Submitted:

25 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

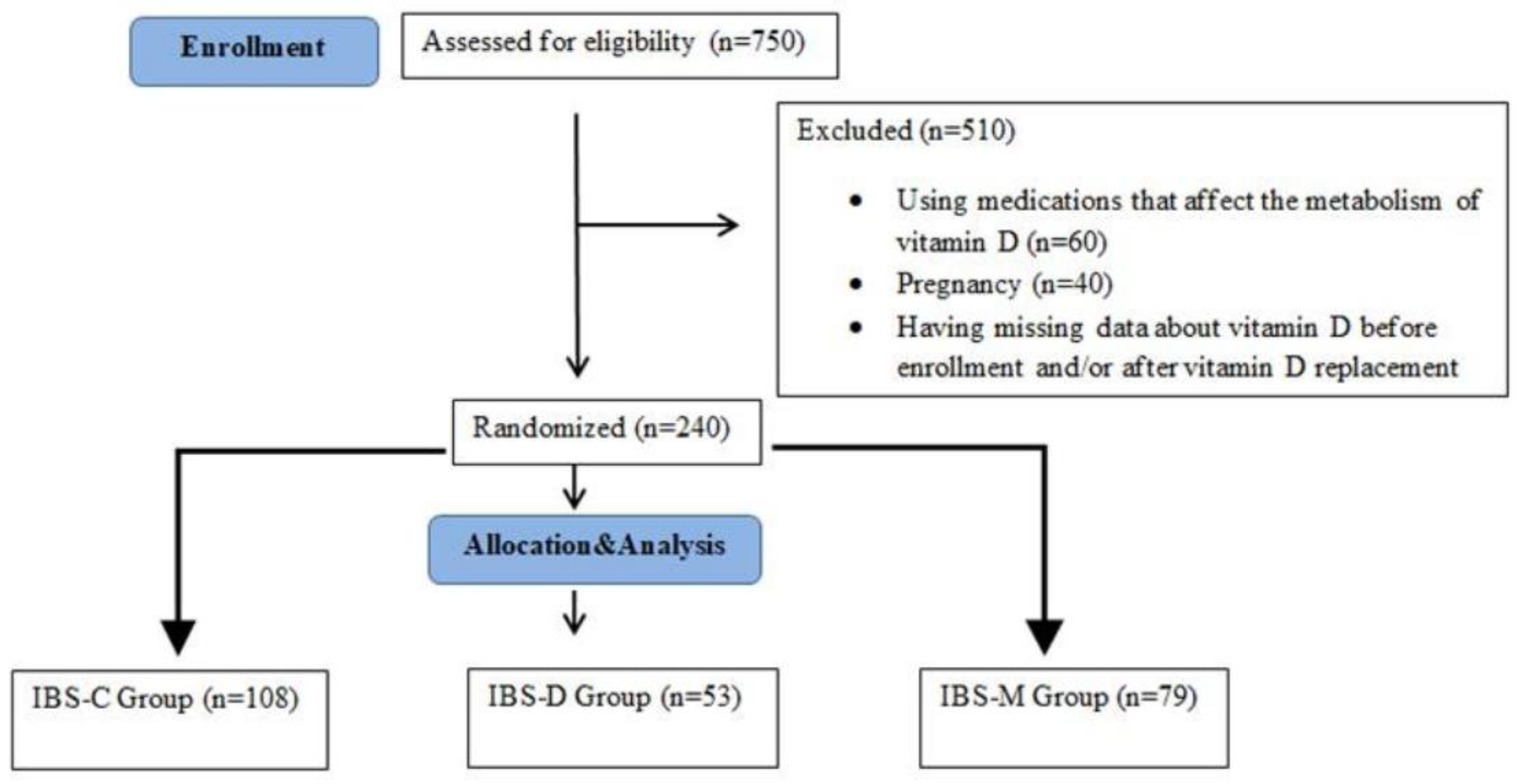

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kulie, T.; Groff, A.; Redmer, J.; Hounshell, J.; Schrager, S. Vitamin D: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2009, 22, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M. F. Vitamin D Deficiency. The New England Journal of Medicine 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, R. P.; Ames, B. N. Vitamin D Hormone Regulates Serotonin Synthesis. Part 1: Relevance for Autism. The FASEB Journal 2014, 28, 2398–2413. [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Musch, M. W.; Ning, G.; Sun, J.; Hart, J.; Bissonnette, M.; Li, Y. C. Novel Role of the Vitamin D Receptor in Maintaining the Integrity of the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier. American Journal of Physiology-gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. C.; Chen, Y.; Du, J. Critical Roles of Intestinal Epithelial Vitamin D Receptor Signaling in Controlling Gut Mucosal Inflammation. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2015, 148, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Kamal Mohamed, I.; Zaki, Z. E.; Elsayed, A. S. Clinical Correlation between Serum Vitamin D Level and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. El-Minia Medical Bulletin, 2022; 33, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shemery, M. K.; Al Kafhage, F. A.; Al-Masaoodi, R. A. Vitamin D3 And Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Review. The International Science of Health Journal 2024, 2, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E. A.; Jørgensen, T. N. Relationships Between Vitamin D, Gut Microbiome, and Systemic Autoimmunity. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 10, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J.; Park, K. S. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Emerging Paradigm in Pathophysiology. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2014, 20, 2456–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearin, F.; Lacy, B.; Chang, L.; Chey, W.; Lembo, A.; Simren, M.; Spiller, R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D. A.; Hasler, W. L. Rome IV—Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, A.; Hwang, S. K.; Padhye, N. S.; Meininger, J. C. Effects of Cognitive Behavior Therapy on Heart Rate Variability in Young Females with Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Parallel-Group Trial. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 2017, 23, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrees, D. N.; Bailey, J. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Primary Care 2017, 44, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C. J.; Ford, A. C. Global Burden of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Trends, Predictions and Risk Factors. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 17, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Demutska, A.; Chan, V.; Siah, K. T. H. Adults Living with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2021, 140, 110289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, A. Nutritional Rickets around the World. