Introduction

Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV), a tick-borne flavivirus within the Flaviviridae family, causes a severe hemorrhagic fever known as Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD), primarily in India. KFDV was first identified in 1957 in Karnataka’s Shimoga district, which is transmitted by

Haemaphysalis spinigera ticks in a zoonotic cycle with in the small mammals, monkeys, and humans as dead-end hosts [

1,

2,

3]. The disease presents with biphasic symptoms, including fever, headache, and hemorrhage, with 10–20% of cases progressing to neurological complications and a 3–5% case fatality rate [

4,

5,

6]. Following its initial identification in 1957, approximately 10,000 cases of KFD were reported through 2017, with notable epidemic episodes documented during 1957–1958 (681 cases), 1983–1984 (2,589 cases), 2002–2003 (1,562 cases), and 2016–2017 (809 cases) [

7]. Recent data (2019–2024) indicate 700–900 additional cases [

8,

9], predominantly in Karnataka (e.g., Shivamogga, Chikkamagaluru) but with emerging transmission in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Maharashtra, driven by deforestation, climate factors, and increased human-tick contact [

10,

11].

KFDV poses a growing public health challenge due to its geographic expansion and limited control measures [

7,

9,

12].The current formalin-inactivated vaccine, with 62.4% efficacy for two doses and 82.9% with boosters, faces challenges from waning immunity and production issues, contributing to persistent outbreak. Due to suboptimal protection, the Kerala government has stopped its vaccination in October 2022 (Department of health and family welfare, Karnataka Goverment). The ongoing research and development on vaccine candidates represent a significant advancement beyond the currently available formalin-inactivated vaccine, which has shown limited and variable efficacy even in potency test. Novel approaches—including vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-based live-attenuated platforms [

15,

16], subunit vaccines utilizing the recombinant envelope domain III [

17], and

in silico–designed multi-epitope constructs demonstrate promising immunogenicity and protective efficacy in preclinical models [

18]. Additionally, rational design strategies supported by immunoinformatics have enabled the identification of conserved and immunodominant epitopes with potential cross-protective capabilities against related flaviviruses, such as Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus [

18,

19,

20]. These vaccine candidates, though largely in early development stages, highlight a strategic shift toward more targeted and immunologically robust interventions. Continued experimental validation, coupled with collaborative frameworks led by institutions like Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-National Institute of Virology (NIV), will be critical to advancing these candidates toward clinical evaluation.

No specific antivirals are currently approved for KFDV, supportive care remains the standard. The promising repurposed drug candidate, NITD008 (a nucleoside analog inhibitor, broadly use to treat flavivirus infection) has emerged through computational modeling and showed

in vitro activity against KFDV [

21]. Nonetheless, the

in vivo studies are essential to validate protective efficacy to advance the compound toward clinical application.

Current KFDV diagnostics, led by RT-PCR and ELISA, provide reliable detection but are constrained by timing, infrastructure, and cross-reactivity issues. Recent advances, such as dry-down RT-PCR and POC devices, offer hope for faster, field-based diagnosis [

22]. Further efforts are being made on multiplex assays, scalable technologies, and integrated surveillance to improve accuracy and accessibility, particularly for resource poor setting [

23].

Surveillance gaps, such as inconsistent case reporting and limited animal monitoring, further complicate outbreak response. These factors, combined with KFDV’s potential for cross-border spread and climate-driven tick dispersal [

11,

24] underscore the need for a comprehensive understanding of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control strategies (National Public Health India Conference, 20240.

https://ncdc.mohfw.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/E-Technodoc-_V9.pdf)

This review emphasizes current knowledge on KFDV, addressing five key areas: epidemiology (recent trends and regional spread), pathogenesis (molecular and immune mechanisms), therapeutics (repurposed drugs and gaps), vaccines (current and novel candidates), and diagnostics (advances and limitations). By integrating KFDV recent case data (from 2019–2024), and drawing on molecular, clinical, and public health studies, we aim to highlight research progress and gaps. The review also explores future directions, such as drug repurposing, next-generation vaccines, and enhanced surveillance, to mitigate KFDV infection. As KFDV emerges as an important public health concern, this review would offer critical insights for researchers, policymakers, and public health practitioners.

Epidemiology and Transmission of KFDV

KFDV, a tick-borne arbovirus, belongs to the Flaviviridae family, genus

Flavivirus, was first identified in 1957 in the Shimoga district of Karnataka, India. KFDV is primarily endemic to the Western Ghats region of India, with cases reported in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Goa, and Maharashtra. Since its first incidence, the virus has exhibited significant geographical expansion beyond its endemic foci [

10], with ~10,000 human cases were documented, reflecting the virus persistence and spread to new ecological niches [

7]. The spread of virus is majorly driven by factors such as deforestation, anthropogenic intrusion into forest habitats, changes in vector and host dynamics [

10]. The emergence of cases in neighboring states such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujrat underscores the evolving epidemiology of KFDV and highlights the need for robust surveillance, vector control, and public health interventions in the expanding endemic zones [

10,

25,

26,

27]. Annual cases fluctuate, with 100–500 reported in peak years. Outbreaks occur mainly during dry months (December–May), aligning with peak tick activity and human forest visits [

28]. Studies reported in Shivamogga, Karnataka, noted inconsistent case reporting, complicating incidence estimates [

29,

30]. Seroprevalence studies suggest underreporting, as asymptomatic or mild cases may go undetected [

12]. Recent data (from 2019–2024), suggested that the range of KFDV expanded and cases were reported from different parts of Maharashtra and Gujrat states [

8,

31]. Cross-border spread to neighboring countries is a concern but direct evidences are lacking. Enhanced surveillance and one health approaches could to curb to public health impact of KFDV [

12].

KFDV is transmitted via bites from infected ticks, primarily

Haemaphysalis spinigera [

3,

32]. The virus circulates in a zoonotic cycle among the small mammals (e.g., rodents, shrews), monkeys (e.g., red-faced bonnet and gray langurs), and ticks. Monkeys are considered as amplifying host for the virus, and their deaths signal outbreak hotspots. Humans infected accidently and serve as dead-end hosts, with no direct evidence of human-to-human transmission reported yet. Occupational exposure (e.g., forest workers, farmers, hunters and tribal populations) increases the risk, particularly near areas with dead monkeys. A case-control study in Shivamogga (2022) highlighted the proximity to forested areas and dead monkey sites are major risk factors to spread the disease. Other factors include lack of protective clothing, low vaccination coverage, and environmental changes like deforestation, which increase tick-human interactions. Children and adults in rural settings are equally affected, with no clear gender bias [

31].

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution and potential spread of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV) in India. The map illustrates the current distribution of Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD) cases (red) and states considered at risk for future spread (yellow), based on ecological suitability, tick vector prevalence, and forest coverage. The Western Ghats region, highlighted in red across states such as Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Maharashtra, represents the primary endemic zone. States in yellow indicate regions with potential for viral emergence due to ecological continuity and increasing human-tick interactions. Data reflect KFDV distribution trends as of 2024.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution and potential spread of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV) in India. The map illustrates the current distribution of Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD) cases (red) and states considered at risk for future spread (yellow), based on ecological suitability, tick vector prevalence, and forest coverage. The Western Ghats region, highlighted in red across states such as Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Maharashtra, represents the primary endemic zone. States in yellow indicate regions with potential for viral emergence due to ecological continuity and increasing human-tick interactions. Data reflect KFDV distribution trends as of 2024.

