Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

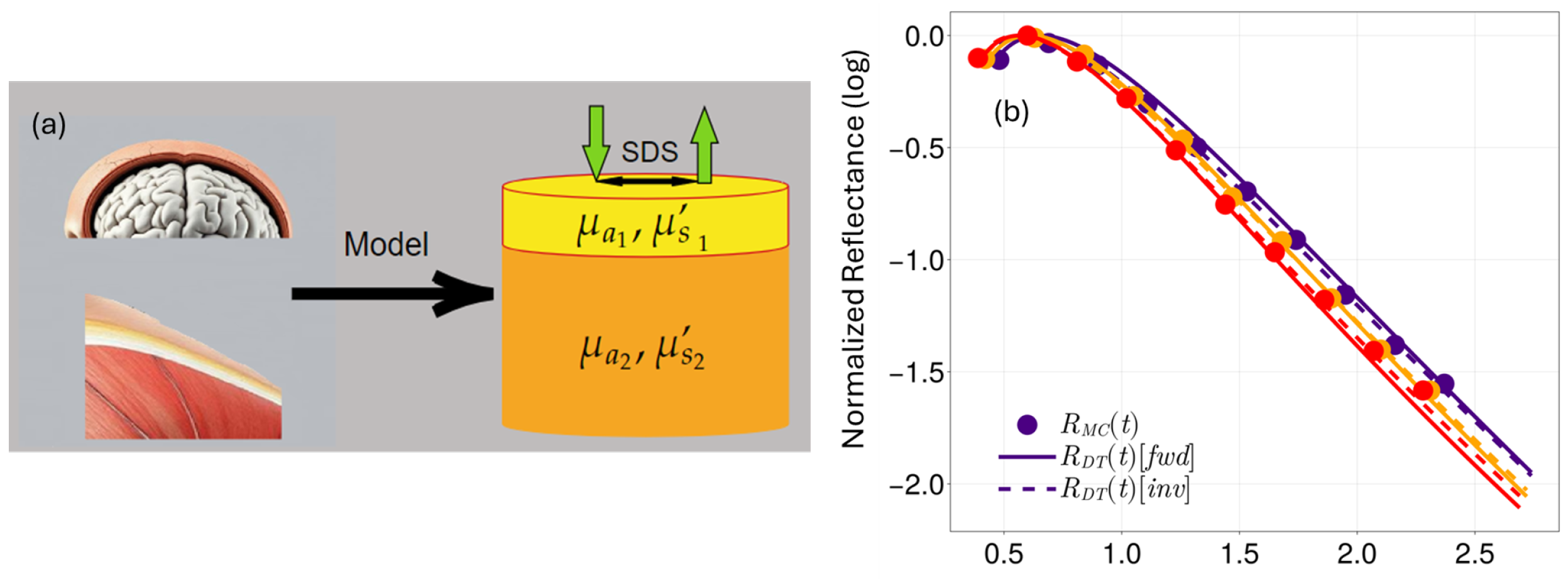

2.1. Bi-Layered Tissue Models

2.2. Monte Carlo Simulation of Reflectance Signals

2.3. Forward-Modeling of Diffuse Reflectance Signal

2.4. Inverse Fitting of Reflectance

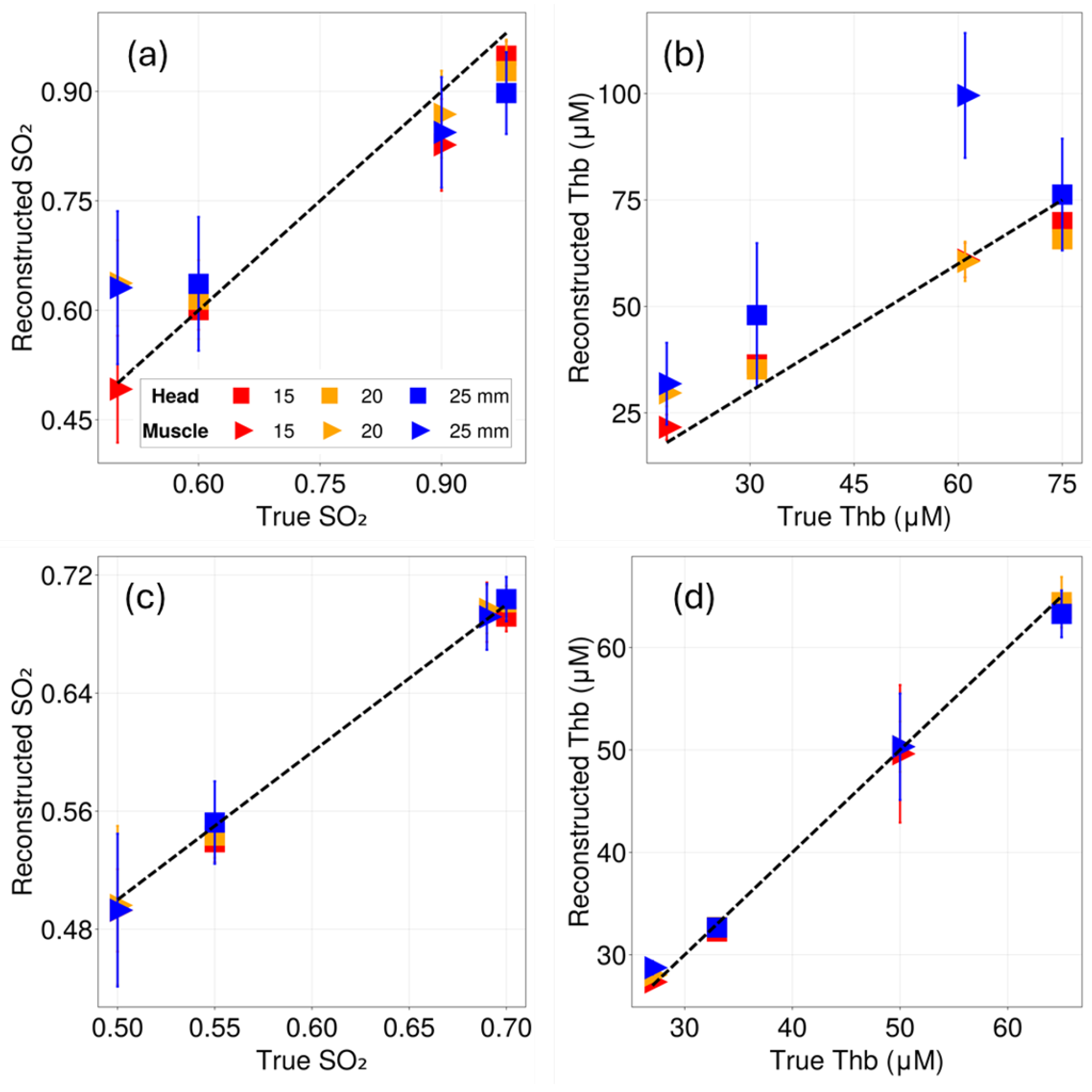

2.5. Retrieval of Functional Endpoints

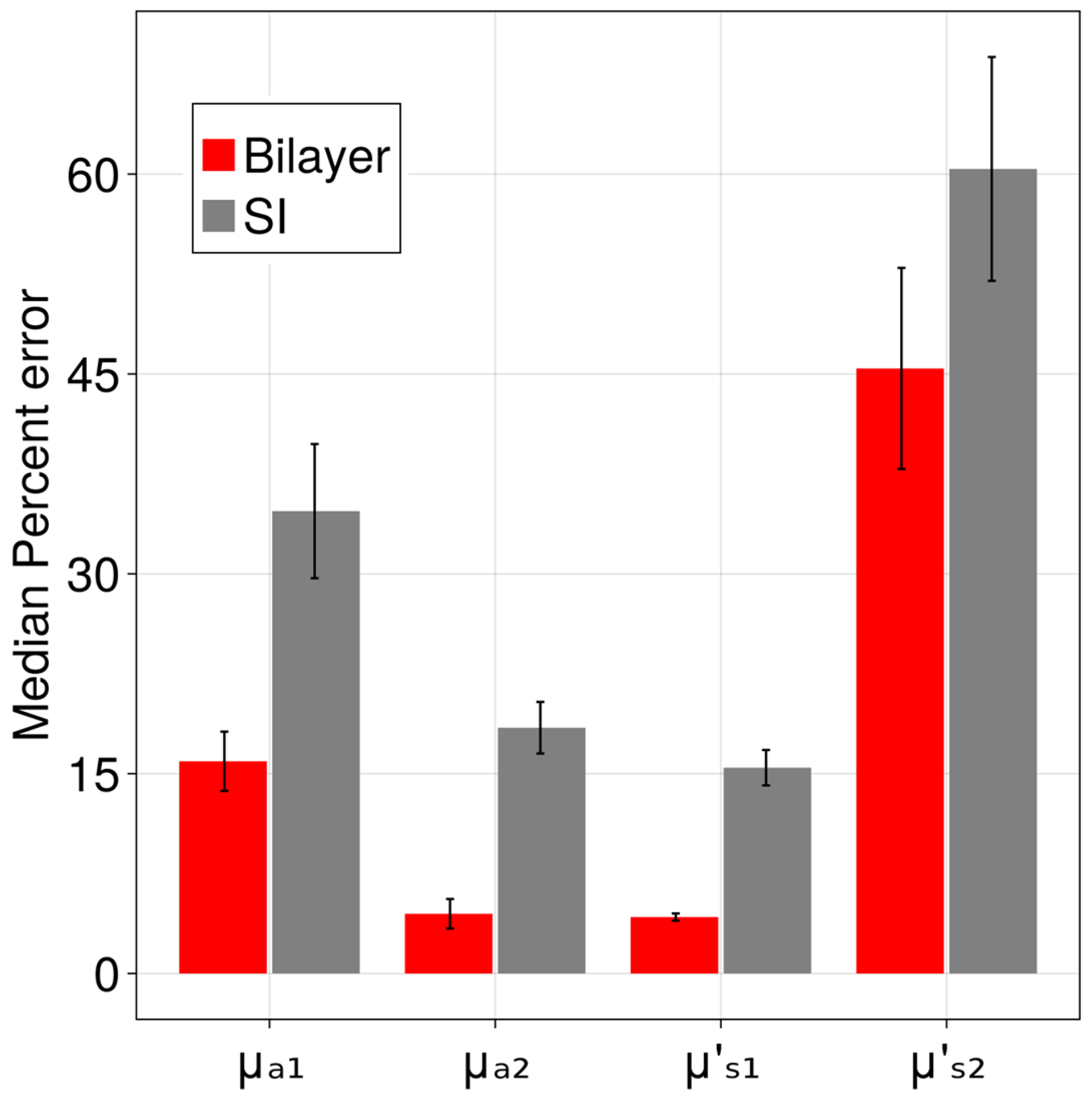

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SI | Semi Infinite |

| DT | Diffusion Theory |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| TPSF | Temporal Point Spread Function |

| THb | Total Hemoglobin Concentration |

| Fractional Oxygen Saturation | |

| SDS | Source Detector Separation |

| SNR | Signal to Noise Ratio |

Appendix A. Computed Optical Transport Coefficients

| Tissue Model | Layer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Top (scalp,skull) | ||

| Bottom (Brain) | |||

| Muscle | Top (skin,fat) | ||

| Bottom (Muscle) |

| Tissue Model | Layer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Top (scalp,skull) | ||

| Bottom (Brain) | |||

| Muscle | Top (skin,fat) | ||

| Bottom (Muscle) |

| Tissue Model | Layer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Top (scalp,skull) | ||

