1. Introduction

Mexico is considered one of the main producers of maize and possesses the greatest diversity of genetic resources, with approximately 59 different native varieties classified based on their morphological characteristics. Among these, pigmented varieties such as violet, red, black, and blue stand out, and are cultivated in various regions of the country. The beneficial properties of pigmented maize are mainly related to its biological activity, particularly its antioxidant content, which provides health benefits and contributes to disease prevention [

1,

2].

Maize is used to make a wide variety of foods, being tortilla the most common one [

3]. Fermented maize-based beverages are also part of the gastronomic heritage of Mexico and have an important cultural and economic role, mainly among ethnic groups. The most important beverages, include Pozol, Chorote, Tepache, Sendechó, Axokot, Tesgüino, Agua agria, and

Atole agrio (sour atole) among others [

4,

5,

6].

The beverage known as atole is prepared from maize meal that is cooked and drunk as a hot thick gruel. Traditionally, it is prepared from cooked or fermented maize dough. This dough can be prepared from cooked or lime-treated (nixtamalized) maize. The diluted fermented dough is boiled to gelatinize the starch, producing a thick and viscous beverage that is consumed hot.

Atole agrio or sour atole is produced in several regions of Mexico, where is also known as xocoatole, jocoatole, xucoatole, shucoatole, atolshuco, atolxuco, etc. This is usually homemade and spontaneously fermented by a diversity of microorganisms, including yeasts, bacteria, and fungi [

7]. The action of the different microorganisms gives the product its sensory attributes and specific functionalities. The quality of the fermented beverage is affected by external factors, such as temperature, rain and humidity, therefore, many of these drinks differ in flavor, aroma, color and texture [

8].

The main group of microorganisms which have been involved in the fermentation of

atole agrio prepared from white maize are lactic acid bacteria (LAB). The most abundant fermentation bacteria included

Lactococcus lactis, Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Levilactobacillus brevis, Loigolactobacillus coryniformis, Pediococcus pentosaceus and

Weissella confusa. They are capable of producing vitamins, organic acids, bacteriocins and enzymes [

9,

10], improving the nutritional, physicochemical and sensory characteristics of the final product [

8]. Within the functional properties provided by lactic acid bacteria, the degradation of anti-nutritional factors (phytic acid) and greater availability of soluble fiber, soluble arabinoxylans, free phenolic acids (antioxidants) and bioactive peptides are the most important [

11]. The objective of this research was to isolate, identify and evaluate the probiotic potential of some LAB from the fermented uncooked

atole agrio beverage (10 - 12 h) prepared from blue maize in the municipality of Tlapacoyan, Veracruz, Mexico. To our knowledge, this is the first study on the blue maize

atole agrio and the probiotic potential of its LAB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Blue maize (Zea mays) var. Tuxpeño was obtained from local stores at Tlapacoyan municipality, Veracruz, Mexico where the atole agrio was made. The maize was selected, choosing whole grains and without contamination of foreign material (insects, wood, straw. etc.).

2.2. Preparation of Atole Agrio

To prepare the beverage, the blue maize was washed and soaked overnight, then ground in a traditional manual maize and grain grinding mill (Corona®, Bogotá, Colombia). The coarse meal was placed in a pewter pot with drinking water and was washed by removing the pericarp, obtaining a dough that was ground again. This process was repeated three times, and finally filtered using a home steel strainer before being incorporated into a clay jar, leaving it near a fireplace to maintain a stable temperature (~37°C). After 10 hours of fermentation, the beverage was placed over direct heat until the boiling point was reached (~96°C) to finish with the addition of sugar and cinnamon to suit the consumer taste. The uncooked fermented samples were taken and cold stored during each stage of the fermentation process, as well as in the final product.

2.3. pH Variation Measurement

The samples were homogenized, and the pH measured using a digital pH meter (Ketoket, MX-601, Mexico) calibrated with buffer solutions of pH 4 and 6.86. The electrode was immersed in the sample and the reading was taken in duplicate [

10].

2.4. Microbiological Analysis and Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Isolation

Microbial counts were determined by the plate count method in the

atole agrio before and after the fermentation and in the final cooked product. The samples were homogenized with 0.1% peptone water and ten-fold diluted as required. Aerobic mesophilic microbes (Plate Count Agar, BD Bioxon) and coliforms (Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar, BD Bioxon) were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, LAB (MRS Agar, BD Difco) at 37°C for 24 h, and yeasts and moulds (Potato Dextrose Agar, BD Bioxon) at 25°C for 120 h. The results were expressed in CFU/g sample. For each sampling stage, 5 to 10 individual colonies were randomly selected from the MRS plates and sub-cultured on MRS agar for further analysis. Presumptive LAB (Gram-positive and catalase negative bacteria) were purified by successive sub-culturing on MRS plates [

9]. Purified isolates were stored at -20°C in MRS broth supplemented with 40% (w/v) glycerol.

2.5. Probiotic Potential and Characterization of LAB Isolates from Atole Agrio

2.5.1. Tolerance to Different pH Values

The evaluation of pH tolerance was performed according to the methodology of Adugna and Andualem [

12] with some modifications. Isolates were grown individually in MRS broth at 37°C for 16 h, to obtain a concentration of approximately 10

7 CFU/ml, and the culture was centrifuged 2 min (10 000 rpm, 4°C). To simulate the gastrointestinal environment, the pellet was washed and centrifuged with 5 ml of saline phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), the recovered cell pellet was re-suspended in MRS broth to have an initial concentration of 10

6 CFU/ml. Aliquots of 10 ml of MRS broth adjusted to different pH values (2, 2.5 and 3) with 1N HCl were inoculated with 1 ml of the culture and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After that, 1 mL was taken from each tube of acid suspension and diluted in 9 ml of peptone water to perform serial dilutions and an aliquot of 100 μL was added to MRS agar and plate cultured. The inoculated plates were placed under anaerobic conditions and incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 h. To calculate the percentage of bacteria that survived exposure to acidic conditions (i.e., the percentage of viable LAB), the ratio of the count of LAB on MRS agar after exposure to the acidic medium (N1) divided by the initial count of bacteria at the start of experimentation (N0) was determined:

2.5.2. Resistance to Bile Salts

Strains that showed a level of acid tolerance were preselected, cultured overnight in MRS broth at 37°C, and each culture centrifuged at 3000 x g for 10 min with an initial concentration of 108 CFU /ml (bacterial concentration was analyzed by plate count and turbidimetry). Then, the pellet was washed twice with phosphate buffer solution (PBS), pH 7.2 ± 0.01 and resuspended in 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 3% (w/v) of bile (BD Difco™ Oxgall / Ox Bile) in MRS broth, respectively and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C.

