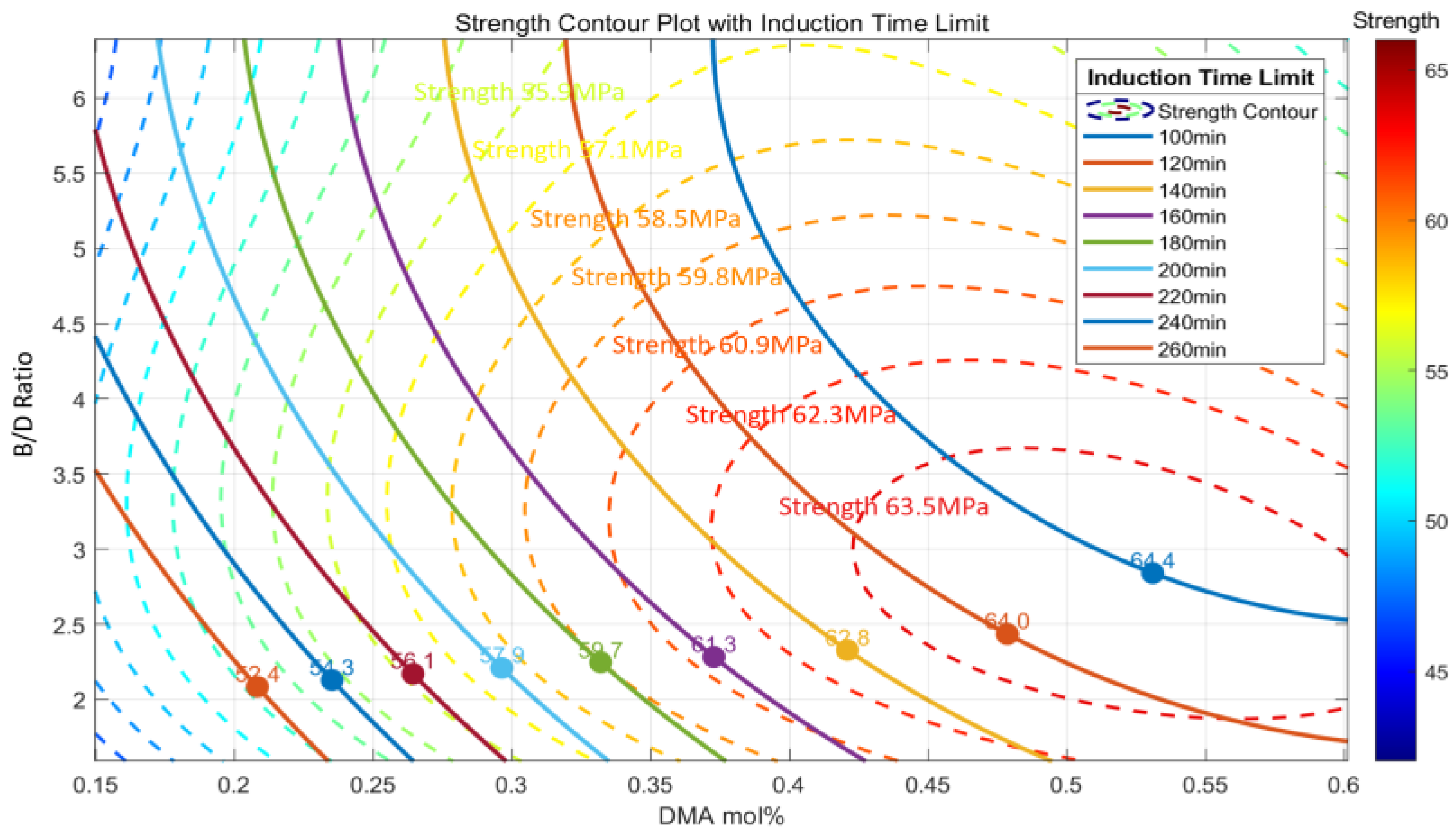

Figure 11.

Strength contour plot with induction time limit.