| Bottom (Brain) | |||

| Muscle | Top (skin,fat) | ||

| Bottom (Muscle) |

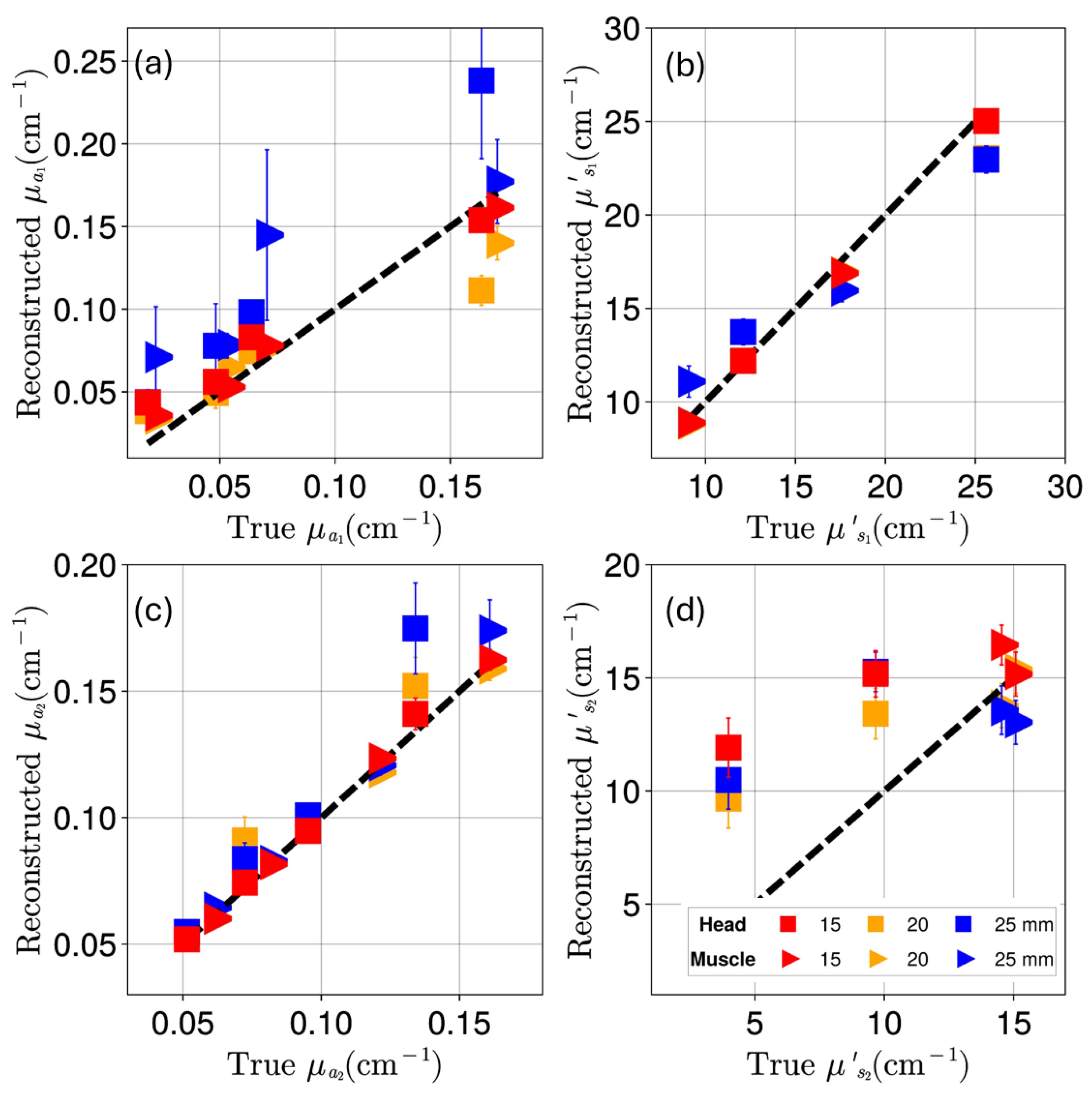

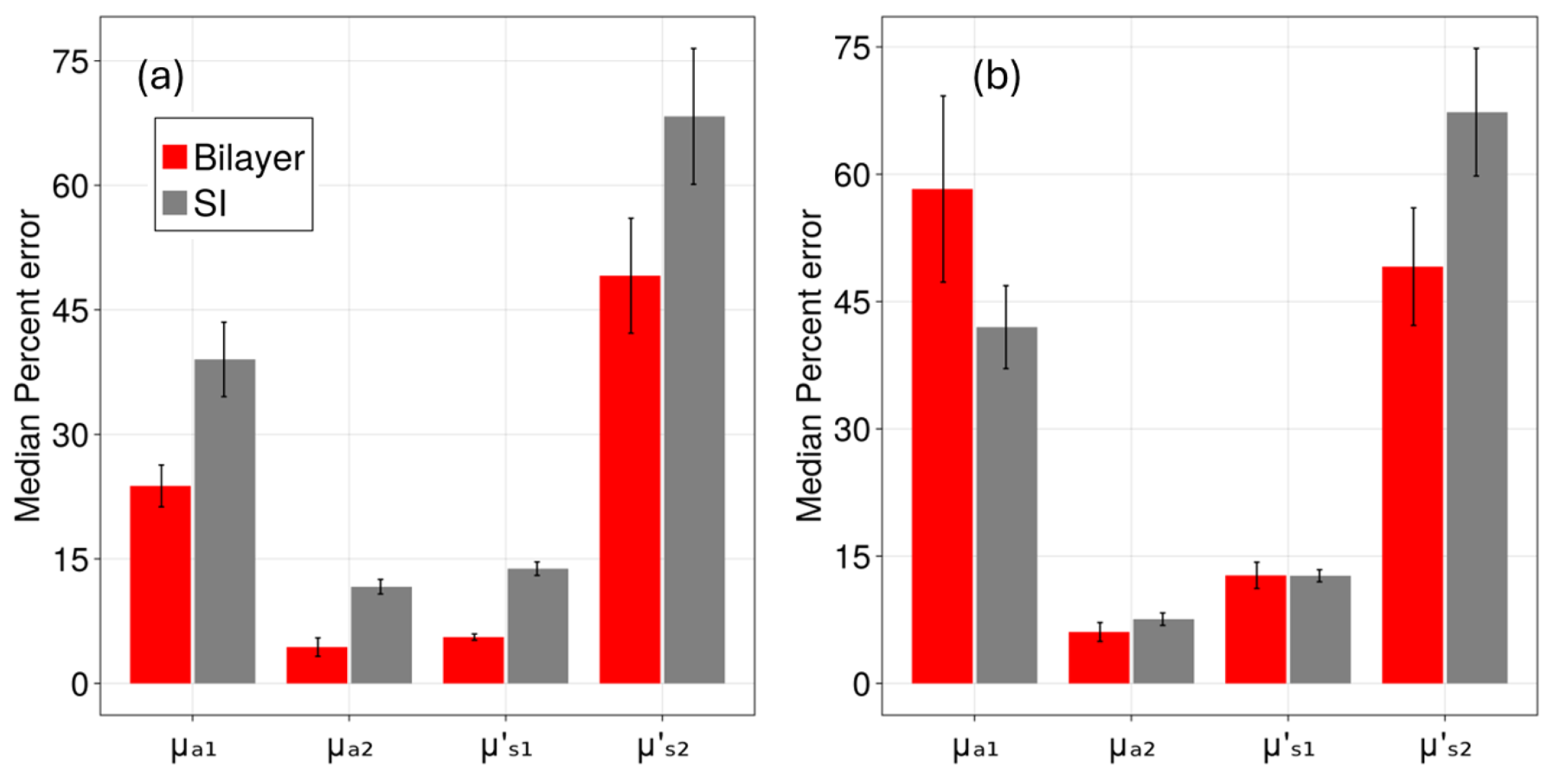