Serial dilutions were carried out, a 0.1 μl aliquot of each culture was cultured on MRS agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24-48 h. The experiment was performed in triplicate and the survival rate of each isolate was calculated. The ratio of the number of LAB colonies counted on MRS agar after exposure to bile salts (N1) divided by the initial concentration of bacteria at time zero (N0) and multiplied by 100 was used to calculate the percentage of survivors [

12].

2.5.3. Halotolerance of the Isolates

Isolates with the highest survival rate in the presence of bile were selected for further analysis. Halotolerance tests were then carried out. The methodology proposed by González-Quijano et al. [

13] was employed, with minor adjustments. Each strain was cultivated overnight at 37°C to inoculate 5 ml tubes containing modified MRS broth with 4, 10, or 16% NaCl. The initial inoculum was 1 × 10

7 CFU/ml, and growth was measured by optical density (OD

560) for 24 and 48 h.

2.5.4. Hydrophobicity of the Cell Wall

The organic solvent affinity test was performed in accordance with the methodology established by Oviedo et al. [

14], with minor modifications. The strains to be analyzed, were first subcultured overnight in MRS broth at 37°C. Then, the culture was subjected to centrifugation (3000 x g for 10 min). The resulting pellet was then washed twice with PBS (pH 7.2) to resuspend. Subsequently, 3 ml of the bacterial suspension and 0.75 ml of the solvent (hexadecane and chloroform) were added, respectively. The mixture was then vortexed gently for two minutes and allowed to incubate statically for one hour at 37°C. Subsequently, the optical density (OD

560) of the aqueous phase was measured. The percentage of hydrophobicity was determined using the following equation; where Ai represents the initial absorbance and Af the final absorbance of the aqueous phase.

2.5.5. Autoaggregation Assay

For this test, the methodologies of Wójcik et al. [

15] and Oviedo et al. [

14] were followed with some modifications. The selected LAB strains were incubated in MRS broth overnight, and then the cultures were centrifuged at 3000 x g and washed twice with PBS (pH 7.2). The bacterial suspension was adjusted to an OD560 of 0.9 ± 0.05, equivalent to 1x108 CFU/ml, 5 ml of the previously OD-adjusted bacterial suspension was mixed vigorously for 10 seconds and incubated for 4 hours. The percentage of autoaggregation was calculated as shown below; where At is the absorbance after 4 hours of incubation and A0 is the initial absorbance.

2.5.6. Coaggregation Test

The ability of LAB isolated from the fermentative process of

atole agrio to coaggregate with different Gram-positive (

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm: ATCC 19115) and

Staphylococcus aureus (Sa: ATCC 25923)) and Gram-negative (

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (St: ATCC 140228) and

Escherichia coli (Ec: ATCC 45895)) pathogens was evaluated according to Collado et al. [

16] with slight modifications. The pathogen strains were maintained on Nutrient Agar (BD Difco) until used.

The previously selected LAB strains used for the autoaggregation assay and the pathogen strains were incubated overnight in MRS broth at 37°C. Each strain (LAB and pathogenic) was washed twice with PBS (pH 7.2) and resuspended in the same solution to an OD of 0.9 ± 0.05, and finally mixed (2 ml each) to measure the initial OD. Next, vigorous shaking was applied for 10 s, and the mixtures were incubated for 2 and 4 hours measuring the OD at each incubation time. All experiments were performed in triplicate, the percentage of coaggregation was determined using the following formula:

Where Apat and Aprobio represent pathogenic and probiotic strains of the separated bacterial suspensions and Amix represents the absorbance of the mixed pathogenic and probiotic strains at two time points, 2 and 4 h respectively.

2.5.7. Antimicrobial Activity

The antagonistic activity of the selected strains was evaluated by the well diffusion technique [

9,

14], pathogenic strains were used:

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm: ATCC 19115),

Staphylococcus aureus (Sa: ATCC 25923),

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (St: ATCC 140228) and

Escherichia coli (Ec: ATCC 45895). Pathogenic and isolates cultures were subcultured for 24 h at 37 °C. Each pathogen was inoculated in Petri dishes with nutrient agar and Listeria enrichment agar (for

L. monocytogenes culture) by carpet culturing with sterile cotton swap covering the medium uniformly, then wells were made and 0.1 μl of each isolated culture (10

8 CFU/ml) was deposited for each pathogen performing the assay in triplicate. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and the results were measured by the presence of a halo around the wells, which were recorded in mm.

2.5.8. Amylolytic Activity

Due to the nature of the product (starch-containing substrate), the isolates were tested for their ability to metabolize starch so the methodology of Väkeväinen et al., [

9] was followed with slight modifications. Seven isolates from the fermentative process of

sour atole were cultured in MRS broth and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Subsequently, these isolates were inoculated on MRS agar supplemented with 1% soluble starch. After incubation for 48 h at 30°C followed by 24 h at 4°C, and then a 4% v/v iodine solution was sprayed and the formation of a clear halo (mm) was observed.

2.5.9. Identification of Isolates Using the System VITEK® MS

The method and equipment used in this research included the VITEK® MS plus system (V2.2/CLI2.0.0, V3.0/CLI3.0.0, bioMérieux S.A., Marcy l’Étoile, France) provided by the Automated Microbiological Identification Laboratory (AIMA). From the probiotic potential tests, the best isolates were selected and cultured by cross streaking on MRS agar and incubated for 24 h at 37°C, then one colony was picked for each isolate previously selected by the probiotic potential tests and as lactic acid bacteria of the fermentative process of the

atole agrio. The protocol for bacterial identification was followed in which 1 μl of CHCA Matrix was added in each of the prepared wells of the object holder, allowing the well to dry completely. Next, the sample was assigned using Vitek MS prep Station, then the spectra were obtained using Vitek MS Acquisition and finally the results were acquired using MYLA® [

17].