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2013, 136, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu XL, Wu QQ, He LP, Zheng YF. Role of in Vitamin D in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. World Journal of Clinical Cases 2023, 11, 2677–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseiny, A.; zamili, S.; Shala, H. Prevalence of IBS and Its Relationship to Vitamin D Deficiency in Al- Nasiriyah City, Iraq. Rawal Medical Journal 2023, 48, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyat, Y. M.; Attar, S. M. Vitamin D Deficiency in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Does It Exist? Oman Medical Journal 2015, 30, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S. W.; Plantinga, A.; Burr, R. L.; Cain, K. C.; Savidge, T. C.; Kamp, K.; Heitkemper, M. M. Exploring the Role of Vitamin D and the Gut Microbiome: A Cross-Sectional Study of Individuals with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Healthy Controls. Biological Research For Nursing 2023, 25, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicka, A. Sex Differences in Vitamin D Metabolism, Serum Levels and Action. British Journal of Nutrition 2022, 128, 2115–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, F.; Al-Mahroos, F.; Al-Sahlawi, H. S.; Al-Amer, E. A. The Impact of Dietary Intake and Sun Exposure on Vitamin D Deficiency among Couples. Bahrain medical bulletin 2014, 36, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Song, S.; Miao, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Hu, L.; Huo, M.; Zhou, Q. High Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in Urban Health Checkup Population. Clinical Nutrition 2016, 35, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix de Oliveira, C.; Vogt Cureau, F.; dos Santos Cople-Rodrigues, C.; Tavares Giannini, D.; Vergetti Bloch, K.; Caetano Kuschnir, M. C.; Baiocchi de Carvalho, K. M.; D’Agord Schaan, B. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Hypovitaminosis D in Adolescents from a Sunny Country: Findings from the ERICA Survey. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2020, 199, 105609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, P.; Liu, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. Associations of Vitamin D with Novel and Traditional Anthropometric Indices According to Age and Sex: A Cross-Sectional Study in Central Southern China. Eating and Weight Disorders-studies on Anorexia Bulimia and Obesity 2020, 25, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, Q. E.; Umbach, D. M.; Baird, D. D. Use of Estrogen-Containing Contraception Is Associated With Increased Concentrations of 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016, 101, 3370–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunova, Z.; Porojnicu, A.; Lindberg, F. A.; Hexeberg, S.; Moan, J. E. The Dependency of Vitamin D Status on Body Mass Index, Gender, Age and Season. Anticancer Research 2009, 29, 3713–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhosseiny, D.; Elfawy Mahmoud, N.; Manzour, A. F. Factors Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome among Medical Students at Ain Shams University. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association 2019, 94, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorn, S. D.; Morris, C. B.; Hu, Y.; Toner, B. B.; Diamant, N. E.; Whitehead, W. E.; Bangdiwala, S. I.; Drossman, D. A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome Subtypes Defined by Rome II and Rome III Criteria Are Similar. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2009, 43, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Western and Non-Western Populations: Prevalence, Psychological Comorbidities, Quality of Life and Role of Nutrition. Global Immunological & Infectious Diseases Review 2024, IX, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. S.; Kim, N. Sex-Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 2018, 24, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Heitkemper, M. M. Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1686–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