Figure 2.

Ecology and Transmission Cycle of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV). The ixodid tick Haemaphysalis spinigera serves as both the principal reservoir and vector for Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV). Infected ticks maintain lifelong viral carriage and facilitate transovarial transmission to progeny. The enzootic cycle involves small mammals and primates, which act as amplification hosts; infection in primates frequently results in epizootics characterized by high mortality rates. Although larger domesticated animals (e.g., cattle, goats, and sheep) may acquire KFDV infection, they are considered incidental hosts with minimal contribution to human transmission dynamics. Pet animals may acquire disease from the infected ticks and facilitate tick dispersal. During the dry season, zoonotic spillover occurs, with humans becoming accidental (dead-end) hosts, typically through exposure to infected ticks or contact with infected animal carcasses. Individuals engaging in forest-related occupational or recreational activities are at elevated risk of exposure. Red crosses indicate blocked transmission pathways.

Figure 2.

Ecology and Transmission Cycle of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV). The ixodid tick Haemaphysalis spinigera serves as both the principal reservoir and vector for Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV). Infected ticks maintain lifelong viral carriage and facilitate transovarial transmission to progeny. The enzootic cycle involves small mammals and primates, which act as amplification hosts; infection in primates frequently results in epizootics characterized by high mortality rates. Although larger domesticated animals (e.g., cattle, goats, and sheep) may acquire KFDV infection, they are considered incidental hosts with minimal contribution to human transmission dynamics. Pet animals may acquire disease from the infected ticks and facilitate tick dispersal. During the dry season, zoonotic spillover occurs, with humans becoming accidental (dead-end) hosts, typically through exposure to infected ticks or contact with infected animal carcasses. Individuals engaging in forest-related occupational or recreational activities are at elevated risk of exposure. Red crosses indicate blocked transmission pathways.

KFD virus and Pathogenesis

KFDV is an enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus within the Flaviviridae family. It has ~11 kb genome, encodes a single polyprotein cleaved into three structural proteins: capsid (C), premembrane/membrane (prM/M), and envelope (E), and seven nonstructural (NS) proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5). Like other flavivirus such as dengue and Zika virus, KFDV-E protein mediates cell entry and is a key target for neutralizing antibodies following viral infection, while C is the primary structural protein of virus, which surrounds the viral genome. Pre-membrane (prM) is glycosylated precursor protein to the small transmembrane protein M, which primarily facilitates the virus maturation and entry to host cell. Like DENV, NS1 plays important role in immune-evasive and induces oxidative stress by activating antioxidant defenses. NS1 Abs could contributes in vascular leakage by disrupting the endothelial glycocalyx as in case of dengue or may play a critical role in immune responses that influence vascular permeability. But the exact mechanisms and implications of NS1 antibodies are still being investigated. NS2a and NS2b along with NS4a and NS4b participates in virus replication and pathogenesis. However, NS3 has a serine protease (NS3pro) and helicase (NS3hel), which are involved in both viral replication and maturation [

33]. While NS5, with its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and methyltransferase activities, drives viral replication and inhibits host interferon (IFN) responses [

34,

35].

The KFD virus upon

Haemaphysalis spinigera tick bites, it starts replicating in host’s skin dendritic cells before disseminating to lymphoid tissues, liver, spleen, and, in severe cases, the brain, and leads to viremia within 3–8 days, which correlates with the first phase of fever and systemic symptoms [

36]. The KFDV tropism for hepatocytes and endothelial cells contributes to hemorrhagic manifestations, while neuroinvasion, observed in 10–20% cases and causes meningitis or encephalitis (second phase or toxic phase) [

36,

37]. Recent study on bonnet macaques, showed viral RNA in spleen, liver, and brain, with only 20% developing severe disease, suggesting host factors modulate outcomes [

38]. The molecular mechanisms underlying KFDV neuroinvasiveness remain poorly defined.

In terms of host-pathogen interactions, KFDV employs multiple strategies to evade host defenses. The NS5 protein inhibits the IFN-α/β signaling by suppressing STAT2 phosphorylation, similar to other flaviviruses like DENV and ZIKV [

39]. NS3, a protease-helicase, facilitates polyprotein cleavage and viral replication, while NS1 disrupts complement activation [

40], enhancing systemic spread. Studies noted that KFDV’s envelope protein mutations may alter glycosaminoglycan binding like other flaviviruses and increasing infectivity in endothelial or neuronal cells [

36,

41,

42]. Host factors, such as polymorphisms in innate immune genes (e.g., TLR3, IFITM3), may influence disease severity, but no KFDV-specific studies have explored this. In contrast to Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus (AHFV), a KFDV variant that causes lethal disease in IFNAR-/- mice, KFDV’s pathogenesis in immunocompromised models like AG129 mice is untested, limiting insights into IFN-dependent mechanisms.

KFDV infection elicits robust innate and adaptive immune responses, though these are often delayed or insufficient to prevent severe disease. Devadiga et al. (2020) reported that human KFD patients found early activation of CD8 T-cells and natural killer cells, peaking 7–10 days post-infection, alongside proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) that correlate with fever and hemorrhage. B-cell responses produce IgM within 5–7 days, followed by IgG, which coincides with virus clearance in most cases. Prior vaccination enhances IgG titers, reducing disease severity. In bonnet macaques, 80% of infected animals cleared the virus without severe symptoms, suggesting effective Th1-driven immunity in some hosts. However, immune evasion by KFDV, particularly via NS5-mediated IFN suppression, allows prolonged viremia in severe cases. The role of antibody-dependent enhancement, observed in DENV, is unexplored in KFDV but warrants investigation given flavivirus similarities.

KFDV shares structural and pathogenic features with DENV, Zika, and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV). Like DENV, KFDV causes hemorrhagic fever and targets endothelial cells, but its neuroinvasiveness aligns more closely with TBEV. AHFV, a KFDV variant, exhibits higher lethality in IFNAR-/- mice, possibly due to distinct NS3/NS5 mutations, while KFDV’s neurovirulence may stem from passaging artifacts. Unlike DENV, which has robust mouse models (e.g., AG129), KFDV pathogenesis studies rely on BALB/c mice or primates, limiting molecular insights. The E protein’s role in receptor binding and immune evasion is conserved across flaviviruses, but KFDV’s specific host receptors (e.g., DC-SIGN, TIM-1) remain unidentified.