2.5.10. Statistical Analysis

The chemical characterization tests were carried out in triplicate and expressed as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviations. Differences among groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a significance level of ɑ = 0.05 in all samples using the software R student version 1.4.2.1 (R Core Team, Boston, USA 2021).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. pH Variation During Atole Agrio Preparation

During fermentation, variations in pH and temperature were monitored to understand the production process (

Table 1). It can be observed that at hour 6 the pH decreased to 5.86 and at the end of the fermentation (12 h) a pH of 4 was obtained. The temperature was adequate (22-37°C) for the fermentation process to develop. At the end of the 12 h fermentation, the pot was placed over direct heat and the starch contained in the maize grains swelled, due to the gelatination process, when heated (>84°C) [

18], making the drink thicker and with an adequate consistency.

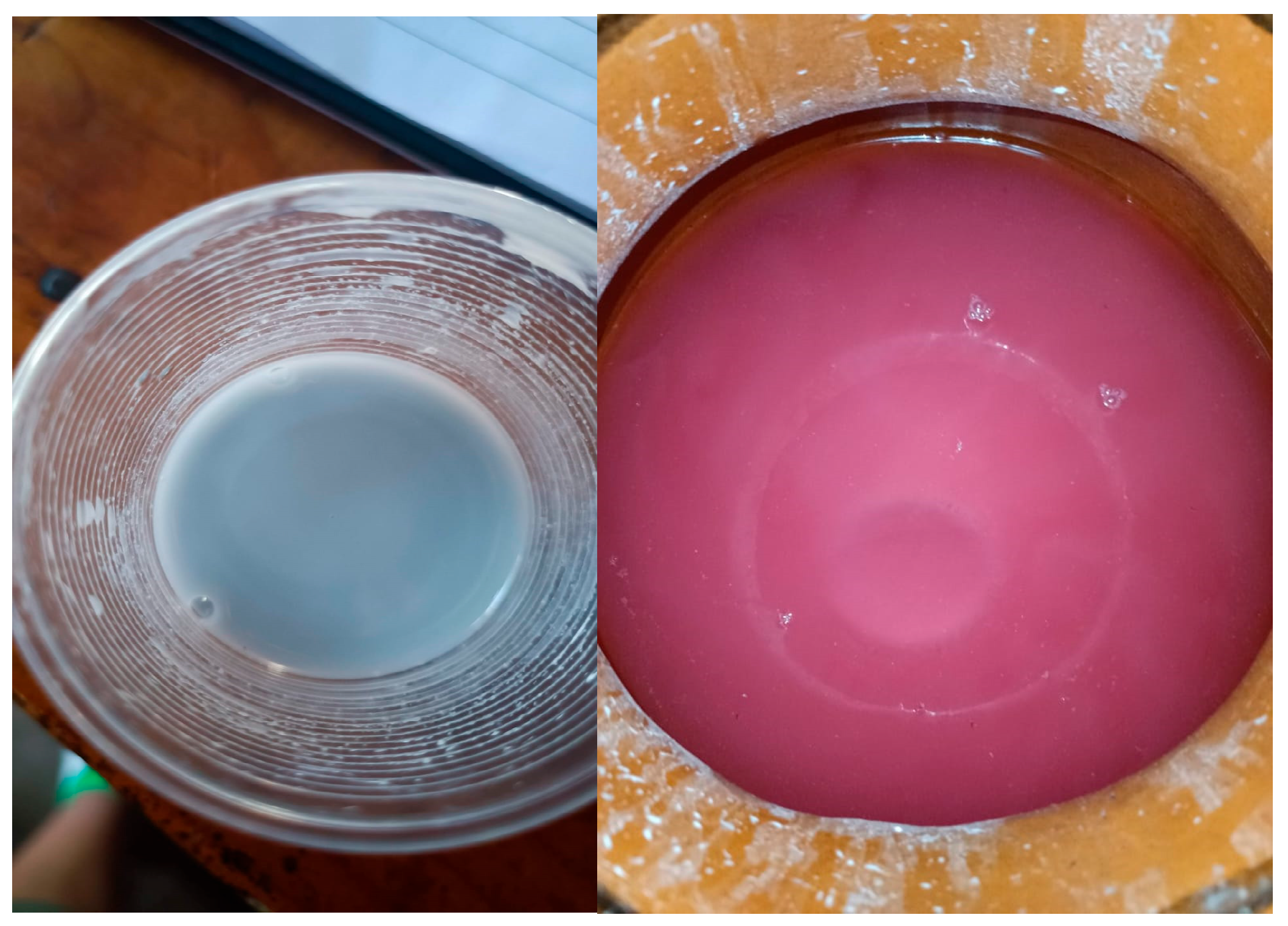

The decrease in pH is due to the microbial consortium present in the beverage which produces a variety of metabolites, mainly organic acids such as acetate, lactate, propionate, etc.. This decrease in pH plays an important role in the development of sensory characteristics and the improvement of nutritional value, through the degradation of complex compounds such as carbohydrates, protein and fiber [

6]. The colour of blue maize atole agrio depends on the pH-dependent behaviour of the anthocyanins present in the cereal. This is due to the ionic nature of the molecular structure of anthocyanins. In acidic condition, some of the anthocyanins look red but have a purple hue in neutral pH while the colour changes to blue under basic pH conditions. The red-colored pigments of anthocyanins are predominantly in the form of flavylium cations and are more stable at a lower pH solution [

19]. In the case of blue maize atole agrio, the initial product, having a pH value of 6.42, has a purple blue colour, whereas the final fermented product has a red hue since the pH reached a value of 4. See

Figure 1. Blue corn anthocyanins have been used as pH indicators in smart packaging indicator films [

20].

3.2. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria

From the final fermented product, 49 LAB isolates were obtained where 28 of them were observed as short bacilli, 9 as long bacilli and 12 as cocci. Väkeväinen et al. [

9] reported the isolation of 88 LAB from white maize atole agrio, similarly Otunba et al. [

21] reported 11 LAB isolates from fermented sorghum products including bacilli and cocci and Cizeikiene et al. [

22] reported the isolation of 10 LAB from spontaneous Lithuanian rye sourdoughs.

