Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Kinetics of the Fermentation Process

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization (Centesimal Composition)

2.3. Antioxidant Capacity

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

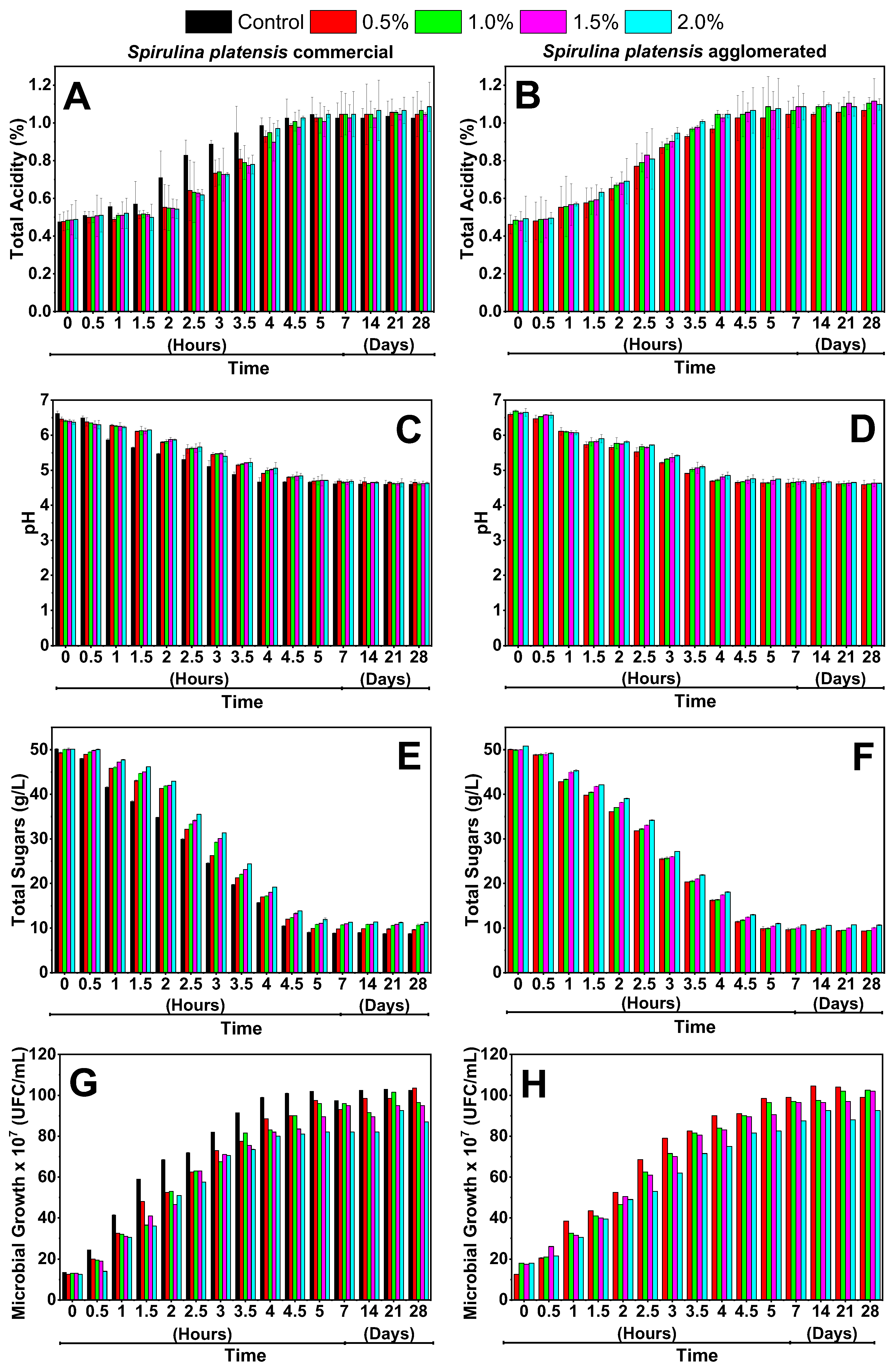

3.1. Kinetics of the Fermentation Process

3.2. Centesimal Composition of the Yogurts

3.3. Antioxidant Content in the Incorporated Yogurts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garavand, F.; Daly, D.F.M.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G. Biofunctional, structural and tribological attributes of GABA-enriched probiotic yogurts containing Lacticaseibacillus paracasei alone or in combination with prebiotics. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 129, 105348. [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, J.R.; Zhang, S.; Akoh, C.C. Combination of antioxidants and processing techniques to improve the oxidative stability of a Schizochytrium algae oil ingredient with application in yogurt. Food Chem. 2023, 417, 135835. [CrossRef]

- Beheshtipour, H.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Haratiano, P.; Khosravi-Darani, K. Effects of the addition of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis on the viability of probiotic bacteria in yogurt and their biochemical properties. Eur. Food Res. Technol 2012, 235, 719–728.

- Bullock, Y.; Gruen, I. Effect of strained yogurt on the physicochemical, textural and sensory properties of low-fat frozen desserts. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100161, 2023.

- Devnani, B.; Ong, L., Kentish, S.; Scales, P.J.E.; Gras, S.L. Physicochemical and rheological properties of commercial almond-based yogurts as alternatives to dairy and soy yogurts. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100185. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yu, L.; Shi, Z.; Li, C.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Z.; Pan, D. Characterization of a novel flavored yogurt enriched in γ-aminobutyric acid fermented by Levilactobacillus brevis CGMCC1.5954. J. Dairy. Sci. 2022, 106, 852–867. [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, E.; Matar, A.; Karam-Allah, A. Functional Properties of Yogurt Fortified with Spirulina platensis and Concentrated Milk Protein. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2022, 13, 1–7.

- Aktar, T. Physicochemical and sensorial characterization of different yogurt production methods. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 125, 105245.

- Jaeger, S.R.; Cardello, A.V.; Jin, D.; Ryan, G.S.; Giacalone, D. Consumer perception of plant-based yogurt: sensory drivers of taste and emotional, holistic and conceptual associations. Int. Food Res. J. 2023, 167, 112666.