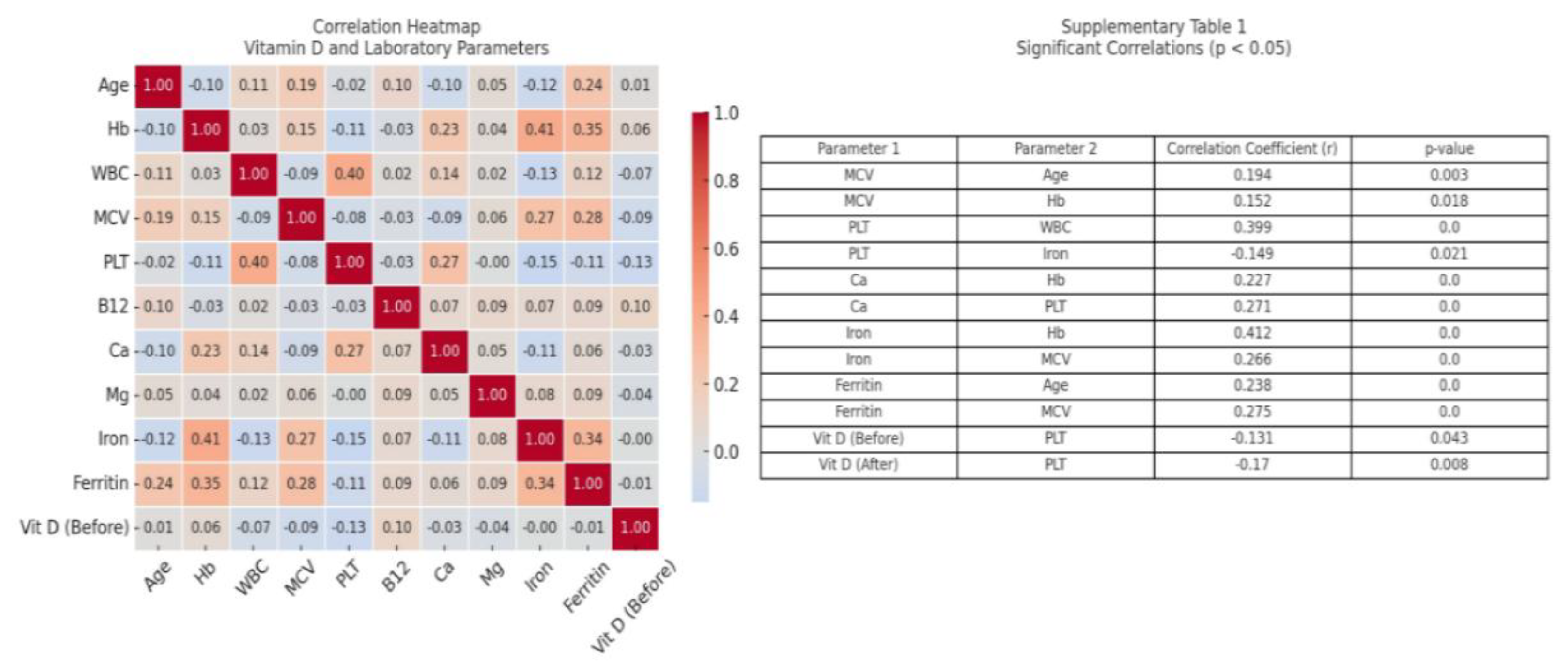

- Ergenc, Z.; Ergenç, H.; Yıldırım, İ.; Öztürk, A.; Usanmaz, M.; Karacaer, C.; Günay, S.; Kaya, G. Relationship between Vitamin D Levels and Hematological Parameters. Medical Science and Discovery 2023, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarki, A. A.; Dobie, G.; Saboor, M.; Madkhali, A. M.; Habibullah, M.; Nahari, M. H.; Kamli, H.; Hakamy, A.; Hamali, H. A. Prevalence and Correlation of Vitamin D Levels with Hematological and Biochemical Parameters in Young Adults. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science 2022, 52, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Parameter | IBS-D Group (N=53) | IBS-C Group (N=108) | IBS-M Group (N=79) | P value |

|

Gender Female |

40 |

74 |

45 |

0.488 |

| Male | 13 | 34 | 34 | |

| Age | 44 (35-57) | 46 (37-60) | 44 (30-61) | 0.598 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.2 (13.1–15.9) | 14.4 (13.4–15.8) | 14.4 (13.2–15.7) | 0.728 |