3.3. Probiotic Potential Determination of the LAB Isolates

3.1.1. Tolerance to Different pH Values

Of the 49 isolates (100 %) which were subjected to the pH resistance treatment for 2 hours, 44 isolates (89.8 %) survived at pH 3, 39 (79.6%) to pH 2.5 and, finally, only 16 isolates (32.6 %) remained viable at pH 2 with survival rates higher than 80%. These results allowed the selection of the 16 isolates with better tolerance to these acidic conditions (

Table 2), where the coccus morphology has predominated and better resisted pH changes. Opposing results were obtained by Adugna and Andualem [

12], in submitting 80 isolates to low pH conditions of which only six strains of Lactobacillus presented a good tolerance. LAB such as Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Streptococcus and Pediococcus are bacterial genera that are normally acidophilic and manage to tolerate low pH through a variety of mechanisms such as neutralization reactions, biofilm development, proton pumps, shielding of macromolecules, preadaptation and cross-protection, and activity of solutes [

23]. This tolerance is very important for a LAB to be considered as part of starter cultures for the fermentation of various food products such as milk, vegetables, cereals to produce organic acids such as lactic, acetic, etc. [

24]. An indispensable requirement in probiotics is their tolerance to low pH in order to survive the human gastric conditions (pH 1.5-3.5) for periods of 30 min to 2 hours [

25].

3.1.2. Bile Salt Tolerance

The selected LAB isolates (16 strains) that showed the higher resistance to pH values of 2, they were subjected to 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, and 3.0% ox bile (DifcoTM Oxgall) during a 24 h incubation period at 37°C. Most isolates exhibited a similar and excelent tolerance to bile at concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 1.5%. with final counts of 6 Log CFU/ml. Of the 16 isolates tested, only seven showed a good tolerance to a 3% concentration of bile salts. Isolates AG13, AG29, AG34 and AG35 maintained a concentration of approximately 6 to 7 Log CFU/ml, while isolates AG40, AG41 and AG43 showed a reduction of more than 50 % with respect to the control with 0% bile salts (8 Log CFU/ml). (

Figure 2).

Bile salts are biological detergents that emulsify and solubilize lipids, playing a crucial role in fat digestion, providing simultaneously with an antibacterial activity, mainly by dissolving bacterial membranes [

12]. The conjugated bile salts cause bacterial toxicity by a mechanism similar to that of organic acids, i.e., by acidification of the cytoplasm [

26]. Hydrolysis of the conjugated bile salt and cotransport of the proton with the deconjugated product to the outside of the cell could be one of the mechanisms of resistance against this natural barrier, henceforth resistance to bile salts due to salt hydrolase activity has been described as an important mechanism [

27].

Gil-Rodriguez & Beresford [

27] evaluated the growth of various species of LAB, finding that all strains of certain species showed ability to grow under a low concentration of bile (0.3%) to varying degrees (i.e.,

Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. brevis, L. casei, L. curvatus, L. paracasei, L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus, L. salivarius,

Pediococcus acidilactici and

P. pentosaceus), whereas all strains of other species were inhibited by salt bile (i.e.,

L. helveticus,

Leuconostoc lactis and

L. delbrueckii ssp

bulgaricus). This indicates that the isolates of the fermentative process of

atole agrio could have a potential cholesterol-lowering probiotic effect due to the presence of the enzyme bile-salt hydrolase [

27].

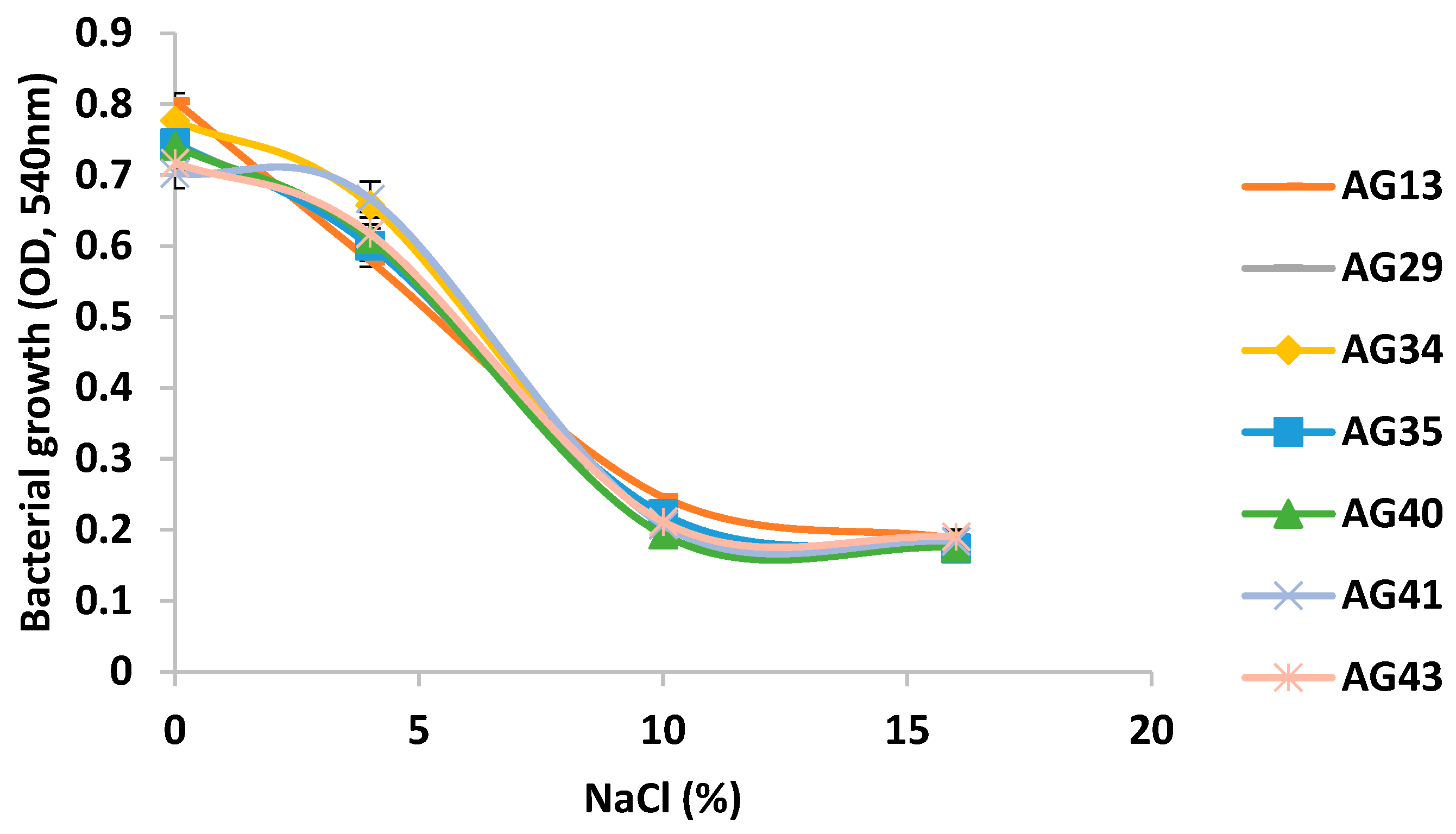

3.1.3. Halotolerance of LAB Isolated from the Fermentative Process of Atole Agrio

The seven LAB isolates previously selected for their resistance to pH 2 and 3% bile salt concentration were evaluated for halotolerance. All isolates had a notably reduced growth in the presence of increasing concentrations of sodium chloride (