Figure 11.

Strength contour plot with induction time limit.

Figure 12.

Induction time surface and contour plots with experimental points, showing the effects of DMA mol% and B/D ratio, (a) Induction time - DMA mol% (Side view), (b) 3D Induction time Plot with Projected contour, (c) Induction time Contour Plot, (d) Induction time - B/D ratio (Side view).

Figure 12.

Induction time surface and contour plots with experimental points, showing the effects of DMA mol% and B/D ratio, (a) Induction time - DMA mol% (Side view), (b) 3D Induction time Plot with Projected contour, (c) Induction time Contour Plot, (d) Induction time - B/D ratio (Side view).

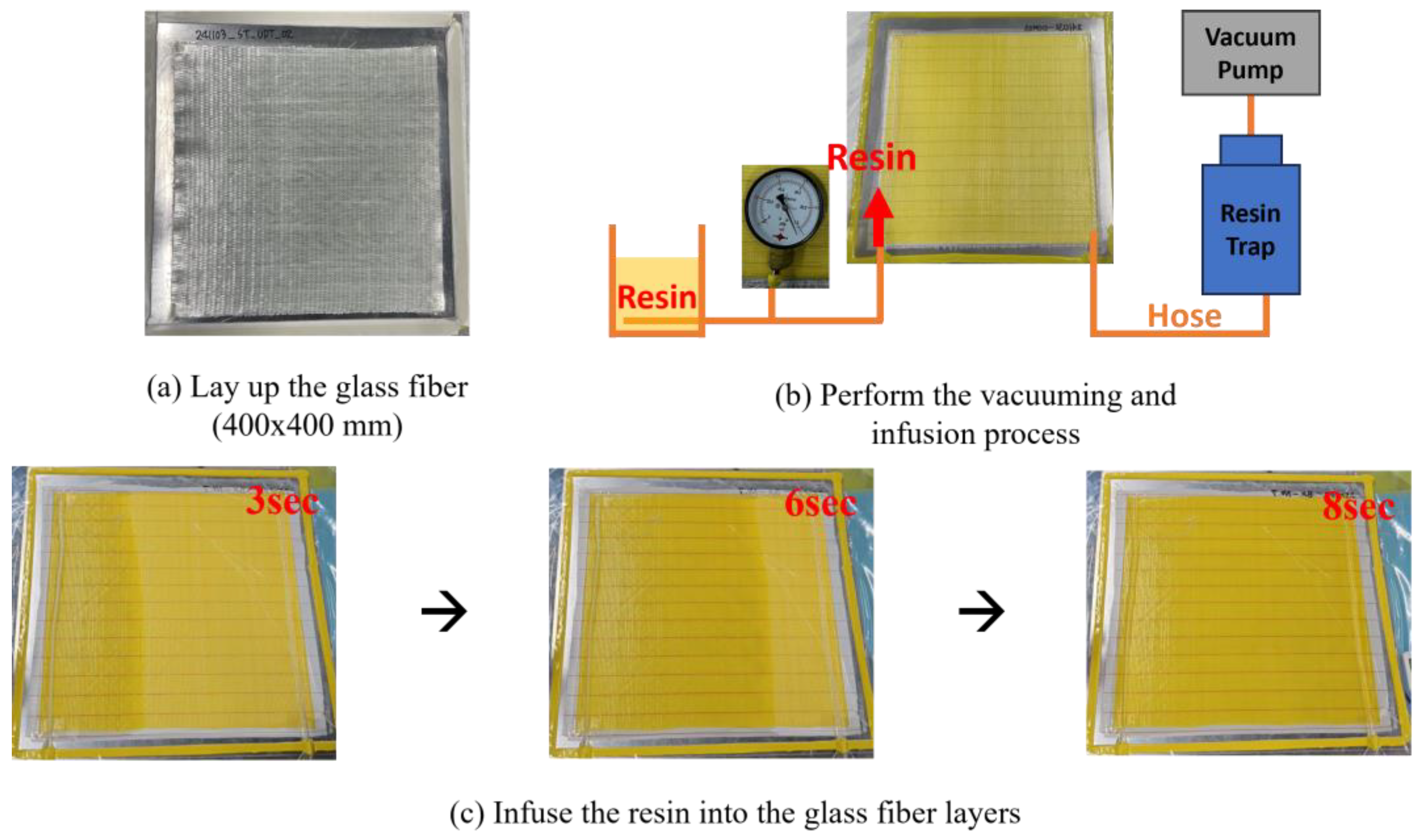

Figure 13.