- Aleman, R.S.; Cedillos, R.; Page, R.; Olson, D.; Aryana, K. Physicochemical, microbiological and sensory characteristics of yogurt affected by various ingredients. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 3868–3883.

- Hernández, H.M.; Nunes, M.T.; Prista, C.; Raymundo, A. Innovative and healthier dairy products through the addition of microalgae: a review. Food 2021, 11, 755–755. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.B.; Parvin, M.; Huntington, T.C.; Hasan, M.R. A review on culture, production and use of Spirulina platensis as food humans and feeds for domestic animals and fish. FAO 2008, 1034, 1-33.

- Kraus, A. Factors influencing the decisions to buy and consume functional food. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1622-1636. [CrossRef]

- Pan-Utai, W.; Atkonghan, J.; Onsamark, T.; Imthalay, W. Effect of Arthrospira Microalga Fortification on the Physicochemical Properties of Yogurt. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 8(2), 531-540. [CrossRef]

- Shimamatsu, H. Mass production of Spirulina platensis an edible microalga. Hydrobiology 2004, 512 (1), 39-44.

- López, E.P. Superalimento para un mundo en crisis: Spirulina platensis a bajo costo. Idesia 2013, 31(1), 135-139. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, E.T.C.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Fluid catalytic cracking: recent developments on the grand old lady of zeolite catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7342-7370. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, J.A.; Ruprecht, N.A.; Hinrichs, J.; Kohlus, R. Nozzle zone agglomeration in spray dryers: Effect of powder addition on particle coalescence. Powder Technol. 2020, 374, 223-232. [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.C.V.; Silva, C.E.D.F.; Carneiro, W.D.S.; Andreola, K.; Gama, B.M.V.; Silva, A.E.D. Incorporation of Cyanobacteria and Microalgae in Yogurt: Formulation Challenges and Nutritional, Rheological, Sensory, and Functional Implications. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4(4), 1493-1514. [CrossRef]

- Avila-Leon, I.; Matsudo, M. C.; Sato, S.; De Carvalho, J.C.M. Arthrospira platensis biomass with high protein content cultivated in continuous process using urea as nitrogen source. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 6(112), 1086-1094. [CrossRef]

- ANVISA - Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Instrução Normativa - in n° 28, de 26 de julho de 2018. Diário Oficial da União. Publicado em: 27/07/2018 | edição: 144 | seção: 1 | página: 141. 2018.