Figure 3). However, all isolates exhibited still a significant growth around 7.5% NaCl, confirming their halotolerant character. The maximum growth of the LAB strains at different concentrations of NaCl and their behavior can be described as a decreasing logistic curve as previously reported by González-Quijano et al. [

13]. All the isolates had similar growths and their range of tolerance was from 4 to 10% sodium chloride showing still a weak grow at 16% salt.

Halotolerant microorganisms can be defined as those capable of growing in the absence as well as in the presence of relatively high NaCl concentrations. If growth spreads above 2.5 M (14.61%), they are known as extremely halotolerant [

28]. The above results indicate that the seven LAB isolates could then be considered as moderate halotolerant microorganisms.

3.1.4. Hydrophobicity of the Cell Wall

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the results for the microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons (MATH) test for measuring the hydrophobicity of the cell wall using hexadecane and toluene. This method is related to the role of hydrophobic interactions in microbial adhesion. The seven selected strains were evaluated, strains AG13, AG40 and AG43 reached values in hexadecane of 27.6 ± 0.5 %, 18.3 ± 0.3% and 20.7 ± 0.1%, after 2 hours of incubation. The ability of bacteria to bind to the intestinal epithelium includes several mechanisms, including adhesins present on the surfaces of bacterial cells, which have carbohydrate bonds located in the glycocalyx of enteric cells that function as anchor spots for the bacteria, thus colonizing the intestine and preventing a further adhesion of pathogens [

29].

Another study performed with xylene and hexadecane evidenced hydrophobicity percentages above 78% (

Lactobacillus sp. Leuconostoc sp, Streptpococcus sp) and slightly low percentages for

Lactococcus sp and

Pediococcus sp [

30]. At present, it appears that hydrophobic surface properties, as measured by MATH, may play a role in predicting adhesion to host cells, aggregation, and flocculation.

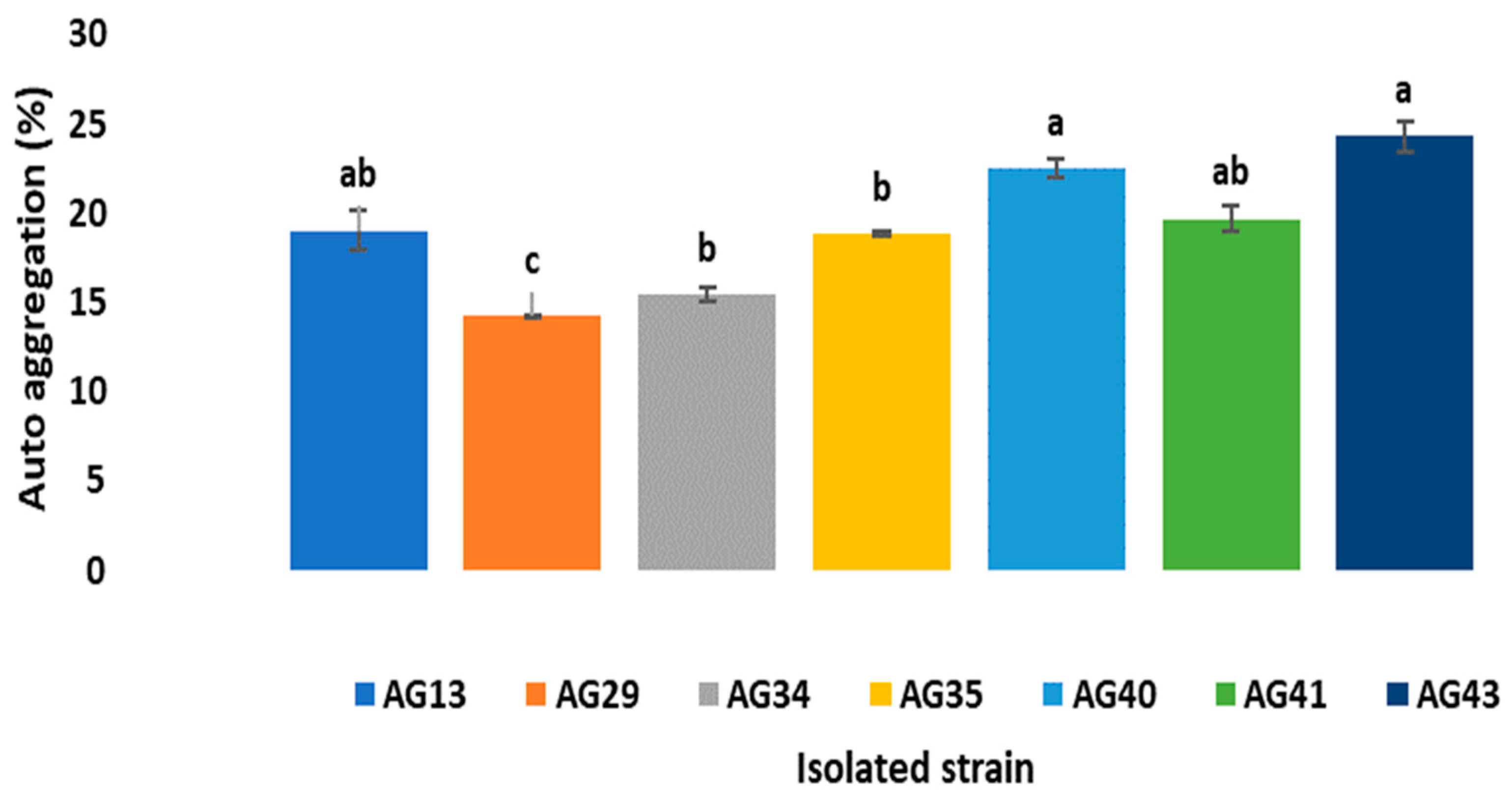

3.1.5. Autoaggregation

The percentages of autoaggregation (

Figure 6) showed values of 24.31% ± 0.8 for AG43 strain, with the AG29 isolate showing the lowest values of self-aggregation (14.22% ± 0.01). According to García et al., [

31], this phenomenon is defined when cells of the same species are aggregated, related to the components of the bacterial wall, so that probiotics or LAB can bind to intestinal cells and stimulate the immune system and act as a barrier against pathogenic microorganisms [

32].