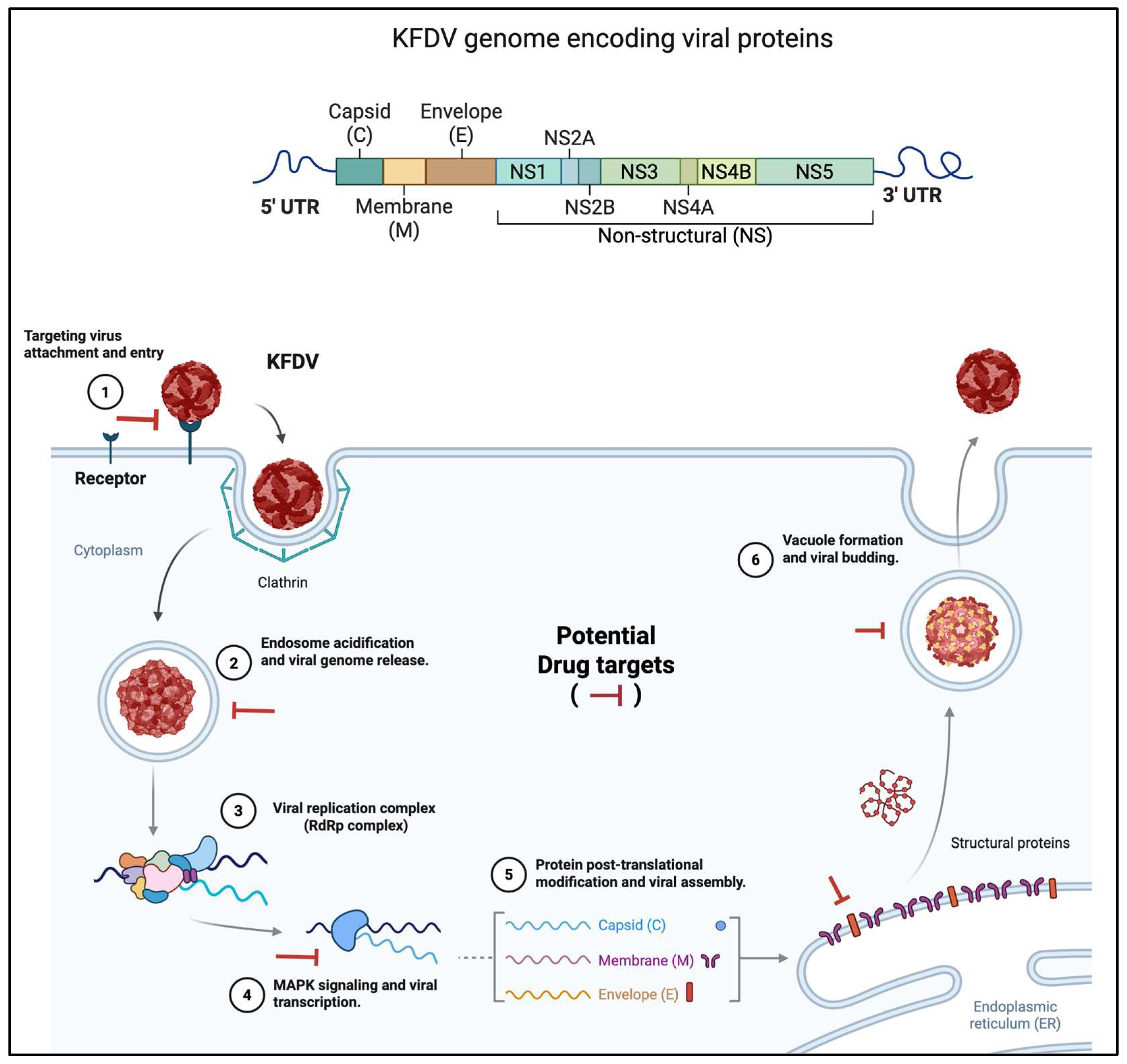

Figure 3.

Genome organization and replication cycle of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV) with potential antiviral targets. The top panel illustrates the genomic structure of KFDV, a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, comprising a single open reading frame flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). The genome encodes three structural proteins—capsid (C), membrane (M), and envelope (E)—followed by seven non-structural (NS) proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5), involved in replication and immune evasion. The bottom panel outlines the intracellular life cycle of KFDV and highlights candidate stages for therapeutic intervention. (1) Viral attachment and entry occur via receptor-mediated endocytosis, facilitated by clathrin-coated vesicles. (2) Acidification of the endosome triggers viral uncoating and genome release into the cytoplasm. (3) The viral RNA is translated and processed to form the replication complex, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). (4) Host MAPK signaling pathways are co-opted to enhance viral transcription. (5) Structural proteins undergo post-translational modifications and are assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (6) Mature virions bud off through vacuolar transport. Red inhibitory bars indicate putative antiviral drug targets at critical stages of the viral replication cycle, including entry, genome release, RNA replication, protein processing, and virion assembly.

Figure 3.

Genome organization and replication cycle of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV) with potential antiviral targets. The top panel illustrates the genomic structure of KFDV, a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, comprising a single open reading frame flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). The genome encodes three structural proteins—capsid (C), membrane (M), and envelope (E)—followed by seven non-structural (NS) proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5), involved in replication and immune evasion. The bottom panel outlines the intracellular life cycle of KFDV and highlights candidate stages for therapeutic intervention. (1) Viral attachment and entry occur via receptor-mediated endocytosis, facilitated by clathrin-coated vesicles. (2) Acidification of the endosome triggers viral uncoating and genome release into the cytoplasm. (3) The viral RNA is translated and processed to form the replication complex, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). (4) Host MAPK signaling pathways are co-opted to enhance viral transcription. (5) Structural proteins undergo post-translational modifications and are assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (6) Mature virions bud off through vacuolar transport. Red inhibitory bars indicate putative antiviral drug targets at critical stages of the viral replication cycle, including entry, genome release, RNA replication, protein processing, and virion assembly.

Several gaps hinder a full understanding of KFDV’s molecular pathogenesis. First, the functional impact of E protein mutations on tropism and virulence requires in vitro and in vivo validation. Second, the lack of immunocompromised mouse models (e.g., AG129) for KFDV limits studies of IFN-dependent pathogenesis and antiviral testing. Third, long-term sequelae, such as neurological deficits, are poorly characterized, with no data on persistent infection or immune memory. Fourth, the role of host genetic factors in disease susceptibility is unexplored. Future research should prioritize high-resolution structural studies of KFDV proteins, single-cell RNA sequencing of infected tissues, and development of KFDV-specific animal models to elucidate molecular mechanisms and inform therapeutic design.

Therapeutic Options for KFDV

KFDV currently lacks specific antiviral therapies, leaving supportive care as the cornerstone of clinical management. Under this section, we review the state of KFDV therapeutics, status of repurposed drugs with potential efficacy, identifies challenges, and proposes future directions to address this critical gap in KFDV control.

Current Status

Till date, no FDA-approved or clinically validated antiviral agents target KFDV. Management relies on symptomatic treatment, including hydration, antipyretics, and, in severe cases, blood transfusions or intensive care for hemorrhagic or neurological complications. With a case fatality rate of 3–5% and biphasic progression of the disease underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions, particularly given >900 cases reported in last five years (2019–2024) across India. The absence of specific therapeutics exacerbates public health challenges, especially in endemic regions like Shivamogga and Chikkamagaluru districts of Karnataka state, where outbreaks persist despite vaccination efforts.

Repurposed Drugs

Given the lack of KFDV-specific drug development, repurposing of existing antivirals offers a promising strategy. Several candidates have been explored or hypothesized based on activity against related flaviviruses (

Table 1):

NITD008: A nucleoside analog inhibitor, NITD008 demonstrated

in vitro activity against KFDV and other flaviviruses like dengue (DENV) and Zika by blocking RNA synthesis [

21]. However, preclinical toxicity in animal models halted further development [

43] highlighting the need for safer analogs.