| White blood cell (x103) | 8.0 (6.59–8.89) | 7.3 (6.2–8.7) | 7.3 (6.0–9.3) | 0.114 |

| Main corpuscular volume (fL) | 84.8 (81.6–88.0) | 84.9 (83.1–89.8) | 85.9 (83.1–88.0) | 0.357 |

| Platelet (x103) | 294 (235-336) | 274 (235-316) | 280 (237-327) | 0.579 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 277 (234-378) | 315 (241-389) | 280 (237-327) | 0.163 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.53 (9.21-8.91) | 9.56 (9.21–9.80) | 9.60 (9.20–9.90) | 0.498 |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 1.96 (1.84–2.11) | 1.95 (1.85–2.11) | 1.93 (1.80-2.08) | 0.609 |

| Iron (μg/dL) | 74.1 (51.6-94.1) | 78.3 (58.3-103) | 76.0 (52.0-96.6) | 0.659 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 48.5 (18.8–85.3) | 50.6 (18.8–98.2) | 55.3 (23.0–121.8) | 0.082 |

| Vitamin D level at admission (ng/ml) | 12.0 (10.0-20.0) | 13.0 (9.01-22.0) | 11.0 (8.00-40) | 0.193 |

| Vitamin D level after 2 months (ng/ml) | 33.0 (26.0-36.0) | 32.0 (20.0-40.0) | 28.0 (18.0-40.0) | 0.652 |