The results shown in

Figure 6 are similar to those reported by Rahman et al. [

33] for bifidobacterial, where the autoaggregation values were divided into high (>70%), medium (20–70%) and low (<20%), so the isolates evaluated in this study are in the range of low and medium autoaggregation values, which are related to the low hydrophobicity presented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. This could be due to the type of LAB isolate and also to the possible correlation with the hydrophobicity values [

14].

3.1.6. Coaggregation

The data showed that the levels of coaggregation between the LAB isolated strains and the tested pathogens (S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and S. enterica) varied, ranging from 20 (AG35) to 28.6% (AG34) after 4 h of incubation. In general, all seven LAB isolates coaggregated similarly with the four pathogenic strains tested.

The ability of lactic acid bacteria to coaggregate with pathogens may explain one of the mechanisms by which they are considered a host defense against infection [

14]. Therefore, this assay is considered an important to evaluate probiotic potential, since it is involved in the colonization of microorganisms beneficial to the host [

34]. Laurencio et al., [

29] evaluated the coaggregation of

Lactobacillus spp. with the cell walls of

E. coli, S. aureus and

Klebsiella spp., finding that all the strains evaluated showed a coaggregation greater than 50%, except LvB-52 against

E. coli (18%).

According to the results, all the isolates subjected to the coaggregation test have the capacity to bind to pathogenic bacteria (Gram positive and Gram negative) although the percentages may depend on the type of strain in addition to the incubation time, which agrees with the findings provided by Collado et al., [

16], who explain that the longer the incubation time, the greater the aggregation. Our results suggest, as in other studies, that the autoaggregation ability of LAB strains may be linked to their capacity to coaggregate with pathogens, as both processes are thought to contribute to the exclusion and inhibition of pathogenic bacteria in the intestinal tract [

14,

35,

36].

3.1.7. Antibacterial and Amylolytic Activities

The seven LAB isolates (

Table 3) showed notable antibacterial properties against

Staphylococcus aureus (Sa),

Salmonella enterica (St),

Escherichia coli (Ec), and

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm). Strain AG35 showed the highest antibacterial activity against Sa, AG40 against St, AG41 against Ec, and AG34 against Lm. Sa and Ec showed high susceptibility against the selected strains, while St and Lm showed medium susceptibility. The bactericidal activities presented in the study were higher than those of the strains isolated from white maize

atole agrio in the state of Tabasco by Väkeväinen et al. [

9], which exhibited inhibition halos between 11 and 17 mm maximum. Considering the short fermentation duration of blue maize

atole agrio (9 h) and the high bacterial counts with probiotic characteristics, the selected strains have remarkable antibacterial activities against important pathogens in food safety. The antibacterial activities of LAB isolated from plant sources result from the production of primary metabolites, mainly organic acids, generally lactic acid [

37]. Lactic acid has bactericidal activity against pathogens by reducing the proliferation of bacteria susceptible to pH changes through acid stress [

38]. Furthermore, some bacteria with probiotic capacity produce secondary metabolites such as bacteriocins or BLIS (bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances), which inhibit the growth and reproduction of numerous bacteria [

39]. The aforementioned metabolites are of great interest in the food sector since they are applied in the preservation of food products and human health, highlighting different LAB species in dairy products [

40].

Similarly, the analyzed isolates in this study had, as expected, amylolytic capacity (

Table 3). Some lactic acid bacteria produce extracellular amylases capable of hydrolyzing starch, highlighting some strains of

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and

Levilactobacillus brevis (> 9.23 ± 0.39 U/mL). The amylase produced by these bacteria is capable of degrading starch into dextrin and subsequently into glucose [

41,

42].

3.1.8. Identification of Isolates Using the Vitek MS Plus System

The strains with the best probiotic characteristics were preselected. The seven isolates mentioned above were identified and all of them turned out to be Pediococcus pentosaceus.

Mass spectrometry has become an important tool for the microbiologist and the biotechnologist for bacterial identification, since matrix assisted laser desorption ionization- time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) has been revealed to provide reliable protein profiling data to identify many bacteria [

43] including LAB [

17].

Pérez-Cataluña et al. [

10] mentioned that strains of

P. pentosaceus found in the fermentation process of atole agrio have proven to be effective in the food industry, mainly as starter cultures in the fermentation of amaranth sourdoughs in addition to being an important strain in the reduction of mycotoxins during the fermentation of maize to produce Ogi (cereal porridge from Nigeria). The presence of this LAB was reported in the fermentation of

atole agrio made from “de dobla” maize in Tabasco, Mexico [

44], along with other LAB such as

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Lactococcus lactis and

Leuconostoc pseudomensenteroides. Hernandez-Vega [

45] used these bacteria, in addition to

P. pentosaceus, as starter cultures in the elaboration of white maize

atole agrio. The

P. pentosaceus strain increased lactic acid concentration in all tests, while

Lc. lactis showed lower lactic acid levels compared to the others. They also showed that LAB counts were higher at the end of the fermentations, significantly reducing the presence of enterobacteria, coinciding with the results obtained in this work where the reduction of these bacteria was achieved at the end of the fermentation process. This may confirm the presence of secondary metabolites such as bacteriocins (pediocins), which are small peptides (36 to 48 amino acid residues), capable of efficiently inhibiting bacteria such as

Listeria monocytogenes [

46,

47].

The beneficial features of the genus

Pediococcus, including their role as probiotics, has been previously reviewed [

48] and the presence of

P. pentosaceus in other fermentations involving cereals such as wheat and sorghum has been reported before [

21,

22].