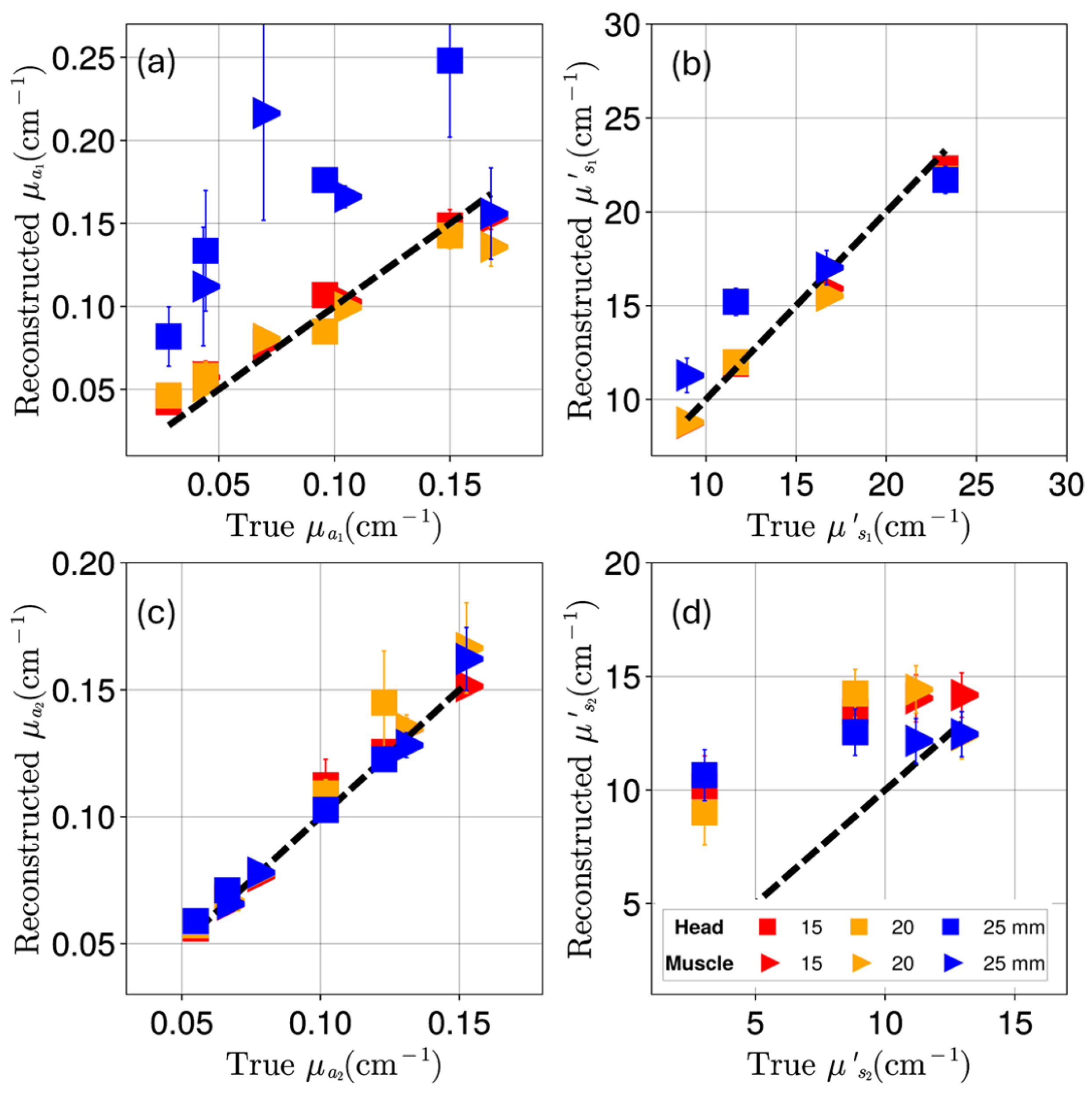

Appendix B. Reconstruction of Optical Coefficients

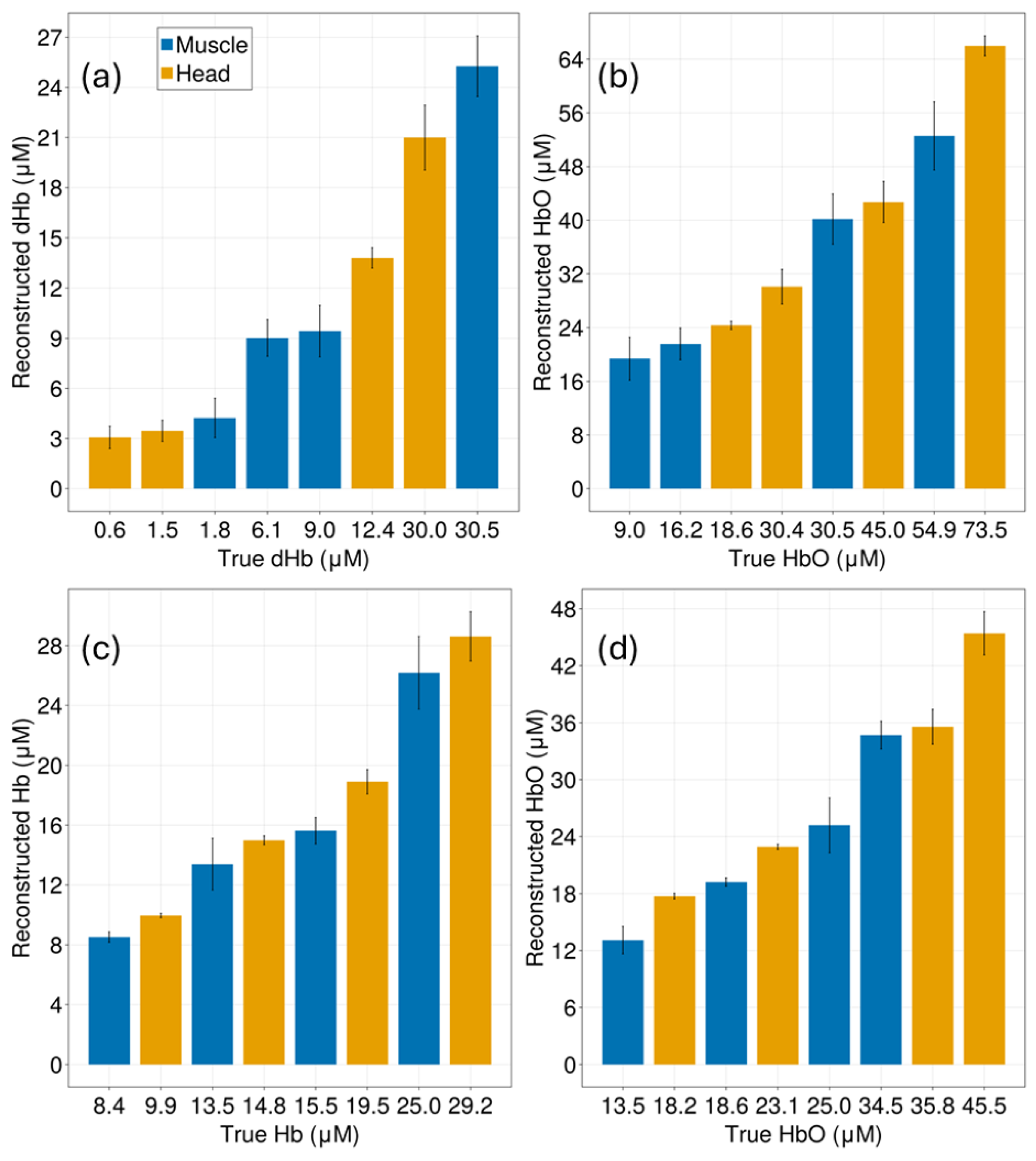