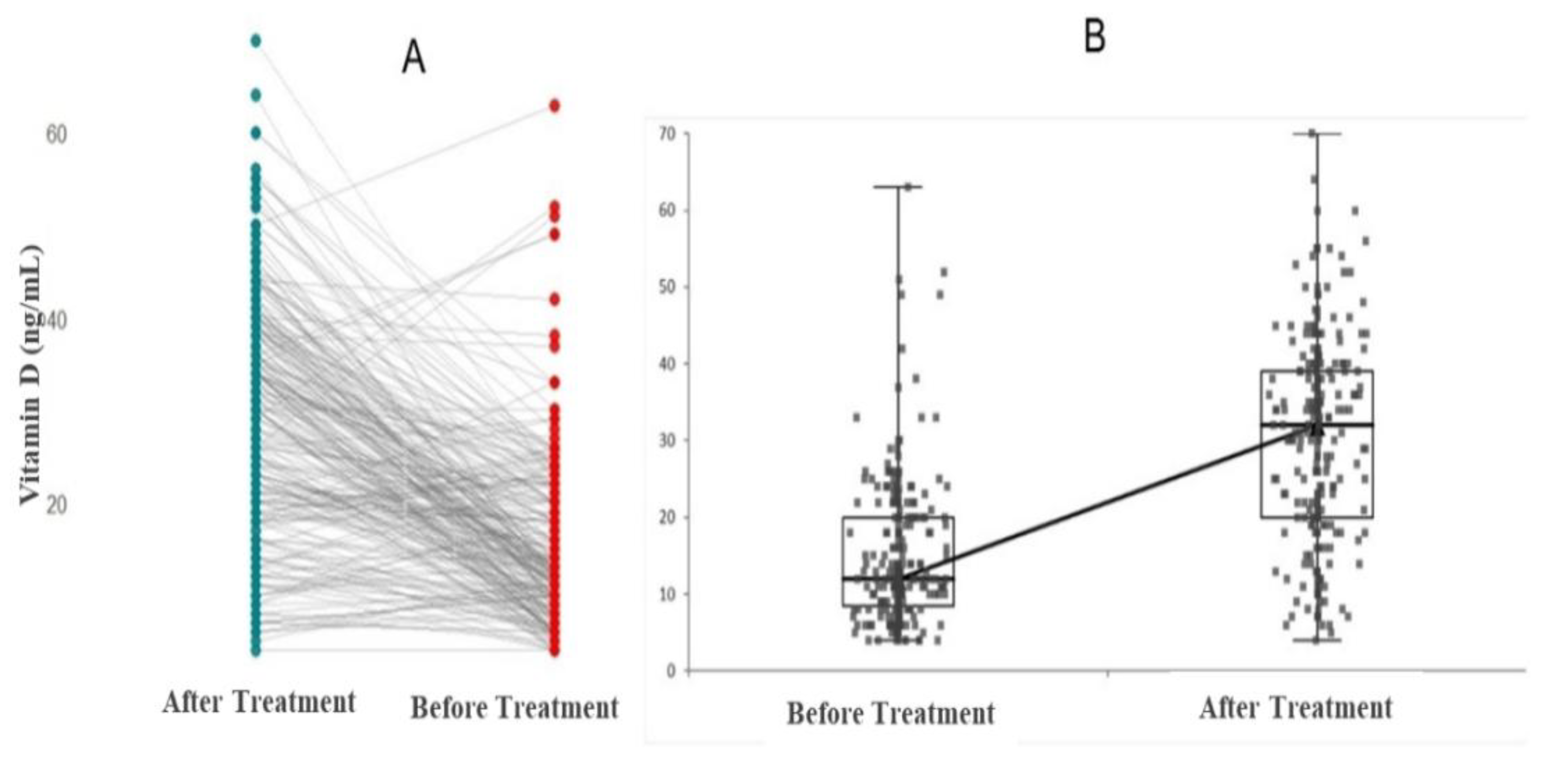

| IBS-D Group (N=53) | |||

| Before Treatment | After Treatment | P value | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 12 (10-20) | 33 (25-36) | 0.001 |

| IBS-C Group (N=108) | |||

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 13 (9-22) | 32 (20-40) | 0.001 |

| IBS-M Group (N=79) | |||

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 11 (8-18) | 28 (18-40) | 0.001 |

| IBS-D Group (N=53) | P value | ||

| Female | Male | ||

| Before treatment Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 15 (10.2-20) | 11 (7.51-16.5) | 0.291 |

| After treatment Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 33 (21.2-33.7) | 34 (26.5-39.5) | 0.223 |

| IBS-C Group (N=108) | |||

| Before treatment Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 12 (8.75-20) | 16 (11-23.5) | 0.150 |

| After treatment Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 32 (19-40) | 32.5 (20-40.5) | 0.372 |

| IBS-M Group (N=79) | |||

| Before treatment Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 10 (7-13.5) | 13.5 (8-22.5) | 0.025 |

| After treatment Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 26 (16-39) | 34 (18.7-40.5) | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).