Favipiravir and Sofosbuvir: Broad-spectrum antivirals effective against RNA viruses, including Ebola [

44] and hepatitis C [

45], have shown

in vitro efficacy against flaviviruses [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. While not tested specifically for KFDV, their mechanisms (RNA polymerase inhibition-[

50]) suggest potential, warranting investigation in KFDV models.

Niclosamide: An FDA-approved anthelmintic, Niclosamide has demonstrated antiviral activity against DENV in both

in vitro and

in vivo, reducing viral replication and viremia [

51]. Although no studies have evaluated Niclosamide against KFDV, its ability to inhibit flavivirus replication via autophagy induction [

52] and NS2B-NS3 protease disruption [

53] makes it a candidate for repurposing. Clinical trials would be required to assess the KFDV efficacy and safety.

Monoclonal Antibodies: Neutralizing antibodies targeting the KFDV envelope protein could mitigate severe disease, as seen with DENV [

54]. However, no KFDV-specific monoclonal antibodies are in development, and cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses may poses a risk.

Table 1.

Drug candidate for therapeutics.

Table 1.

Drug candidate for therapeutics.

| Drug Name |

Mechanism of Action |

Evidence of Activity |

Current Status |

Notes for KFDV Potential |

| NITD008 |

Nucleoside analog; inhibits RNA synthesis |

In vitro activity against KFDV, DENV, Zika [21,43,55] |

Preclinical; discontinued due to toxicity |

Demonstrated KFDV inhibition; safer analogs needed; AG129 model testing pending. |

| Favipiravir |

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor |

In vitro/vivo activity against Ebola, DENV [56,57] |

Clinically approved (e.g., influenza); not tested for KFDV |

Broad-spectrum; potential for KFDV NS5 targeting; clinical trials required. |

| Sofosbuvir |

NS5B polymerase inhibitor |

In vitro activity against HCV, DENV [45,58] |

Clinically approved (HCV); not tested for KFDV |

Flavivirus cross-reactivity possible; in vivo KFDV studies needed. |

| Niclosamide |

Induces autophagy; inhibits NS2B-NS3 protease |

In vitro and in vivo activity[51]against DENV and SARS-CoV-2 [59] |

FDA-approved (anthelmintic); not tested for KFDV |

Promising for KFDV due to flavivirus similarity; AG129 model adaptation suggested. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies |

Neutralizes E protein; blocks viral entry |

Effective in DENV passive immunization [54] |

Preclinical/early clinical for DENV; none for KFDV |

KFDV-specific antibodies needed; risk of cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses. |

Challenges to develop therapeutics for KFDV

Several obstacles hinder therapeutic advancement for KFDV. First, the lack of validated animal models limits preclinical testing. While AG129 mice are widely used for DENV and Zika, till date no studies have adapted this model for KFDV, leaving uncertainty about IFN-dependent pathogenesis and drug efficacy. Second, high-throughput screening for KFDV-specific antivirals is constrained by limited funding and research focus compared to other flaviviruses. Third, the biphasic nature of KFD, with neurological complications in 10–20% of cases, complicates therapeutic timing and delivery. Finally, the geographic isolation of endemic areas (e.g., Western Ghats) and lack of infrastructure pose logistical barriers to clinical trials and vaccination.

To address these challenges, a multifaceted approach is needed. First, developing KFDV-specific animal models, such as AG129 or IFNAR

-/- mice, would enable rigorous testing of repurposed drugs like Niclosamide, Flavipiravir, and Sofosbuvir. Second, high-throughput screening of existing approved antiviral libraries, targeting KFDV NS3, NS5 and E proteins, could identify novel candidates. Third, combination therapies—pairing nucleoside analogs with monoclonal antibodies—may enhance efficacy and reduce resistance, as demonstrated in DENV studies [

60,

61]. Fourth, leveraging computational drug discovery (e.g., molecular docking of KFDV NS3 protease, helicase and NS5 RdRp inhibitors) could accelerate lead identification. Finally, clinical trials in endemic regions, supported by portable diagnostic tools, are essential to validate efficacy and ensure accessibility. Collaborative efforts under a One Health framework, integrating human, animal, and environmental data, could streamline therapeutic development and deployment.

In brief, the absence of specific therapeutics for KFDV remains a critical barrier to controlling its spread, with supportive care insufficient for severe cases. Repurposed drugs like NITD008 and potential candidates like Niclosamide and Favipiravir offer hope, but their efficacy against KFDV requires validation. Overcoming challenges through advanced models, screening platforms, and clinical trials will be pivotal. As geographic range of KFDV expands, investing in therapeutic research is imperative to reduce morbidity and mortality, complementing ongoing vaccine and diagnostic efforts.

Vaccines

Despite the availability of a formalin-inactivated vaccine, its limited efficacy has fueled research into novel vaccine candidates. This section reviews the current vaccine, emerging technologies, challenges, and future directions to enhance KFDV immunization strategies.

Available Vaccine for KFDV

The formalin-inactivated KFDV vaccine, developed in India and administered since the 1960s, remains the primary preventive measure. It is produced from mouse brain-passaged virus and requires two doses (prime and booster) followed by annual revaccination (annual booster). Studies [

14,

62] reported 62.4% efficacy with two doses and 82.9% with boosters, based on historical outbreak data. However, its performance wanes over time, with seroconversion rates dropping to 30–40% within a year [

14,

63], contributing to persistent outbreaks (>150 cases in 2023). Besides its efficacy, production challenges, including inconsistent antigen yield and reliance on mouse brains, have led to supply shortages, notably prompting its suspension in Karnataka in October 2022. Vaccine hesitancy, driven by perceived low efficacy and mild side effects (e.g., fever, local swelling), further limits coverage in endemic regions like Shivamogga and Chikkamagaluru district of Karnataka.

Novel Vaccine Candidates

Recent advancements have introduced promising alternatives to address these shortcomings:

Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV)-Based Vaccine: Bhatia et al., 2023 have developed a recombinant VSV vector expressing the KFDV envelope protein, demonstrating complete protection in BALB/c mice against lethal challenge. The vaccine elicited robust humoral immunity, with neutralizing antibodies detectable within 14 days. Further the same group (Bhatia et al., 2023) extended these findings in non-human primates (pigtailed macaques), showing reduced viral loads, no severe disease, and cross-protection against Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus (AHFV), a KFDV variant. This platform showed rapid production of vaccine candidate and established safety profile (also used in Ebola vaccines [

73]) making it a leading candidate for clinical translation.

Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine: Arumugam et al., 2021 employed an in-silico approach to design a subunit vaccine targeting conserved epitopes on the KFDV envelope protein. The candidate, predicted to bind Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2), induced strong B- and T-cell responses in silico and showed potential cross-protection against AHFV. While not yet tested in vivo, its computational optimization suggests a cost-effective, scalable option to develop a multi-epitope vaccine for KFDV.

Other Platforms: mRNA and live-attenuated vaccines, successful for other flaviviruses (e.g., Zika), have not been explored for KFDV. These platforms could offer rapid development and adaptability to emerging strains, but require significant investment to develop a vaccine for KFDV.

Table 2.