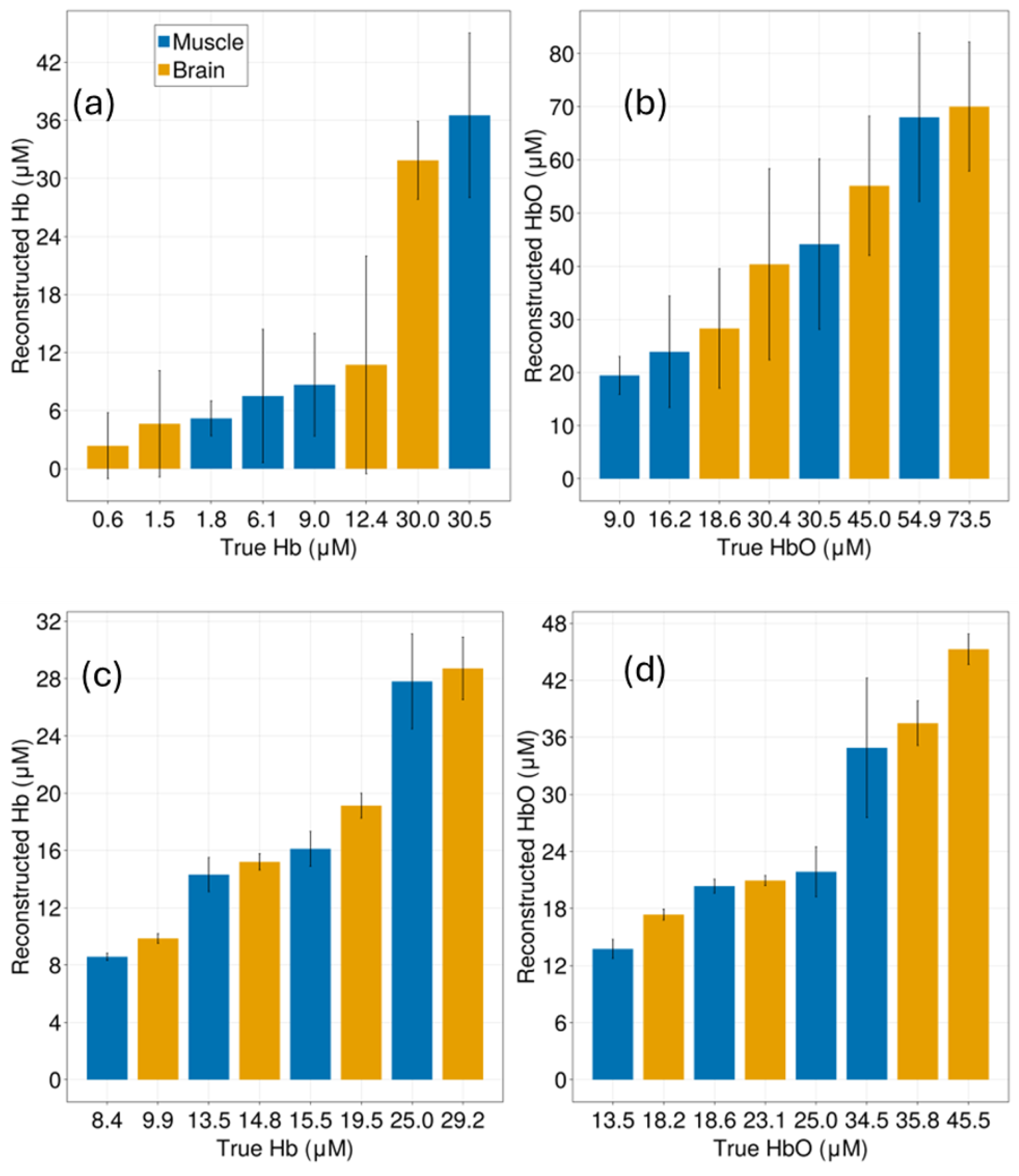

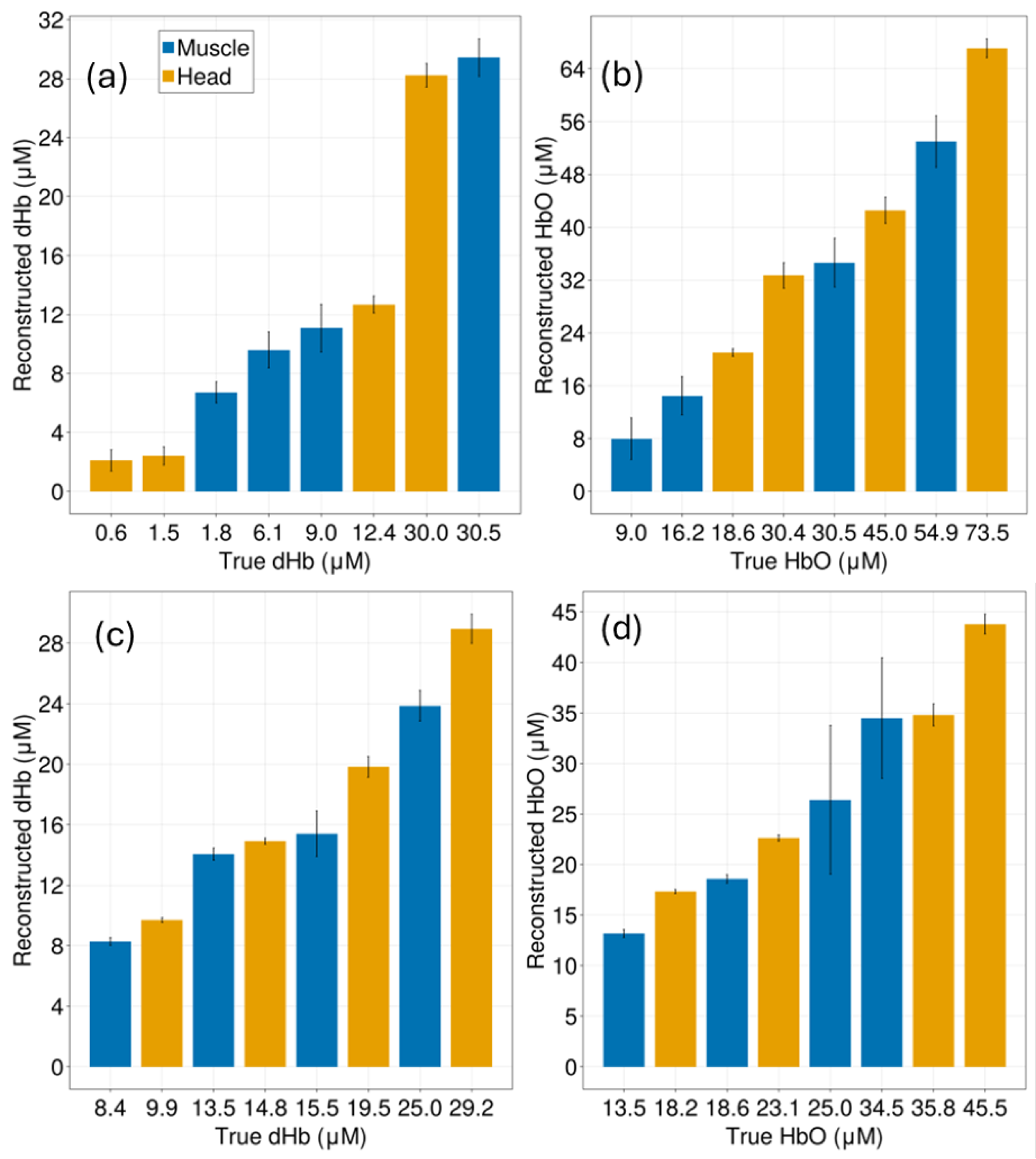

Appendix C. Reconstruction of Deoxygenated and Oxygenated Hemoglobin Concentrations