4. Conclusions

This study reports the isolation, analysis of probiotic potential, and identificaction of LAB from the fermentation of blue maize atole agrio from Tlapacoyan, Veracruz, Mexico. The bacteria Pediococcus pentosaceus, predominant in the fermentation process of atole agrio, exhibit a remarkable resistance to fluctuations in temperature, pH, salt concentration, and bile salts. Additionally, these bacteria possess adhesive characteristics such as coaggregation, autoaggregation, and cell wall hydrophobicity, as well as antibacterial and amylolytic activities. Consequently, a functional beverage loaded with potentially probiotic LAB and antioxidant phenolic compounds is produced during the blue maize atole agrio fermentation process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.G. and H.H.S.; methodology, M.T.G., R.M.R.A., M.G.A.A., G.F.G.L. and H.H.S.; validation, M.T.G, and H.H.S; formal analysis, H.H.S.; investigation, M.T.G. and H.H.S.; resources, H.H.S.; data curation, M.T.G. and H.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.G.; writing—review and editing, H.H.S.; supervision, H.H.S.; project administration, H.H.S.; funding acquisition, H.H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Author M.T.G. thanks the CONAHCyT in Mexico for the scholarship to pursue her Ph. D. studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Mora-Rochín, S.; Gaxiola-Cuevas, N.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A.; Milán-Carrillo, J.; Milán-Noris, E.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Serna-Saldívar, S.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E. Effect of traditional nixtamalization on anthocyanin content and profile in Mexican blue maize (Zea mays L.) landraces. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 563-569. [CrossRef]

- Camelo-Méndez, G.A.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Functional study of raw and cooked blue maize flour: starch digestibility, total phenolic content and antioxidant activity. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 76, 179-185. [CrossRef]

- Dorantes-Campuzano, M.; Cabrera-Ramírez, A.; Rodríguez-García, M.; Palacios-Rojas, N.; Preciado-Ortiz, R.; Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Gaytán, M. 2022. Effect of maize processing on amylose-lipid complex in pozole, a traditional Mexican dish. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100078. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Morales, M.; Wacher-Rodarte, M.C.; Hernández-Sánchez, H. Preliminary studies on chorote – a traditional Mexican fermented product. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 293-296. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Dirzo, M.G.; López-Ferrer, C.E.; Flores-Valadez, M.; Jofre-Garfias, A.L.; Aguirre-Rodríguez, J.A.; Morales-Cruz, E.J.; Reyes-Chilpa, R. Estudio preliminar del Axokot, bebida tradicional fermentada, bajo una perspectiva transdisciplinaria. Inv. Univ. Multidiscip. 2010, 9(9), 113-124.

- Rubio-Castillo, A.E.; Santiago-López, L.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.; González-Córdova, A.F. Traditional non-distilled fermented beverages from Mexico based on maize: An approach to Tejuino beverage. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23, 100283. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Armendáriz, B.; Cardoso-Ugarte, G.A. (2020). Traditional fermented beverages in Mexico: Biotechnological, nutritional, and functional approaches. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109307. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Tuaño, A.; Juanico, C. Microbial quality, safety, sensory acceptability, and proximate composition of a fermented nixtamalized maize (Zea mays L.) beverage. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 107, 103521. [CrossRef]

- Väkeväinen, K., Valderrama, A., Espinosa, J., Ceturión, D., Rizo, J., Reyes-Duarte, D., Díaz-Ruiz, G., Wright, Atte von, Elizaquível, P., Esquivel, K., Simontaival, Anna-Inkeri, Aznar, R., Wacher, C., Plumed-Ferrer, C. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria recovered from atole agrio, a traditional Mexican fermented beverage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 88, 109-118. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Elizaquível, P.; Carrasco, P.; Espinosa, J.; Reyes, D.; Wacher, C.; Aznar, R. Diversity and dynamics of lactic acid bacteria in Atole agrio, a traditional maize-based fermented beverage from South-Eastern Mexico, analysed by high throughput sequencing and culturing. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 385-399 . [CrossRef]

- Manini, F.; Casiraghi, M. C.; Poutanen, K.; Brasca, M.; Erba, D.; Plumed-Ferrer, C. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from wheat bran sourdough. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 275–283. [CrossRef]

- Adugna, M.; Andualem, B. Isolation, characterization and safety assessment of probiotic lactic acid bacteria from metata ayib (Traditional spiced cottage cheese). Food and Humanity 2023, 1, 85-91. [CrossRef]

- González-Quijano, G. K.; Dorantes-Alvarez, L.; Hernández-Sánchez, H.; Jaramillo-Flores, M. E.; Perea-Flores, M.J.; Vera-Ponce de León, A.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Halotolerance and Survival Kinetics of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Jalapeño Pepper (Capsicum annuumL.) Fermentation. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79(8), M1545–M1553. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Leon, J.F.; Cornejo-Mazon, M.; Ortiz-Hernandez, R.; Torres-Ramírez, N.; Hernández Sánchez, H.; Castro-Rodríguez, D.C. Exploration adhesion properties of Liquorilactobacillus and Lentilactobacillus isolated from two different sources of tepache kefir grains. PLoS ONE 2024, 19(2), e0297900. [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, R.; Małaczewska, J.; Tobolski, D.; Miciński, J.; Kaczorek-Łukowska, E.; Zwierzchowski, G. The Effect of Orally Administered Multi-Strain Probiotic Formulation (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) on the Phagocytic Activity and Oxidative Metabolism of Peripheral Blood Granulocytes and Monocytes in Lambs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5068. [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Meriluoto, J.; Salminen S. Adhesion and aggregation properties of probiotic and pathogen strains. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 226, 1065–1073. [CrossRef]

- Španová, A.; Dráb, V.; Turková, K.; Špano, M.; Burdychová, R.; Šedo, O.; Šrůtková, D.; Rada, V.; Rittich, B. Selection of potential probiotic Lactobacillus strains of human origin for use in dairy industry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 861-869. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L. M.; Halal, S. L. M. E.; Dias, A. R. G.; Zavareze, E. R. Physical modification of starch by heat-moisture treatment and annealing and their applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 274, 118665. [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H. E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. 2017. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and potential health benefits. Review. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61 (1361779), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, B.; Yu, H.; Yuan, M.; Chen, H.; Qin, Y. 2022. Application of pH-indicating film containing blue corn anthocyanins on corn-starch/polyvinyl alcohol as substrate for preservation of tilapia. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 4416-4424. [CrossRef]