Vaccine candidates for KFDV.

Table 2.

Vaccine candidates for KFDV.

| Vaccine Name |

Platform/Technology |

Evidence of Efficacy |

Current Status |

Notes for KFDV Potential |

| Formalin-Inactivated Vaccine |

Inactivated whole virus (mouse brain-derived) |

62.4% efficacy (2 doses), 82.9% (with boosters) [14,62] |

In use since 1960s; suspended in 2022 |

Partial protection; waning immunity; production challenges; booster dependency. |

| VSV-Based Vaccine |

Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) expressing KFDV E protein |

100% protection in BALB/c mice [16]; reduced viral load in macaques [15]; cross-protects against AHFV |

Preclinical (mice, macaques) |

Promising efficacy and safety; Phase I/II trials needed; scalable production is potential. |

| Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine |

Recombinant subunit (in-silico designed E protein epitopes) |

Strong B/T-cell responses predicted in silico; binds TLR-2 [18] |

Preclinical (in silico) |

Cost-effective; in vivo validation pending; potential AHFV cross-protection. |

| mRNA Vaccine |

mRNA encoding KFDV antigens |

Effective for Zika, SARS-CoV-2 [64,65,66] |

None of the study done for KFDV |

Rapid development potential; adaptable to strains; requires KFDV-specific design. |

| Live-Attenuated Vaccine |

Attenuated KFDV strain |

Successful for yellow fever [67] 2017, DENV [68] |

Not developed for KFDV |

Could induce robust immunity; safety concerns need addressing; preclinical testing needed. |

Challenges for KFDV vaccination and development

Several obstacles impede KFDV vaccine progress. First, the current vaccine’s suboptimal efficacy and production issues highlight the need for standardized immunogenicity assays and scalable manufacturing. Second, limited clinical trial data—most studies are preclinical—delays regulatory approval and deployment. Third, the biphasic nature of KFDV, with neurological complications in 10–20% of cases, complicates vaccine safety assessments, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Fourth, geographic and logistical barriers in endemic Western Ghats regions hinder vaccine distribution and monitoring. Finally, the lack of a correlate of protection (e.g., specific antibody titers) complicates efficacy evaluation, as seen with the formalin-inactivated vaccine’s variable performance.

To overcome these challenges, a multifaceted strategy is essential. First, advancing the VSV-based vaccine to Phase I/II clinical trials in endemic populations (e.g., Karnataka, Kerala) is a priority, leveraging its cross-protective potential against AHFV. Second, validating the multi-epitope subunit vaccine in animal models (e.g., bonnet macaques) and initiating human trials could diversify options. Third, exploring mRNA or live-attenuated platforms, tailored to KFDV’s genetic diversity, could enhance adaptability. Fourth, integrating vaccine development with One Health approaches—such as immunizing nonhuman primates (e.g., red-faced bonnet monkeys) to reduce zoonotic reservoirs—could amplify herd immunity. Fifth, establishing long-term immunogenicity studies and correlates of protection will guide booster schedules and efficacy benchmarks. Finally, public health campaigns addressing hesitancy, supported by real-world evidence from trials, are critical to ensure uptake.

In nutshell, the formalin-inactivated KFDV vaccine provides partial protection but falls short of controlling outbreaks, necessitating innovative alternatives. The VSV-based and multi-epitope subunit vaccines represent significant progress, with potential for clinical impact. Addressing production, safety, and distribution challenges through advanced platforms and integrated strategies will be key. As KFDV’s geographic range expands, accelerating vaccine development is vital to reduce the disease burden, complementing efforts in therapeutics and diagnostics.

Diagnostics

Accurate and timely diagnosis of KFDV is essential to manage its rapidly spreading cases across India, particularly in endemic regions like Karnataka’s Shivamogga and Chikkamagaluru districts. With a 3–5% case fatality rate and potential for neurological complications in 10–20% of cases, effective diagnostics are critical to guide treatment and control outbreaks. This section reviews current diagnostic tools, recent advancements, challenges, and future directions to enhance KFDV detection.

Current Diagnostic Tools

The gold standard for KFDV diagnosis is reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which detects viral RNA in serum or tissue during the acute phase (days 3–8 post-infection). Yadav et al., 2023, standardized a dry-down RT-PCR assay targeting the KFDV envelope gene, offering high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (98%) for early detection. This method is particularly useful in field settings but requires trained personnel and laboratory infrastructure. Serological assays, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), complement RT-PCR by detecting IgM and IgG antibodies. Rajak et al., 2022, highlighted the development of a recombinant envelope domain III (EDIII)-based ELISA, achieving 92% sensitivity and 94% specificity for IgM detection within 5–7 days post-onset, aiding diagnosis in the second disease phase. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), based on antigen detection, are under development but lack validation for KFDV.

Below is a proposed table summarizing diagnostic methods for KFDV.

Table 3.

Diagnostic Methods for KFDV.

Table 3.

Diagnostic Methods for KFDV.

| Diagnostic methods |

Technique |

Detection Target |

Sensitivity/Specificity |

Current Status |

Notes on Limitations and Potential Improvements |

| RT-PCR (Standard) |

Reverse transcription PCR |

Viral RNA (envelope gene) |

~95% / ~98% [69] |

Routine in labs |

Limited to viremic phase (days 3–8); requires infrastructure; dry-down version improves field use. |

| Dry-Down RT-PCR |

Lyophilized RT-PCR |

Viral RNA (envelope gene) |

~95% / ~98% [22] |

Emerging (field testing) |

Reduces turnaround to 4–6 hours; needs validation in remote settings; scalable production needed. |

| ELISA (IgM/IgG) |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

IgM/IgG antibodies |

~92% / ~94% (IgM) [70] |

Routine in labs |

Cross-reactivity with flaviviruses; delayed detection (days 5–14); enhance with recombinant antigens. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

High-throughput sequencing |

Whole viral genome |

Variable (research-grade [71] |

Research tool |

Costly and complex; not routine; potential for AI integration to track strains. |

| Point-of-Care (POC) Devices |

Lateral flow or RT-PCR-based |

KFDV Antigens or RNA |

Under validation (~90% est.;[72] |

Prototypes (development) |

Limited validation; needs thermostable, affordable design for rural deployment. |

Challenges in KFDV diagnosis

Several limitations hinder KFDV diagnostics. First, the narrow diagnostic window—RT-PCR is effective only during viremia phase (days 3–8), while ELISA relies on seroconversion (days 5–14)—misses cases outside these phases, contributing to underreporting (e.g., asymptomatic infections in Kerala). Second, infrastructure deficits in rural areas, such as lack of cold chains for reagents and trained staff, restrict RT-PCR and ELISA use. Third, cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses remains a challenge, particularly in ELISA, complicating differential diagnosis in co-endemic regions. Fourth, the cost and complexity of NGS limit its scalability for routine surveillance. Finally, the biphasic nature of KFDV, with neurological symptoms emerging later, delays suspicion and testing.