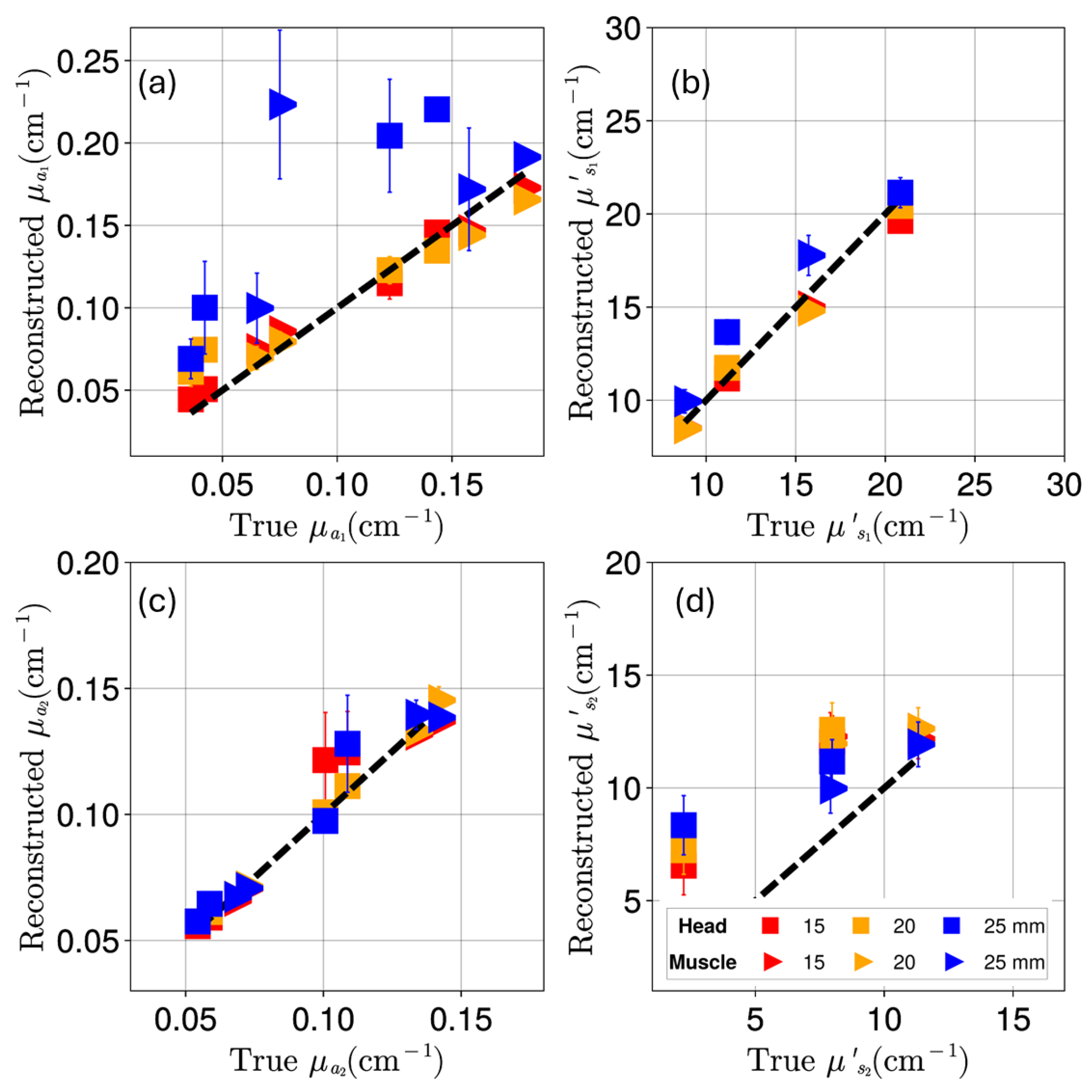

Appendix D. Reconstruction of Optical Coefficients Using Semi-Infinite Tissue Approximation

