Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

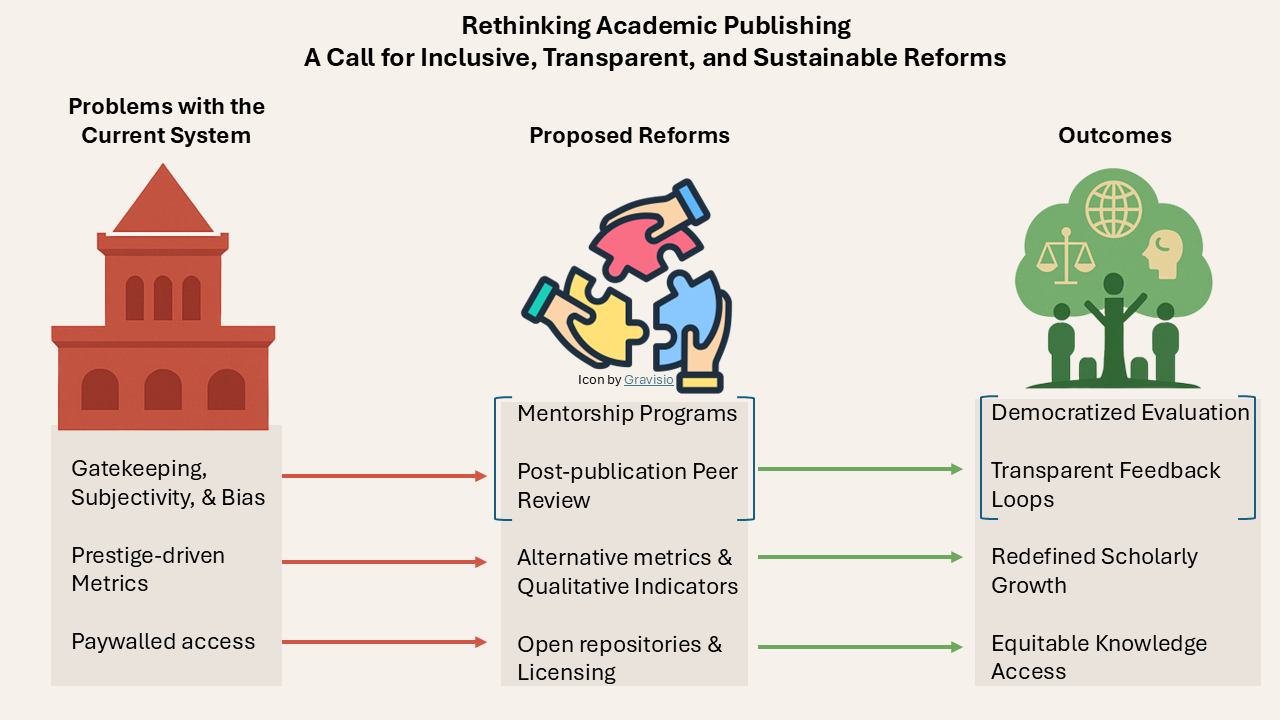

1. Position Overview: Toward a More Inclusive and Authentic Publishing Model

2. Critiques of the Current System

2.1. Gatekeeping and Editorial Subjectivity

2.2. Distorted Academic Priorities from Prestige-Driven Metrics

2.3. Barrier and Equity Issues in Research Accessibility

3. Strategies for Reformation

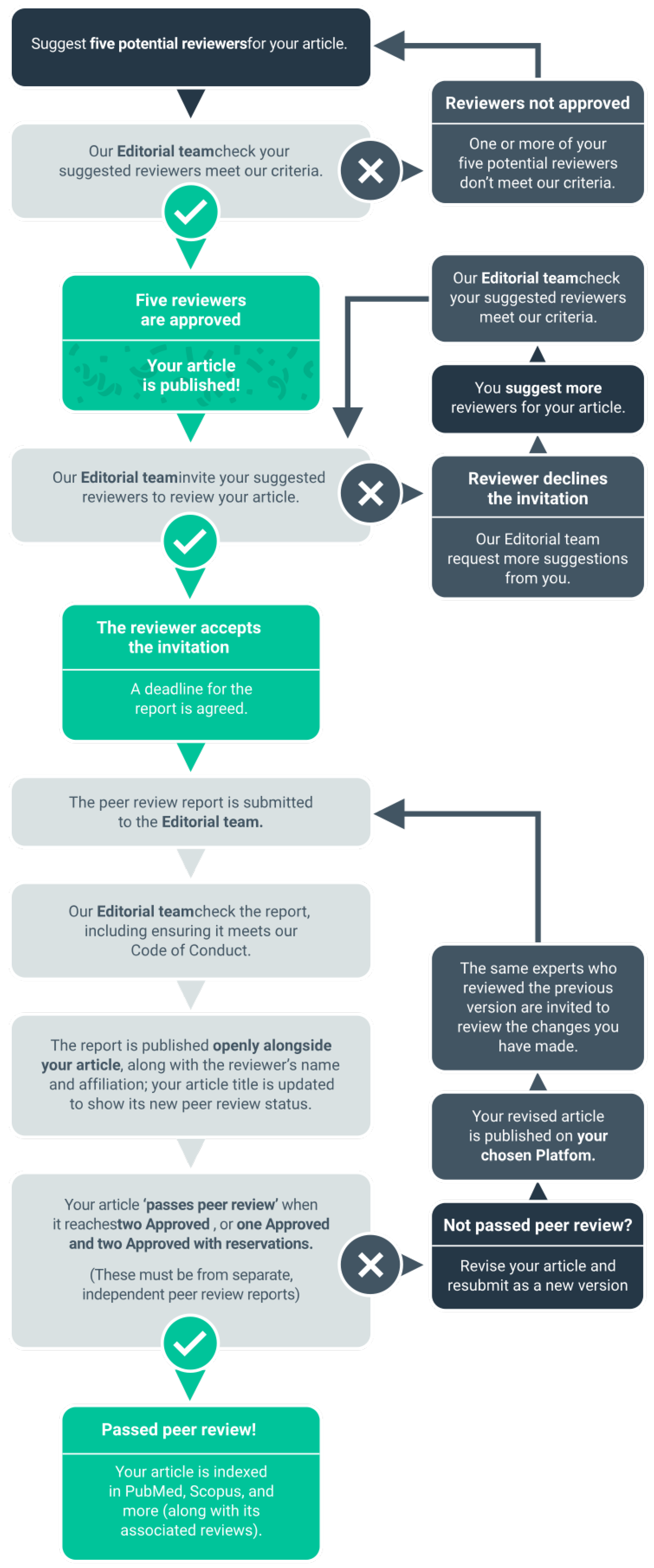

3.1. Mentorship-Oriented Editorial Practice and Post-Publication Peer Review Model

3.2. Toward Meaningful Research Evaluation

3.3. Democratizing Knowledge Accessibility

4. Anticipated Challenges and Counterarguments

4.1. Fear of Low-Quality Work

4.2. Resistance from Established Stakeholders

4.3. Sustainability Aspect of the Community Repository

5. Conclusion and Call to Action

5.1. Call to Action:

- For Researchers: Resist the pressure to chase prestige and metrics as proxies for worth. Publish what matters to you and your communities, not what aligns with arbitrary rankings or external validation. Respect your own contributions and those of others based on quality, relevance, and impact, not citation counts or journal rankings. By embracing open dissemination, thoughtful mentorship, and transparent review, researchers can foster a more inclusive, intellectually honest publishing culture.

- For Editors and Publishers: For editors, reimagine your roles as mentors rather than gatekeepers. Reassess traditional quality control methods and consider integrating mentorship programs and the post-publication peer review model into your editorial practices. For publishers, invest in sustainable, community-driven models that prioritize access and equity over profit.