To address these challenges, several advancements are needed. First, developing multiplex RT-PCR or POC assays that differentiate KFDV from dengue, Zika, and Japanese encephalitis would enhance specificity and speed. Second, scaling up dry-down RT-PCR and validating POC devices for field use particularly in endemic region, and other potential affected states could reduce diagnostic delays. Third, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with NGS data could improve strain tracking and predict outbreak hotspots. Fourth, affordable, thermostable RDTs targeting KFDV antigens or antibodies are essential for rural deployment, potentially leveraging lateral flow technology. Fifth, establishing standardized diagnostic algorithms—combining RT-PCR, ELISA, and serology—would optimize case detection across disease phases. Finally, training programs for local health workers and mobile diagnostic units could bridge infrastructure gaps, supporting a One Health surveillance framework.

Conclusion

Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV) remains a significant public health challenge, with approximately 900 cases reported across India from 2019–2024, predominantly in Karnataka’s Shivamogga and Chikkamagaluru regions, and emerging in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Maharashtra. Its 3–5% case fatality rate and neurological complications in 10–20% of cases underscore the disease’s severity, driven by expanding geographic range and climate-induced tick proliferation. This review highlights critical insights: epidemiology reveals persistent outbreaks despite vaccination; pathogenesis elucidates molecular mechanisms yet lacks robust models; therapeutics remain limited to supportive care with promising repurposed candidates; vaccines show progress with VSV-based and subunit options but require clinical validation; and diagnostics advance with dry-down RT-PCR yet face timing and infrastructure barriers.

The gaps—underreporting, absence of KFDV-specific antivirals, suboptimal vaccine efficacy, and diagnostic delays—demand urgent action. Integrated strategies under a One Health framework, combining enhanced surveillance, drug repurposing, next-generation vaccines (e.g., mRNA), and field-deployable diagnostics, are essential. Collaborative efforts across research, policy, and community levels can accelerate progress, particularly in endemic Western Ghats regions. As potential risk for KFDV global spread grows, investing in these areas will mitigate its burden and inform control of other tick-borne flaviviruses. This review calls for immediate, multidisciplinary action to transform KFDV from an emerging threat into a manageable disease.

Discussion and Future Directions

KFDV has emerged as a persistent threat, with approximately 700–900 cases reported across India from 2019–2024 [

31], predominantly in Shivamogga and Chikkamagaluru districts of Karnataka, and expanding into Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Maharashtra. KFDV expansion raises the potential risk for neighboring states, like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Madhya Pradesh. This review consolidates critical insights into its epidemiology, pathogenesis, therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics, revealing both progress and significant gaps that demand urgent attention.

Epidemiologically, KFDV’s geographic spread, driven by deforestation and climate factors (e.g., heat, low rainfall, humidity), highlights the need for robust surveillance. The 3–5% case fatality rate and neurological complications in 10–20% of cases underscore the disease’s severity, with underreporting (e.g., asymptomatic cases in Kerala) complicating incidence estimates. Molecular pathogenesis reveals key mechanisms, such as NS5-mediated interferon suppression and adaptive E protein mutations, yet lacks validated immunocompromised models (e.g., AG129 mice) to explore host-pathogen dynamics fully. Therapeutically, the absence of specific antivirals leaves supportive care as the mainstay, with repurposed candidates like Niclosamide (effective against dengue) untested for KFDV. Vaccines show promise with the VSV-based and multi-epitope subunit approaches, offering protection in preclinical models, but 62.4% efficacy of the formalin-inactivated vaccine limits outbreak control. Diagnostics have advanced with dry-down RT-PCR, reducing turnaround to 4–6 hours, yet infrastructure and cross-reactivity challenges persist.

Research Gaps

Several gaps hinder KFDV management. In epidemiology, inconsistent surveillance (e.g., 2–16 day testing delays) and lack of standardized seroprevalence data obscure the true burden. Pathogenesis studies are constrained by the absence of KFDV-specific animal models, limiting insights into neuroinvasiveness and long-term sequelae. Therapeutics lack high-throughput screening and clinical trials, with no data on drug efficacy in endemic populations. Vaccine development requires clinical validation and correlates of protection, while diagnostics need multiplex assays to differentiate KFDV from co-endemic flaviviruses. These gaps collectively impede a cohesive response to KFDV’s rising incidence.

Future Directions

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach. For epidemiology, implementing real-time surveillance systems with mobile diagnostic units and standardized reporting can enhance case detection, particularly in rural Western Ghats regions. Pathogenesis research should prioritize developing AG129 or IFNAR-/- mouse models to elucidate IFN-dependent mechanisms and test therapeutic candidates. Therapeutics can advance through repurposing drugs (e.g., Niclosavir, Favipiravir) via high-throughput screens targeting NS2B-NS3 protease, NS3 helicase, NS5 and E proteins, followed by Phase I/II trials in endemic areas. Vaccine development should accelerate the VSV-based candidate to clinical trials, explore mRNA platforms for strain adaptability, and integrate primate immunization to reduce zoonotic reservoirs. Diagnostics need investment in affordable, thermostable POC devices and AI-enhanced NGS for outbreak prediction, that lead to phylogeographic studies. A One Health framework, linking human, animal (e.g., red-faced bonnet monkeys), and environmental data, can streamline these efforts, supported by community education to address vaccine hesitancy.

Global Implications and Integrated Strategies

KFDV has potential risk for cross-border spread, as seen with Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus, positions it as a model for tick-borne flavivirus control. Climate-driven tick dispersal and deforestation amplify this risk, necessitating international collaboration. Integrated strategies—combining enhanced surveillance, drug and vaccine pipelines, and diagnostic innovation—can transform KFDV management. Policymakers must prioritize funding and infrastructure, while researchers focus on translational research to bridge preclinical and clinical gaps. As KFDV burden grows, this holistic approach will not only mitigate its impact in India but also inform global responses to emerging flaviviral threats.

Author Contributions

BB: Data curation; investigation, writing the first draft. KSS: Data curation; formal analysis; review & editing of the original draft. AR: Data curation; review & editing of the original draft. NP: Review & editing of the original draft. RS: Conceptualization; supervision; project administration; Resources; funding acquisition; validation; review & editing of the original draft. All authors have agreed to the final manuscript.

Funding

The CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI) provided internal funding support (IHP058) to Rahul Shukla (R.S.) for carrying out this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge to Dr. Radha Rangarajan, Director, CSIR-CDRI, for providing the necessary funding and institutional support to carry out this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Work Th, Trapido H, Murthy Dp, Rao Rl, Bhatt Pn, Kulkarni Kg. Kyasanur forest disease. III. A preliminary report on the nature of the infection and clinical manifestations in human beings. Indian J Med Sci. 1957;11(8):619-645.

- Work Th. Russian spring-summer virus in India: Kyasanur Forest disease. Prog Med Virol. 1958;1:248-279.

- Trapido H, Rajagopalan Pk, Work Th, Varma Mg. Kyasanur Forest disease. VIII. Isolation of Kyasanur Forest disease virus from naturally infected ticks of the genus Haemaphysalis. Indian J Med Res. 1959;47(2):133-138.

- Ocular manifestations of Kyasanur forest disease (a clinical study). Indian J Ophthalmol. 1983;31(5):700-702.

- Wadia RS. Neurological involvement in Kyasanur Forest Disease. Neurol India. 1975;23(3):115-120.

- Muraleedharan M. Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD): Rare Disease of Zoonotic Origin. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2016;14(34):214-218.