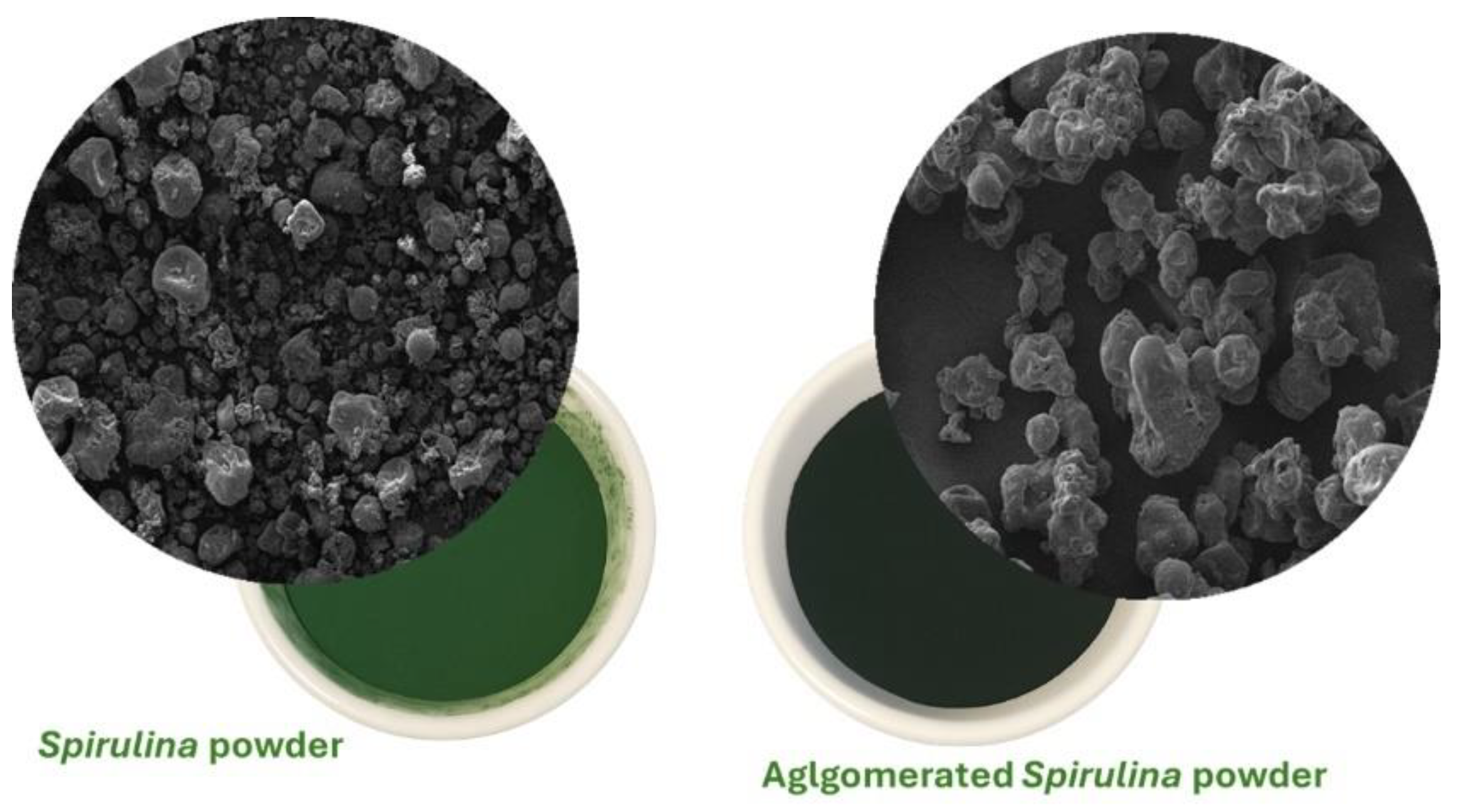

- Carneiro, W.S.; Andreola, K.; Silva, C.E.F.; Gama, B.M.V.; Albuquerque, R.C.V.; Freitas, J.M.D.; Freitas, J.D. Agglomeration Process of Spirulina platensis Powder in Fluidized Bed improves its Flowability and Wetting Capacity. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4(12), 3120-3134.

- Oliveira, E.A.M.; Soldi, C.L.; Caveião, C.; Sales, W.B. Contagem de bactérias láticas viáveis em leites fermentados. Revista Univap 2018, 24(46), 94-104.

- Sousa, T.L.T.L.; Silva, A.M.S.; Silva, M.K.G.; Lima, G.S.; Veloso, R.R.; Shinohara, N.K.S. Counting of lactic bacteria in yogurts and dairy drinks in the metropolitan region of Recife-PE. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11 (15), e157111537002, 2022.

- Instituto Adolfo Lutz. In Métodos físico-químicos para análise de alimentos, edition 4ª, Instituto Adolfo Lutz Eds. Publisher: São Paulo, São Paulo, 2005.

- Trevelyan, W.E.; Forrest, R.S.; Harrison, J.S. Determination of yeast carbohydrates with the anthrone reagent. Nature 1952, 170(4328), 626-627. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. In Official Method of Analysis, edition 16ª, Association of Official Analytical. Publisher: Washington DC, 2002.

- Waterhouse, A.L. PoMANYlyphenolics: determination of total phenolics. In WROLSTAD, R. E. Currente protocols in food analytical chemistry; J. Wiley Eds.; Publisher: New York, EUA, Volume 1, pp. 11-18, 2002.