(a) Apply Release Agent and Sealant Tape, Layup Glass Fiber, 2layer 400x400(mm) two layers of glass fiber, 0° orientation, OC-L1240, (b) Lay up the infusion consumables, and vacuuming for at least 15min, (c) Infuse the resin into the glass fiber layers.

Figure 13.

(a) Apply Release Agent and Sealant Tape, Layup Glass Fiber, 2layer 400x400(mm) two layers of glass fiber, 0° orientation, OC-L1240, (b) Lay up the infusion consumables, and vacuuming for at least 15min, (c) Infuse the resin into the glass fiber layers.

Figure 14.

Measurement Process of Induction Time during the Composite Curing Process.

Figure 14.

Measurement Process of Induction Time during the Composite Curing Process.

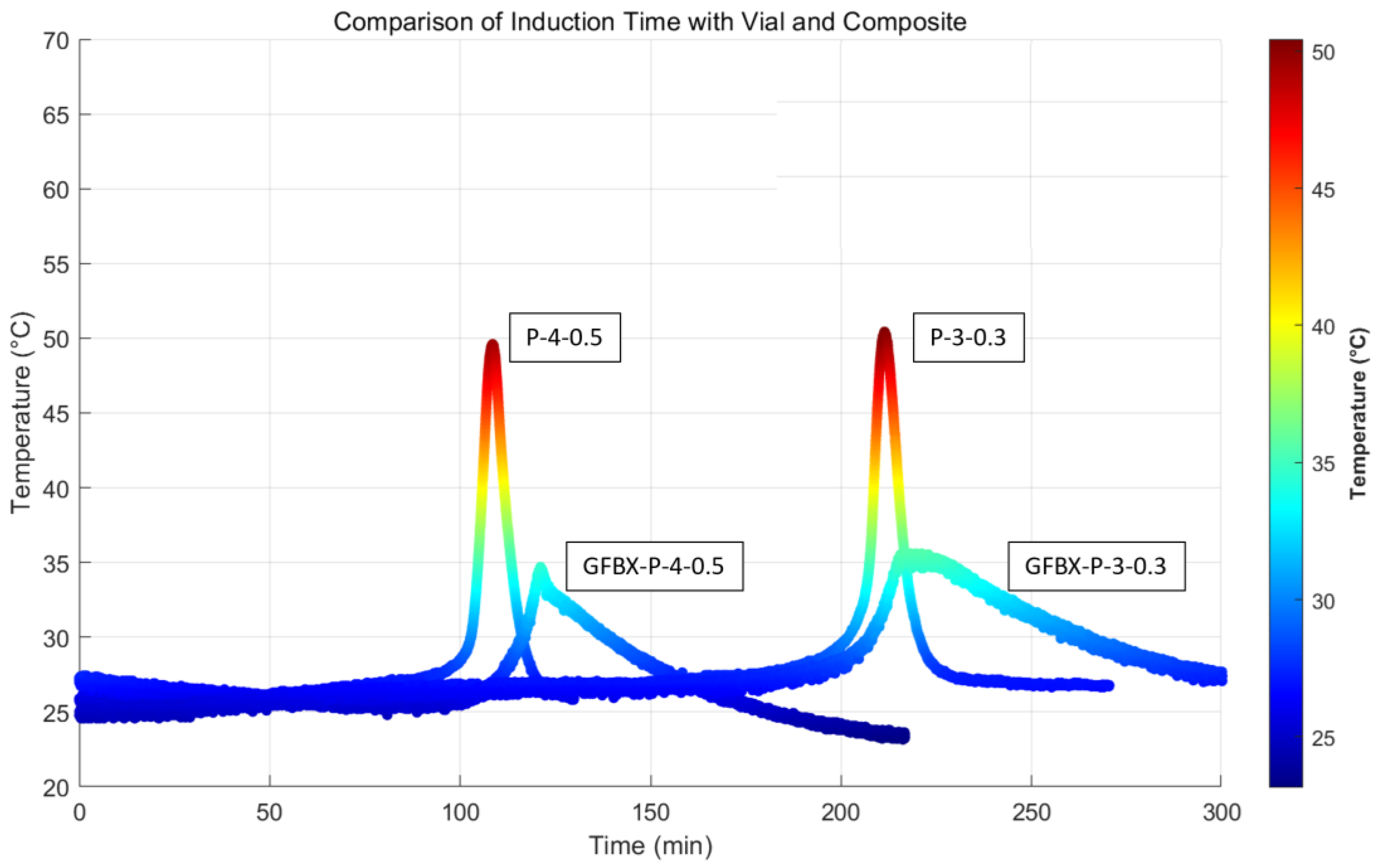

Figure 15.

Comparison of Induction time with Vial and Composite.

Figure 15.

Comparison of Induction time with Vial and Composite.