- For Academic Institutions and Funding Agencies: Revise evaluation criteria to reward holistic, long-term contributions to scholarship and society. Move beyond journal-based metrics and incentivize open dissemination, methodological rigor, and interdisciplinary research through tenure, promotion, and funding decisions. Support initiatives that enhance community-driven repositories and open licensing policies.

- For Policymakers: Mandate public access to publicly funded research and invest in infrastructure that supports open science. Enact regulations that curb exploitative publishing practices and empower community-owned platforms that democratize knowledge for societal benefit.

References

- Harwell, E.N. Academic journal publishers antitrust litigation, 2024.

- Van Dalen, H.P. How the publish-or-perish principle divides a science: The case of economists. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 1675–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siler, K.; Lee, K.; Bero, L. Measuring the effectiveness of scientific gatekeeping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primack, R.B.; Regan, T.J.; Devictor, V.; Zipf, L.; Godet, L.; Loyola, R.; Maas, B.; Pakeman, R.J.; Cumming, G.S.; Bates, A.E.; et al. Are scientific editors reliable gatekeepers of the publication process? Biological Conservation 2019, 238, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, J.; Counsell, C. Impact factors: Uses and abuses. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2002, 14, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisonger, T.E. The benefits and drawbacks of impact factor for journal collection management in libraries. The Serials Librarian 2004, 47, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S. Liberate academic research from paywalls, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, J. Researchers outside APC-financed open access: Implications for scholars without a paying institution. Sage Open 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segado-Boj, F.; Martín-Quevedo, J.; Prieto-Gutiérrez, J.J. Jumping over the paywall: Strategies and motivations for scholarly piracy and other alternatives. Information Development 2024, 40, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterbury, S.; Wielander, G.; Pia, A.E. After the Labour of Love: the incomplete revolution of open access and open science in the humanities and creative social sciences. Commonplace 2022. https://commonplace.knowledgefutures.org/pub/lsiyku2n.

- Pia, A.E.; Batterbury, S.; Joniak-Lüthi, A.; LaFlamme, M.; Wielander, G.; Zerilli, F.M.; Nolas, M.; Schubert, J.; Loubere, N.; Franceschini, I.; et al. Labour of Love: An Open Access Manifesto for Freedom, Integrity, and Creativity in the Humanities and Interpretive Social Sciences. Commonplace 2020. https://commonplace.knowledgefutures.org/pub/y0xy565k.

- Ray, J. Judging the judges: The role of journal editors. QJM 2002, 95, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, B.W.; Samuels, D.J. Desk rejecting: A better use of your time. PS: Political Science & Politics 2021, 54, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Da Silva, J.A.; Al-Khatib, A.; Katavić, V.; Bornemann-Cimenti, H. Establishing sensible and practical guidelines for desk rejections. Science and Engineering Ethics 2018, 24, 1347–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkov, A.L. How to Publish a Good Article and to Reject a Bad One. Notes of a Reviewer. Automation & Remote Control 2003, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine 2005, 2, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jussim, L.; Honeycutt, N. Bias in psychology: A critical, historical and empirical review. Swiss Psychology Open 2024, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosek, B.A.; Errington, T.M. What is replication? PLOS Biology 2020, 18, e3000691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, M.; Foster, M.J.; Froyd, J.E. Systematic literature reviews in engineering education and other developing interdisciplinary fields. Journal of Engineering Education 2014, 103, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinarić, A.; Horvat, M.; Šupak Smolčić, V. Dealing with the positive publication bias: Why you should really publish your negative results. Biochemia Medica 2017, 27, 030201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, D. Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics 2012, 90, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.; Lee, S.; Bridgman, H.; Thapa, D.K.; Cleary, M.; Kornhaber, R. Benefits, barriers and enablers of mentoring female health academics: An integrative review. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0215319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, W.H. How much better are the most-prestigious journals? The statistics of academic publication. Organization Science 2005, 16, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembs, B. Prestigious science journals struggle to reach even average reliability. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.J. An examination of the reliability of prestigious scholarly journals: Evidence and implications for decision-makers. Economica 2007, 74, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, K.S.; Luu, S.; Cheah, R.; Kc, S.; Mushtaq, A.; Elijah, M.; Poudel, B.K.; Cham, C.F.X.; Mandal, S.; Muhi, S.; et al. Mentorship advances antimicrobial use surveillance systems in low- and middle-income countries. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance 2024, 7, dlae212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKiernan, E.C.; Schimanski, L.A.; Muñoz Nieves, C.; Matthias, L.; Niles, M.T.; Alperin, J.P. Use of the Journal Impact Factor in academic review, promotion, and tenure evaluations. eLife 2019, 8, e47338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, C.A.; Bicca-Marques, J.C.; Calvignac-Spencer, S.; Fan, P.; Fashing, P.J.; Gogarten, J.; Guo, S.; Hemingway, C.A.; Leendertz, F.; Li, B.; et al. Games academics play and their consequences: how authorship, h-index and journal impact factors are shaping the future of academia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2019, 286, 20192047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount Royal University. Criteria, evidence and standards for tenure and promotion.