- Nagata, M., Yamashita, I. Simple method for simultaneous etermination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. J. Japan. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 1992, 39(10), 925-928. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.T.; Burkert, J.F.M.; Costa, J.A.V.; Burkert, C.A.V.; Kalil, S. J. Optimization of phycocyanin extraction from Spirulina. platensis using factorial design. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98(8), 1629-16934. [CrossRef]

- Deindoerfer, F.H.; West, J.M. Rheological examination of some fermentation broths. J. Biochem. Microb. Technol. Eng. 1960, 2(2), 165-175. [CrossRef]

- Gaden, E.L.Jr. Fermentation process kinetics. J. Biochem. Microb. Technol. Eng. 1959, 1(4), 413-429.

- Schmidell, W.; de Almeida Lima, U.; Borzani, W.; Aquarone, E. Biotecnologia industrial. In Engenharia bioquímica; Blucher Eds.; Publisher: São Paulo, Brazil, Volume 2, 2001.

- Brasil. Regulamento técnico de identidade e qualidade de leites fermentados. Instrução Normativa Nº 46 de 23 de outubro de 2007. https://www.studocu.com/pt-br/document/centro-universitario-uniftc/clinica-cirurgica/instrucao-normativa-n-46-de-23-de-outubro-de-2007-leites-fermentados/38234614 (accessed on 7 de Jun. 2023).

- OMC. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Codex Alimentarius. Standard for Fermented Milk (CXS 243-2003).