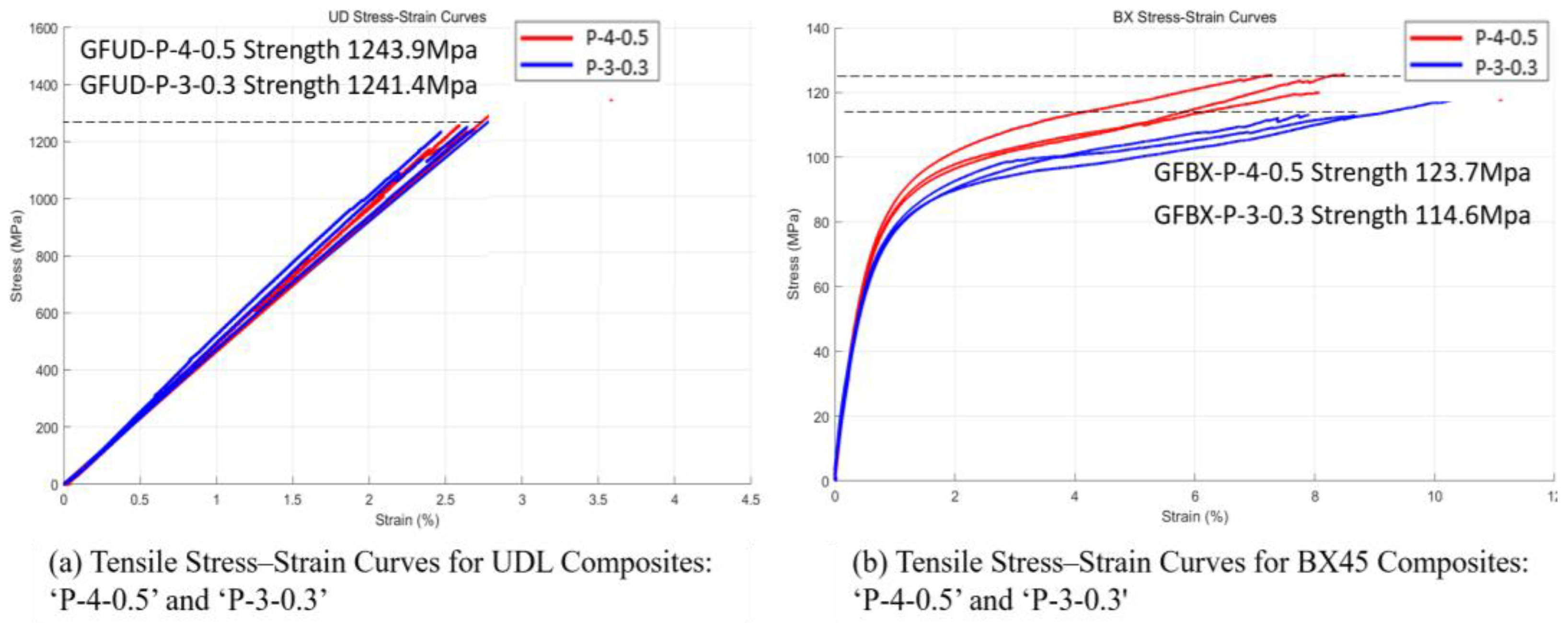

Figure 16.

(a) Tensile Stress–Strain Curves for UDL composite of ‘GFUD-P-4-0.5’ and ‘GFUD-P-3-0.3’ (b) Tensile Stress–Strain Curves for BX45 composite of ‘GFBX-P-4-0.5’ and ‘GFBX-P-3-0.3’.

Figure 16.

(a) Tensile Stress–Strain Curves for UDL composite of ‘GFUD-P-4-0.5’ and ‘GFUD-P-3-0.3’ (b) Tensile Stress–Strain Curves for BX45 composite of ‘GFBX-P-4-0.5’ and ‘GFBX-P-3-0.3’.

Table 1.

Experimental data of DMA mol%, B/D ratio, tensile strength, and induction time. (P-x-y where x = B/D ratio and y = DMA mol%).

Table 1.

Experimental data of DMA mol%, B/D ratio, tensile strength, and induction time. (P-x-y where x = B/D ratio and y = DMA mol%).

Test ID:

P-x-y

|

P-2-0.4 |

P-2-0.6 |

P-3-0.3 |

P-3-0.5 |

P-3-0.6 |

P-4-0.21 |

P-4-0.25 |

P-4-0.29 |

P-4-0.38

|

P-4-0.4 |

P-4-0.45 |

P-4-0.5 |

P-5-0.65 |

P-6-0.45 |

P-6-0.55 |

P-7-0.35 |

P-9.5-0.28 |

P-9.5-0.39 |

| B/D Ratio, x |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

| DMA (mol%), y |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.21 |

0.25 |

0.29 |

0.38 |

0.4 |

0.45 |

0.5 |

0.65 |

0.45 |

0.55 |

0.35 |

0.28 |