- Garfield, E. Citation indexes in sociological and historical research. American Documentation 1963, 14, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viiu, G.A.; Paunescu, M. The lack of meaningful boundary differences between journal impact factor quartiles undermines their independent use in research evaluation. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 1495–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembs, B.; Button, K.; Munafò, M. Deep impact: Unintended consequences of journal rank. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulos, Y.; Katsaros, D. Metrics and rankings: Myths and fallacies. In Data Analytics and Management in Data Intensive Domains; Kalinichenko, L.; Kuznetsov, S.O.; Manolopoulos, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; Vol. 706, pp. 265–280. Series Title: Communications in Computer and Information Science. [CrossRef]

- Sloane, E.H. Reductionism. Psychological Review 1945, 52, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D.; Wouters, P.; Waltman, L.; De Rijcke, S.; Rafols, I. Bibliometrics: The leiden manifesto for research metrics. Nature 2015, 520, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembs, B. Reliable novelty: New should not trump true. PLOS Biology 2019, 17, e3000117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldino, P.E.; McElreath, R. The natural selection of bad science. Royal Society Open Science 2016, 3, 160384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Royal Golden Jubilee (RGJ) Ph.D. Programme. Publication criteria.

- Head, M.L.; Holman, L.; Lanfear, R.; Kahn, A.T.; Jennions, M.D. The extent and consequences of P-hacking in science. PLOS Biology 2015, 13, e1002106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.A.; Pustejovsky, J.E. Evaluating meta-analytic methods to detect selective reporting in the presence of dependent effect sizes. Psychological methods 2021, 26, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewidar, O.; Elmestekawy, N.; Welch, V. Improving equity, diversity, and inclusion in academia. Research Integrity and Peer Review 2022, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, J.P.; Waldner, F.; Jacques, D.C.; Masuzzo, P.; Collister, L.B.; Hartgerink, C.H.J. The academic, economic and societal impacts of open access: an evidence-based review. F1000Research 2016, 5, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, V.; Haustein, S.; Mongeon, P. The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0127502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, A.; Coate, K.; Curry, S.; Lawson, S.; Moxham, N.; Røstvik, C.M. Untangling academic publishing: A history of the relationship between commercial interests, academic prestige and the circulation of research, 2017.

- Sheare, K. Responding to unsustainable journal costs: A CARL brief, 2018.

- Van Noorden, R. Open access: The true cost of science publishing. Nature 2013, 495, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute [MDPI]. Open Access and Article Processing Charge (APC).

- Public Library of Science [PLOS]. PLOS Fee.

- HighWire Press. Rethinking Open Access: Moving Beyond Article Processing Charges for True Equity, 2024.