- Matos, J.; Afonso, C.; Cardoso, C.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Bandarra, N. M. Yogurt enriched with Isochrysis galbana: An innovative functional food. Food 2021, 10(7), 1458. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.K.F.; Moreira, J.B.; Costa, J.A.V.; De Souza, C.K.; Bertoli, S.L.; Carvalho, L.F.D. Evaluation of Adding Spirulina to Freeze-Dried Yogurts Before Fermentation and After Freeze-Drying. Ind. Biotechnol. 2019, 15(2), 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Ebid, W.M.; Ali, G.S.; Elewa, N. A. Impact of Spirulina platensis on the physicochemical, antioxidant, microbiological and sensory properties of functional labneh. Discov. Food 2022, 2(1), 29. [CrossRef]

- Bchir, B.; Felfoul, I.; Bouaziz, M.A.; Garred, T.; Yaich, H.; Numi, E. Investigation of the physicochemical, nutritional, textural and sensory properties of yogurt fortified with fresh and dried Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis). Int. Food Res. 2019, 1(26), 65–76.

- Atallah, A.; Morsy, O.; Dalia, G. Characterization of functional low-fat yogurt enriched with whey protein concentrate, Ca-caseinate and Spirulina. Int. J. Food Prop. 2020, 23, 78–91.

- Part, N.; Kazantseva, J.; Rosenvald, S.; Kallastu, A.; Vaikma, H.; Kriščiunaite, T.; Pismennõi, D.; Viiard, E. Microbiological, chemical and sensorial characterization of commercially available vegetable yogurt alternatives. Future Foods 2023, 7, 100212.

- Barkallah, M.; Dammak, M.; Louati, I.; Hentati, F.; Hadrich, B.; Mechichi, T.; Ayadi, M.A.; Fendri, I.; Attia, H.; Abdelkafi, S. Effect of Spirulina platensis fortification on the physicochemical, textural, antioxidant and sensory properties of yogurt during fermentation and storage. LWT 2017, 84, 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Nazir, F.; Saeed, M.A.; Abbas, A.; Majeed, M.R.; Israr, M.; Zahid, H.; Ilyas, M.; Nasir, M. Development, quality assessment and nutritional enhancement of Spirulina platensis in yogurt paste. Food Sci. Appl. Biotechnol. 2022, 5, 106–106.

- Zaid, A.A.; Hammad, D.M.; Sharaf, E.M. Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity of S. platensis Water Extracts. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 11(7), 846-851.

- Jesus, C.S.; Uebel, L.S.; Costa, S.S.; Miranda, A.L.; Morais, E.G.; Morais, M.G.; Costa, J.A.V.; Nunes, I.L.; Ferreira, E.S.; Druzian, J.I. Outdoor pilot-scale cultivation of Spirulina sp. LEB-18 in different geographic locations for evaluating its growth and chemical composition. Bioresource technology 2018, 256, 86-94. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, S.M; Edris, A.E.; Sadek, Z. Novel approach for the inhibition of Helicobacter pylori contamination in yogurt using selected probiotics combined with eugenol and cinnamaldehyde nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2023, 417, 135877–135877. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Xiong, Z.; Xiong, H.; Aadil, R.M.; Khalid, N.; Lakhoo, A.B.J.; Zia-Ud-Din, N.A.W.A.Z.A.; Walayat, N.; Khan, R.S. Physicochemical, rheological and antioxidant profile of yogurt prepared from non-enzymatically and enzymatically hydrolyzed potato powder under refrigeration. Food Sci. Hum. Wellbeing 2023, 12, 69-78. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tang, T.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, J. The potential and challenge of microalgae as promising future food sources. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Barkallah, M.; Dammak, M.; Louati, I.; Hentati, F.; Hadrich, B.; Mechichi, T.; Ayadi, M.A.; Fendri, I.; Attia, H.; Abdelkafi, S. Effect of Spirulina platensis fortification on physicochemical, textural, antioxidant and sensory properties of yogurt during fermentation and storage. Lwt 2017, 84, 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Deng, C.; Luo, S.; Liu, C.; Hu, X. Effect of rice bran on yogurt properties: Comparison between bran addition before and after fermentation. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 135, 108122.

- Wang, X.; Kong, X.; Zhang, C.; Hua, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. Comparison of physicochemical properties and volatile flavor compounds of vegetable yogurt and dairy yogurt. Int. Food Res. J. 2023, 164, 112375.