References

- Blaney, G.; Donaldson, R.; Mushtak, S.; Nguyen, H.; Vignale, L.; Fernandez, C.; Pham, T.; Sassaroli, A.; Fantini, S. Dual-Slope Diffuse Reflectance Instrument for Calibration-Free Broadband Spectroscopy. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, M.; Hoshi, Y.; Yamada, Y. Simple algorithm for the measurement of absorption coefficients of a two-layered medium by spatially resolved and time-resolved reflectance. Applied Optics 2005, 44, 7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, S.K.V.; Lanka, P.; Farina, A.; Mora, A.D.; Andersson-Engels, S.; Taroni, P.; Pifferi, A. Broadband Time Domain Diffuse Optical Reflectance Spectroscopy: A Review of Systems, Methods, and Applications. Applied Sciences 2019, Vol. 9, Page 5465 2019, 9, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Sasamoto, N.; Lee, H.Y.; Ando, M.; Song, M.; Tamimi, R.M.; Kawachi, I.; Campbell, P.T.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Weiderpass, E.; et al. Is early-onset cancer an emerging global epidemic? Current evidence and future implications. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Quaresima, V. A brief review on the history of human functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) development and fields of application. NeuroImage 2012, 63, 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Yamashita, Y. Time-Domain Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Imaging: A Review. Applied Sciences 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifferi, A.; Contini, D.; Mora, A.D.; Farina, A.; Spinelli, L.; Torricelli, A. New frontiers in time-domain diffuse optics, a review. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2016, 21, 091310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, L.L.D.; Bydlon, T.M.; Duijnhoven, F.V.; Peeters, M.J.T.V.; Loo, C.E.; Winter-Warnars, G.A.; Sanders, J.; Sterenborg, H.J.; Hendriks, B.H.; Ruers, T.J. Towards the use of diffuse reflectance spectroscopy for real-time in vivo detection of breast cancer during surgery. Journal of Translational Medicine 2018, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallacoglu, B. Absolute measurement of cerebral optical coefficients, hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation in old and young adults with near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2012, 17, 081406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, A.; Torricelli, A.; Bargigia, I.; Spinelli, L.; Cubeddu, R.; Foschum, F.; Jäger, M.; Simon, E.; Fugger, O.; Kienle, A.; et al. In-vivo multilaboratory investigation of the optical properties of the human head. Biomedical Optics Express 2015, 6, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Lacerenza, M.; Amendola, C.; Buttafava, M.; Contini, D.; Rossi, V.; Spinelli, L.; Zanelli, S.; Zuccotti, G.; Torricelli, A. Cerebral baseline optical and hemodynamic properties in pediatric population: a large cohort time-domain near-infrared spectroscopy study. Neurophotonics 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, A.; Bianchi, L.; Saccomandi, P.; Pifferi, A. Optical signatures of thermal damage on ex-vivo brain, lung and heart tissues using time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 2024, 15, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, F.; Binzoni, T.; Bianco, S.D.; Liemert, A.; Kienle, A. Light Propagation Through Biological Tissue and Other Diffusive Media_ Theory, Solutions, and Validations; SPIE, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi, Y. New Horizons in Time-Domain Diffuse Optical Spectroscopy and Imaging; MDPI, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blaney, G.; Sassaroli, A.; Fantini, S. Spatial sensitivity to absorption changes for various near-infrared spectroscopy methods: A compendium review. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, H.; Yoshizawa, N.; Ohmae, E.; Ueda, Y.; Yoshimoto, K.; Mimura, T.; Nasu, H.; Asano, Y.; Ogura, H.; Sakahara, H.; et al. Water and lipid content of breast tissue measured by six-wavelength time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, S.; Kacprzak, M.; Rey-Perez, A.; Baena, J.; Riveiro, M.; Maruccia, F.; Fischer, J.B.; Poca, M.A.; Durduran, T. How the heterogeneity of the severely injured brain affects hybrid diffuse optical signals: case examples and guidelines. Neurophotonics 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienle, A.; Glanzmann, T.; Wagnières, G.; van den Bergh, H. Investigation of two-layered turbid media with time-resolved reflectance. Applied Optics 1998, 37, 6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taroni, P.; Pifferi, A.; Quarto, G.; Farina, A.; Ieva, F.; Paganoni, A.M.; Abbate, F.; Cassano, E.; Cubeddu, R. Time domain diffuse optical spectroscopy: in-vivo quantification of collagen in breast tissue. In Proceedings of the Optical Methods for Inspection, Characterization, and Imaging of Biomaterials II; SPIE, 2015; Vol. 9529, pp. 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer, A.; del Carmen Bravo, M. Near-infrared spectroscopy: A methodology-focused review. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2011, 16, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, D.A.; García, H.A.; Waks-Serra, M.V.; Carbone, N.A.; Iriarte, D.I.; Pomarico, J.A. Determining light absorption changes in multilayered turbid media through analytically computed photon mean partial pathlengths. Optica Pura y Aplicada 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, A.H.; Liu, H.; Chance, B.; Tittel, F.K.; Jacques, S.L. Time-resolved photon emission from layered turbid media. Applied Optics 1996, 35, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanka, P.; Segala, A.; Farina, A.; Sekar, S.K.V.; Nisoli, E.; Valerio, A.; Taroni, P.; Cubeddu, R.; Pifferi, A. Non-invasive investigation of adipose tissue by time domain diffuse optical spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 2020, 11, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannella, M.; Contini, D.; Pagliazzi, M.; Pifferi, A.; Spinelli, L.; Erdmann, R.; Donat, R.; Rocchetti, I.; Rehberger, M.; Konig, N.; et al. BabyLux device: a diffuse optical system integrating diffuse correlation spectroscopy and time-resolved near-infrared spectroscopy for the neuromonitoring of the premature newborn brain. Neurophotonics 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Z.D.; Reitzle, D.; Kienle, A. Errors in diffuse optical absorption spectroscopy of two-layered turbid media due to assuming a homogeneous medium. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 3118–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, M.; Quaresima, V. Near Infrared Brain and Muscle Oximetry: From the Discovery to Current Applications. Journal of Near Infrared Spectroscopy 2012, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, M.; Zerafa, S.; Vishwanath, K.; Mycek, M.A. Efficient computation of the steady-state and time-domain solutions of the photon diffusion equation in layered turbid media. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, S.L. Optical properties of biological tissues: a review. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2013, 58, R37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, L.; Gauthier, C.; Hoge, R.D.; Lesage, F.; Selb, J.; Boas, D.A. Double-layer estimation of intra- and extracerebral hemoglobin concentration with a time-resolved system. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2008, 13, 054019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Hoshi, Y.; Yamada, Y. Simple algorithm for the measurement of absorption coefficients of a two-layered medium by spatially resolved and time-resolved reflectance. Appl. Opt. 2005, 44, 7554–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, C.; Shimada, M.; Yamada, Y.; Hoshi, Y. Extraction of depth-dependent signals from time-resolved reflectance in layered turbid media. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2005, 10, 064008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Hennessy, R.; Markey, M.K.; Tunnell, J.W. Verification of a two-layer inverse Monte Carlo absorption model using multiple source-detector separation diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 2014, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, G.; Bottoni, M.; Sassaroli, A.; Fernandez, C.; Fantini, S. Broadband diffuse optical spectroscopy of two-layered scattering media containing oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, water, and lipids. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, C.; Shimada, M.; M.D., Y.H.; Yamada, Y. Extraction of depth-dependent signals from time-resolved reflectance in layered turbid media. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2005, 10, 064008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrink, J.; Wabnitz, H.; Obrig, H.; Villringer, A.; Rinneberg, H. Determining changes in NIR absorption using a layered model of the human head. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2001, 46, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kienle, A.; Patterson, M.S.; Dögnitz, N.; Bays, R.; Wagnières, G.; van den Bergh, H. Noninvasive determination of the optical properties of two-layered turbid media. Applied Optics 1998, 37, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kienle, A.; Patterson, M.S. Improved solutions of the steady-state and the time-resolved diffusion equations for reflectance from a semi-infinite turbid medium. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 1997, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tualle, J.M.; Prat, J.; Tinet, E.; Avrillier, S. Real-space Green’s function calculation for the solution of the diffusion equation in stratified turbid media. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2000, 17, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, F.; Pifferi, A.; Farina, A.; Amendola, C.; Maffeis, G.; Tommasi, F.; Cavalieri, S.; Spinelli, L.; Torricelli, A. Statistics of maximum photon penetration depth in a two-layer diffusive medium. Biomedical Optics Express 2024, 15, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, F.; Sassaroli, A.; Yamada, Y.; Zaccanti, G. Analytical approximate solutions of the time-domain diffusion equation in layered slabs. Journal of the Optical Society of America. A, Optics, image science, and vision 2002, 19 1, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, H.; Iriarte, D.; Pomarico, J.; Grosenick, D.; Macdonald, R. Retrieval of the optical properties of a semiinfinite compartment in a layered scattering medium by single-distance, time-resolved diffuse reflectance measurements. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2017, 189, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.M.; Chan, S.T.; Mazumder, D.; Tamborini, D.; Stephens, K.A.; Deng, B.; Farzam, P.; Chu, J.Y.; Franceschini, M.A.; Qu, J.Z.; et al. Improved accuracy of cerebral blood flow quantification in the presence of systemic physiology cross-talk using multi-layer Monte Carlo modeling. Neurophotonics 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, F.; Sassaroli, A.; Bianco, S.D.; Yamada, Y.; Zaccanti, G. Solution of the time-dependent diffusion equation for layered diffusive media by the eigenfunction method. Physical Review E 2003, 67, 056623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, M. LightPropagation.jl: A Julia package for simulating light propagation, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-15.