- Greshake, B. Looking into Pandora’s box: The content of Sci-hub and its usage. F1000Research 2017, 6, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, J.S. Sci-hub: A solution to the problem of paywalls, or merely a diagnosis of a broken system? Annals of Emergency Medicine 2016, 68, 15A–17A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelstein, D.S.; Romero, A.R.; Levernier, J.G.; Munro, T.A.; McLaughlin, S.R.; Greshake Tzovaras, B.; Greene, C.S. Sci-Hub provides access to nearly all scholarly literature. eLife 2018, 7, e32822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.C.; Laverde-Rojas, H.; Tejada, J.; Marmolejo-Ramos, F. The Sci-Hub effect on papers’ citations. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startup, A.; Dupuis Brouillette, M. Canadian journal for new scholars in education.

- Lorenzetti, D.L.; Shipton, L.; Nowell, L.; Jacobsen, M.; Lorenzetti, L.; Clancy, T.; Paolucci, E.O. A systematic review of graduate student peer mentorship in academia. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 2019, 27, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, F.E. Mentoring gone wrong: What is happening to mentorship in academia? Policy Futures in Education 2021, 19, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F1000Research. The Peer Review Process.

- Pros and cons of open peer review. Nature Neuroscience 1999, 2, 197–198. [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, D.; Wang, P.; Hembree, A.; Park, H. Open peer review: Promoting transparency in open science. Scientometrics 2020, 125, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueger, N.S.; Thoma, B.; Hsu, C.H.; Sullivan, D.; Peters, L.; Lin, M. The altmetric score: A new measure for article-level dissemination and impact. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2015, 66, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagan, R. San Francisco declaration on research assessment. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2013, p. dmm.012955. [CrossRef]

- University of Alberta. Faculty of education faculty evaluation committee procedures and criteria for the evaluation of academic faculty, 2022.

- Creative Commons. About CC licenses, 2019.

- Ginsparg, P. ArXiv at 20. Nature 2011, 476, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K. ResearchGate. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2019, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, E.D.; Deardorff, A. Open science framework (OSF). Journal of the Medical Library Association 2017, 105, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Alberta Library. ERA (Education and research archive).

- Arms, W.Y. What are the alternatives to peer review? Quality control in scholarly publishing on the web. The Journal of Electronic Publishing 2002, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, J. Predatory publishers are corrupting open access. Nature 2012, 489, 179–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlee, F. Making reviewers visible: Openness, accountability, and credit. Journal of American Medical Association 2002, 287, 2762–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross-Hellauer, T. What is open peer review? A systematic review. F1000Research 2017, 6, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, G.; Grimaldo, F.; López-Iñesta, E.; Mehmani, B.; Squazzoni, F. The effect of publishing peer review reports on referee behavior in five scholarly journals. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdill, R.J.; Blekhman, R. Tracking the popularity and outcomes of all bioRxiv preprints. eLife 2019, 8, e45133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, N.; Brierley, L.; Dey, G.; Polka, J.K.; Pálfy, M.; Nanni, F.; Coates, J.A. The evolving role of preprints in the dissemination of COVID-19 research and their impact on the science communication landscape. PLOS Biology 2021, 19, e3000959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Squazzoni, F. Can transparency undermine peer review? A simulation model of scientist behavior under open peer review. Science and Public Policy 2022, 49, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, H.; Priem, J.; Larivière, V.; Alperin, J.P.; Matthias, L.; Norlander, B.; Farley, A.; West, J.; Haustein, S. The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of open access articles. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiltz, M. Science without publication paywalls: cOAlition S for the realisation of full and immediate open access. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, I.; Kraker, P.; Lex, E.; Gumpenberger, C.; Gorraiz, J.I. Zenodo in the spotlight of traditional and new metrics. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 2017, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, M.A.; García-Barriocanal, E.; Sánchez-Alonso, S. Community curation in open dataset repositories: Insights from zenodo. Procedia Computer Science 2017, 106, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).