- Chakraborty S, Andrade FCD, Ghosh S, Uelmen J, Ruiz MO. Historical Expansion of Kyasanur Forest Disease in India From 1957 to 2017: A Retrospective Analysis. Geohealth. 2019;3(2):44-55. Published 2019 Feb 5. [CrossRef]

- N, Srilekha et al. “Kyasanur Forest Disease: A Comprehensive Review.” Cureus vol. 16,7 e65228. 23 Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Amogh Verma, Ayush Anand, Ajeet Singh, Abhinav Khare, Ahmad Neyazi, Sarvesh Rustagi, Neelima Kukreti, Abhay M Gaidhane, Quazi Syed Zahiruddin, Prakasini Satapathy, Kyasanur Forest Disease: Clinical manifestations and molecular dynamics in a zoonotic landscape, Clinical Infection in Practice, Volume 21, 2024, 100352, ISSN 2590-1702, .

- Ajesh K, Nagaraja BK, Sreejith K. Kyasanur forest disease virus breaking the endemic barrier: An investigation into ecological effects on disease emergence and future outlook. Zoonoses Public Health. 2017;64(7):e73-e80. [CrossRef]

- Purse BV, et al. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: A review of the evidence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2020; 375:20180362.

- Pattnaik S, Agrawal R, Murmu J, Kanungo S, Pati S. Does the rise in cases of Kyasanur forest disease call for the implementation of One Health in India?. IJID Reg. 2023;7:18-21. Published 2023 Feb 12. [CrossRef]

- Dandawate CN, Desai GB, Achar TR, Banerjee K. Field evaluation of formalin inactivated Kyasanur forest disease virus tissue culture vaccine in three districts of Karnataka state. Indian J Med Res. 1994;99:152-158.

- Kasabi GS, Murhekar MV, Sandhya VK, et al. Coverage and effectiveness of Kyasanur forest disease (KFD) vaccine in Karnataka, South India, 2005-10. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(1):e2025. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia B, Tang-Huau TL, Feldmann F, et al. Single-dose VSV-based vaccine protects against Kyasanur Forest disease in nonhuman primates. Sci Adv. 2023;9(36):eadj1428. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia B, Meade-White K, Haddock E, Feldmann F, Marzi A, Feldmann H. A live-attenuated viral vector vaccine protects mice against lethal challenge with Kyasanur Forest disease virus. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):152. Published 2021 Dec 14. [CrossRef]

- Das M, Kumar V, Madhukalya R, et al. Purification and characterization of kyasanur forest disease virus EDIII domain of major envelope glycoprotein. J Virol Methods. 2025;333:115089. [CrossRef]

- Arumugam S, Varamballi P. In-silico design of envelope based multi-epitope vaccine candidate against Kyasanur forest disease virus. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17118. Published 2021 Aug 24. [CrossRef]

- Kasibhatla SM, Rajan L, Shete A, et al. Construction of an immunoinformatics-based multi-epitope vaccine candidate targeting Kyasanur forest disease virus. PeerJ. 2025;13:e18982. Published 2025 Mar 21. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S. B., Jeyachandran, A., Pariyapurath, N. K., Jagadibabu, S., Rajaiah, P., Channappa, S. K., Pachamuthu, R. G., Premkumar, A. A., & Jagannathan, S. (2025). Advancements in Vaccine Development : A comprehensive design of a Multi-Epitopic Immunodominant Peptide Vaccine Targeting Kyasanur Forest Disease via Reverse Vaccinology. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). [CrossRef]

- Lo MK, Shi PY, Chen YL, Flint M, Spiropoulou CF. In vitro antiviral activity of adenosine analog NITD008 against tick-borne flaviviruses. Antiviral Res. 2016;130:46-49. [CrossRef]

- Yadav P, Sharma S, Dash PK, Dhankher S, V K S, Kiran SK. Dry- down probe free qPCR for detection of KFD in resource limited settings. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0284559. Published 2023 May 10. [CrossRef]

- Hasan S, et al. Advances in multiplex diagnostics for arboviruses. Emerg Infect Dis 2025; 31:in press.

- Pramanik P, et al. Climate-driven changes in tick-borne disease risk. J Med Entomol 2021; 58:1234–1242.

- Pattnaik P. Kyasanur forest disease: an epidemiological view in India [published correction appears in Rev Med Virol. 2008 May-Jun;18(3):211]. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16(3):151-165. [CrossRef]

- Munivenkatappa, Ashok et al. “Clinical & epidemiological significance of Kyasanur forest disease.” The Indian journal of medical research vol. 148,2 (2018): 145-150. [CrossRef]

- Rajaiah P. Kyasanur Forest Disease in India: innovative options for intervention. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(10):2243-2248. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian R, Yadav PD, Sahina S, Nadh VA. The species distribution of ticks & the prevalence of Kyasanur forest disease virus in questing nymphal ticks from Western Ghats of Kerala, South India. Indian J Med Res. 2021;154(5):743-749. [CrossRef]

- Vedachalam SK, Rajput BL, Choudhary S, et al. Kyasanur Forest Disease: An Epidemiological Investigation and Case-Control Study in Shivamogga, Karnataka, India-2022. Int J Public Health. 2024;69:1606715. Published 2024 Oct 18. [CrossRef]

- Vedachalam, S.K., Rajput, B.L., Choudhary, S. et al. Descriptive epidemiology of Kyasanur forest disease in Thirthahalli taluk, Shivamogga, Karnataka, 2018–2022. Discov Public Health 22, 130 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty S, Sander W, Allan BF, Andrade FCD. Sociodemographic factors associated with Kyasanur forest disease in India - a retrospective study. IJID Reg. 2024;10:219-227. Published 2024 Feb 15. [CrossRef]

- Bhat HR, Naik SV. Transmission of Kyasanur forest disease virus by Haemaphysalis wellingtoni Nuttall and Warburton, 1907 (Acarina : Ixodidae). Indian J Med Res. 1978;67(5):697-703.

- Zhang C, Li Y, Samad A, et al. Kyasanur Forest disease virus NS3 helicase: Insights into structure, activity, and inhibitors. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;254(Pt 3):127856. [CrossRef]

- Cook BW, Cutts TA, Court DA, Theriault S. The generation of a reverse genetics system for Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus and the ability to antagonize the induction of the antiviral state in vitro. Virus Res. 2012;163(2):431-438. [CrossRef]

- Cook BW, Ranadheera C, Nikiforuk AM, et al. Limited Effects of Type I Interferons on Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus in Cell Culture. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(8):e0004871. Published 2016 Aug 1. [CrossRef]

- Sirmarova J, Salat J, Palus M, et al. Kyasanur Forest disease virus infection activates human vascular endothelial cells and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7(1):175. Published 2018 Nov 7. [CrossRef]

- Sawatsky B, McAuley AJ, Holbrook MR, Bente DA. Comparative pathogenesis of Alkhumra hemorrhagic fever and Kyasanur forest disease viruses in a mouse model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(6):e2934. Published 2014 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.R., Yadav, P.D., Shete, A. et al. Study of Kyasanur forest disease viremia, antibody kinetics, and virus infection in target organs of Macaca radiata. Sci Rep 10, 12561 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Robertson SJ, Mitzel DN, Taylor RT, Best SM, Bloom ME. Tick-borne flaviviruses: dissecting host immune responses and virus countermeasures. Immunol Res. 2009;43(1-3):172-186. [CrossRef]