- McMurdy, J.; Jay, G.; Suner, S.; Crawford, G. Photonics-based In Vivo total hemoglobin monitoring and clinical relevance. Journal of Biophotonics 2009, 2, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahl, S. Optical Absorption Spectra of Hemoglobin. https://omlc.org/spectra/hemoglobin/summary.html, 1999. Accessed: October 15, 2023. Oregon Medical Laser Center.

- Vishwanath, K.; Pogue, B.; Mycek, M.A. Quantitative fluorescence lifetime spectroscopy in turbid media: comparison of theoretical, experimental and computational methods. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2002, 47, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, K.; Mycek, M.A. Time-resolved photon migration in bi-layered tissue models. Optics Express 2005, 13, 7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Gul, B.; Khan, S.; Nisar, H.; Ahmad, I. Refractive index of biological tissues: Review, measurement techniques, and applications. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2021, 33, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, F.; Bianco, S.D.; Zaccanti, G.; Pifferi, A.; Torricelli, A.; Bassi, A.; Taroni, P.; Cubeddu, R. Phantom validation and in vivo application of an inversion procedure for retrieving the optical properties of diffusive layered media from time-resolved reflectance measurements. Optics Letters 2004, 29, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekhar, S.; Vishwanath, K. Sensitivity Of Time-Resolved Diffuse Reflectance To Optical Coefficients In Bilayered Tissues. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Optics + Laser Science 2024 (FiO, LS); Optica Publishing Group, 2024; p. JW5A.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawschenko, E.; Schaller, T.; Kern, B.; Bode, B.; Dörries, F.; Kusche-Vihrog, K.; Gehring, H.; Wegerich, P. Current Status of Measurement Accuracy for Total Hemoglobin Concentration in the Clinical Context. Biosensors 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseri, N.; Kleiser, S.; Ostojic, D.; Karen, T.; Wolf, M. Quantifying the effect of adipose tissue in muscle oximetry by near infrared spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 2016, 7, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaes, M.; Grant, P.E.; Sliva, D.D.; Roche-Labarbe, N.; Pienaar, R.; Boas, D.A.; Franceschini, M.A.; Selb, J. Assessment of the frequency-domain multi-distance method to evaluate the brain optical properties: Monte Carlo simulations from neonate to adult. Biomedical Optics Express 2011, 2, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tissue Model | Layer | b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Top | ||||

| Bottom | |||||

| Muscle | Top | ||||

| Bottom |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).