0.39 |

Table 2.

Coefficients of Polynomial Equations (1, 2) for Strength and IT.

Table 2.

Coefficients of Polynomial Equations (1, 2) for Strength and IT.

| |

p00 |

p10 |

p01 |

p20 |

p11 |

p02 |

p21 |

p12 |

p03 |

| Strength, S |

15.68 |

107.99 |

11.46 |

-65.25 |

8.51 |

-2.76 |

-15.36 |

-0.32 |

0.19 |

| Induction Time, IT |

341.46 |

1507.63 |

-54.04 |

836.73 |

23.78 |

3.52 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 3.

Comparative data of P-3-0.3, P-4-0.5, Epoxy Performance in UDL & BX45 Composites (UDL: unidirectional laminate, BX45: ±45° biaxial laminate).

Table 3.

Comparative data of P-3-0.3, P-4-0.5, Epoxy Performance in UDL & BX45 Composites (UDL: unidirectional laminate, BX45: ±45° biaxial laminate).

| |

UDL |

BX45

|

|

| |

P-3-0.3 |

P-4-0.5 |

Epoxy [29] |

P-3-0.3 |

P-4-0.5

|

Epoxy [29] |

Epoxy [30] |

| Volume Fraction |

64% |

64% |

54% |

64% |

64% |

44% |

- |

| Stiffness (Gpa) |

46.9 |

46.6 |

41.8 |

13.1 |

14.2 |

13.6 |

8.2 |

| Strength (Mpa) |

1241 |

1243.9 |

972 |

115 |

124 |

144 |

78.7 |

| Failure strain (%) |

2.65 |

2.65 |

2.44 |

9.02 |

7.96 |

2.16 |

>10 |