- Castaño Peláez, H. I.; Cortés-Rodríguez, M.; Ortega-Toro, R. Storage stability of a fluidized-bed agglomerated spray-dried strawberry powder mixture. F1000Res. 2023, 12, 1174. [CrossRef]

- Gallón-Bedoya, M.; Cortés-Rodríguez, M.; Gil-González, J.; Lahlou, A.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L. Influence of storage variables on the antioxidant and antitumor activities, phenolic compounds and vitamin C of an agglomerate of Andean berries. Heliyon 2023, 9(4), e14857. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Protein (%) | Lipids (%) | Moisture (%) | Ash (%) | Carbohydrates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.96 ± 0.05d | 3.13 ± 0.21a | 83.10 ± 1.30a | 1.10 ± 0.20d | 8.74 ± 0.28c |

| Spirulina plantesis commercial | |||||

| 0.5% | 5.44 ± 0.26a | 2.28 ± 0.15c | 81.48 ± 1.60a | 1.31 ± 0.10cd | 9.49 ± 0.70b |

| 1.0% | 5.74 ± 0.03a | 2.41 ± 0.15bc | 80.15 ± 1.86a | 1.52 ± 0.10b | 9.26 ± 0.50b |

| 1.5% | 5.74 ± 0.03a | 2.52 ± 0.16bc | 80.25 ± 2.12a | 1.65 ± 0.14a | 9.86 ± 0.49b |

| 2.0% | 5.63 ± 0.54a | 2.53 ± 0.12bc | 80.18 ± 2.52a | 1.86 ± 0.20a | 10.05 ± 0.32ab |

| Spirulina platensis agglomerated with maltodextrin 30% (w/v) | |||||

| 0.5% | 4.33 ± 0.30c | 2.42 ± 0.15c | 82.66 ± 1.10a | 1.27 ± 0.05cd | 9.68 ± 0.14b |

| 1.0% | 4.81 ± 0.25bc | 2.64 ± 0.13bc | 81.14 ± 2.10a | 1.56 ± 0.12ab | 10.55 ± 0.16a |

| 1.5% | 5.41 ± 0.36a | 2.70 ± 0.18ab | 80.14 ± 1.85a | 1.67 ± 0.10a | 10.43 ± 0.11a |

| 2.0% | 5.49 ± 0.57ab | 2.79 ± 0.22ab | 80.13 ± 1.92a | 1.87 ± 0.10a | 10.36 ± 0.13a |

| Sample | Phenolic Compounds (mg.100g-1) |

Phycocyanin (mg.100g-1) |

β-carotene (mg.100g-1) |

Chlorophyll a (mg.100g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.58 ± 0.02e | 0.00 ± 0.00d | 0.00 ± 0.00g | 0.00 ± 0.00e |

| Spirulina plantesiscommercial | ||||

| 0.5% | 2.98 ± 0.02f | 2.19 ± 0.03c | 4.73 ± 0.05f | 12.39 ± 0.04d |

| 1.0% | 5.93 ± 0.06e | 3.39 ± 0.15a | 5.09 ± 0.02e | 12.70 ± 0.01d |

| 1.5% | 11.20 ± 0.05c | 3.57 ± 0.17a | 5.34 ± 0.06c | 13.28 ± 0.16c |

| 2.0% | 13.62 ± 0.02b | 3.65 ± 0.13a | 5.63 ± 0.01b | 14.07 ± 0.03a |

| Spirulina platensisagglomerated with maltodextrin 30% (w/v) | ||||

| 0.5% | 11.02 ± 0.02c | 3.07 ± 0.04b | 5.06 ± 0.03e | 12.43 ± 0.08d |

| 1.0% | 12.00 ± 0.42c | 3.12 ± 0.19ab | 5.24 ± 0.01d | 12.48 ± 0.04d |

| 1.5% | 13.19 ± 0.32b | 3.06 ± 0.01b | 5.49 ± 0.11c | 12.60 ± 0.19d |

| 2.0% | 14.96 ± 0.13a | 3.13 ± 0.06b | 6.37 ± 0.03a | 13.77 ± 0.12b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).