- Avirutnan P, Hauhart RE, Somnuke P, Blom AM, Diamond MS, Atkinson JP. Binding of flavivirus nonstructural protein NS1 to C4b binding protein modulates complement activation. J Immunol. 2011;187(1):424-433. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Maguire T, Hileman RE, et al. Dengue virus infectivity depends on envelope protein binding to target cell heparan sulfate. Nat Med. 1997;3(8):866-871. [CrossRef]

- Kroschewski H, Allison SL, Heinz FX, Mandl CW. Role of heparan sulfate for attachment and entry of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Virology. 2003;308(1):92-100. [CrossRef]

- Yin Z., Chen Y.-L., Schul W., Wang Q.-Y., Gu F., Duraiswamy J., Kondreddi R.R., Niyomrattanakit P., Lakshminarayana S.B., Goh A. An adenosine nucleoside inhibitor of dengue virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:20435–20439. [CrossRef]

- Bixler SL, Bocan TM, Wells J, et al. Efficacy of favipiravir (T-705) in nonhuman primates infected with Ebola virus or Marburg virus. Antiviral Res. 2018;151:97-104. [CrossRef]

- Keating G. M. (2014). Sofosbuvir: a review of its use in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Drugs 74, 1127–1146. [CrossRef]

- Marlin, R., Desjardins, D., Contreras, V. et al. Antiviral efficacy of favipiravir against Zika and SARS-CoV-2 viruses in non-human primates. Nat Commun 13, 5108 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Morrey J, Taro B, Siddharthan V, et al. Efficacy of orally administered T-705 pyrazine analog on lethal West Nile virus infection in rodents. Antiviral Res 2008; 80: 377–379.

- Julander JG, Shafer K, Smee DF, et al. Activity of T-705 in a hamster model of yellow fever virus infection in comparison with that of a chemically related compound, T-1106. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 202–209.

- Ferreira ACReis PA, de Freitas CSSacramento CQVillas Bôas Hoelz L, Bastos MM, Mattos MRocha NGomes de Azevedo Quintanilha I, da Silva Gouveia Pedrosa C, Rocha Quintino Souza L, Correia Loiola E, Trindade P, Rangel Vieira YBarbosa-Lima G, de Castro Faria Neto HC, Boechat N, Rehen SKBrüning K, Bozza FABozza PT, Souza TML 2019. Beyond Members of the Flaviviridae Family, Sofosbuvir Also Inhibits Chikungunya Virus Replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:10.1128/aac.01389-18.

- Sacramento, C., de Melo, G., de Freitas, C. et al. The clinically approved antiviral drug sofosbuvir inhibits Zika virus replication. Sci Rep 7, 40920 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kao JC, HuangFu WC, Tsai TT, et al. The antiparasitic drug niclosamide inhibits dengue virus infection by interfering with endosomal acidification independent of mTOR. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(8):e0006715. Published 2018 Aug 20. [CrossRef]

- Gassen NC, Papies J, Bajaj T, et al. SARS-CoV-2-mediated dysregulation of metabolism and autophagy uncovers host-targeting antivirals. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3818. Published 2021 Jun 21. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Brecher, M., Deng, YQ. et al. Existing drugs as broad-spectrum and potent inhibitors for Zika virus by targeting NS2B-NS3 interaction. Cell Res 27, 1046–1064 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gunale B, Farinola N, Kamat CD, et al. An observer-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 1, single ascending dose study of dengue monoclonal antibody in healthy adults in Australia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24(6):639-649. [CrossRef]

- Deng YQ, Zhang NN, Li CF, et al. Adenosine Analog NITD008 Is a Potent Inhibitor of Zika Virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(4):ofw175. Published 2016 Aug 30. [CrossRef]

- Guedj J, Piorkowski G, Jacquot F, et al. Antiviral efficacy of favipiravir against Ebola virus: A translational study in cynomolgus macaques. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002535. Published 2018 Mar 27. [CrossRef]

- Franco EJ, Pires de Mello CP, Brown AN. Antiviral Evaluation of UV-4B and Interferon-Alpha Combination Regimens against Dengue Virus. Viruses. 2021;13(5):771. Published 2021 Apr 27. [CrossRef]

- Xu HT, Colby-Germinario SP, Hassounah SA, et al. Evaluation of Sofosbuvir (β-D-2'-deoxy-2'-α-fluoro-2'-β-C-methyluridine) as an inhibitor of Dengue virus replication<sup/>. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6345. Published 2017 Jul 24. [CrossRef]

- Weiss A, Touret F, Baronti C, et al. Niclosamide shows strong antiviral activity in a human airway model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and a conserved potency against the Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351) and Delta variant (B.1.617.2). PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260958. Published 2021 Dec 2. [CrossRef]

- Yeo KL, Chen YL, Xu HY, et al. Synergistic suppression of dengue virus replication using a combination of nucleoside.

- Tien SM, Chang PC, Lai YC, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of humanized monoclonal antibodies targeting dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 in the mouse model. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18(4):e1010469. Published 2022 Apr 29. [CrossRef]

- Devadiga S, McElroy AK, Prabhu SG, Arunkumar G. Dynamics of human B and T cell adaptive immune responses to Kyasanur Forest disease virus infection. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15306. Published 2020 Sep 17. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty S, Sander WE, Allan BF, Andrade FCD. Retrospective Study of Kyasanur Forest Disease and Deaths among Nonhuman Primates, India, 1957-2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(7):1969-1973. [CrossRef]

- Gote V, Bolla PK, Kommineni N, et al. A Comprehensive Review of mRNA Vaccines. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2700. Published 2023 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N., Weissman, D. & Whitehead, K.A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20, 817–838 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N., Hogan, M., Porter, F. et al. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 261–279 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Barrett ADT. Yellow fever live attenuated vaccine: A very successful live attenuated vaccine but still we have problems controlling the disease. Vaccine. 2017;35(44):5951-5955. [CrossRef]

- Kallás EG, Cintra MAT, Moreira JA, et al. Live, Attenuated, Tetravalent Butantan-Dengue Vaccine in Children and Adults. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(5):397-408. [CrossRef]

- N S, Hewson R, Afrough B, Bewley K, Arunkumar G. Development of a quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay that differentiates between Kyasanur Forest disease virus and Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11(3):101381. [CrossRef]

- Rajak A, Kumar JS, Dhankher S, et al. Development and application of a recombinant Envelope Domain III protein based indirect human IgM ELISA for Kyasanur forest disease virus. Acta Trop. 2022;235:106623. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Yadav P, Dash PK, Dhankher S. Molecular epidemiology of Kyasanur forest disease employing ONT-NGS a field forward sequencing. J Clin Virol. 2025;177:105783. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar T, Shete A, Yadav P, et al. Point of care real-time polymerase chain reaction-based diagnostic for Kyasanur forest disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;108:226-230. [CrossRef]

- Suder E, Furuyama W, Feldmann H, Marzi A, de Wit E. The vesicular stomatitis virus-based Ebola virus vaccine: From concept to clinical trials. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(9):2107-2113. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).