- Otunba, A.A.; Osuntoki, A.A.; Olukoya, D.K.; Babaola, B.A. 2021. Genomic, biochemical and microbial evaluation of probiotic potentials of bacterial isolates from fermented sorghum products. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08536. [CrossRef]

- Cizeikene, D.; Juodeikiene, G.; Paskevicius, A.; Bartkiene, E. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria against pathogenic and spoilage microorganism isolated from food and their control in wheat bread. Food Control 2013, 31, 539-545. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, Y.; Qu, X. Mechanisms and improvement of acid resistance in lactic acid bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200 , 195-201. [CrossRef]

- Icer, M.A.; Özbay, S.; Ağagündüz, D.; Kelle, B.; Bartkiene, E.; Rocha, J.M.F.; Ozogul, F. The Impacts of Acidophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria on Food and Human Health: A Review of the Current Knowledge. Foods 2023, 12(15):2965. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Singh Saharan, B. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13 ( 2 ), 933-948. [CrossRef]

- Begley, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G.M. (2006). Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 2006, 72(3), 1729–1738. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Rodríguez, A.M.; Beresford, T. Bile salt hydrolase and lipase inhibitory activity in reconstituted skim milk fermented with lactic acid bacteria. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 77, 104342. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G.; Merlino, A. Molecular bases of protein halotolerance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Spec. Sect. Prot. Proteom. 2014, 1844(4), 850-858. [CrossRef]

- Laurencio-Silva, M.; Arteaga, F.; Macías, I. Potencial probiótico in vitro de cepas de Lactobacillus spp. procedentes de la vagina de vacas lecheras Pastos y Forrajes 2017, 40(3), 206-215.

- Sánchez, L.; Tromps, J. Caracterización in vitro de bacterias ácido lácticas con potencial probiótico. Rev. Salud Anim. 2014, 35(2), 124-129. ISSN 0253-570X.

- García, Y.; Boucourt, R.; Albelo, N. & Núñez, O. Fermentación de inulina por bacterias ácido lácticas con características probióticas. Rev. Cubana Cienc. Agríc. 2007, 41 (3), 263-266.

- Bouridane, H.; Sifour, M.; Idoui, T.; Annick, L., Thonard, P. Technological and probiotic traits of the Lactobacilli isolated from vaginal tract of the healthy women for probiotic use. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 14(3), 192-201. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Kim, W.S.; Kumura, H.; Shimazaki, K.I. Autoaggregation and surface hydrophobicity of bifidobacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 1593–1598. [CrossRef]

- Cesena, C.; Morelli, L.; Alander, M.; Siljander, T.; Tuomola, E.; Salminen, S. Lactobacillus crispatus and its nonaggregating mutant in human colonization trials. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 4(5), 1001–1010. [CrossRef]

- García-Cayuela, T.; Korany, A.M.; Bustos, I.; Gómez de Cadiñanos, L.P.; Requena, T.; Peláez, C.; Martínez-Cuesta, M.C. 2014. Adhesion abilities of dairy Lactobacillus plantarum strains showing an aggregation phenotype. Food Res. Int. 2014, 57, 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Suwannasom, N.; Siriphap, A.; Japa, O.; Thephinlap, C.; Thepmalee, C.; Khoothiam, K. Lactic Acid Bacteria from Northern Thai (Lanna) Fermented Foods: A Promising Source of Probiotics with Applications in Synbiotic Formulation. Foods 2025, 14, 244. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Mandal, S. Probiotic potentiality, safety profiling and broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from sour curd (Malda, India). The Microbe, 2025, 7,100297. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Peng, F.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Xie, M.; Xiong, T. Isolation and characteristics of lactic acid bacteria with antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101446. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cui, Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Fan, X.; Ding, Y. Response mechanisms of lactic acid bacteria under environmental stress and their application in the food industry. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105938. [CrossRef]

- Akpoghelie, P.O.; Edo, G.; Ali, A.; Yousif, E.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Oghenewogaga, J.; Fegor, E.; Igbuku, U.A.; Athan-Essaghah, A.E.; Makia, R.; Ahmed, D.; Umar, H.; Alamiery, A. Lactic acid bacteria: Nature, characterization, mode of action, products and applications. Process Biochem. 2025, 152, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Othuke, P.; Iruoghene, G.; Ali, A.; Emad, Y.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Oghenewogaga, J.; Fegor, E.; Augustina, U.; Efeoghene, A.; Makia, R.; Ahmed, D.; Umar, H.; Alamiery, A. Lactic acid bacteria: Nature, characterization, mode of action, products and applications. Process Biochem. 2025, 152, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. ; Zhou, T. ; Tang, H. ; Li, X. ; Chen, Y. ; Zhang, L. ; Zhang, J. Probiotic potential and amylolytic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Chinese fermented cereal foods. Food Control 2020, 111, 107057. [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.R.; Voorhees, K.J. Bacterial identification by mass spectrometry. In Detection of Chemical, Radiological and Nuclear Agents for the Prevention of Terrorism; Banoub, J., Ed.; NATO Science for Peace and Security Series A: Chemistry and Biology; Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2014. pp. 115-131.

- Valderrama Membrillo, A. Diversidad de bacterias lácticas del atole agrio de Villahermosa Tabasco. B. Sc. Thesis. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. 2012. Available online: https://repositorio.unam.mx/contenidos/219739 (accesed on May 23, 2025).

- Hernández Vega., J.V. Producción de atole agrio usando Lactococcus lactis (A1MS3) y Pediococcus pentosaceus (Sol10) como inóculo. B. Sc. Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Mexico. 2017. Available online: https://ru.dgb.unam.mx/bitstream/20.500.14330/TES01000758654/3/0758654.pdf (accesed on May 23, 2025).

- Porto, M.C.W.; Kuniyoshi, T.M.; Azevedo, P.O.S.; Vitolo, M.; Oliveira, R.P.S. Pediococcus spp.: An important genus of lactic acid bacteria and pediocin producers. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35(3), 361–374. [CrossRef]

- Adesulu-Dahunsi, A.T. ; Sanni, A.I. ; Jeyaram, K. Diversity and technological characterization of Pediococcus pentosaceus strains isolated from Nigerian traditional fermented foods. LWT Food Sci. Technol., 2021, 140, 110697. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov Todorov, S.; Dioso, C.M.; Liong, M.T.; Nero, L.A.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Ivanova, I.V. Beneficial features of pediococcus: from starter cultures and inhibitory activities to probiotic benefits. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).